Abstract

In medical education, students are increasingly regarded as active seekers of feedback rather than passive recipients. Previous research showed that in the intentions of students to seek feedback, a learning and performance goal can be distinguished. In this study, we investigated the intentions (defined as level and orientation of motivation) of different performing students (low, average, and high performing students) to seek feedback in the clinical workplace using Self-Determination Theory. We conducted a quantitative study with students in their clinical clerkships and grouped them based on their performance. The level of motivation was measured by the number of Mini-CEXs each student collected. The orientation of motivation was measured by conducting the Academic Self-Regulation Questionnaire. We found that high performing students were more motivated and demonstrated higher self-determination compared to low performing students.

Introduction

In the last decade, the field of medical educational research has increasingly been focusing on students as active seekers of feedback rather than passive recipients (Janssen & Prins Citation2007; Teunissen et al. Citation2009; Bok et al. Citation2013a; Teunissen & Bok Citation2013). Research from Bok et al. has found that personal (like the intentions and characteristics of the feedback seeker) and interpersonal factors are involved in the feedback-seeking behavior of students. In the intention to seek feedback, students can have two distinctive goals: a learning or performance goal (Bok et al. Citation2013a), which is a result of different underlying motives or reasons: instrumental, ego-based, or image-based motives (Ashford & Cummings Citation1983; Bok et al. Citation2013a). The theoretical model elaborating the process of feedback-seeking is the Goal Orientation Model as initially proposed in organizational psychology (VandeWalle Citation2004). However, we believed that Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan Citation1985) as a theoretical framework to explain the underlying reasons in the task of feedback-seeking might provide a new perspective in investigating the intentions of students to seek feedback in the clinical workplace. To our knowledge, no study in the field of medical education has investigated the motivation of students to seek feedback in the clinical workplace using Self-Determination Theory. Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan Citation1985; Ryan & Deci Citation2000a, Citation2000b) elaborates the reason why a person is moved to perform a task, defined as motivation. In this, motivation is regarded as a continuum toward self-determination. When one shows self-determined behavior, he/she is intrinsically motivated, whereas an externally regulated person shows little self-determination. Between intrinsic motivation and external regulation, three additional stages can be distinguished: integrated regulation, identified regulation, and introjected regulation. Additionally, a person can lack any intention to act and is unwilling to perform a task: this person shows no self-determination and is thus amotivated. This study aims to determine whether different (low, average, and high) performing students differ in the level and orientation of motivation to seek feedback in the clinical workplace.

Methods

This study was conducted among students in their final years of the Veterinary Medicine program at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands. Learning in the final years is mainly organized around clinical rotations, consisting of a Uniform (years 1 and 2) and a Track (year 3) period. The Uniform period is comprised of general clinical clerkships for all animal species (Companion Animal Health, Equine Sciences, and Farm Animal Health) and a specific clinical clerkship for the species of choice (rotation type). During these clerkships, students seek feedback on their performance by collecting feedback forms (e.g. Mini-CEXs) organized in a portfolio. Each collected feedback form is regarded as a formative data point, containing both quantitative and qualitative information about the student. A minimum number for each form, differing per rotation type, is required according to exam regulations. Students are held responsible for collecting sufficient feedback forms. In most cases, students actively ask for feedback forms. At the end of the Uniform period, a final summative assessment takes place on a 10-point scale, the assessment committee regards a student who is graded 7 as “average performing”. The assessment of the student is organized around the theoretical framework of longitudinal programmatic assessment (van der Vleuten et al. Citation2012).

Participants

Participants were selected following two criteria. First, the participants had received the non-remediated final summative grade of the Uniform period. Second, the participants were still occupied in the Veterinary Medicine program. This made it possible to examine the portfolio. Next to that, the time between the end of the Uniform period and the questionnaire had to be reasonable for recall reasons. This resulted in a maximum number of 87 participants, with varying differentiation. After this, the participants were divided into three groups based on their performance. The measure for performance was the non-remediated final grade the participant received on the summative assessment of the Uniform period. Low performing students were defined as students who were graded lower than 7, average performing students equal to 7 and high performing students higher than 7.

Procedure

As a measure for the level of motivation, the frequency of feedback-seeking was used. We believed that the more a student asks for feedback forms, the higher the level of motivation is to seek feedback. To measure the frequency of feedback-seeking, the number of Mini-CEXs a participant collected was used. We specifically selected the Mini-CEX forms, since we believed in most cases students actively asked for Mini-CEXs. For each participant (n = 87), the number of Mini-CEXs received from both supervisors and peers was counted and corrected for the minimum requirements per rotation type as recorded in the exam regulations. For example, a student who had to collect a minimum of 14 Mini-CEXs and collected 20 Mini-CEXs in total, was noted to have collected 6 Mini-CEXs. When a student failed to meet the minimum requirements, the collected number of Mini-CEXs was presented as a negative value. Subsequently, to evaluate the orientation of motivation a questionnaire was sent out by email to all participants (n = 87). The questionnaire was based on a Dutch version of the Academic Self-Regulation Questionnaire (previously used in Niemiec et al. Citation2006; Vansteenkiste et al. Citation2009; Soenens Citation2012; Vansteenkiste et al. Citation2012). We modified the Academic Self-Regulation Questionnaire for the purpose of this study: changed the present tenses into past tenses, replaced the words “parents, friends, teachers….” by “supervisors, tutors and peers” and added a few contextual words to enhance understanding of the statements. However, the scale “amotivation” had to be modified more rigorously for the purpose of this study (items/rating scale): only the core message of each statement remained similar. In the Appendix, the questionnaire used in this study has been added as a Supplementary file (translated into English). Participants were asked to answer 20 statements on a 5-point Likert scale regarding their motivation to collect feedback. These 20 statements were grouped into three scales (controlled motivation, autonomous motivation, and amotivation) and four subscales (there is no scale for measuring integrated regulation) according to Self-Determination Theory and analyzed on reliability using Cronbach’s α: “autonomous motivation” (scale; α = 0.88) was assessed by “intrinsic motivation” (subscale; α = 0.84) and “identified regulation” (subscale; α = 0.69), whereas “controlled motivation” (scale; α = 0.71) was assessed by “introjected regulation” (subscale; α = 0.78) and “external regulation” (subscale; α = 0.71); “amotivation” (scale; α = 0.78) was not subdivided into subscales.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using R, version 3.3.1 (2016-06-21) (R Core Team Citation2016). First, in both datasets (level and orientation of motivation), descriptive values were determined per performance group (low, average, and high performing students): e.g. mean, median. Additionally, for the level of motivation, boxplots were generated and for the orientation of motivation the response percentage was determined and checked whether the respondents were representative for the selected group of participants. To validate the assumptions of the parametric statistical test, normality and homogeneity of variance was tested. A non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test was applied to compare the groups, combined with a post-hoc Dunn’s test, since the presence of ties (package ‘PMCMR’, version 4.1). A correction for multiple testing was performed according to the Holm correction.

Ethical considerations

The Ethical Review Board of the Dutch Association for Medical Education (NVMO-ERB) approved this study (number: 618). The analyzed respondents of the questionnaire were informed and gave informed consent. The informed consent explicitly stated that participation was voluntary and confidentiality fully assured. The results of the questionnaire were exclusively used for this study and had no consequences for the study progress of the students.

Results

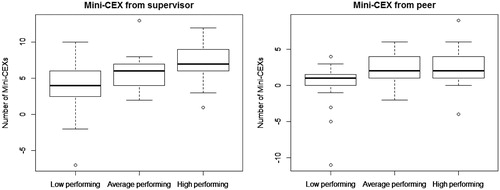

The median number of collected Mini-CEX forms for the selected students (n = 87) gradually increased from low performing, to average performing, and high performing students (). The number of collected Mini-CEXs significantly differed between low performing, average performing, and high performing students in both Mini-CEXs from supervisor (H(2) = 19.134; p < 0.01) and Mini-CEXs from peer (H(2) = 17.099; p < 0.01). High performing students collected significantly more Mini-CEXs than low performing students from both supervisors (p < 0.01) and peers (p < 0.01), while no difference was found between high performing and average performing students (Mini-CEXs from supervisor: p = 0.10; Mini-CEXs from peer: p = 0.32). Furthermore, average performing students collected significantly more Mini-CEXs from peers (p = 0.03) than low performing students, but no difference was found concerning Mini-CEXs from supervisors (p = 0.10).

Figure 1. Boxplot number of Mini-CEXs from supervisor and peer comparing low, average, and high performing students. The y-axis reflects the number of Mini-CEXs collected compared to the minimum requirements as recorded in the exam regulations. Regarding Mini-CEXs from supervisor, the median value in low, average, and high performing students is 4, 6, and 7, respectively. For example, a median value of four represents students collecting four more Mini-CEXs than minimally required. Regarding Mini-CEXs from peer, the median value in low, average, and high performing students is 1, 2, and 2, respectively.

Out of 87 selected students, 47 responded to the questionnaire to assess the orientation of motivation to seek feedback in the clinical workplace. However, four students disagreed to the informed consent and three students dropped out during the questionnaire. Therefore, 40 questionnaires were used for analysis (response rate: 46%). Regarding the performance, the analyzed respondents (n = 40) of the questionnaire were considered to be a representative selection for the selected group of participants (n = 87): 37.5% of the low performing students responded to the questionnaire, these students represented 46.0% in the group of selected participants. In the group average performing students, this was 22.5% respondents versus 20.7% selected participants and in the group high performing students, this was 40% respondents versus 33.3% selected participants. The mean of the orientation of motivation on a 5-point Likert scale gradually shifted between groups, except for the subscale introjected regulation (). The mean of the (sub)scales “autonomous motivation”, “intrinsic motivation”, and “identified regulation” increased in high performing students, whereas the mean of the (sub)scales “controlled motivation”, “external regulation”, and “amotivation” decreased in high performing students. The mean of average performing students was mostly situated between low performing and high performing students. High performing students scored highest on identified regulation, whereas low performing students scored highest on external regulation.

Table 1. Mean and SD values of the orientation of motivation compared between low, average, and high performing students on a 1- to 5-point Likert scale.

Statistical analysis showed that the orientation of motivation differs between low performing, average performing, and high performing students concerning the scale autonomous motivation (H(2) = 11.78; p < 0.01) and the subscales intrinsic motivation (H(2) = 10.034; p < 0.01), identified regulation (H(2) = 11.401; p < 0.01), and external regulation (H(2) = 8.1151; p = 0.02). No difference was found concerning the scale controlled regulation and amotivation and the subscale introjected regulation. As summarized in , there was no difference in the orientation of motivation in seeking feedback between low performing students and average performing students (autonomous motivation: p = 0.74; intrinsic motivation: p = 0.86; identified regulation: p = 0.57; external regulation: p = 0.54). However, high performing students were more autonomously motivated (p < 0.01), intrinsically motivated (p = 0.01), and regulated through identification (p < 0.01) than low performing students, whereas low performing students were more externally regulated than high performing students (p = 0.02). Average performing students were significantly less autonomously motivated (p = 0.03), and intrinsically motivated (p = 0.04) than high performing students, however no difference was found regarding external regulation (p = 0.16) and identified regulation (p = 0.05).

Table 2. p Values post-hoc Dunn’s test with Holm correction. The (sub)scales autonomous motivation, intrinsic motivation, identified regulation, and external regulation were compared between low, average, and high performing students.

Discussion

This study aimed to gain insight into the level and orientation of motivation in students to seek feedback in the clinical workplace, through the collection of feedback forms in a portfolio. We used Self-Determination Theory to explore the underlying reasons to seek feedback, whereas Goal Orientation Model is commonly used as a theoretical framework for feedback-seeking behavior (VandeWalle Citation2004). We believed that Self-Determination Theory to explain the underlying reasons to seek feedback might provide additional insights from a different perspective. Vansteenkiste et al. had similar thoughts about a comparable matter by proposing to use Self-Determination Theory as explaining the underlying factors in Achievement Goal Theory (Vansteenkiste et al. Citation2014). The results of the current study show that high performing students scored highest on identified regulation, whereas low performing scored highest on external regulation in seeking feedback. Furthermore, high performing students were more motivated and higher autonomously motivated, intrinsically motivated, and regulated through identification compared to low performing students, whereas low performing students were less motivated and higher externally regulated. In relation to Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci Citation2000b), high performing students in comparison with low performing students experience higher intrinsic motivation – because the task itself gives them satisfaction and higher identified regulation – the outcome of the task is accepted as personally important. Thus, high performing students are higher self-determined compared to low performing students. High self-determination leads to greater persistence, more positive self-perceptions, and better quality of engagements (Ryan & Deci Citation2000a). In contrast, low performing students in comparison with high performing students experience higher external regulation – they seek feedback because it meets external demands, leads to rewards (Ryan & Deci Citation2000b). A higher level of motivation and self-determination seems to characterize high performing students, but why? A possible explanation is that high performing students experience higher benefits in seeking feedback than low performing students. Since high performing students scored highest on identified regulation, this suggests that the main reason for high performing students to seek feedback is to learn from it (learning goal). Which results in them collecting more feedback. These findings are in line with previous research using Goal Orientation Model which has found that the likelihood to seek feedback in individuals with a learning goal is higher (VandeWalle Citation1997; Teunissen et al. Citation2009) and experience higher benefits (VandeWalle Citation2004). In contrast, low performing students scored highest on external regulation and thus seem to seek feedback primarily because they are required to, resulting in collecting less feedback. This suggests that the main reason for these students to collect feedback is to meet the requirements of the exam regulations and/or receiving their certificate. In the context of the applied theoretical model of longitudinal programmatic assessment at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, every individual assessment is low stakes/formative. However, earlier research showed that in the practical implementation of this theoretical framework, students do not seem to perceive individual assessments as formative, but rather as summative (Bok et al. Citation2013b). The findings in this study might suggest that some students – the high performing ones – do see the beneficial effects of feedback in developing themselves and are more likely to use the feedback in a rather formative way. However, more research is necessary to investigate this matter.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study which combined the level and orientation of motivation using Self-Determination Theory in evaluating the motivation of feedback-seeking in students with different performance in the clinical workplace. However, four limitations need to be addressed. First, due to practical reasons the number of participants was relatively small (n = 87 for measuring the level of motivation and n = 40 for measuring the orientation of motivation). Second, some students were graded 5, because they collected insufficient forms in their portfolio. This might result in finding higher differences between groups. Third, the final grade might be influenced positively by the excess above requirements of Mini-CEXs. Finally, even though based on grades, the respondents of the questionnaire appeared to be representative for the research group, the possibility exists that very high motivated high performing students and very low motivated low performing students responded to the questionnaire. This might affect the accuracy of the results.

Further research

This study found that high performing students seem to be more motivated and higher self-determined compared to low performing students to seek feedback. Therefore, it might be interesting to focus in further studies on evaluating these students. Why does it work for them? What characterizes these students? Why do they seek more feedback than required? By conducting semi-structured interviews with high performing students, the results might provide further insights into the practical implementation of the theory of programmatic assessment: what makes a low stake assessment low stake and when and why do learners engage with the feedback. Second, motivation toward performing tasks can change over time, this depends on previous experiences and situational factors (Ryan & Deci Citation2000b). Does motivation to seek feedback changes during the clinical clerkships? And how can we relate this to the factors found in previous research?

Practical implications

In this study, we found that high self-determination and relative more motivation possibly leads to processing of feedback for the purpose of learning. Therefore, awareness of students regarding their motivation to seek feedback might enhance self-regulated learning. Or in other words, as stated by Crommelink et al. to design a training program to develop individuals toward a learning goal (Crommelinck & Anseel Citation2013). This is important since we expect students to autonomously regulate their own learning process in the clinical workplace. We think that with use of the applied questionnaire, students are able to evaluate themselves and reflect on their motivation to seek feedback. Regular evaluation with a tutor might trigger the student to develop themselves toward self-determination. By altering this behavior, students might enhance their performance.

Glossary

Feedback-seeking behavior: Processes involved in inviting feedback.

Bok HG, Teunissen PW, Spruijt A, Fokkema JP, van Beukelen P, Jaarsma DA, van der Vleuten, Cees PM. 2013a. Clarifying students’ feedback‐seeking behavior in clinical clerkships. Med Educ. 47:282–291.

Ashford SJ, Cummings LL. 1983. Feedback as an individual resource: Personal strategies of creating information. Organ Behav Hum Perform. 32:370–398.

Davis W, Fedor DB. 1998. The role of self-esteem and self-efficacy in detecting responses to feedback. Fort Belvoir, VA: US Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences; p. 1–44.

Notes on contributors

L. H. de Jong, MSc, DVM, is a PhD candidate at the Chair Quality Improvement in Veterinary Education, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

R. P. Favier, PhD, DVM, is an assistant professor at the Department of Clinical Sciences of Companion Animals, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

C. P. M. van der Vleuten, PhD, is a professor of Education, Chair of the Department of Educational Development and Research and director of the School of Health Professions Education, Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands.

H. G. J. Bok, PhD, DVM, is an assistant professor at the Chair Quality Improvement in Veterinary Education, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Supplemental_content.docx

Download MS Word (17.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Anne-Marije Rijkaart MSc for support in the selection of the participants, Dr. Hans Vernooij for statistical advice, and Prof. Dr. Maarten Vansteenkiste for providing the Dutch version of the Academic Self-Regulation Questionnaire and advice on a previous version of the questionnaire.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Ashford SJ, Cummings LL. 1983. Feedback as an individual resource: personal strategies of creating information. Organ Behav Hum Perform. 32:370–398.

- Bok HG, Teunissen PW, Favier RP, Rietbroek NJ, Theyse LF, Brommer H, Haarhuis JC, van Beukelen P, van der Vleuten CP, Jaarsma DA. 2013b. Programmatic assessment of competency-based workplace learning: when theory meets practice. BMC Med Educ. 13:123.

- Bok HG, Teunissen PW, Spruijt A, Fokkema JP, van Beukelen P, Jaarsma DA, van der Vleuten, Cees PM. 2013a. Clarifying students’ feedback-seeking behaviour in clinical clerkships. Med Educ. 47:282–291.

- Crommelinck M, Anseel F. 2013. Understanding and encouraging feedback-seeking behaviour: a literature review. Med Educ. 47:232–241.

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. 1985. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum Press.

- Janssen O, Prins J. 2007. Goal orientations and the seeking of different types of feedback information. J Occup Organ Psychol. 80:235–249.

- Niemiec CP, Lynch MF, Vansteenkiste M, Bernstein J, Deci EL, Ryan RM. 2006. The antecedents and consequences of autonomous self-regulation for college: a self-determination theory perspective on socialization. J Adolesc. 29:761–775.

- R Core Team. 2016. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Core Team.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. 2000a. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 25:54–67.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. 2000b. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 55:68.

- Soenens B. 2012. Psychologically controlling teaching: examining outcomes, antecedents, and mediators. J Educ Psychol. 104:108–120.

- Teunissen PW, Bok HG. 2013. Believing is seeing: how people’s beliefs influence goals, emotions and behaviour. Med Educ. 47:1064–1072.

- Teunissen PW, Stapel DA, van der Vleuten C, Scherpbier A, Boor K, Scheele F. 2009. Who wants feedback? An investigation of the variables influencing residents’ feedback-seeking behavior in relation to night shifts. Acad Med. 84:910–917.

- van der Vleuten C, Schuwirth L, Driessen E, Dijkstra J, Tigelaar D, Baartman L, van Tartwijk J. 2012. A model for programmatic assessment fit for purpose. Med Teach. 34:205–214.

- VandeWalle D. 1997. A test of the influence of goal orientation on the feedback-seeking process. J Appl Psychol. 82:390.

- VandeWalle D. 2004. A goal orientation model of feedback-seeking behavior. Human Resour Manage Rev. 13:581–604.

- Vansteenkiste M, Lens W, Elliot AJ, Soenens B, Mouratidis A. 2014. Moving the achievement goal approach one step forward: toward a systematic examination of the autonomous and controlled reasons underlying achievement goals. Education Psychol. 49:153–174.

- Vansteenkiste M, Sierens E, Goossens L, Soenens B, Dochy F, Mouratidis A, Aelterman N, Haerens L, Beyers W. 2012. Identifying configurations of perceived teacher autonomy support and structure: associations with self-regulated learning, motivation and problem behavior. Learn Instruct. 22:431–439.

- Vansteenkiste M, Sierens E, Soenens B, Luyckx K, Lens W. 2009. Motivational profiles from a self-determination perspective: the quality of motivation matters. J Educ Psychol. 101:671.