Abstract

Purpose

To explore and describe medical students, postgraduate medical trainees, and medical specialists’ perceptions of creativity, the importance they attach to creativity in contemporary healthcare, and, by extension, how they feel creativity can be taught in medical education.

Methods

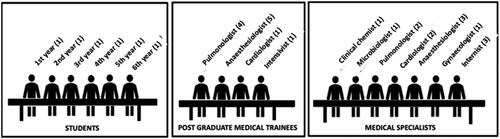

The authors conducted seven semi-structured focus groups with medical students (n = 10), postgraduate medical trainees (n = 11) and medical specialists (n = 13).

Results

Participants had a trifurcated perception of creativity, which they described as a form of art that involves thinking and action processes. Facing complex patients in a rapidly changing healthcare landscape, doctors needed such a multifaceted perspective to be able to adapt and react to new and often complex situations that require creativity. Furthermore, participants identified conditions that were perceived to stimulate and inhibit creativity in healthcare and suggested several techniques to learn creativity.

Conclusion

Participants perceived creativity as a form of art that involves thinking and action processes. Creativity is important to tackle the challenges of current and future workplaces, because it stimulates the search for original solutions which are needed in a rapidly changing healthcare landscape. Participants proposed different methods and techniques to promote creativity learning. However, we need further research to design and implement creativity in medical curricula.

1. Introduction

Society, and especially business and healthcare worldwide, have emphasised a need for creativity (Rometty Citation2012; Koh Citation2013; Lecher Citation2017; Turabian Citation2017; Eurelings Citation2018; Leopold et al. Citation2018). To successfully cope with the challenges of today’s workplaces, educational researchers have concluded that we need new skills such as flexibility and adaptability (Mylopoulos and Regehr Citation2009; Carbonell et al. Citation2014). As our healthcare systems are becoming increasingly complex, changing rapidly and largely unpredictable, scholars have also argued that we must learn to be creative so that we can adapt accordingly and continue to perform adequately (Koh Citation2013; Liou et al. Citation2016; Lith et al. Citation2016; Baruch Citation2017; Lecher Citation2017; Turabian Citation2017). In this, medical professionals are no exception, as they are increasingly faced with major challenges. To name one that almost every country is facing at this very moment is how to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic. This pandemic poses challenges at all levels of the organisation, including doctors in clinical care who have suddenly lost many fellow doctors and nurses to infection or burnout, are confronted with hospital bed shortages, while also needing to set up large-scale vaccination programmes.

Practice points

Participants had a trifurcated perception of creativity. They described creativity as a form of art that involves thinking as well as action processes.

Creativity is an important quality in a rapidly changing healthcare landscape that requires a multifaceted, flexible perspective to deal with increasingly complex patients.

This study reveals the importance of creativity to medical curricula and identifies various conditions for learning and enhancing creativity and associated educational techniques.

The aim of critical thinking is to deal with precisely these kinds of problems. Creative Problem Solving (CPS) techniques could support such thinking, for they encourage students to be open-minded and curious, think out of the box, conceptualise and reflect, allowing them to take a multi-perspective approach that is conducive to original and new insights. In this process, students also learn to improve their intuition and associative power and to use metaphors to solve problems. Students who are familiar with these techniques will contribute original, new and practical ideas. A preliminary survey by Jackson et al. (Jackson Citation2005) suggested that medical students need creativity to understand complex patients, make clinical decisions, solve problems, use technical or craft skills, and communicate thoughtfully and empathetically with each patient.

If we embrace this perspective that we need more creativity in healthcare, the first question that arises is: how do different stakeholders – medical students, postgraduate trainees and clinicians –, perceive creativity in medical education? As a term widely used, creativity is generally considered to be multifaceted, although its definition differs depending on the context (Csikszentmihalyi Citation1996; Amabile Citation1997; Lubart and Sternberg Citation1998; Treffinger et al. Citation2002; Robinson Citation2013; Min and Gruszka Citation2017). The question of how creativity is perceived by different groups of healthcare professionals (in training or otherwise), however, has hitherto not been explored.

In terms of learning, there is a consensus that it is possible to teach and stimulate creativity. Two meta-analytic studies, for instance, have showed that creativity training is effective. Also Rose and Lin (Citation1984) showed in their study that creativity training positively affected creativity in school settings. Scott et al. (Citation2004), in their turn, confirmed that creativity training indeed induced creativity in different organisations and academic settings (Rose and Lin Citation1984; Scott et al. Citation2004; Tsai Citation2013). Likewise, Amabile (Citation1998) argued that creativity, rather than being an innate trait, can be learnt. In her research, the author identified three different components of creative behaviour that can be influenced, which were: domain expertise, creative-thinking skills and motivation. She concluded that a conducive work environment can stimulate creativity (Amabile Citation1998; Amabile and Pillemer Citation2015).

Nevertheless, the said studies did not explore how creativity can be taught. After reviewing 156 creativity training programmes, Scott et al. (Citation2004) concluded that a creativity training programme has the most significant positive effect on creative outcomes when it is based on the cognitive capacities of problem finding, conceptual combination and idea generation. The CPS model (Isaksen and Treffinger Citation2004; Scott et al. Citation2004; Treffinger et al. Citation2006; Valgeirsdottir and Onarheim Citation2017) is one such training programme that focuses on the cognitive process. The existing literature, however, offers hardly any guidance on how to learn creativity through training programmes that focus on such processes in medical education. An exception is the scoping literature review by Lake et al. (Citation2015) who showed that students in medical education can boost their creativity by practising certain aspects of creativity, for example in theatre, dance, writing, poetry, literature, music, painting and the visual arts.

In light of the above, the present study seeks to address the following three research questions involving different groups of healthcare professionals (in training or otherwise):

What are medical students, postgraduate trainees and clinicians’ perspectives on creativity in the context of medical practice?

How do they perceive the importance of creativity in healthcare in general and in doctors’ daily clinical practice in particular?

How do they perceive creativity teaching and learning in medical education?

2. Methods

2.1. Setting

We conducted this study at Maastricht University Medical Centre+ (MUMC+) and the Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences (FHML), Maastricht University, the Netherlands. At the time of the study, these institutions were home to 437 medical specialists, 373 postgraduate medical trainees and 2067 medical students.

2.2. Design

Consistent with the exploratory nature of our research, we held semi-structured focus-group interviews. Such interviews are particularly instrumental in facilitating detailed descriptions of the understanding and experience around an unclear topic (Kitzinger Citation1995; Stalmeijer et al. Citation2014). We used the guideline by Assema et al. (Citation1992) to semi-structure the focus-group interviews around the three research questions (see Supplementary Appendix 1).

2.3. Sampling and participants

In the period spanning September to December 2018, we held seven focus-group interviews with three separate participant groups, specifically: medical students from the FHML of all years of study, postgraduate trainees from different disciplines and across all years of MUMC + and medical specialists from various MUMC + disciplines (see for more details about the specific group compositions). As our research focused on learning in medical undergraduate and postgraduate training, we chose these participants because they were the main groups of learners we could identify in this particular context.

We invited participants by email, newsletter and through the faculty’s social media page. Additionally, we used our personal networks to recruit participants. Thirty-four participants took part in the study. Of the seven interviews, we held two sessions with students (n = 6, n = 4), two with trainees (n = 5, n = 6) and three sessions with medical specialists (n = 4, n = 4, n = 5) (see ).

2.4. Procedure

The focus-group interviews were facilitated by a trained and experienced moderator (SJvL). An observer (AtH) was also present to take extensive notes of the discussion and nonverbal communication. Their rationales were probed whenever deemed necessary. We concluded that saturation was reached when no new topics emerged during the interviews. For all but one group this was the case after two interview rounds. With participants’ written informed consent, all focus-group interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Each participant received a summary of the session and was invited to make corrections and comments.

2.5. Analysis

The researchers conducted the qualitative data analysis using ATLAS.ti, version 8.0 (Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin), to manage the data including the focus-group transcripts. In doing so, they applied the generally accepted principles of primary, secondary and tertiary coding and constant comparison (Watling and Lingard Citation2012). This meant that codes were grouped into categories, which, in turn, were systematically checked against new data and arranged into broader, overarching themes (Strauss and Corbin Citation1990; Boeije Citation2009). Whereas AtH analysed all the transcripts, SJvL cross-checked the codes. Both researchers compared and discussed the codes until they reached consensus and overarching themes emerged. All co-authors discussed and agreed on these themes.

2.6. Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the Netherlands Association for Medical Education (NVMO) (file no. 2018.5.2). The moderator and observer had no professional relationship with participants of any kind. Nor did participants receive any financial compensation.

3. Results

In the following, we will present the results pertaining to each of the three research questions. In addition to this, we will provide schematic overviews of the results relative to questions 1 and 3 ( and , respectively). Each question will be further illustrated with representative quotes (listed in , respectively).

Table 1. Representative quotes illustrating participants’ trifurcated perception of creativity in daily healthcare.

Table 2. Representative quotes illustrating how creativity is manifested in healthcare in general and in daily care in particular.

Table 3. Representative quotes about creativity-enhancing techniques.

Research question 1: What are medical students, postgraduate medical trainees and clinicians’ perspectives on creativity in the context of medical practice?

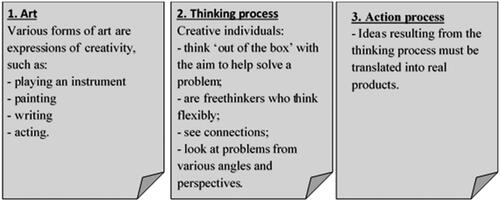

In this theme, we discussed participants’ perceptions. The majority of participants found it difficult to define creativity in the medical setting. They reported many different perceptions of creativity and commented that these perceptions, indeed, differed across individuals and contexts. Nevertheless, we were able to discern three main perceptions of the construct. First, many participants associated creativity with various forms of art, such as playing an instrument, painting and writing. Second, they held the view that creativity involved a process of thinking that takes place ‘out of the box’. Such process required dynamic adaptability and was enabled by the mechanisms of freethinking and seeing or making connections. Moreover, participants regarded creative thinking as a way to approach an issue from various angles and perspectives. Third, they added that there was more to creativity than this thinking process, as the ideas resulting from it had yet to be translated into real products or solutions. Hence, creativity was also perceived to encompass an action process. The said perceptions of 'thinking' and 'acting' were the expressions of creativity that were most frequently mentioned. gives a precise overview of each of the three main participant perceptions. Quotes to illustrate these perceptions are included in .

Research question 2: What importance do participants attach to creativity in healthcare in general and in doctors’ daily clinical practice in particular?

In this theme, participants explored how creativity emerged in healthcare in general and in doctors’ clinical practice in particular. They also discussed the perceived importance of creativity in healthcare. First, participants felt that patients with complex problems require doctors who are able to provide original, workable and personalised solutions. To be able to do so, they needed a multidimensional perspective, as many clinical presentations, contexts and care processes may deviate from standard protocols. Likewise, evidence-based medicine is often not seamlessly transferable or applicable to practice. In participants’ view, a doctor must therefore be able to think ‘outside the box’ or ‘think creatively’ to integrate the available, most suitable and applicable evidence with the clinical experience, personal preferences, values and contextual aspects of each individual patient. Second, participants felt that the rapidly changing healthcare environment also called for creativity, as it required doctors to adapt and react flexibly and dynamically to new and often complex situations. In this changing and unpredictable landscape, complex problems constantly arose that according to participants could only be solved if doctors, in addition to generating novel ideas, created and applied new, alternative solutions.

Many participants considered creativity important to a doctor’s performance and felt it helped raise the quality of healthcare delivery. A majority held the view that high-complexity care required broad thinking beyond guidelines and protocols, necessitating creativity in such contexts. The level of creativity required was dependent on the nature, content and context of a doctor’s activities. Participants agreed that, although varying in frequency, situations that do not follow standard practice, guidelines or protocols occur in all specialities and hence call for creativity. Yet, participants did not necessarily flag creativity as an absolute requirement or a mandatory quality that all doctors should possess. They believed that, in low-complexity, standardised settings, a doctor would be able to deliver high-quality care also without being creative. To illustrate how creativity takes shape in healthcare, lists several representative quotes from participants.

Research question 3: How do participants perceive creativity learning in medical education?

In this part of the study, participants discussed whether they perceived creativity to be an innate trait or skill that students could develop, what conditions they considered conducive to creativity learning, and whether they knew of any existing techniques to enhance this learning.

With respect to the first point of discussion, some participants felt that creativity was an innate trait (a specific talent, intuition or feeling inducing creativity), whereas others considered it more like a skill that anyone could develop. Despite this lack of consensus, participants did suggest conditions and techniques they believed could help promote creativity learning, as will be explained in the following.

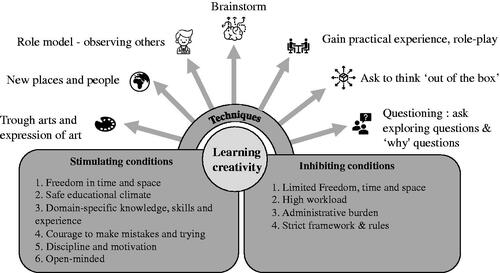

In response to the second point under discussion, participants mentioned several conditions that were perceived to stimulate the process of learning creativity. Taking more time and space to be creative, and a safe educational climate that allowed failures and gave proper guidance on how to develop creativity were seen as important enabling conditions. In addition to these, essential basic knowledge, cognitive skills and experience were also perceived to promote creativity. Other vital prerequisites were being sufficiently disciplined and motivated and learning to make mistakes, as well as being open-minded to different perspectives. Some participants also identified several inhibiting conditions. These included a lack of time and space to plan and execute tasks appropriately, owing to a high workload, administrative overload and an at times overly strict framework of protocols, guidelines and regulations.

In terms of strategies that could enhance creativity learning (the third discussion item), participants suggested encouraging students to explore issues more in depth by repeatedly asking them questions – especially ‘why’ questions. Also involving students in thinking ‘outside the box’ by brainstorming in an open-minded fashion, inviting them to provide multiple solutions, were techniques considered to boost creativity learning. Other ways to cultivate creativity were practical experience and role play involving clinical-care-related scenarios, as well as using role models who possess creativity-specific knowledge and skills and expose students to new places and people. Finally, some participants reported that creativity could be learnt through the arts by looking at art, making art, or through other forms of artistic expression.

below gives an overview of the conditions and techniques that were perceived to enable creativity learning. To elucidate these findings, we have listed several illustrative quotes in .

4. Discussion

In this focus-group study, we explored medical students, postgraduate medical trainees and medical specialists’ perspectives on creativity in the medical context. To the best of our knowledge, this study was the first to address creativity within a medical setting so far. We concluded that participants had a trifurcated perception of creativity, which they described as a form of art (1) that involved a thinking (2) as well as an action process (3). As the ‘creative part’ of critical thinking, CPS techniques can optimise critical thinking in students, by encouraging them to be open-minded and curious, think out of the box, conceptualise and reflect. In this process, they learn to improve their intuition and associative power as well as to use metaphors.

It follows that students who are familiar with these techniques are better equipped to face challenges in healthcare. Although participants did not necessarily flag creativity as an essential qualification any doctor should have, we might consider it an important complementary quality. Indeed, many situations in doctors’ daily practice require some level of creativity because many problems encountered do not follow standard practice, guidelines or protocols. These findings agree with those by Jackson et al. and other authors (Jackson Citation2005; Koh Citation2013; Liou et al. Citation2016; Lecher Citation2017; Turabian Citation2017) who suggested that creativity is a fundamental aspect of the medical field because it provides adequate solutions to rapidly changing problems.

Many participants doubted whether creativity was a skill anyone could develop, feeling that it was a characteristic a person does or does not possess by nature. This finding is contrary to previous study findings that creativity can be learnt and enhanced (Rose and Lin Citation1984; Scott et al. Citation2004; Tsai Citation2013). A plausible explanation for this might be that many people do not consider themselves creative (Dyer et al. Citation2012). Research has demonstrated that higher levels of creative self-efficacy, defined by Tierney and Farmer (Citation2002) as ‘the belief one has the ability to produce creative outcomes’, correspond with increased levels of creativity (Tierney and Farmer Citation2002, Citation2011; Brockhus et al. Citation2014). Hence, by changing an individual’s belief about their ability to be creative, they can become more creative.

In this study, we identified a wide range of conditions that stimulate and inhibit creativity. Participants expressed concerns about conditions that inhibit creativity, such as a lack of time owing to a high workload and administrative overload, and an overly strict framework of protocols, guidelines and regulations. This can be exemplary of the internationally acknowledged high workload and the associated increased risk of burnout among healthcare professionals (Boeke and Hoekstra Citation2018; van Esch and Soomers Citation2018). In a similar vein, these findings confirm Amabile’s conclusion that managers can influence creativity in the workplace (Amabile Citation1998; Amabile and Pillemer Citation2015). They also echo a workplace survey conducted by Gallup (2018) among a demographically representative sample of the US adult population. As in our study, this agency identified several factors similar to our conditions that foster creativity in the workplace, including sufficient time and space to be creative and a safe educational or working climate (Wigert and Robinson Citation2018).

4.1. Practical implications for medical education

Overall, this study supports the idea that creativity is important to help medical professionals overcome challenges in contemporary, complex healthcare. As outlined previously, studies have confirmed that creativity can be learnt and enhanced through creativity training programmes. Participants in this study also suggested several techniques for teaching and learning creativity that can be easily applied in medical curricula (see the Results section, research question 3). Some of the creativity-learning techniques our participants proposed, such as asking questions and brainstorming, bear a similarity to the CPS approach used by training programmes that focus on cognitive processes. CPS has already been applied successfully in various settings, including elementary, middle and high schools, colleges and universities, small and large businesses and different organisations (Treffinger Citation1995). Although CPS has evolved in the past 60 years to give rise to multiple versions of its model (Isaksen and Treffinger Citation2004), a few central phases have remained constant (Isaksen and Treffinger Citation2004; Puccio et al. Citation2006; Treffinger et al. Citation2006). We therefore welcome a further study or pilot project to test which of these CPS models suits the medical setting best.

4.2. Limitations of the study

The findings in this study are subject to at least three limitations. First, our data may not represent the whole population of medical students, postgraduate medical trainees and medical specialists. Second, the convenience sampling method we used of recruiting participants via personal emails and non-personal group emails influenced the various group compositions. Although some focus groups were limited in size, their homogeneous composition warranted the dynamics in the interviews. Third, in this study we did not differentiate between the various participant groups, the different medical specialities, the various levels of experience, nor did we control for age or gender effects.

4.3. Suggestions for further research

We invite researchers to carry out a more in-depth exploration of the role creativity plays within the different groups, addressing the question of whether the groups differ in their degree of creativity and, if so, why. Additionally, we welcome more work that aims to identify how best to teach medical students creativity. Finally, insights gained from the present and recommended future studies call for the development of a valid instrument to measure creativity in the medical setting.

4.4. Conclusion

Participants had a trifurcated perception of creativity, which they described as a form of art that involves thinking as well as action processes. They considered creativity a vital quality that was needed to tackle the challenges of modern-day healthcare workplaces. To care for complex patients in a healthcare system that is changing rapidly, doctors must be able to come up with original solutions. To be able to do so, they must learn to be creative and adopt a multidimensional perspective. Additionally, participants proposed various conditions and techniques to learn and enhance creativity. However, we need further investigation to design, evaluate and implement CPS skills training in medical curricula.

Glossary

Creativity: Creativity requires both originality and effectiveness.

Runco and Garrett (Citation2012).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (13.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the participants for generously contributing their time and expertise.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Annabel ten Haven

A. ten Haven, MSc, is a 6th-year medical student at the Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University. Her scholarly interests include creativity in the medical undergraduate and postgraduate curriculum.

Elien Pragt

Elien Pragt, MD, is an anaesthesiologist-intensivist in the Department of Intensive Care Medicine, and assistant professor at the School of Health Professions Education, Maastricht University, and Maastricht University Medical Centre+.

Scheltus Jan van Luijk

Scheltus J. van Luijk, MD, PhD, is a physician educationalist at the Maastricht University Medical Centre + Academy who takes an interest in the use and implementation of creative problem solving and design thinking techniques in medical education.

Diana H. J. M. Dolmans

Diana H.J.M. Dolmans, MSc, PhD, is a professor in the field of innovative learning arrangements and a staff member of the School of Health Professions Education, Maastricht University. Her research focuses on key success factors of innovative curricula within higher education.

Walther N. K. A. van Mook

Walther N.K.A. van Mook, MD, PhD, is an internist-intensivist in the Department of Intensive Care Medicine, scientific director of the Maastricht University Medical Centre + Academy, and professor at the School of Health Professions Education, Maastricht University.

References

- Amabile MT, Pillemer J. 2015. Creativity. Wiley Encyclopedia of Management. Vol 11. DOI:10.1002/9781118785317.weom110105

- Amabile T. 1997. Motivating creativity in organizations: on doing what you love and loving what you do. Calif Manage Rev. 40(1):39–58.

- Amabile T. 1998. How to kill creativity. Harv Bus Rev. 76:76–87. https://hbr.org/1998/09/how-to-kill-creativity.

- Assema P, Mesters I, Kok G. 1992. Het Focusgroep-interview: een stappenplan. T Soc Gezondheidszorg. 70(7):431–437.

- Baruch JM. 2017. Jay Baruch, MD: design thinking inside out - creativity as clinical skill - a role for “not knowing”. Stanford Medicine X. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q4pPazFEL5s.

- Boeije H. 2009. Analysis in qualitative research. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Boeke S, Hoekstra H. 2018. Meer tijd voor de patient. Enschede: Landelijke huisartsen vereniging.

- Brockhus S, van der Kolk TEC, Koeman B, Badke-Schaub PG. 2014. The influence of creative self-efficacy on creative performance. Proceeding of International Design Conference DESIGN 2014, 437–444.

- Carbonell KB, Stalmeijer RE, Könings KD, Segers M, Van Merriënboer J. 2014. How experts deal with novel situations: a review of adaptive expertise. Educ Res Rev. 12:14–29.

- Csikszentmihalyi M. 1996. Creativity - flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

- Dyer J, Gregersen H, Clayton MC. 2012. Crush the “I’m not creative” barrier. Canada: Harv Bus Rev. https://hbr.org/2012/05/crush-the-im-not-creative-barr.

- Eurelings LSM. 2018. Toys for the boys and pearls for the girls. Nederlands Tijdschrijft Geneeskunde. 162(51/52):38–39.

- Isaksen SG, Treffinger DJ. 2004. Celebrating 50 years of reflective practice: versions of creative problem solving. J Creat Behav. 38(2):75–101.

- Jackson M. 2005. Creativity in medicine and medical education. The higher education acadamy. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/a329/1bef5a0ebb7c69f0785035879e3ff167584a.pdf.

- Kitzinger J. 1995. Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. BMJ. 311(7000):299–302.

- Koh DL. 2013. Creativity and innovation in medical education: it’s time to let the trees grow freely. Ann Acad Med Singap. 42(11):557–558.

- Lake J, Jackson L, Hardman C. 2015. A fresh perspective on medical education: the lens of the arts. Med Educ. 49(8):759–772.

- Lecher R. 2017. Diversity, creativity, and flexibility will be needed from the next generation of medical scientists. Lancet. 389(Special issue, S!). DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30199-X

- Leopold TA, Ratcheva VS, Zaihidi S. 2018. The future of jobs report 2018. Switzerland: World Economic Forum.

- Liou KT, Jamorabo DS, Dollase RH, Dumenco L, Schiffman FJ, Baruch JM. 2016. Playing in the “gutter”: cultivating creativity in medical education and practice. Acad Med. 91(3):322–327.

- Lith J, Man R, Hoog M, Blaauwgeers H, Habets J. 2016. Opleiden is vooruitzien. Utrecht (the Netherlands): Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

- Lubart TL, Sternberg RJ. 1998. Creativity across Time and Place: life span and cross‐cultural perspectives. High Ability Stud. 9(1):59–74.

- Min T, Gruszka A. 2017. Handbook of the management of creativity and innovation: theory and practice. Chapter: 3. In: Tang Min, Christian H. Werner, editors. Singapore: World Scientific Press; p. 51–71.

- Mylopoulos M, Regehr G. 2009. How student models of expertise and innovation impact the development of adaptive expertise in medicine. Med Educ. 43(2):127–132.

- Puccio GJ, Firestien RL, Coyle C, Masucci C. 2006. A review of the effectiveness of CPS training: a focus on workplace issues. Creativity Inn Man. 15(1):19–33.

- Robinson K. 2013. To encourage creativity, Mr Gove, you must first understand what it is. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/may/17/to-encourage-creativity-mr-gove-understand.

- Rometty G. 2012. Leading trough connection. United States of America: International Business Machines Corporation. https://www-935.ibm.com/services/multimedia/anz_ceo_study_2012.pdf.

- Rose L, Lin HT. 1984. A meta-analysis of long-term creativity training. J Creative Behav. 18(1):11–22.

- Runco MA, Jaeger GJ. 2012. The standard definition of creativity. Creativity Res J. 24(1):92–96.

- Scott G, Leritz LE, Mumford MD. 2004. The effectiveness of creativity training: a quantitative review. Creativity Res J. 16(4):361–388.

- Stalmeijer RE, McNaughton N, Van Mook WN. 2014. Using focus groups in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 91. Med Teach. 36(11):923–939.

- Strauss A, Corbin J. 1990. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and technique. Qual Sociol. 13(1):3–21.

- Tierney P, Farmer SM. 2011. Creative self-efficacy development and creative performance over time. J Appl Psychol. 96(2):277–293.

- Tierney P, Farmer SM. 2002. Creative self-efficacy: its potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Acad Manag J. 45:1137–1148.

- Treffinger DJ. 1995. Creative problem solving: overview and educational implications. Educ Psychol Rev. 7(3):301–312.

- Treffinger DJ, Isaksen SG, Dorval KB. 2006. Creative problem solving: an introduction. Waco (TX): Prufrock Press Inc.

- Treffinger DJ, Young GC, Selby EC, Shepardson C. 2002. Assessing creativity: a guide for educators. Storrs (CT): National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented. http://www.gifted.uconn.edu/nrcgt.html.

- Tsai CK. 2013. A review of the effectiveness of creative training on adult learners. JSSS. 1(1):17–30.

- Turabian JL. 2017. Creativity in family medicine. Res Med Eng Sci. DOI: 10.31031/RMES.2017.01.000510 ISSN: 2576-8816.

- Valgeirsdottir D, Onarheim B. 2017. Studying creativity training programs: a methodological analysis. Creat Innov Manag. 26(4):430–439.

- van Esch E, Soomers V. 2018. Nationale aios-enquête 2018. Gezond en veilig werken. Utrecht (the Netherlands): De jonge specialist.

- Watling CJ, Lingard L. 2012. Grounded theory in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 70. Med Teach. 34(10):850–861.

- Wigert B, Robinson J. 2018. Fostering creativity at work: do your managers push or crush innovation? Gallup. https://www.gallup.com/workplace/245498/fostering-creativity-work-managers-push-crush-innovation.aspx.