Abstract

Following Gellner, citizenship education has often been framed in terms of nationalism. This framing is supported by methodological nationalism that legitimizes nationalism as either functional (civic nationalism) or natural (ethnic nationalism). Based on a triangulation of qualitative and quantitative data, this study of the dynamics in the classes of a Dutch faculty of social professions highlights the disruptive impact of nationalism on citizenship education, spilling over to other courses as well. Ethno-nationalist discourses in Dutch media and politics as well as in multiculturalism approaches used in citizenship education fuel conflicts between non-migrant students and students with a migration background that disrupt education. It is argued that in globalized settings like these classes, a more viable approach to citizenship education would take an institutional instead of communitarian perspective.

Introduction

Following Ernest Gellner’s (Citation1983) argument that the development of industrial society requires homogeneity and identity formation on the national level, citizenship education has been understood as a prime instrument for achieving national homogenization and identity. However, Riyad Shahjahan and Adrianna Kezar (Citation2013) urge us not to take such nationalist understandings of education for granted and to leave assumptions of methodological nationalism behind. Their call resonates with a wider literature that questions methodological nationalism (e.g., Wimmer and Glick Schiller Citation2002). Is a nationalist framing of citizenship education still functional and adequate in the current context of globalization and transnationalism or has it even become counterproductive? The aim of this study is to contribute to our understanding of the contemporary impact of nationalism on citizen education.

This study has been carried out among students of social professions programmes at a Dutch university of applied sciences and highlights the destructive impact of nationalism, as it fuels polarization and disrupts education in class. The findings of interviews, focus groups and questionnaires among students and teachers in 2011 indicate1 that the dispersion of ethno-nationalist categories stemming from dominant discourses in Dutch media and politics as well as from dysfunctional diversity theories triggers ethno-nationalist conflicts in classes made up of students with diverse origins. An argument is made for notions of citizenship education that foster institutionally nested instead of communitarian identities.

Nationalism and education

Ernest Gellner (Citation1983) has conceptualized nationalism as a requirement of industrial society that needs translocal normalization and homogenization of uniform knowledge and discipline. Several studies have shown how the state fulfils this requirement by constructing ‘the nation’ and propagating national identity through public schooling, especially citizenship education (e.g., Bénéï Citation2005 and Citation2008; Bourdieu and Passeron Citation1990; Hahn Citation1998; Jaskulowski, Majewski, and Surmiak Citation2018).

However, other studies found that the effects of national identity constructions may be limited or even problematic. Students in Cluj (Romania) reproduce nationalist rhetorics in questionnaires, but without taking such rhetorics seriously in everyday life (Fox Citation2004). Some students in mainland China (Fairbrother Citation2003) and Japan (Parmenter Citation1999) resist such rhetorics. National identities clash with indigenous identities of Aymara students in Bolivia (Luykx Citation1998). Nationalist notions of ‘white’ and Christian Englishness emphasize differences with ethnic or racial minorities in English citizenship education (Gholami Citation2017). Moreover, education may also promote cosmopolitan instead of nationalist views, like in Israeli (Yemeni, Bar-Nissan, and Shavit Citation2014), Japanese (Saito Citation2011), Irish (Tormey Citation2006) and Norwegian (Osler and Lybaek Citation2014) education.

In her study on citizenship education in vocational schools in Berlin, Cynthia Miller-Idriss (Citation2009) found that teachers explicitly take an anti-nationalist approach against the backdrop of Nazi horrors in the past (see also Parmenter Citation1999 on Japan), but that does not keep some students from feeling attracted to nationalist views. Despite her constructivist positioning, however, she tends to naturalize students’ nationalist views. She makes no conceptual differentiation between citizenship, belongingness and national identity, which suggests that citizenship and belongingness require national identity.

Next, she does not address the question where these students get their nationalist ideas from, whereas her own material provides clues about those sources. Respondents referred to official nationalist framings of migrants who wound need ‘integration’ and to the recurrent use of national categories in German media, despite their civic outlook (Miller-Idriss Citation2009, 103). The teachers take an anti-nationalist stance associating ‘the nation’ with feelings of guilt, but thereby they keep notions of ‘the nation’ alive as something important.

Methodological nationalism and beyond

Miller-Idriss’ otherwise excellent work illustrates how difficult, but nevertheless indispensable, it is to escape from methodological nationalism (Jaskulowski, Majewski, and Surmiak Citation2018; Shahjahan and Kezar Citation2013). Andreas Wimmer and Nina Glick Schiller (2002, 302, italics mine) have defined methodological nationalism as ‘the assumption that the nation/state/society is the natural social and political form of the modern world’. That is when we take ‘nations’ as units of analysis for granted and assume them to be unitary actors within assumedly self-evident processes of nation-state building.

Methodological nationalist views are supported by trends in the literature on nationalism itself. As said, Ernest Gellner (Citation1983) saw nationalism as a functional requirement of modern industrial society. National identity would allow citizens to lead a meaningful life, enjoy civic rights and socialize themselves into a national community. This civic nationalism contrasts with an ethnic understanding of nationalism by, for example, Anthony Smith (Citation1986). ‘The nation’ preceded modern times and favoured the development of the state, he argued. Specific cultural characteristics would mark ‘the nation’. Individuals would adopt a national identity as they are born into a national community.

This conceptual distinction between civic and ethnic nationalism is useful to analyse cases of nationalism (see Dutch nationalism below), but risks legitimizing nationalism in a functionalist or naturalizing way. Civic nationalism risks functionalism: there is a modern necessity for ‘the nation’ so it will emerge. Ethnic nationalism risks naturalizing ‘the nation’: it has been there since ancient times thus it is normal and natural. In other words, ‘the nation’ has to be so it is, versus ‘the nation’ is so it has to be. However, with such a functionalist or normalizing legitimization, how can we maintain a critical distance towards ‘the nation’ and nationalism as well as towards their relations with education? Getting away from methodological nationalism in our approach is necessary to critically discuss the empirical relationship between nationalism and education. Several studies have fleshed out the convergence between institutions and nationalism (Goode and Stroup Citation2015), but very few have looked at the impact of nationalism on the functioning of institutions like education.

Regarding nationalism, the literature also distinguishes between elite nationalism and everyday nationalism. Scholars point at the ways in which elite nationalist claims are adopted, reworked and adapted by people in everyday life (Fox and Miller-Idriss Citation2008; Goode and Stroup Citation2015), highlighting ‘ordinary’ people’s agency. Anthony Smith (Citation2008) emphasized that everyday nationhood constructions need to be studied in interactions with official constructions of ‘the nation’. Discussing the influences of such official constructions in an encompassing way, i.e., not limited to teachers’ views, is important for understanding everyday nationalism among students. The main traits of official nationalist discourses in media and politics need to be outlined first.

Dutch ethno-nationalism

In the Netherlands, discourses in media and politics have taken an ethno-nationalist turn since 2000 (Scholten and Holzhacker Citation2009; Van Reekum Citation2012), manifested in many official practices, like the campaign for the revival of ‘Dutch norms and values’ by Prime Minister Jan Peter Balkenende (2002–2010). The assumed ‘threat’ to ‘Dutch national identity’ has become a major topic of national elections campaigns. Jan Willem Duyvendak (Citation2011) writes about a ‘thickening’ of ‘Dutch culture and identity’ and Semin Suvarierol (Citation2012) calls it ‘nation-freezing’, i.e., a particular and substantive definition of ‘the nation’ is imposed on individuals.

Paradoxically, however, the prime components of such ethno-nationalist notions are exactly civic and liberal values. Dominant constructions of ‘Dutchness’ portray progressive, civic and liberal values like emancipation, equal rights for homosexuals, sexual freedom, gender equality, individualism and tolerance as typically Dutch (Van Reekum Citation2012; Van Reekum and Duyvendak Citation2012). Universalistic civic values are transformed into particularistic ethnic building-blocks of ‘the Dutch nation’.

In this ethno-nationalization of civic values (Laegaard Citation2007), ‘the nation’ is opposed to those who are believed to threaten it (Halikiopoulou, Mock and Vasilopoulou Citation2013), particularly migrants with so-called ‘non-Western’ backgrounds. They are obliged to pass ‘civic’ integration exams that test their adoption of assumedly Dutch cultural traits (Suvarierol Citation2012). Contemporary ethno-nationalist constructions of an opposition between assumedly Dutch traits and those represented by migrants were made possible by the culturalization of migrants in multiculturalist discourses in the 1980s and 1990s (Siebers and Dennissen Citation2015; Duyvendak, Geschiere, and Tonkens Citation2016).

Official constructions of ‘the Dutch nation’ reflect typical ethno-nationalist traits, i.e., they are particularistic, substantive, deterministic and totalizing. Rogier van Reekum and Marguerite van den Berg (Citation2015) studied the incorporation of civic values into ethnic nationalism in parenting courses. Theirs is the only study that focuses on the role of Dutch ethnic nationalism in education. The current study contributes to filling this gap.

Research setting and methods

The research was carried out by the author, supported by assistants,2 at the faculty of social professions of a Dutch university of applied sciences in 2011. In 2008, the Equal Treatment Commission, the official Dutch tribunal for filing a discrimination complaint,3 found the faculty guilty of discriminating against two migrant staff members. The following unrest in the whole university caused its board to initiate a university-wide research project to get an overview of the overall role of ethno-migrant4 diversity in class and ethno-migrant inequality in study success. This article is based on a subproject that focused only on the faculty of social professions. It was singled out for an in-depth study because of the occurrence of conflicts between non-migrant and migrant students with a so-called ‘non-Western’ background5 in its classes. The subproject’s aim was to identify the dynamics and factors behind such conflicts that particularly emerged in citizenship education courses.

The faculty offered three programmes: socio-cultural education and training CMV (Cultureel-Maatschappelijke Vorming), socio-pedagogical work SPH (Sociaal-Pedagogische Hulpverlening) and social work and services MWD (Maatschappelijk Werk en Dienstverlening). The CMV programme instructed students to develop cultural activities with a social development perspective. SPH and MWD trained social workers to work with, respectively, groups and individuals, both have full-time and part-time programmes. Only a few of CMV’s 180 students had a migration background. Over 20% of SPH’s 800 students had a (mostly ‘non-Western’) migration background, whereas over 75% of MWD’s 730 students had such a background (data provided by the programme coordinators in 2011).

Citizenship education was provided in the courses Ethics and Citizenship, and Diversity and Identity. They focused on the basics of civic behaviour, social responsibility, democracy, and politics as well as on ethical problems that social workers are confronted with in their work. Driven by the unrest of 2008, diversity became one of the main topics of citizenship education. A complete minor programme (30 ects) was dedicated to diversity. The main focus was on diversity cases students may find difficult to deal with, but also some diversity theories were discussed (see below).

The author and an assistant studied relevant documents and held seven focus group meetings with either students or teachers. Applying non-purposive sampling, we put a message on the intranet to invite them to participate. We also organized discussions in five classes that showed interest in the subject and discussed preliminary findings in all five teachers’ teams. These meetings were spread over the various programmes and included both migrant and non-migrant respondents. Teachers and students who often took the floor in these meetings were invited for an individual interview (purposive sampling). In total, 24 interviews were conducted with the director, four programme coordinators and with students and teachers. We tried to spread student and teacher respondents over relevant categories, like the various programmes and ethno-migrant backgrounds (see ).

Table 1. Interview respondents and backgrounds.

Table 2. Variables, items and reliability students’ questionnaire.Table Footnotea

Table 3. Variables, items and reliability teachers’ questionnaire.Table Footnotea

The interview and group meeting scripts focused on general dynamics in class, experiences with ethno-migrant diversity, topics that produce tensions and events related to backgrounds. Such issues were questioned in an ethnographic sense asking about when, context, who were involved, who said and did what, how it evolved, what were the consequences, etc. For qualitative data analysis, Matthew Miles and Michael Huberman’s (Citation1994) steps of data reduction (selective, open and axial coding), data display and drawing conclusions were used, starting with interview topics as initial codes.

These qualitative data served as input for two questionnaires using non-purposive sampling. The questionnaire for teachers had an N = 58 that represented 66% of the teachers. They were spread over the programmes, 50 had a non-migration background and eight a migration background with various origins. For students, 42 relevant questions were included in a university-wide questionnaire as part of the wider project on study success (see above). Of the social professions faculty, 110 students responded (CMV 15, MWD 38 and SPH 57), i.e., the response rate was 6.4%. Of those 110 students, 26 had a migration background with various origins. Questions were about what actually happened in class, not about personal views or opinions.

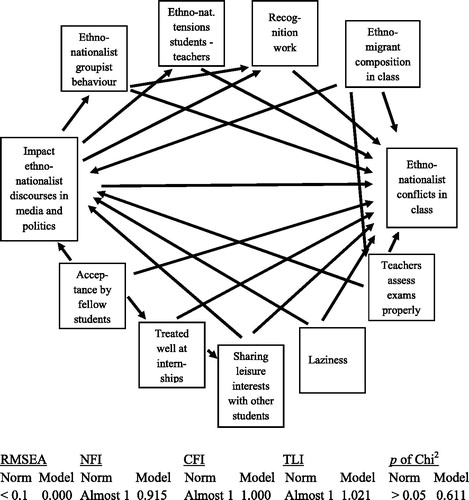

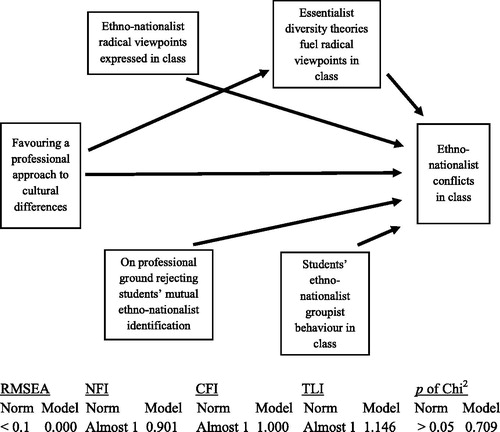

For quantitative data analysis, AMOS structural equation modelling software version 22 was used. We applied two categories of fit indices (Curşeu et al. Citation2007, 132). Absolute fit indices show the general fit between the theoretical model and the data. Relative fit indices compare the tested model with the null model. The null model suggests that the variables in the model are mutually independent and that there is no covariance among the variables (Widaman and Thompson Citation2003). The indices used here measure the degree to which constructed models fit real relations between variables in the data file. Constructed models ( and ) match the norms set for such fit (see Browne and Cudeck Citation1993; Widaman and Thompson Citation2003).

The response rate of the students’ questionnaire is quite low, as in most university-wide questionnaires without a communication campaign addressing a particular faculty. Numbers of respondents are limited, but for data analysis the significance threshold of p<.05 was applied. Validity is mainly ensured through data triangulation of various stakeholders, of various research instruments and of various kinds of data on the same subjects. All findings presented below are supported by several data sources, including quantitative and qualitative data, unless indicated otherwise.

Ethno-nationalist conflicts in class

Three SPH students accounted of the following event that occurred in a citizenship education class. A film was shown about homosexuality when a male student with a Moroccan background started to make vomiting gestures to express his disgust of homosexuality. He typified it as ‘dirty’, as ‘an illness’. Thereupon, a female bi-sexual student with a non-migrant background became angry and said that she felt offended and hurt by his comments. Other non-migrant students started to back her up, migrant students did the same with the ‘Moroccan’ student and fierce accusations and insults were exchanged between the groups. This conflict had continued for a year already and recurrently disrupted education.

Conflictive practices like these included hate and threat emails, sometimes the police had to be called in. It is not easy to assess the frequency of occurrence of such conflicts precisely, but 19.1% of the teachers indicated in their questionnaire that such conflicts occurred in half or more of the classes in which they teach. Half of them answered that such conflicts and tensions took place in a minority of their classes. Thus, most likely these conflicts and tensions happened in a substantial minority of the faculty’s classes.

A comparison of the focus group and interview data on those conflicts revealed that they resemble the ethno-nationalist characteristics discussed above: deterministic, totalizing, particularistic and substantive. First, students and teachers indicated that in these conflicts students socialize in subgroups on an ethno-nationalist basis. Members of those subgroups identify each other in ethno-nationalist terms. Then, they call each other ‘Dutch’, ‘Turk’, ‘Surinamese’, ‘Moroccan’ and so on and often address each other as representatives of their ethno-nationalist subgroup. Identities like sex and gender also play a role in such incidents, but subordinated to the basic ethno-nationalist ones.

Second, these conflicts have ‘Dutch’ versus ‘non-Dutch’ as the main opposition and sustain themselves in a deterministic way, i.e., independently from students’ intentions. All three students involved in the conflict discussed above told us that they very much regret these conflicts, but are unable to stop them. They feel that those ethno-nationalist subgroup formations, categorizations and polarizations are imposed on them.

Third, such conflicts tend to become totalizing. They are mostly sparked in citizenship education but continue in other courses as well. Students and teachers told us that, when a student enters in these classes, everyone watches whether s/he sits with the subgroup s/he is ascribed to. This polarization harms the learning process since a student brings forward views s/he is supposed to voice as ethno-nationalist group member instead of those s/he learned at school, teachers said.

Fourth, the qualitative data on these conflicts show that substantive and particularistic characteristics are attributed to and represented by members of these ethno-nationalist groups. ‘Dutch’ students bring forward civic values like tolerance, liberal views on sexuality and gender roles, emancipation, equal rights, sexual freedom and law abiding, whereas ‘Turkish’, ‘Moroccans’ and ‘Antilleans’ students voice opposite views. The ‘Dutch’ particularistic appropriation of universal civic and liberal values (see above) forces other ethno-nationalist groups to either take illiberal and uncivic views or to say that many ‘Dutch’ violate those liberal and civic values just as badly.

Conditions

Several conditions tended to favour the occurrence of such ethno-nationalist conflicts. Both students and teachers emphasized that an important motivation for MWA and SPH students to choose these programmes is to help people who suffer from similar problems they themselves experienced. Having a refugee background or living in ‘lower’ class neighbourhoods, many migrant students had experiences of broken families, trauma, crime and drugs and wanted to help clients with similar problems. This close connection between personal experiences and social issues discussed in class, especially when related to diversity like the overrepresentation of migrants in crime statistics, easily leads students to take these issues very personally, giving a particularly emotional and conflictive potential to discussions about these diversity-related issues.

Moreover, the didactic approach common to social professions that emphasizes personal reflection also favours ethno-nationalist conflicts. Miriam, a 23-year-old full-time SPH student without a migration background, said about sexuality-related issues that trigger ethno-nationalist conflicts:

You do not know how to deal with these issues. You do not have the theory plus your own norms, values and feelings hinder you, perhaps because you hardly know anything about it.

She argued that one’s own norms, values and feelings impede a professional way of dealing with these matters. However, students were encouraged to draw on exactly those norms, values and feelings due to the emphasis on personal reflection, teachers emphasized. Social professions’ didactics want to create empathy, sensitivity and openness for the feelings and experiences of clients. Therefore, students have to make their own assumptions explicit. Only then, they will be able to relativize and problematize them.

However, regarding diversity-related issues, this second step hardly happened, as Miriam and other students argued. Teachers did not provide much input in terms of theory and knowledge. Their hesitation partially stemmed from the condemnation of the faculty by the Equal Treatment Commission in 2008. The subject of diversity is too delicate for them to discuss openly. ‘We have found a fearful way of talking about these matters’, a teacher said. Thus, students were free to express whatever view that comes to their mind, hardly disciplined or regulated by professional expertise.

Factors

It is argued that these conditions hamper the development of a professional attitude towards diversity-related social problems, i.e., they do not encourage students to learn the knowledge and skills they need as future social professionals, and thus give free way to factors that produce ethno-nationalist conflicts. These factors are discussed below.

Ethno-nationalist discourses in Dutch media and politics

With its R2 of .799 (p = .000), the students’ questionnaire model developed in the structural equation analysis () provides a strong explanation of the occurrence of ethno-nationalist conflicts. Two remarks need to be made here. First, the questions in the questionnaire refer to individual observations regarding ethno-nationalist conflicts, whereas those conflicts are a group phenomenon occurring in class. Thus, variables like socio-economic class, gender and age do not appear in the model, since they refer to individual respondent’s traits. It may well be possible that the average age, gender composition and socio-economic background of the class as a whole may influence the occurrence of ethno-nationalist conflicts. Ethno-migrant composition, i.e., the percentage of students with a migration background in class, does refer to the class as a whole and shows that the higher this percentage, the more likely ethno-migrant conflicts occur (see , and ).

Table 4. Regression weights of the students’ questionnaire model.

Table 5. Ranking of variables explaining ethno-nationalist conflicts in class (students’ questionnaire model).

Second, some variables in the model probably shape the observation of the occurrence of ethno-migrant conflicts instead of indicating this occurrence itself. If a student is treated well at internship institutions, the occurrence of ethno-nationalist conflicts in class will contrast very much with such treatment and will lead to higher scores on such conflicts. That will influence his or her observation, not necessarily the occurrence of conflicts themselves. Likewise, if a student does not care too much about the study (Laziness), s/he may be less likely to notice such conflicts. The same holds true when students try to create a positive self-identity (Recognition work, see , and ).

Then, the model contains variables that may influence both the observation of the occurrence of ethno-nationalist conflicts and this occurrence itself. If a student shares interests in music, in having a night out or in sports with other students, that may lead him or her to pay little attention to ethno-nationalist conflicts in class. However, if such interests are shared by most of the students in class, conflicts themselves will be less likely to occur. The same holds true for feeling accepted by fellow students in class.

The model suggests that the strongest predictor of ethno-nationalist conflicts in class is the impact of ethno-nationalist discourses in media and politics. It explains 20.13% of the model’s variance in ethno-nationalist conflicts in class (). This impact refers to fierce discussions and tensions between students triggered by issues that Dutch media and politics associate with ‘non-Western’ migrants, like problems of crime, terrorism, homosexuality, ‘Islamization,’ minorities, radical right politician Geert Wilders’ discriminatory statements and the 9/11 events. Of course, strictly speaking we cannot talk about causality here based on cross-sectional instead of longitudinal data. However, the interview and focus group data confirm these quantitative findings. They show that conflicts in class are verbalized in terms of this ethno-nationalist discourse in media and politics with frequent references to statements by politicians in the media.

The conflictive event about homosexuality discussed above exemplifies how this works. Students reproduce the association of migrants with illiberal views on homosexuality and the association of liberal views with ‘Dutchness’ in discourses in Dutch media and politics. They translate the notion of incompatibility between liberal and illiberal views in these discourses into conflicts between each other. Their conflicts on the same issues resonate the provocations in ‘civic’ integration packages for migrants that show Dutch pictures of kissing homosexuals and topless women that would depict ‘Dutch’ liberal values (Suvarierol Citation2012). Ethno-nationalist discourses in Dutch media and politics trigger (Siebers and Dennissen Citation2015) such conflicts around topics like crime, sexuality and gender that are particularly relevant to the work of social workers, much less so to other programmes like ICT or economics. These ethno-nationalist discourses provide the meanings that students take over in their conflicts in class. These meanings essentialize migrants and non-migrants in categories of background and descent, and stigmatize migrants by attributing negative connotations to them (see Siebers Citation2017 and Siebers and Dennissen Citation2015 for similar processes in Dutch work settings).

and furthermore show that these ethno-nationalist discourses in media and politics not only fuel ethno-nationalist conflicts between students directly, but also ethno-nationalist tensions between students and teachers as well as ethno-national subgroup formation in class that, in turn, also feed ethno-nationalist conflicts between students (7.72 and 6.04% respectively).

Multiculturalist theories in citizenship education

The model constructed on the basis of the teachers’ questionnaire () also delivers a strong explanation of the occurrence of ethno-nationalist conflicts with an R2 of .737 (p = .000). It mainly contains variables that focus on teachers’ observations in class with some variables expressing teachers’ views that, I assume, they enact in class and thus influence ethno-nationalist conflicts.

The teachers’ model confirms the impact of ethno-nationalist group formation and radical viewpoints, explaining 39.65 and 25.90% respectively of the model’s variance in ethno-nationalist conflicts in class ( and ). Regarding those radical views, teachers indicated topics that stem from ethno-nationalist discourses in Dutch media and politics, similar to the ones indicated above.

Table 6. Regression weights of the teachers’ questionnaire model.

Table 7. Ranking of variables explaining ethno-nationalist conflicts in class based on the teachers’ questionnaire model.

and also show that, although the emphasis in these courses is on self-reflection instead of theory, some essentialist and multiculturalist theories are actually discussed in citizenship education. They culturalize migrants and non-migrants in different communitarian categories and fuel ethno-nationalist conflicts in class (14.95%). Their effect is exactly the opposite from what is intended in these courses. Teachers and students referred to theories by Geert Hofstede (Citation2001) on national cultural differences, by John Berry (e.g., Citation2005) on acculturation and by David Pinto (Citation2000) on intercultural communication. These theories reproduce a similar essentialization and stigmatization as discourses in Dutch politics and media discussed above do. Several students indicated their strong discontent with such theories.

The teachers’ model ( and ) also indicates a way out of ethno-nationalist conflicts. Teachers effectively countered such conflicts when they discourage students to use ethno-nationalist identifications (11.08%) or when they encourage students to take a professional approach to diversity issues (8.42%). That involves discussing cultural diversity issues not as an aim in itself, but as a way to help students to pose the right questions to clients and citizens in professional practice. It requires separating person and opinion and to avoid taking critique on cultural issues personally. Ina, a 61-year-old teacher with a ‘Western’ migration background, said: ‘You must take a professional distance, step over your own experiences, background and socialization’ (see also Miriam’s statement above).

However, the legitimacy of social professions is undermined by the fact that most teachers and students tend to classify their professions as typically ‘Dutch’ or ‘Western’. Isaac, a 56-year-old male teacher with a Dutch background, said: ‘We do all this from a Western perspective’. Thus, social professions are ethno-nationalized as a cultural particularity, which encouraged some students with a ‘non-Western’ migration background to reject what teachers tell them on the basis of respect for diversity.

Conclusions

After leaving methodological nationalist assumptions about a supposed naturalness or functionality of ‘the nation’ behind, the destructive impact of citizenship education framed along ethno-nationalist lines becomes visible. In a globalized world in which students with various backgrounds get together in class, ethno-nationalist discourses in media and politics as well as in specific diversity theories trigger ethno-nationalist polarization and conflicts in class of this faculty. They put forward a substantive and particularistic understanding of citizenship that excludes students with migrant origins. Subsequent conflicts disrupt the learning process in citizenship education and in other courses in these MWD and SPH programmes.

These programmes are particularly vulnerable to those conflicts as key elements of these ethno-nationalist discourses, like the association of migrants with crime and illiberal views on homosexuality, are directly relevant to the problems these students prepare themselves to deal with in their future work. That is much less the case in CMV and other programmes at this university that, for example, focus on ICT or technique, where students seem to ignore the effects of the ethno-nationalist framing of citizenship education.

This study contributes to the literature by highlighting the destructive impact of nationalism on citizenship education and overall education in the classes of this faculty (see also Duemmler Citation2015). Its findings entail a critique not only on ethnic but also on civic nationalism. Gellner’s (Citation1983) argument about the functional need for civic nationalism in industrial society may no longer be valid in post-Fordist Dutch society marked by the service sector instead of industry. Moreover, civic values have become incorporated into Dutch ethno-nationalism and thus can hardly serve as an alternative to ethno-nationalism as long as they maintain a link with nationalism as such. These findings align with cosmopolitan understandings of citizenship education that define citizenship not only on national but also on local, global or European levels (Banks Citation2008; Osler Citation2011; Shahjahan and Kezar Citation2013).

The question is, though, what kind of identities citizenship education is supposed to promote on these and other levels. Both civic and ethnic nationalism define national identity in terms of (imagined) community membership (Anderson Citation2006), but already in Citation1887 Ferdinand Tönnies pointed to a modern shift from community to a society differentiated into various fields or institutions like education. As an identity framed in terms of community membership, ethno-nationalist identity disrupts the proper functioning of education in the globalized classes of this faculty within which it erects an opposition between students considered to belong to this community and those who do not. That may apply to all identities framed in terms of community membership (Etzioni Citation2001), including the multiculturalist theories taught in this faculty.

In globalized settings, a more fruitful approach to citizenship education is perhaps to teach students how to navigate effectively and responsibly through institutions like education, the labour market and politics. Here, sameness can be constructed and recognized focusing on institutionally ‘nested’ identities of fellow students, colleagues and citizens, providing the conditions for the subsequent recognition of individual uniqueness (Brewer Citation1991; see also Shore et al. Citation2011 and Siebers 2009 on work settings). Without the need for an overarching community, the basic universal nature of civic and liberal values like human rights can be restored. These concluding thoughts may perhaps inspire future research and reflection on the directions in which to develop a fruitful understanding of citizenship education, especially in times of rising nationalism.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 .There are no reasons to believe that the impact of the conditions and factors we found to trigger ethno-nationalist conflicts in class in 2011 will be any different today. Moreover, the findings of this study will be ever more relevant with ethno-nationalism currently on the rise in many parts of the world.

2 .The author is very grateful to Paul Mutsaers, several student assistants and reviewers of previous drafts.

3 .Now called The Netherlands Institute for Human Rights.

4 .The term ethno-migrant (Siebers and Van Gastel Citation2015) is used here to refer to relations between people with and without a migration background, relations that may or may not become the object of ethno-nationalization. In the Netherlands, someone is defined as having a migration background if at least one of his or her parents was born abroad. Origin matters here, not nationality. Dutch studies (e.g., Siebers Citation2009; Citation2017) show that tensions and conflicts may evolve around the opposition of first- and second-generation migrants with a so-called ‘non-Western’ background versus non-migrants. Differences between people with various migration backgrounds become subordinated to this main opposition, see also section Ethno-nationalist conflicts in class

5 .Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, the Middle East and Asia, except for Japan and Indonesia, are officially labelled as ‘non-Western’ parts of the world.

References

- Anderson, B. R. 2006. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism. London and New York: Verso.

- Banks, J. A. 2008. “Diversity, global identity, and citizenship education in a global age.” Educational Researcher 37 (3): 129–139.

- Bénéï, V. 2005. “Introduction: Manufacturing citizenship – Confronting public spheres and education in contemporary worlds.” In Manufacturing Citizenship: Education and nationalism in Europe, South Asia and China, edited by V. Bénéï, 1–34, London and New York: Routledge.

- Bénéï, V. 2008. Schooling Passions: Nation, History, and Language in Contemporary Western India. Redwood City (CA): Stanford University Press.

- Berry, J. W. 2005. “Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 29 (6): 697–712.

- Bourdieu, P., and J.-C. Passeron. 1990. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage.

- Brewer, M. B. 1991. “The social self: On being the same and different at the same time.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 17 (5): 475–482.

- Browne, M. W., and R. Cudeck. 1993. “Alternative ways of assessing model fit.” In Testing Structural Equation Models, edited by K. A. Bollen and J. S. Long, 136–162, Newbury Park (CA): Sage.

- Curşeu, P. L., R. Stoop and R. Schalk. 2007. “Prejudice towards immigrant workers among Dutch employees: integrated threat theory revisited.” European Journal of Social Psychology 37 (1): 125–140.

- Duemmler, K. 2015. “The exclusionary side effects of the civic integration paradigm: boundary processes among youth in Swiss schools.” Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power 22 (4): 378–396.

- Duyvendak, J. W. 2011. The Politics of Home. Belonging and Nostalgia in Western Europe and the United States. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Duyvendak, J. W., P. Geschiere and E. Tonkens (ed.). 2016. The Culturalization of Citizenship. Belonging and Polarization in a Globalizing World. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Etzioni, A. 2001. The Monochrome Society. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Fairbrother, G. P. 2003. “The Effects of Political Education and Critical Thinking on Hong Kong and Mainland Chinese University Students’ National Attitudes.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 24 (5): 605–620.

- Fox, J. E. 2004. “Missing the Mark: Nationalist Politics and Student Apathy.” East European Politics and Societies 18 (3): 363–393.

- Fox, J. E., and C. Miller-Idriss. 2008. “Everyday nationhood.” Ethnicities 8 (4): 536–563.

- Gellner, E. 1983. Nations and Nationalism. Ithaka (NY): Cornell University Press.

- Gholami, R. 2017. “The art of self-making: identity and citizenship education in late modernity.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 38 (6): 798–811.

- Goode, J. P., and D. R. Stroup, 2015. “Everyday Nationalism: Constructivism for the Masses.” Social Science Quarterly 96 (3): 717–739.

- Hahn, C. 1998. Becoming Political: Contemporary Perspectives on Citizenship Education. Albany: SUNY.

- Halikiopoulou, D., S. Mock and S. Vasilopoulou. 2013. “The civic zeitgeist: nationalism and liberal values in the European radical right.” Nations and Nationalism 19 (1): 107–127.

- Hofstede, G. 2001. Culture’s Consequences. Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations. 2nd Edition. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage.

- Jaskulowski, K., P. Majewski, and A. Surmiak. 2018. “Teaching the nation: history and nationalism in Polish school history education.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 39 (1): 77–91.

- Laegaard, S. 2007. “Liberal nationalism and the nationalisation of liberal values.” Nations and Nationalism 13 (1): 37–55.

- Luykx, A. 1998. The Citizen Factory: Schooling and Cultural Production in Bolivia. Albany: SUNY.

- Miles, M. B., and A. M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded source book. London: Sage.

- Miller-Idriss, C. 2009. Blood and Culture. Youth, Right-Wing Extremism and National Belonging in Contemporary Germany. Duke: Duke University Press.

- Osler, A. 2011. “Teacher interpretations of citizenship education: national identity, cosmopolitan ideals, and political realities.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 43 (1): 1–24.

- Osler, A., and L. Lybaek. 2014. “Educating ‘the New Norwegian We’: An Examination of National and Cosmopolitan Education Policy Discourses in the Context of Extremism and Islamophobia.” Oxford Review of Education 40 (5): 543–566.

- Parmenter, L. 1999. “Constructing National Identity in a Changing World: Perspectives in Japanese education. “British Journal of Sociology of Education 20 (4): 453–463.

- Pinto, D. 2000. Intercultural communication. A three-step method for dealing with differences. Leuven: Garant.

- Saito, H. 2011. “Cosmopolitan Nation-Building: The Institutional Contradiction and Politics of Postwar Japanese Education.” Social Science Japan Journal 14 (2): 125–144.

- Scholten, P., and P. Holzhacker. 2009. “Bonding, bridging and ethnic minorities in the Netherlands: changing discourses in a changing nation.” Nations and Nationalism 15 (1): 81–100.

- Shahjahan, R. A., and A. Kezar. 2013. “Beyond the ‘National Container’: Addressing Methodological Nationalism in Higher Education Research.” Educational Researcher 42 (1): 20–29.

- Shore, L. M., A.E. Randel, B.G. Chung, A.D. Dean, K. Holcombe Ehrhart, and G. Singh. 2011. “Inclusion and Diversity in Work Groups: A Review and Model for Future Research.” Journal of Management 37 (4): 1262–89.

- Siebers, H. 2009. “Struggles for Recognition: The Politics of Racioethnic Identity among Dutch National Tax Administrators.” Scandinavian Journal of Management 25 (1): 73–84.

- Siebers, H. 2017. “What turns migrants into ethnic minorities at work? Factors erecting ethnic boundaries among Dutch police officers.” Sociology 51 (3): 608–625.

- Siebers, H., and M.H.J Dennissen. 2015. “Is it cultural racism? Discursive oppression and exclusion of migrants in the Netherlands.” Current Sociology 63 (3): 470–489.

- Siebers, H., and J. van Gastel. 2015. “Why migrants earn less: In search of the factors producing the ethno-migrant pay gap in a Dutch public organization.” Work, Employment and Society 29 (3): 371–391.

- Smith, A. D. 1986. The Ethnic Origins of Nations. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Smith, A. D. 2008. “The limits of everyday nationhood.” Ethnicities 8 (4): 563–573.

- Suvarierol, S. 2012. “Nation-freezing: images of the nation and the migrant in citizenship packages.” Nations and Nationalism 18 (2): 210–229.

- Tönnies, F. 1887. Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft. Leipzig: Fues’s Verlag.

- Tormey, R. 2006. “The construction of national identity through primary school history: The Irish case.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 27 (3): 311–324.

- Van Reekum, R. 2012. “As nation, people and public collide: enacting Dutchness in public discourse.” Nations and Nationalism 18 (4): 583–602.

- Van Reekum, R., and J. W. Duyvendak. 2012. “Running from our shadows: the performative impact of policy diagnoses in Dutch debates on immigrant integration.” Patterns of Justice 46 (5): 445–466.

- Van Reekum, R., and M. van den Berg. 2015. “Performing dialogical Dutchness: negotiating a national imaginary in parenting guidance.” Nations and Nationalism 21 (4): 741–760.

- Widaman, K. F., and J. S. Thompson. 2003. “On specifying the null model for incremental fit indices in structural equation modeling.” Psychological Methods 8 (1): 16–37.

- Wimmer, A., and N. Glick Schiller. 2002. “Methodological Nationalism and Beyond: Nation-State Building, Migration and the Social Sciences.” Global Networks 2 (4): 301–334.

- Yemeni, M., H. Bar-Nissan, and Y. Shavit. 2014. “Cosmopolitanism versus Nationalism in Israeli Education.” Comparative Education Review 58 (4): 708–728.