Abstract

Over the last 30 years, the global wine sector has undergone substantial shifts both in production and consumption, with significant impacts on the geography of wine and vineyards. The study follows this evolution from a narrative production perspective, underlining the cultural value of wine and the emergence of new territorial imageries linked to terroir. Taking the case of Etna wines, the research aims to cast light on both the local practices of resistance to global competitiveness and the online narratives of consuming both wine and landscape targeted at a global audience. A mixed methodology with a place-based approach is adopted, aimed at exploring critical issues in the context of a relatively new wine-producing region. Findings reveal an active offline and online reterritorialisation, with conflicting identities being glossed over by landscape attributes, which are exploited to embed territory in a glass.

Introduction

Until the late ‘90s, the wine industry was still dominated by Old World wine producers, like France, Spain, and Italy, where highly embedded micro and small family-owned enterprises competed mostly within regionalised operation systems and intra-European trade (Aylward, Citation2005; Aylward & Zanko, Citation2008). Nonetheless, symbolically, since the ‘Judgement of Paris’Footnote1 in 1974, this dominance has been progressively eroded and New World producers like South Africa, California, Chile, and Australia, above all, have emerged from their cottage status. Dramatic changes in oenological and viticulture research, packaging, transportation, and storage were about to ignite a new reconfiguration of the wine industry on a global scale (Anderson, Norman, & Wittwer, Citation2004; Cusmano, Morrison, & Rabellotti, Citation2010). Shifts in wine production have been mirrored in, and more deeply developed by, changing consumption patterns, framing new identities and social differentiations around a new aesthetic of wine (Hisano & Chapman, Citation2020).

In turn, this co-evolution of economic and sociocultural factors has led, nowadays, to reconsider place, identity, and typicality, not only from the perspective of the production and consumption of wine but, overall, from that of the production and consumption of landscapes. The cultural value of wine and its link to terroir are creating niches of value as many globally involved consumers demand quality and the ability to evoke the production territory in a glass, ‘using products and experience to reconnect to places, history, culture, and one another’ (Eades, Arbogast, & Kozlowski, Citation2017, p. 60) as a response to the homogeneity of global production.

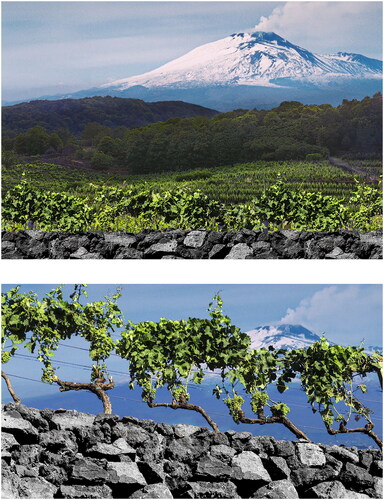

The current paper has been developed within this scenario, taking the case of Etna wines as an example of territorial redefinition of vineyard landscapes due to global-local dynamics and the booming wine sector. This area is historically suited to wine production like many others in Italy, but its specificity lies in vineyards dotting the slopes of one of the most active and highest volcanos in the world, which has also been a UNESCO site since 2013.

The aim of this research is to analyse the evolution of the vineyard landscape in the Etna region in the last 30 years and to assess how new narratives and territorial imaginaries are redefining its territorial identity on a global scale, and mediating globalisation at a local level. In this perspective, food and landscape become ‘imprinted’ within shared cultural meanings (Roe, Citation2016).

Thus, this paper discusses the importance of wine-narrative production in the identity of landscape, and how it has become particularly functional/instrumental for wineries to vehiculate certain imaginaries that encourage experiencing — and consuming — both wine and landscape. In addition to more traditional qualitative ways of analysing narratives — represented in this paper by interviews — the aim is to push forward wine-related research by reading and interpreting digital content production referring to landscape’s identity. The choice of focusing on web content analysis draws on the increasing importance of virtual showcases and marketplaces as means of creating and disseminating content, thus representing both an effective marketing tool and a novel valuable source for analysing narratives linked to global branding and territorial imageries. As a result, the creation/valorisation of Etna landscape imaginary is explored by focusing on wineries’ online narratives, highlighting the values they associate with it and how different identities and visions may be exploited in their branding strategies.

In the next section, an overview of wine culture in terms of global evolution is presented, while in the third section, methods and the study area are described. Section four groups together research findings, which are finally discussed by highlighting how the case study of Etna wines epitomises the extent to which physical and virtual imaginaries driven by wine can mould new landscape identities.

Wine and landscape: a culturally dynamic relationship

In the last decade of the century, New World producers were creating technically faultless and more affordable wines, within a new top-down planning approach, with industry and research bodies strongly linked to government action. This organisational shift had been the driver for the globalisation and ‘democratisation’ of the wine sector, dominated by multinational firms, mass-produced and standardised wine for immediate consumption, blended from multiple regions across the world, with high capital investments and an export orientation (Anderson et al., Citation2004; Cusmano et al., Citation2010). From a ‘production of culture’ perspective, the social construction of a wine-drinking culture has been prompted by new narratives aimed at creating new markets and new consumers (Inglis & Almila, Citation2019), ‘transforming the material into the intellectual, the imaginative, the symbolic, and the aesthetic’ (Ferguson, Citation1998, p. 599). These changes in drinking patterns have been significantly addressed by intensive marketing and empowered by new media technologies since the beginning of the 1980s, forging new cultural meanings and, more generally, ways of life (Arvidsson, Citation2007; Bourdieu, Citation1984; Hisano & Chapman, Citation2020). As the documentary Mondovino (Giraud & Nossiter, Citation2004) clearly represents, this new orientation has been supported by a network of ‘flying winemakers’, biochemists, wine experts, and oenologists, disseminating technical knowledge, ideas, and practices, and promoting a standardised value set in which brand reliability is the main criterion in appreciating wine. As noted by Kornberger (Citation2010), brands are not just corporate enterprises but, most significantly, cultural expressions influencing people’s cognition of the world, their identity, and lifestyles in the modern consumer society. Against this background and throughout the evolution of the wine sector, ‘access to oenology was a key factor in the process of differentiation between the various groups as it enabled the elites to produce a discourse on taste which referred directly to terroir’ (Demossier, Citation2011, p. 701). From this perspective, wine is understood as being produced and consumed in various ways, and, in the process, particular hegemonic and ideological cultural meanings are disseminated and reproduced.

As a consequence, while the ‘80s were characterised by a strictly regulated market and a substantial monopoly situation, within two decades new global players had exceeded the European Union, especially on exports, dropping from 95% in share to 69% during the period 2006–2008 (Pomarici & Sardone, Citation2009). The European policy reform in 2008 attempted to balance internal overproduction with a more liberalised market, capable of stimulating competitiveness with non-EU wine producers. The evolution of consumption patterns was a crucial factor in this shift, specifically regarding the quest for quality and the emergence of a global movement contesting ‘the placelessness of globalised food production’ (Duram & Cawley, Citation2012, p. 17). Resistance to the dominium of corporations and some cultural movements — the Slow Food movement among them — acted as a cultural glue for all those movements claiming the narrative of ‘local food’ (DuPuis, Goodman, & Harrison, Citation2006; Miele & Murdoch, Citation2002) as a synonym for authenticity and security. At the same time, localness refers to both the dimension of space and that of time, so food traditions and typical productions have become the lens through which consumers read and understand the territory (Camaioni, D’Onofrio, Pierantoni, & Sargolini, Citation2016; Fonte, Citation2008).

This growing consumer need for authenticity and traceable products has been driven by a trend towards regional/local differentiation, reinforced by the flourishing of protection of geographic indications and by heritagisation processes at the European level (Gabellieri, Gallia, & Guadagno, Citation2023; Gade, Citation2008). Among others, one of the central concepts in this rising European new rural paradigm is that of terroir, which in the wine world has found its utmost expression, capable of narratively capturing the link between the product and the landscape in which it originated. The terroir includes the physical elements of the vineyard, such as the soil and the microclimate, but also ‘the joys, the heartbreaks, the pride, the sweat, and the frustrations of its history’ (Wilson, Citation1998, pp. 55–56), and the unique human skills and practices passed on from one generation to the next. Far from being a static concept, terroir ‘reflects an ongoing construction of a collective representation of the past and, at the same time, an active social construction of the present’ (Barham, Citation2003, p. 132), thus continually shaping the identity of landscape (Loupa Ramos, Bianchi, Bernardo, & Van Eetvelde, Citation2019; Vaquero Piñeiro, Tedeschi, & Maffi, Citation2022). As a consequence, disentangling the osmotic relationships among terroir, identity, and landscape is crucial to explore whether, and if so how, territorial imageries driven by a local product, such as wine can evolve and shape new landscape imageries. Thus, we draw on Stobbelaar and Pedroli (Citation2011)’s conceptualisation of the differences between spatial and existential identities of landscape: while the first is based on a broad sense of the features by which people recognise landscape, in terms of visual aspects, forms, patterns, and elements, including colours and smells, existential identity refers to a sense of belonging to a specific landscape, to which associations, memories and symbolic meaning are attached. Landscapes are indeed complex representations of evolving mutual and dynamic interactions between stakeholders and the environment, largely influenced by driving forces induced by policies, planning, and land management (Dossche, Rogge, & Van Eetvelde, Citation2016), but also by the role of the physical landscape as a potential ‘identity builder’ for people (Egoz, Citation2015). Along the same lines, as noted by Shannon and Mitchell (Citation2012), the landscape can be socially constructed to satisfy consumers’ desire for authenticity and uniqueness and used in the construction of new identities aimed at reinforcing the economic value of a particular place (Riviezzo, Garofano, Granata, & Kakavand, Citation2017). Indeed, wine production, sales, and consumption are constantly affected by attempts to manipulate this identity (Harvey, Frost, & White, Citation2014). Against this background, as noted by Tiefenbacher (Citation2013, p. 3), ‘imagery and the textual language […] create templates for conceptualisation of styles, brands, regions, and flavour experience’. In so doing, they contribute to shaping not only the image of wine as a cultural object but also its place of origin, by reinforcing and representing its assets in a cohesive manner (Grenni, Horlings, & Soini, Citation2020).

New media technologies are transforming the relationship between producers and consumers in the wine industry across new regions. Indeed, websites now serve as key platforms for sharing information about companies and their products globally (Buhalis & Law, Citation2008; Sun, Fong, Law, & He, Citation2017). More specifically, wine consumers demand information concerning the characteristics of the products, especially as regards the place of origin (Dimara & Skuras, Citation2005; Marzo-Navarro & Pedraja-Iglesias, Citation2021; Stricker, Mueller, & Sumner, Citation2007), which has become of central importance in purchase decision-making (Atkin & Johnson, Citation2010; Johnson & Bruwer, Citation2007; Lockshin, Jarvis, d’Hauteville, & Perrouty, Citation2006; Moulard, Babin, & Griffin, Citation2015). Moreover, images of landscapes can be a powerful marketing tool in the wine industry (Demossier, Citation2011; Orth, Wolf, & Dodd, Citation2005). Conversely, the food branding process may indeed have a strong impact on the reconstruction of place identity. From a semiotic perspective, as underlined by Mangiapane and Puca (Citation2023, p. 181), ‘food becomes a language able to describe and commercially position a place, up to rebuilding or rebranding it as a destination’. Co-branding food and landscape means associating a material product with a place that is assumed to have attributes, generating benefits for the image of the former (Messely, Dessein, & Rogge, Citation2015). This strategy is not without criticism, requiring a selection of attributes and symbolic values that are assumed to add value to the product (Boisen, Terlouw, & Van Gorp, Citation2011). This implies that other place-specific attributes are left out in favour of a coherent and forceful system of identity construction (Porter, Citation2016), marginalising alternative heterogeneous identities and narratives.

Data source and methods

This research was conducted following a place-based approach (Sonnino, Marsden, & Moragues-Faus, Citation2016), featuring the mutual relationship between wine production and its territory. Firstly, a review of the past and present academic literature was conducted to consider the evolution of narratives on wine-related interwoven aspects of identity, heritage, landscape, and scale dynamics. A desk analysis was then carried out on secondary documents, such as newspaper articles, wine-related websites, and technical reports, to support and give context to the study.

Primary data were collected through 34 semi-structured interviews conducted between April 2023 and January 2024 () with local and non-local (from other Sicilian areas or Italian regions) wine producers/winery managers, and four in-depth interviews with key informants selected through a snowballing approach.

Table 1. Overview of interviews.

Moreover, a software-based content analysis was carried out of the English version of n. = 77 Etna wineries’ websites to scrutinise what kind of place imagery was mobilised in digital channels.

The main objective of this twofold method of analysis was to deconstruct both the imageries that wine producers/managers aim to convey outside through the digital branding and selling channels, targeted at the global audience, and their own landscape perceptions of ‘from the inside’.

In particular, for the website content analysis, the analytical tool NVivo 12 software was used to collect — through NCapture, the extension of NVivo for browsers — and analyse narratives to cast light on the territorial features that Etna wineries link to Etna terroir with the result of influencing the landscape perception not only of wine consumers, but also — more broadly — of landscape consumers.

Only 77 out of the 155 wineries’ websites officially belonging to the Consortium for the Protection of Origin of Etna Wines have an English version of their site, 36 have only the Italian version and the others were unavailable or unsuitable.Footnote2 Through NVivo Capture we analysed contents retrieved from the ‘territory/terroir’ and ‘who we are’ website sections,Footnote3 removing the product pages and the contact page from the capture.

Case study area: Etna volcano and landscape between wine history and new identities

Mount Etna is the highest and most active volcano in Europe. Since 1987, Mount Etna has been a protected natural area, and in June 2013 it became part of the UNESCO World Heritage List. Every year, thousands of tourists visit to admire its natural beauty and cultural heritage, shaped by the historical interaction between local communities and their environment. Over centuries, literature and art have celebrated this iconic landscape, which has been profoundly marked by terraced agriculture and rural architecture like warehouses and cellars. Viticulture in the area of Etna has ancient origins, documented since the XVII century B.C. by the Odyssey and confirmed by the discovery of fossil grape vines. Viticulture was further developed by Greeks and Romans, while during the Islamic dominance, viticulture was almost suspended and carried on only inside monasteries. Viticulture resisted and, as further proof of its importance, in 1435 the Guild of the Vigneri was founded, a wine-growers association whose main aim was to initiate the new generations into the knowledge of how to grow and produce wine on Mount Etna. At the end of the XVIII century, the area accounted for almost 90,000 hectares under viticulture, with wine exported all over Europe from the near Riposto commercial port. Thanks to its alcoholicity and acidity, this wine could resist navigation and was perfectly suited as a blending wine. As noted by Dandolo (Citation2019), in fact, quantity was not equally echoed by quality: several production problems, including land organisation and planning, a lack of investment in modernisation, and above all, very little focus on human capital, have been critical to the realisation of good-quality wines over the centuries.

The phylloxera invasion in the early 1900s and other volcanic eruptions led to a consistent diminishing of the viticultural area and production. Competitiveness in international markets and the rolling back of forms of national/European protection have deepened already existing phenomena of rural abandonment. In particular, since the ‘70s, changes in the structure and scale of wine markets and endogenous factors have led Etna viticulture into a significant decline (Foti & Timpanaro, Citation2010). Mechanisation and the use of chemicals have been feasible within cultivated areas of a certain extension and planting layout and form, whereas the traditional Etna terracing landscape, with its alberello farming system, wasn’t suitable for such changes (). Furthermore, the area is historically characterised by a significant fragmentation of production units, with limited production and relevant diseconomies of scale. Moreover, investments in the modernisation of vinification techniques and in substituting local grape varietals with more internationally known ones were too high for small-business management.

Finally, and more generally, there has been a sustained shift towards urbanisation, with changes in land use and a wider push away from agriculture by newly educated generations. Etna viticulture, historically embedded in its volcanic ‘impending permacrisis’ (Petino & Privitera, Citation2023) and developed in balance with natural elements, was abandoned or replaced with more profitable productions, like lemon orchards. Consequently, the declining wine production has been coupled with the abandonment of associated features like ‘towers’ and cellars, viewing the Etna landscape as traditional artefacts and so, inexorably, a great cultural heritage has been lost (Riguccio, Russo, Scandurra, & Tomaselli, Citation2015).

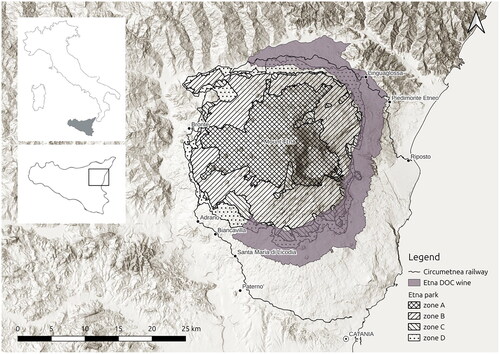

Today, Etna viticulture is again on the rise, and in 2018 the Consortium for the Protection of Etna Wines was legally established by the National Ministry of Agriculture, given the significance of the booming local wine sector, with an increasing number of producers and products ().

Table 2. Etna PDO area and production, 2011–2022.

For the same reason, a map of the PDO area was produced in 2022 (), with a definition of the slopes particularly functional for the terroir’s narrative production.

Results

In the Sicilian wine sector, the strategy to compete in an increasingly wide and globalised market has often been sought in the establishment of the Controlled Designation of Origin (DOC). Although Etna Doc was the first regional attempt to overcome local constraints in quality winemaking, the quantity of bottled wine and the scarce cooperation of Etna wine producers were not enough to sustain it. Symbolically, as regards cellars — ‘the beating heart of the human-territory relationship’ (Interview #1) — modern refrigeration techniques and the strict hygiene regulation required for modern winemaking processes have left these spaces obsolete (Fuentes, Gallego, García, & Ayuga, Citation2010).

Indeed, resistance struggles are still very much present in the narratives of local producers: ‘There wasn’t an idea anymore. The farmland was a place of struggle, to stay in for duty, which of course younger generations refused. I’ve always heard about suffering, struggling and difficulties with selling grapes… grapes rotting on the plants’ (Interview #5). Skilled workers also moved to other, more remunerative industrial sectors or left the island for other wine-producing regions, both in Italy and outside (Interview #20). ‘When I came here 20 years ago […] there were only old people holding onto their souls and vines with their teeth, sometimes selling their piece of land’ (Interview #6).

When the ‘90s brought a new rural paradigm, based on quality and typicity, a few local entrepreneurs initially began to experiment with new lines of production from indigenous grape varietals with innovations and a shift in quality. This process was not without obstacles and critical aspects, especially given the geographical variety of landscape and administrative constraints (Interview #6).

However, in the first decade of the new millennium, outsiders from other Italian wine-growing areas and all over Europe started producing wines on the slopes of the volcano, connecting the local vines to the global wine market. Furthermore, local expats came back to their abandoned and inherited lands to take advantage of this new phenomenon (Interview #11).

In this period, in line with the evolution of the concept of territory at the European level, territorial branding has reinforced the identity of both wine and landscape. Tradition is deeply rooted, with ancestral rituals still resisting the burdens of global rules, the widespread alberello farming system, and several other rural artefacts being renovated. In recent years, some historical cellars have been restored for touristic services, hospitality, and also cultural activities, and they have also been awarded architectural prizes due to virtuous regeneration interventions. Respect for traditions and landscape is also due to the fact that the PDO statute was already in law long before the wine revival, tying wine-growing procedures, productivity, and wine composition to the Etna tradition.

At the same time, production innovations and branding strategies have brought benefits to wine producers, wineries, and also to the whole industry, increasing the occupation and revenues of hotels, restaurants, and satellite activities, even if they are firmly concentrated in the hands of 10–12 well-organised and export-oriented wineries, triggering down to the rest (Interview #7). The success of Etna wines resides in the branding process, which started with the arrival of non-local entrepreneurs, more connected to the global market and capable of capturing local potential and branding it. As a result, some of the best-known local wineries have witnessed the arrival of highly branded made-in-Italy investors, contributing to the rise of a global product. Alongside this, as some interviewees pointed out (Interviews #19, #23, #29), there has been a process of homogenisation in taste, due to the effect of the ‘flying winemakers’, namely ‘those 3/4 famous oenologists from all over Italy who have been working for many of the wineries, especially the big and medium ones’. As underlined by another wine producer, people come to Etna from all over the world driven by passion, but ‘they improvise, and 80% of them don’t have a cellar on their own and do not work the vines in person. So, this passion is confused and misguided’ (Interview #6).

From a very spatial point of view, of the three volcano slopes involved today in wine production, non-locals have settled mostly in the northern area, which is considerably less urbanised than the south-east, where many vineyards had been converted to other productions, abandoned, and finally absorbed by the expanding city of Catania. This dynamic is fully represented by the composition of producers in the Consortium, with more than 70% of PDO producers having settled in the north of Mount Etna. Indeed, the northern slope ‘plays the role as a forerunner and growth marketer of Etna wines’ (Interview #25), while ‘the southern — where viticultural tradition was born and firstly developed due to the proximity to the city — has been significantly impacted by urban dynamics and the development of other economic sectors, that of the construction industry above all’ (Interview #18). As noted by other producers, there has been an ‘inability to make indigenous this phenomenon’ (Interviews #10 and #5). A variety of visions is also at stake, not only in the way wines are conceived but also in the different dialectical relationship between humans and nature. ‘Nowadays, I see devastation […] such a fine territory with its historical terraces being razed to the ground for productivism. There is no respect […] for every business born, a piece of Etna dies’ (Interview #8). In contrast, another (non-local) producer states that ‘you can’t produce if you don’t modify the landscape. And in any case, you won’t notice any difference in taste’ (Interview #14).

Furthermore, the relation to territory results in ambivalent responses among different groups: ‘You have to be a territory builder and guardian, you need to know where it all comes from and to disseminate your knowledge, otherwise you and the whole landscape are lost’ (Interview #1). Others finally describe struggles in the everyday experiencing of landscape, such as illegal dumping and mob racketeering (Interview #11).

To conclude, the booming of Etna wines has been reported in many online documents, including newspaper and magazine articles, and the Etna landscape is often described as ‘Etnashire’ or ‘the Bourgogne of the Mediterranean’. Also, some local producers claim the ‘colonisation’(Interviews #10 and #16) of their ‘muntagna’ (mountain), not always being respectful of the landscape’s uniqueness and millenary traditions and reputation.

Narratives of landscape and terroir

This strand of research was conducted with the aim of casting light on the attributes that Etna wineries link to Etna terroir and can influence the perception of place not only of wine consumers but also — more broadly — of online landscape consumers.

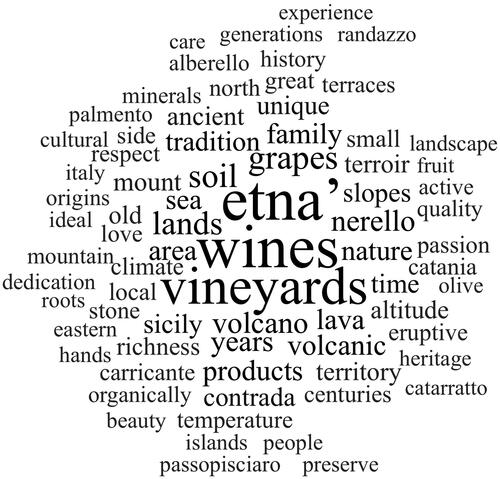

The word cloud shown in illustrates the most frequent 75 words in the narratives presented by wineries’ websites.

The most outstanding words in terms of weighted percentage are, of course, ‘Etna’, the name of the volcano but also the name of the wines, which are at the same percentage (2.31%), followed by ‘vineyards’ and ‘grapes’ (1.87 and 0.84%). Immediately after, the words ‘soil’ (0.81%) and ‘lands’ (0.77%) along with similar words are taken into consideration. ‘Volcano’ counts for 0.61%, but NVivo distinguishes this word from ‘volcanic’ (0.51%), which reaches the same percentage in this research.

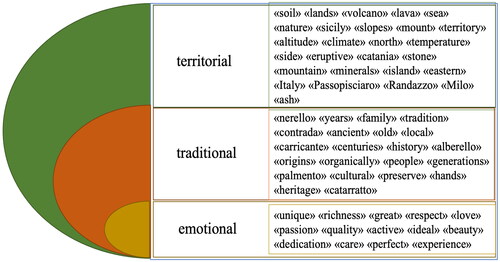

Excluding the first four most frequent words, which are redundant for the scope, all these words have been grouped into three narrative subsystems of attributes, defined as emotional, traditional, and territorial, to highlight different aspects that the website communicates in respect of their wine-growing and making processes (). The first groups together all the attributes that represent the emotional and symbolic dimensions of terroir. The traditional subsystem is defined by all the features that are expressions of the local traditions of wine growing and making and that characterise know-how. Finally, the territorial subsystem represents a set of context descriptors, either natural or topographical.

In percentage terms, these groups attain different figures, underlining an emphasis on territorial attributes (53%), followed by traditional (32%) and emotional (15%) ones.

The emerging territorial dimension is particularly interesting, in terms of both volcanic attributes and topography. Indeed, the physical variety of the environment is well represented by terms associated with soil, climate, sea proximity, slopes, altitude, temperature, and the particular mineral composition of the lava terrain. From a topographic point of view, apart from broader locations, such as ‘Italy’ and ‘Sicily’, the northern slope is mentioned the most, with Passopisciaro and Randazzo districts referred to more than others, while the eastern side, including Milo village, was mentioned less, and there was no significant relevance of the southern slope.

At the same time, traditional elements are very well narrated. What in the past has been critical to the industrial development of a traditional rural sector is now leveraged for the production and consumption of the landscape. Historical lava stone terraces and alberello farming, which were once obstacles for machinery and productivity, have become typical of the local landscape and praised for bringing different notes to vineyards. Nerello mascalese and Catarratto — indigenous grape varieties that at one time were about to be definitively abandoned — are now viewed as distinctive expressions of Etna terroir, and natural and artefact elements of traditional processing are narrated as the landscape to experience.

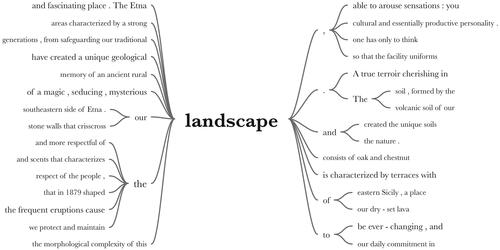

With a further focus on the word ‘landscape’ (), a whole system of emotionally related attributes and territorial imaginaries becomes apparent.

Etna landscape is ‘a fascinating place’ with a ‘cultural personality’ where ‘traditional memories of the ancient rural’ contribute to a ‘magic, seducing, mysterious’ landscape, and where the ‘scents’ and ‘sensations’ of nature and the ‘morphological complexity’ are ‘respected’ and ‘protected’ through ‘safeguarding tradition’. It is ‘a unique geological’ landscape where ‘generations’ have created ‘terraces’ from lava and a ‘true terroir’ (see ).

Finally, many websites and several producers have questioned the statement that ‘Etna is an island within an island’, entailing the extreme variability of micro-climates that characterise this wine-growing area. Indeed elevation, sun exposure, and wind streams are significantly diverse and split the wine territory into three distinct slopes, with different terroir distinctiveness of the production area: north, east, and south. Nevertheless, the lava soil is the mark of this terroir, not only because of the eruptive history but also because it visually represents energy and power.

Discussion and conclusions

In recent decades, the Etna wine sector has witnessed a tremendous increase in both the number of producers and in the area of production. The ‘quality turn’ has been activated locally to contain the spreading deterritorialisation, due to changes in the production and consumption of wine on various geographical scales. Competitiveness and the restyling of old-fashioned wines have followed the terroir concept, linking mere information on the label to more intense online narratives, seeking to capture the place in a glass. In the case of Etna, this action has been pursued by several non-local producers, forging an active reterritorialisation that has brought benefits to all actors at the local level, particularly to those settled on the northern slope.

While the everyday consumption of landscape results in counternarratives of past and present struggles of deterritorialisation and reterritorialisation due to local/global dynamics, conflicting powers are glossed over by new landscape narratives, which tend to highlight the role of territorial attributes of terroir, with lava soil emerging as the most distinctive and most recognisable feature of Etna. Territorial imaginary linked to the permanent activity and power of Mount Etna is very characterising and has adopted the role of a flagship, or — as other scholars have defined — of an ‘identity builder’. Indeed, Etna wines’ terroir has been produced around those spatial features recalling Mount Etna as a symbol, undermining its contested dynamics and translating them into positive elements of identity, enriching the cultural dimensions of wine crafting and the experience of the Etna landscape. Beyond safeguarding cultural heritage, the narrative of Etna wine enhances the recognition of the landscape’s identity, serving as a means of geographical distinction.

The landscape features themselves — i.e. the terraces, farming system, and land pulverisation — did not allow for consistent investments in the past due to high fixed costs (property of wineries, communication, etc.), but online narratives tend to convert these limitations into valuable elements of typicity, so that local grape varieties emerge now as ‘authentic’, terraces as ‘heroic viticulture’, and land fragmentation is now described as micro-distinctiveness on wine labels. Furthermore, it is essential to recognise the importance of landscape’s identity in shaping consumers’ perceptions and aspirations in terms of their wine preference. Narrative practices resonate with the quest for landscape identity as a cultural product to consume among consumers, tourists, and residents, providing a sense of authenticity and forging landscape imageries that may be mobilised through online communication. The conceptual framework provided by Stobbelaar and Pedroli (Citation2011) reveals how visual aspects of Etna — or what in this contribution are defined as ‘territorial’ attributes — have an extraordinary impact in marking the landscape and reinforcing the experience of it, and its cultural and economic value.

This paper has highlighted how narratives produced through online connections are focused not only on products to consume globally but even more so on landscapes to experience. Distinctive natural features are described as ‘embedded’ in the glass to support consumers in reconnecting to places of production, giving sense to incorporating the materiality of wine as a cultural product. In the case study presented, online narratives tend to represent Etna mainly in a univocal manner, underlining the evocative power of the volcano and hiding critical aspects, such as the homogenisation of both wine and its identity.

This research has limitations in terms of both scope and methodology. Further research should take into account, among other things, contested power relations over land values and changes in land use, sustainability trends, and the financialisation (i.e. mergers and acquisitions) of wineries, as well as the enlargement of the area of protection of origin. Methodologically, interviews were conducted with a restricted number of representatives, and the use of NVivo software has its limitations due to the use of language and technical obstacles to capturing all of the web pages.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank the editors and reviewers for their invaluable help in refining this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

N/A.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Donatella Privitera

Donatella Privitera is a full Professor of Geography at the University of Catania, Italy. She attended an Executive Master in Agri-Business at the Catholic University of Milan, Italy. At present, she is teaching economic geography and its implications for tourism and regional development. Research and publication interests include tourism geography; sustainable cities; green economy; food tourism; and transport geography.

Teresa Graziano

Teresa Graziano (PhD) is an Associate professor of Economic and Political Geography at the Department of Agriculture, Food and Environment of the University of Catania. She was a visiting fellow at the Royal Holloway, University of London, the University of Barcelona, and the Fondation Maison Sciences de l’Homme of Paris, where she has been an Associate Research Director since 2021. She is a regional trustee of the Italian Geographical Society. Her main research interests are focused on urban and tourism geography, particularly on gentrification, and digital geography (the role of smart technologies in shaping new territorial imageries).

Enrica Polizzi di Sorrentino

Enrica Polizzi di Sorrentino is a Research Fellow at the Department of Educational Sciences at the University of Catania (Italy). She holds a PhD in Economic Geography, and she has been a visiting scholar at Northeastern University (Boston, MA) and San Diego State University (San Diego, CA). Her research interests focus particularly on food studies, but also include urban regeneration, social innovation, and intra-European cooperation. For many years she has been working in the private sector as a territorial expert in shared value projects within public/private partnerships.

Notes

1 The ‘Judgement of Paris’ was a wine competition organised in Paris in 1976 where a blind tasting of red wines surprisingly rated a Californian wine higher than a French one, marking symbolically the end of the dominance of the Old-World wines as the world’s best.

2 Some wineries have no website. Others were not functioning or under construction at the time of the research, or did not have any significant information due to the fact that the wineries are mainly from other territories and represent other terroirs.

3 Sometimes these pages used different terms in their headings, such as ‘terroir’ or ‘vineyards’ or ‘family’ or ‘about’.

References

- Anderson, K., Norman, D., & Wittwer, G. (2004). The world’s wine markets—The global picture. In K. Anderson (Eds.), The world’s wine markets: Globalization at work (pp. 14–55). Cheltenham, UK: EEElgar.

- Arvidsson, A. (2007). The logic of the brand. Quaderni Del Dipartimento Di Sociologia e Ricerca Sociale, 36, 7–32.

- Atkin, T., & Johnson, R. (2010). Appellation as an indicator of quality. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 22(1), 42–61. doi:10.1108/17511061011035198

- Aylward, D. (2005). Global landscapes: A speculative assessment of emerging organizational structures within the international wine industry. Prometheus, 23(4), 421–436. doi:10.1080/08109020500350260

- Aylward, D., & Zanko, M. (2008). Reconfigured domains: Alternative pathways for the international wine industry. International Journal of Technology, Policy and Management, 8(2), 148–166. doi:10.1504/IJTPM.2008.017217

- Barham, E. (2003). Translating terroir: The global challenge of French AOC labeling. Journal of Rural Studies, 19(1), 127–138. doi:10.1016/S0743-0167(02)00052-9

- Boisen, M., Terlouw, K., & Van Gorp, B. (2011). The selective nature of place branding and the layering of spatial identities. Journal of Place Management and Development, 4(2), 135–147. doi:10.1108/17538331111153151

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Buhalis, D., & Law, R. (2008). Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet—The state of eTourism research. Tourism Management, 29(4), 609–623. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2008.01.005

- Camaioni, C., D’Onofrio, R., Pierantoni, I., & Sargolini, M. (2016). Vineyard landscapes in Italy: Cases of territorial requalification and governance strategies. Landscape Research, 41(7), 714–729. doi:10.1080/01426397.2016.1212323

- Cusmano, L., Morrison, A., & Rabellotti, R. (2010). Catching up trajectories in the wine sector: A comparative study of Chile, Italy, and South Africa. World Development, 38(11), 1588–1602. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.05.002

- Dandolo, F. (2019). Quantity is not quality: Expansion and limits of wine-producing in Sicily. In S. A. Conca Messina, S. Le Bràs, P. Tedeschi, & M. Vaquero Piñeiro (Eds.), A history of wine in Europe, 19th to 20th centuries. Volume II. Markets, trade and regulation of quality (pp. 47–66). London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-27794-9

- Demossier, M. (2011). Beyond terroir: Territorial construction, hegemonic discourses, and French wine culture. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 17(4), 685–705. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2011.01714.x

- Dimara, E., & Skuras, D. (2005). Consumer demand for informative labelling of quality food and drink products: A European Union case study. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 22(2), 90–100. doi:10.1108/07363760510589253

- Dossche, R., Rogge, E., & Van Eetvelde, V. (2016). Detecting people’s and landscape’s identity in a changing mountain landscape. An example from the northern Apennines. Landscape Research, 41(8), 934–949. doi:10.1080/01426397.2016.1187266

- DuPuis, E. M., Goodman, D., & Harrison, J. (2006). Just values or just value? Remaking the local in agro-food studies. Research in Rural Sociology and Development, 12, 241–268. doi:10.1016/S1057-1922(06)12010-7

- Duram, L., & Cawley, M. (2012). Irish chefs and restaurants in the geography of “local” food value chains. The Open Geography Journal, 5(1), 16–25.

- Eades, D., Arbogast, D., & Kozlowski, J. (2017). Life on the “beer frontier”: A case study of craft beer and tourism in West Virginia. Craft Beverages and Tourism, 1, 57–74. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-49852-2_5

- Egoz, S. (2015). Landscape and identity. Beyond a geography of one place. In P. Howard, I. Thompson, E. Waterton, & M. Atha (Eds.), The Routledge companion to landscape studies. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203096925.ch24

- Ferguson, P. (1998). A cultural field in the making: Gastronomy in 19th-century France. American Journal of Sociology, 104(3), 597–641. doi:10.1086/210082

- Fonte, M. (2008). Knowledge, food and place. A way of producing, a way of knowing. Sociologia Ruralis, 48(3), 200–222. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9523.2008.00462.x

- Foti, V. T., & Timpanaro, G. (2010). Evaluating the potential development of Etna wine-growing through an historical analysis of production costs. III Congresso Internazionale Sulla Viticultura Di Montagna.

- Fuentes, J. M., Gallego, E., García, A. I., & Ayuga, F. (2010). New uses for old traditional farm buildings: The case of the underground wine cellars in Spain. Land Use Policy, 27(3), 738–748. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2009.10.002

- Gabellieri, N., Gallia, A., & Guadagno, E. (2023). Enogeografie. Itinerari geostorici e geografici dei paesaggi vitati, tra pianificazione e tutela ambientale. Roma: Società Geografica Italiana.

- Gade, D. W. (2008). Tradition, territory, and terroir in French viniculture: Cassis, France, and Appellation Contrôlée. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 94(4), 848–867. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.2004.00438.x

- Giraud, E., & Nossiter, J. (2004). Mondovino. Paris: Goatworks & Les Films de la Croisade.

- Grenni, S., Horlings, L. G., & Soini, K. (2020). Linking spatial planning and place branding strategies through cultural narratives in places. European Planning Studies, 28(7), 1355–1374. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1701292

- Harvey, M., Frost, W., & White, L. (2014). Exploring wine and identity. In M. Harvey, L. White, & W. Frost (Eds.), Wine and identity. Branding, heritage, terroir (pp. 1–15). London and New York: Routledge.

- Hisano, A., & Chapman, N. G. (2020). Τhe ‘wine revolution’ in the United States, 1960–1980: Narratives and category creation. Business History, 65(8), 1313–1340. doi:10.1080/00076791.2020.1862794

- Inglis, D., & Almila, A. (2019). The globalization of wine. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Johnson, R., & Bruwer, J. (2007). Regional brand image and perceived wine quality: The consumer perspective. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 19(4), 276–297. doi:10.1108/17511060710837427

- Kornberger, M. (2010). Brand society: How brands transform management and lifestyle. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lockshin, L., Jarvis, W., d’Hauteville, F., & Perrouty, J. P. (2006). Using simulations from discrete choice experiments to measure consumer sensitivity to brand, region, price, and awards in wine choice. Food Quality and Preference, 17(3–4), 166–178. doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2005.03.009

- Loupa Ramos, I., Bianchi, P., Bernardo, F., & Van Eetvelde, V. (2019). What matters to people? Exploring contents of landscape identity at the local scale. Landscape Research, 44(3), 320–336. doi:10.1080/01426397.2019.1579901

- Mangiapane, F., & Puca, D. (2023). The intimate relationship between food and place branding: A cultural semiotic approach. In G. Rossolatos (Ed.), Advances in brand semiotics & discurse analysis (pp. 179–202). Wilmington, DE: Vernon Press.

- Marzo-Navarro, M., & Pedraja-Iglesias, M. (2021). Use of a winery’s website for wine tourism development: Rioja. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 33(4), 523–544. doi:10.1108/IJWBR-03-2020-0008

- Messely, L., Dessein, J., & Rogge, E. (2015). Behind the scenes of place branding: Unraveling the selective nature of regional branding. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 106(3), 291–306. doi:10.1111/tesg.12099

- Miele, M., & Murdoch, J. (2002). The practical aesthetics of traditional cuisines: Slow food in Tuscany. Sociologia Ruralis, 42(4), 312–328. doi:10.1111/1467-9523.00219

- Moulard, J., Babin, B. J., & Griffin, M. (2015). How aspects of a wine’s place affect consumers’ authenticity perceptions and purchase intentions: The role of country of origin and technical terroir. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 27(1), 61–78. doi:10.1108/IJWBR-01-2014-0002

- Orth, U. R., Wolf, M. M. G., & Dodd, T. H. (2005). Dimensions of wine region equity and their impact on consumer preferences. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 14(2), 88–97. doi:10.1108/10610420510592563

- Petino, G., & Privitera, D. (2023). Uncovering the local foodscapes. Exploring the Etna volcano case study, Italy. AIMS Geosciences, 9(2), 392–408. doi:10.3934/geosci.2023021

- Pomarici, E., & Sardone, R. (2009). (Eds.). La nuova OCM vino. La difficile transizione verso una strategia di comparto. Roma: Inea.

- Porter, N. (2016). Landscape and branding. The promotion and production of place. Research in landscape and environmental design. London: Routledge.

- Riguccio, L., Russo, P., Scandurra, G., & Tomaselli, G. (2015). Cultural landscape: Stone towers on Mount Etna. Landscape Research, 40(3), 294–317. doi:10.1080/01426397.2013.829809

- Riviezzo, A., Garofano, A., Granata, J., & Kakavand, S. (2017). Using terroir to exploit local identity and cultural heritage in marketing strategies: An exploratory study among Italian and French wine producers. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 13(2), 136–149. doi:10.1057/s41254-016-0036-4

- Roe, M. (2016). Editorial: Food and landscape. Landscape Research, 41(7), 709–713. doi:10.1080/01426397.2016.1226016

- Shannon, M., & Mitchell, C. J. A. (2012). Deconstructing place identity? Impacts of a “Racino” on Elora, Ontario, Canada. Journal of Rural Studies, 28(1), 38–48. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2011.07.003

- Sonnino, R., Marsden, T., & Moragues-Faus, A. (2016). Relationalities and convergences in food security narratives: Towards a place-based approach. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 41(4), 477–489. doi:10.1111/tran.12137

- Stobbelaar, D. J., & Pedroli, B. (2011). Perspectives on landscape identity: A conceptual challenge. Landscape Research, 36(3), 321–339. doi:10.1080/01426397.2011.564860

- Stricker, S., Mueller, R. A. E., & Sumner, D. A. (2007). Marketing wine on the web. Choices. The Magazine of Food, Farm, and Resource Issues, 22(1), 31–34. doi:10.2307/choices.22.1.0031

- Sun, S., Fong, D. K. C., Law, R., & He, S. (2017). An updated comprehensive review of website evaluation studies in hospitality and tourism. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(1), 355–373. doi:10.1108/IJCHM-12-2015-0736

- Tiefenbacher, J. P. (2013). Themes of U.S. wine advertising and the use of geography and place to market wine. EchoGéo, 23, 1–23. doi:10.4000/echogeo.13378

- Vaquero Piñeiro, M., Tedeschi, P., & Maffi, L. (2022). A history of Italian wine: Culture, economics, and environment in the nineteenth through twenty-first centuries. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-06097-7

- Wilson, J. E. (1998). Terroir: The role if geology, climate and culture in the making of French wines. London: Mitchell Beazley.