Abstract

Nature-based winter sports are often framed as a solution to the tension between people’s desire for pristine snowy landscapes and their effects on that environment. Low-impact activities such as ski touring and cross-country skiing allow outdoor enthusiasts to visit remote and mountainous locations without the need for hard infrastructure of ski resorts, leaving no permanent marks in the landscape. Yet their growing popularity raises a dilemma about negative effects, especially on wildlife conservation areas. We use the tracks and traces left behind by people as well as animals in Northern Europe and the Alps as a nexus through which to explore how humans and non-humans interact, ignore or avoid each other. Often imagined as ephemeral activities, we argue that the cumulative impacts of nature-based winter sports have significant consequences for wildlife and the way we aim to protect it long after its traces in the snow have disappeared.

Introduction

Thick snowfall turns the landscape a uniform white, glosses over shapes, swallows all sound. While time seems to pause, the forest is still alive, and the activity of wild animals becomes ever more visible through their footprints, footprints that cross paths with tracks from human outdoor enthusiasts who enjoy the winter landscape, often on skis. Traces in snow render human-animal use of the same space perceptible. But snow is also intrinsically fleeting. It does not last, is blown over, melts away—and with it the tracks that it magnified. Often imagined as low-impact, ephemeral activities, we argue that alternative, nature-based winter sports that take place off-trail, outside of established infrastructure, such as ski touring (or backcountry skiing), snowshoeing and snowmobile driving, have consequences for wildlife even after the tracks in snow have disappeared.

Our own observations as well as academic literature on outdoor leisure activities show that the ‘nature’ in nature-based sports is largely uninhabited—or in hibernation (Stoddart, Citation2012, p. 93). There is very little academic work on the intersection of alternative winter sports and wildlife (Arlettaz et al, Citation2013; Cremer-Schulte et al., Citation2017; Neumann et al., Citation2010). Tourism studies tend to either focus on motivations or practices of nature-based sports in the snow (Abegg et al., Citation2019; Landauer et al., Citation2009; Perrin-Malterre & Chanteloup, Citation2018; Roult et al., Citation2017). Biologists or conservation sciences have studied the effects of outdoor activities on wildlife more generally (Gruas et al., Citation2020; Taylor & Knight, Citation2003; Zeidenitz et al., Citation2007). The more obvious impacts of built ski resorts have also attracted attention across disciplines (cf. Nellemann et al., Citation2000; Rolando et al., Citation2013; Sato et al., Citation2013). Whilst nature-based winter sports are often heralded as green and environmentally friendly alternatives to the big ski circus, as described by the sociologist Mark Stoddart (Citation2012), we have identified the need to shed light on more unforeseen consequences of nature-based winter activities and ethnographically tease out people’s practices and views in relation to wildlife. By such post-anthropocentric theorising (Hamilton & Taylor, Citation2017), this study aims to critically challenge the humanist perspective of tourism studies.

Biologists around Léna Gruas (Citation2020), for example, found by way of a literature review that outdoor recreationists with a better knowledge of wildlife displayed a lesser acceptance of themselves as being a disturbance to the environment and wild animals. Moreover, they tended to follow management instructions less thoroughly since they perceive themselves to know better (cf. Perrin-Malterre & Chanteloup, Citation2018, p. 9; Taylor & Knight, Citation2003, p. 961)—unfortunately, only very few studies (6%) in the sample regarded nature-based winter sports. To fill this research gap, we ask: What kind of impact do practitioners have on the landscape and the wildlife they share these spaces with? Remote ecosystems are vulnerable environments, even more so in winter, where wild animals need to carefully balance their energy expenditures. Do even these nature-based outdoor activities have negative effects, especially on wildlife and wilderness conservation areas? If so, does this highlight a growing need for protective zones, or seasonally adjusted regulations for sensitive areas?

Using three European case studies we highlight the ways in which making as well as reading ephemeral tracks in the snow affects recreationists’ experience of a seemingly (un)inhibited nature. The first case study examines tensions between the pleasure of ski touring in the German Alps and local conservation efforts to protect wildlife. The story is one of wilful ignorance, skiers negating their intrusion into black grouse livelihood, and preferred avoidance, of legislators and activists advocating no-go zones for humans. The second example explores how winter sports are growing in popularity in the remote arctic landscapes of Northern Sweden and Finland and how such activities may require shifts in protected area legislation. The last case study looks into cross-country skiing at Lahemaa National Park in Estonia. Here, the focus lies on human and animal tracks in the snow, which serve as tangible evidence of their existence, and explores how these interactions contribute to the formation of fresh perspectives on the national park. These three cases, based in very different geographical contexts, show how ephemeral tracks and traces in the snow indicate cohabitation and humans’ more or less alert engagement with wildlife. The conclusion emphasises the importance of increasing awareness about protected areas in order to make nature-based leisure activities more sustainable for all species concerned.

Crossing paths

As ethnographers, we pay close attention to our protagonists’ views and practices of world-making. To approach interspecies entanglements as ‘actual, material relations between different living species’ and how they ‘are related to ecological and political outcomes’ (Youatt Citation2016, 216), all three of us carried out months of fieldwork in respective areas in the German Alps, Estonia, Sweden and Finland. We hiked or skied in the same terrains as our interlocutors and engaged with them while they were out doing their sports during the winters of 2021/2022 and 2022/2023. Besides participant observation and informal conversations, we conducted interviews with skiers, environmentalists, local inhabitants or other experts, and analysed social media threads as necessary extensions of our hybrid world.

Breaking trail in deep snow or even just leaving a track as we walk along a muddy path seems like a familiar, almost mundane activity. While anthropologist Tim Ingold (Citation2007) ponders the immersive and sensory form of moving through the world, we continue his line of thought with Outi Rantala et al. (Citation2020) who promote a feminist new materialist lens, adding a more political dimension to the way we examine how outdoor enthusiasts critically and physically engage with the environment. To emphasise relationality and the becoming of shared worlds, Tarja Salmela and Anu Valtonen (Citation2019) talk about the concept of walking-with, emphasising the importance of embodied, multisensory experiences in generating knowledge about the environment. Encountering tracks in snow provides valuable insights and understanding of the landscape for those involved. Paths are also shared, co-evolving from human and non-human use of the landscape, serving as an anthropological lens through which to research shared land use and cultural knowledge of places (Van Dooren, Citation2014). Consequently, traces left in snow, and the behaviour they reveal, open the opportunity to inform more effective conservation strategies.

Despite following pre-established tracks (cf. de Potestad, Citation2020, p. 7), most of the outdoor enthusiasts of our studies emphasise that they ‘come here [to the mountains/forest/Arctic] to escape civilization’, ‘to be alone’, seek ‘solitude’ in ‘a spiritual place, where [they] have time to think and process’, or want to ‘merge with the environment’ and ‘explore the forest’. Accordingly, these people rarely self-identify as tourists. Rather, they see themselves as sports people who know the landscape well and are closely attuned to ‘nature’ and the environment (cf. Perrin-Malterre & Chanteloup Citation2018, Roult et al., Citation2017). This knowledge has been acquired as they have moved through the snowy landscapes. Most of them champion their activities—hiking in snow, snow shoeing, ski touring or cross-country skiing—as much less intrusive than alpine skiing with its built infrastructure of lifts, cable cars, roads and hotels as well as artificial snow making with water reservoirs. The sports people say: ‘one only does it when there is snow, when there is no snow, one doesn’t go’, once again stressing the nature-based aspect of their outdoor activities. Nevertheless, the following three examples show that many of them seem to ignore their impacts on wildlife.

Ski touring in the Alps: a story of interspecies ignorance

Activities such as ski touring are now well established in the Alps (Cremer-Schulte et al., Citation2017; Perrin-Malterre & Chanteloup, Citation2018), especially following the pandemic period when many ski resorts were closed for the entire winter season of 2020/2021 (Schlemmer & Schnitzer, Citation2021). Ski tourers on the lower altitudes of the German Alps mainly cross the forest belt, and only on the last few hundred metres do skiers enter the alpine zone. But forests and the surrounding areas are also important habitats for animals, especially for those species not hibernating in winter, who seek refuge as well as food among shrubs and trees. Considering that through this colder period, different types of deer, rabbits and wild grouse are in an energy-saving mode, any disturbance can be critical.

Throughout the Alps, black grouse live along the tree line, where the ecosystem transforms from forest to alpine meadows; they require a ‘complex habitat mosaic’ (Arlettaz et al, Citation2013, p. 139) made up of grassland, shrubs and trees, which provide a wide array of invertebrate prey. In the winter, grouse spend eighty percent of their time digging into snow igloos, which make them invisible to the outside and provide protection from cold winds. However, these dens cannot protect them from intrusion by nature-based outdoor sports. Even moderate disturbance raises the birds’ stress level, which persists for several days.Footnote1 When grouse leave their igloos to flee an oncoming threat, they need to compensate for the energy loss with longer foraging periods, which comes with additional energy expenditure to thermoregulate, i.e. maintain the body temperature, as well as higher visibility to predators (Arlettaz et al., Citation2007, Citation2013). In the German Alps this is mostly the fox which lives in the forest belt and in winter usually does not reach the higher altitudes of the shrubland—unless it finds tracks in the snow that serve as a highway.

One of the interlocutors, a woman in her early thirties who goes on ski tours regularly and is an active conservationist, brought this phenomenon to our attention. With a smirk, she commented on the human-fox-grouse triangle: ‘The fox is clever. When following ski trails it does not sink in [the snow]. Due to the tracks of humans, the fox accesses areas it usually would not reach in winter, where it is a threat to grouse’. A professional hunter and gamekeeper from a bordering district further explained: ‘The fox simply doesn’t like to be belly-deep in snow. So, if there is twenty centimetres of fresh powder, it will stay in the forest, where most of the ground is free of snow’.

While the fox does not necessarily have to hunt and catch grouse, its presence in the higher altitude shrubland is enough to flush them and provoke a flight response, creating a situation similar to stress by human intruders. Such a disturbed energy balance in winter can negatively impact breeding success in the next season, leading to population decline (Arlettaz et al, Citation2007; Bielański et al., Citation2018). In some cases, grouse retreat to other areas altogether. In the German Alps, however, ‘there is not a single mountain range or black grouse area not used for ski touring, snowboarding, downhill skiing, or snow-shoeing’ (Zeitler, Citation2000, p. 242). Given its high human population density and easy accessibility from the Munich metropolitan area, every weekend thousands of outdoor lovers take to the car and hit the slopes.

Generously ignoring the CO2 footprint of their car journey, most of the recreationists we talked to for this study were proud that they experienced the winter landscape solely through their own muscle power. When asked if they had ever crossed paths with any grouse species on their tours, however, the vast majority stated they hadn’t and pointed out that anyway ‘where we go there are so few [people] it doesn’t make a difference’. Like in other studies (Gruas et al., Citation2020; Perrin-Malterre & Chanteloup, Citation2018), the outdoor community points towards others whose activities are more impacting than their own. Although ski touring’s encroachment into the overall environment is certainly less permanent and intrusive than the built infrastructure of ski resorts, conservationists highlight the fact that ski tourers cover a wide terrain, while ski pistes contain skiers in predictable areas and keep human and wildlife activities temporally segregated (Arlettaz et al., Citation2013, pp. 146, 148; Stankowich, Citation2008, p. 2166).

Findings by gamekeeper-scholar-activist Albion Zeitler (Citation2000) from long-term observations show that black grouse can survive in the vicinity of a heavily frequented ski resort, the Fellhorn in the German Alps, and adapt to structural patterns if there are enough refugia for them. Another view was presented by an environmental expert of the German Alpine Club, who suggested it might be better for the environment to have a few ‘Opferberge’ (sacrificed mountains) that contain mass tourism so that other areas stay mostly untouched. With the rising numbers of outdoor enthusiasts in the winter landscape, the Alpenvereine (Alpine Clubs) have increased their efforts to safeguard sensitive ecosystems over the last decade.

The German branch of the Alpine Club especially raises awareness for the black grouse as an endangered species in Germany but also its relatives such as capercaillie, hazel and snow grouse. Conservationists argue that they are indicator species for the well-being of an intact and heterogeneous timberline ecosystem (Patthey et al., Citation2008; Sato et al., Citation2013). To keep ski tourers out of grouse habitat, the Alpenverein recommends guiding them along certain routes. In the late 1990s, an extensive survey of ‘every peak’ in the German Alps was conducted in collaboration of the Alpine Club and the Bavarian Ministry of Environment. Consequently, so-called Wald-Wild-Schongebiete (literal translation: forest-game-sanctuaries) were established. However, compliance by individual skiers with the zones is voluntary.

Signposts (see ) along the route caution trespassers, hand-drawn maps are distributed on relevant online platforms and in the form of flyers for tourists. In recent years journalistic pieces too have picked up on the issue. A young woman who volunteers as a ranger to raise awareness for environmental issues along some of the busiest ski routes summarised her experiences with skiers who encroach in Wald-Wild-Schongebiete: ‘I don’t think most of them have malicious intentions, they simply don’t know. Thank God, more and more are becoming aware because the Alpine Club communicates a lot’.

Figure 1. Signpost alerting skiers to not travers into a game conservation zone; tracks in the snow bear witness to non-compliance. Photo: Florian Bossert, Gebietsbetreuung Mangfallgebirge.

Overall, this hybrid strategy seems to work relatively well. As Cremer-Schulte et al. (Citation2017) demonstrate for wildlife conflicts in protected areas, a combination of on-site guidance and information dissemination through target-oriented communication are the best ways to influence recreationists’ behaviour. The Alpenverein estimates that only three to five percent of skiers disobey the recommendations. The few who do, however, are quite visible as lines in snow. And as visitor numbers increase, more people also end up off-track. So, highly frequented mountains around the lakes of Tegernsee and Schliersee just south of the urban centre of Munich lately had to introduce stricter measures and added a wildlife protection bill to their protected areas (Landschaftsschutzgebiete, IUCN Category V). Local municipalities now have legal backing to sanction skiers who behave inconsiderately and encroach in wildlife conservation corridors. Other campaigns, relying mostly on graphic illustrations in magazines or on social media, target the daily rhythm of animals and recommend not embarking on a ski tour too early in the morning—or even at night—to avoid disturbing the feeding routine of wild animals. However, for the outdoor community this means compromising on utilising the hours after work, on the desire of being alone on the mountain or on the chance to make the first line in fresh snow. Though physically attuned to the winter landscape, in the Alps nature-based recreation does not necessarily produce awareness for wildlife. But the traces left behind by both skiers and animals serve as indicators for conservationists.

Outdoor sports in the Swedish and Finnish Arctic: the sounds of silence intangible impacts

In the remote areas of Northern Europe, winter sports have also gained popularity in the last decade. While research has so far focused on the spatially delimited impact of resource extraction and tourism, such as ski resort development on fragile landscapes (Demİroglu et al., Citation2019; Svensson et al. Citation2021), nature-based activities are on the rise. This has largely been driven by the twin attractions of guaranteed snow over a long winter season, and the chance to enjoy that snow in the vast solitary landscapes of Northern Finland, Norway and Sweden. As is typical of emergent tourist activity, research to date has focused on the early phases of a development cycle—understanding the factors driving this ‘business’ and the value of these remote locations for participants (Berbeka, Citation2018). However, the negative impacts of nature-based winter sports have yet to be documented.

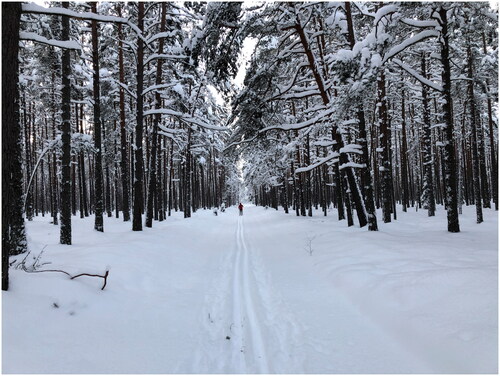

The area of Kilpisjärvi in Northern Finland, four hundred kilometres north of the Arctic Circle, is a popular destination for Arctic tourists hoping to see the Northern Lights or practise snow-based activities such as snowmobiling, cross-country skiing and ice fishing. During a fieldwork trip to the Kilpisjärvi region in March 2022, ski tourers were one of the main tourist groups to be found, outnumbering snowmobilers three-to-one in the access car parks. As in the Alps they set off in the early light of the day making their way out into the wild ().

Figure 2. A group of young ski tourers setting off across the frozen lake for Iso-Malla. Photo: Jonathan Carruthers-Jones.

One group set off east up onto the Saana Fell mountain area, a second group were heading west into the Malla nature reserve, initially unsure of their final route. A third lone individual had arrived tracking the movement of ski tourers in the region on social media and looking to join a group for the day, in pursuit of both company and the safety this brings in avalanche terrain. Spontaneously they decided to head for Iso-Malla, one of the largest summits in the area. In summer such a choice is forbidden by the rules of the nature reserve. The Malla Strict Nature Reserve was designated in 1938 and has been a site of intensive scientific study ever since. Sites with this level of protection (IUCN Category Ia) are relatively rare in Europe, making up just 7% of all protected areas and accounting for only 4.5% of their area (European Environment Agency [EEA], Citation2022). Respecting the nature reserve and its scientific value there are only two footpaths which wind through this thirty-one kilometre squared zone, and visitors are not allowed to leave the paths during summertime. This protects the many endangered mountain plant species, butterflies and birds. In winter, the landscape is not the barren Arctic wilderness we might imagine and grouse species such as the willow grouse and ptarmigan as well as the gyr falcon and even the wolverine remain to eke out a fragile existence.

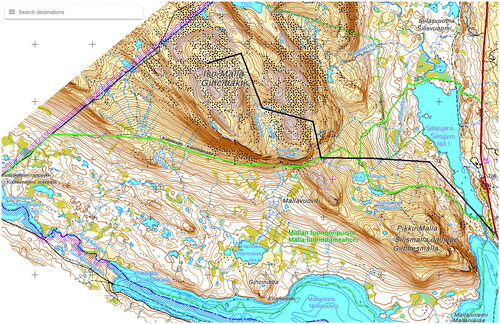

Skiers come to these places because they are lovers of nature. Historically, cross-country skiing was the main activity inside the park in winter, and because of its nature—using narrower skis—most people stuck to the flatter areas and followed the summer trails. The rules and regulations of the park reflect this historical preference and do not take into account the fact that modern ski tourers travel to summits which are far beyond the marked trail (see ). Ptarmigans are not used to this behaviour and the disturbance it brings. As they are often seen close to the paths, they burn precious energy when escaping the perceived threat from passing humans. Furthermore, as climate change accelerates snow cover is not necessarily complete even in November and March. Removing ski touring skis is tricky and skiers will regularly damage the fragile vegetation as they cross between snow patches, with their skis still on. Limiting summer visitors to a few footpaths was designed to minimise both of these behaviours, one may argue now that similar regulations need to be implemented during the winter months. As they do not require permits, regulating the impact of isolated groups of ski tourers who may choose their route the night before they travel is complicated. The highly dispersed nature of ski touring, especially in such a vast landscape, poses a problem for conservation managers going forward.

Figure 3. Locations of regulated summer hiking trails (in green) and example of a track made in winter by ski tourers (in black). Source: Metsähallitus’ web service.

In comparison to the Alps, the Arctic regions bring several challenges to the development of policy solutions. Firstly, there are no well-funded organisations with a large membership who have followed the situation over time, seeking solutions, and secondly getting the information out via signposts across such large areas will be logistically and financially challenging. Yet such problems have been faced before. An example of legislation, which has been extended to cover new leisure tourism activities, relates to snow mobiling. Stricter laws on snowmobiling in Norway (Viken, Citation1998) have changed behaviour in unanticipated ways and they continue to be a source of conflict (Hausner et al., Citation2015). Snowmobiling has also become a high-profile activity in the Malla area with many Norwegians crossing the border to come down into this area creating new conservation challenges. Whilst the activity is forbidden inside the Malla reserve, it is much practised on the edge of the reserve and the noise pollution from this can be heard well inside the reserve. It is well-established in the literature that acoustic disturbance negatively impacts on biodiversity (Berger-Tal et al., Citation2019).

Furthermore, noise has a detrimental effect on the human experience of wilderness, which is often a key driver for tourists visiting such places (Carruthers-Jones et al., Citation2019; Eldridge et al., Citation2020). In the Abisko National Park just over the border from Kilpisjärvi in Sweden, helicopter flights carrying groups of skiers to neighbouring peaks can be heard daily during the peak winter season. As with the snowmobiles, the helicopter flight paths cannot cross the National Park, but for practical reasons they often pass just along the edge of Abisko National Park and this noise pollution is often the only evidence of human influence that visitors to the park report during their visit. As with the snowmobiles in Malla the physical track or flight path the helicopters follow is narrow and spatially limited, yet the National Park is also narrow, and the sound travels all the way across the park.

Whilst such acoustic trails are, like the tracks of ski tourers, ephemeral in nature, they leave a permanent impact on multiple species living in these remote landscapes. As the sound spreads laterally and vertically across the boundary of the park and into the core protected area, it interacts with our near-field experience of place, often becoming the dominant sensory component of our surrounding landscape, or ‘sonotope’ (Farina, Citation2019). This process of the vertical and horizontal integration of experience along a transect (Ingold, Citation2011, p. 153), means that the ‘sonotrails’ left by passing helicopters or snowmobiles become integrated into the ongoing construction of knowledge inside these wild spaces, negatively impacting on the experience of all species moving through them.

Winter sports in Estonia’s Lahemaa National Park: imagined interspecies encounters

Focusing on cross-country ski tracks, the Lahemaa National Park case study shows how the snow makes animals’ presence visible, creating imagined interspecies encounters and new perceptions of the national park itself. This forces us to rethink how we imagine and manage protected areas in times when the number of sports practitioners seeking contact with nature is growing (Perrin-Malterre & Chanteloup, Citation2018). Oandu Visitor Centre, at the east end of the park, attracts visitors year-round to the campsite, forestry museum and seven hiking trails. Of these trails, the Oandu old-growth forest nature trail, a 4.7-km loop, is the most frequented, tramped and visited during the winter by hikers, fat-bikers, skiers and snowshoers—both tourists and locals.

This well-marked RMKFootnote2 trail with its hills and stairs, narrow boardwalks and single tracks can become quite challenging during the snowy period, and even the wider sections of the trail become narrow single tracks as everyone follows the traces made by earlier hikers. The track itself, made by the one who broke the trail after a fresh snowfall, largely follows the marked trail, but in many cases, people cut corners in pursuit of an easier route. ‘The snow,’ said a local who has been hiking the trail for decades, ‘allows you to follow the landscape and not be constrained by the marked trail’. As the official marks on trees or signs on poles are neglected and fresh snowfall covers previous tracks, the landscape becomes the guide for hikers.

This violates the principles established for trail-making. Jaan Eilart published the guideline for Lahemaa National Park in the Estonian Nature 1972 issue: ‘Mark the trail, so that hikers will not deviate from it’ (Eilart, Citation1972, p. 696). In winter, though, when paths disappear under snow, hikers need to orient themselves. The moment people no longer walk on a pre-designed trail, they actively read the landscape (Ingold, Citation2007, pp. 75–76) as they move through the forest and create new relations with their environment.

Through this process, the presence of others on the trail—humans and non-humans, however ephemeral—becomes visible and sensible. While there are significantly fewer hikers during the winter, tracks on snow establish their presence even if they were only left days ago. Sometimes the traces these tracks leave in time even alter the activities of hikers, as a short interview with a winter hiker showed: ‘I knew that there was someone ahead of me [because she had a glimpse of the other hiker], so I slowed down to avoid meeting that person’. Another group of youngsters picked that trail only because someone had already done the hard work of trail-breaking. They had been at several trailheads already, but none had tracks to follow. While it is the landscape that guides hikers in the wintery forest, it is the interaction with others that guides the way humans move and the way they imagine nature.

Similarly, to the footsteps made by the first hiker after snowfall, ski tracks create an easy path to move upon. Hikers who take the Oandu old-growth forest nature trail must cross a ski trail (), connecting Oandu with Võsu village, nine kilometres away, before entering the thicker forest. Although the ski track does not follow the marked hiking trail, hikers tend to instinctively follow it without paying attention to the fact that it takes them off the hiking trail. As a result, I frequently witnessed hikers’ footprints stopping after half a kilometre, turning around after realising their error.

Figure 4. A skier on a Võsu-Oandu ski route. The track is yet untouched from hikers and animals. Photo: Joonas Plaan.

Ski tracks create similar effects in the snowy landscape as hiking trails: they alter the way people move and create perceptions of others in the park. Moreover, as ski tracks take humans deeper into the forest, away from roads and marked trails, they also create possibilities for interspecies interactions and an awareness of wildlife in the area. Straight-lined, snow-packed ski tracks attract not only humans but also non-humans who move in the forest. Animals, like humans, tend to follow the premade route, if possible, explained a local nature guide. It was autumn, and we were following a lynx track when he told me how he knows how animals move in the forest: ‘You must read the landscape. If the path seems walkable for you, then so is it for most big animals in the forest’. This logic became very clear on a ski track, where every now or then a fox, raccoon dog or brown hare had followed the path, sometimes for hundreds of metres. Roe deer, moose and wild boars avoid the human-made routes, but in some sections, a skier can encounter big-game tracks crossing human passage every few metres. The footprints manifest an asynchronous presence of wildlife.

Such imagined encounters alter the way people travel through the landscape. A skier from Võsu village who is regularly on those trails said that animal tracks scare her a bit: ‘I know there are lots of bears in the forest. There was a bear at Võsu beach’. Even if she knew that bears are hibernating, this made her avoid dark patches in the forest: ‘Somebody posted to Facebook animal tracks he saw nearby Oandu trail, and there was a discussion about whether they belonged to a badger or a bear. I do not know, but better be safe than sorry’. The animal tracks, even if harmless, force some skiers to change where and when they move in nature.

The tracks in the snow not only reassemble nature, giving permanence to the ephemeral movements of the others that we share these landscapes with, but they also give meaning to the existence of Lahemaa National Park itself. Jüri, a newcomer from a neighbouring village, bought a cabin in the area simply because this is where there will be snow even if winters become warm and short, as all the climate change forecasts suggest. Usually, he uses his wider skis to explore the area, but once someone has made the ski track between Oandu and Võsu, he puts on his fast cross-country skis. ‘I started to take pictures of the animal tracks to identify them back home’. He knew how the hare moves and the tracks it makes; also, moose and deer tracks are easy to recognise, but once he identified his first lynx track, he became ‘enlightened’: ‘Suddenly I understood why they created the national park here and why all the [nature] protection rules are established’. Nature became visible through the examination of the tracks, and he started to appreciate the need for conservation measures on different scales.

The Lahemaa National Park case study illuminates the intricate and often overlooked interactions between humans, wildlife and the environment and at the same time reveals a tension: between the profound engagement with the natural world when physically moving through snow-covered landscapes and the contestation of nature-based winter sports as inherently low-impact. It therefore suggests that policies and practices governing the recreational use of natural spaces must consider the dynamic and emergent nature of human movement and its ecological ramifications. By fostering a deeper appreciation for the immersive dimensions of winter sports, outdoor enthusiasts can better balance the desire for recreational access with the imperative of environmental conservation.

Conclusion

The seasonal and ephemeral quality of tracks in the winter landscape magnify certain interspecies encounters but also invite humans to ignore them for the better part of the year. Arguably, the tracks left by outdoor enthusiasts have much more ephemeral and localised effects than those of other mechanised users of wild winter landscapes. Since nature-based winter sports do not require much infrastructure, these activities form and disrupt the landscape to a far lesser extent than conventional ski resorts. Nevertheless, people’s presence in the winter landscape is not without consequence: As our examples show, their impacts outlast the traces in the snow long after it has melted away. The same is true for acoustic trails.

While visitors in the Estonian National Park are attuned to detect other animals’ presence through their footprints in the snow, ski tourers in the Alps tend to ignore the coexistence of more vulnerable species along their routes. Outdoor activities in the Arctic magnify the discrepancy of searching for a wild and pristine winter scenery while penetrating it with motorised vehicles.

By critically examining the webs of relations, ski tourers encounter and create on the way, the ecological complexities of interspecies entanglements and their situatedness become perceptible (Rantala et al, Citation2020; Youatt Citation2016). However, such relational ecologies of humans and animals are mostly overlooked by visitors, no matter how well attuned to different aspects of ‘nature’ they fancy themselves. Snow with its ephemeral quality seems to allow for this wilful ignorance. While the copresence of humans and wild animals is rendered visible in snow, they cannot be characterised as ‘companion species’ (Haraway Citation2016); they mainly stay out of each other’s sight, avoid direct contact or register the other’s previous presence with delay.

Such an ‘attitude-behaviour gap’ of people ignoring the impact of their own behaviour while displaying environmentally sensitive attitudes is a common observation in tourism studies (Eijgelaar et al. Citation2015). Tensions between conservation objectives and the outdoor community’s behaviour will only grow as the number of day tourists further increases and the number of snow days decreases (due to global warming). Raising awareness of recreationists’ intrusion into wildlife habitat and, if need be, regulating spatial or temporal separation between species, could ensure a sustainable and responsible access to mountain ecosystems. But the example of an Estonian skier’s ‘enlightenment’ also demonstrates that once wildlife renders itself visible, for example through tracks in the snow, abstract conservationist guidelines suddenly become sensible.

Beyond current academic debates on what constitutes conservation, which state of the environment to aspire to, or what to protect, conservationists unite in the recognition of the living world as made up of more-than-human societal relations and in the appreciation for their ecological value (Luque-Lora, Citation2023). Consequently, wildlife conservation should not be reduced to a reactive stance that operates with regulations and restrictions but must aim to promote the existence of human-animal entanglements (Lorimer, Citation2015). While awareness campaigns by park administrators at Laheema as well as Kilpisjärvi and the Alpine Club already exist, this paper has demonstrated a need to cultivate attention to other species’ presence in the landscape and to tease out additional strategies to sensitise sports people for interspecies encounters and their productive avoidance. The presented case studies highlight that there is more potential to encourage the ‘response-ability’ (Haraway Citation2016) of visitors who are well attuned to ‘nature’, to preserve the winter landscape they physically engage with and value so much, not only for themselves but for all species in it.

Acknowledgements

Our gratitude goes to the CONTOURS project team for their valuable feedback. An early version of the Alpine case was commented on by Roman Ossner from the German Alpine Club. Two anonymous reviewers and the editors of the special issue productively pushed us to clarify and sharpen the argument.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anna-Maria Walter

Anna-Maria Walter holds a postdoctoral position at the Rachel Carson Centre for Environment and Society at LMU Munich. As a social anthropologist, she is currently developing a research project on different forms of relating to and engaging with the cryosphere in the Karakoram/Himalayas and the Alps. Walter’s PhD work focused on the anthropology of emotions, gender relations, and mobile phones in the high mountains of Gilgit, northern Pakistan. Her monograph Intimate Connections was published by Rutgers University Press in 2022. An article in the American Ethnologist on The Self in Times of Constant Connectivity (2021) centres on the conceptions of identity through social media use. Contributions in the recently published volume, The Multi-Sided Ethnographer (transcript, 2024), which she co-edited, highlight the critical methodological engagement with the person of the fieldworker. As a postdoctoral researcher for the University of Oulu, she has worked on socio-ecological dimensions of Alpine ski touring and perceptions of mountain landscapes.

Joonas Plaan

Joonas Plaan is a Lecturer in Anthropology at Tallinn University. His PhD dissertation focuses on how climate change affects inshore fisheries in Newfoundland, Canada. Joonas has done fieldwork among fishing communities and climate activists. He also works at Estonian Fund for Nature as Sustainable Fisheries Expert.

Jonathan Carruthers-Jones

Jonathan Carruthers-Jones’ research is focused on understanding the complex issues which surround human-nature interactions and how they relate to the long-term success of conservation, especially in wild places. Methodologically he uses a participatory approach, working with a range of in-situ visual and acoustic mapping tools. Carruthers-Jones is especially interested in how such methods can be integrated in a transdisciplinary way with long-term spatial and ecological data to deal with the growing challenges facing nature conservation. His Marie Curie doctoral work, for example, combined diverse methods to capture knowledge and data on human perceptions of wild spaces and species with ecological habitat data and ecoacoustic surveys. He has continued working on the themes of wilderness conservation and protected areas management, during a number of post-doctoral follow-on projects. In recent years this research has included a focus on walking methods, ecoacoustics, as well as 360° video, at sites in the Scottish Highlands, the French Pyrénées and the Swedish and Finnish Arctic.

Notes

1 Difference of stress level caused by ski touring or conventional skiing was diminishing. However, the population of grouse in the vicinity of permanent ski resorts is much lower than in respective undeveloped areas due to an immense reduction of fauna diversity (Patthey et al., Citation2008) and possibly also due to predators which are attracted by food remains and use the open pistes to move up the mountain (Arlettaz et al., Citation2013; Caprio et al., Citation2011).

2 RMK is an acronym for Riigi majandamise keskus (State Forest Management Centre), who maintains and manages the visitor centre and hiking trails.

References

- Abegg, B., Jänicke, L., Peters, M., & Plaikner, A. (2019). Alternative outdoor activities in Alpine winter tourism. In U. Pröbstl, H. Richins, & S. Türk (Eds.), Winter tourism: Trends and challenges (pp. 236–245). Wallingford: CABI.

- Arlettaz, R., Patthey, P., & Braunisch, V. (2013). Impacts of outdoor winter recreation on alpine wildlife and mitigation approaches. A case study of the black grouse. In C. Rixe & A. Rolando (Eds.), The impacts of skiing and related winter recreational activities on mountain environments (pp. 137–154). Sharjah: Bentham Science Publishers.

- Arlettaz, R., Patthey, P., Baltic, M., Leu, T., Schaub, M., Palme, R., & Jenni-Eiermann, S. (2007). Spreading free-riding snow sports represent a novel serious threat for wildlife. Proceedings. Biological Sciences, 274(1614), 1219–1224. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.0434

- Berbeka, J. (2018). The value of remote Arctic destinations for backcountry skiers. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 18(4), 393–418. doi:10.1080/15022250.2018.1522728

- Berger-Tal, O., Wong, B., Candolin, U., & Barber, J. (2019). What evidence exists on the effects of anthropogenic noise on acoustic communication in animals? A systematic map protocol. Environmental Evidence, 8(S1), 1–7. doi:10.1186/s13750-019-0165-3

- Bielański, M., Taczanowska, K., Brandenburg, C., Adamski, P., & Witkowski, Z. (2018). Using a social science approach to study interactions between ski tourers and wildlife in mountain protected areas. Mountain Research and Development, 38(4), 380–389. doi:10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-17-00039.1

- Caprio, E., Chamberlain, D. E., Isaia, M., & Rolando, A. (2011). Landscape changes caused by high altitude ski-pistes affect bird species richness and distribution in the alps. Biological Conservation, 144(12), 2958–2967. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2011.08.021

- Carruthers-Jones, J., Eldridge, A., Guyot, P., Hassall, C., & Holmes, G. (2019). The Call of the wild: Investigating the potential for ecoacoustic methods in mapping wilderness areas. The Science of the Total Environment, 695, 133797. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.133797

- Cremer-Schulte, D., Rehnus, M., Duparc, A., Perrin-Malterre, C., & Arneodo, L. (2017). Wildlife disturbance and winter recreational activities in alpine protected areas: Recommendations for successful management. Eco.mont (Journal on Protected Mountain Areas Research), 9(2), 66–73. doi:10.1553/eco.mont-9-2s66

- de Potestad, P. (2020). Tracks and traces of Mont Blanc’s itineraries: An approach through wayfaring. Revue de géographie alpine, 108(3), 1–18. doi:10.4000/rga.7492

- Demİroglu, O. C., Lundmark, L., & Strömgren, M. (2019). Development of downhill skiing tourism in Sweden: Past, present, and future. In U. Pröbstl-Haider, H. Richens, & S. Türk (Eds), Winter tourism: Trends and challenges (pp. 305–323). Wallingford: CABI.

- European Environment Agency (EEA). (2022). Nationally designated areas and IUCN categories. European Environment Agency. https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/daviz/nationally-designated-areas-by-iucn/#tab-chart_5

- Eijgelaar, E., Amelung, B., & Peeters, P. (2015). Keeping tourism’s future within a climatically safe operating space. In M. Gren & E. Huijbens (Eds.), Tourism and the Anthropocene (pp. 17–33). Abingdon, NY: Routledge.

- Eilart, J. (1972). Looduse õpperadade põhimõte ja selle rakendatavus Lahemaal. Eesti Loodus, 11, 696–697.

- Eldridge, A., Carruthers-Jones, J., & Norum, R. (2020). Sounding wild spaces: Inclusive mapmaking through multispecies listening across scales. In M. Bull & M. Cobussen (Eds.), Handbook of sonic methodologies (pp. 615–632). London: Bloomsbury.

- Farina, A. (2019). Acoustic codes from a rural sanctuary: How ecoacoustic events operate across a landscape scale. BioSystems, 183, 103986. doi:10.1016/j.biosystems.2019.103986

- Gruas, L., Perrin‐Malterre, C., & Loison, A. (2020). Aware or not aware? A literature review reveals the dearth of evidence on recreationists awareness of wildlife disturbance. Wildlife Biology, 2020(4), 1–16. doi:10.2981/wlb.00713

- Hamilton, L., & Taylor, N. (2017). Ethnography after humanism: Power, politics and methods in multi-species research. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble. Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Hausner, V. H., Brown, G., & Lægreid, E. (2015). Effects of land tenure and protected areas on ecosystem services and land use preferences in Norway. Land Use Policy, 49, 446–461. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.08.018

- Ingold, T. (2007). Lines: A brief history. London: Routledge.

- Ingold, T. (2011). Being alive: Essays on movement, knowledge and description. Oxon, NY: Routledge.

- Landauer, M., Sievänen, T., & Neuvonen, M. (2009). Adaptation of Finnish Cross-country skiers to climate change. Fennia, 187(2), 99–113.

- Lorimer, J. (2015). Wildlife in the Anthropocene: Conservation after nature. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Luque-Lora, R. (2023). What conservation is: A contemporary inquiry. Conservation and Society, 21(1), 73–82. doi:10.4103/cs.cs_26_22

- Nellemann, C., Jordhøy, P., Støen, O. G., & Strand, O. (2000). Cumulative impacts of tourist resorts on wild reindeer (Rangifer Tarandus Tarandus) during winter. ARCTIC, 53(1), 9–17. doi:10.14430/arctic829

- Neumann, W., Ericsson, G., & Dettki, H. (2010). Does off-trail backcountry skiing disturb moose? European Journal of Wildlife Research, 56 (4), 513–518. doi:10.1007/s10344-009-0340-x

- Patthey, P., Wirthner, S., Signorell, N., & Arlettaz, R. (2008). Impact of outdoor winter sports on the abundance of a key indicator species of alpine ecosystems. Journal of Applied Ecology, 45(6), 1704–1711. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2008.01547.x

- Perrin-Malterre, C., & Chanteloup, L. (2018). Ski touring and snowshoeing in the Hautes–Bauges (Savoie, France): A study of various sports practices and ways of experiencing nature. Revue de géographie alpine, 104(6). doi:10.4000/rga.3934

- Rantala, O., Salmela, T., Valtonen, A., & Höckert, E. (2020). Envisioning tourism and proximity after the Anthropocene. Sustainability, 12(10), 3948. doi:10.3390/su12103948

- Rolando, A., Caprio, E., & Negro, M. (2013). The effect of ski-pistes on birds and mammals: The impacts of skiing and related winter recreational activities on mountain environments. In C. Rixen & A. Rolando (Eds.) The impacts of skiing and related winter recreational activities on mountain environments (pp. 101–122). Sharjah: Bentham.

- Roult, R., Domergue, N., Auger, D., & Adjizian, J. (2017). Cross-country skiing by Quebecers and where they practice: Towards ‘dwelling’ outdoor recreational tourism. Leisure/Loisir, 41(1), 69–89. doi:10.1080/14927713.2017.1338160

- Salmela, T., & Valtonen, A. (2019). Towards collective ways of knowing in the Anthropocene: Walking-with multiple others. Matkailututkimus, 15(2), 18–32. doi:10.33351/mt.88267

- Sato, C. F., Wood, J. T., & Lindenmayer, D. B. (2013). The effects of winter recreation on Alpine and Subalpine Fauna: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One, 8 (5), e64282. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064282

- Schlemmer, P., & Schnitzer, M. (2021). Research note: Ski touring on groomed slopes and the COVID-19 pandemic as a potential trigger for motivational changes. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 41, 100413. doi:10.1016/j.jort.2021.100413

- Stankowich, T. (2008). Ungulate flight responses to human disturbance: A review and meta-analysis. Biological Conservation, 141(9), 2159–2173. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2008.06.026

- Stoddart, M. C. J. (2012). Making meaning out of mountains: The political ecology of skiing. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Svensson, D., Sörlin, S., & Saltzman, K. (2021). Pathways to the trail: Landscape, walking and heritage in a Scandinavian border region. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift - Norwegian Journal of Geography, 75(5), 243–255. doi:10.1080/00291951.2021.1998216

- Taylor, A. R., & Knight, R. L. (2003). Wildlife responses to recreation and associated visitor perceptions. Ecological Applications, 13(4), 951–963. doi:10.1890/1051-0761(2003)13

- van Dooren, T. (2014). Flight ways: Life and loss at the edge of extinction. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Viken, A. (1998). Tourism regulation: Cultural norms or legislation? Outdoor life and tourism regulation in Finnmark and on Svalbard. In B. Humphreys, A. Pedersen, P. Prokosch, & B. Stonehouse (Eds.), Linking tourism and conservation in the Arctic (pp. 63–74). Tromsø: Norwegian Polar Institute.

- Youatt, R. (2016). Interspecies. In T. Gabrielson, C. Hall, J. M. Meyer, D. Schlosberg, & R. Youatt (Eds.) The Oxford handbook of environmental political theory (pp. 211–225). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Zeidenitz, C., Mosler, H. J., & Hunziker, M. (2007). Outdoor recreation: From analysing motivations to furthering ecologically responsible behaviour. Forest Snow and Landscape Research, 81(1/2), 175–190.

- Zeitler, A. (2000). Human disturbance, behaviour and spatial distribution of black grouse in skiing areas in the Bavarian alps. Cahiers D’Ethologie, 20(2-3-4), 381–402.