Abstract

Background: A variety of tools have been developed to assess performance which typically use a single clinical encounter as a source for making competency inferences. This strategy may miss consistent behaviors. We therefore explored experienced clinical supervisors’ perceptions of behavioral patterns that potentially exist in postgraduate general practice trainees expressed as narrative profiles to aid the grading of clinical performance.

Methods: We conducted semistructured interviews with clinical supervisors who had frequently observed clinical performance in trainees. Supervisors were asked to describe which behavioral patterns they had discerned in excellent and underperforming trainees, during different stages of training, in their careers as clinical supervisor. We analyzed the interviews using a grounded theory approach.

Results: The analysis resulted in a conceptual framework that distinguishes between desirable and undesirable narrative profiles. The framework consists of two dimensions: doctor–patient interaction and medical expertise. Personal values appear to be a moderating factor.

Conclusions: According to experienced clinical supervisors, consistent behaviors do exist in GP trainees when observing clinical performance over time. The conceptual framework has to be validated by further observational studies to assess its potential for making robust and fair assessments of clinical performance and monitor the development of consultation performance over time.

Introduction

Workplace-based assessment (WBA) is invaluable in medical education for the evaluation of trainees’ clinical performance. Competencies consist of complex integrated knowledge and skills and are assumed to be learned and developed most effectively in authentic professional contexts (Epstein & Hundert Citation2002; van den Eertwegh et al. Citation2015). Through frequent observation and feedback on habitual performance, clinical supervisors ideally help trainees to acquire these competencies by stimulating motivation and providing direction for future learning (Norcini & Burch Citation2007; Swing Citation2010; Saedon et al. Citation2012). Therefore, the quality of feedback and supporting tools used in WBA play a crucial role in the effectiveness of progressive development of competencies and their application during clinical performance.

The implementation of outcome-based medical education, centered on competencies, has been challenging in terms of the translation of the complexities of clinical practice into descriptive frameworks that result in meaningful educational curricula, assessment practices and trainee feedback (Frank et al. Citation2010; ten Cate & Billett Citation2014). Attempts to provide a framework to guide progressive competency development and predict clinical performance over time have resulted in Entrustable Professional Activities (EPA’s) and milestones, both examples of core blueprints of a specific medical discipline in narrative developmental language (ten Cate & Scheele Citation2007; van Loon et al. Citation2014; Holmboe Citation2015). These frameworks contain the minimally required expectations for trainees at various stages of expertise development, reflecting the holistic language of clinical practice, but need to be translated into concrete criteria for observation and feedback which confronts us with two challenges (ten Cate & Billett Citation2014). First, there is still a mismatch between the intrinsic quality of instruments (e.g. checklists or rating scales) currently used during clinical observations, containing skills, knowledge and attitudes as building blocks of competences and the holistic evaluations (van der Vleuten et al. Citation2010). Many of these standardized instruments were developed to achieve valid, objective and generalizable assessments of clinical performance (Govaerts et al. Citation2007). By separating competences, complex performance may be captured in atomistic elements that do not fully appreciate the complexity (e.g. nature of the task) of the clinical performance (Durning et al. Citation2010; Ginsburg et al. Citation2010). Secondly, “zooming in” on a single encounter results in the observation of a situation-specific behavior, depend, for example, on the type of medical complaint. Contextual factors such as doctor-, patient-, and encounter-related issues have been shown to play a significant role in clinical consultations (Essers et al. Citation2011; Durning et al. Citation2012; Ginsburg et al. Citation2012). Due to this context specificity, clinical performance in one encounter is not always predictive of performance in another encounter, denoting another clinical context to be assessed (Eva Citation2003).

Hence, we need holistic assessment instruments that aim to collect rich qualitative information and target the integration of competences in diverse clinical contexts, so that the progressive aspect of learning is taken into consideration. By observing performance on repeated occasions, rich qualitative feedback on consistent behaviors can be gathered over time.

Regehr et al. (Citation2012) made an attempt to provide more detailed descriptions of a range of consistent behaviors. In their study, they used the experiences of assessors to create a shared mental model, including 16 narrative profiles representing the full range of trainee competence that clinical faculty might encounter during clinical supervision. Faculty appeared more consistent in their decisions of what constitutes excellent, competent, and problematic performance in trainees than implied by the divergent ratings of the checklists hitherto employed.

We hypothesize that a clinical supervisor potentially notices more consistent behaviors when the assessment of a trainee is based on not one, but on a series of observations (i.e., consultations). Repeated observations may allow the supervisor to gain a more generalizable insight into the trainee’s ability to integrate and adapt skills and knowledge, serving fair and defensible assessment practices. Whereas the profile descriptions by Regehr et al. (Citation2012) span all competencies of the CanMEDS framework (Frank & Danoff Citation2007), we specifically chose to narrow our exploration down to narrative descriptions of trainee behaviors during patient encounters. We did so because clinical performance represents the cornerstone of the medical profession. Hence, the present study focuses on the evaluation of trainee performance over a series of encounters with the expectation of reducing the influence of context specificity. More specifically, it aims to deliver narrative descriptions of trainee profiles as a first step in the development of a framework for guiding future learning and assessment of clinical performance.

The research questions are:

Can experienced clinical supervisors identify consistent trainee behaviors during consultations? If yes, how can these be summarized in narrative profiles?

What narrative profiles can be discerned:

in underperforming and excellent trainees?

during different stages of training?

Methods

Study context, design, and population

This study was carried out in the 3-year General Practice (GP) specialty training program in Maastricht, the Netherlands. GP specialty training in the Netherlands has a long tradition of systematic, direct observation, and feedback on trainee performance throughout the training program. The Maastricht program comprises 2 years of working in a GP teaching practice under the supervision of a clinical supervisor (year 1 and 3) and 1 year of rotations in the hospital and other medical institutions (year 2). Trainees attend modular courses at the GP specialty training institute for one day a week. Under the supervision of a GP and behavioral scientist, they participate in experiential learning sessions aimed to train their competencies through learning cycles of observation, feedback, and reflection.

In the period spanning from September 2012 to January 2013, we interviewed clinical supervisors about recurrent behavioral patterns they potentially identified among trainees. We used purposive sampling (Patton Citation2012), including experienced supervisors as our study population because they regularly observed trainee-patient encounters in daily practice. “Experienced” was defined as having observed multiple encounters of at least five different trainees they supervised during their one-year teaching practice, at different stages of training. We asked these supervisors to describe recurrent behavioral patterns they typically observed in excellent as well as underperforming GP trainees. The questions that guided the interviews are presented in Box 1. By means of probing we sought to translate rough observations into specific behaviors and to clarify described behavior. If a supervisor, for instance, mentioned that a trainee had a blank spot for everything, the interviewer would ask him or her to explain what he or she meant by that and to describe the actual behavior observed. Based on related explorative, qualitative research in medical education, we expected that a sample size of 20 interviews would suffice to reach data saturation (Ginsburg et al. Citation2010; Bombeke et al. Citation2012; Pelgrim et al. Citation2012).

Box 1 The questions that guided the semi-structured interviews which aimed to create narrative profiles

Definition of consistent behavior: ‘Consistent behavior is a description of a trainee’s behavior that is repeating over a series of encounters regardless of context’.

Interview questions:

“Have you ever discerned repeated behavior while observing a series of encounters of a trainee during your career as a clinical supervisor?”

“Please recall an excellent trainee you observed in the past. Can you describe the sort of recurrent behavior that was typical of this trainee?” By means of probing we sought to further clarify described behavior, for example: “what specific behavior did you observe?”

“Please recall an underperforming trainee you observed in the past. Can you describe the sort of recurrent behavior that was typical of this trainee?” By means of probing we sought to further clarify described behavior, for example: “what specific behavior did you observe?”

“Do you see any difference in repeated behaviors between the different stages of training? Please describe these differences”.

Ethics

We obtained ethical approval from the Ethical Review Board of the Netherlands Association for Medical Education (NVMO-ERB dossier number 193). Codes were used to anonymize the verbatim transcriptions of the recorded interviews.

Procedure

A research assistant approached the clinical supervisors by telephone, providing information about the purpose and content of the study, and inviting them to participate. After informed consent was obtained, an appointment was made at the training institute or the clinical supervisor’s practice. Prior to the appointment, a format of the interview was sent by e-mail. 30 to 60 min was allotted per interview. The first author (MO) conducted the interviews in Dutch. A test interview, which we excluded from the analysis, was conducted to check the appropriateness and feasibility of the guiding questions. All interviews were audio-taped, recordings were transcribed verbatim and potentially private data were deleted. MO checked the transcribed scripts against the content of the audiotapes.

Analysis

We used the Constant Comparative Method, derived as part of the Grounded Theory approach (Corbin & Strauss Citation2008; Watling & Lingard Citation2012), to analyze the interviews. We chose this method as we wanted to inductively develop a new conceptual framework to describe narrative profiles (Corbin & Strauss Citation2008; Charmaz Citation2012). Since the establishment of a conceptual framework is grounded in shared experiences and interaction between the researchers, data and participants, we provide the following contextual information: the lead author (MO) is a general practitioner; her collaborators have significant experience in studying research in medical education and their disciplinary backgrounds are general practice (PD, BM, JM) and psychology and psychometrics (CvdV). Data collection and data analysis took place concurrently in an iterative fashion so that new information could be incorporated into subsequent interviews (Watling & Lingard Citation2012). Of the 19 clinical supervisors who volunteered to participate, one was unable to participate for personal reasons, resulting in a total of 18 participants: 5 female and 13 male supervisors. All met the inclusion criteria; their experience of supervising trainees varied from 5–34 years.

Data saturation was achieved after 15 interviews, as no new codes emerged from the analysis of the last three interviews. Two researchers (MO and PD) analyzed the transcripts. MO coded all interviews, PD did nine. First, they independently reviewed and coded the interviews (open coding). In an iterative process, they then discussed and refined the codes found (Watling & Lingard Citation2012). Inconsistencies in coding were discussed with BM, who read part of the interviews. Codes persisted if consensus was reached between the researchers. Next, we continuously compared and interpreted the codes and their interrelationships to arrive at comprehensive themes (axial coding).

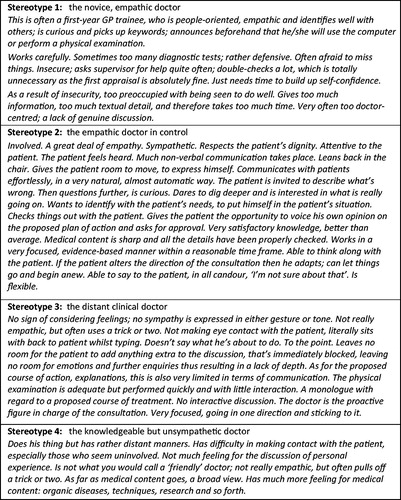

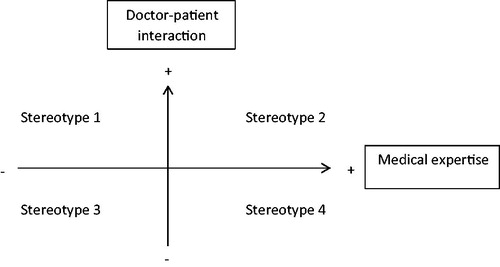

Based on these themes, we developed a conceptual framework to illustrate their hypothesized interrelationships. Throughout the data collection and analysis we used memos to record observations, thoughts, ideas, interpretations, hypotheses and questions. Finally, we created stereotypes that represent the extremes (underperforming versus excellent) of the conceptual framework to illustrate to the reader the meaning of the identified dimensions (i.e. axes). We (MO, PD) did so by placing all the original open codes identified during our grounded theory analysis along the axes of the conceptual framework. We then looked up the codes pertaining to the dimensions’ extremes in the original interviews to collect for each stereotype corresponding quotes of identifying behaviors. Hence, a stereotype comprises a strategic combination of various quotes and, as such, does not represent any of the real trainees described in the interviews.

Results

During the interviews, all supervisors immediately and unanimously recognized the existence of recurrent behavioral patterns in GP trainees during consultations. From their descriptions two themes emerged that translated into two dimensions of recurrent behaviors GP trainees typically exhibited during clinical encounters. These dimensions were “doctor–patient interaction” and “medical expertise”. The first dimension encompasses behavioral descriptors of the interpersonal relationship between doctor and patient, including verbal and non-verbal communication, structuring the consultation, and active listening (Kurtz et al. Citation2003). Medical expertise can be described in terms of behaviors concerning history taking, the physical examination, diagnostic, and therapeutic knowledge which are consistent with current general practice guidelines/standards (van Thiel et al. Citation1991). We regularly observed that supervisors described behavioral characteristics that are related to single dimension. Together, they constitute a growth model that can be depicted as a conceptual framework, as illustrated in .

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of dimensions classifying recurrent behavioral patterns in trainee performance.

Moreover, we identified personal values as a moderating factor in the trainee’s position with respect to the dimensions of doctor–patient interaction and medical expertise. Personal values and beliefs in this sense refer to views about social status, prejudice, and self-esteem (Novack et al. Citation1997; Epstein Citation2003). According to the supervisors, personal values can either inhibit or facilitate the development toward adequate doctor–patient interaction and medical expertise in the specific consultation context. The following sections will expound on the two dimensions and moderating factor, respectively, as well as on their respective positions on the axes of the conceptual framework.

Explanation of the model

“Doctor–patient interaction” dimension

The first dimension (vertical axis) encompasses consistent behaviors of doctor–patient interaction and describes interpersonal relationship between doctor and patient, including the extent to which the trainee adequately connects with the patient, in terms of both verbal and nonverbal communication. In describing excellent trainees, supervisors began by characterizing them as “inquisitive”. These trainees engaged in active listening and did not stop until the story was complete. They dared to dig deeper and were interested in what was really going on for the patient. They were genuinely interested and possessed a great deal of empathy, as expressed by how they made eye contact with the patient, nodded and applied an explorative questioning technique. This “excellent” profile is positioned on the upper end of the vertical axis. In the words of one of the supervisors “…it was a matter of word choice and the accompanying intonation as well as the gestures that were used. Something was happening in the interaction between doctor and patient” (interview 9).

At the other end of the dimension, supervisors described underperforming trainees as a “distant” or “clinical” doctor. During observation, they noticed the trainee did not thoroughly explore the problem presented and was too easily satisfied. Not enough attention was paid to the perceptions and feelings of the patient. The interaction was usually one-way: the trainee dominated the conversation and overloaded the patient with medical information. This profile is positioned on the lower end of the diagram and was captured by one of the supervisors as follows:

[The trainee shows] no sign of considering feelings; no sympathy is expressed in either gesture or tone. Literally sits with his back to the patient whilst typing. Looking at the computer; not making any eye contact with the patient. Doesn’t say what he’s about to do. The doctor is already sitting at the computer, busy typing, when the patient asks: ‘Doctor, may I get dressed now?’ (interview 7).

“Medical expertise” dimension

The second dimension is medical expertise (horizontal axis). This dimension involves consistent behaviors demonstrating the extent to which both the context of the symptom is taken into consideration and the trainee is able to work in a goal-oriented manner, in accordance with current general practice guidelines/standards. Regarding medical expertise, excellent trainees not only performed well on separate skills, but were also capable of integrating them. The trainees were able to select those diagnostic and therapeutic tools that were needed in a specific encounter. As one of the supervisors framed it:

This trainee impressed me by finding the right balance between keeping his medical knowledge continuously focused and checking each detail one by one, skillfully handling the encounter, having a keen sense for medical knowledge, being comprehensive, not missing anything. I say, if someone visits you because he is experiencing shortness of breath, let him also perform a review of systems, be complete. Yes, that is what I mean. In accordance with the standards, going about in an evidence-based fashion (interview 29).

Conversely, trainees were perceived to lack medical expertise, or to underperform with respect to this dimension (positioned on the left-hand side of the horizontal axis), when they indiscriminately worked through history-taking lists, performed physical examinations nonsystematically and lacked vital knowledge. The following passage describes such a trainee:

This is an individual who is unable to abstract concepts – it is difficult to describe – someone who just cannot apply clinical reasoning. So, if a patient reported a whole range of complaints, the trainee would pick out just one of these, which specific complaint would then become the only point of focus. Let me take a simple example: if a patient complained of dizziness, chest-pain and not feeling well, then the chest-pain and the not feeling well were ignored, whilst the dizziness was exhaustively investigated, even though this symptom was only a side-effect. This behaviour resurfaced in every consultation, signalling a pattern (interview 14).

Personal values as moderating factor

When asked what could cause underperforming and excellent trainees to exhibit different recurrent behaviors, supervisors answered that personal values acted as a discriminating factor. Excellent trainees are able to reflect on their own performance and often have a broad social interest in daily life, as the following quote illustrates:

These trainees are curious, explore a lot and are able to set aside their personal prejudices. Medically, they have a broader overview, and do not cling to a potential diagnosis. These trainees were well-prepared at the start of the encounter as they had already read the patient’s medical chart (interview 13).

Supervisors mentioned the cultural background of trainees as an example of personal values that negatively influenced doctor–patient interaction and medical expertise, causing trainees to underperform. Consider the next quote, for instance:

A trainee … had been a doctor in another country where doctors are figures of authority and what they say, goes. End of discussion. The doctor really sat on high, ay? It was a matter of, ‘Well, madam, listen. This is the way things are and this is what is going to happen’. That’s it (interview 12).

Limited doctor–patient interaction was described in both underperforming and excellent trainees. The reason behind such limited interaction determined whether a supervisor labeled a behavioral pattern as worrisome or not. In excellent trainees, the supervisor often attributed limited interaction and overload of information to a lack of self-confidence. This was especially the case for first-year female trainees, who repeatedly sought reassurance from their clinical supervisors, although the latter believed it unnecessary, feeling they already had sufficient medical expertise. Supervisors did not worry, stating that these trainees just needed time and experience to become more self-confident. When underperforming trainees failed to interact sufficiently with patients, however, this was described by supervisors as defensive and judgmental behavior and a lack of empathy. Supervisors were concerned as practice and supervision did not seem to help these trainees improve on the described dimensions.

Development of consistent behaviors during the stages of traineeship learning

Clinical supervisors reported that they had noted changes in the behavioral patterns trainees typically exhibited as they progressed from the first to the third year of training. The next paragraphs will describe how trainees’ performance during consultations in specialty training gradually developed, as perceived by supervisors.

In the initial phase of training, trainees almost exclusively focused on the art of history taking, to be sure they did not miss any medical problem. As a consequence, their minds were fully occupied with history-taking lists, leaving too little room to consider other aspects of a consultation as well, as cognitive space is limited. This, in turn, caused doctor–patient interaction to be very limited: with too little perceptive capacity to explore the patient’s concerns, beliefs, and emotions, the trainee was unable to pick up keywords in the conversation, let alone adjust his or her agenda and respond flexibly to the patient’s needs. During the course of the educational program, medical expertise increased, and trainees gradually developed this perceptive capacity. The mastery of medical expertise seemed to open doors to adequate interaction. When taking a history, trainees relied less and less on standard checklists and sometimes even deliberately left out questions. Hence, their history-taking skills had become integrated into their clinical repertoire. In addition, trainees expanded their use of therapeutic strategies to include watchful waiting, referral, reassurance, and education. By the end of training, they increasingly dared to abandon their doctor’s agenda and standard checklists and pay more attention to the patient’s emotions and concerns.

During the analysis of the interviews, we searched for a term to denote the trainee’s ability to keep control of the consultation, while adjusting his or her behavior (i.e. performance) to the demands of the specific context. The term “contextual adaptation” seemed to fit best and the following characteristics were found to be associated with it: picking up keywords, resonating with the patient by adjusting to the (unexpected) course of the consultation, e.g. if the patient suddenly presented another complaint or showed emotion.

Trainees who were not very proficient in contextual adaptation were said to go in one direction during the consultation and stick to their own agenda. These trainees did not leave any room for the patient to add anything extra to the discussion, as this was immediately blocked. Their mindset was well captured by one of the supervisors: “The person who sets the agenda should control it, manage the conversation and decide in which direction it should go, ay? There can be no other way than the path the doctor decides to follow” (interview 17).

Excellent trainees, by contrast, demonstrated an ability to pick up patient cues early in the program, as illustrated by the following quote:

Relatively, he gives the patient a lot of room to manoeuvre and yet manages, subtly, to control the structure of the consultation. He is flexible. If the consultation turns in a particular direction, he is able to follow, to adjust. He is able to let something go and start off again (interview 13).

Stereotypes

The dimensions have been visualized along the horizontal (medical expertise) and vertical (doctor–patient interaction) axes of a conceptual framework, with each of the four quadrants representing a stereotype (see ). The quadrants were defined by measuring performance on both dimensions. Profile 1, for instance, represents a stereotypical trainee who is proficient in doctor–patient interaction, but has limited medical expertise.

Discussion

During the interviews, clinical supervisors immediately and unanimously confirmed that they were able to discern recurrent behaviors trainees typically exhibited during consultations. These behavioral patterns, moreover, contained two dimensions, specifically “doctor–patient interaction” and “medical expertise”, resulting in four narrative profiles. The results of this study potentially impact the way clinical performance is taught and assessed, by offering new ways to provide feedback which is more focused because it is based on behaviors consistently exhibited over different consultation contexts.

From a holistic point of view, this study shows that a more relevant picture of a trainee’s competency development can be obtained if the assessment focuses on behaviors consistently exhibited over several patient encounters rather than on separate skills demonstrated in a single consultation. Such approach would provide insight into the trainee’s ability to integrate and adapt knowledge and skills during patient encounters. By paying attention to the contextual factors presented, the supervisor will gain insight into the trainee’s ability to adjust behavior in the specific encounter, which is expected to result in a more realistic and fair assessment. As Schuwirth and van der Vleuten (Citation2006) plead, performance variability resulting from interaction with contextual factors should not be dismissed as “measurement error”, but considered as potentially valuable and meaningful information in the appreciation of an individual's professional competence (Schuwirth & van der Vleuten Citation2006). The reason for this is that medical expertise and communication skills may be applied differently, depending on the context of the clinical encounter, and a trainee first needs to develop the ability to integrate these competences flexibly during the training program, a process also coined “contextual adaptation” (Zoppi & Epstein Citation2002; Salmon & Young Citation2011).

Nowadays, supervisors are still forced to convert contextualized perceptions of overall performance into judgments of predefined domains of skills with an ordinal score. While these predefined domains can be useful in providing easily communicable descriptions of a trainee’s ability (Govaerts & van der Vleuten Citation2013), they may not match the observer’s cognitive processes and real clinical practice, often focused on holistic and integrated conceptualizations of competence, viewing the whole picture of trainee functioning (Gingerich et al. Citation2011). A turn to narrative feedback on consistent behaviors will allow the supervisor to abandon these predefined domains and “zoom out”. The reason is that narrative feedback is based on an integrated picture of clinical performance over several consultation contexts. A closer alignment between supervisors’ cognitive processes and the structure of observation tools would probably result in a more valid and authentic assessment of workplace-based learning, rendering feedback a more powerful predictor of future progress, and a better stimulus for trainee learning (Govaerts et al. Citation2011).

In embracing the use of narrative feedback on consistent behaviors and moderating factors for teaching and assessment purposes, however, one should consider its inherent potential pitfall, that is, the feedback can be very personal for a trainee. Feedback on the personal level is known to be less effective as it does not always contain directions for future learning and it causes trainees to be overly heedful of risks and failure (Hattie & Timperley Citation2007). Hence, in order for feedback on recurrent behaviors to be effective in the first place, it is vital that a safe and stimulating learning environment should be created with transparent and realistic educational goals.

During their training trajectory, trainees learn to harness the same skills adaptively to achieve desired clinical outcomes across a variegated range of clinical encounters and internalize this ability (Street & De Haes Citation2013; Wouda & van de Wiel Citation2013; van den Eertwegh et al. Citation2014). Making use of narrative profiles when observing performance during consultations could help the supervisor to gain insight into the extent to which a behavior has become an internalized and integrated part of the trainees’ clinical repertoire, using it flexibly in different contexts, and to signpost learning needs. Such observations, for instance, could focus on the extent to which the trainee is able to structure the consultation or to engage in shared decision-making. Therefore, to optimize the transfer of learning, it is important that facilitating and inhibiting factors should be effectively tackled.

Exploring the origin of a recurrent behavioral pattern may help to identify what learning activities need to be undertaken to change undesirable behavior. Decreased doctor–patient interaction can be a result of limited cognitive capacity (too busy with checklists), insecurity (too preoccupied with pinpointing the medical problem) or personal beliefs (doctor knows best) on the part of the trainee. If cognitive space is limited due to a lack of medical knowledge, having a downward effect on doctor–patient interaction, then the trainee’s primary learning goal should be to improve his or her medical knowledge. In such situation it will not work to focus more sharply on the training of doctor–patient interaction, as the trainee simply does not have enough cognitive space to devote attention to this. If the trainee adopts a doctor-centered style out of personal beliefs, a totally different approach is needed. In such cases, it is important to speak to the reflective capacity of the trainee, as this is known to play a critical role in the effectivity of feedback (Anseel et al. Citation2009; Eva et al. Citation2012; Harrison et al. Citation2015). As a potential remedy, one could offer the trainee intensive coaching by a clinical supervisor and feedback from peers and trainers to stimulate critical reflection on personal views related to professional functioning. Finally, insecurity as a cause of decreased interaction during patient encounters often fades as medical expertise is increased and sufficient clinical experience is gained.

Strengths and limitations

In this study, we constructed a conceptual framework based on interviews with clinical supervisors who regularly observed trainees to perform in practice. This enabled us to collect a large amount of information about recurrent behaviors, based on real-life clinical experience.

The fact that all participants were affiliated to the same GP specialty training institute may raise concerns over limited generalizability of the results; however, all respective programs in the Netherlands show much resemblance in terms of methods and training standards. All supervisors in our study were used to working with a generic scoring instrument, the Maasglobal scoring list (van Thiel et al. Citation1991), when observing trainees manage a clinical consultation. The language they used to describe consistent behaviors may have been influenced by the content of this instrument, which uses generic, broadly described terms, diminishing the likelihood of bias toward descriptive terms used. Although the development of a framework for narrative profiles in clinical performance in a GP specialty training setting has generally shown promising results, the framework needs to be validated further in similar and other medical specialty training settings. Likewise, concrete behavioral descriptors of the stereotypes need to be defined.

Conclusions

The strength of this study lies in the creation of a conceptual growth model for the development of clinical competence, which classifies recurrent behaviors during consultations into the dimensions “medical expertise” and “doctor–patient interaction”, resulting in descriptions of four stereotypical trainee profiles, in which personal values appear to be a moderating factor. This framework has the potential to assist supervisors in providing narrative feedback, paying attention to the development of a trainee’s ability to flexibly adapt to the peculiarities of the clinical context (i.e., contextual adaptation). In order to explore the future educational utility of the construct of repeated behaviors, the conceptual framework needs to be validated by further observational studies of real-life patient encounters. Finally, it is imperative to assess whether this holistic model fits the longitudinal development of trainees before creating narrative observation scales to support training and assessment practices.

Ethical approval

We obtained ethical approval from the Ethical Review Board of the Netherlands Association for Medical Education (NVMO-ERB).

Glossary

Medical interview: A comprehensive method that explicitly integrates clinical tasks (history taking, physical examination, and medical problem solving) with effective communication skills. It incorporates patient-centered medicine into both process and content aspects of the consultation.

Silverman J, Kurtz S, Draper J. 2013. Skills for communicating with patients. 3rd edition. CRC Press.

Notes on contributors

Marjolein Oerlemansw, MD, is a GP in the Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands

Patrick Dielissen, MD, PhD, is a GP and a scientist in the Department of Primary and Community Care, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands

Angelique Timmerman, PhD, is a psychotherapist and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands

Bas Maiburg, MD, PhD, is a GP and an Associate Professor in the Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands

Paul Ram, MD, PhD, is a GP and an Associate Professor in the Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands

Jean Muris, MD, PhD, is a GP and a Professor of Asthma and COPD in Primary Care in the Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands

Cees van der Vleuten, PhD, is a Professor of Medical Education at the School of Health Professions Education, Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Helga Liégeois, research assistant, for her support.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Anseel F, Lievens F, Schollaert E. 2009. Reflection as a strategy to enhance task performance after feedback. Org Behav Hum Dec. 110:23–35.

- Bombeke K, Symons L, Vermeire E, Debaene L, Schol S, De Winter B, Van Royen P. 2012. Patient-centredness from education to practice: the 'lived' impact of communication skills training. Med Teach. 34:e338–e348.

- Charmaz K. 2012. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage publications.

- Corbin J, Strauss A. 2008. Basics of qualitative research. Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Durning SJ, Artino AR, Boulet JR, Dorrance K, van der Vleuten C, Schuwirth L. 2012. The impact of selected contextual factors on experts' clinical reasoning performance (does context impact clinical reasoning performance in experts? Adv Health Sci Educ. 17:65–79.

- Durning SJ, Artino AR, Jr., Pangaro LN, van der Vleuten C, Schuwirth L. 2010. Perspective: redefining context in the clinical encounter: implications for research and training in medical education. Acad Med. 85:894–901.

- Epstein RM. 2003. Mindful practice in action II:cultivating habits of mind. Fam Sys & Health. 21:11–17.

- Epstein RM, Hundert EM. 2002. Defining and assessing professional competence. jama. 287:226–235.

- Essers G, van Dulmen S, van Weel C, van der Vleuten C, Kramer A. 2011. Identifying context factors explaining physician's low performance in communication assessment: an explorative study in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 12:138.

- Eva KW. 2003. On the generality of specificity. Med Educ. 37:587–588.

- Eva KW, Armson H, Holmboe E, Lockyer J, Loney E, Mann K, Sargeant J. 2012. Factors influencing responsiveness to feedback: on the interplay between fear, confidence, and reasoning processes. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 17:15–26.

- Frank JR, Danoff D. 2007. The CanMEDS initiative: implementing an outcomes-based framework of physician competencies. Med Teach. 29:642–647.

- Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, Holmboe ES, Carraccio C, Swing SR, Harris P, Glasgow NJ, Campbell C, Dath D, et al. 2010. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 32:638–645.

- Gingerich A, Regehr G, Eva KW. 2011. Rater-based assessments as social judgments: rethinking the etiology of rater errors. Acad Med. 86:S1–S7.

- Ginsburg S, Bernabeo E, Ross KM, Holmboe ES. 2012. “It depends”: results of a qualitative study investigating how practicing internists approach professional dilemmas. Acad Med. 87:1685–1693.

- Ginsburg S, McIlroy J, Oulanova O, Eva K, Regehr G. 2010. Toward authentic clinical evaluation: pitfalls in the pursuit of competency. Acad Med. 85:780–786.

- Govaerts M, van der Vleuten CP. 2013. Validity in work-based assessment: expanding our horizons. Med Educ. 47:1164–1174.

- Govaerts MJ, Schuwirth LW, Van der Vleuten CP, Muijtjens AM. 2011. Workplace-based assessment: effects of rater expertise. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 16:151–165.

- Govaerts MJ, van der Vleuten CP, Schuwirth LW, Muijtjens AM. 2007. Broadening perspectives on clinical performance assessment: rethinking the nature of in-training assessment. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 12:239–260.

- Harrison CJ, Konings KD, Schuwirth L, Wass V, van der Vleuten C. 2015. Barriers to the uptake and use of feedback in the context of summative assessment. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 20:229–245.

- Hattie J, Timperley H. 2007. The power of feedback. Rev Educ Res. 77:81–112.

- Holmboe ES. 2015. Realizing the promise of competency-based medical education. Acad Med. 90:411–413.

- Kurtz S, Silverman J, Benson J, Draper J. 2003. Marrying content and process in clinical method teaching: enhancing the Calgary-Cambridge guides. Acad Med. 78:802–809.

- Norcini J, Burch V. 2007. Workplace-based assessment as an educational tool: AMEE Guide No. 31. Med Teach. 29:855–871.

- Novack DH, Suchman AL, Clark W, Epstein RM, Najberg E, Kaplan C. 1997. Calibrating the physician. Personal awareness and effective patient care. Working Group on Promoting Physician Personal Awareness, American Academy on Physician and Patient. jama. 278:502–509.

- Patton M. 2012. Qualitative evaluation and research methods thousand oaks. CA: Sage Publications.

- Pelgrim EA, Kramer AW, Mokkink HG, van der Vleuten CP. 2012. The process of feedback in workplace-based assessment: organisation, delivery, continuity. Med Educ. 46:604–612.

- Regehr G, Ginsburg S, Herold J, Hatala R, Eva K, Oulanova O. 2012. Using “standardized narratives to explore new ways to represent faculty opinions of resident performance” . Acad Med. 87:419–427.

- Saedon H, Salleh S, Balakrishnan A, Imray CH, Saedon M. 2012. The role of feedback in improving the effectiveness of workplace based assessments: a systematic review. BMC Medical Education. 12:25.

- Salmon P, Young B. 2011. Creativity in clinical communication: from communication skills to skilled communication. Med Educ. 45:217–226.

- Schuwirth LW, van der Vleuten CP. 2006. A plea for new psychometric models in educational assessment. Med Educ. 40:296–300.

- Street RL, Jr, De Haes HC. 2013. Designing a curriculum for communication skills training from a theory and evidence-based perspective. Patient Educ Couns. 93:27–33.

- Swing SR. 2010. Perspectives on competency-based medical education from the learning sciences. Med Teach. 32:663–668.

- ten Cate O, Billett S. 2014. Competency-based medical education: origins, perspectives and potentialities. Med Edu. 48:325–332.

- ten Cate O, Scheele F. 2007. Competency-based postgraduate training: can we bridge the gap between theory and clinical practice? Acad Med. 82:542–547.

- van den Eertwegh V, van Dalen J, van Dulmen S, van der Vleuten C, Scherpbier A. 2014. Residents' perceived barriers to communication skills learning: comparing two medical working contexts in postgraduate training. Patient Educ Couns. 95:91–97.

- van den Eertwegh V, van der Vleuten C, Stalmeijer R, van Dalen J, Scherpbier A, van Dulmen S. 2015. Exploring residents' communication learning process in the workplace: a five-phase model. PLoS One. 10:e0125958.

- van der Vleuten CP, Schuwirth LW, Scheele F, Driessen EW, Hodges B. 2010. The assessment of professional competence: building blocks for theory development. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 24:703–719.

- van Loon KA, Driessen EW, Teunissen PW, Scheele F. 2014. Experiences with EPAs, potential benefits and pitfalls. Med Teach. 36:698–702.

- van Thiel J, Kraan HF, Van Der Vleuten CP. 1991. Reliability and feasibility of measuring medical interviewing skills: the revised Maastricht History-Taking and Advice Checklist. Med Edu. 25:224–229.

- Watling CJ, Lingard L. 2012. Grounded theory in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 70. Med Teach. 34:850–861.

- Wouda JC, van de Wiel HB. 2013. Education in patient-physician communication: how to improve effectiveness? Patient Educ Couns. 90:46–53.

- Zoppi K, Epstein RM. 2002 . Is communication a skill? Communication behaviors and being in relation. Fam Med. 34:319–324.