Abstract

Purpose: Patients who have access to information online may feel empowered and also confront their physicians with more detailed questions. Medical students are not well-prepared for dealing with so-called “e-patients.” We created a teaching module to deal with this, and evaluate its effectiveness.

Method: Senior medical students had to manage encounters with standardized patients (SPE) in a cross-over design. They received blended-learning teaching on e-patients and a control intervention according to their randomization group (EI/LI = early/late intervention). Each SPE was rated by two blinded video raters, the SP and the student.

Results: N = 46 students could be included. After the intervention, each group (EI, LI) significantly improved their competency in dealing with e-patients as judged by expert video raters (EI: MT0 = 9.75 (2.51) versus MT1 = 16.60 (2.80); LI: MT0 = 8.70 (2.14) versus MT2 = 15.20 (2.84); both p < 0.001) and SP (EI: MT0 = 24.13 (4.83) versus MT1 = 26.52 (3.06); LI: MT0 = 23.37 (3.10) versus MT2 = 27.47 (4.38); both p < 0.001). Students’ rating showed a similar non-significant trend.

Conclusions: Students, SP and expert video raters determined that blended-learning teaching can improve students’ competencies when dealing with e-patients. Within the study period, this effect was lasting; however, further studies should look at long-term outcomes.

Introduction

More than four billion people access the Internet (World Internet Users and Population Stats. From http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm last accessed May 2018), and health information on the Internet has become important in medical care. Patients who use the Internet to inform themselves about health are considered “e-patients” (Forkner-Dunn Citation2003; Ferguson Citation2007).

For these patients, the Internet is a source of empowerment that impacts on the patient–physician relationship, as they take an active role in their medical care, making informed choices or even self-medicating (Ball and Lillis Citation2001; Charles et al. Citation2003; Godolphin Citation2003; Hesse et al. Citation2005; Gottlieb et al. Citation2008; Hellenthal and Ellison Citation2008; Simmons et al. Citation2009; Jirasevijinda Citation2015).

There are many reasons that patients search for health information on the Internet, including obtaining a better understanding of medical problems, frustration about patient–physician encounters, seeking a second opinion online, self-empowerment for future encounters, or reading about what has been discussed with the doctor (Eysenbach Citation2003; McMullan Citation2006; Shmueli et al. Citation2017). In addition, social media seems to be important for patients with chronic medical conditions (Thompson et al. Citation2017).

The advantages of these activities include patients’ saving time finding new information, maintaining anonymity when obtaining information about diagnoses or symptoms of socially stigmatized conditions, and more equal discussions with their doctors (Rice Citation2006; Fox and Duggan Citation2013). Many physicians find these consultations enriching, and are able to utilize their patients’ level of information (Eysenbach Citation2003; Forkner-Dunn Citation2003; Debronkart Citation2013).

Contrastingly, however, some physicians consider Internet-informed patients “difficult” (Godolphin et al. Citation2001; Elwyn et al. Citation2013; Couët et al. Citation2015), and may request patients to limit their research about health conditions (Masters et al. Citation2010). Physicians are challenged by the changes in their face-to-face consultations, as they are often expected to react quickly and comprehensively. Some physicians worry about e-patients’ having wrong information, asking more questions and needing more time and attention during consultations (Eysenbach Citation2003; Forkner-Dunn Citation2003; Debronkart Citation2013).

E-patient research has argued that resolving these complexities and dealing effectively with e-patients to ensure a healthy patient–physician relationship requires teaching of specific knowledge, skills and attitudes (Masters, Ng’ambi and Todd Citation2010; Masters Citation2015, Citation2017). To the best of our knowledge, there is no scientific investigation concerning the doctor’s self-image and its potentially being threatened when meeting a well-informed e-patient.

At the Medical Faculty Tuebingen, medical students are confronted with simulated patient-physician encounters and communication training from the very beginning of their education. Such training has been shown to be effective and well-accepted (Werner et al. Citation2013; Choudhary and Gupta Citation2015; Boissy et al. Citation2016; Silverman et al. Citation2016). Griewatz et al. (Citation2016) provide one training session on the management of patient forums online. However, these medical students are not yet properly prepared to deal with well-informed e-patients in patient–physician encounters, even though guidelines exist (Masters Citation2017).

As a result of the needs outlined above, and taking into account the suggestions in the literature, we created a teaching module on how to deal with e-patients in face-to-face consultations, and evaluated its effectiveness and acceptance with medical students. We wished to answer the following question: Can medical students be taught to communicate effectively with e-patients who bring material from the Internet into the consultation?

Methods

Ethics

The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Tuebingen Medical Faculty (No. 439/2017BO2) in June 2017.

Study design and participants

We conducted a randomized controlled trial in cross-over design with medical students from the medical faculty of the University of Tuebingen in their two final (5th and 6th) years from August to December 2017. We decided to use a cross-over design as this would allow us to have a control group while simultaneously allowing all students to have the benefits of the intervention. Participation was voluntary.

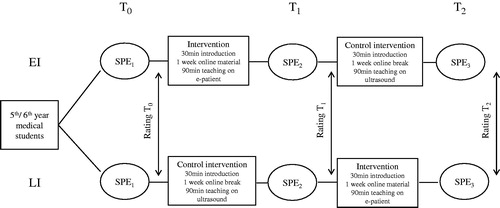

Students were randomly assigned to either an Early Intervention (EI) or Late Intervention group (LI). Calculated sample size was n = 17 per group (power 0.8; effect size 0.5, level of significance 0.95). Students faced three SP-cases which lasted approximately 10 min each and were video-recorded for later review by two blinded experts. Students and SP rated the SP encounters (SPE). For details on study design, see .

Figure 1. Study design. EI = early intervention group, LI = late intervention group, SPE = Simulated patient encounter. Rating: T0–T2 binary checklist and global item by 2 video raters, JSPPE (Jefferson scale of patient perception of physician empathy) and global item by SP, global item by students. T1 (EI) and T2 (LI) additionally course evaluation by students.

Simulated patients (SP)

The study used encounters with SP. All SP were well established actors from our faculty’s SP program with ample experiences in communication classes. They received additional specific training for the three cases of this study. SP were blinded whether students were from EI or LI. Each SP case was designed to represent a specific medical condition (diabetes, gluten intolerance or myocarditis), where the patient played the role of an e-patient, and presented a web-page on a tablet to the doctor. Each student only saw each case and each SP once, and cases were also permutated to allow for possible differences in difficulty.

Intervention

The content of the intervention was based on experience, literature from the field as well as 10 semi-structured interviews with final-year medical students. We created a teaching format in blended-learning style: 30-min session: Students started with an introductory session of 30 min, outlining the content of the class.

Self-study period: The 30-min session was followed by a self-study period of 1 week. For that period, students had password-protected online-access to seven specifically created videos. One video was designed as a news program offering background information about the topic (e.g. characteristics of e-patients, quality signs for online sources, etc.). The remaining videos showed short clips of patient-physician encounters highlighting specific strategies on how to deal with e-patients (e.g. exploring the patient’s source of information, defuse worst case scenarios, etc.). All videos explicitly stated the used strategies as subtitles. Total video time was approximately 1 h. The number of student logins and the number of times they watched the videos was electronically recorded.

90-min session: One week after the first introductory session, students had their second face-to-face encounter. First, their experience with the online material was discussed followed by watching a full simulated patient-physician encounter where the patient presented information found on the internet. All strategies used by the doctor where discussed interactively with the students. Afterwards, students practiced the learned strategies in role-plays with structured feedback. This session lasted for 90 min and was attended by four to six students. Teachers were experienced clinicians who also taught classes in the regular communication curriculum. They received specific additional training for this class including a standardized manual (e.g. definition of e-health and e-patients, effective ways to communicate with patients bringing information found online, quality criteria for webpages).

Control intervention

The Control Intervention consisted of the same amount of face-to-face time teaching with

30 min session: introduction.

1-week-break: without any teaching and also without access to the online teaching material.

90 min session: ultrasound training also in groups of 3–5 students.

Video rating

All videos were rated by two blinded video raters. They were both skilled clinical psychologists with additional experience in communication. They received a 30 minerature (Kiley Citation2002; Griffiths and Christensen Citation2005; Hesse et al. Citation2005; Bylund et al. Citation2007; Masters Citation2017; Robledo and Jankovic Citation2017; Wald et al. Citation2007). The checklist referred to general communication behavior and specific strategies in the handling of e-patients with three subscales: (a) integration of the information found online, (b) source verification, and (c) discussion of the information’s content. One additional global item rated the overall competency of the student in the SPE from 1 = “not at all competent” to 10 = “very competent.”

SP rating

After each SPE, the SP completed the Jefferson Scale of Patient Perception of Physician Empathy (JSPPE) which measures perceived empathy with five items on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = “do not agree at all” to 7 = “agree completely”). Additionally, SP rated how the student integrated the information and took them seriously within 6 items on a 10-point Likert scale (1 = “not at all competent” to 10 = “very competent”).

Student rating

After each SPE, students filled in a questionnaire and rated their own performance in their role as a doctor on a 10-point Likert scale (1 = “not at all competent” to 10 = “very competent”). They also evaluated the teaching module.

Data analysis

When both student groups had completed their encounters and interventions, the data were analyzed. Mean values, standard deviations, frequencies and percentages of relevant factors were calculated. To discover changes in the video rating from T0 to T1 to T2 and between EI and LI T-Tests for dependent samples and ANOVAs were used. Inter-rater reliability was calculated based on the Intra-Class-Correlation-Coefficient (ICC). T-tests for dependent samples were conducted to compare the students’ self-reported learning success. ANOVAS were performed to discover changes in the SP rating of students’ communication skills over time and between groups. The level of significance was p < .05. Effect sizes for significant effects between groups at T1 were calculated using Cohen’s d with regard to unequal variances and group size (0.2–0.5 small effect size, 0.5–0.8 medium effect size, >0.8 large effect size; d ranging from −∞ to +∞) (Cohen Citation1988). Correction for multiple testing was based on Bonferroni correction. Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

Participants

N = 50 medical students participated in the study. N = 2 data sets had to be excluded due to technical reasons (video not recording properly). Another two students canceled their participation after T0. Accordingly, n = 46 students could be included into the data analyses (average age 25.4 (2.3) years, 74% female), of which n = 26 had randomly been assigned to EI, and n = 20 to LI, respectively. N = 3 medical students of the EI could not participate in the third SPE for organizational reasons. There were no significant differences between the two groups with regards to age, gender and previous formal medical training (e.g. nurse, paramedic). All participants had prior experience with training in communication. Regarding the online learning material, the majority of students participating in this study watched the preparatory videos once on the day before the intervention took place.

Video rating – binary checklist

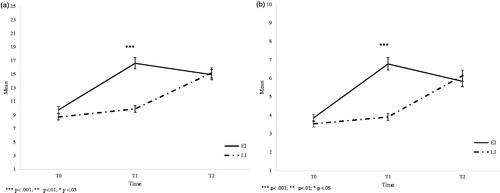

Inter-rater reliability measured with ICC coefficient was satisfactory with 0.69. There was no significant difference between the two groups regarding students’ competencies at T0 (EI: M = 9.75 (2.51); LI: M = 8.70 (2.14); p > 0.05). At T1, EI was rated significantly better regarding their communication skills compared to T0 as well as in comparison to LI with a large effect size (EI: M = 16.60 (2.80); LI: M = 9.90 (2.22); p < 0.001; d = 2.61). At T2, the rating of the EI remained high (M = 14.94 (2.36)) whereas LI ratings increased significantly (M = 15.20 (2.84)). At that point, there was no significant difference between the groups (p > 0.05) (see ).

Video rating – overall competency

Overall competency was moderate with no significant difference between LI and EI at T0 (EI: M = 3.85 (1.33); LI: M = 3.53 (1.40); p > 0.05). At T1 EI ratings had risen significantly creating a significant difference between the two groups with a large effect size (EI: M = 6.77 (1.19), p < 0.001; LI: 3.90 (1.21); p < 0.001; d = 2.39). At T2, ratings for LI had significantly risen (p < 0.001), ratings for EI stayed elevated, and there was no difference between the two groups (EI: M = 5.83 (0.91); LI: M = 6.13 (1.36); p > 0.05) (see ).

SP rating – JSPPE

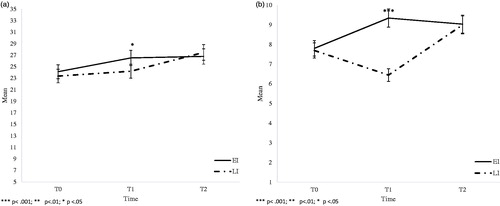

At T0, there was no significant difference between the two groups (EI: M = 24.13 (4.83); LI: M = 23.37 (3.10); p > 0.05). At T1, the SP rated EI students significantly more empathic than at T0 and compared to LI with a medium effect size (EI: M = 26.52 (3.06); LI: M = 24.21 (3.63); p < 0.05; d = 0.69). Again, this difference was no longer apparent at T2, as LI caught up in ratings significantly (p < 0.01) leaving no significant difference between the two groups (EI: M = 26.78 (4.19); LI: M = 27.47 (4.38); p > 0.05) (see ).

SP rating – students’ competency

The SP evaluated the students as equally competent at T0 (EI: M = 7.81 (1.74); LI: M = 7.70 (0.92); p > 0.05). As expected, at T1, there was a significant difference between the two groups with a large effect size (EI: M = 9.35 (0.63); LI: M = 6.45 (1.76); p < 0.001; d = 2.32). At T2, the competency of LI students increased significantly (p < 0.001) and the two groups showed ratings with no significant differences (EI: M = 9.04 (0.77); LI: M = 9.00 (0.86); p > 0.05) (see ).

Student rating – competency

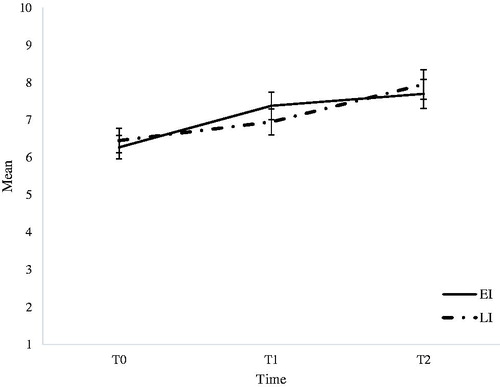

There were no significant differences between the two groups at each time point (EI: MT0=6.27 (2.29) versus LI: MT0=6.45 (1.50); EI: MT1=7.38 (1.58) versus LI: MT1=6.95 (1.93); EI: MT2=7.70 (1.22) versus LI: MT2=7.95 (1.40); p > 0.05). However, the competency of EI increased significantly from T0 to T1 (p < 0.05). The competency of LI also rose significantly from T0 to T2 (p < 0.001), resulting in no significant difference at this point (see ).

Student rating – evaluation of the course module

Of the students in the study, 95% reported greater confidence when handling e-patients after training, and felt well-prepared for clinical situations. In addition, 91% mentioned they were capable of giving good advice on Internet research as a result of training. However, 35% of the students reported that a critical cross-check of Internet sources still remained a problem. The online material was seen as useful addition by 87% of the students. Over 90% of the participants requested the implementation of the module into the core medical curriculum.

Discussion

Overall

In this study, a short communication training in blended-learning style significantly improved medical students’ competency when dealing with e-patients as rated by experts and SP. SP using the JSPPE equally found students more empathic after they had gone through the intervention. Students themselves also saw an improvement of their competencies over time, however, this gain was irrespective of their group assignment (EI/LI) which might indicate that students’ self-perception may additionally be influenced by the number of SPEs they had to face, getting more and more used to the setting.

As stated in the literature, students have to be taught and learn how to deal successfully and constructively with e-patients as they are already shaping the patient-physician encounters (Ellaway and Masters Citation2008; Masters et al. Citation2010; Masters Citation2015, Citation2017). We feel confident that our teaching format contributes to successful face-to-face encounters with e-patients. Students evaluated the new teaching well and requested its implementation into the regular curriculum. Although results in literature are heterogeneous, this study showed that blended-learning formats can be at least as effective as traditional teaching and our students appreciated its possibilities (Liu et al. Citation2016).

We saw that students derived clear benefits from the newly developed teaching module with its effects being repeatedly confirmed in different outcome measures within the present study. The newly-created online as well as in-class material is of high quality, and the issue of e-patients will gain even more attention in the medical field within the next years (Masters Citation2017). The teaching of this module will, thus, be implemented as a mandatory class into the existing communication curriculum.

Limitations

There are some limitations regarding the generalisability of the present data. First, we conducted the study at only one medical faculty. Second, as participation was on a voluntary basis, there might also be a selection bias. Students taking part in this study were probably interested in the topic and found it necessary to implement the new communication training into the medical curriculum beforehand. They could have also in general been more interested in the topic of e-health and shared decision making between doctors and patients. Their opinion could perhaps not be shared by the majority of medical students. A general survey about e-patients and the need of communication training could deliver more answers about the attitude of medical students towards the issue.

In this study, it could be observed that the majority of students watched the online material only once and also shortly before their in-class session. When we integrate the new course module into the regular medical curriculum, ways of motivating students to use the provided material more intensively should be considered.

Finally, although seeking information on the Internet and bringing it to the consultation is probably the most obvious e-patient activity, e-patients engage in other activities (Masters et al. Citation2010) that have not been addressed in this study.

Conclusion

As an answer to the main research question of this study, whether medical students could be taught to work effectively with e-patients who bring material from the Internet into the consultation, we can conclude as follows: based on our data, students, SPs, and expert video raters determined that blended-learning teaching can improve students’ competencies when dealing with e-patients. Within our study period, this effect was lasting; however, further studies should look at long-term outcomes. Future research will investigate other e-patient topics, such as communication in online encounters, digital navigation on the Internet, and management of one’s digital footprint.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Lisa Wiesner, student assistant, and Dr Annette Wosnik, head of the dean’s office of student affairs Medical Faculty Tuebingen, who were both most helpful with and supportive of the project.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

A. Herrmann-Werner

Anne Herrmann-Werner, MD, MME, is a Senior Physician for Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy at University Hospital Tuebingen, and the head of the faculty’s skills lab. She is mainly responsible for undergraduate medical students’ communication training, and her research interests lie in peer-assisted learning and communication in the digital age.

H. Weber

Hannah Weber is medical student, Medical Faculty Tuebingen. This survey is part of her dissertation to get her medical degree.

T. Loda

Teresa Loda MS, is a psychologist and research scientist at the Department for Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy at University Hospital Tuebingen. She is mainly responsible for teaching projects that focus on peer-assisted learning.

K. E. Keifenheim

Katharina Keifenheim MD is a specialist physician at the Department for Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy at University Medical Hospital Tuebingen.

R. Erschens

Rebecca Erschens Diplom, is a clinical psychologist, research scientist and lecturer at the Department for Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy at University Medical Hospital Tuebingen.

S. C. Mölbert

Simone Mölbert PhD, is a clinical psychologist, research scientist and lecturer at the Department for Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy at University Medical Hospital Tuebingen.

C. Nikendei

Christoph Nikendei MD, MME is Professor for General Internal Medicine and Psychosomatics at the University Hospital Heidelberg. He is responsible for skills-lab training, stress prevention programs, final year and international students’ education at the University of Heidelberg. He was honored with AMEE`s 2008 Miriam Friedman Ben-David Award.

S. Zipfel

Stephan Zipfel MD, is Professor for Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy at University Hospital Tuebingen, and dean for student affairs at the Faculty of Medicine of Tuebingen University.

K. Masters

Ken Masters, PhD, HDE, FDE, Assistant Professor of Medical Informatics, SQU, Oman, has been involved in medical education for over a decade. His publications consider educational theory, technologies, strategies, and softer areas (e.g. ethics, e-patient). He teaches the concept of the e-patient as part of a medical informatics course.

References

- Ball MJ, Lillis J. 2001. E-health: transforming the physician/patient relationship. Int J Med Inform. 61:1–10.

- Boissy A, Windover AK, Bokar D, Karafa M, Neuendorf K, Frankel RM, Merlino J, Rothberg MB. 2016. Communication skills training for physicians improves patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 31:755–761.

- Bylund CL, Gueguen JA, Sabee CM, Imes RS, Li Y, Sanford AA. 2007. Provider-patient dialogue about Internet health information: an exploration of strategies to improve the provider-patient relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 66:346–352.

- Charles CA, Whelan T, Gafni A, Willan A, Farrell S. 2003. Shared treatment decision making: what does it mean to physicians? J Clin Oncol. 21:932–936. Epub 2003/03/01.

- Choudhary A, Gupta V. 2015. Teaching communications skills to medical students: introducing the fine art of medical practice. Int J App Basic Med Res. 5:41.

- Cohen J. 1988. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale (NJ): Erlbaum.

- Couët N, Desroches S, Robitaille H, Vaillancourt H, Leblanc A, Turcotte S, Elwyn G, Légaré F. 2015. Assessments of the extent to which health‐care providers involve patients in decision making: a systematic review of studies using the OPTION instrument. Health Expect. 18:542–561.

- Debronkart D. 2013. How the e-patient community helped save my life: an essay by Dave deBronkart. BMJ (Clinical Research ed). 346:f1990.

- Ellaway R, Masters K. 2008. AMEE Guide 32: e-Learning in medical education Part 1: learning, teaching and assessment. Med Teach. 30:455–473.

- Elwyn G, Scholl I, Tietbohl C, Mann M, Edwards AGK, Clay C, Légaré F, Weijden T. v d, Lewis CL, Wexler RM, et al. 2013. “Many miles to go…”: a systematic review of the implementation of patient decision support interventions into routine clinical practice. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 13:S14.

- Eysenbach G. 2003. The impact of the Internet on cancer outcomes. CA Cancer J Clin. 53:356–371. Epub 2004/07/01.

- Ferguson T. 2007. Patients: how they can help us heal healthcare. e-Patients. net. MD and e-Patient Scholars Working Group, 12.

- Forkner-Dunn J. 2003. Internet-based patient self-care: the next generation of health care delivery. J Med Internet Res. 5:e8. Epub 2003/07/15.

- Fox S, Duggan M. 2013. Health online 2013. Washington (DC): Pew Internet & American Life Project.

- Godolphin W. 2003. The role of risk communication in shared decision making. BMJ. 327:692–693. Epub 2003/09/27.

- Godolphin W, Towle A, McKendry R. 2001. Challenges in family practice related to informed and shared decision-making: a survey of preceptors of medical students. CMAJ. 65:434–435. Epub 2001/09/04.

- Gottlieb K, Sylvester I, Eby D. 2008. Transforming your practice: what matters most. Fam Pract Manag. 15:32–38. Epub 2008/02/19.

- Griewatz J, Lammerding-Koeppel M, Bientzle M, Cress U, Kimmerle J. 2016. Using simulated forums for training of online patient counselling. Med Educ. 50:576–577. Epub 2016/04/14.

- Griffiths KM, Christensen H. 2005. Website quality indicators for consumers. J Med Internet Res. 7:e55.

- Hellenthal N, Ellison L. 2008. How patients make treatment choices. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 5:426–433. Epub 2008/08/07.

- Hesse BW, Nelson DE, Kreps GL, Croyle RT, Arora NK, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. 2005. Trust and sources of health information: the impact of the Internet and its implications for health care providers: findings from the first Health Information National Trends Survey. Arch Intern Med. 165:2618–2624.

- Jirasevijinda T. 2015. Reaching into our doctor’s bag of tricks to help patients navigate health information technology. J Commun Healthcare. 8:255–257.

- Kiley R. 2002. Does the internet harm health? Some evidence exists that the Internet does harm health. BMJ. 324:238–239.

- Liu Q, Peng W, Zhang F, Hu R, Li Y, Yan W. 2016. The effectiveness of blended learning in health professions: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 18:e2.

- Masters K. 2015. The e-patient and medical students. Med Teach. 30:1–3.

- Masters K. 2017. Preparing medical students for the e-patient. Med Teach. 39:681–685.

- Masters K, Ng’ambi D, Todd G. 2010. “I Found it on the Internet”: preparing for the e-patient in Oman. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 10:169–179. Epub 2011/04/22.

- McMullan M. 2006. Patients using the Internet to obtain health information: how this affects the patient-health professional relationship. Patient. Educ Couns. 63:24–28. Epub 2006/01/13.

- Rice RE. 2006. Influences, usage, and outcomes of Internet health information searching: multivariate results from the Pew surveys. Int J Med Inform. 75:8–28.

- Robledo I, Jankovic J, 2017. Media hype: patient and scientific perspectives on misleading medical news. Mov Disord. 32: 1319–1323. Epub 2017/04/04.

- Shmueli L, Davidovitch N, Pliskin JS, Balicer RD, Hekselman I, Greenfield G. 2017. Seeking a second medical opinion: composition, reasons and perceived outcomes in Israel. Isr J Health Policy Res. 6:67. Epub 2017/12/10.

- Silverman J, Kurtz S, Draper J. 2016. Teaching and learning communication skills in medicine. London: CRC Press.

- Simmons L, Baker NJ, Schaefer J, Miller D, Anders S. 2009. Activation of patients for successful self-management. J Ambul Care Manage. 32:16–23. Epub 2008/12/24.

- Thompson MA, Ahlstrom J, Dizon DS, Gad Y, Matthews G, Luks HJ, Schorr A. 2017. Twitter 101 and beyond: introduction to social media platforms available to practicing hematologist/oncologists. Semin Hematol. 54:177–183. Epub 2017/11/21.

- Wald HS, Dube CE, Anthony DC. 2007. Untangling the Web—the impact of Internet use on health care and the physician–patient relationship. Patient Educ Counsel. 68:218–224.

- Werner A, Holderried F, Schäffeler N, Weyrich P, Riessen R, Zipfel S, Celebi N. 2013. Communication training for advanced medical students improves information recall of medical laypersons in simulated informed consent talks–a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 13:15.