Abstract

Introduction

Internationally the medical workforce is suffering from a persistent geographic and specialist maldistribution. Longitudinal models of rural medical education such as longitudinal integrated clerkships (LIC) have been one of the strategies employed to redress this issue.

Aim

To map and synthesise the evidence on the medical workforce outcomes of rural LIC graduates, identifying gaps in the literature to inform future research.

Methods

This review followed Arksey and O’Malley’s methodological steps. Databases searched included Medline, CINAHL Complete (EBSCOhost), Scopus, Embase (Elsevier), and ISI Web of Science.

Results

A total of 9045 non-duplicate articles were located, 112 underwent a full review, with 25 articles meeting the inclusion criteria. Studies were commonly cohort-based (84%), with data collected by database tracking and data linkage (52%). Five themes were identified to summarise the studies: (i) Overall geographic workforce outcomes (ii) influence of non-LIC medical training, (iii) remaining in region and level of rurality, (iv) medical speciality choice and rurality, and (v) selection and preferences.

Conclusion

Synthesis of the evidence related to workforce outcomes of rural LIC graduates provides directions for future rural medical workforce planning and research. While rural LIC graduates were found to be more likely to work rurally and in primary care specialities compared to graduates from other training pathways there is evidence to suggest this can be enhanced by strategically aligning selection and training factors.

1. Introduction

Internationally the medical workforce is suffering from a persistent geographic and specialist maldistribution with fewer doctors per head of population in rural communities compared to metropolitan areas and an increasing trend away from primary care specialities towards careers in subspecialties (National Rural Health Alliance Citation2012, Citation2021; Council of Graduate Medical Education Citation2022). Such multifaceted maldistributions contribute to rural communities having reduced access to health care compared to their metropolitan counterparts, culminating in higher rates of morbidity and mortality (National Rural Health Alliance Citation2012, Citation2021; Council of Graduate Medical Education Citation2022). One of the many strategies that has been implemented to provide rural communities with a medical workforce that meets their needs in terms of geographic and specialist distribution are longitudinal integrated clerkships (LICs) (Worley et al. Citation2016; O'Sullivan et al. Citation2018; McGirr et al. Citation2019).

Practice points

There is a positive association between participation in rural LIC programmes and graduates pursuing rural careers and undertaking primary care specialities.

Tracking rural LIC graduates over multiple time points would provide a more holistic understanding of rural retention patterns.

The precise definitions of rurality for both programme context and workforce outcomes and information on student selection processes should be included.

The concept of ‘train and retain’ seeks to embed medical students in rural communities for a substantial period of their training enabling them to build links within the medical and broader community, encouraging them to practice rurally once they have graduated (Strasser et al. Citation2013; Australian Government Citation2019). Previous scoping reviews have found that medical graduates who undertake extended periods of rural medical training are more likely to become rural doctors (O'Sullivan et al. Citation2018; Beks et al. Citation2022). A limitation of this work has been the absence of differentiation between the medical clerkship models, namely either traditional block rotations or LICs.

Rural LICs differ to block rotations in structure and setting. A central difference is that LIC students learn all medical disciplines simultaneously in an integrated manner (Norris et al. Citation2009; Ellaway et al. Citation2013; Worley et al. Citation2016; Witney et al. Citation2018). Practically, this sees students clinically exposed to, and participating in more than one core discipline over the course of a week. Rural block rotation students rotate primarily within a regional hospital setting, while rural LIC students are often attached to both a rural general practice/primary care setting and smaller rural health service (Kelly et al. Citation2014). The LIC setting allows the programme to be delivered in communities of increased remoteness when compared to rural block rotations (Kelly et al. Citation2014; Worley et al. Citation2016; Fuller, Lawson, et al. Citation2021). Given these significant structural and contextual differences, it is necessary to determine the impact of the LIC model of rural medical education on graduate rural workforce outcomes.

It is important to note that LIC programmes are not homogenous, with the definition and consensus of what constitutes a LIC programme varied (Worley et al. Citation2016). The International Consortium of Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships (CLIC) states ‘for a programme to be considered a LIC, students must participate in comprehensive care of patients over time and have continuing learning relationships with these patients’ clinicians’ (Consortium of Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships Citation2020). Furthermore, despite the CLIC definition not providing an absolute definition on the minimum duration of a LIC programme, it does state ‘students must meet the majority of the years core clinical competencies through the program’ (Consortium of Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships Citation2020). With this in mind a typology of LICs was developed by Worley et al. (Citation2016) providing an important differentiation framework for LICs (Worley et al. Citation2016). As such, both blended and comprehensive LIC programmes will be considered within this review as their duration is a minimum of 6 months (Worley et al. Citation2016; Consortium of Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships Citation2020).

As the number of rural LIC programmes has steadily increased over the preceding decades, numerous single-site studies and a limited number of reviews have been undertaken (Walters et al. Citation2012; Thistlethwaite et al. Citation2013; Brown et al. Citation2019; Bartlett et al. Citation2020). The initial literature focused on authenticating the clerkship model as a valid and equivalent form of medical education compared to block rotations (Walters et al. Citation2012; Thistlethwaite et al. Citation2013). With more rural LIC programmes now reaching a level of maturity there has been an increase in studies that have focused on the rural workforce outcomes of individual programmes, hence it is timely to synthesise this literature.

This scoping review aims to map and synthesise the available evidence on the medical workforce outcomes of graduates who have participated in a rural LIC to identify gaps in the literature and inform future research. Specific objectives include to determine (Beattie et al. Citation2022):

What literature is available on the workforce outcomes (practice location and medical specialty) of rural LIC programmes.

How the workforce outcomes (practice location and medical specialty) of rural LIC programmes have been described in the literature.

Elements of rural LIC medical programmes that have been shown to be positively associated with graduates working rurally.

What gaps exist in the current literature.

2. Methods

This review followed Arksey and O’Malley’s (Citation2005) scoping review methodological steps: (i) identifying the research question (ii) identifying relevant studies (iii) study selection (iv) charting the data, and (v) collating, summarising, and reporting (Arksey and O'Malley 2005). The rationale and methods for this scoping review have been published previously in a protocol paper (Beattie et al. Citation2022).

2.1. Identifying the research question

The population, exposure, and outcomes (PEO) framework was used to develop the research question.

Population: medical doctors

Exposure: rural LIC and

Outcome: medical workforce geographic practice locations (metropolitan/rural) and medical speciality.

The scoping review aimed to capture a breadth of literature hence the broad question of ‘what is known about rural Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships and medical workforce outcomes’ was used to inform the search strategy. Numerous search terms for each element were used to capture the available literature. For example, LIC programmes may be described as longitudinal immersion programmes or rural immersion programmes and within the studies, medical practitioners may have been referred to as students or graduates.

2.2. Identifying relevant studies

Cochrane database for systematic reviews, Medline, Prospero, and the Johanna Briggs Institute libraries were initially searched to confirm there were no existing or under development reviews on this specific topic (Beattie et al. Citation2022).

The search strategy was developed and trialled via the Medline and CINAHL databases with librarian assistance. This preliminary search identified relevant studies and along with previously known articles on the topic facilitated the development of appropriate search terms extracted from the titles, abstracts, and index terms. The search terms were then adapted for each individual database. Databases searched were Medline, CINAHL complete (EBSCOhost), Scopus, Embase (Elsevier), and ISI Web of Science. An indicative search strategy is illustrated in Supplementary File 1]. A snowballing technique was used to identify additional studies. This entailed searching the reference lists, citations, and journal sites of included articles. A search of Google scholar was also conducted. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are outlined in , with the rationale described in detail in the scoping review protocol (Beattie et al. Citation2022).

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.3. Study selection

Citations from located studies from the search of each database were collated and uploaded into Endnote X9 with duplicates removed (The EndNote Team, Inventor Citation2013). Studies were then transferred into the software program Covidence where two independent reviewers (JB and MB) screened the title and abstract of each paper for inclusion and exclusion criteria (Covidence Systematic Review Software Citation2022). Included studies then underwent a full-text review and were screened against the inclusion and exclusion data.

2.4. Data extraction and charting

For each article that met the inclusion criteria data were extracted by each reviewer independently. Both reviewers extracted data into an excel spreadsheet with predetermined categories (Supplementary File 2). This allowed for data mapping and ensured relevant and standardised information was recorded. Information extracted included authors, date of study, aims, main reported outcome, duration and setting of LIC, and LIC participants’ demographics.

2.5. Collating, summarising, and reporting the results

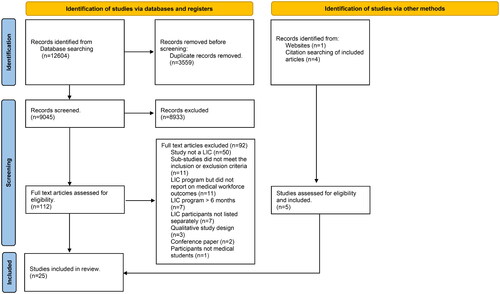

Quantitative and qualitative analysis was undertaken to synthesise the data. Quantitative descriptive data were tabulated and is presented as descriptive statistics. Qualitative thematic analysis was used to develop salient themes aligned with addressing the objectives of the scoping review. The quality of articles was not assessed as this is not the purpose of scoping reviews (Peters et al. Citation2020). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic and Meta Analysis extension for scoping review (PRISMA-Scr) was used to illustrate the study selection process (Page et al. Citation2021) ().

3. Results

The search strategies for all databases yielded 12,604 studies (final search March 2022) with 3559 duplicates removed (). Abstract and title screening was completed for 9045 articles with reviewers identifying 112 studies for full-text review. During the full-text review process, studies were again screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria resulting in the exclusion of 92 studies. The primary reason for exclusion was the study setting not being a rural LIC. Other reasons included the sub-studies in a review article not meeting the inclusion criteria, studies not reporting on medical workforce outcomes, duration of LIC was less than 6 months and workforce outcomes of rural LIC graduates were not reported separately. Snowballing of the 20 included studies located an additional 4 studies. A literature search of Google scholar located an additional article, resulting in 25 studies included in the final review.

3.1. Study characteristics

presents a quantitative description of the included studies. The most common study design was cohort-based studies (84%). Data were primarily collected by database tracking and data linkage (56%). Eighty percent of the articles were published in 2010 or later with the majority from Australian universities (60%). The most common course type was graduate entry (68%). The duration of LIC programmes varied from 9 months to 2 years but was most commonly 1 year in duration (68%). There were no multi-university studies directly comparing the medical workforce outcomes from two or more rural LIC programmes. Albeit one article did describe but did not compare, the two universities’ programmes, only one met the rural LIC inclusion criteria (Woolley et al. Citation2020). The majority of articles examined both geographic and speciality workforce outcomes (56%).

Table 2. Demographic description of studies.

3.2. Narrative description

Five themes were identified to summarise and describe key concepts from the studies. Themes were (i) overall geographic workforce outcomes (ii) influence of non-LIC medical training, (iii) remaining in region and level of rurality, (iv) medical speciality choice and rurality, and (v) selection and preferences.

3.3. Overall geographic workforce outcomes

About 32% (n = 8) of the articles described the workforce outcomes of LIC graduates only and did not compare this clerkship model to other forms of medical training (). The primary outcome reported was the percentage of graduates who were working rurally (17–60%) (Verby Citation1988; Stagg et al. Citation2009; Strasser et al. Citation2013; Playford et al. Citation2016; Bentley et al. Citation2019; Woolley et al. Citation2020; Bennett et al. Citation2021; Kitchener Citation2021). Small sample sizes were present in some studies due to the infancy of the programmes and because only a small percentage of their graduates participated in the rural LIC programme (Stagg et al. Citation2009; Bentley et al. Citation2019; Bennett et al. Citation2021; Kitchener Citation2021).

Comparisons of rural LIC to all other graduates within the same university found that rural LIC graduates were more likely to work rurally (). The primary outcome for most studies was the binary comparison of rural compared to metropolitan practice. Definitions of what constituted a rural and metropolitan location were based on national geographic classifications or the populations size of the community (Halaas et al. Citation2008; Bentley et al. Citation2019; Campbell et al. Citation2019; Bennett et al. Citation2021; Butler et al. Citation2021; Fuller, Beattie, et al. Citation2021).

Specific time points in the graduates’ careers were primarily studied rather than longitudinal tracking of graduates over multiple time points. The time points differed from a specific year such as the first year after graduating with the medical degree (Kitchener et al. Citation2015), residency year (Myhre et al. Citation2016) to reporting on multiple graduated cohorts ranging from postgraduate year (PGY) 1 to >30 years (Halaas et al. Citation2008; Playford and Cheong Citation2012; Campbell et al. Citation2019; Fuller, Beattie, et al. Citation2021; Kitchener Citation2021; Walker et al. Citation2021). Only one study tracked graduates’ work locations over a consecutive 5-year period (PGY 3–9), with rural background LIC graduates having a 23% increase in working rurally over the 5-year period (Playford et al. Citation2019).

There was no consistently reported time point in a graduate’s career that they were more likely to be working rurally. The majority of studies investigated graduates who were between PGY 1–10 finding variation between which groups were working rurally in higher numbers (PGY 1–2 or PGY 3–4) (Playford et al. Citation2014; Campbell et al. Citation2019; Fuller, Beattie, et al. Citation2021) while similarly, older programmes such as the Rural Physician Associate Program also had variation in the percentage of graduates working rurally by PGY groups (Halaas et al. Citation2008).

3.4. Influence of non-LIC training

As rural LIC programmes were commonly only 1 year in duration and did not encompass all clinical training years, some studies divided graduates into specific training pathways within the same university (Campbell et al. Citation2019; Fuller, Beattie, et al. Citation2021; Kitchener Citation2021). This entailed grouping LIC graduates by the training pathway they had either undertaken pre or post-the LIC year and comparing them to graduates who only undertook metropolitan and or rural block rotation training (Campbell et al. Citation2019; Fuller, Beattie, et al. Citation2021; Kitchener Citation2021). LIC graduates who had participated in further rural training (≥1 year) were more likely to be working rurally compared to graduates whose only rural training was the LIC year (Campbell et al. Citation2019; Fuller, Beattie, et al. Citation2021; Kitchener Citation2021). Australian studies found that rural LIC graduates who had undertaken additional rural training were between 5.04 and 7 times more likely to be working rurally compared to metropolitan training only (Campbell et al. Citation2019; Fuller, Beattie, et al. Citation2021). This group was also more likely to work rurally compared to graduates who had participated in other rural clerkships (>1 year) such as block rotations (Worley et al. Citation2008; Campbell et al. Citation2019; Fuller, Beattie, et al. Citation2021). Graduates whose only rural training experience was the rural LIC were working rurally at similar rates to rural block rotation graduates (Fuller, Beattie, et al. Citation2021).

Northern American studies investigated the influence of both the geographic location of (i) university campuses attended prior to the LIC year and (ii) vocational training (Zink et al. Citation2010; Woolley et al. Citation2020). Attendance at a rurally focused university campus (with an admission policy to select rural applicants) prior to the LIC year produced 54% of graduates working rurally compared to only 9% of the metropolitan training reference group (Zink et al. Citation2010). Vocational training in family medicine undertaken at the same university as the LIC programme produced up to 92% of graduates working in the university’s training footprint compared to only 24% of LIC graduates who completed this training at another university (Woolley et al. Citation2020).

The influence of the duration of a LIC programme on geographical work outcomes was only examined by one university that offered either a 1 or 2 year programme (Kitchener Citation2021). Participants in the 2-year programme were almost six times more likely to undertake a rural internship compared to those in the 1-year programme (Kitchener Citation2021).

3.5. Remaining in region and level of rurality

Rural LIC graduates practiced in geographic locations of greater rurality than comparator groups, with many remaining within the university’s rural training footprint (Kitchener et al. Citation2015; Playford et al. Citation2015; Myhre et al. Citation2016; Campbell et al. Citation2019; Playford et al. Citation2019; Kitchener Citation2021; Walker et al. Citation2021). Overall factors associated with working in communities of increased rurality were additional year/s of rural training, rural background, career progression and rural self-efficacy (Halaas et al. Citation2008; Hogenbirk et al. Citation2016; Bentley et al. Citation2019; Campbell et al. Citation2019).

The definitions of levels of rurality differed both within and between countries, with the same definition often used to describe both the geographic classification of the LIC programme location and the graduates’ places of practice. Levels of rural remoteness were based on access to services (inner regional, outer regional, remote, and very remote) or by communities’ populations (e.g. large rural cities defined as communities with a population of between 20,000 and 50,000, small rural populations of <20,000) (Playford et al. Citation2015; Bentley et al. Citation2019; Campbell et al. Citation2019; Bennett et al. Citation2021). In some studies, the rurality of the LIC programmes were described as being distributed across rural geographic areas within states/regions with limited reference to any rurality classification (Verby Citation1988; Verby et al. Citation1991; Halaas et al. Citation2008; Worley et al. Citation2008; Stagg et al. Citation2009; Zink et al. Citation2010; Playford et al. Citation2014; Bentley et al. Citation2019; Bennett et al. Citation2021; Butler et al. Citation2021; Walker et al. Citation2021).

Remaining in (or returning to) a region of focus was associated with universities’ social accountability mandates to serve the region where their medical students train (Strasser et al. Citation2013). Northern Ontario School of Medicine (NOSM) prioritise students for admission from the region and notably, all their medical students undertake a rural LIC (Strasser et al. Citation2013). Other studies highlighted the importance of local retention with Kitchener (Citation2021) finding 31% of interns were working within the university’s rural training footprint, while Halaas et al. (Citation2008) found 28.4% of their graduates were practising at rural LIC sites.

4. Medical speciality choice and rurality

Rural LIC graduates were more likely to specialise in general practice/primary care compared to comparator groups (Verby et al. Citation1991; Halaas et al. Citation2008; Zink et al. Citation2010; Butler et al. Citation2021). Within North America, 61–86% of rural LIC graduates were working in primary care specialities with the majority practicing in family medicine (Verby et al. Citation1991; Halaas et al. Citation2008; Zink et al. Citation2010; Strasser et al. Citation2013; Woolley et al. Citation2020; Butler et al. Citation2021). This was compared to 33.4–57% of non-rural LIC graduates selecting primary care specialities (Zink et al. Citation2010; Butler et al. Citation2021). This positive pattern was replicated within Australia as rural LIC graduates were up to 2.6 times more likely than metropolitan graduates to specialise in general practice (Worley et al. Citation2008; Walker et al. Citation2021).

Other influences on medical speciality were admission through a rurally focused pathway that had a selection bias towards students from rural communities who demonstrated an intent to practice both rurally and in primary care with 86% of these LIC graduates undertaking primary care specialities compared to 36% of graduates who did not enter through a rural pathway or participate in the LIC (Zink et al. Citation2010).

Not only were rural LIC graduates more likely to work in primary care specialities, but they were also more likely to practice this discipline rurally (Verby et al. Citation1991; Halaas et al. Citation2008; Zink et al. Citation2010; Strasser et al. Citation2013; Bentley et al. Citation2019). Commonly, rural LIC graduates who selected a speciality other than primary care were less likely to work rurally (Halaas et al. Citation2008; Stagg et al. Citation2009) but an exception was Bennett et al. (Citation2021) who found rural LIC graduates who had matched with a surgical programme (either general surgery or orthopaedic) had a similar percentage of graduates working in rural and metropolitan communities.

4.1 Selection variables and preferences

As only one programme mandated that all their students complete the LIC programme (Strasser et al. Citation2013; Woolley et al. Citation2020), the majority provided details about the selection policies for admission into the programme (Verby Citation1988; Verby et al. Citation1991; Halaas et al. Citation2008; Stagg et al. Citation2009; Zink et al. Citation2010; Playford et al. Citation2014; Kitchener et al. Citation2015; Playford et al. Citation2015; Myhre et al. Citation2016; Playford and Puddey Citation2017; Bentley et al. Citation2019; Campbell et al. Citation2019; Playford et al. Citation2019; Butler et al. Citation2021; Fuller, Beattie, et al. Citation2021; Kitchener Citation2021). Selection methods ranged from preferencing systems (Fuller, Beattie, et al. Citation2021) and random selection (Myhre et al. Citation2016) to competitive selection processes such as interviews, and written applications assessing criteria including, but not limited to motivation, academic ability, learning needs, knowledge of rural work, professional judgment, and ability to work effectively with peers (Verby Citation1988; Halaas et al. Citation2008; Kitchener et al. Citation2015; Playford and Puddey Citation2017; Playford et al. Citation2019; Butler et al. Citation2021; Playford et al. Citation2021). Capped small LIC cohorts resulted in students missing out on selection into these programmes (Halaas et al. Citation2008; Playford and Puddey Citation2017; Playford et al. Citation2019; Butler et al. Citation2021). One study specifically investigated the impact of clinical school preferencing and found that graduates who preferenced the LIC programme but did not gain a place were less likely to be working rurally than those who gained selection and participated (Playford and Puddey Citation2017). The voluntary nature of participation within the programme enabled the concentration of the limited rural education resources on interested students which was deemed a facilitator of successful rural workforce outcomes (Kitchener et al. Citation2015).

As an independent predictor of rural practice, rural background graduates were frequently found to be more likely to work rurally compared to graduates from a metropolitan background (Halaas et al. Citation2008; Worley et al. Citation2008; Playford et al. Citation2014; Hogenbirk et al. Citation2016; Playford and Puddey Citation2017; Campbell et al. Citation2019; Fuller, Beattie, et al. Citation2021). When rural background and rural LIC were combined and compared to other selection and training combinations, rural workforce outcomes were found to be enhanced compared to the independent predictors of either rural LIC alone or rural background alone (Playford and Cheong Citation2012; Campbell et al. Citation2019; Playford et al. Citation2019; Fuller, Beattie, et al. Citation2021). Playford et al. (Citation2019) found rural background/rural LIC graduates were nine times more likely to work rurally compared to metropolitan background and metropolitan training only, while Fuller, Beattie, et al. (Citation2021) found 66.7% rural background/rural LIC graduates who undertook further rural year at regional health service were working work rurally. Metropolitan background graduates who had participated in a rural LIC programme were just as likely to work rurally when compared to rural background graduates without rural LIC experience (Playford et al. Citation2016).

Often rural background students were statistically represented more strongly in rural LIC programmes compared to the overall cohort or metropolitan pathways (Zink et al. Citation2010; Woolley et al. Citation2020). This was more evident in North American programmes that had specific rural admission initiatives but was also apparent in Australian studies (Worley et al. Citation2008; Stagg et al. Citation2009; Zink et al. Citation2010; Strasser et al. Citation2013; Kitchener et al. Citation2015; Bentley et al. Citation2019; Campbell et al. Citation2019; Fuller, Beattie, et al. Citation2021).

5. Discussion

This scoping review synthesised the literature describing geographic and medical speciality workforce outcomes of graduates who have participated in a rural LIC programme. Aligned with Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) the aim was to explore the knowledge in this area rather than test a hypothesis (Arksey and O'Malley 2005). Overall, there is a body of evidence describing a positive association between participation in rural LIC programmes and graduates pursuing rural careers and undertaking primary care specialities.

LIC programmes are heterogenous, with variability between programmes in terms of duration, cohort size, programme selection policies and pre and post LIC training (Worley et al. Citation2016; Consortium of Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships Citation2020). As such it was arguably appropriate that only single-site studies were located for this scoping review, with the absence of multi-university studies possibly due to the inability to compare like with like and control for potential confounding factors. The prevalence of single-site studies may also be reflective of universities seeking to determine the effectiveness of clinical training in their rural footprint in meeting the needs of the local medical workforce (Beks et al. Citation2022).

Universities were observed to be transitioning from measuring the binary outcome of metropolitan compared to rural practice and increasingly investigating rural return rates through a more granular lens that seeks to analyse various levels of rurality (Halaas et al. Citation2008; Kitchener et al. Citation2015; Hogenbirk et al. Citation2016; Myhre et al. Citation2016; Bentley et al. Citation2019; Campbell et al. Citation2019; Playford et al. Citation2019). Moreover, as rural communities make significant financial, social, and educational investments in rural LIC programmes, there was an emerging focus on both graduates remaining in or returning to the programmes training region and by levels of rurality (Ellaway et al. Citation2013; Kitchener Citation2021).

Rural LIC programmes are often located in smaller rural towns rather than regional centres, with one of the clerkship’s founding objectives to provide students with the skills and experience to work in similar-sized towns post-graduation (Walters et al. Citation2012; Worley et al. Citation2016). Studies found that rural LIC programmes encouraged graduates to not only work rurally but work in smaller rural communities. Reporting on all levels of rurality based on the geographic classification systems of countries or jurisdictions provides for a more in-depth understanding of rural workforce outcomes (Beks et al. Citation2022). The same level of geographic classification should be consistently provided for the LIC programme footprint to allow for comparison between the rurality of training sites and eventual practice locations.

The methodologies employed by these studies, initially graduate surveys or more recently as workforce tracking has matured, data linkage techniques, generally captured a singular time point during a graduate’s career. While this provides valuable information, tracking graduates longitudinally over multiple time points is warranted, particularly as there were noticeable variations in workforce outcomes by PGYs. This may be reflective of the availability of rural pre-vocational and vocational training pathways and as one study highlighted, it may also be influenced by medical training policy during a specific period such as changes in the duration of vocational training (Verby Citation1988). The establishment of graduate migration and retention patterns would provide further context to elements associated with rural LIC graduates working rurally longitudinally and aid in informing polices for a sustainable medical workforce. In particular, it would allow for the tracking of all components of the medical training pathway such as geographic locations of vocational training. Such information, albeit still for only a single point in time was more transparent in the North American context where comparisons could be made based on the geographic locations where graduates undertook their vocational training. Positive workforce outcomes associated with vocational training in the same region as the LIC programme highlight the necessity of developing sustainable localised rural medical training pathways across the entire continuum, such as the National Rural Generalist Pathway in Australia that aims to train rural generalists with the specific skills required to meet the needs of rural communities (Australian Government Citation2021).

While studies identified participation in a rural LIC as an independent predictor of working rurally, this outcome was enhanced when combined with additional rural training. Further studies that focus on comparing different rural medical training clerkship models and rural training combinations are warranted. For example, a comparison of the combination of rural clerkship models (LIC and block rotations) and 2-year LIC programmes would provide valuable insight related to the influence of both the rural setting and clerkship pedagogy on medical workforce outcomes. The LIC pedagogy, which differs from traditional block rotations was often not well described within the studies. A reason for this might be that analyses of clerkship pedagogy elements and workforce outcomes do not lend themselves to quantitative methodologies. Qualitative studies may provide further insights into this area.

The findings that rural LIC graduates are more likely than comparison groups to work in primary care are noteworthy. Medical students have described the general practice learning environment as dynamic, enabling them to learn broadly about patients’ illnesses and their experiences, with participation in parallel consulting and the longitudinal trusting relationships LIC students develop with primary care supervisors considered a key influence on pursuing a career in primary care (Ogur and Hirsh Citation2009; Stagg et al. Citation2012; Glynn et al. Citation2021). Non-LIC students general practice experience is often a single time limited block rotation where they may be situated in more of an observer role rather than an active participant (Fuller, Lawson, et al. Citation2021). Alternately, LIC graduates’ preferences to work in this discipline may have been influenced by a desire to remain living rurally, as non-primary care specialities often require the majority of their training to be undertaken in metropolitan settings (Australian Government Citation2021). The tensions and relationship between geographic and specialist decisions is complex, with a range of other factors influencing speciality choice including lifestyle, work life balance, geography, workload, prestige and income, interest and scope of practice (Levaillant et al. Citation2020).

Rural background graduates were often proportionally more represented in rural LIC programmes than they were in metropolitan training pathways. This phenomenon either occurred by a process of self-selection or by universities’ policies to prioritise rural background students. The concept of self-selection into a LIC programme by students who already had rural intentions needs to be considered when interpretating these findings and future studies should describe student preferencing and programme allocation systems and where possible provide quantitative analyses associated with this variable. This information may help inform LIC selection and preferencing policies with the aim to recruit students to the clerkship that are more likely to work rurally.

Conclusion

This scoping review synthesises the body of evidence related to workforce outcomes of rural LIC programmes and provides directions for future rural medical workforce planning and research. While rural LIC graduates were found to be more likely to work rurally and in primary care specialities compared to graduates from other training pathways there is evidence to suggest this can be enhanced by strategically aligning selection and training factors. Qualitative research should be undertaken to examine elements of the LIC clerkship model other than being located in a rural setting that foster rural and primary care careers. Furthermore, the tracking of rural LIC graduates over multiple time points would provide a more holistic understanding of the medical training pathway and particularly training that compliments the LIC experience to enhance rural workforce outcomes.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (23.2 KB)Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of Deakin University librarian Julie Higgins in providing guidance on the development of the initial search strategy and the use of academic databases and information sources.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jessica Beattie

Jessica Beattie, MHHSM, Deakin University, School of Medicine, Rural Community Clinical School, Geelong, Victoria, Australia.

Marley Binder

Dr Marley Binder, PhD, Deakin University, School of Medicine, University Department of Rural Health, Warrnambool, Victoria, Australia.

Lara Fuller

Associate Professor Lara Fuller, FRACGP, Deakin University, School of Medicine, Rural Community Clinical School, Geelong, Victoria, Australia.

References

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. 2005. Scoping Studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Australian Government. 2019. Rural health multidisciplinary training (RHMT) program framework 2019–2020. Canberra: Canberra Department of Health and Ageing.

- Australian Government. 2021. National medical workforce strategy 2021–2031. In: care DoHaA, editor. Canberra: Canberra Department of Health and Ageing.

- Bartlett M, Couper I, Poncelet A, Worley P. 2020. The do’s, don’ts and don’t knows of establishing a sustainable longitudinal integrated clerkship. Perspect Med Educ. 9(1):5–19. doi: 10.1007/s40037-019-00558-z.

- Beattie J, Binder MJ, Fuller L. 2022. Rural longitudinal integrated clerkships and medical workforce outcomes: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 12(3):e058717. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-058717.

- Beks H, Walsh S, Alston L, Jones M, Smith T, Maybery D, Sutton K, Versace VL. 2022. Approaches used to describe, measure, and analyze place of practice in dentistry, medical, nursing, and allied health rural graduate workforce research in Australia: a systematic scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 19(3):1438. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031438.

- Bennett JMK, Raymond C, Kirb y C, Paula MT. 2021. Independent-academic vs. university-based surgical residency. Does rural medical training impact residency match? JRMC. doi: 10.24926/jrmc.v4i3.3621.

- Bentley M, Dummond N, Isaac V, Hodge H, Walters L. 2019. Doctors’ rural practice self-efficacy is associated with current and intended small rural locations of practice. Aust J Rural Health. 27(2):146–152. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12486.

- Brown ME, Anderson K, Finn GM. 2019. A narrative literature review considering the development and implementation of longitudinal integrated clerkships, including a practical guide for application. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 6:2382120519849409. doi: 10.1177/2382120519849409.

- Butler L, Rosenberg ME, Miller-Chang YM, Gauer JL, Melcher E, Olson APJ, Clark K. 2021. Impact of the rural physician associate program on workforce outcomes. Fam Med. 53(10):864–870. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2021.563022.

- Campbell DG, McGrail MR, O’Sullivan B, Russell DJ. 2019. Outcomes of a 1-year longitudinal integrated medical clerkship in small rural Victorian communities. Rural Remote Health. 19(2):4987. doi: 10.22605/RRH4987.

- Consortium of Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships. 2020. Core elements. [accessed]. https://clicmeded.com/.

- Council of Graduate Medical Education. 2022. Strengthening the rural health workforce to improve health outcomes in rural communities. Chicago (IL): Council of Graduate Medical Education.

- Covidence Systematic Review Software, Inventor. 2022. Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at: www.covidence.org.

- Ellaway R, Graves L, Berry S, Myhre D, Cummings BA, Konkin J. 2013. Twelve tips for designing and running longitudinal integrated clerkships. Med Teach. 35(12):989–995. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.818110.

- Fuller L, Beattie J, Versace V. 2021. Graduate rural work outcomes of the first 8 years of a medical school: what can we learn about student selection and clinical school training pathways? Aust J Rural Health. 29(2):181–190. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12742.

- Fuller L, Lawson M, Beattie J. 2021. The impact of clerkship model and clinical setting on medical student’s participation in the clinical workplace: a comparison of rural LIC and rural block rotation experience. Med Teach. 43(3):307–313. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1839032.

- Glynn LG, Regan AO, Casey M, Hayes P, O’Callaghan M, O’Dwyer P, Culhane A, Cuddihy J, Connell BO, Stack G, et al. 2021. Career destinations of graduates from a medical school with an 18-week longitudinal integrated clerkship in general practice: a survey of alumni 6 to 8 years after graduation. Ir J Med Sci. 190(1):185–191. doi: 10.1007/s11845-020-02260-0.

- Halaas GW, Zink T, Finstad D, Bolin K, Center B. 2008. Recruitment and retention of rural physicians: outcomes from the rural physician associate program of Minnesota. J Rural Health. 24(4):345–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00180.x.

- Hogenbirk JC, Timony PE, French MG, Strasser R, Pong RW, Cervin C, Graves L. 2016. Milestones on the social accountability journey: family medicine practice locations of Northern Ontario School of Medicine graduates. Can Fam Physician. 62(3):e138–145.

- Kelly L, Walters L, Rosenthal D. 2014. Community-based medical education: is success a result of meaningful personal learning experiences? Educ Health (Abingdon). 27(1):47–50. doi: 10.4103/1357-6283.134311.

- Kitchener S. 2021. Local and regional workforce return on investment from sponsoring rural generalist-based training for medical students. Aust Health Rev. 45(2):230–234. doi: 10.1071/AH19090.

- Kitchener S, Day R, Faux D, Hughes M, Koppen B, Manahan D, Lennox D, Harrison C, Broadley SA. 2015. Longlook: initial outcomes of a longitudinal integrated rural clinical placement program. Aust J Rural Health. 23(3):169–175. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12164.

- Levaillant M, Levaillant L, Lerolle N, Vallet B, Hamel-Broza JF. 2020. Factors influencing medical students’ choice of specialization: a gender based systematic review. EClinicalMedicine. 28:100589. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100589.

- McGirr J, Seal A, Barnard A, Cheek C, Garne D, Greenhill J, Kondalsamy-Chennakesavan S, Luscombe GM, May J, Mc Leod J, et al. 2019. The Australian Rural Clinical School (RCS) program supports rural medical workforce: evidence from a cross-sectional study of 12 RCSs. Rural Remote Health. 19(1):4971. doi: 10.22605/RRH4971.

- Myhre DL, Bajaj S, Woloschuk W. 2016. Practice locations of longitudinal integrated clerkship graduates: a matched-cohort study. Can J Rural Med. 21(1):13–16.

- National Rural Health Alliance. 2012. The factors affecting the supply of health services and medical professionals in rural areas. Canberra: National Rural Health Alliance.

- National Rural Health Alliance. 2021. Rural health in Australia snapshot. Canberra: National Rural Health Alliance.

- Norris TE, Schaad DC, DeWitt D, Ogur B, Hunt DD. 2009. Longitudinal integrated clerkships for medical students: an innovation adopted by medical schools in Australia, Canada, South Africa, and the United States. Acad Med. 84(7):902–907. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a85776.

- O’Sullivan BG, McGrail MR, Russell D, Chambers H, Major L. 2018. A review of characteristics and outcomes of Australia’s undergraduate medical education rural immersion programs. Hum Resour Health. 16(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s12960-018-0271-2.

- Ogur B, Hirsh D. 2009. Learning through longitudinal patient care-narratives from the Harvard Medical School-Cambridge Integrated Clerkship. Acad Med. 84(7):844–850. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a85793.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71.

- Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, McInerney P, Godfrey CM, Khalil H. 2020. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 18(10):2119–2126. doi: 10.11124/JBIES-20-00167.

- Playford D, Ngo H, Atkinson D, Puddey IB. 2019. Graduate doctors’ rural work increases over time. Med Teach. 41(9):1073–1080. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2019.1621278.

- Playford D, Ngo H, Puddey I. 2021. Intention mutability and translation of rural intention into actual rural medical practice. Med Educ. 55(4):496–504. doi: 10.1111/medu.14404.

- Playford D, Puddey IB. 2017. Interest in rural clinical school is not enough: participation is necessary to predict an ultimate rural practice location. Aust J Rural Health. 25(4):210–218. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12324.

- Playford DE, Cheong E. 2012. Rural undergraduate support and coordination, rural clinical school, and rural Australian medical undergraduate scholarship: rural undergraduate initiatives and subsequent rural medical workforce. Aust Health Rev. 36(3):301–307. doi: 10.1071/AH11072.

- Playford DE, Evans SF, Atkinson DN, Auret KA, Riley GJ. 2014. Impact of the Rural Clinical School of Western Australia on work location of medical graduates. Med J Aust. 200(2):104–107. doi: 10.5694/mja13.11082.

- Playford DE, Ng WQ, Burkitt T. 2016. Creation of a mobile rural workforce following undergraduate longitudinal rural immersion. Med Teach. 38(5):498–503. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1060304.

- Playford DE, Nicholson A, Riley GJ, Puddey IB. 2015. Longitudinal rural clerkships: increased likelihood of more remote rural medical practice following graduation. BMC Med Educ. 15(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0332-3.

- Stagg P, Greenhill J, Worley PS. 2009. A new model to understand the career choice and practice location decisions of medical graduates. Rural Remote Health. 9(4):1245.

- Stagg P, Prideaux D, Greenhill J, Sweet L. 2012. Are medical students influenced by preceptors in making career choices, and if so how? A systematic review. Rural Remote Health. 12:1832.

- Strasser R, Hogenbirk JC, Minore B, Marsh DC, Berry S, McCready WG, Graves L. 2013. Transforming health professional education through social accountability: Canada’s Northern Ontario School of Medicine. Med Teach. 35(6):490–496. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.774334.

- The EndNote Team, Inventor. 2013. EndNote. Philadelphia (PA): The EndNote Team, Inventor.

- Thistlethwaite JE, Bartle E, Chong AA, Dick ML, King D, Mahoney S, Papinczak T, Tucker G. 2013. A review of longitudinal community and hospital placements in medical education: BEME Guide No. 26. Med Teach. 35(8):e1340-1364–e1364. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.806981.

- Verby JE. 1988. The Minnesota Rural Physician Associate Program for medical students. J Med Educ. 63(6):427–437. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198806000-00001.

- Verby JE, Newell JP, Andresen SA, Swentko WM. 1991. Changing the medical school curriculum to improve patient access to primary care. Jama. 266(1):110–113. doi: 10.1001/jama.1991.03470010114041.

- Walker L, Isaac V, Walters L, Craig J. 2021. Flinders University rural medical school student program outcomes. Aust J Gen Pract. 50(5):319–321. doi: 10.31128/AJGP-06-20-5492.

- Walters L, Greenhill J, Richards J, Ward H, Campbell N, Ash J, Schuwirth LW. 2012. Outcomes of longitudinal integrated clinical placements for students, clinicians and society. Med Educ. 46(11):1028–1041. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04331.x.

- Witney M, Isaac V, Playford D, Walker L, Garne D, Walters L. 2018. Block versus longitudinal integrated clerkships: students’ views of rural clinical supervision. Med Educ. 52(7):716–724. doi: 10.1111/medu.13573.

- Woolley T, Hogenbirk JC, Strasser R. 2020. Retaining graduates of non-metropolitan medical schools for practice in the local area: the importance of locally based postgraduate training pathways in Australia and Canada. Rural Remote Health. 20(3):5835.

- Worley P, Couper I, Strasser R, Graves L, Cummings BA, Woodman R, Stagg P, Hirsh D. 2016. A typology of longitudinal integrated clerkships. Med Educ. 50(9):922–932. doi: 10.1111/medu.13084.

- Worley P, Martin A, Prideaux D, Woodman R, Worley E, Lowe M. 2008. Vocational career paths of graduate entry medical students at Flinders University: a comparison of rural, remote and tertiary tracks. Med J Aust. 188(3):177–178. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01567.x.

- Zink T, Center B, Finstad D, Boulger JG, Repesh LA, Westra R, Christensen R, Brooks KD. 2010. Efforts to graduate more primary care physicians and physicians who will practice in rural areas: examining outcomes from the university of Minnesota-Duluth and the rural physician associate program. Acad Med. 85(4):599–604. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d2b537.