ABSTRACT

Due to agricultural abandonment and the urban preference for ‘wilderness’ over ‘rural’ areas, abandoned settlements and rewilding grasslands are often the last traces of agriculture in today’s protected areas of the Northern Apennines. However, since the late 1990s, an increasing number of policy makers have appreciated these spatial manifestations of the nature/culture gestalt and developed projects to conserve the last grasslands in rewilding protected areas. Does the land cover reflect these changing attitudes? Using the Foreste Casentinesi National Park as our case in point, we aim to (1) detect land cover changes during 1990–2001 and 2001–2010; (2) analyse change trajectories; and (3) reveal potential discrepancies between the conservation of biodiversity and rural built heritage. Our results show that grassland loss dominated 1990–2001, whereas grassland maintenance/restoration can be observed for 2001–2010. However, the decadence of the rural built heritage seems to continue.

Introduction and aims

‘Implicit in the wilderness idea is an anti-human bias that seeks to present nature as the antithesis of culture’ (Gade, Citation1999, p. 6)

Background

In many Southern European mountain regions, the complementary processes of urbanisation and deagrarianisation have led to changes in rural land use practices, often leading to the complete abandonment of agricultural land since the 1950s (on European mountains in general see MacDonald et al., Citation2000; on Mediterranean mountains in particular see Papanastasis, Citation2012). In a case study in the Borau Valley of the Spanish Pyrenees, an area characterised by severe depopulation during the 20th century, Vicente-Serrano, Lasanta, and Cuadrat (Citation2000) noticed increased woody vegetation on former agricultural land and called this process the ‘banalization of landscape’. Agricultural abandonment was also observed in the second half of the past century in Italian mountain regions (Vecchio, Citation1989). Bender and Haller (Citation2017) analysed the nexus of population mobility and landscape development in the Alps and identified deep-rooted cultural practices as important drivers of change. In a quantitative study, Falcucci, Maiorano, and Boitani (Citation2007, p. 622) detected large increase in forest areas in the Alps and Apennines between 1960 and 2000. The Apennines, which Goethe in his Italian Journey called ‘ein merkwürdiges Stück Welt’ (‘a remarkable part of the world’), additionally presented a large decrease in pastures.

Due to their regional geographic characteristics, the Northern Apennines are a perfect case in point (Farina, Citation1995, Citation2006; pp. 256–257); mountain depopulation in Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna was not considered alarming until the end of the 1930sFootnote1 (Toniolo, Citation1937), but gathered pace from the 1950s. While urban regions on the plains of Po and Arno, as well as along the coasts of the Ligurian and Adriatic Sea, expanded,Footnote2 many rural mountain municipalities in the Northern Apennines experienced abandonment of agricultural land and settlements (for case studies in the Northern Apennines see Dossche, Rogge, & Van Eetvelde, Citation2016; Kühne, Citation1974; Torta, Citation2004; Vos, Citation1993). This process of physical and demographic urbanisation was accompanied by profound attitudinal changes leading to (1) the preference of ‘natural landscapes’ over ‘rural landscapes’ and (2) the creation of protected mountain areas managed according to the paradigm of ‘renaturalization’ (Agnoletti, Citation2014)—a tendency influenced by discussions on conserving wilderness.Footnote3 In the first half of the 1980s, this development resulted in the institutional establishment of the ‘wilderness’ movement in Italy (Zunino, Citation1995). Yet in the 1990s, with the implementation of the EU Habitats Directive and the adoption of the Mediterranean Landscape Charter (followed by the European Landscape Convention in 2000; see Jones, Howard, Olwig, Primdahl, & Sarlöv Herlin, Citation2007; Olwig, Citation2007), a shift from wilderness-style to utilised protected areas occurred in Western/Mediterranean Europe (Zimmerer, Galt, & Buck, Citation2004, p. 527). This shift was accompanied by a general change in attitude (D’Angelo, Citation2016): the return to the appreciation of ordinary agricultural landscapes among rewilding mountains—mostly for biodiversity conservation but also for cultural-historical motives. In a Council of Europe publication, Sangiorgi (Citation2008, p. 5) underlines that ‘the landscape, the environment, the land and the people are part of one and the same unit and that this heritage should be preserved not only as a memory of the past but also as a resource for future development’. This fact particularly applies to the protected areas of IUCN category II (principally aimed at the conservation of biodiversity, ecological structures, and processes) in the Tuscan and Emilian-Romagnan Apennines, which today are a type of ‘green and mountainous interstice’ (sensu Gambino & Romano, Citation2003, p. 8) embedded between urbanised lowlands.

In the Central Italian Foreste Casentinesi National Park, the appearance of new attitudes toward grasslands—and the emerging consciousness for the need of conserving these traces of human presence—can be observed since the late 1990s. Against the massive loss of grasslands since the 1950s,Footnote4 Tellini Florenzano (Citation1999) published a report on a bird monitoring project carried out during the 1990s, concluding that:

‘It would be of highest importance to stop the current tendency of forest regrowth (natural and artificial), conserving at least the present share of pastures, arable lands, or shrub formations. To preserve the current state, the direct intervention of humans is necessary and appropriate incentives for agropastoral activities in the area should be provided. Unfortunately, hardly any of these nonforest environments form part of the public regional heritage. However, from a global perspective on conservation, it is nevertheless possible to intervene on private properties. […] Within this scope, the middle and higher elevations (700–1100 masl) are of importance’. (Tellini Florenzano, Citation1999, p. 78; translated from Italian by the authors).

At the same time, in 1999, a project to restore pasture habitats in the park started in the ‘Monte Gemelli, Monte Guffone’ Natura 2000 site (IT4080003), which was financed by the EU program LIFE NATURA (LIFE99 NAT/IT/006237). More recently, in 2013, the park authorities sent out a press release announcing a project in collaboration with the local Union of Mountain Municipalities (Unione dei Comuni Montani del Casentino), which aims at recovering some abandoned pastures in the south of the park:

‘The grasslands currently existing in the protected area are results of the preexisting clearing of forest and could only be conserved over centuries by their use. The latter represents an important element of biological diversification and safeguards the existence of ecotones […], where the extraordinary vegetational, faunistic, landscape, and environmental biodiversity typical for these habitats is as rare as particularly worthy of attention’. (Parco Nazionale delle Foreste Casentinesi, Monte Falterona e Campigna, Citation2013, s.p.; translated from Italian by the authors).

Hence, despite the continuing appeal and aim of creating ‘wilderness’ in this Apennine protected area, since the turn of the millennium we can observe a series of efforts to maintain grasslands in the midst of rewilding mountains; these include the acquisition of abandoned poderi (small farms belonging to a larger mezzadria or sharecropping systemFootnote5) by the park authorities to ensure the conservation of grasslands:

‘The acquirement of the poderi of Bagnatoio, Briganzone, Centine and Romiti […] (392 ha, 700 millions [of Italian lire]) has almost been finalised. By acquiring these properties, the park authority aims to take care of the management and restoration of some of the most significant rural environments of the park. The agricultural part of these areas could be leased to breeders for the seasonal pasturing of the livestock [sheep and cattle].’ (Parco Nazionale delle Foreste Casentinesi, Monte Falterona e Campigna, Citation2002a, p. 31; translated from Italian by the authors).

If human-made grasslands in the Foreste Casentinesi National Park are considered spatial manifestation of the nature/culture gestalt (Gade, Citation1999)—where ‘culture’ should be understood in a broad sense, one that considers both individual and community, law, justice, and customs (see Olwig, Citation1996)—, then the question emerges whether this attitudinal change (from the preference of rewilding to the consciousness of conserving the remaining grasslands) is reflected by the development of the park’s land cover. Is there a noticeable decrease in—or even a stop in—shrub encroachment on grassland after 2000? Did grassland conservation go along with the restoration of abandoned farmsteads? Hence, the present article specifically aims at (1) detecting land cover changes during 1990–2001 and 2001–2010; (2) analysing change trajectories during 1990–2001 and 2001–2010, focusing on changes between ‘grassland’ and ‘wood or shrubland’ in different altitudinal zones; and (3) revealing potential discrepancies between the conservation of biodiversity and rural built heritage by identifying abandoned farmsteads on stable grassland.

Material and methods

Study area

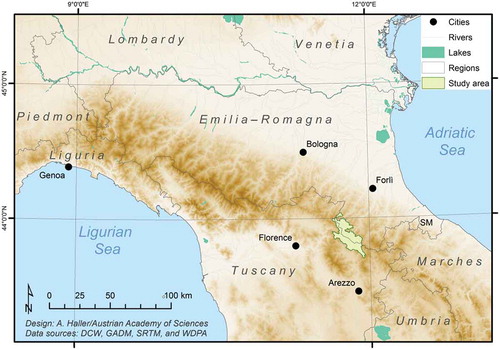

The Italian Foreste Casentinesi National Park (officially Parco Nazionale delle Foreste Casentinesi, Monte Falterona e Campigna), created between 1990 (tentative definition of the park’s boundaries; Ministerio dell’Ambiente, Citation1990) and Citation1993 (establishment of the government body of the national park; Ministerio dell’Ambiente, Citation1993), is located between approximately 43° 42ʹ and 44° 02ʹ northern latitude, and 11° 42ʹ and 11° 56ʹ eastern longitude (). The park covers more than 36,000 ha of the Northern Apennines reaching almost equally into Tuscany (southwest) and Emilia-Romagna—in fact the Romagna toscana—(northeast). The park’s municipalities of San Godenzo and Londa belong to the Metropolitan City of Florence, and Pratovecchio-Stia, Poppi, Bibbiena, and Chiusi della Verna are a part of the Province of Arezzo. The municipalities of the Romagna—Bagno di Romagna, Santa Sofia, Premilcuore, Portico e San Benedetto, and TredozioFootnote6—lie in the Province of Forlì-Cesena.

Physical-geographical setting

The Foreste Casentinesi National Park spans both sides of the Northern Apennines’ main ridge formed by sedimentary rocks, mainly sandstone and marl (Cavagna & Cian, Citation2003; Rother & Tichy, Citation2008). While the southwestern slopes are relatively smooth, the northeastern side’s relief is rather steep and rugged. According to Rubel, Brugger, Haslinger, and Auer (Citation2017), the vast majority of the park has a Cfb climate, that is, a warm temperate climate without a dry season but with warm summers (Köppen-Geiger climate classification; HISTALP data from 1986–2010). The area of the park, almost entirely covered by Natura 2000 sites at present, ranges from approximately 400 m asl up to the Monte Falco (1658 m asl). Consequently, different vegetation zones—similar to the southern European Alps (Franz, Citation1979)—can be divided (Viciani & Agostini, Citation2008): a colline zone up to approximately 600 m asl (4.5% of the park area), the lower (600–800 m asl; 26%) and upper submontane belt (800–1000 m asl; 37%), as well as the lower (1000–1400 m asl; 30%) and upper montane region asl (above 1400 m asl; 2.5%). While the colline and submontane areas are characterised by oaks (Quercus cerris), hop hornbeams (Ostrya carpinifolia), and sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa), the montane zones are typically covered by beech forests (Fagus sylvatica). Apart from deciduous trees, areas with plantations of evergreen trees (e.g. Abies spp., Pinus spp., or Picea spp.)—most famously the white spruce (Abies alba) forest created by the monks of Camaldoli (Pungetti, Hughes, & Rackham, Citation2012)—as well as grassland and shrubland can be found in the park. As indicated in the management plan of the park, grasslands used as meadows include Dactylis glomerata, whereas in pastures Bromus erectus and Cynosurus cristatus are found. Once the abandonment process starts, diffusion of Brachypodium pinnatum often occurs, and pioneer species such as the deciduous and simple-leaved Spanish broom (Spartium junceum) increasingly colonise the extensively used grasslands (Parco Nazionale delle Foreste Casentinesi, Monte Falterona e Campigna, Citation2002b, pp. 23–24).

Social transformations and population dynamics

The shift from grassland to wood or shrubland () is often linked with social transformations and population dynamics.Footnote7 In an overview of the Italian Apennines, Rother and Wallbaum (Citation1975) found a slight decrease in depopulation in the Northern Apennines during 1961–1971, with exceptions in Liguria. Differences between the Tuscan and Emilian-Romagnan slopes were not observed. Depopulation in selected Emilian-Romagnan municipalities of today’s national park (Premilcuore and Portico e San Benedetto) was studied in detail by Kühne (Citation1974) during 1966–1969. He revealed that outmigration in the 1960s—mainly to large cities such as Florence, Forlì, or Milan—primarily affected scattered buildings of poderi and led to the abandonment of these isolated farmsteads; a tendency Kühne saw in the context of the area’s mezzadria or sharecropping system. Since the 1980s, certain differences between both regions of today’s national park municipalities emerged: the Emilian-Romagnan municipalities registered decreasing or—at best—stagnating population, whereas population increase was registered by Tuscan municipalities. From 1981 to 2011 (), Portico e San Benedetto, Premilcuore, and Tredozio lost more than 20% of their population; San Godenzo, Poppi, Bibbiena, and Londa, in turn, showed population gains between 6% and 68%. The latter value was clearly driven by suburbanisation and/or postsuburbanisation processes (on differences see Borsdorf, Citation2005) in the metropolitan area of Florence.

Table 1. Population changes in the municipalities of the Foreste Casentinesi National Park. The formerly separated municipalities of Pratovecchio and Stia form the Comune di Pratovecchio Stia since 2014. Source: Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (Citation1981, Citation1991, Citation2001, Citation2011) and author’s calculations.

Data acquisition

To analyse land cover changes using Geographic Information System (GIS), remotely sensed data were used, especially satellite imagery—sharped 432-RGB composites of Landsat TM scenes (30 m resolution) from 1990 (July 20), 2001 (July 26), and 2010 (July 3)—and a digital elevation model (Aster GDEM; 30 m resolution). Training samples for classification were produced by combining purposive GPS measurements on site in the municipalities of Poppi (Tuscany) and Bagno di Romagna (Emilia-Romagna) in September 2016. Random sample points (373) were created for assessing the accuracy of classification using satellite imagery (very high resolution; acquired on 29 August 2014) in the free virtual globe software Google Earth. Although the use of imagery via Google Earth has several limitations (e.g. temporal, spatial, and spectral metadata cannot always be found), the quality of data is considered sufficient for a range of practice-oriented research and mapping exercises (see for instance Potere, Citation2008). Very high-resolution imagery from Google Earth (acquired on 29 August 2014) was also used to map abandoned farmsteads in the study area.

Data processing

Land cover change and settlement mapping

Each of the three Landsat TM composites was classified into ‘wood or shrubland’, ‘grassland’, or ‘other’—always applying the same process. To assess the accuracy of the 2010 classification, we compared it with a set of reference points in a so-called error matrix. Three hundred reference points were created randomly using very high-resolution imagery from 2014. The vast majority (273) of points were on ‘wood or shrubland’. To achieve at least 50 references per class—and to comply with the rule of thumb of Congalton (Citation1991)—we purposively sampled additional points for ‘grassland’ (35) and ‘other’ (38) to include the most characteristic sites. Because Pontius and Millones (Citation2011) have reported that Cohen’s Kappa coefficient of agreement and many other Kappa indices are mostly not suitable for practical applications in remote sensing, Cohen’s Kappa coefficient of agreement was not calculated. Instead, quantity disagreement and allocation disagreement were calculated.

Because the 1990 and 2001 images were acquired by the same sensor in the same month, and processed identically, we assumed that the accuracy of classifications from 1990 and 2001 was comparable to the 2010 image. Finally, a cross-tabulation matrix was calculated (following Pontius, Shusas, & McEachern, Citation2004) and land cover change trajectories for 1990–2001–2010 were analysed using pixel-wise comparison, and then visualised and interpreted.

Abandoned settlements visible on very high-resolution images were manually digitised. As abandonment cannot be visually detected, we manually searched and digitised all single buildings that clearly had no complete roof (either a damaged roof or none at all) at a view height of 800 m. Groups of buildings were joined and counted as one settlement (the location of the largest building was mapped). The location information of the abandoned buildings, imported into the GIS as kml files, was complemented by the trajectory of the site’s land cover change (the respective 30 × 30 m pixel was considered).

Classification accuracy assessment

On the basis of the 373 reference points, the percentage of correctly allocated pixels reached 87.13% (). The majority of classes had individual producer and user accuracy valuesFootnote8 of 73% or more. The only exception was the user accuracy value of ‘grassland’, 60.66% possibly because of the fuzzy border between ‘grassland’ with incipient shrub encroachment and ‘wood or shrubland’ proper. In sum, the accuracy targets set by Thomlinson, Bolstad, and Cohen (Citation1999), more than 85% correctly allocated pixels with no individual class below 75% can be considered almost achieved for the 2010 classification. Allocation disagreement showed somewhat higher values than quantity disagreement.Footnote9

Table 2. Accuracy assessment of the 2010 land cover classification on the basis of 373 reference points from 2014 very high-resolution imagery. Changes between grassland (GRL), wood or shrubland (WSL), and other are shown.

Results and discussion

Land cover and change trajectories

The results show that 67% of today’s park area was covered by wood or shrubland in 1990. At the same time, grassland covered 30%, and all other land cover types together made up only 3% of the study area. In 2001, in turn, the situation changed: wood or shrubland covered approximately 84% and grassland decreased to only 13%, whereas other land cover types did not show large changes. This implies that grassland areas were more than halved within a period of only 11 years. The situation in 2010 shows a distribution similar to that in 2001: 83% covered by wood or shrubland, 13% by grassland, and other land cover by 4%.

Land cover changes 1990–2001 and 2001–2010

The results presented in indicate that net land cover changes during 1990–2001 were less than 17%. On comparing gains and losses per category, it becomes clear that swaps—equal transitions between two categories—make up approximately 2%, and thus a total change of little more than 19%. This implies that approximately 81% of the park’s area were persistent between 1990 and 2001. Subsequently, during 2001–2010, the park’s land cover showed even higher rates of persistency (approximately 92%), whereas swaps amounted to 7%; net changes only reached a value of 1% of the park’s area. A closer look on grassland reveals that this category gained 1% but lost 18% of the park’s area during 1990–2001. Between 2001 and 2010, however, the amount of grassland gained was almost equal to that of grassland lost, resulting in a total change of 7.5%. In this context, it is astonishing that net changes within the grassland category are even smaller than those in the category of ‘other’. These figures convey the impression that—regarding the total land cover structure—conservation was highly effective between 1990 and 2010 (high rates of persistency). Moreover, the land cover trajectories seem to confirm the attitudinal change from ‘wilderness only’ (net change from grassland to wood or shrubland during 1990–2001) to a consciousness for conserving the remaining grasslands (swaps between grassland and wood or shrubland during 2001–2010). Yet the question of whether these changes are systematic and dominant remains.

Table 3. Portions and changes of land cover classes 1990–2001 and 2001–2011 in the Foreste Casentinesi National Park (in percent of the total area of 408,998 pixel).

Systematic and random changes

Under random processes of gain or loss, the distribution of the total gains or losses would be expected to correlate with the respective categories’ share in the total area. Hence, by subtracting the expected values from the observed transitions between categories, we can identify and interpret systematic changes (values not equal to zero) and random changes (values equal to zero). In addition, values very close to zero—those between 0.1% and −0.1%—are also considered nonsystematic changes.

In terms of gains (1990–2001; ), the observed transition from grassland to wood or shrubland shows a difference of 1.56% between observed and expected changes. Hence, when wood or shrubland gains, it systematically replaces grassland. The observed changes from wood or shrubland to grassland (0.05%) equal the expected values, and thus are not systematic. In terms of losses (1990–2001; ), the value of observed transitions from grassland to wood or shrubland is higher than expected (difference of 0.27%), indicating that, when grassland loses, it is systematically replaced by wood or shrubland, and wood or shrubland gains. Regarding transitions from wood or shrubland to grassland, a difference of 0.22% indicates a systematic change. Following Alo and Pontius (Citation2004) and Braimoh (Citation2006), the transitions from grassland to wood or shrubland are the dominantFootnote10 changes.

Table 4. Land cover change during 1990–2001 and 2001–2011 (in percent of the total area of 408,998 pixel). Bold figures represent the observed values, and figures in italics show the difference between observed and expected values in terms of gains and losses.

For 2001–2010, in terms of gains (2001–2010; ), we see systematic changes for transitions from grassland to wood or shrubland (difference of 0.7%), indicating that, when wood or shrubland gains, it systematically replaces grassland. In addition, transitions from wood or shrubland to grassland (2001–2010) seem to be systematic (difference of 0.15%), thus when grassland gains, it tends to replace wood or shrubland. In terms of losses (), the observed transition from grassland to wood or shrubland almost equals the expected value; thus, no systematic change exists. For transitions from wood or shrubland to grassland, in turn, there is a difference of 0.43%, implying that, when wood or shrubland loses, it is systematically replaced by grassland. According to Alo and Pontius (Citation2004) and Braimoh (Citation2006), the changes from grassland to wood or shrubland were no longer dominant during 2001–2010. Instead, transitions from wood or shrubland to grassland were dominant.

Disappeared and existent grasslands

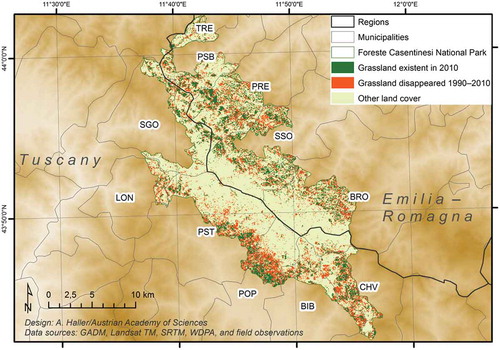

The areas of grassland cover lost during 1990–2010 are shown in . It becomes clear that the decrease of grasslands occurred in both Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna. Moreover, altitudinal differences can be observed as the majority of disappeared grasslands are almost homogeneously distributed in the lower parts of the park. This is no surprise because in 1990 around 85% of grasslands were below 1000 m asl (with 78% in the submontane zones), whereas only 15% were in the montane zones: 8598 pixel in the colline zone (covering 49% of this altitudinal zone), 45,791 pixel in the lower submontane zone (covering 43%), 50,739 pixel in the upper submontane zone (covering 33%), 17,297 pixel in the lower montane zone (covering 14%), and 572 pixel in the upper montane zone (covering 6%). The altitudinal distribution of disappeared grassland illustrated in shows that 77% of grassland areas lost between 1990 and 2010 were in the submontane zones (which cover 63% of the park), with a peak at the limit between the lower and upper submontane areas (800 m asl). Thus, while the distribution of grassland in 1990 clearly tends toward the submontane zone—obviously because the Emilian-Romagnan grasslands are on mountains that hardly surpass heights of 1000 m asl—grassland loss during 1990–2010 within this zone occurs quite randomly—a fact that underlines the clear dominance of natural wood or shrubland expansion (‘rewilding’) in comparison with human-induced reforestation.

Figure 3. Grasslands in the Foreste Casentinesi National Park. The municipalities of Bagno di Romagna (BRO), Portico e San Benedetto (PSB), Premilcuore (PRE), Santa Sofia (SSO), Tredozio (TRE), Bibbiena (BIB), Chiusi della Verna (CHV), Pratovecchio-Stia (PST), Poppi (POP), Londa (LON), and San Godenzo (SGO) are indicated.

Figure 4. Altitudinal distribution of grassland areas that disappeared during 1990–2010. The highest values are found in the submontane zone (600–1000 m asl), which covers 63% of the park, and where 77% of the park disappeared and 81% of the park’s 2010 grassland is located. Source: Authors’ calculation.

With respect to grasslands existent in 2010, the areas shown in indicate that large patches of 2010 grasslands appear particularly in the municipalities of Portico e San Benedetto, Premilcuore, and Santa Sofia (Emilia-Romagna); Tuscan municipalities with large patches of 2010 grassland were Pratovecchio-Stia, Poppi, and Chiusi della Verna. The fact that 2010 grassland areas of the Tuscan part are mainly at the edge of the park while the Emilian-Romagnan patches tend to be at a greater distance from the park’s border can be explained by the different types of relief on both parts of the Apennine ridge—and does not necessarily mean differences in the altitudinal distribution of 2010 grassland areas. In 2010, around 88% of grassland was below 1000 m asl (with 81% in the submontane zones), whereas only 12% were in the montane zones (): 3620 pixel in the colline zone (covering 21% of this altitudinal zone), 20,906 pixel in the lower submontane zone (covering 20%), 23,066 pixel in the upper submontane zone (covering 15%), 6566 pixel in the lower montane zone (covering 5%), and 174 pixel in the upper montane zone (covering 2%).

In summary, grassland areas in the total park area decreased by 57% between 1990 and 2010. The colline zone also lost 57% of its grasslands, and grassland areas in the lower and upper submontane belt decreased by 53% and 55%, respectively. In contrast, the lower and upper montane zones show values clearly above the total average: 64% and 67%, respectively. The decrease of grassland above 1100 m asl is evident (see ); further concentration of grassland areas at the submontane zones occurred.

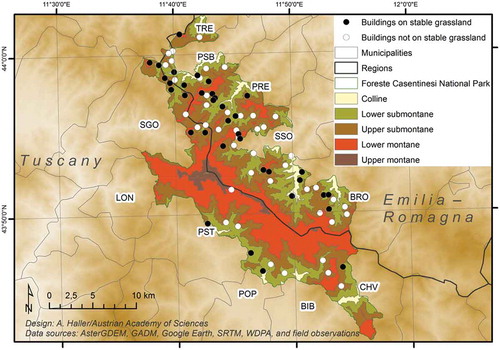

Abandoned settlements on stable grassland

According to the prominent school of landscape studies identified with the cultural geography of the University of California, Berkeley, and geographer Carl Sauer, grasslands are understood as a spatial manifestation of a nature/culture gestalt or whole (Gade, Citation2011). From this ‘Sauerian’ perspective, which draws on both American and European sources, we regard grassland maintenance/restoration as including the rural built heritage. If, however, grasslands are simply seen as habitat areas where the vegetation is dominated by grasses, we would expect a significant number of abandoned settlements (buildings with either a damaged roof or none at all) on stable grassland.

We identified 81 abandoned settlements on very high-resolution imagery from 2014, of which 44 were found on 2010 grassland. They were equally distributed between the lower (20 settlements) and upper submontane zone (21 settlements each); only three settlements were located in the lower montane zone. By interpreting the selected settlements against the respective trajectory of land cover change (1990–2001–2011), we found 36 abandoned settlements on stable grasslandFootnote11 (). These abandoned settlements were located in the lower submontane zone (18 settlements), the upper submontane (16), and slightly above 1000 m asl in the lower montane zone (2).

Figure 5. Abandoned settlements (2014) on stable/not on stable grassland are indicated. The municipalities of Bagno di Romagna (BRO), Portico e San Benedetto (PSB), Premilcuore (PRE), Santa Sofia (SSO), Tredozio (TRE), Bibbiena (BIB), Chiusi della Verna (CHV), Pratovecchio-Stia (PST), Poppi (POP), Londa (LON), and San Godenzo (SGO) are indicated.

While the quantitative results of land cover change clearly show the effectiveness of the park authorities’ efforts to maintain/restore grasslands since the new millennium—although the inclusion of mountain communities in general, and breeders in particular, remains a challenge (see Acciaioli, Tellini Florenzano, & Parrini, Citation2014)—the motive behind these attitudinal changes, which developed during the 1990s, seems to be clearly driven by the EU Habitats Directive’s aim of conserving biodiversity. As the many abandoned settlements on stable grassland indicate (), cultural-historical motives clearly play a minor or even no role. The Agenzia Regionale per lo Sviluppo e l’Innovazione nel Settore Agricolo-Forestale of the regional government of Tuscany, for instance, has edited a helpful manual on Northern Apennine grassland management (ARSIA, Citation2010), which clearly considers pasturing a biodiversity conservation instrument:

‘Human activities are not always conflicting with biodiversity—quite the contrary. Human activities, such as certain forms of agriculture, forestry, or livestock farming, have contributed, and still contribute, to the maintenance of very high biodiversity values […], because human actions maintain varied (diversified) landscapes in which many species can live together.’ (Tellini Florenzano & Campedelli, Citation2010, p. 9; translated from Italian by the authors).

Figure 6. Abandoned settlement at the Romiti plain (now property of the Foreste Casentinesi National Park). Photo: Andreas Haller (2017).

Grasslands are seen as spaces of biodiversity. Thus, there is still a potential to better integrate the conservation of biodiversity and the cultural-historical heritage in the sense of the European Landscape Convention (see Sarmiento, Bernbaum, Brown, Lennon, & Feary, Citation2014; Seardo, Citation2016). In this context, it is crucial to recognise the dynamic nature and the increasing complexity of the social-ecological grassland systems in mountains (see Scolozzi, Soane, & Gretter, Citation2014). Regarding the rural built heritage in the park, the 2002 management plan of the National Park already underlines that

‘[s]pecial attention must be paid to the restoration of those buildings not permanently inhabited […]. In particular, more attention has to be paid in case these buildings are disused, not connected to the municipal, provincial, or national road system, and without supply of public services (power, gas water, telephone, etc.).’ (Parco Nazionale delle Foreste Casentinesi, Monte Falterona e Campigna, Citation2002b, p. 110; translated from Italian by the authors).

Given that montane grasslands are more affected than submontane grassland areas, and considering the diversity of the ecotone between the submontane forest and the beech-dominated montane zone—from both an ecological and an aesthetic point of view—abandoned farmsteads and grasslands at approximately 1000 m asl are particularly suitable to integrate the successful efforts of biodiversity conservation with those of restoring the rural built heritage, raising awareness of the importance of the past for a sustainable present and future. Ongoing artistic projects, such as the Le Valli project (www.progettolevalli.org) started in 2011 by the Florence-based artist Andrea Papi, are already contributing to the restoration and valorisation of the rural built heritage in the mountains of San Godenzo, for instance by creating a Sentiero dell’architettura rurale (a ‘trail of rural architecture’). Moreover, the Popoli del Parco project (www.popolidelparco.it)—an initiative of the Foreste Casentinesi National Park—launched a website in 2017, raising awareness for local landscape history by making photo archives and video interviews with contemporary witnesses accessible online. Such signposted landscape trails and web-based communication tools (see Jones, Citation2007) are definitely a step in the right direction.

Conclusions

The case study in the Foreste Casentinesi National Park clearly shows that attitudinal changes are reflected by the land cover. While the growth of wood or shrubland dominated between 1990 and 2001, efforts to maintain/restore grasslands are visible in the period 2001–2010. This research comes to the conclusion that the maintenance/restoration of grasslands among rewilding mountains is primarily driven by the aim of conserving biodiversity—and not at all by the desire to conserve the spatial manifestation of the nature/culture gestalt in a Sauerian understanding. Grazing is now considered an instrument to maintain/restore grasslands as spaces of biodiversity. Abandoned settlements—ruins of former poderi—surrounded by stable grassland are impressive witnesses of the disregarding of grasslands as valuable places shaped by human presence during centuries.

The rich biodiversity of grasslands once was the result of agricultural activities, yet today the maintenance/restoration of grasslands depends on biodiversity conservation. The strengthening of the linkages between biodiversity conservation and grassland maintenance/restoration (including the rural built heritage), is not only an opportunity but probably the only feasible way to conserve these unique places in the long term.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Stiftung der Familie Philip Politzer foundation. The authors are grateful to the anonymous reviewers and to guest editors Kenneth R. Olwig and Werner Kraus.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. This fact obviously refers to permanent outmigration. For the 18th, 19th, and early 20th century, it is well documented that people of the Northern Apennines—predominantly in areas with the custom of partible inheritance (Sabelberg, Citation1975)—outmigrated temporarily in search for work and income, leaving their villages half-abandoned. Examples include the Lucchese figure makers, and Pistoiese woodcutters and charcoal burners (Sarti, Citation1985; for further reading see Tagliasacchi, Citation1990; Arrigoni, Citation2002).

2. According to Zullo, Paolinelli, Fiordigigli, Fiorini, and Romano (Citation2015, p. 190), urban settlement areas in Tuscany expanded by 6 ha/day since the 1950s, implying an increase of 550% until 2007. The increase in the Emilia-Romagna is quite similar (510%).

3. The aim of conserving wilderness areas, originally understood as land cover structure in its natural state—thus without signs of human work—can, above all, be considered an American idea (Nash, Citation2001). It began in the 1920s (Scott, Citation2002) and is strongly linked with the name of Aldo Leopold and his seminal article on The Wilderness and Its Place in Forest Recreation Policy (Leopold, Citation1921).

4. A good example is the pasture of San Paolo in Alpe (Santa Sofia). Argenti et al. (Citation2006) revealed a decrease of grassland (class denominated pascoli [meaning ‘pastures’] in their study) by 54% during 1955–1997 from 151 ha via 111 ha (1976) to 70 ha. During the same time, wood or shrubland (classes denominated by boschi di latifoglie or ‘broad-leaved forests,’ boschi di conifere or ‘needle-leaved forests,’ and arbusteti or ‘shrubland’) increased from 0 ha via 82 ha to 123 ha.

5. The mezzadria system characterised large parts of Central Italy. The system developed in the 13th/14th century when the landlords were often forced to resettle in a town or city (Braunfels, Citation1963) and to administrate their lands from a so-called fattoria (large farmstead), which coordinated the several poderi (small farmsteads) managed by sharecroppers (mezzadri). Simply put, the landlords provided the land, the farmers provided their workforce, and the capital provision was shared between both (Sabelberg, Citation1975). The expansion of the mezzadria system in the Tuscan Apennines—once concentrated on the plains and hilly areas—was particularly boosted under the rule of the house of Habsburg-Lorraine (approximately 1765–1860), which carried out a number of social and economic reforms in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany (on these issues see Giorgetti, Citation1968; Gori-Montanelli, Citation1964; Sabbatini, Citation1999).

6. These municipalities belong to the historic region of the ‘Romagna toscana’ and were part of Tuscany until the 1920s.

7. Apart from natural regrowth, these processes also included planned afforestation of grassland. In the Tuscan Apennines, for example, many grassland areas were afforested between 1945 and the 1960s, mostly with needle-leaved species such as Pinus radiata or Pseudotsuga douglasii (Müller-Hohenstein, Citation1969, p. 156).

8. The user’s accuracy refers to the erroneous inclusion of a site in a category, whereas the producer’s accuracy indicates the error of not including a site in a given category.

9. According to Pontius and Millones (Citation2011, p. 4409), allocation disagreement ‘is due to the less than optimal match in the spatial allocation of the categories’ while quantity disagreement is ‘due to the less than perfect match in the proportion of the categories’.

10. Alo and Pontius (Citation2004, p. 12) state that a ‘systematic gain and systematic loss in a particular transition will then confirm a strong signal of the process of change. In other words, if a category of 1990 has systematically lost to a category of 2000, and that 2000 category has also systematically gained from the same 1990 category, then we can conclude a systematic process of transition between the two categories’. Braimoh (Citation2006) calls this a ‘dominant’ process.

11. In this context, ‘stable grassland’ does not mean that there was no shrub encroachment on these lands during 1990–2010 nor does it automatically mean that these grasslands were used as pastures, as only the land cover at three selected points in time was analysed.

References

- Acciaioli, A., Tellini Florenzano, G., & Parrini, S. (2014). Il paesaggio agro-zootecnico e silvo-pastorale dell’Appennino settentrionale. In B. Ronchi, G. Pulina, & M. Ramanzin (editors), Il paesaggio zootecnico italiano (pp. 77–96). Milan, Italy: FrancoAngeli.

- Agnoletti, M. (2014). Rural landscape, nature conservation and culture: Some notes on research trends and management approaches from a (southern) European perspective. Landscape and Urban Planning, 126, 66–73.

- Alo, C. A., & Pontius, R. G. (2004). Detecting the influence of protection on landscape transformation in southwestern Ghana. In: H. T. Mowrer, R. E. McRoberts, & P. C. Van Deusen, editors. Proceedings of the joint meeting of the 6th International Symposium On Spatial Accuracy Assessment in Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences and the 15th Annual Conference of The International Environmetrics Society. Portland, ME: ISARA, 1–17.

- Argenti, G., Bianchetto, E., Ferretti, F., Giulietti, V., Milandri, M., Pelleri, F., … Venturi, E. (2006). Characterization of an abandoned pastoral area in the Northern Apennines, Italy. Forest@, 3, 387–396.

- Arrigoni, T. (2002). Uomini dei boschi e della natura. Emigrazione stagionale dall’Appennino toscano alla Corsica (XVIII-XX secolo). Pisa, Italy: Pacini Editore.

- ARSIA. (2010). La gestione e il recupero delle praterie dell’Appennino settentrionale. Il pascolamento come strumento di tutela e salvaguarda della biodiversità. editors Florence, Italy: Regione Toscana.

- Bender, O., & Haller, A. (2017). The cultural embeddedness of population mobility in the Alps: Consequences for sustainable development. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography, 71(3), 132–145.

- Borsdorf, A. (2005). Introduction: Évolutions postsuburbaines en Europe et dans le Nouveau Monde. Revue Géographique De l’Est, 45(3–4), 125–132.

- Braimoh, A. K. (2006). Random and systematic land-cover transitions in northern Ghana. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 113(1–4), 254–263.

- Braunfels, W. (1963). Stadtgedanke und Stadtbaukunst im Widerstreit von Guelfen und Ghibellinen im italienischen Mittelalter. Studium Generale, 16(8), 488–492.

- Cavagna, S., & Cian, S. (2003). The National Park of the Casentine Forests. Florence, Italy: Giunti Editore.

- Congalton, R. G. (1991). A review of assessing the accuracy of classifications of remotely sensed data. Remote Sensing of Environment, 37(1), 254–263.

- D’Angelo, P. (2016). Agriculture and landscape. From cultivated fields to the wilderness, and back. J-READING, 1(5), 47–56.

- Dossche, R., Rogge, E., & Van Eetvelde, V. (2016). Detecting people’s and landscape’s identity in a changing mountain landscape. An example from the northern Apennines. Landscape Research, 41(8), 934–949.

- Falcucci, A., Maiorano, L., & Boitani, L. (2007). Changes in land-use/land-cover patterns in Italy and their implications for biodiversity conservation. Landscape Ecology, 22(4), 617–631.

- Farina, A. (1995). Upland farming systems of the Northern Apennines. In P. Halladay & G. Da (editors), Conserving biodiversity outside protected areas. The role of traditional agro-ecosystems (pp. 123–135). Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- Farina, A. (2006). Principles and methods in landscape ecology. Towards a science of the landscape. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

- Franz, H. (1979). Ökologie der Hochgebirge. Stuttgart, Germany: Ulmer.

- Gade, D. W. (1999). Nature and culture in the Andes. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Gade, D. W. (2011). Curiosity, inquiry and the geographical imagination. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Gambino, R., & Romano, B. (2003). Territorial strategies and environmental continuity in mountain systems: The case of the Apennines (Italy). In IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas (editors), Linking protected areas along the mountain range. 5th World Park Congress (pp. 1–16). Durban, South Africa: IUCN.

- Giorgetti, G. (1968). Agricoltura e sviluppo capitalistico nella Toscana del ‘700. Studi Storici, 9(3–4), 742–783. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20562955

- Gori-Montanelli, L. (1964). Architettura rurale in Toscana. Florence, Italy: Edam Editrice.

- Istituto Nazionale di Statistica. (1981). XII censimento generale della popolazione e delle abitazioni. Rome, Italy: Istat.

- Istituto Nazionale di Statistica. (1991). XIII censimento generale della popolazione e delle abitazioni. Rome, Italy: Istat.

- Istituto Nazionale di Statistica. (2001). XIV censimento generale della popolazione e delle abitazioni. Rome, Italy: Istat.

- Istituto Nazionale di Statistica. (2011). XV censimento generale della popolazione e delle abitazioni. Rome, Italy: Istat.

- Jones, M. (2007). The European Landscape Convention and the question of public participation. Landscape Research, 32(5), 613–633.

- Jones, M., Howard, P., Olwig, K. R., Primdahl, J., & Sarlöv Herlin, I. (2007). Multiple interfaces of the European Landscape Convention. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography, 61(4), 207–216.

- Kühne, I. (1974). Die Gebirgsentvölkerung im nördlichen und mittleren Apennin in der Zeit nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten Sonderband 1. Erlangen, Germany: Palm und Enke Verlag.

- Leopold, A. (1921). The wilderness and its place in forest recreation policy. Journal of Forestry, 19(7), 718–721.

- MacDonald, D., Crabtree, J. R., Wiesinger, G., Dax, T., Stamou, N., Fleury, P., … Gibon, A. (2000). Agricultural abandonment in mountain areas of Europe: Environmental consequences and policy response. Journal of Environmental Management, 59(1), 47–69.

- Ministerio dell’Ambiente. (1990). Decreto Ministeriale 14 dicembre 1990 - Perimetrazione provvisoria e misure provvisorie di salvaguardia del parco nazionale del Monte Falterona, Campigna e delle Foreste Casentinesi (G.U. 11 gennaio 1991, n. 9). Rome, Italy: Author.

- Ministerio dell’Ambiente. (1993). D.P.R. 12 luglio 1993 - Istituzione dell’Ente parco nazionale delle Foreste Casentinesi (G.U. Serie Generale 10 agosto 1993, n. 186). Rome, Italy: Author.

- Müller-Hohenstein, K. (1969). Die Wälder der Toskana. Ökologische Grundlagen, Verbreitung, Zusammensetzung und Nutzung. Erlangen, Germany: Palm und Enke Verlag.

- Nash, R. (2001). Wilderness and the American mind. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Olwig, K. R. (1996). Recovering the substantive nature of landscape. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 86(4), 630–653.

- Olwig, K. R. (2007). The practice of landscape ‘conventions’ and the just landscape: The case of the European Landscape Convention. Landscape Research, 32(5), 579–594.

- Papanastasis, V. P. (2012). Land use changes. In I. N. Vogiatzakis (editor), Mediterranean mountain environments (pp. 159–184). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Parco Nazionale delle Foreste Casentinesi, Monte Falterona e Campigna. (2002a). Piano del parco. Allegato 2: Agricoltura e paesaggio. Pratovecchio, Italy: Author.

- Parco Nazionale delle Foreste Casentinesi, Monte Falterona e Campigna. (2002b). Piano del parco. Relazione generale. Pratovecchio, Italy: Author.

- Parco Nazionale delle Foreste Casentinesi, Monte Falterona e Campigna. (2013). Un progetto per la conservazione delle aree aperte. Press release published on November 19. Pratovecchio, Italy: Author.

- Pontius, R. G., & Millones, M. (2011). Death to Kappa: Birth of quantity disagreement and allocation disagreement for accuracy assessment. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 32(15), 4407–4429.

- Pontius, R. G., Shusas, E., & McEachern, M. (2004). Detecting important categorical land changes while accounting for persistence. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 101(2–3), 251–268.

- Potere, D. (2008). Horizontal positional accuracy of Google Earth’s high-resolution imagery archive. Sensors, 8(12), 7973–7981.

- Pungetti, G., Hughes, P., & Rackham, O. (2012). Ecological and spiritual values of landscape. In G. Pungetti, G. Oviedo, & D. Hooke (editors), Sacred species and sites: Advances in biocultural conservation (pp. 65–82). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

- Rother, K., & Tichy, F. (2008). Italien. Geographie, Geschichte, Wirtschaft, Politik. Darmstadt, Germany: WBG.

- Rother, K., & Wallbaum, U. (1975). Die Entvölkerung des Apennins 1961–1971. Eine Kartenerläuterung. Erdkunde, 29(3), 209–213.

- Rubel, F., Brugger, K., Haslinger, K., & Auer, I. (2017). The climate of the European Alps: Shift of very high resolution Köppen-Geiger climate zones 1800–2100. Meteorologische Zeitschrift, 26(2), 115–125.

- Sabbatini, R. (1999). Risorse produttive e imprenditorialità nell’Appennino tosco-emiliano (XVII-XIX secolo). In A. Leonardi & A. Bonoldi (editors), L’economia della montagna interna italiana: Un approccio storiografico (pp. 18–49). Trento, Italy: Università degli Studi di Trento.

- Sabelberg, E. (1975). Der Zerfall der Mezzadria in der Toskana Urbana. Entstehung, Bedeutung und gegenwärtige Auflösung eines agraren Betriebssystems in Mittelitalien. Cologne: Geographisches Institut der Universität Köln im Selbstverlag.

- Sangiorgi, F. (2008). The vernacular rural heritage. Futuropa, 1, 4–6.

- Sarmiento, F. O., Bernbaum, E., Brown, J., Lennon, J., & Feary, S. (2014). Managing cultural features and uses. In G. L. Worboys, M. Lockwood, A. Kothari, S. Feary, & I. Pulsford (editors), Protected area governance and management (pp. 685–714). Canberra, Australia: ANU Press.

- Sarti, R. (1985). Long live the strong: A history of rural society in the Apennine mountains. Amherst, MA: The University of Massachusetts Press.

- Scolozzi, R., Soane, I. D., & Gretter, A. (2014). Multiple-level governance is needed in the social-ecological system of Alpine cultural landscapes. In F. Padt, P. Opdam, N. Polman, & C. Termeer (editors), Scale-sensitive governance of the environment (pp. 90–105). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Scott, D. W. (2002). “Untrammeled,” “wilderness character,” and the challenges of wilderness conservation. Wild Earth, 11(3–4), 72–79.

- Seardo, B. M. (2016). Convention on Biological Diversity and European Landscape Convention: An alliance for biocultural diversity?. In M. Agnoletti & F. Emanueli (editors), Biocultural diversity in Europe (pp. 511–522). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Tagliasacchi, P. (1990). Coreglia Antelminelli: Patria del figurinaio. Coreglia Antelminelli, Italy: Comune di Coreglia Antelminelli.

- Tellini Florenzano, G. (1999). Gli uccelli delle Foreste Casentinesi. Versione redotta. Florence, Italy: Regione Toscana.

- Tellini Florenzano, G., & Campedelli, T. (2010). Introduzione. In ARSIA (editors), La gestione e il recupero delle praterie dell’Appennino settentrionale. Il pascolamento come strumento di tutela e salvaguarda della biodiversità (pp. 9–10). Florence, Italy: Regione Toscana.

- Thomlinson, J. R., Bolstad, P. V., & Cohen, W. B. (1999). Coordinating methodologies for scaling landcover classifications from site-specific to global: Steps toward validating global map products. Remote Sensing of Environment, 70(1), 16–28.

- Toniolo, A. R. (1937). Studies of depopulation in the mountains of Italy. Geographical Review, 27(3), 473–477. http://www.jstor.org/stable/210332

- Torta, G. (2004). Consequences of rural abandonment in a Northern Apennines landscape (Tuscany, Italy). In S. Mazzoleni, G. Di Pasquale, M. Mulligan, P. Di Martino, & F. Rego (editors), Recent dynamics of the Mediterranean vegetation and landscape (pp. 157–165). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Vecchio, B. (1989). Geografia degli abbandoni rurali. In P. Bevilacqua (editor), Storia dell’agricoltura italiana in età contemporanea. Spazi e paesaggi (pp. 319–351). Venice, Italy: Marsilio Editori.

- Vicente-Serrano, Y. F., Lasanta, T., & Cuadrat, J. M. (2000). Transformaciones en el paisaje del Pirineo como consecuencia del abandono de las actividades económicas tradicionales. Pirineos, 155, 111–133.

- Viciani, D., & Agostini, N. (2008). La carta della vegetazione del Parco Nazionale delle. Foreste Casentinesi, Monte Falterona e Campigna (Appennino Tosco-Romagnolo): Note illustrative. Quaderno Di Studi E Notizie Di Storia Naturale Della Romagna, 27, 97–134.

- Vogiatzakis, I. N. (2012). Introduction to the Mediterranean mountain environments. In I. N. Vogiatzakis (editor), Mediterranean mountain environments (pp. 1–10). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Vos, W. (1993). Recent landscape transformation in the Tuscan Apennines caused by changing land use. Landscape and Urban Planning, 24(1–4), 63–68.

- Zimmerer, K. S., Galt, R. E., & Buck, M. V. (2004). Globalization and multi-spatial trends in the coverage of protected-area conservation (1980–2000). AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 33(8), 520–529.

- Zullo, F., Paolinelli, G., Fiordigigli, V., Fiorini, L., & Romano, B. (2015). Urban development in Tuscany. Land uptake and landscapes changes. TeMA, 8(2), 183–202.

- Zunino, W. (1995). The wilderness movement in Italy. A wilderness model for Europe. International Journal of Wilderness, 1(2), 41–42.