Abstract

In this article, we use data from ethnography-inspired studies of eight Swedish schools. We describe and analyse how a number of neoliberal-inspired economic and political processes have (re)organised social and relational practices in local school settings. There is an increased focus on individuality in the everyday working lives of teachers, where result-centred practices, relations and professional identities have replaced notions of equality and compensatory interventions. In our study, the teachers describe an increasing focus on performativity, competition and hierarchisation. We use fairness as a lens for illuminating these changes in social relations, changes in the organisation of teachers’ practices, and teachers’ struggles with these changes. The purpose of this study is to analyse how the current reforms are enacted and how they affect the working lives of teachers, and thereby to contribute to the current discussion on how the last decades of political and administrative changes have affected educational practice.

Introduction

This article addresses how teachers deal with, handle and live with value-changes in their everyday working lives after three decades of neoliberal-inspired economic and political processes.1 The neoliberal transformation of education has been discussed thoroughly in the British Journal of Sociology of Education by, amongst others, Demaine and Smith (Citation2010), Morrissey (Citation2015), Inzunza et al. (Citation2019). It has also been discussed elsewhere by scholars such as Ball (Citation2003), Olssen (Citation2010) and Beach (2013). Our overall ambition is to contribute to the current discussion on how these processes of transformation have affected educational practice by focusing on a specific national context, Sweden. Since the eighties, a series of reforms have dramatically changed the Swedish educational system. We view these changes as part of a neoliberal transformation which, in parts, has gone further than in most other countries (Lundahl Citation2002, Citation2005; Stenlås Citation2009).2 In Olssen and Peters’ (Citation2005) description of the transformation process from a welfare society into a neoliberal society, they claim that a series of interrelated global, national and local reforms have gradually reshaped the political and economic frameworks that regulate social and institutional life. Today, as Furlong points out, it seems like neoliberal solutions with marketization and commodification have become a part of the general population’s common sense, and is viewed as necessary or/and unavoidable from the perspective of international agencies and governments (Furlong Citation2013, 31). As a significant societal institution, education has been a hub in this transformation.

One way to understand neoliberalism is to compare it to classical liberalism. Olssen (Citation2003, Citation2016) argues that neoliberalism differs from classic liberalism in the sense that it is built on a different conception of state power. Generally speaking, classical liberalism, ascribe the individual with an autonomous nature, and trust human systems (such as education) to improve effectively with a minimum of state intervention. Within classical liberalism, markets are the result of a social and organic growth over time, and the state is to interfere with these markets as little as possible (Olssen and Peters Citation2005: Olssen 2016). Only when individuals are structurally disfavoured the state should regulate the market, or economical transactions (a view common within classical socio-liberalism). Within neo-liberalism “the state instead seeks to create an individual that is an enterprising and competitive entrepreneur” (Olssen and Peters Citation2005, p 315). The state is therefore active in relation to the individual. It might seem paradoxically, that neoliberalism at one and the same time presumes an active state, and increased economic freedom for individual agency. However, while individual freedom and social autonomy was a goal in itself under classical liberalism – since it was not only an economic program – well-functioning markets is the goal under neoliberalism, and the individual is just a mean in order to uphold and develop these markets (see also Rose Citation1999 ).3 The individual is the clay, which shall be moulded and shaped into become a useful citizen/consumer/teacher/student with productive conduct, why the relation between the state and the individual is characterized by control instead of trust, with increased systems for monitoring and testing as a result.4

We have studied these new forms of control in our previous studies, and discussed the effects of, for example, the introduction of monitoring techniques and changes in cultural and social life of schools (Strandler Citation2016, Citation2017; Erlandson and Karlsson Citation2018; Karlsson and Erlandson Citation2018, Citation2020). Although we would argue that these studies have provided insights into the effects of neoliberal transformation, we, and research in the field of sociology of education generally, have in parts lacked a language for conducting in-depth qualitative research on the neoliberalization of schools and teachers’ everyday lives. Here we try to go beyond a focus on certain aspects on educational reforms and take an alternative view to elucidate how the neoliberal paradigm permeates everyday life, and the working lives of teachers.

As neoliberalization penetrates deeper into society and into historically stable practices with long sociogenesis, for example old educational institutions, it encounters older conventions for organizing work and institutional behavior. Encounters between neoliberalization (or any process of change) and older conventions thus involve conflicts between different ways of understanding individuals, the relationship between individual and state, as well as how individuals regulate their dealings. Pivotal in these encounters are issues on fairness. That is, encounters between different social or/and ethical codes within a social practice. These issues concern how teachers regulate their work in relation to students, school administration and co-workers and to themselves as self-regulation. But, also how teachers look upon career opportunities, the distribution of salary within the teacher collective, and not the least the meaning of the daily teaching work. From our point of view, fairness constitutes a fundamental and structuring element that is seen in social relations, changes in the organisation of teachers’ practices, as well as in teachers’ struggles with these changes (Gewirtz Citation1998; Reyes and Imber Citation1992; Chatterjee and D’ Aprix Citation2002). It involves the production of subjectivity, in power relations and institutional practices, as well as moral assessments of different working conditions. What counts as fair within a social practice is from the theoretical perspective of this article a materialized lived political discourse within an institutional framework that embodies meaning as well as social relationships among teachers.

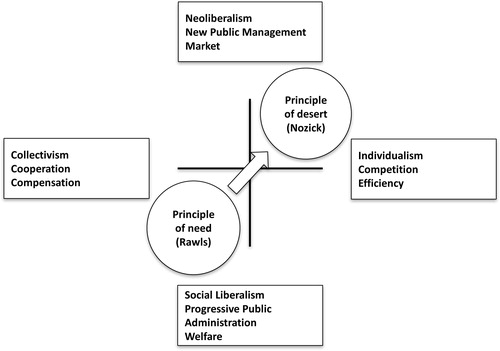

One way to understand the shift of dominant values, as well as of potential encounters that can arise in local, everyday work, is to turn two political and ethical liberal thinkers who illustrate the shift from a liberal to a neoliberal position when it comes to fairness, namely Rawls and Nozick. Obviously, these two thinkers could be intertwined with different discussions concerning politics, state and so forth. Our intention is not to go further into a philosophical discussion, but instead to use their thoughts to illustrate two different ways to recognize what counts as fair in society and within social institutions. In a broad sense, they both belong to a liberal tradition, Rawls being a classic social liberal, and Nozick being neoliberal. Rawls’ main line of argumentation is that he accepts unequal distribution of public goods, and even suggests it as preferable, but also gives a precondition for it: unequal distribution of public goods is acceptable if, and only if, it benefits the least advantaged (Rawls Citation1973). By this, Rawls embraces an egalitarian position that could be called a principle of need. Nozick, on the other hand, views taxes as an arbitrary confiscation of property and as a violation of citizens’ rights. This makes any form of redistribution of property unacceptable. Instead he argues that any compensatory interventions need to be the result of voluntary transactions (Nozick Citation1974). Nozick thus embraces a libertarian position that could be called a principle of desert. These two different standpoints obviously lead to consequences regarding how society and relations between people ought to be organised, as well as suggesting different figures for analysing contemporary societies. A consequence of this is that there are different – but still justified – ways of understanding fairness.

In this text, we return to the empirical material of our previous studies and focus on how teachers’ reactions, frustrations and corridor discussions tend to revolve around questions concerning fairness. More specifically, we use fairness as a lens to understand everyday conflicts that concern social and institutional behaviour in educational settings during neoliberalization. We have made quite an effort to be analytically unbiased in relation to the concept of fairness.5 This means we do not mainly frame a social and/or educational practice as being fair or not unfair as such. The same practice can be viewed as both fair and unfair, depending on which theoretical/ideological perspective on fairness that is used to evaluate the social activities within that practice. This makes fairness an unequivocally positive term and makes opposing fairness simply an odd position to take.

Two research questions have guided our analysis: What signifies the local school changes that put the teacher’s emotions in motion? How does these changes in teachers’ everyday practice relate to general changes within the Swedish welfare system?

Reorganisation of educational systems

After World War II the Swedish school system evolved as a public institution with high hopes for an egalitarian and universalistic “school for all” that would stimulate economic growth, promote democracy and (most importantly) reduce the impact of student backgrounds (see also Telhaug, Mediås, and Aasen Citation2004, Citation2006). Centralised forms of state governing were deemed necessary to realise such high ambitions, including state subsidies and detailed regulations for curricula, syllabi, resources, organisations, staff and their daily work (Lundahl Citation2002). A comprehensive school system thus gradually expanded during the post-war period, involving increasing numbers of students and compensatory interventions to reduce the impact of social backgrounds (Lindensjö and Lundgren Citation2000). But, it became increasingly clear, according to that the school system could not meet the high expectations during the 1970s (Forsberg and Lundgren (Citation2010). A long period of economic and political stability ended and fuelled criticism toward schooling and the welfare system in general for being excessively inefficient, heavy footed, autocratic and bureaucratic (Blomqvist and Rothstein Citation2008).

Since the eighties, a series of reforms have dramatically changed the Swedish educational system. More specifically, two dominant themes can be identified: decentralisation and marketisation, both involving an increase in freedom for students to choose courses, direction and profiles, and for parents to choose between schools (Dahlstedt Citation2007). Starting with a decision in the Swedish parliament in 1989, changes were made in the curriculum, and the responsibility for schools was transferred from the central government to the municipalities (Proposition Citation1989/90:41; Proposition 1990/91:18).6 Within the next few years, comprehensive choice and voucher reforms were introduced (Proposition Citation1991/92:95; Proposition Citation1992/93:230). Hence, within a few months the education system was transformed from being one of the most regulated to one of the most deregulated in the western world (Lundahl Citation2002, Citation2005; Stenlås Citation2009). As a result, numerous private schools have started up, especially at upper-secondary level, which has established a Swedish school market. In the school year 2010/2011, 24 % (Skolverket Citation2011) of all upper-secondary students attended independent schools, and in some municipalities up to 60 % (Vlachos Citation2011). Recent changes have included a more detailed curriculum (Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2011) with various forms of outcome controls such as increased numbers of national tests and grading in lower years (Wahlström and Sundberg Citation2015), a strengthened school inspectorate (Carlbaum et al. Citation2014; Rönnberg Citation2014), state-funded career services and selective pay rises.

Although these reforms are spread over time and focus on somewhat different topics, we view these changes as a part of a neoliberal transformation of the Swedish educational system with the specific set of administrative tools called New Public Management. Olssen and Peters characterise the new administrational era by saying that: “markets have become a new technology by which control can be effected and performance enhanced, in the public sector” (Olssen and Peters Citation2005, 316). Researchers such as Ball (Citation2003); Ozga et al. (Citation2011); Hursh (Citation2005) and Beach (2013), have discussed how, during the last three decades, a number of neoliberal-inspired economic and political processes have transformed educational systems in different countries in the west (see also Ball and Youdell Citation2008; Ozga and Jones Citation2006). Olssen and Peters argue for a distinction between, on the one hand, the older administrative system where the public servant, via rules and trust, worked for the common good, and on the other hand, NPM where the public servant, via quasi-market arrangements, works for efficiency, flexibility and economic results. The question of whether collectivism, cooperation and compensation should be the moral compass or whether it should be individualism, competition and efficiency is analysed by Olssen and Peters (Citation2005) as a successive change from classical liberalism into neoliberalism, i.e. as a change in economic rationale but also in governance, as well as in local, social and relational practices (see also Bunar and Sernhede Citation2013).

Method

This study is a result of the recurring themes of fairness that we have seen in data from previous studies (Strandler Citation2016, Citation2017; Erlandson and Karlsson Citation2018; Karlsson and Erlandson Citation2018, Citation2020): informants in highly diverse settings seemed to address the very same changes in administrational rationales, regardless of whether they spoke about changing working conditions, social relations, school development or other issues. We reread, synthesised and reanalysed our data in an attempt to broaden and deepen its scope (Weed Citation2006). Therefore, the study below is the result of analysis of different manifestations of fairness in various ways during a new reorganised administrative regime. But also of how participants; teachers and principals that lived under this new regime identified, reacted and coped with it. In other words, this is a meta-study or rather a meta-ethnography based on years of empirical and theoretical work. Since questions concerning fairness summarized much of the frustration and the corridor discussions found in the teachers’ voices in previous studies, it was a theme that we yet had to explore. Therefore, we analysed the expressions of fairness in relation to changes in social interactions in teachers’ everyday lives as social, institutional and local manifestations of changes in economy, politics and education policy.

The corpus of produced empirical data is the result of ethnographical studies conducted between 2010 and 2016.7 The data concern eight different schools in the south of Sweden. The schools ranged from primary and lower-secondary schools up to upper-secondary schools. The methods included thick descriptions, participant observation-based investigations, collection and analysis of documents, as well as interviews and informal conversations with informants (Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2007). A major inspiration for our ethnographies was in the first hand found in the Scandinavian ethnographical tradition (Beach and Dovemark Citation2011; Beach Citation2013, Erlandson and Beach Citation2014). Typical of this tradition are long-term fieldwork, integration between locally situated events, relations between agents within institutional frameworks, and sociocultural patterns developed over time, together with a sensitivity to political and economic surroundings that places the ethnographical site in a larger context. We spent approximately 450 hours in the field. Over the years, several teachers have come and gone as data producing participants since this is the nature of long-term ethnographical studies. Our main examples come from approximately a dozen deep-interviews of about 50 or more. The excerpts that we reanalyse in this particular paper comes from interviews conducted during the fieldwork above. The excerpts are first of all chosen for the reason that they represent the views of the interviewees who have produced the excerpts, and secondly for the reason that the interviewees represent the collective of teachers and that the excerpts provide a good representation of the views of the teachers.

The main headings that we use to organise the result are Manifestations of fairness in reorganised educational practices and Handling fairness in reorganised educational practices. Under these two headings, we show how the introduction of new hierarchies and the organisational emphasis on producing results have given rise to new ways for teachers to conceptualize fairness in organising their work and view themselves as teachers, while making their work visible for colleagues as well as administrational staff. Hence, our excerpts should be seen as examples of the recurring themes above, although they also constitute the basis for a retrospective analysis, in which we use the theoretical and historical starting points described above (Beach and Dovemark Citation2011). Our method can thus be summarised as a repeated process of zooming in on local practices, and zooming out through contextualisation and theorising.

Results

Manifestations of fairness in reorganised educational practices

The new administrational era described in the framework is clearly visible in our data, with teachers’ work revolving around a number of new administrative responsibilities, assignments and routines, as well as around increased competition between schools and between teachers. When asked whether teachers’ roles have changed as a result of these increases, a headmaster described a shift in focus:

Yes, it’s obvious that this NPM perspective has had an impact during the last few decades, and it’s really a way to try to measure production, and we’ve seen lots of that being introduced in Swedish schools, in terms of control systems and the like. And this involves, quite obviously, an increased administrative burden for schools and school management, and for all other school staff. Indeed, it shifts focus away from the most important processes: what is happening in classrooms, the pedagogical and operational processes. (Headmaster interview)

These increases in administrative systems related both to school management, including features such as quality assurance, reports and follow-up, and to teachers’ practices, including features such as standardised testing, work routines, grading and reporting results in various internet-based learning management systems. The systems entailed a form of reactive, indirect control that made it difficult for teachers and administrators to shirk from the new and increased administrative responsibilities, which in turn shifted focus away from teaching toward “other” tasks:

I have a feeling that my working hours are not sufficient for the tasks I am set to do in a good way. In order to get it all done I have to take short cuts. Well, what has to be documented and sent upwards cannot be made short. I take short cuts with other things, like I am not as prepared for a lesson as I could be. I can keep going and I can pursue my teaching without being fully prepared, or as prepared as I’d like to be. It works anyway, but it could be much better. It is difficult to take short cuts with the administrative tasks. There is the control again. (Anders)

For Anders, the administrative systems seemed to circumscribe his options since they both delegated certain responsibilities to him (teaching), while at the same time they regulated certain activities (documentation) in detail. The systems thus both appealed to teachers’ autonomy (delegated responsibilities) and embedded their choices in administrational and social structures.

These excerpts also reveal a focus on effectiveness in order to produce result in the schools, while issues of, for example, pupils’ needs, support teaching and professional expertise had become secondary. By this, we do not suggest that such issues had ceased to exist in the schools; they most certainly did exist. It is clear, however, that discussions and perceptions of education and working life in many respects revolved around questions of individualism, competition and efficiency, both among teachers and in school management. What we see here are in a way examples of an altered social logic for working life in the schools, a logic where collectivism, cooperation and compensation were strikingly absent in discussions. Thus, we see a change in what counts as institutionally acceptable and fair in implicit rules for social action, for how to value and recognize professional merits and professional collaboration.

Enhancement of performativity

The altered social logic changed the premises of working life and operated via various forms of documenting practices – of lessons, results, plans and events – which enabled internal and external communication, within as well as about schools:

One documented activity is always more than two undocumented activities. (…). I’m increasingly doing it [documenting] for myself, so to speak. Not only because I consider it a task… I’ve discovered the benefits of it. The times you’re questioned… it could be parents, principals, pupils or anyone really… you can show what you’ve done… (Anders)

(Interviewer: Are you documenting more nowadays?) Yes, I have to do that! Because I want my back covered. I don’t want to sit there and feel that I have to defend my work, or my profession, because that’s what I have to do, somehow. (Gunilla)

It is worth noting that the teachers above did not document primarily for the good of the students, but to cover their backs. For teachers, these kinds of new requirements entailed that certain activities came to be considered to be more feasible than others. As one teacher expressed in relation to the kind of teaching she thought was promoted by the demand for predictability and assessability:

I used to think like that a lot, that they [the pupils] should not really know what to expect when they came in. I used to think that was something that was satisfying in itself. And I still think that something needs to happen during lessons. But… well, now there has to be a plan for what they should do, nothing unexpected can suddenly happen in that way, because every lesson needs to be part of this plan…toward assessment. (Mary)

As we can see in the excerpts above, documenting in the new administrative systems had become a main priority, to some extent even more important than teaching itself. The drive behind these strong influences on the teachers’ activities seemed to be the new administrative systems’ presupposition of the possibility of describing highly ambiguous qualities in a clear, intelligible, quantitative manner. This shift toward documentation, predictability and performances corresponds to what Ball (Citation2003) calls the ‘terrors of performativity’ – a decrease in time, importance and priority for core tasks (such as teaching), and a simultaneous increase in tasks related to monitoring systems. However, such restructuring processes cannot simply be understood in the sense that teachers did not have time for core tasks. Displaying one’s own work, routines, competences, as well as student knowledge were accentuated and prioritised under these altered circumstances, while professional expertise, as well as discussions about teaching and adaptation of teaching to different student needs, were played down.

A precise way to analyse this change in educational practice is to acknowledge the twofoldness of evaluating and rewarding performances. On the one hand, as stated above and according to Ball, since reward systems are dependent on performances, displaying one’s performances is of significant value. On the other hand, we should not forget that rewarding performances as such is related to a change in what counts as legitimate. We can see in our data that a libertarian principle of desert has replaced an egalitarian principle of need. A consequence of this is that what is valued, and consequently rewarded, has changed (see Nozick Citation1974; Rawls Citation1973). In other words, in addition to the effects of performativity discussed by Ball, the distribution of resources also follows a different path from before.

Competition as a new core value

In our data, we see that the teachers were living in a social practice where the notion of fairness revolves around competition as a core value. Many of the new tasks did not relate to teaching in a direct sense (field notes, interviews) but rather to improvement measures to enhance school competitiveness, that is, improving or taking into account consequences for the outward “image” of the school (see Ball Citation2003). This was especially apparent in schools under competitive pressure to attract pupils. Mary (and several of her colleagues according to our field notes) rightfully assumed that their school’s survival, and ultimately their jobs, depended on the school’s reputation, which is why they made knowledge requirements, aims, detailed lesson plans, matrices etc. into more central features of teaching in order for their school to appear (more) well-organised, structured and focused (field notes 120924). Karl described a similar but yet different pressure from school competition:

I have a feeling that … statistics are so much more important than people, and I am a people person. I do go along with this thing with the statistics … that it is supposed to look a certain way in order to get money… It is more about commerce than pedagogy. Instead of talking didactics or pedagogy, we have to talk about formulations of what we could possibly do to get more pupils. It is marketing and has nothing to do with education or didactics at all, which makes me extremely angry. It makes me mad. I’m going crazy. (Karl)

In the interview, Karl is obviously incensed about the ways competition connects statistical improvements (i.e. pupils’ results) with allocations of economic resources. In the excerpt, Karl refers to a meeting at which the school’s headmaster presented statistics on last year’s student results. In particular, it was pointed out that results were declining, which in turn could affect both school funding and individual wages (field notes).

Ultimately, the restructuring momentum of competition does not only concern how to meet requirements from administrative systems, but also existential issues – one’s job, that job’s purposes and its core tasks. Hence, the teachers – more or less, and in different ways – need to renegotiate their roles as teachers and at the same time their view on how professional merits and cooperation are valued, and what counts as institutionally acceptable and fair within the local practice. Most clearly, we could see these processes of renegotiation in the increased hierarchisation and, even more clearly, in different types of strategies.

Handling fairness in reorganised educational practices

While the first sub-section of the results mostly concerned the reorganisation of educational practice, in this sub-section the focus is instead on how the teachers identify, react and cope in relation to the new regime.

Hierarchisation

Hierarchisation is not a new phenomenon. Hierarchies have long existed in schools in both formal (supervisory teachers, teachers who are responsible for development in a specific subject [ämnesansvariga], directors of studies) and informal ways (senior and experienced teachers with influence). However, teachers used to be appointed to participate in or lead school development projects or assignments based on different notions of what was considered to be ‘fair’ - for example expertise or experience – from those that are apparent from our data, where we can see that performativity and competition have affected how educational practices are hierarchised. As Roger explains below, it had become increasingly important to be among the winners rather than finding oneself on the “losing side” in the local school:

We will be divided into winners and losers. No matter what I think about it, I do not want to belong to the losing side. (Roger)

One has created new hierarchies where some are to be portrayed as better than others … and also supposed to lead others. Instead of having collegial collaboration it is the individual competition that rules … I do not know, I’m starting to feel that I am losing the passion for the profession. (Lisa)

One of the main things that made me choose to become a teacher was that I did not want to compete with other people. (Lena)

As shown in the excerpts above, however, the teachers are increasingly expected to participate in a (still ‘fair’ however) competitive game, in which performativity is a key element. The reorganisation of educational practices has thus altered the ways in which hierarchies are created, organised and legitimised. Categorisation of more or less successful schools, or better or worse teachers, may have taken place in the past but was not at the core in organising education and school working life. Desert has replaced need as a basic principle for structuring the discourse of fairness. We can see this in the excerpts above, where the new forms of hierarchisation in a way enable a discussion on teachers, teaching and schools with a partially new terminology: in terms of winners and losers, or as Miranda puts it:

Nowadays, it is not just schools that operate in a free market. Teachers have become their own brands and compete with their colleagues in order to fulfil their career opportunities. (Miranda)

The new way to organise educational practices does not therefore only enable but requires hierarchisation between schools and between teachers.

Dwelling in the reorganised practice

Many of the teachers in our data did express discomfort with the increased hierarchisation in their schools:

People are trying to position themselves and try to… you simply obtain a position at the expense of your equal colleagues. (…)…they want to create a bureaucracy in a business-like way. I think it is completely counterproductive. (Eric)

I think people… are trying to show… so to speak… their best sides… to supervisors, and managers… among other things… to reinforce their position. It becomes a question of career. (Eric)

It all comes down to what it gives me, how do I benefit from doing certain things. It’s the same with these career positions. It is based on what it gives me, as an individual, not what it gives the school, the mission or the school’s ethos. There is increasingly more focus on the individual. Selfishness becomes the driving force rather than the common good. It’s all about splitting the collective. (Gunnar)

The various forms of criticism expressed above illustrate a shift in what was considered to be “fair” in relational and social practices. Although in different ways, Eric and Gunnar both describe a shift where questions of equality have been downplayed in favour of hierarchisation, careerism and individual success. As a result, they regard certain core values to be at risk: certain moral issues for Eric, and, similarly, notions of common good for Gunnar.

We can distinguish between two different ways to participate under the new regime: on the one hand, those who in a broad sense authentically accept the new premises; and on the other hand those who take a more strategic position in order to uphold a type of double standard – a position where irony and “putting on an act” are key elements in distancing oneself from the new premises, while at the same time participating and taking advantage of its benefits.

The authentic position

Lars in a way described an authentic view of the enhanced pressures on performativity, which he to a certain extent found “reasonable” in terms of a professional obligation:

If one were to describe a change from when I started as a teacher about ten years ago, then there are much higher demands… or much more control… more documentation requirements and more micromanagement stuff. When I started it was almost, "Here’s your schedule. Go ahead and work", which was hard, of course, but I could also do what I wanted and had great freedom. Then things have been tightened more and more. For better or worse. Some might probably feel as if they are controlled and not trusted. But I think … we work for the taxpayers in a public service mission and our work must also be checked and reviewed for quality. Clearly one should put pressure on people who draw a salary. (Lars)

Mary similarly described how she had slowly come to consider the new, outcome-focused assignments and routines in more positive ways, finding them to be “reasonable”:

I have always been negative toward grades really. But I really think that I can see… that for the first time there is some kind of… well, to some extent it functions like a circle, connecting everything. Before, it was more like, ok… we do this and then there is a mark, and then you do this and there is a mark. It was not any kind of… but now, everything has a function in some way /…/ it becomes a virtuous circle… hopefully. (Mary)

For Mary, the focus on assessments in teaching creates structure, direction and meaning. Even if Lars and Mary both have some objections to some of the imposed changes – less freedom and narrowed autonomy – they also embrace parts of it. Mary integrates the new assignments as meaningful parts of her professional identity, while Lars looks upon himself as a civil servant with obligations toward taxpayers.

Jenny, on the other hand, took quite a different position, arguing that she was tired of working hard for small change and had therefore resigned from a school development project she was heading (field notes):

When it comes to developing the school … there are kinds of little whispers that if you take part in developing the school it will generate better pay. It does not. That is bullshit. It’s just a game of power. (Jenny)

Jenny’s position differs from that of Lars and Mary since she expresses discomfort and tries not to participate. Jenny primarily refrains from accepting the symbolic benefits that are connected with participation in school development. On the other hand, referring to “the game of power”, she seems to be aware that money is an instrument for something else. As with Lars and Mary, Jenny thus “sees” the new game, but although she identifies problems with these changes, she participates. This participation is based on accepting a partly restructured role for teachers, with a new emphasis on performativity and competition, while pupils (unlike their results) are in many ways less in focus.

The position of double standards

Besides the authentic position, we also see examples of an ironic position represented in our data. Lars, who seemed to take quite an authentic position above, here expresses how he in some ways puts on an act of adaptation:

If you just focus on your teaching and put those other things aside…. being in different contexts and performing in different constellations, at meetings and in various groups… it will affect your salary negatively. I think they (the principals) do not look so much at the teaching; they only look at the results. The teaching should just work. I have noticed that my adaptation to the system has benefited me career-wise. I would probably not have been working there if it was not for that. (Lars)

When describing this notion of “putting on an act”, our informants often used a language with strong business connotations:

The settings make people work for free. The administration has no chance to evaluate your skilfulness as a teacher. Instead they focus on what you are doing besides your teaching. How many school development projects are you involved in? Which projects are you running? The best chance of raising your salary is to work for free and let the administration know what you are doing. (Miranda)

In Miranda’s view, you need to become your own “brand” as a teacher, which means that being a teacher is a highly internal and individualised affair. Martin, who had just started to participate in a major school development project to become a supervisor, is another example. His reasons, however, for participation in the project were imbued with a kind of career strategy, touching on cynicism:

To me it is a question of career. I would never even consider attending this supervisor training if it was not linked to the setting of wages, but that’s the way it is. If anything is to happen with your salary, you just have to show that you want to develop. But actually, I do not believe in this crap. (Martin)

In contrast to Jenny above, who holds a critical but authentic position, Martin seems to say that you can participate although in a strict sense you dislike it. As in the excerpts from Miranda and Lars, here we can see expressions of another, more distanced, position.

Discussion

Encounters concerning fairness can never be judged just in terms of being fair or not, but should also be addressed as manifestations of different political views. Also, what is recognized as being fair within an institution can change although the legal system remains the same. In our study, the teachers describe an increasing focus on performativity, competition and hierarchisation (see also Ball Citation2003; Beach, & Dovemark 2011). In the same way that schools become their own brands, teachers compete (and are expected to compete) with one another over limited resources. Our results regarding the neoliberal transformation of education follows the same vain as previous studies by for example Demaine and Smith (Citation2010), Morrissey (Citation2015) and Inzunza et al. (Citation2019).

A key issue for neoliberalization as relating to notions of fairness is that many teachers who feel uncomfortable under the new regime, in our view, still seem to perceive fairness in accordance with the principle of need, while society and the schools within it, now tends to acknowledge fairness via a principle of desert. But, it is important to notice that neither of these perspectives is in itself unfair, rather that which is discussed and understood as fair has changed. The on-going changes in local school settings revolve around how (not if) practices are seen as fair. Somewhat simply put, the administrational rationale that permeate teachers’ activities has gone through a fundamental change, a Rawlsian notion of fairness has successively been replaced by a Nozickian one ().

Figure 1. The figure shows a successive development in values from a Rawlsian toward a Nozickian notion of fairness in both the Swedish welfare system and the local practices exemplified in our data.

In our data, we see how the older view of the role of the teacher clashes with performativity, chains of competition and new forms of hierarchies. When teachers try to bridge the two different ways of recognising fairness in their everyday teaching lives, it results in new and somewhat troublesome relations and self-relations. For example, Mary can see the benefits of the new focus on performances; Lars sees himself as an authentic teacher, doing his best as an employee, but also takes on the role of a strategic, almost cynical, participator; Jenny, in turn, seems to have ended up with a relatively troublesome self-relation, as she wants to be a sincere teacher and colleague but has difficulties accepting a framework that requires her to take positions she is not willing to take. An important notion is that the reorganised practice is not directly dependent on the individual’s ways of dealing with this practice. In other words, the rationale works independently of the teachers’ stance, i.e. regardless of whether they take an authentic position or a position imbued with double standards. In fact, a strategy of double standards and irony can be more successful than pursuing authenticity, simply because the former allows more leeway to decide on what tasks to undertake (the displayable, measurable, competitive ones) and which ones to take short cuts with. Such strategic choices are made more difficult from a genuinely authentic position. Hence, using double standards does not only seem to be a justified position, but a productive part of the new regime. According to the newer notion of fairness, it is not only acceptable but also preferable that differences between teachers matter, and mirror performance. Following the principle of desert, it is fair that there are winners and losers.

From a left-wing perspective, this way to acknowledge fairness may be regarded as both distasteful and provocative, and as a way to hide social injustice behind a veil of good intentions, nice words and semantic discussions. Even so, this neoliberal view on fairness is possible to defend both legally and politically, and becomes a way to socially as well as institutionally transmit the justification of distribution of wealth via merit. However, an important point that we make is that every attempt to criticize the neoliberal view on fairness calls upon a different legal, theoretical, philosophical and not least political position. Which makes this critique external to the neoliberal perspective, and therefore quite easy to wave off as obsolete left-wing and/or Marxist delusions.

From our analysis we can conclude that not only bureaucratical and formal frameworks regulate the teachers´ behavior. Instead the teachers have successively, over time, been forced to learn a conduct which is directed by the ongoing marketization. As Furlong points out, neoliberal solutions with marketization and commodification have become a part of a common sense and is viewed as necessary or/and unavoidable (Furlong Citation2013, 31). This naturalisation of a neoliberal ideology is illustrated in our data, where the most rational behaviour clearly seems to be dictated by an internalized market logic. A lot of the teachers’ frustration can be traced back to the fact that they nowadays have to view themselves, not only as working professionals, but also as commodified professional agents offering themselves, and their selves, on an internal school market while forced to compete with other teachers (Strandler Citation2016, Citation2017; Erlandson and Karlsson Citation2018; Karlsson and Erlandson Citation2018, Citation2020).

However, beyond the level of political rhetoric and philosophical aspirations there is educational and social everyday practice inhabited by students and teachers that seldom address unfair conditions in theoretical and analytical terms, but instead as real world lived and experienced difficulties. The expressed frustrations point toward changes in values in political terms in regard to the school practice but also to the way to view education in society. Often our meetings with the teachers ended up in discussions on what justifies education as a social project. Questions concerning what is fair and not in this project becomes a “hub” for a clash of interests in actual institutionalized practices. Fairness is an interface between different economical and ideological value systems.

We have clearly entered a time period where competition is more of an ideal than cooperation, where career fulfilment is a preferable aspiration to equality and where displaying a quantity of performances is more valued than qualitative commitments to pupils’ development. But, as we have shown, the neoliberal ideology is stable and resilient when carried out and organized in local educational practices. The institutional implementation of the neoliberal view on fairness is a vital part in justifying the neoliberal reorganization of social educational practices.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 With a starting point in the late 1980s.

2 Neo-liberalism is not monolithically enacted but has given rise to different regimes. The neoliberal influence on Swedish education is on the verge to the extreme. It has changed the school system as a whole and reformulated the teachers’ working conditions, for example by linking teachers’ salaries to performances.

3 Viewing individuals as means is a core in bio-politics (see for example Rose Citation1999).

4 Erlandson & Karlsson describe this change in educational practice as shift “from trust to control” (2018).

5 Our starting point is that arguing that a situation, decision or result is fair, is to claim that there has been consistency, impartiality, no cheating, and equal treatment (if there are no moral, legal or other differences to consider). Fairness is arguably an unequivocally positive term. Opposing fairness is a simply odd position to take.

6 However, the state still has control over the educational system by means of the Education Act [Swedish: skollagen] and the curriculum. Government agencies are responsible for monitoring, supervision and evaluation.

7 In fact, the empirical study on our main ethnographical site are still on-going (October 2019). So far, there are no conflicting data or events that have made us re-consider our analytical position.

References

- Ball, S. J. 2003. “The Teacher’s Soul and the Terrors of Performativity.” Journal of Education Policy 18 (2): 215–228. doi:10.1080/0268093022000043065.

- Ball, S. J., and D. Youdell. 2008. Hidden Privatisation in Education. Brussels: Education International.

- Beach, D. 2013. “Changing Higher Education: Converging Policy-Packages and Experiences of Changing Academic Work in Sweden.” Journal of Education Policy 28 (4): 517–533. doi:10.1080/02680939.2013.782426.

- Beach, D., and M. Dovemark. 2011. “Twelve Years of Upper-Secondary Education in Sweden: The Beginnings of a Neo-Liberal Policy Hegemony?” Educational Review 63 (3): 313–327. doi:10.1080/00131911.2011.560249.

- Blomqvist, P., and B. Rothstein. 2008. Välfärdsstatens Nya Ansikte : Demokrati Och Marknadsreformer Inom Den Offentliga Sektorn [The Welfare State’s New Face: Democracy and Market Reforms in the Public Sector] Stockholm: Agora.

- Bunar, N., and O. Sernhede. 2013. Skolan Och Ojämlikhetens Urbana Geografi. Om Skolan, Staden Och Valfriheten [The School and the Urban Geography of Inequality. On the School, the City and Freedom of Choice] Gothenburg: Daidalos.

- Carlbaum, S., A. Hult, J. Lindgren, J. Novak, L. Rönnberg, and C. Segerholm. 2014. “Skolinspektion Som Styrning. [Governing by School Inspectorate].” Utbildning & Demokrati 23 (1): 5–20.

- Chatterjee, P., and A. D’Aprix. 2002. “Two Tails of Justice.” Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services 83 (4): 374–386. doi:10.1606/1044-3894.11.

- Dahlstedt, M. 2007. “I Val(o)Frihetens Spår: Segregation, Differentiering Och Två Decennier av Skolreformer [In the Tracks of (Non)Freedom of Choice. Segregation, Differentiation and Two Decades of School Reforms.” Pedagogisk Forskning i Sverige 12 (1): 20–38.

- Demaine, J., and P. Smith. 2010. “Liberalism, Neoliberalism, Social Democracy: thin Communitarian Perspectives on Political Philosophy and Education.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 31 (4): 509–514. doi:10.1080/01425692.2010.484925.

- Erlandson, P., and D. Beach. 2014. “Ironising with Intelligence.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 35 (4): 598–614. doi:10.1080/01425692.2013.791228.

- Erlandson, P., and M. Karlsson. 2018. “From Trust to Control - the Swedish First Teacher Reform.” Teachers and Teaching 24 (1): 22–36. doi:10.1080/13540602.2017.1379390.

- Forsberg, E., and U. P. Lundgren. 2010. “Sweden: A Welfare State in Transition.” In Balancing Change and Tradition in Global Education Reform, edited by I. C. Rotberg, 181–200. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Furlong, J. 2013. “Globalization, Neoliberalism, and the Reform of Teacher Education in England.” The Educational Forum 77 (1): 28–50. doi:10.1080/00131725.2013.739017.

- Gewirtz, S. 1998. “Conceptualizing Social Justice in Education: mapping the Territory.” Journal of Education Policy 13 (4): 469–484. doi:10.1080/0268093980130402.

- Hammersley, M., and P. Atkinson. 2007. Ethnography: Principles in Practice. 3rd ed.Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, New York: Routledge.

- Hursh, D. 2005. “Neo-Liberalism, Markets and Accountability: Transforming Education and Undermining Democracy in the United States and England.” Policy Futures in Education 3 (1): 3–15. doi:10.2304/pfie.2005.3.1.6.

- Inzunza, J., J. Assael, R. Cornejo, and J. Redondo. 2019. “Public Education and Student Movements: The Chilean Rebellion under a Neoliberal Experiment.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 40 (4): 490–506. doi:10.1080/01425692.2019.1590179.

- Karlsson, M., and P. Erlandson. 2018. “Facilitators in Ambivalence.” Ethnography and Education 13 (1): 69–83. doi:10.1080/17457823.2016.1262780.

- Karlsson, M., and P. Erlandson. 2020. Administrating Existence: Teachers’ and Principals’ Coping with Swedish ‘Teachers’ Salary Boost’. in press.

- Lindensjö, B., and U. P. Lundgren. 2000. Utbildningsreformer Och Politisk Styrning [Educational Reforms and Political Governance]. Stockholm: HLS förl.

- Lundahl, L. 2002. “Sweden: Decentralization, Deregulation, Quasi-Markets - and Then What?” Journal of Education Policy 17 (6): 687–697. doi:10.1080/0268093022000032328.

- Lundahl, L. 2005. “A Matter of Self-Governance and Control. The Reconstruction of Swedish Educational Policy: 1980–2003.” European Education 37 (1): 10–25. doi:10.1080/10564934.2005.11042375.

- Morrissey, J. 2015. “Regimes of Performance: Practices of the Normalised Self in the Neoliberal University.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 36 (4): 614–634. doi:10.1080/01425692.2013.838515.

- Nozick, R. 1974. Anarchy, State, and Utopia. New York: Basic Books.

- Olssen, M. 2003. “Structuralism, Post-Structuralism, Neoliberalism: Assessing Foucault’s Legacy.” Journal of Education Policy 18 (2): 189–202.

- Olssen, M. 2010. Liberalism, Neoliberalism, Social Democracy: Thin Communitarian Perspectives on Political Philosophy and Education. New York: Routledge.

- Olssen, M. 2016. “Neoliberal Competition in Higher Education today: Research, Accountability and Impact.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 371: 129–148.

- Olssen, M., and M. A. Peters. 2005. “Neoliberalism, Higher Education and the Knowledge Economy: From the Free Market to Knowledge Capitalism.” Journal of Education Policy 20 (3): 313–345. doi:10.1080/02680930500108718.

- Ozga, J., P. Dahler-Larsen, C. Segerholm, and H. Simola. 2011. Fabricating Quality in Education: Data and Governance in Europe. London: Routledge.

- Ozga, J., and R. Jones. 2006. “Travelling and Embedded Policy: The Case of Knowledge Transfer.” Journal of Education Policy 21 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1080/02680930500391462.

- Peters, M. 2005. “Education, Freedom and Power: Third Way Governmentality, Citizen-Consumers and the Social Market.” Paper presentation, ECER, Dublin, September 7–10.

- Proposition 1989/90:41. Om kommunalt huvudmannaskap för lärare, skolledare, biträdande skolledare och syofunktionärer [Regarding municipal mandate for teachers, headmasters, vice headmasters and guidance counsellors].

- Proposition 1991/92:95. Om valfrihet och fristående skolor [Regarding freedom of choice and independent schools].

- Proposition 1992/93:230. Valfrihet i skolan [Freedom of choice in education].

- Rawls, J. 1973. A Theory of Justice. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Reyes, P., and M. Imber. 1992. “Teachers’ Perceptions of the Fairness of Their Workload and Their Commitment, Job Satisfaction, and Morale: Implications for Teacher Evaluation.” Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education 5 (3): 291–302. doi:10.1007/BF00125243.

- Rönnberg, L. 2014. “Justifying the Need for Control. Motives for Swedish National School Inspection during Two Governments.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 58 (4): 385–399. doi:10.1080/00313831.2012.732605.

- Rose, N. 1999. Governing the Soul. London: Free Association Books.

- Skolverket. 2011. Skolmarknadens Geografi [the Geography of the School Market]. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Stenlås, N. 2009. En Kår i Kläm : Läraryrket Mellan Professionella Ideal Och Statliga Reformideologier [Stuck in the Middle: The Teaching Profession Caught between Professional Ideals and State Reform Ideologies]. Stockholm: Finansdepartementet.

- Strandler, O. 2016. “Equity through Assessment? Teachers’ Mediation of Outcome-Focused Reforms in Socioeconomically Different Schools.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 60 (5): 538–553. doi:10.1080/00313831.2015.1062414.

- Strandler, O. 2017. “Constraints and Meaning-Making: Dealing with the Multifacetedness of Social Studies in Audited Teaching Practices.” Journal of Social Science Education 16 (1): 56–67.

- Swedish National Agency for Education. 2011. Läroplan För Grundskolan, Förskoleklassen Och Fritidshemmet 2011 [Curriculum for the Compulsory School, Preschool Class and the Leisure-Time Centre 2011]. Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education.

- Telhaug, A. O., O. A. Mediås, and P. Aasen. 2004. “From Collectivism to Individualism? Education as Nation Building in a Scandinavian Perspective.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 48 (2): 141–158. doi:10.1080/0031383042000198558.

- Telhaug, A. O., O. A. Mediås, and P. Aasen. 2006. “The Nordic Model in Education: Education as Part of the Political System in the Last 50 Years.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 50 (3): 245–283. doi:10.1080/00313830600743274.

- Vlachos, J. 2011. “Friskolor i Förändring [Independent Schools in Transition].” In Konkurrensens Konsekvenser: Vad Händer Med Svensk Välfärd? [The Consequences of Competition: What is Happening with Swedish Welfare?], edited by L. Hartman, 66–110. Stockholm: SNS förlag.

- Wahlström, N., and D. Sundberg. 2015. Theory-Based Evaluation of the Curriculum lgr11. Uppsala: IFAU.

- Weed, J. 2006. “Interpretive Qualitative Synthesis in the Sport & Exercise Sciences: The Meta-Interpretation Approach.” European Journal of Sport Science 6 (2): 127–139. doi:10.1080/17461390500528576.