Abstract

This article examines the under-researched relationship between the auditory and visual sequences of spatial experience at Rousham garden, a highly regarded Picturesque landscape. It examines historic sources and broader literature against contemporary data collected on-site, arguing that conventional readings of the Picturesque underplay the multisensory nature of spatial experience of these landscapes. It then argues that this relationship could be productively analysed and represented by vertical montage as defined by Russian film director Sergei Eisenstein (1898–1948), and in re-evaluating this auditory and visual experience, provides a new understanding of the Picturesque that moves beyond the conventional notions of the pleasures of seeing. Finally, in examining how this experience is related to time, movement, tempo and sound, it creates a new method for reading and representing design features from the senses of sound and vision.

Introduction

Rousham garden in Oxfordshire, designed by William Kent (1685–1748) between 1737 and 1741, is a pivotal example of the English Picturesque, described by architectural critic Christopher Hussey as ‘the earliest means for perceiving visual qualities in nature’ (Hussey, Citation1967, p. 17). Kent’s design built upon Charles Bridgeman’s (1690–1738) 1720’s innovative proposals amending the classical tradition through naturalistic features such as areas of wilderness with ponds to the north-west of the house. Appointed after Bridgeman, Kent developed a more radical approach, adding a series of follies along an experiential path; which as the English architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner noted is a ‘key work in the change from symmetry to picturesque irregularities in garden design’ (Sherwood & Pevsner, Citation1974, p. 402). Far beyond Rousham garden itself, the concept of the Picturesque has been widely investigated and developed during the last two centuries across divergent fields. From French architectural historian Auguste Choisy’s interpretation of Greek architecture, to British historian Colin Rowe’s reflection about compositive methodsFootnote1, the Picturesque seems to be a never-ending source of ideas for modern architectural and landscape theory. Yet despite this enormous breadth of studies, it is of particular relevance to this paper to highlight that the Picturesque continues to be related to visual aspects of design.

This paper concentrates on the multisensorial experience of Rousham garden, focussing in particular on the relationships between views, movement, and finally tempo and sound. Our aim is to explore the spatial and temporal aspects of the auditory and visual senses in experiencing landscape, and to underline how the Picturesque, and in particular Rousham garden, can offer insights into how to design combining more than one sense together. From a methodological point of view, the article examines Rousham garden linking different disciplines together, such as landscape architecture, aesthetics, design history and film theory. The goal is to suggest an interdisciplinary approach to investigate historic case studies, and to propose in particular an innovative use of montage as a methodology to analyse the sensorial qualities of landscape. The investigation, more specifically, has been developed by collecting data on-site (i.e. photos, videos, audio recordings) and analysing them in relation to current plans and sections of the garden. Finally, these data have been studied through a modified version of Sergei Eisenstein’s vertical montage, used as a method to compare visual and audio outputs against time. Within concepts of cinematic montage, as Aumont notes, ‘critics and biographers are all agreed on this one point: Eisenstein equals montage’ (Aumont, Citation1987, p. 145), and the extent and breadth of his writings, from 1923 to 1948, provides a comprehensive basis for this research.

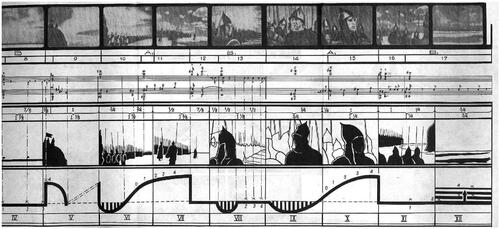

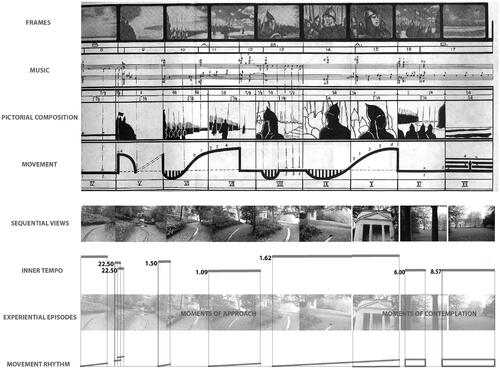

Although Eisenstein proposed other types of montageFootnote2, this research focuses on vertical montage ().

Writing on the synchronisation of senses, he noted ‘a new “super-structure” is erected vertically over the horizontal’ (Eisenstein, Citation1943, p. 68), finally proposing vertical montage to demonstrate the simultaneous impact of sound-picture relationships. Our analysis will show how Kent’s design is based on a series of sequences, which, while showing great richness in architectural, artistic and natural features arranged to define the users’ experience, also clearly reveals a methodical design iteration orchestrating these elements according to a recurring rhythm that flows across vision and sound. In this sense, Rousham garden supports the thesis that the Picturesque is a method of composition that may potentially support multisensorial design, linking auditory aspects of time and tempo, with notions of visual movement and sequences.

Despite recent efforts, the dominance of visuality in Western culture (Levin, Citation1993) seems still to overcome the positive intentions of contemporary designers to focus on multisensorial ways of perception of spaceFootnote3. As Juhani Pallasmaa noted: ‘the inhumanity of contemporary architecture and cities can be understood as the consequence of the negligence of the body and the senses, and an imbalance in our sensory system’ (Pallasmaa, Citation2012, pp. 17–19). In this sense, the critical discourse that developed through the twentieth century on the Picturesque, should be considered as part of this ‘ocularcentric’ tradition. The possible reinterpretation of the Picturesque as a method of composition that supports multi-sensory design, can further feed theories on the dilemma between visual and bodily properties of space (Stiërli, Citation2016), whilst also providing a historical point of view.

The Picturesque as design method, beyond visual properties

Since its first appearances early in the seventeenth century, numerous scholars have tried to define and describe the concept of the Picturesque. The meanings seem to acquire dissimilar nuances according to the different disciplines to which they are related but also, and especially, they seem to change over time. In the beginning, ‘picturesque’ was used to describe a landscape (natural or urbanized) with pictorial qualities (Price, Citation1810). As the Oxford English Dictionary states, the term ‘picturesque’ can be an adjective, a noun, and even a verb (to make something ‘picturesque’). However, its most common use is as an adjective, with the meaning of ‘having the elements or qualities of a picture; suitable for a picture; spec. (of a view, landscape, etc.) pleasing or striking in appearance; scenic’.Footnote4

In this sense, it is easy to identify the origin of the term in relation to an artistic trend of the seventeenth century retraceable in the landscape paintings of Claude Lorrain or Nicolas Poussin, amongst others. These art works show a specific interest in constructing scenographies. The landscape here is not a simple background, it is the main subject and is articulated in rich scenarios, full of different elements and elemental details. The final painted image is carefully structured and composed, proposing a series of small scenes, each with narratives expressed through spatialities and potential temporalities, distributed inside a perfectly arranged frame. In a similar way, the English gardens of the late seventeenth century were developed by arranging a series of objects trouvés, various episodes, along a path; just as the pictorial unity had been fragmented in the landscape paintings, these new gardens were also composed by creating different small units, although now leaping beyond the frame and situated within a spatial, and not a pictorial, design. As Stiërli noted:

According to von Buttlar, the picturesque garden is accessed cinematically, in a sequence of images established by the observer’s movement. This is underlined by William Burgh, one of the leading theoreticians of the picturesque from the end of the eighteenth century. In his commentary on William Mason’s poem The English Garden in the 1783 edition, Burgh named two essential characteristics of the landscape garden designed according to the principle of the picturesque: namely, “variety” and “path”. (Stiërli, Citation2013, p. 171).

The great invention here is underlined by the ‘observer’s movement’ that defined new possibilities of composition. If indeed, the precedent Italian or French gardens were based on using geometries and perspectives that gave the observer the opportunity to see everything from just one point; now the observer needs to move. The ‘variety’ of different episodes, or scenes, is composed along a clear ‘path’ that represents the unit of the intervention, finally experienced as having pictorially different spatialities and temporalities.

Furthermore, the translation of these pictorial qualities into the physical landscape, opened the design possibilities to the third and fourth dimension. In this sense, the picturesque gardens are based on a bodily development of space that, as stated by Bruno, can be related to phenomenological principles (Bruno, Citation2002, p. 240).

The Picturesque experience of space

Following the idea that the Picturesque is an aesthetic category that we can use to describe art, architectural and landscape works, it is then clearly arguable that authors/designers can decide to develop their oeuvres in a Picturesque way. We will therefore approach the Picturesque as a method, and not just an attribute used to describe images or scenes. The Picturesque, in its landscape transposition in particular, refers to a system of composition based on the assembly of a series of elements comparable to cinematic sequences; the articulation of movement in space coincides with the structuring of a sequential path to be traversed physically and mentally. We can therefore consider movement in sequence along a path as a cornerstone of the design of the Picturesque system in landscape architecture, a method that allows a process of mental elaboration, and an interpretation based on the possibility of reassembling the individual scenes while keeping the idea of unity intact.

Yet, we note that the Picturesque method, even when applied to the three dimensions of physical space, always seems to refer to an essentially visual approach, to structured compositions of images, or views, more than spaces. The predominant role of the visual is expressed implicitly by writers who discuss the topic; the Picturesque route is intended as a sequence of views, and the interpretation of the associated space is purely visual. As Bruno noted:

Here, the garden was a form of museum. Composed of a series of pictures, often joined by way of association, the picturesque was constructed scenographically. Perspectival tricks were used to enhance the composition of the landscape and its mode of reception. (Bruno, Citation2002, p. 193).

This aspect of the Picturesque depends strongly on its original nature as a pictorial scheme, linked to the world of the surface of the canvas, and although transposed into three-dimensional reality, evidently anchored to the idea of framing space, rather than modelling it. However, perspectival effects can also be achieved with sound, drawing upon the strong human sense of distance derived from a sound’s volume. Indeed, we believe that an interpretation of the picturesque method, strictly related to its visual potentialities, does not properly consider the key role of movement, and leaves undiscussed the more complex multisensorial experience related to the visitor’s investigation of Picturesque spaces. As underlined by Yve-Alain Bois in his article A Picturesque Stroll around Clara-Clara:

the picturesque park is not the transcription on the land of a compositional pattern previously fixed in the mind, that its effects cannot be determined a priori, that it presupposes a stroller, someone who trusts more in the real movement of his legs than in the fictive movement of his gaze. (Bois & Shepley, Citation1984, p. 36).

Following Bois, we believe that movement, as an inherent element of the picturesque, could and should be considered as a tool for having a phenomenological experience of the landscape, where all five senses participate in defining the final, whole perception of the garden.

Representing the Picturesque: Eisenstein and vertical montage

In his fascinating introduction to the famous article by Sergei Eisenstein “Montage and Architecture”, Yve-Alain Bois retraces an unexpected line running between Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Choisy, Eisenstein, and finally Le Corbusier. Bois suggests that Piranesi ‘undermines the baroque domination of the a priori, gestaltist ground plan in our apprehension of architecture, depriving the spectator of any centre of reference, […], and initiates the rupture of the modern movement in architecture’ (Eisenstein, Bois, & Glenny, Citation1989, p. 113).

Saying that, Bois explains how this concept of ‘new space’ developed from Piranesi to Le Corbusier, passing by the Picturesque. In particular, he identifies in Choisy’s discovery of the Greek picturesque, an important ‘juncture’ of this path. For our purposes, it is interesting to note in particular the specific methods used to represent the concept of Picturesque over time (Bruno, Citation2002). Choisy, in his famous analysis of the Acropolis used a series of perspective drawings, referenced to a series of plans, clearly explaining in sequence the cinematic movement along the space from the observer’s point of view. In this way Choisy illustrated how the Acropolis had been designed following an idea of movement, noting that ‘the apparent asymmetry of this new Acropolis is only a means of lending picturesqueness to this group of buildings, which have been laid out with more art than any others’ (Eisenstein et al., Citation1989, p. 118).

Indeed, axonometrics are key drawings in considering the analysis and design of Picturesque projects and spaces.Footnote5 However, noteworthy in relation to the Picturesque, is the attempt to transmit the notion of movement through the relationship between images. If the Picturesque paintings were simply conveying the cinematic experience by fragmenting one image into several scenes, the representation of picturesque spaces looked for the possibility to further describe the concept of movement by literally exploding the image into different pieces (Vidler, Citation1993). So Choisy’s series of axonometrics of the Acropolis represents the experience of space showing in sequence the different scenes. As described by Giuliana Bruno (Citation2002), several techniques have been developed since the seventeenth century in order to show picturesque landscapes based on the notion of narrating the cinematic property of space through sequences: ‘Here, a series of views is displayed for spectatorial perusal: ordered into sequence, the multiple view acquires narrative potential and becomes a narrative space. The movement of sequentialization creates a fiction, and thus space, viewed as a progression, is narrativized’ (Bruno, Citation2002, p. 108). Furthermore, it might be important to underline how Choisy’s axonometrics are made from the human perspective. In this sense, the endeavour of highlighting the bodily experience of the space is evident, through a sequence of views: an attempt that was effectively replicated by Gordon Cullen several decades later, using the ‘serial vision’ as a method to represent the complexity of the urban experience (1961)Footnote6.

Choisy’s description of the Acropolis, entirely quoted in Eisenstein’s article “Montage and Architecture”, clearly shows the Russian director’s strong interest in Choisy’s interpretation of the Greek picturesque. Eisenstein, analysing words and drawings from the Histoire de l’Architecture, describes the Acropolis as a ‘perfect example of one of the most ancient films […] it is hard to imagine a montage sequence for an architectural ensemble more subtly composed, shot by shot, than the one that our legs create by walking among the buildings of the Acropolis’ (Eisenstein et al., Citation1989, p. 117). While these words, and this article, underline the close relationship between the cinematic experience of picturesque spaces and films (Bruno, Citation2002; Stiërli, Citation2013), the diagrams that Eisenstein developed during years of research about montage also define a relationship between methods of representation for picturesque spaces and films. In Eisenstein’s vertical montage, it is interesting to note how the visuality of films is represented simply by a series of images in sequence, just as Choisy’s axonometries of the Acropolis.

In adapting this method of representation, we follow a long list of design studies: as stated by Molinari (Citation2021, p. 894), ‘Eisenstein’s theories have attracted the attention of several architects and scholars, from Le Corbusier to Bernard Tschumi, and from Manfredo Tafuri to Anthony Vidler’. Vertical montage, more specifically, has been used throughout the twentieth century as a key method to rethinking the dilemma of representing the fourth dimension on printed paper. Tschumi’s ‘Screenplays’ and ‘Manhattan Transcripts’ (1976–1978) are famous examples, but the enormous spread and relevance of Eisenstein’s ideas on the discourse on representation in design disciplines are still evident in more recent studies by Szanto (Citation2010) and Lai (Citation2011).

Cinematic sequences of pictures and sounds

At this point, however, it is crucial to reconsider the Picturesque from the broader perspective that we introduced before. If the Picturesque is based on the movement and experience of a person enjoying space, how can we not consider other senses beyond vision, and not just sight, as part of the whole design process? In fact, Eisenstein’s interest in montage as a method to construct a series of views, is based on the main aim of capturing the viewer. From his first paper, the “Montage of attractions” from 1923, to his latter theories about pathos, Eisenstein’s main goal was always to provide an experience of shock, combining all possible tools and features related to cinema. Furthermore, the potential for montage to relate to fields beyond the cinematic was acknowledged by Eisenstein, who in relation to its possibilities for other temporal arts, noted ‘montage as a principle is not limited to cinema: it is found in literature, in theatre, in music, in painting, even in architecture’ (Eisenstein, Citation2010, p. xv). In the case of the English Picturesque, cinematic montage offers a means to overcome the historic challenges of perspective for landscape: the absence of time, the insistence on a static viewpoint, the distortion created by a monocular viewpoint, and the omission of sound. In asserting the superiority of this new representational medium over earlier drawn representations, Eisenstein notes:

The shape and size of things are no longer created by means of perspective […] it is differences of intensity, the relative richness of the colouring which create the shapes and sizes. In music, shape or bulk are no longer produced by receding planes but by a foreground of sounds which recede. Shape is created by the totality of sounds. (Eisenstein, Citation2010, pp. 342–343).

Arguing for a fundamental break with the idealised eye of conventional perspective, he noted ‘we no longer create perspective from an acute angle, of which the two lines meet at the horizon […] we pull the picture towards us, at us, into ourselves […] We are co-participants in it’ (Eisenstein, Citation2010, p. 342). Eisenstein saw this multisensory aspect as a critical component of his vertical montage, noting that ‘combining sound and pictures complicates montage by the need to solve a quite new compositional problem. […] congruence of a kind that will allow us to combine “vertically”, i.e. simultaneously, the progression of each phrase of music in parallel with the progression of the graphic units of depiction, the shots’ (Eisenstein, Citation2010, p. 370). This has also been recognised by others, including Lai, who noted that ‘the sequence of shots as a temporal organisation with rhythm is in fact analogical to the rhythm in spatial organisation of a path. This further reminds us of the musical nature in space’ (Lai, Citation2011, p. 388). And as Warshaw noted:

the concept of vertical montage can be understood on two levels. The first […] is a restating of the total-artwork ideal for the cinema: the overall ethic of ensuring that all elements of a film are 'vertically' related and aligned. On a more granular basis, the term can also refer to the interrelation of elements within any single shot (for instance, between the background and foreground elements, the visual frame as a whole and its musical sound track, or the beginning and the end of the shot). (Warshaw, Citation2018, p. 57)

This seems to be pertinent to the continuously unfolding nature of the walking experience of Rousham, where new views and sequences are linked into an extended spatial journey. The path is temporal and auditory, as well as visual.

Rousham garden by William Kent: a vertical montage analysis

Kent is widely regarded as a critical figure in the development of the Picturesque, spatialising in the design of Rousham garden particularly, the aesthetic value of visual apprehension that the English philosopher John Locke (1632–1704) had argued for in his 1690 treatise An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Locke proposed both a sensory delight and a sensory hierarchy with vision at its apex, building upon ‘the notion of “five senses” usually attributed to Aristotle’ (Stewart, Citation2005, p. 61) and his sensory hierarchy of vision-hearing-smell-taste-touch.

The different features comprising Rousham garden: the statues, little pavilions, ponds and seats, draw the user through a series of visual scenes were influenced by Kent’s knowledge of theatrical scenarios and his studies on Italian perspective. As Moggridge noted, ‘these individual compositions are disposed irregularly in relation to each other. They are linked by serpentine walks which burst suddenly from the secrecy of the woodland blocks to reveal the carefully composed scenes in a succession of surprises’ (Moggridge, Citation1986, p. 188). Although the garden is only six hectares in area, the sequential unfolding of the visual experiences is emphasised by the elongated site boundariesFootnote7, and the experience of ‘over 1000 variations on the circuits of the garden from the house, none passing along the same walk twice’ (Moggridge, Citation1986, p. 191). Kent’s design created spaces that are not simply series of framed views, but linked through their relationship and the experience of the journey between them. Indeed, what is the spatial relationship between these sequences of views? How has the discovery and the exploration of the landscape been developed? How was the experience designed in relation to time, movement and rhythm, and is sound a sense that has been taken into consideration during the design process?

An autumn afternoon, analysed

In order to properly answer these questions, we collected a series of visual and audio data about Rousham garden, analysed independently, then compared through Eisenstein’s vertical montage. The garden’s analysis was carried out on an autumn afternoon.Footnote8 The data collection was conducted through a continuous audio recording, and simultaneously through the shooting of a series of photographic images (one photograph every 10 steps). Subsequently, a video recording was made. The three different types of data—audio, still photos and continuous videos—were collected following the same specific path. Considering the plurality of routes mentioned earlier, we followed that described by John Clary (Batey, Citation1983, pp. 127–132), Rousham’s head gardener in Kent’s time, allowing us to locate—literally and figuratively—our studies within the time and space of the eighteenth century designed experience.

The recording of images and sounds is necessarily linked with, and possibly influenced by, the specific temporal parameters of this particular afternoon, by traffic on the adjacent roads, by other visitors, and even by aircraft on their approach to Oxford. However, in order to obtain more generalisable results, applicable to the garden experience at any time of the year and day, some visual and sound elements (such as the sound of footsteps on freshly fallen leaves) were not considered in the final processing of the data from this study. In this regard, we would like to underline how future research, linked to the garden’s seasonal and temporal variety, could contribute to the analysis and understanding of the Picturesque as a compositive method based on the subjective perception of space and time.

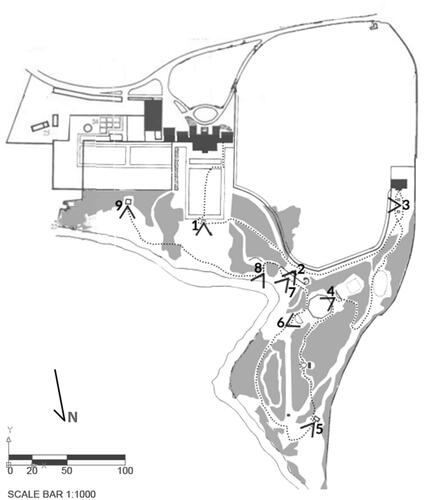

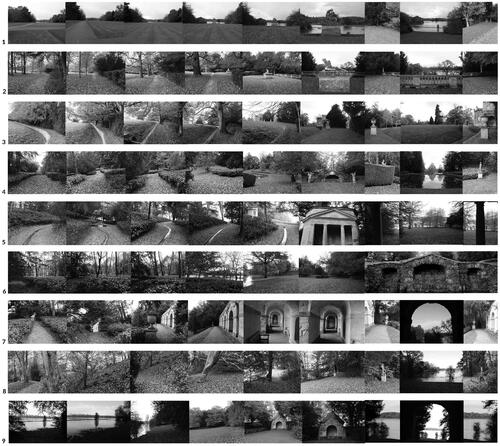

The series of views: landscape scenarios

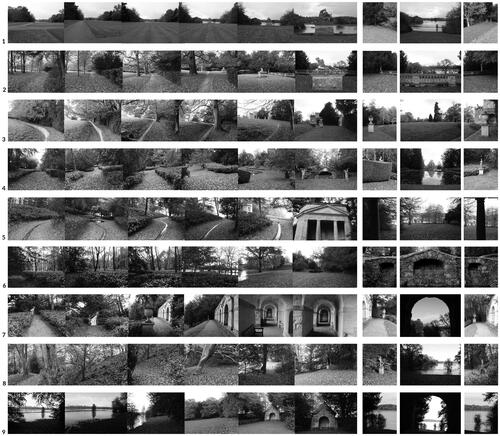

Analysis of the photographic images revealed the clear recognition of a series of views: perfectly framed scenarios arranged along the path. In particular, as shown in , we note that following Clary’s route, nine distinct views have been identifiedFootnote9, each one associated with a specific point in the garden. In these photos, we illustrate how Kent used statues, vegetation, water and other design elements, to compose and frame perfect views. In this sense, the visual analysis of Rousham garden supports the main literature about it: as Moggridge suggested, the compositional variety experienced by the visitor is based on a series of carefully framed scenarios, each one autonomous from the others. Analysing these nine images, indeed, in relation to the plan of the garden it is evident that there is no specific order, or sequence, nor can one define a singular route to follow (). Rather there is a complicated, perhaps even a confusing, meandering path.

The experiential episodes and the movement rhythm

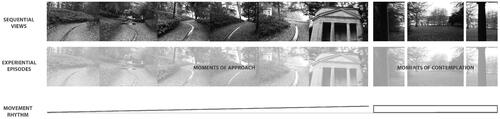

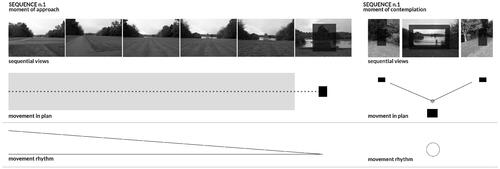

Our analysis of the visual data supports two statements. One is that Kent’s garden is, indeed, subdivided into autonomous views as already highlighted by other scholars. Secondly, and in this case originally and supported by our analysis, is that there is a compositional similarity—a design pattern—characterising the experiential sequences that led to these views. In fact, it is interesting to note that all the nine views identified can be related to longer sequential views (), where there seems to be a recurring subdivision of the rhythm and related design elements of the landscape. Drawing upon Eisenstein’s montage methods, where framed scenes, musical phrases, pictorial composition and movement were related over time (), we have further investigated our collected data.

If we arrange the series of photographs in a vertical montage diagram, and we analyse them in relation to time or movement rhythm (), we can highlight how the first three-quarters of the total time dedicated to each sequence is always based on the idea of a linear and regular path, defined by a consistent space and movement ().

Therefore, we follow undulating paths immersed in the forest (sequences n.4, n.8, n.10), lines drawn on the ground that invite us to movement (sequences n.3, n.5), tree-lined avenues (sequences n.2), or finally, open spaces with inviting vanishing points (sequences n.1, n.6, n.7, n.9). These experiential episodes, which we define as moments of approach, are clearly conceived with the idea of gently accompanying the visitors in their discovery of the garden, driving them to specific points of wonder and discovery. Thus, the last quarter of the sequences, is punctually based on the splendid and predefined views of the landscape, that are clearly framed by an architectural composition, usually a triptych, to which a seat is sometimes added. Moreover, in most cases, this view is linked to a water element. The experiential episodes related to these final views, which we call moments of contemplation are designed to amaze the viewer, offering statues, water features, architectural elements, and finally magnificent panoramas.

For example, in the first sequence, as we leave the service door of the house, we are clearly attracted by the central statue, and we cross the long, large lawn as we approach, until we reach the moment of contemplation, defined by the statue, the side seats, and finally the sublime view of the watercourse and the hill opposite. Subsequently, the second sequence presents itself as a tree-lined avenue, clearly indicating the path to follow, until reaching a second statue, again a central point, again framed by elements at the sides, and finally encouraging the view of the water basin below with the presence of a stone terrace. The picturesque experience of Rousham garden reveals itself beyond the rhythmically orchestrated views, showing a design of the tempo of users’ experience defined between moments of approach and moments of contemplation (). A last important observation on these two types of moments, approach and contemplation, is that in the former the tempo of experience and the movement rhythm is fast, and the spaces wide and long; while in the latter the tempo is slow, the movement rhythm almost nil, and the spaces more condensed. Vice versa, in the moments of approach the eye movement is minimal, because the sequential views are all based on the same unifocal vanishing points, which define the path itself, while in the moments of contemplation the visitor's eye is pushed to move to the discovery and contemplation of the panorama.

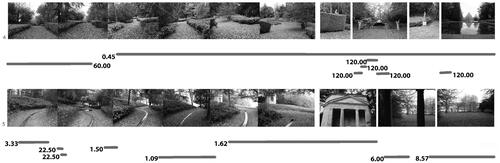

Sounds and images: vertical time

Conventional readings of Rousham’s history underplay the auditory components of Kent’s design. However, we know from historic records that he was aware of the nearby tourist attraction known as the Woodstock Echo (Buck, Citation2015, p. 132). Notably, from Kent’s design of the garden’s Temple of Echo, a small pavilion was created to amplify the sounds of the river, wildlife, and travellers on the nearby road to garden perambulations. While the ‘musical’ sounds of Eisenstein’s montage notation include conventional notated parameters of Western art music (pitch, volume, timbre, and rhythm), these landscape sounds were instead investigated for their temporal qualities and for their specific type of duration. This focus on sounds’ temporal qualities allows us to better understand the spatio-temporal relationships within these audio-visual experiences of our Rousham journey. Drawing upon earlier studies on methods of temporal analysis of landscape sounds (Buck, Citation2015, p. 116) this study uses the notion of ‘inner tempo’, which allows for a comparative measure of rhythmic movement in the absence of a metronomic beat. This is obtained by multiplying the number of incidents within a sound by sixty, and then dividing it by the duration in seconds.Footnote10 Our studies show that the inner tempo of landscape sounds during our journey at Rousham varies from 0.45 to 120 ().Footnote11 The sounds with lower numbers range from natural phenomena such as wind, to the sound of water features within the garden. Sounds with higher inner tempos are frequently bird sounds and their consistency reflects the call sign of different species.

Figure 8. Inner tempo studies from Rousham Gardens. The inner tempos overlap where there are multiple sources sounding together, 2020.

The auditory nature of these landscape journeys seems to fit within a musical paradigm of temporal plasticity that post-dates the verticality of Eisenstein’s montage and conventional ideas of musical rhythm with their focus on metronomic consistency as a critical aspect of musical time. In seeking to explain auditory time that is not derived from the momentum of a fixed linear tempo the American musicologist Jonathan Kramer defined an alternative notion of temporality, which he termed vertical time. He noted that ‘a vertically conceived piece, […] does not begin but merely starts. It does not build to a climax […] does not end but simply ceases’ (Kramer, Citation1988, p. 55). His notion of vertical time, in providing an alternative to conventional notions of rhythm, better describes the temporal quality of landscape sounds. Rather than these sounds being coordinated by a single ‘tempo’, instead we are drawn into listening to their varied temporal nature which provides a temporal continuum into which the visual moments of journeys through this landscape exist.

What can we note about the scale of these two perceptual fields of vision and hearing? (). In sequence four, seven sounds provide the auditory contribution to this multisensory journey, while in sequence five, there are eight. Additionally in the interplay between these two senses at Rousham, the sounds experienced in the journey through Kent’s design are not coordinated precisely with the visual foci. Many of the sounds of bird song for example, or wind through vegetation, are influenced by the habitat created by the specific plant species used, but there is also a degree of indeterminacy to them. In other areas, for example in sequence 4, Kent controlled the sounds created by the cascade through his design of their height and the speed of water flowing into them from the pond’s outlet pipe. These more deliberate sounds seem to be choreographed with moments of contemplation within Rousham’s spatial sequences. By doing so Kent emphasises both the auditory and visual experiences.

This reveals a remarkable and previously un-noticed aspect of Picturesque landscape experience: both auditory and visual senses are indeed operating in the apprehension of these landscape spaces. Sound may sometimes complement vision, sometimes supplant it, but it is an essential aspect of Picturesque landscape experience as experienced at this particular place. These sounds at Rousham connect us to material and spatial properties of the different landscape characters along the journey. But they do so in slightly different ways from vision, as many of these sounds are experienced acousmatically (Chion, Citation1994). Unable to see many of the sound sources, we are drawn instead to focus on their qualities, from the short bright quality of some bird calls for example, to the gentle fading in and out of others. In the vertical montage of Eisenstein’s films, we find overarching correspondences between the composed sound and visual components, while from our analysis, although they share similar inter-relationships in Picturesque landscapes, the overall composition is sub-divided into smaller units. The ‘scenes’ of a Picturesque landscape are not visual as conventional readings might have us believe, but are in fact multisensory moments in the interplay between the senses. Eisenstein himself saw the critical role of sound, noting that

landscape is the freest element of film, the least burdened with servile, narrative tasks, and the most flexible in conveying moods, emotional states, and spiritual experiences. In a word, all that, in its exhaustive total, is accessible only to music, with its hazily perceptile, flowing imagery. (Eisenstein, Citation1988, p. 217)

Conclusions

Eisenstein’s theory of vertical montage, exemplified in his 1944 film Ivan the Terrible, realised a new compositional method that afforded the means to design the sequential interrelationships between sound and vision in film. He described in reference to Sergei Prokovief’s score, which accompanied the film, that ‘correspondence here is not a "matching of accents"—that primitive method of establishing a correspondence between pictures and music, but the astonishing contrapuntal development of music which fuses organically and sensually with the visual images’ (Eisenstein, Citation1982, p. 63). These ‘correspondences’ not only guided the technical construction of the film, but made it possible for ‘the viewer to create new thoughts and feelings’ (Leyda & Voynow, Citation1982, p. xiii). A corollary to the correspondences of the senses also formed part of the founding principles of the Picturesque. Locke argued in his 1689 treatise that vision was the dominant sense, while acknowledging that the qualities we perceive are not intrinsic to objects directly, but are from the sensations they elicit in us. What applied to vision was also applicable to taste, touch, smell and hearing. As the English author Uvedale Price later noted, ‘the qualities which make objects picturesque, are not only as distinct as those that make them beautiful or sublime, but are equally extended to all our sensations by whatever organs they are received’ (Price, Citation1810, pp. 43–44). From these historic sources, as well as current spatial experiences, we can see the Picturesque as a precursor to the temporal nature of cinema.

While we don’t know whether Eisenstein drew inspiration from Picturesque landscapes per se, James Tobias argues that Eisenstein was fascinated ‘with configurable medial forms, such as the “spherical book,” the adjustable quadratic screen, or the ancient scroll as a protocinematic panorama’ (Tobias, Citation2010, p. 53), and we can potentially see Rousham garden in this prescient light. Vertical montage allows us to better understand the Picturesque by providing a method that allows for the observation and recording of the critical relationship between sound and vision in landscape experience. Our new adapted vertical montage, derived from Eisenstein, when tested through the Picturesque (), provides a new method for landscape architecture to record visual and auditory sequences together, allowing for an enhanced sensory apprehension of movement through landscape space.

These studies add to our understanding of the Picturesque and in particular to our knowledge of landscape time. As Kramer noted, ‘time is a relationship between people and the events they perceive. It is an ordering principle of experience’ (Kramer, Citation1988, p. 5). These studies at Rousham do not just supplement existing understandings of the garden’s composition in spatial terms, but reveal previously unnoticed aspects of the temporal sequences in both sound and vision, and their detailed interrelationships. Our movement through Rousham garden consists of different types of time: the real (although not regular) time of movement; the reflective time created by the allusions and allegories of spatial artefacts discovered during the walk; and the vertical time of the sounds which through their indeterminate starts and cessations create an extended present that shadows our journey. These three temporal types are analogous to Eisenstein’s tripartite elements of picture frames, musical phrases, and pictorial composition in vertical montage. However, in this Picturesque landscape, what is emphasised are the different temporal qualities of landscape experience and movement, celebrating their disparities, rather than seeking teleological connections between them. The spatiotemporal unfolding in Rousham shows both audio-visual correlations as in sequence five but there are also moments where the visual sequences are embedded in longer auditory sequences such as in sequence four, which roll in a misty continuum through our experience. The ‘moments’ of landscape experience are created both by shared properties between senses, but also by their dynamic differences.

Earlier studies by others into the relationship of landscape time and space frequently draw upon Henri Lefevbre’s premise that ‘every rhythm implies the relation of a time with space, a localised time, or if one wishes, a temporalized place’(Lefebvre, 1996, p. 230). Tim Edensor sees these studies as ‘identifying repetition of movements and action, the particular entanglements of linear and cyclical rhythms and phases of growth and decline’ (Edensor, Citation2010, p. 3). In his notes in the introduction to his edited collection of Lefevbre’s rhythmanalysis for spacio-temporal relations, he suggests ‘such rhythms shape the diurnal, weekly and annual experiences of place and influence the ongoing formation of its materiality’ (Edensor, Citation2010, p. 3). In Filipa Matos Wunderlich’s research into place temporality she proposes a conceptual framework for the temporality of urban space in which time ‘is experienced as flow’ (Wunderlich, Citation2013, p. 388), while noting that the temporal activities of spaces ‘are not choreographed activities or tempos’(Wunderlich, Citation2013, p. 389). In her analysis foreground and background sounds resonate and alternate in patterns of intensity, duration, and repetition’ (Wunderlich, Citation2013, p. 391). However, unlike Wunderlich, we don’t see spaces as having a ‘defined temporal structure, metric order and pulse’ (Wunderlich, Citation2013, p. 393), or place-temporality characterised by ‘a sense of balance and resonance’ (Wunderlich, Citation2013, p. 393). Rather, our studies show the nature of landscape time to be highly aperiodic, without a defined pulse, but guided by the rhythm of movement and contemplation.

Kelum Palipane’s Citation2019 investigations into multimodal mapping also draw upon ‘Eisenstein’s concept of vertical montage where different spheres such as sound and visuals could be linked to be perceived together’ (Palipane, Citation2019, p. 93). Her work involves ‘identifying and recording sensory modalities (visual, kinetic, tactile, aural, thermal and chemical) based upon James Gibson’s taxonomy of perceptual systems’ (Palipane, Citation2019, p. 97). Her method draws upon the potential of Eisenstein’s vertical montage to allow ‘strong connection to be developed between the pictorial composition of the movie and the musical score’ (Palipane, Citation2019, p. 100). She divides the sensory experience into insight, body and space, plan, section, and spatial trajectory, providing a mechanism to represent the sociality of the senses (Palipane, Citation2019). Our research however examines not just the nature of the auditory-visual relationship in a particular type of designed landscape, but also examines the nature of this time, bringing an ethnomusicological method to investigate the ‘rhythm’ of a regarded picturesque landscape, and correlates this to the visual sequences. In doing so it contributes to broader debates about spatial rhythm but also provides new insights into the temporality of landscape experience. While it builds upon the investigations of Palipane, Wunderlich and others, it expands on them, providing a novel approach and alternative inter-disciplinary analysis of historic landscapes.

Importantly this model of audio-visual analysis also makes properties of this quintessential Picturesque landscape explicit, providing a means in which contemporary landscape practice might measure its alignment, or indeed distance, from this regarded historic model. In providing landscape practice with the opportunity for better analysis of spatial experience, vertical montage can also be used as a compositional tool. In the eighteenth century Kent drew upon the scenographic principles of the quadratura painters (Cereghini,Citation1991) and his studies from Troili’s historic writings on perspective, both influencing his development of the rich sensory sequences we still find at Rousham. It is now almost 50 years since the American cultural geographer Yi-fi Tuan noted that ‘the taste of lemon, the texture of warm skin, and the sound of rustling leaves reach us just as these sensations’ (Tuan, Citation1974, p. 10) arguing for a broad sensory apprehension of space. The tools developed from this research now provide a means to address the multisensory nature of landscapes, both Picturesque as constructed, and those yet to be conceived.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

David Buck

David Buck is Lecturer of Landscape Architecture at Sheffield University. He has a PhD in Architectural Design and Landscape from The Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL, and has published on the relationship between music and landscape, landscape notation, and on Japanese architecture. His Doctorate by Design was nominated for the RIBA President’s Research Prize and has been published in a sole-authored monograph for Routledge, A Musicology for Landscape, as part of their Design Research in Architecture series. Current research focuses on correlating sound to notions of ecology and the auditory experience of urban space.

Carla Molinari

Carla Molinari is Senior Lecturer of Architecture, and the BA (Hons) Architecture Course Leader at Anglia Ruskin University’s School of Architecture. She was previously Senior Lecturer in Architecture at Leeds School of Arts and Honorary Associate of the University of Liverpool. She has a PhD in Theory and Criticism of Architecture from University Sapienza of Rome and has published on cinema and architecture, on the conception of architectural landscape, and on cultural regeneration. In 2016 she was awarded the prestigious British Academy Fellowship by the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, and in 2014 was the recipient of the Best Young Critic of Architecture Prize (presS/Tletter, Venice). Carla's current research focuses on innovative interpretation of sequences and montage in architecture and narrative in architectural representation.

Notes

1 Choisy, A. (1899). Histoire de l’architecture. Gauthier-Villars; Rowe, C. (1977). “Character and Composition”, in C. Rowe (ed.), The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa and Other Essays. MIT Press.

2 metric, rhythmic, tonal, overtonal, intellectual

3 Cerwén, G. (2020). Listening to Japanese gardens II: expanding the soundscape action design tool. Journal of Urban Design, 25(5), 607–628; Ruggles, D.F. (Ed.). (2017). Sound and Scent in the Garden, Vol. 38. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection; Spence, C. (2020). Senses of place: architectural design for the multisensory mind. Cognitive research: principles and implications, 5(1), no.46

4 Oxford English Dictionary [oed.com]. Accessed on the 9/12/2021.

5 Kent following on from his studies in Italy (1709-19), and of Giulio Troili’s book on the paradoxes of perspective, used axonometric drawings to represent and develop his projects.

6 It is interesting to note that Cullen was one of the key contributors to the Architectural Review’s agenda of the mid-XX century in promoting the Picturesque as ancestor of Modernity. See also, Pevsner, N. (2010) Visual Planning and the Picturesque. Getty Publications.

7 1850 metres in length.

8 The recordings were made by the authors together on the afternoon of November 11th 2019 using a Nikon 1 J1 for stills, a Canon XA15 Camcorder for video, and a Zoom H4n recording sound at 44.1kHz, XY stereo, in WAV format with a windscreen muff, for the sounds.

9 The nine views has been identified during the visit, in places that follow these three main criteria: (1) the path seems to interrupt; (2) an architectural element (i.e. sculpture, pavillion, etc) has been placed; (3) the garden design allows the observer to look at the panorama.

10 Inner tempo supposes that sound events are not singular and bounded, but rather consist of a number of auditory components, for example the parts of a single bird’s call. It is this that allow us to investigate their inner tempo rather than just a single or simple measure of their duration.

11 Compared to say the 150 of a cock crowing.

References

- Aumont, J. (1987). Montage Eisenstein. London: British Film Institute.

- Batey, M. (1983). The way to view Rousham by Kent’s gardener. Garden History, 11(2), 125–132. doi:10.2307/1586840

- Bois, Y.-A., & Shepley, J. (1984). A picturesque stroll around Clara-Clara. October, 29, 32–62. doi:10.2307/778306

- Bruno, G. (2002). Atlas of Emotion: Journeys in Art, Architecture, and Film. New York: Verso.

- Buck, D. N. (2015). A Musicology for Landscape. New York: Routledge.

- Cereghini, E. (1991). The Italian origins of Rousham. In M. Mosser & G. Teyssot (Eds.), The History of Garden Design: The Western Tradition from the Renaissance to the Present Day (pp. 320–322). London: Thames and Hudson.

- Chion, M. (1994). Audio Vision: Sound on Screen. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Cullen, G. (1961). The Concise Townscape. London: The Architectural Press.

- Edensor, T. (2010). Geographies of Rhythm: Nature, Place, Mobilities and Bodies. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Eisenstein, S. M. (1982). Film Essays and a Lecture. Princeton, MA: Princeton University Press.

- Eisenstein, S. M. (1943). Film Sense. London: Faber and Faber.

- Eisenstein, S. M. (1988). Nonindifferent Nature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Eisenstein, S. M. (2010). Sergei Eisenstein: Towards a Theory of Montage. In R. Taylor & M. Glenny (Eds.), (trans.). New York: I.B. Tauris.

- Eisenstein, S. M., Bois, Y.-A., & Glenny, M. (1989). Montage and Architecture. Assemblage, 10(10), 110–131. doi:10.2307/3171145

- Hussey, C. (1967). The Picturesque. London: Frank Cass and Company.

- Kramer, J. D. (1988). The Time of Music. Bellingham, WA: Macmillan.

- Lai, T. S. (2011). Eisenstein and moving street: From filmic montage to architectural space. Design Principles and Practices: An International Journal—Annual Review, 4(6), 383–400. doi:10.18848/1833-1874/CGP/v04i06/37974

- Lefebvre, H. (1996). Writings on Cities. New Jersey: Wiley.

- Levin, M. (Ed.). (1993). Modernity and the Hegemony of Vision. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Leyda, J., & Voynow, Z. (1982). Eisenstein at Work. New York: Museum of Modern Art/Pantheon Books.

- Moggridge, H. (1986). Notes on Kent’s garden at Rousham. The Journal of Garden History, 6(3), 187–226. doi:10.1080/01445170.1986.10405169

- Molinari, C. (2021). Sequences in architecture: Sergei Eisenstein and Luigi Moretti, from images to space. The Journal of Architecture, 26(6), 893–911. doi:10.1080/13602365.2021.1958897

- Palipane, K. (2019). Multimodal mapping – a methodological framework. The Journal of Architecture, 24(1), 91–113. doi:10.1080/13602365.2018.1527384

- Pallasmaa, J. (2012). The Eyes of the Skin. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Price, U. (1810). Essays on the Picturesque, as Compared to the Sublime and Beautiful, and on the Use of Studying Pictures, for the Purpose of Improving Real Landscape (Vol. 1). London: J. Mawman.

- Sherwood, J., & Pevsner, N. (1974). Oxfordshire: The Buildings of England. London: Penguin.

- Stewart, S. (2005). Remembering the senses. In D. Howes (Ed.), Empire of the Senses: The Sensual Culture Reader (pp. 55–69). Oxford: Berg.

- Stiërli, M. (2013). Learning from Las Vegas in the Rearview Mirror. The City in Theory, Photography and Film. Los Angeles, CA: The Getty Institute.

- Stiërli, M. (2016). Architecture and visual culture: Some remarks on an ongoing debate. Journal of Visual Culture, 15(3), 311–316.

- Szanto, C. (2010). A graphical analysis of Versailles garden promenades. Journal of Landscape Architecture, 5(1), 52–59.

- Tobias, J. S. (2010). Sync: Stylistics of Hieroglyphic Time. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

- Tuan, Y. (1974). Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes and Value. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Vidler, A. (1993). The explosion of space: Architecture and the filmic imaginary. Assemblage, 21(21), 44–59. doi:10.2307/3171214

- Warshaw, H. (2018). Music made visible: Sergei Eisenstein's Die Walkiire and the birth of vertical montage. The Wagner Journal, 12(1), 40–66.

- Wunderlich, P. M. (2013). Place-temporality and urban place-rhythms in urban analysis and design: An aesthetic akin to music. Journal of Urban Design, 18(3), 383–408. doi:10.1080/13574809.2013.772882