Abstract

This paper seeks to expand mainstream descriptions of accessibility as a characteristic of materialities and infrastructures, inscribed into them at the design stage. Instead, it explores accessibility as a practice. That is, as the outcome of ongoing everyday interactions taking place between disabled and non-disabled users encountering materialities and accessibility-oriented protocols. Accessibility is framed as a relational achievement in which the practical action of those who routinely navigate public transport infrastructures locally enact heterogeneous landscapes of accessibility. The paper draws on qualitative data of disabled people using the public transport system of Santiago de Chile. Through an ethnomethodological analysis of video recordings and ethnographic work, the interaction between disabled and non-disabled passengers and infrastructures is put in context, revealing the embodied skills and interactional work that people do in order to enact accessible situations for themselves and for others.

Introduction

It’s 6:40 pm in Santiago, near the Tobalaba Metro Station. I am early for my meeting with Natalia, but this is intended on my part. Last time we met, we had some trouble finding our way around the city centre, since Natalia’s electric wheelchair is not always accommodated by the material surroundings. This time, I wanted to make sure we would be able to locate a suitable spot for our interview. She turns up punctually at 7:00 pm, and I have already found a comfortable table outside a café. We chat over coffee about her first experiences using an electric wheelchair, years ago. We need to wait until Tobalaba station has cleared up a bit before our journey together. Peak hour tends to be particularly bad on Fridays. Natalia prefers to kill some time before venturing down into the crowded and suffocating underground.

We find the lift down to the station’s foyer. We are the only ones waiting for it, but I hesitate. More stations have recently been equipped with lifts like these as part of an accessibility policy by Metro, which has ignited controversy around who is and is not entitled to use them. Non-disabled people attempting to use the lift are sometimes subjected to public scorn, and media coverage has tended to cast a light of scandal over the issue. I am still not sure what my position is on the matter, but I do worry about not being able to quickly find Natalia if we go down to the station through different entry points. The lift arrives. Natalia goes in and I follow after her. The doors close behind us. As we descend, Natalia tells me that she finds this lift more comfortable than the one across the street, slightly out of her way. This reminds me that it has not been that long since disabled people have been able to navigate Santiago’s public transport system, let alone having preferred routes and points of access. Santiago’s bus and underground systems have changed, and dramatically so, for this to have become a reality. I look around and internally wonder ‘How did this lift get here?’ … (Field notes, 7 April 2017).

This paper focuses on the issue of accessibility, and on the collection of things and practices that make it emerge. For Santiago’s public transport (also known as Transantiago) to offer an ‘accessible’ experience to someone like Natalia, a significant number of things had to been set in motion. From its beginnings in 2007 and leading up to its current state, Santiago’s public transport system has mobilised policies and design standards aimed at enacting an ‘accessible’ public transport service. Accessibility has made its appearance, or rather, it has been slowly made to emerge by legal and technological devices, as well as by the users’ everyday practices.

This paper seeks to engage with contemporary debates of how infrastructures, and processes of infrastructural change specifically, are interleaved with ordinary practices in order to produce (and maintain) accessible socio-technical arrangements in everyday life. Attending to Lawhon et al.’s (Citation2018) concept of Heterogeneous Infrastructure Configurations (HICs), I aim to contribute to an understanding of accessibility as a ‘doing’—as the outcome of ongoing heterogeneous practices, including materialities as well as everyday interactions. The concept of HICs considers infrastructures to be more than individual objects. They also involve relations and capacities, which this article addresses by exploring everyday interactions between users and technologies. With this, I argue for a grounded and practiced notion of accessibility, remaining open to the agency of heterogeneous actors, and not the exclusive purview of technical experts. I draw on the geographical description of space as being constituted through interactions (Massey, Citation2005) in a process of continuous work that is never really finished, in order to show the ongoing and laborious process of Transantiago’s becoming accessible for disabled people. This process is relationally enacted by material implementation, ‘expert’ decision-making, and everyday interaction among public transport passengers. Rather than fixed, static things, infrastructures are arrangements in constant reconfiguration (Graham & McFarlane, Citation2014; Lawhon et al., Citation2018; McFarlane & Silver, Citation2017; Velho & Ureta, Citation2019). Conceptualising Transantiago as a process, rather than as a finished thing, allows us to trace the elements that enable it to become an increasingly more accessible space for disabled people, as well as to acknowledge the effort that the users themselves contribute in order to keep such a transformation happening.

Accessibility has been understood as a feature of infrastructure and devices, designed to grant usability for disabled people. Despite an increasing effort from policy seeking to incorporate disabled people into different forms of participatory design, accessibility is still widely regarded as an element that is delivered to users, portraying disabled people as passive recipients of access (Hamraie & Fritsch, Citation2019). This article illustrates how accessibility for disabled people is always a problem that is locally dealt with, rather than an inherent property of pieces of infrastructure that have been designed to be accessible. The article seeks to re-specify the question of infrastructures - for whom they work - to, to who makes them work. With this, my aim is to frame accessibility as a relational achievement in which the practical action of those who routinely navigate Transantiago locally enact heterogeneous landscapes of accessibility.

I describe these landscapes of accessibility as precarious arrangements that require constant involvement and relational work to exist in everyday life. This article shows that the role of disabled users is much more crucial and active than traditional approaches to accessibility design tend to assume (Winance, Citation2014). The question of how spaces become accessible draws on the notion that users exert influence over the accessible qualities of the infrastructures they interact with (Titchkosky, Citation2011). Thus, while we may accept that ‘large-scale social relationships characteristic of the modern era are, in a large part, made possible by infrastructure’ (Angelo & Hentschel, Citation2015, p. 306), this is also true the other way around. Everyday interactions bring infrastructure into being, enacting it as more (or less) functional, intelligible, or accessible. Whenever possible, as this paper shows, disabled people take part of the infrastructure and ‘make it work’ according to their expectations and needs.

Following what Lawhon et al. (Citation2018) have called a performative approach to infrastructures, I present ethnographic and video data describing a collection of ‘peopled infrastructures’ (Graham & McFarlane, Citation2014; Simone, Citation2004) being enacted as accessible. Building upon this approach, I explore the practiced aspects of infrastructural change (i.e., the constitution of Transantiago as an accessible public transport system) by tracing how material adjustment comes together with ordinary embodied practices, enacting accessible arrangements in everyday life.

Using ethnographic go-alongs and ethnomethodological video analysis, I discuss how accessibility is socially configured through ordinary practices, locally enabling spaces and arrangements that are more suitable for users. This approach opens up opportunities to conceptualise accessibility not as an intrinsic characteristic of objects, inscribed into them at the design stage, but rather as enacted (Mol, Citation2002) in the encounter of materialities and users.

In the following section I draw on contributions from disability studies and infrastructure studies in order to develop a conceptual framework to approach accessibility as the ongoing result of everyday ordinary practices that give shape to heterogeneous landscapes of accessibility. Then, I give details of my methodological approach, and the fine-grained attention to social interaction warranted by video analysis. I then discuss two different empirical cases. The first one, video-based, shows how a lift is enacted as accessible by the local rearrangement of a queue. The second one, based on an ethnographic vignette, explores how the lacking features of certain accessibility devices are compensated by the doings of disabled and non-disabled people.

Conceptualising accessibility as local practice

Launched in 2007, Transantiago was an unprecedently ambitious reform. Its aspiration to modernise, regularise, and standardise Santiago’s public transport provision has been well documented (Ureta, Citation2015). Transantiago’s implementation triggered relevant research analysing the challenges faced by its users, as well as the various tactics that they deploy in order to make sense of both the system and a city in constant transformation (Jirón et al., Citation2016).

Transantiago’s modernising agenda included, among other things, accessibility features for disabled people. From manually activated ramps in its buses, to rigorous design standards for its bus stops, Transantiago sought to be universally accessible by design. The following discussion seeks to highlights the limitations of such approach—focused on one-way provision of accessible infrastructure, rather than recognising the work that users do to locally produce accessible arrangements.

More than removing barriers

Disability used to be widely understood as a condition affecting and limiting specific individuals. The social model of disability (Barnes, Citation1991; Oliver, Citation1990), has been instrumental in overcoming the biomedical perspective, instead viewing disability as the disadvantages produced by barriers socially imposed upon people with impairments. The removal of barriers has since become one of the main foci of attention in the design and implementation of accessible infrastructures.

This process of infrastructural transformation by means of ‘removing barriers’ has showed some limitations. Hartblay (Citation2017) critically analyses how material infrastructures are overdetermined as either ‘bad’ or ‘good’, and identifies a treatment of ramps as ‘tokens’ of accessibility. Following modernist infrastructure ideals (Nilsson, Citation2016; Silver, Citation2016), accessibility has been predominantly regarded as a state of barriers-free infrastructures, potentially attainable through the application of adequate design standards. Participatory design has challenged the importance of design standards, seeking the input of disabled people as ‘expert users’ instead. However, understanding accessibility as a feature of ‘well-designed’ infrastructures remains a problematic, widely accepted assumption. An attentive observation of the everyday practices of disabled users of Transantiago reveals accessibility not as an intrinsic, static attribute of infrastructure, but an achievement made possible by the active role that (disabled) people have in making such infrastructures work.

McFarlane and Silver (Citation2017, p. 463), describe infrastructures as a verb, as they are ‘made and held stable through work and changing ways of connecting’. Accessibility, as a form of producing ways of navigating space that are inclusive for a wider part of the population, should thus be recognised as the result of continuous, transformative, work. This work, as we will see, is not only mobilised by practices of design and maintenance, but also by ordinary interactions between members of the public (the ‘users’). Accessibility, conceptualised as practice, takes distance from a delocalised, abstract understanding of accessibility as an inherent characteristic of individual objects, achievable regardless of the users’ capacities (Winance, Citation2014).

Following perspectives that recognise infrastructures as socio-materially produced, which challenge ‘an otherwise artificial divide between “the social” and “the technical”’ (Coutard & Rutherford, Citation2015, p. 8), I describe accessibility as made out of interrelations (Titchkosky, Citation2011). Rather than a design horizon, accessibility is better understood as a composition of practices, interactions and infrastructural implementation, requiring of constant work and attention to continue to hold together.

A practiced landscape of accessibility

Lawhon et al. (Citation2018, p. 721) critically discuss mainstream aspirations to universal infrastructure solutions, indicating that ‘there is a growing recognition of the limited possibilities for achieving universal, uniform networked access to services’. They respond by developing the notion of Heterogeneous Infrastructure Configurations (HICs), focusing their attention on capacities and the local emergence of infrastructural arrangements. My approach, inspired by HICs, recognises that the features of infrastructure (e.g., being accessible) are not contained in individual objects, but are rather the result of ongoing action that is distributed across many different entities.

However, while the agency of people in relation to the production, (de)stabilisation, and re-specification of infrastructures has commonly been addressed in terms of collective organisation and meaning-making practices (Lawhon et al., Citation2018; McFarlane & Silver, Citation2017), less has been said in terms of human agency as being enacted through ordinary practices. At this point, we may turn to Castán Broto (Citation2019, p. 6), who discusses landscapes as a way of turning our attention towards ‘day-to-day interaction and situated practices’ and criticises ‘one-size-fits-all’ approaches. In this sense, a landscape is an articulation of human doings and materialities—the result of diverse forms of inhabiting and spatially organising life. By relating to the landscape not as spectators but as participants (Ingold, Citation1993), dwellers give it shape through their activities. Thus, framing the issue of accessibility as a heterogeneous and ever-occurring landscape gives us more tools to understand the work that disabled people contribute with in configuring infrastructures as accessible.

The emergence of these ‘landscapes of accessibility’ takes place in the intense interactional work that is routinely done by members of the public, as well as through their interaction with various available materialities. These are precarious arrangements that require constant involvement and relational work for them to emerge and ‘hold together’ (McFarlane & Anderson, Citation2011). In that sense, we can observe the contrast between Transantiago’s landscapes of accessibility—enacted, in part, by the doings of disabled people themselves—and its universalistic aspirations to produce accessibility for disabled people—a one-size-fits-all arrangement that sees disabled users as recipients of expert infrastructural implementation.

Descriptions of ‘people as infrastructure’ (Simone, Citation2004), ‘people as affordances’ (Dokumaci, Citation2020), and ‘social infrastructures’ (McFarlane & Silver, Citation2017) lay the groundwork for the landscapes of accessibility enacted by disabled people. Research by Dokumaci (Citation2020, p. 98) describes the ‘acts of world building, with which disabled people literally “make up”, and at the same time “make up for”, whatever affordance fails to readily materialize in their environments’. However, while it is true that people often compensate for lacking materialities, I would also highlight that the agency of everyday practice is not only apparent in exceeding or compensating for lacking or absent material implementation. In what follows, I will explore how, even when centralised measures are widely deployed to deliver accessibility solutions, these infrastructures still need to be enacted by local practices and interactions. This calls for a revised notion of accessibility—conceptualised as the ongoing result of interactional work mobilised by the practices and affordances of heterogeneous entities that manage to configure everyday landscapes of accessibility every day.

Methodology

As this research conceives accessibility as a ‘doing’—the result of ongoing mundane practices and interactions between people and materialities—it takes distance from the idea that accessibility can be inscribed in infrastructures at the design stage. Design and implementation of ramps, lifts, or signage is not sufficient—infrastructures are to be enacted as accessible by the everyday methods that people use to navigate social life. Their usefulness and convenience for disabled people is not inscribed in the objects themselves. It is done in the actual encounters between user and infrastructure. This resonates with an ethnomethodological sensibility that conceives of forms of social order and rationality as being locally produced (Garfinkel, Citation1967). Ethnomethodology, which informs this study, encourages a shift in attention—from the agency of abstract concepts, to what is accomplished by situated encounters and local interaction. Ethnomethodology’s emphasis is on tracing the skilled practices that people engage in to routinely accomplish things, and on following their own methods to achieving social order.

Thus, this study attempts to account for the knowledge and skills of disabled people, who are systematically ‘othered’ (Garland-Thomson, Citation2011; Hughes, Citation2009) and even pathologised by institutions, policy, and non-disabled members of the public. An ethnographic approach gave me the tools to not only observe, but also participate in the practices that disabled people engage in when encountering Transantiago infrastructures.

The data I will present was collected during my PhD research on the practices of disabled and older people who use Santiago’s public transport system. My nine-month fieldwork consisted of two parts. First, I conducted ethnographic go-alongs (Kusenbach, Citation2003) with disabled people who were regular Transantiago users, several times with each participant when possible. In order to stay attentive to the highly detailed sequential aspects of ordinary interaction (Sacks, Citation1995), the participants wore a GoPro camera to record their doings as they used Transantiago with me. In the case of Natalia, whose case I present below, the camera was attached to the left armrest of her electric wheelchair, according to her own preferences.

As described by Heath et al. (Citation2010), video data lends itself perfectly for sequential analysis of social interaction. The properties of video—presented below as a ‘graphic transcript’ (Laurier, Citation2014)—allow the analysts to see a given action as occasioned by prior actions within an interactional sequence. That same action, in turn, will shape the emergence of subsequent actions, and so forth. In this study, accessing the sequential organisation of social interaction reveals the methods people use to achieve relevant things in social life, such as producing accessibility.

It is important to note that my ethnographic involvement raised several challenges in terms of my own positionality as a non-disabled person. My bodily privilege was foregrounded constantly as I travelled together with the participants, our embodied differences highlighted ‘as we attempt to live and move as others do’ (Lee & Ingold, Citation2006, p. 69). Among other things, the challenge of ‘moving along with’ resided in figuring out, together with the participants, when and how our embodied capacities should come together or stay apart. My presence transformed the participants travels in several ways. I was able to assist them at critical moments. Other times, the system separated our circulation paths. In this sense, the video recordings gathered are not a perfect reflection of the participants’ everyday travels, nor do they aspire to be. However, they allow us to observe, in detail, the sequential aspects of social interactions as they happened. My presence during these events is not something that I attempted to minimise. Rather, it was accounted for in the analysis.

Enacting devices as accessible

Case 1: doing priority

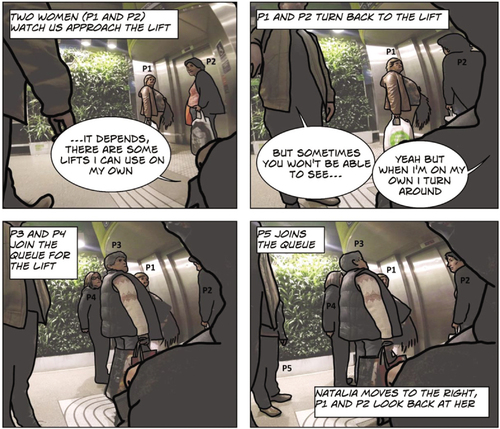

Natalia and I are a bit lost. We have been looking for the right lift down to our next platform for a while, and I am being of little help. When I commute, I do not commonly use lifts so I do not have a proper sense of how to navigate a Metro station through its elevator system. We now seem to be on the right track though. I follow Natalia as she confidently approaches a lift which should take us down to our platform. The lift is already being expected by two passengers (see ).

In this instance, Natalia and I approach the lift, while we chat about how difficult it is for Natalia to know whether she will be able to reach a lift’s buttons. There is a sign on its side, which reads ‘Priority’ and bears the International Symbol of Access (ISA). We take position by two female passengers carrying bags, P1 and P2, already waiting for the lift. Both of them turn and look at us (panel 1, top left) before turning their attention back to the lift’s doors (panel 2, top right). Natalia and I continue our conversation. Even though we have position ourselves near the lift, we have left a free spot immediately behind P1 and P2. This seems to be seen as an ambiguous relation to the queue in formation: P3 and P4 take the empty space, and look at us as if monitoring our reaction (panel 3, bottom left). P5 also approaches the group, and stands in a third row behind P3 and P4. The entire group looks at the monitor on top of the lift, keeping track of its approach. Natalia moves slightly to her right and closer to the lift. This seems to prompt a reaction from P1 and P2, who look back at her (panel 4, bottom right).

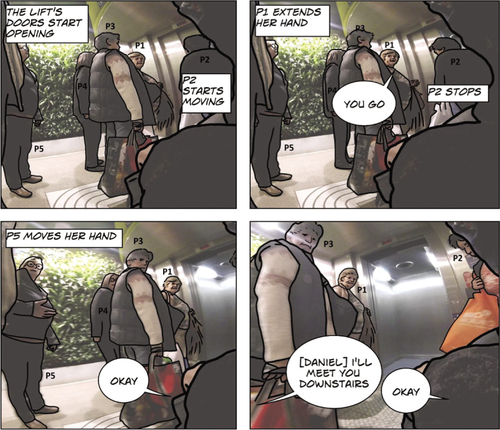

The story continues in . The lift’s doors start to open and P2 quickly moves forward, lifting her bags. P1, for her part, looks at Natalia more intently, as she prepares to formulate an offer (panel 5, top left). Panel 6 (top right) shows an interesting moment: P1 extends her hand and turns to Natalia, saying ‘adelante’ [you go]. This triggers a change in P2’s trajectory, who stops and quickly turns. Every member of the queue turns to Natalia. P2 steps away from the lift, opening a path for her to go first. P1’s offer is reinforced by her nodding, as well as by P5 moving her hand in an invitational manner. Natalia responds with a ‘ya’ [okay] and moves towards the lift (panel 7, bottom left). P3 stands sideways, causing the path produced by P2 to widen. As Natalia moves, I announce that I will meet her downstairs, in the train platform. She acknowledges this and carries on (panel 8, bottom right).

A number of things can be said from analysing this scene. It is apparent that the lift is treated as a device with limited availability. It requires turn taking, prompts queue formations, and being left out of the lift can be seen as costly because of how long it takes to complete a cycle. Hence the lift’s usage revolves around queue dynamics, although we see from this case that such ordering remains flexible and subject to adaptation depending on the circumstances. The ‘priority elevator’ sign on the side reinforces the sense that common rules of queuing are to be reconsidered if a ‘priority user’ comes along.Footnote1 This is, of course, not policed by the sign itself and it takes in fact quite a bit of work by the participants to reorganise the ordinary rules of the setting in order to produce an accessible arrangement for a priority user. The question then is, how is a priority user identified and dealt with?

Priority in this case is enacted through a rearrangement of everyday rules of queuing, which commonly establish that those first in the queue will go/be served before those coming after them. In analysing customer/seller interactions, Brown (Citation2004) has observed that, despite the importance of supporting artefacts to order queues, queues are primarily constituted by people queueing. In this sense, the sign stating reduced mobility people are ‘priority users’ does not do all the work necessary to give Natalia such priority to board the lift. Rather, it is the group of people constituting the queue who ends up reconfiguring it. Though P5 shows willingness to let Natalia go first in panel 7, P1 is the one with the highest ‘authority’ because of her being first in line. This can be seen in panel 6, when her hand gesture is capable of interrupting P2’s trajectory. This is, of course, not only P1’s doing. Natalia moves slightly to her right as the lift gets closer, orienting herself towards the lift and getting both P1’s and P2’s attention. Natalia’s shift seems to recruit P1’s cooperation, who sees the subtle movement as showing interest in taking part of the boarding process. The other users comply with P1’s invitation, either by reinforcing the offer with gestures or by repositioning themselves, forming a more comfortable path for Natalia to go in first.

Despite our ambiguous position in the queue (which is initially challenged by P3 and P4), Natalia shows herself to be next in line by moving to the right. This form of ‘working the queue’ (Brown, Citation2004, p. 1) on Natalia’s part is picked up by P1 and prompts an offer from her. This seems to indicate that an accessible situation is not just produced under the form of ‘help’ being given on its own, but rather as an interactional accomplishment in which Natalia’s expression of interest works as a way of ‘mobilising assistance’ (Middleton & Byles, Citation2019, p. 80) from key actors. Finally, P2’s case is also noteworthy. Even though priority as an imperative was already established by the sign, and Natalia’s signal had been noticed by her, P2 stills initiates her entrance as soon as the lift arrives, remaining within the frame given by common rules of queuing. P1’s actions have the effect of stopping P2 in her tracks, causing her to move to the side and comply with Natalia’s prioritisation.

This case shows an example of how a lift is made to function as an accessibility device through ordinary rules of priority. Priority for disabled users can be established as morally relevant by signage and other material features, but it ultimately needs to be enacted by the participants of the situation. Importantly, Natalia is not a passive receptor of assistance. Rather, she takes an active part in the sequence by expressing an interest in being prioritised by moving closer to the lift when it arrives.

Case 2: making up for lacking infrastructure

The situation at the lift gets me thinking about the issue of offering assistance. As I take the stairs down to the platform to meet Natalia there, something that had happened to me a few days ago comes to mind. I was in the 501 bus on my way to see a friend. That day there was a wheelchair user in the bus, and I discretely focused my attention on him. The bus arrived to its final stop by Parque Bustamante, but another bus was blocking the stopping space. The passengers in our bus were getting restless (most people take the metro from there and continue their journeys), so the driver opened the doors even though we were not in the bus stop yet, and we were a bit far from the kerb. The bus was emptied very quickly, except for the wheelchair user, a young man, and me. I observed the younger man offering his help to the wheelchair user, getting off the bus and unfolding its heavy and dusty accessibility ramp. The ramp turned out to be broken, pathetically hanging from just one of two hinges. I was sad to realise that this did not surprise me much. Transantiago buses and stops are usually in disrepair in one way or another. I approached the younger man with the intention to be of help, although I was not sure how. He smiled reassuringly and attempted to install the ramp anyway. The gap between bus and kerb was too great though, and the ramp rested against the road in a pronounced angle that was impossible to navigate. He then lifted the ramp again, yelling instructions at the bus driver for him to move the bus closer to the pavement. The driver reacted quickly and we were able to coordinate with him a more suitable angle. The wheelchair user waited patiently, even though he had been waiting several minutes to get off the bus. The second attempt went better; the ramp as correctly installed connecting the vehicle and the kerb. But its stability was still an issue, it was loose from the side missing a hinge. The young man decided to make up for this himself, standing on one of the ramp’s sides and physically holding it in place with his hands. I joined his effort from the opposite side. The wheelchair user approached the ramp and got off the bus slowly moving backwards, which gave him more control throughout the manoeuvre. The platform and our arms held his weight well enough, and the alighting process took less than ten seconds (Field notes, 10 May 2017).

This story is filled with injustices. From the longer time that a wheelchair user has to wait for something so seemingly simple as to get off the bus, to the infuriating neglect of crucial accessibility devices like the ramp. While we may feel tempted to say that this type of situations can be avoided with proper design of materialities and protocols, I would rather like to emphasise how active and relevant is the role of passengers—disabled passengers included—in ‘making stuff work’ so as to enact accessible solutions. As with Natalia’s encounter at the lift, the anonymous wheelchair user was involved in a form of adaptation aimed at producing a more accessible arrangement for him, in the face of neglected accessibility protocols and maintenance. In Natalia’s case, people adapted their conduct and general queueing norms in order to produce priority, whereas in the case of the anonymous wheelchair user the situation revolved around physical adaptation and ‘making up’ for a lacking material solution (Dokumaci, Citation2020; McFarlane & Silver, Citation2017). Both stories, however, show the importance of assistance being offered and properly organised. While the woman who was first in line for the lift used her position as leverage to rearrange the queue’s order, we coordinated our efforts with the bus driver to more conveniently install and hold the broken ramp.

The wheelchair user from the bus patiently waited for us and carefully adapted his way of using the ramp to our precarious impromptu solution. Natalia, for her part, gladly accepted an offer that was, partially, prompted by her own signals. The two of them played an active role in the adaptation work produced, be it by bringing their own bodily capacities into it, or by enlisting and managing help from others.

It is relevant to say that these interdependent practices of enacting devices as accessible are not intrinsically ‘good’. As the ramp story illustrates, they can apply a veneer of idealised solidarity over insufficient infrastructures. Transantiago users often encounter materialities whose design is lacking, or that have fallen into disrepair. Different forms of adaptable assistance can make up for these gaps and produce a passing accessible arrangement in particular cases, but also risk naturalising the negligent absence of other entities.

Both cases include assistance as a practice that enables accessible arrangements, either by enacting the features of a device, or compensating for its lack of maintenance. Mainstream understandings of accessibility treat independence as a mandate (Hamraie & Fritsch, Citation2019) and generally use it as a criterion for identifying a ‘fully accessible’ space. Recent geographical research focusing on the mobility experiences of disabled and older people, however, invite to a more nuanced, critical engagement with the notion of independence. Focusing on the case of mobility in the later life, Schwanen et al. (Citation2012) point out that independence is often promoted as a value by institutions associated to neoliberal or modernist forms of governance. They identify in these cases a notion of independence that is equated to isolation—that is, not needing of others in order to function in social life. Such a notion, however, struggles to realise ‘human embodiment and the fundamental enmeshment of individuals in relations with other humans, other forms of life, technical artefacts and other forms of inanimate matter’ (Schwanen et al., Citation2012, p. 1314), a notion that is present in the notion of HICs and that resonates with the heterogeneous practices that compose landscapes of accessibility. It is, then, urgent to transition from a notion of independence to one of interdependence, acknowledging it as an ever-present aspect of human life in general, and of the life of disabled people in particular (Hamraie & Fritsch, Citation2019).

The cases I have presented echo this notion. In them, accessibility is made to happen in heterogeneous collaborative manners, of which disabled people are not passive receptors. Rather, they actively engage with others who may be of assistance, prompt and organise offers of help, and draw on the affordances of available materialities in order to locally enact ad hoc infrastructural landscapes of accessibility.

Modernistic perspectives see independence as a value that is tightly tied to accessibility, in which a universally accessible space would be one that is useable by anybody, without needing help. These cases illustrate how different forms of assistance are crucial for accessibility to take place, even in the face of ‘well-designed’ solutions. While some forms of assistance are undesirable as they make up for lacking design or maintenance, others express capacities for social organisation that come together along with infrastructure and technologies as accessible arrangements. These cases express the need for thinking of infrastructural change towards accessibility as it being continuously enabled by practices of interdependence. Rather than deeming dependence as opposed to accessibility and outright attempting to avoid it, it is intriguing to think of landscapes of accessibility as assemblages enacted by material intervention and quotidian forms of interdependence.

Conclusion

In this paper, I have shown how the transformation of Transantiago into an accessible service is enabled by the local ordinary practices of people using this infrastructure. I have presented two different cases illustrating this—one in which people’s practices draw on available infrastructures and enact them as ‘accessible’, and another one in which people intervene to make up for neglected accessibility devices. Notice that, even when a device designed for accessibility (i.e., a lift) is at hand, enacting an accessible situation is still being done by the participants of a given interaction.

Drawing on the concept of HICs, I described accessibility arrangements ‘not just in terms of their presence or absence, but as dynamic, power-laden socio-material artefacts that are part of a web of relations’ (Lawhon et al., Citation2018, p. 729), which include the everyday practices of disabled and non-disabled people. Such forms of human involvement in the everyday production of accessibility resonate with contemporary perspectives inviting us to look beyond ‘whether people make infrastructure or infrastructure makes up people—and instead trace socio-material interactions in multiple directions’ (Angelo & Hentschel, Citation2015, p. 311). Within infrastructure studies, there is an agreement around the notion of ‘peopled infrastructures’ as made up of practices and social organisation. I have sought to highlight that there is still much to be learned about the ordinary forms of skilled interactional work that people devote to maintaining or transforming such relationships in everyday life.

By tracing how passengers of Transantiago interact with one another and with surrounding materialities, I have sought to outline a practiced form of accessibility that is not contained in specific features of design, but is rather enacted in the everyday and local production of heterogeneous landscapes of accessibility. In exploring the detailed and complex forms of interactional work that come together in the everyday production of accessible arrangements, nuanced forms of trouble are revealed. From the minute gestures done to produce priority at a lift queue, to the complex embodied struggles of physically making up for broken ramps, the cases I have presented show ‘access-making as a site of political friction and contestation’ (Hamraie & Fritsch, Citation2019, p. 10). Such perspective frames accessibility as the ongoing outcome of practices that are not easy to unfold, and that always require effort to take place. It is, therefore, relevant to continue studying how people achieve these arrangements, and what is at stake for them in doing so.

Among the things revealed by analysing these access-making practices, we can observe the importance of interaction, co-operation, and assistance in ordinary encounters between disabled and non-disabled people. The cases reviewed resonate with Dokumaci’s (Dokumaci, Citation2020, p. 100) assertion that ‘people can enable the emergence of, or directly become, affordances for one another, especially when the affordances that their coming-together might create do not and could not otherwise exist within the niche they share’. In this sense, the ‘mandate’ for independence that guides mainstream discourses related to disability and accessibility needs to be carefully scrutinised. Even in instances of assistance-giving, disabled people play an active role in the enrolling of others and in the local design of alternatives (Muñoz, Citationin press). Rather than being subjected to a binary of dependence/independence, disabled people take part in complex relations of interdependence with others. To study the everyday constitution of these practices is highly relevant, as our ‘accessible futures require our interdependence’ (Hamraie & Fritsch, Citation2019, p. 22).

It is worth noting that while I have shown the importance of ordinary practices of assistance, I am not arguing that the role of design and planning are any less relevant. On the contrary, we ought to be wary of condoning the common practice of ‘adding access as an afterthought’ (Alphin, Citation2014; Lewthwaite, Citation2011). Rather than advocating for a loose and less rigorous approach to implementing accessible solutions for the public, I contend that a serious and realistic strategy requires acknowledging that such a process is not ever ‘complete’, nor it resides solely within materialities. If anything, this calls for an even deeper involvement on the part of technical experts and institutions. Seen as a relational achievement, accessibility requires constant engagement not only in the design and testing of material implementations, but also regarding their maintenance, updating, and improvement. Thus, the call is not only to reassess the real effectiveness of the so called ‘infrastructures of accessibility’ in public transport systems, but also to reassert the importance of participatory forms of design and maintenance that keep disabled people involved in a process of continuous infrastructural assessment. As new implementations are designed and tested, disabled people who have so far been unable to navigate urban spaces may find the infrastructural means to do so. This, in turn, will foreground new ways in which accessibility is locally enacted by disabled people. From this perspective, rather than focusing on the provision of accessible spaces as a one-way task, accessibility designers might find value in interrogating their own place within the landscape of practices and materialities that enact accessibility.

Understanding accessibility as a practice reveals the highly skilled and often unrecognised ways in which ordinary people do not only draw on available materialities, but in fact routinely make up for them. Furthermore, understanding accessibility as a landscape of practices and materialities foregrounds the fact that accessible infrastructures can never be ‘complete’. Landscapes of accessibility are permanently being brought into being (Ingold, Citation1993), and thus require of more and more interdependent forms of pursuing that task.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the editors of this special issue, Vanesa Castán Broto and Enora Robin, for their thoughtful comments on an earlier version of this paper. I am also grateful to Dan Swanton and Eric Laurier, whose guidance was crucial to the development of my argument. Finally, I am thankful to Natalia and to all of the people who participated in my research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Daniel Muñoz

Daniel Muñoz completed his PhD in Human Geography at the University of Edinburgh. His research focuses on the embodied dimension of mobility practices in everyday life, particularly in the case of Latin American public transport systems. He works ethnographically, does video analysis, and is interested in ethnomethodology and conversation analysis.

Notes

1. Even though disabilities can be non-visible, their representation with the universal icon of a wheelchair (see Ben-Moshe & Powell, Citation2007 for a more detailed account of the International Symbol of Access) might be working to Natalia’s advantage in this case.

References

- Alphi, H. C. (2014). Accessibility implementation for disabled students in PMBOLD environments. In Resources Management Association (Ed.), Assistive technologies: Concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications (pp. 1173–1195). Information Science Reference. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-4422-9

- Angelo, H., & Hentschel, C. (2015). Interactions with infrastructure as windows into social worlds: A method for critical urban studies: Introduction. City, 19(2–3), 306–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1015275

- Barnes, C. (1991). Disabled people in Britain and discrimination: A case for anti-discrimination legislation. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers.

- Ben-Moshe, L., & Powell, J. J. (2007). Sign of our times? Revis(it)ing the international symbol of access. Disability & Society, 22(5), 489–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590701427602

- Brown, B. (2004). The order of service: The practical management of customer interaction. Sociological Research Online, 9(4), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.973

- Castán Broto, V. (2019). Urban Energy Landscapes. University Printing House.

- Coutard, O., & Rutherford, J. (2015). Beyond the networked city: Infrastructure reconfigurations and urban change in the North and South. Routledge.

- Dokumaci, A. (2020). People as affordances: Building disability worlds through care intimacy. Current Anthropology, 61(S21), S97–S108. https://doi.org/10.1086/705783

- Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in ethnomethodology. Prentice-Hall.

- Garland-Thomson, R. (2011). Misfits: A feminist materialist disability concept. Hypatia, 26(3), 591–609. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2011.01206.x

- Graham, S., & McFarlane, C. (2014). Infrastructural lives: Urban infrastructure in context. Routledge.

- Hamraie, A., & Fritsch, K. (2019). Crip technoscience manifesto. Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience, 5(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.28968/cftt.v5i1.29607

- Hartblay, C. (2017). Good ramps, bad ramps: Centralized design standards and disability access in urban Russian infrastructure. American Ethnologist, 44(1), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12422

- Heath, C., Hindmarsh, J., & Luff, P. (2010). Video in qualitative research. Sage.

- Hughes, B. (2009). Wounded/monstruous/abject: A critique of the disabled body in the sociological imaginary. Disability & Society, 24(4), 399–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590902876144

- Ingold, T. (1993). The temporality of the landscape. World Archaeology, 25(2), 152–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.1993.9980235

- Jirón, P., Imilan, W., & Iturra, L. (2016). Relearning to travel in Santiago: The importance of mobile place-making and travelling know-how. Cultural Geographies, 23(4), 599–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474015622141

- Kusenbach, M. (2003). Street phenomenology: The go-along as ethnographic research tool. Ethnography, 4(3), 455–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/146613810343007

- Laurier, E. (2014). The graphic transcript: Poaching comic book grammar for inscribing the visual, spatial and temporal aspects of action. Geography Compass, 8(4), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12123

- Lawhon, M., Nilsson, D., Silver, J., Ernston, H., & Lwasa, S. (2018). Thinking through heterogeneous infrastructure configurations. Urban Studies, 55(4), 720–732. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017720149

- Lee, J., & Ingold, T. (2006). Fieldwork on foot: Perceiving, routing, socializing. In S. Coleman & P. Collins (Eds.), Locating the field: Space, place and context in anthropology (pp. 67–86). Berg.

- Lewthwaite, S. (2011). Critical approaches to accessibility for technology‐enhanced learning. Learning, Media and Technology, 36(1), 85–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2010.529915

- Massey, D. (2005). For space. SAGE.

- McFarlane, C., & Anderson, B. (2011). Thinking with assemblage. Area, 43(2), 162–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2011.01012.x

- McFarlane, C., & Silver, J. (2017). Navigating the city: Dialectics of everyday urbanism. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 42(3), 458–471. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12175

- Middleton, J., & Byles, H. (2019). Interdependent temporalities and the everyday mobilities of visually impaired young people. Geoforum, 102, 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.03.018

- Mol, A. (2002). The body multiple: Ontology in medical practice. Duke University Press.

- Muñoz, D. (in press). Carrying the rollator together: A passenger with reduced mobility being assisted in public transport. Gesprächsforschung.

- Nilsson, D. (2016). The unseeing state: How ideals of modernity have undermined innovation in Africa’s urban water systems. NTM Zeitschrift für Geschichte der Wissenschaften, Technik und Medizin, 24(4), 481–510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00048-017-0160-0

- Oliver, M. (1990). The politics of disablement. Macmillan International Higher Education.

- Sacks, H. (1995). Lectures in Conversation. Blackwell.

- Schwanen, T., Banister, D., & Bowling, A. (2012). Independence and mobility in later life. Geoforum, 43(6), 1313–1322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.04.001

- Silver, J. (2016). Disrupted infrastructures: An urban political ecology of interrupted electricity in Accra. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(5), 984–1003. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12317

- Simone, A. M. (2004). People as infrastructure: Intersecting fragments in Johannesburg. Public Culture, 16(3), 407–429. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-16-3-407

- Titchkosky, T. (2011). The question of access: Disability, space, meaning. University of Toronto Press.

- Ureta, S. (2015). Assembling policy: Transantiago, human devices, and the dream of a world-class society.. The MIT Press.

- Velho, R., & Ureta, S. (2019). Frail modernities: Latin American infrastructures between repair and ruination. Tapuya: Latin American Science, Technology and Society, 2(1), 428–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/25729861.2019.1678920

- Winance, M. (2014). Universal design and the challenge of diversity: Reflections on the principles of UD, based on empirical research of people’s mobility. Disability and Rehabilitation, 36(16), 1334–1343. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.936564