Abstract

Teacher wellbeing is a growing international concern. Despite teachers’ experiences being deleteriously impacted by education policies and organisational conditions, dominant discourses of wellbeing focus on strategies that enhance individual self-management of wellbeing. This paper critically examines teacher wellbeing and the counter-discourses of wellbeing mobilised by teachers on an online platform, Reddit. Contributors criticise the wellbeing approaches taken in their schools and education systems. They react to the erasure of how work conditions impact their wellbeing. These forums speak back to the assumption that teachers are deficient and that teachers must be positive in self-managing their wellbeing. We coin the term ‘cruel wellbeing’ to critique wellbeing programs that neglect teachers’ challenging work conditions. We question the practices of training teachers to assume responsibility for their wellbeing using strategies of positivity. We suggest that social media is an important political tool for creating and circulating counter-discourses of teachers’ work.

Introduction

Teachers’ work is increasingly complex and demanding. Across many countries, teachers are experiencing unmanageable workloads, high levels of stress and demoralisation leading to unprecedented attrition (OECD Citation2020; UNESCO Citation2022). As a result, teacher wellbeing has entered politics, education policy and workplace practices (Chapman Citation2015; McCallum and Price Citation2015), but not without criticism. The dominant discourse of wellbeing is typically normatively oriented around dominant political and social norms (Fineman Citation2006), with workplace wellbeing strategies narrowly focused on organisational needs. Such approaches foreground the enhancement of individual’s self-management of their own wellbeing (Koivunen Citation2022; Wallace Citation2022). By targeting the individual, these discourses problematically shift responsibility away from the socio-political and institutional policies, practices and conditions that constitute and shape individual wellbeing (McLeod and Wright Citation2015a). We argue that dominant discourses of wellbeing, especially those focused on being positive, do not adequately address and potentially exacerbate teacher wellbeing issues because they largely neglect the challenging work conditions that fundamentally impact on teachers’ experience of work and their mental and emotional health.

Using Foucauldian scholarship (Foucault Citation2002, Citation2007; Rose Citation1999), this paper examines the counter discourses of wellbeing mobilised by Australian teachers on the social media website Reddit. Reddit is a social media platform whereby anonymous users post predominately text-based posts and comment on these posts within moderated discussion forums (Massanari Citation2015). As with other social media, Reddit has been analysed not only as a site for sharing personal experiences, but also as a platform for counter discourses that challenge institutional power and social norms, and enable the formulation of alternative interpretations of identities, interests, and needs (Suk et al. Citation2023). In our case, the users within an Australian teacher discussion forum engaged in dialogue with one another on their personal experiences of wellbeing, the culture of toxic positivity pervading schools, and schools’ approaches to the teacher wellbeing crisis. Our analysis foregrounds the cruelty of expecting teachers to be positive and to make themselves well in difficult circumstances of others’ making, which we term ‘cruel wellbeing’. We suggest that, in socio-political environments that silence teachers’ voices from policy debates and public discussions of their work, social media can be a political tool for creating and circulating counter-discourses of teachers’ work and wellbeing. We proceed by providing some background to teacher wellbeing, the theoretical and methodological approach of the research, followed by analysis of the data and a conclusion.

Background

Teachers’ work and wellbeing

The wellbeing of teachers is a growing concern internationally. The 2018 TALIS survey (OECD Citation2020) of 260,000 teachers and 15,000 school leaders across 48 countries reported 18% of teachers experience ongoing and acute stress related to their work. While many factors impact on teachers’ working experiences, the structural working conditions of schools and education systems are a significant influence. Of those in the TALIS survey who reported workplace stress, 49% blamed excessive administrative work (OECD Citation2020), attributable, we argue, to the rise of accountability and reporting requirements associated with neoliberal policies and New Public Management (Ball Citation1987; Ball Citation2003). Neoliberal governance of the organisation of schools and teachers’ work is increasing teachers’ workload and intensifying their work, with those experiences varying between schools (Braun Citation2017; Thompson et al. Citation2019). Adding to these longer-term policy trends, the recent COVID-19 pandemic and the education sector’s responses to it have been almost universally challenging for teachers and their wellbeing (see Allen, Jerrim, and Sims Citation2020; Silva et al. Citation2020; Billaudeau et al. Citation2022). The scale and risks associated with declining teacher wellbeing, which include turnover, attrition, and burnout, has prompted the OECD to initiate a framework for data collection and analysis of teachers’ wellbeing across the world (Viac and Fraser Citation2020).

In Australia, where this study is located, many teachers are ‘at breaking point’ (Windle et al. Citation2022, 1). A survey of 2,500 Australian teachers found significant health impacts due to ongoing workplace stress, undue emotional labour, and the detrimental impact of poor work-life balance (Heffernan et al. Citation2019). This is indicative of the increasingly complex and demanding nature of the labour required to teach in schools (Fitzgerald et al. Citation2019; Gavin et al. Citation2021). Teachers find themselves juggling a ‘proliferation of top-down initiatives’ (Windle et al. Citation2022, 1) without adequate time, resources, training, and principal support (Hascher and Waber Citation2021; Heffernan et al. Citation2022). Wider social, economic, and cultural trends mean teachers are faced with responding to ‘increasingly challenging societal demands’ (Hascher and Waber Citation2021, 9), such as managing students’ complex social, behavioural and health related needs. Casualisation, overwork, emotional exhaustion and emotional labour have been impacting on the teaching profession for many years (Bellocchi Citation2019; Gardner Citation2010; Hargreaves Citation2002; Newberry et al. Citation2013). Since the pandemic, many teachers report feeling ‘overworked, burnt out and undervalued’ (Australian College of Educators Citation2021, 16).

These experiences of working conditions and their systemic effects have made teacher wellbeing ‘a serious issue’ (Carter and Andersen Citation2019, 3). For example, with poor teacher retention and difficulties attracting teachers to the profession, a teacher shortage has become endemic to many countries (Clare Citation2022; UNESCO Citation2022). In Australia across primary and secondary sectors, a staggering 59% of almost 2500 teacher respondents to a survey about their work indicated an intention to leave the profession (Heffernan et al. Citation2022). While teacher wellbeing is affected by a multiplicity of personal and external factors, working conditions feature as particularly influential in Australia and around the world.

Wellbeing as governmental and discursive object

Wellbeing has recently become prominent in the educational lexicon, however what does it mean and, more pointedly, what does it do? The term is ambiguous and has become a catch all concept to describe various aspirational qualities of personal and social life. An elasticity of meaning gives it a wide register enabling it to operate flexibly in a range of disciplines and contexts, including within education policy discourses (McLeod and Wright Citation2015a, 1), making the construct applicable to a plethora of concerns (Chapman Citation2015). Ereaut and Whiting (Citation2008, 5) astutely observe that ‘wellbeing acts like a cultural mirage: it looks like a solid construct, but when we approach it, it fragments or disappears’.

Our notion of wellbeing is that it is produced in and contributes to wider social and political processes. Taking a Foucauldian perspective (Citation1991a; Citation1991b), wellbeing exists at the power-knowledge nexus (i.e. discourse). It is an ‘invented category’ (McLeod and Wright Citation2015b, 6) that relates to ‘a larger repertoire of concepts and expertise that are mobilized – historically and in the present – to govern, organize and make sense’ of the world (McLeod and Wright Citation2015b, 2). Employed in the political and governmental assemblages of advanced liberalism and neoliberalism (Rose Citation1999), wellbeing brings the physical, social, mental, and emotional lives of individuals and populations within the sphere of government and regulatory intervention (Wallace Citation2022). Wellbeing indicators have come to render personal feelings into a public concern with individuals and groups amenable to correction and optimisation through its strategies and technologies (McLeod and Wright Citation2015a). This public concern for wellbeing is coextensive with the privatising of wellbeing as a desirable internal state of the individual. Citizens in advanced liberal countries are encouraged as a matter of their responsible and ethical self-government to know and seek to improve their wellbeing by working on their selves, their lifestyles, their relationship to their environment, and the personal conditions of their wellness. In this sense, the self-management and mastery of wellbeing have become normative obligations of advanced liberal governmentalities (Sointu Citation2005).

This regulatory apparatus of wellbeing extends to modern workplaces whereby the wellbeing of workers has featured in politically inflected aspirations throughout the twentieth century. The construct allows employers to know and manage the productive and personal characteristics and behaviours of employees (Wallace Citation2022), typified by the human relations movement and its objective to humanise work (Rose Citation1990). Aligned with prevailing neoliberal political programs and contemporary subjectivity, workplace wellbeing strategies are exercised through the self-regulation of worker autonomy and their self-optimising aspirations (Koivunen Citation2022) with the aim to engender healthy, active and ‘fit for work subjects’ (Wallace Citation2022, 20). This mode of subjectification, which we suggest seeks to avoid the putative psycho-social risks of illbeing such as negativity, dependency and passivity at work, construes wellbeing as ‘an asset to be invested in so as to ensure maximum economic return’ (Wallace Citation2022, 37). This logic around the management of employees and their wellbeing is evident in both private and public sector workplaces (Koivunen Citation2022).

The dominant discourse of wellbeing programs in schools is of responsiblised wellbeing (see Forbes Citation2017; Karnovsky et al. Citation2022; Reveley Citation2015). This privatises wellbeing by converting ‘structural circumstances into individual responsibilities, or experiences of failure into personal vulnerabilities’ (McLeod and Wright Citation2015b, 6). Responsibilization as a ‘scheme of governance’ eschews ‘mere compliance with rules’ and instead creates the conditions whereby one must care for oneself (Shamir Citation2008, 7). Stress and adversity are said to be overcome using personal cognitive, physical and emotional techniques of wellbeing enhancement (Fineman Citation2006), which includes learning to think positively, getting more sleep, having a healthy diet, exercising more, keeping a gratitude journal and being mindful, which are construed as positive practices of self-care. Teachers are expected to be individually responsible for their personal capacity to be ‘resilient’ and to ‘bounce back’ from adversity (see Ormiston, Nygaard, and Apgar Citation2022), but they are not encouraged to view wellbeing as a collective achievement closely linked to workplace conditions, policies and political-economic powers. Moreover, wellbeing strategies can too often be ‘tokenistic, reactive, or designed for organisations that are not schools’ and ‘fail to offer responsive mechanisms that support the unique needs of staff in education contexts today’ (Dabrowski Citation2020, 37). A lens of wellbeing that addresses its implicit normative, moral, and political values can render visible the wider state, policy and institutional contexts that shape the work conditions and everyday experiences of teachers and wellbeing (Acton and Glasgow Citation2015; Chapman Citation2015).

Toxic positivity and wellbeing

One approach to wellbeing draws upon positive psychology and its promotion of positive emotions and traits. The tools and concepts derived from this ‘new science of happiness’ (Miller Citation2008, 591) have been readily taken up by education institutions which has prompted criticisms from education researchers, such as Tesar and Peters (Citation2020), who view positive psychology gurus as the modern equivalent to the popular ‘snake oil’ (1118) charlatans of the past. Resistance to these discourses can be difficult because of the normativity around striving to be happy, independent, responsible, active and, in turn, more ‘well’ (Saari Citation2018). Indeed, school-based wellbeing programs are infused with ‘passion, commitment and care for the wellbeing of teachers and students’ and could be viewed as a ‘contemporary and privileged form of ‘salvation’ in neoliberal times’ (McCuaig et al. Citation2020, 233). The external providers of wellbeing tend to emphasise the ‘responsiblisation of teachers, students and parents alike’ (233). In line with this body of critical scholarship, the notion of ‘toxic positivity’ has recently entered the lexicon as a critique of positive psychology and positivity-influenced wellbeing discourses, including in organisational settings (see Cain Citation2022; Goodman Citation2022; Karnovsky et al. Citation2022).

Bastian explains that toxic positivity can be thought of as ‘happiness at all costs’ which occurs in work organisations when there is a perception that expressing or bringing to work feelings other than happiness is inappropriate (Diemar Citation2021, para. 13-14). Similarly, Karnovsky et al. (Citation2022) warn of the toxicity of positivity in schools, in which cynical, critical and pessimistic emotions and thinking are treated as disruptive and destructive. These feelings become the target of pedagogical interventions and emotional self-regulation (Binkley Citation2014) in ways that submit individuals to organisational norms and objectives.

Positivity approaches to wellbeing encourage individuals to shoulder the burden, vulnerabilities, and responsibility of wider social, economic, and political circumstances (McLeod and Wright Citation2015a). In work contexts, this avoids problematising or substantively changing the working conditions that exploit them and contribute to personal ill-being. The discussions on Reddit analysed in this article show that a discourse of positivity feeds into the ill-health of teachers because the unbridled pursuit of personal happiness and optimism encouraged by school leaders overlooks the costs to the individual of institutional practices and policies, including those that promote positivity. Later in the article we use Berlant’s (Citation2011) concept of ‘cruel optimism’ to explain how these practices and policies in schools create the conditions for teachers to view organisational wellbeing as inherently ‘cruel’.

Using social media to dissent

Teachers use social media to share their challenging professional experiences. Online websites can function ‘as a secure, informal, online space that can develop shared experiences and understandings of injustice, solidarity and collective identity’ (Thompson, McDonald, and O’Connor Citation2020, 634). Through them, teachers can find support and ‘compensate for an unsupportive or hostile school environment’ (Mercieca and Kelly Citation2018, 62). Online platforms also facilitate the formation of self-organised communities of coping, which ‘signifies an alternative, virtual means of alleviating work pressures in hostile or difficult work environments’ (2020, 634; also Bunnell Citation2018).

Online websites are also a tool for what Ball (Citation2015) calls a ‘politics of refusal’ (2015, 1141), where dominant educational discourses, policies and practices are rejected and resisted by teachers. Of course, resistance to government and organisational policies occurs within and outside of schools (Ball Citation2015), beyond the surveillance and judgment of school leaders and colleagues, such as in public protests (Thousands of NSW teachers take part 2022). But, in a policy context that has diminished teacher professional autonomy and their contribution to public debate, teachers’ dissent is common online where they can anonymously comment publicly.

This has enabled online platforms to become a powerful means to produce and circulate counter-discourses (Feltwell et al. Citation2017), including the use of Reddit to express and mobilise opposition to political and social beliefs and norms (Suk et al. Citation2023). Counter-discourse is conceived in Foucauldian terms as the practical struggle over social and political truth-making, in which ‘the voiceless begin to speak a language of their own making’ (Moussa and Scapp Citation1996, 89). Although there is a dearth of research on teachers’ political use of social media to date, we are focused on the ways teachers use social media to resist and refuse the discourses and practices of wellbeing employed in their schools and systems.

Research approach

The data in this article was gathered from the social web-based platform Reddit (Massanari Citation2015). Reddit has around 52 million daily active registered users and over 100,000 active topical communities (called subreddits). The site functions through registered members over 13 years of age who typically use a pseudonym to protect privacy. There are over 1 million subreddits, which are forums on a specific topic or idea that are user-created and user-moderated. Users can vote (‘upvote’ and ‘downvote’) other users’ content and discussion comments, with more votes making these posts and comments more visible. Voluntary moderators manage the subreddits and dictate the types of content allowed on the subreddit, remove inappropriate posts and content, and ban users. Anyone with or without a Reddit account can view content. User data indicates that 58% of users are aged between 18-34 and 57% are male. Reddit has been used in research across a range of disciplines (Proferes et al. Citation2021), with accessing, searching and collecting of data for research purposes not excluded from its user agreement.Footnote1

An article titled ‘Teachers can’t keep pretending everything is OK - toxic positivity will only make them sick’ was posted by a moderator on the r/Australia and r/AustralianTeachers subreddits in January 2022. These subreddits have 949,200 members (as of August 2022) and both are publicly available. The short article on The Conversation website argued that narrow positive-oriented wellbeing programs have become ‘toxic’ in schools. Across the two subreddits the post accumulated 242 comments, with many comments being interactions between posters. This Reddit forumFootnote2, from which we have collected data with several thousand in active daily conversation on a variety of topics. Social media sites have been documented as places for teachers to let off steam, criticise and depict their anxieties (Bunnell Citation2018), and the Australian teachers subreddit reflects this.

We were initially drawn to analyse these responses because the anonymously posted article stimulated members to share their experiences of the official discourses of wellbeing and positivity in schools, which they heavily criticised. The highlighted responses were selected as they represent concerns from existing research correlated with the primary issues Australian teachers are identifying in relation to their work; namely, that workload and wellbeing are of significant concern and causing teacher stress, demoralisation and contributing to attrition (Heffernan et al. Citation2022; Windle et al. Citation2022). The literature drawn upon in our research allowed for the identification of central themes, such as workload concerns and toxic positivity, which guided the selection of comments examined in this article. We view these comments as counter-discourse in a context where teachers in Australia are constrained by employee policies from publicly voicing potentially disparaging views and experiences about their schools and education systems via social and established media. Some studies and reports in Australia indicate there is a pervasive culture of silencing teachers around key issues that matter to them (Adoniou Citation2018).

We accessed Reddit in March 2022, using 14 comments from 10 anonymous users for deeper analysis. We selected these comments because they represented a high number of upvoted posts on the R/Australia forum (147 votes and 120 votes). These comments additionally attracted the most substantial debate, discussion and agreement within the broader forum, stimulating online conversations that included several posters with a range of attitudes towards and examples of teacher’s work. We use Foucault’s (Citation2002, 52) notion of ‘discursive practices’ as a methodological approach to data analysis. We follow Bacchi and Bonham (Citation2014, 174) assertion that discourses are ‘sets of practices’ in which an analytic framework may ‘describe those practices of knowledge formation’ with a focus on ‘how specific knowledges (discourses) operate and the work they do’. This approach to the written words of teachers in Reddit forums is useful in bridging the ‘symbolic-material’ and the political, specifically the ‘complex strategic situations involved in the production of the ‘real’’ (Bacchi and Bonham Citation2014, 174). We viewed the discourses of wellbeing on Reddit as constituting subjects and a means through which self-formation and government occurs. Hence, discourses of wellbeing incite a struggle over subjectivity, over the truths told about ‘us’, and the kind of people teachers are and can become (Ball Citation2016).

Unpacking teacher Reddit discourse is one way to understand how power operates to suppress public teachers’ voices. Heffernan et al. (Citation2022, 9) found that many Australia teachers feel ‘undervalued, under-appreciated and disrespected by the community, public and media.’ We suggest that may in part be due to the limits imposed on teachers on sharing their views and experiences in public discourse. Hence, we identify the counter discourse of teachers, specifically those teachers who speak against authoritative discourses of wellbeing. We did not seek to offer a representative sample of the topics or themes covered in the subreddit. No doubt there were many unique and overlapping comments. Rather, having come to this research knowing the official discourses, we chose posts that offered insight into counter discourses of wellbeing at the chalkface. We view Reddit as a means by which an online community, in this case predominately teachers, may ‘confirm, contest, or challenge political power and hierarchies’ (Mortensen and Neumayer Citation2021, 2367). We suggest that the Reddit forum posts we examine, constitutes an ‘everyday shared practice and engagement in politics’ that can enhance our understanding of shifting frontiers constructing ‘us’ and ‘them’ within teacher, school leader and policymaker discourse (2021, 2368).

Analysis

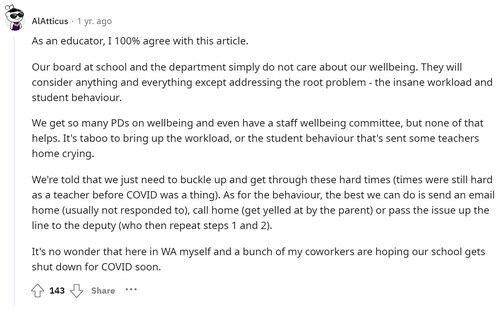

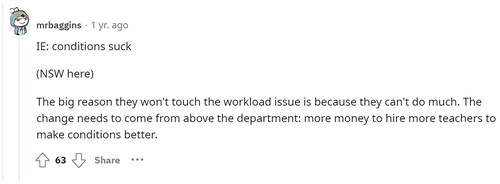

To analyse comments in the R/Australia and R/Australian Teachers subredditsFootnote3, we focused on two threads of comments from an original post made by a user (AlAtticus in thread one and Hypno—Toad in thread twoFootnote4) about the Teachers can’t keep pretending everything is OK article. The exchanges occurred within a short period of time, typically within 24 h.

Thread 1

Agreeing with the points of the article, the original poster, AlAtticus, posits the ‘insane workload’ of teachers as the ‘root problem’ of the wellbeing issue. For AlAtticus, educational authorities and actors including school boards, the school executive and policymakers ‘do not care’ about the issue of workload and in fact speaking of workload is ‘taboo’. Teachers are expected by school leaders to remain silent about workload and to simply ‘buckle up and get through these hard times’. While this silencing may not occur at all schools, AIAtticus positions teachers (who feel overworked and undervalued) against school leaders, policymakers and departmental decisionmakers. We detected multiple comments in the thread where teachers position themselves as adversaries of principals, school leaders and policymakers who are portrayed as self-serving. For example, B0ssc0 states ‘anything that furthers the admins’ career trajectories takes precedent over all others’, another user stated ‘The education system is politician centred. It is designed mainly to get certain people elected’, and Zen242 commented that ‘Be resilient’ = put up with ever worsening situations with a smile so as not to offend those making the decisions.’ The central concern for AIAtticus is that school leaders simply do not care about or understand the real challenges confronting teachers. The response of school leaders is largely constructed through dominant wellbeing discourses, which in fact worsen working conditions and teacher wellbeing.

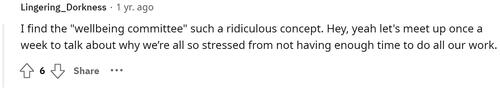

This positioning of school leaders is complex and problematic because school leaders experience similar kinds of workplace issues, such as the intensification of work and poor work-life balance. See et al. (Citation2022, 3-4) found that many Australian school leaders are stressed, have poor mental health and experience low quality of life because of long work hours, excessive quantity of work, lack of time to focus on teaching and learning, and are being subjected to offensive behaviour, threats of violence or exposed to physical violence. Importantly, this report notes that school leaders find the worsening mental health of their staff and students to be an increasing concern and cause of stress (See et al. Citation2022). Despite this, school leaders were identified by the Reddit posters as using ineffective wellbeing approaches that exacerbated wellbeing issues. The creation of school wellbeing committees, the delivery of yoga classes, and the purchasing of generic professional development and wellbeing programs are critiqued as failing to respond to the ‘real’ problems and challenges faced by teachers. For example, Lingering_Dorkness points to the ironic and ‘ridiculous’ fact that participation on school wellbeing committees takes time away from teachers, whose stretched workloads are a source of stress.

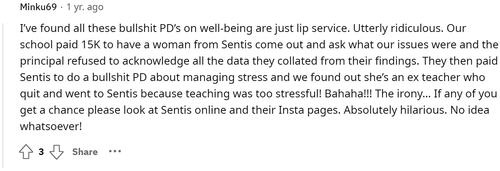

With school leadership looking to commercial entities to address the ‘wellbeing’ issues in their schools, Minku69 cites the for-profit corporate entity Sentis (Citation2023) as evidence of the move by schools to adopt slickly promoted, off-the-shelf wellbeing and resilience programs. Sentis markets itself as providing ‘solution-focused’ ‘evidence-based programs’ (2023, 3) to develop ‘optimism’ ‘engagement’ and ‘resilience’ in the workplace. Sentis’ program aims to equip workers with knowledge and skills that enable them to take ownership over and manage the personal effects of poor working conditions. Generic corporate wellbeing programs, such as Sentis, and their facilitators are derisorily portrayed, at least by some Reddit posters, as offering ‘bull shit lip service’ to schools. This form of professional development is seen by these teachers as ineffectual because it does not address the root causes of their wellbeing issues. We suggest the cynicism of the posters reflects their perception that school leaders’ approaches to teacher wellbeing are self-serving, insincere or flawed because they avoid addressing the root causes of teachers’ wellbeing issues. We take up this issue further in the next comment thread, where wellbeing programs in schools can be seen as cruel impositions on teachers who are demoralised by unreasonable working conditions.

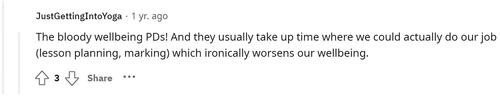

Positive psychology and the scholarship of wellness inform Sentis’ professional development material. We argue elsewhere that positivity discourse is an instrument of governmentality (Karnovsky et al. Citation2022). This discourse renders teacher wellbeing into a governable object, and one that is defined through individualising logics and practices of wellness. When construed through the logic of wellness practices, such as mindful breathing techniques, poor wellbeing becomes solely focused on the self and one’s personal mind-body management. Such an individualising approach is attractive for school leaders as these training packages, or ‘bloody wellbeing PD’s’ as JustGettingIntoYoga refers to them, offer a ‘seductive discourse’ (Fineman Citation2006, 270) where teachers are urged to improve themselves, to live a ‘happier and healthier’ life. Here, responsibility for wellbeing is devolved to teachers, and moreover, these programs offer training focused on improving one’s life, such as learning to breathe more mindfully. This goes beyond the immediate workplace pressures of teachers’ unmanageable workloads to the realm of a teachers’ intimate personal and private life. Stress that occurs through unreasonable workloads become ‘known and managed as a private issue’ with wellbeing discourses locating ‘responsibility and action inside the subject’, effectively ‘detaching any links between teachers’ emotions and the wider social structures in which they might be indelibly etched’ (Saari Citation2018, 146-150).

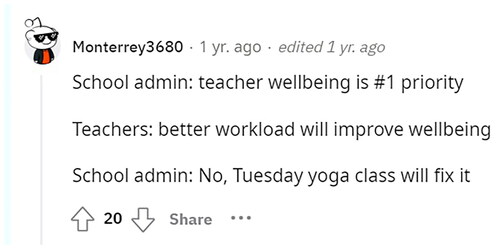

The teachers engaged in the Reddit thread make their suspicions of wellbeing programs known to one another. They are critical of corporate styled programs promising to improve employee productivity and organisational functioning by offering ‘practical solutions’ (Saari Citation2018, 141), such as learning mindfulness to resolve their problems. The posts are littered with sarcasm, cynicism and scepticism about ineffectual professional development, with one poster stating ‘just do more Self Care and Resilience Training: ^)’ followed by a Reddit shorthand use of ‘/s’ to punctuate the ironic tone of their comment. Another poster commented that school ‘PD’ is delivered by ‘shitheads who pretend they have it all figured out’, with Monterrey3680 crystalising the issue with the following post:

For mrbaggins, what is really needed is ‘more money to hire more teachers to make conditions better,’ sentiment shared by other posters like Minku69 and JustGettingIntoYoga who are likewise sceptical of the use of wellbeing programs in schools.

Through this counter-discourse teachers express their concern that wellbeing and positivity have become ‘toxic’ ideas in schools. In these teachers’ words, principals who use wellness and positivity to improve teachers’ working lives have inadvertently negatively impacted their wellbeing. This can be because the wellbeing programs and approaches being adopted are perceived as unreasonable and unrealistic for their context (see Lecompte-Van Poucke Citation2022, 8). As we introduced at the outset of the article, these approaches eschew the widely known challenges faced by teachers in schools. We suggest that positivity used in this way is a ‘type of neoliberal empowerment discourse’ that conserves the toxic institutional arrangements of schools by privatising wellbeing (Lecompte-Van Poucke Citation2022, 8). This chimes with Saari’s (Citation2018, 145) argument that ‘happiness and wellbeing’ programs resonate with neoliberal responsibilisation. These programs claim, ‘that the task of responding to conflicting demands is located within the subject’, by folding solutions into ‘one’s private interiority’ as distinct from solutions located in relational, social or governmental structures, policies and workplace practices.

The teachers engaged in the online Reddit community are speaking out against a discourse of positivity in schools. This struggle to respond to and anonymously challenge these discourses and the oppressive conditions of work they maintain is evidence of what Foucault (Citation2000, 342) has suggested is the ‘crucial problem’ of the ‘power relationship’. This problem is located upon the ‘recalcitrance of the will and the intransigence of freedom’, as ‘agonism’ which is a ‘relationship of mutual incitement and struggle’. In other words, these teachers are undergoing a ‘permanent provocation’ or ‘double bind’ of power (Ball Citation2013, 151) within this online community. Despite these teachers’ objections and derisive comments about wellbeing, they feel safe to make such utterances under the veil of anonymity. Subject to the official procedures of schools and departments of education, they struggle against this power within the safety of this online forum where their professional identities are hidden. Not sharing identifying information like name or school, their freedom of expression is circumscribed by a concern of professional harm being done by their words, or worse, their employment being put at risk because of their dissent from official discourse and criticism of the institutionally powerful. In the next section we examine a related thread of comments on these issues and highlight novel concepts to understand them.

Thread 2

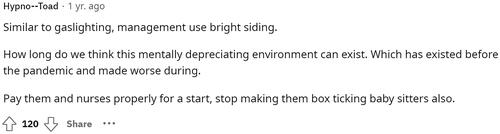

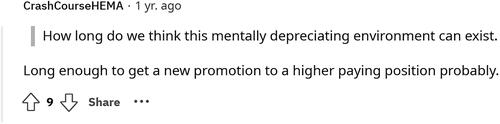

Hypno-Toad moves the discussion to the topic of ‘gaslighting’ and ‘bright-siding’. School leaders’ ignoring of the wider demands and complexities faced by teachers is construed as gaslighting, a term used to indicate the intentional unsettling of others’ reality (Sweet Citation2019). Gaslighting is meant to cause others to question their perceptions and experiences. In this instance, Hypno-Toad says management in fact use ‘brightsiding’, a neologism we take to mean portraying everything as positive, making positivity compulsory, and therefore, like gaslighting, denies teachers’ reality of the poor work conditions that contribute to their stress and vulnerabilities. It is illuminating that Hypno-Toad appears not to be a teacher, as the comment references ‘them’ (teachers) and ‘nurses’ in the context of ‘proper’ pay. Research does indeed show that teachers’ salaries have been falling behind that of other professionals for decades (Buchanan et al. Citation2020; Buchanan et al. Citation2023), with teachers earning less than the average of other professional salaries. The wider community recognise this issue as being unfair. CrashCourseHEMA’s comment points back to the line of reasoning that has been developed in the thread, that despite the ‘mentally deprecating’ environment of questioning one’s reality, school leaders are drawn to these programs for the strategic goal of self-promotion. Fletch44 then adds the term ‘dirt-siding’ to the posting as it is teachers who cop the worst of the situation. The use of these terms suggests a contest over the nature of reality between teachers and those in senior leadership positions.

We suggest that this contest, over the nature of the reality of teacher wellbeing, may be understood through Berlant’s (Citation2011) concept of ‘cruel optimism’. Specifically, we view wellbeing and positivity programs becoming toxic or a cruel kind of fantasy because they promote the idea that people can meditate, mindfully breathe or think positively as a way out of their professional stress and the effects of poor work conditions. Berlant (Citation2011, 24) describes ‘cruel optimism’ as a ‘relation of attachments to compromised conditions of possibility whose realisation is discovered either to be impossible, sheer fantasy, or too possible, and toxic’. We contend that these strategies of wellness constitute a form of cruel optimism, as Berlant theorises or as we term it, ‘cruel wellbeing’. Wellbeing programs can be a cruel undertaking in schools because, firstly, they discount the reality of teachers’ experiences of challenging work conditions as a basis of their wellbeing issues (i.e. gaslighting teachers), and secondly, striving to be more mindful and meditative is an incredibly difficult enterprise given the low trust and intense work environment of schools, as has been well documented (UNESCO Citation2022).

Koivunen (Citation2022) argues that cruel optimism exists in education because people, in our case teachers, are urged to ‘constantly work at improving themselves when they optimistically attach to things that promise fulfilment but actually perpetually defer any such fulfilment and instead end up impoverishing them’ (2022, 469). A ‘cruel paradox’ forms in a neoliberal education context, with wellbeing programs creating an ‘impossible normative narrative of success’. Wellbeing programs are littered with ‘optimistic gesticulations and solicitations’, such as keeping a gratitude journal, which ‘ultimately wear people down and lock them within the private, personal sense that it is all up to the individual to keep innovating and improving themselves optimally and persistently’ (Koivunen Citation2022, 469). We suggest that being hopeful and positive is a strategy of wellbeing that claims to be a condition of self-empowerment yet renders teachers compliant, resigned to or largely accepting of their work conditions. The teachers in this Reddit forum are speaking out about the cruel paradox of school wellbeing initiatives and refusing, at least in this online forum, their position within the prevailing discourse.

The use of language is central to this refusal. Cynicism, humour and irony are used to critique powerful decision-makers and policy trends that discount teachers’ realities of challenging working conditions. The use of novel concepts like ‘dirt-siding’, ‘bright-siding’ and ‘gas-lighting’ in the context of teacher wellbeing disrupts and carves out alternatives to the official discourse based on teachers’ knowledge and experiences. For example, their comments run counter to the official ‘quality teacher’ discourse – teachers struggle or have poor wellbeing not because of some lack of personal or professional competence; rather, they struggle because of contemporary government policies and workplace conditions and practices, which they must remain optimistic and positive about. These online comments and exchanges do not simply represent the teaching world from a different point of view, though. The forum is an intervention into this world because the posters reconfigure what constitutes the truths of what is really going on in schools, making teachers recognisable in other ways.

Building on the work of Dean (Citation2009) and Foucault (Citation2007), such discursive activities are a kind of counter-conduct ‘that seeks not to challenge or overthrow’ but, rather seeks to ‘influence the society of which they are a part’ (Dean Citation2009, 21). Evidence of this comes from the fact that the most popular comments in relation to the issue of toxic positivity in schools were posted in the r/Australia forum. Although teachers make up most of the posters on the subreddit we analysed, their posts are shared to an audience beyond those in the profession. In this way, then, we contend that the posts are an example of a particular form of counter-conduct (Foucault Citation2007)—a subtle resistance to governmental and disciplinary power. Using humour, irony, and critique of wellbeing programs, these Reddit posters problematise wellbeing to influence the broader Australian community about the ‘realities’ of teaching, thereby alerting both the game-players (teachers) and the broader Australian community to appropriate the words of Foucault (Citation2000), to the ‘type of reality with which [they] are dealing’ (2000, 327) through a ‘historical awareness’ of the present circumstance and those ‘conditions that motivate [their] conceptualisation’ (2000b, 327).

Finally, unlike the responsiblized practices encouraged by governmental self-care, we instead take a Foucauldian approach, that recognises freedom to ethically care for oneself (Foucault Citation1997a, Citation1997b) and, in turn, the wellbeing of others, should ultimately ‘be practised as resistance to that which threatens to control’ of the kinds of selves teachers seek to become (Infinito Citation2003, 158). Zembylas (Citation2005, 24) explains this practice as a ‘negotiation of subjectivity and emotion’ that can allow space for ‘self-formation and resistance’ (24). Although teachers in the Reddit forum are resisting being made subject by the ‘rule-governed discourses that govern the intelligible’ conduct of wellbeing discourses, this does not preclude the opportunity that different kinds of professional selves can emerge (Zembylas Citation2005, 31). Nor does such subjectification occur ‘in opposition’ to their professional self-formation; rather, this negotiation with discourse produces an ethical teaching self which is ‘a necessary reciprocal element of the political valorisation of freedom’ (Rose Citation1996, 98). Here, Ball (Citation2015, 1141) charts a pathway forward, explaining that teachers can engage in a ‘politics of refusal’ through a ‘renunciation of our intelligible self’—say that of the kind the modern wellbeing movement offers—and be willing to ‘test and transgress the limits of who we are able to be’.

Concluding remarks

The dominant discourse of teacher wellbeing responsiblises teachers for the self-management of their wellbeing, while largely ignoring teachers’ work conditions and the structuring effects of policy and political-economic powers. By failing to address working conditions in their approaches to wellbeing, policymakers and school leaders risk being viewed by teachers as self-interested and out of touch with the ‘real’ issues they face. More concerningly, the Reddit posters suggest that some wellbeing approaches exacerbate teacher stress, workload issues and illbeing, hence these approaches can be inherently ‘cruel’. The imposition of responsiblised wellbeing does not improve challenging workplace conditions nor address the wider political and economic contexts shaping these. The assumption that wellbeing can be achieved by each person looking internally within themselves is a cruel promise if the external conditions contributing to illbeing remain unaddressed. Indeed, this approach may contribute to the erosion of working conditions by understating its impact of teachers’ lives, leading to further demoralisation and possible attrition from the profession.

Reddit enables the voicing of counter-discourses to those promulgated by schools and education systems. The counter discourses operate via a range of mechanisms (e.g. humour and irony) as a power struggle – a rejection of forms of subjectification that posit wellbeing, positivity and resilience as solutions to the challenges teachers face in schools. On Reddit, teachers depict their work in ways counter to the wellbeing and quality teacher discourses – these teachers are stressed and overworked not because of personal or professional incompetence but due to the conditions of their work over which they have little control. This articulation of counter-discourses promotes collegial support amongst teachers as well as sharing and discussing important issues within a broader Australian community (i.e. posting to r/Australia), to find support from non-teachers. Reddit allows teachers to make their work known to others in ways often eschewed in public discourse, such as the endemic overwork of teachers and the failure of school leaders and policymakers to address the issues of most concern to teachers.

We contend that the criticisms of wellbeing approaches on Reddit builds solidarity against those who generate such imperatives, namely school leaders and policymakers. We did not detect in the Reddit forums comments of school leaders (e.g. principals) or policymakers and nor were there any advocates for the dominant wellbeing approaches. While this absence enables teachers to speak words that might arguably go unspoken in their schools or be reserved for the ears of a few trusted colleagues, it does create a stark us (teachers) versus them (leaders) mentality. We suggest school leaders’ voices need to be heard too. While school leaders are a target of the Reddit posters’ derision, humour and ire, many principals experience and struggle against similar pressures, stresses and work conditions faced by teachers (See Kidson et al. 2022). Perhaps, the wellbeing approaches and programs school leaders endorse for their schools reflect their own limited attempts, within resource constrained environments, with limited expertise and power, to address issues that are complex, institutionalised, entrenched and unlikely to be readily remedied. This is an area in need of further research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

3 https://www.reddit.com/r/australia/comments/smaswq/teachers_cant_keep_pretending_everything_is_ok/ https://www.reddit.com/r/AustralianTeachers/comments/smgczy/teachers_cant_keep_pretending_everything_is_ok/.

4 Image 1-10 unedited screenshots from https://www.reddit.com/r/australia/comments/smaswq/teachers_cant_keep_pretending_everything_is_ok/.

References

- Acton, R., and P. Glasgow. 2015. “Teacher Wellbeing in Neoliberal Contexts: A Review of the Literature.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 40 (40): 99–114. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2015v40n8.6.

- Adoniou, M. 2018. “What Happens When Teachers’ Voices Are Silenced, and We Let Others ‘Read’ the Data? A Cautionary Tale and Call to Action.” Independent Education 3 (48): 28–30. https://publications.ieu.asn.au/2018-october-ie/articles31/cautionary-tale-and-call-action/.

- Allen, R., J. Jerrim, and S. Sims. 2020. “How Did the Early Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic Affect Teacher Wellbeing?” Centre for Education Policy and Equalising Opportunities Working paper No. 20-15. https://repec-cepeo.ucl.ac.uk/cepeow/old-style/cepeowp20-15.pdf.

- Australian College of Educators. 2021. “Teachers Report Card 2021: Teachers’ Perceptions of Education and their Profession.” https://research.acer.edu.au/ace_national/5.

- Bacchi, C., and J. Bonham. 2014. “Reclaiming Discursive Practices as an Analytic Focus: Political Implications.” Foucault Studies 17: 179–192. https://doi.org/10.22439/fs.v0i17.4298.

- Ball, S. 1987. The Micro-Politics of the School: Towards a Theory of School Organization. London: Routledge.

- Ball, S. 2003. “The Teacher’s Soul and the Terrors of Performativity.” Journal of Education Policy 18 (2): 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093022000043065.

- Ball, S. 2013. Foucault, Power, and Education. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis.

- Ball, S. 2015. “Subjectivity as a Site of Struggle: Refusing Neoliberalism?” British Journal of Sociology of Education 37 (8): 1129–1146. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2015.1044072.

- Ball, S. 2016. “Neoliberal Education? Confronting the Slouching Beast.” Policy Futures in Education 14 (8): 1046–1059. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210316664259.

- Bellocchi, A. 2019. “Emotion and Teacher Education.” In Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of Education, edited by G. W. Noblit, 1–25. Oxford University Press. https://oxfordre.com/education.

- Berlant, L. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Billaudeau, N., S. Alexander, L. Magnard, S. Temam, and M. N. Vercambre. 2022. “What Levers to Promote Teachers’ Wellbeing during the COVID-19 Pandemic and beyond: Lessons Learned from a 2021 Online Study in Six Countries.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (15): 9151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159151.

- Binkley, S. 2014. Happiness as Enterprise: An Essay on Neoliberal Life. New York: SUNY Press.

- Braun, A. 2017. “Education Policy and the Intensification of Teachers’ Work: The Changing Professional Culture of Teaching in England and Implications for Social Justice.” In Policy and Inequality in Education, edited by S. Parker, K. Gulson and T. Gale, 169–185. Sydney: Springer.

- Buchanan, J., H. Curtis, S. Tierney, and R. Callus. 2020. Nsw Teachers’ Pay: How It Has Changed and How It Compares. Sydney: University of Sydney Business School.

- Buchanan, J., S. Tierney, T. Henderson, and J. Occhipinti. 2023. “From Bad to Worse to What? NSW Teachers Pay 2020- 2022 and beyond.” University of Sydney Business School, Sydney. https://www.nswtf.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/From-bad-to-worse-to-what-NSW-Teachers-Pay-2020-2022-and-beyond-Buchanan.pdf.

- Bunnell, T. 2018. “Social Media Comment on Leaders in International Schools: The Causes of Negative Comments and the Implications for Leadership Practices.” Peabody Journal of Education 93 (5): 551–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2018.1515815.

- Cain, S. 2022. Bittersweet: How Sorrow and Longing Make Us Whole. New York: Penguin.

- Carter, S., and C. Andersen. 2019. “Wellbeing in Educational Contexts.” Queensland: University of Southern Queensland Press. https://usq.pressbooks.pub/wellbeingineducationalcontexts/.

- Chapman, A. 2015. “Wellbeing and Schools: Exploring the Normative Dimensions.” In Rethinking Youth Wellbeing: Critical Perspectives, edited by J. McLeod, and K. Wright, 143–159. Melbourne: Springer.

- Clare, J. 2022. “Teacher Workforce Shortages Issues Pape.” Australian Government: Department of Education. https://ministers.education.gov.au/clare/teacher-workforce-shortages-issues-paper.

- Dabrowski, A. 2020. “Teacher Wellbeing during a Pandemic: Surviving or Thriving?” Social Education Research 2 (1): 35–40. https://doi.org/10.37256/ser.212021588.

- Dean, M. 2009. Governmentality: Power and Rule in Modern Society. 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications.

- Diemar, E.-L. 2021. “Are Your Leaders Inadvertently Creating a Toxic Positivity Culture?” Australian HR Institute. https://www.hrmonline.com.au/employee-wellbeing/toxic-positivity-workplace/.

- Ereaut, G., and R. Whiting. 2008. “What Do We Mean by ‘Wellbeing’? And Why Might it Matter?” Linguistic Landscapes. https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/8572/1/dcsf-rw073%20v2.pdf.

- Feltwell, T., J. Vines, K. Salt, M. Blyth, B. Kirman, J. Barnett, P. Brooker, and S. Lawson. 2017. “Counter-Discourse Activism on Social Media: The Case of Challenging “Poverty Porn” Television.” Computer Supported Cooperative Work: CSCW: An International Journal 26 (3): 345–385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-017-9275-z.

- Fineman, S. 2006. “On Being Positive: Concerns and Counterpoints.” Academy of Management Review 31 (2): 270–291. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20159201. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.20208680.

- Fitzgerald, S., S. McGrath-Champ, M. Stacey, R. Wilson, and M. Gavin. 2019. “Intensification of Teachers’ Work under Devolution: A ‘Tsunami’ of Paperwork.” Journal of Industrial Relations 61 (5): 613–636. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185618801396.

- Forbes, D. 2017. “Mindfulness and Neoliberal Education: Accommodation or Transformation?” In Weaving Complementary Knowledge Systems and Mindfulness to Educate a Literate Citizenry for Sustainable and Healthy Lives, edited by M. Powietrzyńska and K. Tobin, 145–158. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Foucault, M. 1975. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books.

- Foucault, M. 1991a. “Governmentality.” In The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality: With Two Lectures by and an Interview with Michel Foucault, G. Burchell, C. Gordon, and P. Miller, 87–104. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Foucault, M. 1991b. “Questions of Method.” In The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality: With Two Lectures by and an Interview with Michel Foucault, edited by G. Burchell, C. Gordon, and P. Miller, 73–86. The University of Chicago Press: Chicago.

- Foucault, M. 1997a. “On the Genealogy of Ethics: An Overview of a Work in Progress.” In Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth (Vol. One: The Essential Works of Foucault 1954-1984), edited by P. Rabinow, 253–280. New York: The New Press.

- Foucault, M. 1997b. “The Ethics of the Concern of the Self as a Practice of Freedom.” In Ethics, Subjectivity and Truth (Vol. One: The Essential Works of Foucault 1954-1984), edited by P. Rabinow, 281–301. New York: The New Press.

- Foucault, M. 2000. “The Subject and Power.” In Power: The Essential Works of Foucault 1954-1984, edited by P. Rabinow, R. Hurley Trans., 326–348. New York: New Press.

- Foucault, M. 2002. Archaeology of Knowledge: And the Discourse of Knowledge. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Foucault, M. 2007. Security, Territory, Population. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gardner, S. 2010. “Stress among Prospective Teachers: A Review of the Literature.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 35 (8): 18–28. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2010v35n8.2.

- Gavin, M., S. McGrath-Champ, R. Wilson, S. Fitzgerald, and M. Stacey. 2021. “Teacher Workload in Australia National Reports of Intensification and Its Threats to Democracy.” In New Perspectives on Education for Democracy, edited by S. Riddle, A. Heffernan, and D. Bright, 110–123. Melbourne: Routledge.

- Goodman, W. 2022. Toxic Positivity: Keeping It Real in a World Obsessed with Being Happy. New York: Penguin Random House.

- Hargreaves, A. 2002. “Teaching and Betrayal.” Teachers and Teaching 8 (3): 393–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/135406002100000521.

- Hascher, T., and J. Waber. 2021. “Teacher Well-Being: A Systematic Review of the Research Literature from the Year 2000–2019.” Educational Research Review 34: 100411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2021.100411.

- Heffernan, A., D. Bright, M. Kim, and F. Longmuir. 2019. “Perceptions of Teachers and Teaching in Australia.” Monash University. https://www.monash.edu/perceptions-of-teaching/docs/Perceptions-of-Teachers-and-Teaching-in-Australia-report-Nov-2019.pdf.

- Heffernan, A., D. Bright, M. Kim, F. Longmuir, and B. Magyar. 2022. “I Cannot Sustain the Workload and the Emotional Toll’: Reasons behind Australian Teachers’ Intentions to Leave the Profession.” Australian Journal of Education 66 (2): 196–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/00049441221086654.

- Infinito, J. 2003. “Ethical Self-Formation: A Look at the Later Foucault.” Educational Theory 53 (2): 155–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5446.2003.00155.x.

- Karnovsky, S., B. Gobby, and P. O’Brien. 2022. “A Foucauldian Ethics of Positivity in Initial Teacher Education.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 54 (14): 2504–2519. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2021.2016390.

- Koivunen, T. 2022. “Cruel Promises and Change in Work-Related Self-Help Books.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 41 (4-5): 465–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2022.2112778.

- Lecompte-Van Poucke, M. 2022. “You Got This!’: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Toxic Positivity as a Discursive Construct on Facebook.” Applied Corpus Linguistics 2 (1): 100015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acorp.2022.100015.

- Massanari, A. L. 2015. Participatory Culture, Community, and Play: Learning from Reddit. New York: Peter Lang.

- McCallum, F., and D. Price. 2015. “Nurturing Wellbeing Development in Education.” From Little Things, Big Things Grow. Melbourne: Routledge.

- McCuaig, L., L. Woolcock, M. Stylianou, J. Ng, and A. Ha. 2020. “Prophets, Pastors and Profiteering: Exploring External Providers’ Enactment of Pastoral Power in School Wellbeing Programs.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 41 (2): 223–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2020.1722425.

- McLeod, J., and K. Wright. 2015a. Rethinking Youth Wellbeing: Critical Perspectives. Melbourne: Springer.

- McLeod, J., and K. Wright. 2015b. “What Does Wellbeing Do? An Approach to Defamiliarize Keywords in Youth Studies.” Journal of Youth Studies 19 (6): 776–792. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2015.1112887.

- Mercieca, B., and N. Kelly. 2018. “Early Career Teacher Peer Support through Private Groups in Social Media.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 46 (1): 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2017.1312282.

- Miller, A. 2008. “A Critique of Positive Psychology—or ‘The New Science of Happiness.” Journal of Philosophy of Education 42 (3-4): 591–608. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9752.2008.00646.x.

- Mortensen, M., and C. Neumayer. 2021. “The Playful Politics of Memes.” Information, Communication and Society 24 (16): 2367–2377. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.1979622.

- Moussa, M., and R. Scapp. 1996. “The Practical Theorizing of Michel Foucault: Politics and Counter-Discourse.” Cultural Critique 33 (33): 87–112. https://doi.org/10.2307/1354388.

- Newberry, M., Gallant, A., Riley, P., and Pinnegar, S. (Eds.) 2013. Emotion in Schools: Understanding How the Hidden Curriculum Influences Relationships, Leadership, Teaching, and Learning. Bradford: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- OECD. 2020. “The Teachers’ Well-Being Conceptual Framework: Contributions from TALIS 2018.” Teaching in Focus 30: 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1787/86d1635c-en.

- Ormiston, H., M. Nygaard, and S. Apgar. 2022. “A Systematic Review of Secondary Traumatic Stress and Compassion Fatigue in Teachers.” School Mental Health 14 (4): 802–817. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-022-09525-2.

- Proferes, N., N. Jones, S. Gilbert, C. Fiesler, and M. Zimmer. 2021. “Studying Reddit: A Systematic Overview of Disciplines, Approaches, Methods, and Ethics.” Social Media + Society 7 (2): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211019004.

- Reveley, J. 2015. “Foucauldian Critique of Positive Education and Related Self-Technologies: Some Problems and New Directions.” Open Review of Educational Research 2 (1): 78–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/23265507.2014.996768.

- Rose, N. 1990. Governing the Soul: The Shaping of the Private Self. London: Routledge.

- Rose, N. 1996. Inventing Our Selves: Psychology, Power, and Personhood. Cambridge University Press.

- Rose, N. 1999. Powers of Freedom: Reframing Political Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Saari, A. 2018. “Emotionalities of Rule in Pedagogical Mindfulness Literature.” Journal of Management, Spirituality and Religion 15 (2): 141–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2017.1359796.

- See, S.-M., P. Kidson, H. Marsh, and T. Dicke. 2022. “The Australian Principal Occupational Health, Safety and Wellbeing Survey (IPPE Report).” Sydney: Institute for Positive Psychology and Education, Australian Catholic University. https://www.healthandwellbeing.org/reports/AU/2022_ACU_Principals_HWB_Final_Report.pdf.

- Sentis. 2023. ZIP Resilience Factsheet. https://sentis.com.au/zip-resilience.

- Shamir, R. 2008. “The Age of Responsibilization: On Market-Embedded Morality.” Economy and Society 37 (1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140701760833.

- Silva, D., R. Cobucci, S. Lima, and F. de Andrade. 2020. “Prevalence of Anxiety, Depression, and Stress among Teachers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A PRISMA-Compliant Systematic Review.” Medicine 100 (44): e27684. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000027684.

- Sointu, E. 2005. “The Rise of an Ideal: Tracing Changing Discourses of Wellbeing.” The Sociological Review 53 (2): 255–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2005.00513.x.

- Suk, J., Y. Zhang, Z. Yue, R. Wang, X. Dong, D. Yang, and R. Lian. 2023. “When the Personal Becomes Political: Unpacking the Dynamics of Social Violence and Discourses across Four Social Media Platforms.” Communication Research 50 (5): 610–632. https://doi.org/10.1177/00936502231154146.

- Sweet, P. 2019. “The Sociology of Gaslighting.” American Sociological Review 84 (5): 851–875. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419874843.

- Tesar, M., and M. A. Peters. 2020. “Heralding Ideas of Well-Being: A Philosophical Perspective.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 52 (9): 923–927. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2019.1696731.

- Thompson, P., P. McDonald, and P. O’Connor. 2019. “Employee Dissent on Social Media and Organizational Discipline.” Human Relations 73 (5): 631–652. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726719846262.

- UNESCO. 2022. “World Teachers’ Day: UNESCO Sounds the Alarm on the Global Teacher Shortage Crisis.” [Press Release]. https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/world-teachers-day-unesco-sounds-alarm-global-teacher-shortage-crisis.

- Viac, C., and P. Fraser. 2020. “Teachers’ Well-Being: A Framework for Data Collection and Analysis.” OECD Education Working Papers 213: 1–81. https://doi.org/10.1787/c36fc9d3-en.

- Wallace, J. 2022. “Making a Healthy Change: A Historical Analysis of Workplace Wellbeing.” Management & Organizational History 17 (1–2): 20–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449359.2022.2068152.

- Windle, J., A. Morrison, S. Sellar, R. Squires, J. P. Kennedy, and C. Murray. 2022. “Teachers at Breaking Point: Why Working in South Australian Schools is Getting Tougher.” University of South Australia. https://www.unisa.edu.au/contentassets/f84cdb683dbb42a09ae08abc55bd9347/teachers-at-breaking-point-full-report.pdf.

- Zembylas, M. 2005. Teaching with Emotion: A Postmodern Enactment. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.