Abstract

Purpose

We examined whether medical students’ opinions on the acceptability of a behaviour were influenced by previously encountering a similar professionally challenging situation, assessed the magnitude of effect of ‘experience’ compared to other demographic factors which influence medical students’ opinions, and evaluated whether opinions regarding some situations/behaviours were more susceptible to ‘experience’ bias?

Methods

Confidential, on-line survey for medical students distributed to Australian and New Zealand (AUS/NZ) medical schools. Students submitted de-identified demographic information, provided opinions on the acceptability of a wide range of student behaviours in professionally challenging situations, and whether they had encountered similar situations.

Results

3171 students participated from all 21 Aus/NZ medical schools (16% of registered students). Medical students reported encountering many of the professionally challenging situations, with varying opinions on what was acceptable behaviour. The most significant factor influencing acceptability towards a behaviour was whether the student reported encountering a similar situation. The professional dilemmas most significantly influenced by previous experience typically related to behaviours that students could witness in clinical environments, and often involved breaches of trust.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate the relationship between experience and medical students’ opinions on professional behaviour- the ‘Schweitzer effect’. When students encounter poor examples of professional behaviour, especially concerning trust breaches, it significantly influences their perception of the behaviour. These results highlight the importance of placing students in healthcare settings with positive professional role modelling/work cultures.

Example is not the main thing in influencing others; it is the only thing

Albert Schweitzer

Introduction

Medical educators have long recognised the change in identity that characterises the transformation from medical student to health professional, but it is only in the last few decades that terms such as professional identity formation, and hidden/informal curriculum, have been constructed to try to explain and define the nature and types of influences through which this occurs.

Practice points

Medical students report encountering a wide range of professionally challenging situations, and have varying opinions on acceptable professional behaviours

Although medical students’ opinions on professional behaviours are influenced by their demography, the most significant factor influencing the acceptability towards a behaviour was whether the student reported encountering a similar professional dilemma

Students appear to be susceptible to normalising counter productive work behaviours, particularly those related to breaches of trust

By placing students in toxic work culture environments with poor role models, we may inadvertently enable healthcare systems to perpetuate poor professional behaviour

Although there is a relatively large body of knowledge examining the effects of the formal, informal, and hidden curricula on medical students (Birden et al. Citation2013; Lawrence et al. Citation2018; Sarikhani et al. Citation2020), there have been comparatively few studies (Reddy et al. Citation2007; Arora et al. Citation2008; Dyrbye et al. Citation2010; Ginsburg and Lingard Citation2011; Kulac et al. Citation2013; Hendelman and Byszewski Citation2014; Fargen et al. Citation2016; Passi and Johnson Citation2016; Franco et al. Citation2017; Monrouxe and Rees Citation2012; Monrouxe et al. Citation2017a; Ainsworth and Szauter Citation2018; Mak-van der Vossen et al. Citation2018; Shaw et al. Citation2018) that have been designed to assess how students develop their opinions on the norms of professional behaviour. The Professionalism of Medical Students (PoMS) study was designed as a body of research to examine which factors influenced the opinions of Australian/New Zealand based medical students on a wide range of professionalism scenarios. Publications arising from the PoMS have shown that medical students’ opinions on professional behaviours are influenced by their gender, and to a lesser extent their stage in the medical course, type of medical school entry, and country of their medical school (Australia compared to New Zealand) (McGurgan et al. Citation2020). Medical students’ opinions on professionalism dilemmas related to patient safety appear to show a ‘professional identity effect’; students’ opinions aligned more with qualified doctors compared to the general public as they progressed through the course (McGurgan et al. Citation2022a). Conversely for alcohol/substance misuse dilemmas, the students’ opinions suggest generational influences rather than health care cultural norms are the dominant influence (McGurgan et al. Citation2022b).

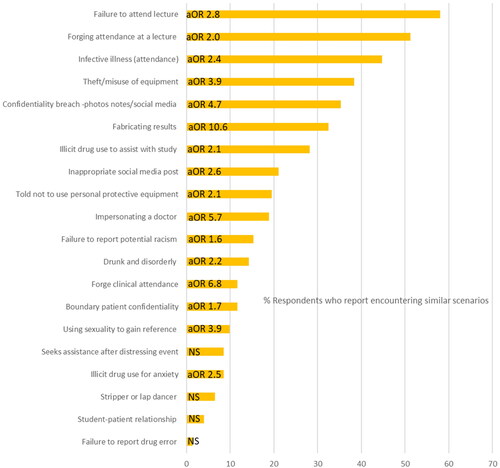

The PoMS medical student surveys also revealed that students reported encountering a wide variety of the professionally challenging situations covered in the survey (), with varying opinions on what was acceptable behaviour for many of the scenarios. A few studies have explored whether medical students previously observing and/or participating in unprofessional behaviours influences the perceived acceptability of the behaviour, however the studies which have looked at this most closely (Reddy et al. Citation2007; Kulac et al. Citation2013; Franco et al. Citation2017) have all been of limited size and scale. In view of this, we decided to analyse the PoMS data to examine whether medical students’ opinions on the acceptability of a behaviour were influenced by previously encountering a similar professionalism dilemma/professionally challenging situation. Secondary aims were to assess the magnitude of effect of experience compared to the other demographic factors which appear to influence medical students’ opinions, and determine whether students’ opinions on some professional behaviours are more susceptible to experience bias?

Figure 1. Ranked bar chart for proportion of medical student respondents (%) who reported encountering scenarios similar to the vignettes’ themes (with adjusted odds ratio for effect this had on modifying their opinion on the acceptability of the behaviour described).

Key: NS = Not significant, aOR = Adjusted odds ratio.

Methods

Design, ethics, setting, and participants

This study was an international, multicentre, prospective, cross-sectional survey. Ethical approval was obtained from University of Western Australia (HREC RA/4/1/8014). We used a convenience sampling approach to survey medical students in Australia and New Zealand (NZ). The methods and results of the medical student data, and validation of the survey instrument have been previously described in the Medical Students’ Opinions on Professional Behaviours paper, referred to henceforth as the PoMS-I study (McGurgan et al. Citation2020).

Survey instrument

The surveys used in the PoMS research covered a wide variety of professionally challenging situations pertinent to medical students (McGurgan et al. Citation2020). The themes included honesty, confidentiality, patient safety and respect, professional boundaries, reporting concerns, drug/alcohol misuse, social media, personal integrity, and wellbeing. The survey is included in Supplementary Appendix A; survey scenarios relating to the professionalism dilemmas/themes along with their contextual variables are described in .

Table 1. Comparison of factors that influence medical students’ responses to the PoMS scenarios.

The scenarios were constructed to encourage participants to reflect on the acceptability of behaviours which ranged from serious professionalism breaches to positive examples of professional behaviour. All scenarios ended with the sentence ‘This student’s behaviour is … ’. Respondents gave their opinions on ‘acceptability’ using a four-point Likert scale, with no option for equipoise. This methodology has been used in other large scale national studies (Finnegan) and Gawronski’s highly cited multinomial CNI model, which quantifies sensitivity to consequences, sensitivity to moral norms, and the general preference for inaction over action in responses to moral dilemmas. Participants were also asked if they had encountered a similar real-life situation previously. Students had the opportunity to provide free text comments; analysis of these are not included in this paper.

Although the survey was anonymous, participants were asked some questions about their background, specifically gender, type of course entry (undergraduate or postgraduate), and year level in medical school. Medical students were classified as ‘junior’ if they were in the first 2 years of a postgraduate entry course or in years 1 to 3 for an undergraduate course; by default, senior students were in the latter years of these courses.

With the exception of question 12, each scenario had 2 versions (vignettes) that contained a contextual variable identified a priori using the modified Delphi approach (McGurgan et al. Citation2020). For example, the protagonist in the scenarios could be either a junior or senior student, or working with different health professionals. Likewise, the context of the scenario could alter from agreeing/not agreeing to perform a procedure or attending/not attending a clinical placement. The online survey (SurveyMonkey Inc., San Mateo, California) was designed such that each participant received a random version of each scenario to allow for the comparison of the contextual variables. This provided a means of analysing whether respondents were influenced by unconscious bias; that is, whether the seniority, gender, or type of health professional involved influenced the students’ opinions on the acceptability of the behaviour.

Data and statistical analysis

Likert scale responses were combined into binary categories of all ‘acceptable’ responses against all ‘unacceptable’ responses and summarized using frequency distributions. The survey design enabled the comparison of 2 types of variables: the first being the participants’ demographic characteristic- gender, medical school entry type (undergraduate versus post-graduate) and country, student background (domestic versus international), student seniority. The second type of variable was the randomized contextual variable within most of the scenarios, for example, the protagonist attending or not attending a clinical placement after a recent illness.

Due to the development and use of a novel survey instrument, the authors analysed the survey’s reliability (internal consistency) in measuring professionalism opinions. Cronbach α was calculated (α = 0.716), consistent with a high (α > 0.7) construct validity and internal consistency (Taber Citation2018).

The χ2 or Fisher exact test was used to compare responses for the demographic variables. The contextual variables within the scenarios, and whether the student had encountered a similar situation/dilemma were assessed using logistic regression analysis with adjustment for demographic characteristics e.g. gender, medical school entry type (undergraduate versus post-graduate) and country, student background (domestic versus international), student seniority.

Null and blank responses were excluded for all questions, as were ‘prefer not to say’ responses for gender. Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Figures in the tables provided may not add up to 100% because of rounding (nearest decimal place), and totals may vary because of some participants not completing all of the questions or, for example, using option ‘prefer not to specify’ for gender question. SPSS Statistics 24 (IBM Corp.) was used for data analysis, and a p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The participation of all Australian and New Zealand medical schools resulted in a large numbers of student respondents (total 3171). Based on the Medical Student Statistics Annual Tables, this response rate represented 15.2% of enrolled Australian and 21.1% of NZ enrolled medical students (Medical Student Statistics Annual Tables Citation2017).

Demographic details of the student participants are presented in . There were lower numbers of responses from students in years 5 and 6 reflecting the number of courses with four-year post-graduate programs. Female students were significantly more likely to participate; 55.9% of respondents in the study were female, compared to the 51.1% of female medical students registered in the Medical Deans of Australia and New Zealand (MDANZ) database (p < 0.001). Respondents from NZ were more likely to be undergraduate entry (75.0 vs 42.4%, p < 0.001) and from more senior years in the medical course (61.1 vs 51.5%, p < 0.001) than their Australian counterparts.

Table 2. Demographic details of the PoMS medical student survey participants.a

Survey participants were asked if they had encountered real-life situations similar to the vignettes. shows the frequency ranking for students who reported encountering similar situations and illustrates the association between the proportion of students who reported encountering a scenario similar to the vignettes and the effect this had on influencing their overall opinions on the acceptability of the behaviour (calculated as an adjusted odds ratio, aOR). Any scenario which had greater than 10% of survey participants reporting that they had encountered a similar situation had a significant aOR indicating that the participant responses on whether they considered the behaviour described as ‘acceptable’ were influenced by this. The professional dilemmas that were most influenced by whether the participants had encountered a similar situation (aOR >5) typically related to behaviours that students could witness in the clinical environment, and concerningly often related to breaches of trust, e.g. fabricating results, impersonating a doctor, or forging clinical attendance.

Results displayed in demonstrate that although survey participant demographics appeared to influence some of their opinions on professionalism-related behaviours, students’ opinions on the acceptability of a behaviour were most significantly influenced by whether they reported previously encountering a similar professionalism dilemma/professionally challenging situation.

It was notable that professionalism dilemmas relating to alcohol/drug misuse (scenarios 11, 13 and 14) were the most consistently influenced by experience, i.e. whether the student respondents had encountered similar situations. In these contexts, students who stated they had previously encountered a similar situation were at least twice as likely to consider the alcohol/drug misuse situation as being ‘acceptable’. No other demographic factor (e.g. gender, student seniority) had a similarly pervasive effect on opinions towards drug/alcohol misuse ().

Respondents who stated that they had encountered situations related to a senior medical student fabricating patients’ results (scenario 1) had the largest effect on modifying opinions on acceptability; these respondents were at least ten times more likely to consider this sort of behaviour as being acceptable. Likewise, students who stated that they had encountered situations similar to the scenarios which described using social media to make derogatory comments about either obese or Indigenous people (scenario 9) were at least 50% more likely to consider this as acceptable.

For other professionalism themes, the effect on students’ opinions being influenced by whether they had encountered similar situations to the scenarios were less consistent. Survey participants who reported encountering ‘failure to report’ type situations (Scenarios 16 and 20) or looking up a spouse’s laboratory results (scenario 10) had variable effects on influencing opinions regarding whether this behaviour would be acceptable ().

Students who reported encountering similar situations to where the protagonist did not follow appropriate patient-safety related professional behaviours, such as attending a clinical placement despite a recent illness (scenario 4), or performing a minor surgical procedure without appropriate PPE (scenario 6), were at least twice as likely to consider these actions as being acceptable. Conversely, there was no evidence that students who had previously encountered similar situations to the scenarios that described the protagonist doing the ‘right thing’ had their opinions modified. For example, seeking assistance after a distressing event (scenario 12), not attending a placement when unwell, and not proceeding with a minor surgical procedure if told unable to use PPE.

Discussion

This is the first study to survey medical students from all Australian and New Zealand schools for their opinions on professionally challenging situations, and examine the factors which may influence these, specifically whether previously encountering a professionally challenging situation influences opinions on the acceptability of the behaviour. With over 3000 participants from two countries, covering a wide range of professionalism dilemmas and contextual variables, the PoMS results establish the types of professional behaviours which are most influenced by lived experience, and the magnitude of the effect ().

Regarding possible limitations, similar to other large surveys, we used a convenience sampling methodology (Dyrbye et al. Citation2010; Monrouxe et al. Citation2015; Finnegan and Gauden Citation2016). Although there were more female respondents (55.9% respondents), we corrected for this and other demographic characteristics by using adjusted regression analysis. The large sample size afforded a high precision; approximately 2% margin of error and 80% power to detect a difference of 3–5% between group proportions when the ‘acceptable’ opinions in the reference group were between 0.1 and 0.4 with an alpha level of 0.05.

The initial aims of PoMS study were to examine the opinions of Australian and NZ medical students on a range of professionalism scenarios, determine the relative frequency of participants encountering similar situations, and explore the role of context and demographic factors in influencing students’ opinions. As such, we cannot determine from this study whether students reporting having encountered a scenario were intrinsically different from students not encountering these. The survey was structured to minimise framing bias (Hodgkinson et al. Citation1999) by always asking the question ‘have you encountered a scenario like this’ after asking the respondents’ opinions on the acceptability of the protagonist’s behaviour. Analysis of the results from the two scenarios (4 and 6) which contained vignettes with diametrically opposing protagonist behaviours implies that framing effects were negligible. The effect of prior experience on participants’ opinions on acceptability was predicated on whether the behaviour was positive or negative.

The PoMs surveys used a third-party perspective to minimise respondents’ social desirability bias (Lavrakas Citation2008). Whilst asking participants opinions on the ‘acceptability’ of the protagonist’s behaviour using Likert scales could be considered too positivist/empirical an approach for the complexities of professional behaviours, many psychological studies of human behaviour have used and validated similar approaches (Wallace et al. Citation2005; Gawronski et al. Citation2017).

‘Acceptability’ is a fundamental, albeit amorphous principle used in a wide variety of fields from logic to philosophy (Michalos Citation1971; Gabbay et al. Citation2010; Sekhon et al. Citation2017). The caveat to using this criterion is that our results are limited to opinions on the acceptability of certain behaviours, and do not indicate whether the medical students would engage in these behaviours. Previous PoMS research (McGurgan et al. Citation2022a) found that medical students’ opinions transitioned to align more with the attitudinal norms of qualified doctors’ professional behaviours as they progressed through the course. Monrouxe et al. (Citation2017a) characterised the different models of ethical judgment as two broad categories- the ethics of conduct and the ethics of character. Conduct ethics is influenced by people acting within rules/norms (deontological) or focussing on the outcome (consequentialism). Virtue (character) ethical decision making relies on the individual’s perception of self to set the boundaries for what they do. Greene’s dual-process theory of moral judgment (Gawronski) asserts that both emotional and cognitive processes contribute jointly to moral decision making. Survey participants could have determined the protagonists’ behaviours as being acceptable (or not) using any of the forementioned models. However whichever decision making model that may have been applied, the largest meta-analysis that has attempted to quantify the correlation between attitudes and subsequent behaviour showed a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient r of 0.41 (CI 0.407–0.413), which is deemed relatively large by social psychology metrics (Wallace et al. Citation2005).

Analysis of the results of the PoMS surveys demonstrated that the most significant and pervasive factor influencing the perceived acceptability towards a behaviour was whether the student reported encountering a similar professional dilemma. The psychological literature has studied the relationships between environment, attitudes, and behaviour. According to Lewin (Lewin et al. Citation2019), behaviour (B) is intrinsically linked to the person (P) and their environment (E); B = f(P,E). Large meta-analyses of attitude-behaviour relationships (Wallace et al. Citation2005; Glasman and Albarracin Citation2006) demonstrate the importance of ‘experience’ with the attitude object as being pivotal. However, the relationship between medical students’ opinions on professional behaviours and whether these are influenced by previous experience has not been a major focus of medical education research to date (Reddy et al. Citation2007; Kulac et al. Citation2013; Franco et al. Citation2017).

Professional identity formation (PIF) can be viewed as a constructivist, social paradigm. Opinions on professional behaviours will be influenced by the individual’s level of PIF and their environment’s culture (Monson 2023). Authors such as Monrouxe and Bebeau and have demonstrated that cultures (which encompass norms, behaviours, beliefs, and customs) have a major effect on PIF at the individual, local and national level (Monrouxe and Rees Citation2012; Monrouxe et al. Citation2015; Monrouxe et al. Citation2017b; Bebeau and Monson Citation2012). To promote the formation of a ‘good physician’ Cruess et al. (Citation2014) posit:

that selection to medical school should target non-academic attributes such as emotional intelligence;

the concept of PIF should be embedded in all medical education activities; ‘being’ rather than just ‘doing’;

appreciating the importance of social enculturation into medicine, in particular how students develop their concepts towards the norms of health professional behaviour.

Regarding the latter point, the celebrated polymath doctor Albert Schweitzer stated that ‘Example is not the main thing in influencing others; it is the only thing’ (Byers Citation1996). Although previous PoMS and other research shows that there are other factors influencing medical students’ opinions on professionalism behaviours, this paper demonstrates that lived experience/example appears to be the most dominant factor.

Medical educators have long recognised the influences that culture and environment have on students and qualified doctors (Lesser et al. Citation2010; Goldie Citation2012; Birden et al. Citation2013; Passi et al. Citation2013; Fargen et al. Citation2016; Hodges et al. Citation2019). In terms of social enculturation to medicine, medical schools are the formative crucibles of professional identity, where students are influenced by a myriad of factors – on a spectrum from extremely positive to negative in terms of professional behaviours (Rees et al. Citation2013; Carmody et al. Citation2015; McGurgan et al. Citation2020). These have been grouped into the formal, informal, and hidden curricula. The hidden/informal curriculum has strong consilience with Bandura’s social cognitive theories (Bandura Citation1986); students are highly motivated to learn behaviours and ways of being that look successful to them.

As noted in the Introduction, previous surveys have demonstrated attitudinal relationships between medical student observation and/or participation in unprofessional behaviour (Reddy et al. Citation2007; Kulac et al. Citation2013; Franco et al. Citation2017); medical students were more likely to perceive unprofessional behaviour as being ‘acceptable’ if the student had either observed or participated in the activity. However, these studies were characterised by relatively small numbers of participants (<300) and used simple behaviour descriptors which lacked contextual nuances (Reddy et al. Citation2007; Kulac et al. Citation2013; Franco et al. Citation2017). Our results confirm the intrinsic relationship between experience and opinions regarding professional behaviours; which we term the ‘Schweitzer effect’. Compared to the other factors (gender, student seniority in the course, type of medical school entry, and country) that were analysed in the PoMS data, students reporting encountering a similar situation had the largest effect on determining how acceptable they would consider the protagonists’ behaviour.

The implications of the Schweitzer effect are considerable; our results indicate that the professional dilemmas that were most significantly influenced by whether the participants had encountered a similar situation (aOR >5) typically related to behaviours that students could witness in the clinical environment, and concerningly often related to breaches of trust, e.g. fabricating results, impersonating a doctor, or forging clinical attendance. This further underscores the importance of ensuring that students are placed in clinical environments and work with health professionals that model good standards of professional behaviours (Passi and Johnson Citation2016). The PoMS data also shows that medical students appear to be more heavily influenced by encountering poor examples of professional behaviours than exemplars. This was most clearly demonstrated in the two survey scenarios which were designed such that the protagonist would carry out diametrically opposite behaviours in each vignette; scenario 4 asked respondents their opinions on whether the medical student protagonist should attend/not attend a clinical placement within 24-h of experiencing gastroenteritis symptoms, and scenario 6 explored opinions on the acceptability of the student protagonist either performing/or not performing a minor surgical procedure if their supervisor states that wearing protective equipment (gloves) was unnecessary. The medical students’ opinions were notably consistent; for the survey participants responding to the vignettes which had the protagonist displaying exemplary professional behaviours, for example not attending a clinical placement when recently unwell/refusing to perform surgery without PPE, there was no effect on whether the student respondent had encountered a similar situation. However, if for the same scenario, the protagonist’s behaviour was a negative professional behaviour, for example, attending the placement/performing surgery without PPE, respondents who reported encountering a similar situation were twice as likely to consider this as being ‘acceptable’.

Much of the recent research on human decision making and behaviour has come from the discipline of behavioural economics. Kahneman, Tversky, Thaler and Sunstein’s research findings (Thaler and Sunstein Citation2008; Kahneman Citation2011; Tversky et al. Citation2018) generally support Haidt’s description of human decision making- the emotional tail wags the rational dog (Haidt Citation2001). There are increasing numbers of studies examining the unconscious bias and heuristics which influence medical decision making (Blumenthal-Barby and Krieger Citation2015; Klein and McColl Citation2019). Loewenstein used the term ‘empathy gap’ to describe the bias through which people underestimate how much their emotional states/experience influences their attitudes, preferences, and behaviours (Loewenstein Citation2005). Tavris and Aronson’s research and review of the literature (Tavris and Aronson Citation2007) demonstrate that dissonance theory has powerful implications for long-term behaviour. Once we have formed an opinion, we become susceptible to self-justification and confirmation biases; we are more likely to look out for, notice and remember anything which confirms opinions that we already hold (Laurin Citation2018).

Despite the obvious benefits of placing students with positive role models, working in well-functioning clinical environments, most contemporaneous data demonstrates that this is a difficult goal to achieve. The largest international study to analyse the prevalence of harassment and discrimination in medical training (Fnais et al. Citation2014) found that the pooled prevalence for harassment and discrimination was 59.4% (n = 51 studies, 38,353 trainees, 95% CI: 52.0%–66.7%;). The Medical Board of Australia’s 2022 annual medical training survey provides contemporaneous data from the Australian health care system (Medical Board Australia Citation2022). With more than 50% of doctors in training participating (n = 23,000), they found that 30/22% of respondents respectively had either witnessed/experienced bullying, discrimination, or harassment in their workplace that year. More than 30% of respondents stated that the person responsible for these behaviours was their supervisor, and the majority would not report the issue. Given this paper’s findings on how students’ opinions are unfortunately susceptible to normalising unprofessional behaviours, in particular those related to breaches of trust, e.g. fabricating results, impersonating a doctor, or forging clinical attendance, it seems likely that by placing students in the toxic work culture environments described above, we may be unwittingly enabling a system that perpetuates poor professional behaviour.

Westbrook et al.’s and others’ research on the prevalence and impacts of unprofessional behaviour in the health workplace highlight the effects this has on both the individual’s and patients’ health and safety, and acknowledges that organisational cultures can normalise incivility (Cooper et al. Citation2019; Medisauskaite and Kamau Citation2019; Westbrook et al. Citation2021). Brennan’s (2020) systematic review on remediating professionalism lapses in medical students and doctors concludes with the depressing statement that there is a ‘paucity of evidence to guide best practices of remediation of professionalism lapses in medical education at all levels’ (Brennan et al. Citation2020). However, work by Searle and Rice as part of the UK Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats (CREST) on counterproductive work behaviour (CWB, which by definition includes unprofessional behaviours) uses an individual (bad apple), local (bad barrel), and organisational (bad cellar) perspective. They describe a push and pull factors framework to identify factors and potential solutions for dealing with CWBs (Searle and Rice Citation2018; Searle and Rice Citation2021). The psychological literature attests to the malleability of human behaviour, and hence organisational behaviours. In order to break the cycle of normalising unprofessional behaviours in healthcare settings, it is imperative that more focus is put on using the CREST and other evidence-based strategies for managing the individual, groups, and the organisation. This paper indicates that medical students encounter a wide variety of professionalism dilemmas and are influenced by them. It seems unlikely that we can fix poor professionalism in the healthcare settings if we continue to expose students to it, given their susceptibility to habituate and normalise counterproductive work behaviours. The ideal paradigm would be that students are not placed in toxic work culture environments. Acknowledging the realpolitik, we propose that those involved in medical education and clinical supervision should reconsider what tools and resources students are provided with to engage them in developing appropriate ethical reasoning and professional behaviours, and equip them to deal with the significant professionalism dilemmas they may encounter in healthcare settings.

Conclusions

This international survey’s results and analysis demonstrate that the optimistic assumption that medical students can be placed in clinical environments which have poor professionalism cultures but will manage to process these experiences in a positive way is fundamentally flawed. Instead, what we have termed the ‘Schweitzer effect’ explains that when students encounter poor examples of professional behaviour, particularly those related to breaching trust, it has a profound effect on how they come to perceive the nature of the behaviour, such that they are five times more likely to normalise these behaviours.

We hope our findings will inform those interested in medical education and/or professionalism of the factors influencing students’ opinions on professionalism behaviours, provide evidence for the importance of placing students in healthcare settings with positive professional role modelling and work cultures, and the need to adequately prepare students to identify and manage the complex group dynamics and CWB they will encounter. We need educational approaches and guidance that are much more sophisticated, and that engage students in strengthening their own ethical reasoning and moral standards, rather than expecting them to learn a theoretical best practice which may not be reflected by their supervisors or role models.

The fact that lived experience has such a significant influence on how medical students view professionalism dilemmas both challenges and provides a key mechanism towards improving the professional culture in healthcare environments.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.8 MB)Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the 3171 medical students who participated in the survey, and all of the Aus/NZ medical schools who agreed to distribute the surveys to their students. Dr Laura Fruhen, Senior Lecturer of Applied Psychology, UWA provided some advice on the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing or conflicts of interest to declare. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Paul McGurgan

Paul McGurgan, FRCOG, FRANZCOG, SFHEA, is a clinical academic. He is the Associate Dean of UWA Medical School (Student Matters), and theme lead for Personal and Professional Development in the UWA MD course. He chairs the Professional Behaviour Advisory Panel for UWA Faculty of Health Sciences. The PoMs research forms part of his PhD thesis on ‘What factors influence opinions about medical student professional behaviours?’

Katrina Calvert

Katrina Calvert, FRANZCOG, MHPEd, MRCOG, is a consultant obstetrician and director of post-graduate medical education in the state’s largest obstetric and gynaecology hospital, KEMH. Katrina has a special interest in simulation, feedback, and health professional wellbeing. She was an inaugural member, and deputy chair of the RANZCOG Wellbeing Working Group.

Antonio Celenza

Antonio Celenza, MClinEd, FACEM, FRCEM, is an academic emergency physician and was director of the MD program at the University of Western Australia for 8 years with leadership roles in curriculum design, teaching delivery, assessment, and evaluation. He continues to have clinical, educational and research roles as Professor and Head, Division of Emergency Medicine at UWA.

Elizabeth A. Nathan

Elizabeth A. Nathan, RN, B.Sci, M.Biostats (Syd), is a biostatistician and Adjunct Senior Lecturer at UWA Division of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, based at King Edward Memorial Hospital. She has collaborated on many health care research projects applying a broad range of statistical methodologies.

Christine Jorm

Christine Jorm, MBBS(Hons) MD PhD FANZCA, is currently Adjunct Professor, School of Public Health, Sydney University. Christine’s PhD thesis explored why medical (doctor) culture resisted the imperatives of the safety and quality movement. Christine has broad experience as a clinician, policy maker, researcher and medical educator.

References

- Ainsworth MA, Szauter KM. 2018. Student response to reports of unprofessional behavior: assessing risk of subsequent professional problems in medical school. Med Educ Online. 23(1):1485432. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2018.1485432.

- Arora VM, Wayne DB, Anderson RA, Didwania A, Humphrey HJ. 2008. Participation in and perceptions of unprofessional behaviors among incoming internal medicine interns. JAMA. 300(10):1132–1134. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.10.1132.

- Medical Board Australia. 2022. Medical Training Survey [accessed April 2023]. https://www.medicaltrainingsurvey.gov.au/.

- Bandura A. 1986. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Bebeau MJ, Monson VE. 2012. Professional identity formation and transformation across the life span. In: McKee, A., Eraut, M. (eds), Learning trajectories, innovation and identity for professional development. Innovation and change in professional education, vol 7. Springer, Dordrecht. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-1724-4_7.

- Birden H, Glass N, Wilson I, Harrison M, Usherwood T, Nass D. 2013. Teaching professionalism in medical education: a Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) systematic review. BEME Guide No. 25. Med Teach. 35(7):e1252-1266–e1266. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.789132.

- Blumenthal-Barby JS, Krieger H. 2015. Cognitive biases and heuristics in medical decision making: a critical review using a systematic search strategy. Med Decis Making. 35(4):539–557. doi: 10.1177/0272989X14547740.

- Brennan N, Price T, Archer J, Brett J. 2020. Remediating professionalism lapses in medical students and doctors: a systematic review. Med Educ. 54(3):196–204. doi: 10.1111/medu.14016.

- Byers JQ. 1996. Brothers in spirit: the correspondence of Albert Schweitzer and William Larimer Mellon, Jr. New York, Syracuse University Press.

- Cooper WO, Spain DA, Guillamondegui O, Kelz RR, Domenico HJ, Hopkins J, Sullivan P, Moore IN, Pichert JW, Catron TF, et al. 2019. Association of coworker reports about unprofessional behavior by surgeons with surgical complications in their patients. JAMA Surg. 154(9):828–834. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.1738.

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. 2014. Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Acad Med. 89(11):1446–1451. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000427.

- Carmody D, Tregonning A, McGurgan P. 2015. A study of medical students’ experience of the hidden and informal curriculum in obstetrics and gynaecology. MedEdPublish. 5(3):1–12. doi: 10.15694/mep.2015.005.0003.

- Dyrbye LN, Massie FS, Jr., Eacker A, Harper W, Power D, Durning SJ, Thomas MR, Moutier C, Satele D, Sloan J, et al. 2010. Relationship between burnout and professional conduct and attitudes among US medical students. JAMA. 304(11):1173–1180. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1318.

- Fargen KM, Drolet BC, Philibert I. 2016. Unprofessional behaviors among tomorrow’s physicians: review of the literature with a focus on risk factors, temporal trends, and future directions. Acad Med. 91(6):858–864. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001133.

- Finnegan C, Gauden V. 2016. Medical student views of acceptable professional behavior: a survey. J Med Regul. 102(3):5–17. doi: 10.30770/2572-1852-102.3.5.

- Fnais N, Soobiah C, Chen MH, Lillie E, Perrier L, Tashkhandi M, Straus SE, Mamdani M, Al-Omran M, Tricco AC. 2014. Harassment and discrimination in medical training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 89(5):817–827. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000200.

- Franco RS, Franco CAG, Kusma SZ, Severo M, Ferreira MA. 2017. To participate or not participate in unprofessional behavior – Is that the question? Med Teach. 39(2):212–219. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1266316.

- Gabbay DM, Rodrigues O, Russo A. 2010. Revision, acceptability and context - theoretical and algorithmic aspects. Cognitive Technologies, Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; pp. I-X, 1-385. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-14159-1.

- Gawronski B, Armstrong J, Conway P, Friesdorf R, Hutter M. 2017. Consequences, norms, and generalized inaction in moral dilemmas: the CNI model of moral decision-making. J Pers Soc Psychol. 113(3):343–376. doi: 10.1037/pspa0000086.

- Ginsburg S, Lingard L. 2011. Is that normal?' Pre-clerkship students’ approaches to professional dilemmas. Med Educ. 45(4):362–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03903.x.

- Glasman LR, Albarracin D. 2006. Forming attitudes that predict future behavior: a meta-analysis of the attitude-behavior relation. Psychol Bull. 132(5):778–822. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.778.

- Goldie J. 2012. The formation of professional identity in medical students: considerations for educators. Med Teach. 34(9):e641-648–e648. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.687476.

- Haidt J. 2001. The emotional dog and its rational tail: a social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychol Rev. 108(4):814–834. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.4.814.

- Hendelman W, Byszewski A. 2014. Formation of medical student professional identity: categorizing lapses of professionalism, and the learning environment. BMC Med Educ. 14(1):139. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-139.

- Hodges, B, Paul, R, Ginsburg, S. 2019. Assessment of professionalism: from where have we come - to where are we going? An update from the Ottawa Consensus Group on the assessment of professionalism.Med Teach. 41(3):249–255. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1543862.

- Hodgkinson GP, Bown NJ, Maule AJ, Glaister KW, Pearman AD. 1999. Breaking the frame: an analysis of strategic cognition and decision making under uncertainty. Strat Mgmt J. 20(10):977–985. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199910)20:10<977::AID-SMJ58>3.0.CO;2-X.

- Kahneman D. 2011. Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Klein J, McColl G. 2019. Cognitive dissonance: how self-protective distortions can undermine clinical judgement. Med Educ. 53(12):1178–1186. doi: 10.1111/medu.13938.

- Kulac E, Sezik M, Asci H, Doguc DK. 2013. Medical students’ participation in and perception of unprofessional behaviors: comparison of preclinical and clinical phases. Adv Physiol Educ. 37(4):298–302. doi: 10.1152/advan.00076.2013.

- Laurin K. 2018. Inaugurating rationalization: three field studies find increased rationalization when anticipated realities become current. Psychol Sci. 29(4):483–495. doi: 10.1177/0956797617738814.

- Lavrakas PJ. 2008. Social desirability. Encyclopedia of survey research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Lawrence C, Mhlaba T, Stewart KA, Moletsane R, Gaede B, Moshabela M. 2018. The hidden curricula of medical education: a scoping review. Acad Med. 93(4):648–656. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002004.

- Lesser CS, Lucey CR, Egener B, Braddock CH, 3rd, Linas SL, Levinson W. 2010. A behavioral and systems view of professionalism. JAMA. 304(24):2732–2737. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1864.

- Lewin LO, McManamon A, Stein MTO, Chen DT. 2019. Minding the form that transforms: using Kegan’s model of adult development to understand personal and professional identity formation in medicine. Acad Med. 94(9):1299–1304. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002741.

- Loewenstein G. 2005. Hot-cold empathy gaps and medical decision making. Health Psychol. 24(4S):S49–S56. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.S49.

- Mak-van der Vossen M, Teherani A, van Mook W, Croiset G, Kusurkar RA. 2018. Investigating US medical students’ motivation to respond to lapses in professionalism. Med Educ. 52(8):838–850. doi: 10.1111/medu.13617.

- McGurgan P, Calvert KL, Nathan EA, Narula K, Celenza A, Jorm C. 2022a. Why is patient safety a challenge? Insights from the professionalism opinions of medical students’ research. J Patient Saf. 18(7):e1124–e1134. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000001032.

- McGurgan P, Calvert K, Nathan E, Celenza A, Jorm C. 2022b. Opinions towards medical students’ self-care and substance use dilemmas-a future concern despite a positive generational effect? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 19(20):13289. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192013289.

- McGurgan P, Calvert KL, Narula K, Celenza A, Nathan EA, Jorm C. 2020. Medical students’ opinions on professional behaviours: the Professionalism of Medical Students’ (PoMS) study. Med Teach. 42(3):340–350. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2019.1687862.

- Medical Student Statistics Annual Tables. 2017 [accessed 2023 Apr]. http://www.medicaldeans.org.au/statistics/annualtables/.

- Medisauskaite A, Kamau C. 2019. Does occupational distress raise the risk of alcohol use, binge-eating, ill health and sleep problems among medical doctors? A UK cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 9(5):e027362. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027362.

- Michalos AC. 1971. Acceptability and logical improbability. In The Popper-Carnap Controversy. Springer, Dordrecht. doi: 10.1007/978-94-010-3048-9_2.

- Monrouxe L, Shaw M, Rees C. 2017a. Antecedents and consequences of medical students’ moral decision making during professionalism dilemmas. AMA J Ethics. 19(6):568–577.

- Monrouxe LV, Bullock A, Tseng H-M, Wells SE. 2017b. Association of professional identity, gender, team understanding, anxiety and workplace learning alignment with burnout in junior doctors: a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open. 7(12):e017942. e017942. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017942.

- Monrouxe LV, Rees CE. 2012. It’s just a clash of cultures": emotional talk within medical students’ narratives of professionalism dilemmas. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 17(5):671–701. doi: 10.1007/s10459-011-9342-z.

- Monrouxe LV, Rees CE, Dennis I, Wells SE. 2015. Professionalism dilemmas, moral distress and the healthcare student: insights from two online UK-wide questionnaire studies. BMJ Open. 5(5):e007518–e007518. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007518.

- Monson V, Bebeau MJ, Faber-Langendoen K, Kalet A. 2023. Professionalism lapses as professional identity formation challenges. In: Kalet, A., Chou, C.L. (eds), Remediation in medical education. Springer, Cham. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-32404-8_13.

- Passi V, Johnson N. 2016. The impact of positive doctor role modeling. Med Teach. 38(11):1139–1145. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2016.1170780.

- Passi V, Johnson S, Peile E, Wright S, Hafferty F, Johnson N. 2013. Doctor role modelling in medical education: BEME Guide No. 27. Med Teach. 35(9):e1422-1436–e1436. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.806982.

- Reddy ST, Farnan JM, Yoon JD, Leo T, Upadhyay GA, Humphrey HJ, Arora VM. 2007. Third-year medical students’ participation in and perceptions of unprofessional behaviors. Acad Med. 82(10 Suppl):S35–S39. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181405e1c.

- Rees CE, Monrouxe LV, McDonald LA. 2013. Narrative, emotion and action: analysing 'most memorable’ professionalism dilemmas. Med Educ. 47(1):80–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04302.x.

- Searle RH, Rice C. 2018. Assessing and mitigating the impact of organisational change on counterproductive work behaviour: An operational (dis) trust based framework. Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats (CREST); [accessed April 2023]. https://crestresearch.ac.uk/resources/reports/cwb-full-report/.

- Searle RH, Rice C. 2021. Making an impact in healthcare contexts: insights from a mixed-methods study of professional misconduct. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 30(4):470–481. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2020.1850520.

- Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ. 2017. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv Res. 17(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2031-8.

- Shaw MK, Rees CE, Andersen NB, Black LF, Monrouxe LV. 2018. Professionalism lapses and hierarchies: A qualitative analysis of medical students’ narrated acts of resistance. Soc Sci Med. 219:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.10.009.

- Taber KS. 2018. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res Sci Educ. 48(6):1273–1296. doi: 10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2.

- Tavris C, Aronson E. 2007. Mistakes were made (but not by me): why we justify foolish beliefs, bad decisions, and hurtful acts. Orlando, FL, US: Harcourt.

- Thaler RH, Sunstein CR. 2008. Nudge: improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Tversky A, Shafir E, Lewis M, Kahneman D. 2018. The essential Tversky. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press.

- Wallace DS, Paulson RM, Lord CG, Bond CF. 2005. Which behaviors do attitudes predict? Meta-analyzing the effects of social pressure and perceived difficulty. Rev Gen Psychol. 9(3):214–227. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.9.3.214.

- Westbrook J, Sunderland N, Li L, Koyama A, McMullan R, Urwin R, Churruca K, Baysari MT, Jones C, Loh E, et al. 2021. The prevalence and impact of unprofessional behaviour among hospital workers: a survey in seven Australian hospitals. Med J Aust. 214(1):31–37. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50849.

- Sarikhani Y, Shojaei P, Rafiee M, Delavari S. 2020. Analyzing the interaction of main components of hidden curriculum in medical education using interpretive structural modeling method. BMC Med Educ. 20(1):176. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02094-5.