Abstract

Cold War legacies pose significant challenges for heritage management and interpretation at landscape scale. This paper explores an area where management and interpretation overlap, in terms of how postcolonial attitudes usually require something to be done with these sites. We argue that this need not be the case and that a ‘rest state’ can be an important stage in a site’s lifecycle. We focus in particular on United States Ground-launched Cruise Missile (GLCM) sites, of which six were built across Europe. All six are reminiscent of more conventional industrial sites co-located with their occupational communities yet they also exist as homes from home on gifted foreign soil typically occupying large areas. By examining these comparable sites at different stages of their heritage itineraries, we test the validity of some new interpretive and heritage management concepts including, if not leading towards, a rest state.

Introduction

Since the ending of the Cold War in circa 1989 across the Global North, much has been written about its architecture alongside its intangible legacies and their impact on the landscape and on communities (e.g. Cocroft & Thomas, Citation2003; Cocroft & Schofield, Citation2007; Hanson, Citation2016; Hutchings, Citation2004; Jarausch, Ostermann, & Etges, Citation2017; Lowe & Joel, Citation2013; Kuletz, Citation1998). Some military sites were retained largely intact after their closure, decommissioning and disposal, and are now presented as heritage attractions, in some cases with formal protection. One example is the former Atomic Weapons Testing Establishment at Orford Ness, in Suffolk (UK) (DeSilvey, Citation2017), now managed by the National Trust. Some sites continue in military use while others are being re-used by private developers, such as Greenham Common (UK) (Schofield & Anderton, Citation2000). Sites in all of these situations have a relatively secure future. Other sites however are simply abandoned and neglected, slowly fading back into the landscape, to eventually exist only as memories amongst those who worked on these sites or who lived in their vicinity. Most sites within this category are small in scale and hard to find. This neat categorisation hides the fact, however, that some sites fall into more than one category. An example of this is Teufelsberg in Berlin, which offers limited public access and for which a new use may yet be found (Cocroft & Schofield, Citation2016, Citation2019). Similarly to others, this site also now has formal heritage protection.

Since the mid-1990s, these former Cold War sites have been the subject of research, often through the lenses of archaeology and architectural history, researchers using the sites’ extant remains to generate new information about their design, use and afterlife, often in the absence of official records which remain classified or have been lost. In a recent paper (Schofield, Cocroft & Dobronovskya, Citation2021), a transnational approach to interpretation was proposed for these sites, suggesting that more can be learnt about the Cold War landscape by studying functionally comparable sites either side of the former Iron Curtain. In this paper we take a different (albeit complementary) approach, yet one that also recognises a key characteristic of military architecture and design: the construction of often multiple facilities to a standard design brief which resulted in directly comparable sites and buildings existing across the wider Cold War landscape. This repetition of a standard design or template is not unique to military architecture of the Cold War, or even to military architecture in general. It can also exist for industrial sites and domestic architecture. It is however exemplified in the example that we present. In this paper we examine the ways in which these comparable sites provide an ideal lens through which to critically investigate some novel concepts relevant to landscape research and to heritage management.

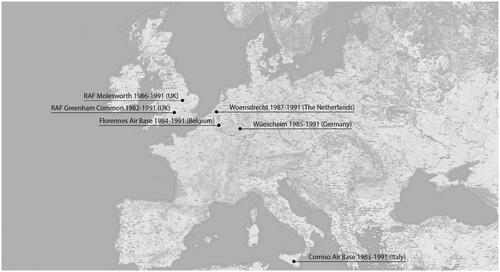

Ground-launched Cruise Missile (GLCM) bases for US nuclear deterrence missile systems are an example of this comparative colonial Cold War heritage, with six directly comparable sites constructed across Europe in the 1980s: in the UK, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Italy (). These bases can be viewed in two dimensions. First, a spatial dimension, in which the statement ‘the same but different’ can be applied and where we examine the sites within their local social and geopolitical landscape alongside the physical environment in which they were positioned. Second, we can also investigate these sites using a temporal scale, doing this in the context of micro-histories, the stories of these sites at local scale and how those stories (representing an approach reminiscent of itineraries, after Bauer, Citation2019; Joyce & Gillespie, Citation2015) can be interpreted through a post-colonial lens. We frame these stories around the idea of the rest state, from Newton’s First Law of Physics, recognising a trajectory through which sites will eventually return to an ‘original’ state, fading back into the landscape, albeit with material, social and often toxic environmental legacies that did not exist before their construction. As stated, the six sites are the same but different, with changes occurring at variable rates meaning that, at any one time, the six comparable sites might appear to be very different, in their use, condition and physical appearance. We look at these sites as any other objects: they can lie dormant, disappear, be reused and change contexts; there is no direct progression from beginning to end (Kersel, Citation2018). Within the context of cultural heritage management, especially at landscape scale, it is important both to recognise the various evolutionary stages through which sites will pass, but also the fact that no one stage necessarily represents a preferred state of being. In accordance with Bauer (Citation2021), we don’t assume a ‘Pompeii premise’ in which an object or site has an authentic and original meaning that should take priority over later transformations, and especially over present engagements. That said, the Cold War sites that we refer to do have origins and an original state in terms of the date at which they were both conceived and then later constructed. Prior to that original state, there was a cultural landscape onto which the sites were imposed.

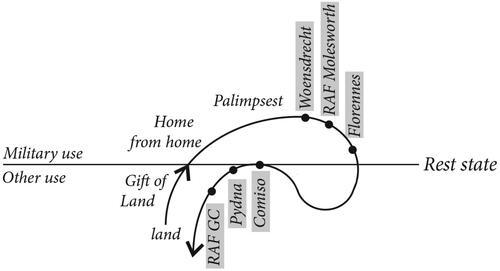

These ‘diverse similarities’ are what make these sites ideal for this investigation. In short, all six sites have three aspects in common (and see ) which are discussed at various points in the theoretical framework that follows:

Figure 2. Graphic layout of the itineraries investigated. Highlighted in grey, the current situation of the six sites is represented. The sites meet the rest state, for instance, between a military use and awaiting a possible future use following closure.

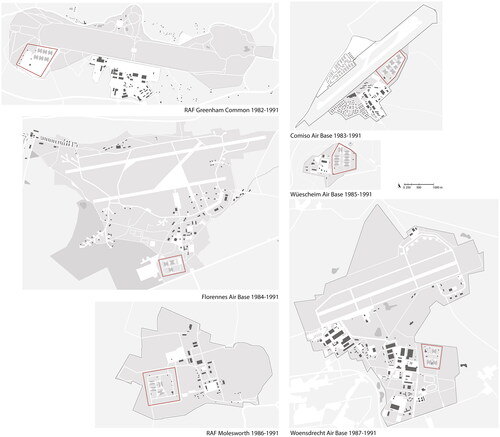

Figure 3. The transitions between land and Land. Current aerial photographs of the six Europe’s GLCM sites, scale 1:100 000 (from top left, clockwise: RAF Greenham Common, Comiso, Pydna, Woensdrecht, RAF Molesworth, Florennes).

the political and ecological land on which these comparative six sites were built;

their colonial status as gifts; and

the occupational communities that make these sites both homes from home, industrial workplaces and contested front line military bases.

We use this comparative conceptual framework to explore new ways to understand the heritage management of these and similar sites where repetition of form and a diversity in their occupational history exists over a wide area and potentially even globally. Specifically we address the notion that heritage management always assumes that sites must be active in some way, performing some purpose; even benign management can be sanctioned or designed through strategy or implied by designation. Instead we argue that recognising a stage of a monument or building’s life as a ‘rest state’ might be helpful, removing the pressure on heritage managers to always have to be doing something. This starts with the idea of Heritage Futures and the suggestion that heritage studies provide a useful framework for investigating alternative futures (Harrison et al., Citation2020) while building also on DeSilvey’s (e.g. Citation2017) notion of curated decay and the need to collaborate with (rather than defend against) natural processes. The difference, however, is that our approach recognises a longer-term cyclic process that is both past- and future-oriented and one that requires no formal curatorial investment. This approach aligns strongly with the notion of itineraries, with all six sites existing within different settings and at different stages of their development, through precolonial, colonial and ultimately postcolonial occupation. As stated earlier, these itineraries are valid both in the spatial exploration within and between the six sites and the temporal inquiry through past, present and future.

Theoretical framework

Land

We begin with the concept of land, recognising an important distinction between this and Land (capitalised), which we believe has strong relevance in the context of colonial occupation through militarism. Here we follow Styres and Zinga (Citation2013, pp. 300–301 and cited in Liboiron, Citation2021, p. 6) who,

capitalise Land when referring to it as a proper name indicating a primary relationship rather than when used in a more general sense. … land (the more general term) refers to landscapes as a fixed geographical and physical space that includes earth, rocks and waterways; whereas ‘Land’ (the proper name) extends beyond a material fixed space. Land is a spiritually infused place grounded in interconnected and interdependent relationships, cultural positioning, and is highly contextualised.

Liboiron additionally states that they use Land when they refer to,

the unique entity that is the combined living spirit of plants, animals, air, water, humans, histories, and events. … land [not capitalised] refers to the concept from a colonial worldview whereby landscapes are common, universal and everywhere, even with great variation (Liboiron, Citation2021, p. 7).

In all of these cases, one might argue, these are places that started as land, became Land, and are now—at various points in time, reverting to land (and landscape) once more.

Gift

Itineraries also refer to the attitude taken towards military sites at various times, including lending the land to foreign forces and then taking it back, the assumption amongst some people being that the site will swiftly be returned to its original (pre colonial) state upon this transition. This assumption also applies to the international political sphere in which these decisions are made, specifically through NATO (within our study area) but also presumably for comparable sites across the Warsaw Pact. The term ‘plasticity’ may be appropriate here, as this implies a return to something that resembles an original form without ever being quite the same again. In the military deployment at each of the six sites, the change came about following the gift of Land. One might draw parallels here from Marcel Mauss’s essay The Gift (Citation2000) with its emphasis on reciprocity and exchange and the idea that collective and individual exchange practices are a foundation of human society. Here, the argument runs, land (and also Land) is given (or loaned) with security offered in exchange in the form of a nuclear deterrent that makes an attack on one’s country less likely (at least in theory). For those living close to the locations of the GLCM sites this will involve both an interpretation of risk (of attack on the GLCM site, which has now effectively become a target) and security (both through the deterrent and through feeling more secure in close proximity to a military base). Local people might think, for example, that they are giving up their land without receiving anything in return; or worse: that they are gifting their land while opening it up to the threat of nuclear attack. Other people might think they have given up their land, but feel safer having done so.

The military control over a place or a landscape that has been gifted has three key features: the physical presence of an occupying force; restrictions over information about that military occupancy; and the management of the civil-military relationship, meaning its discursive as well as its material character (Woodward, Citation2004, p. 35). In the case of the GCLM site in Comiso (Italy), for instance, the United States had no complete military control nor nominal occupation over part of the Italian territory. However, the collaboration between the Italian and American military forces created a situation whereby a place under the military control of Italian forces was granted to American forces for a specific purpose. The presence of deployed nuclear missiles, readied for use, owned by the American forces who supposedly needed the approval of the Italian authorities but still had complete control over them, changed the perspective. The possibility to use these weapons moved the control partly into the hands of American forces. This condition was precisely why both the United States and the Soviet Union arranged agreements with other countries to deploy missiles on their territory. Thus, land within participating countries became of international interest and was gifted for the defence purposes of NATO (and, in eastern Europe, the Warsaw Pact). This notion of land (and Land) and of gifting land opened up the possibility of a conflict which was not totally in the hands of the host countries.

On the return of Land to home countries, it can and often does continue in military use (this is the case of the GLCM sites in Florennes, Wüescheim and Molesworth) or it can be made available for private and public uses. After decommissioning, local communities may feel like they are inheriting something not belonging to them or something they don’t have complete control over. The gifted land can thus become ‘orphan inheritance’ (after Price, Citation2005) which could then become ‘adopted’. If done under certain circumstances, this adoption has the potential to create a space for dialogue between multiple actors. In the case of the six GLCM sites, the gift of the land involving five member nations of NATO has created at least three orphan locations immediately after their decommissioning: RAF Greenham Common, Pydna and Comiso. So who then adopts these places? The various communities of interest might include former protesters (at Greenham and Comiso), festival goers (at Pydna) and at all three of these sites, local people who lived close by or who were formerly employed on the bases, for example in industry, education and administration.

Occupational communities

The communities who occupy the bases have been referred to as ‘occupational communities’ (Salaman, Citation1974), with all or most of the residents employed in the same occupation or by the same employer performing related roles. Local residents may also be employed on these bases in civilian roles (but see below for a contrary view). Mining communities are an obvious example where the mine and the town co-exist, were created at the same time, and most of the town’s residents work for the same employer. Social life and practice are thus tightly interwoven with insiders and outsiders clearly demarcated.

The GLCM sites constitute occupational forms that involve imposition and negotiation through challenging, checking and controlling its community of people and the places where they live (Woodward, Citation2004). Many of these people are from elsewhere (and typically the United States), meaning that the local people who remain will have had to renounce control over part of their territory in order to host another nation’s military units. They have been forced out and replaced by another occupational community. We can therefore view these spaces through the lens of Sykes (Citation2004) definition of alienation, not only of land from people, but also the separation of people from their past and, specific for our case, their present—decisions on land use, for instance. How are the alternative futures of such sites as Greenham Common (previously by definition accessible to everybody) politically and socially negotiated after the disposal and abandonment by the occupying forces? How are these places perceived and used in the present by the local community compared to the time before military occupancy?

Rest state

These multiple perspectives provide the opportunity to closely investigate the various different itineraries that comparative sites can follow, depending on the particular circumstances of individual locations. All of the sites, once abandoned, have the disposition to fade back into their rural landscape with the buildings surviving in various states of repair, depending partly on how useful and reusable they are to those who remain. We define this stage, or pause in the itinerary, as a rest state. In general, the rest state occurs when an area is not actively and officially used by humans. This is different from abandonment in its emphasis on a more biocentric direction. In general, abandonment can take place at any stage in the life of a site or building and can be a temporary phase. It is usually understood as inevitable and potentially harmful in the sense that decay can proceed rapidly. However, we argue that it should be recognised as an active decision to use resources in a different way. In the case of former military sites, when decommissioned, they are often transferred to local authorities that cannot afford to reuse them. Awaiting such resources leaves sites vulnerable to decay without opportunities for public access.

In a state of neglect, the site and buildings return to nature, whether people want it or not. Similar to the concept of fallow land (maggese in Italian) in agriculture, the rest state implies a deliberate decision to suspend activities as opposed to it being due to circumstance (e.g. loss of income). Selecting the rest state as a strategy does not imply any lack of heritage significance. Where heritage protection is discretionary, significant sites can be managed in alternate ways. In this case, the rest state becomes passive, in comparison to adaptive release (after DeSilvey et al., Citation2021, p. 419), retaining in common the fact that they look like processes of loss and decline on one register, but may also generate opportunities for revealing new values and enhancing significance on another. This perspective could be positive in the longer term. For example, the rather unnatural process by which an abandoned site becomes protected as a heritage site needing to be managed, could be replaced by a process of acceptance of the rest state. This has the double-effect of avoiding frustrations connecting to lack of resources while accelerating constructive reuse processes. The example below of Comiso (Italy) shows how the acceptance of this rest state by local authorities could help in reaching small achievements of reuse and integrating the abandonment with part-time (or part-space) utilizations. These ideas are summarised in and .

Table 1. Approaches to buildings and sites after the cessation of their anthropic use.

Table 2. Some characteristics of strategies of change of use and abandonment.

Heritage itineraries

Geopolitical context

After the deployment of SS-20 missiles by the Soviet Union, NATO met in 1979 and, stating that the situation ‘requires concrete actions on the part of the Alliance if NATO’s strategy of flexible response is to remain credible’ (NATO, Citation1979), declared a dual-track decision to be pursued in the following years. One of these tracks involved the United States announcing plans to deploy in Europe: 108 Pershing II launchers (to replace obsolete ones) and 464 Ground-launched Cruise Missiles (GLCMs). On the other track, NATO pushed towards negotiation to mutually limit arms control.

Six sites were chosen to station the 464 GLCMs, five in a concentrated area in northern Europe and one in southern Italy, in a central position to the strategically vital Mediterranean region (). RAF Greenham Common (in the UK, from 1982 hosting the 501st Tactical Missile Wing [TMW], United States Air Force) and Comiso Air Base (Italy, from 1983, hosting 487th TMW) were the first sites to be readied, hosting 96 and 112 missiles, respectively. The deployment at Florennes (Belgium, 1984, 485th TMW) and at Wüescheim (Germany, 1985, 38th TMW) followed with 48 and 96 missiles. At RAF Molesworth (UK, 1986, 303rd TWM) and Woensdrecht (the Netherlands, 1987, 486th TMW), no missiles were operational, and here United States forces stayed active for a relatively short time, building only four and three shelters for the missiles respectively (Cocroft & Thomas, Citation2003, pp. 76, 79).

Building on what we said previously about these sites being the same but different, we define sites like these GLCM sites across Europe as examples of systemic architecture: places built for a common if not identical purpose and to the same design principles. However, while these clear similarities in architectural form and plan do exist across the six sites (), they also vary in size and shape, determined by a variety of historical design and landscape factors. For example, Comiso and Greenham Common were both previously Second World War bomber bases, thus defining the plan-form on which the Ground-launched Cruise Missiles Alert and Maintenance Areas (or ‘GAMA’) was imposed. This recognition of systemic architecture will also survive long after the sites’ abandonment and for as long as its physical form or even its footprint remains, even if the itineraries of these sites are very different.

Figure 4. Plans of each of the six European GLCM sites, outlined within the area of the wider air bases of which they are (or were) a part.

While on one level the GLCM sites distributed across Europe represent examples of what we refer to as systemic architecture, they were also homes from home. In Comiso and at Greenham Common, as at the other four GLCM sites, military personnel created their own homes, and after a short time, made it ‘orphan’ (as discussed above) since they left without making provision for its future. Like all military sites occupied by foreign forces, these GLCM sites represent homes that were at once alien to the outside space while providing a secure internal space that was alien to its locality. It is therefore the border between these inside and outside spaces (in this case a well-guarded and secure boundary fence) that demarcates them and creates the separation, as stated previously (and see Reynolds & Schofield, Citation2010 for an investigation of the boundaries at Greenham).

The decision to deploy Cruise missiles in some European (NATO) countries in the 1980s raised much dissent, both within civilian society and government. Besides describing the sites’ surviving physical remains, and within both the spatial and temporal frames of reference described earlier, we also therefore recognise as significant the various forms of protests that occurred around these sites, and the communities and landscape of opposition that arose as a result (e.g. Schofield, Citation2009, Citation2022).

Peace protests took various forms around all of the sites where GLCMs were deployed. In some instances these involved an attempt to gain power (or at least the right to stay) by the protesters through the property purchase of land or annexes in the proximity of the military bases. In Florennes, for example, an article in The New York Times (in 1985) reports the café Florennade opened by a group of young anti-nuclear activists. Florennes is described as ‘an economically depressed town of 11 500 [people] set among gentle, pastoral hills in southern Belgium’ and ‘not the kind of place where … the ''peace movement’' gets a very warm reception’ (Bernstein, Citation1985). A similar downplaying has also been used in the Italian media. While some may argue that Comiso had become a ‘Peace-town’, newspapers and television programmes tried to minimise the phenomenon. When forced to talk about it, they would disfigure it: a barrage of toothpicks, an army of visionaries, an organisation of fifth columns of foreign powers (Soviet Union, Libya, Berlin, Cuba, Nicaragua); always a unilateral movement contrary to national interests (Calabrese, Citation2008, p. 119). In Comiso, pacifists also used urban tools to ensure the right to stay around the base, such as multi-property fields in the south and south-west called Verde Vigna (green vineyard) and Ragnatela (spider web). Here the protests took the form of demonstrations: the spread of ‘Comitati Comiso’ in Germany, Holland, Belgium, Sweden, Norway; visits of leaders of peace movements from Europe, the United States and Japan; hunger strikes; and even an intrusion carried out by two women during the night in 1984.

These activities and perceptions are an example of the many different social and political (as well as physical) layers that contribute to the complexity of these six places and their associated memories and perceptions. It is a complex picture that has been enriched in a very short time by different entities or actors. As part of the presence of local communities with different levels of endorsement to the military, the scene seemed monopolised by two opponent groups: the military forces that controlled the space; and the anti-nuclear protesters that attempted to usurp this control in different ways, but mainly through counter-occupancy. In this dispute, the role of space is crucial: the needs of those opposing armament was manifest in the right to occupy the proximity of those places designated by the deployment decisions. The protesters moved here from their homes to exert their power of interference, adding value to lands once insignificant, forgotten or simply functional.

Of the six sites, those which stayed operational for the longest time were RAF Greenham Common and Comiso Air Base, both left by the United States forces in 1991. At the moment these are the sites, together with Pydna in Wüescheim, to have been decommissioned by the military forces. The other three sites are still used for military purposes. It is one of these two longest surviving sites therefore (Comiso) that we selected to form the focus of our study. Some images showing the current state of Comiso are included as and .

Comiso (Italy)

The air base in Comiso was inaugurated in 1937 by Benito Mussolini, making it the symbol of the strategic role that the fascist regime wanted for Sicily, as ‘the centre of the Empire’ (Mazzeo, Citation1991). Then, in circa 1980, The United States developed it as a place to store missiles while also creating an entire settlement for base personnel. Following its closure, a plan for the transformation of Comiso into a civil airport was initiated in 1999. As a document, the Plan for this development is helpful in describing in detail the facilities that remained at the abandoned site, giving a sense of what ‘home’ looked like for the site’s resident community: row houses and larger residential buildings with a capacity of 5000 people (military and civil); a medical centre; supermarket and shops; school and kindergarten; cinema/theatre; chapel; recreational and sporting facilities: gym, outdoor swimming pool, soccer and basketball fields, and squash courts, a bowling centre; restaurants; the Fire Brigade Command; the water tower; the Aerospace Ground Equipment; watchtower; and service buildings (Provincia Regionale di Ragusa, Citation1999). Like the other five GLCM sites, this US base was built to be self-sufficient: all the fundamental (and some additional) needs could be satisfied within its perimeter. Food, including fresh fruit and vegetables, was flown from the United States directly into the airbase. Integration with local residents was not the goal. Records of Comiso’s employment office show this reticence towards integration. The office had opening hours from 2 to 4 pm, even in Sicilian summer when all of the locals would take a siesta. Instead, they employed a cook who had lived in the United States and was able to grill following the American culinary traditions (Calabrese, Citation2008, p. 151) rather than employ anyone local. Integration was stronger at Greenham Common than it was at Comiso, perhaps due to the common language.

In 1987, the municipality of Comiso awarded the two governments of the United States and the Soviet Union with the Premio Comiso Per la Pace (Comiso Prize for Peace) ‘to have reached the historic agreement which would delete intermediate range nuclear missiles from European territory’ (as printed in the pamphlet depicting the outcome of the celebration). The representative of the United States, Katherine Shirley, diverted the attention of this political move to the cultural relationships between Italy and the US, remembering how ‘Italy, the US and the other nations [that are] part of NATO will continue fighting for long lasting peace based on our freedom values, dignity of the individuals and democracy’. Meanwhile, the message she brought on behalf of President Ronald Reagan addressed the past contribution of Comiso and Italy under NATO and the importance of ‘peace within liberty’. The representative of the Soviet Union looked at the past as well, and at the contribution Comiso made to eliminating the ‘Euromissiles’, noting that the word Comiso ‘loses its missile-sinister meaning and adopts another value, as a symbol of agreement, dialogue, and reciprocal trust’. He also stressed that the Soviet Union ‘will not soften its commitment for the radical recovery and complete removal of the military threat in Europe and the entire world’. This was the first time the destruction of weapons was caused by negotiation instead of war. However, it takes time for all traces of militarism to fully leave a place even after the personnel have gone and the site is decommissioned (Dunlop & Schofield, Citation2021; Woodward, Citation2004). A similar fate exists for ‘the memory of Occupation [which] will not immediately lose its potency when the last of the Occupation generation has gone’ (Carr, Citation2014, p. 3).

Yet the memories of Comiso do not recall victory, and the 1987 prize-giving could be, instead, the symbol of the defeat of both the United States and the Soviet Union. According to the agreement for dismantling the missiles, part of Comiso Air Base had to be under the control of the former Soviet Union until 2001 (Comune di Comiso, Citation2000, p. 1). There was an end to the war, therefore, but a return for nobody, not least those local people whose land it was to ‘gift’ in the first place. Even while people remember the colonial past, significant features of the postcolonial present can be forgotten, including a cosmopolitan city’s powerful ties to distant places in a wider post-colonial world (Sykes, Citation2004). It has left this space firstly ‘orphan’ (of the United States), in ‘foster care’ (of the Soviet Union) and finally ‘alone’: a multi-layered abandoned landscape. Elaborating on Assmann’s work on dialogic forgetting and remembering (Assmann, Citation2009, p. 33) which argues that, after the Holocaust, the aim was to transform the asymmetric experience of violence into symmetric forms of remembering, in the case of the Cold War, one could suggest that the violence has had a symmetric (missing—in Europe) form while the result is an asymmetric memory. This is often the case of remembering within online forums and amatorial musealized military sites, presented in a ‘technostrategic’ way (Cohn, Citation1987, p. 690), using technical details and making violence completely invisible. This approach blights the possibility to reflect upon the social and political aspects of warfare and militarisation rather than influence future decisions, such as going to war again (Wendt, Citation2023, p. 22).

Discussion and conclusions

As previously described, three GLCM sites remain in military use. But in the case of the former Greenham Common, Comiso and Pydna Air Bases, the areas have been left and abandoned, in one way or another. This means that the land has been made available again to its hosting communities. The current state of these three sites is very different. At Greenham Common, a collective reuse project has been pursued and accomplished, involving public and private stakeholders. In Pydna, a midpoint situation exists in the form of its reuse for an annual music festival. In Comiso, most of the structures are now abandoned, with the urban plans figuring as part of the civil airport area. It could be said that the area ‘is waiting to be repurposed’. In December 2021, the area was the object of four project proposals by different research institutions participating in a call for funding by the Italian Ministry of the South. The proposals include: a Green Energy Valley, for scientific activities for green solutions; an Agrifood Euromed knowledge hub, for the qualification and enhancement of eco-sustainable agrifood in the marginal areas of the Mediterranean; a regional hub of tourism and Mediterranean cultures; and a University hub for research and training in Sicilian aerospace for weather-climate and environmental monitoring.

The process of reuse of these former foreign military bases involves different variables. The resources employed and the physical fruition determines various outcomes and balances between the economic and heritage values of the land and of the surviving buildings. At Greenham Common, both the land and the buildings have reverted to public use (the common, control tower museum and a cafè) alongside private entities (the companies within the business park). Some of the buildings of the complex, including the Control Tower since 2012, are designated as listed buildings. The cruise missile shelters of the GAMA site have been protected as a Scheduled Monument since 2003 and are used as workshops.

Comiso, Pydna (for most seasons of the year) and Greenham Common (in parts) are in a rest state. But while at Greenham Common and at Pydna, this situation has been accepted and officialised in their reuse intentions, in Comiso, the situation is different. Here, reuse is still considered a prerequisite to ‘solve the situation’ of its abandonment. And while waiting for this resolution, the site is closed to the public. The control of the site still seems crucial, therefore, to solving the equation. Even if the municipality does not have enough resources to manage the vast area, they think that the best way to handle it is to keep its gates and fences closed, acting through their control, similarly to the way that the military used to operate their authority. The rest state has a lot to do with exerting control over space. In some cases, this behaviour is due to lack of resources. In other cases it is due to the lack of will to release the information around the site’s past use. What would it mean in Italy and in other countries to make these places visible? How would this challenge perceptions of the country’s position during the Cold War? However one frames these questions, these are places with a high level of dissonance, not least since their success as sites of nuclear deterrence remains disputed.

We can summarise our argument by highlighting these networks of sites through what we term itineraries. This recognition of sites having their own and also collective (or ‘group’) itineraries presents more flexible interpretive and management frameworks than one built around biographies (e.g. after Kopytoff, Citation1986) not least in their ability to collapse temporal distinctions between past, present and future and help to consider entanglements as central to their stories (after Bauer, Citation2019, p. 336), including their future stories. Such itineraries allow us to focus on lines and traces (like contrails in the sky, which are fluid and temporary and often appear to intersect), on the relationships between human and nonhuman actors and objects, and on context, while avoiding privileging one aspect of a story over others. Itineraries give places life, or multiple lives. They recognise diverse and multiple meanings. With itineraries, there is no end. Places are living things. They exist within meshworks of interwoven journeys along which life continues to be lived (Ingold, Citation2007), resembling the threads protestors constantly weaved into the fences at Greenham Common to reduce their brutality and soften their impact. By adopting these new ideas and especially the notion of a rest state within the GLCM itineraries, management and interpretation are drawn together in a way that recognises how places change while embracing the cultural and political complexities that drive change at different paces and often in different directions. Whatever the context, the rest state can be a much-needed pause for thought.

Acknowledgements

Grateful thanks to On.Salvatore Zago for kindly making available his personal archive on the history and political circumstances of Comiso Air Base, and to Aldo and Sharon Pulvino for the collaboration.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Simona Bravaglieri

Simona Bravaglieri is Research Fellow and Adjunct Professor at the Department of Architecture of Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna. She holds a PhD in Preservation of the Architectural Heritage at Politecnico di Milano with a thesis on ‘The heritage of the Cold War. Identification, mapping and preservation of decommissioned military buildings and sites in Italy (1947–1989)’. Research interests include cultural heritage and sustainability, urban and rural regeneration, built heritage in the post-conflict and catastrophe context, and gender studies. She is also part of the editorial staff of the journal ‘ANANKE’, founded by Marco Dezzi Bardeschi, one of the primary references for the preservation debate in Italy since the end of the 20th century. Among her most recent publications are: ‘The Politics of the Past in Kosovo: Divisive and Shared Heritage in Mitrovica’ in Transforming Heritage in the Former Yugoslavia. Synchronous Pasts (Palgrave Macmillan, 2021); and ‘Beyond the Damage, the Reconstruction of L’Aquila’ in Historic Cities in the Face of Disasters (Springer, 2021).

John Schofield

John Schofield researches and teaches cultural heritage management and contemporary archaeology in the Archaeology Department, University of York (UK). Prior to this, he worked for Historic England’s Characterisation Team where he worked in heritage protection and policy developing a particular interest in recent military heritage and in understanding people’s social and communal values for everyday places. John holds adjunct status at the universities of Turku (Finland) and Flinders and Griffith (Australia). He is Corresponding Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities and Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in London. His latest book, Wicked Problems for Archaeologists (OUP), is due for publication in 2024.

References

- Assmann, A. (2009). From collective violence to a common future: Four models for dealing with a traumatic past. In R. Wodak & G. A. B. d’Olmo (Eds.), Justice and memory - Confronting traumatic pasts: An international comparison (pp. 14–22). Vienna: Passagen Verlag.

- Bauer, A. A. (2019). Itinerant objects. Annual Review of Anthropology, 48(1), 335–352. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-102218-011111

- Bauer, A. A. (2021). Itineraries, iconoclasm, and the pragmatics of heritage. Journal of Social Archaeology, 21(1), 3–27. doi:10.1177/1469605320969097

- Bernstein, R. (1985, March 9). Belgian town sees reasons to welcome missiles. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1985/03/09/world/belgian-town-sees-reasons-to-welcome-missiles.html

- Calabrese, G. (2008). La storia sulle ali. L’aeroporto di Comiso oltre il Novecento. Modica: Moderna.

- Carr, G. (2014). Legacies of Occupation: Heritage, Memory and Archaeology in the Channel Islands. Cham: Springer.

- Cocroft, W. D. & Thomas R. J. C. (Eds.). (2003). Cold War. Building for nuclear confrontation 1946-1989. Swindon: English Heritage.

- Cocroft, W. D. & Schofield, J. (Eds.). (2007). A fearsome heritage: Diverse legacies of the Cold War. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Cocroft, W. D., & Schofield, J. (2016). Der Teufelsberg in Berlin. Eine archaeologische Bestandsaufnahme des westlicher Horchposten im Kalten Krieg. East Berlin: Christoph Links Verlag.

- Cocroft, W. D., & Schofield, J. (2019). The Teufelsberg and Western Electronic Intelligence Gathering in Cold War Berlin. Boca Raton, FL: Routledge (Research Focus Series).

- Cohn, C. (1987). Sex and death in the rational world of defense intellectuals. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 12(4), 687–718. doi:10.1086/494362

- Comune di Comiso. (2000). Relazione Aeroporto di Comiso. Comiso: Comune di Comiso.

- DeSilvey, C. (2017). Curated decay: Heritage beyond saving. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- DeSilvey, C., Fredheim, H., Fluck, H., Hails, R., Harrison, R., Samuel, I., & Blundell, A. (2021). When loss is more: From managed decline to adaptive release. The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice, 12(3–4), 418–433. doi:10.1080/17567505.2021.1957263

- Dunlop, G., & Schofield, J. (2021). ‘The technological sublime’: Combining art and archaeology in documenting change at the former RAF Coltishall (Norfolk, UK). Internet Archaeology, 56, 1–13. doi:10.11141/ia.56.16

- Hanson, T. A. (2016). The archaeology of the Cold War. In The American experience in archaeological perspective. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

- Harrison, R., DeSilvey, C., Holtorf, C., Macdonald, S., Bartolini, N., Breithoff, E., … Penrose, S. (2020). Heritage futures: Comparative approaches to natural and cultural heritage practices. London: UCL Press.

- Hutchings, F. (2004). Cold Europe. Discovering, researching and preserving European Cold War heritage. Cottbus: Department of Architectural Conservation at the Brandenburg University of Technology.

- Ingold, T. (2007). Lines. A brief history. Boca Raton, FL: Routledge.

- Jarausch, K. H., Ostermann, C. & Etges, A. (Eds.) (2017). The Cold War: Historiography, memory, representation. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Joyce, R. A., & Gillespie, S. D. (2015). Making things out of objects that move. In R. A. Joyce & S. D. Gillespie (Eds.), Things in motion: Object itineraries in anthropological practice (pp. 3–19). New Mexico: School of Advanced Research Press.

- Kersel, M. (2018). Itinerant objects: The legal lives of Levantine artifacts. In A. Yasur-Landau, E. Cline, & Y. Rowan (Eds.), The social archaeology of the Levant: From prehistory to the present (pp. 594–612). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kopytoff, I. (1986). The cultural biography of things: Commoditization as process. In A. Appadurai (Ed.), The social life of things: Commodities in cultural perspective (pp. 64–91). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kuletz, V. L. (1998). The tainted desert: Environmental and social ruin in the American Midwest. Boca Raton, FL: Routledge.

- Liboiron, M. (2021). Pollution is colonialism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Lowe, D., & Joel, T. (2013). Remembering the Cold War: Global contest and national stories. Boca Raton, FL: Routledge.

- Mauss, M. (2000). The gift: The form and reason for exchange in archaic societies. New York: W.W. Norton and Co. (Original work published 1925)

- Mazzeo, A. (1991). Sicilia armata. Basi, missili, strategie nell’isola portaerei della Nato. Messina: Armando Siciliano Editore.

- NATO. (1979). Communique of a special meeting of foreign and defence ministers Brussels 12th December 1979. NATO Archives Online. Retrieved from https://archives.nato.int/communique-of-special-meeting-of-foreign-and-defence-ministers-brussels-12th-december-1979.

- Price, J. (2005). Orphan heritage: issues in managing the heritage of the Great War in Northern France and Belgium. Journal of Conflict Archaeology, 1(1), 181–196. doi:10.1163/157407705774929006

- Provincia Regionale di Ragusa. (1999). Aeroporto “Magliocco” di Comiso, Piano Regolatore Aeroportuale. Ragusa: Provincia Regionale di Ragusa.

- Reynolds, L., & Schofield, J. (2010). Silo walk: Exploring power relations on an English Common. Radical History Review, 2010(108), 154–160. doi:10.1215/01636545-2010-009

- Salaman, G. (1974). Community and occupation: An exploration of work/leisure relationships. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schofield, J. (2009). Aftermath: Readings in the archaeology of recent conflict. Cham: Springer.

- Schofield, J. (2022). The Cold War: Archaeologies of protest and opposition. In E. Casella, M. Nevell & H. Steyne (Eds.), Oxford handbook of industrial archaeology (pp. 649–662). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schofield, J., & Anderton, M. (2000). The queer archaeology of Green Gate: Interpreting contested space at Greenham Common Airbase. World Archaeology, 32(2), 236–251. doi:10.1080/00438240050131216

- Schofield, J., Cocroft, W., & Dobronovskaya, M. (2021). Cold War: A Transnational Approach to a Global Heritage. Post-Medieval Archaeology, 55(1), 39–58. doi:10.1080/00794236.2021.1896211

- Styres, S., & Zinga, D. (2013). The community-first land-centred theoretical framework: Bringing a ‘good mind’ to indigenous education research? Canadian Journal of Education, 36(2), 2894–313.

- Sykes, K. (2004). Arguing with anthropology: An introduction to critical theories of the gift. Boca Raton, FL: Routledge.

- Wendt, M. (2023). Gendered frames of violence in military heritagization: The case of Swedish Cold War history. Journal of War & Culture Studies, 16(1), 21–40. doi:10.1080/17526272.2021.1902093

- Woodward, R. (2004). Military geographies. New York: Wiley-Blackwell.