Abstract

Being a graduate is no longer sufficient to secure a fulfilling and rewarding graduate role. This paper drew on Tomlinson’s Graduate Capital Model to analyse the job-seeking narratives of recent computing graduates searching for a graduate job. Participants (n = 38), drawn from a national placement programme, were interviewed up to 12 months after they had graduated. Narrative interviews were analysed using the five graduate capitals of the Model, providing empirical evidence of the acquisition and application of graduate capitals, in particular through experiences of student work placements. The study found strong claims of human and cultural capital, arising from placement experience, while social and identity capital acquisition was found, but to a lesser extent. Fragile psychological and identity capitals were eroded by multiple unsuccessful job applications. This work empirically tested the Graduate Capital Model, contributing to understanding of capitals and their interplay.

Introduction

The graduate outcomes and employment survey in the UK shows that unemployment rates for computing graduates remain the highest across disciplines (HESA Citation2020). The computing graduate unemployment rate 15 months after degree completion is 8%, while overall, graduate unemployment rates are 3.8%. This follows many years of analysis of similar annual returns for computing including extensive reflection in the Shadbolt Review (Shadbolt, Citation2016). The stark relative unemployment rates are in the context of consistently high levels of vacancies in the Information Technology labour market sector (ONS, Citation2020). So, the employment statistics suggest there is a gulf between what IT sector employers seem to be seeking in a graduate, and the skills and attributes of those applying for graduate employment, leaving computing graduates facing unexpected challenges in seeking work.

The relevance of the curriculum in a fast-moving discipline has long been a focus for computing departments in educational institutions, but most IT graduate recruiters are now making recruitment decisions also based on extra-curricular activity, school-level qualifications and evidence of enthusiasm/passion for technology (Target Jobs Citation2020). Having relevant work experience, for example a student work placement, can help secure a graduate role (inter alia Anderson and Tomlinson Citation2021; Divan et al. Citation2022; Silva et al. Citation2018). Indeed, there is much evidence of the importance of placements: in gaining a first graduate role and achieving good rates of pay (Di Meglio et al. Citation2019, Smith et al. Citation2018) and in graduates remaining in their career discipline (Drysdale, Frost, and Mcbeath Citation2015). As such, there are continuing calls for placements in government strategies (NCUB Citation2019; SDS Citation2023) and the press (Atherton Citation2020). While some national placement programmes exist, the notion that a placement can lead to a graduate job places considerable responsibility on universities and employers to create placement opportunities. It also places considerable responsibility on students to secure a placement, even though considerable barriers exist, not least financial barriers (Bathmaker, Ingram, and Waller Citation2013; Smith, Smith, and Caddell Citation2015), discriminatory recruitment processes (Smith et al. Citation2019b) and concerns about the exploitative nature of unpaid internships (O’Connor and Bodicoat Citation2017).

In spite of general agreement that placements benefit students when searching for their first graduate role, little is known about how graduates’ agency serves to create placement narratives and other social resources that can be accessed during the transition from university to a graduate job. In this study we used the Graduate Capital Model to reveal ways in which computing graduates recognised and accessed capitals gained on work placement in order to secure their first graduate job. The study drew participants from a national paid placement programme oriented to computing students. The aim of the study was to better understand graduate capitals, by exploring the influence of placement experiences on graduate capital acquisition, and subsequent mobilisation of graduate capitals when job seeking.

Literature review

There are many reasons that a graduate might be unable to secure a well-paid and rewarding graduate job. Unfortunately, university league table positioning based on employment data can lead to blame: levelled at the individual for failing to secure employment; and at the university for their curricula and/or lack of support (Marginson Citation2015). This deflects from underlying systemic bias in recruitment and selection practices that do not adjust for prior inequalities (Abrahams Citation2017) or institutional stratification (Brown, Hesketh, and Wiliams Citation2003; Marginson, Citation2019). Nor does reported graduate employment data take proper account of particular labour market conditions (Clarke Citation2018). Student transitions from university into graduate employment and placements have found to be smoother for people with access to certain social and financial resources (Bathmaker, Ingram, and Waller Citation2013). Bathmaker et al. use Bourdieu’s capitals to understand how such resources are mobilised in the search for graduate positions. However, graduates’ employability is not just an individual measure, rather graduates are ranked ‘within a hierarchy of job seekers’ (Brown, Hesketh, and Wiliams Citation2003, 111). In simplistic terms, university ranking and knowing the right people put you at the top of the hierarchy (Abrahams Citation2017). Relative positioning is disrupted by student work placements/relevant work experience (Hora, Parrott, and Her Citation2020; Smith et al. Citation2018), in which work placements serve to demonstrate worth, something to draw upon beyond the signalling of the worth of the university of study (Boliver Citation2015). In Bourdieu’s terms, there is evidence that capitals are afforded through work placement, with students becoming more strategic in decision-making as capitals increase (Burke Citation2015). Indeed, Tomlinson and Jackson (Citation2021) confirmed ‘the significant role that capitals play’ in shaping professional identity (897), recognising familiarity and proximity with work contexts, as afforded by relevant work experience, subsequently impacting on career trajectories. How such capitals are interwoven by students into a self-conceptualisation is not yet well understood. Some evidence exists of a utilitarian approach by students, whereby such experiences are used to improve a resumé, with no wider recognition of capitals acquired (Hora, Parrott, and Her Citation2020). Hora et al. call for further consideration of student perspectives. This study responds to that call.

Employability models

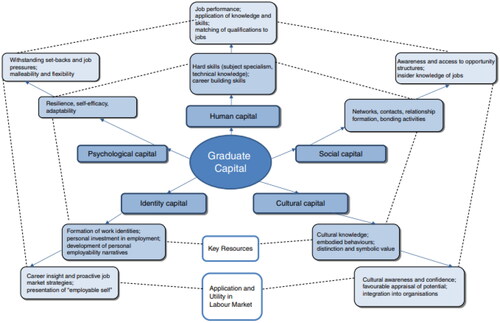

Models of employability have emerged in recent years that focus less on what a graduate can do, and more upon developing a holistic picture of who they are (for example, Holmes Citation2013; Tomlinson Citation2017). This allows for wider considerations of self, allowing for a graduate sense of self across different career trajectories, including careers in social enterprise, entrepreneurship and periods of un- and under-employment (Tomlinson Citation2010). Tomlinson (Citation2017) introduces a model of graduate capital, encompassing five capitals: human, social, cultural, identity and psychological, arguing that such a model provides a ‘vocabulary’ to support graduates’ transition into employment (339) ().

Figure 1. Forms of graduate capital, reproduced with permission (Tomlinson Citation2017).

The model extends these graduate capitals to depict both the specific resources for each capital and examples showing how they are manifested in the graduate job market to secure advantage. Tomlinson’s (Citation2017) paper summarises the ways in which each graduate capital has been approached in the research literature, and so they are only briefly outlined here. Fundamentally, the term ‘capital’ denotes something of value. In terms of graduate capital, the value inherent in the capitals encompasses the notions of employability, namely the ability to gain and retain a graduate job (Yorke Citation2006). The specific skills and knowledge acquired during study is referred to as human capital. Human Capital Theory (simply put, increased education leads to better paid jobs), is, however, increasingly contested as higher education participation levels increase (Brown, Lauder, and Cheung Citation2020). There is no guarantee that graduates pursuing ever more qualifications will obtain personally satisfying and well-paid jobs, nor has wider economic growth been experienced in spite of increasing participation in higher education in recent years (Kahn and Lundgren-Resenterra Citation2023). Thus, consideration of a wider range of capitals associated with the workplace is necessary to counter the limits of a ‘human capital theory’ lens which has been shown to have limited explanatory power. Social capital refers to social networks, including industry contacts, and can be used to both locate and secure graduate roles. Cultural capital is knowledge and awareness of cultural factors (including speech patterns and dress codes) that can help alignment with a graduate job, and with fitting in to a workplace. Identity capital is the sense of an employable self, achieved through identity work, for example, the formulation of self-narratives as a skilled member of a profession. Finally, psychological capital relates to those psychological traits that individuals can draw upon when seeking and fulfilling graduate roles, including self-efficacy and resilience.

Clarke (Citation2018) presents an Integrated Model of Graduate Employability showing human capital, social capital, individual attributes and behaviours which feed into perceived employability. This is then combined with labour market factors to form graduate employability. The Graduate Capital Model encompasses aspects of individual attributes, behaviours and to some extent perceived employability within identity capital. Where the models differ is in the external focus of Clarke’s model, with the recognition of labour market factors, which is important in the context of opportunities (or lack thereof) afforded by the labour market. The emphasis on external context recognises the futility of universities aiming to produce graduates that are ‘work-ready’, even if that were seen as desirable (Winterton and Turner Citation2019). Instead, if university experience can influence identity and psychological capital, the aim should be to transcend specific graduate roles to act to increase and protect individuals’ graduate capitals in the face of persistent challenging labour market conditions. The Integrated Model approach has led to a somewhat generic emphasis on soft skills (for example, Succi and Canovi Citation2020) and traits (Osmani et al. Citation2019).

A third model is the Graduate Identity Model proposed by Holmes (Citation2013), based on identity claims and affirmation. Identity is considered to be ‘parts of a self composed of the meanings that persons attach to the multiple roles they typically play’ (Stryker and Burke Citation2000, 284), for example student/worker roles. Work experience acts to construct a student’s pre-professional identity (an emerging understanding of a professional self) (Jackson Citation2017), and such self-identification can impact on student-to-graduate transitions (Tomlinson and Jackson Citation2021). Holmes suggests that universities create the conditions for identity affirmation as a professional, whereby the student claims a skilled identity, which can then be affirmed (or otherwise) by tutors. Work placement is an alternative location for identity affirmation. Holmes (Citation2013) calls upon universities to provide an environment wherein each student is asked to formulate their ‘claim on the identity (of being a graduate worthy of employment) in such a way that it stands a good chance of being affirmed by those who make the selection decision on job applications’ (551). Holmes’ model is reliant on both self and others, however the interplay is not fully explained and there is, as yet, little empirical evidence to support the model (Smith, Hunter, and Sobolewska Citation2019a).

Methodology

For this study, the Graduate Capital Model provided a holistic framework with a focus upon recognition and deployment of resources, within which it is possible to locate the possession and mobilisation of graduate capitals in the narratives of graduates entering their first role after completing university; to better understand how placement is used to secure graduate roles. This improved understanding, in turn, can serve to make the most out of placement for the benefit of students. It can also inform curriculum developers and student placement tutors of the significant aspects of capitals that are routinely accessed.

Following ethical approval at the authors’ organisation (ref 66031), over a period of six years, 38 graduates were interviewed (in 2017, 2019, 2022). The number of interviews required to elicit meaning (i.e. reach meaning saturation) has been found to be between 16 and 24 interviews (Hennink, Kaiser, and Marconi Citation2017) so 38 interviews represents an appropriate qualitative data sample. All graduates who volunteered to participate were interviewed. The graduates had all participated in some way with a university-led national paid placement programme during their time in Scottish further or higher education. Some participants had registered for the service but had not secured a placement, others had placement experience which was (i) paid work; (ii) no less than three months long; iii) in computing-related roles (). The 2017 interview data has previously formed part of an earlier study (Smith et al. Citation2018).

Table 1. Participants and timeframe of interviews.

The aim was to capture experiences over a 6-year time period in order to allow for changes in external factors (for example trends in job availability, changes to school and university curricula), while leveraging the longevity of the placement programme which ran between 2010 and 2023. The aim of the programme was to improve access to paid placements for all students, however the outreach work of promoting placements was predominately focused on post-1992 institutions where higher numbers of students are first in their family to attend university (Woodward Citation2019). We asked participants if their parents had attended university: for 47% one or both parents attended; for 40% neither parent attended; 13% did not answer. All interviews were conducted 6 months or more from the expected date of graduation. Using an open life narrative approach (Moen Citation2006), graduates were asked about their backgrounds, experiences of placement and their subsequent search for a graduate role. The responses to these semi-structured narrative-based interviews were then transcribed and thematic analysis was conducted, harnessing the Graduate Capital Model as a framework. This allowed key data to be categorised according to the recognition of graduate capital and situations in which the capitals were marshalled and utilised. One person coded all transcripts and a sample was coded by a second researcher to check and confirm consistency. Quotes are attributed to participants using the participant number, experience of placement (EP) or no placement experience (NP).

Findings

This section considers each of the Graduate Capitals in turn, providing experiential insights into the ways in which they are recognisable in graduates’ narratives of their experiences of job-seeking.

Human capital

Participants mentioned gaining skills and experience on placement as recognisably adding value (or capital) in relation to graduate job hunting. Graduates cited their placement impacting on their ability to express their skills in many different ways, and placement experience featured as significant evidence of competence during their graduate role recruitment and settling in phases. In terms of graduate recruitment, the placement presented a rich source of skills acquisition and examples of the application of skills. Such narratives as technically skilled workers appeared for all who had been on placement. Within the quotes, both terms placement and internship relate to a period of paid relevant work while a student. This participant expressed drawing upon their skills as follows:

This new job I got, I wouldn’t have got if it wasn’t for my internship I would say because some of the questions they asked me were based on my previous experience and technically every example I gave was from my internship. (P19, EP)

Participants mentioned that placement employers had lower expectations of human capital than graduate employers, with recognition of having been given time and space to develop new skills while on placement, for example:

I feel as a student… I’m not expected to know everything I’m here to learn and people are very open and keen to help you learn and support you. (P20, EP), and, It was a nice step by step progression … rather than just being thrown in the deep end (P19, EP).

Participants with multiple experiences of placement recognised an accumulation of experience and skills:

My placements have all been invaluable in their own ways and I’ve got a lot out of each one. I can pretty much guarantee that if I hadn’t done some of my placements, I wouldn’t be in the [graduate] job (P31, EP).

It was a lot different because… you’re working with so many new technologies. Every company has their own processes that you’re working with…Even if you’ve got experience, and you go to a new company you’ve got to then learn and understand how they work (P19, EP).

Weighing up human capital in terms of cost/benefits of applying for both placement and graduate roles was in evidence, for example, making multiple applications distracted from degree study. Excessive time spent on applications increased the risk of a negative impact on future human capital. For example, one participant wanted to focus on studying:

I found it quite hard to also do applications. Because you’re still in the frying pan of your dissertation, you’re still doing all the other stuff (P30, EP).

It took me so much energy, so I decided just after I had like 3 unsuccessful interviews, OK, let’s focus on dissertation first and [apply] after (P31, EP).

Social capital

Participants were invited to share aspects of social capital, through questions utilising terms such as ‘networking’ and ‘keeping in touch’. Academic staff and placement coordinators were mentioned positively by many participants. Their social capital value included: offering advice on placements and graduate work; making introductions to organisations that might offer placements/graduate jobs; and finding paid student work or student projects, that in turn led to placements. While there were examples where participants had recognised the social capital value of wider, non-university contacts, this was certainly not universal across participants.

In terms of acquiring social capital during placement, participants cited benefits including now knowing people in the technology sector as a result of placement, and referred to both direct and indirect benefits. While some referred to their contacts in an instrumental perfunctory way, for example, sending the occasional message, others offered more concrete examples, such as ‘They said that if you’re looking for something after uni, just let us know’ (P19, EP).

Workplace mentors were mentioned as role models providing useful advice, and an additional source of skills affirmation and acquisition. One participant mentioned a tech mentoring programme where they ‘met so many nice contacts’ (P31, EP).

The value of social capital reached beyond the work/organisational context, for example asking advice for a new venture and gaining feedback on assessed work. The experiences of networking also extended to interactions with external clients, and such encounters could also be a source of cultural capital, learning the symbols from those clients as well as internally. Social capital was seen to have potential benefits in the future, for example, asked how they might pitch the benefits of placement to students, one participant said:

[Placement] puts you in a position where you …can network. When you do get the placement, network (P20, EP)

I have a family member in the industry, so it was kind of a case of asking directly to see if they had any work, so it was quite an informal [application] process for that first one (P32, EP).

Cultural capital

Cultural capital includes symbols (such as speech, gestures and dress) adopted by a group that, when acquired, can help with cultural fit. Many participants mentioned technical terms and workplace technology that were commonly used, and ways of working that they had observed while on placement, that in turn helped them express their value to their employing organisation during recruitment and while transitioning into a graduate role. Indeed, familiarity with workplace terminology could be used to secure a graduate role, as described by these participants:

Actually my placement is why I got a job. Or at least it’s definitely why I started at a senior analyst level rather than an analyst level because in my interview I could talk about enterprise culture in a way that they were very much looking for (P6, EP), and

I learned what employers are looking for and it also helped me when I was attending interviews for other jobs in the future (P1, EP).

Fitting in was also seen as advantageous by this participant:

[Work placement] teaches you how to work with other people, it teaches you how to work in a team, how to negotiate, how to appreciate other people’s requirements, and how you can help them (P16, NP).

There was also recognition of the value of cultural capital by those unsuccessful in obtaining a placement, for example, offering advice to future students to try to ‘understand other cultures for rules and regulations; people will like it’ (P25, NP).

Identity capital

Responses relating to identity in the main focused on participants’ sense of belonging to a work community and self-identification as professional/highly skilled. Belonging was mentioned, for example, feeling a part of a team. Over time, belonging increased: ‘So like the feeling of belonging, I’d say over time it does get a bit stronger’ (P28, EP). Some participants were aware of identity capital, for example “It feels like you always have to be professional, but you can still be yourself” (P19,EP). One participant remarked: ‘I can imagine myself not doing the placement and being kind of lost’ (P19, EP).

Placement was a source of identity work (a turning point), for example:

It felt like a turning point in my life where I finally wouldn’t have to be paid for doing random work in a kitchen. I was getting paid for something that I’ve trained up for and actually has some relevance to my degree (P18, EP).

The following participant demonstrates a productive intersection of human, identity and social capitals when reflecting on the benefits of placement in terms of future applications:

…people can see who you are and your skills and even if you don’t get that [permanent] job there’s still someone there who can give you a good reference because they’ve seen what you can do and they might be able to point you to another company or another place (P20, EP).

Psychological capital

Psychological capital emerged through participants’ narratives. The safety net of university was referred to by participants and the sense of being in a bubble, protected for now from the outside world, within something of a comfort zone. However, this in turn presents a perspective of graduate employment being less safe, less protected. Participants who were successful in their applications for work placement, had all gained psychological capital associated with increased self-confidence and self-efficacy related to being in the tech sector. In the main this was expressed in the form of confidence and reassurance, as these participants describe:

[Placement]’s a great opportunity I think to sort of reassure yourself and show what you’ve been studying and learned and that you can apply those skills to the workplace (P18, EP), and

[Placement] gives you great advantage because you feel so much more confident when you apply for jobs (P4, EP).

It just gives you an edge over other people that haven’t decided to do an internship and you’ll perform better in interviews and come up with ideas and solutions (P19, EP), and

It puts you in a stronger position above other classmates. After the placement, university was a lot easier to deal with (P23, EP).

I would say I’m more pushy [after placement] I guess. There would be jobs I would see and I’m like ‘I don’t think I can do it’ but my time at university has definitely helped me be like ‘apply for it I know I can do it’ (P19, EP).

Imposter syndrome really sinks in when you start doing your first job, but you get over that by being able to do what it is you’re kind of feeling like an imposter of. And getting the feedback from people around me helps a lot…They’re giving you the positive feedback you need. (P28, EP).

When you get a lot of rejections unfortunately then it also demotivates you and, in this course, demotivation was the last thing I was looking for (P29, NP).

Sending off over 100 unsuccessful applications took its toll on psychological capital:

The one thing that really got me down was the constant null and the rejections… it’s definitely a time where I was probably at my lowest emotion-wise - I had to just leave someone else to choose whether I was worthy of the job. (P38, EP)

In an industry sector with purportedly an acute skills gap, participants who had had placement experience still needed resilience when searching for a graduate role. Most had applied for multiple roles, not securing interviews. Some had temporarily suspended searching to focus on their studies. Advice was offered to future students:

Try to get as many interviews as possible. Even if they’re horrible ones. Just go for it and you’ll be more confident. The first one is always scary but you can have ten good ones and the eleventh is horrible and if you are there with a negative attitude then it’s not going to work. (P21, EP).

Discussion

Universities have a mission to maximise opportunities for fulfilling graduate work on completion of study, but also to facilitate the development of students’ individual self-narratives that leave room for resilience in the face of setbacks, including labour market conditions where applicant demand for graduate roles outstrips supply. As such, new models for graduate employment, beyond assumptions that the degree itself will suffice, can help create a better understanding of the ways students approach an intensely competitive graduate labour market. This enables universities to reframe their contribution (Anderson and Tomlinson Citation2021; Bridgstock et al. Citation2019), through recognising and challenging unequal access to graduate roles in ways that acknowledge agency and constraints (Kahn and Lundgren-Resenterra Citation2023). A greater appreciation of the acquisition and mobilisation of graduate capitals can demonstrate to employers their applicants’ human, cultural, social, psychological and identity resources that could form the basis of a rewarding graduate career. The graduates participating in this study gave evidence of ways in which placement had afforded opportunities for capital acquisition and how such capitals could be surfaced through the process of graduate job seeking. Three themes emerged across the five capitals: the notion of gaining competitive advantage; complex intersections of capitals; and erosion of capitals brought about by unsuccessful job and placement applications.

‘Having an edge’

The competitive nature of graduate employment was reinforced through the graduate narratives, whereby students that had had placement were now graduates with an advantage over those who did not have relevant work placement experience. This ‘edge’ was raised as a signifier across all five graduate capitals (see findings for both explicit and implicit examples, including Participant 23). Similarly, Gleeson et al. (Citation2022) identified ‘positional leverage’ (8) in their study based on graduate capitals. This self-identification as someone with additional resources is a form of identity work, showing compliance with role requirements (Ibarra and Petriglieri Citation2010). The self-narratives based on having an edge, had based this advantage on the fact that they could demonstrate compliance in a future setting such as an interview or graduate role, based on their placement experience. An emergent professional identity linked to relevant work experience has been observed elsewhere (for example, Jackson et al. Citation2017). In this study graduates with work experience had developed a sense of themselves at work, as professionals with technical skills. Elsewhere, others have called for universities ‘to improve resources, challenges and support related to the awareness of graduate identity and self-perception of employability’ (Griffiths et al. Citation2018, 891). Capitals acquisition through work placement was an iterative process, including across placements and project work. For example, identity capital acquired through placement was accessed on return to study and during graduate recruitment. A longitudinal approach to graduate capital acquisition throughout university could give students time and opportunity to accumulate capitals.

However, trying to gain this ‘edge’ had its costs, including the length of time taken by participants to apply for placement roles, and the impact of consequent demotivation and demoralisation felt when applications were unsuccessful. Participants reported placement being used to gain and leverage graduate capitals, however this reveals inequalities, in particular unequal access to paid work placements. Work placement experience increased cultural capital, and an improved understanding of the rules of the game (Bathmaker, Ingram, and Waller Citation2013). However, some participants faced additional barriers and had, as a result, given up searching for placement to focus on their studies. Such barriers have been reported elsewhere, for example: international students (Smith et al. Citation2019b), disability status (Divan et al. Citation2022) and those from lower socio-economic groups (Allen et al. Citation2013) revealing inequality of access to placement. Employers and universities should focus on increasing access to placement and graduate roles to mitigate against socio-cultural inequity and disadvantage. For example, where careers services are aware that employers are shortlisting based on school-level qualifications or using adverts with inherent bias, they should not promote such roles, explaining why.

Wider work-integrated learning approaches, easier to access than employer-led paid placements, somewhat mitigate the risk of disappointment (Jackson et al. Citation2017). Finding additional alternative ways of acquiring graduate capitals (industry-led/inspired group projects, industry mentoring, alumni talks etc), could encourage wider participation, making explicit how this so-called ‘edge’ might be secured, for example through the process of structured reflection (Dunne Citation2019; Hora, Parrott, and Her Citation2020). For example, few participants recognised and subsequently leveraged placement as an opportunity to develop an advantageous social network. This was likely due to socio-cultural factors. Many were first in their families to attend university, with fewer resources to engage in reflexivity (Archer Citation2007), to ‘play the game’ of securing graduate employment. Subject discipline could also be a factor (Milosz Citation2014) or geographical location. Graduate capital acquisition should therefore be explored more fully across different socio-economic groups, disciplines and universities. Advantages of (and techniques for) building social capital through placement could be better signposted during preparation sessions for placement, together with specific discipline- informed approaches.

Pitting students against each other by using ‘having an edge’ terminology, commonly used by universities to promote placements, is designed to encourage participation. Perhaps a promotional campaign based on ‘get to know your worth’ might instead encourage students to apply, certainly more accessible than suggesting placement will ‘increase your graduate capital’. We cannot ignore the ‘edge’ that those with home-acquired social and cultural capital studying at ‘elite’ institutions already enjoy. Based on the experiences of participants in this study, we argue that work placement can act to level the playing field. An overly optimistic message (so-called cruel optimism (Berlant Citation2011)) based on securing a placement guaranteeing a graduate role could lead to incorrectly directed self-blame.

Re-shaping this ‘edge’ or sense of advantage as an internalisation of a valuable self can be useful, even without the graduate role, as an aspect of psychological capital. Such intersections lead to the second theme to emerge from the study: narratives revealing overlapping and co-dependent capitals.

Intersectionality of capitals

The narratives showing how graduate capitals had been recognised and mobilised in the pursuit of a graduate job demonstrated, at times, a complex intersectionality. For example, human capital described as key technical skills had to be adapted to fit in with a new working environment, thus access to cultural capital derived from a placement experience had to be re-acquired in a new setting (e.g. ‘every company has its own processes’, Participant 19). A further example highlighted the intersection of who you are (identity capital) and your pride in technical skills (human capital), whereby graduates gained professional identity capital as a result of applying their skills and gaining affirmation of self as a competent professional during work placement (e.g. ‘people can see who you are and your skills’, Participant 20).

In this study, workplace mentors were identified as valuable social capital, especially when formally identified as such. Significant interactions included careers advice to progress in the future and new technology to consider, enhancing cultural capital. Mentors can be a useful resource for identity reconstruction (for example, Atkins et al. Citation2020). This echoes Tomlinson and Jackson (Citation2021) finding that identity construction is mediated by social and cultural capital – impacting on students’ sense of belonging or association with an industry sector or profession. Social capital, in the form of academics and placement coordinators, was found to be a source of identity affirmation, as theorised by Holmes (Citation2013), leading to self-identification as recognised competent workers. For both placed and non-placed students, social processes of joining a team provided an opportunity for sensemaking leading to identity reconstruction (Ashforth, Harrison, and Sluss Citation2018), also providing social capital, human capital (though learning from team members) and cultural capital through emerging team culture. Furthermore cultural capital gained on placement affected identity capital through an emerging sense of self, based on access to accepted norms of the work group. The relatively safe space of a student placement created an opportunity for ‘identity-in-practice’ (Gazley et al. Citation2014, 1023). To be a resource for identity reconstruction, Gazely et al. found access to cultural capital had to be combined with knowledge of the context in which it could be deployed. Placement-experienced participants in the current study leveraged both social and cultural capital acquired on placement to construct self-narratives as technically-capable workers: making a contribution, fitting in.

While such examples of dependencies and positive intersections are unsurprising, this lends further complexity to our understanding of how placement acts to support the transition to a graduate job and, more importantly, to the understanding of how universities can best serve both students who go on placement, and those who are unable to go on placement. For example, work-integrated learning, such as a group project designed to work on a client brief, can be a reasonable approximation of work placement but students may be unaware of how such a project could be used as a source for resources impacting graduate capitals.

A disentangling of capitals through understanding and self-awareness could help students extract meaning and value from work and study. And additionally provide a means to fully exploit a single experience reflecting multi-faceted perspectives of graduate capitals.

Erosion of capitals: the effort of applying and the fear of rejection

The findings revealed worrying levels of erosion of psychological and identity capitals, for example self-confidence, self-efficacy and identity as a competent worker. For example, imposter syndrome on placement represented low self-confidence, as has been found for under-represented groups (Bowen et al. Citation2023). This erosion was particularly visible when graduates tried to persist in seeking a satisfying career. Such disappointments precipitated graduates in this study accepting the first job offered (not always at graduate level) or continuing post-graduation with part-time employment secured while still a student. Sellar and Zipin (Citation2019) suggest that a focus on acquiring psychological capital is ‘forestalling’ anxiety about future precarious work and downwards mobility, in the face of insufficient graduate roles and wider concerns about the reliability of Human Capital Theory (Brown, Lauder, and Cheung Citation2020). Participants had tried and sometimes failed to secure a graduate role, creating narratives about computing ‘not being for me’ or making the most of part-time/non-graduate work in the face of disappointment. Such disillusionment has been found elsewhere (for example, Chesters and Wyn Citation2019) and represents a disaffirmation of identity as a capable technically-skilled graduate (Smith, Hunter, and Sobolewska Citation2019a).

The application processes described by the participants in this study were time-consuming, humiliating, demotivating and none of the participants had benefited from feedback following unsuccessful applications.

To mitigate against erosion of psychological capital, universities should encourage employers to reconsider their recruitment processes (for both placements and graduate roles). What do their processes say to students about their organisation’s values, and about the low value they may be placing on students’ and graduates’ time and wellbeing? Applicants should obtain some constructive feedback; even an acknowledgement of their application would be an improvement on the experience for many. Along with transactional CV surgeries, university careers teams should still encourage students ‘to look forward to being in the world’ (Berlant Citation2011, 24).

Conclusion, limitations and future work

In this study, experience of work placement was found to be effective in increasing graduate capitals and mobilising them in search of a graduate career. A picture of dynamic graduate capital acquisition and loss emerged from this study. Graduate capitals were accumulated during successful work placements, with intersections magnifying gains. Students somewhat underplayed recognition of, and access to, graduate capitals; this was particularly true of social capital. Capital erosion was reported during placement and graduate job recruitment cycles, prompting a reconsideration of next steps for the individual. Where placements can be offered, students should be encouraged to frame their experiences according to graduate capitals in order to build their self-concepts before approaching the labour market as graduates. We echo others in asking for universities to continue seeking paid work placement opportunities for students to provide meaningful contexts in which such holistic framing of self-concept can be experienced consciously, in particular for those who would benefit most i.e. with less prior social and cultural capital. Where this is not possible, thinking creatively about approaches that might serve as rich alternatives is recommended. In an increasingly competitive graduate labour market, some wider experiences and reflection could help shape positive next steps for individuals. Further work is necessary into how universities can provide environments and support with a view to identifying and filling any gaps in graduate capitals beyond any support for work placements. There are always situations and sectors where placements are not possible either from student choice or necessity, or where suitable (paid) employment is not available. A consideration of graduate capitals has the potential to transcend the transactional view currently dominant in higher education that a degree plus ‘employability’ should lead to a graduate career (with meaning for the graduate). This study confirmed the emergent value of the Graduate Capitals model to capture, frame and understand the transformative nature of work experience. The strength of the approach is finding value not just in becoming a graduate but in acquiring, recognising and mobilising graduate capitals that can sustain a sense of self beyond graduation.

The main limitation of this study is the focus on a single discipline, especially one with an associated industry-sector. A study of graduates from different subject areas, especially studying subjects that are less closely aligned to a vocation is recommended. A graduate capitals study revealing the influence of social economic status, gender, disability, university status and other factors associated with labour market barriers is essential.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Ella Taylor-Smith, Emily Bell, Stuart Anderson and Tatiana Tungli for their contribution to data collection. The authors are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive criticism, which greatly enhanced the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abrahams, J. 2017. “Honourable Mobility or Shameless Entitlement? Habitus and Graduate Employment.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 38 (5): 625–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2015.1131145.

- Allen, K., J. Quinn, S. Hollingworth, and A. Rose. 2013. “Becoming Employable Students and ‘Ideal’ Creative Workers: Exclusion and Inequality in Higher Education Work Placements.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 34 (3): 431–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2012.714249.

- Anderson, V., and M. Tomlinson. 2021. “Signaling Standout Graduate Employability: The Employer Perspective.” Human Resource Management Journal 31 (3): 675–693. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12334.

- Archer, M. S. 2007. Making Our Way through the World: Human Reflexivity and Social Mobility. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Ashforth, B. E., S. H. Harrison, and D. M. Sluss. 2018. “Becoming: The Interaction of Socialization and Identity in Organizations over Time.” In Time and work, Vol. 1. How time impacts individuals, edited by A. J. Shipp andY. Fried, 11–39. Psychology Press.

- Atherton, G. 2020. Securing great outcomes for students means focusing on students, not courses. Accessed December 07, 2023. https://wonkhe.com/blogs/securing-great-outcomes-for-students-means-focusing-on-students-not-courses/.

- Atkins, K., B. M. Dougan, M. S. Dromgold-Sermen, H. Potter, V. Sathy, and A. T. Panter. 2020. “Looking at Myself in the Future”: How Mentoring Shapes Scientific Identity for STEM Students from Underrepresented Groups.” International Journal of STEM Education 7 (1): 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-020-00242-3.

- Bathmaker, A. M., N. Ingram, and R. Waller. 2013. “Higher Education, Social Class and the Mobilisation of Capitals: Recognising and Playing the Game.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 34 (5-6): 723–743. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2013.816041.

- Berlant, L. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Boliver, V. 2015. “Are There Distinctive Clusters of Higher and Lower Status Universities in the UK?” Oxford Review of Education 41 (5): 608–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2015.1082905.

- Bowen, T., M. Drysdale, S. Callaghan, S. Smith, K. Johansson, C. F. Smith, B. Walsh, and T. Berg. 2023. “Disparities in Work-Integrated Learning Experiences for Students Who Present as Women: An International Study of Biases, Barriers, and Challenges.” Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning. In press. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-05-2023-0115.

- Bridgstock, R., M. Grant-Iramu, C. Bilsland, M. Tofa, K. Lloyd, and D. Jackson. 2019. “Going beyond “Getting a Job”: Graduates’ Narratives and Lived Experiences of Employability and Their Career Development.” In Education for Employability II: Learning for Future Possibilities, edited by J. Higgs, W. Letts and G. Crisp. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense-Brill.

- Brown, P., A. Hesketh, and S. Wiliams. 2003. “Employability in a Knowledge-Driven Economy.” Journal of Education and Work 16 (2): 107–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/1363908032000070648.

- Brown, P., H. Lauder, and S. Y. Cheung. 2020. The Death of Human Capital? Its Failed Promise and How to Renew It in an Age of Disruption. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Burke, C. 2015. “Habitus and Graduate Employment: A Re/Structured Structure and the Role of Biographical Research.” In Bourdieu, Habitus and Social Research: The Art of Application, edited by C. Costa and M. Murphy, 55–74. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Chesters, J., and J. Wyn. 2019. “Chasing Rainbows: How Many Educational Qualifications Do Young People Need to Acquire Meaningful, Ongoing Work?” Journal of Sociology 55 (4): 670–688. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783319888285.

- Clarke, M. 2018. “Rethinking Graduate Employability: The Role of Capital, Individual Attributes and Context.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (11): 1923–1937. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1294152.

- Di Meglio, G., A. Barge-Gil, E. Camiña, and L. Moreno. 2019. Knocking on Employment’s Door: Internships and Job Attainment. MPRA Paper No. 95712.

- Divan, A., C. Pitts, K. Watkins, S. J. McBurney, T. Goodall, Z. G. Koutsopoulou, and J. Balfour. 2022. “Inequity in Work Placement Year Opportunities and Graduate Employment Outcomes: A Data Analytics Approach.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 46 (7): 869–883. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2021.2020220.

- Drysdale, M. T., N. Frost, and M. L. Mcbeath. 2015. “How Often Do They Change Their Minds and Does Work-Integrated Learning Play a Role? An Examination of" Major Changers” and Career Certainty in Higher Education.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education 16 (2): 145–152.

- Dunne, J. 2019. “Improved Levels of Critical Reflection in Pharmacy Technician Student Work-Placement Assessments through Emphasising Graduate Attributes.” Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability 10 (2): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.21153/jtlge2019vol10no2art637.

- Gazley, J. L., R. Remich, M. E. Naffziger‐Hirsch, J. Keller, P. B. Campbell, and R. McGee. 2014. “Beyond Preparation: Identity, Cultural Capital, and Readiness for Graduate School in the Biomedical Sciences.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 51 (8): 1021–1048. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21164.

- Gleeson, J., R. Black, A. Keddie, and C. Charles. 2022. “Graduate Capitals and Employability: Insights from an Australian University co-Curricular Scholarship Program.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 32 (2): 341–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2022.2038251.

- Griffiths, D. A., M. Inman, H. Rojas, and K. Williams. 2018. “Transitioning Student Identity and Sense of Place: Future Possibilities for Assessment and Development of Student Employability Skills.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (5): 891–913. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1439719.

- Hennink, M. M., B. N. Kaiser, and V. C. Marconi. 2017. “Code Saturation versus Meaning Saturation: How Many Interviews Are Enough?” Qualitative Health Research 27 (4): 591–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316665344.

- HESA. 2020. Graduate Outcomes by subject area of degree and activity. Accessed December 08, 2022. https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/sb257/figure-10.

- Holmes, L. 2013. “Competing Perspectives on Graduate Employability: Possession, Position or Process?” Studies in Higher Education 38 (4): 538–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.587140.

- Hora, M. T., E. Parrott, and P. Her. 2020. “How Do Students Conceptualise the College Internship Experience? Towards a Student-Centred Approach to Designing and Implementing Internships.” Journal of Education and Work 33 (1): 48–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2019.1708869.

- Ibarra, H., and J. L. Petriglieri. 2010. Identity Work and Play. Journal of Organizational Change Management 23 (1): 10–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534811011017180.

- Jackson, D. 2017. “Developing pre-Professional Identity in Undergraduates through Work-Integrated Learning.” Higher Education 74 (5): 833–853. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0080-2.

- Jackson, D., D. Rowbottom, S. Ferns, and D. McLaren. 2017. “Employer Understanding of Work-Integrated Learning and the Challenges of Engaging in Work Placement Opportunities.” Studies in Continuing Education 39 (1): 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2016.1228624.

- Kahn, P., and M. Lundgren-Resenterra. 2023. “Grounding Employability in Both Agency and Collective Identity: An Emancipatory Agenda for Higher Education.” In Rethinking Graduate Employability in Context, edited by Siivonen, P., U. Isopahkala-Bouret, M.Tomlinson, M. Korhonen and N. Haltia. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-20653-5_6.

- Marginson, Simon. 2019. “Limitations of Human Capital Theory.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (2): 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1359823.

- Marginson, S. 2015. December. Rethinking education, work and ‘employability’ Foundational problems of human capital theory. In Keynote address to Society for Research in Higher Education conference (Vol. 9).

- Milosz, M. 2014. “Social Competencies of Graduates in Computer Science from the Employer Perspective–Study Results.” In ICERI2014 Proceedings, 1666–1672, Seville, Spain: IATED.

- Moen, T. 2006. “Reflections on the Narrative Research Approach.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5 (4): 56–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500405.

- NCUB. 2019. State of the Relationship Report. National Centre for Universities and Business State of the Relationship Report National Centre for Universities & Business (ncub.co.uk).

- O’Connor, H., and M. Bodicoat. 2017. “Exploitation or Opportunity? Student Perceptions of Internships in Enhancing Employability Skills.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 38 (4): 435–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2015.1113855.

- ONS. 2020. Office for National Statistics. Accessed December 08, 2022. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peoplenotinwork/unemployment/datasets/vacanciesbyindustryvacs02.

- Osmani, M., V. Weerakkody, N. Hindi, and T. Eldabi. 2019. “Graduates Employability Skills: A Review of Literature against Market Demand.” Journal of Education for Business 94 (7): 423–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2018.1545629.

- SDS. 2023. Digital Economy Skills Action Plan. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://www.skillsdevelopmentscotland.co.uk/media/50035/digital-economy-skills-action-plan.pdf.

- Sellar, S., and L. Zipin. 2019. “Conjuring Optimism in Dark Times: Education, Affect and Human Capital.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 51 (6): 572–586. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2018.1485566.

- Shadbolt, Nigel. 2016. Review of computer sciences degree accreditation and graduate employability. BIS.

- Silva, P., B. Lopes, M. Costa, A. I. Melo, G. P. Dias, E. Brito, and D. Seabra. 2018. “The Million-Dollar Question: Can Internships Boost Employment?” Studies in Higher Education 43 (1): 2–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1144181.

- Smith, S., D. Hunter, and E. Sobolewska. 2019a. “Getting in, Getting on: Fragility in Student and Graduate Identity.” Higher Education Research & Development 38 (5): 1046–1060. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1612857.

- Smith, S., C. Smith, and M. Caddell. 2015. “Can Pay, Should Pay? Exploring Employer and Student Perceptions of Paid and Unpaid Placements.” Active Learning in Higher Education 16 (2): 149–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787415574049.

- Smith, Sally, Ella Taylor-Smith, Liz Bacon, and Lachlan Mackinnon. 2019b. “Equality of Opportunity for Work Experience? Computing Students at Two UK Universities “Play the Game.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 40 (3): 324–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2018.1489219.

- Smith, S., E. Taylor-Smith, C. Smith, and G. Webster. 2018. “The Impact of Work Placement on Graduate Employment in Computing: Outcomes from a UK-Based Study.” International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning 19 (4): 359–369.

- Stryker, S., and P. J. Burke. 2000. “The past, Present, and Future of an Identity Theory.” Social Psychology Quarterly 63 (4): 284–297. https://doi.org/10.2307/2695840.

- Succi, C., and M. Canovi. 2020. “Soft Skills to Enhance Graduate Employability: Comparing Students and Employers’ Perceptions.” Studies in Higher Education 45 (9): 1834–1847. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1585420.

- Target Jobs. 2020. Accessed Decmber 08, 2022. https://targetjobs.co.uk/career-sectors/it-and-technology/323039-why-your-computer-science-degree-wont-get-you-an-it-job.

- Tomlinson, M. 2010. “Investing in the Self: Structure, Agency and Identity in Graduates’ Employability.” Education, Knowledge & Economy 4 (2): 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/17496896.2010.499273.

- Tomlinson, M. 2017. “Forms of Graduate Capital and Their Relationship to Graduate Employability.” Education + Training 59 (4): 338–352. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-05-2016-0090.

- Tomlinson, M., and D. Jackson. 2021. “Professional Identity Formation in Contemporary Higher Education Students.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (4): 885–900. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1659763.

- Winterton, J., and J. J. Turner. 2019. Preparing Graduates for Work Readiness: An Overview and Agenda. Education + Training 61 (5): 536–551. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-03-2019-0044.

- Woodward, P. 2019. “Higher Education and Social Inclusion: Continuing Inequalities in Access to Higher Education in England.” In Handbook on Promoting Social Justice in Education, edited by R. Papa, 1–23. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Yorke, M. 2006. Employability in higher education: What it is – what it is not. Learning and Employability Series, Higher Education Academy.