Abstract

The need to better care for the urban landscape as a cultural, material and regenerative resource is urgent and inevitable. From a planning and design perspective, national heritage characterisation tools currently constitute an explicit point of departure for attributing value to existing urban landscapes, which informs decisions about physical transformations. This qualitative and integrative review focuses on international recommendations and on the ability of national characterisation tools to address ‘relational character’, meaning the interconnectedness of architecture with its situated environment, people and place, atmosphere and the sensory. Although international heritage institutions pledge to include relational character, in our search of state-of-the-art and exploratory approaches to relational character both nationally and regionally, we find that few such tools incorporate relational character, and those that do provide different emphases. We conclude that heritage characterisation tools are not yet sufficiently developed to address existing urban landscapes from a relational perspective.

Introduction

The projected impacts of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions on climate change and its knock-on effects on ecosystems and urban landscapes are well documented (IPCC, 2022), as is the role of the construction industry as a significant contributor to climate change being responsible for at least 40% of global carbon emissions (UNEP, Citation2020), 38% of European waste production (Park, Rakhyun, Seungjun, & Hoki, Citation2020) and 30–50% of raw materials usage worldwide (DG Environment & ECORYS Nederland, Citation2014). Achieving the Paris Agreement demands a decrease in these alarming numbers, in part through a strengthened regenerative practice. In architecture this translates to the reuse and transformation of the existing environment to an unprecedented degree. The European Union’s ‘Fit for 55’ legislative package, which seeks to cut emissions by at least 55% by 2030 (European Parliament, Citation2021), is a recent example of this new focus. Norway’s 2021 urban strategy applies a similar approach, emphasising the renovation and transformation of cultural heritage environments as a sustainable practice to help cut greenhouse gas emissions and manage their consequences (Riksantikvaren, Citation2021). The aim is to provide a proper basis for a more regenerative practice in the transformation of the physical environment by means of the professions of architecture, landscape architecture and urban design and to build a plenum of qualitative and heterogeneous characteristics that continuously impact each other.

Reuse, upcycling and renovation demand adequate tools to assess the existing built environment with a view to its transformative potential. However, the characterisation tools available to register and assess the existing environment are largely developed within a heritage-oriented context, arising from emerging ‘Wandel ohne Wachstum’ practices that had neither sustainability nor the Paris Agreement in mind (Braae, Citation2019; Harrison et al., Citation2020). Nonetheless, these tools are still a key vehicle for the journey from assessment to project development, and are crucial when it comes to communication and value attribution of shared resources.

The values we ascribe to shared resources and urban landscapes are shaped in part by the notation and representation tools. Such tools offer strengths in the analysis of parts and objects, but may overlook values embedded in the interconnectedness of tangible and intangible matter as well as emotionally affective characteristics (Corner, Citation2014), which are subsequently omitted from decisions regarding what to preserve or demolish, and may even sustain existing unsustainable greenfield building practices. Tools to characterise urban landscape elements largely make use of Cartesian representation formats and thereby include values and logics rooted in a positivistic regime (Moore, Citation2019). According to relational philosophy, an adequate characterisation and assessment of existing urban landscapes demands acknowledgement of their complexity, heterogeneity, interconnectedness and ambiguity, as well as a mindset other than the strictly positivist (Haraway, Citation2016; Moore, Citation2019). Philosopher Dorte Jørgensen points to the importance and legitimacy of aesthetic thinking, which relies on sensitive openness towards the concrete and particular while also acknowledging shared complexity and duality (Jørgensen, Citation2015). Relational thinking has become a well-established theoretical approach in the study of sustainability (West, Haider, Stålhammar, & Woroniecki, Citation2021) and urban form (Kiss & Kretz, Citation2021). Scholars, such as Haraway (Citation2016), Ingold (Citation1993, Citation2011), and Puig de la Bellacasa (Citation2012, Citation2017) advocate an increased focus on interconnectedness and sympoietic thinking about the landscape in pursuit of a more thorough understanding of our planet and consequently better ability to care for it. In the heritage field too, scholars have acknowledged the need to address relational qualities and have called for a review of national characterisation tools (Fairclough, Harrison, Jameson, & Schofield, Citation2008; Harrison et al., Citation2020; Veldpaus, Citation2015). This article makes the first step towards a comprehensive review. It provides a multilevel qualitative integrative review or ‘research synthesis’ (Onwuegbuzie, Leech, & Collins, Citation2015) focussing on the ability of national heritage characterisation tools to address relational qualities; moreover, it seeks innovative examples for inspiration and alignment. ‘Relational thinking’ serves as motivation and guiding lens (Torraco, Citation2005) that enables us to ask: How do heritage-related characterisation tools address relational character in our environment?

In what follows, we first describe our methods and materials and thereafter outline our theoretical framework, which served as a guiding lens in a qualitative and integrative review. Dividing relational character into themes cannot be done without some overlap, but categorisation enables us to (1) apply relational character to urban landscape and (2) discuss the gaps in addressing relational character revealed by our findings. We compare international recommendations and agreements and academic research on relational character with national tools’ operationalisation of norms and list our findings according to three non-comprehensive deduced subthemes of relational character: the relationships between (1) architecture and situated environment (object-context relation), (2) people and place (praxeological lived relation), (3) atmosphere and the sensory (phenomenological relation). Finally, we relate the tools to our theoretical framework and discuss their capacity as sensitive methodologies.

Materials and methods

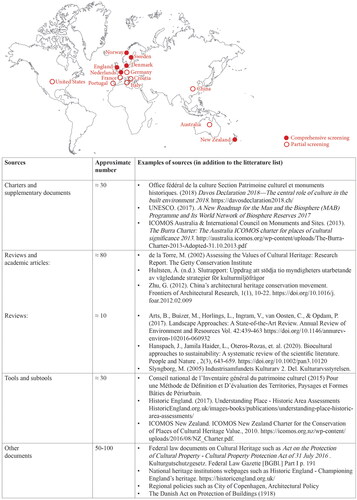

This integrative review of the rapidly expanding body of national cultural heritage characterisation tools is structured conceptually, using a motivational point of departure and a guiding lens (Torraco, Citation2005). Our heuristic approach is appropriate for a mature and diverse knowledge base, and can contribute to the conceptualisation or critique of it, even while that knowledge base continues to expand and develop (Onwuegbuzie et al., Citation2015; Torraco, Citation2005). We studied documents and webpages of four types: (1) academic reviews and articles on characterisation tools; (2) policy recommendations embedded in the agreements and charters of international heritage institutions; (3) formal tools that are normative and prescriptive; (4) less formal subtools developed by research institutions or municipalities. To compile our material, we extracted all the documents mentioned in existing reviews, made an expanded trawl of search engines to include institutional sources, such as ministries and non-governmental interest groups, and reached out to key stakeholders in the field of cultural heritage characterisation. The use of snowballing rather than a predefined, protocol-driven strategy is more likely to identify important sources that would otherwise be missed (Greenhalgh & Peacock, Citation2005). Our search unfolded through references and citations in literature reviews, academic articles, national tools and reports, personal knowledge and input from stakeholders (). We selected the literature through database searches on Google Scholar and at the Royal Danish Library for ‘cultural heritage’, ‘landscape’, ‘architecture’, and ‘review’. The analysis we conducted was qualitative and comparative; similarities and differences across the sources enabled us to make connections and further develop the relational subcategories (Onwuegbuzie et al., Citation2015), which are outlined theoretically in the following paragraph. The process of category-building was cyclical and iterative between the source material and the findings.

Figure 1. Table displaying source categories, approximate number of sources and source examples, which are not included in the references.

Using primary and secondary sources, our review thoroughly covers Denmark, Sweden, Norway, New Zealand, the Netherlands, and England. Our exploration of the United States, France, Germany, China and other countries is limited by the tools available from national public heritage institutions and secondary sources, and in the case of China, includes only the tools that have been translated into English. As indicated by a review of London’s boroughs, there is no single exemplary approach to characterisation; tools have multiplied, mutated and lost a degree of legitimacy (LUC, Citation2016). In Denmark and beyond, we found a wide range of ‘subtools’ developed by municipalities and research institutions—a phenomenon we assume is widespread. We include these subtools in our study of national tools insofar as they contribute innovative approaches and are used by municipal authorities and practitioners in the field.

Relational character: a theoretical framework (and guiding lens)

Before delving deeper into the question of what relational character is and what it implies when applying it to the field of architecture, we will reflect on the nature of characterisation. According to Harrison (Citation2015), the process of characterisation across the heterogeneous field of heritage-making follows a sequence of common steps: categorising, curating, conserving and communicating. Although of a seemingly rational and linear process of characterisation, decisions regarding characterisation that influence what should be included in complex urban landscape transformation processes—what would be the categorising and the curating—rely heavily on what Cohen, March, and Olsen (Citation1972) ‘garbage can’ model describes as the relative availability of streams. Not only are participants fluidly and loosely coupled in decision processes, but problems, solutions and choices follow a temporal order of availability (Cohen et al., Citation1972) and are not as rational as they seem. Additionally, a project which is primarily modelled by its participants can become self-referential and ‘immunise’ itself from external feedback (Kreiner, Citation1995). Thus, the exclusion of certain ‘ambiguous’ types of data points to the embedded strengths and weaknesses of the tools and data used, and to embedded exclusions. As relational characteristics would also belong in the garbage can of decision-making, we must take relational character into account, grasp nuances without simplifying, and include a form of reasoning that enables synthesis and perspective in our reasoning and decision-making processes.

Applying these key aspects of relational thinking to form a heuristic approach within the field of architecture, we aim to integrate relational qualities more profoundly into the ascription of values to existing urban landscapes. We acknowledge that the relational per se crosses thresholds and links together tangible, intangible and heterogeneous parts. Committed to a relational approach, Haraway (Citation2016) points to the failure of individuated systems to enable the study of ‘webbed inter- and intra-actions of symbiosis and sympoiesis, in heterogeneous temporalities and spatialities’ (p. 64). This points to the need for a methodological shift to find new solutions and build thorough respect for, understandings of and appreciation of the relational character of human and non-human habitats. Such relational thinking acknowledges the world as an embodied phenomenon. By contrast, the traditional Cartesian approach disregards metaphysical duality and rests on artificial distinctions between ‘reality and appearance, pure radiance and diffuse reflection, intellectual rigour and sensual sloppiness, absolute and relative, nature and convention, body and mind’ (Moore, Citation2019, p. 314), while phenomena, such as three-dimensional space are described using a positivist approach that disregards aesthetic encounters and sensory experiences and is falsely legitimised as objective. However, according to Lefebvre’s phenomenological conceptualisation, ‘the actual, historic space in which humans live, is always a composite space, which combines […] material, symbolic and empirical components in relative and interconnected form’ (Tygstrup, Citation1970, p. 26). When exceeding the singular object the most straightforward relation is the interconnectedness of architecture and its environment.

Second, approaching urban landscapes anthropologically and philosophically, Ingold (Citation1993) emphasises the interwovenness of lives, the inhabited environment and its subsequent becoming: ‘the landscape is constituted as an enduring record of—and testimony to—the lives and works of past generations, who have dwelt within it, and so doing, have left there something of themselves’ (p. 152). The mutual interaction between people and place is key to any assessment, and ‘the landscape is the world as it is known to those who dwell therein, who inhabit its places and journey along the parts connecting them’ (Ingold, Citation1993, p. 156). Ingold’s ‘dwelling’ perspective on landscape leads us to focus on the interaction between people and place and on the praxiological relation of lived life.

Third, we see atmosphere as a phenomenon that exists between subject and object and is thus quasi-objective. An atmosphere can be entered, and we can be caught up in it (Böhme, Citation2016). Schmitz (Citation2017) defines atmosphere as ‘subjective facts’ and as a self-manifesting factor which—in line with three-dimensional space—affects our experience, both individually and collectively (Wolf, Citation2017). It is a self-manifesting, spatial and sensory phenomenon that is decisive for architectural quality and the character of a place. Accordingly, characterisation is empirically founded and based on a perceptional approach. Moreover, descriptions and projections in architectural representation—such as aerial views, perspectives, sections, and plans—are never neutral or without agency and effect (Corner, Citation2014), and they have limited capacity to register the interconnectedness of relational character. Although the visual is over-represented, it is no more objective than the auditory, olfactory, tactile, or gustatory; our neurological processes differentiate and coordinate information from all five senses for meaningful application (Petersen, Citation2015). The transformation of vision in line with an adjusted ethical awareness depends on our capacity to overcome the challenge of ‘which mediations, forms of sustaining life, and problems will be neglected’ (Puig de la Bellacasa, Citation2017, p. 104). We must therefore also focus on non-visual sensory inputs from architecture and the environment it inhabits, as these too belong to the experience of a place.

To sum up, we have extracted three aspects from relational theory that specify various relational characters that can be associated with the urban landscape: architecture and its situated environment (object-context relation), people and place (praxiological-lived relation), atmosphere and the sensory (phenomenological relation). These aspects help us to identify occurrences of those relational qualities in documents on the safeguarding of the urban landscape.

Policy recommendations embedded in the agreements and charters of international heritage institutions

Below we briefly outline international policy recommendation documents, their foci and their embedded norms regarding relational character, both to explore if and how these norms are adopted in national tools, and to identify national and regional state-of-the-art approaches to relational characteristics.

Tools for the characterisation of the urban landscape (both the built and landscaped) designated as cultural landscapes have largely developed from a set of overarching intergovernmental agreements. While international charters, agreements and research have evolved to include relational characteristics, national tools have not kept pace. During the first half of the 20th century, international policymaking on cultural heritage broadened its scope (Smith, Citation2006; Veldpaus, Citation2015) from the preservation of ‘works of art’ (ICOMOS, Citation1931) to the ‘urban or rural setting’ (ICOMOS, Citation1964), including groups of buildings or sites as works of humans or nature. It is recognised as important to preserve cultural and natural heritage on equal terms and acknowledge them as ‘a harmonious whole, the components of which are indissociable’ (UNESCO, Citation1972, p. 2). This has led to the call for an integrated approach that acknowledges cultural landscapes in their own right and not simply as sites surrounding architectural artworks (Council of Europe, Citation2000). Within the newly established field of biocultural research and policymaking, there is awareness of the plurality of human-nature interactions as co-produced entities (Hanspach et al., Citation2020). This widening of focus, from creation to cultivation, applies to progressive public involvement (ICOMOS, Citation1975) and is supported by the Faro convention, which emphasises its importance ‘in the construction of a peaceful and democratic society’ (Council of Europe, Citation2005, Article 1). In recent decades there has been a move away from intrinsic values identified by experts towards the inclusion of imputed or created values that increasingly disregard the authoritative heritage discourse (Smith, Citation2006). There has also been a recognition that intangible cultural heritage—defined as traditions, practices, representations, expressions and knowledge skills—is deeply interdependent with tangible cultural and natural heritage, and also exists independently of material objects and specific sites (UNESCO, Citation2003, Citation2011). Another neglected aspect of relational character and the intangible is the multifaceted, sensory dimension of space, which is crucial to humans’ sensed experience of cultural heritage and plays an invaluable role in its safeguarding. The 1994 Nara document on authenticity addresses the importance of using diverse sources of information—including spirit and feeling—to make judgements regarding authenticity, although it also reinforces the Cartesian distinction between ‘internal and external factors’ (ICOMOS, Citation1994, Article 13). The sensory dimensions of space (i.e. sounds, smells, light, temperature, and tactility) are no less tied to the physical framework than intangible heritage practices. The 2008 Quebec Declaration accentuates the interwovenness of tangible and intangible aspects in the spirit of place and mentions odour as an important example of intangible elements (UNESCO, Citation2008), thereby affirming that sensory character should be an important factor in decisions regarding cultural heritage.

The sustainability agenda firmly entered cultural heritage policymaking with the historic urban landscapes (HUL) agreement (UNESCO, Citation2016), marking a shift towards reuse and change management in historic cities and a relational thinking that also defines the United Nations’ (2015) sustainable development goals (SDGs). HUL pledges to recognise the ‘layering and interconnection of natural and cultural, tangible and intangible, international and local values present in any city extending beyond the notion of ‘historic centre’ or ‘ensemble’ to include the broader urban context and its geographical setting’ (UNESCO, Citation2011, p. 11). It affirms cultural heritage as a driver of sustainable development and prescribes a progressive approach to community engagement, from education and dialogue concerning management to the active enrolment of the community in decision-making (Veldpaus, Citation2015). The impacts of climate change have been introduced as a new consideration, but the integration of HUL with the strong agenda of the Paris Agreement and the SDGs remains noticeably absent from international recommendations on heritage.

National tools for cultural heritage characterisation

In the following paragraph, our analysis of the national tools breaks down their content according to the three lines of relational enquiry—the object-context relation, the praxeological-lived relation, and the phenomenological relation—and notes the procedures and representational formats used. We primarily examined formal national guidelines and, in lack of such formality, as in the case of subtools, we studied executed characterisation cases. In making this distinction we will not be able to account for any intrinsic relational foci of performed national cases or discrepancies between guidelines and executed cases.

Architecture and situated environment (object-context relation)

Our examination of national tools revealed a predominant use of maps, both in the initial desk research and in summary sections that present findings as ‘synthesis maps’ with notations and symbols. Mapping is highly constitutive of relational character as such, and especially of the relationship between architecture and its environment. It is widely used by design professionals and local authorities engaged in cultural heritage characterisation. Mapping is carried out with regard to existing legal frameworks, natural geographical themes, such as terrain morphology and water elements, and cultural geographical analysis covering historical and current land use. When it comes to characterising object-context relations there is a risk that the interconnectedness between pre-mapped themes, and/or their relationship to unmapped data, would be overlooked. The use of pre-mapped data and pre-drawn frontiers concerns not only physical characteristics but also social aspects, such as geo-referred socioeconomic data. For example, in characterisation practices regarding London’s historic environment, cross-boundary factors and dynamics have been lacking, despite their strong influence on character (LUC, Citation2016).

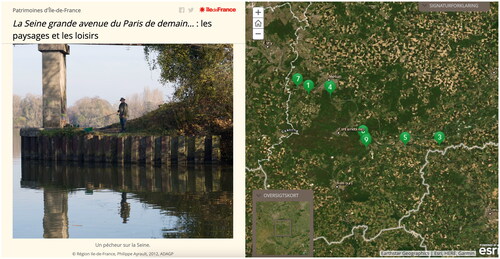

Some tools include knowledge that exists in between the physical, readable landscape, pre-mapped data, and the social inner landscape embedded in communities. One of the earliest such tools that we found is the Dutch ‘landscape biography’ method, developed 40 years ago and reintroduced in the 1990s by Kolen as the cultural biography of landscape. This method includes characteristic ‘unmapped’ or demolished landscape elements, and it potentially reactivates practices that once belonged to the intangible or demolished heritage of the living landscape (Kolen, Renes, & Bosma, Citation2018). Digital cultural biography, a digital enhancement of this tool, allows a wider distribution of participation and knowledge-gathering (Kolen et al., Citation2018). Beyond the prevalent use of pre-mapped data like GIS (Turner, Citation2018), we also detected a tendency to focus on predefined scales, such as in the Danish method SAVE (survey of architectural values in the environment) (Kulturarvsstyrelsen, Citation2011), which focuses on dominant traits, building patterns and detailing. This tendency is even more explicit in a Danish submethodology that performs photo documentation at 1:500, 1:50 and 1:5 (Harlang & Algreen-Petersen, Citation2015), which indicates that form procedures may overshadow specific object-context relations. Although movement in scale and space resemble sensory human experience and therefore appear to be relevant to characterisation, they are largely absent from the tools we explored. One French tool from the region of Île-de-France does however incorporate the experience of routes and the coherence of cultural heritage sites, making extensive use of photographs that are geotagged and made publicly assessable through an ArcGIS platform (Patrimoines d’Île-de-France, n.d.). Such digital thematic routes enable the experience of cultural landscapes in relation to one another ().

Figure 2. The framing of pictures at Patrimoines d’Île-de-France stands out for its presentation of coherence, built and grown intermediacies, and practised use (Patrimoines d’Île-de-France, n.d.). Photographer: Philippe Ayrault, Région Île-de-France.

Scholars have long emphasised that there is a general lack of assessment of landscaped heritage and its relationship to built heritage (Braae, Citation2019; Fairclough et al., Citation2008). Landscaped heritage is typically characterised quantitatively via GIS, which favours nature and ecology via ecosystem services theory, and which tends to characterise human and cultural factors alone rather than seeing them in tandem with natural environments (Fairclough et al., Citation2008). China’s revised principles for the conservation of heritage are notable for assigning values to landscapes. The methodology deploys the phrase ‘the entirety of a site’, which is seen as a cultivated entity that covers the coherence between building, landscape, and industrial and technological artefacts within the proximate study area (ICOMOS China, Citation2015). A recent Danish municipal subtool called peculiarity analysis deploys the subcategory ‘green distinctive character’, which focuses on the experience of a grown environment in its own right as part of an urban landscape and its documented impact on physical and mental health. This Danish tool also uses the term ‘sustainability’ as a potential new way to assess landscaped character, with resilience, biodiversity and carbon emissions included as measurable assessment parameters (Frederiksberg Kommune, Citation2017). Although in this case sustainability resembles a general ecosystem services approach, social value is assigned to landscaped heritage as an aspect of sustainability.

The tool screening of cultural heritage environments innovatively includes an assessment of objects and their societal context as preassigned values and ‘capacities’ (for tourism, settlement, business, and culture), which are presented as a radar chart with rankings from one to five, but there is little transparency regarding the data that should inform the rankings and no assessment of the interconnectedness between them (). Although the tool emphasises the importance of the views of current communities, their engagement is only suggested ‘if the selection of cultural environments using the preassigned criteria can be strengthened by their participation’ (Ostenfeld Pedersen & Morgen, Citation2018, p. 11), and the value attribution is limited to experts only, which brings us to our next relational enquiry.

Figure 3. Process chart from the Danish method Screening of cultural heritage environments shows no involvement of residents. In an example from the guidelines, it is concluded that the site ‘bathing houses in Vesterstrand in Ærø Municipality’, has a low capacity for business since the bathing houses cannot accommodate businesses, and because placing business in them would destroy the cultural environment. The report offers no transparency regarding the basis of the assessment (Ostenfeld Pedersen & Morgen, Citation2018, pp. 7, 35).

People and place (praxeological-lived relation)

International agreements have recommended for decades that ordinary people should be included in the characterisation of cultural heritage, however, scholars have emphasised that this inclusion is inadequate in national characterisation methodologies (Harrison, Citation2010; Harrison et al., Citation2020; Smith, Citation2006). In our analysis of national tools, we found that ordinary people are missing on two fronts: there is a lack of participatory processes for the designation and ascription of value to heritage, and there is a lack of documentation of human interactions with cultural heritage.

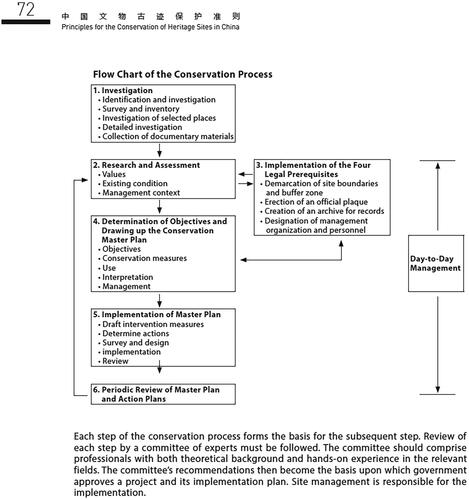

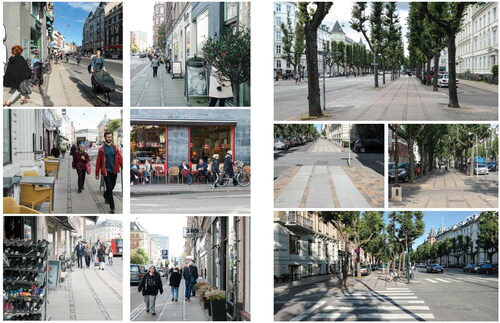

We found very few tools that prescribe the involvement of non-experts in decision-making processes regarding cultural heritage-making. In descriptions of participatory aspects, such involvement is generally targeted at people with special affiliations rather than the general public. The Chinese principles for the conservation of heritage prescribe assessment based on ‘social value’, which encompasses parameters, such as ‘memory’ and ‘emotion’; Article 8 states that conservation requires broad community participation (ICOMOS China, Citation2015). Contrary to previous advice (ICOMOS China, Citation2014), community involvement is absent from the flow chart showing the conservation process, and associated communities are absent from identification, assessment and decision-making processes (ICOMOS China, Citation2015) (). In New Zealand, awareness of heritage-making politics is articulated as respect for diversity in an ethnically diverse society. New Zealand’s significance assessment guidelines encourage citizens’ involvement in decision-making processes and recommend that the assessment of social, cultural, traditional, and spiritual values should be ‘evidence based’ and ‘demonstrated through the extent to which the value […] can be shown’ (O’Brien & Barnes-Wylie, Citation2019, pp. 7–8). This includes measures to be taken by associated communities to maintain the place. However, significance here is based on experts’ assessment of the consequences of any potential loss for the associated community. Further, none of the guiding examples feature pictures of people, which resonates with our finding regarding the lack of documentation of human interactions with cultural heritage. One exception is the Danish peculiarity analysis, whose notion of practised distinctive character focuses on human interactions with built and grown frameworks, thus broadening perspectives on how a place is used and appreciated ().

Figure 4. The flow chart of the conservation process from the Chinese principles for the conservation of heritage shows no involvement of common people (ICOMOS China, Citation2015, p. 72).

Figure 5. Photos from a Danish peculiarity analysis illustrate how ‘practised distinctive character’ in the street Frederiksberg Allé differs from neighbouring streets in respect to use. Practised use of streets is crucial information to include in deliberations regarding future transformational measures (Frederiksberg Kommune, Citation2017, pp. 69, 73).

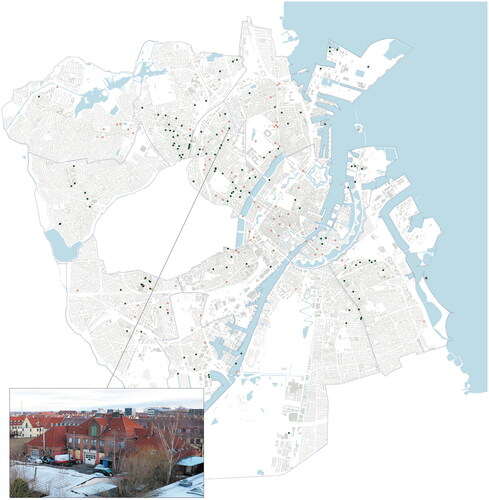

The participatory aspects of the Dutch landscape biography approach and the heritage practice outlined in the Belvedere Memorandum (Feddes, Citation1999) created a notable increase in interest and input from non-experts in determining what qualifies as heritage and how it should be dealt with (Janssen, Luiten, Renes, & Rouwendal, Citation2013). Although assessments were based entirely on experts’ views, public knowledge about and valuation of cultural heritage played an increasingly important role, especially when it overlapped with the experts’ views (Janssen et al., Citation2013). Public and cross-disciplinary participation from the early stages to final decision-making is mandatory in the Netherlands today, and the Belvedere Memorandum may have influenced this (Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed, Citation2012). In 2020, the municipality of Copenhagen asked residents to send photos of buildings they considered to contribute to the city’s soul and thus to be worthy of protection (City of Copenhagen, 2022). Although this campaign focussed exclusively on buildings, it is a noteworthy example of early-stage attributions of value by a broad community and a departure from the general Danish practice ().

Figure 6. During the city’s soul campaign, the city of Copenhagen received 296 nominations of buildings. Eighteen were rejected because they did not meet the criteria, and 34 buildings received multiple nominations, resulting in 217 approved nominations. Map: City of Copenhagen. Photographer: Sofie Stilling.

Atmosphere and the sensory (phenomenological relation)

Acknowledging perception as intelligence, we need to break with the presumption of objectivity found in many tools, and to remain alert to the agency of characterisation. Ongoing faith in the positivist approach has led to contradictory attempts to describe perceptions and sensory impacts as objective. Although our examination of characterisation practices revealed a general lack sensorial character beyond the visual, regions in France open for inclusion of the auditory character using a wider spectrum of documentation, such as narration embedded in practiced use and soundbites, which is collected using ethnographers and photographers in the field research. In Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes soundscapes are made available through a digital platform (INFRASONS, Citation2019), which features an ensemble of songs, instrumental music, life stories, tales, dialects, and legends collected for nearly a century in the region.

UNESCO’s intangible heritage convention aims to define how we understand, register and describe intangibility, emphasising that intangibility can exist independently of specific places or material objects (UNESCO, Citation2011). For some tools, including the Danish national tool for the assessment of conservation values, heritage can only be ascribed a value if it is visible (Kulturarvsstyrelsen, Citation2012). This actively excludes community-ascribed values that may have lost their physical anchor due to previous cultural heritage practices, or which never even had an anchor. Similarly, in the Dutch Belvedere Memorandum, identities ‘are enclosed in spatial structures that can be “discovered”’, neglecting the fact that ‘“identities” are social constructions and are constantly redefined by (groups of) people (Janssen et al., Citation2013, p. 23). We found few tools that operate with intangible heritage as something that can exist as a related activity without physical presence on-site, and one of them is New Zealand’s significance assessment guidelines, in which intangible value extends to art forms, such as paintings and poems. In the process of attributing value, authors are instructed to pay attention to demonstrated or indicated acknowledgements of value by the community—for example, as ‘a source of creative inspiration for art forms, such as literature, art, or music’—or to the use of place as a reference point or symbol of the community (O’Brien & Barnes-Wylie, Citation2019, p. 12). A similar approach is found in the Welsh LANDMAP landscape approach that includes associated intangible activity, such as ‘literary or artistic expressions, such as associations with folklore and poetry, or the depiction of landscape in art or film’ (Natural Resources Wales, Citation2016, p. 3). The New Zealand’s significance assessment guidelines treat the value of sensory experience as more than a subjective notion through the parameter of ‘aesthetic value’, which refers to qualities that are ‘especially pleasing, particularly beautiful, or overwhelming to the senses, eliciting an emotional response’ (O’Brien & Barnes-Wylie, Citation2019, p. 12)—leaning towards the 18th-century aesthetic categories of the picturesque, the beautiful and the sublime.

The Danish subtool phenomenological registration stands out for articulating that architectural value is simultaneously technical, cultural, historical and phenomenological. It is practised through a nine-picture grid or ‘album’, which aims to synthesise the architectural experience at the scales of landscape (1:500), still life (1:50), and portrait (1:5) through analogies with skin (façade), meat (space, volume, figure, and inner spatial organisation) and bone (structure) (). The album and other visual descriptions are intended to create new, independent phenomenological entities (Andersen, Citation2018). This constitutes an operational approach that includes phenomenological character, although in practice the rigidness of the grid and the fixed-focus settings may prevent the phenomena from speaking for themselves. Several tools, such as the Norwegian guide for value assessment (Riksantikvaren, n.d.), operate with the parameter of ‘experience value’, which is defined as something that influences us ‘either individually or as a community’ (p. 1), in a way that is either shared or negotiated, and which is therefore more than subjective. Experience value includes architectural, aesthetic, symbolic and identity values, which may generate feelings, such as wonder, curiosity, reflection or anger, dissolving the distinctions between tangible and intangible, subjective and objective realities, and allowing ambiguity. The Norwegian guide treats tangible and intangible heritage as a unity that constitutes a knowledge bank about a space and is to be included through public participation and ‘negotiation’ during the description, interpretation and evaluation phases of the analysis (Riksantikvaren, Citation2009). The guide promises to include values which can be experienced as well as documented, and it thus encompasses a shared complexity that is essential to expanded aesthetic thinking (Jørgensen, Citation2015).

Figure 7. A nine-picture grid called ‘album’ from the tool Phenomenological registration with the focus settings ‘landscape, still life, portrait’ on the horisontal axis, and ‘skin, meat, bone’ on the vertical axis (Photographer: Boelskifte in Harlang & Algreen-Petersen, Citation2015, p. 79).

In the examination of tools, we generally found alignment with Harrison’s identified steps in characterisation: categorising, curating, conserving and communicating (2015). The procedure starts with desk research, followed by field trips where the desk research findings are compared with field findings, and ending with conclusions summed up in value assessments and recommendations, which are then communicated in printable formats.

Discussion

Tools for cultural heritage characterisation have an indisputable effect on how we formally assess the value of our physical environment, how we make decisions, and consequently how we choose to develop our physical lifeworld. If we are to respond skilfully to changes that occur over time, it is important to assemble both the right data and the right people (Cohen et al., Citation1972) to reflect the multifaceted reality of society and ensure the continuous safeguarding, appreciation, and use of physical environment. As accounted for theoretically, this garbage can model of decision-making must enable the attribution of value to the ‘webbed inter- and intra-actions of symbiosis and sympoiesis’ (Haraway, Citation2016, p. 64) that define cultural heritage and the complex and heterogeneous environment it inhabits; this would require us to dig deeper into the evidence, and doing so would take more time and resources than are currently available. By expanding our understanding of embedded values to include relational character and specifying it into three subcategories, we have been able to identify current knowledge and contextual relational gaps in characterisation. Despite being non-comprehensive, our subcategories have proven to be operational and very relevant, highlighting key aims in transnational documents while also revealing the shortcomings of national tools. Though somewhat beyond the scope of this article, we also found the three subcategories to be capable of bridging some of the unproductive dichotomies that hamper current heritage characterisations, such as objective/subjective and tangible/intangible, as well as exclusively visual approaches. Overall, these direct and indirect findings reaffirm the arguments linked to the focus on relational character in the first place and call greater inclusivity of relational character in the process of categorising, communicating and conserving our physical environment. Compliance with the Paris Agreement, the contribution of construction to climate change, and the shortage of resources must all include contextually defined, praxeological and phenomenological relational value and allow for attribution of value to multisensorial experiences and prioritise continuous use. The latter has recently been described as ‘“letting be” or “letting become” instead of focussing on loss and “letting go”’ (Harrison et al., Citation2020, p. 486). As we have emphasised, this burgeoning movement has not yet been adequately manifested in tools that deal with the characterisation of heritage and the attribution of value. We also need more research on the effects of such involvement on urban planning processes, which is currently lacking (Andersen & Skrede, Citation2021). In the examination of national tools and regional subtools we found subtools taking a more inclusive approach to relational character, which however varies depending on the project and context they address. The mentioned Danish peculiarity analysis includes practiced use and green distinctive character addressing a green streetscape, whereas peculiarity analysis in a bordering municipality does not include such parameters. Similarly, a review of characterisation practices in London’s boroughs found no single exemplary approach to characterisation but a range of approaches ‘cherry-picking’ elements that enable a locally appropriate bespoke approach (LUC, Citation2016). Our findings indicate that lacking adjustment of national tools to international policy recommendations and contemporary demands has fostered an understory of characterisation practices, which may be more efficient but less prone to preserve values beyond what fits the scope of the project. In this article we have pointed to three aspects of relational character that are missing from characterisations, without taking into account other parameters that influence the calibration of tools and the thoroughness and speed of their operationalisation. Such additional parameters might include demographic and economic changes to society, and the privatisation of funding (Harrison et al., Citation2020; Janssen et al., Citation2013), which has reduced the time and resources available for characterisation or even prioritised new development over restoration and reuse (LUC, Citation2016).

Conclusion

Our qualitative integrative review has shown that international policy recommendations call for the inclusion of what we describe as relational character, where heritage is understood from a cultivation perspective, change management is a prerequisite, and the attribution of value involves broad societal participation in all aspects of decision-making. A focus on three subrelations—the contextual, praxeological and phenomenological—has allowed us to specify what we consider to be the most important relational qualities of physical environments and to examine the empirical basis of those qualities. Our examination of national tools and subtools found that the inclusion and operationalisation of relational characteristics is rare and qualitatively insufficient to make a difference in practice. This general loss of relational qualities is due to the tools’ inadequacy regarding the coherence between architecture and its environment, movements in scale, temporal and sensory characteristics (including sounds, smells, and tactility), layers of practised use embedded in the physical framework and in actual interactions between people and space, narrations of sense of belonging, social and ecological value, and physical conditions in the midst of (climate) change. Our research indicates a gulf between international agreements and national tools regarding relational character. While our study has not provided a complete review of national heritage practices, we hope this contribution will catalyse more comprehensive comparative studies that will shed more light on relational character and its notation and communication. We have also highlighted innovative examples that might inspire the recalibration of national tools. While the need to address relational character is acknowledged at the policy level, there is still a significantly long way to go at the level of national characterisation tools, particularly in light of the climate crisis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sofie Stilling

Sofie Stilling is currently an industrial Ph.D. fellow at University of Copenhagen and visiting scholar at ETH Zürich, where she examines how relational character is conceived and conveyed in the early stages of architectural project development. Additionally, she examines the capacity of film to convey relational character, and explores new approaches to characterising and defining regenerative design space in existing urban landscapes. She has a master’s and bachelor’s degree in landscape architecture, as well as a bachelor’s degree in film and media studies, from the University of Copenhagen. She is a co-editor of An Architecture Guide to the UN17 Sustainable Development Goals (2018 and 2020) and has taught film at the Royal Danish Academy—Architecture, Design, and Conservation since 2019. Her ability to think and seek interdisciplinary solutions, as well as bridge an understanding of architectural methodology and visual representation, was gained in part through her work in the consulting sector and as a curator. The industrial Ph.D. is done in collaboration with Copenhagen Architecture Festival—CAFx—Scandinavia’s biggest annual architecture festival and funded by Innovation Fund Denmark and Realdania.

Ellen Braae

Ellen Braae has been Professor of Landscape Architecture Theory and Method since 2009, and Head of the research group, ‘Landscape Architecture and Urbanism’, at the University of Copenhagen. She is currently a member of an expert committee preparing a new national architecture policy. She chaired the Danish Art Council's Committee for Architecture from 2018–2021, was a member of the Independent Research Fund Denmark (2011–2015), and Visiting Professor at AHO, Norway (2010), TU Delft, the Netherlands (2018). Bridging design and humanities, she is the project leader of Reconfiguring Welfare Landscapes (2017–2022), funded by The Danish Council for Independent Research, Culture and Communication, and of the HERA-funded project PuSH, Public Space in European Social Housing (2019–2022). She has published widely on landscape and heritage related matters including Beauty Redeemed: Recycling Post-Industrial Landscapes (2015), (co-edited with H. Steiner) Routledge Research Companion to Landscape Architecture (2018), and Den Grønne Kulturarv. Værdier, udfordringer og metoder hos kommunale kulturarvsforvaltere (2019) [Green Heritage. Values, challenges and methodologies among subnational heritage managers (2019) and most recently Urban Planning in the Nordic World (2022).

References

- Andersen, B., & Skrede, J. (2021). Medvirkningsideologiens inntog i byplanleggingen: En invitasjon til grubling. Kart Og Plan, 114(1–2), 7–21. doi:10.18261/issn.2535-6003-2021-01-02-02

- Andersen, N. B. (2018). Phenomenological method: Towards an approach to architecture investigation, description and design. In E. Lorentsen & K. A. Torp (Eds.), Formation: Architectural education in a Nordic perspective (pp. 74–95). Copenhagen: Architectural Publisher B.

- Böhme, G. (2016). The aesthetics of atmospheres. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315538181

- Braae, E. (2019). Den Grønne Kulturarv: Værdier, udfordringer og metoder hos de kommunale kulturarvsforvaltere. Frederiksberg C: University of Copenhagen.

- Cohen, M. D., March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. (1972). A garbage can model of organization choice. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17(1), 1. doi:10.2307/2392088

- Corner, J. (2014). The landscape imagination: Collected essays of James Corner 1990–2010. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Council of Europe. (2000). The European landscape convention. Retrieved from https://www.coe.int/en/web/landscape/the-european-landscape-convention

- Council of Europe. (2005). Framework convention on the value of cultural heritage for society. Retrieved from https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/rms/0900001680083746

- DG Environment & ECORYS Nederland. (2014). Resource efficiency in the building sector: Final report. DG Environment. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/environment/eussd/pdf/Resource%20efficiency%20in%20the%20building%20sector.pdf

- European Parliament. (2021). Legislative train schedule. Retrieved from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train

- Fairclough, G. J., Harrison, R., Jameson, J. H., & Schofield, J. (Eds.). (2008). The heritage reader. New York: Routledge.

- Feddes, F. (Ed.). (1999). The Belvedere Memorandum: A policy document examining the relationship between cultural history and spatial planning. The Hague: Distributiecentrum VROM.

- Frederiksberg Kommune. (2017). Egenartsanalyse Frederiksberg Allé. Retrieved from https://www.frederiksberg.dk/sites/default/files/meetings-appendices/1096/punkt_305_bilag_2_egenartsanalyse_frederiksberg_alle_2017_lowrespdf.pdf

- Greenhalgh, T., & Peacock, R. (2005). Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: Audit of primary sources. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 331(7524), 1064–1065. doi:10.1136/bmj.38636.593461.68

- Hanspach, J., Haider, L. J., Oteros‐Rozas, E., Stahl Olafsson, A., Gulsrud, N. M., Raymond, C. M., … Plieninger, T. (2020). Biocultural approaches to sustainability: A systematic review of the scientific literature. People and Nature, 2(3), 643–659. doi:10.1002/pan3.10120

- Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Harlang, C., & Algreen-Petersen, A. (2015). Om bygningskulturens transformation. København: Gekko Publishing.

- Harrison, R. (Ed.). (2010). Understanding the politics of heritage. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Harrison, R. (2015). Beyond ‘natural’ and ‘cultural’ heritage: Toward an ontological politics of heritage in the age of Anthropocene. Heritage & Society, 8(1), 24–42. doi:10.1179/2159032X15Z.00000000036

- Harrison, R., DeSilvey, C., Holtorf, C., Macdonald, S., Bartolini, N., Breithoff, E., … Penrose, S. (2020). Heritage futures: Comparative approaches to natural and cultural heritage practices. London: UCL Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv13xps9m

- ICOMOS. (1931). The Athens charter for the restoration of historic monuments. Retrieved from https://www.icomos.org/en/167-the-athens-charter-for-the-restoration-of-historic-monuments

- ICOMOS. (1964). The Venice charter for conservation and restoration of monuments and sites. Retrieved from https://www.icomos.org/charters/venice_e.pdf

- ICOMOS. (1975). The Declaration of Amsterdam. Retrieved from https://www.icomos.org/en/charters-and-texts/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/169-the-declaration-of-amsterdam

- ICOMOS. (1994). The Nara document on authenticity. Retrieved from https://www.icomos.org/charters/nara-e.pdf

- ICOMOS China. (2014). International principles and local practice of cultural heritage conservation. Conference Proceedings May 5th–6th, 2014. Retrieved from https://www.getty.edu/conservation/our_projects/field_projects/china/tsinghua_conf.pdf

- ICOMOS China. (2015). Principles for the conservation of heritage sites in China (revised ed.). Retrieved from https://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/pdf_publications/pdf/china_prin_heritage_sites_2015.pdf

- INFRASONS. (2019). Patrimoines sonores d’Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes. Retrieved from https://www.infrasons.org/

- Ingold, T. (1993). The temporality of the landscape. World Archaeology, 25(2), 152–174. doi:10.1080/00438243.1993.9980235

- Ingold, T. (2011). The perception of the environment: Essays on livelihood, dwelling and skill. New York: Routledge.

- IPCC. (2022). Summary for policymakers. In V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, H. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, … T. Waterfield (Eds.), Global warming of 1.5 °C (pp. 3–24). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Janssen, J., Luiten, E., Renes, H., & Rouwendal, J. (2013). Oude sporen in een nieuwe eeuw. Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed/Netwerk Erfgoed & Ruimte. Oude sporen in een nieuwe eeuw.

- Jørgensen, D. (2015). Nærvær og eftertanke: Mit pædagogiske laboratorium. Skive: Wunderbuch.

- Kiss, D., & Kretz, S. (Eds.). (2021). Relational theories of urban form: An anthology. Basel: Birkhäuser.

- Københavns Kommune. (2022). Byens Sjæl. Retrieved from https://byenssjael.kk.dk/om-projektet-0

- Kolen, J., Renes, H., & Bosma, K. (2018). The landscape biography approach to landscape characterisation: Dutch perspectives. In G. J. Fairclough, I. S. Herlin & C. Swanwick (Eds), Routledge handbook of landscape character assessment (pp. 168–184). New York: Routledge.

- Kreiner, K. (1995). In search of relevance: Project management in drifting environments. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 11(4), 335–346. doi:10.1016/0956-5221(95)00029-U

- Kulturarvsstyrelsen. (2011). SAVE: Kortlægning og registrering af bymiljøers og bygningers bevaringsværdi. Retrieved from https://slks.dk/fileadmin/user_upload/kulturarv/fysisk_planlaegning/dokumenter/SAVE_vejledning.pdf

- Kulturarvsstyrelsen. (2012). Vejledning vurdering af fredningsværdier. Retrieved from https://slks.dk/fileadmin/user_upload/kulturarv/bygninger/dokumenter/Vejledning_til_vurdering_af_fredningsvaerdier.pdf

- LUC. (2016). London plan review, project 3: Characterisation of London’s historic environment. London: Historic England.

- Moore, K. (2019). Towards new research methodologies in design: Shifting inquiry away from the unequivocal towards the ambiguous. In E. Braae & H. Steiner (Eds), Routledge research companion to landscape architecture (pp. 312–324). New York: Routledge.

- Natural Resources Wales. (2016). LANDMAP guidance note 4: LANDMAP and the cultural landscape 2016. Natural Resources Wales. Retrieved from https://cdn.cyfoethnaturiol.cymru/media/677880/landmap-guidance-note-4-landmap-and-the-cultural-landscape-2016.pdf?mode=pad&rnd=131471905520000000

- O’Brien, R., & Barnes-Wylie, J. (2019). Significance assessment guidelines: Guidelines for assessing historic places and historic areas for the New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero. Retrieved from https://natlib-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=NLNZ_ALMA11324405510002836&context=L&vid=NLNZ&search_scope=NLNZ&tab=catalogue&lang=en_US

- Onwuegbuzie, A., Leech, N., & Collins, K. (2015). Qualitative analysis techniques for the review of the literature. The Qualitative Report, 17(28), 1–28. doi:10.46743/2160-3715/2012.1754

- Ostenfeld Pedersen, S., & Morgen, M. A. (2018). Screening af kulturmiljøer: Metodevejledning. Aarhus: Aarhus School of Architecture.

- Park, W.-J., Rakhyun, K., Seungjun, R., & Hoki, B. (2020). Identifying the major construction wastes in the building construction phase based on life cycle assessments. Sustainability, 12(19), 8096. doi:10.3390/su12198096

- Patrimoines d’Île-de-France. (n.d.). La Seine grande avenue du Paris de demain…: Les paysages et les loisirs. ArcGIS. Retrieved from https://www.arcgis.com/apps/MapJournal/index.html?appid=99b90d221ac14a3d82ec05a5ed0e23d8

- Petersen, M. (2015). Sanser og sanseintegration. Rigshospitalet. Retrieved from https://www.rigshospitalet.dk/afdelinger-og-klinikker/julianemarie/videnscenter-for-tidligt-foedte-boern/udvikling/Sider/Sanser-og-sanseintegration.aspx

- Puig de la Bellacasa, M. (2012). Nothing comes without its world: Thinking with care. The Sociological Review, 60(2), 197–216. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2012.02070.x

- Puig de la Bellacasa, M. (2017). Matters of care: Speculative ethics in more than human worlds. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed. (2012). Rekening houden met cultuurhistorische waarden.

- Riksantikvaren. (n.d.). Verdisetting og verdivekting av kulturminner. Retrieved from https://www.riksantikvaren.no/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Veileder_verdisetting.pdf

- Riksantikvaren. (2009). Kulturhistorisk analyse av byer og steder: En veileder i bruk av DIVE-analyse. Retrieved from https://ra.brage.unit.no/ra-xmlui/handle/11250/176956

- Riksantikvaren. (2021). Riksantikvarens strategi og faglige anbefalinger for by- og stedsutvikling. https://hdl.handle.net/11250/2827016

- Schmitz, H. (2017). Kort indføring i den nye fænomenologi. Aalborg: Aalborg Universitetsforlag.

- Smith, L. (2006). Uses of heritage. New York: Routledge.

- Torraco, R. J. (2005). Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Human Resource Development Review, 4(3), 356–367. doi:10.1177/1534484305278283

- Turner, S. (2018). Historic landscape characterisation: An archaeological approach to landscape heritage. In G. J. Fairclough, I. S. Herlin, & C. Swanwick (Eds), Routledge handbook of landscape character assessment (pp. 37–50). New York: Routledge.

- Tygstrup, F. (1970). Affekt og rum. K&K-Kultur Og Klasse, 41(116), 17–32. doi:10.7146/kok.v41i116.15887

- UNEP. (2020). Global status report for buildings and construction: Towards a zero-emission, efficient and resilient buildings and construction sector. Nairobi: World Green Building Council. Retrieved from https://globalabc.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/2020%20Buildings%20GSR_FULL%20REPORT.pdf

- UNESCO. (1972). Recommendation concerning the protection at national level of the cultural and natural heritage. Retrieved from https://en.unesco.org/about-us/legal-affairs/recommendation-concerning-protection-national-level-cultural-and-natural

- UNESCO. (2003). Text of the convention for the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage. Retrieved from https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention

- UNESCO. (2008). Québec Declaration: On the preservation of the spirit of a place. Retrieved from https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/activities/documents/activity-646-2.pdf

- UNESCO. (2011). Convention for the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage 2003. Media kit. Retrieved from https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/15164-EN.pdf

- UNESCO. (2016). The HUL guidebook: Managing heritage in dynamic and constantly changing urban environments. Retrieved from https://www.unesco.org/en/legal-affairs/recommendation-historic-urban-landscape-including-glossary-definitions

- United Nations. (2015). The 17 goals: Sustainable development. Retrieved from https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- Veldpaus, L. (2015). Historic urban landscapes: Framing the integration of urban and heritage planning in multilevel governance. the Netherlands: Eindhoven University of Technology.

- West, S. L., Haider, J., Stålhammar, S., & Woroniecki, S. (2021). Putting relational thinking to work in sustainability science: Reply to Raymond et al. Ecosystems and People, 17(1), 108–113. doi:10.1080/26395916.2021.1898477

- Wolf, J. (2017). Krop og atmosfære: Hermann Schmitz’ nye fænomenologi. København: Eksistensen.