Abstract

A number of planetary boundaries, including climate change as a result of greenhouse gas emissions, has already been exceeded. This situation has deleterious consequences for public health. Paradoxically, 4.4% of these emissions are attributable to the healthcare sector. These problems have not been sufficiently acknowledged in health professions curricula. This paper addresses two main issues, humanistic learning and the application of knowledge acquisition to clinical practice. Humanistic learning principles can be used to emphasize learner-centered approaches, including knowledge acquisition and reflection to increase self-awareness. Applying humanistic principles in everyday life and clinical practice can encourage stewardship, assisting students to become agents for change. In terms of knowledge and skills application to clinical practice, an overview of varied and novel approaches of how sustainable education can be integrated at different stages of training across several health care professions is provided. The Health and Environment Adaptive Response Taskforce (HEART) platform as an example of creating empowered learners, the NurSusTOOLKIT, a multi-disciplinary collaboration offering free adaptable educational resources for educators and the Greener Anaesthesia and Sustainability Project (GASP), an example of bridging the transition to clinical practice, are described.

Introduction

A staggering 4.4% of global greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) are attributable to healthcare (Karliner et al. Citation2019). Scientists are in agreement that not only are we experiencing a climate crisis, but it is accelerating faster than expected and is more severe than anticipated, with a number of planetary boundaries already exceeded (Rockström et al. Citation2009; Steffen et al. Citation2015; Raworth Citation2017; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Citation2019; Laybourn-Langton et al. Citation2019; Ripple et al. Citation2019). The resulting destabilization has led to extensive ecosystem disruption and air, water and soil pollution, ‘threatening natural ecosystems and the fate of humanity’ (Ripple et al. Citation2019). To continue as usual will result in increased and longer-lasting heat waves, floods, storms, and emerging infectious diseases and an increased risk of non-communicable diseases, affecting the health of all age groups and posing major challenges to healthcare systems (Frumkin and Haines Citation2019; Watts et al. Citation2019).

Practice points

Early introduction and integration of content in the curriculum emphasizes its importance and its relationship with professional identity.

Adapting information to the local and real-world context will provide relevance.

Supporting intrinsic motivation and student engagement through humanistic principles can lead to student initiatives and empowerment.

Learners are more likely to challenge unsustainable practices in the work environment after participating in scenario-based learning.

Integrating sustainable health care into health professions curricula is a key action necessary to raise awareness of how the many activities of health care provision, e.g. procurement, high energy and water demands and large volumes of generated waste, lead to GHG emissions. Practical advice exists in terms of how and when integration can happen (IFMSA Citation2019; Lopez-Medina et al. Citation2019; Tun Citation2019; Walpole et al. Citation2019; Schwerdtle et al. Citation2020), but there are a number of barriers. These barriers include a perception that sustainability is not relevant to health care (Richardson et al. Citation2014), a lack of educator expertise (Richardson et al. Citation2016; Tun Citation2019), the challenge of including yet another topic within what are currently crowded curricula and the lack of existing assessment approaches (Tun Citation2019).

This article provides a conceptualized process of education for sustainable health care beginning with knowledge acquisition and reflection in the university environment. Various theories and methods are discussed, and, using international examples, an overview of varied and novel approaches and practical examples of how integration is occurring at different stages of training across several health care professions is provided. A learner-centered approach highlighting the development of self-awareness and environmental stewardship is described.

Pedagogical considerations

Learning theory

Humanistic education principles are well suited to educate students about unsustainable human lifestyles and its consequences to human health and well-being as the principles are premised on the idea of respect for human rights, including the right for learners to express their own opinions and values. Based on Maslow’s (Citation1943) notion of self-actualization, the educator’s role in the perspective of humanism is that of a facilitator to help the student actualize inner drive for growth and development where the learner’s interest and development are central to the learning process (Firdaus and Mariyat Citation2017). Attributes can be encouraged using these principles which enables educators to be more effective in supporting learners to develop rationality, autonomy, creativity and a concern for humanity as well as team work, critical thinking and problem-solving skills and will help empower students to become agents for change (Veugelers Citation2011; Chen and Schmidtke Citation2017; Colonna Citation2020).

Humanistic principles are therefore best placed to assist learners not only reflect on and understand their activities as they relate to sustainability, but also to transform them into agents for change so that they can contribute to mitigating the problems arising from unsustainable human activities. Such transformed practitioners are then able to provide sustainable healthcare that ‘focuses on the improvement of health and better delivery of healthcare, rather than late intervention in disease, with resulting benefits to patients and to the environment on which human health depends, thus serving to provide high quality healthcare now without compromising the ability to meet the health needs of the future’ (Tun Citation2019, p. 1168).

Acquisition of foundational knowledge

Based on the humanistic principles described above, the first step in transforming health profession learners into agents for change is to support them to acquire core foundational knowledge and develop key skills and capabilities. These capabilities and knowledge include:

A deep understanding of global issues including environmental sustainability and universal values such as justice, respect for all humanity and equality;

Critical thinking skills;

Social skills such as empathy and conflict resolution;

Responsible behavior (World Education Forum Citation2015).

Development of self-awareness

In addition to the foundational knowledge, education based on humanistic principles would mean facilitating the development of self-knowledge including an awareness of their natural environment and how they relate to that environment (Colonna Citation2020) by engaging in the following activities:

Self-auditing through reflection on their position in the natural environment and their feelings about how they relate to that environment;

Immersion in the natural environment to experience ‘self’ as part of the whole or to acquire an ‘embodied’ knowledge of that environment;

Connection with communities whose culture, spirituality, health and well-being are symbiotically connected to all elements of the natural environment.

To facilitate such self-exploration, reflection exercises such as those developed by the World Federation of Occupational Therapists (WFOT Citation2018, p. 20) can be used as learning activities. The WFOT Sustainability Principles (Box 1) illustrate questions that could be used to guide students in reflecting on their knowledge of sustainability content, their skills in working with service recipients to help address problems related to lack of sustainability, and what they need to learn in order to be more proficient in addressing sustainability concepts.

Application: case studies

To illustrate how sustainability can be integrated into the various health professions curricula at different levels of education, three case studies are presented. The first case study demonstrates how intrinsic motivation and learner engagement and empowerment can be a catalyst for change. The second case study, a collaboration between four European universities, describes innovative teaching and learning approaches and materials based on sustainability values and concepts, evidence, professional relevance and expertise from professionals and students. The final case study describes how clinicians can actively support students to participate in sustainable health care projects and advocacy work, bridging learning, and professional practice.

Case study 1: medical student empowerment

Canadian Federation of Medical Students’ Health and Environment Adaptive Response Taskforce (CFMS HEART): evaluating planetary health integration

Available at: https://www.cfms.org/what-we-do/global-health/heart-competencies

In response to growing student interest and concern, the Canadian Federation of Medical Students launched the Health and Environment Adaptive Response Taskforce (HEART) in 2016 with a key goal to develop core competencies among students in planetary health promotion. Evaluation of 17 medical schools indicated varied incorporation of content on sustainability in curricula ranging from brief discussion of the health impacts of climate change in lectures to case studies or research (CFMS HEART Citation2020; Hackett et al. Citation2020). Presentation of content to students included:

Lectures: Four schools created new lectures on climate change or planetary health, while nine covered the content through pre-existing environmental and occupational health lectures.

Cases: Three schools had dedicated case-based (individual patients or communities) planetary health learning activities including a session on climate change, while two schools incorporated content into existing case-based assignments.

Community-based learning or research projects: Eight schools offered locally relevant planetary health electives. The HEART evaluation, however, revealed that in some cases, there was a lack of student supervisors with the relevant expertise (CFMS HEART Citation2020).

The HEART survey revealed considerable interest in learning about sustainability, resulting in some schools encouraging discussion between students and faculty and a Family Medicine Director asking HEART students how planetary health and climate change could be incorporated into mandatory clinical rotations. Nine schools (53% of surveyed schools) had active student groups or positions within student governance focusing on planetary health. Global health student groups at three other schools organized extracurricular events such as lectures, film screenings, and social media campaigns to raise awareness about the relationship between the natural environment and health.

Case study 2: nursing resources

NurSusTOOLKIT: the Sustainability Literacy and Competency (SLC) Framework

Available at: http://nursus.eu

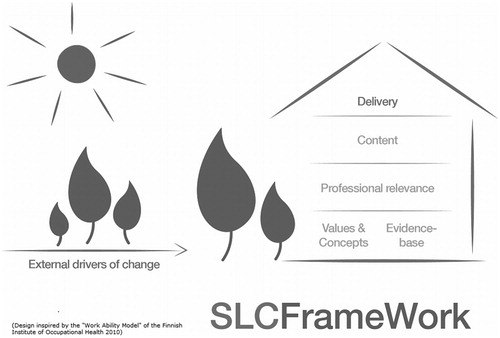

The Erasmus-funded European NurSusTOOLKIT project was developed to provide free, online, evidence-based SLC resources in nursing education. Between September 2014 and August 2017, specialists from four universities – Plymouth (UK), Maastricht (Netherlands), Jaen (Spain), and Esslingen (Germany) – collaborated to develop an evidence-based resource repository for nurse educators that culminated in a SLC-framework, based on Tempel et al. (Citation2015) ‘house of workability’ model (). The dimensions of the SLC-framework are depicted in the form of a house, with the external drivers of change representing its surrounding environment. These drivers of change can range from professional and academic developments that support and influence the SLC-framework over time, to risks or barriers to integration and teaching of SLC content in the nursing curriculum. The first floor comprises sustainability values and concepts and an evidence base. This provides the SLC-Framework with a strong foundation, supporting the other concepts on the floors above. The second floor comprises professional relevance, with the third floor containing the content, 60 topics in five themes:

Underpinning concepts: sustainability and health;

Providing environmentally sustainable health care;

Relationships between health and the environment;

Healthy (sustainable) communities, and,

Social and policy context.

The fourth and top floor is the repository for the resources. For each topic, there is a Description of Materials, Teachers’ Guide, Lecture Slides, Lecture Notes, Interactive Activities, and References and Resources. The Interactive Activities range from quizzes to scenario-based sessions. As the resources and materials have been sourced in Creative Commons, they are free and can be reused or individually adapted, shortened or supplemented as required. The NurSusTOOLKIT has also been used in paramedic training and for accounting students (Richardson et al. Citation2016; Mukonoweshuro et al. Citation2018). Based on a recent audit by the NurSus administrators (personal correspondence), the NurSusTOOLKIT is currently being used by over 500 registered participants in 16 countries, including Australia, the USA, and Canada.

Case study 3: clinicians bridging learning-professional practice

GASP – Greener Anaesthesia & Sustainability Project

Available at: www.gaspanaesthesia.com

In 2018, a multidisciplinary group of about 25 health care professionals working to reduce the environmental impact of healthcare in the UK founded GASP. Current projects running across the UK under GASP include exploring ways of reducing the environmental footprint from anesthetic gases, reduction of energy use in theatres, recycling of medical PVC waste, and streamlining waste streams. In 2019, the GASP Group started the Medical School Sustainability Roadshow, conducting workshops to equip and empower students to effectively participate in sustainable health care projects and advocacy work. Through the network, interested students are connected with clinicians at sites that are open to advancing sustainable health care practice. The network also runs local and national educational sessions for doctors, nurses, and other health professionals.

Conclusions

The purpose of this article was to outline possible tools and pedagogical approaches to prepare health professional students for their future roles, as healthcare transitions to more environmentally sustainable practice. Evidence exists of the importance, the how and the where of embedding sustainability, climate change and health into curricula and also the topics to be included. Some professional bodies, e.g. the International Council of Nurses (ICN Citation2018) and the General Medical Council (GMC Citation2018) support integrating environmental sustainability into health professions curricula.

Not only does sustainable health care need to be included in the curriculum but its application in everyday life and clinical practice has to be facilitated. This begins at university where students learn about the relationship between sustainability, global environmental changes and health and is transferred to clinical practice. This paper highlights that no one solution, but rather a mix of approaches and teaching methods can be applied to develop sustainability awareness in health profession students. By involving students, listening to their concerns, encouraging self-awareness and motivation, students can be encouraged to take ownership which can result in learner empowerment and learner-driven change. Our examples demonstrate that many students both enjoy and are keen to apply their learning and are driving this change, e.g. HEART, GASP, and NurSus. There is, however, much that still needs to be done but the window of opportunity is closing. The world is already facing numerous environmental crises, such as a changing climate, biodiversity loss, and mass deforestation. Educating current health profession students to practice sustainably is therefore a necessity which cannot be delayed.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Norma Huss

Norma Huss, M.N., Dr. rer.med., Dip. N., R.G.N., is professor of Nursing and Student Dean, Hochschule Esslingen, Germany. She led the German team in the EU-funded project on health and sustainability education. Currently, she is working with health care providers to find solutions for practice which support sustainability awareness.

Moses N. Ikiugu

Moses N. Ikiugu, PhD, OTR/L, FAOTA, is professor and director of research, Occupational Therapy Department, University of South Dakota, USA. He leads the WFOT Sustainability project team which published the WFOT Position Statement on sustainability and later the guiding principles for incorporation of sustainability in occupational therapy education, practice and research.

Finola Hackett

Finola Hackett, MD, is a resident physician in rural family medicine at the University of Calgary, Canada. She has served as Chair (2017–2019) of the Canadian Federation of Medical Students' Health and Environment Adaptive Response Task force (CFMS HEART).

Perry E. Sheffield

Perry E. Sheffield, MD, MPH, is a pediatrician and faculty member at the Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai, New York City, USA, where she leads the Climate Change Curriculum Infusion Project (CCCIP) initiative. She is the Deputy Director of the US Federal Region 2 Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Unit and serves as the Mount Sinai liaison for the Global Consortium on Climate and Health Education.

Natasha Palipane

Natasha Palipane, MBBS, BSc, is a specialty doctor in palliative medicine currently working in Chelmsford, UK. She is the Education and Development Lead for GASP and is currently undertaking a MSc in Public Health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Jonathan Groome

Jonathan Groome, MBBS, BSc, FRCA, is an anesthetic registrar from Barts and the London School of Anesthesia. In 2018, he founded GASP – Greener Anaesthesia & Sustainability Project, a multidisciplinary group working to reduce the environmental impact of health care.

References

- [CFMS HEART] Health and Environment Adaptive Response Task Force. 2020. National report on planetary health education 2019; [accessed 2020 May 24]. https://www.cfms.org/files/HEART/CFMS%20HEART%20REPORT%20Final.pdf.

- Chen P, Schmidtke C. 2017. Humanistic elements in the educational practice at a United States Sub-Baccalaureate Technical College. Int J Res Vocation Educ Train. 4(2):117–145.

- Colonna A. 2020. Creating communities of knowledge and connecting to landscape. In: United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization Chairs, editors. Humanistic futures of learning: perspectives from UNESCO Chairs and UNITWIN Networks. Paris, France: UNESCO; p. 16–20.

- Firdaus FA, Mariyat A. 2017. Humanistic approach in education according to Paulo Freire. At-Ta’dib. 12(2):25–48.

- Frumkin H, Haines A. 2019. Global environmental change and noncommunicable disease risks. Annu Rev Public Health. 40(1):261–282.

- General Medical Council. 2018. Outcomes for graduates 2018. London: GMC.

- Hackett F, Got T, Kitching GT, MacQueen K, Cohen A. 2020. Training Canadian doctors for the health challenges of climate change. Lancet Planet Health. 4(1):E2–E3.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2019. Climate change and land. IPCC.

- [ICN] International Council of Nurses. 2018. Position statement on nurses, climate change and health; [accessed 2020 Jan 19]. https://www.icn.ch/sites/default/files/inline-files/ICN%20PS%20Nurses%252c%20climate%20change%20and%20health%20FINAL%20.pdf.

- [IFMSA] International Federation of Medical Students’ Associations. 2019. Medical students for SDGs. 1029; [accessed 2020 Apr 30]. https://issuu.com/ifmsa/docs/medical_students_for_sdgs_vf.

- Karliner J, Slotterback S, Boyd R, Ashby R, Steele K. 2019. Healthcare’s climate footprint. Verfügbar unter; [accessed 2020 Apr 4]. https://noharm-global.org/sites/default/files/documents-files/5961/HealthCaresClimateFootprint_092319.pdf.

- Laybourn-Langton L, Rankin L, Baxter D. 2019. This is a crisis: facing up to the age of environmental breakdown. IPPR. https://www.ippr.org/files/2019-11/this-is-a-crisis-feb19.pdf.

- Lopez-Medina IM, Álvarez-Nieto C, Grose J, Elsbernd A, Huss N, Huynen M, Richardson J. 2019. Competencies on environmental health and pedagogical approaches in the nursing curriculum: a systematic review of the literature. Nurse Educ Pract. 37:1–8.

- Maslow AH. 1943. A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 50(4):370–396.

- Mukonoweshuro R, Richardson J, Grose J, Venancio T, Su C. 2018. Changing accounting undergraduates’ attitudes towards sustainability and climate change through using a sustainability scenario-based intervention within curriculum to enhance employability attributes. Int J Business Res. 18(4):81–90.

- Raworth K. 2017. A doughnut for the anthropocene: humanity’s compass in the 21st century. Lancet Planet Health. 1(2):e48–e49.

- Richardson J, Grose J, Doman M, Kelsey J. 2014. The use of evidence-informed sustainability scenarios in the nursing curriculum: development and evaluation of teaching methods. Nurse Educ Today. 34(4):490–493.

- Richardson J, Heidenreich T, Álvarez-Nieto C, Fasseur F, Grose J, Huss N, Huynen M, López-Medina IM, Schweizer A. 2016. Including sustainability issues in nurse education: a comparative study of first year student nurses' attitudes in four European countries. Nurse Educ Today. 37:15–20.

- Richardson J, Allum P, Grose J. 2016. Changing undergraduate paramedic students’ attitudes towards sustainability and climate change. J Paramedic Pract. 8(3):130–136.

- Ripple WJ, Wolf C, Newsome TM, Barnard P, Moomaw WR. 2019. World scientists’ warning of a climate emergency. BioScience [Internet]; [accessed 2020 Jul 1]; biz088. https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/advance-article/doi/10.1093/biosci/biz088/5610806.

- Rockström J, Steffen W, Noone K, Persson Å, Chapin FS, Lambin EF, Lenton TM, Scheffer M, Folke C, Schellnhuber HJ, et al. 2009. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature. 461(7263):472–475.

- Schwerdtle PN, Maxwell J, Horton G, Bonnamy J. 2020. 12 tips for teaching environmental sustainability to health professionals. Med Teach. 42(2):150–155.

- Steffen W, Richardson K, Rockstrom J, Cornell SE, Fetzer I, Bennett EM, Biggs R, Carpenter SR, de Vries W, de Wit CA, et al. 2015. Sustainability. Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a changing planet. Science. 347(6223):1259855.

- Tempel J, Ilmarinen J, Giesert M. 2015. Arbeitsleben 2025: das Haus der Arbeitsfähigkeit im Unternehmen bauen. 2nd ed. Hamburg: VSA-Verl.

- Tun S. 2019. Fulfilling a new obligation: teaching and learning of sustainable healthcare in the medical education curriculum. Med Teach. 41(10):1168–1177.

- Veugelers W. 2011. Introduction: linking autonomy and humanity. In: Veugelers W, editor. Education and humanism: linking autonomy and humanity. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers; p. 1–7.

- Walpole SC, Barna S, Richardson J, Rother H-A. 2019. Sustainable healthcare education: integrating planetary health into clinical education. Lancet Planet Health. 3(1):e6–e7.

- Watts N, Amann M, Arnell N, Ayeb-Karlsson S, Belesova K, Boykoff M, Byass P, Cai W, Campbell-Lendrum D, Capstick S, et al. 2019. The 2019 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: ensuring that the health of a child born today is not defined by a changing climate. Lancet. 394(10211):1836–1878.

- World Education Forum. 2015. Education 2030: Luncheon declaration and framework for action for the implementation of sustainable development goal 4. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization; [accessed 2020 May 1]. https://en.unesco.org/themes/education/.

- [WFOT] World Federation of Occupational Therapists, Shann S, Ikiugu MN, Whittaker B, Pollard N, Kahlin I, Hudson M, Galvaan R, Roschnik R, Aoyama M. 2018. Sustainability matters: guiding principles for sustainability in occupational therapy practice, education and scholarship; [accessed 2020 Jun 15]. https://www.wfot.org/resources/wfot-sustainability-guiding-principles.