Abstract

Although conventionally distinguished from the wilderness, the rural is nevertheless frequently perceived as a site of wildness, both in the sense of the uncultured/uncivilised and in the sense of the natural/authentic. Arguing that the politics of rurality have an important affective dimension that cannot be dismissed as illusionary or neatly separated from supposedly rational assessments, this article explores the affective economies that, in Sara Ahmed’s terms, cause particular feelings and values to become ‘stuck’ to the notion of rural wildness, influencing how it can be mobilised politically. Case studies of how rural wildness is harnessed as a political force in the self-presentation of the Countryside Alliance, a prominent British rural advocacy group, and in the successful 2013 Dutch documentary film The New Wilderness [De nieuwe wildernis] about a rewilding project in the Oostvaardersplassen reveal that, in both instances, the affective economies at play explicitly or implicitly support a conservative politics.

Introduction

In the course of countering the prevailing vision of the globalising world as a relentlessly urbanising space with an account of its ruralisation, Monika Krause (Citation2013, p. 243) insists that ‘dimensions of the rural enter more and more spaces’, including urban ones, and that the rural is itself ridden with tensions, many of them political. One tension is that between the wild, valued by conservationists and tourists, and the agricultural. Given the rural’s dominant image as a sedate, orderly realm, it may seem strange to place the wild—and its corollary landscape, the wilderness—within it. The history of the ‘rural as wilderness’, however, is longer than that of the rural as pastoral (Woods, Citation2011, p. 18) and intensified in the eighteenth century with Romanticism’s validation of the non-urban as uncorrupted wildness (Thacker, Citation2016) and the popularisation of the Picturesque and the Sublime, both of which celebrated encounters with ‘wild’ landscapes often situated in the countryside (Andrews, Citation1989; Cronon, Citation1996).

Though far from an oxymoron, rural wildness has no fixed meaning. On the one hand, it appears, particularly from an urban perspective, as ‘a place of danger and threat’ associated with the uncultured, the uncivilised, the non-modern and the lawless (Woods, Citation2011, p. 18). On the other, it attracts conservationists, tourists and counterurbanisers as an idealised ‘natural’ location presumed, as in Romanticism, to offer pristineness, authenticity and an escape from the pressures of globalisation. Consequently, the political force of rural wildness, defined in terms of how it can be mobilised to challenge or preserve the reigning ‘distribution of the sensible’ as that which ‘reveals who can have a share in what is common to the community based on what they do and on the time and space in which this activity is performed’ (Rancière, Citation2004, p. 12), varies. When assessing this political force, it is vital to remember that it derives not only from what is actually happening in rural areas but also from how rural communities and landscapes are perceived, and from the feelings and emotions associated with them. Accordingly, this article explores rural wildness as what Raymond Williams (Citation1977, p. 132) calls a ‘structure of feeling’, an emergent social experience associated with the ‘affective elements of consciousness and relationships’.

How affective elements form a structure—a ‘set, with specific internal relations’ (Williams, Citation1977, p. 132)—can be explained through Sara Ahmed’s notion of ‘affective economies’. For Ahmed, feelings and emotions are not properties of subjects or objects, but work, through their circulation between subjects and objects, to assign affective value. Much like monetary value becomes attached to commodities in a capitalist economy, in affective economies, over time, feelings and emotions become ‘stuck’ to particular subjects, objects or spaces such as the rural. This allows them to ‘align individuals with communities—or bodily space with social space—through the very intensity of their attachments’ (Ahmed, Citation2004a, p. 119).

Two case studies will demonstrate how affective economies and the alignments they produce can be mobilised politically: the self-presentation of the Countryside Alliance, a prominent British rural advocacy group, and the hugely successful 2013 Dutch nature documentary The New Wilderness [De Nieuwe Wildernis] about a rewilding project on land recovered from the sea. My analysis will show how, in both cases, the affective economies brought into play make the rural appear as a realm of wildness to which are stuck feelings and emotions that mark it as to be cherished and defended. This affective alignment, I contend, serves to support, explicitly or implicitly, conservative politics that seek to either maintain the existing distribution of the sensible or retrieve a past one. Before analysing the case studies, I will elaborate on the conceptual framework.

Conceptual framework

Structures of feeling are produced in the immediate present; they derive from ‘the specificity of present being, the inalienably physical’ (Williams, Citation1977, p. 128). Importantly, although still in development, they are not without form; they manifest as shared evaluative structures that endorse certain reactions while invalidating or pre-empting others. Rather than individual or personal, structures of feeling are fundamentally social: ‘although they are emergent or pre-emergent, they do not have to await definition, classification or rationalisation before they exert palpable pressures and set effective limits on experience and on action’ (Williams, Citation1977, p. 132). This indicates that structures of feeling should not be placed outside or before signification or meaning, but are sites of their unfolding.

As mentioned, Ahmed’s notion of ‘affective economies’ clarifies how emotions or feelings create meaning. Emerging from contact between a particular subject, object or place (such as the rural) and other subjects, objects or places, over time, as a result of repeated encounters, they start to stick to these subjects, objects or places—not just resting on their surface but actively shaping their meaning (Ahmed, Citation2004b, p. 4). Thus, the rural is not inherently a happy, serene, boring or frightening place, but becomes socially experienced as such by certain communities at certain times through particular affective economies and their modes of circulation. Importantly, Ahmed’s use of stickiness to describe how emotions or feelings become attached to subjects, objects or places suggests that they may also become unstuck or restuck. This can happen when affective economies expand or contract, modes of circulation change or moments of contact unfold differently, either of their own accord or through deliberate interventions.

Below, I first explore the way in which the Countryside Alliance, on its website and in public statements, capitalises on specific affective economies to present its advocacy for the preservation of certain rural practices as sincere and justified. This leads me to argue for the need to critique and to some extent ‘unstick’ the affective alignment of rural life with a marginalised community. The Countryside Alliance intensifies this alignment in order to solidify a sense of the rural population as, in its entirety, misunderstood and oppressed by urban elites, and therefore justifiably acting up to protect its pursuits, most notably fox hunting. It does this even though its causes—presented as benefiting ordinary rural ‘folk’ and the environment—are in effect socially and politically conservative. The Countryside Alliance’s strategic reinforcement of certain affective alignments to prevent change reinforces Ahmed’s point that emotion is ‘a form of cultural politics or world making’ involving an active orientation towards something (in this case, the positively valued rural and the negatively valued urban) that can harden into being ‘invested in particular structures such that their demise is felt as a kind of living death’ (Citation2004b, p. 12, emphasis in text). Accordingly, the involvement of emotions in social movements, instead of leading to such movements being dismissed as ‘impulsive and irrational’ (Woods, Anderson, Guilbert, & Watkin, Citation2012, p. 569), should be recognised as essential to their political force.

My subsequent analysis of The New Wilderness focuses on how this documentary sidesteps the paradox of its title—how can a wilderness be new?—and the fact that rewilding inevitably involves human intervention. It does so by evoking an affective economy in which the documented area, the Oostvaardersplassen (OVP), is narratively, visually and sonically presented in an idyllic mode that sticks comforting feelings of safety and familiarity to its purported wilderness, effectively ruralising it. By invoking the idyll, The New Wilderness appeals to an outdated notion of the ‘good life’ to which, however, because of its unattainability in the political present, it is only possible to stand in an affective relation of what Lauren Berlant (Citation2011, p. 1) has called ‘cruel optimism’, where ‘something you desire is actually an obstacle to your flourishing’. This is underscored by the way the documentary’s idyllic mode also evokes the feelings of inescapable personal responsibility and insecurity associated with life under neoliberal capitalism. In terms of the documentary’s politics, then, the affective economies in which it participates align it with both neoliberal capitalism and the populist right-wing nationalism currently in ascendency in the Netherlands, which also appeals to an affectively charged, largely imaginary idea of the country’s (rural) past.

While both case studies mobilise affective economies that tie rural wildness to conservative politics, The New Wilderness does so more implicitly and more ambivalently than the Countryside Alliance, which, as I will show next, overtly mobilises an affective alignment of rural wildness with a community valiantly fighting oppression to garner public sympathy and support for its aims.

The Countryside Alliance’s wild rural

As Williams shows in The Country & the City (Citation2011, originally published in 1973), his seminal account of the changing literary meanings and functions of the English countryside, the structures of feeling associated with the rural are culturally and historically specific constructs often out of step with the rural’s actual development. Thus, the tendency for pastoral poetry to refer back to a rural golden age can be seen as part of a structure of feeling in which ‘an idealisation, based on a temporary situation and a desire for stability, served to cover and to evade the actual and bitter contradictions of the time’ (Williams, Citation2011, p. 45). Its lack of accuracy, however, does not prevent this structure of feeling from having far-reaching social and political effects, as it

enfolds social values which, if they do become active, at once spring to the defence of certain kinds of order, certain social hierarchies and moral stabilities, which have a feudal ring but a more relevant and more dangerous contemporary application. Some of these ‘rural’ virtues, in twentieth-century intellectual movements, leave the land to become the charter of explicit social reaction: in the defence of traditional property settlements, or in the offensive against democracy in the name of blood and soil. (Williams, Citation2011, p. 36)

The structure of feeling that Williams considers as the opposite of the pastoral, which scorns the rural as exemplified by ‘the peasant, the boor, the rural clown’ (Citation2011, p. 36) and as standing in the way of industrial modernisation, has the same potential for politicisation. The politics of rurality, then, have an important affective dimension that can neither be dismissed as illusionary nor neatly separated from supposedly more rational assessments. Moreover, precisely because affective alignments between people and places involve feelings that tend to be considered spontaneous, unmediated and therefore ‘true’ and ‘real’, such alignments are difficult to challenge yet highly susceptible to being instrumentalised by political actors.

One such political actor is the Countryside Alliance. It was formed in 1997 out of the Countryside Business Group, the British Field Sports Society and the Countryside Movement, in response to the proposed fox hunting ban eventually enacted by Tony Blair’s Labour government in 2004. In 2002, the organisation had 110 000 members and 350 000 affiliate members (Perrone & Left, Citation2002); in 2015, it had 100 000 members (Bowern, Citation2015). Its revenue comes from subscriptions and fundraising/donations, respectively £3 230 217 and £1 333 930 in 2015 (Countryside Alliance, Citation2016, p. 7). A survey of Countryside Alliance members (Lusoli & Ward, Citation2005, pp. 57, 58) found them to be ‘predominantly male’, elderly, enjoying a ‘relatively high’ income and leaning ‘clearly to the centre-right of the political spectrum’.

According to Lusoli and Ward (Citation2005, p. 55),

though the pro-hunting cause is by far the most prominent issue, the Countryside Alliance has tapped into and encouraged the perception of a growing urban-rural divide in the United Kingdom, arguing that rural issues and countryside pursuits have been misunderstood and discriminated against by an urban political class.

Woods et al.’s discussion of British rural protest movements between the mid-1990s and mid-2000s (including the Countryside Alliance) focuses on the role emotions play in mobilising protestors and keeping them involved, but also acknowledges their function in ‘selling’ protest actions to wider audiences:

emotions were enrolled to frame the protests in media reports and political propaganda, and to ‘explain’ and legitimize uncharacteristic behaviour by countryside folk who were represented as moderate, responsible and law-abiding citizens. (Citation2012, pp. 568, 569)

It is this selling function of affect—fitting its role, in Ahmed’s conceptualisation, as part of a value-and-meaning-generating economy—that I want to explore here. As Woods et al. (Citation2012, p. 572) show, to attract people to join its protests, the Countryside Alliance capitalised more on already established positive emotional attachments to the countryside than on any fear, distress and anger provoked by impending government policies seen to marginalise the rural. However, to sell the protests to the larger public and the national media, it strove to stick the idea of unjust marginalisation to the rural as tightly as possible. Thus, the ‘About the Countryside Alliance’ page of the organisation’s website announced that the movement originated

partly as a response to the newly elected Labour Government’s pledge to ban hunting with dogs but also borne of a need to represent an increasingly marginalised rural minority. We are here to give rural Britain a voice.Footnote 1

In this statement, the impending hunting ban is identified as the catalyst for the Countryside Alliance’s formation, but is immediately supplemented by and conflated with the more general aim of representing a ‘rural minority’ identified as ‘increasingly marginalised’. The use of the term ‘minority’ and the phrase ‘to give a voice’ aligns the aims of the Countryside Alliance with those of interest groups working on behalf of other minorities, and is designed to lay claim to the feelings of sympathy such minorities are thought to provoke in British society—even though the Countryside Alliance’s main support is among Tory and, increasingly, UKIP voters, who tend not to be very sympathetic towards these minorities (Anderson, Citation2006).

As part of the same affective economy in which the rural circulates as a site of righteous and therefore sympathetic victimhood, Richard Burge, then the Countryside Alliance’s Chief Executive, claimed that the 2002 Liberty and Livelihood March, which brought 400 000 people to Central London, was ‘about country mindedness, and country minded people who feel disenfranchised by the system [and] feel like a colony in their own nation … The march is about demanding to be heard’ (qtd. in Ward, Gibson, & Lusoli, Citation2003, p. 55, emphasis added). The reference to colonialism connects to a postcolonial affective economy in which being made to feel like a colonised subject implies not only geographical peripherality—here, without a sense of irony, displaced to the heart of the former British Empire—but unjust, actionable oppression, exploitation and marginalisation. In other words, the analogy drawn between the countryside and the colony supports the affective demand to be heard with an affective claim to share in the epistemological privilege supposedly granted to the victims of colonialism.

The Countryside Alliance specifically claims epistemological privilege with regard to understanding the rural, while dismissing those from the urban centre as incapable of and unwilling to see beyond naïvely inaccurate idyllic conceptions of the countryside. Thus, during the 2001 Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) crisis, people living in the rural tended to

travesty a place image of the rural idyll to underline the City’s misunderstanding and misrepresentation of the Countryside and the ignorance embedded in the centralised definition of FMD risks and the associated management structures put in place, reaffirming the competence of local knowledge. (Bickerstaff, Simmons, & Pidgeon, Citation2006, p. 854)

Part of a series of ‘performances of marginality’ (Bickerstaff et al., Citation2006, p. 854), such travestying heightens the political charge of affective economies in a move that could be seen as one of speculation. Designed to garner sympathy and to mobilise support, it intensifies the circulation of certain positive values—such as being down-to-earth, hard-working and not squeamish about dealing with the realities of life and death—as irrevocably part of the rural (stuck in it), while keeping other values from circulation or dismissing them as merely stuck onto it by ‘outsiders’. In Ahmed’s terms (Citation2004b), this reifies certain emotions as inherently belonging to the rural (as being of it), while marking others as artificial and external. Crucially, however, the emotions and values posited by rural dwellers as essential to the rural’s actuality were just as mythical as the supposed ideas of the scorned urbanites (Bickerstaff et al., Citation2006).

For the attempt to naturalise an affective alignment between the rural and an unjustly marginalised community to succeed and for its claim to epistemological privilege to be seen as valid, the Countryside Alliance cannot be associated with economic or political privilege. This would undermine the equation between the rural and the oppressed underpinning its claim to be a broad rural emancipatory movement rather than a single-issue organisation protecting elite leisure pursuits. Consequently, the Countryside Alliance website downplays the fact that both its President (Baroness Mallalieu QC) and its Vice-President (Baroness Golding) are well-to-do members of the House of Lords, while the previous Vice-President, the 6th Duke of Westminster, was one of Britain’s foremost landowners and sixth on the Sunday Times Rich List 2016 (Davies, Citation2016). The names of the President and Vice-President only appear under a submenu-item (‘Our Structure’) and no photographs of the Baronesses (or of Lord Mancroft, a hereditary baron and House of Lords member, who is chairman) are provided.Footnote 2

As Anderson (Citation2006, p. 733) notes, the Countryside Alliance was not fully effective in convincing the public that the 2002 Liberty and Livelihood March was not mainly about foxhunting, and its own supporters were divided on which issues should be of most concern. However, it remains a prominent participant in discussions about British rural policy and has continued its efforts to garner sympathy and support by cementing the affective alignment of the rural with oppression and legitimate anger—the current website refers, for example, to ‘the injustices of poor mobile phone signal and broadband in the countryside’.Footnote 3 The next section locates, in The New Wilderness, another, albeit less explicit mobilisation of an affective economy in which rural wildness comes to support a conservative politics.

The New Wilderness’s rural wildness

The New Wilderness is a 2013 nature documentary directed by Mark Verkerk and Ruben Smit, which was shown in Dutch cinemas (drawing over 400 000 people) and, in three parts, on public television. In 2014, it won the Rembrandt Award for Best Dutch Film and the Golden Calf for the Most Popular Film at the Netherlands Film Festival, both awarded by public vote. The New Wilderness was filmed over the course of a year in the Oostvaardersplassen (OVP), a nature reserve covering an area of 56 square kilometres reclaimed from the sea in 1968, part of the province of Flevoland. The reserve is flanked by the cities of Almere (ca. 200 000 inhabitants) on the south-west and Lelystad (ca. 76 000 inhabitants) on the north-east, and has major roads running along its southern and northern borders (for a map, see Lorimer & Driessen, Citation2014, p. 173). One of the first rewilding projects in the world, OVP is part of Natura 2000, a Europe-wide network of existing and reconstructed wildlife habitats. It combines wetland with reed beds, grassland and small woodlands, attracting a variety of birds and other small local wildlife. It is best-known, however, for its introduced populations of Konik horses and Heck cattle.Footnote 4 In and around The New Wilderness, affective economies are mobilised that work to stick feelings of awe and (national) pride to OVP as, in the words of the voice-over narrator, a ‘new wilderness’ in the middle of ‘the most densely populated country of Europe’ (Verkerk & Smit, Citation2013).Footnote 5 What the documentary sidesteps is the question of how a wilderness can be new, which is central to the assessment of rewilding as an increasingly popular policy affecting rural landscapes.

What is meant by rewilding is contested and varies historically and geographically (Jørgenson, Citation2015). When taken at face value, the term suggests a project to restore a particular area, usually rural, to a former state of wildness or wilderness. Rewilding appears inherently contradictory when wilderness is taken to refer to ‘land “untrammelled by man”’ (Arts, Fischer, & Van der Wal, Citation2012, p. 239). It has been associated with a naïve investment in a ‘fantasy of ecological throwback’ (Saunders, Citation2013) and even with fascism and eugenics because of Nazi support for the original attempt to recreate the wild predecessors of domestic cattle by Lutz and Heinz Heck, after whom Heck cattle are named (Lorimer & Driessen, Citation2016).

Yet rewilding projects have also been heralded as ‘wild experiments’, which, rather than claiming to replicate a pristine wilderness of the past, acknowledge that what they produce are ‘analogues’ (Lorimer & Driessen, Citation2014, pp. 169, 172, emphasis in text; see also Jepson, Citation2015). From this perspective, rewilding eschews traditional conservationism’s commitment to linear, predictable ecologies by taking a ‘speculative approach’ that, in minimising planning and modelling, is open to surprises (Lorimer & Driessen, Citation2014, p. 175). OVP then emerges as ‘an uncertain “wild thing”, capable of putting accepted knowledge at risk’ (Lorimer & Driessen, Citation2014, p. 175). Here, wildness is not attached to a notion of authentic wilderness or opposed to the rural’s cultivated landscape, but is a positive evaluation ‘stuck’ to unruly, unconventional ‘cosmopolitan’ or ‘ecomodernist’ (Lorimer & Driessen, Citation2016) ways of bringing the rural and the wilderness together.

A tension between wildness in the sense of the undisturbed and wildness in the sense of the experimental remains, however, in the way in which projects like OVP are presented to and perceived by the public. This has been most obvious in heated public discussions about animal welfare, with those arguing that OVP’s herbivores, in situations of food scarcity, should be left to die challenging those contending that, since the herbivores are kept in an enclosure without predators and thus not fully wild, they should be subject to the same animal protection legislation as farm and domestic animals. After a court case, it was decided that rangers, taking on the perspective of wolves, would shoot weakened animals unlikely to survive the winter (Lorimer & Driessen, Citation2014, p. 174; see also Lorimer & Driessen, Citation2013; Jepson, Citation2015). This constitutes a move away from wildness that nevertheless seeks to maintain a spirit of wildness through the invocation of the wolf’s eye. As such, it reinforces the contradictions inherent to rewilding, which are further magnified by ‘the ongoing image wars relating to OVP’ pitting amateur videos of animal starvation and professional wildlife photography against each other (Lorimer & Driessen, Citation2014, p. 177).

The New Wilderness opens up a new front in these image wars and illuminates how, as in the battle on behalf of the countryside waged by the Countryside Alliance, political force may be produced through affective economies. Although the ‘new’ in the documentary’s title signals OVP’s recent origin and thus hints at its artificiality, the voice-over narration presents OVP as a natural realm untouched by humans:

Of the land we reclaimed from the sea, we forgot a piece: the Oostvaardersplassen. Here only the laws of nature reign. These laws are concerned with the right of the strongest, with collaboration and rivalry, with living and letting live. It is in this cohesion that the unparalleled force of nature shows itself. (Verkerk & Smit, Citation2013, emphasis added)

This statement obscures that the Oostvaardersplassen were, in effect, never forgotten, as the area was managed by the State Forestry Service from its reclamation. Not the ‘laws of nature’ determined its course, but human intervention: the Konik horses, Heck cattle and deer, for example, were only introduced in the 1980s. Intervention continues in the annual culling of starving animals and regular maintenance activities. Given these widely known facts, the documentary’s insistence that it portrays a complete, fully wild and natural ecosystem can only be taken as a deliberate strategy.

I want to suggest that the film’s visual, narrative and sonic construction of OVP as a wild landscape mobilises an affective alignment of OVP less with the wilderness as either a hellish realm of danger, darkness and hostility or a paradisiacal realm of simplicity, transcendence, beauty and insight (Arts et al., Citation2012) than with the rural as an idyllic landscape offering a timeless sense of safety and familiarity.

At this point, it is helpful to consider the Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin’s account of the idyll as a chronotope. For Bakhtin, spatiality—in literature and in life—is always intertwined with temporality, but in culturally and historically variable ways. Different constellations of space-time produce different generic forms or chronotopes capable of accommodating certain events, experiences and meanings while excluding others. Chronotopes have an affective dimension in that they are ‘always colored by emotions and values’ (Bakhtin, Citation1996, p. 243). The idyllic chronotope, as described by Bakhtin, combines the cyclical ‘folkloric time’ and ‘unity of place’ associated with the positively valued image of ‘primitive man’ existing ‘in the collective consuming of the fruits of his labor and in the collective task of fostering the growth and renewal of the social whole’ (Bakhtin, Citation1996, p. 211). This rural time-space, itself largely imaginary, is placed before social stratification and before the individualist interiority installed by capitalism. Affectively, everything in the idyll is familiar, comprehensible, comforting and safe: ‘scattered through the great, cold, alien world there are warm little corners of human feeling and kindness’ (Bakhtin, Citation1996, p. 233). The idyll as the feel-good realm of a homogeneous, united community constitutes a local refuge that, in the late eighteenth century, comes to stand in the way of a relationship to the world as a whole:

It is necessary to find a new relationship to nature, not to the little nature of one’s own corner of the world but to the big nature of the great world, to all the phenomena of the solar system, to the wealth excavated from the earth’s core, to a variety of geographical locations and continents. (Bakhtin, Citation1996, p. 234)

The fact that a nostalgic desire for the idyll nonetheless persists, in literature and in life, marks it as what Berlant (Citation2011, p. 2) calls a ‘good-life genre’ to which people optimistically continue to adhere even when ‘the evidence of [its] instability, fragility, and dear cost abounds’ because, on the level of people’s affective alignment with the rural as an idyllic realm, it offers ‘predictable comforts’.

The New Wilderness, in repeatedly stating that the eternal turning of the ‘wheel of life’ ensures that ‘there is always a new beginning’ (Verkerk & Smit, Citation2013), presents OVP’s temporality as cyclical and, by leaving its man-made fencing out of the visual frame, invokes the organic ‘unity of place’ that Bakhtin associates with the idyllic chronotope. Despite some references to the ‘great wisdom’ of animal instinct, moreover, the wildlife is anthropomorphised as forming ‘families’ that knowingly and contentedly follow the ‘rules of nature’ (Verkerk & Smit, Citation2013). According to the voice-over, the two most important rules are that there is no place for weakness and that it is not possible to survive alone. Any negative feelings viewers may associate with these stark edicts are assuaged by referring to the strong sense of community among and within the animal ‘families.’ Even the fact that ‘death is always lurking’ (Verkerk & Smit, Citation2013) is not seen as unsettling. Rather, death is made part of a repetitive, comforting flow in which each individual demise is redeemed by a new birth or the continued survival of the group, in line with Bakhtin’s assertion that the idyll’s ‘unity of place brings together and even fuses the cradle and the grave … the life of the various generations who had also lived in that same place, under the same conditions, and who had seen the same things’ (Citation1996, p. 225).

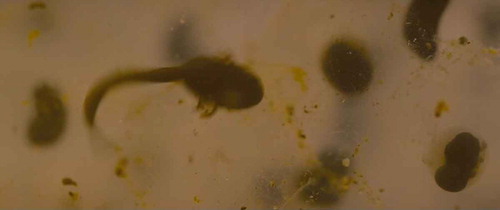

The film’s idyllic portrayal of OVP is reinforced by aestheticised images of the landscape and its inhabitants, created, as revealed in Siebe Steenwinkel and Helen Delachaux’s making-of documentary Behind the Scenes of The New Wilderness [Achter de schermen van De nieuwe wildernis], by using extreme magnification, slow-motion and high-speed time-lapse technology (Figures ). These interventions counter the voice-over’s claim that the film merely documents the ‘unparalleled force of nature’, as does the soundtrack. Traffic noise from nearby roads has been filtered out to approximate the rural idyll’s ‘idealised soundscape’ of tranquillity, peacefulness and quiet (Woods, Citation2011, p. 111). The sounds of nature, in contrast, have been amplified, matched with non-synchronous images, complemented by an orchestra and a reed quintet, and even created from scratch: at one point, a choir creates an intense buzzing sound to accompany images of meat flies that in reality make no such sound. This illusory soundscape is designed to fit the idyllic affective atmosphere conjured by the images and the voice-over narration, with repeated musical motifs underscoring the idea that time in OVP is cyclical.

Notably, although the making-of documentary exposes The New Wilderness’s extensive image and sound manipulation, it also features various people involved in the film’s production insisting that their encounter with the ‘unspoiled wildness’ of OVP yielded positive feelings and emotions which they then conveyed directly to the audience (Steenwinkel & Delachaux, Citation2013). In a similar vein, the soundtrack composer downplays his interventions by asserting that ‘music should not tell you what to feel; it should help what you feel’ (Steenwinkel & Delachaux, Citation2013). These statements assume an inherent alignment between a type of landscape or a piece of music and a particular feeling or emotion. Following Ahmed, however, it seems more likely that wildlife documentaries and their stock tropes, as part of an affective economy, have, over time, accustomed audiences to sticking feelings of amazement, awe and reverence, as well as a sense that wilderness should remain, as far as possible, untouched by humans, to what they accept (despite knowing better) as its unmediated visual and sonic registration.

By invoking the idyll, however, The New Wilderness also ruralises the wilderness, allowing it to become part of a different affective economy within which it can be reimagined as a comforting refuge where humans, too, can get away from ‘the great, cold, alien world’ (Bakhtin, Citation1996, p. 233). Viewers are encouraged to identify with OVP’s anthropomorphised animals and what is presented as their ‘good life’ by the voice-over’s use of ‘you’ to simultaneously address the animals on-screen and the audience: ‘the most important question of the spring is: who will be your partner?’ (Verkerk & Smit, Citation2013). In the making-of documentary, moreover, Dutch DJ Don Diablo, shown visiting OVP, notes that by becoming ‘city people removed from nature’ we no longer realise that there is more than the ‘big, bad world’ of our everyday lives (Steenwinkel & Delachaux, Citation2013). Placed outside the ‘big, bad world’, OVP is positioned as able to offer a desirable and emotionally reinvigorating escape from the complexities of the global and the urban, implicitly deemed unnatural.

This affective alignment of OVP with sanctuary from the ‘big, bad world’ has a strong affinity with a politics of localism and nationalism. Indicative of this is the way the film’s director and producer, in the making-of documentary, refer to The New Wilderness as ‘primordially Dutch’ and insist that a small wilderness area like OVP in a country like the Netherlands can be as ‘great’ as much bigger wilderness areas such as the Amazon or the Serengeti (Steenwinkel & Delachaux, Citation2013). The filmmakers’ determination to ‘stick’ a sense of national pride to OVP is also apparent in the voice-over’s announcement that ‘this is our country as you’ve never seen it before’ and the film’s tagline: ‘big nature in a small country’ (Verkerk & Smit, Citation2013).

In addition, the film’s invocation of the idyll, through its valorisation of the familiar and its distaste for change, lends itself to a populist politics. Bakhtin identifies the ‘man of the people’ who ‘holds the correct attitude toward life and death, an attitude lost by the ruling classes’ as being ‘of idyllic descent’ (Citation1996, p. 235). Thus, it is perhaps no coincidence that the success of The New Wilderness coincided with the continuing rise, particularly in rural areas, of Geert Wilders’s right-wing, populist-nationalist, islamophobic Party for Freedom. Not only does Wilders position himself as an anti-establishment man of the people unable to ‘understand accepted falsehoods and conventions (which then exposes these for what they are)’ (Bakhtin, Citation1996, p. 236), but his party peddles an idealised image of a 1950s homogeneous pre-immigration, pre-EU Dutch community as a distribution of the sensible that might be recovered by expelling everything ‘foreign’ (Vossen, Citation2011).

We may ask, however, exactly what kind of escape is offered by a film in which the birth of a black Konik foal leads the voice-over to announce: ‘From the moment you are born, you have to fight to survive’ (Verkerk & Smit, Citation2013). While the idyllic collective reproduces itself year after year, individual animals are subjected to a ruthless survival-of-the-fittest regime. Far from offering respite from the ‘big, bad world’, this resonates with the way neoliberal capitalism individualises workers to make them responsible for their own advancement, while at the same time relying on their disposability (Harvey, Citation2011, pp. 168, 169). Much like the documentary’s voice-over sternly rebukes the Konik foal for not eating enough during the summer to survive the winter, knowing full well that the fenced area of OVP does not contain enough food to sustain the entire Konik population, neoliberal capitalism holds individuals responsible for not taking advantage of the opportunities it falsely claims to offer to everyone in the global economy. In the end, then, the political force of the wild rural produced through the affective economies The New Wilderness mobilises is conservative, evoking more readily the ‘reactionary modernism’ Lorimer and Driessen (Citation2016) associate with historical rewilding than the experimental ‘ecomodernism’ they see as characteristic of present-day rewilding projects, including OVP.

Conclusion

Both The New Wilderness and the Countryside Alliance emerged in a geopolitical context where received notions of the ‘good life’, rural and urban, which were never achievable for all in the first place, have, in Berlant’s words, ‘become more fantasmatic, with less and less relation to how people can live’ (Citation2011, p. 11, emphasis in text). Rather than coming up with new models, the affective economies mobilised by the Countryside Alliance conjure an idealised rural realm under threat from the urban but salvageable through political agitation, while those brought into play by The New Wilderness present an even more fantasmatic ‘good life’ in depicting OVP as a ‘scene of desire’ (Berlant, Citation2011, p. 11) offering an idyllic refuge to animals and humans alike.

In this way, both the advocacy group and the documentary foster an affective state of what Berlant calls cruel optimism, defined as

a relation of attachment to compromised conditions of possibility whose realization is discovered either to be impossible, sheer fantasy, or too possible, and toxic. What’s cruel about these attachments … is that the subjects who have x in their lives might not well endure the loss of their object/scene of desire, even though its presence threatens their well-being. (Citation2011, p. 24)

Becoming emotionally aligned with and thus invested in the Countryside Alliance’s image of rural life as quintessentially bound up with elite pursuits like foxhunting can be cruel in drawing attention away from issues affecting the rural population more generally and in promoting anger and resentment at the perceived loss of a cherished way of life that never characterised the rural as a whole. In The New Wilderness, the unfulfillable promise of an idyllic wilderness realm organised according to simple, consistent principles and continuities that render life predictable and, in theory, survivable for those who follow the rules, acts as a cruel obstructive fantasy not despite but because of the positive feelings stuck to it: because this fantasy does not feel obstructive, it is easily mobilised politically in support of localism, nationalism, populism and even neoliberalism. Such mobilisation, as in the case of the Coutryside Alliance, aims, in Rancière’s terms (Citation2004, p. 12), not at a redistribution of the sensible proposing new, uncompromised forms of the ‘good life’, but at affirming idealised versions of existing or past distributions.

By analysing the self-presentation of the Countryside Alliance and the narrative, visual and sonic representation of the OVP rewilding project in The New Wilderness through the lens of Williams’s structure of feeling and Ahmed’s affective economies, I have sought to illuminate how emotions and feelings become ‘stuck’ to the rural as a realm of wildness, creating affective alignments susceptible to political mobilisation, here in the service of conservatism. Crucially, affective economies, like other economies, obfuscate the conditions for creating value, making it seem natural. Against this, I have stressed that the emotions and feelings stuck to the rural do not inherently belong to it, and that therefore the political force of the rural is never fixed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. This text no longer features on the current website, but can be viewed through the Internet Archive: https://web.archive.org/web/20140103051130/http://www.countryside-alliance.org/CA/article/about-the-countryside-alliance.

2. http://www.countryside-alliance.org. See Hetherington (Citation2012) for a critique of the Countryside Alliance’s alignment with landowner interests.

5. All quotations from The New Wilderness and the making-of documentary were translated from Dutch by the author.

References

- Ahmed, S. (2004a). Affective economies. Social Text , 22 , 117–139. doi:10.1215/01642472-22-2_79-117

- Ahmed, S. (2004b). The cultural politics of emotion . Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Anderson, A. (2006). Spinning the rural agenda: The countryside alliance, fox hunting and social policy. Social Policy & Administration , 40 , 722–738. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9515.2006.00529.x

- Andrews, M. (1989). The search for the picturesque: Landscape aesthetics and tourism in Britain, 1760–1800 . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Arts, K. , Fischer, A. , & Van der Wal, R. (2012). The promise of wilderness between paradise and hell: A cultural-historical exploration of a Dutch national park. Landscape Research , 37 , 239–256. doi:10.1080/01426397.2011.589896

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1996). Forms of time and of the chronotope in the novel: Towards a historical poetics. In M. Holquist (Ed.), The dialogic imagination: Four essays by M.M. Bakhtin (pp. 84–258). Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Berlant, L. (2011). Cruel optimism . Durham, NC: Duke University Press.10.1215/9780822394716

- Bickerstaff, K. , Simmons, P. , & Pidgeon, N. (2006). Situating local experience of risk: Peripherality, marginality and place identity in the UK foot and mouth disease crisis. Geoforum , 37 , 844–858. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2005.11.004

- Bowern, W. N. M. P. (2015). New boss of countryside alliance Tim Bonner on the rural battles won—And those still to fight. Western Morning Post . Retrieved from http://www.westernmorningnews.co.uk

- Countryside Alliance . (2016). Financial statements for the year ended 31 December 2015 [PDF]. Retrieved from http://www.countryside-alliance.org

- Cronon, W. (1996). The trouble with wilderness: Or, getting back to the wrong nature. Environmental History , 1 , 7–28. doi:10.2307/3985059

- Davies, R. (2016). Property Tycoons David and Simon Reuben top Sunday Times rich list. The Guardian . Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com

- Harvey, D. (2011). A brief history of neoliberalism . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hetherington, P. (2012). The countryside alliance cares for liberty but not livelihoods. The Guardian . Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com

- Jepson, P. (2015). A rewilding agenda for Europe: Creating a network of experimental reserves. Ecography , 38 , 1–8 EV. doi: 10.1111/ecog.01602

- Jørgenson, D. (2015). Rethinking rewilding. Geoforum , 65 , 482–488. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.11.016

- Krause, M. (2013). The ruralization of the world. Public Culture , 25 , 233–248. doi:10.1215/08992363-2020575

- Lorimer, J. , & Driessen, C. (2013). Bovine biopolitics and the promise of monsters in the rewilding of Heck cattle. Geoforum , 48 , 249–259. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.09.002

- Lorimer, J. , & Driessen, C. (2014). Wild experiments at the Oostvaardersplassen: Rethinking environmentalism in the Anthropocene. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers , 39 , 169–181. doi:10.1111/tran.12030

- Lorimer, J. , & Driessen, C. (2016). From ‘Nazi cows’ to cosmopolitan ‘ecological engineers’: Specifying rewilding through a history of Heck cattle. Annals of the American Association of Geographers , 106 , 631–652. doi:10.1080/00045608.2015.1115332

- Lusoli, W. , & Ward, S. (2005). Hunting protestors: Mobilisation, participation and protest online in the countryside alliance. In S. Oates , D. Owen , & R. K. Gibson (Eds.), The internet and politics: Citizens, voters and activists (pp. 52–70). London: Routledge.

- Perrone, J. , & Left, S. (2002). The countryside alliance. The Guardian . Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com

- Rancière, J. (2004). The politics of aesthetics . ( G. Rockhill , Trans.). New York, NY: Continuum.

- Saunders, F. S. (2013, May 24). Feral: Searching for enchantment on the frontiers of rewilding by George Monbiot—Review. The Guardian . Retrieved from http://www.guardian.co.uk

- Steenwinkel, S. , & Delachaux, H. (2013). Achter de schermen bij de nieuwe wildernis [Motion Picture] . Amsterdam: EMS Films, DVD.

- Thacker, C. (2016). The wildness pleases: The origins of romanticism . Abingdon: Routledge.

- Tsouvalis, J. , Seymour, S. , & Watkins, C. (2000). Exploring knowledge-cultures: Precision farming, yield mapping, and the expert-farmer interface. Environment and Planning A , 32 , 909–924. doi:10.1068/a32138

- Verkerk, M. , & Smit, R. (2013). De nieuwe wildernis [Motion Picture] . Amsterdam: EMS Films, DVD.

- Vossen, K. (2011). Classifying wilders: The ideological development of Geert Wilders and his party for freedom. Politics , 31 , 179–189. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9256.2011.01417.x

- Ward, S. , Gibson, R. , & Lusoli, W. (2003). Online participation and mobilisation in Britain: Hype, hope and reality. Parliamentary Affairs , 56 , 652–668. doi:10.1093/pa/gsg108

- Williams, R. (1977). Structures of feeling. In Marxism and literature (pp. 128–135). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Williams, R. (2011). The country & the city . Nottingham: Spokesman.

- Woods, M. (2011). Rural . London: Routledge.

- Woods, M. , Anderson, J. , Guilbert, S. , & Watkin, S. (2012). ‘The country (side) is angry’: Emotion and explanation in protest mobilization. Social & Cultural Geography , 13 , 567–585. doi:10.1080/14649365.2012.704643