Abstract

Background

Single-best answer questions (SBAQs) are common but are susceptible to cueing. Very short answer questions (VSAQs) could be an alternative, and we sought to determine if students’ cognitive processes varied across question types and whether students with different performance levels used different methods for answering questions.

Methods

We undertook a ‘think aloud’ study, interviewing 21 final year medical students at five UK medical schools. Each student described their thought processes and methods used for eight questions of each type. Responses were coded and quantified to determine the relative frequency with which each method was used, denominated on the number of times a method could have been used.

Results

Students were more likely to use analytical reasoning methods (specifically identifying key features) when answering VSAQs. The use of test-taking behaviours was more common for SBAQs; students frequently used the answer options to help them reach an answer. Students acknowledged uncertainty more frequently when answering VSAQs. Analytical reasoning was more commonly used by high-performing students compared with low-performing students.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that VSAQs encourage more authentic clinical reasoning strategies. Differences in cognitive approaches used highlight the need for focused approaches to teaching clinical reasoning and dealing with uncertainty.

Introduction

Single best answer questions (SBAQs) have dominated written medical examinations for many years (Coderre et al. Citation2004; Heist et al. Citation2014) and have several advantages including high internal consistency and ease of marking (Wass et al. Citation2001; Pugh et al. Citation2019). However, SBAQs have been criticised for not being an authentic representation of clinical practice, because candidates may use the cues provided in the answer options to arrive at the correct answer (McCoubrie Citation2004; Raduta Citation2013; Heist et al. Citation2014). The very short answer question (VSAQ) format provides one potential solution to the cueing and lack of authenticity posed by SBAQs. In the VSAQ format, the candidate is still presented with a clinical vignette and lead-in question, however they are required to independently generate a very short answer (of 1–5 words) rather than choosing the correct answer from a list of answer options. Furthermore, the development of a computer-administered VSAQ assessment has allowed for semi-automated, time-efficient and consistent marking, making them a feasible alternative to SBAQs.

Practice points

VSAQs are more likely to promote deep rather than surface learning compared to SBAQs, since students cannot rely on using the answer options to help them.

Students – particularly those at the lower end of the performance distribution - may benefit from training in applying analytical reasoning strategies to clinical problems.

VSAQs need to be written with care to ensure the uncertainty they create is related to the clinical problem rather than the question construction.

Quantitative studies have demonstrated that students’ scores on SBAQs are significantly higher than on comparable VSAQs (Sam et al. Citation2016, Citation2018, Citation2019), which suggests that students can obtain useful information from the provision of answer options in SBAQs, or are able to enhance their scores through guessing. These hypotheses can be explored in qualitative think-aloud studies. Previous work in this area (Coderre et al. Citation2004; Heist et al. Citation2014; Durning et al. Citation2015; Surry et al. Citation2017) has focused on the thought processes used for SBAQs. These studies have consistently shown that students and doctors use both analytical and non-analytical reasoning strategies to answer SBAQs; an approach that aligns with the ‘processes expected in real-world clinical reasoning’ (Surry et al. Citation2017) (p.1075, our emphasis). However, these studies also reveal the use of ‘test-taking’ behaviours that reduce the authenticity of this type of question, such as the deliberate elimination of alternatives. The test-taking behaviours associated with the use of the answer options in SBAQs would simply not be possible with VSAQs. As VSAQs are a novel question format in medical education, there is a dearth of literature comparing the cognitive approaches to different question formats. A previous study compared the reasoning strategies used to answer clinical questions presented in either short answer or extended matching question formats (Heemskerk et al. Citation2008). The authors report more use of scheme-inductive reasoning (data to diagnosis) for short answer questions and of hypothetico-deductive reasoning for extended matching questions.

In addition to comparing the generic thought processes employed to answer SBAQs with those for VSAQs, it is also useful to investigate whether there are differences in approach between high and low performing students. Previous work has suggested low performers are more likely to exhibit premature closure and less likely to engage in a process of ruling out alternatives when answering SBAQs compared to high performers (Heist et al. Citation2014). Further exploration of these differences could help medical educators understand areas of cognitive error and thus plan more effective teaching.

We undertook a ‘think-aloud’ study of SBAQs and VSAQs with final year medical students in order to explore the following research questions:

Do students use different methods to answer VSAQs compared to SBAQs?

Is there an association between student performance (as measured by scores in a linked quantitative study (Sam et al. Citation2019)) and the methods used to answer questions?

Methods

Our description of the research methods employed in this study is based on the structure suggested by O’Brien et al. (Citation2014) in their Standards for reporting qualitative research.

Qualitative approach

We used a ‘think aloud’ study design, whereby participants are asked to voice the thoughts that occur to them as they complete a task (Hevey Citation2012), in this case answering SBAQs and VSAQs. We subsequently used a content analysis approach and derived our initial content themes from a previous think aloud study undertaken by Surry et al. (Citation2017).

Sampling strategy

Five UK medical schools were selected for this study from the 20 that had participated in a large-scale quantitative study comparing SBAQs and VSAQs in final-year medical students (Sam et al. Citation2019). Schools were selected to give a balance of geography and intake (graduate or non-graduate entry). The students who participated in the quantitative study from these schools were contacted by a study administrator and asked to volunteer to participate in the qualitative study. Up to six students from each school were selected from the pool of volunteers at that school to obtain a balanced sample by gender and VSAQ scores on the assessment used in the earlier quantitative study, and a total of 21 interviews were conducted. All interviews were conducted prior to beginning analysis, so it was not possible to interview until saturation. Two groups of participants, those with scores one standard error of measurement (SEM) above (N = 11) and below (N = 7) the national average VSAQ scores were subsequently identified for research question 2, the analysis by performance. The three participants scoring within one SEM of the national average were excluded from this analysis.

Context

Interviews were conducted in private rooms at each of the five UK medical schools in which this study took place.

Ethical review

This study was approved by the Medical Education Ethics Committee at Imperial College London (Reference MEEC1718-100). All students were provided with information about the study at least 48 hours in advance of the interview day and gave informed written consent to participate on the day of the interview. All interviews were conducted using participant codes rather than names. Participants were given a copy of all the questions used (with answers and explanations).

Data collection methods

Face-to-face interviews were held on one day per school during the period October to December 2019, each conducted by one study investigator (AHS, RWi, CB, RWe) who was not connected to the medical school in question. All interviews were digitally recorded for subsequent transcription. Students were first given up to 16 minutes to complete eight VSAQs under exam conditions, followed by the interview (described below), then up to 12 minutes to complete eight SBAQs, again followed by the interview. Students who were entitled to extra time in their university examinations were given an additional 25% of the time allowed. Like others (Durning et al. Citation2015; Surry et al. Citation2017), we used a retrospective approach (i.e. students answered the questions and then explained their thought processes) to mimic a real-life examination and to avoid the first explanations influencing how subsequent questions were answered.

Data collection instruments

Each student answered eight VSAQs and eight SBAQs, written by members of the research team specifically for this study (Supplement Appendix 1). Four questions (Q1-4) were used in both formats (i.e. five answer options were added to make the question into SBAQ format from the VSAQ format) as the first four VSAQs and last four SBAQs on each student’s paper. A further four pairs of questions were written (Q5-8), which could all be answered in either VSAQ or SBAQ format. The two questions within each pair were ‘matched’ on the basis of specialty and approximate difficulty, as determined subjectively by the question writers. Students answered one question in each pair as a VSAQ and one as an SBAQ, with the version determined at random. The four questions within each block were presented to each student in random order. Students were then asked about their approach to each question in turn using the prompts ‘What steps did you take to answer the question?’ and ‘What were your thoughts during each step?’ Students were asked to explain their thoughts if necessary, for example, why they eliminated certain answers, why they highlighted particular words.

Units of study

The transcripts were coded at question-level i.e., each cognitive method (see below) was marked as present or absent for each student-question combination. In this respect, we quantitised the qualitative data using categorisation, as previously described (Onwuegbuzie and Teddlie Citation2003), to enable us to compare the relative use of each cognitive method for each question format and between the two student performance groups.

Data processing

Interview transcripts were anonymised prior to analysis, such that coding was undertaken blind to each student’s medical school and performance group. Coding was undertaken using NVivo as described below.

Data analysis

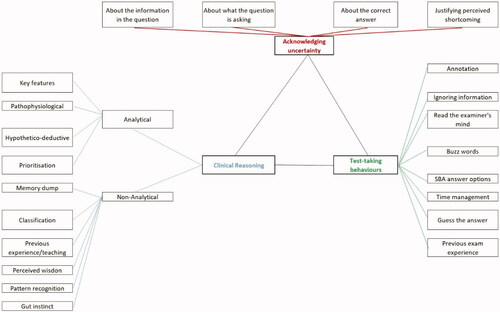

Surry and colleagues (Citation2017) identified four key themes in their work (analytical clinical reasoning, non-analytical clinical reasoning, test-taking behaviours and reactions to the question), and we used these themes as our sensitising framework. Based on these themes, we identified the methods used to answer each question within four main ‘method groups’ (). CB and RWi iteratively developed the first version of the codebook for this study through collaboratively coding one randomly-selected transcript, followed by independent coding and discussion of two further randomly-selected transcripts and development of the second version of the codebook. Independent coding of a further three randomly-selected transcripts was then undertaken by four team members and the results discussed at a team meeting. The resulting revised codebook was applied independently by at least three team members to two further randomly selected transcripts in turn. At this stage, no further changes to the codebook were made, and this was subsequently applied by four team members to code the eighth transcript, with discussion of any discrepancies. All transcripts (including those used in codebook development) were then coded by RWi using the final codebook, which also gives examples of each method as found in the transcripts (Supplement Appendix 2). CB checked the coding of all transcripts, with any discrepancies resolved via discussion with AHS. A coding results table for each student was produced, identifying which methods were present for each question in each format.

To address research question 1 (comparison of methods used), we only used the question pairs (Q5-8) because the pairing provided approximate comparability between the VSAQs and SBAQs. We aggregated data first within each individual method and then within each method group (analytical reasoning, non-analytical reasoning, test-taking behaviours and acknowledging uncertainty). We summed the number of times a method/method group was used across all student-question combinations for each question type and converted this into a relative frequency by dividing the total by the number of times each method/method group could have been used.

To address research question 2 (association between methods and performance), we used the four pairs of questions (Q5-8), plus the additional four items that were answered by all students as VSAQs (Q1-4). We chose not to use the results from the four SBAQs items that students had already answered as a VSAQ (Q1-4), because we found that students’ descriptions of their thought processes for these questions were very brief and often focused on the VSAQ version. We present results for the relative frequency with which each method group was used (calculated as for research question 1).

The results for each research question are presented graphically, using quotes to illustrate key findings.

Results

Participation

Of the 21 students participating in the study, ten (48%) were male. Participant scores for the questions used in this study ranged from 1-7/8 for the VSAQs and 1-8/8 for the SBAQs, with means (SDs) of 4.4 (1.6) for the VSAQs and 5.3 (1.8) for the SBAQs. There was a moderate positive correlation (r = 0.47, p = 0.032) between students’ total scores in the quantitative study (Sam et al. Citation2019) and the think aloud study.

Excluding the four repeated SBAQs, the 21 students described their thought processes for 12 questions each, giving a total number of questions analysed of 252. We identified 22 different methods used to answer the questions within the four method groups: analytical reasoning (4 methods), non-analytical reasoning (6 methods), test-taking behaviours (8 methods) and acknowledging uncertainty (4 methods).

The SBAQ version of each of the paired questions tended to be answered correctly more often than the VSAQ version of the same question, although an individual student only answered a question in one of the two formats. This shows evidence of positive cueing, where the SBA answer options helped students to arrive at the correct answer. There was one clear exception where negative cueing was present, that is, where the SBAQ distractors pulled students away from the correct answer. This was item 7 A, where students were required to diagnose and then identify the first-line medication for mild-moderate ulcerative colitis. Four of the eight students answering the VSAQ version got this question correct, while none of the 13 students answering it as an SBAQ did so.

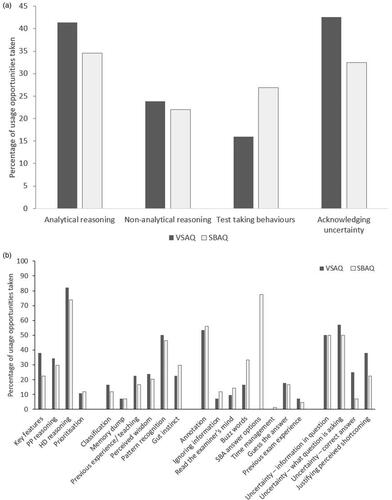

Research question 1: Comparison of methods used to answer VSAQs and SBAQs

shows the total uses of each method group/method as a percentage of the usage opportunities for that method group/method, respectively. We found that students demonstrated analytical reasoning more often when answering VSAQs compared to SBAQs, with 41% of usage opportunities taken when answering VSAQs compared to 35% for SBAQs. The biggest difference between question types within the analytical reasoning methods group was in the use of key features (38%/23% of VSAQ/SBAQ usage opportunities). The most common method overall was hypothetico-deductive reasoning (82%/74% VSAQ/SBAQ usage opportunities). There were similar levels of use of each non-analytical reasoning method across the two question formats. Students used test-taking behaviours more frequently when answering SBAQs, with 16% of usage opportunities taken when answering VSAQs compared with 27% for SBAQs (excluding the method SBA answer options from the denominator for VSAQs). Students made extensive use of SBAQ answer options (77% SBAQ usage opportunities), but students were also twice as likely to use buzz-words when answering SBAQs compared to VSAQs (33%/17% SBAQ/VSAQ usage opportunities). Students acknowledged uncertainty more with VSAQs (43%/32% VSAQ/SBAQ usage opportunities), generally due to differences in expressions of uncertainty as to the correct answer (25%/7% VSAQ/SBAQ usage opportunities).

Figure 2. (a) Total uses of each ‘method group’ by question type, denominated on usage opportunities for the method group. (b) Total uses of each method by question type.

The following three quotes illustrate the benefit students obtain from using the answer options for SBAQs (i.e., cueing) and how these reduce students’ uncertainty regarding the correct answer:

“I went through each specific one and thought to myself, how likely is this? Rule it out immediately or keep it in for now.” Student 1

“But when they’d given me this lovely option of serum electrophoresis that swung me definitely more towards multiple myeloma.” Student 2

“I think, if, if I'd have seen that option in a single best answer scenario, I may have been more confident, but the fact that there, there [sic] is essentially unlimited options between the two, it makes it slightly more tricky.” Student 7

The second of these quotes highlights how the answer options can help students form a diagnosis, as well as helping them arrive at the correct answer, as illustrated in the first quote.

Research question 2: Association between student performance and methods used

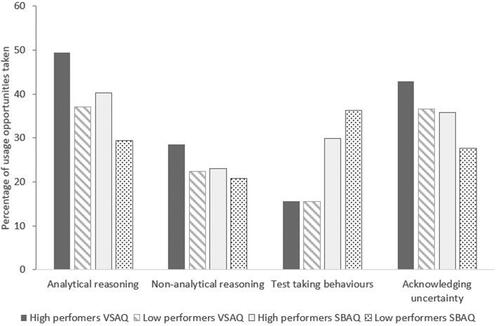

shows the relative frequency of use of each method group comparing results by question type and student performance group. The key differences between the two performance groups are that, compared to the low performing group, the high performing group tended to have greater use of analytical reasoning for both question types, greater use of non-analytical reasoning primarily for VSAQs and slightly less use of test-taking behaviours for SBAQs. The high performing group also acknowledged uncertainty more frequently than the low performing group for both question types, in particular about what the question is asking for VSAQs and about the correct answer for SBAQs.

Qualitative differences in cognitive approaches between high and low performing students are highlighted in the following example. One question asked students to name the most appropriate diagnostic investigation for a patient with features of multiple myeloma. Student 3, from the low performance group, used pattern recognition and gut instinct (and arrives at an incorrect answer), whilst Student 1, from the high-performance group uses hypothetico-deductive and pathophysiological reasoning (and arrives at a correct answer).

“And then I saw that his calcium was high, his creatinine was high, and his haemoglobin was quite low, so I again thought this was a sort of a cancer progressing sort of question. I thought the BPH [benign prostatic hypertrophy] had progressed into like a carc [carcinoma]… like an actual prostate cancer, that’s what I got from the question. So what investigation is going to confirm it and I just put serum PSA.” Student 3, low performing

“White cells are normal so it’s less likely to be infective, potentially less likely to be inflammatory as well. Platelets are normal and so also potentially not a clotting factor or a thrombocytopenic disease or necessarily a potentially an inflammatory disease. … At this point I was thinking that there seems to be some element of renal failure. Is that cause of his back pain and tiredness in the form of renal osteodystrophy? And, you know, his calcium is quite high so that could also be contributing to his tiredness, I think, at that point. So, I was thinking is CKD but with the ESR as well quite high I think that is also a red flag in this picture of back pain, renal failure and tiredness for multiple myeloma.” Student 1, high performing

Both performance groups used the answer options provided in the SBAQs to help them answer the questions – that is, benefitted from cueing - as illustrated by the following quotes:

“It seemed like a picture of gout and specifically the answers are cueing me towards that much more because there is no talk of antibiotics or joint arthroscopy or anything like that for septic arthritis.” Student 1, high performing group

“I knew that he needed imaging, and I did consider a CT thorax as I was reading, but then I saw that answer C specifically said high resolution CT, at which point I thought, Oh, that’s definitely the answer then.” Student 20, low performing group

Discussion

The most common strategy used to answer both VSAQs and SBAQs was analytical reasoning and this was particularly prevalent for VSAQs and amongst high performing students. Analytical reasoning is often used when the answer is not obvious, which is perhaps why it is commonly employed by those with less experience, such as students (Scott Citation2009). Experienced doctors often employ non-analytical reasoning in clinical decision-making (Groopman Citation2008); students may not yet have had sufficient experience to recognise patterns and thus need to use more analytical reasoning strategies. Both analytical and non-analytical reasoning can, however, be prone to error (Scott Citation2009; Audétat et al. Citation2017).

In contrast to Surry et al. (Citation2017), we found that ‘Acknowledging uncertainty’ was a frequently occurring theme, particularly amongst high performing students. In relation to the performance of students in our study, this could reflect a greater depth of analysis of the information in the question and/or a greater level of self-awareness by the high performing students. Overall, the difference between our results and those of Surry and colleagues in relation to uncertainty could be due to a difference in the average experience and/or gender of participants. All of our participants were medical students, while 11/14 of those interviewed by Surry et al. were graduate physicians; we had an almost equal male-female split, while only 3/14 of Surry’s participants were female (with female medical students often less confident than their male counterparts, as noted by Blanch-Hartigan (Citation2011)).

We also found that the use of test-taking behaviours was highest when students answered SBAQs. Such test-taking behaviours, for example, use of buzz-words, are often reflective of superficial rather than deep learning, when an assessment strategy should aim to promote the latter as part of maximising its educational impact. Students reported using the SBAQ answer options in a variety of ways, including to help them understand the question as well as to help them deduce the correct answer, for example by recognising an answer they would not have thought of themselves. By using the answer options as a ‘safety-net’, students may be misleading themselves and others as to what their true level of knowledge would be in a clinical setting.

Our findings add weight to previous quantitative studies that show the benefits of VSAQs over SBAQs (Sam et al. Citation2016, Citation2018; Sam, Fung et al. Citation2019; Sam, Peleva et al. Citation2019; Sam, Westacott et al. Citation2019) for the assessment of applied medical knowledge. This study has also highlighted that care needs to be taken in VSAQ item construction as some of the uncertainty reported in this study related to not understanding what the question was asking (the lead-in), rather than uncertainty about the clinical case or its management. An SBAQ with the answer options removed does not always translate into a well-performing VSAQ.

In addition to providing an authentic method of assessing a candidate’s clinical knowledge, VSAQs also have the ability to enhance feedback to both learners and teachers by better identifying cognitive errors. Furthermore, think-aloud studies such as this help to improve our understanding about how students approach clinical problems and can therefore provide feedback to teachers about methods of thinking, as well as the content of that thinking. Such teaching should include approaches to analytical reasoning, as well as increasing awareness of the potential mechanism for cognitive error (Scott Citation2009; Audétat et al. Citation2017).

Our study has a number of limitations. As with most qualitative research, we did not have a random sample of medical students; those who participated were on average, of slightly higher performance than those participating in our quantitative VSA study. This may be because students were volunteers and high performing students may have more insight into their limitations and hence saw participation as a useful learning opportunity; alternatively, they may have been less afraid of having their weaknesses exposed. For research question 2 in particular, our sample size was low and, only including five medical schools limits the generalisability of our findings. We were unable to directly compare thought processes for the same question in VSAQ and SBAQ formats. Although we had designed the study to show some of the questions in both VSAQ and SBA format, students remembered the VSAQ version too clearly when they answered the SBAQ version and their thought processes were therefore biased. We did not associate methods of answering questions with whether or not the question was answered correctly and this meant we were unable to identify which types of cognitive error resulted in a student getting the wrong answer. While others (Heemskerk et al. Citation2008) have done so, we were concerned that causality could run in either direction. Finally, although written by experienced question writers, we did not have any quantitative data from large-scale administration to evaluate the quality of the questions from a psychometric perspective. As noted above in relation to VSAQ item construction, poor quality questions could jeopardise the results of a think aloud study by falsely increasing the expression of test-taking behaviours as participants question what is being asked of them.

Conclusion

VSAQs were more likely to be answered using analytical reasoning and generated less test-taking behaviours compared with SBAQs. These results suggest that students apply more authentic clinical reasoning strategies when answering VSAQs as opposed to SBAQs. Even in this very small sample of questions, there was evidence of positive cueing with SBAQs, where the answer options helped students arrive at the correct answer resulting in SBAQ scores being higher than VSAQ scores, as has been reported in our previous large-scale study (Sam, Westacott et al. Citation2019). This adds further evidence to suggest that VSAQs are more likely to promote deep rather than surface learning and increase the validity of written assessment.

Glossary

Very Short Answer Question (VSAQ): A format of written assessment where questions are written in a way that requires candidates to provide a written (usually typed) response of 1-5 words.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (32.5 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (24.7 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank the students who participated in this study and their medical schools for facilitating recruitment and logistics on the interview days. Veronica Davids at the MSCAA was instrumental in enabling this study to take place.

Disclosure statement

At the time of the study, AHS, RWe, MG and CB were members of the Board of the MSCAA. The authors declare they have no other conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Amir H. Sam

Amir Sam, PhD, FRCP, SFHEA, is a consultant physician and endocrinologist at Hammersmith and Charing Cross hospitals. He is Head of Imperial College School of Medicine and Director of the Charing Cross Campus at Imperial College London.

Rebecca Wilson

Rebecca Wilson, MA, MBBS, was a Clinical Education Fellow at Imperial College London at the time this study was undertaken. She is now a GP Trainee.

Rachel Westacott

Rachel Westacott, MBChB, FRCP, is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Birmingham. Her research interests include medical education and assessment.

Mark Gurnell

Mark Gurnell, PhD, MA(MEd), FHEA, FAcadMed, FRCP, is Professor of Clinical Endocrinology at the University of Cambridge. He is clinical lead for adrenal and pituitary services at Addenbrooke's Hospital and the East of England, and is the current chair of the Medical Schools Council Assessment Alliance.

Colin Melville

Colin Melville, FRCA, FRCP, is Medical Director and Director of Education and Standards at the GMC. He has previously held senior leadership roles in medical education at Lancaster Medical School, Warwick Medical School, Hull York Medical School, and North Yorkshire East Coast Foundation School.

Celia A. Brown

Celia Brown, PhD, SFHEA, is an Associate Professor in Quantitative Methods at Warwick Medical School, where she is also Deputy Admissions Lead.

References

- Audétat MC, Laurin S, Dory V, Charlin B, Nendaz M. 2017. Diagnosis and management of clinical reasoning difficulties: Part I. Clinical reasoning supervision and educational diagnosis. Med Teach. 39(8):792–796.

- Blanch-Hartigan D. 2011. Medical students' self-assessment of performance: Results from three meta-analyses. Pt Ed Couns. 84(1):3–9.

- Coderre SP, Harasym P, Mandin H, Fick G. 2004. The impact of two multiple-choice question formats on the problem-solving strategies used by novices and experts. BMC Med Educ. 4(1):23.

- Durning SJ, Dong T, Artino AR, van der Vleuten C, Holmboe E, Schuwirth LJP. 2015. Dual processing theory and expertsʼ reasoning: exploring thinking on national multiple-choice questions. Perspect Med Educ. 4(4):168–175.

- Groopman J. 2008. How doctors think. Boston (MA): Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Heemskerk L, Norman G, Chou S, Mintz M, Mandin H, McLaughlin K. 2008. The effect of question format and task difficulty on reasoning strategies and diagnostic performance in internal medicine residents. Adv in Health Sci Educ. 13(4):453–462.

- Heist BS, Gonzalo JD, Durning S, Torre D, Elnicki DM. 2014. Exploring clinical reasoning strategies and test-taking behaviors during clinical vignette style multiple-choice examinations: a mixed methods study. Jnl Grad Med Ed. 6(4):709–714.

- Hevey D. 2012. Think-aloud methods. In: Salkind NJ editor. Encyclopedia of research design. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications, Inc. p. 1505–1506.

- McCoubrie P. 2004. Improving the fairness of multiple-choice questions: a literature review. Med Teach. 26(8):709–712.

- O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. 2014. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 89(9):1245–1251.

- Onwuegbuzie AJ, Teddlie C. 2003. A framework for analyzing data in mixed methods research. Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research. 2:397–430.

- Pugh D, De Champlain A, Touchie C. 2019. Plus ÇA Change, plus C’Est Pareil: Making a Continued Case for the Use of MCQs in Medical Education. Med Teach. 41(5):569–577.

- Raduta C. 2013. Consequences the extensive use of multiple-choice questions might have on student's reasoning structure. Rom Journ Phys. 58:1363–1380.

- Sam AH, Field AM, Collares CF, van der Vleuten C, Wass WJ, Melville C, Harris J, Meeran K. 2018. Very‐short‐answer questions: reliability, discrimination and acceptability. Med Educ. 52(4):447–455.

- Sam AH, Fung CY, Wilson RK, Peleva E, Kluth DC, Lupton M, Owen DR, Melville C, Meeran K. 2019. Using prescribing very short answer questions to identify sources of medication errors: a prospective study in two UK medical schools. BMJ Open. 9(7):e028863.

- Sam AH, Hameed S, Harris J, Meeran K. 2016. Validity of very short answer versus single best answer questions for undergraduate assessment. BMC Med Educ. 16(1):266.

- Sam AH, Peleva E, Fung CY, Cohen N, Benbow EW, Meeran K. 2019. Very short answer questions: a novel approach to summative assessments in pathology. AMEP. 10:943–948.

- Sam AH, Westacott R, Gurnell M, Wilson R, Meeran K, Brown C. 2019. Comparing single-best-answer and very-short-answer questions for the assessment of applied medical knowledge in 20 UK medical schools: Cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 9(9):e032550.

- Scott IA. 2009. Errors in clinical reasoning: causes and remedial strategies. BMJ. 338(jun08 2):b1860–b1860.

- Surry LT, Torre D, Durning SJ. 2017. Exploring examinee behaviours as validity evidence for multiple‐choice question examinations. Med Educ. 51(10):1075–1085.

- Wass V, Van der Vleuten C, Shatzer J, Jones R. 2001. Assessment of clinical competence. Lancet. 357(9260):945–949.