Abstract

Introduction: Student-staff partnerships as a concept to improve medical education have received a growing amount of attention. Such partnerships are collaborations in which students and teachers seek to improve education by each adding their unique contribution to decision-making and implementation processes. Although previous research has demonstrated that students are favourable to this concept, teachers remain hesitant. The present study investigated teachers’ conceptions of student-staff partnerships and of the prerequisites that are necessary to render such partnerships successful and enhance educational quality.

Method: We conducted semi-structured interviews with 14 course coordinators who lead course design teams and also teach in 4 bachelor health programmes, using Bovill and Bulley’s levels of student participation as sensitising concepts during data analysis.

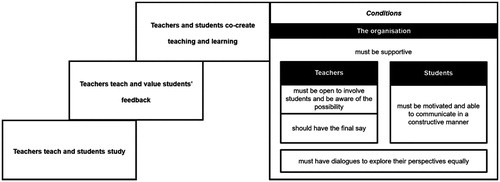

Results: The results pointed to three different conceptions of student-staff partnerships existing among teachers: Teachers teach and students study; teachers teach and value students’ feedback; and teachers and students co-create. The prerequisites for effective co-creation teachers identified were: Teachers must be open to involve students and create dialogues; students must be motivated and have good communication skills; the organisation must be supportive; and teachers should have the final say.

Conclusion: We conclude that teachers’ conceptions are consistent with Bovill and Bulley’s levels of student participation. Under certain conditions, teachers are willing to co-create and reach the highest levels of student participation.

Introduction

Active student participation in improving medical education is of growing interest (e.g., ASPIRE Initiative Citation2012; Fujikawa et al. Citation2015; Peters et al. Citation2018; Martens, Meeuwissen, et al. Citation2019). Students can be actively involved in various ways, for instance by serving as student representative on advisory bodies or course design teams (Duffy and O’Neill Citation2003; Seale Citation2010; Bovill et al. Citation2011). Student participation has the potential to develop into a student-staff partnership (Delpish et al. Citation2010; Bovill and Bulley Citation2011). This can be defined as ‘a collaborative, reciprocal process through which all participants have the opportunity to contribute equally, although not necessarily in the same ways, to curricular or pedagogical conceptualization, decision making, implementation, investigation or analysis’ (Cook‐Sather et al. Citation2014, p. 6–7). Evidence suggests that extensive collaboration between teachers and students in designing or redesigning teaching activities can further improve the quality of the instructional design and the resulting learning environment (Delpish et al. Citation2010; Könings et al. Citation2014). Student-staff partnerships create a context in which students and teachers each add their unique perspective on courses and share responsibility for teaching and learning (Dieter Citation2008; Cook‐Sather et al. Citation2014). When teachers and students have different conceptions of their roles, however, intensive collaboration may require considerable effort (Bovill et al. Citation2011).

Practice points

Teachers’ conceptions of student-staff partnerships were three: Teachers teach and students study; teachers teach and value students’ feedback; and teachers and students co-create teaching and learning.

According to teachers, to reach co-creation, teachers must be open to involve students and create dialogues; students must be motivated and be able to communicate; the organisation must be supportive; and teachers should have the final say.

A pertinent question worth addressing in this context is: What are teachers and students’ conceptions of student-staff partnerships? Bovill and Bulley (Citation2011) distinguished four levels of student participation, ranging from teachers being in control of decision-making processes, through teachers accepting student feedback to inform their decisions while still being in control, to students having a bit or considerable influence in the design process. Previous research into students’ perspective has shown that students are willing to become involved in these partnerships (Bicket et al. Citation2010; Martens, Spruijt, et al. Citation2019). Among teachers, however, the idea of student-staff partnerships seems to find a less favourable reception (Bovill et al. Citation2016; Matthews et al. Citation2018). Research has demonstrated that teachers face several barriers to active student participation, such as the extra time it takes to involve students, the communication issues that arise, and students’ lack of content expertise making teachers reluctant to empower students (e.g., Bovill et al. Citation2016). However, teachers’ actual conceptions of these student-staff partnerships have hitherto not been fully explored.

The aforementioned evidence leads us to believe that the success of student-staff partnerships is subject to certain conditions. Indeed, research has identified several prerequisites to establishing student-staff partnerships that in students’ view are necessary, which are: Reciprocal respect, commitment of teachers and students, students must feel that they have influence and autonomy, clear communication between teachers and students about what they expect and students must have prior experience in a course (Martens, Spruijt, et al. Citation2019). Reciprocal respect refers to teachers and students treating each other as serious partners who can exchange thoughts equally (e.g., Cook-Sather et al. Citation2014; Brandl et al. Citation2017). Commitment is about teachers and students being willing to endeavour to improve courses (Bendermacher et al. Citation2017). Influence and autonomy go hand in hand, as students must feel that they are able to influence course improvement processes and that they have autonomy in deciding how to contribute (e.g., Healey et al. Citation2014). To meet the communication criterion mutual expectations must be clear (Andrews et al. Citation2013; Martens, Spruijt, et al. Citation2019). And finally, prior experience refers to the belief that students must have experienced a course before they are able to work in partnership to improve it (Martens, Spruijt, et al. Citation2019). Hence, it is clear which conditions must be fulfilled according to students. Although these are important insights, little empirical evidence exists on the prerequisites that teachers deem necessary to render such partnerships effective. The aim of the present study was therefore to investigate teachers’ perceptions of the prerequisites for effective student-staff partnerships.

Student-staff partnerships are not yet common practice. When students and teachers establish a partnership, both parties must redefine their roles and responsibilities (Cook-Sather and Luz Citation2015). Teachers may feel that students lack the knowledge required for equal participation in course design and redesign, a conception that may make it difficult to establish a full partnership (Bovill et al. Citation2011). Hence, before we start implementing student-staff partnerships, it is imperative that we investigate how teachers feel about positioning students as partners in the revision of existing and the creation of innovative teaching practices. The current investigation seeks to answer the following two research questions:

What are teachers’ conceptions of student participation in improving educational quality?

What are teachers’ conceptions of the prerequisites that are necessary to render student-staff partnerships effective and improve educational quality?

Method

Setting

The present qualitative study was set in a problem-based learning (PBL) context. PBL is a student-centred approach to teaching in which students discuss relevant problems in groups of 10 students. A tutor facilitates the discussion, in which students identify learning needs that require attention during self-study. In the group meeting that follows, students discuss what they have learnt (Van Berkel et al. Citation2010).

We conducted this study at the Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences (FHML) of Maastricht University, the Netherlands, focusing on its four 3-year bachelor programmes in Medicine, Health Sciences, Biomedical Sciences and European Public Health. Students participate in the evaluation of courses by filling in end-of-course evaluation questionnaires. After each course, only those students who sit on the student evaluation panel meet once with the course coordinator to discuss the evaluation data and issues that need improvement; these students do not attend the meetings of the course design team. Course coordinators lead course design teams that consist of a multidisciplinary group of teachers including regular teaching staff who are responsible for the design, implementation, evaluation and continuous improvement of a course. In order to become a course coordinator, teachers must hold a PhD degree and a University Teaching Qualification (UTQ), as the UTQ programme pays attention to curriculum design. Although course coordinators can hold an MD degree, they are not required to, nor do they need to be expert at all course contents. Not only are course coordinators involved in the design and general organisation of a course, they also teach: They guide tutorial groups, provide lectures, and are involved in the assessment. In this position, they are the ones who have most contact with students about educational improvement. Course coordinators may choose to collaborate with students in their course design teams, by asking their input on aspects of the course that need improvement. Maastricht University affords students the opportunity to fill in evaluation questionnaires and to participate in an evaluation panel or course design team.

Participants

Participants were 14 course coordinators of the four aforementioned bachelor programmes. For ease of reference, we will refer to these coordinators as ‘teachers’. From the 37 applications received, we selected participants until we reached theoretical saturation, making sure to achieve an even distribution among the programmes and a variegated range of experience in years. Two teachers whom we approached did not participate in the study since they were on sabbatical. As a result, our sample included four teachers of Biomedical Sciences, four teachers of European Public Health, three teachers of Health Sciences and five teachers of Medicine including the international track. Five teachers were women; nine were men. Eight teachers coordinated a course in the first year, seven in the second year and three teachers coordinated a course in the third year of the curriculum. The participant numbers do not add up to 14, since four teachers coordinated multiple courses. The participants had between 3 and 15 (M = 8.00; SD = 3.97) years’ experience as a teacher when they participated in the interview.

Interview guide

The first author (SM) conducted the interviews, during which she first explained to the teachers what the researchers meant by ‘student-staff partnerships’. Drawing from Cook-Sather et al.’s work (Citation2014), we defined these partnerships as: ‘Students and teachers designing or redesigning education together by contributing equally to decision-making and course improvement processes. In doing so, students and teachers respect each other and are equal partners, although their input may differ’. Questions asked to address research question 1 included: ‘How do you currently involve students in decision-making processes related to educational improvement?’ And to answer research question 2: ‘What do you need to involve students in educational decision-making and improvement processes?’ For the interview guide that contains the interview questions, see Supplementary Appendix A. Additionally, we provided participants with vignettes of definitions of the prerequisites for student-staff partnerships known to date to help explore potential answers to research question 2 (see Supplementary Appendix B). We asked teachers what they needed to meet these criteria.

Procedure

We conducted individual, semi-structured interviews that lasted for approximately 1 h each. Data collection took place over a period of 8 weeks. Teachers provided their consent before the start of the interview. The interviews were recorded and transcribed afterwards. Prior to analysing the data, all participants verified and agreed on the one-page summary of their interview transcript (member check). Three participants made minor modifications to improve clarity, without changing the content. The Ethical Review Board of the Netherlands Association for Medical Education provided ethical approval for this study (Ethical Review Board Number 1035).

Analysis

To capture the underlying mechanisms of teachers’ conceptions of student-staff partnerships, we performed a template analysis of the qualitative data following the six-step procedure described by Brooks et al. (Citation2015). We used this form of thematic analysis as we already had a priori themes in mind. First, SM listened to the audio files, read the transcripts, and made summaries to get to know the data. Secondly, our approach to analysing the data was both inductive and deductive: On the one hand, we used Bovill and Bulley’s (Citation2011) levels of student participation in curriculum design and prerequisites of students’ perspective as a lens to explore the data (deductive), while on the other hand we used teachers’ terminology and words to guide our analysis (inductive). Two authors (SM and JW) independently did the initial coding of one transcript, discussing their findings within 2 h afterwards to reach consensus. Despite differences in the level of detail, codes were similar. We coded all aspects that were relevant to answer the research questions. Thirdly, SM created a hierarchical structure, by clustering codes into themes and identifying relationships among them. Fourthly, SM and JW created and discussed the initial template based on the previous steps. Fifthly, the research team adapted the initial template by restructuring the themes during three discussion sessions. This was an iterative process. All authors critically reviewed the themes and schematic overview. During the discussion meetings, they all saw parts of the data and made changes by re-clustering and relabelling the codes. Finally, the research team developed the final template together. SM applied the final template to the remaining transcripts and verified whether it also fitted all previous transcripts. Throughout this process, we used software programme NVivo to manage the interview data.

Reflexivity

All authors have a background in educational sciences and take an interest in evaluating and improving educational quality. The authors were aware of their positive stance towards student participation and therefore made a deliberate effort to adopt a neutral perspective during data analysis.

Results

In the following, we will first present the themes we constructed from our data, representing teachers’ different conceptions of student-staff partnerships. Next, we describe the prerequisites that, in the eyes of teachers, are necessary for the success of these partnerships. Finally, provides an overview of these conceptions and prerequisites.

Figure 1. An overview of teachers' conceptions of student-staff partnerships and of the prerequisites that are necessary to render co-creation in teaching and learning by teachers and students successful.

Teachers’ conceptions of student-staff partnerships

Based on the interviews we identified three different conceptions of student-staff partnerships, which are: (1) Teachers teach and students study, (2) Teachers teach and value students’ feedback and (3) Teachers and students co-create teaching and learning.

Teachers teach and students study

During the interviews, when we asked teachers to describe their conceptions of student-staff partnerships, a few teachers expressed their concerns about actively involving students in the design of their course. They argued that students could not easily be a substitute for the wealth of experience and knowledge they had gained over the years. More specifically, they felt that students and teachers served different purposes: Students are at university to learn, while teachers are at university to teach. As they believed that improving courses was their core task, they distanced themselves from involving students in course design, both content-wise and pedagogical/didactic-wise. Similarly, involving students in course redesign would have limited effects in their view, since students lack knowledge in this regard. Even student feedback on end-of-course evaluation questionnaires in some cases would not be relevant and should therefore not be taken seriously, these teachers concluded:

The student is here to learn, a teacher is here to, er, to teach. That is the task that has been agreed upon. – Participant 13

They [students] are sometimes in a situation in which their personalities are not fully developed. They are still very young. And they lack certain experience. – Participant 6

Teachers teach and value students’ feedback

The majority of the interviewees perceived a student-staff partnership as a collaboration in which students shared experiences with a course from which teachers could benefit when improving or redesigning the course. A proactive attitude towards the involvement of students in evaluation and openness to student feedback was common among this group. Teachers valued end-of-course evaluations and focus-group sessions in which students evaluated the course. In improving courses, they took students’ advice into account and valued students’ unique contribution for its ability to explain how they had experienced the course. In their view, student-staff partnership was about inviting students at the end of the course to provide feedback and think along. Nevertheless, these teachers were not always aware that they could involve students more than they were doing, for instance in the redesign of a course. When asked if students could also be involved in course redesign, teachers were rather open to this idea and saw added value, although they had not initially mentioned this and had no experience so far. We also observed that teachers related their openness to student participation to their own experiences as students:

Er, I think it is always important to involve students to, er, receive feedback, [to incorporate] them as a sounding board. – Participant 11

In the past, I have always been able to say my piece, when I wanted to. As a student, I also served on the programme committee. And it was also important to me that [they] listened to us and that [they] took me seriously. That feeling of the past that you were taken seriously when you contributed something, I think, yes, that now just passes on to me as a teacher. – Participant 3

Teachers and students co-create teaching and learning

From the interviews, it was clear that some teachers perceived student-We have changed the font type of the figure to the font used by Medical Teacher partnerships as involving students in the design or redesign of courses in collaboration with teachers. By student-staff partnership they meant including students as equal partners in discussions about which aspects of a course needed improvement. In addition, they believed that students and teachers could co-create courses and gave students opportunities to take the initiative. For instance, they developed the initial learning task or assessment, but allowed students to improve this task or assessment using track changes or they even invited students to design a learning task or assessment and then finalised it by providing their own feedback. In their view, involving students in course redesign would not only benefit students and teachers alike, it would also raise the quality of the course. Because of their experience in the course, students could make a unique contribution and introduce new ideas. That is, they could suggest additional content and teaching methodologies as they sometimes read new articles and experienced new educational methods during other courses. They considered this unique contribution to be of key value in educational design or redesign: Courses would become more aligned with students’ preferences and capabilities; and students would likely become more motivated when involved in course redesign, potentially leading to a better understanding and increased competencies. For these reasons, these teachers regarded course co-creation with students as highly beneficial for all parties, both students and teachers:

I think that there are many different educational formats that are more appealing to students and we have ideas about that. However, I do not have all the answers and when students have interesting ideas they have acquired maybe elsewhere, at other educational programmes, heard from friends, acquaintances, I do not know. List them, I think then you have to talk about it. – Participant 7

At a certain point, a student asked me about it [content-related topic] and I knew, I was lost for words. This happened a few years ago and I really did not know it. And then I started researching and it turned out that the student was more up to date than I was. – Participant 5

Teachers’ perceived prerequisites for student-staff partnerships

Teachers indicated that several prerequisites were necessary for the successful establishment of a student-staff partnership in which both parties contribute equally, although each with their unique contribution, to the creation or redesign of a course. The prerequisites mentioned were: (1) Teachers must be open to involve students and be aware of the possibility; (2) Teachers and students must have dialogues to explore their perspectives equally; (3) Students must be motivated and able to communicate in a constructive manner; (4) The organisation must be supportive; and (5) Teachers should have the final say.

Teachers must be open to involve students and be aware of the possibility

According to our participants, teachers must be open to involve students, since openness is a basic attitude for change. When teachers are approachable, students will more readily provide their input. We also observed, however, that not all teachers were aware of the possibility to involve students more deeply in course improvement processes:

Yes, I think that we um. but then you should be open to it and that is one of the prerequisites, it is. A really important prerequisite. If we are, I think that we would be able to come closer to students’ experience. We really do not have a clue I guess. Er, and what their experience looks like. – Participant 3

Teachers and students must have dialogues to explore their perspectives equally

A second prerequisite to which participants attached importance was that students and teachers must have dialogues in which their perspectives are equally appreciated. Teachers explained that when students are treated equally, they will feel more respected and taken seriously. Consequently, they will provide input that is more valuable and advance powerful arguments to reach consensus. In this process, trust is key, as sensitive information such as teacher manuals could be the topic of discussion; teachers must be able to trust that students will not pass the teacher manual on to other students:

No, I mean, we live in 2018 and we do not live in 1956 anymore where a professor was superior to students. No, I think there should be a certain level of equality, that, that would be interesting. – Participant 7

Those are my course design team members. They are considered as equally appreciated partners. And we take decisions by mutual agreement… And sometimes people agree and sometimes people disagree… And that is, it does not matter in this case whether the course design team member is a teacher or a student. Yes, it is discussed, different perspectives are taken into account. In this case, everyone agreed in the end. – Participant 3

Students must be motivated and able to communicate in a constructive manner

Teachers pointed to students being highly motivated and having good communication and collaboration skills as vital prerequisites, because only motivated students could add value to an encounter. They argued that most students were more concerned with assessments than with improving education; their primary aim was to pass their assessments. Teachers believed that if students participate as partners, they must also be motivated to gain experience in higher education, content knowledge and knowledge on how to construct a course. Moreover, students must be able to communicate in a proper way. The need for good communication skills in student-staff partnerships had two reasons: (1) Teachers did not want to become insecure due to students’ input, and (2) teachers wanted to receive and understand students’ input and avoid that students remained silent:

Well yes, I think that it should be an intrinsically motivated student. And a student who is not … yes, it should be a team player. If the student is not a team player, but again yes, er, those are competencies we all focus on. Communicator, collaborator… yes, if he cannot do that, we should not start with it. – Participant 10

Well, you have training sessions that we as teachers could, er, do. They concern course development. Er. I have done the UTQ [University Teaching Qualification] course, for example. So that might be too much for a student, but I think that there are parts … [so] that a student could roughly get the idea: okay, this is how we develop a curriculum, how a course is developed, er. – Participant 12

The organisation must be supportive

A fourth criterion participants raised was that the organisation must facilitate a shift from a ‘student as passive consumer’ conception towards a ‘student as partner’ conception, by promoting changes in systems and culture towards this latter conception. In doing so, it must reward all stakeholders for the effort they put into building student-staff partnerships. For instance, the organisation could recognise students’ help in redesigning education as an extracurricular activity by assigning additional credits; or it could include a remark in students’ diploma, so that students could list the activity in their Curriculum Vitae; or give them a financial compensation. Some teachers were also concerned about the time it would take them to involve students in the design of a course, although other teachers argued that the workload would enhance first as students need support, but would decrease in the long run when less support is needed:

What I would like to indicate is that you have the management, er, they should agree on these kinds of educational improvements, because if they are obstructive. Yes, er then it fails. Guaranteed. – Participant 8

I won’t find any surgeon prepared to do that [student-staff partnerships] like that, for nothing. Because then they will need to block an outpatients’, which will cost them. It means that they will see less patients. I won’t be able to accomplish that. – Participant 4

Teachers should have the final say

Teachers explained that to make partnerships work, only they should have the final say in decision-making and implementation processes. The arguments they put forward were two: First, they must justify to higher management why a course went well (or not) and students cannot take over this role. Secondly, students lack the ability to have a say in such processes because they would only include topics in instructional redesign that are of interest to them instead of the topics needed to become a professional. More specifically, teachers felt that students did not have an overview of the work field and were therefore not informed of the knowledge that is required to become a professional:

You are responsible for it. So that implies making adaptations to a course, but as well, whether you provide a question for assessment, in that case someone can contribute to making such a question, but you are in charge of the final editing. – Participant 2

The course coordinator is responsible … and if … a student [joins] an equally appreciated partnership, but without the responsibility, something does not add up. … Well, because if a student’s input is equal and [his/her ideas] are implemented, but then [this student] is not responsible for it and it goes wrong… The course coordinator takes the rap. That is not possible. – Participant 13

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to enhance our understanding of teachers’ conceptions of student-staff partnership and of its prerequisites for improving educational quality. Teachers’ conceptions differed from believing that students should have limited space in course redesign, through valuing students’ feedback on how to improve courses, to feeling that students and teachers can co-create and redesign courses. Some teachers were of the opinion that teachers and students have different goals within the university, that is, teachers teach, while students learn and seem to lack knowledge. Other teachers felt that teachers teach but should also take students’ feedback into account, and yet others believed that students and teachers can contribute equally to discussions aimed at the co-creation or redesign of education. According to teachers, co-creation seems attainable when both students and teachers are motivated, able to communicate, willing to have dialogues to explore each other’s unique perspectives and learn about each other’s experience, and when teachers have the final say. Finally, they argued that the organisation must support the development of this process.

Our conclusions related to our first research question confirm previous research by Bovill and Bulley (Citation2011) who demonstrated that student participation can take place on multiple levels, from students having hardly any influence to students having significant influence. The present study contributes to this distinction by embedding student participation levels in empirical evidence and by explaining why teachers have these different conceptions of student participation. Teachers who believe that teachers and students serve different purposes in education (the ‘teachers teach and students study’ conception) are likely to exclude students from educational improvement discussions for they expect little from students’ input. By contrast, teachers who feel that students can provide valuable feedback (conception 2) will likely use their feedback to improve education. And finally, teachers who believe in the benefits of students and teachers co-creating education (conception 3) are likely to form partnerships in which students and staff collaborate and learn from each other with the aim to transform and improve education. What is notable is that the conceptions we identified are part of a continuum, as teachers indicated a willingness to change their views. This resonates with the idea put forward by Griffin and Cook (Citation2009) who stated that teachers can switch from using student feedback towards reaching partnerships.

As to our second research question about teachers’ conceptions of the prerequisites for student-staff partnerships, we found that teachers partly shared students’ view exposed by a previous study (Martens, Spruijt, et al. Citation2019) that reciprocal respect and communication are vital to making student-staff partnerships work. That is, teachers believed that students’ input would become more valuable if they respected students and treated them equally. If both students and teachers communicate in a good, respectful manner, both students and teachers would feel safe to share their thoughts. Moreover, both studies concluded that, sadly, students’ role still seems to be restricted to giving advice. Strikingly, our study also found that teachers feel that the final say should be theirs, which conception seems to be at odds with the definition of partnership implying that students and teachers have the opportunity to contribute equally. Consequently, such conception could pose an obstacle to achieving full partnerships. The fact that even the teachers upholding the ‘teachers and students co-create’ conception felt that they should have the final say and responsibility indicates some resistance to student-staff partnerships. A reason could be that teachers feared that empowering students in this way would create a situation in which they had less power than students, a fear that is not justified, however (Cook-Sather et al. Citation2014; Bovill et al. Citation2016; Matthews et al. Citation2018). A question that could be raised is: If teachers and students do not share the final responsibility, can they truly contribute equally?

A note of caution might be that this study reports on the conceptions of course coordinators only. Although we selected these coordinators purposefully because they had the most contact with students who are actively involved, the scope of this study could be extended to include other stakeholders, such as regular teaching staff, managers and regular students. To overcome resistance to implementation, future studies could focus on the role of these stakeholders (Burnes Citation2015). Another limitation of the present study is that it could partly be biased towards more positive conceptions since the study took place in a PBL context in which teachers and students already have a close connection and students are already actively involved in their own education. We therefore welcome replications of our study in other settings. Additionally, we invite researchers to explore the relationship between course evaluation results and teachers’ conceptions of student participation.

Our findings underscore the fact that establishing student-staff partnerships requires effort. Evidence of the prerequisites necessary for successful student-staff partnerships will only be useful when both teachers and students support them. The teachers in our study made several practical suggestions on how to improve such support. For instance, we could let teachers who are already open to active student participation act as role models: If their colleagues witness student-led improvements and how they let students participate, they might appreciate the benefit of student-staff partnerships. Also, we could select new teachers according to not only their knowledge and experience, but also their willingness to involve students in educational improvements. At the same time, we could introduce informal student job interviews such as speed dating to guarantee that students are highly motivated and have good communication skills. Finally, to ensure a supportive organisation, teachers suggested changing the structure by appointing more students to course design teams or letting students design a course or a training. We recommend that targeted interventions be developed to facilitate student-staff partnerships that take not only students’ perspective, but also teachers’ perspective into account. In doing so, the insights from this study into the three conceptions of teachers could serve as an important starting point.

Conclusion

The present study has revealed teachers’ different conceptions of student participation and of the prerequisites that are necessary to render student-staff partnerships successful. Although equality in the final say may be a bridge too far, teachers are willing to co-create courses with students.

Glossary

Student-staff partnership: ‘A collaborative, reciprocal process through which all participants have the opportunity to contribute equally, although not necessarily in the same ways, to curricular or pedagogical conceptualization, decision making, implementation, investigation or analysis’ (Cook-Sather et al. Citation2014, p. 6–7).

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (231.7 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank not only all teachers who participated in this study, but also Angelique van den Heuvel for the language editing.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Samantha E. Martens

Samantha E. Martens, MSc, is a PhD student at the School of Health Professions Education, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, the Netherlands.

Ineke H. A. P. Wolfhagen

Ineke H. A. P. Wolfhagen, PhD, is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, the Netherlands.

Jill R. D. Whittingham

Jill R. D. Whittingham, PhD, is an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, the Netherlands.

Diana H. J. M Dolmans

Diana H. J. M. Dolmans, PhD, is a Professor at the Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, the Netherlands.

References

- Andrews A, Jeffries J, St Aubyn B. 2013. By appointment to Birmingham City University students: promoting student engagement through partnership working. In: Nygaard C, Brand S, Bartholomew P, Millard L, editors. Student engagement: identity, motivation and community. Oxfordshire: Libri Publishing; p. 199–212.

- ASPIRE Initiative: International Association for Medical Education in Europe. 2012. [accessed 2019 Apr 8]. https://www.aspire-to-excellence.org/Areas+of+Excellence/

- Bendermacher GWG, Oude Egbrink MGA, Wolfhagen I, Dolmans D. 2017. Unravelling quality culture in higher education: a realist review. High Educ. 73(1):39–60.

- Bicket M, Misra S, Wright SM, Shochet R. 2010. Medical student engagement and leadership within a new learning community. BMC Med Educ. 10(1):1–6.

- Bovill C, Bulley C. 2011. A model of active student participation in curriculum design-exploring desirability and possibility. In: Rust C, editor. Improving Student Learning (18) Global theories and local practices: institutional, disciplinary and cultural variations. Oxford: The Oxford Centre for Staff and Educational Development; p. 176–188.

- Bovill C, Cook-Sather A, Felten P. 2011. Students as co-creators of teaching approaches, course design, and curricula: implications for academic developers. Int J Acad Devel. 16(2):133–145.

- Bovill C, Cook-Sather A, Felten P, Millard L, Moore-Cherry N. 2016. Addressing potential challenges in co-creating learning and teaching: overcoming resistance, navigating institutional norms and ensuring inclusivity in student–staff partnerships. High Educ. 71(2):195–208.

- Brandl K, Mandel J, Winegarden B. 2017. Student evaluation team focus groups increase students’ satisfaction with the overall course evaluation process. Med Educ. 51(2):215–227.

- Brooks J, McCluskey S, Turley E, King N. 2015. The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qual Res Psychol. 12(2):202–222.

- Burnes B. 2015. Understanding resistance to change – building on Coch and French. J Change Manag. 15(2):92–116.

- Cook-Sather A. 2014. Multiplying perspectives and improving practice: what can happen when undergraduate students collaborate with college faculty to explore teaching and learning. Instr Sci. 42(1):31–46.

- Cook‐Sather A, Bovill C, Felten P. 2014. Engaging students as partners in learning and teaching: a guide for faculty. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass.

- Cook-Sather A, Luz A. 2015. Greater engagement in and responsibility for learning: what happens when students cross the threshold of student-faculty partnership. High Educ Res Dev. 34(6):1097–1109.

- Delpish A, Darby A, Holmes A, Knight-McKenna M, Mihans R, King C, Felten P. 2010. Equalizing voices: student-faculty partnership in course design. In Werder C, Otis M, editors. Engaging student voices: in the study of teaching and learning. Sterling (VA): Stylus Publishing; p. 96–114.

- Dieter PE. 2008. Quality management of medical education at the Carl Gustav Carus Faculty of Medicine, University of Technology Dresden, Germany. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 37(12):1038–1040.

- Duffy KA, O’Neill P A. 2003. Involving medical students in staff development activities. Med Teach. 25(2):191–194.

- Fujikawa H, Wong J, Kurihara H, Kitamura K, Nishigori H. 2015. Why do students participate in medical education? Clin Teach. 12(1):46–49.

- Griffin A, Cook V. 2009. Acting on evaluation: twelve tips from a national conference on student evaluations. Med Teach. 31(2):101–104.

- Healey M, Flint A, Harrington K. 2014. Engagement through partnership: students as partners in learning and teaching in higher education. York: The Higher Education Academy. https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/resources/engagement_through_partnership.pdf.

- Könings KD, Seidel T, Van Merriënboer J. 2014. Participatory design of learning environments: Integrating perspectives of students, teachers, and designers. Instr Sci. 42(1):1–9.

- Martens SE, Meeuwissen SNE, Dolmans D, Bovill C, Könings KD. 2019. Student participation in the design of learning and teaching: Disentangling the terminology and approaches. Med Teach. 41(10):1203–1205.

- Martens SE, Spruijt A, Wolfhagen I, Whittingham JRD, Dolmans D. 2019. A students’ take on student-staff partnerships: experiences and preferences. Assess Eval Higher Educ. 44(6):910–919.

- Matthews KE, Dwyer A, Hine L, Turner J. 2018. Conceptions of students as partners. High Educ. 76(6):957–971.

- Peters H, Zdravkovic M, João Costa M, Celenza A, Ghias K, Klamen D, Weggemans M. 2018. Twelve tips for enhancing student engagement. Med Teach. 41:632–637.

- Seale J. 2010. Doing student voice work in higher education: an exploration of the value of participatory methods. Brit Educ Res J. 36(6):995–1015.

- Van Berkel H, Scherpbier A, Hillen H, Van der Vleuten C. 2010. Lessons from problem-based learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.