Abstract

The speed of climate change calls our attention towards the life forms on this warming Earth – human and beyond. In this article, I aim to contribute to the conversation about how we co-exist by presenting multispecies ‘compost stories’ of the Norwegian town Vardø, which seems to be well underway in a post-Arctic shift. Vardø has received much attention over the past decade from researchers and artists. However, efforts to describe this socially and historically dynamic place are often concentrated on the built heritage and primarily human history. With a newly built community greenhouse as my point of departure, I unfold various multispecies stories connected to the concepts of demarcation, domestication, change and acceleration that I encountered during a summer in Vardø. Curious about the hidden stories of Vardø, I ask how to remain loyal to a place’s history while incorporating new stories that just keep accelerating in their relevance.

Introduction

It is June 2022 and the Vardø-based activist group Dyrk Varanger [Grow Varanger]Footnote1 is just about to complete a community greenhouse constructed with recycled materials (). The greenhouse project has been developed in cooperation with the project Common Resources – Strategies for a circular, balanced and shared management of areas under pressure at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design (AHO), and designed by architecture students from In Balance – Arctic Cycles, a studio course led by Tine Hegli and Kristian Edwards. Old windows from near and far have been reassembled, caulked, and painted in a deep green colour, and many locals have put in hours of voluntary work. They have done this both because of the prospects of local vegetable produce and for the community that is being nourished while they build. In times where new opportunities emerge as a consequence of rising temperatures, Grow Varanger seems to be developing place ‘based in love and performed as care’ (Larsen, Citation2023).

This is the spirit of Vardø, a small town situated on an island in the Barents Sea just off the tip of the Varanger Peninsula in Finnmark. In Vardø, as in so many smaller towns that still have a lively connection to their past, many stories abound, and they are often interwoven with place-specific practices and ideas of spirit and self-understanding. They can be deeply connected to distinctive climatic, geological and biological factors or agents. Building a greenhouse above the 70th parallel north in times of climate change is one such addition to the history of Vardø – a history with many intertwining trajectories (see, for instance, Balsvik, Citation1989a, Citation1989b; Balsvik & Nielsen, Citation2008; Hagen, Citation2015, Citation2019). The Varanger Peninsula is a multi-ethnic place where different cultures meet and cross paths with one another, and where the three languages Northern Sami, Kven and Norwegian are spoken.Footnote2 The cultural diversity and associated complexity are reflected quite well in the history of the village Skallelv, located half an hour’s drive from Vardø (). Skallelv, which is known as Gállojohka in Sami and Kallijoki in Kven, was registered as a Sami village in 1825. However, only 30 years later it was recognised as a Norwegian village, and by the year 1900, all the inhabitants of the village were considered Kven (Johansen, Vange, & Alm, Citation2010, p. 9). ‘How people in the village identify today is up to each individual’, explain Cecilie Johansen, Vibeke Vange and Torbjørn Alm in a booklet about Skallelv (2010, p. 9, author translation).

Figure 2. Map showing the location of the Varanger Peninsula, Vardø and Skallelv. Source: Ida Højlund Rasmussen, based on maps from norgeskart.no / © Kartverket (CC BY 4.0).

Returning to Vardø, the town is mostly considered Norwegian. However, the town sign also includes the Kven name, Vuorea, which illustrates a connection to the Kven heritage. It is known that the Indigenous Coastal Sami population inhabited Vardø, but they moved away during the 1860s, ‘[w]hen bushes and driftwood that were used for firewood had been used up, when the grass had been grazed too hard, or when the Norwegian immigrants got too close’, as described by historian Randi Rønning Balsvik (Balsvik, Citation1989a, p. 257, author translation). That the Sami population moved away must also be seen in the light of the gradual development of a Norwegian central administration in Vardø, and the violent witchcraft trials of the 17th century that took place at the Vardøhus fortress and where Sami ‘magic’ was ruthlessly pursued (Hagen, Citation2015). As described by historian Rune Blix Hagen, territorial and resource conflicts resulted in a need for scapegoats, which led to a demonisation, especially of coastal women and Sami men (2015, pp. 89–90). Trade and demarcation have also influenced the development and demography of Vardø. In early modern times, Russians and Karelians came to trade with the Coastal Sami in areas of Finnmark where Norwegians collected taxes, and consequently, Vardøhus was built to secure Norwegian supremacy (Balsvik, Citation1989a, p. 15). Two hundred years of PomorFootnote3 trade relations enabled Vardø to prosper, and these are still of importance to the town (Balsvik, Citation1989a, p. 36,91). During the Second World War, Vardø was seen as an important strategic position and was thus transformed by the German Nazis into Festung Vardø, and Skagen, the large recreational area north of town, was fenced off with barbed wire and fortified with military bunkers and emplacements (Balsvik, Citation1989b, p. 209).

If we are to understand places as processes (Massey, Citation1991), all the historical trajectories described above can be seen as dynamic sequences that figuratively layer up and intertwine with one another, and thus contribute to the sense of Vardø as place. Vardø as place has received much attention over the past decade from researchers and artists alike, although efforts to describe this dynamic, social and historical place are most often concentrated on the strikingly dilapidated built heritage and the presence of primarily human history. In this article, I will unfold various multispecies stories connected to the concepts of demarcation, domestication, change and acceleration in Vardø. To direct attention towards the diverse layers of Vardø stories, I ask how we can remain loyal to the history of a place while incorporating new stories that just keep accelerating in their relevance.

Why storytelling in the Anthropocene?

New ways of understanding coexistence require new ways of telling stories. Inspired by ‘compost writing’ (Haraway, Citation2019), I will unfold various stories I encountered in Vardø through the actions or growth patterns of our non-human neighbours, but also through the activities and responses from human communities. Compost writing is a way of ‘writing-with in layered composing and decomposing’, as stated by Science and Technology Studies (STS) scholar Donna Haraway (Citation2019, p. 565). Acknowledging that history is not linear, but is rather made up of many entangled strata of stories, can help expand the understanding of existence, but also of a place. But why this kind of storytelling, and why now? Telling stories in the Anthropocene is a matter of relating to and envisioning other realities (Haraway, Citation2017). Similar to nesting dolls, Haraway writes, ‘[s]tories […] nest inside ever more stories and ramify like fungal webs throwing out ever more sticky threads’ (Haraway, Citation2019, p. 565). Passing on the stories that are increasingly made visible to us through biological activities can thus be seen as a way of layering stories, of broadening the scope of stories that contribute to, for example, Vardø as place. In the ‘multispecies turn’, which is closely connected to fields such as critical posthumanism, actor network theory, new materialism, and post and decolonial theory, etc., new methods are needed, as argued by Cypher, Bubandt, and Andersen (Citation2022). Accordingly, telling other-than-human stories of the Anthropocene does not mean marginalising human influence and inequality:

In fact, it is the opposite: a refocusing of diverse histories of human agency, injustice, and suffering through their complicity and synchronity (sic!) with relations to nonhuman beings and forces in a multispecies, historical landscape shaped by modernity and colonialism. (2022, p. 4)

Fieldwork and cultivating attentiveness in the post-Arctic

The stories in this article are based on four months of fieldwork that was conducted in the summer of 2022 as part of my doctoral research that focuses on soil, landscapes and resource management in Vardø, and is part of the Common Resources project. In Vardø, I participated in dugnad (a Norwegian term for collective, voluntary work efforts) at the newly built community greenhouse, co-gathered beach herbs with the local chef, did interviews and harvested a small school garden. Learning from anthropologists and multispecies studies scholars (Mathews, Citation2022; Tsing, Citation2015; van Dooren et al., Citation2016), I also cultivated a curiosity towards the landscapes, as I wandered through them and got a sense of what summer is like in this particular place, and not least at this latitude. Attentiveness is about acknowledging others and bearing witness to their lives and realities. An attentive engagement with both human and non-human communities can be seen as an on-the-ground method, a sort of ‘rubber boot method’ (Cypher et al., Citation2022), where one both literally and metaphorically puts on the most appropriate kind of footwear when entering a given context.

Besides appropriate footwear, doing fieldwork in Vardø also requires a windproof and woollen wardrobe – even during summer. That said, it is warmer in this region than the latitude indicates, due to the Gulf Stream, the southwestern winds, and the midnight sun (K. Jørgensen, Citation2015). The effect of this has been accelerating in recent years, thanks to climate change. The current scientific measurement indicates that temperatures are rising much faster in the Arctic regions, and in Vardø, the average temperature is expected to rise 3.7 °C by the year 2100 (AMAP, Citation2021; Støstad, Citation2020). On the one hand, this change might contribute to providing Vardø with fresh vegetables, especially when the community greenhouse and its outside growing area are up and running, but it might also change the prevailing story of Vardø being an Arctic and barren place. Vardø may become post-Arctic, in a literal understanding where the addition of the prefix post refers to places that were once considered Arctic but where climate change has pushed them beyond their former ‘Arcticness’. The term post-Arctic was originally introduced by historian and Arctic scholar Michael Bravo to address the evolving issues of neo-colonial interests in the Arctic, and to create a post-colonial common ground for Arctic studies that rejected old Western and Eurocentric imaginaries of the high north (Bravo, Citation2015). But, as Bravo pointed out, there was an elephant in the room called climate change (2015, p. 12) – an elephant that has grown in size ever since.

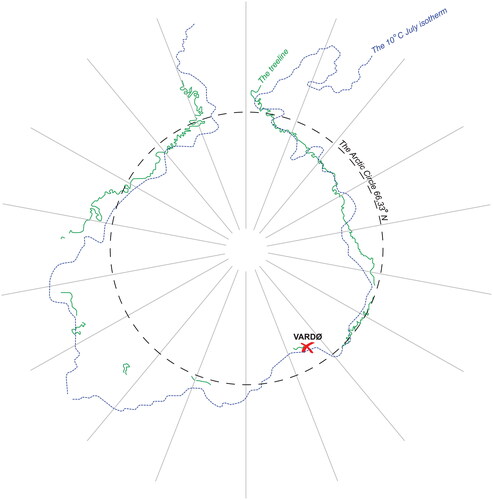

The question of how the Arctic is defined often arises when discussing Arctic matters, and there are many definitions. In the natural sciences, the treeline (the geographical limit at which trees can grow) or the 10° C July isotherm (which defines places where the average temperature in July is 10 °C or less) are often used. While some scholars consider the Arctic a condition (Larsen & Hemmersam, Citation2018) and compare its landscapes to poems (Hastrup, Citation2010), others are sceptical of the fundamental idea of the Arctic as an entity and would rather contemplate it as a bearing, which can embrace the volatility and the symbolic discourses that are also part of the ‘arcticulation’ of the Arctic (Vola, Citation2022). Geographer Louis-Edmond Hamelin has contributed with a pragmatic, yet holistic, approach with his 10-parameter index on defining Nordicity, where factors such as natural phenomena, population numbers, transportation services and degrees of economic activity should all be seen as linked (Hamelin, Citation1978, pp. 19–21). In this way, the treeline, for instance, becomes inseparable from the cultural meaning of trees in an Arctic community, as argued by founding partners of the Toronto-based Lateral Office, Sheppard and White (Citation2017).

Vardø in the middle of a post-Arctic shift

These definitions, whether based on natural science, qualitative research or first-hand experience, are important in a society like Vardø. Here, narratives and stories coalesce in the historical buildings, in the landscapes and in the memories of people. The Arcticness of Vardø, for example, is connected to the idea that nothing can grow in this cold region, as articulated in the literary work Sang til Vardø [Song for Vardø]. Here, Norway’s national poet, Nordahl Grieg, expresses how, in Vardø, there is ‘[…] no hope for trees and soil does not yield crops’ (Grieg, Citation1946, p. 35, author translation). Although it was seemingly not Grieg’s main purpose to describe soil conditions in Vardø in his collection of war poems, Song for Vardø nevertheless says something about how Vardø was perceived by Grieg in his time: as a barren place without hope for life. In some ways, this is still a prevailing narrative. It is reinforced by Vardø’s status as the only climatic Arctic town in Norway (understood in accordance with the 10 °C July isotherm), which is a notion often used for tourism and marketing purposes. Painted onto the façade of the hotel, which is known for the culinary creations of Varangerkokken [the Varanger chef] and his use of local herbs and resources, is a large blue sign that says: ‘Vardø Hotel – in the Arctic climatic zone’. Likewise, the front page of the digital tourist information portal, Visit Vardø, states that ‘Vardø is Norway’s north-easternmost town, and the only one in the Arctic climate zone’ (Visit Vardø, Citation2023), and this narrative is also encountered in the promotion of Vardø at Hurtigruten – a coastal route transporting both cargo and people, mostly tourists, along the Norwegian coast (Vardø – gateway to the Northeast Passage, Citation2023). The Arctic climate in Vardø is even mentioned in a book about the presence of American intelligence services in Norway (Wormdal, Citation2015, p. 137). However, the climate is changing, and it can be felt in the landscapes. Vardø may be in the middle of a post-Arctic shift, both imaginatively and physically, where on the one hand narratives become unstable, and on the other opportunities emerge. Growing vegetables in hotbeds and greenhouses has been practiced for a long time in Vardø, as we will see in the next section, so the novelty lies rather in the intersection of a changing climate (that enables an extended growing season, including directly in the ground) and changing narratives. The fact that climate change is offering possibilities in some places prompts the question of how to approach these, while also acknowledging the disasters in other places – or, as Anna Tsing, Andrew Mathews and Nils Bubandt put it: ‘[c]an we acknowledge catastrophe while also imagining possibility?’ (2019, p. 192).

Vegetable growing in the Arctic is indeed connected to the question of what is possible in this place – a question that many others have asked themselves before Grow Varanger. The first layering of stories I will introduce here emerges from recent literature on cultivation in the high north, and it illustrates that vegetable growing in these regions is not just a climatic matter, but also a sociocultural phenomenon connected to nation-state building and colonialism.

Stories of demarcation and domestication – agriculture in Northern regions

Cultivating soil in the far north is a matter of natural conditions, but also a matter of persistency, patience and skills. It is furthermore entangled with colonisation patterns and ideas of growth (Friedrich, Citation2021; Lien, Citation2020). In the chapter The quest for fresh vegetables: Stories about the future of Arctic farming (2021), senior fellow Doris Friedrich touches upon the Canadian and American history of Arctic farming, where cultivation was part of a colonisation project aimed at ‘educating’ the Indigenous population out of famine. This project failed partly because agriculture was not introduced as a component that could fit into the customs and cultural structures in the communities (2021, p. 196). Similarly, in the Varanger Peninsula, agriculture was once introduced by the Norwegian state, albeit with different purposes. In the article Dreams of prosperity – Enactments of growth: The rise and fall of farming in Varanger (2020), anthropologist Marianne Lien investigates different historical encounters that can illustrate how southern cultivation ideals were implemented in the north in various ways. One example is the national bureising [settlement agriculture]Footnote4 movement of the 19th and 20th centuries. The bureising movement was an internal colonisation project with the general aim of establishing new farms and farmlands all over Norway, and it was intertwined with the assimilation processes often referred to as Norwegianisation, which were particularly dominant in coastal areas (Andersen, Citation2003, p. 250; Lien, Citation2020, p. 51). Securing the national borders was part of this, but it was also about ‘settlement by the right kind of people’, as Lien writes (Lien, Citation2020, p. 52, emphasis in original). The nomadic or half-nomadic settlement patterns of the Sami population and their low or non-traceable use of natural resources became the direct opposition to bureising, to settlement, and thus to secure national borders. In this way, the story of agricultural settlement in the north also enters a larger narrative of Norwegian nation-state building.

Vardø’s former role as the administrative centre of Finnmark meant that many state officials, often from the southern parts of Norway or Denmark, settled down for shorter or longer periods and brought their agricultural traditions with them. Parsons and military commanders grew vegetables in the parsonage garden and at the fortress with the help of the Oslo-based botanist, Fredrik Christian Schübeler (Balsvik, Citation1989b, p. 29). His lifework was centred around Norwegian seed production, and he established a network of experimental farms all over Norway to figure out which species could be grown under which conditions – one of these was in Vardø (Borgen, Citation2017, p. 95). Schübeler wanted to demonstrate that northern seeds were better and heavier – a thesis he based on the influence of the intense period of the midnight sun and its effect on the formation of starch, and how the grains developed greater nitrogen-free components (Schübeler, Citation1886, p. 151). Today, the writings of Schübeler can be read as an introduction to what was possible to grow in northern regions in his time, but his observations on crop productivity, maturation processes, mean temperatures, and precipitation also mirror some of the changes that have happened over the course of approximately 150 years. Schübeler reports that the normal average July temperature in Vardø in the 1880s was 8.7 °C – a figure that can be said to be more ‘climatic Arctic’ than the average July temperature in 2022, which reached 11.9 °C (Schübeler, Citation1886, p. 121; NCCS, 2023). The next stories are connected to precisely change, and how change can be traced through biological agents in the landscapes of Vardø.

Stories of change – king crabs and mosquitos on the move

The red king crab, also known as Paralithodes camtschaticus, is considered a delicacy not only in eastern Finnmark but all over the world, and is an essential part of the local export market in Vardø (Larsen, Citation2019, p. 25). However, it has not always been crawling around on the seabed surrounding the island. Since the red king crab was first deposited in the Kola Bay by Russian scientists in the 1960s, it has spread along the Norwegian coastline and become an invasive species in the Barents Sea (Sundet & Hoel, Citation2016). Although this newcomer on the sea floor causes a lot of trouble, it has also become an integral part of eastern Finnmark – in fact, a playground in the shape of a red king crab was created just a few years ago in the city of Kirkenes. Beyond the lucrative economic benefits, the red king crab is also an ecological threat – and hence represents a double-sided management dilemma that is expected to become even more relevant due to increased globalisation and climate change (Sundet, Citation2011). However, the red king crab continues its migration and will probably reach Svalbard waters by 2030 (Sætra, Citation2019).

On an evening in June 2022, I became acquainted with another newcomer in Vardø when I was invited to a picnic at the Skagen beach. The name Skagen means headland, and that is exactly what it is: a vast tongue of land with a varied landscape where geological rock formations and bunkers from the Second World War merge with small pebble stone beaches, cloudberry fields and crowberry heather. The locals who invited me said it was the kind of evening that there is only one of each summer. The midnight sun kept us awake, it was strangely mild, there was no wind, and we greeted the northbound Hurtigruten ferry that calls at Vardø at around 3.30 am. But there was one annoying thing about this in all ways scenic evening: the mosquitos. And they were quite a new phenomenon in Vardø, I was told. The assumption was that the mosquitos had arrived because summers kept getting warmer and warmer. If the locals had not told me that the presence of mosquitos on a summer’s evening was uncommon in Vardø, it would never have occurred to me, as I come from a place where the presence of mosquitos on a summer’s evening is expected. Such a story reflects a circumstance that can be felt in the landscape and that can be subject to critical interpretation. Paying attention to biological agents is a necessity to capture such testimonies, but so are the stories associated with them. I could only acquire the local knowledge, which explained the novelty of the arrival of the mosquitos, through conversations with the locals in Vardø. These stories also illustrate how not only the outdated stories (for example, the Arcticness of Vardø) but also the newly arrived ones (be they mosquito or king crab stories) may force people to reconsider their understanding of the place they inhabit. But not only are things changing, they are changing at a certain pace.

Stories of acceleration – trees and shrubs above the treeline

Anthropogenic realities are largely characterised by acceleration, as stated by philosopher Rosi Braidotti (Citation2022, p. 68). In Vardø, fast-paced stories are also present. The story goes that, due to the cold climate and its position above the aforementioned treeline, Vardø only has one single tree: an old rowan leaning up against the pale-yellow wooden walls of Vardøhus fortress. Rowans have a long history of serving as courtyard trees and they are connected to mythology, weather forecasts and magic. For instance, the rowan is said to bring luck and protection when it is placed in a courtyard, but misfortune if it is brought on a boat (Sandberg, Citation2017, p. 208). Rumour has it that the rowan in Vardø was first planted by a soldier in 1950, but in the early 2000s it had to be felled and was later replanted by pre-school children (Sandberg, Citation2017, p. 211). The ‘fact’ that this rowan is the only tree in Vardø is, however, ‘a well-known falsehood’ as the local newspaper, Østhavet, wrote ahead of a tree height measurement competition in 2019 (Jørgensen, Citation2019). Since then, many other rowans have been planted in Vardø, and the story of the solitary rowan at Vardøhus is perhaps exactly that: just a story.

Another connected story can be found when walking past Vardøhus following a gravel road to Skagen. Here, on an August evening in 2022, I noticed that the fireweed, willow thickets, angelica, yarrow and bog star were growing side by side along the road. A polar front had lost its grip on the island and been replaced by a gentle breeze, variable cloud cover and a low evening sun. Although the willow thickets are supposed to be low, dense shrubs, which in some cases can become ‘tree-like’ (Botanical & plant physiology encyclopedia, 2019), they were taller than a person and could easily be mistaken for trees – at least to the non-trained eye. The only reason why I took note of them on that evening, was because I remembered how Janike, my supervisor, told me that the willows had grown taller during the more than 10 years she had been visiting the island, and it is now one of the changes she maps with her students. Paying attention to plant morphology dates back to ancient times. An example of this is how observing and understanding plant and tree morphology has been an important factor in the development of terracing systems in the Mediterranean areas, as described by anthropologist Andrew Mathews (Citation2022, p. 14). It might just be an amusing oddity that the treeless town of Vardø hosts a tree height measurement competition, although in fact, it features shrubs that have grown to the size of trees in just a few years. However, it can also be regarded as a very clear example of a landscape in change.

Similarly, the crowberry, Empetrum nigrum, that grows between the willows is perhaps the most prominent example of face-paced change, although unknown to most people (). Ecologists are now collecting data to show how the crowberry is expanding to such a degree that may affect the entire tundra, perhaps turning it into a ‘green desert’ (Bråthen, Citation2017; Bråthen, Gonzalez, & Yoccoz, Citation2018). These stories of suddenly thriving species that spread, propagate and take over could be understood as species using the climatic changes to their advantage. As Braidotti observes: ‘Life is matter that chooses on the basis of sensory information and has the power to transform the organism by transferring that information’ (2022, p. 124). From a non-human perspective, perhaps the growth patterns of these vigorously flourishing plants can be translated as plants simply acting on their surroundings. In other words, the shrubs and crowberry heather may just be doing what is in their power in order to thrive as well as possible. Nonetheless, they show us that stories of the Anthropocene are stories of change and destabilisation that may be in need of reconsideration and reconceptualisation.

Representations tell stories too

We could consider greenhouse building above the 70th parallel north, vigorously growing shrubs and crowberry along with newly arrived mosquitos and crabs as testimonies to a reality that is moving away from the prevailing representations of it, as we encounter them in the stories about Vardø – whether it is to do with a moving treeline or an Arcticness that is about to disappear.

Perhaps it does not matter too much whether a place like Vardø is in fact Arctic or post-Arctic according to a climatic definition. Hamelin argues that the 10 °C July isotherm may not be the best indicator for delimiting an area anyway. He writes: ‘[W]hat is the relevance of a single aspect, during a single month of the year, expressed as a mean value? Not much!’ (Hamelin, Citation1978, p. 16). Still, the limits, boundaries and isotherms on maps tell stories, similar to how the map below () tells a story. Similarly, the thickness of lines on a map can matter quite a lot, as demonstrated by Alessandro Petti, Sandi Hilal, and Eyal Weizman (with Nicola Perugini) (2013) when addressing the historical partition plans of Palestine. They describe how ‘each line was dictated by the sharpness of the drafting instrument, the scale of the map, and the kind of surface it was drawn on’ (2013, p. 151). In the contested context of Palestine, one of the main questions concerned the ownership of the width of lines drawn on military maps, as the actual stroke of the pen represented quite large areas when translated from map to reality. Although it is not about ownership when it comes to the temperature- or vegetation-based lines drawn on an Arctic pole-centred projection, these Arctic definition lines do have the capacity to establish a certain set of facts about the world. As they are derived from science, we believe them to be true – and they might be or might have been. To reflect the rapidly changing climate, the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) decided to update the general climate normals in 2021 (Meteorologisk institutt, Citation2021), but does that affect narratives connected to certain meteorological characteristics, such as, for instance, the Arcticness of Vardø? Maybe not. In a Latourian vein, one could argue that these Arctic definition lines drawn on a map constitute ‘immutable mobiles’, meaning inscriptions that have become widespread truths through copying and distribution (Latour, Citation1986). Maps, images and writings are examples of such inscriptions that need to be mobilised and made immutable in order to spread and eventually convince others. In the same way as coastlines on maps cannot tell the dynamic story of tides and gradually rising sea levels, neither can Arctic definition lines on maps report on de facto tree growth or whether the average temperature in July is in fact 10 °C or less. These lines live in the narratives connected to a place, although they might be absent when you physically look for them in Vardø.

Figure 4. Arctic lines. Source: Ida Højlund Rasmussen. Based on map from Arctic Portal, AMAP / www.arcticportal.org. Used with permission from Arctic Portal.

The discrepancy between narratives and realities

The discrepancy between identifying stories and on-the-ground realities is brought to the fore by the very speed of climate change. While it is critical to pay attention to life worlds beyond the human, it might be equally important to understand how changing narratives affect human communities, especially those that are located in the ‘periphery’ and are thus (often) far from central decision-makers. In Vardø, stories and distinctive narratives are important, as we have seen, as they are fundamental to certain parts of the town’s economic basis. Even so, change and adaptation to new realities is nothing new to people in Vardø. Here, increased fishing regulations have affected the fishing industry, and the historic buildings have often been repurposed, as described by landscape scholar Janike Kampevold Larsen (Citation2019, p. 26). During my summer in Vardø, I experienced how a new boat was welcomed in the harbour with applause and fireworks. Such a festive welcome illustrates that fishing, despite several periods of decline, is still highly valued and is undoubtedly a large part of the town’s identity. Identification with place can be seen as a way of connecting to one’s roots and sticking to a story portraying a familiar reality. In this way, stories are needed. By noticing changes in landscapes, both past and future can be reimagined (Mathews, Citation2022, p. 6), and by layering instead of erasing or neglecting stories, they become part of a historical assemblage, where it is possible to stay loyal to the past while adding new narratives about the present. This also opens up for a discussion of future stories, and how they will be affected by the narratives that are important in our time. What we consider significant or insignificant today can be reproduced and thus become immutable mobiles if we do not continuously revisit history and stay curious towards what we cannot see.

The discrepancy between on-the-ground experiences and stories, like the ones connected to Arctic definitions, poses a dilemma that is not too different to the double-sided management problem of the red king crab. On the one hand, the Arcticness and treelessness of Vardø speak to a tourism industry that thrives on a (perhaps soon to be outdated) climatic uniqueness. On the other hand, the Arcticness and treelessness become proxies of a place in ecological crisis. It is perhaps precisely in this tense relationship between economic forces (that enable human settlement) and ecological care that the dream of local vegetable produce above the 70th parallel north can become a bridge-builder. Is it possible to imagine the possibility of growing fresh, organic vegetables while acknowledging that the climate is changing at a deeply disturbing pace? Bearing the work of Cypher et al. in mind, addressing such divergence could be a way of bringing a focus to ‘diverse histories’ (2022, p. 4). It is necessary to dare to bring observations of landscapes into conversation with larger discussions about climate change, and as Mathews points out: ‘We need to be bold enough to move from our sensory experiences of plants, animals, soils, and people – to larger scales in time and space’ (Mathews, Citation2022, p. 32). Trees in a seemingly treeless town can give an indication of how this place is changing, and narratives without an obvious host body, like the Arcticness of Vardø, can be challenged and perhaps altered without being completely rejected. They can be reinvented, and their relevance can change over time. Acknowledging that ‘nothing tells its own story’ (Haraway, Citation2019, p. 565) and drawing on the ‘arts of attentiveness’ (van Dooren et al., Citation2016) can open up for multiple storytellers to emerge and for multiple stories to be told.

Now, having unfolded a few of the more or less visible multispecies encounters I had during a summer in Vardø, I cannot help but think about all the stories that are left. Imagine how many compost stories can be excavated from the shell sand surrounding Vardøhus. Think of the lives of the larvae hiding in the cracks of the historic houses, and the history of the pebble stones that rubbed and rolled against each other before they ended up on the seashore of Skagen. Perhaps the planks of the community greenhouse floor, which once served as the quay of Vardø, can report on conditions south of the treeline?

Acknowledgments

The first draft of the article was written as an essay for the PhD course ‘Ecologising History: Loss, Memory and Landscape Temporalities’ at the University of Oslo. Thanks to Marianne Lien, Ursula Münster, Laura Ogden and Þóra Pétursdóttir for accepting me onto the course and for teaching it – this was truly inspiring. An earlier version of this article was presented at the Northern Political Economy Symposium at the University of Lapland, Finland. Thanks to Monica Tennberg and the Arctic Centre for this opportunity and for the comments. I am also very grateful for the insightful comments by two anonymous reviewers, and my supervisors, Janike Kampevold Larsen and Even Smith Wergeland. Finally, I wish to thank the community of Vardø for sharing a summer and their stories with me.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ida Højlund Rasmussen

Ida Højlund Rasmussen is a PhD fellow at the Institute of Urbanism and Landscape at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design (AHO). She has a cross-disciplinary background, holding a bachelor’s degree from Aarhus School of Architecture and a master’s degree in urban planning and communication studies from Roskilde University. LinkedIn: linkedin.com/in/ida-højlund-rasmussen-92095882

Notes

1 Translations of titles, names and words from Norwegian to English are introduced first with the original Norwegian word followed by the English translation (either official or translated by the author) in square brackets.

2 The Sami population are the Indigenous people of Norway, and the Kven people (also known as Norwegian Finns, descendants of Finnish immigrants) are a national minority (regjeringen.no, Citation2018).

3 The Pomors were tradesmen from the White Sea who came in the summer to trade their goods with the fishermen of Northern Norway. The Russian Orthodox church demanded fasting (not eating milk and meat) during the many holidays, and consequently stockfish became a very popular product in Russia. The word Pomor means “by the sea” in Russian (Balsvik, Citation1989a, p. 91).

4 While bureising literally means to raise a place to live, I will lean on the translation offered by Lien and Ulvang Larsen (Citation2022).

References

- AMAP. (2021). Arctic Climate Change Update 2021: Key Trends and Impacts. Summary for Policy-makers. Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP). Retrieved from https://www.amap.no/documents/download/6759/inline

- Andersen, S. (2003). Samisk tilhørighet i kyst-og fjordområder. In B. Bjerkli & P. Selle (Eds.), Samer, makt og demokrati (pp. 246–264). Oslo: Gyldendal Norsk Forlag.

- Balsvik, R. R. (1989a). Vardø: Grensepost og fiskevær, 1850-1950 I. Vardø: Vardø Kommune.

- Balsvik, R. R. (1989b). Vardø: Grensepost og fiskevær, 1850-1950 II. Vardø: Vardø Kommune.

- Balsvik, R. R., & Nielsen, J. P. (2008). Forpost mot øst – fra Vardø og Finnmarks historie 1307-2007. Stamsund: Orkana.

- Borgen, L. (2017). Frederik Christian Schübeler’s activities in the Botanical Garden at Tøyen under the slogan “Grow more valuable plants”. Blyttia: Journal of the Norwegian Botanical Society, 75(2), 91–112.

- Botanical and plant physiology encyclopedia. (2019). Vierkratt. Botanisk- og plantefysiologisk leksikon. Retrieved from https://www.mn.uio.no/ibv/tjenester/kunnskap/plantefys/leksikon/v/vierkratt.html

- Braidotti, R. (2022). Posthuman feminism. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Bråthen, K. A. (2017, November 4). Forskeren forteller: Klimaendringene kan føre til en grønn ørken. Retrieved from https://forskning.no/planteverden-forskeren-forteller-klima/forskeren-forteller-klimaendringene-kan-fore-til-en-gronn-orken/312215

- Bråthen, K. A., Gonzalez, V. T., & Yoccoz, N. G. (2018). Gatekeepers to the effects of climate warming? Niche construction restricts plant community changes along a temperature gradient. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics, 30, 71–81. doi:10.1016/j.ppees.2017.06.005

- Bravo, M. (2015). The postcolonial Arctic. Moving Worlds: A Journal of Transcultural Writings, 15(2), 93–111.

- Cypher, R., Bubandt, N., & Andersen, A. O. (Eds.). (2022). Rubber boots methods for the Anthropocene: Doing fieldwork in multispecies worlds. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Friedrich, D. (2021). The quest for fresh vegetables: Stories about the future of Arctic farming. In Rita Sørly, Tony Ghaye, Bård Kårtveit (Eds.), Stories of change and sustainability in the Arctic regions (pp. 193–217). London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003118633

- Grieg, N. (1946). Håbet: Dikt. Oslo: Gyldendal Norsk Forlag (Published Posthumously).

- Hagen, R. B. (2015). Ved porten til helvete: Trolldomsforfølgelse i Finnmark. Oslo: Cappelen Damm.

- Hagen, R. B. (2019). Vardø – Kongens by i Nord. Marinetoktet nordøstover i 1599 – Bakgrunn, forløp og betydning. In Vardø by 230 år. Byen i våre hjerter (pp. 27–43). Vardø: Vardøhus Museumsforening.

- Hamelin, L. E. (1978). Canadian nordicity: It’s your north too. Montréal, Québec: Harvest House.

- Hansen, L. I., & Olsen, B. (2022). Samenes historie fram til 1750 (Vol. 2). Oslo: Cappelen Akademisk Forlag.

- Haraway, D. (2017). Symbiogenesis, sympoiesis, and art science activisms for staying with the trouble. In Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Nils Bubandt, Elaine Gan and Heather Anne Swanson (Eds.), Arts of living on a damaged planet (pp. M25–M50). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Haraway, D. (2019). It matters what stories tell stories; it matters whose stories tell stories. A/b: Auto/Biography Studies, 34(3), 565–575. doi:10.1080/08989575.2019.1664163

- Hastrup, K. (2010). Emotional topographies. The sense of place in the Far North. In James Davis and Dimitrina Spencer (Eds.), Emotions in the field: The psychology and anthropology of fieldwork experience (pp. 191–211). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Johansen, C., Vange, V., & Alm, T. (2010). Tur i natur og kultur Skallelv – Kallijoki. Varanger Museum IKS og Tromsø Museum – Universitetsmuseet.

- Jørgensen, D. T. (2019, September 4). Hvem har det høyeste treet i byen uten trær? Østhavet. Retrieved from https://www.osthavet.no/hvem-har-det-hoyeste-treet-i-byen-uten-traer/

- Jørgensen, K. (2015). The garden – An encounter between bold ideas and harsh nature. In G. Tanguay (Trans.), Hager mot nord: Nytte og nytelse gjennom tre århundrer (pp. 11–31). Stamsund: Orkana.

- Larsen, J. K. (2019). Ruins in reverse. In Andrew Morrison, Janike Kampevold Larsen and Peter Hemmersam (Eds.), Future North: Vardø. Oslo: OCULS at Oslo School of Architecture and Design.

- Larsen, J. K. (2023). Love and Care in Place Development. In L. Cho & M. Jull(Eds.), Design and the Built Environment of the Arctic. London: Routledge.

- Larsen, J. K., & Hemmersam, P. (Eds.). (2018). Future north: The changing Arctic landscapes. London: Routledge.

- Latour, B. (1986). Visualization and cognition: Drawing things together. Knowledge and Society Studies in the Sociology of Culture past and Present, 6(6), 1–40.

- Lien, M. E. (2020). Dreams of prosperity – enactments of growth: The rise and fall of farming in Varanger. Anthropological Journal of European Cultures, 29(1), 42–62. doi:10.3167/ajec.2020.290104

- Lien, M. E., & Ulvang Larsen, C. (2022). Colonization through the plow. Agriculture in Pasvik. In G. B. Ween & M. Lundblad (Eds.), Control: attempting to tame the world (pp. 138–143). Oslo: Pax Forlag.

- Massey, D. (1991). A global sense of place. Marxism Today. Reprinted in T. Barnes & D. Gregory (Eds.), Reading human geography, 1996 (pp. 315–323). London: Arnold.

- Mathews, A. S. (2022). Trees are shape shifters: How cultivation, climate change, and disaster create landscapes. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv2vvsx03

- Meteorologisk institutt (2021). Ny normal i klimaforskningen. Meteorologisk institutt. Retrieved from https://www.met.no/vaer-og-klima/ny-normal-i-klimaforskningen

- NCCS. (2023). Seklima. Observations and weather statistics. Norwegian Centre for Climate Services (NCCS). Retrieved from https://seklima.met.no/observations/

- Petti, A., Hilal, S., & Weizman, E. (2013). Architecture after revolution. London: Sternberg.

- regjeringen.no. (2018, June 4). Urfolk og minoriteter [Tema]. Regjeringen.no; regjeringen.no. Retrieved from https://www.regjeringen.no/no/tema/urfolk-og-minoriteter/id929/

- Sætra, G. (2019). Forventer kongekrabbe ved Svalbard om ti år. Havforskningsinstituttet. Retrieved from https://www.hi.no/hi/nyheter/2019/november/forventer-kongekrabbe-ved-svalbard-om-ti-ar

- Sandberg, S. (2017). Treboka: Fakta og fortellinger om norske trær. Oslo: Gyldendal.

- Schübeler, F. C. (1886). Viridarium norvegicum. Norges Væxtrige: Et Bidrag til Nord-Europas Natur-og Culturhistorie (1ste Bind). Christiania (Oslo): WC Fabritius & Sønner.

- Sheppard, L., & White, M. (2017). Many norths: Spacial practice in a polar territory. New York, NY: Actar D, Inc.

- Støstad, M. N. (2020, November 28). NRK avslører: Slik blir klimaet i Vardø. NRK. Retrieved from https://www.nrk.no/klima/kommune/5404

- Sundet, J. H. (2011). Krabbe til besvær. Framsenteret. Retrieved from https://framsenteret.no/arkiv/krabbe-til-besvaer-4892090-146437/

- Sundet, J. H., & Hoel, A. H. (2016). The Norwegian management of an introduced species: The Arctic red king crab fishery. Marine Policy, 72, 278–284. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2016.04.041

- Tsing, A. L. (2015). The mushroom at the end of the world. On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Tsing, A. L., Mathews, A. S., & Bubandt, N. (2019). Patchy Anthropocene: Landscape structure, multispecies history, and the retooling of anthropology. Current Anthropology, 60(S20), S186–S197. doi:10.1086/703391

- van Dooren, T., Kirksey, E., & Münster, U. (2016). Multispecies studies – cultivating arts of attentiveness. Environmental Humanities, 8(1), 1–23. doi:10.1215/22011919-3527695

- Vardø – gateway to the Northeast Passage. (2023). Hurtigruten. Retrieved from https://global.hurtigruten.com/ports/vardo/

- Visit Vardø. (2023). Visit Vardø. Retrieved from https://www.visitvardo.com

- Vola, J. (2022). HOMUNCULUS Bearing Incorporeal Arcticulations. Rovaniemi: University of Lapland. Retrieved from https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-337-309-9

- Wormdal, B. (2015). Spionbasen: Den ukjente historien om CIA og NSA i Norge. Oslo: Pax Forlag.