Abstract

The relationship between students’ entry to higher education and the history or status of the secondary school which they attended is examined using school leavers’ surveys in Scotland stretching from the early 1950s to the late 1990s. The surveys are unique in the length of this period, their details of the higher-education institutions and schools which students attended, and their information on school attainment and on socio-economic status and sex. Universities, colleges and schools were classified in terms of their history in order to understand the role of educational institutions during three periods of reform – the ending of selection to secondary school between the mid-1960s and the late-1970s, and the two waves of expansion of higher education, in the 1960s and in the 1990s. The conclusion is that the distinctive characteristics of particular categories of institution – their institutional habitus – can modify inequality.

Context

The influence which secondary schools have on students’ entry to higher education has attracted research interest in recent years, although our knowledge of it is less extensive than the abundant evidence relating to students’ individual characteristics such as attainment, sex or socio-economic status (Taylor et al. Citation2018; Donnelly Citation2015). The question is whether schools are influential over and above their effects through attainment. A subsidiary question is whether schools modify the direct effects on entry to higher education of sex and socio-economic status, beyond these demographic factors’ effects on attainment. The main new evidence in the recent research has related to the role which is played by schools that are independent of public management, and also the role which school context plays, whether that is defined by socio-economic status or by attainment (e.g. Boliver Citation2013; Sutton Trust Citation2011). On the whole, independent schools and schools with high proportions of high-SES students tend to have higher rates of entry to higher education, even after controlling statistically for attainment and individual-level SES.

In these debates, there has been little attention to how the effects of schools might change over time. That absence is quite surprising. One of the aims of reforms to secondary schooling in many countries between the 1960s and the 1980s was to widen access to officially recognised attainment and thus to meaningful opportunities in post-school education (Gray, McPherson, and Raffe Citation1983). Because higher education, too, was structurally reformed in that same period, and later, it might be expected that there would be some interaction of these two policy processes. One reason to expect that is the concept of ‘institutional habitus’ (Donnelly Citation2015; Reay, David, and Ball Citation2001), which refers to the ways in which the ethos of a school might help its students to gain access to particular kinds of university. Reforms to secondary schools, such as the move in many countries to comprehensive schooling after the 1960s, and, in parallel, reforms to higher education, such as the end of the divide between older universities and technological colleges, might be expected to modify the ways in which institutional habitus operates.

The present paper considers these questions in relation to Scottish education in the second half of the twentieth century by using an internationally unique series of surveys of school leavers, stretching from the early 1950s to the end of the century. These surveys thus cover the periods of both the ending of all selection into public sector schools between the mid-1960s and the early 1980s, and also the ending of the distinction between universities and higher-education colleges in the early 1990s. We are able to study the interaction of two institutional reforms, and how that interaction, in turn, was modified by changing socio-economic status, changing differences between female and male students, and rising attainment in school-leaving examinations. The details of the institutional changes are described in the Methods section where we specify the institutional variables which are used in the statistical models, but the broad changes may be usefully sketched at the outset before we set these Scottish debates in the wider international discussion.

Scottish secondary schooling went through two periods of structural reform in the twentieth century. The first was between the beginning of the century and the 1920s, when the number of public-sector secondary schools was expanded from around 50 to around 250 (McPherson and Willms Citation1986; Paterson, Citation2011). The new schools were mostly located in districts where the population was predominatly skilled working-class or lower middle-class, in contrast to the older schools and to the independent schools, which generaly served the middle class. There were also a couple of dozen secondary schools that were independent of public management, some of which received some public grants until the 1970s. These three sectors all provided, in principle, five years of secondary education leading to the school-leaving certificate. By the 1930s around one third of each age cohort was on five-year courses. The consolidation of this reform in the decades from the 1930s to the 1950s left four main sectors of secondary school: the old schools which pre-dated the reforms, the independent schools, the new schools created in the first three decades of the century, and the short-course schools (usually referred to as junior secondary schools) that served the remaining approximately two thirds of pupils. Entry into short-course or long-course secondary education was primarily determined by tests of intelligence and attainment taken at age 11–12.

The second reform to secondary schooling was the ending in the 1960s and 1970s of the distinction between the short-course schools and the full secondaries, although nearly all the independent schools remained separate, educating about 5% of pupils. Successive reforms to curriculum, examinations, and systems of pastoral support for pupils gradually then sought to widen access to meaningful certification (Gray, McPherson, and Raffe Citation1983; McPherson and Willms Citation1987; Murphy et al. Citation2015).

Scottish higher education also went through two phases of reform. In the middle of the century, Scotland had four universities dating from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries (St Andrews, Glasgow, Aberdeen and Edinburgh), along with around a dozen colleges providing advanced technological courses, non-graduate training for teachers and nurses, and specialist courses in music or art. After the UK Robbins report of 1963, which proposed expansion of higher education, several of the colleges were upgraded or merged to become Strathclyde University in Glasgow and Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh, one college of St Andrews became the new Dundee University, and one wholly new university was created in Stirling. The other colleges continued to provide higher education. The second phase was in the early 1990s, when all these colleges became, or merged with, universities. At the same time, there was a growth in the provision of higher education courses at levels below degrees, mainly in the local technical colleges which had been established in the 1950s and later. Thus, by the mid-1990s, there were four sectors of higher education: the pre-twentieth-century old universities, the 1960s universities, the colleges which became universities in the early 1990s, and the sub-degree courses in the technical colleges. A few students attended universities outside Scotland (fewer than 1% of school leavers until the mid-1990s, rising slightly to 1.9% in 1998).

Our broad research aim is to understand how the school sectors and the higher-education sectors interacted with each other during 40-50 years of change when there were also several fundamental changes taking place in the relationship among socio-economic status, sex, attainment, and progression to higher education from school. The paper is in five further sections. Previous empirical research on the relationship between types of school and entry to higher education is summarised in the next section. Some of that research used the idea of institutional habitus, the relevant theories of which are set out explicitly in the third section, with particular attention to the question of change to habitus over time. Specific research questions are at the end of that section on theory. The data and research methods are described in the fourth section, and then the empirical results are in the section after that. The final section discusses these results in the light of the theories.

Previous research

In the past decade and half, there have been several significant contributions to research into the effects of secondary schools on entry to higher education. The earliest recent investigation of this topic was by Pustjens et al. (Citation2004), who examined the effects of secondary school on students’ choices of educational destination after school. These authors noted (282) the sparsity of research on this topic, as did Espenshade, Hale, and Chung (Citation2005, 270), Palardy (Citation2015, 346), and Donnelly (Citation2015, 1075). The general conclusion of the recent research has been that, although the main way in which schools have an effect on entry to higher education is through their effects on attainment in school-leaving examinations (Gorard et al. Citation2006), there is clear evidence also of direct school effects over and above that, and also over and above the effects of socio-economic status and sex. Pustjens et al. (Citation2004, 297), with data from Flanders, found large school effects on the chances of entering higher education. Taylor et al. (Citation2018, 591) found that, in Wales, the probability of going to university depended on the school that a student had attended. Anders and Micklewright (Citation2015) found, for England, that the probability of a school leavers’ proceeding to university was influenced by schools’ capacity to modify young people’s aspirations, a similar finding to that by Chowdry et al. (Citation2013) and Tymms (Citation1995).

A recurrent finding in this research has been that the socio-economic composition of the school affects the probability of an individual students’ going to university. Smyth and Hannan (Citation2007) found, in Ireland, a positive effect of attending a predominantly middle-class school, beyond the effect of individual circumstances. Shulruf, Hattie, and Tumen (Citation2008) reached a similar conclusion for New Zealand. Iannelli (Citation2004), comparing rates of transition to various post-school destinations in Scotland, Ireland and the Netherlands, found that variation among schools was greatest in the Netherlands, with its structurally divided school syatem, and least in Scotland, where all schools in the public sector are non-selective. Thus in Scotland individual characteristics (attainment, SES and sex) explained a larger proportion of the school variance than in the other two countries.

Donnelly (Citation2015) notes that the most common finding on how the character of a school might affect the probability of entering higher education has related to the difference between independent schools and public-sector schools. Boliver (Citation2013) found that independent schools in England increased their students’ chances of applying to, and being accepted by, high-status universities. There were similar findings by Mangan et al. (Citation2010) for England, Gayle, Berridge, and Davies (Citation2002) for England and Wales, Epenshade et al. (2005) for the USA, and Power and Whitty (Citation2008) for high-attaining students in England. The Sutton Trust (Citation2011) in the UK has used such research to campaign for reforms to the mechanisms of selection into higher education.

Some research has also found an interactive effect with school. Chowdry et al. (Citation2013, 451) noted that some schools were more effective than others in encouraging students from families of low socio-economic status. On the other hand, Epenshade et al. (2005, 288) noted (for the USA) that, after controlling for individual attainment and demographic characteristics, schools with high academic achievement had lower than expected rates of progress to higher education, especially for low-attaining students.

Some of this research has distinguished among different categories of higher education. Closest to the classification which is used in the present paper is that by Taylor et al. (Citation2018), who studied entry not only to degree courses at any university but also to shorter (usually two-year) courses or to degree courses in the highest-status universities. The distinction between degrees and two-year diplomas is analogous to that between four-year and two-year programmes in the USA, school effects on entry to which were investigated by Palardy (Citation2015). The conclusion of this body of work is that, on the whole, high-status schools tend to be associated with high-status universities or courses. Taylor et al. (Citation2018) found that school effects were particularly strong for entering elite universities. Power and Whitty (Citation2008) even found that students from independent schools whose attainment was too low to allow them to enter elite universities tended to avoid university altogether, whereas similarly qualified students from public-sector schools would go to lower-status universities.

Theory

The main body of theory which has been offered to explain school effects on entry to higher education relates to what has been called ‘institutional habitus’. The present paper is not a contribution to theory, but has the more modest aim of offering an empirical analysis in which theory might be valuable as a way of interpreting the empirical findings. Smyth and Hannan (Citation2007, 176) describe institutional habitus as ‘the impact of a social group on an individual’s behaviour as it is mediated through organisations such as schools’. Donnelly (Citation2015, 1076) links this more explicitly to the ideas of Bourdieu, defining institutional habitus as ‘a set of dispositions and behaviours that are the product of a school’s past experiences, staff and pupils’, a description that is analogous to Nash’s summary (Citation1999, 184) of Bourdieu’s idea of habitus as ‘a system of durable dispositions inculcated by objective structural conditions’. Though Bourdieu himself does not seem to have used the term, institutional habitus is central to his ideas of social reproduction, habitus in general being ‘that system of dispositions which acts as a mediation between structures and practice’ (Bourdieu Citation1973, 72), the means by which ‘structures … reproduce themselves’ through creating agents attuned to that reproduction. So the students become both the products of the reproduction and the agents of its further development. Part of that process is the affinity between secondary schools and particular tertiary institutions. In Bourdieu’s work on France, that was embodied in the connection between the highest status forms of the baccalauréat and the grandes écoles (Bourdieu Citation1984, 133–168). Reay, David, and Ball (Citation2005, 52) applied these ideas to understanding the links between particular kinds of secondary school in England and sectors of the university system: ‘a geography of taken-for-granteds, possibilities, improbabilities, relationships and identities. Some routes are much more obvious and straightforward from one institutional vantage point than another’. Forbes and Lingard (Citation2013) invoke institutional habitus to explain the effects of an independent girls’ school on its students’ opportunities. Although Atkinson (Citation2011) demurs at using ‘habitus’ to describe an institution, on the grounds that the term ought to be corporeal, it has thus served at least metaphorical purposes in these writers’ development of Bourdieu’s ideas.

Previous empirical development of the idea of institutional habitus has emphasised what Reay, David, and Ball (Citation2001, 1.2–1.3) call the dynamic aspect of institutional habitus: ‘institutional habituses, no less than individual habituses, have a history and have been established over time’. Nevertheless, there has been little empirical attention to change of institutional habitus except as a slowly and autonomously evolving characteristic. Reay (Citation1998) notes that ‘institutional habituses are capable of change but through dint of their collective nature are less fluid than individual habitus’. Other writers, though acknowledging the possibility of change, tend to treat institutional habitus as a given. Ingram (Citation2009, 432) suggests that ‘despite its fluidity any changes in institutional habitus are likely to be a result of a slow evolution’. Palardy (Citation2015, 332) describes change in habitus as ‘evolv[ing] over time through interactions between parents, students, and staff’. Smyth and Banks (Citation2012, 265) refer to ‘change as schools and catchment areas mutually shape and reshape each other’, a process that is inevitably slow.

The questions which we investigate in this paper are intrinsically about potential change in habitus – the ending of selection into different kinds of secondary school in the public sector, and the various reforms to higher-education institutions. Therefore, although we invoke the concept of institutional habitus as a way of explaining empirical patters, and although these previous writers’ use of the term is highly illuminating, we have to turn to distinct bodies of ideas for suggestions about how that concept might be relevant to institutional change. As Bourdieu’s writing implied, the idea of institutional habitus is in some respects a way of representing what might be called the relationship between structure and agency (Archer Citation1979). Previous studies of the historical legacies of educational institutions in Scotland have drawn on these older ways of thinking about their effects. The history of Scottish schools has been studied for its lasting effect on school attainment (e.g. McPherson and Willms Citation1986; Paterson, Citation2020), by invoking ideas about institutions’ persisting identity. Ocasio, Mauskapf, and Steele (Citation2016, 676) noted that all persisting organisations develop ‘historically situated webs of meaning and significance’. These might be particularly strong in schools and universities, because attention to cultural meanings is part of these institution’s basic purpose. Much of the previous study of institutional legacies in Scotland has paid attention to the ways in which schools contribute to defining the social-class identity of communities (McPherson and Willms Citation1986). All these historical studies have had change as their central focus. J.W. Meyer and Rowan (Citation1977, 340 and 355) describe how ‘institutional rules function as myths’ but ‘may conflict with one another’, provoking institutional change. H.-D. Meyer (Citation2006, 52) goes further in noting that institutional myths might actually embody ‘beliefs in the change process and the power struggles that always surround institutions’. Analysing the history of the common school in the USA in the late-nineteenth century, he described how the advent of massive waves of immigration from central Europe elicited new political coalitions which could emphasise the egalitarian potential of the institutional tradition in order to shape it as the basis of a new system of schooling for the twentieth century. This US experience is an instance of the ‘critical events’ which Clemente et al. (Citation2017, 22–24) suggest are a common means by which ‘slow-changing systems’ adapt. Events, among which they include political reforms, ‘push organizations to react, … lead[ing] to decisions to support the current order of things or to challenge it’. Nikolai (Citation2019, 377–8), while recognising that ‘accumulated commitments and investments in the selected path make it difficult to effect any profound change’, comments that an exogenous change in ‘societal values’ might ‘delegitimise established institutional forms and practices’. Ocasio, Mauskapf, and Steele (Citation2016, 690) point out that this can happen when the gradual ‘accumulation of historical events’ leads to general ‘societal transformation’. The influence of institutions and the wider society might thus be mutual.

There are two specific reasons to to ask whether institutional habitus can change as well as the reasons which arise from the theory itself. One is change in the context. When the nature of social class has changed as profoundly as it did between the early 1950s and the late 1990s, we might expect some change in the connection between class and institutions; and if there is no such change, the stability would itself require to be explained. The other reason is the extensive policy changes in that same half century. Because several of these policies were designed to modify the relationship between social class and educational opportunity, the question then arises as to whether institutional habitus has anything to contribute to understanding the changing links among institutions, social class and an expanding system of higher education. Few of the empirical investigations of the effects of schools on entry to higher education that were summarised in the previous section had data that allow any study of change over time. Most studies refer to at most a few consecutive years. Exceptions are Boliver (Citation2013), who examined the decade from 1996 to 2006, and Espenshade, Hale, and Chung (Citation2005), who dealt with 1983–1997 but did not analyse change over time. Our data, in contrast, cover the whole of the second half of the twentieth century, with a particular focus on the period after the early 1960s.

From the theory and the previous research, we have four specific research questions:

Was there any statistical association between school sector as defined by school history, and university sector as defined by university history? Such an association would suggest some affinity of institutional habitus.

Was any such association in turn linked to students’ social class? Such a link would suggest that any affinity of institutional habitus was related to social class.

Was any such association with social class explained statistically by students’ attainment? In other words, was attainment the means by which class stratification was expressed?

How did any of these associations change over time as both schooling and higher education were reformed? Any such change would suggest that the social significance of institutional habitus changed.

Data and methods

Details of the sources of data and of the methods of statistical analysis are in the supplemental online material, and explained also by Paterson (2020). In brief, the analysis uses data from 14 surveys of school leavers, which will be referred to by the dates at which their members turned 16: 1952, 1960–2, 1968–70, 1970–2, 1974–6, 1976–8, 1978–80, 1980–2, 1984, 1986, 1988, 1990, 1996, and 1998 (Croxford, Iannelli, and Shapira Citation2007; McPherson and Neave Citation1976; Powell Citation1973). We use these surveys as two kinds of series. For models of the full range of student attainment, we can use 1952 and 1974–6 to 1998. The corresponding results are in , and the associated graphs. The second series is restricted to people who passed at least one senior-secondary courses, and includes the surveys from 1960-2 to 1998 (omitting 1952 because there were too few such students for reliable estimates): and , and associated graphs.

Table 1. Entry to sectors of higher education, 1952–98.

Table 2. Entry to sectors of higher education, among people who had passed at least 1 Higher Grade at school, 1962–98.

Table 3. Higher-education entry rates, by school sector and sex, 1960–2 to 1996–8.

We model students’ entry to higher education within about a year of leaving school, distinguishing among four categories of higher education.

the four old universities;

the four universities created in the 1960s (or their institutional predecessors in 1960–2), along with pre-1990s universities outside Scotland;

degree courses in institutions other than the universities in (1) and (2);

non-degree courses and professional courses, which are mainly courses leading to a Higher National Certificate or Diploma.

The corresponding distributions for both series of surveys are shown in and .

In the tables, statistical models numbered (1) compare, across the whole sample, entering and not entering the old universities. Models (2) are restricted to people who did not enter the old universities, and compare entering and not entering these other pre-1990s universities. Models (3) analogously restrict to people who did not enter any university in categories (1) or (2), and Models (4) are restricted to people who did not enter any degree course. This approach thus recognises the ordered hierarchy of institutions.

The explanatory variable on which we concentrate is a classification of sample members’ final school into the four historically defined sectors. These are, with the average proportion of sample members in them across the full-coverage surveys from 1952:

old full secondaries (pre-1900) (12%);

independent or grant-aided schools (4%);

new full secondaries (founded 1900–1940s) (35%);

junior secondaries (50%).

The other explanatory variables are attainment in the senior years of school, sex, and socio-economic status. Attainment is measured as awards in the Higher Grade examinations (usually taken in the final two years of secondary school), standardised to have mean 0 and standard deviation 1 in each survey. For the models confined to people with at least one Higher Grade award, we can measure both the number and the quality of attainment as

(number of A-C awards) + 0.5x (number of A awards)

It too is standardised in each survey.

A variable recording sex is available in all surveys; in each survey, around half the sample was female. Social class is the Registrar General occupational class of the father, grouped for the analysis into I,II; III; IV, V, other. Parental education was recorded in all but the 1960–2 survey as the age at which each parent left full-time education (15 or younger; 16; 17 or older, or unknown). The 1960–2 survey did not have any information on parental education, but, in order to be able to use this variable with the whole series, we imputed the modal value of parental education for each of the six categories of father’s class by the technique explained in the supplemental material.

The statistical modelling was done in the R statistical environment, using the function ‘svyglm’ in the ‘survey’ package. This allowed weights and the clustering into schools to be taken into account. We show detailed results by means of predicted proportions entering the sectors of higher education. Summaries of the models are in the supplementary material.

Empirical results

shows the expansion of school-leaver participation in the four sectors of higher education in the second half of the twentieth century. The overall growth, shown in the ‘all sectors’ column, happened in two periods – a doubling to a quarter by the early 1980s, and then an increase to four out of ten by the end of the century. That expansion masked broad stability until the late-1980s in both the oldest sector and, after their initial growth, the other pre-1990s universities. Expansion until the late-1980s was more striking in the degree courses outside the then universities, and in non-degree courses in local colleges. As a result, the share of students taken by the two older sectors fell from around one half in the 1970s to just over a third in the early 1980s, recovering back to just under one half in the late-1990s.

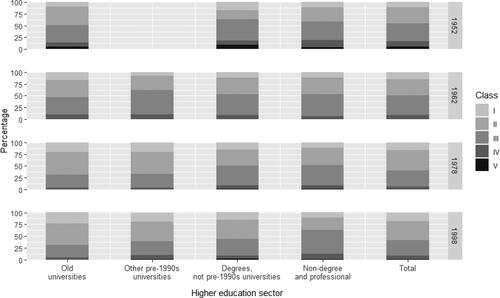

thus sets the context for investigating the relationship between sectors of schools and sectors of higher education, and whether any links are associated with social status or sex. illustrates the social class distribution of the student intake to the four sectors of higher education, and to higher education as a whole, covering the period from 1952 to 1998. Until the 1960s, the old universities originally had intakes that were representative of all students, but they took an increasing share of high-status students over the following three decades. The other pre-1990s universities, by contrast, were more inclusive in the 1960s and remained in line with overall intake, as did the sector of degree courses in the institutions that were higher-education colleges until the 1990s and new universities thereafter. The low-status students were thus increasingly concentrated in the mainly non-degree programmes of the further-education colleges.

Figure 1. Social class distribution of school-leaver entrants to sectors of higher education, 1952, 1962, 1978 and 1998.

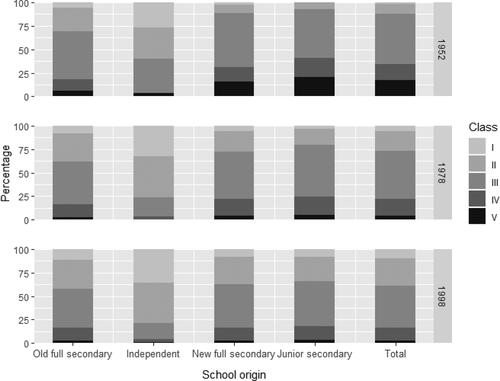

By contrast to this segmentation, the shift to comprehensive secondary schooling in the public sector forced the historically defined school sectors in the opposite direction, towards greater homogeneity with respect to social class. shows the social-class distribution of the four school sectors. In 1952, the old secondaries had higher proportions from classes I and II than the newer secondaries or the junior secondaries. These three sectors then steadily converged. The proportion of classes I and II in the independent schools remained very high.

Figure 2. Social class distribution of school leavers, by origin and status of school, 1952, 1978 and 1998.

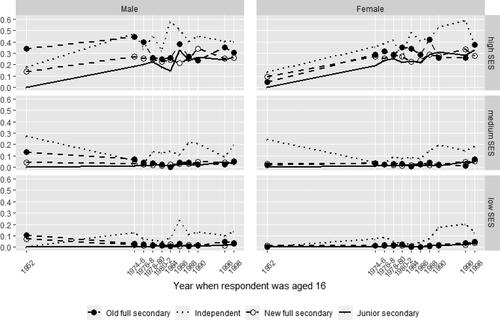

Our question is whether there was any institutional association of school sector with higher-education sector, whether that association was linked to social class, whether that might be explained by school attainment, and whether any of these associations changed over time. As a preliminary analysis of the statistical effects of school sector and socio-economic status, (Supplementary Material) summarises models of entering each of the four sectors of higher education (conditional on not entering the sectors above it in the hiererachy), without controlling for school attainment. For each sector, the largest statistical effect is time. For all but sub-degree courses, the next largest is the interactive effect of school sector and time. For sub-degrees, the second-largest place is shared by that effect and the further interactive effect of time, school sector and social class. For the other three higher-education sectors, that three-way effect is the third or fourth highest. So the changing relationship of school sector to each sector of higher education, and the social class variation in these trajectories, are the most important explanation of change of participation over time (before we take account of school attainment).

The nature of these changes is illustrated in , which shows changing rates of entry to the old universities, by socio-economic status, school sector, and sex. From the mid-1980s, the independent schools (dotted line) were ahead, but that had not previously been consistently the case, especially for high-SES students, the dominant group in these schools. After the ending of selection for entry to the education-authority sectors in the 1970s, the differences among these three categories of schools shrank so far that their lines are not clearly separated from each other in the graphs. This preliminary analysis suggests that there is potential evidence for a link of habitus between entry to the highest-status universities and attendance at independent schools or at the oldest schools in the public sector. But, if so, there is change over time, in opposite directions. The association with independent schools grew over time, but that with old public-sector schools declined.

Figure 3. Proportion entering old universities, by socio-eonomic status, sex and school origin and status, 1952–98.

Source: Predicted values from model 1 in .

Next we add school attainment to the models. As explained in the Methods section, we now restrict attention to people with at least one Higher Grade award, enabling us to include the surveys of 1960–2, 1968–70 and 1970–2, but requiring us to drop the 1952 survey. The rates of entry by these students to the four sectors of higher education are shown in . We deal separately with: (1) independent schools compared to education-authority schools, and (2) comparison among the categories of the latter.

Table A2 (supplementary material) summarises the models for the first set of these comparisons. For entry to each sector of higher education (again conditional on not entering the sectors above it in the hiererachy), the main statistical effect is still time, but attainment and the changing effect of attainment are the next strongest for entry to the old and to the other pre-1990s universities. For the other two outcomes, the effect of attainment and how it changes are similar to the changing effect of class and how it changes. The effect of school sector and how it changes are smaller than the effect of attainment for all but entry to sub-degree courses, but in no case has the addition of attainment removed the effect of school sector or its interactive effect with class.

The sample sizes for the independent schools are relatively small in the later surveys, especially for social classes other than I&II. For example, in the five surveys 1986–98 taken together, a total of only 126 people from class III were in these schools, and only 100 from class ‘IV,V,other’. Therefore, for illustrating the difference between independent and education-authority schools, we confine attention to class I&II, and also group the years into four categories: 1962–72, in which period most students would have entered secondary school in the pre-comprehensive system; 1976–84, which is the period of ending selection; 1986–90, the period of extending the mid-secondary curriculum to all students; and 1996–98, which reflects the stable reformed system. shows, for each of these periods, the proportion of students in class I&II who entered each of the sectors of higher education (conditional on not entering the sectors above it in the hiererachy), controlling for attainment and sex.

For the old universities, the entry rate from the independent schools remains consistently a few percentages points higher than from the education-authority schools, widening in the 1990s for women. For the other pre-1990s universities and the institutions that became universities in the 1990s expansion, there is a widening in favour of the independent schools after the mid-1980s for both men and women. In contrast, entry to non-degree courses is nearly always more common from the education-authority schools than from the independent schools, the latter route falling away almost completely in the 1990s.

We can sum this up by saying that the independent-schools advantage has not been explained wholly by attainment. The long-established advantage in entry to the old universities was supplemented by a new advantage for independent schools in relation to the other pre-1990s universities and to those that were upgraded in the 1990s. So this is evidence of the maintenance of institutional affinity between independent schools and old universities, and the possible creation of a new affinity with other sectors.

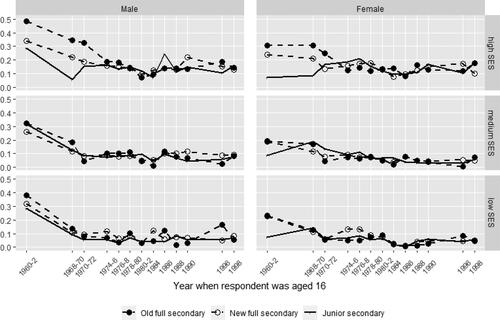

The remaining analysis is confined to education-authority schools. (supplementary material) summarises the models, which broadly show the same kinds of pattern of statistical effects as . The major effects after year are attainment or the changing effect of that. Class, sex and school sector have effects, all of which change over time. These effects are illustrated in for entry to the old universities. Until the full implementation of comprehensive schooling, the old schools (dashed line with solid circles) had a distinct advantage among high-SES students for entry to the old universities. In the surveys from 1962–72, the rate of entry by high-SES males was 0.22 higher in the old schools than in the former junior secondaries, and 0.13 higher than in the newer secondaries (s.e. respectively 0.06 and 0.03; p < 0.001). For females, the differences in rates were 0.18 (s.e. 0.04; p < 0.001) and 0.091 (0.03; p = 0.003). The differences between the new full secondaries (dashed line with open circles) and the junior secondaries (solid line) were also quite clear: for males, 0.084 (s.e. 0.05; p = 0.11); for females, 0.09 (s.e. 0.03; p = 0.003). But shows that all these differences disappeared in the 1980s. From the mid-1970s, there never were any differences by school origin for entry to old universities by medium-SES or low-SES students. For no group was there any old-school advantage for entry to the other sectors of higher education (not shown). All these patterns were similar for attainment at half a standard deviation above or below the mean (not shown).

Figure 4. Proportion entering old universities at mean* attainment, by socio-eonomic status, sex and school origin, 1962–98 (public sector schools only).

*Mean attainment among students who had at least one Higher Grade award.

Source: Predicted values from Model 1 in .

So there was probably an affinity betweeen old schools and old universities for high-SES students before selection for secondary school was ended, and before higher education started to expand. There was a weaker but still distinct affinity between these universities and the secondaries that had been created early in the twentieth century. The affinity was not due to school attainment (or sex or SES). It was brought to an end by comprehensivisation, and showed no sign of re-emerging when higher education expanded in the 1990s. There was no such affinity evident for newer segments of higher education. This contrasts with independent schools, where there was evidence of persisting affinity with the oldest parts higher education, and the emergence of a new affinity with the newer universities.

Discussion

The surveys which have been used in this analysis cover half a century, two phases of higher-education expansion, and radical changes in the structure of secondary schools. They allow distinctions to be drawn among different sectors of higher education, and enable participation to be analysed in terms of school attainment, sex and socio-economic status. The surveys also provide details of the secondary schools which students attended, which could be classified by their history stretching back to the early twentieth century. So the analysis could also investigate the residue of previous reforms in understanding how the reforms of the second half of the twentieth century had an impact on students’ opportunities. No other data source, in any country, allows attention to these kinds of questions over such a long period of time. The main limitation of the analysis is that the data cover only school leavers. No evidence was available for other routes into higher education, or for progress within higher-education courses.

The general aim of the analysis was to investigate how two processes of institutional reform interacted, and how any interaction related to social class. The one process was the ending of selection for secondary school between the mid-1960s and the late-1970s. The other was the expansion of higher education, first between the early 1960s and the late-1970s, and later during the 1990s. These processes have often been studied separately, both for Scotland and in many other places. Being able to treat them together is another value of the data sources.

The conclusion provided two sets of answers to the four research questions outlined earlier. The concept of institutional habitus, and its changing importance over time, provides coherence to these conclusions. One set of answers related to change which happened autonomously from any deliberate policy intent. When the public-sector schools were ending selection between the 1960s and the early 1980s, the independent schools, serving predominantly students of high socio-economic status, maintained their association with the oldest parts of higher education. This constant association is then a typical instance of the consequences of institutional habitus that have been investigated by previous researchers (as summarised above: e.g. Reay, David, and Ball (Citation2005), Smyth and Hannan (Citation2007) and Donnelly (Citation2015)). During the second phase of expansion of higher education, in the 1990s, new affinities emerged between these schools and other pre-1990s universities and with colleges that became universities in the 1990s. The independent schools’ advantages were not explained by attainment, suggesting that, during the period when their apparent affinity with university entrance was strengthening, there was emerging the kind of institutional habitus which other writers have invoked as an explanation of independent schools’ role. But the key point is that any such habitus emerged, and was not merely inherited: it emerged to link these schools with university sectors to which they had not previously shown any affinity. Change of this kind has not usually been traced in the literature on institutional habitus, but has been a theme (under different names) in the historical work that was also summarised earlier (e.g. Clemente et al. Citation2017; Ocasio, Mauskapf, and Steele Citation2016). To understand better how it emerged would require detailed, perhaps ethnographic, research on individual schools during the five decades which our surveys have covered, but our analysis has suggested that there is something of theoretical interest worth investigating: an autonomously changing role for institutional habitus.

Understanding emerging habitus would also have to take into account the precisely opposite trajectory of the older schools in the public sector, providing the second set of answers to the four research questions. The history of these schools was associated with entry to high-status higher education in subtly differentiated ways. It was not only that, during the transition to non-selective secondary schooling, students from the former senior-secondary schools remained more likely to attend the old universities than students from the former junior secondary schools who had similar attainment and similar socio-economic status. Even within the category of senior-secondary school, the oldest schools at that time had an advantage over the schools that had been founded early in the twentieth century. These differences suggest, as with the independent schools, some aspect of institutional habitus which associated the older schools with the older universities. But then, quite unlike the independent schools, this distinction vanished as the comprehensive system settled down, and as the social-class distribution in the older schools came to resemble the social-class distribution of the system as a whole. As with the independent schools, explaining these changes in the effects of the older schools would require detailed archival work on their ethos and characteristics during the ending of selection (for example, as examined by Murphy et al. (Citation2015) or by Gray, McPherson, and Raffe (Citation1983)). But what can plausibly be said is that the association between school sector and university sector did change, and that the change could be represented as a declining role for social class as a dimension of stratification between historically defined school sectors. Perhaps of greatest interest for the theory of institutional habitus, these changes would not have happened without the deliberate policy intervention represented by the development of comprehensive secondary schooling. This finding is, again, an addition to the empirical work on institutional habitus, and is consistent with historical research on what Clemente et al. (2017, 22) called critical events: for example, the education-policy responses to German re-unification in the 1990s (Nikolai Citation2019), or the reform to the US common schools in the early decades of the twentieth century (H.-D. Meyer Citation2006). Our suggestion, then, is that reforms to the institutional structures of secondary schooling and of higher education constituted critical events in this sense,

In short, institutional habitus can indeed change, and not only slowly: in historical perspective, the period from the 1970s to the 1990s is relatively short. The change can be autonomous of policy, or fostered by policy. It can make inequality greater, as in the strengthening links of independent schools with university entry, or it can remove old social distinctions, as in the case of the old schools in the public sector. Although our statistical analysis has described changes rather than explained them, it has nevertheless suggested that Reay, David, and Ball (Citation2001)’s description of institutional habitus as ‘dynamic’ is worth taking very seriously, and investigating further.

Ethical statement

The paper is entirely based on secondary data. The participants in the surveys gave their informed consent, as detailed in the original reports of the surveys noted in the Data and Methods section. The analysis on which the paper is based was given ethical clearance by the research ethics committee of the School of Social and Political Science, Edinburgh University, on 27 March 2017.

This work was funded by Leverhulme Trust.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (35.6 KB)Acknowledgements

The research was funded by a Leverhulme Major Research Fellowship (grant number MRF-2017-002). I am grateful to Dr Linda Croxford, of the Centre for Educational Sociology, Edinburgh University, for data for the surveys 1960-2 to 1998, to Professor Ian J. Deary, director of the Lothian Birth Cohorts, Edinburgh University, for data from the Scottish Mental Survey 1947, to the MRC Unit for Lifelong Health and Ageing, University College London, and the principal investigators of the MRC National Survey of Health and Development (doi: 10.5522/NSHD/Q101), and to the UK Data Archive for data from the Education and Youth Transitions series.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Anders, J., and J. Micklewright. 2015. “Teenagers’ Expectations of Applying to University: how Do They Change?” Education Sciences 5 (4): 281–305. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci5040281.

- Archer, M. S. 1979. The Social Origins of Educational Systems. London: Sage.

- Atkinson, W. 2011. “From Sociological Fictions to Social Fictions: some Bourdieusian Reflections on the Concepts of ‘Institutional Habitus’ and ‘Family Habitus.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 32 (3): 331–347. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2011.559337.

- Boliver, V. 2013. “How Fair Is Access to More Prestigious UK Universities?” The British Journal of Sociology 64 (2): 344–364. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12021.

- Bourdieu, P. 1973. “Cultural Reproduction and Social Reproduction.” In Knowledge, Education and Cultural Change, edited by R. Brown, 71–112. London: Tavistock.

- Bourdieu, P. 1984. Distinction, translated by R. Nice. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Chowdry, H., C. Crawford, L. Dearden, A. Goodman, and A. Vignoles. 2013. “Widening Participation in Higher Education: analysis Using Linked Administrative Data.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 176 (2): 431–457. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-985X.2012.01043.x.

- Clemente, M., R. Durand, and T. Roulet. 2017. “The Recursive Nature of Institutional Change: An Annales School Perspective.” Journal of Management Inquiry 26 (1): 17–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492616656408.

- Croxford, L., C. Iannelli, and M. Shapira. 2007. Documentation of the Youth Cohort Time-Series Datasets. UK Data Archive, Study Number 5765. doi: https://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-5765-1

- Donnelly, M. 2015. “A New Approach to Researching School Effects on Higher Education Participation.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 36 (7): 1073–1090. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2014.886942.

- Epenshade, T. J., L. E. Hale, and C. Y. Chung. 2005. “The Frog Pond Revisited: High School Academic Context, Class Rank, and Elite College Admission.” Sociology of Education 78 (4): 269–293. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/003804070507800401.

- Forbes, J., and B. Lingard. 2013. “Elite School Capitals and Girls’ Schooling: understanding the (Re) Production of Privilege through a Habitus of ‘Assuredness.” In Privilege, Agency and Affect, edited by C. Maxwell and P. Aggleton, 50–68. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gayle, V., D. Berridge, and R. Davies. 2002. “Young People’s Entry into Higher Education: Quantifying Influential Factors.” Oxford Review of Education 28 (1): 5–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980120113607.

- Gorard, S., E. Smith, H. May, L. Thomas, N. Adnett, and K. Slack. 2006. Review of Widening Participation Research: Addressing the Barriers to Participation in Higher Education: A Report to HEFCE. York: Department of Educational Studies.

- Gray, J., A. McPherson, and D. Raffe. 1983. Reconstructions of Secondary Education: Theory, Myth and Practice since the War. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Iannelli, C. 2004. “School Variation in Youth Transitions in Ireland, Scotland and The Netherlands.” Comparative Education 40 (3): 401–425.

- Ingram, N. 2009. “Working‐Class Boys, Educational Success and the Misrecognition of Working‐Class Culture.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 30 (4): 421–434. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690902954604.

- Mangan, J., A. Hughes, P. Davie, and K. Slack. 2010. “Fair Access, Achievement and Geography: Explaining the Association between Social Class and Students’ Choice of University.” Studies in Higher Education 35 (3): 335–350. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903131610.

- McPherson, A., and G. Neave. 1976. The Scottish Sixth. Slough: NFER.

- McPherson, A., and J. D. Willms. 1986. “Certification, Class Conflict, Religion, and Community: A Socio-Historical Explanation of the Effectiveness of Contemporary Schools.” In Research in Sociology of Education and Socialization, edited by A. C. Kerckhoff, Vol. 6, 227–302. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- McPherson, A., and J. D. Willms. 1987. “Equalisation and Improvement: Some Effects of Comprehensive Reorganisation in Scotland.” Sociology 21 (4): 509–539. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038587021004003.

- Meyer, H.-D. 2006. “The Rise and Decline of the Common School as an Institution: taking ‘Myth and Ceremony’ Seriously.” In The New Institutionalism in Education, edited by H.-D. Meyer and B. Rowan, 51–66. New York: State University Press.

- Meyer, J. W., and B. Rowan. 1977. “Institutionalized Organizations: formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony.” American Journal of Sociology 83 (2): 340–363. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/226550.

- Murphy, D., L. Croxford, V. Howieson, and D. Raffe (eds.). 2015. Everyone’s Future: Lessons from Fifty Years of Scottish Comprehensive Schooling. London: IoE Press.

- Nash, R. 1999. “Bourdieu, ‘Habitus’, and Educational Research: Is It All Worth the Candle?” British Journal of Sociology of Education 20 (2): 175–187. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01425699995399.

- Nikolai, R. 2019. “After German Reunification: The Implementation of a Two-Tier School Model in Berlin and Saxony.” History of Education 48 (3): 374–394. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0046760X.2018.1545932.

- Ocasio, W., M. Mauskapf, and C. W. Steele. 2016. “History, Society, and Institutions: The Role of Collective Memory in the Emergence and Evolution of Societal Logics.” Academy of Management Review 41 (4): 676–699. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2014.0183.

- Palardy, G. J. 2015. “High School Socioeconomic Composition and College Choice: Multilevel Mediation via Organizational Habitus, School Practices, Peer and Staff Attitudes.” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 26 (3): 329–353. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2014.965182.

- Paterson, L. 2020. “Schools, Policy and Social Change: Scottish Secondary Education in the Second Half of the Twentieth Century.” Research Papers in Education. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2021.1931951

- Paterson, L. 2011. “The Reinvention of Scottish Liberal Education: Secondary Schooling, 1900–39.” The Scottish Historical Review 90 (1): 96–130. doi:https://doi.org/10.3366/shr.2011.0005.

- Powell, J. L. 1973. Selection for University in Scotland. London: University of London Press.

- Power, S. A., and G. Whitty. 2008. “Graduating and Gradations within the Middle Class: The Legacy of an Elite Higher Education.” Working Paper. 118 Cardiff School of Social Sciences.

- Pustjens, H., E. Van de Gaer, J. Van Damme, and P. Onghena. 2004. “Effect of Secondary Schools on Academic Choices and on Success in Higher Education.” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 15 (3–4): 281–311. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09243450512331383222.

- Reay, D. 1998. “Always Knowing’ and ‘Never Being Sure’: Familial and Institutional Habituses and Higher Education Choice.” Journal of Education Policy 13 (4): 519–529. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093980130405.

- Reay, D., M. David, and S. Ball. 2001. “Making a Difference?: Institutional Habituses and Higher Education Choice.” Sociological Research Online 5 (4): 14–25. http://www.socresonline.org.uk/5/4/reay.html. doi:https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.548.

- Reay, D., M. David, and S. Ball. 2005. Degrees of Choice. London: Trentham.

- Scottish Education Department. 1971. Education in Scotland in 1970. Edinburgh: SED.

- Scottish Education Department. 1973. Education in Scotland in 1972. Edinburgh: SED.

- Shulruf, B., J. Hattie, and S. Tumen. 2008. “Individual and School Factors Affecting Students’ Participation and Success in Higher Education.” Higher Education 56 (5): 613–632. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-008-9114-8.

- Smyth, E., and J. Banks. 2012. “There Was Never Really Any Question of Anything Else’: Young People’s Agency, Institutional Habitus and the Transition to Higher Education.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 33 (2): 263–281. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2012.632867.

- Smyth, E., and C. Hannan. 2007. “School Processes and the Transition to Higher Education.” Oxford Review of Education 33 (2): 175–194. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980701259964.

- Sutton Trust. 2011. Degrees of Success: University Chances by Individual School. London: Sutton Trust.

- Taylor, C., C. Wright, R. Davies, G. Rees, C. Evans, and S. Drinkwater. 2018. “The Effect of Schools on School Leavers’ University Participation.” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 29 (4): 590–613. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2018.1484776.

- Tymms, P. 1995. “The Long‐Term Impact of Schooling.” Evaluation & Research in Education 9 (2): 99–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09500799509533377.