ABSTRACT

The late twelfth–early thirteenth-century Fedderate Charter gives a unique view of aspects of the thirteenth-century landscape of North-east Scotland that is not available from other sources. It is a multi-purpose document shedding light on agricultural, economic and social change, landscape and place-name development, secular religious observance and routeways. The method employed to describe the boundary of the estate is also unusual and may relate to the size of the grant and customary methods of witnessing such events.

INTRODUCTION

North-east Scotland is bedevilled by a lack of documentary evidence prior to the mid-sixteenth century. There are only two thirteenth-century charters relating to the Earldom of Buchan that include detailed boundary descriptions: the Fedderate Charter (Coll. AB, 407–8, transcript made from an engraved facsimile of the original in the charter chest at Pitfour) and that relating to a grant of lands for the founding of Turriff Hospital (REA, i, 30–4). With some minor exceptions, this paper will restrict itself to a consideration of the detail of the boundary clauses of the Fedderate Charter. A consideration of the information contained within the witness list and other parts of the document do not directly relate to landscape issues and will be ignored for the purposes of this paper. These descriptions are important in helping to shed light on a number of aspects of the landscape development of North-east Scotland that have left few traces in documentary or archaeological sources. That one short description can reveal so much demonstrates the real paucity of evidence for this important period of socio-economic change in the region.

The description of the bounds is quite eccentric and requires a degree of unravelling, especially because a number of the place-names are no longer extant and a number of locations appear to repeat at different points around the boundary. This is clearly impossible. A regionally rare example of a reference to a ‘healing’ or ‘doctor’s’ cross — Crucem Medici — locates a type of site that was ‘culturally cleansed’ from the area by the iconoclasm of the Reformation. Its position may, however, be denoted on a seventeenth-century map made by Timothy Pont and possibly ‘edited’ by Robert Gordon of Straloch — an early geographer with Catholic sympathies. References to sheepfolds on the uplands above the Burn of Gight give evidence for the importance of sheep farming to the North-east, otherwise only attested from tithe and customs accounts. Finally, the inclusion of references to fords and the ‘high road’ — viam altam — may enable suggestions to be made concerning those routes and surviving stretches of pre-nineteenth-century roads.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

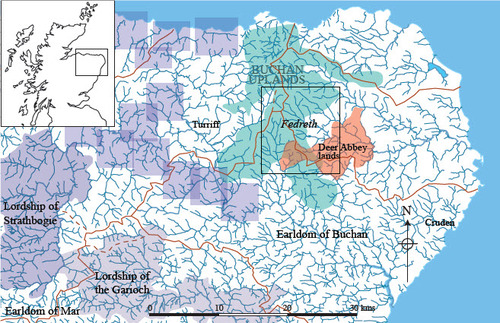

The second half of the twelfth century was a period of renewed royal interest in the region (Stringer Citation1985, pp. 33–5). A series of royal burghs was created that ran along the north coast from Banff to Inverness. The Lordship of Strathbogie had been placed in the safe hands of one of the younger sons of the Earl of Fife and William the Lion created the Regality of the Garioch for his brother David, Earl of Huntingdon (ibid.). These two new royal creations divided the former three great earldoms (formerly ‘mormaerdoms’) of Moray, Buchan and Mar from each other (see ). Royal control was further underpinned by the establishment of a Diocesan centre at Aberdeen (Dransart Citation2016, pp. 64–5). Much of the area was dominated by royal forest lands and thanages, the backgrounds to which are still in doubt (Evans Citation2019, pp. 23–5). What is not in doubt is that this was a period of dramatic political change across the region that heralded accompanying social change throughout the thirteenth century.

Fig. 1. Location plan showing Fedreth, the Buchan uplands and various land-holdings mentioned in the text. The mauve rectangles depict royal thanages and the brown lines are watersheds.

The Fedderate grant was made by Fergus, last native earl of Buchan, to John son of Uhtred, and consisted of three ‘davachs’ of Fedreth (Fedderate) in exchange for lands at Crudan (Cruden) and Slanys (Slains). (There are many variations of the spelling for this word; ‘davach’ is used here. It relates to an area of ground of indeterminate size though, anecdotally, in the region of 400 acres: Macdonald Citation1891, p. 78). On the death of Fergus in 1214, the earldom passed to William Comyn through his marriage to Fergus’ daughter Margery. This seems to have been a politically motivated move by King William to help consolidate royal power in the North-east. However, Fergus’ son, Adam, appears to have acquiesced, as he witnessed a number of subsequent charters made by William Comyn. This charter cannot post-date 1214 — the date of the death of Fergus — but might be as early as 1204 (www.poms.ac.uk/).

McNeill and MacQueen (Citation1996, pp. 242–4) have graphically demonstrated the high value of Aberdeen’s wool exports during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries compared to other products, and Campbell has drawn attention to the extraordinary value of these on a national scale (2008, pp. 915–6, 933–6). In other words, the North-east of Scotland became an important producer of wool and was integrated with the international trading of those products through the Flemish ports (Stevenson Citation1982). Analysis of ecclesiastical tithe records appears to indicate that a core area for this productive capacity lay within the central Buchan uplands (Shepherd Citation2021). The estate of Fedderate lay on the eastern side of this zone.

DEFINING THE ESTATE

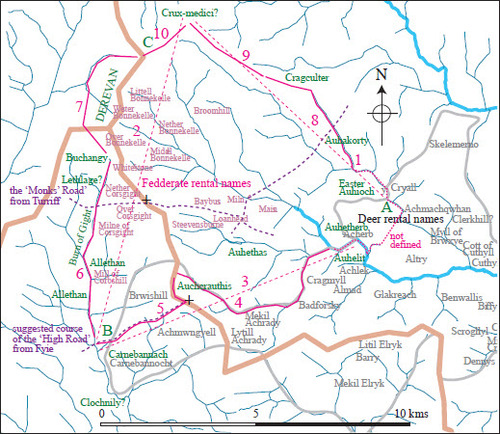

At first reading, the boundary does not make geographical sense. It does not follow the usual formula: A to B, B to C, etc. before returning to A. The first three defining clauses give a generalised overview of the estate. Number 1 gives the start and finish points up the east side; number 2 gives the western edge; number 3 defines the southern line. As the estate conforms to a roughly triangular shape, these three clauses provide a good overview (see ).

Fig. 2. Plan of the boundary clauses appearing in the Fedderate Charter. The dotted red lines show the introductory ‘overview’ clauses 1–3 whilst the solid red lines show the subsequent clauses. Names in green are those given in the description with other names being contained within the respective rentals of Deer Abbey, 1544 (Illus. AB, iv, 19–29) and Fedderate, 1690 (Illus. AB, ii, 442–444). Grey line denotes the presumed limit of Deer Abbey lands and the broad, orange line shows the major watersheds. Dotted purple lines mark the suggested route of the ‘High Road’ and other suggested cross-country routes.

The clauses from number 4 then become more specific but, confusingly, do not return to the start point for number 1. Instead, numbers 4 and 5 add detail to the southern boundary, ending up at the Burn of Gight — the endpoint of number 3. Clauses 6 and 7 add detail to the western side of the estate whilst clauses 8 to 10 return to the original start point to add detail to clause 1. A possible reason for this eccentric boundary definition will be considered below, after a closer look at the wording. (Original spellings are italicised with the modern equivalents, where they exist, given in plain type. Tocher’s translation of the charter (1910, pp. 135–6) has been used along with a few amendments suggested by the author).

1. ‘ … running on the eastern side of Easter Auhioch in the east, unto the hollow foss on the western border of the hill of Derevan in the west‘

… currente ex parte orientalide Ester Auhioch in oriente vsque ad fossam concauam ex occidentali costa montis de Derevan in occidente

This is the generalised view of the eastern march extending from Easter Aucheoch to the west side of the Hill of Derevan. Easter Aucheoch is fairly safe and still survives in farm names. Easter Aucheoch is probably modern Little Aucheoch. The name ‘Derevan’ has been lost but, with reference to the subsequent boundary information in the charter, would appear to be the high ground where the watersheds of the Ythan, Deveron and Ugie meet. Whether there is any connection between this major hill mass at the west end of the parish of Deer and that place-name itself is intriguing but is suggested by Taylor, who also notes a link with Welsh derw ‘oak’ (Taylor Citation2008, p. 276). The ‘hollow fosse’ may be a small valley lying between the main watershed and a lower ridge to the west but is more likely simply to be a small watercourse.

2. ‘and between the high road above Clochnily as it is extended in the south unto the crucem-medici in the north’

et inter viam altam supra Clochnily sicut extenditur in austro vsque ad Crucem Medici in aquilone

The location of neither of these two places is now known. This generalised western march places the healing cross near the northern point of Fedderate — far removed from its accepted site at Grassiehill (Canmore site number NJ95SW14; Forsyth Citation2008, pp. 413–14). This siting may, however, coincide with one of the annotated hilltop crosses to be found on two of the late sixteenth-century Pont maps that depict the region (see below). These two sites can only be understood by a consideration of the rest of the boundary clauses.

3. ‘and again (… ndo) in the east from the ford of the rivulet of Huskethuire between Auhelit and Auhetherb unto the rivulet of Gight in the west’

et iterum … ndo in oriente a vado riuuli de Huskethuire inter Auhelit et Auhitherb vsque riuulum de Giht in occidente

This is the generalised southern march. Auhetherb is modern Atherb, but Auhelit and Huskethuire are lost. However, as Atherb is bounded by Aucheoch to the north-east, it seems likely that Auhelit lay across the South Ugie Water to the south-west. This would require Huskethuire to be equatable with the South Ugie, which is not a problem as that river is not named elsewhere along the boundary. The Burn (rivulet) of Gight is recognisable as The Little Water that runs south to join the Ythan at Gight and provided the boundary between the medieval parishes of Turriff and Deer.

Thereafter follows the more specific descriptions.

4. ‘and in the foresaid east from the rivulet between the two Auhcrauthis unto the said rivulet of Gight under the (sheep)fold of Ruthrus Mac Oan of Allethan in the west’

et in predicto oriente a … li inter duas Auhcrauthis vsgue in dictum riuulum de Giht subter ouili Ruthri Mac Oan de Allethan in occidente

The two Auchcrathis may refer to the split Auchreddie fermtoun. However, that would appear to require the northern one to have subsequently migrated south of the burn to its present position. This contention is supported below. To the west lay the lands of the present Allathan, still straddling the Gight Burn.

5. ‘and proceeding (… do) between the said folds of the horsemen (or the horsefolds) towards the south unto the foresaid high road above Clochnily’

et progrediendo … do inter dicta ouilia equitum versus austrum vsque ad predictam viam altam supra Clochnuly

The boundary is said to turn south to the High Road. Again, we have no idea where the High Road is but regression from the nineteenth-century Ordnance Survey map suggests the route shown on . Fortunately, the following clause indicates that the boundary lies north of Cairnbanno, which is still extant.

6. ‘and also from a great foss hard by the adjacent town of Carnebennach on the north western side extending along the rivulet of Gight unto the junction … of Lethlage … in the north’

et etiam a fossa magna propinquius adiecente ville de Carnebennach ex parte aquilonali occidentaliter in riuulum de Giht vsque [a]d concursum … . de Lethalge . . n aquilone

This clause is very pleasing as it signifies a simple line up the Burn of Gight, though Lethlage is now lost.

7. ‘and so by the hollow foss called Holleresky Lech which lies between Buchangy and the hill of Derevan under the western part of Derevan’

et sicut fossa concaua que dicitur Holleresky Lech iacet inter Buchangy et montem de De … n sub occidentali parte de Derevan

Buchangy would appear to be the present Balthangie and the Holleresky Lech may well be the saddle crossing the watershed to the western part of Derevan. This, therefore, defines Derevan for us as the high point of the watershed that, strangely, does not appear to possess a unique modern place-name.

8. ‘and so from the foss of the hollow ford of Auhakorty on the western side unto the northern border of Cragculter’

et sic a vadi vadi concaui de Auhakorty ex parte occidentali vsque costam aquilonalem de Cragcultyr

Without warning, the description reverts to the south-east corner of the estate. Auhakorty would appear to be modern Auchorthie (presumably another achadh coirthe ‘field of the stone’ name) that adjoins Aucheoch on its north-eastern side. Craigculter still stands on the east side of the Leeches Burn, north-west of Auchorthie, but bounded on the north-east by a lesser burn. This may be the feature referred to as the foss (see below for discussion)

9. ‘and from Cragculter unto the foresaid crucemmedici’

et de Cragcultyr vsque ad predictam Crucem Medici

Then follows what appears to be a simple march up to the site of the healing cross. Grassiehill lies between the Auchorthie ford and Craigculter so cannot possibly be the site of the cross. It will be argued below that the cross may well have been set on the Hill of Turlundie — perhaps the highest point on the estate boundary.

10. ‘and … from the cruce itself unto the northern border of Derevan’

Et … de ipsa Cruce vsque in costam aquilonalem de Derevan

The final clause completes the circuit to the north side of Derevan.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SOCIAL AND LANDSCAPE CHANGE IN THE NORTH-EAST

The nature of the grant has landscape implications. The three davachs noted in the grant represent an exchange for what are presently lower-lying, rich arable lands near the coast (Slains and Cruden) in return for uplands of less arable value. However, John does appear to have retained his lands of Ardindrach, also in the vicinity of Cruden. He seems, therefore, to have been diversifying his agricultural portfolio to include a greater amount of upland pasture whilst also, perhaps, taking over a prestigious estate.

The grant covered the three davachs of Estir Auhioch, Auhetherb and Auhethas plus the otherwise unknown Conwiltes. The first survives as the farm names containing Aucheoch: Auhetherb should probably be viewed as Atherb and Auhethas does not appear to have a modern equivalent, though a corruption resulting in Achleck/Affleck is not impossible. These three places lie next to each other, north to south, at the confluence of tributaries of the South Ugie Water. It is not out of the question — though I do not have the linguistic abilities to pronounce on this — that these names were originally Pictish ‘aber’ names, subsequently gaelicised to ‘achadh’ names.

It seems likely that this charter references the former re-ordering of three earlier davach estates into one larger holding and that each of the estates was based upon one of the three tributaries. Such long estates are found elsewhere in the North-east (as well as elsewhere across Britain) and gave to each estate a broad spectrum of ecological zones.

The final boundary clauses (8–10) strongly suggest that the line from Craigculter lay along the watershed dividing the upper reaches of the North Ugie from the South Ugie. Presumably, the watersheds between the South Ugie tributaries separated the three davachs from each other. The southern march of Auhelit appears to have been defined by a burn, possibly because there is no distinctive east–west watershed along that part of the boundary. The boundary then crossed the major watershed between the Ythan and the Ugie to descend to the Burn of Gight. Perhaps the east bank of the Gight and the back of Derevan was the area described as Conwiltes. It does appear to have been an additional zone tacked onto the three former davachs and it may be suggested that this formed an engrossment of former ‘common’ upland pastures. A second suggestion may be that it is a garbled latin term related to convallia — valleys — though the geographical outcome may, therefore, be the same.

The incidental reference to the sheepfold (ouili) of Ruthri Mac Oan is useful. It has been argued elsewhere that the central uplands of Buchan was an important area for sheep production in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries and that the valley of the Gight was a distinct area of early agricultural intervention into these uplands (Shepherd Citation2021). This charter reference would appear to support that suggestion and indicates some measure of sheep farming in the early years of the thirteenth century or the latter years of the preceding century. The second ‘fold’ reference is more difficult though the word ouilia suggests more than one fold. Whether these are folds belonging to the horsemen — as suggested by Tocher (Citation1910) — or folds for horses as well as sheep is, perhaps, a moot point.

Finally, with regard to landscape change, the fermtoun of Atherb appears in the sixteenth-century Deer rental (Illus. AB, iv, 19–29) as one of the abbey’s holdings. Similarly, Achlek (Affleck) also appears there, which, as noted above, may relate to the charter’s Auhelit. By this time, the centralised core of the estate (comprising the three original davachs) lay at Fedderate, which lies up the valley of the central tributary. The name Fedreth is used within the charter as a collective term for the three davachs. This indicates that there was an element of retrospection within the charter and that these three units had already become amalgamated, as noted by Taylor (Citation2008, pp. 277–8). It appears that the lowest-lying parts of two of the three davachs — Auhetherb and Auhethas — were subsequently relinquished to Deer Abbey. At what date this occurred is unknown.

RECORDING THE BOUNDARY

The way the boundary is described is interesting. It does not follow a common A to B formula that eventually returns to A after a complete circuit of the grounds. Instead, an initial overview consisting of clauses 1 to 3 is followed by a clockwise progression along the south and west marches from ‘A’ through ‘B’ to ‘C’ before a new itinerary adds ‘A’ to ‘C’ in an anti-clockwise direction. Tucker (Citation2019, p. 155) draws attention to the development of different methods used for defining boundaries in charters and how those utilising a circular route became most dominant across Britain generally. The first clauses of the Fedderate charter appear to make use of compass directions in association with ‘X’ to ‘Y’ or ‘as far as ‘Z’. The last two are common devices within the Book of Deer land grants (ibid., p. 162). Whilst complete circuits occur less frequently in Scottish charters than linear portions (p. 168), in the Book of Llandaf, a whole range of options were utilised (ibid., p. 155). The Fedderate charter appears, therefore, to be an amalgam of such a range of options, utilising compass directions, ‘X’ to ‘Y’ limits and semi-perambulatory clauses.

Quite why such a method was employed here is interesting to consider. The estate was quite large —approximately 10 km east to west and similar north to south. Neville (Citation2012, p. 53) draws attention to the importance of perambulating boundaries both in Anglo-Norman-settled as well as gaelicised parts of the realm. She also notes the importance of ‘venerable and old’ men in the transmission of boundary knowledge (ibid., p. 44). It is unlikely, given the size of the estate, that such venerable witnesses could be found who knew the entirety of the bounds. The bounds were those pertaining to the north side of Aucheoch and the south (and possibly west) side of Auhethas. The two groupings of boundary descriptions may, therefore, pertain to two distinct groups of witnesses.

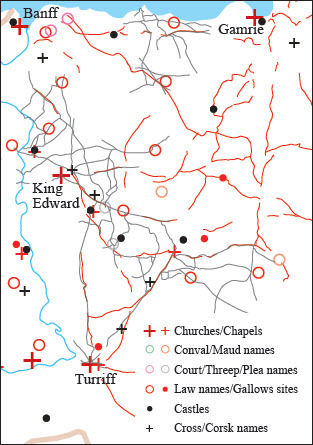

DISTINCTIVE LANDSCAPE FEATURES

As well as the sheep- (and possibly horse) folds, two other distinctive landscape features are noted: the ‘High Road’ and the ‘Crucem Medici’. The High Road would appear to be a major route linking Fyvie (the caput of the thanage of Formartine) with Deer and other comital bases around the North-east coast. The suggested route has been determined by regressing the 1st-edition Ordnance Survey map by eliminating all sections of road that are clearly of ‘improvement’-era or later. This method was then cross-checked with an area around Kingedward that has a good area coverage of eighteenth-century estate plans showing the landscape in its pre-industrialised form (see ). The coincidence of roads extrapolated from regressing the OS maps and the documented pre-modern routes appears to confirm that this is a reasonable method of reconstructing routeways. Clearly, it is not possible to say a suggested pattern belongs to any particular period. But, when a reconstructed route coincides with a fragment of documentary evidence, the likelihood of it being a significant correlation must be considered to be fairly high. In this case, the route crosses the watershed at Corsehill (Cross Hill), depicted on by the lower black cross. This may be significant because, as Forsyth (Citation2008, p. 402) points out, Simon Taylor suggests the place-name Cairnbanno may attest the site of the ‘cairn of blessing’ marking the site of Colum Cille’s mythological blessing. The route crosses the Gight Burn at Abbotshaugh (below Maryhill) and ascends the Slacks of Cairnbanno to Corsehill. Forsyth points up the importance of this entry point to the lands of Deer.

Fig. 3. Routeways re-drawn from a series of eighteenth-century estate plans (in grey) overlain with the pre-modern routeways suggested from the 1st-edition OS map (in red).

The upper cross on shows the site of another ‘cross’ name — that of ‘Corse of Gight’. Although not recorded in this charter, the reconstructed route of the ‘Monks’ Road’, recorded on the Turriff Hospital charter (REA, i, 30–4), crosses the watershed at the Corse of Gight. Presumably, the road earned its name by linking the two abbeys of Turriff and Deer. It is unlikely to be a coincidence that the two routes intersect at the centre of the Fedderate estate or, otherwise, that the caput was developed at this intersection. It should be noted that, although it is not known whether wayside crosses stood at these passes, this must be viewed as a distinct possibility. Other upland routes crossing precarious landscapes, such as across Dartmoor (see Fleming Citation2011), were furnished with such markers and apotropaic symbols and Evans draws attention to the probable use of way-marker crosses in relation to the monastery at Portmahomack (2019, p. 165).

The second distinctive feature is the enigmatic ‘Crucem Medici’. As noted above, this has been considered to have lain in the vicinity of Grassiehill, but the evidence for this is equivocal. Forsyth (Citation2008, pp. 413–14) draws attention to the presence of fragments of sculpture from a cross unearthed in the vicinity in 1848. This was, apparently, found near the site of a bridge carrying a projected line of the High Road as it exited the lands of Deer. This is extremely interesting considering the evidence regarding the western entry of this road into the abbey’s lands. However, this fragment might not be from the Crucem Medici.

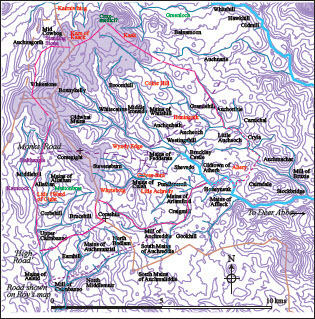

An earlier paper (Shepherd Citation2016) drew attention to a number of hitherto unremarked crosses, possibly inscribed by Robert Gordon of Straloch working from one of Timothy Pont’s maps of Formartine (NLS, MS.70.2.10 [Gordon 32]). The Pont map covering this area does not appear to be in the NLS collection. A further two crosses and one ‘pillar’ appear on Pont’s map (MS.70.2.9 [Pont 10]) but not on Robert Gordon’s redrawn plan (NLS, MS.70.2.10 [Gordon 33]). The northernmost, in the vicinity of modern New Pitsligo, is the one to be considered here. Another, unfortunately unrecognisable, mark is shown by the name ‘Greeshahil’. This is also clearly of interest considering Forsyth’s work (2008).

shows the crosses (circled) that appear on the Pont map of a part of Buchan drawn during the last quarter of the sixteenth century (ibid.). In 1581, at the request of the General Assembly of the Kirk, the Scottish parliament passed an act against those who visited ‘chapelles wellis and croces’. Severe financial penalties accrued to the first offence, death for the second (Walsham Citation2012, p. 106). This date is clearly of significance for the depiction of these crosses on Pont’s maps. Whilst the Formartine crosses were retained/inserted on Robert Gordon’s version of the Pont map (NLS, MS.70.2.10 [Gordon 32]) the Buchan ones were not (NLS, MS.70,2,10 [Gordon 33]). Its depiction, at around the date of an Act of the Scottish Parliament that prescribed death for visiting such places (admittedly, as a second offence) is interesting. Pont’s maps are generally believed to have been made after that Act and, consequently, these depictions may have been added by Robert Gordon rather than Pont himself. Pont was a member of the official kirk that had outlawed such idolatrous symbols. Robert Gordon of Straloch was a close confidant and relative of the staunch but pragmatic catholic George Gordon earl of Huntly (Grant Citation2010). However, he also acted as a go-between for the two warring factions and was able to accrue royal and ecclesiastical dispensations owing to the perceived national importance of his work (Stone Citation1981, p. 16). If Pont included the crosses, it might be wondered why he did so. Was it as a member of the Kirk engaged in routing out such symbols for their removal, or did Gordon include them as an act of symbolic religious piety? Both options remain possible. It should also be noted that the Covenanters, during the 1640s, were responsible for a further wave of iconoclasm and wanton destruction (Penny Dransart, pers. comm.). Over time these sites appear to have lost their symbolic meaning for the local population.

Fig. 4. Section of the Pont map of Buchan (MS.70.2.9 [Pont 10]) with the two crosses and one pillar circled. (Reproduced with the kind permission of the National Library of Scotland).

![Fig. 4. Section of the Pont map of Buchan (MS.70.2.9 [Pont 10]) with the two crosses and one pillar circled. (Reproduced with the kind permission of the National Library of Scotland).](/cms/asset/bd81be7b-2659-439f-a366-c59b608f47c4/rlsh_a_1999014_f0004_c.jpg)

With respect to trying to understand the locations of the High Road and the inscribed cross on a modern map, there are a number of good clues (see ). Although Pont’s map lacks spatial accuracy, the relative positioning of place-names with respect to the rivers and tributaries permit most of them to be placed over the modern map without too much difficulty. Only Huningnik (Honeyneuk) appears to be misplaced in the study area. With this additional information to hand, it is useful to review the charter evidence with respect to Clauses 4 and 5 that take the route from ‘the foresaid east from the rivulet between the two Auhcrauthis unto the said rivulet of Gight under the (sheep) fold of Ruthrus Mac Oan of Allethan in the west’ and ‘proceeding (… do) between the said folds of the horsemen (or the horse folds) towards the south unto the foresaid high road above Clochnily’.

Fig. 5. Details taken from the Pont map and applied to the modern map. Names in Black: from Pont; Purple names: extra detail from Roy’s Military map; Red names: names from Pont that are no longer extant; Light green names: descriptive names from the 1st-edition OS.

Both Pont and Gordon, on his amended map (NLS, MS.70,2,10 [Gordon 33]) show Little Achredy lying north of the Burn of Auchreddie and with a separate part lying to the south. This would appear to support the suggestion that the two Aucrathis either side of the rivulet are indeed the two Auchreddies. The suggestion made here is that the boundary ascended to the watershed, then turned south to Corsehill, where it met the High Road. However, the nineteenth-century recording of the name ‘Muttonbrae’, when taken alongside the references to the sheepfolds of Ruthrus Mac Oan, may indicate that the route may have simply crossed the saddle in the watershed and descended by the burn to the west, which does lead in a southern direction. This would indicate that the High Road as determined by the map regression is in the wrong place and should lay further north. The southern option also conflicts with the Deer Abbey rental which includes Brucehill within its holdings, though it has already been remarked that other lands along this southern boundary appear to have been transferred to the Abbey after the date of the Fedderate Charter. Roy’s map includes a southern routeway that runs along the base of a glen from Asleid to the Mill of Auchreddie. This would supply a suitable ‘Low Road’ to complement the ‘High Road’ to the north; the latter perhaps being more suited to winter travel when the lower route became too sticky. However, it would seem that this part of the Fedderate boundary must remain in some doubt.

In attempting to understand the landscape, the name ‘Kaak’ is intriguing. Both Pont and Gordon, with his local knowledge, place the fermtoun of Kaak between Balnamoon and Cairnwhinge. However, the modern farm name Cairncake lies in the vicinity of Roy’s Karncock. Pont places the Karn of Kaack — seemingly with its own cross on the summit — between and below his two Kairniwhing names and Kaak. Presumably, the Cairn of Kaack formed one summit of the hill mass known in the charter as Derevan. When the name Derevan fell out of use, it may have been replaced by Karn of Kaack (itself having subsequently disappeared from use), from which two separate fermtouns, either side of it, took their names. Clearly, this is speculative but may answer an interesting place-name riddle.

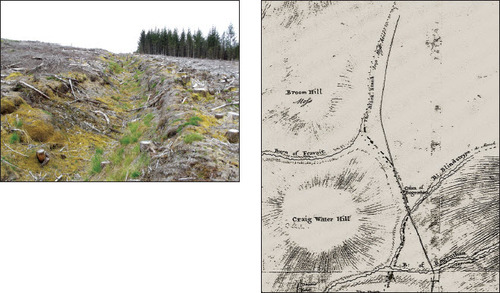

Another aspect of the description that warrants closer attention is the use of the word foss. In later Scottish documents the word often relates to man-made structures, such as in royal licences to fortify with ‘walls and ditches’ — muris et fossis — as in a mid-fifteenth-century example for Druminnor Castle (Illus., AB, iv, 400). However, this presumably does not negate the possibility of foss referring to a natural feature. Clause 7 speaks of the foss being known as ‘Holleresky Lech’, where lech appears to have the meaning of ‘small stream or runlet’ (DSL, dsl.ac.uk). However, man-made boundary ditches are also known from the region, such as that shown in below Craigwater Hill in the Clashindarroch Forest. The ditch there links two burns that form part of the boundary between the lands of the Duke of Gordon and Earl of Fife along the edge of the Clashindarroch Forest (FLS archaeology archive CLASH181). Clause 6 ‘(from a great foss hard by the adjacent town of Carnebennach)’ may refer to the bed of the Gight Burn but this would be surprising. In the Turriff charter, of a similar date, when the boundary runs along a substantial burn, the charter clearly states that fact. The reading of the Fedreth charter may suggest that in Clause 6 the word foss indicates a man-made boundary feature running parallel to the burn. If this portion of land was a later addition to the original three davachs, such an artificial boundary may well have been constructed to record that fact. In Clause 8 — ‘and so from the foss of the hollow ford of Auhakorty on the western side unto the northern border of Cragculter’ — a different explanation may be required as the burn apparently bounding Auchorthie on its western side does climb to enclose modern Craigculter on its northern edge. The burn is very slight and the use of foss in this instance may reflect the previous occasion when used to describe the, probably natural, Holleresky Lech.

Plate I. Man-made boundary ditch by Craigwater Hill in the Clashindarroch Forest. The ditch is shown as a dashed line on an eighteenth-century estate plan (RHP 2254), linking the Blindstrype to The Black Stank (Reproduced with the kind permission of the National Records of Scotland).

Returning to the enigmatic Crucem Medici, clause 9 states, ‘and from Cragculter unto the foresaid crucem medici’. Craigculter still survives as a farm on a ridge running south-eastwards down from the Hill of Turlundie. It is known from Clause 2 that the cross lay near or at the northern extremity of the estate. The Hill of Turlundie, especially its western end, appears to be topographically the most suitable site for the cross. Pont shows his hilltop cross as laying between Balnamoon and an area of water abutting Kairnwhing to the north-west and Kaak to the west. Only Balnamoon survives as a place-name. But the area of water may be suggested as lying in the vicinity of the appropriately named ‘Greenloch’, being an expanse of flat, low-lying land draining into the North Ugie Water at Whitehill. This is exactly as Pont shows it. Two possibilities present themselves. Firstly, that the cross was positioned on a small knoll shown to the east of Kaak on . This fits Pont’s depiction perfectly. However, it is difficult to see how the charter boundary, which generally followed natural features, could have coped with this erratic course. The final part of the route would have required a descent into a gulley before climbing to the Karn of Kaack. Were the boundary to have run gently up the ridge from Craigculter to the western top of the Hill of Turlundie, the cross may have sat upon that. Whether the Karn of Kaack also had some feature on its summit is unknown. But, that is how it appears on Pont’s plan and a small fermtoun recorded by Roy as near to both Cowbog and the line of the boundary bore the intriguing name of ‘Standing Stone’. This lies within the area of Auchnagorth and Corthie Moss — both apparently containing the gaelic coirthe element — ‘pillar, standing stone, menhir’ (Forsyth Citation2008, p. 398).

CONCLUSION

In an earlier paper (Shepherd Citation2016, p. 79), it was stated that, ‘The cross on the hill at Balnamoon appears to fit with no presently recognisable archaeological hill-top feature in the area’. The charter being considered here may suggest one particular possibility. It seems to undermine the notion that the Crucem Medici was positioned at Grassiehill, even if something else was. In broader terms, the Fedderate charter is a rare document for the North-east of Scotland and helps to record landscape change in an otherwise documentarily opaque period.

The document seems to record the amalgamation of three former davachs into one larger estate, though the charter appears to have been retrospective in this respect. The estate already possessed the singular term Fedreth by that time. Taylor notes the development from Pictish uotir — subsequently, ‘fetter’ and indicative of an important administrative or territorial unit (2008, pp. 277–8). The exchange of this upland estate for lower-lying land better suited to grain production indicates the development of a lucrative livestock industry. Documentary economic evidence for this development in the North-east has been noted by McNeill and MacQueen (Citation1996), Campbell (Citation2008) and, more recently, with more localised detail by the author (2021). This charter provides supporting evidence by way of the recorded land exchange as well as by the reference to the already-extant sheepfold(s) up the Burn of Gight.

A further portion of land — Conwiltes — suggests an engrossment of the former lands of the three davachs that most likely pertains to the east bank of the Burn of Gight. The southern march through fairly low-lying land appears to have utilised burns as lines of demarcation. The eastern march used a burn in the lower-lying reaches and then a minor watershed as it ascended. The western march also utilised a burn — the Burn of Gight — but, if this was additional land, as suggested by it not having formed a part of the earlier davachs, the former march is likely to have been along the line of the major watershed — the hill of Derevan. It is possible that this extension marked the engrossment of the Fedderate estate over former common pasturelands. This is most likely to have occurred as a result of the economic development of sheep farming in the area and the increased value of upland pastures. It should be borne in mind that most of these ‘uplands’ are now good agricultural lands — Grade 3 or above (see ). They were only relatively ‘uplands’ in comparison with the surrounding lands (see Shepherd Citation2021, for a lengthier discussion).

Plate II. View from Corse of Gight across the upper parts of the davachs of Fedreth towards the Hill of Turlundie in the distance.

The references to the ‘High Road’ also give a brief glint of light across the thirteenth-century landscape and help to suggest the approximate position of what was clearly an important cross-country route. Map regression and the reference to the ‘Monks’ Road’ in the Turriff charter appears to show them intersecting in the vicinity of the caput of Fedreth. Although little else can be said about them, any brief glimpse of such important landscape features in this opaque landscape is most welcome. And, finally, the possible identification of the Crucem Medici with a depiction on one of Pont’s maps is a reminder of what was lost during the iconoclasm of the Reformation and, whilst its location is still not clear, it seems fairly certain that it was nowhere near Grassiehill — even if a further important and now lost cross or way-marker stood at that point.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Penny Dransart for kindly reading and commenting upon a draft of this paper. Penny made a number of insightful suggestions that have all been acted upon. Also, grateful thanks to the anonymous referee who pointed me in the direction of additional literature that further helped in the understanding of this interesting document. All errors remain mine alone.

PRIMARY AND ONLINE SOURCES

- Coll. AB, Collections for a History of the Shires of Aberdeen and Banff, Spalding Club, Aberdeen, 1843.

- DSL, Dictionary of the Scots Language, https://dsl.ac.uk.

- FLS, Forestry and Land Scotland (formerly Forestry Commission Scotland).

- Illus., AB, Illustrations of the Topography and Antiquities of the Shires of Aberdeen and Banff, Spalding Club, Aberdeen, Vol. 1-4, 1847–1869.

- National Library of Scotland, NLS

- MS.70.2.9 (Pont 10), ‘A map of the coast of Buchan in Northeast Scotland’, c. 1583–96.

- MS.70.2.10 (Gordon 32) ‘Formarten and part of Marr and Buquhan’, 1630 x 1655.

- REA, Registrum Epicopatus Aberdonensis, Edinburgh, 1845.

- RHP 2254, Part of the Lordship of Huntly in the Parishes of Rhynie, Essie and Gairtly, 1776, National Records of Scotland.

- William Roy’s Military Map of Scotland, 1747–1755, National Library of Scotland. www.poms.ac.uk/record/source/2608/.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Campbell, B. M. S., 2008. ‘Benchmarking medieval economic development: England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland’, in Econ Hist Rev, 61, 4, pp. 896–945. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2007.00407.x

- Dransart, P., 2016. ‘Bishops’ palaces in the medieval dioceses of Aberdeen and Moray’, in Medieval Art, Architecture and Archaeology in the Dioceses of Aberdeen and Moray, ed. J. Geddes (Abingdon), pp. 58–81.

- Evans, N., 2019. ‘A historical Introduction to the Northern Picts”, in The King in the North, The Pictish Realms of Fortriu and Ce, ed. G. Noble & E. Evans (Edinburgh), pp. 10–38.

- Fleming, A., 2011. ‘The crossing of Dartmoor’, in Landscape Hist, 32 (1), pp. 27–45. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01433768.2011.10594650

- Forsyth, K. 2008. ‘The Stones of Deer’, in Studies on the Book of Deer, ed. Forsyth, pp. 398–438.

- Forsyth, K. (ed.), 2008. Studies on the Book of Deer (Dublin).

- Grant, R,. 2010. ‘George Gordon, Sixth Earl of Huntly and the Politics of the Counter-reformation in Scotland, 1581–1595’, unpubl Univ Edinburgh Ph.D. thesis.

- Macdonald, J., 1891. Place Names in Strathbogie (Aberdeen).

- McNeill, P. G. B., & MacQueen, H. L. 1996. Atlas of Scottish History to 1707 (Edinburgh).

- Neville, C. J., 2012. Land, Law and People in Medieval Scotland (Edinburgh).

- Shepherd, C., 2016. ‘Cartographic evidence for seventeenth-century “cross sites” in North-east Scotland: Robert Gordon of Straloch and the Blaeu Maps of Scotland’, in Landscape Hist, 37 (1), pp. 69–85. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01433768.2016.1176436

- Shepherd, C., 2021. ‘The Central Uplands of Buchan – a distinctive agricultural zone in the 13th Century: fact or fiction?’, Rural Hist, 32 (1), pp. 41–75. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0956793320000114

- Stevenson, A. W. K., 1982. ‘Trade between Scotland and the Low Countries in the later Middle Ages’, unpubl Univ Aberdeen Ph.D, thesis.

- Stone, J. C., 1981, ‘Robert Gordon of Straloch: cartographer or chorographer’, Innes Rev, 4, pp. 7–22.

- Stringer, K. J., 1985. Earl David of Huntingdon: a study in Anglo-Scottish history (Edinburgh).

- Taylor, S., 2008. ‘The toponymic landscape of the Gaelic notes in the Book of Deer’, in Studies on the Book of Deer, ed. Forsyth, pp. 275–308.

- Tocher, J. F., 1910. The Book of Buchan: a scientific treatise in six sections, on the natural history of Buchan, prehistoric man in Aberdeenshire, and the history of the North-East in ancient, medieval and modern times (Peterhead).

- Tucker, J., 2019. ‘Recording boundaries in Scottish charters in the 12th and 13th Centuries’, in Copper, Parchment and Stone. Studies in the sources for landholding and lordship in early medieval Bengal and medieval Scotland, ed. J. R. Davies, & S. Bhattacharya (Glasgow), pp. 151–92.

- Walsham, A., 2012. The Reformation of the Landscape: religion, identity and memory in early modern Britain and Ireland (Oxford).