Abstract

Background: There have been calls to enhance clinical education by strengthening supported active participation (SAP) of medical students in patient care. This study examines perceived quality of care when final-year medical students are integrated in hospital ward teams with an autonomous relationship toward their patients.

Methods: We established three clinical education wards (CEWs) where final-year medical students were acting as “physician under supervision”. A questionnaire-based mixed-method study of discharged patients was completed in 2009–15 using the Picker Inpatient Questionnaire complemented by specific questions on the impact of SAP. Results were compared with matched pairs of the same clinical specialty from the same hospital (CG1) and from nationwide hospitals (CG2). Patients free-text feedback about their hospital stay was qualitatively evaluated.

Results: Of 1136 patients surveyed, 528 (46.2%) returned the questionnaire. The CEWs were highly recommended, with good overall quality of care and patient-physician/student-interaction, all being significantly (p < 0.001) higher for the CEW group while experienced medical treatment success was similar. Patient-centeredness of students was appreciated by patients as a support to a deeper understanding of their condition and treatment.

Conclusion: Our study indicates that SAP of final-year medical students is appreciated by patients with high overall quality of care and patient-centeredness.

Introduction

Clinical rotations belong to the core of medical education and are usually a significant part of undergraduate education. They allow students to encounter patients directly and to learn at the future workplace. Seen through the lens of participation in the “Community of Practice” (Lave and Wenger Citation1991; Wenger Citation1999), supported active participation (SAP) in patient care is of great value to medical students, promoting the achievement of implicit knowledge, practical competences, professional attitudes, empathy, and a sense of professional identity (Spencer et al. Citation2000; Smith et al. Citation2013; Dornan et al. Citation2014). However, while the usefulness of clinical rotations is not questioned, several studies have raised doubts as to whether SAP is realized sufficiently in contemporary medical education. Clinical clerkships in different European countries were found to provide passive experiences, insufficient supervision and poor team integration (Remmen et al. Citation2000; Daelmans et al. Citation2004; Schrauth et al. Citation2009; Bugaj et al. Citation2017). A study in the UK revealed that graduates especially felt deficits in areas based on experiential learning in clinical practice (Illing et al. Citation2013); similar self-assessed deficits, e.g. in treatment and therapy planning, were found in Germany in a high percentage of graduates (Ochsmann et al. Citation2011). Thus, there has been a call to explore how clinical rotations can be enhanced and to strengthen active student participation in patient care (Bleakley and Bligh Citation2008; Illing et al. Citation2013; Bugaj et al. Citation2017).

A recent study on clerkship learning contrasts the traditional form of clinical teaching with a focus of transmission of competences from the teacher to the learner with a modern form of learning by participation (Steven et al. Citation2014). The authors suggest a far-reaching change in the way students are integrated into clinical health care teams:

“Clerkship learning, we suggest, could be enhanced by clinical communities allowing themselves to be changed by learners, just as learners are changed by communities. For that to be possible, the prevailing imbalance of power between teachers and learners must shift in learners favor. Then it may be possible for the culture of clinical workplaces to move from teaching to learning and from knowledge-centeredness to authentic patient-centeredness.”(p.475)

SAP in this sense means that students not only participate in learning and teaching but also contribute to patient care. In contrast to being passively taught what experienced clinicians do with their patients, they are supported in actively finding solutions for their patients, and their related health care problems. To allow such intensive SAP, exploring how patient care is affected and how SAP is realized without a significant negative impairment of delivered health care is essential.

During the last decades, different steps have been initiated to promote SAP, mostly in outpatient or community settings, as in students participation in general practice consultations (Bentham et al. Citation1999), student-run clinics (Schutte et al. Citation2015), or in longitudinal clerkships (Gaufberg et al. Citation2014). SAP in hospital wards remains a major challenge (Bleakley and Bligh Citation2008) since the setting is more complex and therefore more difficult to adapt to educational needs. Clinical education wards (CEWs) are one way of promoting SAP in hospital settings. In Sweden (Wahlström et al. Citation1997; Lindblom et al. Citation2007), Great Britain (Reeves et al. Citation2002), and Germany (Scheffer et al. Citation2010), they have been developed to combine inpatient care with clinical education. Educational research has shown that CEWs are of great value to the learners, allowing them to gain practical competencies in patient care and to benefit from professional role development, collaborative education, and interprofessional learning (Reeves et al. Citation2002; Ponzer et al. Citation2004; Hylin et al. Citation2007).

However, while SAP has been evaluated from the learning perspective, there is uncertainty about how it impacts on the quality of patient care. Integrating novices as team members and letting them learn by caring for patients may not be accepted by patients and could impair the quality of care. Research on the impact of student involvement on patient care has focused mainly on students participation in general practice consultations (Bentham et al. Citation1999; Prislin et al. Citation2001; Salisbury et al. Citation2004; Choudhury et al. Citation2006) or in other outpatient settings (Cooke et al. Citation1996; Thistlethwaite and Cockayne Citation2004). However, the situation for patients in hospital wards is different, with a higher vulnerability and a more urgent need for treatment (Benson et al. Citation2005).

Clinical education should not only focus on the development of practical competences and implicit knowledge but also on patient-centeredness and empathy. While, from the original aim, clinical education and encounters with patients should enhance students abilities (Spencer et al. Citation2000), studies show that empathy and patient centeredness often decline during medical education (Neumann et al. Citation2011), especially during the clinical years (Hojat et al. Citation2009; Bombeke et al. Citation2010). Thus, the conditions that foster patient-centeredness in clinical education are of major interest and it has been argued that not only attitude but also behavior should be examined (Bleakley and Bligh Citation2008).

With the presented CEWs, we aimed to foster the SAP of final-year medical students in various hospital settings, allowing them to act as physicians under supervision with autonomous relationships to their patients and with integration as full members of the local health care teams.

The goal of the following study was to examine whether SAP as realized with the presented CEWs has an impact on the quality of patient care. In particular, we wanted to know how patients perceived the delivered care regarding the following aspects:

Overall quality of care and recommendation.

Treatment success and complications.

Patient-physician/student-interaction.

In addition, we were also interested in how patients experience the impact of SAP on the quality of their care.

Method

Final year rotations at Witten Herdecke University (WHU)

The final year of undergraduate medical education in Germany consists of three clinical rotations of 16 weeks including one hospital-based rotation in internal medicine. They play a key role in preparing students for their work as physicians by providing opportunities to participate in patient care as an integrated team member in an authentic learning environment (Nikendei et al. Citation2012). The final year can be done at university hospitals or at academic teaching hospitals in Germany or abroad. While the main aim of these rotations is to enable students to experience predominantly independent patient management under close clinical supervision (Schrauth et al. Citation2009; Nikendei et al. Citation2012), the students often report being in a passive role, limited to routine work that is of little educational value with insufficient independent patient management, feedback, or supervision (Schrauth et al. Citation2009; Bugaj et al. Citation2017).

The CEWs in this research were established during a project of the Integrated Curriculum for Anthroposophic Medicine of the WHU (Scheffer et al. Citation2012), in cooperation with the respective hospital departments of the Gemeinschaftskrankenhaus Herdecke, Germany. This is an acute hospital providing Level II care and practicing integrative medicine by complementing conventional medicine with Anthroposophic Medicine (Heusser et al. Citation2012). It is part of the teaching hospitals of WHU (Schlett et al. Citation2010), which focuses on problem-based learning, practice-based education, and student engagement.

Educational setting

To enhance SAP of final year medical students, a CEW concept was developed and tested in 2007/8. Students were the primary “physician” for 2–4 patients, mastering as autonomously as possible all tasks during admission, planning of diagnosis, and therapy including the discharge summary. Depending on the level of difficulty and importance of the task, a staged supervision took place, comprising daily joint patient visits and continuous telephone availability of the supervising physician. Important diagnostic and therapeutic steps were suggested by students but required the agreement and the signature of supervising physicians, who remain responsible for the quality of care provided. On admission, patients were informed of the student participation.

After having been asked for important learning goals and their realization on the ward, students and clinicians were involved in developing the CEW. Subsequently, the students were engaged in regular focus group interviews with the aim of improving and adapting the CEW to students learning needs. In the medical department, where the first CEW was established, 4–5 students work simultaneously during their final year rotation, usually 12–16 weeks (up to four weeks may be completed at other wards of the hospitals department for internal medicine). Students are guided and supervised by an experienced resident and a senior physician. In addition, a clinical reflection training was developed on request of the first participating students. This regular training every two weeks under the guidance of a psychosomatic specialist allows intra- and interpersonal challenges arising from clinical practice to be reflected and appropriate individual solutions to be jointly developed (Lutz et al. Citation2013, Citation2016).

The original CEWs in Sweden (Wahlström et al. Citation1997; Lindblom et al. Citation2007) and the UK (Reeves et al. Citation2002) emphasized interprofessional learning with students of different health professions, including medical students before their final year, participating for two weeks at an orthopedic ward. In contrast, our final year CEWs at WHU focus primarily on SAP with a longer rotation period of 12–16 weeks and a wide range of patients including non-elective patients in acute emergencies. Despite these differences we use the term “CEW” since both concepts combine hospital based clinical care with education and active participation of health care students. So far, the presented final-year CEWs at WHU are offered only to medical students. However, interprofessional learning and teamwork represent important learning goals for participating students. Thus every rotation starts with a structured interprofessional introductory week and students not only participate in team meetings and also in weekly interprofessional patient conferences.

In 2011, two further CEWs were established in pediatrics and neurology. In both departments, a similar concept was implemented, with only 2–3 students in each four-month rotation, directly supervised by a senior physician.

Research methodology

The intended research focus was to explore perceived quality of care in a hospital setting with SAP compared to conventional wards and to analyze patients perceptions on the specific impact of SAP. For this, a design-based-research approach (Collective TD-BR Citation2003) with quantitative and qualitative methods was used.

Patient survey

Within 6–8 weeks after hospital discharge, an independent survey institute (the Picker Institute Germany) sent all patients or, in pediatrics, the patients parents of the three CEWs an anonymous questionnaire on their experience with the quality of care on the CEWs. The international widely used and validated Picker Inpatient Questionnaire (PIQ) (Jenkinson et al. Citation2002) primarily contains event-oriented questions (“How often did it happen, that…”), which, in contrast to mere judgmental questions (“How do you assess (rate/evaluate?),…”), give better insights into objectively existent problems (Bruster et al. Citation1994) The questionnaire was supplemented by eight questions concerning the participation of students in patient care (Scheffer et al. Citation2010).

The results of the PIQ were compared with those from two control groups (CGs) using a matched-pairs analysis. Aligned by age group, gender, education level, disease severity, and pain level, each CEW patient was matched to a control patient of the same department not being treated by students (CG1) and to a patient of the same specialty at other hospitals in Germany (CG2). CEW patient data were compared to both CGs using the Mann-Whitney-U-test; statistical correlation between several items was calculated using the Spearman rank correlation (rS).

The PIQ ends with two open questions: “If you wanted to change anything in the hospital, or if you would have a wish, what would it be?” and “What in particular did you appreciate?” Free-text answers to these questions were quantitatively and qualitatively evaluated. First the replies were encoded into different categories (e.g. comment on “medical care” or on “hospital food and equipment”) as well as sub-coded as praise or criticism. Encoding was performed by one author (CS) and verified by another (GL). Next the replies were subject to qualitative content analysis (Mayring Citation2000) by both authors reaching discursive consensus.

Results

Response rate and patient characteristics are presented in .

Table 1. Description of clinical education wards (CEWs) and patients.

Picker Inpatient Questionnaire

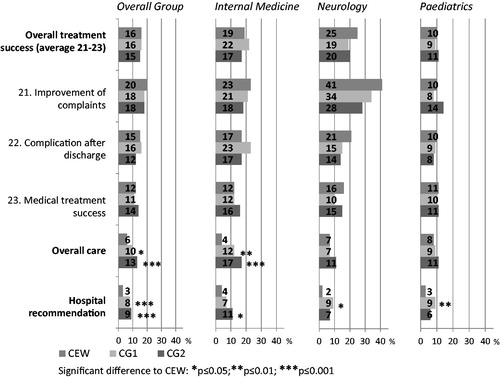

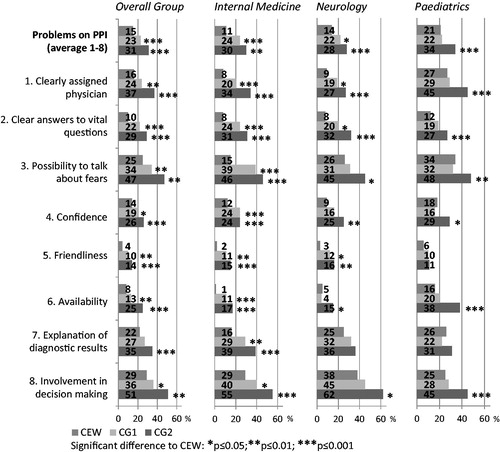

The CEWs show no significant differences regarding the problem frequency (PF) on treatment success from the patients points of view. In total, general quality of care as well as recommendation are rated higher by CEW patients (see ). A significantly lower PF is found in physician/student-patient interaction at the CEWs compared to both control groups (see ).

Student participation in patient care

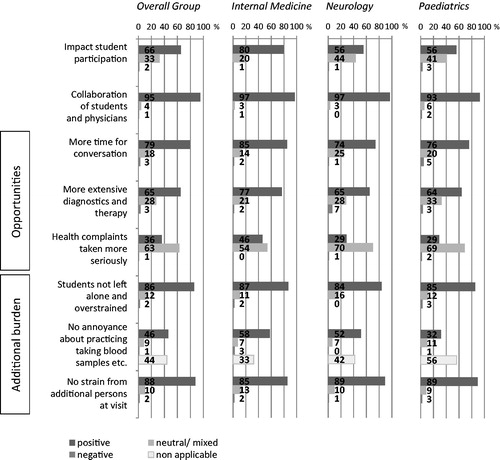

On average, approximately two thirds (65.5%) of the respondents indicate that student participation has a positive effect on treatment and 1.6% report negative effects (see ). Additional burdens are reported by an average of 2% or fewer respondents. 95% of the respondents are satisfied with the cooperation between physicians and students.

displays correlations between student participation and student-physician collaboration with physician/student-patient interaction (PPI), overall quality of care questions and recommendation rate, with the strongest correlations between overall quality of care with student-physician collaboration as well as with PPI, and between PPI with hospital recommendation.

Table 2. Spearman rank correlation (rS).

Free-text answers

In total, 859 individual statements were encoded from which 374 were criticizing statements (negative n = 374; 43.5%). Most of the statements refer to equipment, food, and location of the hospital (n = 292; negative n = 208; 71.2%) and to the overall impression (n = 252; negative n = 30; 12%).

Students are seldom (9x) mentioned critically (physician care 28x, nursing staff 26x), also the ratio of criticism vs. praise is relatively low for the students (proportion of criticism 18.0 vs. 43.8% for physicians and 34.7% for nursing staff). Qualitative analysis of free-text responses is shown in .

Table 3. Qualitative analysis of free-text responses.

Discussion

The CEWs were primarily established for educational reasons. To enhance preparedness of graduates, students were integrated in hospital ward teams and acted as physicians with an autonomous relationship with their patients, supported by close supervision and a guided reflection regarding intra- and interpersonal challenges. The research was performed to explore how such an intensive form of SAP in a hospital setting would impact the perceived quality of care.

Results of the PIQ show that the patient-reported treatment success regarding the negative aspects “complications after discharge” or “no improvement of complaints” () do not differ significantly between the CEW group and controls. This result could be expected since every important medical decision was made in concordance with the physician responsible. The dimension of “patient-physician/student interaction (PPI)” is rated high for the CEW group, when compared to the CG lower PF being significant in at least seven of eight items, including getting clear and understandable answers to vital questions, having a physician/student to talk about fears and worries, or having a trusting relationship with physician/student (). Patients also felt highly involved in medical decisions. The PPI dimension was related to a good overall quality of care at the CEWs. The recommendation rate (), which can be seen as the most critical quality indicator, was high at all CEW groups, showing a significant lower PF compared to controls.

The relevance of SAP for the favorable results at the CEWs is supported both by the vast majority of respondents (65.5%) perceiving the students impact on quality of care as positive and by this item correlating moderately with the high recommendation rate ().

The qualitative results () illustrate how students were in general perceived as committed, warmhearted and, competent. Apart from organizational advantages such as having more time for conversation and students higher availability, patients especially appreciated that students practiced a close and understandable communication, promoting a deeper understanding of patients condition and treatment, leading to comprehensive and personal care. A minority of patients described some disadvantages such as too little or too late physician contact or the uncertainty of students ().

Our results are in accordance with first results of interprofessional CEWs, where patients reported high satisfaction in general (Lindblom et al. Citation2007) and specifically with being well informed and highly involved in decision-making (Reeves et al. Citation2002; Hallin et al. Citation2011). It has been discussed that the patients appreciation of the CEWs is due to interprofessional education (Hallin et al. Citation2011) or due to structural advantages such as having more staff at the ward (Reeves et al. Citation2002). However, our results indicate that students active participation itself contributes to an improvement in the perceived quality of care.

This raises the question why involving novices in a team of health care professionals should have such a positive impact. The presented results are even more surprising if the inexperience and often accompanying uncertainty of the students are considered and that clinical teaching may result in patients feeling objectified and alienated (McLachlan et al. Citation2012) or treated as objects of learning (Elsey et al. Citation2017). Bleakley and Bligh (Citation2008) have pointed out the significance of an autonomous relationship between students and patients, with the doctors as a resource. They call for a new type of apprenticeships, where clinical teaching is not reduced to students re-producing information but where students are supported in understanding their patients themselves. While those reflections were more fundamental, our study provides data to support the related hypothesis that students could have a significant role in patient care and that an autonomous relationship between student and patient is vital for patient-centeredness.

The qualitative analysis of patients free-text answers in our study ( and ) indicates which benefits patients may experience through student participation. Students were perceived not (only) as beginners but also as good collaborators, competent supporters, with a warmhearted attitude, and high engagement, with a patient-oriented dialog that led to an extensive understanding of their situation and to a feeling of being taken seriously and of comprehensive personal care.

The high correlation rate between student/supervising physician collaboration and the overall quality of care highlights the importance patients place on appropriate clinical supervision. Thus, while the supervising clinicians give up parts of their role as first contact person, they are perceived as vital for successful SAP.

Such models with high levels of SAP depend on the openness of a team to involve students as full team members with real contributions. The asymmetric dependency, where the expert trains the novice, is changed to a collaborative relationship. Clinicians are in the role not only of experts but also of educators, collaborators, professionals, learners, and managers facilitating the processes of education and of care. Both students and clinicians are seen as interdependent co-producers of learning (Shipengrover and James Citation1999; Steven et al. Citation2014). Furthermore, patients and their relatives who want to understand their disease and the best way to cope with it are also involved as relevant producers of learning.

Strengths and limitations

The impact of student participation in patient care has been studied frequently in general practice (Bentham et al. Citation1999; O’Flynn et al. Citation1999; Prislin et al. Citation2001; Benson et al. Citation2005; Haffling and Håkansson Citation2008; Price et al. Citation2008; Mol et al. Citation2011) and in outpatient settings (Frank et al. Citation1997; Simon et al. Citation2000; Gress et al. Citation2002) but rarely in hospital inpatient settings. Similar studies were performed in two other CEWs (Reeves et al. Citation2002; Hallin et al. Citation2011) but with far fewer patients (n = 34 and 86, respectively) and within one clinical setting. To our knowledge, ours is the first matched-pairs controlled study within different specialties in hospital settings. The presented results are based on a reasonable number of patients in three different settings with, in total, 74 students and 13 supervising physicians. The influence of individual participants can therefore be considered negligible. The use of the PIQ as a validated and widely used instrument allowed the CEW groups to be compared with matched pairs of two control groups. The combination with the developed questionnaire on SAP enabled students contributions to be related to perceived quality of care. Qualitative analysis of free text responses provided an insight into patients perceptions on the students role in their care. Our results are in accordance with the pilot study results (Scheffer et al. Citation2010; Citation2013) as well as with findings of other CEW patient surveys (Reeves et al. Citation2002; Hallin et al. Citation2011), in which comparable treatment success and favorable communication qualities were reported.

In evaluating present results, it should be considered that only subjective patients perspectives were taken into account and that they do not represent objective quality parameters. In the 360° evaluation of the CEW pilot study, internal medicine staff members, however, pictured a similar positive impact on patient care (Scheffer et al. Citation2010). Another limitation is that all three CEWs are in somatic or conservative medicine and a generalization of the results to surgical or psychiatric disciplines should be viewed with care. Furthermore, it has to be considered that participation on the CEW is not mandatory and that students participate of their own free will.

Our data are based on patients perception regarding the general quality of care and the students impact on it. However, there may be more important factors influencing the quality of care that are not captured by this method, such as the impact of SAP on involved professionals as a result of more reflection through students questions, through clinical teaching and through being asked to act as a role model. A further relevant factor may be the implemented clinical reflection training (Lutz et al. Citation2013, Citation2016), where students train intra- and interpersonal competencies regarding real professional dilemmas.

Regarding the discussion on influencing factors for empathy and patient centeredness during clinical education, our data do not allow to analyze students individual developments. However, students contributed significantly to a patient centered practice and this raises the question whether SAP, realized with an autonomous role, a close supervision, and a guided reflection training enhances learners empathy.

It is important to recognize that the described CEWs at WHU were implemented with additional human resource involvement, especially concerning student coordination, clinical reflection and staff training. The authors have found that it is also important to provide a continuous relationship between the supervising physician and the students, possibly interfering with rotation plans. This also requires more attention, time, and resources. However, on the positive side, the involved departments can benefit from a good patient recommendation rate and from being able to attract and select good students as future staff.

Conclusions

Our main finding is that, from a patient’s view, students can play a valuable role in hospital care. SAP as realized in the presented CEWs is not related to impairment of perceived quality of care; it is related to high patient-centeredness. These findings open new perspectives on clinical education with students as active members of hospital teams contributing to patient-centeredness of health care.

Ethical approval

The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, including, but not limited to the guaranteed anonymity of participating patients and their informed consent being obtained.

Glossary

Clinical education wards (CEWs): Combine hospital based clinical care with education and active participation of health care students. The original CEWs in Sweden and the UK emphasized interprofessional learning with students of different health professions, including medical students before their final year, participating for two weeks at an orthopedic ward. A second form of CEW was developed at Witten/Herdecke University in Germany. Here, the focus is primarily on supported active participation and on responsibility driven learning of medical students with a longer rotation period of 12–16 weeks and a wide range of patients including non-elective patients in acute emergencies.

Notes on contributors

Christian Scheffer, MD, MME, is working as educator and educational researcher for the Integrated Curriculum for Anthroposophic Medicine at Witten/Herdecke University in Germany. Sheffer is also working as physician (Internal Medicine) at the Gemeinschaftskrankenhaus Herdecke, Germany.

Maria Paula Valk-Draad, MS, is working as educator and educational researcher for the Integrated Curriculum for Anthroposophic Medicine at Witten/Herdecke University in Germany.

Diethard Tauschel, MD, is working as educator and educational researcher for the Integrated Curriculum for Anthroposophic Medicine at Witten/Herdecke University in Germany.

Arndt Büssing, MD, PhD, works as a researcher with a focus on spirituality and coping at Witten/Herdecke University.

Knut Humbroich, MD, is working as physician (Neurology)at the Gemeinschaftskrankenhaus Herdecke, Germany.

Alfred Längler, MD, PhD, is working as physician (Pediatrics)at the Gemeinschaftskrankenhaus Herdecke, Germany.

Tycho Zuzak, MD, PhD, is working as physician (Pediatrics) at the Gemeinschaftskrankenhaus Herdecke, Germany.

Wolf Köster, MD, is working as physician (Internal Medicine) at the Gemeinschaftskrankenhaus Herdecke, Germany.

Friedrich Edelhäuser, MD, PhD, is working as educator and educational researcher for the Integrated Curriculum for Anthroposophic Medicine at Witten/Herdecke University in Germany. Edelhäuser is also working as physician (Rehabilitation) at the Gemeinschaftskrankenhaus Herdecke, Germany.

Gabriele Lutz, MD, is working as educator and educational researcher for the Integrated Curriculum for Anthroposophic Medicine at Witten/Herdecke University in Germany. Lutz is also working as physician (Psychosomatic Medicine) at the Gemeinschaftskrankenhaus Herdecke, Germany.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Eckhart G. Hahn for supporting for the development of the CEW with his considerations and encouragement. We also want to express our gratitude to the three ward teams who were open for new steps and the integration of students. Furthermore, we thank the Picker Institute Germany for their support in surveying the patients. Finally, we would like to thank all students and patients who took part in the CEW and the related study. We would also like to thank Anne Wegner for revising the use of English in this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Benson J, Quince T, Hibble A, Fanshawe T, Emery J. 2005. Impact on patients of expanded, general practice based, student teaching: observational and qualitative study. BMJ. 331:89.

- Bentham J, Burke J, Clark J, Svoboda C, Vallance G, Yeow M. 1999. Students conducting consultations in general practice and the acceptability to patients. Med Educ. 33:686–687.

- Bleakley A, Bligh J. 2008. Students learning from patients: let’s get real in medical education. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 13:89–107.

- Bombeke K, Symons L, Debaene L, De Winter B, Schol S, Van Royen P. 2010. Help, I'm losing patient-centredness! Experiences of medical students and their teachers. Med Educ. 44:662–673.

- Bruster S, Jarman B, Bosanquet N, Weston D, Erens R, Delbanco TL. 1994. National survey of hospital patients. BMJ. 309:1542–1546.

- Bugaj TJ, Schmid C, Koechel A, Stiepak J, Groener JB, Herzog W, Nikendei C. 2017. Shedding light into the black box: a prospective longitudinal study identifying the CanMEDS roles of final year medical students' on-ward activities. Med Teach. 39:883–890.

- Choudhury TR, Moosa AA, Cushing A, Bestwick J. 2006. Patients' attitudes towards the presence of medical students during consultations. Med Teach. 28:e198–e203.

- Collective TD-BR. 2003. Design-based research: an emerging paradigm for educational inquiry. Educ Res. 32:5–8.

- Cooke F, Galasko G, Ramrakha V, Richards D, Rose A, Watkins J. 1996. Medical students in general practice: how do patients feel?. Br J Gen Pract. 46:361–362.

- Daelmans HEM, Hoogenboom RJI, Donker AJM, Scherpbier AJJA, Stehouwer CDA, van der Vleuten CPM. 2004. Effectiveness of clinical rotations as a learning environment for achieving competences. Med Teach. 26:305–312.

- Dornan T, Tan N, Boshuizen H, Gick R, Isba R, Mann K, Scherpbier A, Spencer J, Timmins E. 2014. How and what do medical students learn in clerkships? Experience based learning (ExBL). Adv in Health Sci Educ. 19:721–749.

- Elsey C, Challinor A, Monrouxe LV. 2017. Patients embodied and as-a-body within bedside teaching encounters: a video ethnographic study. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 22:123–146.

- Frank SH, Stange KC, Langa D, Workings M. 1997. Direct observation of community-based ambulatory encounters involving medical students. JAMA. 278:712–716.

- Gaufberg E, Hirsh D, Krupat E, Ogur B, Pelletier S, Reiff D, Bor D. 2014. Into the future: patient-centredness endures in longitudinal integrated clerkship graduates. Med Educ. 48:572–582.

- Gress TW, Flynn JA, Rubin HR, Simonson L, Sisson S, Thompson T, Brancati FL. 2002. Effect of student involvement on patient perceptions of ambulatory care visits: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 17:420–427.

- Haffling AC, Håkansson A. 2008. Patients consulting with students in general practice: survey of patients’ satisfaction and their role in teaching. Med Teach. 30:622–629.

- Hallin K, Henriksson P, Dalén N, Kiessling A. 2011. Effects of interprofessional education on patient perceived quality of care. Med Teach. 33:e22–e26.

- Heusser P, Scheffer C, Neumann M, Tauschel D, Edelhäuser F. 2012. Towards non-reductionistic medical anthropology, medical education and practitioner-patient-interaction: the example of anthroposophic medicine. Patient Educ Couns. 89:455–460.

- Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, Brainard G, Herrine SK, Isenberg GA, Veloski J, Gonnella JS. 2009. The devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 84:1182–1191.

- Hylin U, Nyholm H, Mattiasson AC, Ponzer S. 2007. Interprofessional training in clinical practice on a training ward for healthcare students: a two-year follow-up. J Interprof Care. 21:277–288.

- Illing J, Morrow G, Rothwell nee Kergon C, Burford B, Baldauf B, Davies C, Peile E, Spencer J, Johnson N, Allen M, et al. 2013. Perceptions of UK medical graduates' preparedness for practice: a multi-centre qualitative study reflecting the importance of learning on the job. BMC Med Educ. 13:34.

- Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Bruster S. 2002. The picker patient experience questionnaire: development and validation using data from in-patient surveys in five countries. Int J Qual Health Care. 14:353–358.

- Lave J, Wenger E. 1991. Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press.

- Lindblom P, Scheja M, Torell E, Astrand P, Felländer-Tsai L. 2007. Learning orthopaedics: assessing medical students’ experiences of interprofessional training in an orthopaedic clinical education ward. J Interprof Care. 21:413–423.

- Lutz G, Roling G, Berger B, Edelhäuser F, Scheffer C. 2016. Reflective practice and its role in facilitating creative responses to dilemmas within clinical communication – a qualitative analysis. BMC Med Educ. 16:301.

- Lutz G, Scheffer C, Edelhaeuser F, Tauschel D, Neumann M. 2013. A reflective practice intervention for professional development, reduced stress and improved patient care-a qualitative developmental evaluation. Patient Educ Couns. 92:337–345.

- Mayring P. 2000. Qualitative content analysis. Forum Qual Soc Res. 1:20.

- McLachlan E, King N, Wenger E, Dornan T. 2012. Phenomenological analysis of patient experiences of medical student teaching encounters: patient experiences of student encounters. Med Educ. 46:963–973.

- Mol SSL, Peelen JH, Kuyvenhoven MM. 2011. Patients’ views on student participation in general practice consultations: a comprehensive review. Med Teach. 33:e397–e400.

- Neumann M, Edelhäuser F, Tauschel D, Fischer MR, Wirtz M, Woopen C, Haramati A, Scheffer C. 2011. Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 86:996–1009.

- Nikendei C, Krautter M, Celebi N, Obertacke U, Jünger J. 2012. Final year medical education in Germany. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 106:75–84.

- Ochsmann EB, Zier U, Drexler H, Schmid K. 2011. Well prepared for work? Junior doctors' self-assessment after medical education. BMC Med Educ. 11:99.

- O’Flynn N, Spencer J, Jones R. 1999. Does teaching during a general practice consultation affect patient care? Br J Gen Pr. 49:7–9.

- Ponzer S, Hylin U, Kusoffsky A, Lauffs M, Lonka K, Mattiasson AC, Nordström G. 2004. Interprofessional training in the context of clinical practice: goals and students' perceptions on clinical education wards. Med Educ. 38:727–736.

- Price R, Spencer J, Walker J. 2008. Does the presence of medical students affect quality in general practice consultations?. Med Educ. 42:374–381.

- Prislin MD, Morrison E, Giglio M, Truong P, Radecki S. 2001. Patients’ perceptions of medical students in a longitudinal family medicine clerkship. Fam Med. 33:187–191.

- Reeves S, Freeth D, McCrorie P, Perry D. 2002. ‘It teaches you what to expect in future … ’: interprofessional learning on a training ward for medical, nursing, occupational therapy and physiotherapy students. Med Educ. 36:337–344.

- Remmen R, Denekens J, Scherpbier A, Hermann I, van der Vleuten C, Royen PV, Bossaert L. 2000. An evaluation study of the didactic quality of clerkships. Med Educ. 34:460–464.

- Salisbury K, Farmer EA, Vnuk A. 2004. Patients' views on the training of medical students in Australian general practice settings. Aust Fam Physician. 33:281–283.

- Scheffer C, Edelhäuser F, Tauschel D, Riechmann M, Tekian A. 2010. Can final year medical students significantly contribute to patient care? A pilot study about the perception of patients and clinical staff. Med Teach. 32:552–557.

- Scheffer C, Tauschel D, Neumann M, et al. 2012. Integrative medical education: educational strategies and preliminary evaluation of the Integrated Curriculum for Anthroposophic Medicine (ICURAM). Patient Educ Couns. 89:447–454.

- Scheffer C, Tauschel D, Neumann M, Lutz G, Valk-Draad M, Edelhäuser F. 2013. Active student participation may enhance patient centeredness: patients’ assessments of the clinical education ward for integrative medicine. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013:1–8.

- Schlett CL, Doll H, Dahmen J, et al. 2010. Job requirements compared to medical school education: differences between graduates from problem-based learning and conventional curricula. BMC Med Educ. 10:1.

- Schrauth M, Weyrich P, Kraus B, Jünger J, Zipfel S, Nikendei C. 2009. [Workplace learning for final-year medical students: a comprehensive analysis of student’s expectancies and experiences]. Z Für Evidenz Fortbild Qual Im Gesundheitswesen. 103:169–174. German

- Schutte T, Tichelaar J, Dekker RS, van Agtmael MA, de Vries TPGM, Richir MC. 2015. Learning in student-run clinics: a systematic review. Med Educ. 49:249–263.

- Shipengrover JA, James PA. 1999. Measuring instructional quality in community-orientated medical education: looking into the black box. Med Educ. 33:846–853.

- Simon SR, Peters AS, Christiansen CL, Fletcher RH. 2000. The effect of medical student teaching on patient satisfaction in a managed care setting. J Gen Intern Med. 15:457–461.

- Smith SE, Tallentire VR, Cameron HS, Wood SM. 2013. The effects of contributing to patient care on medical students' workplace learning. Med Educ. 47:1184–1196.

- Spencer J, Blackmore D, Heard S, McCrorie P, McHaffie D, Scherpbier A, Gupta TS, Singh K, Southgate L. 2000. Patient-oriented learning: a review of the role of the patient in the education of medical students. Med Educ. 34:851–857.

- Steven K, Wenger E, Boshuizen H, Scherpbier A, Dornan T. 2014. How clerkship students learn from real patients in practice settings. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 89:469–476.

- Thistlethwaite JE, Cockayne EA. 2004. Early student-patient interactions: the views of patients regarding their experiences. Med Teach. 26:420–422.

- Wahlström O, Sandén I, Hammar M. 1997. Multiprofessional education in the medical curriculum. Med Educ. 31:425–429.

- Wenger E. 1999. Communities of practice: learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press.