ABSTRACT

The modern notion of the landscape of the nation-state, we argue, emerged in part through an ‘emblematic’ fusion of the nation, imagined as a bio-organic body-politic, and the state conceptualised in geo-metric terms as the Euclidean, cartographic framework within which that body operates. The eliding of the geo-metric with the bio-organic has influenced national discourse, law and practice by defining the legal and social right to belong within this landscape in bio-spatial terms. This is exemplified by the international political cause célèbre of the ‘Schleswig-Holstein Border Question’ and its continuing ramifications for the quality of life in Denmark—particularly for those living in the landscapes of state-designated immigrant ‘ghettoes’ scheduled for physical and social eradication because their settlements are perceived as endangering the bio-spatial cohesion of the ‘nation-state’.

Introduction

The modern notion of the landscape of the ‘nation-state’, we argue, emerged in part through a confusing ‘emblematic’ fusion of the nation and the territorial state. In this fusion the nation was understood as a ‘bio-organic’ body politic imagined as forming an implicitly biological organic whole (hence the ‘bio-organic’), whereas the state was conceptualised in terms of the Euclidean geometry of the map, which determines the measurable metrics of the territorial framework within which that body operates (hence the ‘geo-metric’). This eliding of the bio-organic with the geo-metric has had important implications for discourse, law and practice, exemplified here by the case of Denmark. We begin with the international political cause célèbre of the ‘Schleswig-Holstein Border Question’ and the way it gave rise to an emblematic Danish landscape that has shaped national identity. We proceed to examine the continuing ramifications of this landscape for the quality of life in contemporary Danish society and end by showing how certain immigrant and refugee settlements have become a ‘negative emblem’ (Grieco, Citation1994) as state-designated ‘ghettoes’ scheduled for physical and social eradication because they are perceived as endangering the bio-spatial cohesion of the nation-state. In order to highlight the significance, as illustrated here, of the notoriously difficult and conflicted historical and conceptual relationship between the nation and the state we hereafter use a slash, writing ‘nation/state’, to indicate their conceptual separation.Footnote1

The emblem and the emblematic

The nation and state were fused, we argue, via the figurative emblem that involves a combination of the pictorial and the textual. Through the medium of figurative pictures an affective, emotional link is made between the bio-organic idea of the nation and the geo-metric conception of the state which, in turn, is linked to texts that interact with and reinforce the affective message of the emblem as a pictorial and textual unit. The emblematic pictorial image stimulates the imagination by unifying within the geometric space of the emblem an assemblage of objects and figures, such as maps, flags, monuments and iconic representation of human bodies symbolising the nation, that together communicate a given affective, emotive, emblematic message. In this case the emblem conveys the message that the nation is an organic body of people of implicitly shared biological descent, and that the state provides the legal framework for the nation based upon lawful principles inspired by those of geometry. The emblem developed out of the ‘emblem books’ of the Renaissance and Baroque eras. That were enormously popular and influential for several centuries (Merriam-Webster.com, Citation2020; Moffitt, Citation2004). They arguably generated an independent pictorial language, involving a series of interrelated emblems, which has its own rationality, or ‘grammar’, that is expressed through images rather than words. This ‘grammar’, like that of spoken language, has become internalised over the centuries, shaping the perception, design and planning of the political and material landscape, thereby affecting the quality of life in that landscape. Historically, the emblematic pictorial image was often represented as a landscape scene or a globe, and differing emblems were mapped into a larger ‘landscape’ of emblems that share many of the same component parts. They thereby formed a kind of pictorial ‘text’ expressive of emotions and ideas linked to the scenic landscape of places. In this context it is thus not just the flag, for example, that is the emblem of a nation. Rather, the flag in conjunction with a landscape, made up of various combinations of objects or figures, creates an emblematic landscape. The flag at an ancient Danish monument or fortification and the flag at a suburban Danish single family home, the parcelhus, thus link two emblematic representations of Danish national identity, which nevertheless have differing connotations.

Much landscape debate has concerned the role of the Renaissance artistic development of the cartographic and perspectival representation of real or imagined places in forming the modern scenic conception of landscape. This conception, in turn, affected the perception, design and planning of the material environment conceptualised as landscape (cf. Cosgrove & Daniels, Citation1988). The importance of the emblematic lies in its representation of concepts and ideas rather than places. But its significance also inheres in its ability to link place affectively to ideas as well as moral and philosophical lessons. The emblem books appeared at about the same time as Renaissance perspectival landscape art (which often was illustrative of a Biblical or classical text) and they are used by art historians to interpret the meaning of the era’s paintings. The emblematic, furthermore, inspired landscape garden design (Hunt, Citation1971). It therefore seems safe to conclude that the emblematic is relevant, along with landscape art, to the development of the modern scenic conception of landscape and thereby to the perception and shaping of our material landscape—here the landscape of the nation-state, with its emblematic landscape ideals.

In the following we analyse how the emblematically embodied nation-state can affect the sense of justice and the quality of life using Danish examples. The first example focuses on the nineteenth-century ‘Schleswig-Holstein question’ and its aftermath in order to show how the ideological power of the emblematic can work in practice. This ‘question’ concerned whether the duchies of Schleswig-Holstein, to use the internationally common German spelling, should be incorporated into the emerging unified German nation/state or into the emerging Danish nation/state as Slesvig-Holsten (the Danish spelling which is used here in specifically Danish contexts). It became an international cause célèbre as a paradigmatic example of the conflicts generated by the rise of the nation/state as a bio-spatial entity (Sandiford, Citation1975). These conflicts and resultant wars, in turn, influenced the development of Danish national landscape identity (Oakley, Citation1972, pp. 189–211). The present day influence of this identity is subsequently explored in the context of controversies concerning the place of immigrants in the national landscape.

The Slesvig-Holsten/Schleswig-Holstein border question and the rise of the Danish nation/state

Defining the nation/state by its cartographic borders

Denmark’s political and economic core has for centuries been its Copenhagen capital and historically the country was not defined by sharp external boundaries. Rather, its territorial borders were demarcated by its ‘marches’—zones where the territory of one state faded into that of another. Slesvig, at the base of the Jutland peninsula south of the Danish kingdom, was typical of such a march zone with a mixed Danish, German and Frisian speaking population, and a complicated, overlapping crazy-quilt of territories under different forms of rule ranging from that of the Danish king in the role of duke, to German authorities of feudal origin, church authorities, Hanseatic city states and even relatively independent ancient polities called ‘landscapes’, or landskaber in Danish, based on proto-democratic representational assemblies called thing meetings (tingmøder in Danish) (Olwig, Citation2002, pp. 3–42). Holstein to the south was historically more German, but it had become politically conjoined to Schleswig/Slesvig because the Danish monarch was duke of both areas (). Despite the complexity of its rule, Schleswig/Slesvig-Holstein/Holsten was nevertheless of enormous importance to the Danish monarch because the royal family had its roots there, and because the area represented about one third of the territory under the monarch.

Figure 1. Map of Schleswig/Slesvig-Holstein/Holsten. The line labelled ‘Kongeåen’ (literally the King’s River) marks much of the Danish-German border 1864–1920. In this period, the areas south of this line, including Als and the islands in the Wadden Sea were under German rule. The bold line between Denmark and Germany marks the post-1920 border. The Eider River marks Schleswig/Slesvig’s southern border with the Danish fortification, Dannevirke, just to the north. Jelling is located north-west of Vejle. (Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation Licence, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jutland_Peninsula_map.PNG. Accessed 17 December 2020)

From the mid-eighteenth century, with the rise in Europe of a mixture of political, national, cultural and economic liberalism, there was growing pressure from both the German and the Danish side to divide Schleswig-Holstein/Slesvig-Holsten between the two countries (Oakley, Citation1972, pp. 189–211; Sandiford, Citation1975). Politically the European liberals generally wished to displace rule by a monarchical state with a representative government elected by the people as a nation. They nevertheless desired to maintain the authority of the state, and this in practice meant that constitutional monarchies with parliamentary representation emerged in Europe—including Denmark—in the mid-nineteenth century. The fact that the Danish monarch as the head of state was the duke of Schleswig-Holstein/Slesvig-Holsten, but not its monarch, meant that if Denmark was to become a single nation/state a national borderline needed to be drawn that incorporated part or all of Schleswig/Slesvig into the nation/state of the Danish kingdom. The heart of the Schleswig-Holstein question was thus the question of where and how this might be done so as to win national and international legal acceptance.

In Denmark the freeing of the people from feudal tenure involved dividing much of the land under the feudal estates into cartographically surveyed and enclosed, private properties. In agrarian Denmark this meant privately owned, single family farms or rural cottages for farm labourers and craftsmen. On a larger scale it also meant the enclosure of the Danish state as a kind of national ‘family’ within clear cartographic boundaries. The problem, however, which became particularly manifest in Schleswig/Slesvig, was that there were no clear-cut criteria by which to measure national identity. Language, as mentioned, was the preferred marker of national identity, but the duchy was characterised by a crisscrossing admixture of languages divided by dialects. There was, furthermore, no necessary correlation between language and national identity. In fact, many (perhaps most) people did not identify with a narrowly German, Frisian or Danish ‘nationality,’ but rather with Schleswig/Slesvig. They had to be taught that they had a national identity and, as we will show, the emblematic combination of the geo-metric and the bio-organic became an important tool whereby such an identity was created and asserted.

Particularly for what became modern Germany, national unification entailed the unification of a multiplicity of German speaking states within a single nation/state as defined by the homogenising uniform, isotropic, space of the map. The emblematic role that cartography played in the process of German unification can be gathered from this 1931 statement by the German writer Eugen Diesel:

Former ages, to whom exact cartography was yet unknown, conceived of the frontier in quite a different way from us […] But nowadays we Germans naturally think of Germany as an exactly drawn, precisely demarcated map. We have grown up with this, as earlier races grew up with fasces or swastika. It pursues us wherever we go, on posters, on the cover of the railway-guide, in our Baedekers and newspapers, in exhibitions and tables of statistics; in the flat, in relief, or on the lecturer’s lantern screen. There it is with the eastern boundaries long drawn out, with thin lines marking the seceded territories and dotted lines round Austria and the other German-speaking districts. As an expression of Fate and the play of forces this conglomeration of lines and contours is a more potent and more up-to-date symbol than is the flag with all its emotional significance. (Diesel, Citation1931, p. 13)

The fasces and swastika, like the flag, are defined in dictionaries as emblems (NOAD, Citation2005, flag, fasces, swastika) and by extension, as Diesel suggests, the map had gained something of the same status as an emblem of the nation/state. However, the case of Slesvig-Holsten/Schleswig-Holstein illustrates how more than a map was needed to give emblematic substance to the territory of a nation/state, because the map provided no easy solution to where one should draw the borderline in a situation where there was a mix of languages and different identities blended into one another in an uneven way. If the Eider River between historically Danish Slesvig and historically German Holstein was chosen as the border, a preponderance of German speakers would be left within Denmark in the southern part of Slesvig. If Slesvig was divided, creating a predominantly Danish northern Slesvig and a predominantly German southern Schleswig, given the language mix the question arose of where to draw the line and on what basis? For many Danish nationalists the solution lay in asserting a tangible, emblematic line of demarcation that would give them an ancient historical entitlement to Slesvig and thereby define non-Danes as invasive aliens in a Denmark defined in terms of blood and space (Olwig, Citation2003). That emblematic boundary became Dannevirke (), a line of ancient fortifications crossing Slesvig north of the Eider that the Danes believed marked the southern boundary of the ancient Danish landskab of Sønderjylland (South Jutland; Olwig, Citation2008). A characteristically emblematic encapsulation of Dannevirke’s appeal is found in the image on the masthead of the eponymous Danish nationalist Slesvig weekly newspaper Dannevirke with its architectonic entryway into the dawning rebirth of the new national landscape of Denmark as written in stone in mystic Nordic runes.

Figure 2. Masthead of the Danish nationalist Slesvig weekly newspaper Dannevirke. ‘Danmark’ is written on the rune stone in runic letters in the style of those on the Jelling rune stones. (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dannevirke_ugeblad.jpg. Accessed 17 December 2020)

Emblematic Sønderjylland

The Danes had no native heritage of ancient Greco-Roman architectural monuments such as those that inspired the emblematic tradition in southern Europe and Britain, but they did have ancient Nordic gravemounds, dolmens and rune stones that played an emblematic role as expressions of an ancient Danish heritage inspiring the rise of a modern Danish nation/state encompassing all or part of Slesvig. The most iconic are the tenth-century Viking age rune stones placed between two huge gravemounds and the Medieval Church at Jelling in Jutland (Jylland in Danish) () which had been given emblematic importance already in 1597 in the first topography and map of Jutland. These rune stones are popularly known as ‘Denmark’s birth certificate’ because they contain the oldest written Danish reference to Denmark and refer to the foundational unification and Christianisation of Denmark. The older stone states it was raised by King Gorm the Old in memory of his wife Thyra, whereas the newer stone reads: ‘King Haraldr ordered this monument made in memory of Gormr, his father, and in memory of Thyrvé, his mother; that Haraldr who won for himself all of Denmark and Norway and made the Danes Christian.’ According to a long-standing myth Queen Thyra built Dannevirke, making it possible to create an imagined link between King Harald’s unification of Denmark and his mother’s fortification of a presumed Danish southern border. In this way Dannevirke and the ancient monuments of Jelling became interlinked in an emblem of the territory of a supposed ancient Danish nation/state with a clearly marked spatial border at Dannevirke (). Denmark, in other words, was emblematically constructed as both a nation, definable as ‘a large body of people united by common descent, history, culture [Christianity], language and inhabiting a particular country or territory’ (NOAD, Citation2005, nation), and as an ancient territorial state—even though the nation/state as a territorial entity did not emerge until centuries after Harald. The emblematic power of Dannevirke was so great that the Danes believed that, if refurbished, the fortification would be impregnable, so when in 1864 the Prussians went to war over the border issue, Denmark had concentrated its troops at Dannevirke. Denmark was forced to make a deadly hasty retreat, eventually losing the war and all of Schleswig/Slesvig, along with Holstein/Holsten, to Prussia.

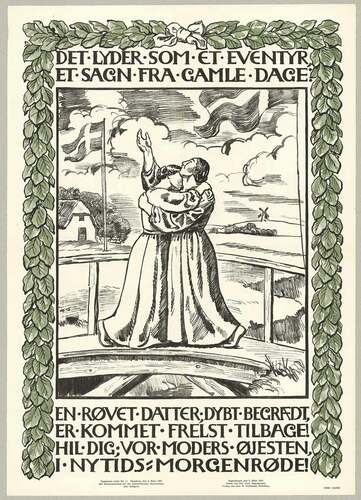

After Germany suffered defeat in World War I, Denmark regained the northern portion of Slesvig following a 1920 plebiscite in which the population was asked to vote for inclusion in either Germany or Denmark. The posters and artworks published in connection with the plebiscite and ‘reunification’ with Denmark drew heavily on the emblematic representation of the Danish nation/state that was produced during the years of conflict that preceded the plebiscite. This is illustrated by the 1920 poster celebrating the reunification of Northern Slesvig with Denmark (). The image, a drawing by the prominent artist Joakim Skovgaard, combines classic emblematic figures of Danish national identity, such a farmhouse with a thatched roof, a traditional windmill and Danish flags waving in the wind. It shows the reunion through the figures of two women embracing each other: the young daughter (Sønderjylland) who is crossing the river demarcating the northern border of Sønderjylland back to Denmark where she is welcomed by ‘Mother Denmark’.

Figure 3. ‘Det lyder som et eventyr’, The Royal Library, Copenhagen, Creative Commons, http://www5.kb.dk/images/billed/2010/okt/billeder/object154963/da/. Accessed 20 September 2020. The text, by Nobel prize winning Danish author Henrik Pontoppidan, reads in English translation: ‘It sounds like a fairy-tale, a saga from olden days: An abducted daughter, deeply mourned, is rescued and returned! Hail you; our mother’s beloved, in the dawn of a new time.’ The poster was printed a few days before the plebiscite in South Slesvig on March 14

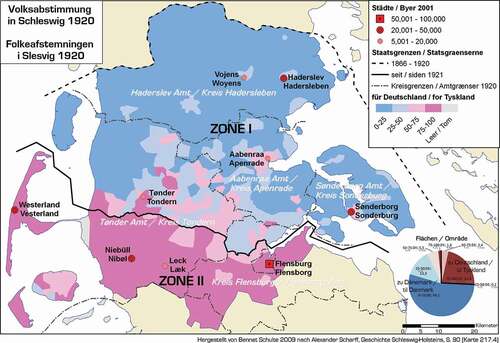

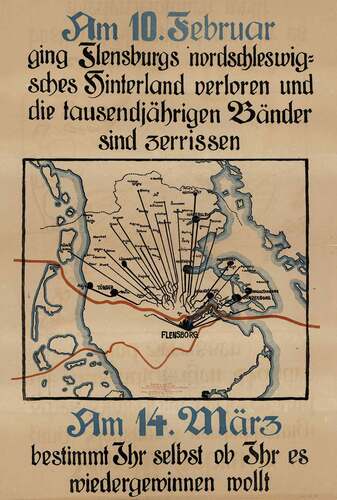

The plebiscite demonstrated the difficulty of representing national affiliation in cartographic space with sharply drawn border lines. Due to the admixture of languages many individuals could be unsure of their national identity. Moreover, the gulf between the predominance of German speakers in the cities and Danish speakers in the countryside created a situation in which large areas of the more thinly populated countryside would go to Germany if cities and their hinterland were incorporated within the same voting district. Thus, in order for the Danes to gain as much territory as possible in northern Slesvig, the voting districts were so constructed that, for example, the predominantly German speaking city of Flensburg/Flensborg was kept separate from much of its rural hinterland and vice-versa (). The figures resulting from a plebiscite that forced people to choose between two identities were then plotted into the space of the map and into to the graphic space of statistical graphs and charts. The rational geo-metry of the map gave the impression of an impartial and just, objective, statistical and quantifiable vote. But was it ‘just’ that the resultant borderline between the two nation/states separated family members and friends (including those from different language backgrounds) living on different sides of the border and that it hindered the new Danish citizens from maintaining their ties to the important metropole of Flensburg/Flensborg (). This situation was not alleviated until the joint membership of the Danes and Germans in the European Union brought free cross-border movement. This open border, however, has continued to be opposed by influential Danish nationalistic political parties, for whom the map and the border remain emblematic of the nation.

Figure 4a. Map showing the 1920 plebiscite voting zones north and south of Flensburg, the area’s largest city. The stippled line to the north represents that Danish-German border between 1864 and 1920, and the solid line just north of Flensburg/Flensborg represents the border fixed in 1920. In most of Zone I only 0–25% voted for German nationhood, whereas in most of Zone II between 75–100% voted for German nationhood. The pie chart shows how many, in areal terms, voted Danish or German. In Zone I place names are spelled in Danish first, and in Zone II in German first. (This file is licenced under https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Abstimmung-schleswig-1920.png Bennet Schulte, CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported licence. Accessed 17 December 2020)

Figure 4b. Danish poster (written in German) distributed by the Danes after the 10 February plebiscite vote within Zone I gave Denmark suzerainty over northern Slesvig. The vote for Zone II was to be held March 14, and the Danes wished to convince the population of Zone II to vote Danish because otherwise a huge area of Flensburg’s hinterland (as shown on the map) would be severed from Flensburg. Zone II nevertheless went to Germany. (https://www.flickr.com/photos/statensarkiver/11802739954/in/photolist-iYY8rU-iYXim4-iYW2mT-iYZUL1-iYW1TP-iYZUmd-iYW1XX-iYY87q-iYW28M-iYZUCW-iYW2tr-iYY89E-iYY8os-eF9K9F-iYZUvm. Danish Royal Archives, Creative Commons. Accessed 17 December 2020)

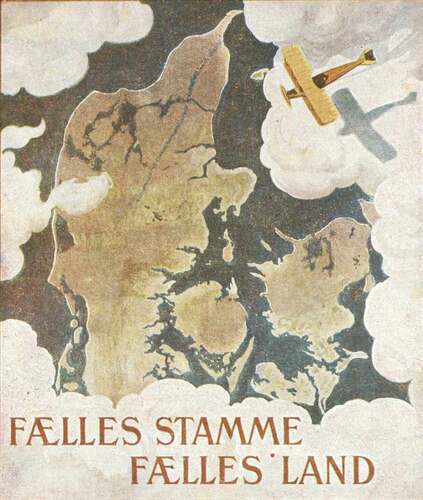

Figure 4c. Danish 1920 voting poster. It combines a view of Denmark seen from an airplane as a map with a text that reads in English: ‘COMMON NATION/TRIBE, COMMON LAND’. It fuses the nation as a people of common descent that is embodied within the cartographic space of the mapped territory, which in turn is conflated with the material shape of the land itself, as imagined to appear to the eye as seen from an impossibly high-flying biplane. (Poster located in the Royal Danish Library’s Picture Collection, http://www5.kb.dk/images/billed/2010/okt/billeder/object154868/da/. Accessed 17 December 2020)

Figure 5 a.The top of the aerial photo shows the Voldsmose public housing estate, and below, separated by multi-lane road, an area of parcelhuse outside the city of Odense. Google Earth, accessed 18 September 2020

Figure 6. Emblematic Jelling as it is seen today from the top of the left gravemound, with both rune stones, encased in glass, by the church door, and a Danish flag waving behind it. The church is surrounded by family graves located in typical Danish hedged-in square parcels well-tended with greenery and flowers. Many also include natural looking, rune stone style gravestones

Figure 7. The centre-liberal former Prime Minister, Lars Løkke Rasmussen, on a visit to Vollsmose in 2015 ‘to have a chat with the residents about the values of the Danish society’. Photo: Jens Astrup. (https://www.flickr.com/photos/49542087@N05/18680288665. Creative Commons Attribution-non-commercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0). Accessed 17 December 2020)

The struggle to return all or part of Slesvig to Denmark as Sønderjylland helped create an emblematic image of the Danish nation/state that was particularly expressed in , 4a, 4b and 4c. These figures display an amalgam of emblematic elements going back in history, including maps, landscape scenes, ancient structures, texts carved in stone and iconic human figures, the common denominator being the fusion of the geo-metric and the bio-organic. The plebiscite’s determination of a fixed southern border defined Denmark both geo-metrically in cartographic terms as a state and bio-organically as a people thereby creating a bio-spatial nation/state descended from the emblematic ancient Danes. It became an historical cornerstone of Danish self-understanding, as fostered by national romantic landscape art and poetry, that Denmark is a culturally homogeneous, egalitarian country (Olwig & Paerregaard, Citation2011) with deep roots in a landscape of family farms, as depicted in the poster welcoming a South Jutland family back to the mother land in 1920 (). This landscape, however, was associated with a national liberal political rural ideal and already by the late nineteenth century it was being challenged by the growth in Denmark of an urban-industrial society and an associated Social Democratic political movement.

The emblematic modern Danish nation-state

The homogeneous parcelhus landscape of the contemporary Danish nation-state

Industrialisation and urbanisation resulted in an influx of rural Danes to the urban centres where many ended up in cheaply built, dense and unhealthy slums. During the 1930s, major social welfare legislation was passed in which improvement of housing became an important component (Henning, Citation2013). One initiative took the form of loans to families with many children so that they could acquire a small, but well-constructed and healthy house with a small garden. These homes, known as parcelhuse were typically built outside the urban centres on land parcelled out of former farmland and with their grassy lawn and often with a flagpole where the Dannebrog is flown for holidays and birthdays they can be seen as a renewal of the nationalist rural ideal in a modern, suburban context. They have had a huge impact on the modern Danish landscape. Thus during the 1960s, when Denmark experienced a period of economic growth, there was an explosion in the building of parcelhuse (Bolius, Citation2004) and today more than a million parcelhuse are inhabited by about 50% of the Danish population of about 5.5 million (Jensen et al, Citation2016, p. 8). The parcelhus has been described as ‘one of the welfare society’s symbols of human happiness and an expression of the ideal living arrangement’ (Bolius, Citation2004). The houses have grown bigger since the 1930s, but they continue to provide domestic space for the ‘typical’ Danish family, defined as a unit of father, mother and two child(ren) (Boding, Citation2017). The houses are usually clearly separated from one another by well-trimmed hedges, high enough to provide privacy for the family members without shading the neighbours’ plots. The parcelhus landscape has thus become emblematic of an homogenous, egalitarian middle-class Danish welfare society, perceived as a unity of family entities within a bordered and enclosed homogenous national space ( & ). The Danish neighbourhood of parcelhuse bears a certain physical, but also emblematic, resemblance to similar suburban developments in other countries. This is in line with the common characteristic of the emblem that it travels and can be adapted to suit differing conditions. The Danes, however, are perhaps unusual in that they not only tend to live their daily lives in parcelhuse. Many also have smaller scale ‘summer houses’ in similar developments in areas by the sea, designated popularly as ‘the summer land’. Furthermore, at an even smaller scale, others have ‘colony gardens’ on the outskirts of cities. Furthermore, Danes are often buried in similarly structured burial plots, at an even smaller scale still ().

In recent decades, the enclosed, hedged-in family plot can be seen to have attained broader emblematic significance as expressed in the notion of familien Danmark, ‘the family of Denmark’. The everyday life of the family of Denmark has been described as revolving around ‘the close and the traditional’, preferring ‘the home-like to the foreign, the habitual and known to the new and unknown […], Danish meatballs to carpaccio’ (Geomatic, Citation2015). The emblematic family of Denmark, the anthropologist Mikkel Rytter observes, has come to connote:

‘coherence, solidarity and security, but it is also associated with peacefulness, cosines and happiness – all values found in the ideal family. Evoking the notion of ‘the family of Denmark’ in public discourse is a way in which to speak of average people such as Jensen, Hansen or Olsen without differentiating among them or accentuating one over the others’ (Rytter, Citation2011, pp. 60–61).

This idea of the ‘family of Denmark’ has become extended to refer to the Danish population as such, and the little single-family home located on its own, well-bordered plot of land has come to signify the peaceful, cosy, secure, cohesive nation/state of Danes.

The emblematic national romantic landscape has also been modernised, and Jelling, with the rune stones, the ancient grave mounds and the medieval church, remains at its core. It has now been named a UNESCO world heritage site, its rune stones encased in glass climate-controlled boxes, and an adjacent state-of-the-art interpretive museum has been architected for the nation’s edification (). Jelling often appears on the tests taken by those who apply for permanent Danish residency or citizenship, and it therefore still functions as a kind of national (re)birth certificate, the knowledge of which is regarded as vital to anyone wishing to live permanently in Denmark.

The ‘ghetto’—a negative emblem

Industrialisation also brought with it an internationally inspired left-wing,socialist labour movement that in the late nineteenth century began to establish building societies in order to improve housing for the workers. With little state support, they had limited impact, but during the 1930s, when housing became an integral part of Danish social welfare policy, the state also began to support the building of good quality, affordable rented apartments for low-income families outside the city centres, managed by housing associations (Henning, Citation2013). Most of the present-day social housing was constructed in the period from the 1950s to the late 1980s and today about 17% of the population live in these apartment complexes (Social- og Indenrigsministeriet, Citation2016). Built in an international modernist style that is the antithesis of the national emblematic Danish landscape of the parcelhus, they were intended to provide attractive homes for Danish families. For many Danes, however, the housing estate has primarily become a place to live before being able to purchase one’s own home, which for the majority is likely to be a parcelhus. An increasing number of immigrants and refugees have therefore moved into the social housing estates that they regard as environments with desirable modern facilities where they can live with close relatives and co-ethnic friends.

One of the most well-known housing areas with many immigrants and refugees is Vollsmose located on the outskirts of Odense. According to the Vollsmose Secretariat (Vollsmose Sekretariat, Citation2020), the new suburb was envisioned in the 1960s as being both an extension of the city and a separate, planned entity, equipped with its own facilities, such as day-care institutions, schools, recreational facilities, library, shopping centre and Lutheran church, and interlinked by pedestrian and bicycle paths. The idea was that it would be a self-contained ‘satellite city’ with high quality housing for the growing Danish middle class. However, the apartments proved difficult to rent due to the increasing popularity of parcelhuse and the municipality therefore began to allocate the empty apartments to immigrants, refugees and welfare recipients. What was intended to be a desirable, modern Danish community became perceived as a foreign area inhabited by people with alien customs, languages and religious practices. Many other social housing areas underwent a similar development, bringing about a situation, not unlike that in Slesvig, but at the scale of a housing estate, in which foreigners were seen to have appropriated parts of an ideally homogenous Danish territory and developed their own ‘parallel societies’ (Socialministeriet, Citation2010) (see ). As expressed by the philosopher Etiénne Balibar in a broader context, the areas became viewed as representing the intrusion of a threatening modern world ‘in which topological and political distinctions of the interior and the exterior are becoming increasingly difficult to maintain in a simple way, or can never be taken for granted, as the institution of the nation state would have it’ (Balibar, Citation2017, p. 34).

The Danish government has reacted to this development by instituting increasingly strict legislation on immigration and integration. During the 1990s and early 2000s it targeted especially family migration which was suspected of enabling chain migration through arranged (often called forced) marriages and reunification with ‘fake’ children which was seen to hinder proper integration into Danish society. The Somali refugees’ efforts to obtain reunification with their children offer a case in point.Footnote2 Somalis began to enter Denmark as refugees in the early 1990s and today there are more than 20,000 in the country, most of whom live in social housing areas. Their efforts to establish a Somali family life through family reunification have come to demarcate their un-Danishness and un-belonging in Denmark. By Danish law, family reunification is restricted to members of the nuclear family, i.e. a spouse and children below 18 years of age. This family form is very different from the Somalis’ more extensive family relations and sense of responsibility towards relatives, especially children in need. Before they fled to Denmark, many Somali refugees thus had cared for, or even reared, children whose parents were deceased or in other ways incapacitated. They therefore claimed these children as their own when applying for family reunification. This led, in the mid-1990s, the immigration authorities to begin biometric (DNA) testing of the children in order to detect those who were not the biological offspring of Somalis in Denmark. In this way the Danish authorities essentially superimposed a bio-genetic-metric border on the cartographic border to halt the immigration of ‘falsely’ claimed children. This has been at a rather high cost for the informally adopted, non-biologically related children who have been denied reunification with their de facto parents in Denmark.

Despite the Danish authorities’ attempt to gain some control over the social housing developments, their bio-genetic landscapes have not changed markedly. Most refugees and immigrants do not have the financial capacity to purchase a house nor the desire to buy into the ethnically homogenous enclosed Danish single-family home ideal and leave the varied multi-ethnic community of the social housing areas. The Danish government therefore introduced more radical measures to cleanse the ‘alien’ settlements within the social housing areas with publication in 2010 of the report, Ghettoen tilbage til samfundet. Et opgør med parallelsamfundet i Danmark (The Ghetto back to the society. A show-down with parallel societies in Denmark), that designated 29 social housing estates as problematic ‘ghettoes’ (Socialministeriet, Citation2010).

The cover () depicts the façade of an apartment building which is partly hidden by a dark blue cloud-like figure in which the title of the ‘ghetto’ report is placed. Below is a light green circular figure in which the publisher, the government, is located. The colours on the cover correspond with the colours on a map in the report showing the location of the ‘ghettoes’—Denmark is depicted as light green and the areas with ‘ghettoes’ as dark blue circles of varying size, depending on the number of ‘ghettoes’ in the implicated municipalities (). The circles in the three largest Danish cities of Copenhagen, Aarhus and Odense are so big that they seem to cover the entire urban area. The report is illustrated with photographs showing modern apartment buildings where the windows are equipped with satellite dishes indicating homes tuned in to foreign TV-stations; people of varying ethnic background, several wearing veils indicating their Muslim faith, and Danish police keeping an eye on things. The report explains that the ‘ghettoes’ are identified on the basis of their high proportion of residents who are (1) unemployed and with little or no education, (2) immigrants or descendants of immigrants from non-western countries, and (3) convicted of crime. A statistical table substantiates the magnitude of these characteristics. Vollsmose, with 3,591 rental units the most extensive housing estate in Denmark, holds a prominent position in the statistics with 67.7% residents of non-Danish background, 54.4% without educational or employment affiliation, and 373 persons convicted of a crime per 10,000 inhabitants (Socialministeriet, Citation2010, p. 39). Along with other highly profiled housing estates, the housing development was designated as a major problem area, a position which is affirmed annually by the official updating of the ‘ghetto lists’ based on new statistics. The gloomy ‘ghetto’ image, presented in the government documents, has also been prominent in the Danish media. Thus a survey of news items on Vollsmose in major national newspapers showed that, within the span of one year, almost two thirds focused on crime and terror, whereas a third dealt with integration issues, such as ‘ghetto’ problems, poverty and social issues, as well as topics related to the Muslim religion. Vollsmose, the author concluded, had become an ‘ikon’ of crime and other social evils (Nielsen, Citation2018, pp. 5–6).

Figure 8 a.Cover from the Social Ministry’s ghetto report, 2010, reproduced with permission from the Ministry of Immigration and Integration Affairs and the Ministry of Social Affairs. Accessed 17 December, 2020

Figure 8 b.Map from the Social Ministry’s ghetto report, 2010, reproduced with permission from the Ministry of Immigration and Integration Affairs and the Ministry of Social Affairs. Accessed 17 December, 2020

At a more general level it can be argued that Vollsmose and other highly profiled ‘ghettoes’ that are represented in the form of devastating statistics, alienating images and critical texts, have become a ‘negative emblem’ of everything that does not belong in Denmark. Through their ‘repetition of stock themes and motifs with only minor literary or iconographic variations’, the literary scholar Sara Grieco states (1994, p. 795), negative emblems can reproduce and affirm particular morals and social norms that discredit certain segments of the population. It does not matter that the elements in the emblem presented as facts, such as the statistical data, may be manipulated and biased (Det kriminalpræventive Råd, Citation2019; Nielsen, Citation2019). They are accepted because they are shaped by particular social ideologies and ‘vested interest’ that maintain a dominant social order (Grieco, Citation1994, p. 799). In this case, the negative emblem of the ‘ghetto’ serves to uphold the imagined socio-culturally homogeneous Danish nation-state in a modern globalising world.

The negative emblematic status of the social housing areas has had major consequences for the local residents’ quality of life in terms of not only their sense of their more general personal belonging in Danish society but also the concrete basis of their everyday life. Thus, in 2018, the government announced that the political strategies to ‘integrate’ the ‘ghettoes’ into Danish society, and thereby presumably solve the social problems associated with them, had failed. It therefore mandated that it is necessary to tear down some of the buildings in the ‘hard ghettoes’, with the strongest concentration of foreigners, the highest rates of crime and unemployment and the lowest educational levels, in order to disperse the residents. In the vacated areas new low-rise housing would be built that could appeal to socially and economically resourceful (primarily ethnically Danish) buyers. On the map, and on statistical graphs this was seen as a way to create a more cohesive society, but this attempt at integration of perceived ‘un-Danish’ elements was essentially geo-metrical and bio-organic, not social or cultural. Indeed, a report by the State’s Building Research Institute concluded that there was no clear evidence that dispersal would solve the social problems identified (Jepsen & Nielsen, Citation2018, p. 18). Nevertheless, plans were prepared for the eradication of the ‘ghettoes’. The Vollsmose plan published in the spring of 2019 showed that ca. 1000 apartments would be torn down, forcing as many as 3,000 of the inhabitants to relocate to make room for new largely privately-owned housing (Sass & Ahlmann-Petersen, Citation2019). In order for the plan to work, it would be necessary to change the perception of the housing estate from a highly negative to a positive one and the municipality was already at work attempting to rebrand the area as a ‘hip’, multicultural urban neighbourhood (Nielsen, Citation2018).Footnote3 While many residents of Vollsmose recognised that there were problems in the area, they did not see the demolition of well-constructed and sound buildings as the solution. As one (ethnically Danish) resident said, ‘It’s completely senseless.Footnote4 It is treatment of the symptoms of a failed social policy’ (Møller et al., Citation2019).

Conclusion

The modern idea of landscape, as Cosgrove, Daniels and others have argued, evolved out of Renaissance cartographic and perspectival techniques, developed largely in the context of art and architecture, as a spatial representation of places, real or imagined, that were perceived as landscape. In this article we have examined the emblematic landscape that emerged also in the Renaissance, but which was rather concerned with the landscape of ideas and moral lessons. Together, these two approaches help to comprehend how ideas and values, such as those of nationalism, become attached to the landscape of places, and how this can affect landscape planning and design. Whereas landscape researchers have tended to focus on particular aspects of landscape, such as its visual, textual or cartographic representation, its architectural design and its physical, biological or social content, there has been little interest in the emblematic dimension. This article has shown that the emblematic combines these differing aspects of landscape in a powerful holistic synergy expressive of ideas and emotions that tend to take on a life and agency of their own, as when a centuries old region is divided between two nation/states according to ‘blood and space’ criteria, or when good quality housing is to be levelled and residents displaced to create the appearance of a more socially homogenous national space. Much of the power of the emblematic nation/state lies in its ability to fuse the bio-organic identity of the nation’s people with a geo-metric, mapped identity of the state’s territory identified with the laws of geometric space. The rationality of the maps and the quantitative and qualitative figures used seem to legitimise as just the emblematic landscapes of the nation/state. The result, nevertheless, can be perceived to be an unjust destruction of the quality of life of the people who dwell in these emblematic, or negative emblematic, landscapes. This was shown in the case of the carving up of Schleswig-Slesvig along nationalist lines, and in the example of the planned demolition of the landscape of Vollsmose. This article has traced the way the emblematic landscape can be seen to have affected the construction of a modern nation/state that, despite having achieved democratic rule and peace with its neighbours, nevertheless perpetuates and celebrates its emblematic roots in a history that previously brought war and destruction and now results in the demolition of people’s homes and neighbourhoods.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kenneth R. Olwig

Kenneth R. Olwig is a Professor Emeritus of Landscape Planning at the Department of Landscape Architecture, Planning and Management, The Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU). He has also worked in geography and planning departments in Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the USA. He has furthermore been a research fellow at advanced research centres in Denmark, Norway, and California. His interests focus on a combination of aesthetic, legal, literary, and cultural geographical approaches to landscape and place, and the relationship between society and nature. Most recently he has been especially concerned with landscape justice, landscape democracy, and landscape citizenships. These issues are the topics of two monographs: Nature’s Ideological Landscape (1984) London: Allen & Unwin; Landscape, Nature and the Body Politic (2002), Madison: University of Wisconsin Press; and The Meanings of Landscape (2019), London: Routledge. He has also co-edited three book collections: with Don Mitchell, Justice, Power and the Political Landscape (2008), London: Routledge; with Michael Jones, Nordic Landscapes: Region and Belonging on the Northern Edge of Europe (2008), Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; with David Lowenthal, The Nature of Cultural Heritage, and the Culture of Natural Heritage: Northern Perspectives on a Contested Patrimony (2015), London: Routledge.

Karen Fog Olwig

Karen Fog Olwig is Professor Emeritus at the Department of Anthropology, University of Copenhagen. Most of her research has concerned family and kinship within the context of voluntary and forced migration with particular focus on the Caribbean, Britain and Denmark. Her most recent publications include: The Biometric Border World. Technology, Bodies and Identities on the Move, co-authored with Kristina Grünenberg, Perle Møhl and Anja Simonsen, Routledge, 2019; The Right to a Family Life and the Biometric ‘Truth’ of Family Reunification: Somali Refugees in Denmark, Ethnos, 2020, DOI: 10.1080/00141844.2019.1648533; New Neighbours in a Time of Change: Local Pragmatics and the Perception of Asylum Centres in rural Denmark. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, co-authored with Zachary Whyte and Birgitte Romme Larsen, 2018. DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2018.1482741.

Notes

1. For a theoretical treatment of this conflicted relationship see (Balibar, Citation1990).

2. The following is based on (Olwig et al., Citation2020) and (K. F. Olwig, Citation2020).

3. For another example of a marginal area with shifting positive and negative emblematic status, see Allen’s analysis of the representation of the Brasilian favela in documentary films.

4. ‘Hul i hovedet’, literally ‘hole in the head’.

References

- Allen, A. (2013). Shifting Perspectives on Marginal Bodies and Spaces: Relationality, Power, and Social Difference in the Documentary Films Babilônia 2000 and Estamira. Bulletin of Latin American Research, 32(1), 78–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-9856.2012.00702.x

- Balibar, E. (1990). The Nation Form: History and Ideology. Review (Fernand Braudel Center), 13(3), 329–361.

- Balibar, E. (2017). Reinventing the Stranger: Walls all over the World, and How to Tear them Down. Symplokē, 25(1–2), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.5250/symploke.25.1%2D2.0025

- Boding, J. T. (2017) Nye huse er blevet næsten dobbelt så store på 60 år. Bolius. https://www.bolius.dk/nye-huse-er-blevet-naesten-dobbelt-saa-store-paa-60-aar-40954/, Accessed August 18, 2018.

- Bolius (2004) Parcelhusets historie – 1930ʹerne til 1870ʹerne. https://www.bolius.dk/parcelhusets-historie-1930erne-til-1970erne-17118, Accessed August 18, 2018.

- Cosgrove, D., & Daniels, S. (Eds.). (1988). The Iconography of Landscape. Cambridge University Press.

- Det kriminalpræventive Råd (2019) Kriminalitet og Etniske Minoriteter. www.dkr.dk, accessed September 16, 2020.

- Diesel, E. (1931). Germany and the Germans. Macmillan.

- Geomatic. (2015) . Geodemografisk klassifikation Danmark. Operationel adgang til viden. Center for geoinformatik. https://conzoom.dk/media/2326/conzoom-klassifikation-dk-g5-15.pdf, Accessed August 18, 2018.

- Grieco, S. F. M. (1994). Georgette de Montenay: A Different Voice in Sixteenth-Century Emblematics. Renaissance Quarterly, 47(4), 793–871. https://doi.org/10.2307/2863217

- Henning, B. (2013). Boligpolitikkens historie – Et upåagtet forskningsområde. Historisk Tidsskrift, 106(2), 586–614. https://tidsskrift.dk/historisktidsskrift/article/view/56255

- Hunt, J. D. (1971). Emblem and Expressionism in the Eighteenth-Century Landscape Garden. Eighteenth-Century Studies, 4(3), 294–317. https://doi.org/10.2307/2737734

- Jensen, J. O., Bräuner, E., Gram-Hanssen, K., Hansen, A. R., Larsen, J. N., & Stensgaard, A. G. (2016). Parcelhusatlas: En kortlægning af danske parcelhuse og deres ejere. SBI 2016:16. https://vbn.aau.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/235314204/SBi_2016_16.pdf, Accessed August 18, 2018.

- Jepsen, M. B., & Nielsen, R. S. (2018). Ufrivillig fraflytning fra social boligområder. Statens Byggeforskningsinstitut, Aalborg Universitet, SBi 10. https://sbi.dk/Pages/Ufrivillig-fraflytning-fra-udsatte-boligomraader.aspx, Accessed August 20, 2020.

- Merriam-Webster.com 2020. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/emblem, Accessed September 20, 2020.

- Moffitt, J. F. (2004). Introduction. In A. Alciati (Ed.), A Book of Emblems: The Emblematum Liber in Latin and English (pp. 5–14). McFarland.

- Møller, J. G., Bjerg, L., & Odorico, C. (2019). Næsten 3,000beboere fra Vollsmose skal genhuses. DR Fyn, https://www.dr.dk/nyheder/regionale/fyn/naesten-3000-beboere-fra-vollsmose-skal-genhuses, Accessed August 6, 2020.

- Nielsen, H. L. (2018). Den sidste Vollsmoseplan. Kan Danmarks største ghetto normaliseres? In Videncenter om det moderne Mellemøsten, December.

- Nielsen, H. L. (2019). Ghettopakken: Integrationsfremme eller social engineering? In Videncenter om det moderne Mellemøsten, 2019.

- NOAD. (2005) . New Oxford American Dictionary. E. McKean, Oxford University Press.

- Oakley, S. (1972). A Short History of Denmark. Præger.

- Olwig, K. F., & Paerregaard, K. (2011). Integration. ’Strangers’ in the Nation. In K. F. Olwig & K. Paerregaard (Eds.), The Question of Integration (pp. 1–28). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Olwig, K. F. (2020). The Right to a Family Life and the Biometric ‘Truth’ of Family Reunification: Somali Refugees in Denmark. Ethnos, https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2019.1648533

- Olwig, K. F., Grünenberg, K., Møhl, P., & Simonsen, A. (2020). The Biometric Border World: Technologies, Bodies and Identities on the Move. Routledge.

- Olwig, K. R. (2002). Landscape, Nature and the Body Politic. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Olwig, K. R. (2003). Natives and Aliens in the National Landscape. Landscape Research, 28(1), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426390306525

- Olwig, K. R. (2008). The Jutland Cipher – Unlocking the Meaning and Power of a Contested Landscape. In M. Jones & K. R. Olwig (Eds.), Nordic Landscapes: Region and Belonging on the Northern Edge of Europe (pp. 12–49). University of Minnesota Press.

- Rytter, M. (2011). ‘The Family of Denmark’ and ‘the Aliens’: Kinship Images in Danish Integration Politics. In K. F. Olwig & K. Paerregaard (Eds.), The Question of Integration: Immigration, Exclusion and the Danish Welfare State (pp. 54–76). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Sandiford, K. A. P. (1975). Great Britain and the Schleswig-Holstein Question 1848–64: A Study in Diplomacy, Politics, and Public Opinion. University of Toronto Press.

- Sass, U., & Ahlmann-Petersen, C. (2019). Ny plan afslører: Mere end hver tredje bolig forsvinder fra Vollsmose. Fyens Stiftstidende. https://fyens.dk/artikel/ny-plan-afsl%C3%B8rer-mere-end-hver-tredje-bolig-forsvinder-fra-vollsmose, Accessed May 8, 2019.

- Social- og Indenrigsministeriet. (2016) Almene boliger i Danmark. Velfærdspolitisk Analyse 3, Accessed August 18, 2020.

- Socialministeriet. (2010). Ghettoen tilbage til samfundet. Et opgør med parallelsamfund i Danmark. Oktober 2010:34.

- Vollsmose Sekretariat. (2020). Vollsmoses historie. https://vollsmose.dk/vollsmose-sekretariatet/presse/vollsmoses-historie/, Accessed August 4, 2020.