Abstract

Purpose

The development of Educator Identity has a significant impact on well-being, motivation, productivity, and the quality of teaching. Previous research has shown that conflicting responsibilities and a challenging work environment could negatively affect the development of Clinical Educator Identity within an organization. However, there is a lack of research that identifies the factors affecting Clinical Educator Identity Formation and provides guidance on how organizations can support its development, maintenance, and advancement.

Methods

To examine the phenomenology of Professional Identity Development in experienced Senior Clinical Educators in Singaporean hospitals, the study utilized an exploratory qualitative approach. The data was collected from September 2021 to May 2022 through one-to-one interviews. Four investigators analyzed the data using constant comparative analysis to identify relevant themes.

Results

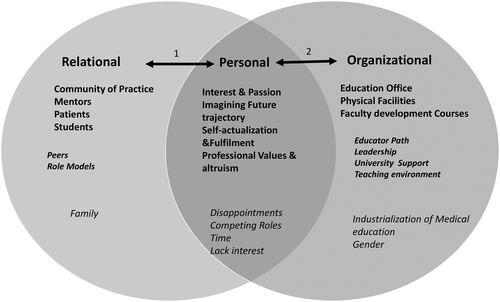

Eleven senior educators revealed that personal, relational, and organizational factors influenced the development of Clinical Educator Identity. The relational aspect was a vital enabler, while organizational culture was a strong barrier. The study also identified several ways in which organizations can support Educator Identity development.

Conclusion

The study findings provide insight into how organizations can support the development of Clinical Educator Identity. The results could aid organizations in understanding the areas where they can channel resources to support Clinical Educator Identity development.

Introduction

Professional identity is the perception of oneself as a professional, i.e. who one is, one’s relationship with the profession, and how one’s behavior aligns with the norms and culture within the professional community (Monrouxe et al. Citation2015). Professional identity influences critical aspects of professional well-being, such as productivity, motivation, and career satisfaction (OʼSullivan and Irby Citation2011; Cruess et al. Citation2016; Steinert et al. Citation2019).

Practice points

The study explores how personal, relational, and organizational factors impact Senior Clinical Educator Identity Formation (CEIF).

Strong relationships enhance CEIF, while organizational culture can hinder it.

Building a formal community of practice is vital for CEIF growth.

Promoting positive role models, especially through faculty development, empowers young educators.

Academic medical centers necessitate leadership support and organizational changes for clinical educators’ career growth.

A strong Clinical Educator (CE) identity is shown to be crucial in advancing the quality of clinical faculty and medical education (OʼSullivan and Irby Citation2011; Cruess et al. Citation2014).

For example, clinicians with education roles who did not identify educators were not enthusiastic about teaching and unwilling to participate in faculty development programmes to enhance teaching competency (Steinert et al. Citation2019). This phenomenon has resulted in CE’s fatigue, decreased quality of medical education, and hampered clinicians’ interest in being educators (OʼSullivan and Irby Citation2011; Cruess et al. Citation2014).

Research showed multiple organizational factors hindering Clinical Educator Identity Formation (CEIF) (van Lankveld et al. Citation2016). For example, whether the organization values clinical education may affect CEIF. Other ways include the opportunities and resources the organization provides for education, and interpersonal and social dynamics at various levels of the organization (Campion et al. Citation2016). Healthcare organizations including academic medical centers do not have a well-defined academic career pathway compared to physician-scientists for CEs (Sherbino et al. Citation2010; Cantillon et al. Citation2019). In addition, many academic medical centers require clinicians to take on clinical duties, teaching, administration, and research (Steinert et al. Citation2009; Cantillon et al. Citation2019). In the struggle to develop in these multiple roles, CEIF becomes challenging or impeded.

Research on Professional Identity Formation (PIF) in healthcare professionals has yet to identify the strengthening and constraining factors that affect CEIF in great depth nor delineate its intricacies (Bartle and Thistlethwaite Citation2014; Browne et al. Citation2018). There is limited literature on CEIF in a non-Western setting where culture, values, resources, and awareness of PIF may differ (Wahid et al. Citation2021). Current faculty development initiatives need to support CEIF (Steinert et al. Citation2019). There needs to be guidance on how the organization can help CEIF (O’Sullivan Citation2019; Steinert et al. Citation2019).

Theoretical framework

Identifying the strengthening and constraining factors that affect CEIF garners a call for action for organizations to support CEIF (Cruess et al. Citation2014; van Lankveld et al. Citation2021). This understanding would enhance the quality of faculty and the growth of the health professional community (Triemstra et al. Citation2021). Also, exploring CEIF will help us find innovative teaching methods to stimulate, influence, and sustain identity development in faculty development initiatives and harness resources effectively to support CEIF (van Lankveld et al. Citation2021).

Jarvis-Selinger et al. (Citation2012) described that the formation of professional identities was an adaptive, developmental process that happens simultaneously at two levels: (1) the individual level that involves the psychological development of the person (intrinsic factors), and (2) the collective level that involved socialization of the person into appropriate roles and forms of participation in the community’s work (extrinsic factors).

Furthermore, two other studies examined CEIF at both individual and collective levels. Cruess et al. (Citation2014) demonstrated how socialization influenced undergraduate students’ and residents’ professional identity development. van Lankveld et al. (Citation2016) identified five psychological processes that developed clinical educator identity, including ‘a sense of appreciation,’ ‘a sense of connectedness,’ ‘a sense of competence,’ ‘a sense of commitment,’ and ‘imagining a future career trajectory.’

This study aimed to answer the research question: How do community and organizational factors interact and affect CEIF in an Asian academic medical center?

Methodology

Study design and research method

This exploratory study was grounded in the constructivist paradigm to examine the phenomenology of CEIF of senior clinical educators (SCEs). The phenomenology study design describes the core commonality and lived-in structured experiences of our SCEs’ CEIF. We used the qualitative method utilizing one-on-one interviews through video conferencing, which allowed for a private, in-depth, and rich exploration of the personal experiences of these SCEs (Cristancho et al. Citation2018). We used video conference for the interview because the data collection was during the COVID-19 pandemic. The data collection spanned from September 2021 to May 2022.

Sampling and setting

This study was conducted in Singapore, a country in Southeast Asia, where the research regarding CEIF is still evolving. Participants came from six clinical sites in Singapore Health Services (SingHealth). SingHealth is one of Singapore’s three healthcare clusters. As an academic medical center, SingHealth is affiliated with a medical school and includes acute hospitals, national specialty centers, community hospitals, and primary care networks. SingHealth established the Academic Medicine Education Institute (AMEI) to provide faculty development opportunities to educators, to form a community of educators and leaders in education, committed to excellence in teaching and learning, and scholarly endeavors. Clinicians take on teaching and research roles, in addition to clinical responsibilities. Their teaching includes undergraduate, postgraduate, and continuing professional education both in the university and clinical setting. The teaching roles include, by not limited to, curriculum design, classroom and clinical teaching, assessment, faculty development, mentoring, leadership, and scholarly activities. All participants gave informed consent.

We used the purposeful sampling strategy to recruit senior doctors because their educator identities would have already been formed (Kegan Citation1982).

The participants fulfilled at least three out of five criteria:

Senior clinicians (the clinical rank of Senior Consultant or equivalent, with at least 25 years of clinical experience).

Senior faculty appointments with medical schools or postgraduate residency programs.

Formal training in health professions education with at least a certificate in health professional education.

Leadership roles in education of at least 5 years.

Recipients of teaching awards (Graham Citation2018).

Data collection and analysis

Semi-structured interview questions guided the data collection and analysis (see Supplementary Appendix). The interview questions were informed by Cruess et al. (Citation2014) and van Lankveld et al. (Citation2016) papers.

The interviewers included an education scientist experienced in conducting qualitative studies (CD) and an MHPE (Master of Health Professions Education) student who is a doctor with years of clinical experience (DL). The interviewers were not direct colleagues with the participants to mitigate influences due to power relations. The interviews were 60–90 min long, recorded and transcribed verbatim by a trained transcriptionist who was not involved in the study. The interviews were anonymized before analysis. Member checking of transcripts was performed.

After the first two interviews were completed, the transcripts were uploaded to ATLAS.ti version 22, a qualitative research software for data analysis and organization. Four investigators (DL, CD, YA, JY) started analysing the data in an iterative manner. For each transcript, for example, Transcript 1, two researchers (DL, CD) independently reviewed and developed a set of codes. The two researchers discussed the codes and identified pertinent themes (broader codes) using constant comparative analysis guided by the theory informing inductive data analysis. Similarly, the other two researchers (YA, JY) independently coded Transcript 2 and developed the themes. The four researchers discussed the codes and themes from the two transcripts and refined the set of codes, which were used to analyze the rest of the transcripts.

Thematic saturations were ensured before the cessation of data collection. Four investigators discussed the themes regularly to reach a consensus on the descriptive and analytic themes to ensure inter-coder reliability. All investigators kept their own reflexivity diary throughout the process.

Results

Demographics

Eleven participants, representing five specialties and six practice settings completed the interview. includes participants’ demographics.

Table 1. Demographics of senior clinical educators.

Factors influencing the development of a clinical educator’s professional identity

The factors that influence the development of the SCEs’s identity were grouped into three domains: personal, relational, and organizational, and each was further divided into the strengthening or constraining factors towards the growth of these participants’ educator identity.

illustrates the relationship between the three domains and how these factors affected and interacted with each other in shaping a senior educator’s identity. The relational factors are in the left circle, and the organizational in the right circle. The two levels interact and contribute to the personal level factors in the middle. The relational level (community) and the organizational level factors are as important as the personal level factors in shaping a senior educator’s identity. Strengthening factors are bold, constraining factors are italics, and both constraining and strengthening factors are bold plus italics. The arrows depict how each level influences the other through socialization as described by Cruess’s model (Cruess et al. Citation2014). Arrow Number 1 refers to the association between relational and personal factors. Arrow Number 2 refers to the association between organizational and personal factors.

Domain 1: Personal

Regarding strengthening factors, all 11 participants shared that they had high intrinsic motivation and enjoyed teaching. All SCEs felt a sense of fulfillment and altruism when they saw their students become successful in their careers. They wished to pay it forward and contribute to society, which was a common factor because their mentors or role models demonstrated similar traits.

The most common constraining factor was the lack of time and competing professional roles. SCEs often juggled multiple roles and had to prioritize their time to meet the various demands and responsibilities. Four SCEs expressed disappointment in the organizational culture and the perceived lack of education-interest and enthusiasm among their peers. However, these experiences did not deter the SCEs from continuing teaching. All SCEs persevered through adversity and improved their education competency through student feedback.

Domain 2: Relational

The relational domain pertains to the connections or relationships established by SCEs with those within and outside of the workplace. The main strengthening factors in this domain include interaction with students, patients, and mentors, which help the SCEs find a sense of belonging in the community. The sense of belonging enhanced SCEs’ commitment to education, thus boosting their educator identity. Seven SCEs mentioned that their primary motivation to teach was improving patient care and ensuring continuity of care. They felt that medical education should be translated into advancing the quality of patient care. Through interacting with students, the SCEs felt a sense of appreciation and self-fulfillment, whereas interaction with mentors often granted them direction and inspiration. Community practice gave SCEs a sense of belonging and enhanced camaraderie.

Constraining factors were primarily family commitments. Two SCEs felt that they were too heavily invested in their career at the expense of their families. This caused a sense of regret and guilt that hindered their educator’s identity development.

Peers and role models were perceived as both strengthening and constraining factors in the development of SCEs’ educator identity. Some peers helped to cover clinical duties while the SCEs taught. Peers who shared the same interest and commitment to education worked together to build their workplaces’ medical education culture. In contrast, others were less supportive of SCEs; for example, some were less willing to help and tried to compare clinical workloads and contributions.

All eleven SCEs mentioned the importance of role models during interviews. These role models heavily influenced their CEIF. Role models who committed to education created long-lasting positive impacts throughout these participants’ careers as educators. However, three specifically mentioned the effects of negative examples, who were uncommitted to education despite being in senior leadership positions.

Conversely, positive role models taught by example through patient care, communication, and professional behaviors, and their infectious passion and engaging teaching skills inspired the SCEs to become better educators. The role models also offered them opportunities for learning, career progression, and networking with other SCEs.

Domain 3: Organizational

The organizational culture plays an important role in shaping the senior CEs’ identity. The organizational culture spans a wide spectrum of aspects, such as the academic medical centre’s stance on the clinical educator career pathway, the organization leaders’ attitudes towards education, resources, and opportunities to support education. All the participants work in an academic medical centre. A lack of clear career paths for CEs and insufficient organizational support led to unsupportive teaching culture. All participants highlighted the importance of a clear educator career path, including guaranteed protected time, a structured and formalized rewarding system, including remuneration and recognition, easy access to faculty development, and opportunities for formal education in medical education for CEs. All the participants cited these reasons multiple times as the main barriers preventing educators from CEIF. In this study, the organizational barriers reduced the motivation and interest of SCEs in teaching, deterring CEIF ().

Five SCEs reported leaders who supported their educational ventures. Supportive leaders garnered resources and established processes to enable SCEs to pursue education career paths through manpower allocation, logistics, and financial support. These leaders also ensured that medical education was part of promotion and career progression performance indicators.

Interestingly, two female SCEs reported gender bias towards female SCEs, which was more prevalent during the 1980s. They shared that female clinicians were not given equal opportunities in their career advancement, especially in the surgical fields, and some colleagues even suggested that females should look after their families instead.

A common constraint raised by SCEs was that formalising medical education in academic medical centres brought more administrative matters and paperwork. This, in turn, distracted educators from focusing on teaching and mentoring students. Some participants shared that medical education has become too ‘industrialized.’ Due to increased administrative matters, competing roles, and changes in remuneration structures within healthcare organizations, some clinicians are placing greater emphasis on compensation, key performance indicators, and protected time, rather than teaching solely for altruistic reasons.

Recent efforts to improve medical education have led to the establishing of an administrative office to support clinical teaching and faculty development in hospitals. However, the participants shared that further improvements in teaching facilities are still needed to support medical education fully.

The SCEs felt that organizational culture, policies, and resources could support or hinder clinical education. A positive organizational culture that values education and professional development, recognized and rewarded educators, could create a more conducive environment for CEIF. Conversely, an organizational culture with sparse resources, limited administrative support, and inadequate recognition of educators would instead create barriers and challenges for clinical educators and would inhibit CEIF. Organizational culture, policies, and resources also affect the teaching environment. The participants felt that a well-structured organization with appropriate resources and a fair system of rewards and recognition would help clinical educators carry out their education responsibilities effectively.

Most SCEs shared that faculty development programs were a vital aspect of their CEIF. The organization recognized the importance of these programs and has implemented structured faculty development programs to support the development of SCEs. These programs allowed SCEs to acquire new knowledge, skills, and engage in reflective practice. Participation in these programs allowed SCEs to deepen their understanding of their role as educators and the larger context in which they work. Furthermore, these programs foster a sense of community and support among SCEs, which promotes CEIF. Through these programs, SCEs can gain a sense of purpose, direction, and meaning in their work, leading to improved outcomes for educators and students ().

Table 2. Quotes related to the strengthening and constraining factors toward developing SCEs’ educator identity.

Associations among the three domains

Our data showed that the interaction between personal and relational factors through socialization increases the motivation of SCEs in teaching by creating a sense of appreciation, connectedness, responsibility, and commitment to the future generation. These psychological processes motivated SCEs to contribute to education. This process led to the further strengthening of their educator identity. All these themes of physiological processes were illustrated in the box along with Arrow Number 1 in . Hence, this finding proved and demonstrated how the process of socialization by Cruess et al. (Citation2014) was linked and associated with van Lankveld et al. (Citation2016) psychological process of CEIF.

This established relationship aligned with Jarvis-Selinger et al. (Citation2012) framework that the relational and organizational factors would affect the psychological processes in CEIF. However, the theme of visualizing the progression of the educator career path did not appear in our data. There is no formal educator path available presently in the context of this study.

“It makes you happy, and then you don’t feel tired anymore. You may be very tired at the end clearly, but when somebody (students) say something nice, and you perk up right, so the positive reinforcement is important” (Participant2) (sense of appreciation)

“it’s really a journey, a journey through, as human interactions and human exchanges to learn together, and, I, I think I, I said the same for my patient(s) (that) I’m thankful to be a doctor, even though it was not my plan [laughs], errr, erhm, that I think I received as much, if not more than I give to my patients, and in my journey with many people, young people (students) …for every interaction, it’s always an opportunity” (Participant 9) (sense of connectedness)

“because we were taught by teachers, and this is traditional, and at least for me, I have had some of the best teachers who sacrificed their own after-office, after-office time for me. So, it is a way of reciprocation, and it is a tradition that I continue, that I try to instill in my students to continue.” (Participant 7) (sense of responsibility and commitment to the future generation)

Another relationship depicted in is how the organizational factor affects SCEs’ disposition (Arrow number 2 in ). As described above, constraining factors at the organizational level proved to impede CEIF by reducing SCEs’ motivation. The above findings emphasized how the three levels of constraining and strengthening factors interact and influence each other in affecting SCEs ’ motivation for medical education and CEIF.

Discussion

Our study showed how personal, relational, and organizational factors strengthened or hindered SCEs from CEIF. The findings added depth and dimension to the Van Lankveld (van Lankveld et al. Citation2016), and Cruess’s models (Cruess et al. Citation2014), especially in articulating how the different factors affect and interact with one another. The interactions among these domains confirmed the socialization process in promoting or deterring CEIF (Cruess et al. Citation2014). Also, this study added a greater understanding of the constraining and strengthening factors of CEIF to inform organizations to promote CEIF (van Lankveld et al. Citation2016). Cruess’s model was based on medical students’ and residents’ professional identity formation (Cruess et al. Citation2014). Hence, some elements, such as symbols and rituals, did not appear clearly in this study, while some themes, such as patient and student contact, were more pronounced.

The relational aspect was a vital enabler, whereas the organizational culture was a strong barrier. This finding was supported by Van Lankveld’s (van Lankveld et al. Citation2016) study, where the interaction between the community (peers, students, patients) and personal factors was crucial in developing positive physiological processes and intrinsic motivation for CEIF (van Lankveld et al. Citation2016). A formal or intentional community of practice can enhance CEIF through professional development, increased collegiality, providing a sense of empowerment for educators, and becoming a space for developing an understanding of belonging (Cantillon et al. Citation2016; van Lankveld et al. Citation2016). However, finding like-minded colleagues was not always easy (van Lankveld et al. Citation2016). Therefore, having a formal and structured educator’s community of practice is essential (van Lankveld et al. Citation2016). Singapore’s educator community of practice only started recently and did not exist during these SCEs’ CEIF years. Therefore, during interviews, the SCEs hardly revealed the community of practice theme in improving their CEIF.

Unlike Western culture, Singapore has a hierarchical culture grounded upon Confucianism, where power distance is vast, and the attitude towards leaders is formal with high respect, along with a strong culture of a heightened sense of responsibility and commitment to the future generation (Hofstede Citation2007). Seniors play a vital role model and influence juniors. The significant influence of role models shown in Western cultural contexts in CEIF was similar in this context (Cruess et al. Citation2014; van Lankveld et al. Citation2016). Negative role models have proven detrimental to CEIF, aligned with the published studies (Murakami et al. Citation2009; Bazrafkan et al. Citation2019). Recognizing positive role models and enhancing their visibility in an organization, primarily through faculty development initiatives, would empower young educators (Bazrafkan et al. Citation2019).

The findings from this study regarding the organization as an academic medical center as a constraining factor were supported by van Lankveld et al. (Citation2016). For example, like our participants, some academics felt that teaching is a second-class activity compared to research. The undervaluation of being an educator compared to a researcher led to tension in CEIF, causing a feeling of insecurity and reduced self-esteem among educators (van Lankveld et al. Citation2016). This reinforces the urgency for leadership support and organizational revamp in supporting clinical educators, especially in developing a clear career path to attract and nurture educators. Like what was experienced by the participants, leadership support is crucial in CEIF, for example, ensuring educators get similar protected time, rewards, remuneration, and recognition as clinical researchers (van Lankveld et al. Citation2016). These elements were regarded as critical in encouraging CEIF. Simultaneously as shared by our SCEs, it is also necessary to balance the organizational initiatives to ensure that medical education is not ‘industrialized’ or ‘professionalized’ where educators would be overwhelmed by the paperwork, administration, expectations, and demands which add to the workload (van Lankveld et al. Citation2016).

This study was grounded in the present literature, adding extended perspective and confirmability to the current data. The strength of this study was the broad representation of participants who were SCEs with formed educator identities from diverse specialties. Additionally, the cultural context is a single Asian country with rich resources, where CEIF is still being investigated in this region (Wahid et al. Citation2021). Most of what was known about CEIF among medical teachers has emerged from research in Western countries (Beauchamp and Thomas Citation2009; Nishigori et al. Citation2014; Cantillon et al. Citation2019; van Lankveld et al. Citation2021). To circumvent this, participants from multiple teaching institutions in one SingHealth Academic Center were engaged to ensure maximum-variation sampling. Two studies in the Indonesian context showed similar findings as ours, where there was a more substantial social basis and collectivist values than non-Western ones (Wahid et al. Citation2021; Soemantri et al. Citation2023). Further studies collaborating with other regional investigators will ensure greater transferability, consistency, and data reliability.

The main limitation was the presence of recall bias by the participants. This interview depended on the participants’ reflective process on their educator journey and CEIF. These participants have at least 25 years of clinical experience, and recalling their experiences can potentially cause the omission of some details (Creswell Citation2014). Additionally, the influences of CEIF during these participants’ time may not reflect the current context. To ease this recall bias, we sent the list of potential questions two weeks before the interview so that the SCEs could reflect on their development through the years in clinical education. In our next research study, we will interview clinical educators in various stages of their careers (i.e. early, developing, growing, maturing) and compare the findings among the different groups.

For future studies, we recommend critically evaluating interventions in supporting and developing CEIF. Suggestions for such intervention include faculty development programmes, such as the structured interprofessional community of practice, a definitive clinical educator path, and formal mentoring (Cruess et al. Citation2014; van Lankveld et al. Citation2016, Citation2021). Other interventions should include organizational transformation toward building a culture supportive of educators, such as appropriate resource sitting and leadership training (van Lankveld et al. Citation2021). There are no tools currently available to follow individuals’ progress towards acquiring educator identity, although frameworks, such as educator pathways are available (Cruess et al. Citation2014). Perhaps using a reflective educator portfolio or evaluating professionalism may be considered to track the progress of educator identity formation (van Lankveld et al. Citation2021).

In conclusion, this study adds to the literature gap by identifying the variables that influence CEIF, including those that sustain educators’ identity over time, using the combined model of Cruess and Van Lankveld. The results can be the first step to helping academic medical centers understand what affects CEIF and inform the design of future faculty development initiatives. The results will also allow institutions and relevant stakeholders to support the development and growth of CEIF through a clear educator path and work towards building educator identity and a robust community of practice.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board Determination (CRIB) (IRB num 2021/2414).

Disclaimers

None.

Previous presentation

The present manuscript is a section of the Master thesis for MHPE (Maastricht), which the first author presented during the thesis defense session. The abstract was also accepted by the AMEE 2023 conference and was presented as a short communication.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14.1 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to Professor Cees van der Vleuten, Professor Pim Teunissen, and Professor Yvonne Steinert for their invaluable feedback, which greatly contributed to the quality of this work. The authors also extend their appreciation to the SingHealth education team, comprising of Prof. Ong Thun How, Prof. Jason Chang, Prof. Derrick Aw, Prof. Melvin Chua, Dr. Andrew Ong, Dr. Warren Ong, Dr. Jansen Koh, Dr. Sally Ho, and Dr. Sandra Tan, for their invaluable support and assistance throughout the project. Lastly, the authors extend their heartfelt thanks to the participants for generously giving their time, effort, wisdom, and dedication, which helped make this study a success.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Deanna Wai-Ching Lee

Dr. Deanna Wai-Ching Lee, MBBS, MRCP, MHPE, is an internist and medical educationalist. She has an interest in faculty development and is heavily involved in curriculum development and assessment for undergraduate students.

Choon Kiat Nigel Tan

Dr. Choon Kiat Nigel Tan, MBBS, FAMS, FRCP, MHPEd, is a neurologist and holds leadership positions in several academic centers in Singapore.

Kevin Tan

Dr. Kevin Tan, BMedSci, BMBS, MRCP, FAMS, MS-HPEd, is a neurologist and has published widely in the field of neurology and health professions education.

Xianguang Joel Yee

Dr. Xianguang Joel Yee, MBBS, MMed, MRCP, is an internist and heavily involved in clinical teaching.

Yasmin Jion

Dr. Yasmin Idu Jion, MBBS, MRCP, MMed, is a neurologist and is heavily involved in postgraduate neurology training.

Herma Roebertsen

Dr. Herma Roebertsen, PhD, is a senior lecturer and educational adviser at Maastricht University. Her interest is in Faculty Development and Problem-Based Learning.

Chaoyan Dong

Dr. Chaoyan Dong, PhD, AMEE Fellow, is a medical educator with experience in systematic reviews. Her expertise is in simulation and medical education research.

References

- Bartle E, Thistlethwaite J. 2014. Becoming a medical educator: motivation, socialisation and navigation. BMC Med Educ. 14(1):110. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-110.

- Bazrafkan L, Hayat AA, Tabei SZ, Amirsalari L. 2019. Clinical teachers as positive and negative role models: an explanatory sequential mixed method design. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 12:11. doi: 10.18502/jmehm.v12i11.1448.

- Beauchamp C, Thomas L. 2009. Understanding teacher identity: an overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Camb J Educ. 39(2):175–189. doi: 10.1080/03057640902902252.

- Browne J, Webb K, Bullock A. 2018. Making the leap to medical education: a qualitative study of medical educators’ experiences. Med Educ. 52(2):216–226. doi: 10.1111/medu.13470.

- Campion MW, Bhasin RM, Beaudette DJ, Shann MH, Benjamin EJ. 2016. Mid-career faculty development in academic medicine: how does it impact faculty and institutional vitality? J Fac Dev. 30(3):49–64.

- Cantillon P, D'Eath M, De Grave W, Dornan T. 2016. How do clinicians become teachers? A communities of practice perspective. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 21(5):991–1008. doi: 10.1007/s10459-016-9674-9.

- Cantillon P, Dornan T, De Grave W. 2019. Becoming a clinical teacher. Acad Med. 94(10):1610–1618. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002403.

- Creswell JW. 2014. Educational research: planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. 4th ed. Boston (MA): Pearson.

- Cristancho S, Goldszmidt M, Lingard L, Watling C. 2018. Qualitative research essentials for medical education. Singapore Med J. 59(12):622–627. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2018093.

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. 2014. Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Acad Med. 89(11):1446–1451. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000427.

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. 2016. Amending Miller’s Pyramid to include professional identity formation. Acad Med. 91(2):180–185. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000913.

- Graham R. 2018. The career framework for university teaching: background and overview. London: Royal Academy of Engineering.

- Hofstede G. 2007. A European in Asia. Asian J Soc Psychol. 10(1):16–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-839X.2006.00206.x.

- Jarvis-Selinger S, Pratt DD, Regehr G. 2012. Competency is not enough. Acad Med. 87(9):1185–1190. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182604968.

- Kegan R. 1982. The evolving self: problem and process in human development. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press.

- Monrouxe LV, Rees CE, Dennis I, Wells SE. 2015. Professionalism dilemmas, moral distress and the healthcare student: insights from two online UK-wide questionnaire studies. BMJ Open. 5(5):e007518. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007518.

- Murakami M, Kawabata H, Maezawa M. 2009. The perception of the hidden curriculum on medical education: an exploratory study. Asia Pac Fam Med. 8(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1447-056X-8-9.

- Nishigori H, Harrison R, Busari J, Dornan T. 2014. Bushido and medical professionalism in Japan. Acad Med. 89(4):560–563. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000176.

- O’Sullivan PS, Irby DM. 2011. Reframing research on faculty development. Acad Med. 86(4):421–428. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820dc058.

- O’Sullivan PS. 2019. What questions guide investing in our faculty? Acad Med. 94(11S):S11–S13. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002910.

- Sherbino J, Snell L, Dath D, Dojeiji S, Abbott C, Frank JR. 2010. A national clinician–educator program: a model of an effective community of practice. Med Educ Online. 15(1):5356. doi: 10.3402/meo.v15i0.5356.

- Soemantri D, Findyartini A, Greviana N, Mustika R, Felaza E, Wahid M, Steinert Y. 2023. Deconstructing the professional identity formation of basic science teachers in medical education. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 28(1):169–180. doi: 10.1007/s10459-022-10150-6.

- Steinert Y, McLeod PJ, Boillat M, Meterissian S, Elizov M, Macdonald ME. 2009. Faculty development: a ‘field of dreams’? Med Educ. 43(1):42–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03246.x.

- Steinert Y, O’Sullivan PS, Irby DM. 2019. Strengthening teachers’ professional identities through faculty development. Acad Med. 94(7):963–968. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002695.

- Triemstra JD, Iyer MS, Hurtubise L, Poeppelman RS, Turner TL, Dewey C, Karani R, Fromme HB. 2021. Influences on and characteristics of the professional identity formation of clinician educators: a qualitative analysis. Acad Med. 96(4):585–591. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003843.

- van Lankveld T, Schoonenboom J, Kusurkar R, Beishuizen J, Croiset G, Volman M. 2016. Informal teacher communities enhancing the professional development of medical teachers: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 16(1):109. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0632-2.

- van Lankveld T, Thampy H, Cantillon P, Horsburgh J, Kluijtmans M. 2021. Supporting a teacher identity in health professions education: AMEE Guide No. 132. Med Teach. 43(2):124–136. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1838463.

- Wahid MH, Findyartini A, Soemantri D, Mustika R, Felaza E, Steinert Y, Samarasekera DD, Greviana N, Hidayah RN, Khoiriyah U, et al. 2021. Professional identity formation of medical teachers in a non-Western setting. Med Teach. 43(8):868–873. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2021.1922657.