Abstract

The article explores 5th and 6th grade pupils’ reflections on why pupils may refrain from intervening in bullying, despite understanding that bullying is wrong. The findings are based on focus group interviews conducted with 74 Swedish school pupils, who were asked for their perspectives on the various participant roles depicted in a bullying vignette. The findings were analysed using methods from constructivist grounded theory and through the theoretical lens of Goffman’s concept of social stigma. The interviewees emphasised the implications of being positioned as the ‘victim’, including being socially stigmatised, isolated, denigrated and further bullied, and suggested that the fear of being ‘singled out’ would be a main concern for pupils, and hence the driving force behind why they may refrain from intervening in defence of a victimised peer. The study thus highlights the associated processes of social stigmatisation and the non-intervention of pupils in school bullying situations.

Introduction

Bullying is a widespread problem, affecting children in schools around the world (Chester et al. Citation2015), and can be defined as a social process in which a pupil in a less powerful position is repeatedly harassed, offended, and/or excluded by others (Salmivalli Citation2010). Bullying takes place in a social context, and how peers behave when witnessing bullying seems to influence its prevalence (Kärnä et al. Citation2010; Nocentini, Menesini, and Salmivalli Citation2013; Salmivalli, Voeten, and Poskiparta Citation2011). It is thus important to understand how pupils themselves interpret and make sense of bullying situations, as their interpretations and sense-making affect how they behave in such situations (Charon Citation2009).

A ‘bystander’ can be defined as any pupil who witnesses a bullying incident (Polanin, Espelage, and Pigott Citation2012). However, not all ‘bystanders’ necessarily engage in the same way in bullying situations. According to the ‘participant role approach’ (Salmivalli Citation1999), pupils who witness bullying may act in accordance with four possible participant roles: ‘assistant’ (assists the ‘bully’ by also engaging in bullying behaviour), ‘reinforcer’ (reinforces the bullying by cheering, laughing, or providing other forms of encouragement), ‘outsider’ (is aware of the bullying but refrains from taking sides), and ‘defender’ (sides with the ‘victim’ and helps or supports them) (Salmivalli Citation2010; Salmivalli et al. Citation1996). Considering the ‘outsider’ role, it is also possible to make a further distinction between a ‘passive bystander’ who passively watches on, and an ‘outsider’ who leaves the situation (Levy and Gumpel Citation2018).

The vast majority of research on bystander behaviour in bullying has adopted a quantitative research design and mostly focused on how various bystander behaviours are associated with individual factors, such as self-efficacy, empathy, or attitudes towards bullying (see Lambe et al. Citation2019, for a review). Only a small number of quantitative studies have examined the importance of contextual factors, such as popularity, social status, peer norms, and classroom climate, to bystander behaviours (e.g. Barhight et al. Citation2017; Caravita, Gini, and Pozzoli Citation2012; Thornberg et al. Citation2017). However, over the past decade or so, there has been a growing body of qualitative research on how children and youth explain various bystander actions and reactions in bullying situations (e.g. Chen, Chang, and Cheng Citation2016; Forsberg, Thornberg, and Samuelsson Citation2014; Strindberg, Horton, and Thornberg Citation2019; Thornberg, Landgren, and Wiman Citation2018). Such studies have highlighted the importance of socially perceiving the ‘victim’ as ‘different’ (e.g. as ‘odd’ or ‘not like us’), as well as the social processes of ‘not fitting in’ to pupils’ explanations for why they engage in bullying or refrain from intervening. They have also suggested possible links between pupils’ non-intervention in bullying situations and their fears of either becoming the next ‘victim’ or being associated with someone positioned as a ‘victim’ (Forsberg, Thornberg, and Samuelsson Citation2014; Forsberg et al. Citation2018; Thornberg Citation2010, Citation2015; Thornberg, Landgren, and Wiman Citation2018).

Although the importance of stigma has been highlighted in several studies on school bullying, this has often taken the form of distinguishing between what may be termed ‘stigma-based’ bullying and ‘non-stigma-based’ bullying (e.g. Earnshaw et al. Citation2018; Gower et al. Citation2018; Rosenthal et al. Citation2015). Although the term ‘stigma-based bullying’ is used to refer to bullying that is rooted in discriminatory grounds such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, class, religious belief, and so on, the term ‘non-stigma-based bullying’ is used to refer to bullying that is not connected to such discriminatory grounds. However, distinguishing between ‘stigma-based’ and ‘non-stigma-based’ bullying is problematic because, as Goffman (Citation1986, 130) argues, ‘stigma management is a general feature of society, a process occurring wherever there are identity norms’. Some researchers have thus considered the relations between stigma and school bullying more generally, suggesting that stigma processes are central to the development of bullying relations (e.g. Horton Citation2019a; Huggins Citation2016; Thornberg Citation2015; Walton Citation2011).

However, as yet, there has been little investigation of the processes through which pupils’ social perceptions of difference and their fears of being subjected to bullying relate to their non-intervention in bullying situations and their taking on of the ‘passive bystander’ or ‘outsider’ roles. Likewise, there has been little in-depth consideration of the ways in which stigma processes relate to these participant roles and non-intervention in bullying situations, or of how pupils themselves reflect over these processes. In this study, we utilise Goffman’s (Citation1986) theory of social stigma as a heuristic tool, or theoretical ‘lens’ (Kelle Citation1995), for analysing Swedish school pupils’ perspectives on the roles of ‘victim(s)’, ‘passive bystander(s)’, and ‘outsider(s)’ in bullying situations. In doing so, we look more in-depth at the stigma processes involved in order to better understand why pupils may refrain from intervening in bullying situations, despite understanding that bullying is wrong.

Method

The findings in this article stem from 22 same-sex focus group interviews with a total of 74 pupils from 7 school classes in grades 5 to 6 (i.e. 11–12 years of age) at two public primary schools in socioeconomically diverse areas in Sweden (26 girls and 11 boys in one school, and 24 girls and 13 boys in the other; a total of 68% girls and 32% boys). In conducting the research, ethical guidelines were adhered to and, prior to beginning the data collection, approval was obtained from the regional ethical review board. The principals of the schools were provided with information about the background and purpose of the study, and prior to beginning the study, the first author presented himself to the respective classes and told the pupils and teachers about himself and the purpose of the study. Informed consent was obtained from both the pupils and their parents/guardians. Pupils were informed that their participation was voluntary, that they were free to withdraw their consent at any time, that the information they provided was confidential and would be anonymised, and that the information would only be used for research purposes. After the interviews, the pupils were informed that there was a team at the respective school to whom they could turn in case of bullying and they were also provided with information about BRIS, an anonymous Swedish helpline for children and adolescents.

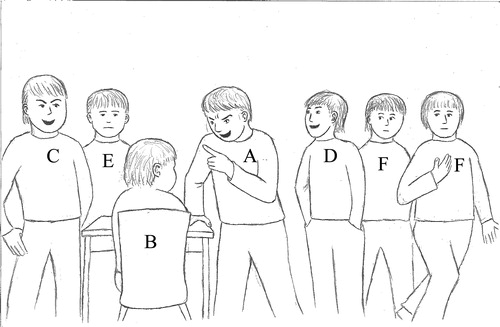

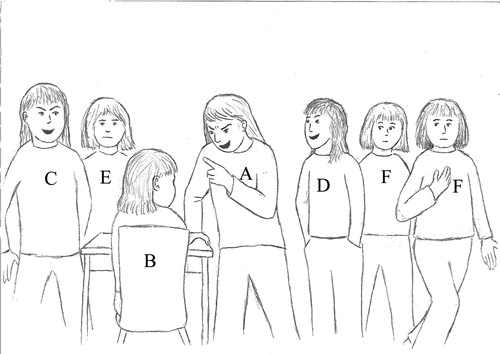

Using the same approach as Teräsahjo and Salmivalli (Citation2003), the pupils were asked to draw social maps (i.e. to draw the groups and/or pairs in their class and name the pupils belonging to each group/pair). The social maps were compared by the first author, who then formed the focus groups on the basis of the social maps and in consultation with the class teachers. The interviews were conducted by the first author and were combined with the use of a school bullying vignette, developed by the third author, depicting a fictive bullying scenario involving a group of six boys or girls (depending on whether the interview was with boys or girls). The fictive bullying scenario encompassed children taking on five different roles derived from the participant role approach (Salmivalli et al. Citation1996): one ‘bully’ (labelled A in the vignette), one ‘victim’ (labelled B), one ‘assistant’ helping the ‘bully’ and joining in the bullying (C), one ‘reinforcer’ laughing and cheering on the bullying (D), one ‘passive bystander’ passively watching on (E), and two ‘outsiders’ leaving the situation (F) (see and in the Appendix). In the focus groups, pupils were told that A bullies B at least a couple of times every week, and were then asked why the various children depicted in the vignette might behave according to the various roles rather than defending the ‘victim’ (B), despite understanding that bullying is wrong.

The vignettes were used as stimuli for eliciting extended discussions about school bullying and bystander roles and to allow us to explore and analyse important nuances from the pupils’ own perspectives (Bosacki, Marini, and Dane Citation2006; Mishna, Saini, and Solomon Citation2009; Patton et al. Citation2017), whereas at the same time providing the pupils with a means of discussing sensitive issues without directly discussing their own bullying experiences (Barter and Renold Citation1999; Jenkins et al. Citation2010; Wilks Citation2004). Although asking pupils to reflect on behaviour depicted in a vignette does not necessarily reflect real-life responses or how pupils would assess the behaviour of actual peers, it does provide an important opportunity for pupils to discuss why pupils may refrain from intervening in bullying situations without the need to justify or rationalise why they themselves may have acted in a particular way. The vignette used in this study did not include a ‘defender’ role, which could have provided further opportunity for pupils to reflect on the possible rationales for intervening or not. However, as the aim of this study was to better understand why pupils may refrain from intervening in bullying situations, we decided not to include a ‘defender’ role in the vignette.

All the focus group interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, and analysed using methods from constructivist grounded theory. This entailed initial, focused and theoretical coding, memo writing, and constant comparison (Charmaz Citation2014). Through the posing of questions such as, ‘What do the data suggest?’, ‘Which processes seem to be at stake here?’, and ‘What are the main concerns faced by the participants in the actual scene?’, the analysis aimed to explore social processes in the focus group data (Charmaz Citation2014). Due to its emerging fit with and relevance to the data, Goffman’s (Citation1986) theory of social stigma was used as a theoretical lens during the latter part of the analysis in order to better understand the interviewees’ reflections on why pupils may refrain from intervening in bullying situations, despite understanding that bullying is wrong.

Social difference, social stigma, and school bullying

Social stigma is a concept that illustrates how members of social categories or groups, of whom others have negative or stereotyped views, are discriminated against by other members on the grounds of these negative views. In its most basic sense, social stigma refers to a mark or a sign of disgrace or discredit (Goffman Citation1986). According to Goffman (Citation1986), every society divides people into social categories based on perceptions of what is ‘normal’ for its members and related expectations about how other people ‘should be’. Thus, a stigma is not an inherent trait of someone, but rather a relational matter, which is socially constituted and rooted in social interaction. The meaning given to particular traits in this sense varies between social contexts, and something highly valued in one context can thus be regarded as discrediting or stigmatising in another.

Goffman (Citation1986, 4) suggests that the reasons for why someone may be stigmatised may be due to perceived ‘abominations of the body’, ‘blemishes of individual character’, or ‘the tribal stigmas of race, nation, and religion’. Put another way, it is possible to distinguish more broadly between physical deviations of people, deviations in individual character or behaviour, and deviations based on group membership (Goffman Citation1986). All of these distinctions entail that the individual is perceived as having a trait that he/she cannot escape (but can try to hide), making those with whom they interact shun them and overlook the presence of more positive traits. Thus, the social stigma acts as a kind of social information, a symbol or sign of one’s social identity, and has effects both for the one who is stigmatised and for those they meet (Goffman Citation1986).

Stigma processes can be broken down into six different components (Goffman Citation1986; Huggins Citation2016; Link and Phelan Citation2001). First, particular individuals and/or groups are identified as ‘other’ and labelled through the use of special stigma-terms. Secondly, those labelled are linked to negative stereotypes, meaning that they are assigned a series of imperfections on the basis of a single perceived imperfection. Thirdly, those labelled are isolated through their categorisation as ‘other’ and hence their distance from ‘us’. Fourthly, they are denigrated, reduced in status and discriminated against. Fifthly, stigma is reinforced through the maintenance of the boundaries between ‘us’ and ‘them’. Finally, such stigmatisation is contingent on broader societal power relations that provide the basis for the other stigma components (Goffman Citation1986; Huggins Citation2016; Link and Phelan Citation2001). The one who is stigmatised is thus identified, labelled, stereotyped, isolated, denigrated, and discriminated against within a power relationship that provides the differential points of reference.

By offering an included, non-stigmatised ‘we’, stigma is also a means through which the group of non-stigmatised individuals may distance themselves from ‘the other(s)’ (Goffman Citation1986). In this sense, stigma can serve several functions for those who stigmatise, such as self-esteem enhancement, anxiety buffering through downward comparison, as well as providing a subjective sense of well-being (Heatherton et al. Citation2000). For the one who is stigmatised, on the other hand, the stigma may lead to the assimilation of negative perceptions and self-stigmatisation (Goffman Citation1986; Thornberg Citation2015). For those who come into contact with the one who is stigmatised, there is a risk that the stigma spreads and that they too lose their credibility through social contamination (Goffman Citation1986; Thornberg Citation2015). In other words, the one who is stigmatised is perceived to pose a threat (Goffman Citation1986; Huggins Citation2016). This obviously has implications for bullying situations and the decision-making of ‘passive bystanders’ and ‘outsiders’.

Results

In this study, we are particularly interested in understanding why pupils may refrain from intervening and instead take on a ‘passive bystander’ or ‘outsider’ role in bullying situations. However, while analysing the focus group data, we realised that in order to do so, we also needed to understand pupils’ perceptions of the ‘victim’ role. In reflecting on the ‘victim’ role, as well as on the ‘passive bystander’ and ‘outsider’ roles, the interviewees, above all, returned to how the perceived risk of being singled out (or ending up in the same situation as the portrayed ‘victim’) would be a main concern for pupils involved in bullying situations. The findings are presented in two parts: we first present the pupils’ reflections on the ‘victim’ role. Thereafter, we present their reflections on the ‘passive bystander’ and ‘outsider’ roles, including how these roles were suggested to be tied up with pupils’ perceptions (and fear) of the ‘victim’ role.

School bullying, social difference, and pupils’ perceptions of the ‘victim’ role

In discussing the ‘victim’ role (B) in the vignette, the interviewees returned to the notion of the ‘victim’ as someone who possessed an undesired difference, and, in doing so, identified the ‘victim’ as ‘other’. In elaborating on the differentness of the ‘victim’, a number of interviewees related difference to aspects of appearance, or physical deviation. Some identified distinctions based on the size and physical weakness of the person being bullied. One boy, for example, suggested, ‘Maybe he is smaller’, whereas another boy in the same group proposed, ‘Maybe he isn’t as strong or can’t defend himself’. Although, on one level, these responses point to traditional individual psychological understandings of school bullying among boys and power relations founded on unequal strength and size, they also point to broader societal gendered discourses about how males should ‘be’ (e.g. big and/or strong) or what they should be capable of (e.g. defending themselves) in order to be considered appropriately masculine. Some boys also suggested that the ‘victim’ could be identified as ‘other’ based on their clothes and clothing style. As one boy explained, ‘Maybe he doesn’t have the best football shoes. Maybe he doesn’t have the best-looking clothes’. In a similar vein, a boy from another group pointed out, ‘Maybe he doesn’t have the same style as everyone else’. These boys point not only to masculine norms regarding how boys should dress but also to the importance of class and consumer capacity to a boy’s perceived ability to adhere to such norms. In this sense, not having ‘the best football shoes’ or ‘the best-looking clothes’, or not having ‘the same style as everyone else’ provides a form of social information about the ‘victim’, which marks them out as different and thus worthy of the blame of others (Goffman Citation1986).

Some of the interviewees pointed to the perceived individual character of the person being bullied rather than any physical deviations. One girl, for example, related the perceived differentness of the ‘victim’ to their position at the bottom of the peer hierarchy and suggested that this position was due to their ‘weak’ character. As she explained, ‘Those who are furthest down are those who are ‘weak’, who don’t dare to talk back’. Likewise, another girl suggested, ‘Maybe B doesn’t dare to stand up for herself’. These girls thus attribute weakness to a lack of daring ‘to talk back’ or ‘to stand up’ for oneself, and, in doing so, identify an attribute (i.e. weakness) that could lead to that person being socially reduced and subjected to bullying. A number of interviewees also suggested that having a ‘shy’ character could be a reason for why someone is bullied. As one girl stated, ‘Maybe she is the shy one’. Likewise, another girl suggested, ‘Maybe she doesn’t raise her hand so much in school, like in the way that she doesn’t show herself so much’. These girls suggest that the differentness of the person being bullied is related to their lack of social visibility in the peer group. However, as one girl pointed out, the differentness of the ‘victim’ could also be related to them being perceived as ‘annoying’ or as taking up too much space. As she explained, ‘Maybe B was annoying or she took up a lot of space’.

Although the above responses suggest that the process of identifying negative attributes was similar for boys and girls, the differential points of reference appeared to be different, with boys tending to identify physical attributes such as lack of size or strength, or dressing ‘inappropriately’, for example, and girls tending to identify character traits such as weakness, shyness, or being ‘annoying’.

Some interviewees more specifically connected the bullying to the perceived behaviour of the person being bullied, suggesting that certain behaviours may contribute to the identification of difference. A number of the interviewees suggested that scholasticism (e.g. studying hard and getting good grades) may lead to the person being identified as deviant. As one girl explained, for example, ‘B might be good at drawing or good at schoolwork or something’. In a similar vein, a number of boys suggested that the person being bullied was perceived to get too good grades and thus to be studying too hard. Illustrating the ways in which the identification of difference may be linked to negative stereotypes and lead to that person being negatively labelled, one boy suggested that the boy being bullied ‘might study too much and so they call him a nerd and stuff, [because] he passes tests and everything’. Highlighting the ways in which stigma labels, such as ‘nerd’ may be assigned to those designated as ‘other’ and how one attribute may overshadow other attributes, the same boy elaborated, ‘They’re like, you can say swots and so on … and they get really good grades’. This boy’s elaboration points to a shift here from labelling someone a ‘nerd’ to perceiving them as a ‘swot’. In this sense, the ‘victim’ is distinguished as fundamentally ‘other’ and isolated through their categorisation as ‘nerd’ or ‘swot’ and thus their difference from those ‘normal’ boys, who do not ‘study too much’ or get ‘really good grades’.

Although the interviewees above pointed to aspects of ‘personal front’, such as individual appearance or manner (Goffman Citation1986, 34), others pointed to issues of friendship and group membership. Two boys from one of the groups, for example, suggested that not joining in and sharing the interests of others (e.g. playing sports), and thus being part of the group, may increase the risk of being singled out as different. Some boys related such perceived differentness to social isolation and an increased risk of being subjected to bullying because of a lack of friends who can help prevent it from occurring. As one boy explained, for example, ‘And he maybe doesn’t have as many friends or something … who can protect him’. This illustrates the way in which stigma may be reinforced through the maintenance of boundaries between those who are perceived to belong, and those who are not.

As illustrated, there may be a number of different grounds for someone to be constructed as different, suggesting that differentness is not connected to the inherent characteristics of someone, but is rather locally and socially constructed by pupils, and related to broader social and societal norms, regulating pupils’ perceptions of deviance, differentness, and normality. In this sense, the demarcation between being perceived as ‘normal’ or ‘different’ seems to be about not crossing socially policed boundaries related to physical attributes, individual character and behaviour, and/or group membership. If someone crosses these boundaries, and is hence perceived to deviate or stand out too much from their peers, they may risk the policing of their peers through bullying behaviour. This was explained by a girl, who pointed to the ways in which someone may become increasingly stigmatised and subjected to bullying by their peers:

Already from the start, when the class is formed, everyone has roles, and it is hard to escape them. And then perhaps there is someone who thinks, maybe thinks that the person is disgusting or ugly or whatever, and then you think of more and more stuff that the person does, and eventually it turns into bullying. You start to get annoyed at everything that person does, at that person’s personality, and then you might start doing kind of mean things to them and so on.

This girl’s explanation exemplifies how pupils may be socially positioned very early during the formation of the class and that it may not only be very difficult for a pupil to escape their allocated position but their position may also negatively influence the ways in which they are perceived and treated. As the girl points out, a pupil may be identified as ‘other’ because of perceptions about their ‘personal front’, in terms of their appearance (e.g. ‘ugly’) or manner (e.g. ‘disgusting’). This may then lead to the assignment of a series of imperfections (i.e. ‘more and more stuff’) and eventual stereotyping that ‘everything that person does’ is ‘annoying’ and attributable to ‘that person’s personality’. That pupil thus becomes distanced from the ‘normal’ pupils and increasingly socially isolated, reduced in status, and denigrated through bullying and the doing of ‘mean things’.

Some of the groups suggested that once the bullying becomes common enough in a particular class, the bullying may be de-dramatised, neutralised and something that pupils no longer reflect over. As one girl explained, ‘The class might get used to the fact that she’s bullied, and then she can’t do anything! It becomes automatic each time she [B] passes by’. In this sense, the boundaries between ‘us’ and ‘them’ are maintained, potentially almost automatically, and the stigma of the ‘victim’ is reinforced. The one who is stigmatised and subjected to victimisation may no longer be subject to the same moral codes as the non-stigmatised. Rather, the bullying of that person may no longer even be perceived as bullying because it has become so routine. Indeed, as another girl in the same group added, ‘then your friends might not even think about it as bullying, because it’s so common’. These girls suggest that rather than being about the harmful intention of pupils, bullying may instead be part of a social rejection process through which the ‘victim’ is stigmatised as ‘other’ and ‘not like us’.

Some of the interviewees suggested that the position of ‘victim’ is a difficult one to escape from. As one boy put it, ‘They patronise him, talk behind his back, say mean things, maybe even beat him/…/If pupil B tries to do something, A can just push him down again and again’. This boy’s explanation suggests that someone who is bullied may not be able to stand up for themselves because this may lead to even more bullying and to them being repeatedly pushed back down. This situation may lead to the ‘victim’ no longer daring to stand up for themselves because of the realisation that any attempt to do so will lead to further bullying. Indeed, as another boy put it, ‘He doesn’t dare to stand up because he knows that they will just push him down again’. These boys’ responses point to the ways in which the boundaries between those who are perceived to be ‘normal’ and those who are perceived as ‘other’ are maintained, and to how the socially reduced position of the ‘victim’ is reinforced.

Once positioned as a ‘victim’, the situation may thus be hard to change without the help of others. As one girl stated, ‘Once you are bullied like B, then it’s difficult to stop being bullied/…/B can’t actually do anything by themselves, rather others have to help them out’. Although this girl suggests that the ‘victim’ cannot stop the bullying to which they are subjected without someone else’s help, other pupils also pointed out that seeking help from teachers or parents may serve to exacerbate the problem. As one girl put it, for example, ‘If B tells a teacher, then they will be seen as a “snitch” who just exaggerates’. In attempting to seek help, the ‘victim’ may thus risk further labelling (e.g. as a ‘snitch’) and stigmatisation, and the reinforcement of their position as ‘other’. As one boy explained, telling about the bullying may lead to even further bullying if those doing the bullying find out that the person has told, or ‘snitched’, on them: ‘B doesn’t dare to tell his parents because there is a risk that it comes out that they are bullying, and then they will do it even more … because B snitched to his parents’. The person being bullied may even be pre-warned and threatened with more violence in the event that they tell about the bullying. This was suggested by a girl, who said, ‘Maybe A says, “If you tell anyone, this will happen”. Maybe she [A] says, “You’re gonna get beaten” ’. The pupil being bullied is thus caught in a Catch-22 situation, whereby they require the help of others to stop the bullying but are unable to seek help without making the situation worse. At the same time, other pupils may choose to refrain from intervening and may instead take on a ‘passive bystander’ or ‘outsider’ role.

Social stigmatisation, rejection, and non-intervention in bullying situations

In explaining non-intervention in bullying situations, some of the interviewees pointed out that pupils may allow bullying to occur because of the perceived differentness of the ‘victim’ and because of a perception that the situation has no thing to do with them. As one boy explained:

Then they might kind of think that ‘he’s a bit weird, we’ll let them do it, we shouldn’t care about it, it’s not our problem’, something like that/…/They think he’s weird and that ‘he deserves to get taught a little lesson’.

This boy’s explanation illustrates the extent to which the stereotyped perception of the ‘victim’ as ‘weird’ may lead those not involved in the bullying to justify the bullying and to refrain from intervening because of a perception that the one being bullied ‘deserves to get taught a little lesson’.

However, many of the interviewees instead suggested that a main concern for pupils in the ‘bystander’ and ‘outsider’ roles would be about protecting their own social self. In a number of focus groups, interviewees pointed out that lack of intervention may be a means through which pupils seek to protect themselves from being associated with the victim and potentially being bullied themselves. Even in cases where the one being bullied is liked by the person not intervening, and even when pupils sympathise with a victimised peer, they may still place self-preservation ahead of attempts at intervening. One girl, for example, reflected on what she thought the girl adopting a ‘passive bystander’ role in the vignette might be thinking:

She [E] may think it is difficult [to pick a side] but also rather easy. Maybe she actually thinks that B is the kindest friend. She just does not dare to walk up and get B. If she chooses B, she might be bullied instead.

As this girl illustrates, even when a ‘passive bystander’ thinks highly of the ‘victim’, she may not dare to help or support the ‘victim’ and thus take on the role of ‘defender’ because the risk of doing so is such that she may in turn be subjected to bullying. In this sense, then, there is a perceived risk that the social stigma of the ‘victim’ may spread and lead to the social contamination of the one attempting to help.

Similar explanations were given by pupils when discussing the ‘outsider’ role in the vignette. As another girl elaborated:

It is not like they are selfish but perhaps they kind of feel like, ‘Imagine if it’s me that gets bullied’, and then … ‘I would like to support B but then there is a risk that I get bullied, so like, I don’t want to take that risk because it’s going well for me right now anyway … so I’m not going to do anything’.

This girl’s elaboration highlights that even ‘outsiders’ may like to support the person being bullied, and thus take on a ‘defender’ role, but may refrain from doing so because of the risk of not only being bullied but also of being socially reduced from a position where it is currently ‘going well’.

As illustrated above by some of the interviewees’ explanations, non-intervention in bullying may be related to perceptions of bullying as ‘justified’. However, many of the interviewees suggested that a main concern for pupils in the ‘passive bystander’ and ‘outsider’ roles would be about protecting their own social self, not least by avoiding the risk of becoming the next ‘victim’ and ending up in that painful and socially devastating situation themselves. This, in turn, would motivate them to refrain from intervening and to stay out of the situation as much as they can, regardless of whether or not they sympathise with the one being bullied, or of whether they understand that bullying is wrong.

Discussion

In this study, we have explored Swedish 5th and 6th grade pupils’ perspectives on the roles of ‘victim(s)’, ‘passive bystander(s)’, and ‘outsider(s)’ in bullying situations, and their explanations for why pupils may refrain from intervening in bullying situations, despite understanding that bullying is wrong. Goffman’s theory of stigma has been used as a theoretical lens through which to analyse the pupils’ explanations. However, rather than confining our discussion of stigma to particular kinds of group-based bullying, such as racial bullying or homophobic bullying, we have sought to utilise the concept of stigma as a means of understanding the relations between identity norms and school bullying more generally.

Our findings point to a number of components of stigma processes (i.e. identification, labelling, stereotyping, isolation, denigration, reinforcement, and power relations), all of which are highly relevant for understanding school bullying (Huggins Citation2016; Link and Phelan Citation2001). In line with other studies (e.g. Hamarus and Kaikkonen Citation2008; Teräsahjo and Salmivalli Citation2003; Thornberg Citation2010, Citation2015, Citation2018; Wójcik Citation2018), our findings highlight a number of ways in which pupils are identified as different by their peers. Indeed, the interviewees in this study point to certain aspects which they suggest would position the ‘victim(s)’ as discreditable in the eyes of their peers, hence exposing them to possible discrediting, e.g. in terms of physical deviations (e.g. size, strength, or clothing), individual character or behaviour (e.g. being shy, annoying, or good at schoolwork) or group membership (e.g. not joining in afterschool activities).

Our findings also illuminate the ways in which those pupils who are identified as different may be negatively labelled through the use of stigma terms, such as ‘swot’ or ‘nerd’ for example, and thus echo findings from school masculinities research (e.g. Connell Citation1989; Martino Citation1999; Willis Citation1977). Such labelling provides social information about that pupil and may lead to them being stereotyped and understood in terms of their ‘deviant’ traits, as ‘a bit weird’ for example. This draws attention to the tension between macro- and micro-level norms and how the macro norms of society may be expressed at the micro-level, i.e. in the schooled life of pupils, for example, by labelling someone as deviant. As Goffman (Citation1983, 8) pointed out, people can be sorted both individually and categorically, but such ‘people-processing encounters’ are situational and connected to broader social structures such as age, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, class, and so on. Hence, the identification of a pupil as ‘small’, ‘weak’, or as having the wrong clothing style, can be understood in terms of broader social structures related to gender, sexuality, and class, for example (Davies Citation2011; Horton Citation2011, Citation2019b; Pascoe Citation2013; Ringrose and Renold Citation2010; Thornberg Citation2018; Walton Citation2011).

By being negatively labelled and stereotyped, someone may be marked out as inherently different from the rest of the peer group and, through their marking out as different, a stigmatised pupil may be increasingly isolated, and hence cut off from the support of friends, not least due to their perceived differentness and because of the associated risk of social contamination that they are perceived to embody. As has been highlighted elsewhere (e.g. Forsberg and Thornberg Citation2016; Thornberg Citation2015), someone’s perceived differentness may provide other pupils with a means through which to justify the subsequent bullying behaviour through which that person is denigrated. The denigration of the stigmatised pupil may then be reinforced through such justifications and through the continued positioning of the pupil as a discredited ‘other’. Although someone who is victimised may not passively accept their isolated situation, their stigmatised position may nonetheless be difficult to escape or change, as other pupils may try to push them back down, threaten them, or negatively label them, as a ‘snitch’ for example, if they seek the help of teachers or parents. This not only illustrates how perceived difference and social stigmatisation may become established among school children, but also highlights the possible consequences that peer intervention may have for the one(s) defending.

Whenever people come into face-to-face contact with one another, they become part of what Goffman (Citation1983) referred to as ‘the interaction order’, wherein information is provided to, and gleaned from, those with whom they interact. People thus become vulnerable to the discrediting of self by others (Goffman Citation1983). In trying to deal with the possible discredit of others, people may attempt to present themselves in particular ways, for example as a non-friend to the ‘victim’. As illustrated by the interviewees in this study, even when other pupils may actually like the pupil being bullied, they may nonetheless feel restrained in their ability to help because of the related risk of themselves being socially stigmatised, excluded and bullied. Anxiety associated with the perceived risk of social exclusion (Søndergaard Citation2012; Søndergaard and Hansen Citation2018) may be such that pupils refrain from intervening in bullying situations and thus put their presentation, and preservation, of social self before any moral concerns they may have for their stigmatised peer(s).

Rather than decontextualising bullying incidents, by referring to the individual characteristics of ‘bullies’ or ‘victims’ or reducing power to a discussion of strength or number for example, our findings suggest that bullying situations are connected to social processes of inclusion and exclusion, and underpinned by power relations and associated understandings of difference. Thus, a central component of both stigma processes and bullying relations is the power relations that underpin them. Goffman (Citation1990) suggested that power is about the capacity to ‘control the conduct of others (p. 15). Through the labelling, stereotyping, isolation and denigration of particular pupils, those engaging in bullying behaviour not only position the pupil being bullied as ‘other’ and control their subsequent conduct, but also control the conduct of those pupils (i.e. ‘passive bystanders’ and ‘outsiders’) who may otherwise seek to help the pupil being bullied. This occurs through a ‘coercive exchange’, which Goffman (Citation1983) suggested is ‘that tacit bargain through which we cooperate with the aggressor in exchange for the promise of not being harmed as much as our circumstances allow’ (p. 4). This helps explain not only why some pupils risk being bullied, but also why pupils adopting a ‘passive bystander’ or ‘outsider’ role in bullying may refrain from intervening in defence of a victimised peer, despite understanding that bullying is wrong.

Although this is not to say that pupils should not speak up or distance themselves from bullying when it happens, our findings have important implications for the use of ‘bystander interventions’ as means through which to counteract bullying in schools, not least because they illuminate what it may entail for pupils to act as ‘defenders’ in bullying situations. Calling on pupils to intervene in or report bullying situations fails to adequately account for the stigma processes involved and the risks associated with intervening and reporting. This study highlights the importance of working preventively in schools, classrooms and peer groups, by acknowledging the interconnectedness of social categorisations, stigma processes and broader societal power relations, and promoting inclusive social relations based on understanding and openness to difference (Davies Citation2011; Horton Citation2019b; Jacobson Citation2007; Walton Citation2015). Thus, rather than simply encouraging individual pupils to intervene as ‘defenders’, or to report bullying situations, our findings point to the importance of building caring and supportive school, classroom and peer cultures together with pupils, wherein there is a collective readiness to stand up for ‘victims’ and wherein there is no longer a need to fear being singled out.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barhight, Lydia R., Julie A. Hubbard, Stevie N. Grassetti, and Michael T. Morrow. 2017. “Relations between Actual Group Norms, Perceived Peer Behavior, and Bystander Children's Intervention to Bullying.” Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 46 (3): 394–400. doi:10.1080/15374416.2015.1046180.

- Barter, Christine, and Emma Renold. 1999. “The Use of Vignettes in Qualitative Research.” Social Research Update 25. http://sru.soc.surrey.ac.uk/SRU25.html.

- Bosacki, Sandra, Zopito Marini, and Andrew Dane. 2006. “Voices from the Classroom: Pictorial and Narrative Representations of Children’s Bullying Experiences.” Journal of Moral Education 35 (2): 231–245. doi:10.1080/03057240600681769.

- Caravita, Simona C. S., Gianluca Gini, and Tiziana Pozzoli. 2012. “Main and Moderated Effects of Moral Cognition and Status on Bullying and Defending.” Aggressive Behavior 38 (6): 456–468. doi:10.1002/ab.21447.

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Charon, Joel M. 2009. Symbolic Interactionism: An Introduction, an Interpretation, an Integration. 10th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Chen, Li-Ming, Lennon Y. C. Chang, and Ying-Yao Cheng. 2016. “Choosing to Be a Defender or an Outsider in a School Bullying Incident: Determining Factors and the Defending Process.” School Psychology International 37 (3): 289–302. doi:10.1177/0143034316632282.

- Chester, K. L., M. Callaghan, A. Cosma, P. Donnelly, W. Craig, S. Walsh, M. Molcho, et al. 2015. “Cross-National Time Trends in Bullying Victimization in 33 Countries among Children Aged 11, 13 and 15 from 2002 to 2010.” The European Journal of Public Health 25 (suppl 2): 61–64. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckv029.

- Connell, Raewyn W. 1989. “Cool Guys, Swots and Wimps: The Interplay of Masculinity and Education.” Oxford Review of Education 15 (3): 291–303. doi:10.1080/0305498890150309.

- Davies, Bronwyn. 2011. “Bullies as Guardians of the Moral Order or an Ethic of Truths?” Children and Society 25 (4): 278–286. doi:10.1111/j.1099-0860.2011.00380.x.

- Earnshaw, Valerie A., Sari L. Reisner, David Menino, V. Paul Poteat, Laura M. Bogart, Tia N. Barnes, Mark A. Schuster, et al. 2018. “Stigma-Based Bullying Interventions: A Systematic Review.” Developmental Review 48: 178–200. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2018.02.001.

- Forsberg, Camilla, and Robert Thornberg. 2016. “The Social Ordering of Belonging: Children’s Perspectives on Bullying.” International Journal of Educational Research 78: 13–23. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2016.05.008.

- Forsberg, Camilla, Robert Thornberg, and Marcus Samuelsson. 2014. “Bystanders to Bullying: Fourth- to Seventh-Grade Students’ Perspectives on Their Reactions.” Research Papers in Education 29 (5): 557–576. doi:10.1080/02671522.2013.878375.

- Forsberg, Camilla, Laura Wood, Jennifer Smith, Kris Varjas, Joel Meyers, Tomas Jungert, Robert Thornberg, et al. 2018. “Students’ Views of Factors Affecting Their Bystander Behaviors in Response to School Bullying: A Cross- Collaborative Conceptual Qualitative Analysis.” Research Papers in Education 33 (1): 127–142. doi:10.1080/02671522.2016.1271001.

- Goffman, Erving. 1983. “The Interaction Order: American Sociological Association, 1982 Presidential Address.” American Sociological Review 48 (1): 1–17. doi:10.2307/2095141.

- Goffman, Erving. 1986. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York: Simon & Schuster Inc.

- Goffman, Erving. 1990. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. London: Penguin.

- Gower, Amy L., G. Nic Rider, Barbara J. McMorris, and Marla E. Eisenberg. 2018. “Bullying Victimization among LGBTQ Youth: Critical Issues and Future Directions.” Current Sexual Health Reports 10 (4): 246–249. doi:10.1007/s11930-018-0169-y.

- Hamarus, Päivi, and Pauli Kaikkonen. 2008. “School Bullying as a Creator of Pupil Peer Pressure.” Educational Research 50 (4): 333–345. doi:10.1080/00131880802499779.

- Heatherton, Todd F., Robert E. Kleck, Michelle R. Hebl, and Jay G. Hull, eds. 2000. The Social Psychology of Stigma. New York: Guildford.

- Horton, Paul. 2011. “School Bullying and Social and Moral Orders.” Children and Society 25 (4): 268–277. doi:10.1111/j.1099-0860.2011.00377.x.

- Horton, Paul. 2019a. “School Bullying and Bare Life: Challenging the State of Exception.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 51 (14): 1444–1453. doi:10.1080/00131857.2018.1557043.

- Horton, Paul. 2019b. “Reframing School Bullying: The Question of Power and Its Analytical Implications.” Power and Education. doi:10.1177/1757743819884955.

- Huggins, Mike. 2016. “Stigma is the Origin of Bullying.” Journal of Catholic Education 19 (3): 166–196. doi:10.15365/joce.1903092016.

- Jacobson, Ronald B. 2007. “A Lost Horizon: The Experience of an Other and School Bullying.” Studies in Philosophy and Education 26 (4): 297–317. doi:10.1007/s11217-007-9026-6.

- Jenkins, Nicholas, Michael Bloor, Jan Fischer, Lee Berney, and Joanne Neale. 2010. “Putting It in Context: The Use of Vignettes in Qualitative Interviewing.” Qualitative Research 10 (2): 175–198. doi:10.1177/1468794109356737.

- Kärnä, Antti, Voeten, Marinus, Poskiparta, Elisa, and Salmivalli, Christina. 2010. “Vulnerable Children in Varying Classroom Contexts: Bystanders' Behaviors Moderate the Effects of Risk Factors on Victimization.” Merrill-Palmer Quarterly 56 (3): 261–282. doi:10.1353/mpq.0.0052.

- Kelle, Udo. 1995. “Theories as Heuristic Tools in Qualitative Research.” In Openness in Research: The Tension between Self and Other, edited by Ilja Maso, 33–50. Assen: Van Gorcum.

- Lambe, Laura J., Victoria Della Cioppa, Irene K. Hong, and Wendy M. Craig. 2019. “Standing up to Bullying: A Social Ecological Review of Peer Defending in Offline and Online Contexts.” Aggression and Violent Behavior 45: 51–74. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2018.05.007.

- Levy, Michal, and Thomas P. Gumpel. 2018. “The Interplay between Bystanders’ Intervention Styles: An Examination of the ‘Bullying Circle’ Approach.” Journal of School Violence 17 (3): 339–353. doi:10.1080/15388220.2017.1368396.

- Link, Bruce G., and Jo C. Phelan. 2001. “Conceptualizing Stigma.” Annual Review of Sociology 27 (1): 363–385. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363.

- Martino, Wayne. 1999. “Cool Boys’, ‘Party Animals’, ‘Squids’ and ‘Poofters’: Interrogating the Dynamics and Politics of Adolescent Masculinities in School.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 20 (2): 239–263. doi:10.1080/01425699995434.

- Mishna, Faye, Michael Saini, and Steven Solomon. 2009. “Ongoing and Online: Children and Youth’s Perceptions of Cyberbullying.” Children and Youth Services Review 31 (12): 1222–1228. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.05.004.

- Nocentini, Annalaura, Ersilia Menesini, and Christina Salmivalli. 2013. “Level and Change of Bullying Behavior during High School: A Multilevel Growth Curve Analysis.” Journal of Adolescence 36 (3): 495–505. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.02.004.

- Pascoe, C. J. 2013. “Notes on a Sociology of Bullying: Young Men's Homophobia as Gender Socialization.” QED Inaugural Issue 87–103. doi:10.1353/qed.2013.0013.

- Patton, Desmond Upton, Jun Sung Hong, Sadiq Patel, and Michael J. Kral. 2017. “A Systematic Review of Research Strategies Used in Qualitative Studies on School Bullying and Victimization.” Trauma, Violence and Abuse 18 (1): 3–16. doi:10.1177/1524838015588502.

- Polanin, Joshua R., Dorothy L. Espelage, Therese D. Pigott. 2012. “A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Bullying Prevention Programs' Effects on Bystander Intervention Behavior.” School Psychology Review 41 (1): 47–65. doi:10.1080/02796015.2012.12087375.

- Ringrose, Jessica, and Emma Renold. 2010. “Normative Cruelties and Gender Deviants: The Performative Effects of Bully Discourses for Girls and Boys in School.” British Educational Research Journal 36 (4): 573–596. doi:10.1080/01411920903018117.

- Rosenthal, Lisa, Valerie A. Earnshaw, Amy Carroll-Scott, Kathryn E. Henderson, Susan M. Peters, Catherine McCaslin, Jeannette R. Ickovics, et al. 2015. “Weight- and Race-Based Bullying: Health Associations among Urban Adolescents.” Journal of Health Psychology 20 (4): 401–412. doi:10.1177/1359105313502567.

- Salmivalli, Christina. 1999. “Participant Role Approach to School Bullying: Implications for Interventions.” Journal of Adolescence 22 (4): 453–459. doi:10.1006/jado.1999.0239.

- Salmivalli, Christina. 2010. “Bullying and the Peer Group: A Review.” Aggression and Violent Behavior 15 (2): 112–120. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2009.08.007.

- Salmivalli, Christina, Kirsti Lagerspetz, Kaj Björkqvist, Karin Österman, and Ari Kaukiainen. 1996. “Bullying as a Group Process: Participant Roles and Their Relations to Social Status within the Group.” Aggressive Behavior 22 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(1996)22:1 < 1::AID-AB1 > 3.0.CO;2-T.

- Salmivalli, Christina, Marinus Voeten, and Elisa Poskiparta. 2011. “Bystanders Matter: Associations between Reinforcing, Defending, and the Frequency of Bullying Behavior in Classrooms.” Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 40 (5): 668–676. doi:10.1080/15374416.2011.597090.

- Strindberg, Joakim, Paul Horton, and Robert Thornberg. 2019. “Coolness and Social Vulnerability: Swedish Pupils’ Reflections on Participant Roles in School Bullying.” Research Papers in Education Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/02671522.2019.1615114.

- Søndergaard, Dorte Marie. 2012. “Bullying and Social Exclusion Anxiety in Schools.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 33 (3): 355–372. doi:10.1080/01425692.2012.662824.

- Søndergaard, Dorte Marie, and Helle Rabøl Hansen. 2018. “Bullying, Social Exclusion Anxiety and Longing for Belonging.” Nordic Studies in Education 38 (4): 319–336. doi:10.18261/issn.1891-2018-04-03.

- Teräsahjo, Timo, and Christina Salmivalli. 2003. “She is Not Actually Bullied.’ the Discourse of Harassment in Student Groups.” Aggressive Behavior 29 (2): 134–154. doi:10.1002/ab.10045.

- Thornberg, Robert. 2010. “Schoolchildren's Social Representations on Bullying Causes.” Psychology in the Schools 47 (4): 311–327. doi:10.1002/pits.20472.

- Thornberg, Robert. 2015. “School Bullying as a Collective Action: Stigma Processes and Identity Struggling.” Children and Society 29 (4): 310–320. doi:10.1111/chso.12058.

- Thornberg, Robert. 2018. “School Bullying and Fitting into the Peer Landscape: A Grounded Theory Field Study.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 39 (1): 144–115. doi:10.1080/01425692.2017.1330680.

- Thornberg, Robert, Lena Landgren, and Erika Wiman. 2018. “It Depends’: A Qualitative Study on How Adolescent Students Explain Bystander Intervention and Non-Intervention in Bullying Situations.” School Psychology International 39 (4): 400–415. doi:10.1177/0143034318779225.

- Thornberg, Robert, Linda Wänström, Jun Sung Hong, and Dorothy L. Espelage. 2017. “Classroom Relationship Qualities and Social-Cognitive Correlates of Defending and Passive Bystanding in School Bullying in Sweden: A Multilevel Analysis.” Journal of School Psychology 63: 49–62. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2017.03.002.

- Walton, Gerald. 2011. “Spinning Our Wheels: Reconceptualizing Bullying beyond Behaviour-Focused Approaches.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 32 (1): 131–144. doi:10.1080/01596306.2011.537079.

- Walton, Gerald. 2015. “Bullying and the Philosophy of Shooting Freaks.” Confero 3 (2): 17–35. doi:10.3384/confer.2001-4562.150625.

- Wilks, Tom. 2004. “The Use of Vignettes in Qualitative Research into Social Work Values.” Qualitative Social Work 3 (1): 78–87. doi:10.1177/1473325004041133.

- Willis, Paul. 1977. Learning to Labour: How Working Class Kids Get Working Class Jobs. Farnborough: Saxon House.

- Wójcik, Małgorzata. 2018. “The Parallel Culture of Bullying in Polish Secondary Schools: A Grounded Theory Study.” Journal of Adolescence 69: 72–79. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.09.005.