Abstract

Introduction: Maastricht University has been actively exploring blended learning approaches to PBL in Health Master Programs. Key principles of PBL are, learning should be constructive, self-directed, collaborative, and contextual. The purpose is to explore whether these principles are applicable in blended learning.

Methods: The programs, Master of Health Services Innovation (case 1), Master Programme in Global Health (case 2), and the Master of Health Professions Education (case 3), used a Virtual Learning Environment for exchanging material and were independently analyzed. Quantitative data were collected for cases 1 and 2. Simple descriptive analyses such as frequencies were performed. Qualitative data for cases 1 and 3 were collected via (focus group) interviews.

Results: All PBL principles could be recognized in case 1. Case 2 seemed to be more project-based. In case 3, collaboration between students was not possible because of a difference in time-zones. Important educational aspects: agreement on rules for (online) sessions; visual contact (student–student and student–teacher), and frequent feedback.

Conclusion: PBL in a blended learning format is perceived to be an effective strategy. The four principles of PBL can be unified in PBL with a blended learning format, although the extent to which each principle can be implemented can differ.

Introduction

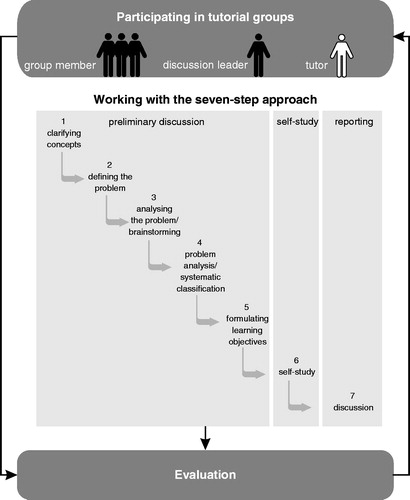

Problem-based learning (PBL) is a well-researched and well-established educational format based on insights into human learning. “PBL works!” concluded Dolmans and Schmidt (Citation2010, p. 13) based on several studies of the effects of PBL, and high satisfaction among students and teachers, as well as positive effects of group learning have been reported (Dolmans & Schmidt Citation2010). In “traditional” PBL at Maastricht University students work on tasks in small groups using a seven-step approach spread over three distinct phases: pre-discussion, self-study, and reporting (). Although PBL can take different formats, the core of PBL resides in four key principles of student-centered learning: learning should be constructive, self-directed, collaborative, and contextual (Dolmans et al. Citation2005). Students should be activating or constructing knowledge and integrating new information (a constructive process). Students also play an active role in the planning, monitoring, and evaluation of their learning. In self-direction or self-regulation reflection plays an important role (Dolmans & Schmidt Citation2010). A basic assumption of PBL is that collaborative interactions between students have a positive impact on learning (Dolmans et al. Citation2005). Another tenet is that a meaningful context facilitates knowledge transfer and nurtures the ability of students to solve real-life problems (Suzuki et al. Citation2007).

Figure 1. PBL study skills. Diagram of components (Van Til & Van der Heijden, Citation2009, p. 7).

In education, at universities and elsewhere, the term blended learning is used widely but not always consistently (Oliver & Trigwell Citation2005). Different mixes can be involved, for example, blending online and face-to-face instruction, blending instructional modalities, and blending instructional methods. It is a popular concept (Spanjers et al. Citation2015). We use the definition of blended learning as “a combination of traditional face-to-face and online instruction” (Graham Citation2013, p. 334). Educational programs can benefit from technology exploited for learning and teaching, since it offers greater flexibility with regard to time and place (Turney et al. Citation2009; Newhouse et al. Citation2013; De Jong et al. Citation2014; Ng et al. Citation2014) thereby enhancing access and learning opportunities for students on and off campus and nationally and internationally. In a literature review, Spanjers et al. (Citation2015) conclude that blended learning has the potential to improve education but that, in practice, the effects on effectiveness, attractiveness, and perceived demands differed much between studies. Al-Azri and Ratnapalan (Citation2014) recommended in their review of randomized controlled trials that educators should carefully consider the role in distance learning when implementing PBL methodology.

The Faculty of Health, Medicine, and Life Sciences of Maastricht University has been actively exploring blended learning solutions for PBL-based master programs. One of the reasons is that (health) professionals should have access to education. Besides, students should get the opportunity to collaborate with international students.

In the past years, several “blended learning PBL” projects were initiated, some of which are still running. In this study, we discuss three master degree programs in the domain of health care with integrated blended learning elements:

Case 1. Master Program in Health Services Innovation (HSI).

Case 2. Master Program in Global Health (GH).

Case 3. Master Program in Health Professions Education (MHPE).

The purpose of the study is to explore blended approaches to PBL in Health Master Programs. What can we learn from these projects? The research question is: To what extent can PBL principles be applied in blended learning?

Methods and results

Research design

The present study can be seen as “real world research” (Robson Citation2002). The research is conducted in a real-life setting, rather than trying to control variables. Starting from a constructivistic framework, we analyzed the experiences of students and teachers using all available qualitative and quantitative data of three cases. Case studies are suitable “to investigate a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between the phenomenon and context are not clearly evident” (Yin Citation2003, p. 13).

gives an overview of the three blended learning master programs at the Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences of Maastricht University, presenting information about program content, participant involvement, and the communication tools used. Below the cases are presented in terms of background (embedding in faculty, target group of students, reason to move to blended learning), description of the educational methods, and evaluation results.

Table 1. Overview of details of the programs, the involvement of participants and the communication tools.

Case 1: Master of HSI

Setting

The Master of HSI (2008–2010) was designed to meet the growing need for health professionals who are able to comprehend and analyze European health care systems and determine where and how innovations can be incorporated. It consisted of six eight-week modules and a research-based thesis, and was offered as a one year full-time on-site program and as a two-year part-time program using blended learning to make the program accessible for working professionals. The part-time program was equivalent to the full-time program with respect to learning objectives, program content, requirements, exams, and diploma. The only difference was that part-time students did one module at a time whereas full-time students did two. In addition to the six modules, the program contained a statistics module and one module for thesis preparation. shows the part-time timetable.

Table 2. Overview of the HSI modules: situation in September 2009 (part-time timetable).

Educational methods

Three blended learning modules have been evaluated: Quality and professionalism (period 1; module 1); Logistics and operations management (period 2; module 2); and the statistics module (Multilevel analysis of longitudinal data and factor analysis) (period 2; module 3). These three modules can be characterized as “blended”, because online activities alternated with face-to-face activities on campus. The modules started with a one-day face-to-face meeting in which the module, the tools, and the equipment were introduced, and which included an informal meeting where students and teachers could get to know one another. In the next distance session, before the actual start of the module, tools, and equipment were tested. The “Quality and professionalism” module offered online PBL, using the traditional PBL seven-step approach we described earlier. A web conferencing tool (called Surfgroepen) was used as shown in . The participants used webcams for visual contact and could post notes and chat messages. The same technology was used in the second module. The regular two-hour lectures were recorded for the blended learners. The statistics module used asynchronous communication via a discussion board. Also in this module, students watched recorded regular lectures. Although modules 1 and 2 were more similar to traditional PBL than the statistics module, the key principles of PBL were detectable in each module. In the statistics module, self-directed learning appeared to be enhanced by the use of discussion boards, and although the learning process was structured, students were more flexible in their use of methods than in the other two modules.

Evaluation

For modules 1 and 3, the blended learning variant was compared to the face-to-face variant. In module 2 (“Logistics and operations management”) only blended learning students were participating at the time of the study. Questionnaires were used for students. Additionally, a student focus group interview was held for modules 1 and 2 to explore their views further. Faculty staff was interviewed and a summary was sent back for member checking.

Results (module 1) show that online student roles in PBL were comparable to those in the face-to-face setting. Students said face-to-face discussions did not differ from online discussions, except that spontaneous remarks were difficult online. This resulted in more explicit turn taking and discussions about how to communicate. The tutor had a double task: tutoring and managing technical equipment. Findings for module 2 confirm that collaboration was possible in spite of the distance. The freedom provided by the blended learning variant (module 3) was appreciated. Timing of tutor feedback seemed an important point for satisfaction of blended learners. More detailed information about the methods and findings are presented in .

Table 3. Results for three modules of the HSI program.

Case 2: Master Program in GH

Setting

Since 2010, the full-time Master of Science in GH has been offered in partnership with McMaster University (Canada), Manipal University (India), and Thammasat University (Thailand). Contrary to the university in Canada, the other universities are not PBL orientated. The program addresses from a global perspective the complex relationships among health, healthcare, technology, international business, economic development, politics, socio-cultural environment, and management. The 12-month program is divided into a fall (September–December), winter (January–April), and summer (May–August) term. The Maastricht fall term comprises two eight-week modules in parallel with Foundation course I and Methodology and statistics course I (). Winter term students select one of three electives at Maastricht or one of the partner universities, again in parallel with the same courses (Foundation course II and Methodology and statistics course II). The summer term is devoted to the thesis.

Table 4. Overview of the structure of the GH program (one-year program).

Educational methods

The foundation courses are delivered online and during the winter term the “Methodology and statistics course” is offered online for students undertaking electives outside Maastricht. The Foundation courses include two-weekly online lectures of one or two hours via Elluminate, a web conferencing tool. The synchronous online lectures by faculty from all over the world (e.g. Canada, England, Netherlands, and Tanzania) are followed by a synchronous online session in which students collaborate with students from partner universities supervised by a tutor from one of these universities. These sessions do not use the seven-step approach, but students discuss their work. The foundation courses are based on the PBL principles of collaborative and self-directed learning.

Evaluation

After completion of Foundation course I (academic year 2010–2011), 70 students (28 McMaster and 42 Maastricht) received an online questionnaire, 43 (61%) returned a completed questionnaire. Questions were related to collaboration and lectures. Eighty-four percent of the students reported language did not interfere with collaboration. Of the student population, 21% agreed problems in collaboration were due to differences in cultural background. Nearly 50% of the students learned as much from a lecture at a distance as from a regular face-to-face lecture. and present more detailed evaluation results.

Table 5. Results of statements about language proficiency and collaboration in Foundation course I (2010–2011) (n = 43).

Table 6. Results of statements regarding the online synchronous lectures in Foundation course I (study year 2010–2011) (n = 42).

Case 3: Master of Health Professions Education

Setting

The MHPE attracts health care professionals from all over the world, who wish to acquire the knowledge and skills for a career in health professions education and research. Students, who will be mentored by a member of the faculty staff, visit Maastricht for a maximum of three short periods (always May–June): at the start, halfway, and at the end of the program, but otherwise the part-time program is distance-based. During the 24-month program, students complete 10 modules and write a thesis. The eight-week second-year module on “Advanced quantitative and qualitative research” has been delivered online since 2011–2012. It addresses quality criteria in qualitative research, research paradigms, qualitative sampling, multiple regression analysis, exploratory factor analysis, reliability analysis, and scale construction/validation for questionnaires. The module consists of three individual assignments: a critical review of a qualitative study; statistical analysis of a given dataset; and a written report about the findings. Subsequently, students practice formulating three research questions, writing a methodology section and a reflection on a research paradigm of the student’s choice.

Educational methods

Although this deviates somewhat from traditional PBL, the learning activities focus on authentic problems and tasks that are relevant to the future work of medical education researchers. And, although students do not have to collaborate, the assignments meet the requirements of being constructive and contextual and promoting self-directed learning.

Course content and online lectures (1–2 h) are published on the intranet. Students can ask questions online during the weekly question hour, but they can also make their own learning arrangements during and after the module.

Evaluation

The module (2011–2012) we evaluated was attended by six students from different continents who knew each other from previous modules. In a face-to-face focus group interview, the students (n = 6) and the module coordinator (n = 1) were asked to talk about their experiences. The interview was summarized and was sent to the module coordinator for a member check. This resulted in recommendations that more formative feedback sessions should be integrated in the module and feedback (synchronous or asynchronous) should be on demand. A fixed question hour was not considered practical, especially for students in different continents (time difference) working part-time and studying at their own pace. Moreover, the students indicated that studying online is quite lonely. The module coordinator summarized his experiences as follows:

‘This was the first time that we offered this content in a distance module and we anticipated that it would be challenging. The students indicated that it was hard work indeed, but that in the end they had learned a lot. This was reflected in the quality of the students’ assignments.’

In summary, all cases were successful in their performance. Technique was not seen as a problem for students and faculty. The role of the teacher did change, however. Besides, the importance of feedback in online learning was also addressed. Standard lectures of 1–2 h were offered in the different master programs. No adaptation was made for online learning. Communication in online sessions compared to face-to-face sessions is different.

Discussion

In this study, we described three case studies of blended learning courses at Maastricht University (case 1: Master of HSI; case 2: Master Program in GH; case 3: MHPE). The following research question was formulated: To what extent can PBL principles be applied in blended learning? The principles contain that learning should be constructive, self-directed, collaborative, and contextual. All case studies in the present study show that both synchronous (real time) and asynchronous PBL variants were feasible, which is in line with previous studies (Savin-Baden Citation2007; Tomkinson & Hutt Citation2012). In case 1, the implementation of PBL principles was the most extensive. Face-to-face PBL at Maastricht University and the PBL used in case 1 were comparable. The seven-step approach was used in both conditions. In the other two cases, concessions to PBL principles had to be made. In case 2, the educational method should be stated as “Project-Based Learning” instead of Problem-Based Learning. Not all partners in case 2 work on a “problem-basis”. The four PBL principles, on the other hand, can be recognized in case 2. In case 3, the most concessions had to be made. This was necessary because students were in different time-zones. Besides, students were not studying in the same pace and probably had another study strategy. The “collaboration” principle was released. The other principles can be recognized. The question is whether this should be called PBL.

Below are the lessons which we have learned for developing and executing blended approaches to PBL.

Face-to-face and synchronous online tutorial group sessions are comparable

Seven-step approach

The results of case 1 indicate that synchronous online group sessions can be as effective as face-to-face sessions. The PBL student roles of discussion leader and scribe as well as the usual procedures of group learning appeared to be transferable to the online setting. According to students and tutors, the discussions were of similar depth as in face-to-face sessions. Campbell et al. (Citation2008) also reported that student attainment can be at least as successful through online discussions as through face-to-face seminars. Kear et al. (Citation2012) reported that students and tutors reacted positively to the opportunities web conferencing provides for interactive learning and teaching. Andres and Shipps (Citation2010) suggested that face-to-face meetings may still be preferable if there are no reasons to use online options.

Non-verbal communication

In online settings, the use of body language is limited (case 1). Participants have to wait their turn during discussions. This makes for more rigid behavior, which is sometimes interpreted as a negative effect, but in the cases we studied this drawback can be balanced by benefits of online learning, such as collaboration with fellow students in other continents, more flexibility, and less travel time.

Role of tutor

Tutors in case 1 remarked in the synchronous online sessions they had the double role of looking after content and technology. Kear et al. (Citation2012) also reported that tutors had to deal with multiple tasks online and technical obstacles in response to students’ emerging needs. It seems, therefore, advisable to use experienced tutors and instant technical support during sessions. As early as 2002, Barker (Citation2002) wondered whether educational institutions are providing adequate training and support for staff development in the important and rapidly growing area of online tutoring. An explorative study found that the experience of the e-tutor impacts on support of virtual online collaboration (Kopp et al. Citation2012), and another study reported a need for guidance and training of novice e-tutors (Goold et al. Citation2010).

No standard two-hour lectures: develop lectures which fit to your module content

At Maastricht University one or two-hour lectures are customary. For online lectures no adaption was made. Whether a two-hour lecture is optimal for online learning is questionable. The evaluation of online (live) lectures was reasonably positive (cases 1 and 2). The web conferencing tool was satisfactory, although students thought there was room for improvement with respect to the technical quality (image and sound) and options for interaction during lectures. Students liked the freedom that comes with the availability of recorded lectures. Savin-Baden (Citation2007) also reported that online PBL gives students more flexibility, while Bozic and Williams (Citation2011) reported that the flexibility of online methods was attractive.

Organize (face-to-face) meetings to allow students to get to know one another

The results for the GH program (case 2) indicate that collaboration problems were related to differences in students’ cultural backgrounds. The HSI program (case 1) shows that an informal face-to-face meeting (lunch, dinner) at the start of a blended learning module promotes collaboration between students and between students and teachers and helps to develop a sense of solidarity among students who otherwise study alone. When such a meeting is not feasible, other ice-breaking activities might be organized to promote communication (Suzuki et al. Citation2007). Here, we should note that the student populations in the three cases were different and, therefore, difficult to compare. All HSI students (case 1) studied at Maastricht University and were at a reachable distance from the university located. In the GH (case 2) and MHPE (case 3) programs, students from different continents were studying together.

Agreement on rules for (online) sessions: a condition for success

Agreement on (discussion) rules, such as turn taking and how to communicate, is more important for online sessions than it is for face-to-face sessions. This conclusion was especially clear from case 1. Hofgaard Lycke et al. (Citation2006) also claimed that structuring is more important in online PBL than in traditional PBL. How things are said in an online session, what is being said, and how others react – both verbally and nonverbally – affect the way in which new knowledge and information are acquired and understood (Van Til & Van der Heijden Citation2009). This is the more important in online education where communication relies primarily on the spoken word. The teacher cannot activate students via body language or eye contact, and the virtual absence of non-verbal communication can influence the course of a session. It is, therefore, important that students and teachers participating in blended learning modules know what to do and expect in online and asynchronous offline sessions. Savin-Baden (Citation2007) uses the term online etiquette (netiquette) to denote arrangements on when students are allowed or expected to talk. Staff should help students develop their own ground rules for their team. Warden et al. (Citation2013) contended that technology is not the source of problems: difficulties emerge from behaviors and their interactions with system features. It is therefore important to study behavior in distance learning as well as effects of different cultures.

Visibility and regular feedback are important

MHPE students (case 3) in particular indicated that online learning can be quite lonely. This may be explained by the fact that for these students collaboration with other students was neither compulsory nor inherent in the online method used. Wei et al. (Citation2012) emphasized the importance of social presence, reporting that it has significant effects on learning interactions, which in turn have significant effects on learning performance. Visibility of fellow students and teachers via online availability, such as Skype or a discussion board, can stimulate collaboration and continuity in studying while regular feedback keeps students on track and also stimulates them to persevere. The ability of tutors to communicate informally with students and hence create a less threatening learning environment, has a great impact on learning according to a study by Chng et al. (Citation2011). In the HSI (case 1) and MHPE programs (case 3), students mentioned the importance of feedback, and particularly the timing of feedback, which they thought should be available as soon as possible. Feedback “on demand” was recommended, especially when students are not on the same time schedule.

Limitations

The cases that were included in this explorative study were all blended learning master programs in the Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences of Maastricht University. They are not representative for blended learning programs at other levels (e.g. bachelor programs) or for programs elsewhere. Master students are more matured and curiosity-driven students, it may not make much difference whether they learn face-to-face or online. The sample sizes of students and teachers were small given the small-scale nature of the programs. A comment should also be made by the self-directedness of the programs. Is it self-directed learning? The three programs offered additional structure or support to supplement students’ self-directed learning skills in the form of strict planning, deadlines and close supervision in cases 1 and 2, and an elaborate mentor program in case 3.

Conclusions

PBL in a blended learning format is perceived to be an effective and feasible educational strategy. The four key learning principles of PBL (stimulating constructive, self-directed, collaborative, and contextual) can also be unified in PBL with a blended learning format, although the extent to which each principle can be implemented can differ depending on the structure of the educational program and the student population. Educators should carefully consider the role of distance learning in PBL education and consider several factors, including, “getting-to-know-activities at the start of education”, “lectures that are suitable for distance learning purposes”, “guidelines for behavior in online sessions”, and “the importance of visibility and feedback during education”.

Notes on contributors

Nynke de Jong PhD is a member of the e-learning group at the Faculty Health, Medicine and Life Sciences. Her research field is Problem-Based Learning and blended learning.

Daniëlle Verstegen PhD works also in the e-learning group. Her fields of interest are online and blended learning, Problem-Based Learning, MOOCs, and innovative instructional design.

Anja Krumeich PhD is a Medical Anthropologist who works in Global Health with a specific focus on the design and implementation of appropriate and contextualised innovation in health care and education. She has over 20 years of experience with international education and the use of blended learning.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the students and the faculty staff from the different health master programs at Maastricht University for their participation in this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Al-Azri H, Ratnapalan S. 2014. Problem-based learning in continuing medical education: review of randomized controlled trials. Can Fam Phys. 60:157–165.

- Andres HP, Shipps BP. 2010. Team learning in technology-mediated distributed teams. J Inform Syst Educ. 21:213–221.

- Barker P. 2002. On being an online tutor. Innovat Educ Teach Int. 39:3–13.

- Bozic N, Williams H. 2011. Online problem-based and enquiry-based learning in the training of educational psychologists. Educ Psychol Pract. 27:353–364.

- Campbell M, Gibson W, Hall A, Richards D, Callery P. 2008. Online vs. face-to-face discussion in a web-based research methods course for postgraduate nursing students: a quasi-experimental study. Int J Nurs Stud. 45:750–759.

- Chng E, Yew E, Schmidt H. 2011. Effects of tutor-related behaviours on the process of problem-based learning. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 16:491–503.

- De Grave WS, Dolmans DH, Van der Vleuten CP. 1999. Profiles of effective tutors in problem-based learning: scaffolding student learning. Med Educ. 33:901–906.

- De Jong N, Savin-Baden M, Cunningham A, Verstegen DL. 2014. Blended learning in health education: three case studies. Perspect Med Educ. 3:278–288.

- Dolmans D, Schmidt H. 2010. The problem-based learning process. In: van Berkel H, et al., editors. Lessons from problem-based learning. Oxford: University Press; p. 13–20.

- Dolmans DHJM, De Grave W, Wolfhagen IHAP, Van der Vleuten CPM. 2005. Problem-based learning: future challenges for educational practice and research. Med Educ. 39:732–741.

- Dolmans DHJM, Wolfhagen IHAP, Van der Vleuten CPM. 1998. Thinking about student thinking: motivational and cognitive processes influencing tutorial groups. Acad Med. 73:S22–S24.

- Goold A, Coldwell J, Craig A. 2010. An examination of the role of the e-tutor. Aust J Educ Technol Res Dev. 26:704–716.

- Graham CR. (2013). Emerging practice and research in blended learning. In: Moore MG, editor. Handbook of distance education. 3th ed. New York: Routledge; p. 333–350.

- Hofgaard Lycke K, Strømsø HI, Grøttum P. 2006. Tracing the tutor role in problem-based learning and PBLonline. In: Savin-Baden M, Wilkie K, editors. Problem-based learning online. Maisenhead: Open University Press; p. 45–60.

- Kear K, Chetwynd F, Williams J, Donelan H. 2012. Web conferencing for synchronous online tutorials: perspectives of tutors using a new medium. Comput Educ. 58:953–963.

- Kopp B, Matteucci MC, Tomasetto C. 2012. E-tutorial support for collaborative online learning: an explorative study on experienced and inexperienced e-tutors. Comput Educ. 58:12–20.

- Newhouse R, Buckley KM, Grant M, Idzik S. 2013. Reconceptualization of a doctoral EBP course from in-class to blended format: lessons learned from a successful transition. J Profession Nurs. 29:225–232.

- Ng ML, Bridges S, Law SP, Whitehill T. 2014. Designing, implementing and evaluating an online problem-based learning (PBL) environment – a pilot study. Clin Linguist Phonet. 28:117–130.

- Oliver M, Trigwell K. 2005. Can ‘blended learning’ be redeemed. E-Learning. 2:17–26.

- Robson C. 2002. Real world research. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Savin-Baden M. 2007. A practical guide to problem-based learning online. London: Routledge.

- Spanjers IAE, Könings KD, Leppink J, Verstegen DML, De Jong N, Czabanowska K, Van Merriënboer JJG. 2015. The promised land of blended learning: quizzes as a moderator. Educ Res Rev. 15:59–74.

- Suzuki Y, Niwa M, Shibata T, Takahashi Y, Chirasak K, Ariyawardana A, Ramesh JC, Evans P. 2007. Internet-based problem-based learning: international collaborative learning experiences. In: Oon-Seng T, editor. Problem-based learning in eLearning breakthroughs. Singapore: Seng Lee Press. p. 131–146.

- Tomkinson B, Hutt I. 2012. Online PBL: a route to sustainability education? Campus-Wide Inform Syst. 29:291–303.

- Turney CSM, Robinson D, Lee M, Soutar A. 2009. Using technology to direct learning in higher education: the way forward? Active Learn Higher Educ. 10:71–83.

- Van Til T, Van der Heijden F. 2009. PBL study skills. An overview. Maastricht, Datawyse: Universitaire Pers Maastricht.

- Warden CA, Stanworth JO, Ren JB, Warden AR. 2013. Synchronous learning best practices: an action research study. Comput Educ. 63:197–207.

- Wei CW, Chen NS. Kinshuk 2012. A model for social presence in online classrooms. Educ Technol Res Dev. 60:529–545.

- Yin RK. 2003. Case study research: design and methods. 3rd ed. Applied social research methods series, vol. 5. London: Sage.