ABSTRACT

According to the European Landscape Convention landscape means an area, as perceived by people, whose character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors. The meaning of landscape depends on how people perceive and, in turn, interpret a landscape, which, in a circular way, effects again how people perceive the landscape. Perception thereby involves both the sensing of landscape and the constituting of the landscape that one senses. This article counterpoises the perception of landscape as a body of land generated by the enclosure of common land and the perception generated through the use of unenclosed common land by a body of people, and the concomitantly differing perceptions of the nature of the relation between the natural and the human. It will make the distinction drawing upon the case of England’s ‘Lake District’ as perceived in the context of a suggested North Atlantic archipelago.

Introduction

This article proposes that the English ‘Lake District’ might be perceived to have at least two different somewhat opposed landscapes. The one derives from its position in relation to the English core area, with its intensive, enclosed agriculture and industrial, urban society and the other from its historic links within a relatively unenclosed, extensively farmed North Atlantic ‘archipelagic’ area. The hypothesis is not that there are two differing perceptions of the same landscape, but two separate landscapes, each the product of differing modes of perception, associated with differing conceptions of legal rights, landscape representation, moral habitus, economy, land, space and ownership. The opposition lies in the one being rooted in enclosed, individually owned, private property whereas the other is rooted in ideas and practices involving shared common land. The rise of the enclosure movement, along with the individualism of economic liberalism, brought with it a polarising and politicised debate that depreciated the economic and ecological functioning of an ancient form of cooperative land use that nonetheless has proved in many places to be viable into the present (Olwig, Citation2002; Ostrom, Citation1990; Rodgers et al., Citation2011). The two landscapes, however, can co-exist side by side, as they have done for centuries in Lakeland, if their differences are understood and respected.

Two landscapes

According to the European Landscape Convention ‘Landscape means an area, as perceived by people, whose character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors’ (Council of Europe, Citation2000). ‘Perceive’ means both to ‘become aware of (something) by the use of one of the senses,’ and to ‘interpret or look on (someone or something) in a particular way’ (NOAD, Citation2005: perceive). Our knowledge of landscape thus depends both on how we perceive some thing with one or more of our senses and how we interpret that thing, which, in turn, effects in a circular way how we perceive that thing (Olwig Citation2004). Perception thereby involves both the sensing of some thing and the constituting of the thing that one senses.

A dictionary definition of landscape typically contains such definitions as: ‘1a: a picture representing a view of natural inland scenery’ and ‘2b: a portion of territory that can be viewed at one time from one place’, which is to say a portion of territory visually perceived as scenery. It also includes, however: ‘2a: the landforms of a region in the aggregate a landscape of rolling hills’ (Merriam-Webster, Citation1994: landscape). Scholars such as Denis Cosgrove have won broad acceptance for the thesis that this modern definition of landscape as scenery is the outcome of the way visual perception was structured historically. Key to this development were initially the cartographic techniques created particularly in the service of the Renaissance enclosure of the common lands of the Venetian ‘Domini di Terraferma’ in connection with a shift in power from the Venetian archipelago to the mainland. The definition of landscape as an ‘aggregate’ of landforms fits the top-down cartographic perspective, where the land appears to be formed of a segmented aggregation of bounded shapes (hills, lakes, but also fields, estates and parks). The second factor was the reconfiguration of the top-down cartographic projection to create a more horizontal scenic perspectival illusion of three-dimensional space, as opposed to two-dimensional cartographic space. This made it possible to make pictures representing scenic views, which, in turn, stimulated the ability to perceive and shape landscape as scenery. Architects, notably Palladio, surrounded the new Venetian mainland estates with enclosed pastoral landscaped parks designed using this mode of scenic representation. In this way the pastoral commons as used and sustained by the commoners were enclosed and became landscaped images of ideal pastoral environments, managed and maintained by groundskeepers that became the sine qua non of the ‘Palladian landscape’ (Cosgrove Citation1991). The scenic landscape, like the map from which it derives, can be scaled up, using Euclidean space as a common denominator, from the level of the enclosed estate, its fields and its landscape park to that of the state and its regional governmental districts and parks (Olwig, Citation2002).

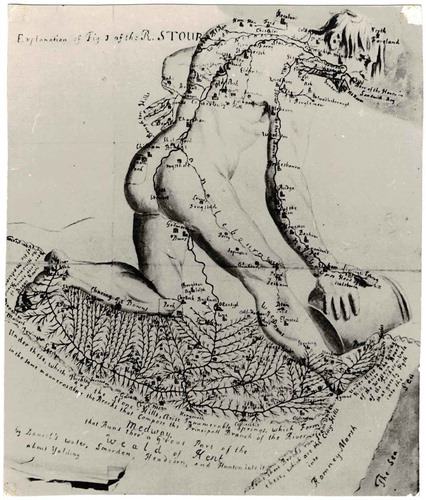

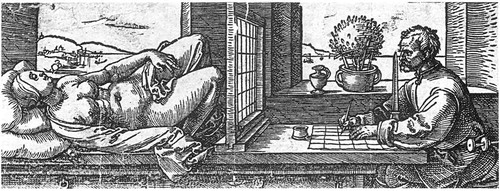

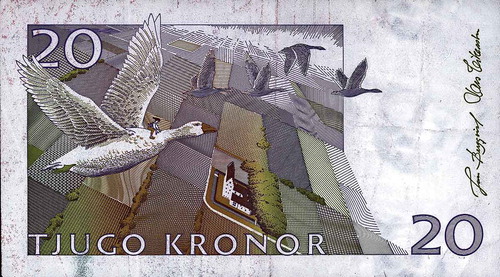

The workings of cartographic/perspectival perception are illustrated in –. , an instructional drawing by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1582), shows how perspectival illusion is created essentially using scaled down surveying techniques, while , a now decommissioned Swedish banknote, shows how the lines of an enclosed landscape as seen from top down also can act to form the lines forming a more horizontal perspectival scenic view (Olwig Citation2017). The illustrations have the structure of perspectival stage scenery, which Palladio pioneered, in which the stage floor is that of earthly nature and the sky is that of the atmosphere and cosmos, with the layers of the cultural landscape sandwiched in-between. This helps explain why landscape is defined as natural inland scenery.

Figure 1. Drawing by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1582) illustrating a technique for constructing perspective using Euclidean, geometrical forms, notably a grid resembling a map’s graticule, to construct the illusion of three dimensional organic bodily forms.

Figure 2. This Swedish banknote illustrates how the lines on the map, and the lines of perspective, structure the space of landscape scenery. These lines would normally be invisible, but here they have been materialised as enclosed property boundaries. (Colour figure available online).

A further element of this landscape perception, seen particularly in , is the perspectival depiction of a woman’s body framed by the artist’s map-like graticule, along with the landscape framed through the windows. Perspective also fostered the notion of landforms as having an organic, bodily character, and of the body as a kind of landscape that can be perceived as a segmented aggregation of bounded organs and arteries. Indeed Kate Cregan has argued that anatomy and enclosure, which involved the dissecting of the landscape, depended upon essentially cartographic and perspectival artistic methods for visualising and conceptualising both biological bodies and bodies of land. ‘Cartography and anatomy’, thus, ‘both rely upon an inter-play between artistic conventions and territorialization’ (Cregan, Citation2007) (see ). It was therefore not coincidental that key biological scientists introducing this idea, such as Linnaeus, were trained as physicians—the word physician deriving from the Latin physica, meaning ‘things relating to nature’ (NOAD, Citation2005: physician). Within this context landscape came to be seen not as being shaped by a ‘body politic’, that is a body of people, but rather as a spatially bounded, as if by skin, body with natural organs in the shape of, for example mountains or arterial waterways () which formed a natural, enclosed estate of nature (Olwig Citation2016). The health of this body thereby must be examined, surveyed, managed, cared for, nursed, healed and restored as an organic bodily whole, much as physicians, with different specialties, examine and treat a body and its organs. The perception of landscape as scenery allowed for an appreciation of the cultural landscape growing out of the soil of the physical landscape, which has traditionally been the landscape favoured in British national parks. But it can also lead to a desire to isolate and protect the ‘original’ foundational virginal wilderness landscape from culture within a bounded space, as has been the case with the internationally dominant, German influenced, traditional American wilderness approach to nature preservation that has inspired the current rewilding movement. This leads to a polarisation of nature and culture that is difficult to mediate (Cronon, Citation1996; Olwig, Citation2017).

The landscape as body politic

If the enclosure of the commons as private property, as constituted and perceived through the use of cartography and perspectival representation, provided a basis for the perception of landscape as a body of scenery, one can ask what sort of perception emerges from dwelling as a body of people in a habitat characterised by unenclosed commons? With the unenclosed commons, the commoner has customary use rights (usufruct) to a mix of the differing phenomena that constitute a commons. A commons is not defined by a particular boundary or scale, but by what constitutes it in the way of common resources (e.g. pasture and woodland). In fact, in England it is often not permissible to enclose commons within a wall or fence, so the boundaries are often indistinct (Rodgers et al., Citation2011). Perceptions of the commons as landscape will therefore differ according to its attributed use value based on a complex mix of resources present in varying, and changing, degrees in a given commons. The shepherd, for example, will perceive the landscape in terms of pastoral resources (e.g. edible forage, micro-climate and water); the woodsman will focus on the woods; the basket maker on the bush and the manor owner perhaps the game. The mix of sensory modalities used to perceive the commons will involve much more than the visual (e.g. the smell of the land, the feel of the air’s movement and moisture content on the skin, the taste of the water and soil). The qualities of such a commons are not fixed, unlike the cartographically bounded, uniform, Euclidean space of property. Thus if land is not kept in pasture it will deteriorate and it will be lost, both practically and legally, according to customary law. Moreover, in-so-far as each commons is diverse and to some extent unique, the diversity of customary law that applies will differ accordingly (Rodgers et al., Citation2011). Indeed, a commons cannot be scaled as landscape in the way that the space of property, territory and scenery can, because scale requires a common denominator, like the map’s Euclidean space.

Given that people with different sets of use rights can share a commons, there will also be differing perceptions of the things constituting the landscape of the commons, and this creates the potentiality for conflict. Historically, such conflicts were resolved by legal bodies, representative of the commoners’ interests, such as the ‘thing’ or ‘moot.’ The members of these bodies needed to know their things in relation to the differing sets of use rights to the commons. They were not, first and foremost, concerned with things as matter, but with things that mattered in the perception of a polity with rights of common. This is why the original meaning of thing is not the material thing in itself, but the thing as a legal body that determined the meaning and value of differing material things in relation to use rights (Merriam-Webster, Citation1994: thing, Olwig Citation2013). Likewise, the historically prior meaning of landscape, before it was enclosed as scenery, was, broadly speaking, a body politic and the land that it shaped according to its customary law as adjudicated by thing-like institutions (Olwig, Citation2002). Such legal bodies continue to function in specific relation to the use of commons (as at New Forest in England), but they also have attained a broader function to the degree that customary law has morphed into common law. In this way, as Bruno Latour has argued, it provides the principle behind the shaping of environmental perception and use by a variety of differing organisations which people govern through representative bodies (Olwig, Citation2013).

The landscape as body politic

As the philosopher Michel Foucault has argued, the shepherd with the flock has provided a primary metaphorical foundation for notions of human communality and governance far back into the heritage of Greco-Roman society as preserved by the Christian church. The rise of the territorially enclosed nation state eclipsed the governance role of the church, but the church persisted as a subaltern institution that in some incarnations transcended the state’s territorial boundaries and control. This legal and governmental heritage was rooted not in fixed territoriality, but in the movement of a flock through common grazing lands. Foucault puts it this way: ‘The shepherd’s power is not exercised over a territory but, by definition over a flock, and more exactly, over the flock in its movement from one place to another.’ This means that ‘in contrast with the power exercised on the fixed unity of a territory, pastoral power is exercised on a multiplicity on the move’ (Foucault, Citation2007: 171). These ideas translated into the Germanic languages, such as English, via terminology used in the pastoral societies of northern Europe. The English word ‘flock’ thus can be applied both to animals as ‘a group of animals (as birds or sheep) assembled or herded together’ and to people as ‘a group under the guidance of a leader, especially: a church congregation.’ Historically the term was akin to the Old Norse Flokkr (Merriam-Webster, Citation1994: flock). According to the Danish standard dictionary the word ‘flok,’ as descended from the Old Norse, referred to living beings who were ‘considered to have a certain individual independence, often with the connotation of conscious organization, community, agreement and the like’ (trans. KRO, O.D.S., Citation1931: flok), thereby further metaphorically linking the nature of both the human and the animal flock. In Faeroese, which has changed relatively little from the Old Norse, the word can refer to a flock of sheep as well as to a political party, as in the name of the independence party called Fólkaflokkurin (literally the ‘Folk Flock’). In this way the notion of the flock plays a role shaping the idea of landscape as the expression of a body politic made up of individuals working together as a body in ‘fellowship’ (a term originally designating a body of shepherds raising grazing animals together) that in turn shapes the substantive landscape (Olwig, Citation2002, (Citation2013)).

Historically, the term ‘body,’ as in the phrase ‘body politic,’ was used figuratively to mean: ‘a group of people with a common purpose or function acting as an organized unit’ (NOAD, Citation2005). This notion of the body was key to the Christian idea that through the Eucharist’s consumption during Holy Communion, symbolising the body and blood of Christ, the sacrificial lamb, the worshipers became members of the Christian church as a body making up a community with Christ as its head. Historically, pastoralism has provided a key metaphor for conceptualising this kind of body. Such a body, as in the case of the members (as in the members/limbs of a body) of a parish church under a pastor, is analogous to a flock or body of sheep (the word pastor derives from the Latin for shepherd) where the individual sacrifices its individual identity to that of the flock, much as Christ sacrificed himself (Kantorowicz, Citation1957: 7–23, 193–232, Barkan, Citation1975: 61–115). This notion of the landscape body politic changed with the rise of the idea of landscape as a body of land.

In the following, I will examine how the perception of landscape as an organic body fostered by enclosure clashes with the perception of landscape fostered by commoning in the case of the English Lakeland perceived as part of an Atlantic ‘archipelago.’

The English Lakeland and the Atlantic ‘archipelago’

The English Lakeland is an imprecisely defined area of lakes and mountains in North West England that came to be loosely known as ‘The Lake District’ due to the influence of the Romantic Poet William Wordsworth’s 1810 A Guide to the District of the Lakes in the North of England that focused on the scenery of the area (Wordsworth, Citation2004; Thompson, Citation2012: Introduction). Wordsworth’s Lake District did not have precise boundaries, but when the area was designated as The Lake District National Park in 1951 it became a district in the formal sense of a ‘region defined for an administrative purpose’ (NOAD, Citation2005: district, Olwig, Citation2016). However, instead of viewing Lakeland in terms of its national natural scenery administered as a bounded English region, the area can arguably be perceived as part of a North Atlantic coastal ‘archipelago’ historically settled via a northern seaway stretching from the western coast of Scotland to the Faeroe Islands, Iceland and beyond to Norway. It could then be argued that Lakeland consists of at least two key landscapes, as perceived by people, with attendant human/nature relations and differing and often conflicting economies. The first is the landscape of the historically indigenous population of agriculturalists, with cultural ties to an Atlantic archipelago, who have shaped its pastoral environment as a cultural landscape defined in terms of use rights to often spatially discontinuous areas, or ‘islands’, of common resources. The second is that of a spatially bounded and unified district, perceived as natural scenery and as a unified economic and social space for recreation and environmental management, used by populations coming largely from core English urban areas.

Within the archipelagic framework one might reverse one’s image of the ‘Lake District,’ as in a photographic negative, so that instead of regarding the area as a land area interspersed with lakes, one could think of it as an elevated Atlantic archipelago merging with the irregular coastlines of the Irish Sea and beyond to the Norwegian coastal archipelago. The geographer E. Estyn Evans wrote of ‘Atlantic Europe’:

Climatically, the mild winters, heavy all-season precipitation and high values of wind and cloud have favored pastoralism rather than arable farming. Consciousness of an Atlantic culture-area extending from Galicia to Norway was strongest in the early days of Christianity, by which time fishing and seafaring, extensive stock-rearing and restricted arable farming were well adapted to the three major elements of the environment. Independence, pride of blood and strong personal loyalties were characteristic features of society. The prevailing form of settlement was the joint farm or extended-family holding, a cluster of peasant home-steads possessing common rights in infield, outfield and mountain grazing…. It is argued that the system of co-operating kin-groups was maintained along the Atlantic in environments which called for common effort .… Along the Atlantic shores, peasant attitudes … have not entirely succumbed to the impact of a money economy. Idealization of the past … coupled with suspicion of impersonal external authority, have sprung from the experience of living in the Atlantic Ends (quoted from Evans Citation1958a: 581–582, see also Evans Citation1958b).

Evans was inspired by Cyril Fox’s classic archaeological study, The Personality of Britain (Fox, Citation1952). Using archaeological data Fox argued that: ‘The portion of Britain adjacent to the continent being Lowland, is easily overrun by invaders, and on it new cultures of continental origin brought across the narrow seas tend to be imposed. In the Highland, on the other hand, these [cultures] tend to be absorbed.’ And from this he suggested that: ‘There is a greater unity of culture in the Lowland, but greater continuity of culture in the Highland Zone’ (Fox, Citation1952: 88). He illustrated his thesis with maps showing how the settlement of the western Britain, including Lakeland, came not from the East, but from the Atlantic fringe, down along the archipelagic western coast of Britain from Scotland (see also, Rawnsley, Citation1911b, Walton, Citation2011: 22). This idea persists today in the influential scholarship of John Kerrigan who has argued for an ‘archipelagic’ approach to English literature in which an area of the North-West Atlantic, roughly corresponding to that outlined by Fox, constitutes ‘culturally as well as politically, a linked and divided archipelago’ thereby designating ‘a geopolitical unit or zone.’ The concept of the archipelagic is useful because it allows for a more fluid notion of spatial interconnectivity, that is both ‘linked and divided,’ than is allowed for in the context of the enclosed uniform Euclidean space of a geographic ‘body’ like Britain (Kerrigan, Citation2008: vii, Olwig, Citation2002; Citation2007).

The Atlantic archipelago and Lakeland have common cultural continuities. Both, for example, have resisted enclosure, and thus have large areas of commons—Lakeland has the largest concentration of commons in England (England, Citation2008: 33–37). This suggests that there might exist a shared common landscape perception, which means that those who share this archipelagic mindset might perceive, and constitute, a different landscape than those from core areas for whom the landscape is perceived largely in terms of spatially defined property and natural scenery. A key to the archipelagic landscape perception is found in what may be called a ‘landscape language’ that is distinctive to the Atlantic archipelago.

Lakeland shares with the Atlantic archipelago a body of terms of Nordic origin that interlinks toponyms and customary shepherding practices (see also, Rawnsley Citation1911b). Key to this interlinking in the landscape language is the ‘hefted’ seasonal movement of flocks from the dal or dale, deriving from the Old Norse dalr meaning valley (found in Lakeland place names like Langdal—where lang is the Nordic for long); up through passageways called gang, from Old Norse gangr, ganga (NOAD, Citation2005: gang), to the fell, meaning mountain, from the Old Norse fjallr, as related to modern Norwegian fjell, and Faeroese fjall meaning mountain. Another important topographical feature is the howe from the Old Norse haugr meaning hill, knoll, or mound, haug, in modern Norwegian, heyggjur in Faroese, which is related to Haggi a grazing area linked to Hagfest, which is the attachment of a flock to a particular pasture. Hagfest is related to heft (also written heaf). Heft derives from the Old Norse hæf∂a which is a term used both in Lakeland (also Scotland) and the Faeroes to describe the ability of a flock of sheep to bond to particular pastures within a shared commons, thereby obviating the need for fencing, or boundaries, while allowing for a flexible pattern of grazing on lands to which the sheep have become biologically adapted. In the Faeroes it is thus said that common pastures ‘belong to the sheep’ because it is through the process by which differing flocks of sheep heft to the land that their differing shepherds gain a customary use right to those pastures. In the Scandinavian languages, including Faeroese, the word heft also applies, as a legal term, to hefted customary rights more generally—a customary right is thus a ‘heft won’ right. To keep the land under heft means both to maintain the land through use, as with grazing, pruning and mowing, and to maintain a customary use right to the land through the use, and not the abuse, of that right (Rawnsley, Citation1911b: 50, O.D.S., Citation1931: hæft, Vinterberg & Bodelsen, Citation1966: hævd, Falk & Torp, Citation1996 (1903–1906): Hævd, Hæve, Hefte, Olwig Citation2006: 27–29). It is for this reason by extension that heft is also used, both in Lakeland (also Scotland) and the Faeroes, for the attachment that both sheep and people develop to place (Scottish National Dictionary, Citation1960: heft, Gray, Citation1999: 451).

The landscape of Lakeland, as elsewhere in the Atlantic archipelago, is rooted not in the exercise of power over a territorial body understood as property but rather in the cooperative interaction between the individual bodies of people and animals in a pastoral fellowship with access to diverse assemblages of resources that are not necessarily spatially contiguous. Such modes of thought are key, it will be argued, to understanding Lakeland’s pastoral landscape, the area’s role as a cultural hearth in the arts and literature, and the area’s importance to the access for recreation/rambling and environmental movements, the genesis of the National Trust and Lakeland’s recent achievement of UNESCO World Heritage status (UNESCO, Citation2017).

Shepherding, law and religion

Evans noted that ‘consciousness of an Atlantic culture-area’ was strongest in the early days of Christianity (quoted from Evans Citation1958: 581–582). At roughly the same time as the Norsemen were moving from Scandinavia towards the British Isles, Christian monks were moving in the opposite direction, converting the peoples they met and creating their own landscape of churches and pastorates (Hastrup, Citation1985). Wordsworth emphasised the historical synergy of pastoralism and the church in the Lakes, writing: ‘The chapel was the only edifice that presided over these dwellings’ (Wordsworth, Citation2004 (orig. 1810): 74–75). Christianity grew out of a Near Eastern context in which pastoralism was vital. This can be seen in the metaphor of the Lord as a good shepherd, found in, for example, the 23rd Psalm or in the passage from Isaiah seen to foreshadow the idea of Christ as a good shepherd: ‘He shall feed his flock like a shepherd: he shall gather the lambs with his arm, and carry them in his bosom, and shall gently lead those that are with young’ (quoted in Rawnsley, Citation1911b: 69). But the pastoral idea also grew out of the culture of classical Greece and Rome, which played a role in the Christianized ideas that spread to Western Europe. Foucault notes, for example, that the Pythagoreans, who had a foundational position in Greek philosophy, derived the idea of law gnomes (nomos) etymologically ‘from nomeus, that is to say, the shepherd’ (Foucault, Citation2007: 188). In contrast to the pastoral understanding of nomos, law founded on property excludes and negates the more relational role of common custom and use rights in defining land rights (Olwig Citation2005). The foundational legal importance of pastoralism to classical Greco-Roman, and Christian, culture helps explain the importance of pastoralism in the work of such central classical authors as Homer and Virgil, and in the subsequent pastoral genre in Western literature and art, not the least the literature and art of Lakeland (Barrell & Bull, Citation1974; Curtius, Citation1953). This importance, furthermore, was not lost on Canon Hardwicke Drummond Rawnsley (1851–1920), who settled in Lakeland and became a key figure in the development of the English conservation and access movements (Lear, Citation2007; Olwig, Citation2016: 258–259). Central to understanding his work, it can be argued, is the metaphor of shepherding, which he experienced through his parishioners’ pastoral practices and landscape with its Norse nomenclature (Lear, Citation2007, Rawnsley, Citation1911b).

Rawnsley did much to foster the church’s role as community builder through its support, for example, of the customary celebrations that brought people together as community. He also took a more direct interest in their occupation as shepherds, and their Herdwick sheep (Lear, Citation2007, Rawnsley, Citation1911b), helping to form The Herdwick Sheep Association in 1899. The Herdwick sheep had grazed the most marginal uplands of Lakeland for centuries, the name Herdwick being synonymous with pasture (meaning herd dwelling place/pasture). The Herdwick sheep, as Rawnsley emphasised, is particularly noted for its ability to heft on, and survive on, the fell pastures. The hefting ability is related to this temporal continuity because a portion of the herd, in accordance with time out of mind custom, continues to belong to the pasture, that is, it is inalienable to the pasture. To this day shepherds, who sell their farm or leave a tenancy, can keep only a percentage of the sheep, while the remainder (about 25%), the ‘landlord’s flock,’ must remain on the herd’s ancestral heft. This means that a given flock, in theory, may have hefted pastures going back centuries. The Herdwick was thus the embodiment of hefting as an expression of place identity and the Christian pastoral community ideal (Rawnsley, Citation1911b: 69, Gray, Citation1999; Olwig, Citation2006). Rawnsley worked with the author and botanist Beatrix Potter, encouraging her to become engaged with Herdwick shepherding, and convincing her to invest her income in Herdwick farms. She eventually donated her farms to the National Trust that Rawnsley helped organise in part for this purpose, and which made it a major Lakeland landowner (Lear, Citation2007) owning about 25 per cent of the Lake District (Brown, Citation2009: 97).

The 18th and 19th century enclosure of open land for farming and recreational game reserves by estate owners in much of England alienated ordinary people from recreational access to former commons. Lakeland, however, historically belongs to an ‘archipelagic’ area of extensive pastoral agriculture with a commoning tradition on the margins of core mainland intensive, enclosed agriculture. Even though much of Lakeland came under large manors, with enclosed farmlands and landscape parks under estate management in accordance with the historical development of the rest of England, an unusually large portion of the land remained as commons to which the commoners had use rights that eclipsed the property rights of the estate. In this way, the perception and constituting of landscape of enclosure persisted alongside that engendered through commoning. A tradition with smaller independent farms also persisted (Olwig, Citation2013). Lakeland, due to the many commons, allowed for freer accessibility in practice following local custom, thus creating a natural tie between Rawnsley’s fascination with the hefted Herdwicks of Lakeland commoners and his concerns related to the place identity of the larger English populace. The link between the movement for recreational access and the establishment of the National Trust is brought out in Lord Eversley’s monumental Commons, Forests and Footpaths: The Story of the Battle during the last Forty-five Years for Public Rights over the Commons, Forests and Footpaths of England and Wales:

The National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, incorporated under the Companies Acts in January, 1895, owes its existence to the exertions of Canon Rawnsley, the late Duke of Westminster, Miss Octavia Hill, Sir Robert Hunter, and other prominent members of the Commons Society. Owing to the nature of its work the Commons Society could neither be incorporated nor hold land, and it was felt that there was room for an organisation which, removed from the harassing cares of fighting the people’s battles, could steadily set itself to acquire by gift or purchase places of special historic interest or natural beauty in order to hold them for the use and enjoyment of the public. …. (Eversley, Citation1910: 327-28).

In this light it is ironic that the Trust is now often identified with the iconic lowland private estates with Palladian landscapes, like Stowe, that have subsequently been bequeathed to the Trust (Olwig, Citation2002: 99–124, Citation2016). Landscape management makes historical sense for such estates, but it becomes problematic when transferred to the Lakes. This is particularly apparent in the Trust’s present focus on rewilding projects aiming to restore the natural environment of the area prior to the introduction of pasturing. It therefore involves fencing that restricts the sheep’s access, but also that of ramblers (Webster & Burgess, Citation2015). The shepherds express disappointment in the district’s environmental managers’ apparent negative attitude to pastoralism and hefting, their use of fencing and their neglect of the Herdwick herding heritage of Potter and Rawnsley (see, Lear, Citation2007; Brown, Citation2009: 97, Rebanks, Citation2016). Behind this conflict in the interpretation of Lakeland, however, there is a basic difference in the perception of landscape as shaped by a body politic, and the idea of landscape as a bounded organ-like body of land to be shaped through management. This can be illustrated by the conception of the fells as ‘wagon wheels.’Footnote1

Lakeland ‘wagon wheels’

Many of the fells essentially have the shape of a wagon wheel, with the fell top as the hub and the rim as their circumference. The spokes are thus the ridges and the space between forms the steep-sided delta ∆ shaped dales, whose apexes meet at the ‘hub’ at the top. These dales have been cut by the streams that run through their middle. The visitor, or environmental manager, travelling through the area in a vehicle typically drives around the perimeter of the fells, stopping perhaps to take a walk past the sheep farms up the dale and back down to the car. What the visitor sees is a segmented pizza pie space with the slices neatly bordered by ridges. The environmental managers for the National Trust at Ennerdale (and possibly Borrowdale) (McKenna, Citation2016), along with the managers of similar valleys owned by another major land owner, United Utilities, at Haweswater and Thirlmere, appear to have taken for granted the perception of the dales as naturally divided segmented spaces when implementing rewilding schemes by which bounds are set separating one dale from the next (Webster & Burgess, Citation2015; Olwig, (Citation2016): 260–262). In the perception of the shepherd, however, this spatially segmented form of environmental management creates serious problems, and is antithetical to the shepherd’s perception of landscape.

According to the practice of the flocks, and the shepherds, the sheep do not move through a space walled and bounded by the ridges, but irregularly up towards the ‘hub’ through hefted, broadly grazed pastures concentrated on the valley floor. When the sheep reach the top of the fell at the ‘hub’ what stops them from going over the top and into the pastures belonging to the sheep of the farms in the valley below is not a physical boundary, but the presence of equivalent numbers of hefted flocks from the commons of the adjacent valley. This is because the sheep flocks are disinclined to mix with other hefted flocks, and hence move onto their heft—hefting is thus more a sheep-social than a sheep-territorial phenomenon (Rawnsley, Citation1911b). If there are no sheep in the valley on the other side of the hub, however, the sheep coming up will cross the top and go down into the valley. There is also a problem if there is an imbalance in the number of sheep on either side of the valley. This can occur, for example, when headage payments encourage individual shepherds to increase their herd beyond the sustainable carrying capacity of their heft, leading the flock to invade neighbouring hefts (Olwig, Citation2016). The breakdown of hefting creates a serious problem for the shepherd because the journey over tortuous paths necessary to follow the sheep over the hub is difficult and time consuming, and because the distance by road around the circumference of the wagon wheel can be considerable. Fencing is not an optimal solution because the sheep are not used to fencing and can become trapped by it in bad weather. Furthermore, it is difficult to make fencing that wily sheep cannot circumvent. The maintenance of the hefting system, and the commons generally, thus requires not fences, but the ‘neighbourliness’ necessary to maintain the equitable sustainable grazing that produces the healthiest and most valuable animals (Rodgers et al., Citation2011).

The differing landscape perceptions can lead to conflicts, such as when, for example, the United Utilities elected to turn over the management of the Haweswater dale to the The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), which subsequently adopted a rewilding strategy and acted to limit pastoralism (Olwig, Citation2016). The state environmental body, English Nature, working with the National Park, has also sought to remove pastoralism, especially at the higher altitudes where they have projects to recreate hypothesised ancient forests. Such initiatives, from the perspective of environmental managers, are defensible because they are apparently simply repurposing clearly defined spatial segments of the Lake District in order to give those concerned with rewilding, or wilderness recreation, their own spatial slice. It is questionable, however, whether nature survives best within such fenced slices of marginal lands, and this has led to criticism by scientists of such ‘fortress conservation’ (Karieva & Marvier, Citation2011; Olwig, Citation2016).

In the perception of the shepherds, the cutting out of segments from the wagon wheel is problematic because it threatens hefting, and hence shepherding, on the commons of entire areas of fell, and not just a given segment. Customs must be practiced to continue to maintain their force, which is why, for example, English rambler organisations regularly walk common footpaths. If fencing and environmental schemes reducing hefted flocks gain headway it is feared that the commons, and a whole way of life, will be lost (Rebanks, Citation2016).

Conclusion

Once it is understood that not all areas of land have the same history, and embody the same perception of landscape, then it is possible to comprehend the reason influential poets and thinkers ranging from Wordsworth to Rawnsley were drawn to the pastoral Lakes, and why the cultural landscape of the area was recently named a UNESCO World Heritage site. It is clearly a place which expresses values that set it apart as a repository of a cultural heritage with a landscape that has been lost elsewhere, and which thereby can help inspire alternative ways of thinking, for example, about nature, the environment, access and belonging. If conceptualised as an historical extension of an Atlantic archipelagic culture, with an agriculture and economy differing from that of the intensively cultivated and capitalised landscape of the core areas of the lowlands, then it might become easier to understand how the care for Lakeland, and its population might be reimagined and treated, and an inspiring corner of England given renewed life. If seen in the light of other living areas of the Atlantic archipelago, such as the Faeroe Islands, the Lakeland shepherds’ economy and culture might seem much less like an old fashioned anomaly, and their landscape as something to be managed as natural scenery. It might rather be seen as an alternative living landscape with its own existential premises that increases the landscape diversity of the world’s heritage.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. This was explicated to me by a number of shepherds, but the wagon wheel figure apparently goes back as far as Wordsworth, see (Thompson, Citation2012).

References

- Barkan, L. (1975). Nature’s work of art: the human body as image of the world, New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Barrell, J., & Bull, J. (1974). The penguin book of English pastoral verse, London: Allen Lane.

- Brown, G. (2009). Herdwicks: Herdwick sheep and the English district, South Stainmore, Kirkby Stephen, Cumbria: Hayloft.

- Cosgrove, D. (1993). The Palladian landscape, University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Council of Europe. (2000). European Landscape Convention, Florence. CETS No. 176. Strasbourg: Author.

- Cregan, K. (2007). Early modern anatomy and the queen’s body natural: The sovereign subject. Body & Society, 13(2), 47–66.

- Cronon, W. (1996). Uncommon ground: Rethinking the human place in nature. (W. Cronon, ed), New York: W.W. Norton.

- Curtius, E. R. (1953). European literature and the Latin middle ages, London: Kegan Paul.

- England, N. (2008). State of the natural environment 2008 (NE85), Sheffield: Natural England.

- Evans, E. E. (1958a). Anonymous summary of: “The Atlantic ends of Europe”. Nature (Supplement), 182(4635), 581–582.

- Evans, E. E. (1958b). The Atlantic Ends of Europe. The Advancement of Science XV: 54–64.

- Eversley, L. (1910). Commons, forests and footpaths, London: Cassell.

- Falk, H., & Torp, A. (1996 (1903–1906)). Etymologisk ordbog over det norske og det danske sprog, Oslo: Bjørn Ringstrøms Antikvariat.

- Foucault, M. (2007). Security, territory, population, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fox, S. C. (1952). The Personality of Britain. Cardif, National Museum of Wales.

- Gray, J. (1999). Open space and dwelling places: being at home on hill farms in the Scottish borders. American Ethnologist, 26(2), 440–460.

- Hastrup, K. (1985). Culture and history in medieval Iceland: An anthropological analysis of structure and change, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Kantorowicz, E. H. (1957). The king’s two bodies: A study in mediaeval political theology, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Karieva, P., & Marvier, M. (2011). Conservation science: Balancing the needs of people and nature. Greenwood Village: Roberts & Company.

- Kerrigan, J. (2008). Archipelagic English: Literature, history, and politics 1603–1707, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lear, L. (2007). Beatrix Potter: The extraordinary life of a Victorian genius, London: Penguin.

- McKenna, K. (2016). “The National Trust, the sheep farm and the fight for a Lakes way of life.” The Guardian, Sunday 4 September. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/sep/03/national-trust-lake-district-borrowdale-sheep-farm-sale-fight

- Merriam-Webster. (1994). Collegiate dictionary and thesaurus, Springfield, MA.: Author.

- NOAD. (2005). New Oxford American Dictionary, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- O.D.S. (1931). Ordbog over det danske sprog, Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

- Olwig, K. R. (2002). Landscape, nature and the body politic, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Olwig, K. R. (2004). “This is not a landscape”: Circulating reference and land shaping. In European rural landscapes: Persistence and change in a globalising environment ( H. Palang et. al, eds. pp. 41–66). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

- Olwig, K. R. (2005). The landscape of ‘customary’ law versus that of ‘natural’ law. Landscape Research, 30(3), 299–320.

- Olwig, K. R. (2006). Place contra space in a morally just landscape. Norwegian Journal of Geography, 60(1), 24–31.

- Olwig, K. R. (2007). Are islanders insular? a personal view. Geographical Review, 97(2), 175–190.

- Olwig, K. R. (2013). Heidegger, Latour and the reification of things: The inversion and spatial enclosure of the substantive landscape of things – The Lake District case. Geografiska Annaler, Series B: Human Geography, 95(3), 251–273.

- Olwig, K. R. (2016). Virtual enclosure, ecosystem services, landscape’s character and the ‘rewilding’ of the commons: the ‘Lake District” case. Landscape Research, 41(2), 253–264.

- Olwig, K. R. (2017). Geese, elves and the duplicitous, ‘diabolical’ landscaped space of reactionary-modernism. GeoHumanities, 3(1), 41–64.

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rawnsley, H. D. (1911a). By fell and dale at the English lakes, Glasgow: James MacLehose.

- Rawnsley, H. D. (1911b). A crack about herdwick sheep. By fell and dale at the English Lakes (pp. 47–72), Glasgow: MacLehose.

- Rebanks, J. (2016). The shepherd’s life: A tale of the lake district, London: Penguin Books.

- Rodgers, C. P., Straughton, E., Winchester, A. J., Pieraccini, M. (2011). Contested common land: environmental governance past and present, London: Earthscan.

- Scottish National Dictionary (1960). Edinburgh, The Scottish National Dictionary Association.

- Thompson, I. (2012). The English lakes: A history, Bloomsbury: London.

- UNESCO. (2017). “English Lake District welcomed into UK UNESCO family as 31st UK World Heritage Site.” from https://www.unesco.org.uk/news/english-lake-district-welcomed-into-uk-unesco-family-as-31st-uk-world-heritage-site/.

- Vinterberg, H., & Bodelsen, C. A. (1966). Dansk-engelsk ordbog. Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

- Walton, J. K. (2011). “Cumbrian Identities: Some Historical Contexts.” Trans. of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society 3rd Series XI: 15–27.

- Webster, B., & Burgess, K. (2015). “Walkers fear six-mile fence will spoil the Lake District”. The Times. London, Times Newspapers, February 23, p. 3.

- Wordsworth, W. (2004) (orig. 1810)). Guide to the lakes. London: Francis Lincoln.