Abstract

Background: In medical education, students need to acquire skills to self-direct(ed) learning (SDL), to enable their development into self-directing and reflective professionals. This study addressed the mentor perspective on how processes in the mentor–student interaction influenced development of SDL.

Methods: n = 22 mentors of a graduate-entry medical school with a problem-based curriculum and longitudinal mentoring system were interviewed (n = 1 recording failed). Using activity theory (AT) as a theoretical framework, thematic analysis was applied to the interview data to identify important themes.

Results: Four themes emerged: centered around the role of the portfolio, guiding of students’ SDL in the context of assessment procedures, mentor-role boundaries and longitudinal development of skills by both the mentor and mentee. Application of AT showed that in the interactions between themes tensions or supportive factors could emerge for activities in the mentoring process.

Conclusion: The mentors’ perspective on coaching and development of reflection and SDL of medical students yielded important insights into factors that can hinder or support students’ SDL, during a longitudinal mentor–student interaction. Coaching skills of the mentor, the interaction with a portfolio and the context of a mentor community are important factors in a longitudinal mentor–student interaction that can translate to students’ SDL skills.

Introduction

Although it is widely acknowledged that mentoring in academic medicine is beneficial for personal development, self-directed learning, workplace-based learning, and career success (Buddeberg-Fischer & Herta Citation2006; Sambunjak et al. Citation2006; Overeem et al. Citation2009; van Schaik et al. Citation2013), the processes or mechanisms fundamental to these positive effects are less well understood (Sambunjak et al. Citation2010). Many studies thus far have addressed the mentee’s perspective on these positive outcomes. Studies on the mentor’s perspective on processes that make mentoring effective have focused on the benefits for the mentor, showing a better understanding of the institute (in the context of a telecommunication and a health organization) by the mentor (Eby & Lockwood Citation2005), and a personal learning experience of the mentor (in the context of accounting business), especially in longer relationships (Allen & Eby Citation2003). Mentors in academic medicine benefited from the network of mentors and improved their coaching skills, such as presenting feedback and interviewing skills (Connor et al. Citation2000; Overeem et al. Citation2010). The processes that are important in this personal learning of the mentor are less well known, especially from the mentors’ perspective.

It is likely that the context of the mentoring process is also an important factor, for example how long is the mentor–mentee interaction operational, and how is the mentoring system embedded in the context of the curriculum. In medical education, mentoring is often used in the context of self-directed and reflective learning. In self-directed learning, the learner diagnoses the learning needs, sets learning objectives, decides how to evaluate the learning outcome, identifies a suitable learning strategy and evaluates the outcome (O’Shea Citation2003). In this process, reflection is a vital component, as then the learner will critically examine the processes that occurred before, during and after a certain incident, to come to an understanding of the “self” and to make changes for future incidents (Mann et al. Citation2009; Sandars Citation2009). Mentoring is well known to support and enhance reflective learning (Driessen et al. Citation2007; Kalén et al. Citation2012; Sargeant et al. Citation2015). Reflective activities of the mentee are often embedded in the context of a portfolio. The portfolio has been described as a vulnerable context of teaching and learning, as the chosen format, timing, quality of mentors’ feedback, and mentee and mentor interaction and engagement are important factors for fitness for purpose (van Schaik et al. Citation2013; Arntfield et al. 2016). How the portfolio itself is used in mentoring processes is also expected to be important, especially in a longitudinal setting. In most contexts, the portfolio is associated with some form of assessment, in which the mentor may play a role. Although there is some evidence on potential conflicts in the role of a mentor as an assessor or as a coach (Bray & Nettleton Citation2007), it is less clear if and how the portfolio itself and the assessment of a portfolio, affects the mentoring processes and the development of self-regulation of learning.

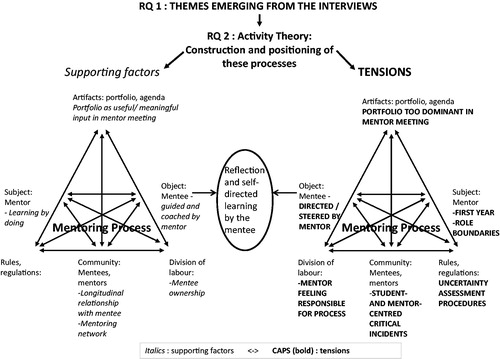

Given that contextual factors are likely to determine and affect mentoring processes, it is important to study the process in the context itself using a suitable theoretical framework. Activity theory (AT) offers a scaffold to understand human action and learning, considering both the individual and the social and cultural context (Engeström Citation2001; Johnston & Dornan Citation2015). The unit of analysis is the activities of participants (subject) in the specific context, and its tools, rules and roles (Battista Citation2015). In the mentoring process, the object is the mentee to be coached toward self-directed and reflective learning, by the subject, the mentor. Tools, rules and roles can be envisioned as the use of a portfolio, the mentor meetings, the assessment procedures and the mentor as an assessor or coach. AT offers a framework to study how the activities in the mentoring process impact learning and developmental processes of the participants.

Therefore, to get more insight in the mentor perspective on the coaching of self-regulation of learning, reflection and use of a portfolio in the context of a longitudinal relationship, we performed a study to answer the following research questions: (1) how do mentors view the processes in the development of self-regulation of learning that occur during the longitudinal relationship with their mentees? and (2) How can AT explain the construction and positioning of these processes?

Methods

Setting

This study was performed at Maastricht University, The Netherlands. The participants were mentors in the graduate-entry program Physician-Clinical Investigator, which is a 4-year medical course. The curriculum uses problem-based and workplace-based learning and is competency-based, using the CanMEDS framework (Frank Citation2005; van Herwaarden et al. Citation2009). Students are appointed the same mentor for 4 years. The assessment program of the course is designed according to the principles of programmatic assessment (van der Vleuten & Dannefer Citation2012; van der Vleuten et al. Citation2012). Briefly, all assessment and feedback information, such as progress test results, course assessments, feedback on assignments, narrative feedback from peers and teachers, multi-source feedback rounds, workplace-based evaluations (in the clinical years) are collected and aggregated in an electronic portfolio. Students are asked to use all assessment and feedback information that the curriculum generates, to self-regulate their learning. This regular process of reflection is captured in the portfolio, which is used in the mentor meetings throughout the year. Mentors meet with their student five times in Year 1 (39 weeks of PBL-based pre-clinical education), three times in Year 2 (27 weeks, patient-based preclinical education), four times in Year 3 (64 weeks, clinical rotations), and two times in Year 4 (30 weeks, senior elective clinical rotation). All assessment and feedback information is designed to be informative for learning and individual assessment moments or feedback is not linked to formal pass–fail decisions. Students receive an indication of progress and feedback halfway through the year from another, “second” mentor. The second mentor reads the portfolio and is present at the meeting with the personal mentor. The purpose of the second mentor is twofold: (i) the formal indication on progress and feedback of this independent mentor offers an opportunity for the student to remediate possible shortcomings during the year, and (ii) it enables mentors to view other portfolios and gives opportunity to see other mentors at work and get feedback on their own performance. At the end of the Year, the personal mentor also gives an indication of progress and feedback. The portfolio and these two indications are discussed in a plenary meeting of all mentors of the Year group. Each portfolio is assigned to a mentor (not being the personal mentor or the second mentor), this mentor will prepare the portfolio and present it to the group, showing examples of results or reflective activities. After discussion with the group of mentors, a third formal indication of progress and competency development is formulated. The portfolio and these three indications are then forwarded to an independent portfolio assessment committee, that give a summative assessment of the portfolio, a pass or fail, which is coupled to a (high-stake) promotion decision.

Mentors are faculty members with a PhD degree, working as a clinician-investigator in the university hospital or as an investigator/scientist in a research group of the university. Every mentor has 4–10 students, with no more than 5 students in the same year group. There is a yearly training in coaching and interviewing techniques at the beginning of the year that all mentors attend. Every new mentor in the course is coupled to an experienced mentor (‘buddy’), as a first contact for questions. During the year, there are five mentor meetings, in which one topic is discussed (e.g. giving an indication on progress halfway through the year) and there is opportunity to exchange experiences and sharing of stories.

Data collection and analysis

A qualitative design was chosen to investigate the research question. Individual interviews were used to explore experiences of the mentors in their natural context (Malterud Citation2001), using an interpretative, constructivist approach (Bunniss & Kelly Citation2010). All mentors (n = 24) were invited for individual interviews, n = 22 responded positively, n = 2 were unable to plan the interview. Mentors had 1–7 years of experience. Between March and June 2014, the second author (W.d.G.) performed the interviews, using a semi-structured set of open questions. The interviews lasted approximately 60 min. There were n = 21 interviews (n = 9 males, n = 12 females) available for analysis as 1 recording failed and could not be transcribed.

Verbatim transcripts of the interviews were made and analyzed using Template Analysis, which consists a succession of coding templates and hierarchically structured themes that were applied to the data (King Citation2004). For the specific research question of this paper, a set of predefined codes was based on literature (Allen & Eby Citation2003; Sambunjak et al. Citation2006; Allen Citation2007; Sambunjak et al. Citation2010; van Schaik et al. Citation2013; Eby et al. Citation2014) and shown in . Analysis of interview 1–3 (by S.H. and W.d.G.) using the pre-defined codes resulted in an initial template part I that was thoroughly discussed and then applied to interview 4–6 (by S.H. and W.d.G.). After discussion, this resulted in the initial template part II, which was used in interview 7–19 (coding by W.d.G.) and discussed (S.H. and W.d.G.). The outcome of that analysis was a final template, which was confirmed by the analysis of interview 20–22 (by S.H.).

Table 1. Set of pre-defined codes, used for the initial template.

After this inductive analysis of the data, AT was used as a theoretical lens to further study how the mentoring process (action) is mediated by the tools, rules and roles in the context of a longitudinal portfolio-based mentoring system, as perceived by the mentor (subject) (Jones et al. Citation2014; Battista Citation2015).

Ethical considerations

Participation was voluntary and mentors were ensured of confidentiality and signed an informed consent form. The ethical review board of the Dutch Association for Medical Education approved this study (approval NVMO-ERB-341). The researchers were educationalists (W.d.G.), and a biologist with an educational background (S.H.). S.H. had contact with the mentors as the program director of the Physician-Clinical Investigator medical course.

Results

The first inductive analyses revealed four major themes relevant to the research question (1) “How do mentors view the processes in the development of self-regulation of learning that occur during the longitudinal relationship with their mentees.” The themes were: (1) the use and purpose of the portfolio in the mentoring process; (2) guiding the student to meaningful self-direction of learning, as opposed by the expectations of the assessment program; (3) different perceptions on the role as a mentor; (4) time needed for development of the mentors’ coaching skills and the outcome of the mentoring process.

Theme 1: The use and purpose of the portfolio in the mentoring process

The mentor made active use of the portfolio to prepare for the meetings, and set the agenda for the meeting, as the portfolio contained all feedback and results and depicted how the mentee used this information for self-direction of learning. The mentors indicated that the input of the mentee in the agenda setting was variable. Mentors either started from the dossier, going through the feedback and assessment information or started by reading the students’ self-reflections. Mentors wanted to establish first that the dossier information fitted with the analysis of the student. How the portfolio was used in the mentor meeting varied; either the portfolio served as input for the meeting but the actual content was not discussed (see quote below, int. 375), or the mentor and mentee go through the self-reflections more or less literally (see quote below, int. 373). In the latter case, the portfolio was dominant in the meeting, for example mentor and mentee would sit in front of the computer and discuss the actual content of the self-reflections.

I have to discuss (content of) the portfolio, that is what they need. Because it is assessed and it is their instrument. So I thought, this is what is minimally needed. They [students] have to leave knowing that it is OK. (int. 373)

The portfolio was more dominant in the meetings when it was a year 1 mentee, the mentor had less experience (discussed with Theme 4), and in case of evidence of poor performance (discussed with Theme 2). A dominance of the portfolio in the mentoring process was perceived as a pitfall, as it endangered the attention for the mentee as a “person,” for the personal development and research-interests of the mentee, and for topics such as work-life balance, that mentors perceived as important issues. Mentors were aware of this balance and indicated that the longitudinal relationship and personal learning of the mentor (Theme 4) helped to keep his balance.

I use the portfolio as a back-up in the meeting. It means I prepare beforehand, put my feedback in the self-reflections, but I will not go through all the feedback in the meeting. This is summarized in the minutes. But I do know what the important issues are and that is what I focus on in the meeting. At the end, I will shortly highlight certain issues in the portfolio, e.g. if the learning objectives are clear. But my primary focus is how they are doing, if there are important issues and discuss that. (int. 375)

Some mentors thought that portfolio and reflection was too elaborate and labor-intensive for the mentee and expressed that this yielded a delicate balance with the benefits in terms of coaching, getting “better doctors,” and stimulating self-regulation of learning through the portfolio.

It is really a lot of work next to what they already have to do. This is my most important critical note. It can be more condensed, more to the point. It is important in terms of the [national] Framework [for medical programs], the competencies have to be addressed, and I think this is really good. I think the competencies are a clear advantage as compared to how the curriculum used to be, and I’m totally in favor. But, the [content of the portfolio] can be more to the point. (int. 375)

Theme 2: To guide the student to meaningful self-direction of learning, as opposed to the expectations of the assessment program

When there was evidence of poor progress, for example in assessment results or reservations of the mentor about the level of reflection and self-directive potential of the mentee, the mentor became more directive, resulting in less input of the student. The mentor felt that it was needed to intervene to help the student, this, however, could lead to even less self-direction of the mentee. This also led to a very dominant role of the portfolio (relation to Theme 1), to the extent that the conversation was done in front of the computer screen, leaving little or no room for a face-to-face conversation or input of the student. For the mentors with less experience this was related to uncertainties about the end-level needed to pass the end of year portfolio assessment procedure.

Then I say: “You have to change a lot, here and there, and you have to include this and that in your self-reflection.” He writes down all my feedback, writes and writes and writes. And then he will change it. So that is how it will go. I do think that the ownership is really with the student. But I also want them to pass, so it is bit ambiguous off course. (int. 365)

But I really want them to do well, and be promoted to the next year. And I would blame myself for not mentioning things, that they could have used. So, this is related to my insecurity as a mentor, it is my first time. So I think, “maybe I am not indicating all kinds of important issues.” (int. 377)

Conversely, if the mentee showed good progress, a coaching style that stimulated self-direction of learning of the mentee, was favored by the mentor. Occasionally, a “good student” was perceived as difficult to coach, as there were no obvious problems. Most mentors were able to stimulate this mentee to take on new challenges or next steps in competency development. This became easier in time with the mentor developing his or her coaching skills (linked with Theme 4).

One of my students does really well, the self-reflections are very natural and authentic. As a mentor, I learned from this student. But a student like this, you can really challenge: “why is this going so smoothly, what are your tools? Have you considered to participate in a research project, explore possibilities to start your PhD?” You can stimulate or challenge every student on his or her own level. (int. 367)

All mentors had experience with a number of student-centered critical incidents (see ) that could either be meaningful starting points for reflection and self-direction by the mentee, or lead to more direction by the mentor, with the mentor solving the problem, instead of the mentee. Important determinants for the mentors response to the critical incident, that is becoming more directive or coaching the self-direction of the mentee, were the mentors’ perceived level of experience, which has relations with Theme 2, and the personal relationship with the student. As the mentor–mentee relationships were long term, mentors often felt very involved with their mentee, the perception of co-ownership of the problem then could lead to a more directive coaching style.

Table 2. Student-centered critical incidents.

In the ideal situation I want the student to address issues and come to an understanding, uhm. While, after reviewing the portfolio, I might feel the need to oppose to what they think [.], not that I want it to go in a certain direction. But I do want them to come to a certain awareness. And I think that I do give directions, instead of letting the student grasp the point. And then I’m more directive. (int. 368)

On the other hand, critical incidents were also meaningful starting points for self-directive learning of the mentee. The fact that the mentor had access to all feedback and reflective activities of the mentee through the portfolio, made it easy to discuss, highlight, and ask probing questions during the mentor meetings. All mentors experienced that their coaching supported or improved the depth of reflective activities by the mentee, leading to more control by the mentee.

I do think it is difficult, to be very transparent in the self-reflection, to reach the right level of depth in reflection to aid in the articulation of productive learning objectives. Learning objectives that really matter and are really needed, and not just because they have to have learning objectives in the portfolio. So in the mentor meeting, you help them to get to the nitty gritty, in a safe way, so that it is a SMART learning objective, and they recognize the moment that they can say: “I would like to have specific feedback,” and use it in their next portfolio. (int. 373)

Theme 3: Different perceptions on the role as a mentor

Mentors were the first contact for mentees for questions and advice. This included advice on personal issues or problems that may or may not influence the progress of a student in the program. All mentors felt that there was a boundary where the mentor role ended and other professionals such as study advisors, student dean or student psychologists need to take over. The timing of forwarding the student to another professional was perceived as difficult, factors were the personal relationship and uncertainties what is expected of the mentor in these issues.

I think it is also dangerous as a mentor to act as a psychologist: A, because I’m not a psychologist and B, I will be the mentor for four years. And you have a certain function in assessing or guarding the study progress. I think it is always better if there is an independent third person that takes care of psychological problems. You have to be able to draw the line, because if you get too involved, you are less able to function as a mentor later on, the student may be less open-minded toward you. I think if you get too involved, your role as a mentor may be disturbed or even impossible. (int. 367)

All mentors felt a conflict in the guiding and coaching of the mentee versus the assessor role. Although formally the mentors did not assess their mentee and the portfolio, the fact that the mentor gave feedback and had to give an indication of progress at the end of the year did lead to the impression of “having to assess.” What made it difficult was the personal relationship with the mentee, uncertainties about the end level and mentor experience.

And then you contemplate. I do not know the procedure well enough yet. So I also think: “what will happen if I say that it is not good enough, what will the other mentors say?.” How does it [assessment procedure] work? So these are the things I consider [for the mentor advice]. And you feel certain loyalty to the student, so yes it is a conflict. And maybe you then eventually choose for a marginal pass. (int. 374)

First I will find out what kind of problems they have and look at their portfolio. They will ask me, is it satisfactory? But, I always indicate, that in my opinion it could be a pass, but that does not mean other persons will think the same. I am the mentor, I coach, I’m not the assessor. So yes, I do hope it is a pass, I will do my best. We both contribute to the product. And someone else assesses. And that is quite difficult. Because they think that when I am satisfied, that it will be OK. (int. 376)

Another boundary was ownership of the portfolio, all mentors indicated that the portfolio and self-direction of learning was the responsibility of the mentee. This was especially evident around the student-centered critical incidents indicated at Theme 2, which lead to a tendency to be more directive as a mentor, which could put the control of the mentee on self-direction of learning at risk.

Theme 4: Time needed for development of the mentors’ coaching skills and the outcome of the mentoring process

All mentors indicated that the first year was the most difficult in terms of getting familiar with the curriculum, procedures, and the mentoring itself. Mentors perceived that they learned while doing and from the mentoring network. The fact that the mentoring itself and the contact with the mentee was longitudinal in the program supported the personal learning of the mentor. Valuable learning moments were the second mentor meetings (halfway through the year, when two mentors are present at the mentor meeting), the plenary mentor meeting at the end of the year and feedback of the mentees. The second mentor meeting was considered very informative as it gave opportunity to read portfolios of other students, see how a colleague uses mentoring skills, get feedback from a fellow-mentor after a meeting with a mentee and experience how the mentees are doing compared to the year group.

The second mentor meetings are very constructive. You go on a certain journey with your student. There are certain points to work on, points that I think are important or we both think are important. But, then you can have a blind spot for what may also be important. And then is it very helpful if the second mentor makes you aware. I really value that independent view. (int. 371)

I had a [second mentor] meeting in which the reflection was discussed very well. I thought: “oh yes, this is very useful, coming from someone who knows how to improve the depth of reflection. And that helps the student to develop further.” So that was very helpful. And this was also because there was this bit of a distance, to try and see the bigger picture in how a student deals with problems, or handles the study program. I really liked that and sometimes also how the meeting was arranged. Then you think: “This is also a good approach,” e.g. this mentor is not using the computer at all. (int. 374)

The plenary mentor meeting at the end of the year, in which all portfolios are discussed, also enabled first year mentors to experience how a group of mentors reached agreement on an indication of progress. This, together with the portfolio assessment of their own mentees, illustrated to the mentor how assessments, feedback, reflection, setting and follow-up of learning objectives, and the level of self-direction of learning were valued and weighted in the portfolio assessment. Mentors expressed that in the first year the “not knowing yet” what the end level should be, induced uncertainty. This was associated with a more directive coaching style, occasionally in combination with a very central role of the portfolio in the meetings, to reduce the possibility that the mentee would fail as a result of mentors’ inexperience. The whole set of experiences (second mentor, plenary mentor meeting, learning while doing) resulted in the development of mentoring and coaching skills, that were used in the next year. As the mentor–mentee relationship was long-term and continued the following years, this was valuable and beneficial for the coaching skills of the mentor and self-directing learning skills of the mentee.

I don’t want to give them a false sense of security, I struggle with that as a mentor. I felt this stronger when I just started. Now I have more experience, have attended more plenary meetings. You do take your own experience along. (int. 367)

In general, mentors perceived that the mentees also developed in time, learning how to use the information and feedback from the program in their portfolio and self-direct their learning and competency development. For new mentors, this process aligned with their learning and progression. In addition, regardless of mentor experience, the personal learning of both the mentee and mentor, in time led to an interaction in which the portfolio itself became less important in the meetings (related to Theme 1). There was more room for a dialog on personal topics, such as study or career choices.

In the beginning, it was really all about “what has to be included or not”? Is this a good quality learning objective or not? We really focused on the format. While now it is more about the content. I feel the person behind the student is much more addressed. And I think this is also attributable to the students themselves off course. But also as the result of my own learning process. (int. 368)

AT analysis

Using AT as a theoretical framework (research question 2), we distinguished both tensions and supporting activities in the four themes. As shown in , the two activity systems concerning the mentoring process were comparable, yet on the right the mentoring process was influenced by tensions while on the left, supporting activities or developments in time that became supportive, were prevalent. Thus, the use of the artifact portfolio could create a tension if the use was predominant over the actual mentoring conversation (as described in Theme 1). In the activity systems, it was clear that the interactions between the themes could create a tension in or offer support for the mentoring process. Relations between elements of the activity systems were present, for example the assessment procedures affected use of the artifact, the portfolio. In addition, in the interactions between themes, mentor-centered critical incidents were present, similar to the student-centered critical incidents, see . In the analysis, it was shown that these critical incidents influenced the mentoring role and the mentoring process, that is how issues were approached, how the portfolio was used, using a coaching or more directive approach (Theme 1, 2). Although mentors indicated that these incidents could be a struggle, the mentors’ personal learning and development were promoted by dealing with these incidents (Theme 4). In addition, the tension created by a student-centered critical incident had the potential for creating a learning process (Theme 2). Activities such as the mentor meetings during the year, the second mentor and plenary mentor meeting, and, in case of new mentors, the “buddy,” were helpful in the dealing with these critical mentor-centered critical incidents (Theme 3, 4).

Table 3. Mentor-centered critical incidents.

Discussion

In this study, we explored the mentors’ perception on the processes in the development of self-regulation of learning that occur during the longitudinal relationship with their mentees (research question 1). Four themes emerged, centered around the role of the portfolio, guiding of students’ self-direct(ed) learning (SDL) in the context of assessment procedures, mentor-role boundaries and longitudinal development of skills by both the mentor and mentee. The use of AT as a theoretical framework (research question 2) showed that in the interactions between the themes tensions or supportive factors could emerge for the activities of the mentoring process.

It has been suggested that portfolios are an effective instrument to guide and assist the learner in the process of self-directed learning (Buckley et al. Citation2009; Kicken et al. Citation2009; van Schaik et al. Citation2013). For effective use of a portfolio, a mentor is considered to be vital (Driessen et al. Citation2005). There are various studies on perception and use of a portfolio by students (Grant et al. Citation2007; Ross et al. Citation2009; Davis et al. Citation2009; Altahawi et al. Citation2012). Studies on the mentors’ perspective showed that mentors learned themselves and benefited in terms of improved interviewing skills, and job satisfaction (Connor et al. Citation2000; Allen & Eby Citation2003; Eby & Lockwood Citation2005; Overeem et al. Citation2010), as well as learning not to solve problems for the mentee, and dealing with tensions if the portfolio was assessed (Anderson & DeMeulle Citation1998; Overeem et al. Citation2010). However, it is less well known how the portfolio itself is used by the mentor. This study showed that use of the portfolio by mentors in the mentoring process varied and was influenced by a number of factors, such as mentor experience, self-confidence in the assessment procedures, and the proficiency of the mentee to reach sufficient depth of reflection. The portfolio was essential in the preparation for the mentor meeting, as it informed the mentor of points to improve or to discuss. A challenge was not to have the portfolio as the center of the meeting as this hindered the interaction with the mentee. This was clearly a learning process for mentors, as all mentors indicated that as a first year mentor, the portfolio tended to dominate the meeting, due to a perceived inexperience, and a tension that this was needed given the assessment of the portfolio. In time, the portfolio was still used as a valuable input, but the interaction with the mentee was deemed more important. The change in use of the portfolio in the mentoring process was associated with a development of mentoring skills in time. This “learning by doing” showed similarities with workplace-based learning, and as shown in other studies (Liu et al. Citation2009; Hudson Citation2013), the amount or duration of mentoring was associated with the development of mentoring skills, which in turn contributed to the personal development and mentors’ performance. A longitudinal interaction with the mentee (in this study 4 years) has clear benefits in terms the personal learning and professional development of the mentor.

The use of AT as a theoretical framework demonstrated two activity systems, where the object, the mentee, is supported in the self-direction of learning by the subject, the mentor. How the mentor approached this, that is using a coaching, more guiding approach or a directive, more steering approach was dependent on which elements of the activity systems prevailed. Crasborn et al. (Citation2011) described a model of mentor roles in mentoring dialogs, in which a profile can be made of a given mentor in terms of input (active–reactive in introducing topics) and directedness (using directive–non-directive skills). In this study, tensions often led to a more directive approach, instigated by either perceived inexperience of the mentor, the mentor feeling responsible for a sufficient assessment or a mentee with insufficient performance or depth of reflection, suggesting that mentor roles in mentor dialogs are adjustable given circumstances, mentor experience or judgment what is needed for a critical incident.

There is a certain paradox in that the development of self-directed and reflective learning actually requires direction by an educator (Knowles Citation1975; Pilling-Cormick Citation1997). Given that an important objective of mentoring is to give guidance and support and help the mentee to become more independent, there is a clear role for the mentor to guide the process of self-directed learning. This study showed that in most cases there was a developmental progress in both mentors’ and mentees’ skills and in the mentor–mentee relationship, leading to the mentee assuming more control of his or her learning. As suggested by Schunk and Mullen (Citation2013), self-regulation of learning is not be considered as an outcome of the mentoring process, but as an ongoing process. A longitudinal mentoring relationship can contribute to self-direction of learning by the mentee as a successful outcome of this process. This study also showed that a longitudinal mentoring system also resulted in connections between mentors, that is a mentor community was formed through mentor meetings, a buddy system, etc. (Theme 4). The context of this mentor community was also important for the development of mentoring skills. An important implication is that sufficient attention should be given to the first phase or the beginning of mentor position, as insecurity about regulations, artifacts (portfolio), and a tendency to be more directive influenced the self-directed learning of the mentee.

The findings of this study should be interpreted given certain limitations. First, only the perceptions of the mentors were sought. The perception of the mentees on how the mentoring process, use of portfolio by the mentor and longitudinal interaction with the mentor is affecting the process of self-direction of learning is important for the interpretation and potential implications for practice. Second, this study was performed in one institute, so the results may not be transferable to other settings.

In conclusion, the mentors’ perspective on the processes that occur in the development of self-regulated learning of their mentee showed that the positioning of the portfolio in the mentor meeting, the impact of assessment procedures, mentor-role boundaries and the effect of longitudinal development of skills by both the mentor and mentee were important factors in the coaching or steering activities by the mentor (Research Question 1). AT analysis showed that in the interactions between the themes tensions or supportive factors could emerge for the activities of the mentoring process (Research Question 2). More research is needed with respect to the use of a portfolio by the mentor and the impact of critical incidents in the mentoring process, to enable the development of dedicated faculty training programs.

Notes on contributors

Sylvia Heeneman, PhD, is Professor of Medical Education at the School of Health Profession Education, Department of Pathology, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, The Netherlands.

Willem De Grave, PhD, is a Senior Lecturer and Educational Psychologist in the Department of Educational Development and Research. Faculty of Health Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University.

Glossary

Portfolio-based learning or portfolios: A collection of evidence that learning has taken place, usually set within agreed objectives or a negotiated set of learning activities. Some portfolios are developed in order to demonstrate the progression of learning, while others are assessed against specific targets of achievement. In essence, portfolios contain material collected by the learner over a period of time. They are the learner’s practical and intellectual property and the learner takes responsibility for the portfolio’s creation and maintenance. Because the portfolio is based upon the real experience of the learner, it helps to demonstrate the connection between theory and practice, accommodating evidence of learning from different sources, and enabling assessment within a framework of clear criteria and learning objectives. The use of portfolios encourages autonomous and reflective learning which is an integral part of professional education and development. Candidates are expected to produce evidence and process such evidence with relation to a pre-determined standard. Since the portfolio approach includes both content and a reflective component, one must first determine which components are to be assessed. Portfolios provide a process for both formative and summative assessment, based on either personally derived or externally set learning objectives or a model for lifelong learning and continuing professional development.

Wojtczak A. 2003. Glossary of medical education terms. AMEE Occasional Paper No. 3. Dundee: AMEE.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Dr Juanita Vernooy, for helpful discussions at the start of the studies.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Allen T. 2007. Mentoring relationships from the perspective of the mentor. In: Ragins BR, Kram KE, editors. The handbook of mentoring at work: theory, research, and practice. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications Inc; p. 123–147.

- Allen T, Eby L. 2003. Relationship effectiveness for mentors: factors associated with learning and quality. J Manag. 29:469–486.

- Altahawi F, Sisk B, Poloskey S, Hicks C, Dannefer EF. 2012. Student perspectives on assessment: experience in a competency-based portfolio system. Med Teach. 34:221–225.

- Anderson R, Demeulle L. 1998. Portfolio use in twenty-four teacher education programs. Teach Educ Quart. 25:23–31.

- Arntfield S, Parlett B, Meston C, Apramian T, Lingard L. 2015. A model of engagement in reflective writing-based portfolios: interactions between points of vulnerability and acts of adaptability. Med Teach. 38:196–205.

- Battista A. 2015. Activity theory and analyzing learning in simulations. Simul Gaming. 46:187–196.

- Bray L, Nettleton P. 2007. Assessor or mentor? Role confusion in professional education. Nurs Educ Today. 27:848–855.

- Buckley S, Coleman J, Davison I, Khan KS, Zamora J, Malick S, Morley D, Pollard D, Ashcroft T, Popovic C. 2009. The educational effects of portfolios on undergraduate student learning: a Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) systematic review. BEME Guide No. 11. Med Teach. 31:282–298.

- Buddeberg-Fischer B, Herta K. 2006. Formal mentoring programmes for medical students and doctors: a review of the Medline literature. Med Teach. 28:248–257.

- Bunniss S, Kelly D, R. 2010. Research paradigms in medical education research. Med Educ. 44:358–366.

- Connor M, Bynoe A, Redfern N, Pokora J, Clarke J. 2000. Developing senior doctors as mentors: a form of continuing professional development. Report of an initiative to develop a network of senior doctors as mentors: 1994–99. Med Educ. 34:747–753.

- Crasborn F, Hennissen P, Brouwer N, Korthagen F, Bergen T. 2011. Exploring a two-dimensional model of mentor teacher roles in mentoring dialogues. Teach Teach Educ. 27:320–331.

- Davis M, Ponnamperuma G, Ker J. 2009. Student perceptions of a portfolio assessment process. Med Educ. 43:89–98.

- Driessen E, Van Tartwijk J, Overeem K, Vermunt J, Van Der Vleuten C. 2005. Conditions for successful reflective use of portfolios in undergraduate medical education. Med Educ. 39:1230–1235.

- Driessen E, Van Tartwijk J, Van Der Vleuten C, Wass V. 2007. Portfolios in medical education: why do they meet with mixed success? A systematic review. Med Educ. 41:1224–1233.

- Eby L, Brown BL, George K. 2014. Mentoring as a strategy for facilitating learning: protege and mentor perspectives. In: Billett S, Harteis C, Gruber H, editors. International handbook of research in professional and practice-based learning. Dordrecht: Springer; p. 1071–1097.

- Eby L, Lockwood A. 2005. Proteges and mentors reactions to participating in formal mentoring programs: a qualitative investigation. J Vocat Behav. 67:441–458.

- Engeström Y. 2001. Expansive learning at work: toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. J Educ Work. 14:133–156.

- Frank JR. 2005. The CanMEDS 2005 physician competency framework. Better Standards. Better Psysicians. Better Care. Ottawa: The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (report).

- Grant AJ, Vermunt JD, Kinnersley P, Houston H. 2007. Exploring students’ perceptions on the use of significant event analysis, as part of a portfolio assessment process in general practice, as a tool for learning how to use reflection in learning. BMC Med Educ. 7:5.

- Hudson P. 2013. Mentoring as professional development: 'growth for both' mentor and mentee. Prof Dev Educ. 39:771–783.

- Johnston J, Dornan T. 2015. Activity theory: mediating research in medical education. In: Cleland J, Durning SJ, editors. Researching medical education. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; p. 94–104.

- Jones R, Edwards C, Filho I. 2014. Activity theory, complexity and sports coaching: an epistemology for a discipline. Sport Educ Soc. 21:200–216.

- Kalén S, Ponzer S, Seeberger A, Kiessling A, Silén C. 2012. Continuous mentoring of medical students provides space for reflection and awareness of their own development. Int J Med Educ. 3:236–244.

- Kicken W, Brand-Gruwel S, Van Merriënboer J, Slot W. 2009. Design and evaluation of a development portfolio: how to improve students’ self-directed learning skills. Instruct Sci. 37:453–473.

- King N. 2004. Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In: Cassel C, Symon G, editors. Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research. London: Sage; p. 256–270.

- Knowles M. 1975. A guide for learners and teachers. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall/Cambridge.

- Liu D, Liu J, Kwan Mao Y. 2009. What can I gain as a mentor? The effect of mentoring on the job performance and social status of mentors in China. J Occup Organ Psychol. 82:871–895.

- Malterud K. 2001. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 358:483–488.

- Mann K, Gordon J, Macleod A. 2009. Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ. 14:595–621.

- O’shea E. 2003. Self-directed learning in nurse education: a review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 43:62–70.

- Overeem K, Driessen E, Arah O, Lombarts K, Wollersheim H, Grol R. 2010. Peer mentoring in doctor performance assessment: strategies, obstacles and benefits. Med Educ. 44:140–147.

- Overeem K, Wollersheim H, Driessen E, Lombarts K, Van De Ven G, Grol R, Arah O. 2009. Doctors' perceptions of why 360-degree feedback does (not) work: a qualitative study. Med Educ. 43:874–882.

- Pilling-Cormick J. 1997. Transformative and self-directed learning in practice. New Dir Adult Contin Educ. 1997:69–77.

- Ross S, Maclachlan A, Cleland J. 2009. Students' attitudes towards the introduction of a Personal and Professional Development portfolio: potential barriers and facilitators. BMC Med Educ. 9:69.

- Sambunjak D, Straus S, Marusic A. 2006. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. Jama. 296:1103–1115.

- Sambunjak D, Straus S, Marusic A. 2010. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 25:72–78.

- Sandars J. 2009. The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 44. Med Teach. 31:685–695.

- Sargeant J, Lockyer J, Mann K, Holmboe E, Silver I, Armson H, Driessen E, Macleod T, Yen W, Ross K. 2015. Facilitated reflective performance feedback: developing an evidence- and theory-based model that builds relationship, explores reactions and content, and coaches for performance change (R2C2). Acad Med. 90:1698–1706.

- Schunk D, Mullen C. 2013. Toward a conceptual model of mentoring research: integration with self-regulated learning. Educ Psychol Rev. 25:361–389.

- Van Der Vleuten C, Dannefer E. 2012. Towards a systems approach to assessment. Med Teach. 34:185–186.

- Van Der Vleuten C, Schuwirth L, Driessen E, Dijkstra J, Tigelaar D, Baartman L, Van Tartwijk J. 2012. A model for programmatic assessment fit for purpose. Med Teach. 34:205–214.

- Van Herwaarden C, Laan R, Leunissen R. 2009. The 2009 framework for undergraduate medical education in the Netherlands [Internet]. [cited 2016 Apr 1]. Available from: http://www.vsnu.nl/Media-item/Raamplan-Artsopleiding-2009.htm

- Van Schaik S, Plant J, O'sullivan P. 2013. Promoting self-directed learning through portfolios in undergraduate medical education: the mentors' perspective. Med Teach. 35:139–144.