Abstract

Private schools have long played a crucial role in male elite formation but their importance to women’s trajectories is less clear. In this paper, we explore the relationship between girls’ private schools and elite recruitment in Britain over the past 120 years – drawing on the historical database of Who’s Who, a unique catalogue of the elite. We find that alumni of elite girls schools have been around 20 times more likely than other women to reach elite positions. They are also more likely to follow particular channels of elite recruitment, via the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, private members clubs and elite spouses. Yet such schools have also consistently been less propulsive than their male-only counterparts. We argue this is rooted in the ambivalent aims of girls elite education, where there has been a longstanding tension between promoting academic achievement and upholding traditional processes of gendered social reproduction.

Introduction

Sociological research has long demonstrated that those who reach elite positions often rely on a distinct set of educational channels (Khan Citation2012; Mills Citation1956). Yet this literature – often called ‘elite recruitment studies’ – has largely reproduced gendered assumptions about the propulsive power and sociological significance of elite education. In particular, it has focused almost exclusively on how certain institutions – such as private schools, elite universities and private members clubs – act, often in concert, to propel men into elite destinations (Domhoff Citation1967; Kelsall Citation1966; Mills Citation1956; Stanworth and Giddens Citation1974; Useem Citation1986). The institutional starting point of such trajectories, often referred to colloquially as an ‘old boys’ network’, are male-only elite schools (Reeves et al. Citation2017). Indeed, historically, elites in a range of national contexts have all had strong and enduring ties to a small set of such male-only private secondary schools (Bourdieu Citation1996; Courtois Citation2017; Khan Citation2011; Maxwell and Maxwell Citation1995).

Yet while male elite schools may remain powerful training grounds for future leaders, we argue here that the scholarly (and wider public) preoccupation with this old boys’ network has acted to inadvertently stymie inquiry into other equally important channels of elite recruitment. In particular, we ask, what about the ‘old girl’? Does a similar ‘old girls’ network’ exist for women? Certainly, in many national contexts, there has long existed a range of expensive, prestigious and well-known fee-paying schools for young women (as well as women-only university colleges and women’s private members clubs) (Avery Citation1991; Forbes and Maxwell Citation2018). Indeed a rich body of research has variously demonstrated the importance of private girls’ schools, more generally, in cultivating specific femininities (Allan and Charles Citation2014; Kenway, Langmead, and Epstein Citation2015), fostering dispositions of ‘assuredness’ (Forbes and Lingard Citation2013) or ‘surety’ (Maxwell and Aggleton Citation2016), or as institutions where working-class and ethnic minority students are frequently othered and stigmatised (Horvat and Antonio Citation1999).

Less clear from this literature, however, is the propulsive power of girls’ private schools; how successful are they are delivering their alumni into elite positions, how does this compare to elite boys’ schools, how has their power changed over time, and what is their relationship to other channels of elite recruitment? In this paper we address these questions via a unique data set − 120 years of biographical data contained within Who’s Who, an unrivalled catalogue of the British elite. Specifically, we use Who’s Who to explore the degree to which elite girls’ schools have remained pivotal to elite recruitment over time and how this compares to the power of boys’ schools in the same period. We then go a step further to examine the institutional channels through which these schools propel their alumni, documenting the independent and cumulative advantages that flow from attending Britain’s elite girls’ schools, Oxford and Cambridge Universities, and women-only private members clubs.

Our findings suggest the elite girls’ schools represent very powerful channels of elite formation; alumni have been around 20 times more likely to reach elite positions than other women born in the same birth cohorts. There is also evidence of an ‘old girls’ network’ where alumni of these schools benefit from passing through a common set of elite institutions that further facilitate access to positions of power and influence. Second, however, we find that both elite schools and the wider old girl network have been consistently less propulsive than their male counterparts in Britain. We argue this difference in rooted in the more ambivalent aims of girls’ elite education in Britain, where there has been a longstanding tension between promoting academic achievement and upholding traditional processes of gendered social reproduction. Third, and connected to this, we find that elite women who have attended private schools are more likely to have direct connections to other people in Who’s Who – particularly spouses. This, we explain, reflects the specificity of channels of elite recruitment for women, particularly in the mid 20th century. Here, in a context of entrenched masculine domination and powerful institutional and cultural barriers to occupational progression, women often relied on male partners to facilitate access to elite positions.

Gendering the sociology of elite recruitment: Elite schools and the old girl

Elite schooling in a number of countries plays an important role in the attainment of leading positions of prestige and power (Bourdieu and Passeron Citation1979; Courtois Citation2017; Hartmann Citation2006; Maxwell and Maxwell Citation1995). Here - in a literature known as the ‘sociology of elite recruitment’ (Stanworth and Giddens Citation1974) - passage through prestigious schools is theorised to function as both as a status signal in its own right and as a proxy for highly valued attributes inculcated via the schools’ distinct curricula and extra-curricula provision (Weinberg Citation1967). These signals are then recognised and rewarded by gatekeepers, who grant opportunities that are ‘hoarded’ from outsiders (Parkin Citation1983).

More specifically, following Stevens et al. (Citation2008), it is possible to argue that elite private schools perform four main functions in terms of elite recruitment. First, they are ‘sieves’ that strongly regulate access to elite positions. Here they are implicated in dual processes of ‘social sieving’; on one hand sifting for ‘demographically elite’ students based on class background and/or financial resources (Gaztambide-Fernández Citation2009; Khan Citation2011) and, on the other, informing the sieving processes of other gatekeepers, such as elite universities or high-status employers, who often use private schools as strong status signals when allocating elite positions (Chetty et al. Citation2017).

Second, elite schools are ‘incubators’ where elite identities coalesce and take shape (Khan Citation2011). They often constitute what Bourdieu called ‘miniature closed societies’, where prolonged and intense contact with already-similar classmates constitutes a pivotal source of secondary socialisation and generates a distinct elite identity that has long-lasting effects on embodiment, attitudes, taste and lifestyle (Bourdieu Citation1996: 180-4). Importantly, such self-presentational traits often go on to function as forms of ‘embodied cultural capital’ that are then (mis)recognised as merit or talent in a range of elite occupational settings (Friedman and Laurison Citation2019). In Britain, for example, the most elite boys schools have long been associated with the cultivation of a particular synthetic elite identity. This has traditionally been embodied in the understated figure of the ‘gentleman’, who combines certain modes of comportment such as received pronunciation (RP), an elaborate vocabulary, and emotionally detached self-presentation (Scott Citation1991).

Third, and connected to this, elite schools are also ‘temples’ that provide entrants with legitimate forms of official academic and cultural knowledge. Here a ‘hothouse cultivation’ is achieved via a distinct and often classical academic curriculum, rarefied extracurricular activities and sports, and an emphasis on particular ‘ways of knowing’ that foreground generalism over expertise (Bourdieu Citation1996; Khan Citation2011). Again gatekeepers, such as employers or universities, recognise and reward these forms of knowledge, privileging sporting or extracurricular activities disproportionately incubated in elite schools (Reeves and Vries Citation2019; Rivera Citation2015; Van Zanten Citation2009) demanding consecrated academic knowledge, such as Latin and Greek, only inculcated in certain schools (Karabel Citation2006), or considering a generalist intellectual ‘ease’ as a key marker of cultural fit (Ashley et al. Citation2015; Rivera Citation2015).

Finally, schools are ‘hubs’ that bring together and commingle a wide array of other elites (Stevens et al. Citation2008). In this way, they are often implicated in the development of lasting networks that function as social capital and are intimately connected to later elite trajectories.Footnote1 This hub function has traditionally been captured through the folk concept of the ‘old boys’ network,’ which describes an enduring set of social connections and an ethos of mutual support among former pupils of male-only elite schools (Scott Citation1991; Weinberg Citation1967). This is most prominently associated with Mills (Mills Citation1956: 64-67, 278-83), who argued that the shared experience of elite schooling played a key role in ‘fusing psychological and social affinities’ among the U.S. ‘power elite.’ Such networks are often further sustained via other elite institutions such as elite universities and private members clubs that provide further hubs for elite school alumni to further cultivate and deepen relationships (Cookson and Persell Citation1985).

The link between private secondary schools and elite recruitment has been explored in a range of national contexts – most prominently the US and UK, but also France, Australia, Argentina, and Japan (Prosser Citation2015; Saltmarsh Citation2015; Zanten Citation2015). In England, private schools have historically possessed a particular propulsive power, with a number of scholars arguing that they are more prestigious, and more academically and socially selective than in other countries (Walford Citation2006). In particular, a small set of 9 male-only boarding schools – known as the ‘Clarendon schools’Footnote2 - have long been considered ‘the chief nurseries’ of the British elite (Honey Citation1977). Today, the propulsive power of these elite Clarendon Schools has somewhat diminished but they remain extraordinarily powerful channels of elite formation – particularly Eton College (Reeves et al. Citation2017).

While elite recruitment studies has produced a rich sociological literature, there remains conspicuous empirical and conceptual blind spots. One of the most significant of these is gender. We know of no studies, for example, that specifically examine the educational channels through which women are recruited to elite positions. Instead, this literature overwhelmingly foregrounds the experiences of men (Stanworth and Giddens Citation1974) or, in more recent studies, simply does not distinguish gender at all (Sutton Trust Citation2019). This is particularly the case in terms of elite secondary schooling in the UK, where there has been an enduring focus – both in scholarly work and in the wider public imagination – on the power of an old boys’ network.

This reflects a wider blind spot in the sociology of elites regarding the role of gender and masculine domination in understanding processes of elite formation (Clancy and Higgins Citation2021; Cousin, Khan, and Mears Citation2018). There have of course long been women within the elite, and it is important to register a rich feminist literature probing the central role women play in in both domestic processes of social reproduction and more generally the operation of elite social and familial networks (Chalus Citation2005; Glucksberg Citation2016; Yanagisako Citation2018). However, such inquiry has not extended to elite recruitment studies. Here, flowing from the reality that elites in the public sphere have traditionally been, and continue to be, largely male (and white), this literature has largely ignored how elite women use educational institutions, and the networks (e.g., partners) that flow from this, to secure occupational positions of power.

Yet the elision of girls’ elite schooling is problematic for at least three reasons. First, it ignores the fact that, in many national contexts, expensive and well-known fee-paying girls’ schools (as well as women-only university colleges and women’s private members clubs) have existed for a long time (Avery Citation1991; Graham Citation2017). Moreover, in many national contexts such schools have become as, if not more, successful than their male counterparts in terms of educational attainment - a key prequisite for elite recruitment (The Spectator Citation2021).

Second, the number of women in positions of power and influence has dramatically increased over the last 150 years (Zweigenhaft and Domhoff Citation2014). In the UK, for example, only 1.61% of entrants to Who Who’s born in the 1850s were women. Among those born in the late 1970s, in contrast, this figure has risen to ∼31%. There have always been women in the elite, and many of these women have been influential within their social and familial networks, and in liminal ways in the public sphere even before they were granted the same rights as men (Gleadle, Citation2009). As Bell (Citation1974) reminds us, the creation of elite directories like Who’s Who was a ‘social process’, and one which was undoubtedly gendered. For example, it was only in 1897, when Douglas Slade assumed the editorship, that women were even included in Who’s Who for the first time (Chester, 2001).

However, despite these important caveats, we nonetheless maintain that the increase of women in Who’s Who is sociologically significant. This is because entrance to Who’s Who is largely premised on widely recognised public and occupational achievement, and therefore captures women’s growing involvement in an elite professional public sphere previously occupied almost entirely by men. Yet, we know fairly little about what channels of elite recruitment made this dramatic change possible for women, and specifically whether elite girls’ schools have played the same extraordinary propulsive role as their male counterparts.

Third, this gap continues despite a rich sociological literature on elite girls’ schooling that has, through largely qualitative work, underlined the specificity of girls’ private schools in cultivating specific femininities (Allan and Charles Citation2014; Kenway et al. Citation2015). Like their male counterparts, these schools foster dispositions of ‘assuredness’ (Forbes and Lingard Citation2013) or ‘surety’ (Maxwell and Aggleton Citation2016) and they are sites where working-class and ethnic minority students are frequently othered and stigmatised (Horvat and Antonio Citation1999). Despite these similarities, these schools are preoccupied with cultivating ‘appropriately gendered’ young women (Maxwell and Aggleton Citation2014).

Yet, this literature has provided very little insight into the power of these school to propel women into elite destinations, and how this may have changed over the course of the 20th century. Until now, the kind of large-scale longitudinal data source needed to answer these kind of questions has simply not been available. In this paper we plug this gap via an unusual dataset—120 years of biographical data contained within Who’s Who. Specifically, drawing on the individual schools mentioned by female entrants, we assess the propulsive power of girls’ private schools; how successful have they been at delivering their alumni into elite occupational positions, how does this compare to elite boys’ schools, how has their power changed over time, and what is their relationship to other channels of elite recruitment?

The dilemma of ‘double conformity’: Locating girls’ schools in the history of British elite education

Before we move to our analysis, it is important to introduce our case of girls’ private schools in Britain, and briefly explain how their historical development differed significantly from their male counterparts.

The explicit aim of the male public schools was to prepare their alumni for public life. These schools explicitly cultivated a synthetic set of ‘gentlemanly’ dispositions that could be recognised and rewarded in multiple occupational fields (Scott Citation1991). Almost all of the fee-paying schools for boys modelled themselves on the elite Clarendon schools (Weinberg Citation1967) and this generated a remarkable degree of consistency across the entire landscape of elite boys’ schools. This coherence did not exist for girls. In part this was because girls’ schools emerged during a period in which there was a great deal of debate about the appropriate role of education in the lives of women; the question of how, and to what level, girls should be educated was a doggedly persistent theme throughout the mid-to-late 19th and early 20th centuries (Jordan Citation1991).

One consequence of this debate was the creation of a fractured ecosystem that has continued to inform the shape of elite girls’ schooling ever since. Early girls’ schools (many that were set up before this debate even fully began) were private in the truest sense of the word, often set up as family businesses operating within – or mimicking – the space of the home (De Bellaigue Citation2007). This meant that from the beginning the individual character of a headmistress could radically affect how the school operated: what subjects were valued, and whether girls were encouraged to go onto university or not (Pedersen Citation1987).

This school-level variation produced two kinds of educational institutions by the later nineteenth century. One focused on ‘feminine accomplishments’ rather than academic attainment; on preparing their students to be a good wife and mother in the private sphere (Howarth Citation1985). But alongside this there were other headmistresses who were influenced by pioneering educationalists and campaigners Frances Mary Buss and Dorethea Beale (Avery Citation1991), whose outstanding schools were praised by the 1868 Taunton Commission (Jordan Citation1991). These schools were initially more socially heterogenous than their male counterparts but, more importantly, they were focussed on academic excellence, particularly at the private day ‘high-schools’ (Howarth Citation1985). These headmistresses were more likely to want their girls to go on to elite destinations in the public sphere and yet the success of these schools was always predicated on never straying too far from the dominant gender norms of the day. These schools struggled then to achieve a kind of ‘double conformity’ (Delamont Citation1978) to the male syllabus and to the expectations of femininity, and as a result have never been able to entirely reject the emphasis on ‘feminine accomplishments’.

Eventually, the schools solely focussed on traditional femininity became far less popular as gender norms shifted but the Buss- and Beale-inspired institutions continued to wrestle with the challenges of this ‘double conformity’ (Delamont Citation1978); and it is potentially this struggle which has influenced the propulsive power of these schools in relation to their alumni, and to boys’ schools more generally.

Data and method

We base our analyses on the historical database of Who’s Who, the leading biographical dictionary of ‘noteworthy and influential’ people in the UK, which has been published in its current form every year since 1897. Who’s Who makes selections based on a mix of positional and reputational grounds. Around 50 percent of entrants are included automatically upon reaching a prominent occupational position. These positions span multiple professional fields. For example, Members of Parliament, peers, judges, ambassadors, FTSE100 CEOs, Poet Laureates, and Fellows of the British Academy are all included by virtue of their office. The other 50 percent of entrants are selected each year by a board of long-standing advisors, who make reputational assessments based on a person’s perceived impact on British society. The reputational part of the selection process is not entirely transparent in part because we do not know much about the people who sit on this panel. This is intentional. As Katy McAdam, Head of Yearbooks at Bloomsbury, explained to the authors in an interview, the anonymity of the panel helps to ensure that this process is not influenced by politicking. On top of this, entries cannot be purchased. Instead, a long-list is drawn up based on research into individuals who have recently achieved a noteworthy professional appointment or who have experienced sustained prestige, influence, or fame (“It’s our job to reflect society, not to try and shape it”, as McAdam has noted).Footnote3

Who’s Who contains two separate but connected data sources: (1) Who’s Who and (2) Who Was Who. Who’s Who is the current directory of every individual included in the published version of the book. Over time its entrants have consistently represented approximately .05 percent of the UK population (or 1 in every 2,000 people). When a person included in Who’s Who passes away, their record is transferred into Who Was Who. We combine these datasets and treat them as one data source, referring to it collectively as Who’s Who.

Who’s Who contains ∼130,000 short biographies of individuals that have had a sustained influence on British life, with ∼9,500 entries focussed on women (Reeves et al. Citation2017). Entries include information on the schools and universities that entrants attended, the clubs that they were a member of, and also the fields of work for which they are most well-known. We also have information on the names of their parents and their spouse.

First, we examine entrants’ schooling. As we have already discussed, it is hard to identify a clear-cut set of elite girls’ schools in the UK. To address this we draw on the work of Howarth (Citation1985), who defines elite girls’ schools in terms of their success at sending their girls to Oxford and Cambridge. We therefore collected data on Oxbridge matriculants between 1891 and 1913 from Howarth (Citation1985) and Oxford matriculants between 1901-1979 from Greenstein (Citation1994) to identify 12 girls’ schools which had been most successful in achieving places at Oxbridge, relative to when they opened and to their size. The reason we alight on 12 is that our aim is to create a group of girls’ schools that educate a similar number of students to the 9 male Clarendon Schools – approximately 6000 pupils (see Appendix 1 for more details). Our 12 girls’ schools are: Cheltenham Ladies’ College, North London Collegiate School, St Paul’s Girls’ School, Oxford High School for Girls, Queen’s College on Harley Street, St Leonards in St Andrews, Clifton High School for Girls, King Edward VI High School for Girls in Birmingham, Roedean, Godolphin & Laytmer Girls’ School, Wycombe Abbey, and the Benenden School.Footnote4

We also examine a second-tier of elite girls’ schools, based on ∼200 schools that are represented by umbrella organisation - the Girls’ Schools Association (GSA). This is a prestigious grouping of elite girls’ schools, representing approximately 2% of all girls of a similar age. We compare it here to an allied group of ∼200 boys elite schools that make up the Headmasters’ Conference (HMC), which also represents ∼2% of all boys of a similar age.

Second, we look at university education. Here we are principally concerned with Oxford, Cambridge, and 24 research-intensive universities that make up what’s known as the Russell Group. These were, and still are, the most prestigious universities in the United Kingdom, but many of the universities in the Russell Group group are much newer and as a result more progressive in terms of gender. Third, we consider memberships of private, members-only clubs. These clubs have predominantly been dominated by men but there were also a number of mixed-sex and women-only elite clubs in the UK during this period, such as the University Women’s Club and the Literary Ladies’ Club, and some have noted how important these organizations were for women’s movements over this period (Evans Citation2021). Finally, we explore the social ties of elite women. In particular we examine how many women in Who’s Who also had a partner that was also in Who’s Who, These matches are identified by Who’s Who themselves through their research team.

Our analysis is simple. Given that we have the whole population of Who’s Who entrants, we simple calculate the proportion of female entrants who attended one of these elite schools or an elite university, and then compare these with the rates of men. We therefore conduct a cohort analysis based on a series of birth cohorts born between 1830 and 1969. We conduct the cohort analysis by plotting trends over time for different groups. These time series plots allow us to narratively explore changes in elite recruitment. We also draw on census data and other records from schools and universities to calculate odds ratios of the chances of reaching Who’s Who given a woman attends one of these schools relative to other girls’ schools. This approach allows us to put the issue of societal sexism to one side; not because it is unimportant but rather because it is too important. We know that all women were far less likely to reach the elite and so when we examine these schools we only consider them in relation to all other women born in the same period. We also compare these odds ratios with similar statistics for men, giving us a comparative perspective of how successful these girls and boys’ schools were at propelling their alumni into the elite.

Results

Old girls versus old boys: who enjoys the greatest advantage?

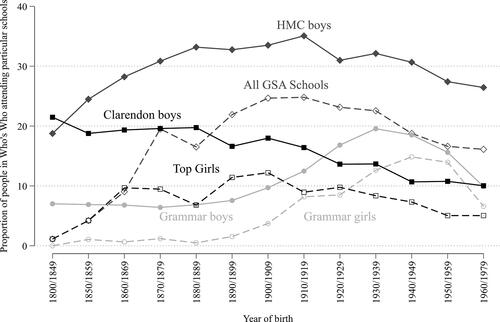

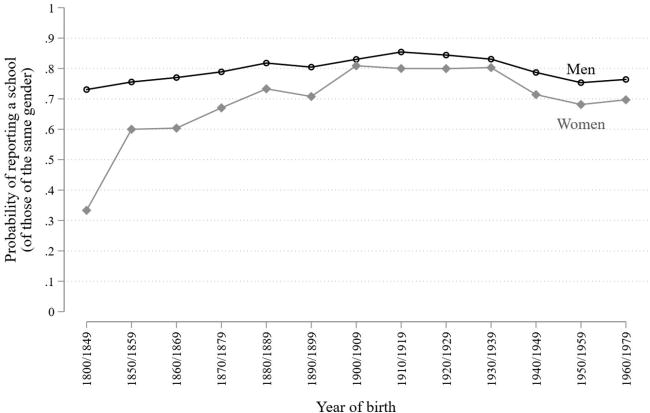

We begin our analysis by exploring the changing educational composition of men and women in Who’s Who across birth cohorts. We focus on those born between 1840 and 1979. In we plot the percentage of men or women in Who’s Who who report attending one of three types of schools: elite boys’ or girls’ schools (the ‘Clarendon Schools’ for boys and the 12 girls’ schools outlined above), second-tier schools (HMC schools for boys and GSA schools for girls), and finally grammar schools for both boys and girls.

shows that elite schooling was fairly uncommon among early female entrants to Who’s Who. This is partly because very few young women attended school in the early and middle parts of the nineteenth century and many were instead educated at home, often by governesses. In addition, as described above, it was from 1870 onwards that Britain witnessed an explosion of girls’ schooling and many of the elite girls’ schools we focus on were founded in this period, including North London Collegiate School and Cheltenham Ladies’ College. Notably, these newer educational institutions turned out to be far more successful at propelling their alumni into the elite than many of the more venerable girls’ schools, some of which had been around for centuries (Web Appendix 1).

But, despite the explosion in girls’ schooling, there is no period in which any of our types of girls’ school outperform their male counterparts. Even at the point at which the propulsive power of elite girls’ schools seemed to reach its peak, among those born around the turn of the twentieth century, the percentage of female entrants attending an elite girls’ school (12%) was still significantly lower than that of male entrants attending a Clarendon School (17%). Likewise, while the GSA schools educated around 25% of female entrants born in the first decade of the twentieth century, the HMC schools educated over a third (∼34%) of men.

One possible explanation for this divergence is simply reporting error. Women may be far less likely to mention attending an elite private school in their entries than men. The evidence, however, does not support this argument. While women are slightly less likely than men to provide information about their educational background in Who’s Who (see Appendix 2), the gap is modest and unlikely to explain the differences we see in . In fact, even when we manually try to correct our data on women’s education using publicly available information,Footnote5 we find very few female false negatives, that is, women who did attend a private school but neglect to mention this in their entries. This suggests that elite schools were just not as dominant in the trajectories of elite women as they were for men.

Our results do not, of course, imply that these girls’ schools were weak. On the contrary, we estimate that across the period of our analysis a women who attended one of the 12 most elite girls’ schools was approximately 20 times more likely to end up in Who’s Who than a women who had attended any other kind of school. Old girls, in short, have long enjoyed a tremendous advantage over other young women in reaching positions of influence. However, in comparative terms, this advantage was much weaker than that enjoyed by old boys (Clarendon alumni, for example, were approximately 35 times more likely to reach WW in the same period/cohort than other men).

Old girls and elite universities

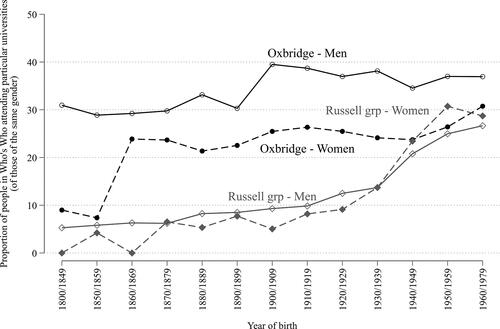

Women in Who’s Who may have been less likely to attend an elite school than men but were they also less likely to attend elite universities? shows the percentage of men and women in Who’s Who who attended two different types of elite university, Oxbridge (Oxford and Cambridge) and the Russell Group.

Until the most recent cohorts, around 25% of women in Who’s Who attended Oxford or Cambridge. This is consistently lower than the proportion of men who attended Oxbridge, which has been around 37% for those cohorts born since the beginning of the twentieth century. Bear in mind, here, that part of the criteria we have used to define these girls’ schools as ‘elite’ is their success at getting their alumni into Oxford and Cambridge. This makes the fact that these schools are outperformed by the Clarendon schools even more striking.

The trend for the Russell group universities is quite different, however. Men and women attending these institutions follow the same trajectory. Very few people attended these universities during the 19th and early part of the 20th century – in part because many of these institutions had only just been established. This changes rapidly after WWII and by the latest cohorts around 25% of both men and women in Who’s Who had attended one of these Russell Group universities.

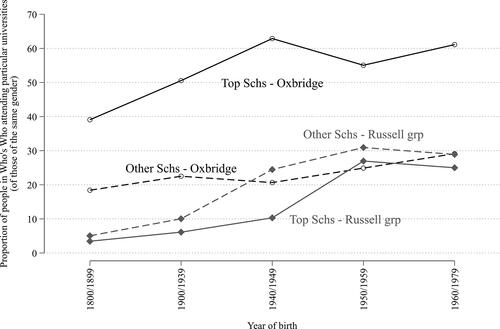

Behind these aggregate numbers, however, there is important variation across school type. As demonstrates, around 50% of those who attended an elite girls’ school also attended Oxbridge but only around 25% of those who attended other girls’ schools attended Oxbridge. This pattern is again different for the Russell Group universities, where similar numbers of women attended these other elite universities irrespective of the school they attended prior to their undergraduate studies.

This strong connection between a small set of elite girls’ schools and Oxbridge is reminiscent of the old boys’ network that helped forge the elite trajectories of men. Our data reveal that a similar, albeit weaker, relationship also existed between some elite girls’ schools and Oxbridge.

Other channels of women’s elite recruitment: clubs and partners

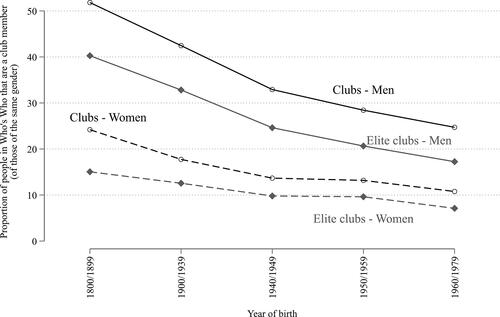

Beyond schools and universities, our results also indicate that two other channels of elite recruitment played an important role in forging women’s elite trajectories; private members clubs and partners. The role of private members clubs in bending the arc of male elite trajectories is well-known (Bond Citation2012). But, the role of these clubs for women has not been examined in similar depth. reveals that despite the most famous of such clubs being male-only, and membership rates being consistently higher among men, a significant minority of elite women were also members of these members-only institutions.

Those clubs that are especially common among women include the Albemarle club,Footnote6 the University Women’s Club,Footnote7 the Literary Ladies’ Club,Footnote8 and, in more recent years, the Reform ClubFootnote9 and the Atheneaum.Footnote10 Of course, what our analysis cannot show is whether access to these clubs preceded women’s inclusion in Who’s Who, and therefore possibly aided their entry, or whether they joined once they had achieved an elite position. What is clear, however, is that for both men and women in our data, clubs have been declining in prominence over this period. Indeed, the periods in which women have been most likely to be admitted to Who’s Who are also those periods in which club membership is lowest (less than 10% for those elite clubs). From this it is hard to conclude that clubs have been a significant channel of elite recruitment.

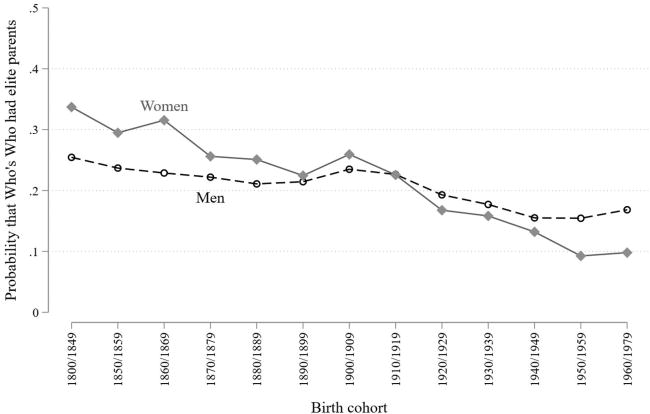

Family relations, however, might also be important and could include parents, partners, and even siblings. Interestingly we do not find strong evidence that women were more likely than men to have parents who are also members of the elite (see Appendix 3), although if anything women were more likely to have elite parents at the very beginning of our study period and slightly less likely at the end.

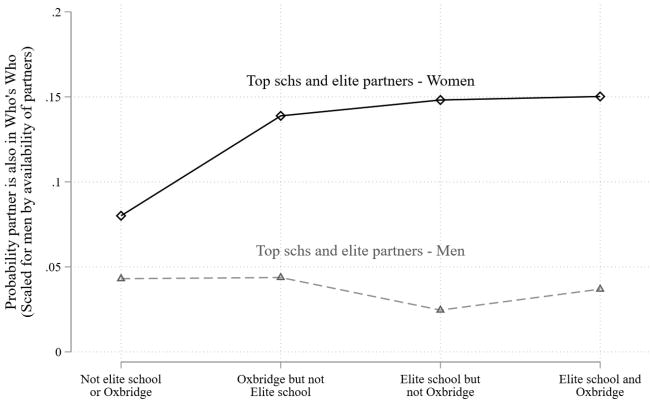

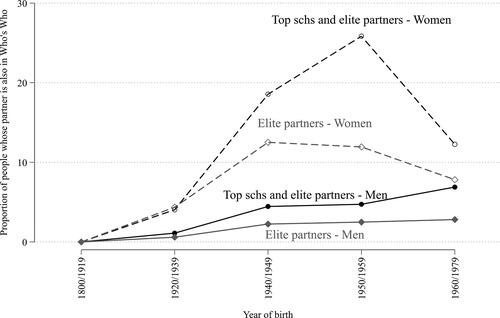

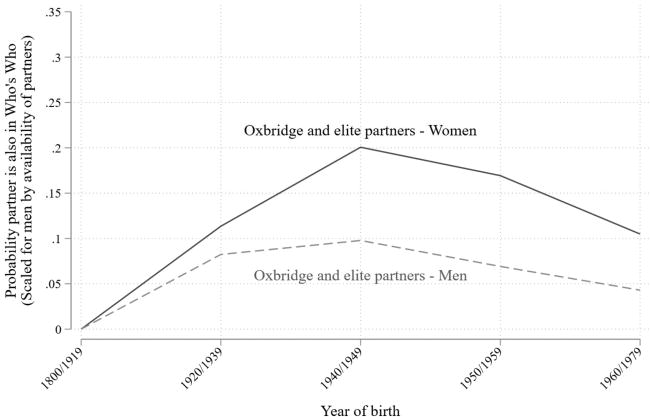

When we focus on partners, however, we find a much clearer gender split. In , we report the probability that men and women in Who’s Who have a partner in Who’s Who. What we find is that women in general are more likely to have a partner who is also a member of Who’s Who than men, and it is women from elite schools that are the most likely to have a partner that is also in Who’s Who. We also find that women who attended Oxbridge are more likely to have a partner that is also in Who’s Who (see Web Appendix 4 and 5). This connection seems to be particularly prominent for the women in Who’s Who that were born in the 1940s and the 1950s. For this cohort, a remarkable 25% of women in Who’s Who who had attended an elite school also had a partner in Who’s Who. We also find that even women who did not attend an elite school are more likely to have a partner in Who’s Who than men who attended a Clarendon school.

Discussion and conclusion

This article examines the educational channels of women’s elite recruitment in Britain over the past 120 years. Our analysis reveals two key results. First, we demonstrate that elite girls’ schools have been remarkably successful in delivering their ‘old girls’ into elite positions; the alumni of the 12 top girls’ schools have consistently been around 20 times more likely to reach Who’s Who than women who attended any other type of school. While sociological literature has long explored the advantages that flow from elite girls’ education (Walford Citation2006), this is the first analysis that we know of that has been able to quantify the relative advantage enjoyed by ‘old girls’ in terms of elite occupational outcomes. Indeed, a highly gendered tradition of scholarship in elite recruitment studies – long pre-occupied with the educational channels of men’s elite formation - has acted to obscure the importance of women’s elite education in understanding who secures positions of power and influence. In this way, we hope our analysis will encourage further heterodox explorations of elite recruitment, particularly those probing the specific educational channels through which other under-represented groups make their way into elite positions (Cousin et al. Citation2018).

While it is beyond the scope of this paper to fully elucidate the mechanisms underlying the tremendous propulsive power of Britain’s elite girls’ schools, here we draw on a range of historical and sociological literature to suggest some potential directions. Following Stevens et al’s framework (2008), for example, it is clear that such schools have long acted as distinct incubators of elite identities – particularly dispositions of ‘assuredness’ (Forbes and Lingard Citation2013), ‘surety’ (Maxwell and Aggleton Citation2016) and ‘ease’ (Khan Citation2011) – that are clearly central in shaping young women’s desire, expectation and confidence to push for elite positions. Equally, over time these schools have also increasingly become recognised as temples that inculcate the right kind of rarefied ‘scholastically elite’ curriculum (Gaztambide-Fernández Citation2009) that is highly valued in the employment market. Indeed in important ways these schools have continued to model much of their pedagogical offering on the traditional English education synonymous with the Clarendon schools (Walford Citation1993), emphasising both academic excellence but also the development of the ‘whole person’ via particular sports and extra-curricula activities (Maxwell and Aggleton Citation2016).

Beyond this, our own analysis also points to two additional mechanisms that may underpin the ‘success’ of girls’ schools. First, we demonstrate the importance of a cumulative pathway to elite recruitment beginning in elite girls’ schools but then augmented by passage through Oxford and Cambridge universities. The existence of this channel suggests that it is possible to tentatively talk of an ‘old girls’ network’ in the UK, where passage through a set of elite educational institutions is associated with a particular advantage in accessing elite positions (Scott Citation1991). We would stress, however, that understanding precisely how this channel facilitates elite recruitment, and how it compares to the male equivalent, remains an important question for future research. For example, are such pathways decisive because they provide women with networks that function as social capital, as with the old boys network, or is this more about the distinct elite signal provided by such double institutional consecration?

However, while women’s elite recruitment may sometimes take place along similar institutional channels or pathways to those traditionally enjoyed by men, our analysis also underlines the specificity of some women’s trajectories – particularly given the historical context of entrenched masculine domination and profound barriers to women’s occupational achievement (Worth Citation2022). In particular, our results show that women in Who’s Who have consistently been more likely than men to have a partner who is also in Who’s Who, and that this is particularly the case for women who attended elite private schools and/or Oxbridge.

One possible reading of this is that, for many elite women, an elite male partner may have supported their occupational trajectory. For elite families in the early 20th Century, marriage as opposed to pursuing a career was seen as a much more secure mode of achieving social status. Indeed, such families were often concerned that an academic education would make their daughters undesirable ‘bluestockings’ that bored prospective husbands (Graham Citation2017; Thane 2004). Our argument, that marriage could actually support women’s careers during the mid-twentieth century, represents an important development in the role of marriage in women’s elite recruitment and potentially in elite reproduction more broadly.

The importance of marriage underlines a key difference between elite boys’ and girls’ schools; their role as hubs. While elite schools acted as a key setting for boys to build networks that were often then central to later occupational trajectories, women were less able to leverage fellow ‘old girls’ as direct sources of social capital. Instead, men still represented the most realistic sources of social capital, particularly via romantic relationships (Stone and Stone Citation1995). This was exemplified in terms of changing attitudes towards university attendance and specifically the goal of propelling girls to Oxbridge. As late as the 1950s fierce debates continued about whether it was a ‘waste’, and in some sense ‘cruel’, to send women to university and get their hopes up (Dyhouse Citation2005). In particular, these accounts stress that Oxbridge continued to be perceived as an excellent place for women to find a husband. During the 1960s, for example, 60% of women that graduated from Oxford (and went on to marry) chose spouses who were also Oxford graduates (Howarth Citation1994).

This, we argue, suggests that the operation of an old girls’ network may have been contingent, at least in part, on its connection to the old boys’ network; in other words, elite girls’ schools were not necessarily network hubs for women (in the same way as they were for men) but instead provided the resources and platform for many women to meet elite men who may have directly or indirectly (through their networks) aided their career, a pattern which has resonances with more recent work on girls’ schools (Maxwell and Aggleton Citation2010).

One final noteworthy feature of these results is that the connection between schooling, gender, and partners is especially prominent among a specific cohort of women – those born in the 1940s and the 1950s. Again this chimes with the work of historians, who have argued that this cohort were a crucial transition generation (Abrams Citation2014). While the careers of women born before this were severely curtailed by marriage bars (requiring them to resign from certain jobs when they got married) (Glew Citation2016), and those born after benefited from the passing of 1970s equality legislation, these were the daughters of ‘post-war promise’ who both pushed for, and lived through, second-wave feminism (Worth Citation2022). They had significantly greater access to elite universities and careers than earlier generations of women but their opportunities were also severely constrained by gender (Worth Citation2019). It makes sense, then, that in order to break into the upper echelons of elite institutions they required not only an elite education but also an elite partner that would help them network and navigate the difficulties of entering such occupational spaces for the first time.

This gendered lens is important, we argue, because it forces us to rethink what sociologists have often presumed to be the dominant channels of recruitment to elite occupational positions. In particular it indicates that for women, operating in societies structured by masculine domination, access to elite positions has never been entirely ‘family mediated’ or ‘school mediated’ (Bourdieu Citation1996). For example, the direct family mode of elite reproduction - via the transmission of property rights - were rarely ever passed to daughters (they almost always were transmitted via dowry to their husband). Even today, the women associated with family-run firms are often required to step aside and seek out appropriate partners so that male siblings can assume leadership of the business (Yanagisako Citation2018). Equally, as our results indicate, the daughters of privileged families may have acquired the necessary credentials by attending elite schools and universities but they still often relied on having an elite partner to access positions of power and privilege themselves. Elite reproduction for women therefore has frequently been ‘partner mediated’; that is, contingent on marrying into another family with power and privilege. Future research should take up this issue in more detail.

While elite girls’ schools have been consistently and emphatically more propulsive than other forms of girls’ schooling, our second key result clarifies that they are still (relatively speaking) far less successful than the top boys’ schools in terms of elite recruitment. This may not seem surprising considering what we know about the profound glass ceilings faced by women across the last 120 years (England Citation2010). Yet here we would reiterate that our odds ratios already account for the base rates at which women enter the elite so the question is not so much one of gender differences in overall elite recruitment but why the alumni of elite girls’ schools are relatively less common among elite women than the alumni of elite boys’ schools are among elite men.

Here we return to the history of girls’ schools, and in particular to scholarship indicating that the functions of elite schools - as sieves, incubators and temples – operated quite differently for girls (versus boys) for most of the 20th century. As sieves, for example, elite girls’ schools were less likely, particularly in the earliest years, to recruit students from Britain’s most elite families in the same way as the Clarendon Schools (Walford Citation1993).Footnote11 Indeed for much of the 19th century, many elite women, the daughters of aristocratic families, didn’t even attend school because they were educated at home by private tutors, and those that did tended to attend boarding schools functioning as finishing schools and focused on cultivating ‘ladies of leisure’ skilled in reading, writing, singing, dancing, needlework and household management (Walford Citation2006: 85).

Connected to this, elite girls’ schools also acted as much less reliable status signals. In particular, the hierarchy of girls’ schooling lacked the clarity which coalesced around boys’ schools such as the Clarendon or HMC schools (Howarth Citation1985). The historical literature underlines that this was partly driven by a number of structural barriers that prevented girls’ schools from developing the same level of social and cultural power as their male counterparts. Firstly, they were often initially unable to follow the same organisational model as their male counterparts. While the most prestigious boys’ schools evolved from medieval collegiate foundations, ancient grammar schools, or were set up by public trusts (Walford Citation1993, Citation2006), girls’ schools often began as small, fee-paying establishments (Avery Citation1991) or they were day schools which catered to local (potentially more socially heterogenerous) students.

Related to this, girls’ schools tended to suffer from financial precarity. Unlike the most elite boys’ schools, they could not rely upon the donations of elite alumnae to build their endowment, and even where sister schools of existing boys’ schools were set up later in the nineteenth century, they were often given a much smaller percentage of existing endowments (Avery Citation1991). Combined, these distinctive aspects of girls private schools made it much harder for a clear-cut set of ‘elite’ schools to emerge, and therefore to coalesce as common status signals for gatekeepers to use in their sifting processes.

Girl schools not only lacked the legacy, economic endowments, and social prestige of boys’ schools but they also lacked the same cultural coherence as ‘incubators’ of common elite identities and ‘temples’ of legitimate knowledge. This was because, from their inception, elite girls’ schools had a more complex, and often ambivalent, set of aims and objectives which required them to deliver both educational excellence and gendered social reproduction – the bind of ‘double conformity’ (Delamont Citation1978).

Thus perhaps most important in understanding why girls’ schools were less successful in propelling their alumni was that most remained at least somewhat ambivalent about the goal of (occupational) propulsion in the first place (Aiston Citation2004; Avery Citation1991). For example, what is most striking about the girls’ schools that became most successful in terms of producing elite women is that they were almost all founded in the second half of the nineteenth century: a particular moment in the history of education in general but also of women’s education in particular (Jordan Citation1991). The latter part of the nineteenth century was marked by an explosion of fee-paying schools alongside charitable institutions which were supported by government grants. The education of women was part of this broader movement but it was not an uncontested shift (Purvis Citation1991). Proto-feminists of this era frequently advocated for women’s education but they often did so in terms which adhered to the gender politics of the time, arguing that education would make women better partners and mothers (Jordan Citation1991). All of the elite girls’ schools in our data emerge out of this milieu. While these schools quickly set themselves apart from the other girls’ schools that were opening over this period (many of whom were very successful at helping their alumni enter the elite through marriage) they could not depart too far from the gender norms of the time. This enduring ambivalence – between pursuing educational attainment and producing an ‘appropriate’ femininity - ensured that these schools were never able to prepare their alumni for positions of power and public prominence in the same unabashed way as the Clarendon Schools (Dyhouse Citation1977).

What is significant, sociologically, about this ambivalence is that again it illustrates how a gendered lens disrupts some of the assumptions that underpin the sociology of elite recruitment. It is possible to argue that one principle this work tends to presume, for example, is that the primary aim of elite schools is to propel its alumni toward elite occupational positions (Stanworth and Giddens Citation1974). Yet what the history of girls schooling suggests, in contrast, is that girls’ education has always been more ambivalent about the goal of elite occupational recruitment (Aiston Citation2004; Graham Citation2017). This is not to say that it hasn’t been engaged in a similarly aggressive project of elite reproduction, but that the elite destinations envisaged for women have always been more complex, multifaceted, and even contradictory. Reflecting on this in light of the historical data deployed in this paper, we would suggest that if elite recruitment scholars want to fully understand the propulsive power of elite schooling, and the different shape that propulsion may take for men and women, they may need to employ, and compare across, a wider range of outcome measures than simply occupation, including partner’s occupation and household income and wealth. For example, recent work on assortative mating and the influence of this on income inequality (Greenwood et al. Citation2014) reinforces the importance of this more rounded view of elite reproduction and likewise challenges some of the assumptions regarding how we conceptualise contemporary male and female eliteness. It may be only through a more holistic analysis of both women’s and men’s elite recruitment and outcomes that we are able to properly register the multifaceted propulsive powers of elite education.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the European Research Council Horizon 2020 for funding the research project ‘Changing Elites’ (Grant no: 849960 CHANGINGELITES), and Bloomsbury Publishing for allowing us to make use of the Who’s Who database.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This hub function is often considered particularly acute among those attending elite boarding schools, who spend extended periods in each other’s company and therefore often forge particularly intense, intimate and enduring friendships with their classmates (Scott Citation1991).

2 These schools, which cater primarily for children aged between 13-18, are: Charterhouse, Eton, Harrow, Merchant Taylor’s, Rugby, Shrewsbury, St Paul’s, Westminster, and Winchester College.

3 It does not seem that the composition of the people admitted into Who’s Who through the positional route are different from those admitted through the reputational route. For example, ∼7% of the women who were positional elites came from these top girls’ schools. Similarly, 6.5% of the women who were more reputational elites came from these top girls’ schools. The lack of any variation here suggests the panel is not driving the patterns we see in the data.

4 There is perhaps one notable absence from this list: Manchester High School for Girls. This is a school which is frequently discussed in the historical literature around top girls’ schools and so the fact it is missing is noteworthy. Indeed, even in our data Manchester only just misses the cut off. It is true that Manchester was among the top schools in the early part of the twentieth century and was, as Howarth’s data shows, among those schools that was regularly sending their girls to Oxford and Cambridge. However, this seems to have changed after 1940. There are very few alumni from Manchester that attend Oxford after 1940 in our data and it is noteworthy that, unlike, many of the other schools on this list that they are no longer one of the most academically successful schools. In short, Manchester High School for Girls started off as being quite prestigious but seems to have been overtaken by other (in some cases newer) schools, such as St Paul’s and Benenden.

5 Here, we used research assistants to search other historical sources for women in Who’s Who to see if we could find additional information about their schooling.

6 Founded in 1874 and open to both men and women. It’s notoriety was ensured when the Marquess of Queensbury burst into the club demanding to see Oscar Wilde but upon being refused entry the Marquess left a note ‘For Oscar Wilde, posing somdomite’.

7 Founded in 1883 by the founder of Girton College, Cambridge University, this club was intended for ‘graduate and professional women of varied backgrounds and interests’.

8 Founded in 1889 by Honnor Morten, the club was supposed to provide a literary equivalent to the Savile Club.

9 Founded in 1836, this club was the home of those committed to progressive political ideas and was the first male-only club to allow the admission of women in 1981.

10 Founded in 1824 as a club for male and female intellectuals but women have only been formal members since 2002.

11 We have already noted, for example, that Princess Anne attended Benenden, one of our elite schools, but when these schools first started they were likely more socially heterogenous than the equivalent boys’ schools.

References

- Abrams, Lynn. 2014. “Liberating the Female Self: Epiphanies, Conflict and Coherence in the Life Stories of Post-War British Women.” Social History 39 (1): 14–35. doi:10.1080/03071022.2013.872904.

- Aiston, S. J. 2004. “A Good Job for a Girl ? The Career Biographies of Women Graduates of the University of Liverpool Post-1945.” Twentieth Century British History 15 (4): 361–387. doi:10.1093/tcbh/15.4.361.

- Allan, Alexandra, and Claire Charles. 2014. “Cosmo Girls: Configurations of Class and Femininity in Elite Educational Settings.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 35 (3): 333–352. doi:10.1080/01425692.2013.764148.

- Ashley, Louise, Jo Duberley, Hilary Sommerlad, and Dora Scholarios. 2015. “A Qualitative Evaluation of Non-Educational Barriers to the Elite Professions: June 2015.” Retrieved January 25, 2018 (http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/23163/).

- Avery, Gillian. 1991. The Best Type of Girl: A History of Girls’ Independent Schools. 1st edition. London: Andre Deutsch Ltd.

- Bell, Colin. 1974. “Some Comments on the Use of Directories in Research on Elites, with Particular Reference to the Twentieth-Century Supplements of the Dictionary of National Biography.” P 161–171. in British Political Sociology Yearbook: Vol. 1 Elites in Western Democracy. Vol. 1, edited by I. Crewe. London: Croom Helm.

- Bond, Matthew. 2012. “The Bases of Elite Social Behaviour: Patterns of Club Affiliation among Members of the House of Lords.” Sociology 46 (4): 613–632. doi:10.1177/0038038511428751.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1996. The State Nobility: elite Schools in the Field of Power. Oxford: Polity.

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and Jean-Claude Passeron. 1979. The Inheritors: French Students and Their Relation to Culture. [1st ed. reprinted]/with a new epilogue. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

- Chalus, Elaine. 2005. Elite Women in English Political Life c. 1754-1790. Oxford: Oxford University Press on Demand.

- Chetty, Raj, John N. Friedman, Emmanuel Saez, Nicholas Turner, and Danny Yagan. 2017. “Mobility Report Cards: The Role of Colleges in Intergenerational Mobility.” Working Paper. 23618. National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w23618.

- Clancy, Laura, and Katie Higgins. 2021. “A Feminist Intervention in Elite Studies.” British Sociological Association Conference. Online.

- Cookson, Peter W., and Caroline H. Persell. 1985. “English and American Residential Secondary Schools: A Comparative Study of the Reproduction of Social Elites.” Comparative Education Review 29 (3): 283–298. doi:10.1086/446523.

- Courtois, Aline. 2017. Elite Schooling and Social Inequality: Privilege and Power in Ireland’s Top Private Schools. London: Springer.

- Cousin, Bruno, Shamus Khan, and Ashley Mears. 2018. “Theoretical and Methodological Pathways for Research on Elites.” Socio-Economic Review 16 (2): 225–249. doi:10.1093/ser/mwy019.

- De Bellaigue, Christina. 2007. Educating Women: Schooling and Identity in England and France, 1800-1867. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Delamont, Sara. 1978. “The Contradictions in Ladies’ Education.” in The Nineteenth-Century Woman: Her Cultural and Physical World. London: Croom Helm. 134–163.

- Domhoff, G. William. 1967. Who Rules America? Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall.

- Dyhouse, Carol. 1977. “Good Wives and Little Mothers: Social Anxieties and the Schoolgirl’s Curriculum, 1890-1920.” Oxford Review of Education 3 (1): 21–35. doi:10.1080/0305498770030102.

- Dyhouse, Carol. 2005. Students: A Gendered History. London; New York: Routledge.

- England, Paula. 2010. “The Gender Revolution: Uneven and Stalled.” Gender & Society 24 (2): 149–166. doi:10.1177/0891243210361475.

- Evans, Alice. 2021. “Smash the Fraternity.” Alice Evans. Retrieved November 22, 2021 (https://www.draliceevans.com/post/smash-the-fraternity).

- Forbes, Joan, and Bob Lingard. 2013. “Elite School Capitals and Girls’ Schooling: Understanding the (Re)Production of Privilege through a Habitus of ‘Assuredness.” P 50–68. In Privilege, Agency and Affect: Understanding the Production and Effects of Action. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Forbes, Joan, and Claire Maxwell. 2018. “Bourdieu plus: Understanding the Creation of Agentic, Aspirational Girl Subjects in Elite Schools.” International Perspectives on Theorizing Aspirations: Applying Bourdieu’s Tools. London: Bloomsbury 161–174.

- Friedman, Sam, and Daniel Laurison. 2019. The Class Ceiling. 1 edition. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Gaztambide-Fernández, Rubén A. 2009. The Best of the Best: Becoming Elite at an American Boarding School. 1 edition. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

- Glew, Helen. 2016. Gender, Rhetoric and Regulation: Women’s Work in the Civil Service and the London County Council, 1900-55. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Glucksberg, Luna. 2016. “Gendering the Elites: An Ethnographic Approach to Elite Women’s Lives and the Re-Production of Inequality.” III Working Paper Series (7). doi:10.31235/osf.io/ewbmx.

- Graham, Ysenda Maxtone. 2017. Terms & Conditions: Life in Girls’ Boarding Schools, 1939-1979. 1st edition. London: Abacus.

- Greenstein, Daniel I. 1994. “The Junior Members, 1900–1990: A Profile.” in The History of the University of Oxford: Volume 8 The Twentieth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Greenwood, Jeremy, Nezih Guner, Georgi Kocharkov, and Cezar Santos. 2014. “Marry Your like: Assortative Mating and Income Inequality.” American Economic Review 104 (5): 348–353. doi:10.1257/aer.104.5.348.

- Gleadle, Kathryn. 2009. Borderline Citizens: Women, Gender and Political Culture in Britain, 1815-1867. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hartmann, Michael. 2006. The Sociology of Elites. 1 edition. London: Routledge.

- Honey, J. R. De S. 1977. Tom Brown’s Universe: Public School in the Nineteenth Century. First Edition edition. London: Millington.

- Horvat, Erin McNamara, and Anthony Lising Antonio. 1999. “Hey, Those Shoes Are out of Uniform’: African American Girls in an Elite High School and the Importance of Habitus.” Anthropology Education Quarterly 30 (3): 317–342. doi:10.1525/aeq.1999.30.3.317.

- Howarth, Janet. 1985. “Public Schools, Safety-Nets and Educational Ladders: The Classification of Girls’ Secondary Schools, 1880-1914.” Oxford Review of Education 11 (1): 59–71. doi:10.1080/0305498850110105.

- Howarth, Janet. 1994. “Women.” in The History of the University of Oxford: Volume VIII: The Twentieth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jordan, Ellen. 1991. “Making Good Wives and Mothers’? The Transformation of Middle-Class Girls’ Education in Nineteenth-Century Britain.” History of Education Quarterly 31 (4): 439–462. doi:10.2307/368168.

- Karabel, Jerome. 2006. The Chosen: The Hidden History of Admission and Exclusion at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. Reprint edition. Boston, Mass.: Mariner Books.

- Kelsall, R. K. 1966. Higher Civil Servants in Britain. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul PLC.

- Kenway, Jane, Diana Langmead, and Debbie Epstein. 2015. “Globalizing Femininity in Elite Schools for Girls.” in World Yearbook of Education 2015: Elites, Privilege and Excellence: The National and Global Redefinition of Educational Advantage. London: Routledge. 153.

- Khan, Shamus. 2011. Privilege: The Making of an Adolescent Elite at St. Paul’s School. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- Khan, Shamus Rahman. 2012. “The Sociology of Elites.” Annual Review of Sociology 38 (1): 361–377.

- Maxwell, Claire, and Peter Aggleton. 2010. “The Bubble of Privilege. Young, Privately Educated Women Talk about Social Class.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 31 (1): 3–15. doi:10.1080/01425690903385329.

- Maxwell, Claire, and Peter Aggleton. 2014. “Agentic Practice and Privileging Orientations among Privately Educated Young Women.” The Sociological Review 62 (4): 800–820. doi:10.1111/1467-954X.12164.

- Maxwell, Claire, and Peter Aggleton. 2016. “Schools, Schooling and Elite Status in English Education – Changing Configurations?” L’Année Sociologique 66 (1): 147–170.

- Maxwell, James D., and Mary Percival Maxwell. 1995. “The Reproduction of Class in Canada’s Elite Independent Schools.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 16 (3): 309–326. doi:10.1080/0142569950160303.

- Mills, C. Wright. 1956. The Power Elite. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Parkin, F. 1983. Marxism and Class Theory: A Bourgeois Critique. Reprinted e. edition. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Pedersen, Joyce Senders. 1987. “Education, Gender and Social Change in Victorian Liberal Feminist Theory.” History of European Ideas 8 (4-5): 503–519. doi:10.1016/0191-6599(87)90147-1.

- Prosser, Howard. 2015. “Servicing Elite Interests: Elite Education in Post-Neoliberal Argentina.” in Elite Education. International Perspectives. London: Routledge.

- Purvis, June. 1991. History of Women’s Education in England. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

- Reeves, Aaron, Sam Friedman, Charles Rahal, and Magne Flemmen. 2017. “The Decline and Persistence of the Old Boy: Private Schools and Elite Recruitment 1897 to 2016.” American Sociological Review 82 (6): 1139–1166. doi:10.1177/0003122417735742.

- Reeves, Aaron, and Robert de Vries. 2019. “Can Cultural Consumption Increase Future Earnings? Exploring the Economic Returns to Cultural Capital.” The British Journal of Sociology 70 (1): 214–240. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12374.

- Rivera, Lauren A. 2015. Pedigree: How Elite Students Get Elite Jobs. Princeton ; Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Saltmarsh, Sue. 2015. “Elite Education in the Australian Context.” in Elite Education. International Perspectives. London: Routledge.

- Scott, John. 1991. Who Rules Britain? Oxford, UK ; Cambridge, MA, USA: Polity.

- Stanworth, Philip, and Anthony Giddens. 1974. Elites and Power in British Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stevens, M. L., E. A. Armstrong, and R. Arum. 2008. “Sieve, Incubator, Temple, Hub: Empirical and Theoretical Advances in the Sociology of Higher Education.” Annual Review of Sociology 34 (1): 127–151. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134737.

- Stone, Lawrence, and Jeanne C. Fawtier Stone. 1995. An Open Elite?: England 1540-1880. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Sutton Trust 2019. Elitist Britain. London: Sutton Trust.

- The Spectator. 2021. “The Oxbridge Files: Which Schools Get the Most Offers?” The Oxbridge files: which schools get the most offers? The Spectator.

- Useem, Michael. 1986. The Inner Circle: Large Corporations and the Rise of Business Political Activity in the U. S. and U.K. New Ed edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Van Zanten, Agnès. 2009. The Sociology of Elite Education. London: Routledge.

- Walford, Geoffrey. 1993. The Private Schooling of Girls: Past and Present. 1st edition. London, England : Portland, Or: Routledge.

- Walford, Geoffrey. 2006. Private Education: Tradition and Diversity. London: Continuum.

- Weinberg, Ian. 1967. The English Public Schools: The Sociology of Elite Education. New York: Atherton Press.

- Worth, Eve. 2019. “Women, Education and Social Mobility in Britain during the Long 1970s.” Cultural and Social History 16 (1): 67–83. doi:10.1080/14780038.2019.1574052.

- Worth, Eve. 2022. The Welfare State Generation: Women, Agency and Class in Britain since 1945. London ; New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Yanagisako, Sylvia J. 2018. “Family Firms.” P 1–7. in The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology. doi:10.1002/9781118924396.wbiea2235.

- Zanten, Agnès van. 2015. “Promoting Equality and Reproducing Privilege in Elite Educational Tracks in France.” in Elite Education. International Perspectives. London: Routledge.

- Zweigenhaft, Richard L., and G. William Domhoff. 2014. The New CEOs: Women, African American, Latino, and Asian American Leaders of Fortune 500 Companies. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

References

- Ansell, Ben W., and David J. Samuels. 2015. Inequality and Democratization: An Elite-Competition Approach. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Glenday, Nonita, and Mary Price. 1977. Clifton High School 1877-1977. Bristol: Clifton High School.

- Roedean School 1990. A History of Roedean School, 1885-1985. Roedean: Roedean School.

- Rubinstein, W. D. 1986. “Education and the Social Origins of British Élites 1880–1970.” Past and Present 112 (1): 163–207. doi:10.1093/past/112.1.163.

- Scrimgeour, R. M. 1950. The North London Collegiate School, 1850-1950: A Hundred Years of Girls’ Education. London: Oxford University Press.

- Stack, V. E. 1963. Oxford High School, Girls Public Day School Trust, 1875-1960. Oxford: Girls’ Public Day School Trust.

- Titley, E. D. 1974. Portrait of Benenden: An Anthology to Commemorate the Golden Jubilee 1924-1974. Canterbury: Elvy and Gibbs Partnership.

Web appendix

Web Appendix 1: Defining elite girls’ schools

Web Appendix 2: Women are only slightly less likely to report their education.

Web Appendix 3: Can the class composition of girls’ schools explain the difference between the propulsive power of the boys’ and the girls’ schools?

Web Appendix 4: Elite social origins for men and women

Web Appendix 5: Elite partners among those attending Oxbridge

Web Appendix 6: Elite partners among those attending and Elite School and Oxbridge

Web Appendix 1:

Defining elite girls’ schools

We define elite girls’ schools in terms of their ability to send their alumni to Oxford and Cambridge. We draw on data from Howarth (which includes information on Oxford and Cambridge matriculants) and Greenstein (Oxford matriculants only), represented in the table below. Our approach is as follows:

Was the school in Howarth’s List A for the 1891-3 data and the 1911-13 data, and was it among the top 20 schools among the sample of matriculants from Greenstein data. In other words, was the school among the most successful at every data point?

Was the school among the top performers since it was founded? This applies to St Paul’s and Benenden.

Was the school a consistently high performer – i.e., reaching List A in at least one year and being included in the Top 20 schools at Oxford – and was the proportion of your alumni attending Oxbridge greater than 0.5%.

If the answer to any of these questions was ‘yes’ then the school was included on the list.

Appendix 2:

Women are only slightly less likely to report their education

Web Appendix 3:

Can the class composition of girls’ schools explain the difference between the propulsive power of the boys’ and the girls’ schools?

One possible explanation for the difference in the propulsive power of the boys’ and the girls’ schools is that the intake of the girls schools was less privileged than the intake of the boys’ schools. If this were true, then girls’ schools might have a lower odds ratio simply by virtue of the fact that they were recruiting people who were less likely to get into the elite. In this web appendix we explore this possibility using both historical data and a simulation exercise and we argue that while a compositional effect is a possible explanation it is unlikely to fully explain our results.

First, when our list of 12 girls’ schools were first founded, they were more socially heterogeneous in their intake than the boys’ schools. However, it would also be incorrect to say that, even back then, these schools were ‘diverse’. They have always been feepaying schools for most children and while they wanted to fulfil a social mission they were also incredibly constrained by the demands on running a ‘private’ school funded by the fees of their students. For example, the North London Collegiate School ‘rejoiced in the mixture of class within the school’. But it is important to recognise what this mixture meant. The schools first prospectus was clear: ‘Daughters… of professional gentleman of limited means, clerks in public and private offices and persons engaged in trade and other pursuits’ were the intended clients (Scrimgeour Citation1950). These are all, especially in the 1850s, solidly middle-class (and potentially upper middle-class) households. They may have had ‘limited means’ but this is likely compared to the standards of the very affluent. Indeed, social tables of the period suggest these kinds of occupations would have put these individuals in the top 2 deciles of the income distribution (Ansell and Samuels Citation2015). Clifton High School was similar, aiming to recruit daughters of ‘men and women of enterprise, piety and business acumen’ and in addition to the boarders, ‘it was a regular practice for girls to live with relations in Bristol… in order to attend the school’ (Glenday and Price Citation1977). Like the elite boys’ schools then, these girls’ schools still recruited from a range of geographical areas. The parents who were attracted to Roedean were ‘mostly people of the professional middle-classes’ (Roedean School Citation1990), again a group that was by the standards of the day relatively privileged. Benenden was far more explicitly pitched at the gentry. To recruit students, they tried to glean interest and backing from elites listed in the dictionaries of the day, Such as Who’s Who but also Crockford’s Directory and Whitaker’s Almanack (Titley Citation1974). Finally, the majority of Oxford High School’s earliest students ‘were in fact “university children”’ (Stack Citation1963). In their early years them these schools may not have been as aristocratic as Eton, Harrow, and Rugby, but their students still came from privileged backgrounds. This is especially true when you consider that, according to Rubinstein (Rubinstein Citation1986), the degree to which these top boys’ schools were socially homogeneous is often over-stated.

Second, our analysis of the difference between the propulsive power of the boys’ and the girls’ schools is conducted for the contemporary period. This matters because even if these girls’ schools were more socially heterogeneous than boys’ schools in their earliest years; this is far less true since WWII. These schools are incredibly expensive to attend. St Paul’s Girls’ School costs £8629 per term (not including other costs), North London Collegiate School costs £7000 per year (again not including other costs including travel), and Oxford High School costs £5,363 per term. But these are fees for the day school. The fees are the same for St Paul’s School for Boys. Day pupils at Charterhouse pay £11,406 and at Westminster they pay £9,603. Benenden is a girls’ school with boarders and you will pay £13,616 per term to send your daughter there while you would pay £14,698 per term to send your son to Eton. Another way the girls’ schools might be cheaper is by offering more scholarships. St Paul’s Girls School has no academic scholarships but does have partial reductions for artistically and musically talented girls. North London Collegiate School offers bursaries to children for households who might be able to afford the fees (families with a total family income less than £50,000). Oxford High School offers fee reductions to academically, musically, and artistically gifted children which cover around 5% of fees per annum. Benenden offers bursaries to children who are admitted but cannot afford the fees, and which can cover 100% of the costs. The boys’ schools all offer bursaries, which provide means-tested support for children less able to pay. A small number pay no fees at all but a large share have some reduction. In other words, the girls’ schools are slightly cheaper than the equivalent boy’s schools but, if they were ever diverse in their intake, that is no longer true. This again reinforces the suitability of the comparison we make in the paper.

Third, despite this evidence in favour of the similarity of the boy’s and girls’ schools we compare in the paper, we also explore this question using a counterfactual approach. Here, we try imagine what an alternative world would need to look like in order to remove this difference in the odds ratio between the boy’s and the girls’ schools.

There are around 325 women currently in Who’s Who that attended one of these top girls’ schools and there are around 5233 women who attended some other school. To increase the odds ratio of the top girls’ schools (to bring it into line with the odds ratio for the boy’s schools) we need to change the mix of women in Who’s Who that attended one of these 12 schools. In other words, we need to move some of 5233 women who made it into Who’s Who but did not attend a top girls’ school and assign them to one of these 12 leading girls’ schools. Our estimates suggest that moving around 240 girls from one category to the other would increase the odds ratio of the girls’ school to ∼36 and therefore equalise it with the boys’ schools.

On the face of it, this may not seem like a big change. But it actually requires very substantial movements in the wider population and quite strong assumptions to bring this about.

Around 0.03% of women in the population make it into Who’s Who. This means that, on average, around 3 in every 10,000 women get admitted. By contrast, around 0.6% of women who attended one of these top private schools ended up in Who’s Who (6 in 1000 women). They are in other words, 20 times more likely to end up in Who’s Who.

Let’s assume that the women who attend these top 12 schools are not the most privileged women. That is, there is a group of women in society who are not attending these schools but who have an even higher chance of getting into the elite simply by virtue of being born into privilege.

Let’s assume for the same of argument that we can identify a set of women whose chances of getting into Who’s Who are 1 in 50 (around 2% of women in this group). This is a very high likelihood: it implies that this group are 70 times more likely to get into Who’s Who than the average person in society, much higher than we see on average for the privileged boys who attend the Clarendon schools. It also implies that this group are around 10 times more likely to get into Who’s Who than the people who are currently attending these top girls’ schools. Both of these are strong assumptions.

Our counterfactual analysis, then, examines what would happen if:

We took 1000 of the women who attended a top girls’ school (and assuming they had 6 in 1000 chance of reaching the elite) and we then assigned them to attend some other school.

If we did this then the number of women in Who’s Who from these schools would go down by 6 as a result of removing these 1000 women.

It would also increase the number of women in Who’s Who who did not go to these schools by 6.

2. We would then replace these 1000 women from top schools with 1000 women who did not attend a top girl’s school but who are part of this hyper privileged group (that is, they have a 1 in 50 chance of reaching Who’s Who).

If we did this we would increase the number of women in Who’s Who who attended these schools by 20.

Similarly, this would also decrease the number of women in Who’s Who who did not go to these schools by 20.

The total number of women in Who’s Who that attended these schools would now be 339 and the total number of women in Who’s Who that did not attend these schools would now be 5219.

The odds ratio of attending one of these top girls’ schools would be 21 instead of 20.

Of course, this counterfactual analysis assumes that the schools make no difference to these women’s probabilities of getting into the elite. This assumption makes sense because it is somewhat implied by the concern about the impact of intake on these odds ratios.

Given this set of assumptions, how big would the compositional change need to be to eradicate the difference between top boys’ and girls’ schools?