Abstract

This article profiles the development of the Melbourne Korean War Memorial and shows how a memorial can provide a sense of inclusion by considering symbolism in all aspects of design. We argue that through metaphoric symbolism we can demonstrate a contemporary memorial as an educational tool for all visitors and future generations, while honouring the sacrifice of servicemen and women. We focus on co-design research to examine how facilitated engagement with multiple stakeholders plays a fundamental role in conceiving cultural objects within an urban context, and demonstrate meaning by reflecting on the design, engineering and construction of the Melbourne Korean War Memorial.

Introduction

War memorial design has a very long history, globally, as nations seek to honour those who were injured or lost their lives in support of a campaign. From the White Monument at Tell Banat, Aleppo Governorate, Syria in the 3rd millennium BC—believed to be the world’s first such memorial (Porter, Citation2002)—from the 3rd millennium BC to current plans for a future memorial in the United States to acknowledge the global war on terrorism (Ackerman & Ballou, Citation2023), designers, historians, engineers, and architects have looked for innovative and meaningful ways to mark these significant events. In Australia, like many Western countries, there is also a long tradition of building memorials for overseas campaigns, where local citizens served alongside people from other nations. This paper reports on the design and development process engaged in for one such memorial project – the Melbourne Korean War Memorial. A range of designs were conceptualised, while extensive research on existing memorials was completed to shape what would become the centrepiece of remembrance for Korean War history in Melbourne, Australia. The contribution is significant to respect those Australians who fought and lost their lives during the Korean War, and to educate the next generations of the important sacrifice these servicemen and women made for their country.

The Melbourne Korean War Memorial creation process raised four concerns: How do we design it to address the social relevance of the war memorial today?; how do we integrate it into the urban landscape providing a sense of inclusion?; how do we accommodate the sensitivities and needs of multiple stakeholders including veterans?; and how do we actually make it? Many historians have called the Korean War ‘the forgotten war’ (Mackenzie, Citation2013). Our aim was to give a public focus to a forgotten war that also ‘spoke’ to all generations. To do this, we focused on the relationships between symbolism and its meaning to the community, while also understanding the physical constraints associated with outdoor urban installations such as weather, longevity, and vandalism, to name a few; but the story of the war and the veterans’ contribution was the most important design consideration.

The unique aspect of this paper is documenting the industrial design and engineering approach, as opposed to the usual approach for memorial designs from urban designers or sculptors. Specifically, we show how co-design was used to develop symbolism for meaningful learning experiences embedded within a contemporary memorial. The uniqueness of this was translating co-design theory into practice via an interdisciplinary, community-driven endeavour. By using industrial designers—who have expertise in human-centred design—we encourage public interaction, to engage the eye, to engage other senses, and to provide an immersive experience. Industrial designers also know how to satisfy client/stakeholder expectations that projects be ‘on time and on budget’. Therefore, we argue a co-design approach using industrial design and engineering is the best way of engaging the public in a large expensive object, designed to be left in the wind, rain, and hot sun, constructed on a reclaimed industrial landscape. This is largely due to the expanded work of progressing the co-design approach, which often ends at the prototyping phase (Paay, Kuys, & Taffe, Citation2021), into a physical outcome that represents veterans’ experiences and helps tell the story of the war, to serve as a learning aid for future generations. Our work expands on a recent study by Given & Kuys (Citation2022), which looked at memorial design as information creation. In this paper, we adopt a similar approach but concentrate on symbolism used in all aspects of design to create a sense of inclusion for those who engage.

While the focus of this paper is outlining how a co-design approach led to the creation of an inclusive war memorial, it is important to discuss the position of three of the authors as both project participants and researchers, including as representatives for the voices of the 14 other stakeholders involved in the co-design process. To minimise researcher bias, we have included a fourth co-author in this paper who was not involved in the memorial’s design nor construction. The design team followed her foundational work on qualitative research (Given, Citation2008), adopting the role of a practitioner-researcher and insider-researcher; this allowed for easier negotiations for research access, and in-depth knowledge of the stakeholder engagement, which created a greater understanding of the various complexities that existed within the co-design process (Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, Citation2012). We acknowledge that the position of being an insider-researcher and practitioner-researcher has implications that can serve as both a benefit and detriment to the research (Given, Citation2008; Saunders et al., Citation2012); yet this process enabled the team to capture the voices of all 17 stakeholders contributing to the co-design activities. We support the position of self-awareness as researchers involved in this project and support the ‘voice’ of the designer in the greater context of this research. Researchers need to be reflective of how their insider status can affect the data collected, analysed, and shared through publication; self-awareness can be exemplified as a strength in immersive qualitative research (Given, Citation2008).

Background – the ‘forgotten war’

To provide context to this paper, this section explains key moments of the Korean War, including the Battle of Kapyong (now known as Gapyeong), which influenced the memorial design as explained in detail throughout the paper. Several factors influenced the Korean War’s nickname of the ‘forgotten war’ or a ‘police action.’ The Korean War came after the global tumult of World War II, tiring a war-weary world. The United States (US) Congress never officially declared war on North Korea, but twenty-one allies were led by a United Nations (UN) command (Vergun, Citation2023). The Korean War, between Soviet-backed Democratic People’s Republic of Korea to the north and the pro-Western Republic of Korea to the south, began on the 25th of June 1950 when North Korea invaded South Korea. The US called on other allies to assist under the UN command, with Australian troops fighting the Chinese 60th division during the decisive Battle of Kapyong in April 1951, resulting in 32 Australian deaths (Matray, Citation2011). In total, more than 17,000 Australian sailors, soldiers and air force troops served during the Korean War, including 50 nurses. Of those 1,500 were injured, 340 were killed, 30 were taken as prisoners of war, and 43 were listed as missing in action (Stueck, Citation2010). The war ended with an armistice on July 27, 1953, but Australian forces remained in Korea in a peace-keeping role until 1957.

Many memorials to the Korean War have been erected since this date. So why do we need another? Is the war memorial genre an anachronism in the early decades of the 21st century? Another ‘war’ (of sorts) has emerged over time, with increasing debate over depictions and designs of war memorials themselves. Historically, public taste favoured traditional memorials based on life-sized metal statues of soldiers, but increasingly critical voices in academia and the media now tend towards abstract and symbolic designs. But sadly, while wars are fought, there are sacrifices to acknowledge; to remember and honour the ‘forgotten war’; for the mental health of veterans; for the children and grandchildren to make sense of injured or missing parents and grandparents. To design a new memorial is to be conscious of adding to a long tradition of commemorating sacrifice, and to be conscious that this is an increasingly contested tradition. For instance, there are many voices calling for ‘Peace-Memorials’ and not ‘War-Memorials’, hence our theme of styling our project as a symbolic ‘Bridge between Nations’. Beyond remembering the events, people, or circumstances that establish cultural identity and values, our memorial aligns with Hundley (Citation2013) by intending to improve mental wellbeing, reminding the individual of their cultural identity while reducing psychological stress. Memorial sites are spaces of shared memory that give different possibilities to express and interpret individual and collective loss (Wagoner & Brescó, Citation2022). Such a process is not only about mourning but also can help individuals and societies to reinterpret the past, and in so doing, construct new orientations to the future (Wagoner, Citation2017). Wagoner & Brescó (Citation2022) state that, ‘the key to immersive memorials is the need to move through them… freely moving through memorials becomes key to the way in which they are experienced and made sense of by visitors’ (p. 8).

Architectural critic Kirk Savage’s Monument Wars (Citation2009) reviews the changes in taste between traditional memorials and recent progressive ones. Savage reflects that ‘Public monuments were an inherently conservative art form’ (Savage, Citation2009, p. 10) that the viewer merely looks at from afar. But he also observes the change to a more ‘interactive memorial’ that the viewer can physically enter and experience. And in terms of imagery, critics argue heroic bronze statues no longer seem adequate. Instead, symbolic representation is needed to carry larger messages of sacrifice and suffering. These two different design philosophies, the traditional and the progressive, can be observed in memorials of the Korean War internationally. The critical and public debates around the success of these works often related to whether they were of a traditional figurative style with life-sized bronze statues of soldiers, or abstract and symbolic in design. In all cases, public taste favoured the figurative and romantic tradition. This has led to the corruption of many memorials where bronze soldiers were sometimes grafted onto otherwise simple, abstract designs, seemingly against the original artists’/designers’ wishes. For example, the Washington DC Korean War Veterans Memorial in the US is a powerful geometric composition on top of which life-sized bronze statues of soldiers are marching across a landscape of grass somewhat compromising the purity of the overall design – we were eager not to do this, as our intention was to follow inclusive design methodologies where the memorial becomes an architectural symbol of storytelling (Lyu, Citation2019).

A more successful design is that of the Korean War Memorial located in Moore Park, Sydney, which retains a purity of symbolic design, uncompromised by any arbitrary addition of bronze soldier statues. Designed by Jane Cavanough Artlandish and Design with detail design by Steven Hammond (Group GSA), it was erected in 2009. Instead of heroic bronze statues, tall flower stems (representing dead from New South Wales) stand amongst symbolic profiles of the contours of mountain ranges. This review of earlier memorials helped inform our design decisions.

From an industrial design and engineering perspective, identifying the objectives was critical in the earlier stages of the design process (Kembaren, Simatupang, Larso, & Wiyancoko, Citation2014; Li, Wang, Li, & Zhao, Citation2007). Understanding the historical context is the foremost step to grasp the overall objective and narratives from the past, to be used in objectification of memory in war memorials and monuments, as outlined by Beckstead, Twose, Levesque-Gottlieb, & Rizzo (Citation2011). Literature shows that one of the main aims of memorials created after traumatic events is to provide therapeutic value for the public and those directly affected, such as veterans and family members (Collins, Allsopp, Arvanitis, Chitsabesan, & French, Citation2020; Maple, Edwards, Minichiello, & Plummer, Citation2013). Memorials are described as a ‘device to manage emotions and deal with grievances and contestation’ (Margry & Sánchez-Carretero, Citation2011), bringing importance to a space for public awareness and remembrance, while also acting as a sanctuary for dealing with loss (Hundley, Citation2013).

Stevens & Sumartojo (Citation2015) recognise that each community has their own understanding of war which adds a complex layer at the local level. Creating the connections between the community and the cultural object was critical throughout the duration of our project. In a later paper, Stevens & Sumartojo (Citation2019) further explore the complex layers of war memorial building at a community level, as each must negotiate their own understanding of the national story, which affects specific aspects of community identity.

Methodology

The methodology was determined after numerous consultations with all 17 project stakeholders. The stakeholders included a mix of researchers, designers, and government representatives; abbreviations are provided here, as these are referenced in later sections of the paper (e.g. see ).

Table 1. Symbolic characteristics of war memorials.

The design and engineering team: 4 x Industrial Designers (ID), 2 x Architects (Arch), 3 x Engineers (Eng) and 1 x Historian (H).

The client team: 1 x Victorian Government (VicGov) representative, 3 x Maribyrnong City Council (MCC) representatives, 1 x Korean Consulate General (KCG) and 2 x Korean Government (KGov) representatives.

The 17 project stakeholders were members of the Melbourne Korean War Memorial Committee and met weekly over a two-year period. Designs were constantly debated and iterated throughout this period and final decisions were made by consensus via these 17 project stakeholders. There were, however, multiple meetings with extended veterans, their families, as well as public events hosted by the council to share the design outcomes with the community. These public events guided the process and helped structure the co-design sessions with the 17 project stakeholders.

The overarching objective was to design a contemporary memorial that could be seen as an educational site for younger generations to better understand and respect the sacrifices demanded of war. This was critical as over time, memorials face a loss of relevance as generations pass and society evolves to embody different shared memories and values (Hundley, Citation2013).

We sought to advance understanding in symbolism in existing Korean War Memorials to guide the development of a new one for Melbourne. The paper addresses this through two overarching questions. First, the analysis explores how we can design a new memorial to address the social relevance of the war memorial today. We referenced work from Cox (Citation2016) about how there is always some uncertainty about how to best memorialise past events. This includes asking such questions as: What historical factors need to be considered? Which group’s narrative should be most prominent? Which figures or events are worth focusing on? (p. 4). Second, we examine how metaphoric symbolism is used to keep cultural values alive. These two, overarching questions were also used for stakeholder engagement to provide a clear agenda for the design and engineering team to navigate.

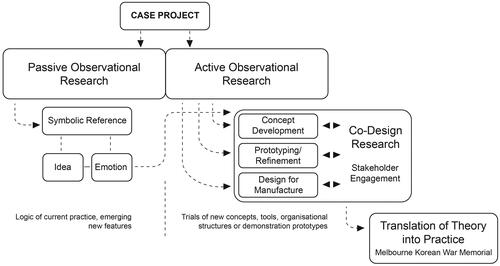

The main method used was co-design (as a subset of a design thinking methodology), which offered techniques and tools for embedding design thinking (Kleinsmann, Valkenburg, & Buijs, Citation2007; Madden, Cadet-James, Atkinson, & Lui, Citation2014). Co-design was employed for the project to combine the domain expertise and strengths of all relevant stakeholders in an equitable and fair manner (Muller & Druin, Citation2012). Theorising co-design techniques through a product/urban design lens broadens the scope and depth of this work to ensure design thinking approaches matured into a constructed urban installation. It is noted that co-design has a long history in design disciplines (Lee, Citation2008) dating back to the 1970s; however, there is minimal work showing the translation of co-design theory into practice. To do this, the research team employed an interdisciplinary, community-driven co-design approach to both document and integrate the necessary knowledge into the final memorial design. The ability to examine and theorise the co-creation process of a large-scale, public design project provided insights into co-design techniques and connection to ‘meaning’ through symbolic elements made possible by numerous facilitated co-design sessions. Most notably, Sienkiewicz (Citation2015), whose research views visitors as active participants in the process of meaning-making, had an influence on the Melbourne Korean War Memorial co-design approach. What makes our approach unique, however, is applying the theories derived from Sienkiewicz (Citation2015) (namely constructivist learning theory) into a physical artefact that visitors immerse themselves in, rather than merely look at (as seen in Sienkiewicz’s work focused on art museums). An example of this difference is taking knowledge gained through the co-design approach to provide implicit, explicit, and embodied meaning into the final memorial (Given & Kuys, Citation2022). This is done to help overcome the lack of perceived prior knowledge and life experiences for younger visitors who may see war as something from ‘the past’ and not well understood today. By purposefully designing symbolic elements into the outcome, we provide visitors with the tools needed to foster a greater understanding of the memorial’s purpose through the display of quotations, statistics, images, and facts about the sacrifices made. Where many memorial interpretations are influenced by prior knowledge (Mayer, Citation2005), our approach looked at a contemporary design to connect visitor experience with explicit symbolic elements to contribute to meaningful learning experiences (Anderson, Storksdieck, & Spock, Citation2007; Falk & Dierking, Citation2000).

Following our co-design method, we derived an approach from Chadwick’s early work (Citation1971), where symbolism is defined as the art of expressing ideas and emotions not by describing them directly, nor by defining them through overt comparisons with concrete examples, but by suggesting what these ideas and emotions are by creating them in the mind of the viewer through the use of unexplained symbols. Symbolism is described as any mode of expression which, instead of referring to something directly, refers to it indirectly through the medium of something else (Chadwick, Citation1971). Chadwick’s work referred specifically to symbolism found within poetry; we took this approach and combined the theory of Chadwick with work from Naaranoja, Kähkönen, & Keinänen (Citation2014), which looked specifically at construction projects as research objects. By doing this, we were able to set parameters that would ultimately enhance the symbolic elements of this research that were importantly translated into a ‘constructed’ object – the Melbourne Korean War Memorial.

Findings and discussion

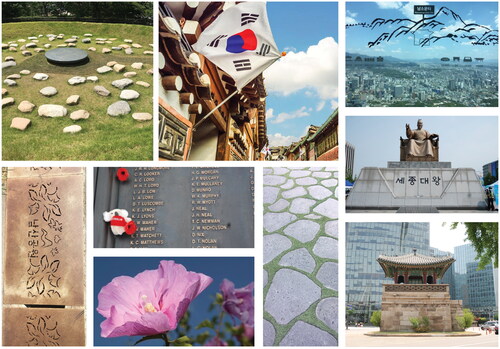

Memorials must engage with both the symbolic and operational freedom and diversity of the landscape in which they are installed; in our project, observations of the location led to certain symbolic elements being identified that were specific to the site. These were then used to inform additional observational research which took place in South Korea (Seoul, Gapyeong, and Busan) and Australia (Melbourne, Canberra and Queensland). By assessing established memorial designs through both observational research, the team identified key elements, such as materials and construction techniques, location and urban planning, symbolism and communication design, as well as meaning and reflection. Photographs were taken throughout these phases and presented to stakeholders in the first of many co-design sessions that were held to determine symbolic characteristics that could influence the concept development phase. Select examples of these photos for both South Korea and Australia are shown in and .

Figure 1. Adaptation of Naaranoja, Kähkönen and Keinänen’s (2014) different approaches for studying construction projects with the inclusion of Chadwick’s Chadwick (Citation1971) work to better understand symbolic elements within a co-design framework.

All 17 stakeholders were then asked to list their top four symbolic characteristics based on the photographs taken during the observational research (see ). These were identified through observational research in a co-design session and ranked by importance by each stakeholder; colours are applied in the table to identify related characteristics.

The symbolic characteristics were evaluated among stakeholders using Kimbell’s (Citation2011) co-design framework, which was later adapted by Pedersen’s (Citation2020). This framework was deemed most appropriate as it allows everyone to have a voice through a facilitated session, and then allows for reframing to arrive at an agreed position. This consists of the following:

Staging moves (interpretation, framing and inspiration, setting up spaces for co-design).

Facilitating negotiations by circulating intermediary objects and improvising within the space and across space boundaries.

Reframing as a result of negotiations (Pedersen, Citation2020).

As a result, the research team arrived at six major themes that were incorporated into the final design (see ).

Table 2. Set of six symbolism themes used to guide the design process.

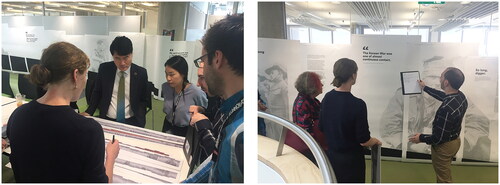

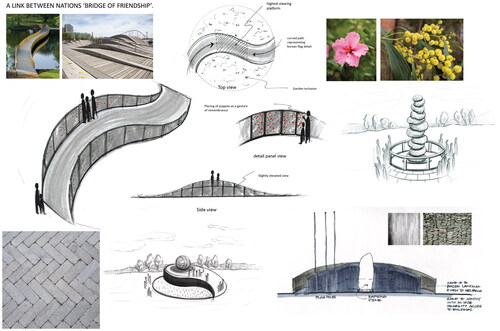

This thematic process cemented inspiration for the concept development phase, which was the main starting point for the co-design process. While discussions and ideas were shared earlier with all stakeholders, it was only when initial, visual concepts were brought forward by the design and engineering team that formalised co-design work progressed. The ability to ‘spark’ ideas through visual aids created more enthusiasm during the co-design sessions as stakeholders could start to see the memorial ‘come to life’ (see ).

Figure 4. Ideations with material consideration based on identified symbolic themes and observational research imagery.

Figure 5. An example of co-design sessions with the veterans, design and engineering team, council members and community stakeholders over a two-year period.

Importantly, the research findings and concept development were presented (and interrogated) weekly for feedback, which involved extensive review and iterations in the design process. The approach adapted from Kimbell (Citation2011) and Pedersen (Citation2020) ensured appropriate facilitation, which brought to life the stories of veterans who fought and had lost friends in the war. Their personal insight and storytelling were invaluable in representing the six symbolism themes into a final design.

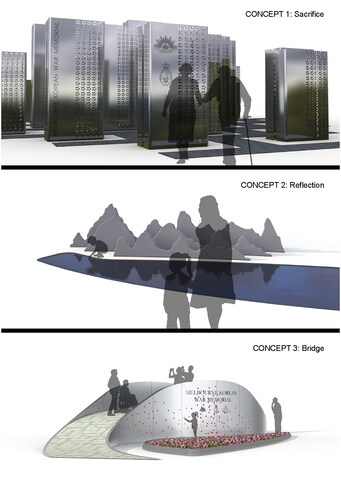

As the project progressed three final concepts were presented to all 17 stakeholders (see ), this was a result of more than 3-months of ideation sketching, basic Computer Aided Design drawings, and multiple 3D renderings.

To conclude the concept selection phase, we engaged all 17 stakeholders to evaluate the concepts against the six identified themes. We used an adaptation of a ‘concept scoring matrix’ developed by Xiao, Park, & Freiheit (Citation2011) to provide greater understanding of which concept best evoked the symbolic themes identified in this research. The 17 stakeholders were asked to score each concept out of 3 (1 indicating a strong link to the symbolic theme and 3 indicating a weak link). The sum of each score was added to each theme to understand which concept was most preferred. There was overwhelming support for Concept 3 with the lowest score (strong link to the symbolic theme) of 148, followed by Concept 2 (214) and Concept 1 (222) (see ).

Table 3. Concept scoring matrix showing data for C1, C2, C3 scored against six themes.

Concept 3 was determined by overwhelming consensus to be the design that should be pursued; the concept was refined and disseminated via in-person, community-wide meetings organised by the Consulate General of Korea. These meetings attracted ∼300 attendees including veterans and their families. The lead author presented the final selected concept (see ) and explained how the six symbolic themes would be incorporated into the final design. Community consultation then commenced following standard ethical protocols set by the Council. There was disagreement between some stakeholders, but no formal objections were lodged after a 30-day community consultation process. That allowed the memorial to progress into detailed design, engineering, and construction. Despite divergent views and disagreements (as in common to co-design processes involving diverse community members), the nuanced product design approach and strict milestones allowed for focused progress that resulted in an outcome that satisfied the majority. Individual views were heard, and the facilitated co-design sessions allowed for negotiations and reframing that ultimately resulted in a final design that could be approved by the primary stakeholders for production and installation.

The following section provides an in-depth analysis of the key themes that informed the co-design process and provides detail on how the symbolic elements were integrated into the Melbourne Korean War Memorial. This provides evidence of how the research team worked closely with stakeholders to translate co-design theory into practice via an interdisciplinary, community-driven outcomes.

National identity

Representing national identity within the memorial was an important aspect to respect and remember the Australians and South Koreans who served in the Korean War. Apart from obvious inclusions such as the Korean and Australian flags enamelled on the outside of the memorial, we explored form development by expressing the ‘Taegeukgi’ from the Korean flag which is visible from the plan view (see ). To complement this, we developed garden beds mixed with the Australia national floral symbol (the Golden Wattle) and the South Korean national floral symbol (the pink Hibiscus flower). Gardens are one of the most prominent motives to evoke narratives through folk and individual memory (Hundley, Citation2013). From a wellbeing perspective, incorporating nature into the design can complement medical intervention and help improve health outcomes (Dustin, Bricker, & Schwab, Citation2010). These floral symbols were also perforated into the aluminium panels along with the story of the Australians who fought in the Korean War.

Figure 8. The ‘Taegeukgi’ from the Korean flag alongside a plan view rendering of the Melbourne Korean War Memorial.

Kirk Savage notes memorials can contribute to the creation of national identity: ‘Clustered together in one place, these monuments to heroes of all different time periods create a memorial landscape that evokes an abiding sense of national identity.’ (Savage, Citation2009, p. 10). This is arguably true of how Canberra’s Anzac Parade can be interpreted but this is problematic, as most of the existing memorials present a fixed (white male) national identity based on indominable life-sized bronze warriors, that is not inclusive of women. Nor do these statues acknowledge the suffering of the public, nor acknowledge the fact that soldiers are also victims of war. Bronze statues no longer seem relevant – instead symbolic representation is needed to carry these larger messages of sacrifice and suffering. This is what most project stakeholders disliked about many of the existing memorials and sought to change. The role of Australian women in the war is therefore acknowledged in the Melbourne Korean War Memorial via imagery within the panels.

The ‘walk-way’ design of the memorial symbolises a bridge between Australia and South Korea. The pillar-like panels arranged in staggered configurations represent South Korea rising from the ashes after the war. The poignant images of soldiers on the panels are made up of thousands of perforations, allowing visitors to place remembrance poppies within the memorial. To complement this, a natural stone plaque from Gapyeong was included at the entry point of the memorial allowing visitors to pay their respects and obtain preliminary information about the site.

Unification

After the concept deliberations during the stakeholder and community co-design sessions, it was no surprise to the design team that the ‘bridge’ concept (Concept 3) was chosen. This held the most symbolic elements with the emotional connection of the form and the material representing the strong connection between South Korea and Australia. The ‘bridge’ concept represents a dream of one day unifying Korea. This concept also maximises the location in which the memorial was constructed by providing unobstructed elevated views of the City of Melbourne.

Significant consideration was given to the paving stones to connect materiality with unification and national identity. The paving stones were blended between the dark-coloured Melbourne bluestone which was quarried in the Maribyrnong municipality (where the memorial is located) mixed with the lighter-coloured Gapyeong granite airfreighted from Gapyeong, South Korea (i.e. the site of the Battle of Kapyong). This added meaningful symbolism to the connection created on the pavement visitors physically touch when visiting the site. By gradually mixing the two different stones we represented the strong relationship South Korea and Australia were able to form after the war (see ).

Storytelling

Reflecting on one of the main outcomes of the co-design sessions (using symbolism to develop a contemporary memorial as an educational tool for future generations), we included positive interrelationships between individuals, open communication, trust and understanding during different phases of the project (Paay et al., Citation2021) to ensure the final outcome conveys the story of the war correctly. This involved multiple iterations from an external graphic design agency and close consultation and approvals from the Melbourne Korean War Memorial Committee.

The aluminium panels gave an opportunity to graphically introduce the historical narration as a part of the design rather than standalone information accompanied by the artefact. The panel material allowed engravable surfaces as well as perforations which were used to present imagery throughout. Actual images from the war were chosen to be perforated as a visual aid complementing the historical narration. These formal elements gave weight to the memorial despite the casual setting within a communal park. By choosing perforations to depict imagery in the aluminium panels, we created a functional area for placing poppies as a sign of remembrance for all visitors. The internal panels tell the story of the Korean War and Australia’s important role through a combination of quotes and subtle supporting imagery. The stories, sobering statistics, a list of the names of the fallen soldiers and explanatory graphics, inform visitors of key aspects of the war. Exterior panels also feature national flowers, Wattle for Australia and the Hibiscus for South Korea. The front of the panels consists of exactly 17,164 punched holes representing the number of Army, Navy and Air Force personnel from Australia who fought in the Korean War. The names of the 340 Australians killed during the war are etched on the front of the memorial as a clear sign of respect and remembrance.

Materiality

The design and engineering team started to explore potential materials as the design process began. The use of hard, long-lasting materials such as metal, concrete, brick and mortar in the construction of these memorials is practical, durable and also forcefully conveys the social necessity of remembering (MacDonald, Citation2006). Inscribing stories and names on a war memorial made of such long-lasting materials demonstrate the significance of marking heroism across many countries (Beckstead et al., Citation2011). Beckstead et al. (Citation2011) argue the importance of presenting meanings through such physical elements in war memorials. These important monuments create opportunities such as expressing gratitude, sharing memories, educating young minds, reconstructing social identities, and honouring past sacrifices. The materials were chosen carefully to represent these social purposes, as well as reflecting expert knowledge of those materials by the design and engineering team.

Understanding the role of materiality in this context soon became the focal point of the project. While the form of the developed concepts carried a symbolic function, the connection between different materials elevated the overarching concept and created serious buy-in of stakeholders and community members during the co-design sessions. Debate was heard between the design and engineering team around manufacturability and feasibility alongside stakeholders’ desires around aesthetics and meaning. In balancing these imperatives, through its materiality, the war memorial guides the direction of the community’s interpretations which fits into societal disclosure of remembering (Forty & Küchler, Citation1999).

The materiality embodied within urban installations provides opportunities to evoke particular experiences with their physical entity (Ashby & Johnson, Citation2010). Designers need to consider other aspects beyond physical elements such as product personality, user interaction, and emotions in their material decisions to reflect the intended meaning of a product. As discussed by Karana, Hekkert, & Kandachar (Citation2010) materials are selected to create certain experiences for users. The greater role played by materiality over the form itself was evident during the concept development process. The materiality of the memorial can be seen to elicit a particular collective emotion from the past as a shared form of memory (Forty & Küchler, Citation1999).

From a practical point of view, aluminium panels were chosen because of the material’s corrosion-resistant characteristics, as well as ease of manufacturing and ease of replacement, in cases of vandalism or other damage. Natural stone was chosen for its durability and symbolic reference to Australia (Maribyrnong bluestone) and South Korea (Gapyeong granite). Identification of function, objectives, and constraints of the design was a starting point for material selection process (Ashby, Bréchet, Cebon, & Salvo, Citation2004). As the design matured, material specifications were measured against the design intentions with structural engineers during the concept development stage. Multiple prototyping stages took place to test the material constraints which included 1:1 scale models made from the actual materials (see ).

Figure 12. View of the Melbourne Korean War Memorial showing the inclusive design and storytelling on the inside panels.

Inclusion

The needs of veterans and their families were considered at every stage of the project and were the underpinning value of all co-design sessions. The Melbourne Korean War Memorial became a key focal point in Quarry Park, Melbourne with its publicly accessible city view. To address the symbolic desire of social inclusion, the stakeholders purposefully created a scenario where the public walks onto, and through, the memorial to absorb information, rather than traditional memorials where the public simply views from a distance with minimal interaction with the memorial itself. To support this, the storytelling begins from the inside of the memorial enticing the public to engage as they enter the site. Supporting Gurler & Ozer (Citation2013), the memorial creates a tourism opportunity for Melbourne with a positive effect on social memory and urban identity. The setting of the memorial is important in this aspect. Gurler & Ozer (Citation2013) argue that designers can create an inspiring space where visitors can reflect by building a memorial within the community. From a practical point of view, the memorial adheres to all Australian/New Zealand standards for accessibility (e.g. access, ingress, egress), making this an important place of reflection for all ages.

Commemoration

From the outset, the Melbourne Korean War Memorial was about expressing gratitude, sharing memories, reconstructing social identities and honouring past sacrifice. Unlike several major new memorials around the world that focus on victims rather than heroes (Doss, Citation2010; Till, Citation2005), we designed this memorial around storytelling to educate younger generations about the significant role Australians played in the Korean War. The memorial serves a discursive function in communicating the values of the state to its urban publics (Stevens, Citation2014; Stevens, Franck, & Fazakerley, Citation2012). The architecture creates a form of storytelling using symbolic materials and design configurations within the context of historical significance (Lyu, Citation2019).

The large memorial stone was donated and transported from South Korea’s Gapyeong City Council. Weighing almost two tonnes, it forms a symbolic location for the laying of ceremonial wreath, which was deemed vitally important for commemoration. Public responses to the memorial have been moving:

It was extremely humbling to see the effect of what the memorial means to people when I was in attendance at the opening. Seeing people become extremely emotional as they walked through the memorial, pointing out names they recognised in the names of the fallen, really hit home for me that this is clearly more than just metal, stone and concrete. This is now a place of remembrance – Project manager for the Melbourne Korean War Memorial.

Conclusion

The Melbourne Korean War Memorial is now a permanent fixture in Quarry Park, Melbourne, and is the first significant public memorial in Melbourne to specifically honour Australians who served in the Korean War, and the Koreans who fought alongside them. Quarry Park has become a place to reflect and honour the sacrifice the Australian servicemen and women made while serving in the Korean War.

The design process went for 2-years with multiple co-design sessions with the Melbourne Korean War Memorial Committee, veterans, the design and engineering team, the Maribyrnong council, and the local community. Underpinning this collaboration was extensive research into past war memorial designs and the symbolism used to illicit respect and honour for war veterans. However, as ‘the forgotten war’ it was also critical that the design was an educational vehicle for storytelling. The co-design sessions revealed the importance of an inclusive and interactive memorial to a broad public audience that was representative of a broad range of stakeholders, with significance given to the veterans who were a part of every co-design session and meeting throughout the entire project.

The initial observational research which informed key symbolic themes within a co-design scenario can be applied as a helpful design strategy to support further stakeholder engagement research. The scaffolded approach from initial historical research, analysing existing memorials and involving all stakeholders at the beginning of the design process, contributed to an inclusive outcome that translated theory into practice. The unique contribution of this paper is demonstrating how symbolic themes developed during the co-design sessions were purposeful integrated into the Melbourne Korean War Memorial. These nuanced details of national identity, unification, storytelling, materiality, inclusion and commemoration provide real-world examples of how co-design research can be used effectively to transition into large-scale urban installations. The result is a model and method for designing future memorials or other significant public artefacts that aim to illicit strong connections to the community and engagement with culture. The ‘Bridge between two Nations’ can now be explored and enjoyed, and serve as a place for healing and quiet reflection. The symbol of the Taegeuk, based on the Taoist concept of Yin and Yang, speaks of the balance of the opposing principles of eum (earth) and yang (heaven). The lilac Hibiscus syriacus flower—national flower of South Korea—its name stems from the Korean word mugung, meaning ‘eternity’ or ‘inexhaustible abundance’. The shape of the Golden Wattle of Australia, our own national flower. The granite from Gapyeong, the bluestone rock (basalt) from the Maribyrnong area – all coming together in a ‘Bridge between two Nations’.

Permissions

All Figures are original by the authors, so no permissions are required.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The data presented in this study is available on request from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Blair Kuys

Professor Blair Kuys is the Dean of the School of Design and Architecture at Swinburne University of Technology. He graduated from Swinburne in 2003 with a Bachelor of Design (Industrial Design) (Honours) and worked as a furniture designer until returning to Swinburne to complete his PhD in 2010. He is now an active researcher who is instrumental in embedding industrial design research, theories and practice in traditional manufacturing fields to sustain and grow productivity. He has been awarded over AU$15M of research income, has 22 products go to market, and won three consecutive Good Design Awards for his products with Atlite Skylights (2018, 2019 and 2020). He is also the recipient of seven Vice-Chancellor’s Awards which is the highest accolade at Swinburne University of Technology.

Lisa M. Given

Professor Lisa M. Given, PhD, FASSA, is Director, Social Change Enabling Impact Platform and Professor of Information Sciences at RMIT University. Her interdisciplinary research in human information behaviour brings a critical, social research lens to studies of technology use and user-focused design. Her studies embed social change, focusing on diverse settings and populations, including in healthcare, workplaces, schools, and everyday life. A former President of the Association for Information Science and Technology, Prof Given is a Fellow of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia, and lead author of Looking for Information: Examining Research on How People Engage with Information (2023).

Jo Kuys

Dr Jo Kuys is the Course Director of Industrial Design at the School of Design and Architecture at Swinburne University of Technology, Australia. She holds a PhD from Swinburne University of Technology and a Master Degree from Monash University. Additionally, she earned a Bachelor’s Degree in Arts and Design, majoring in Transportation Design, from Hongik University in South Korea, and a Bachelor’s Degree in Science from the Art Institute of Fort Lauderdale, USA. Her PhD topic was on developing electric bus systems in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Before joining Swinburne University in 2010, Dr Kuys gained extensive industry experience as an automotive designer. She worked with Hyundai/Kia Motors in South Korea and GM Holden in Australia, where she contributed to various global automotive projects. Her diverse educational background and professional experience bring a wealth of knowledge and expertise to her role, fostering innovation and excellence in the field of industrial design research.

Simon Jackson

Dr Simon Jackson teaches the history of design at the School of Design and Architecture, Swinburne University of Technology in Melbourne, Australia. Simon has published articles in Design Issues, Journal of Design History, Journal of Design Research and Scandinavian Journal of Design History. He has been interviewed on ABC radio about design issues, and appears on a video entitled Social and Ethical Issues in Design and Technology. Simon is an authority on Australian industrial design history and has supervised over 40 PhD candidates to successful completion.

References

- Ackerman, E., & Ballou, J. (2023). A memorial to the war on terror is coming. Here is why you should care. The Washington Post September 25.

- Anderson, D., Storksdieck, M., & Spock, M. (2007). Understanding the long-term impacts of museum experiences. In J. H. Falk, L. Dierking, & S. Foutz (Eds.), In principle, in practice: Museums as learning institutions (pp. 197–215). Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

- Ashby, M., & Johnson, K. (2010). Materials and design. The art and science of material selection in product design. Oxford, UK: Elsevier Ltd.

- Ashby, M., Bréchet, Y., Cebon, D., & Salvo, L. (2004). Selection strategies for materials and processes. Materials & Design, 25(1), 51–67. doi:10.1016/S0261-3069(03)00159-6

- Beckstead, Z., Twose, G., Levesque-Gottlieb, E., & Rizzo, J. (2011). Collective remembering through the materiality and organization of war memorials. Journal of Material Culture, 16(2), 193–213. doi:10.1177/1359183511401494

- Burns, R. B. (1997). Introduction to research methods (3rd ed.). Australia: Addison Wesley Longman.

- Chadwick, C. (1971). Symbolism. The critical idiom reissued. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Collins, H., Allsopp, K., Arvanitis, K., Chitsabesan, P., & French, P. (2020). Psychological impact of spontaneous memorials: A narrative review. Psychological Trauma: theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 14(7), 1230–1236. doi:10.1037/tra0000565

- Cox, B. K. (2016). A personal reflection on the nature and value of public memory in holocaust memorials. Conversations: A Graduate Student Journal of the Humanities, Social Sciences, and Theology, 3(1)1. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/conversations/vol3/iss1/1.

- Doss, E. (2010). Memorial mania: Public feeling in America. London: University of Chicago Press.

- Dustin, D. L., Bricker, K. S., & Schwab, K. A. (2010). People and nature: Toward an ecological model of health promotion. Leisure Sciences, 32(1), 3–14. doi:10.1080/01490400903430772

- Falk, J. H., & Dierking, L. D. (2000). Documenting learning from museums. In J. Falk & L. Dierking (Eds.), Learning from museums: Visitor experience and the making of meaning. New York, NY: Alta Mira Press.

- Forty, A., & Küchler, S. (1999). In the art of forgetting. Oxford, UK: Berg.

- Given, L. M. (2008). The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. California: Sage Publications.

- Given, L., & Kuys, B. (2022). Memorial design as information creation: Honoring the past through co-production of an informing aesthetic. Library & Information Science Research, 44(3), 101176. doi:10.1016/j.lisr.2022.101176

- Gurler, E. E., & Ozer, B. (2013). The effects of public memorials on social memory and urban identity. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 82, 858–863. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.361

- Hundley, A. (2013). Restorative memorials: improving mental health by re-minding. Master of Landscape Architecture Department of Landscape Architecture | Regional and Community Planning. College of Architecture, Planning and Design. Kansas State University.

- Karana, E., Hekkert, P., & Kandachar, P. (2010). A tool for meaning driven materials selection. Materials & Design, 31(6), 2932–2941. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2009.12.021

- Kembaren, P., Simatupang, T. M., Larso, D., & Wiyancoko, D. (2014). Design driven innovation practices in design-preneur led creative industry. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation, 9(3), 91–105. doi:10.4067/S0718-27242014000300007

- Kimbell, L. (2011). Rethinking design thinking: Part I. Design and Culture, 3(3), 285–306. doi:10.2752/175470811X13071166525216

- Kleinsmann, M., Valkenburg, R., & Buijs, J. (2007). Why do(n’t) actors in collaborative design understand each other? An empirical study towards a better understanding of collaborative design. CoDesign, 3(1), 59–73. doi:10.1080/15710880601170875

- Lee, Y. (2008). Design participation tactics: The challenges and new roles for designers in the co-design process. CoDesign, 4(1), 31–50. doi:10.1080/15710880701875613

- Li, Y., Wang, J., Li, X., & Zhao, W. (2007). Design creativity in product innovation. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 33(3-4), 213–222. doi:10.1007/s00170-006-0457-y

- Lyu, F. (2019). Architecture as spatial storytelling: Mediating human knowledge of the world, humans and architecture. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 8(3), 275–283. doi:10.1016/j.foar.2019.05.002

- MacDonald, S. (2006). Words in stone? Agency and identity in a Nazi landscape. Journal of Material Culture, 11(1-2), 105–126. doi:10.1177/1359183506063015

- Mackenzie, S. P. (2013). The Imjin and Kapyong battles Korea, 1951. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Madden, D., Cadet-James, Y., Atkinson, I., & Lui, F. W. (2014). Probes and prototypes: A participatory action research approach to codesign. CoDesign, 10(1), 31–45. doi:10.1080/15710882.2014.881884

- Maple, M., Edwards, H. E., Minichiello, V., & Plummer, D. (2013). Still part of the family: The importance of physical, emotional and spiritual memorial places and spaces for parents bereaved through the suicide death of their son or daughter. Mortality, 18(1), 54–71. doi:10.1080/13576275.2012.755158

- Margry, P., & Sánchez-Carretero, C. (2011). Rethinking memorialization: The concept of grassroots memorials. In P. Margry, & C. Sánchez- Carretero (Eds.), Grassroots memorials: The politics of memorializing traumatic. USA: Berghahn Books.

- Matray, J. I. (2011). The Korean war: A history. Journal of American History, 98(1), 250–250. doi:10.1093/jahist/jar164

- Mayer, M. M. (2005). Bridging the theory-practice divide in contemporary art museum education. Art Education, 58(2), 13–17. doi:10.1080/00043125.2005.11651530

- Mercer, J. (2013). Emotion and strategy in the Korean War. International Organization, 67(2), 221–252. doi:10.1017/S0020818313000015

- Muller, M., & Druin, A. (2012). Participatory design: The third space in human-computer interaction. In J. Jacko (Ed.), Human computer interaction handbook: Fundamentals, evolving technologies, and emerging applications (3rd ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Naaranoja, M., Kähkönen, K., & Keinänen, M. (2014). Construction Projects as research objects – different research approaches and possibilities. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 119, 237–246. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.028

- Paay, J., Kuys, B., & Taffe, S. (2021). Innovating product design through university-industry collaboration: Codesigning a bushfire rated skylight. Design Studies, 76, 101031. 10.1016/j.destud.2021.101031

- Pedersen, S. (2020). Staging negotiation spaces: A co-design framework. Design Studies, 68, 58–81. 10.1016/j.destud.2021.101031

- Porter, A. (2002). The dynamics of death: Ancestors, pastoralism, and the origins of a third-millennium city in syria. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, (325), 1–36. doi:10.2307/1357712

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2012). Research methods for business students (5th ed.). Prentice Hall, NJ: Pearson Education Limited,

- Savage Kirk. (2009). Monument wars: Washington, D.C., the national mall, and the transformation of the memorial landscape. Berkeley, LA: University of California Press.

- Sienkiewicz, N. (2015). Creating meaningful experiences in art museums. In D. Anderson, A.D. Cosson, & L. McIntosh, (Eds.), Research informing the practice of museum educators. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers. doi:10.1007/978-94-6300-238-7_17

- Stevens, Q. (2014). Shaping moral landscapes: Comparing the regulation of public memorials in democratic capitals. In M. Gjerde & E. Petrovic, (Eds.), Landscapes and ecologies of urban and planning history, proceedings of the 12th Australasian urban history/planning history conference, Wellington NZ.

- Stevens, Q., & Sumartojo, S. (2015). Memorial planning in London. Journal of Urban Design, 20(5), 615–635. doi:10.1080/13574809.2015.1071655

- Stevens, Q., & Sumartojo, S. (2019). Shaping Seoul’s memories: the co-evolution of memorials, national identity, democracy and urban space in South Korea’s capital city. Journal of Urban Design, 24(5), 757–777. doi:10.1080/13574809.2018.1525288

- Stevens, Q., Franck, K., & Fazakerley, R. (2012). Counter-monuments: The Anti-monumental and the Dialogic. The Journal of Architecture, 17(6), 951–972. doi:10.1080/13602365.2012.746035

- Stueck, W. (2010). The Korean War. In M.P. Leffler & O. A. Westad (Eds.), The Cambridge History of the: Cold War Volume I: Origins. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Till, K. (2005). The New Berlin: Memory, politics, place. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Vergun, D. (2023). Five Korean war ‘firsts’ had lasting impacts. U.S. Department of Defence. Retrieved from https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3483261/five-korean-war-firsts-had-lasting-impacts/.

- Wagoner, B. (2017). The Constructive mind: Bartlett’s psychology in reconstruction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Wagoner, B., & Brescó, I. (2022). Memorials as healing places: A matrix for bridging material design and visitor experience. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6711. doi:10.3390/ijerph19116711

- Xiao, A., Park, S., & Freiheit, T. (2011). A comparison of concept selection in concept scoring and axiomatic design methods. Proceedings of the Canadian Engineering Education Association (CEEA), University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba, July 22–24, 2007. doi:10.24908/pceea.v0i0.3769