Abstract

Background

In the UK, core surgical training (CST) is the first specialty experience that early-career surgeons receive but training differs significantly across CST deaneries. To identify the impact these differences have on trainee performance, we assessed whether success at the Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons (MRCS) examinations is associated with CST deanery.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study of UK trainees in CST who attempted MRCS between 2014 and 2020 (n = 1104). Chi-squared tests examined associations between locality and first-attempt MRCS performance. Multivariate logistic regression models identified the likelihood of MRCS success depending on CST deanery.

Results

MRCS Part A and Part B pass rates were associated with CST deanery (p < 0.001 and p = 0.013, respectively). Candidates that trained in Thames Valley (Odds Ratio [OR] 2.52 (95% Confidence Interval [CI] 1.00–6.42), North Central and East London (OR 2.37 [95% CI 1.04–5.40]) or South London (OR 2.36 [95% CI 1.09–5.10]) were each more than twice as likely to pass MRCS Part A at first attempt. Trainees from North Central and East London were more than ten times more likely to pass MRCS Part B at first attempt (OR 10.59 [95% CI 1.23–51.00]). However, 68% of candidates attempted Part A prior to CST and 48% attempted Part B before or during the first year of CST.

Conclusion

MRCS performance is associated with CST deanery; however, many candidates passed the exam with little or any CST experience suggesting that some deaneries attract high academic performers. MRCS performance is therefore not a suitable marker of CST training quality.

Introduction

Core Surgical Training (CST) is the first specialty training that prospective surgeons undertake in the United Kingdom (UK). During a two-year programme, trainees rotate through several specialties to acquire the competencies set out in the national CST curriculum (The Intercollegiate Surgical Curriculum Educating the Surgeons of the Future Citation2017). Trainees’ progress in meeting the demands of the curriculum is assessed by an Annual Review of Competence Progression (ARCP) and by the Intercollegiate Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons (MRCS) examination. Trainees are required to pass both of these gate-keeping assessments before they become eligible to apply for higher surgical specialty training (residency) posts after CST (Surgical Training in the U.K. Citation2021). CST, therefore, plays a pivotal role in shaping the education and experience of early-career surgeons.

Practice points

There is a statistically significant association between MRCS pass rates and CST deanery.

Trainees who trained in popular deaneries, such as London, performed better at MRCS.

Most candidates attempted the MRCS exams before obtaining little or any surgical experience.

We also found no correlation between perceived quality of training and deanery performance at MRCS.

Individual factors, such as academic ability and motivation may therefore have more of an impact on MRCS success than organisational influences, such as training deanery.

Individual factors, such as prior academic attainment, gender, ethnicity, age, and first language are known to predict future performance on the MRCS (Scrimgeour et al. Citation2017, Citation2018a, Citation2018b). These attainment differences are not exclusive to MRCS, having been identified in other high-stakes post-graduate medical examinations used internationally, such as the Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgery (FRCS) (Scrimgeour et al. Citation2019), Membership of the Royal College of Physicians (Dewhurst et al. Citation2007; Richens et al. Citation2016) and the United States Medical Licensing Examination (Rubright et al. Citation2019).

The impact of organisational influences on performance has received much less attention in surgical education. Yet, there is evidence that early teaching and training experiences during medical school impact performance (Wakeford et al. Citation1993; Bowhay and Watmough Citation2009; McManus et al. Citation2020). An earlier study demonstrated some regional differences in MRCS Part B (clinical) pass rates over a one-year study period (2008–2009) but lacked MRCS Part A results and detailed performance data (Fitzgerald and Giddings Citation2011). This performance difference may be related to the fact that CST experience can vary significantly between training deaneries (geographical location within the UK) in respect of both formal teaching provided and training opportunities available (ASiT/BOTA Lost Tribe Writing Group Citation2018). Variation in training is also reflected in trainee feedback via the General Medical Council’s (GMC) annual National Training Survey (NTS) which assesses the teaching and training provisions in each hospital across the UK (National Training Survey Citation2018).

A better understanding of potential organisational influences on later performance would enable trainees to make an informed choice when selecting CST deaneries. This information will also indicate for training institutions whether variation in training should be encouraged or minimised. Thus, to address this gap in the literature, we examined whether there was an association between MRCS performance and CST training location. Given that sociodemographic factors are known to influence both training deanery choice and MRCS performance we adjusted for these known predictors of MRCS success. We also assessed whether CST deanery performance at MRCS correlated with trainee NTS scores.

Methods

This is a longitudinal retrospective cohort study of all UK trainees in CST who had attempted either MRCS Part A (multiple-choice questionnaire) or MRCS Part B (OSCE) between September 2014 to February 2020. MRCS performance data were linked by administrators at the Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCS) to training data from the General Medical Council’s (GMC) list of registered medical practitioners (LRMP).

Context

Selection for CST training posts is highly competitive and involves national candidate ranking based on a portfolio score (in which marks are awarded for academic achievements), and performance at interviews which involves several Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) stations. Applicants rank their desired CST posts based on specialty rotations and training deanery and are allocated posts based on their national candidate ranking (Surgical Selection in the UK Citationdate unknown). Some deaneries, such as London and the surrounding areas are historically more competitive than others. Many individual factors may contribute to deanery preferences including perceived training opportunities and workplace culture, personality type, living costs, hierarchical prestige rankings, and sociodemographic factors, including wanting to work near social support networks (Borges and Savickas Citation2002; Goldacre et al. Citation2004; McNally Citation2008; Creed et al. Citation2010; Smith et al. Citation2015; Cleland et al. Citation2016; Querido et al. Citation2016; Kumwenda et al. Citation2018; Scanlan et al. Citation2020).

Data management

All data were handled with the highest standards of confidentiality and were anonymised by RCS administrators before statistical analysis. The following variables were extracted for analysis: MRCS Part A and B data, CST deanery, and sociodemographic predictors of MRCS; self-declared gender (male or female), first language (English or other), and age at graduation from medical school (<29 or ≥29 years old). The upper age of 29 years old has been used in previous studies to indicate mature trainees, many of whom studied medicine as graduate students (Scrimgeour et al. Citation2018a, Citation2019). Self-declared ethnicity was coded as ‘white’ or ‘non-white’ as used in previous studies (Scrimgeour et al. Citation2018b, Citation2019). This was to preserve candidate anonymity and to enable meaningful interpretation with powered analysis when encountering small cohort numbers, rather than being an ethical or social decision. The stage of training was extrapolated from the number of months between the date of graduation and the first attempt at MRCS. Candidate first-attempt results were used as they are the best predictor of future performance in post-graduate examinations (McManus and Ludka Citation2012; Scrimgeour et al. Citation2019). It should be noted that some surgical specialties offer run-through training posts that commence after completion of Foundation Training. For cohort homogeneity, MRCS candidates that were ‘run-through trainees’ were excluded from the study. NTS CST trainee satisfaction scores for each deanery were identified using raw data available from the GMC NTS results for 2018. For more information on how these scores are calculated and what questions are included in the NTS please refer to the GMC website (www.gmc-uk.org).

Statistical analysis

Chi-squared tests were used to identify possible associations with first attempt MRCS pass/fail outcomes. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for NTS overall CST trainee satisfaction scores and MRCS scores relative to pass mark. Multivariate regression models established the likelihood of MRCS success according to CST training location before and after adjusting for socio-demographic factors. Any sociodemographic factor with p < 0.10 on univariate analysis were entered into the multinomial regression models. Reference categories for each regression model were selected using the deanery with the mean MRCS pass rate closest to the mean for the entire study population. All analyses were conducted on anonymised data using SPSS® v26.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). As there is no formal ethical committee, the Intercollegiate Committee for Basic Surgical Examinations (ICBSE) and its Internal Quality Assurance (IQA) Subcommittee, which monitors standards and quality, approved this study.

Results

CST data were matched for 1104 MRCS Part A candidates and 659 MRCS Part B candidates (445 individuals were yet to sit Part B; 186 of whom had failed Part A and 259 individuals who had passed Part A but had not yet attempted Part B). The mean Part A pass rate at the first attempt was 49.4% (545/559), the mean percentage score relative to the pass mark was −2.3% (SD 13.6) and the average number of attempts taken to pass the examination was 1.9 (SD 1.2). The mean Part B pass rate at the first attempt was 81.2% (535/124), the mean percentage score relative to the pass mark was 17.9% (SD 9.4) and the average number of attempts taken to pass was 1.2 (SD 0.4).

Within the study population, 20% of candidates attempted MRCS Part A in Foundation Year 1 (FY1), 48% in Foundation Year 2 (FY2), 22% in CST year 1 (CST1), 7% in CST year 2 (CST2), and 3% attempted it more than 47 months after graduation from medical school. Only 0.3% of candidates attempted MRCS Part B in FY1, 8% in FY2, 39% in CST1, 32% in CST2, and 20.7% attempted it more than 47 months after graduation.

Demographic predictors of success

From the total study population, 57.3% of candidates were men, 64.8% were white, 92.8% were <29 years of age, and 87.9% stated that their first language was English. MRCS pass rates by gender, ethnicity, age, and first language are shown in . Differences in MRCS Part A pass rates were statistically significant for gender (p < 0.001), ethnicity (p < 0.001), and age (p = 0.002). Differences in MRCS Part B pass rates were statistically significant for age only (p < 0.001).

Table 1. MRCS first attempt pass rates by gender, ethnicity, age, and first language.

Training deanery

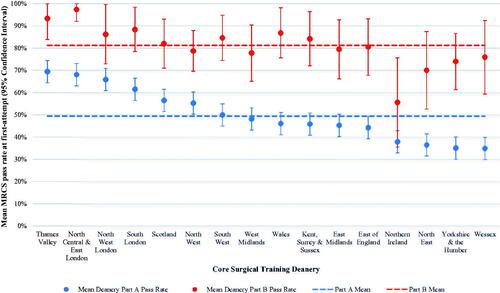

There was a statistically significant association between MRCS Part A (p < 0.001) and Part B (p = 0.013) first attempt pass rates and CST deanery. Statistically significant differences were found in mean Part A pass rates between deaneries, ranging from 34.9% (95% Confidence Interval [CI] 20.0–49.7) in Wessex to 69.4% (95% CI 53.6–85.3) in Thames Valley as shown in . Mean first attempt Part A score relative to pass mark ranged from −6.2 to 2.9% and the average number of attempts to pass ranged from 1.5 to 2.2 as shown in . There were statistically significant differences in mean Part B pass rates between deaneries which ranged from 55.6% (95% CI 35.5–75.6) in Northern Ireland to 97.4% (95% CI 92.0–100.00) in North Central and East London (). Mean first attempt Part B score relative to pass mark ranged from 14.6 to 22.5% and the average number of attempts to pass ranged from 1 to 1.3 (). also shows the variation in MRCS performance between CST deaneries and their corresponding GMC national training survey overall trainee satisfaction scores (results normally distributed). Pearson correction coefficients revealed no statistically significant correlation between NTS training satisfaction scores and deanery performance at MRCS Part A (r = 0.05, p = 0.085) or Part B (r = 0.04, p = 0.358).

Table 2. Variation in MRCS performance at first attempt between CST deaneries and their corresponding NTS overall trainee satisfaction scores.

Multivariate analysis

Odds ratios for passing MRCS at the first attempt for candidates attending each CST deanery are shown in (before and after adjusting for socio-demographic predictors of success). We found that trainees who undertook their CST in popular deaneries, such as Thames Valley (Odds Ratio [OR] 2.52 (95% Confidence Interval [CI] 1.00–6.42), North Central and East London (OR 2.37 [95% CI 1.04–5.40]) or South London (OR 2.36 [95% CI 1.09–5.10]) were each more than twice as likely to pass MRCS Part A at their first attempt. After adjusting for candidate age, trainees from North Central and East London were more than ten times more likely to pass MRCS Part B at the first attempt (OR 10.59 [95% CI 1.23–51.00]). Trainees from Northern Ireland had lower pass rates than average on MRCS Part A and Part B () and were 68% less likely to pass Part B at the first attempt (OR 0.32 [95% CI 0.11–0.96]). No other deaneries were found to independently predict success or failure at MRCS independent of each other and socio-demographic factors.

Table 3. Odds ratios for passing MRCS Part A and B at first attempt by training deanery before and after adjusting for sociodemographic predictors of success.

Training deaneries were dichotomised into those in the London area vs. elsewhere in the UK for further regression analyses. London-based trainees were 2.35 times more likely to pass MRCS Part A at the first attempt after adjusting for sociodemographic predictors of success (OR 2.35 [95% CI 1.55–3.55]). Trainees from elsewhere in the UK were 57% less likely to pass Part A at their first attempt (adjusted OR 0.43 [95% CI 0.28–0.64]). Similarly, London-based trainees were 2.80 times more likely to pass Part B at the first attempt after adjusting for sociodemographic factors (OR 2.80 [95% CI 1.40–5.57]) and trainees from elsewhere were 64% less likely to pass at first attempt (OR 0.36 [95% CI 0.18–0.72]).

Discussion

A statistically significant association was found between MRCS performance and CST training deanery in the UK. Core surgical trainees who trained in popular locations, such as London deaneries performed better at MRCS. This is not unexpected, given that high competition ratios at national selection result in a larger proportion of the best-performing candidates being recruited to the most popular deaneries, and prior academic attainment is the best predictor of future success in medical education and training (McManus et al. Citation2013a, Citation2013b; Scrimgeour et al. Citation2019). As a result, these deaneries continue to perform well in respect of the MRCS outcomes of their trainees, developing prestige over time which in turn will increase their desirability and perpetuate their competitiveness at the national selection.

However, is the deanery influential in terms of outcomes? The majority (68%) of Part A candidates attempted the examination before starting CST and a significant proportion (48%) attempted Part B before starting or within the first 12 months of CST. This is surprising given that the MRCS is an examination of the knowledge, experience, and clinical skill expected of trainees at the end of CST. These patterns suggest that Part A exam performance cannot be influenced by deanery for the majority of candidates, and will be of limited influence for just under half of those who sit Part B.

Findings from previous studies suggest that those candidates who sit in Parts A and B early are likely to be the stronger candidates. Candidates who sit Part A in FY1 have been found to perform better than their more senior peers as do those attempting Part B in CST1 (Scrimgeour et al. Citation2018a). Additionally, we found no correlation between the NTS score (a subjective score by CST trainees of the quality of training) and deanery performance at MRCS. This suggests that MRCS performance is unrelated to trainees’ perceptions of the quality of their training. Therefore, the association between CST training location and MRCS success is likely to be a reflection of popular deaneries attracting the best performing candidates rather than representing the differences in training experiences across deaneries.

Lastly, we found significant socio-demographic group level attainment differences in this study. These attainment differences reflect the findings of previous papers and warrant further investigation to rule out systemic bias in written examination questions (Scrimgeour et al. Citation2018a, Citation2019).

In conclusion, our findings indicate that while CST training plays a pivotal role in shaping the education and experience of early-career surgeons, it does not appear to be as instrumental to MRCS success as may be expected. The influence of earlier training experiences during foundation training and medical school on MRCS performance is currently unknown. Given that foundation training experiences vary significantly across deaneries and that surgical teaching and exposures differ considerably across UK medical schools, their possible influence on exam success warrants further investigation (McManus et al. Citation2020). However, most trainees gain little surgical experience during these years and therefore, it is likely that individual factors, such as academic ability, socio-demographic factors, and motivation play a larger role than organisational factors in shaping the future performance of surgical trainees. In retrospect, perhaps this is unsurprising given a large amount of post-graduate learning is self-directed, therefore variation in exposure to surgical specialties and training may not be reflected in traditional markers of performance.

This study confirms that MRCS performance is not a suitable assessment of the quality of surgical training in each CST deanery, and those applying for CST should not judge a deanery on the MRCS performance of its trainees. Other indicators, such as ARCP outcomes and success at national selection for higher specialty training, should also be considered. Measures of trainee satisfaction, such as NTS survey results may be more useful in terms of providing a holistic picture of each department, hospital, and deanery (National Training Survey Citation2018). While these are subjective scores that may vary significantly between individuals and cohorts, they allow trainees to highlight any training deficiencies and challenges within the learning environment that they have faced, information which is likely to be of use for those considering which deanery to apply to for CST.

We also know that trainee decision-making is influenced by ‘non-educational’ factors that may make a training location more or less desirable. As mentioned earlier, these include geographical, personal, sociodemographic, and socioeconomic considerations (Borges and Savickas Citation2002; Goldacre et al. Citation2004; McNally Citation2008; Creed et al. Citation2010; Smith et al. Citation2015; Cleland et al. Citation2016; Querido et al. Citation2016; Kumwenda et al. Citation2018; Scanlan et al. Citation2020). Deanery popularity and subsequent competitiveness may therefore have little to do with training quality, and more to do with trainee push-pull factors (Dussault and Franceschini Citation2006).

Strengths and limitations

Despite a large study cohort size, comparing data between 16 training deaneries inevitably results in smaller cohort numbers for comparison reducing statistical power. Larger cohort sizes may demonstrate statistical significance where there is a clear direction of effect within the current data. Additionally, to further isolate the impact that variation in training practices has between deaneries, further studies should adjust MRCS results for prior academic attainment, such as performance ranking at medical school (UKFP 2021 Applicants’ Handbook Citation2020) or performance on the impending UK Medical Licencing Assessment (Medical Licensing Assessment Citation2020).

Conclusion

There is a significant association between CST training deanery and MRCS performance in the UK. Candidates who trained in London deaneries performed better at MRCS. However, a considerable number of candidates pass the MRCS exams before obtaining little or any CST experience, and there is no correlation between perceived quality of training and deanery performance at MRCS. This suggests that individual factors, such as academic ability, are likely to play a more substantial role in shaping performance than core surgical training location.

Author contributions

RE wrote the first draft of the manuscript and performed statistical analyses with AL’s supervision. All authors contributed to, edited, and reviewed the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Peter Johnston for his valuable insights and expertise in reviewing an earlier draft of this paper. The authors would also like to acknowledge Iain Targett at the Royal College of Surgeons of England and John Hines and Gregory Ayre from the Intercollegiate Committee for Basic Surgical Examinations for their support during this project.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ricky Ellis

Mr. Ricky Ellis, MBChB, BSc, Urology Specialist Registrar and Intercollegiate Research Fellow, Institute of Applied Health Sciences, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, United Kingdom.

Jennifer Cleland

Professor Jennifer Cleland, Ph.D., Professor of Medical Education Research and Vice-Dean of Education, Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

Amanda J. Lee

Professor Amanda J. Lee, Ph.D., Chair in Medical Statistics and Director of the Institute of Applied Health Sciences, University of Aberdeen, United Kingdom.

Duncan S. G. Scrimgeour

Mr. Duncan S. G. Scrimgeour, Ph.D., Colorectal Specialist Registrar and Past Intercollegiate Research Fellow, Department of Colorectal Surgery, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Aberdeen, United Kingdom.

Peter A. Brennan

Professor Peter A. Brennan, Ph.D., Professor of Surgery, Consultant Maxillo-Facial Surgeon and Research Lead for the Intercollegiate Committee for Basic Surgical Examinations, Department of Maxillo-Facial Surgery, Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth, United Kingdom.

References

- ASiT/BOTA Lost Tribe Writing Group. 2018. Early years postgraduate surgical training programmes in the UK are failing to meet national quality standards: an analysis from the ASiT/BOTA lost tribe prospective cohort study of 2,569 surgical trainees. Int J Surg. 52:376–382.

- Borges NJ, Savickas ML. 2002. Personality and medical specialty choice: a literature review and integration. J Career Assess. 10(3):362–380.

- Bowhay AR, Watmough SD. 2009. An evaluation of the performance in the UK Royal College of Anaesthetists primary examination by UK Medical School and gender. BMC Med Educ. 9(1):38.

- Cleland J, Peter J, Watson V, Krucien N, Skåtun D. 2016. What do UK doctors in training value in a post? A discrete choice experiment. Med Educ. 50(2):189–202.

- Creed PA, Searle J, Rogers ME. 2010. Medical specialty prestige and lifestyle preferences for medical students. Soc Sci Med. 71(6):1084–1088.

- Dewhurst NG, McManus IC, Mollon J, Dacre JE, Vale AJ. 2007. Performance in the MRCP(UK) Examination 2003–4: analysis of pass rates of UK graduates in relation to self-declared ethnicity and gender. BMC Med. 5(1):8.

- Dussault G, Franceschini MC. 2006. Not enough there, too many here: understanding geographical imbalances in the distribution of the health workforce. Hum Resour Health. 4:12.

- Fitzgerald ED, Giddings C. 2011. Regional variations in surgical examination performance across the UK: is there a postcode lottery in training? Bulletin. 93(6):214–216.

- Goldacre MJ, Turner G, Lambert TW. 2004. Variation by medical school in career choices of UK graduates of 1999 and 2000. Med Educ. 38(3):249–258.

- Kumwenda B, Cleland J, Prescott GJ, Walker KA, Johnston PW. 2018. Geographical mobility of UK trainee doctors, from family home to first job: a national cohort study. BMC Med Educ. 18(1):314.

- McManus IC, Ludka K. 2012. Resitting a high-stakes postgraduate medical examination on multiple occasions: nonlinear multilevel modelling of performance in the MRCP(UK) examinations. BMC Med. 10(1):60.

- McManus IC, Woolf K, Dacre J, Paice E, Dewberry C. 2013a. The academic backbone: longitudinal continuities in educational achievement from secondary school and medical school to MRCP(UK) and the specialist register in UK medical students and doctors. BMC Med. 11(1):242.

- McManus IC, Dewberry C, Nicholson S, Dowell JS, Woolf K, Potts HWW. 2013b. Construct-level predictive validity of educational attainment and intellectual aptitude tests in medical student selection: meta-regression of six UK longitudinal studies. BMC Med. 11(1):243.

- McManus IC, Harborne AC, Horsfall HL, Joseph T, Smith DT, Marshall-Andon T, Samuels R, Kearsley JW, Abbas N, Baig H, et al. 2020. Exploring UK medical school differences: the MedDifs study of selection, teaching, student and F1 perceptions, postgraduate outcomes and fitness to practise. BMC Med. 18(1):136.

- McNally SA. 2008. Competition ratios for different specialties and the effect of gender and immigration status. J R Soc Med. 101(10):489–492.

- Medical Licensing Assessment. 2020. General Medical Council. https://www.gmc-uk.org/education/medical-licensing-assessment

- National Training Survey. 2018. General Medical Council. https://www.gmc-uk.org/education/how-we-quality-assure/national-training-surveys

- Querido SJ, Vergouw D, Wigersma L, Batenburg RS, De Rond MEJ, Ten Cate OTJ. 2016. Dynamics of career choice among students in undergraduate medical courses. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 33. Med Teach. 38(1):18–29.

- Richens D, Graham TR, James J, Till H, Turner PG, Featherstone C. 2016. Racial and gender influences on pass rates for the UK and Ireland specialty board examinations. J Surg Educ. 73 (1):143–150.

- Rubright JD, Jodoin M, Barone MA. 2019. Examining demographics, prior academic performance, and United States medical licensing examination scores. Acad Med. 94(3):364–370.

- Scanlan G, Johnston P, Walker K, Skåtun D, Cleland J. 2020. Today's doctors: what do men and women value in a training post? Med Educ. 54(5):408–418.

- Scrimgeour DSG, Cleland J, Lee AJ, Griffiths G, McKinley AJ, Marx C, Brennan PA. 2017. Impact of performance in a mandatory postgraduate surgical examination on selection into specialty training. BJS Open. 1(3):67–74.

- Scrimgeour DSG, Cleland J, Lee AJ, Brennan PA. 2018a. Which factors predict success in the mandatory UK postgraduate surgical exam: the intercollegiate membership of the Royal College of Surgeons (MRCS)? Surgeon. 16(4):220–226.

- Scrimgeour DSG, Brennan PA, Griffiths G, Lee AJ, Smith FCT, Cleland J. 2018b. Does the intercollegiate membership of the Royal College of Surgeons (MRCS) examination predict “on-the-job” performance during UK higher specialty surgical training? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 100(8):669–675.

- Scrimgeour DSG, Cleland J, Lee AJ, Brennan PA. 2019. Prediction of success at UK specialty board examinations using the mandatory postgraduate UK surgical examination. BJS Open. 3(6):865–871.

- Smith F, Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ. 2015. Factors Influencing Junior doctors' choices of future specialty: trends over time and demographics based on results from UK national surveys. J R Soc Med. 108(10):396–405.

- Surgical Selection in the UK. date unknown. Joint Committee on Surgical Training [accessed 2020 Dec 23]. https://www.jcst.org/introduction-to-training/selection-and-recruitment/

- Surgical Training in the U.K. 2021. Joint Committee on Surgical Training [accessed 2021 Jan 21]. https://www.jcst.org/uk-trainees/

- The Intercollegiate Surgical Curriculum Educating the Surgeons of the Future. Core Training. 2017. Intercollegiate Surgical Curriculum Programme. https://www.iscp.ac.uk/static/public/syllabus/syllabus_core_2017.pdf

- UKFP 2021 Applicants’ Handbook. 2020. UK Foundation Programme. https://foundationprogramme.nhs.uk

- Wakeford R, Foulkes J, McManus C, Southgate L. 1993. MRCGP pass rate by medical school and region of postgraduate training. Royal College of General Practitioners. BMJ. 307(6903):542–543.