Abstract

Introduction

In March 2020, UK primary care changed dramatically due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It now has a much greater reliance on triaging, e-consultations, remote consultations, online meetings and less home visits. Re-evaluating the nature and value of learning medicine in primary care has therefore become a priority.

Method

70 final-year medical students placed in 38 GP practices (primary care centres) across the East of England undertook a 5-week clerkship during November 2020. A sample of 10 students and 11 supervising general practitioners from 16 different GP practices were interviewed following the placement. Qualitative analysis was conducted to determine their perceptions regarding the nature and value of learning medicine in primary care now compared with prior to the pandemic.

Results

A variety of models of implementing supervised student consultations were identified. Although contact with patients was felt to be less than pre-pandemic placements, triaging systems appeared to have increased the educational value of each individual student-patient contact. Remote consultations were essential to achieving adequate case-mix and they conferred specific educational benefits. However, depending on how they were supervised, they could have the potential to decrease students’ level of responsibility for patient care.

Conclusions

Undergraduate primary care placements in the post-COVID era can still possess the educationally valuable attributes documented in the pre-pandemic literature. However, this is dependent on specific factors regarding their delivery.

Introduction

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, much has been written and researched regarding the nature and value of undertaking undergraduate medical education in the primary care setting. Medical students based in primary care have been shown to the clerk or examine more patients and learn clinical skills as well or better than in hospital settings (Park et al. Citation2015). Learners perceive that primary care placements afford a valuable opportunity for taking responsibility for managing patient care, seeing a wide range and volume of patients, gaining confidence in clinical skills and decision-making, learning about the socio-cultural context of illness, and receiving detailed individual feedback from supervisors (Park et al. Citation2015; Newbronner et al. Citation2017).

Practice points

The triaging systems implemented in primary care during the pandemic are a powerful tool for selecting the most educationally valuable patient problems for student consultations.

With regards to learning about the socio-cultural context of illness, video consultations may help compensate for having fewer home visits.

Student video consultations appeared to be more successful where a ‘video-first’ approach was used (rather than telephone converting to video mid-consultation).

While it remains important for students to undertake face-to-face consultations in primary care, student telephone consultations in the post-COVID era appear to engender specific educational benefits.

Supervision of student telephone consultations requires careful attention to ensuring students still get sufficient responsibility. Undertaking unobserved consultations and delivering the explanation and planning part of the consultation is key to this.

However, in March 2020 the COVID-19 pandemic necessitated rapid, major changes to the nature and delivery of primary care services in order to limit the spread of contagion (RCGP Citation2020a). For example, UK primary care saw the introduction of total triage (NHSE Citation2020; Greenhalgh and Rosen Citation2021). This engendered a huge shift from face-to-face to remote consulting (Murphy et al. Citation2021), a rapid increase in the use of e-consultations (where patients complete an online questionnaire to give an account of their condition [Banks et al. Citation2018]), and conducting home visits virtually, instead of in person, wherever possible (Mitchell et al. Citation2020; RCGP Citation2020b). Social distancing measures also impacted the amount and nature of informal and formal contact between practice staff. While there may be a partial rebalancing back towards face-to-face contact over time (Iacobucci Citation2021; RCGP Citation2021) these recently adopted ways of organising and delivering primary care are likely to remain commonplace (Sivarajasingam Citation2021; Yaseen Citation2021), or even become enshrined in policy (NHSE Citation2021).

Although these changes may bring benefits, concerns have been voiced that important elements of medical practice could be lost in the ‘retreat from face to face consultation’ (Misselbrook Citation2021). These include the loss of physical examination and therapeutic touch (de Zulueta Citation2020), a reduction in the breadth, quality, and therapeutic potential of the consultation (Hammersley et al. Citation2019; Tuijt et al. Citation2021), and a possible loss of the inductive and relational nature of generalist clinical inquiry due to delivery of a more transactional model of medicine (Misselbrook Citation2021; Reeve Citation2021). New consulting and intellectual skills may also be required on the part of the clinician (Wherton et al. Citation2020; Hammond Citation2021).

Accordingly, these developments have triggered medical student concerns about primary care placements in the post-COVID eraFootnote1: that they may not be able to get sufficient history taking and clinical examination practise and that it may affect their ability to learn holistic practice and understand the socio-cultural context of illness (Berwick and Applebee Citation2021; Shah and Osman Citation2021). Learners have also reported a lack of training and confidence in remote consulting for future practice (Salman et al. Citation2021).

As a result of these changes to primary care, and the concerns from clinicians and students about their possible impact, there is a need to re-evaluate the nature of learning medicine in primary care to understand the educational value of primary care placements in the post-COVID era. In order to address this need, we studied the experience and perceptions of medical students and general practitioners (GPs) shortly after undertaking or supervising final-year clerkships in GP practices at the height of the pandemic.

Method

Theoretical stance

Our method of investigating the nature and value of GP placements transformed by the COVID-19 pandemic was shaped by three theoretical perspectives:

Complexity Theory.

GP practices as ‘complex adaptive systems that can reorganise when close to chaos … via adaptability and innovation’ (Bleakley and Cleland Citation2015)

ii. Activity Theory (Johnston and Dornan Citation2015)

The GP clerkship as an activity system whose objective is the attainment of learning. It is comprised of interconnecting actions (e.g. learning experiences) that are governed by: rules (e.g. minimising contagion), the division of labour (e.g. between learner and teacher), the use of tools (e.g. history taking), and the community (practice team and patients)

iii. Situated Learning Theory (Lave and Wenger Citation1991)

On GP attachment, identity and meanings are developed through belonging to this community of practice (Wenger Citation1999) in which the GP acts as a ‘broker’ enabling and overseeing access(Park et al. Citation2015). Learning is shaped by the community as a whole and occurs through actively participating in practice work with increasing levels of responsibility.

Setting

Between November 2020 and April 2021 final year medical students at the University of Cambridge rotated through four 5-week clerkships, one of which was based in a GP practice. Ordinarily placed in pairs and dispersed across the east of England, students on these clerkships become embedded in the practice team and spend the majority of their week undertaking their own clinics under supervision from a GP, as well as engaging in-home visits, practice team meetings and a limited number of practice-based tutorials.

Ethical approval

Approval was obtained from The University of Cambridge Psychology Research Ethics Committee ref PRE.2020.135.

Sample and data collection

All 70 final-year students who undertook their 5-week final-year GP clerkship from 2nd November to 4th December 2020 were invited to participate in a post-placement interview. All 65 doctors (general practitioners) who supervised this clerkship were also invited.

While there was ethical approval to purposively select students and staff with a range of feedback scores, the numbers of students and doctors volunteering were low to the point that all volunteers were included in the study.

Three researchers undertook the interviews: two students undertaking the penultimate year of their Cambridge medical course (MK and XT) and the academic general practitioner (family physician) with overall responsibility for primary care teaching at Cambridge (RD). Each student interview was undertaken by MK and XT working together. The doctor interviews were undertaken by RD.

The topic guide covered experience and perceptions of undertaking or supervising this clerkship in the post-COVID era with some reference to their pre-COVID placements during the previous academic year. The interview structure was kept sufficiently broad to allow the interviewers to probe and explore insights as they arose during the interviews.

Interviews were conducted and recorded using Zoom. The video element of each recording was immediately deleted and the audio element was uploaded to a professional transcription company. Transcripts were then imported to NVivo 12 for analysis.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis of the data was informed by our theoretical stance and broadly followed the process described by Kiger and Varpio (Citation2020). A detailed account of the analysis process is available in Supplementary Appendix 1.

Results

Interview participants

Twenty-one interviews took place in total: one for each study participant recruited. 10 of the 70 students on the placement and 11 out of the 65 supervising doctors took part in the study. Supplementary Appendix 2 details the dates the interviews took place for each participant as well as whether the doctor went on to supervise the second clerkship (running from 7th December 2020 to 22nd January 2021). One doctor (Doctor 8) only supervised the second clerkship, not the first (see Supplementary Appendix 2). Of the 38 GP practices that delivered the clerkship, 16 (42% of total) were represented in the study.

Results of thematic analysis

Adaptation: different models of delivering the post-COVID primary care placement

A complexity theory perspective enabled us to examine the data for the different approaches taken to delivering the clerkship within the confines and challenges of the pandemic:

The range of activities that took place

Three main types of placement-related activities emerged from the data: consultations, home visits, and meetings.

Student consultations with patients: face-to-face only or combined with remote

Practices appeared to follow one of two different models when providing student consultations: face-to-face consultations only or a mixture of face-to-face and remote consultations.

On the whole, remote student consultations appeared to be mainly using the telephone with the only occasional conversion of these to video. When used in this way, video consulting was often perceived negatively by both students and supervisors due to being time-consuming to arrange, connection issues, poor video quality, or excluding certain patient groups.

There was only one example elicited where video consulting was the main modality used in student-led remote consultations. The supervisor using this approach was extremely positive about how well the method had worked. In this case, all student consultations were initiated using video irrespective of the supervisor, and receptionists appeared to be following a detailed protocol for selecting and preparing patients for student video consultations (‘video first’).

Home visits were rare

The placements discussed by interviewees did not generally involve students undertaking home visits more than once or twice for the whole placement. This is significantly less than would have occurred on a pre-pandemic primary care placement.

Meetings: conducted face-to-face or online

Meetings mentioned by interviewees included tutorials, practice meetings, communal coffee times, and informal conversations. Practices varied in terms of whether their meetings were face-to-face or conducted remotely using applications such as Microsoft Teams.

The range of supervisor involvement in student consultations

A variety of models of supervising student consultations with patients emerged from the interview data. These appeared to involve different levels of supervisor involvement

Independent data gathering was still very common …

Students’ face-to-face consultations generally appeared to be supervised using the approach commonly used for final year student surgeries before the pandemic. This comprised students gathering the history unobserved and then conferring with the supervisor who would then observe or help deliver the explanation and planning part of the consultation.

This level of observation and doctor intervention was commonly replicated in video and telephone consultations. For example, where ‘video first’ student consultations were used, the supervisor would join the video ‘room’ for the explanation and planning part of the consultation only. Similarly, for telephone consultations, there were many examples where students would gather the history unobserved, ring off, confer with a supervisor and then ring the patient back with the supervisor present.

… but telephone consultations can engender a greater degree of supervisor involvement

There were also many examples where the model of supervising student telephone consultations involved a much higher level of supervisor presence or intervention than described above. For example, in at least four interviews, the model described was of supervisors being present for the entirety of telephone consultations. In addition, there were two interviews where the model appeared to be one of an unobserved student gathering the history over the phone followed by conferring with a supervisor who would subsequently call the patient back and deliver the end of the consultation. In one of these two interviews, it appeared these supervisor-delivered call-backs generally occurred without the student present.

A number of reasons for supervisors observing entire student telephone consultations were evident in the data. These included:

A perception that supervising student consultations without being party to the initial conversation was a higher risk for telephone consultations:

“When you go into a room with a physical patient there, the supervising GP can sort of, within a few seconds, get a bit of a feel of how things have been … you’ve got your student giving you the history, while you’re kind of half-eyeing the patient and getting their response to the presentation.” Doctor 1

Fears that ringing off and calling back may adversely impact the patient experience

“…they could have been left to do a surgery and then call back, but actually it feels a bit bitty … for the patient, which, let’s face it, is who it’s about.” Doctor 11

A perception that changes to medical practice since students’ previous (pre-COVID) placements meant they were less prepared and in need of more clinical guidance

“..now there’s a lot more unknown in terms of what’s expected of them … let alone a new skillset of how we practice.” Doctor 9

Different ways of supervisors observing telephone consultations

A range of methods for observing student telephone consultations was described by supervisors. Commonly, this occurred by doctor and student being in the same room (using the telephone on speakerphone or a multiple headset connector). However, two methods of supervisors observing remotely from another consulting room were also described. This was done via internal telephone conferencing functionality or by using a video conferencing platform to dial into a consulting room where the student was talking to the patient on speakerphone.

Production … of learning on the post-COVID primary care placement

An activity theory perspective helped us to interrogate the data for perceptions around the effectiveness of the clerkship for producing learning and the factors contributing to this.

Patient contacts were fewer but more valuable

Quality and quantity of patient exposure were seen by students and supervisors to be important to the educational value of primary care placement. The COVID-19 pandemic was seen to have impacted these factors in a number of ways:

Amount of contact with patients was often felt to be less …

Students and supervisors often expressed the view that changes to primary care due to the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in students having less contact with patients than before the pandemic. This view was particularly held by students and supervisors on placements that limited student consultations to face-to-face (FTF) consultations. Indeed, one such student wished for remote consultations in order to get more patient exposure.

Nevertheless, a number of students mentioned that even if the quantity of interactions with patients was less than on pre-COVID primary care placements, it was still significantly higher than the number available in secondary care placements.

“…because patients were scheduled in to come and see us… you know that you’re going to see about five patients every day, whereas actually on the ward, they might not have been able to manage that.” Student 04

… but the educational value of each contact was felt to be greater (enabled by triage)

Students and supervisors both expressed the view that any reduction in the number of patient contacts for students was compensated to some degree by the fact that the learning opportunity afforded by each interaction between student and patient was greater than pre-COVID.

This appeared to be due to the extensive use of triaging (by phone or e-consultation) which enabled:

intentionally selecting a range/variety of patient presentations,

“we’d know … the nature of the problem and we try and mix it up a bit.” Doctor 8

screening-out administrative-type consultations,

“We can screen out a little bit more… to not give the students just the admin tasks …” Doctor 5

selecting more valuable face-to-face consultations,

“I saw fewer face-to-face patients, but I think they tended to be more interesting patients from a learning perspective.” Student 8

students reading-up on topics related to a patient’s presenting condition before starting a consultation

“…it was helpful in getting us to understand what was …coming through the door. … what do we need to ask, what do we need to worry about.” Student 10

Telephone consultations have specific educational benefits for students

Specific educational benefits of student telephone consultations emerged.

Telephone consultations teach specific intellectual skills (triaging skills)

Students and supervisors perceived telephone consulting as requiring specific important clinical reasoning skills. These appeared to relate to remote triaging and risk assessment skills

“…they’re much more mindful of risk … what’s the worst-case scenario, what could I be missing, having to negotiate whether you see this patient or whether they should just go straight into hospital… So, I think there’s a lot more critical thinking…” Doctor 9

”Being like, oh, actually, I think we need to see you to see how unwell you are…” Student 7

Telephone consultations provide stretch in history-taking skills

Students commonly expressed the view that telephone consultations were valuable for providing stretch in developing consulting skills:

“I think I had almost not really realised that I could perhaps be better at my history taking skills in terms of the questions that I ask. And I think telephone consultation has definitely forced me to think a lot more about that.” Student 1

Telephone consultation skills can increase the efficiency of exposure to patients

Some students also viewed them as a more time-efficient way of gaining valuable clinical experience and learning.

“…you don’t have to bring the patient in, let them sit down, this and that; you just get straight to it.” Student 8

Telephone consultations allow you to make and reflect on your own notes

Students also appreciated the way that telephone consultations enabled them to refer to a ‘cheat sheet’ during the consultation and the way they could formulate their thoughts without a patient in the room before presenting to their supervisor.

“it was quite easy to have this little cheat sheet. When talking to someone” Student 5

“…you can hang up the phone, have a look at all the notes you made and formulate in your mind, because the patient’s not sitting there watching you while you’re doing all of this. So, in terms of learning I think that was more useful in terms of formulating a diagnosis.” Student 9

Telephone consultations improve case-mix, especially to mental health presentations

Mental health presentations tended to use telephone consultations. This had implications for student’s exposure to psychiatric presentations as illustrated by this quote from a student who undertook only face-to-face consultations:

“I didn’t see any psych patients this time, whereas in previous years, I saw a lot.” Student 3 (FTF only)

Sociocultural context of illness: video may help compensate for the loss of visits

Supervisors commonly lamented the educational impact on students of the lack of home visiting experience. However, two supervisors expressed the view that video consultations could help compensate for this by providing access to complex housebound patients and giving insights into patients’ social context.

“…doing the videos, seeing these mums at home in their context, or seeing these elderly patients at home … You do get this snapshot you otherwise wouldn’t have got. And we had a mum on …it was just insanity behind her, there were kids running around and you just got a glimpse of what life was like for her in a way that we wouldn’t have got.” Doctor 4

Learning examination skills: even face-to-face consultations don’t offer what they used-to

Unsurprisingly, a commonly mentioned educational benefit of face-to-face consultations was the potential to practise examination skills. However, interviewees acknowledged that the potential of these consultations during the pandemic was limited by social distancing measures meaning that examination often had to be scanty or, for example with the throat, avoided altogether. Commonly, the implication appeared to be that practising formal full-length patient examinations was important for passing forthcoming final OSCEs.

“I felt that they [examinations] were definitely shorter and more focused. They weren’t as…like, as by the book… COVID had an impact because you didn’t want to be spending too much time doing unnecessary things with a patient, like minimise that contact …” Student 2

Participation … in the community of practice in the post-COVID era

Analysing the data from the communities of practice perspective suggested the following themes:

Belonging: students feel they are as much a part of the team, but supervisors are not so sure

There appeared to be a disconnect in the data between supervisor and student conceptions on the degree to which students felt part of the practice team. Supervisors appeared to feel that students were not so much part of the team as they used to be pre-COVID. The doctors interviewed frequently mentioned the negative effect impact they felt that a move to online practice meetings and social distancing measures had on student visibility, participation, and relationship building within the practice

“…I think the students are just less visible. But then, you know, if you’re having to socially distance …they probably just don’t integrate more with the, kind of, other parts of the team.” Doctor 6

”…we got them to log on to the clinical meeting … but obviously it’s never going to be the same, because when you’re sitting in a room … you have to talk to people you haven’t seen … but when you’re on Zoom you don’t have that chitchat.” Doctor 7

Conversely, all the students interviewed were emphatic that they really felt just as much part of the team as in their pre-COVID primary care placements. Interestingly, the students appeared to have different conceptions of what it meant to be part of the team compared to the supervisors. As illustrated above, for the supervisors this meant the whole practice team seeing and getting to know the students. However, for the students, feeling part of the team appeared to mean getting to do what the doctors do:

”…we were allowed to see patients face-to-face as well, and they gave us scrubs …So you felt very much part of the team and got stuck in …” Student 6

Perhaps the supervisor perspective on the degree of student belonging was more a reflection of what had been lost to the practice rather than what had been lost to the student:

”…but normally, you know, including them in a clinical meeting … that’s usually quite fun. But we’ve lost that. … a general kind of buzz, yeah, a buzz in the practice when there are students around which we all enjoy.” Doctor 1

Feeling responsible for patient care: important and still possible if supervision and space allow

Interviewees commonly expressed that giving final year students a feeling of responsibility for patient care was important to the educational value of the placement. On further analysis, this sense of responsibility for patient care appeared to be linked to:

Delivering the explanation and planning part of the consultation,

“And they’ve quite enjoyed the fact that it’s them delivering the management plan, it’s not the doctor taking over… they’ve been given the responsibility to phone the patient back again.” Doctor 5

being unobserved while consulting

“I think the best thing about the GP placement is that we get to do these independent clinics or phone calls without having direct supervision from the doctor because we can actually act like we would if we were doctors or when we are doctors …” Student 5

and not having another student sitting in on their consultation

“…whereas previously you could rely on your partner to, kind of, pick up the bits that you’ve missed … I had to be very much switched on 100 per cent all the time, and really take responsibility …I felt like I was being given more responsibility as an individual, rather than previously.” Student 4

… which was not always achievable due to COVID-related pressures on space

“…there were less rooms available… So I think COVID definitely had a role to play in …the fact that we had to share rooms.” Student 2

As described earlier in the results, student telephone consultations appeared to have the potential to engender a greater degree of supervisor observation/intervention than student face-to-face consultations. As such, telephone consultations could therefore have the potential to erode this sense of taking responsibility for patient care.

Students did, however, value the fact that having a supervisor present during their consultations enabled useful feedback:

“…we quite often would, halfway through, put the patient on mute and we could have a discussion about what was going well, what needed to be resolved … And because they’re observing what you were saying, they could give you actual direct, constructive feedback which you don’t get when the GP is not in the room.” Student 1

A ‘good’ supervisor far outweighs the effect of COVID-19 pandemic

Overall, students appeared not to perceive that the pandemic was the main factor influencing the educational value of their current placement in comparison to their prior (pre-COVID) primary care placements. Instead, they commonly expressed that whether they had a ‘good’ supervisor was of far greater influence.

Many attributes of ‘good’ supervisors emerged from the data, including selecting sufficient numbers and types of patients, giving feedback, teaching, supporting, and giving responsibility. However, there was one commonly mentioned attribute that appeared to explain why having a ‘good’ supervisor/practice was perceived to far outweigh the effect of the pandemic. This was the ability to work with students to flex and adapt their delivery of the placement according to student needs/wants in what was then a very new primary care landscape:

“… they were very good at asking us about what was working and what wasn’t working and being flexible and taking our comments on board.” Student 3

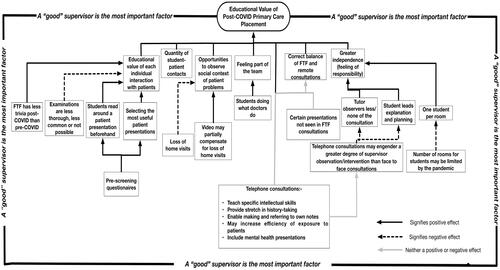

A summary of the results is provided in .

Discussion

Summary of findings

We analysed the data from the perspective of adaptation (of the clerkship to the post-COVID world), production (of learning and the factors influencing this), and participation (of students in the community of practice).

In terms of adaptation, the data revealed a range of different methods and modalities for delivering and supervising student consultations. Video teaching consultations were rare and appeared to work best when a ‘video first’ approach was used.

In terms of the production of learning, supervisors and students felt that telephone consultations had specific educational benefits. Although numbers of student contacts with patients were felt to be less than before the pandemic, the educational value of each patient contact was felt to be greater due to the use of triaging systems for selecting suitable patients. Two supervisors thought student video consultations could provide insights into the socio-cultural aspects of health and illness that may help mitigate the loss of home visits.

In terms of participation, supervisors and students considered it important to the educational value of the placement that students feel a sense of responsibility for patient care. Although interviewees often felt this was still the case, some of the approaches used for supervising telephone consultations had the potential to reduce this. Students all felt as much part of the team as in their previous (pre-pandemic) primary care clerkships and perceived that of far greater impact than the pandemic was whether or not they had a ‘good’ supervisor/practice.

summarises our findings and as such provides guidance on the successful delivery of primary care clerkships in the post-COVID era.

Comparison with existing literature

Prior to the pandemic, the perceived benefits of final-year undergraduate GP clerkships were found to include exposure to a large number and range of patient problems and the opportunity to take responsibility for patient management (Newbronner et al. Citation2017). Our findings suggest that this is commonly still the case. Furthermore, our study adds to the literature by suggesting that telephone consultations are currently essential to achieving a full case-mix but that certain methods of supervising them can erode students’ feeling of responsibility. We found physical space limitations exacerbated by the pandemic can also have a negative impact in this regard. However, the feasibility of students consulting from home has recently been demonstrated (Darnton et al. Citation2021) and perhaps this could help address such space issues.

Medical students have previously voiced fears that the pandemic-related shift to remote consulting may adversely affect their opportunity to practise clinical skills(Berwick and Applebee Citation2021). Our findings provide some reassurance on two fronts. Firstly, they suggest that remote consultations are valuable for learning many clinical skills. Secondly, it appears that if students are undertaking less face-to-face consultations in primary care than they used to, it is likely that these interactions are often of greater educational value than before the pandemic. Our data does however suggest that practising formal, full-length ‘OSCE Style’ clinical examination routines appeared to be more difficult given the pressure during each examination to keep close contact with patients as brief as possible. Hopefully, as vaccination coverage increases, this pressure will recede, and corresponding student concerns may diminish.

Studies conducted prior to COVID (Park et al. Citation2015; Newbronner et al. Citation2017) found that students valued the insights into sociocultural aspects of health and illness provided by primary care placements ‘in particular through seeing patients in their homes and understanding their family circumstances’ (Newbronner et al. Citation2017). Our findings support the validity of published concerns by students about losing this benefit(Berwick and Applebee Citation2021) due to the lack of home visit experience during the pandemic. Hopefully, this trend will reverse as the pandemic eases. In the meantime, our results suggest that video consultations may be able to help compensate for this lack by providing a different way of students ‘seeing patients in their homes.’

A systematic review conducted prior to COVID found the GP supervisor to act as a ‘broker’ of communities of practice (Park et al. Citation2015). Our results support the continued validity of this ‘broker’ model in those students who found having a ‘good’ supervisor to be far more impactful on their learning than the effect of COVID on their placement. Indeed, the role of the ‘broker’ seems even more impactful now given the increased palette of options for delivering student consultations post-COVID. The supervisor’s influence on the type of consultation, the method of supervision, and selection of patients appears to resonate strongly with Park et al.’s description of the broker as ‘constructing the nature of the interactions within the teaching consultation; allowing and overseeing membership …’ (Park et al. Citation2015).

Strengths and weaknesses of study

The clerkship evaluated in this study occurred during November 2020 which was mid-pandemic just as the UK vaccination programme was about to commence. It could therefore be argued that the nature and delivery of primary care are likely to have changed since then, for example with some rebalancing towards face-to-face contact(RCGP Citation2021). However, this time-point was chosen precisely so that the contrast with pre-COVID placements would be most stark and that focusing on this contrast would be a powerful stimulus for eliciting interviewees experiences and perceptions. This approach was vindicated by the quality of data collected. The differences between pre- and post-COVID primary care placements may become less stark over time. However, the themes elicited in our study should still provide a useful starting point for considering the potential benefits and drawbacks of different approaches.

Implications for practice and suggestions for future research

With regards to the implications of our findings, five practice points are presented above and our thematic map () is a useful aid for educators.

In particular, our findings suggest that a lack of any telephone consulting experience could be disadvantageous to students’ learning. However, our findings also suggest that where student telephone consultations are used, the supervision methods used need to maintain students’ sense of responsibility for the consultation, especially in relation to explanation and planning.

This study is to our knowledge the first to chart the nature and value of undergraduate clerkships in the new normal of post-COVID primary care. Further research is required to confirm our findings and to determine the degree to which they persist as post-COVID primary care becomes a more familiar context for learners and teachers.

Glossary

Post-COVID Era: The time period following the commencement of the COVID-19 pandemic which was declared by the World Health Organisation on 11th March 2020. For another example of the term post-COVID to describe this period, see https://www.rcgp.org.uk/-/media/Files/News/2020/general-practice-post-covid-rcgp.

Remote Consultations: Consultations occurring via telephone, internet, or video link. See UK General Medical Council guidance on remote consultations at https://www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-hub/remote-consultations.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (22.4 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Richard Darnton

Richard Darnton is a general practitioner (family physician) and academic with lead responsibility for medical student teaching in primary care at the University of Cambridge.

Maaz Khan

Maaz Khan is a medical student in their penultimate year of the University of Cambridge standard entry course.

Xiu Sheng Tan

Xiu Sheng Tan is a medical student in their penultimate year of the University of Cambridge standard entry course.

Mark Jenkins

Mark Jenkins is an administrator at the University of Cambridge Academic Unit of Primary Care.

Notes

1 We have defined “post-COVID” as the time period after March 2020.

References

- Banks J, Farr M, Salisbury C, Bernard E, Northstone K, Edwards H, Horwood J. 2018. Use of an electronic consultation system in primary care: a qualitative interview study. Br J Gen Pract. 68(666):e1–e8.

- Berwick K-L, Applebee L. 2021. Replacing face-to-face consultations with telephone consultations in general practice and the concerns this causes medical students. Educ Prim Care. 32(1):61.

- Bleakley A, Cleland J. 2015. Sticking with messy realities: how ‘thinking with complexity’ can inform healthcare education research. In: Cleland J, Durniung SJ, editors. Researching medical education. New York (NY): John Wiley & Sons; p. 81–92.

- Darnton R, Lopez T, Anil M, Ferdinand J, Jenkins M. 2021. Medical students consulting from home: a qualitative evaluation of a tool for maintaining student exposure to patients during lockdown. Med Teach. 43(2):160–167.

- de Zulueta P. 2020. Touch matters: COVID-19, physical examination, and 21st century general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 70(701):594–595.

- Greenhalgh T, Rosen R. 2021. Remote by default general practice: must we, should we, dare we? Br J Gen Pract. 71(705):149–150.

- Hammersley V, Donaghy E, Parker R, McNeilly H, Atherton H, Bikker A, Campbell J, McKinstry B. 2019. Comparing the content and quality of video, telephone, and face-to-face consultations: a non-randomised, quasi-experimental, exploratory study in UK primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 69(686):e595–e604.

- Hammond A. 2021. Covid-19 and clinical reasoning—we all became novices once more. BMJ Opinion; [accessed 2021 Jun 25]. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2021/04/12/covid-19-and-clinical-reasoning-we-all-became-novices-once-more/.

- Iacobucci G. 2021. GPs should return to offering face-to-face appointments without prior triage, says NHS. BMJ. 373:n1251.

- Johnston J, Dornan T. 2015. Activity theory: mediating research in medical education. In: Cleland J, Durniung SJ, editors. Researching medical education. New York (NY): John Wiley & Sons; p. 93–104.

- Kiger ME, Varpio L. 2020. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med Teach. 42(8):846–854.

- Lave J, Wenger E. 1991. Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press.

- Misselbrook D. 2021. General practice after COVID-19: an introduction to our special series. Br J Gen Pract. 71(707):265.

- Mitchell S, Hillman S, Rapley D, Gray SDP, Dale J. 2020. GP home visits: essential patient care or disposable relic? Br J Gen Pract. 70(695):306–307.

- Murphy M, Scott LJ, Salisbury C, Turner A, Scott A, Denholm R, Lewis R, Iyer G, Macleod J, Horwood J. 2021. Implementation of remote consulting in UK primary care following the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-methods longitudinal study. Br J Gen Pract. 71(704):e166–e177.

- Newbronner E, Borthwick R, Finn G, Scales M, Pearson D. 2017. Creating better doctors: exploring the value of learning medicine in primary care. Educ Prim Care. 28(4):201–209.

- NHSE. 2020. Advice on how to establish a remote ‘total triage’ model in general practice using online consultations. London (UK): NHS England; [accessed 2021 May]. https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/C0098-total-triage-blueprint-september-2020-v3.pdf.

- NHSE. 2021. 2021/22 priorities and operational planning guidance. London (UK): NHS England; [accessed 2021 May]. https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/2021-22-priorities-and-operational-planning-guidance/.

- Park S, Khan NF, Hampshire M, Knox R, Malpass A, Thomas J, Anagnostelis B, Newman M, Bower P, Rosenthal J, et al. 2015. A BEME systematic review of UK undergraduate medical education in the general practice setting: BEME Guide No. 32. Med Teach. 37(7):611–630.

- RCGP. 2020a. General practice in the post Covid world: challenges and opportunities for general practice. London (UK): Royal College of General Practitioners; [accessed 2021 May]. https://www.rcgp.org.uk/-/media/Files/News/2020/general-practice-post-covid-rcgp.

- RCGP. 2020b. Top tips for GPs caring for care homes. London (UK): Royal College of General Practitioners; [accessed 2021 May]. https://www.rcgp.org.uk/covid-19/-/media/C83FA88B25DD426E8BBBE35DF7A2F878.ashx.

- RCGP. 2021. The future role of remote consultations & patient ‘triage’. London (UK): Royal College of General Practitioners; [accessed 2021 June]. https://www.rcgp.org.uk/-/media/Files/Policy/future-role-of-remote-consultations-patient-triage.

- Reeve J. 2021. Scientific reasons to question teleconsultations in expert general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 71(707):271.

- Salman B, Hillman S, Atherton H, Dale J. 2021. Remote by default general practice: must we, should we, dare we? Br J Gen Pract. 71(707):254.

- Shah HA, Osman S. 2021. Time to rejuvenate the relic of home visits. Br J Gen Pract. https://bjgp.org/content/time-rejuvenate-relic-home-visit

- Sivarajasingam V. 2021. General practice after COVID-19: lessons learned. Br J Gen Pract. 71(707):268–269.

- Tuijt R, Rait G, Frost R, Wilcock J, Manthorpe J, Walters K. 2021. Remote primary care consultations for people living with dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic: experiences of people living with dementia and their carers. Br J Gen Pract. 71(709):e574–e582.

- Wenger E. 1999. Communities of practice: learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press.

- Wherton J, Shaw S, Papoutsi C, Seuren L, Greenhalgh T. 2020. Guidance on the introduction and use of video consultations during COVID-19: important lessons from qualitative research. Leader. 4(3):120–123.

- Yaseen A. 2021. Changes we learned to love in the time of COVID. Br J Gen Pract. 71(707):270.