ABSTRACT

Meadow land use has been the object of very limited historical research in Sweden, as most studies have focused on ecological or functional aspects. Research on the economy of meadows is rare. This paper addresses this issue by studying the investment in, and management of, meadows in seventeenth-century Sweden considering landesque capital, a concept referring to long-term investments in land through labour. We also examine the local economic institutions developed to handle this type of capital. By analysing seventeenth-century century court records from the districts of Östra, Redväg and Kind, a more complete picture emerges of the processes and contexts in which meadows were created, managed and devalued / revalued over time. Meadow capital was constantly under threat of degeneration due to biophysical processes, and this paper explores the different strategies used to handle this problem. Outlying meadows were often more flexible in terms of ownership and were often used by others when abandoned, either by agreement or surreptitiously, which frequently led to future ownership conflicts. The comparatively limited number of cases relating to meadows nonetheless emphasises the fairly low transaction costs incurred by institutions related to meadow land use at this time. It was often the outlying meadows that appeared in court proceedings, most likely related to these meadows not being contiguous to the rest of the land of the person using them as well as these meadows having a more dynamic owner/usership history compared to infield meadows.

INTRODUCTION

On November 18, 1630, a legal examination was performed of the flood meadows ‘Reppe maer’ in the parish of Norra Åsarp in western Sweden after protests from local farmers. The bailiff of the noblewoman Margareta Brahe had unlawfully mowed all the hay and brought it in for storage in his mistress’s homestead Lönnarp, to the detriment of the farms that originally held all the legal rights to these meadows. Margareta Brahe claimed that Reppe maer had originally been placed under the estate of Lönnarp, which was now in her possession. This was not, however, the first time that the ownership of these meadows had been disputed in a court proceeding. In 1617, the farmers owning the rights to Reppe maer were given a royal letter as proof of their rightful possession, which was shown to the court. Furthermore, no documents existed stating that these meadows belonged to the estate of Lönnarp. The court thus decided that Margareta Brahe had to return the hay to its rightful owners, who had the full legal rights to these meadows.Footnote1

The case above clearly indicates the important role that meadows played in the local economy during this period. A meadow in this context is defined as ‘grass (i.e. graminoid, including sedges) and /or herb-dominated land, with or without a sparse cover of trees and shrubs, which historically were managed for production of livestock fodder, hay’ (Eriksson Citation2020, p. 1). Hay was generally a vital resource in agriculture at the time and was used to feed domestic livestock kept in stalls during the winter, which in turn yielded manure in the spring for the intensively cultivated arable fields. In this region in particular, which had been involved in trade with animal products and oxen at least since the sixteenth century (Palm Citation1997), animals served an even more central economic function for the local farmers. The fact that Margareta Brahe tried to claim Reppe maer, which was a large meadow shared among several settlements in the area, reflects the nature of meadows as a form of capital that under certain circumstances was sought after and contested. Furthermore, meadows could potentially function by helping to increase production in order to yield surpluses.

This paper focuses on these economic aspects of seventeenth-century meadow land use in Sweden and analyses the ways in which meadows were handled in a local economic and institutional context. Previous research in agrarian history, human geography and archaeology has given considerable attention to arable land (view the summary in Hannerberg Citation1971; Pedersen et al. Citation1998; Myrdal Citation1999; Gadd Citation2000; Helmfrid Citation2000; Jupiter Citation2020). Different forms of division of land, such as solskifte, bolskifte and fritt stångfall, have been discussed together with regularities and irregularities in the dispersion of fields, furlongs and strips, as well as different taxation systems based on arable land (Dovring Citation1947; Ericsson Citation2012). The yearly rotation between fallow and sown fields and the origin of fixed fallow in different parts of Sweden and Denmark have been a focal point for research for a long time (Frandsen Citation1983; Jansson Citation1998, Citation2005; Vestbö-Franzén Citation2004).

Systematic studies are still lacking on meadows, which through their intimate relation to manure served as the basis of pre-industrial agriculture (see section ‘The Swedish Meadow’ below). Internationally, the study of historical meadow land use is currently on the rise (e.g. Lennartsson et al. Citation2016; Pearson & Soar Citation2018; Spulerova et al. Citation2019; Renes et al. Citation2019; Vázquez Citation2020). In Sweden, historical meadows have predominantly been studied in a practical or ecological sense as part of the agricultural system (e.g. Aronsson Citation1979; Ekstam et al. Citation1988; Lennartsson & Westin Citation2019) or through a focus on the origin and development of meadow land use (e.g. Eriksson Citation2020). Studies focusing on the economic role of meadows are far less common. Notable exceptions include studies of the colonisation of northern Sweden during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, where access to meadows along the major rivers has been seen as a fundamental factor (Campbell Citation1948; Frödin Citation1952). For earlier periods, studies have primarily focused on the role of meadows in agrarian expansion, settlement establishment and cattle husbandry (Sjöbeck Citation1947; Frödin Citation1954; Egerbladh Citation1987; Myrdal & Söderberg Citation1991, p. 495ff). These studies are also concentrated in eastern and northern Sweden. This paper, however, concerns areas and time periods in which the wider economic role of meadows remains unstudied, and it is our goal to contribute additional insights concerning such aspects of meadow land use in Sweden.

Our principal goal is therefore to investigate the primary economic characteristics of meadow land use in Sweden during the period from 1600–1670 through the use of historical-geographical source material. We have chosen to view the meadow as a landesque capital, i.e. a long-term investment in the form of labour and measures of improvement, with specific characteristics related to the specific conditions of this land use. We analyse the local economic institutions governing meadow land use and link these to the ways in which meadow capital was handled and circulated, showing how the meadow economy relates to a larger societal context. We also discuss the differences between types of meadows, as well as comparisons to other land uses, such as arable and swidden cultivation. A specific feature of meadow investments is temporality, which is explicitly analysed in this paper. Another goal is also to demonstrate how district court records in combination with large-scale cadastral maps can be used effectively in the historical study of meadows and landscape history in general.

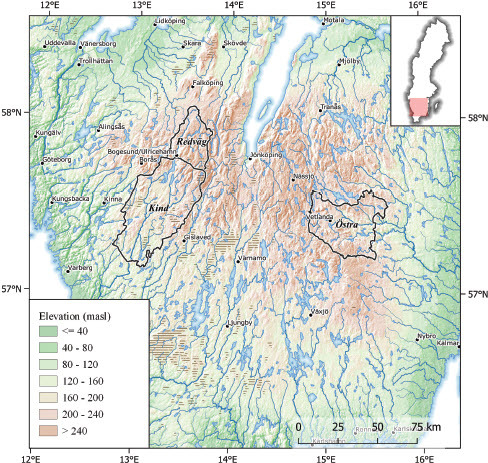

The areas chosen for this study consist of three districts (Sw. Härader) in southern Sweden: Kind, Redväg and Östra (). These areas do not represent the fully cultivated plains but rather the border zone between the plains and the forest (Redväg district) and the forest-dominated south Swedish uplands (Kind and Östra district). By analysing source material from these areas, however, we can find common patterns and traits that can be applied with validity over a larger area. These districts share many similar characteristics and are located in or on the margins of the region called the South Swedish uplands. They were all dominated by cattle farming in the medieval and early modern period and used an annual cropping system (with some three-course rotation in Östra), which was heavily reliant on manure. Meadows were, as a consequence, the basis of this agrarian system but yet have been the object of very limited previous research.

THE SWEDISH MEADOW

The history of meadows in Europe is tied to the history of stalling practices. A meadow is primarily a means to produce a surplus of fodder that can be used to feed animals that are often stalled during the winter (Mazoyer & Roudart Citation2006, p. 259ff). Stalling has also been closely tied to the establishment of permanent arable fields or an intensification of arable farming, where stalled animals would produce manure that was utilised for fertilisation (Pedersen & Widgren Citation2011, p. 48ff; Widgren Citation2012). Meadows are thus generally part of a system in which fodder, stalling and manured fields closely were interacting with each other. In 1663, the author Schering Rosenhane described the relationship between meadows and fields as ‘the meadow is the mother of arable land’ (Rosenhane Citation1944 [1663]; Lennartsson et al. Citation2016). It is thus well known that meadows were the basis of pre-modern northern European agricultural systems.

The collection of fodder for livestock in Sweden seems to have its roots in the Bronze Age (Eriksson Citation2020), whereas the stalling of animals (Petersson Citation2006) and the introduction of scythes for mowing are Iron Age phenomena (Myrdal Citation1982). A runic inscription on a whetstone from Norway dated to c. 500 a.d. describes how the whetstone is moistened in the hollowed horn filled with water and how the scythe then battles with the grass (Kolås Citation2012; Herschend Citation2020, pp. 82–5), clearly showing that the main components of meadow land use existed at this time. The origin of meadows created and maintained solely for the purpose of fodder collection in fixed places on the landscape is also revealed through pollen analysis. Such analyses reveal that the dating of successive clearings of the landscape, in which meadow indicators (herbs and grasses) are present, varies in the region of southern Sweden. While permanent meadows likely existed during the first centuries a.d. on the southern plains, the same process is reflected in the pollen samples around the time 1000–1200 a.d. in the uplands (Berglund et al. Citation2002).

In the early modern period, which is the focus of this study, meadows were an important part of all agricultural systems in Sweden. The economy was largely locally self-sufficient, and hay, in particular, was not sold on the market but intended exclusively for local use. The area covered by infield meadows varied depending on geographical context, being the lowest on the agricultural plains and largest in forested regions, especially in the north of the country (Eriksson Citation2020, p. 2). While in other countries, such as in England, meadows were usually found on floodplains or low-lying terrain (Williamson Citation2003, p. 163ff; Williamson Citation2012, p. 201ff; Mazoyer & Roudart Citation2006, pp. 272–3), but in Sweden, meadows were spread in wider geographical contexts. Apart from the hay produced on wet and dry meadows, leaves from coppiced trees were also used as animal fodder. It was not only the infields that were used for meadow lands. Outland grazing was extensive in Sweden, and other forms of forest use were common. In particular, wetlands in forests were often used as meadows, and areas cleared through swidden agriculture for grain cultivation were transitioned into meadows or grazing patches (Craelius Citation1986 [1774]; Lennartsson & Westin Citation2019, pp. 32–33). Such outlying and distant meadows were especially important in forest regions (Campbell Citation1948; Frödin Citation1952) but have also been an integrated part of the agricultural system in more transitional regions (e.g. Granlund Citation1969). Meadows in Sweden were consequently dynamic in character in relation to topography, location and land use practices.

APPROACHING THE MEADOW AS LANDESQUE CAPITAL

This paper uses the concepts of landesque capital and economic institutions to analyse the historical economic function of meadows. These concepts are used as tools to further the analysis and understand how the meadow economy fit into a wider societal context.

Landesque capital is a concept popularised and developed into a relational-geographical concept by Harold Brookfield in 1984 and has subsequently been used to analyse the ways in which human investments in land promote productivity in relation to political economy and capital circulation (Widgren & Håkansson Citation2014). The traditional definition of the concept refers to ‘any investment in land with an anticipated life well beyond that of the present crop, or crop cycle’ (Blaikie & Brookfield Citation1987, p. 9). Such investments, manifested in the form of anthropogenic soils, terraces, ditches, dykes or irrigation systems, are considered a form of fixed capital created through different forms of human labour and with long-lasting effects. However, it is not these features themselves that constitute this capital, which instead becomes capital only through ‘their economic relationship to prevailing economic and technological contexts’ (Widgren & Håkansson Citation2014, p. 10). This means that this capital can also be devalued if the context changes. Investments in landesque capital can be either systematic such as major transformations through large labour mobilisation or incremental, for example, through gradual changes that transform a landscape (ibid., pp. 16–17). Likewise, we can also argue that the process of devaluation may assume similar forms.

Landesque capital as a concept has been primarily deployed in studies of physical features, such as those relating to the movement /improvement of soils and the movement of stones. ‘Green’ landesque capital in the form of vegetation changes is less well conceptualised (Börjesson Citation2014). Börjesson argues that this leads to an underemphasis on incremental change, by which the work of farmers often has unintended effects, prompting further changes. We must therefore include ‘any investment […] that increases land capability through the moderation of local biophysical processes (ibid., p. 265)’ in our definition of landesque capital. In a recent paper, such a conceptualisation is used to define the management of productive forests as a process of landesque capital accumulation (Börjesson & Ango Citation2021).

The process of incremental and small-scale changes through investments in ‘green’ landesque capital is applicable to the present study of premodern meadow land use. In pre-modern Swedish farming, farmers strove mainly to maintain long-term production rather than to implement large-scale modifications. Farming households based primarily on local subsistence production made investments in land when household consumption demands increased, economic circumstances changed or new technologies decreased the workload and facilitated an increase in living standards (Chayanov Citation1966, p. 6). The establishment of a meadow was largely reliant on long-term vegetation management, including a labour-intensive clearing process of trees, shrubs and stones as well as yearly maintenance measures such as the clearing/burning of leaves and twigs during springtime or maintaining ditches that regulate water flow. In contrast to more permanent features, such as clearance cairns and terraces, the reliance on continuous management of vegetation also meant that an abandoned meadow returned relatively rapidly to its original pre-clearance state. Meadow hay was part of wider economic circulations through livestock and its secondary products, such as butter and hides but also through manure, which in turn supported crop cultivation. In the studied areas, the livestock export economy was connected to both the taxation system and local subsistence strategies. It is therefore possible and fruitful to conceptualise the meadow and its connected work processes as a green landesque capital.

However, landesque capital is often associated with the enhancement and enrichment of soil (Widgren & Håkansson Citation2014; Börjesson Citation2014). The dry meadow is a paradox in this aspect, as nutrients are constantly removed from the meadow through the yearly removal of biomass (Aronsson Citation1979). After mowing, the meadow was opened for grazing, with further depletion of nutrients, even if a small amount of nitrogen was returned through animal spilling. A variety of measures were practised to add nitrogen to the soil when necessary, such as by letting a part of the meadow rest for one year or more, by disturbance regimes such as burning of the turf, or by the cultivation of temporary small arable fields in the meadow (Ekstam et al. Citation1988). The nutrition balance was not a problem in the wet meadows, which were regularly fertilised by flood sediments (Aronsson Citation1979). Nonetheless, the temporality of meadow investments, if left unmanaged, is one of the primary characteristics of meadow capital in relation to other forms of landesque capital. This paper examines how this feature of meadow capital was handled in premodern Sweden and what the results were in relation to social institutions such as ownership and usage rights.

Social institutions are an integrated part of landesque capital that limit human labour investments (Börjesson Citation2014, p. 253). For example, institutions in the form of pre-existing agreements between landholders limit what investments can be made and where. In this paper, we propose that the specific characteristics of different types of meadow capital may have a reciprocal effect on the institutional level. This is exemplified by outlying meadows, which seem to have been more dynamic in terms of ownership and use, in turn resulting in local institutions for conflict management. We focus on the economic institutions at work locally as opposed to vertical institutions affecting the local area at a regional or national level (Vestbö-Franzén Citation2012).

Institutions exist to facilitate economic intermediary action (North & Thomas Citation1973; North Citation1991). In a pre-capitalist society, an economic institution can emerge as an unwritten or codified agreement between stakeholders to avoid conflict. Such agreements tend to strive towards low transaction costs, which are the ‘costs’ (or the effort) necessary to execute agreements within an institutional framework such as the administrative costs involved, which in turn affect economic decision-making (Dahlman Citation1980, p. 79ff). Economic institutions, such as meadow capital, often evolve incrementally and are adapted to specific conditions at a specific time (North Citation1991). In this framework, property rights reflect the different ways assets are owned, used or decided over and are seen as endogenous to the local context under study and consequently are a valuable point on which to focus for analysis (Dahlman Citation1980, p. 66–7).

Institutions can operate relatively smoothly, as long as conflicts that arise can be solved locally inside the by-law or directly between the people involved. Interference from the outside in the form of regulations can lead to the elimination of an institution, but abandonment can also depend on rising transaction costs (Dahlman Citation1980). In the present context, this means that when an agreement cannot be reached locally, a conflict can be brought before the district court (Sw: häradsrätt), which is the lowest judicial level. In such a case, the cost of utilising the institution rises, and with an enhanced number of trials, the transaction costs may exceed the cost of the preservation of the institution. This means that it is also possible to test the relative volume of transaction costs between different types of land use, for example, between swidden cultivation, meadows and arable fields. By doing so, we can scrutinise the relative effectiveness of local institutions relating to meadow land use and compare different types of meadow cases.

The present paper builds on the close connection between investments in meadow land use and local economic institutions. While the general economic function of meadows in the northern European context is well known, this framework enables a close inspection of the ways in which meadows were locally established, managed and abandoned in relation to localised subsistence agriculture.

METHOD

The analysis in this paper is based on two primary source materials: court records and historical maps. Court records are used for studying local conflicts regarding meadows, and historical maps make it possible to locate the meadows in question, describe their character, and gain a fuller understanding of geographical factors influencing these conflicts.

Swedish law has been seen as part of a Scandinavian legal family, and the district courts a continuation and development of a local jurisdiction system with a much older history. Lay dominance in the jury gave the court local legitimacy (Korpiola Citation2014), and most disputes both between lay persons and authorities were historically handled at this level (Larsson Citation2016, p. 1104). The proceedings were led by either a circuit judge or, more often, a lay judge who was a trusted person from the district.

Records from district courts are a rich source for agrarian history. They summarise the negotiations and judicial decisions of the court. Only a few books have survived from the end of the sixteenth century, but beginning with the seventeenth century, volumes of records exist from almost each year’s winter, summer and autumn courts. In this paper, court records for the districts of Kind, Redväg and Östra were surveyed for cases relating to meadows. The years studied vary depending on the availability of the material (see ). Trials concerning meadows during these years are comparatively few, and the analysis is thus based on approximately 130 cases out of thousands. Nonetheless, these cases yield significant insight into local conflicts regarding meadows. To geographically situate the meadows taken up in the district courts, large-scale cadastral maps from approximately 1630–1750 were surveyed. This material is mainly based on an intensive survey initiated by the Crown during the period of 1630–1650, which gave rise to approximately 12,000 large-scale cadastral maps from farms and hamlets in large parts of Sweden (Tollin Citation2021). Mapping Sweden was the purview of the Crown, which meant that farms or manors belonging to the nobility lacked large-scale maps from this period, with the exemption of when nobility engaged surveyors themselves in order to map their holdings. Cadastral maps provide an opportunity to study where meadow land was situated in the farm or hamlet domain. Here, meadows are described as dry, wet, stony or well cleared. One disadvantage is that most of these early maps only depict the infield areas but read together with the next generation of maps from between 1680 and 1740, an overall picture of meadows in infield and outlying land can be obtained.

TABLE 1. STUDIED COURT RECORDS, RECORDS MARKED WITH * EXCERPTED BY ELISABETH GRÄSLUND BERG, DEPARTMENT OF HUMAN GEOGRAPHY, STOCKHOLM UNIVERSITY.

By combining these source materials, the cases raised in the district courts are given a geographic context, which enables a more complete understanding of different dimensions of meadow resources, both economically and socially.

THE LOCAL ECONOMY IN THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES

The agrarian economy of the early modern period was largely based on subsistence production in a feudal tradition where wealth was solely tied to land but contained varying degrees of exchange. Most necessities were produced in the household, such as food, textiles, leather, and tools, while other resources, such as salt and iron, as well as some services, had to be purchased (Gadd Citation2011, p. 130). Coins circulated in both local and regional geographical frames in this context, where money was used for fines and purchases at town markets (Vestbö-Franzén Citation2012). In the sixteenth century, a part of the Crown’s tax was often paid in money, both the main tax and the traditional fodringen (originally fodder for a certain number of animals, later often paid with money, Brunius Citation2011, p. 73). Surpluses from farming households were primarily invested in items such as silver spoons, which served as savings but also played a role in social life (Myrdal & Söderberg Citation1991, pp. 94–7). The Swedish nobility used its surplus for gifts to churches, clothing, houses, feasts, and horses, while productive investments were limited (Ferm Citation1990).

This context established the farming conditionsin the areas studied of Kind, Redväg and Östra. Physical geographical similarities are significant in all of the districts, with a domination of glacial till soils and larger rivers with floodplains historically used as wet meadows. In Kind and Redväg, however, settlements were typically located closer to the rivers themselves, while in Östra, settlements were usually disconnected from the floodplain by a tract of forested land and pastures. The climate in Östra is also characterised by colder winters and drier summers, while annual precipitation is higher in Kind and Redväg. In Kind, single farms dominated, while in Redväg and Östra, most farms were located in hamlets. In Redväg, however, the hamlets were usually larger (see ). Arable farming in these areas was characterised by annual cropping, where a variant of convertible husbandry in Kind and Redväg existed to some degree but was limited to settlements using a three-course rotation in Östra. This intensive agrarian system with limited fallow periods required large amounts of manure to return nutrients to the soil, and stalled animals fed meadow hay during the winter were a highly important source. Animal husbandry was consequently a local specialisation. In Östra and Redväg, physical-geographical conditions were more advantageous, and arable fields per farm were slightly larger than in Kind (GEORG 2021), indicating that these areas were somewhat less specialised than Kind was during the mid-seventeenth century. Husbandry specialisation is apparent in all areas when taxes and rents are mentioned in seventeenth-century court documents, and butter played a significant role.

TABLE 2. SETTLEMENT CHARACTERISTICS IN THE STUDIED AREAS IN THE MIDSEVENTEENTH CENTURY (DATA FROM THE DATABASE GEORG 2021, RA).

Meadows became increasingly important in the local economy of Kind, Redväg and Östra in the early modern period. The sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries were generally a period of expanding animal husbandry in the areas studied. These districts were highly involved in long-distance trade with oxen, which were primarily exported to the region of Bergslagen further north, where the iron industry had started to flourish at this time (Myrdal & Söderberg Citation1991, p. 484ff). The Crown was the primary actor on this stage during the sixteenth century, but especially during the seventeenth century town merchants started to dominate instead (ibid, pp. 454, 483). According to Lennart Andersson Palm, the increasing importance of animal production in western Sweden continued into the eighteenth century and meant that arable fields were gradually transformed into meadows or were deserted. In the early modern period, both Kind and Redväg were thus not self-sufficient in grain production (which was the primary food) but used their production advantage to exchange animal products for grains on the domestic market (Palm Citation1998). The economy of Östra is less well researched in this particular regard but it likely followed a similar development pattern.

In summary, meadows played a significant part in the local economies by enabling intensive arable farming, but more importantly, they served as a basis for specialisation in animal husbandry and produced commodities such as oxen and butter. This combined function serves as a background for understanding meadows as a form of landesque capital, which was created and circulated in local society in varying ways. In the next sections, meadows as landesque capital are explored further.

CLEARING THE MEADOWS — THE CREATION OF MEADOW CAPITAL

Landesque capital is created through lasting landscape modifications, such as the building of terraces, irrigation systems and stone and vegetation clearing. Meadows leave more ambiguous traces in the landscape since the production of a meadow does not necessarily entail direct topographical interventions such as terraces or ditches. Meadows are diverse in character over time and space, with large variations in their characteristics in different parts of the landscape as well as in different time periods and regions of Sweden. This means that the ways in which landesque capital is manifested in the form of meadows vary but so do the ways in which that capital is maintained.

The creation of a meadow first depends on the need for hay. As noted in the background section, meadows are generally closely interlinked with arable farming through the manure produced by stalled animals. More manure and consequently more meadows were needed to expand arable farming in a given area or when intensifying arable farming, by increasing yields per acre and concentrating arable land into smaller fields. Another aspect is that larger hay yields also enable the production of a larger herd of livestock, which can be a goal in itself.

The practice of meadow clearing is somewhat difficult to trace. It is only in the seventeenth and especially eighteenth centuries that reliable sources start to appear. One of the most detailed descriptions comes from the districts of Tunalän, Sevede and Aspeland in 1772, written by the district bailiff Magnus Gabriel Craelius. The described districts are situated immediately to the east of the district of Östra, which most likely makes them applicable for the studied areas as well, as they share many similar characteristics. This description is also most likely valid for older periods of time during similar technological conditions. According to Craelius, the clearing of a meadow depended largely on the vegetation. Dry meadows were primarily created through swidden cultivation on areas of pine, spruce, birch, and juniper vegetation. The vegetation was first burnt and then protected by wooden fences. Then, the soil was cultivated with grains for one year and left unused for two more years, after which it could be used either as meadow or pasture (Craelius Citation1986 [1774], pp. 165–6). Wet meadows were created on forested wetlands, usually dominated by spruce and alder trees. In dry years, or where conditions allowed, a burning technique was used in a manner similar to the dry meadow. However, where the soil was too wet to permit burning, tree stubs were gradually made to rot through the repeated cutting of saplings. The technique based on the cutting of roots common, for example, in the province of Dalarna, seems not to have been in use in eighteenth-century Småland (ibid., pp. 162–3).

If the clearing of meadows depended on a motive and available techniques, it was also reliant on institutions regulating the right to take up new land. Such rights were most likely often handled by local institutions such as through bylaws, which were established by the local community that came to agreements through a process of regulating customs. It was only in cases where local institutions failed to handle such things and conflicts subsequently emerged that a higher level of law was applied. The oldest medieval provincial laws from Västergötland make it clear that clearing land was not possible without some form of collective agreement between landowners in a hamlet or village (Ohlmarks Citation1976, pp. 366, 431). Magnus Eriksson’s law of the realm (Landslag), valid from 1350 until 1734, states that farmers were not allowed to take up arable land or meadow on a hamlet pasture without any previous land allotment. It was allowed to clear the forest for swidden cultivation, but only three years of sowing was permitted, after which the clearing was returned to village ownership. If a forest clearing was meant to be more permanent, allotment among the landholders was necessary (Holmbäck & Wessén Citation1962, p. 115). This points to the complicated nature of taking up new meadows within a settled community and reflects that this was often at least legally considered a collective action. Single farms would not have faced similar problems but were likely more restricted by the limited workforce available for such tasks.

A case from the district court of Östra illustrates this point, when a tenant under the nobleman Gustaf Stråle had taken the liberty to clear a meadow lying close to the nobleman’s odal-meadow (‘odal’ is a term referring to a plot of land that has long belonged to a property). According to the Landslag, it was illegal for a single peasant to clear and fence arable land or a meadow. Instead, a new clearing had to be divided between all the peasants in the hamlet based on their share in the hamlet’s tax measure unit. The tenant’s hay was sequestrated, and the other members of the by-law community were urged to clear meadows from common land in proportion to their shares. This was done, and the sequestration on the hay was resolved. If the shareholders could not agree on how large their individual shares were, an official allotment could be undertaken. This agreement was authorised by the district court in November 1650 (Östra häradsrätt 1650).

Collective efforts of meadow clearing were apparently allowed by the law but were regulated by local customs. A case from 1643 in Kind shows how a collective effort by several settlements in meadow clearing was handled and developed over time. This case concerned a meadow that had been created from an earlier pasture shared between the settlements Börsbo, Bredared, Hägnen and Lid. The work was conducted by farmers in Bredared, Hägnen and Lid, and the meadow was then divided among these units. This case also shows the importance of continuous land use — for example, through maintaining fences — to uphold land rights. In 1643, the dispute concerned the fact that Hägnen had abandoned its use of the meadow, which instead had been taken up by Bredared (Kinds häradsrätt 1643). This procedure is similar to processes of meadow clearing in the parish of Högsby in the county of Kalmar (Granlund Citation1969).

Several cases from the 1660s in Östra connect the clearing of meadows to the felling and burning of oak trees, which was highly restricted by the law. Oaks were considered the Crown’s property, but their felling and burning could be granted upon request (Hill & Töve Citation2003, p. 76), which was the case in Östra at this time. Most likely, this situation can be interpreted as a response to an increasing pressure for the clearing of dry meadows at this time but also shows the vertical relations connected to meadow clearing.

The clearing of meadows was regulated through customs, by-laws and the overarching juridical system and was also set in an economic and a technological context. Collective effort and agreement were needed in the creation of meadow capital in cases when land was shared or used by several farming households. Disagreements could also occur between neighbouring settlements regarding border uncertainties. The next sections examine how meadow capital, once created, was maintained or devalued over time and how certain practices developed in relation to this.

THE DEVALUATION AND MAINTENANCE OF MEADOW CAPITAL

In June 1647, the lay judges in Kind district testified, after a survey on the farm Å (Holsljunga parish), that the farm was to be considered a ‘tax wreck’ (Sw: skattevrak) and should be devaluated to half of its former taxable value. The meadow was overgrown with heather, and although the arable land was small, it could not be provided with manure ‘because of the scantiness of the meadow’ (Kinds häradsrätt 1647).

Legal cases clearly illuminate the need for meadow land. It was not lack of arable land or livestock, or money that decided the fate of the farm Å, but the meadow that had turned to waste. On the cadastral map from 1718, the farm is still denoted as deserted, meaning not that it was unsettled but rather that it was unable to pay its rent and taxes from the returns produced from the land. Instead, the surveyor notes that the weaving of fabric from wool and flax, together with some cattle breeding and the selling of butter and cheese gave the household its main income (LSA O69-40:1). In this case, the farmer had not been able to build up or maintain his landesque capital, and the ongoing process of meadow degeneration had affected the entire farm’s economy.

Cases concerning the decline of a farm’s ability to meet its tax burden or the resumption of a farm that for some reason was laid to waste often start with a description of the condition of the meadows. The quality of the meadow stands out as a prerequisite that decides if the farm could reach a sustainable level of production. Once a new meadow was incorporated into the farm or hamlet’s agrarian economy, the job of ensuring its maintenance over time began. Those who invested their work in the land expected long-term returns for their efforts. Dry meadows were especially sensitive in this regard due to the leakage of nutrients, but there is also an example where recurring floods destroyed wet meadow hay, in turn leading to tax depreciation (Kinds häradsrätt 1637). Changing hydrologic conditions could thus also negatively affect meadow capital.

Some cases illuminate how meadows as landesque capital could be removed from circulation and later become incorporated by others in need of such resources. A case from Alseda Parish in the district of Östra serves as an example. Per Ebbesson in the hamlet Kulla owned an outlying meadow in the hamlet Emmared but left it unused since he had ‘enough meadow anyway’ (Östra häradsrätt, 16th of August 1625). Four years prior, in 1621, Jon Finger in Emmared had begun to use the outlying meadow that for years had been lying ‘under cow’s feet and trodden by hoofs’. The court’s task was to establish whether the meadow was an asset belonging to Kulla or Emmared, and several elderly people testified that since time immemorial the outlying meadow had belonged to Kulla.

This example highlights how an asset that is of no use to one farmer can be crucial to another. In this case, an outlying meadow was taken out of circulation by Per Ebbasson, and Jon Finger goes through the process of clearing the overgrown meadow and re-activating the landesque capital. The underlying motives also show the meadow is an important part of a careful household calculation on which the reproduction of these farms relied. Per in Kulla abandoned a meadow that was no longer needed for his household’s reproduction, perhaps due to changing the type of farming he employed or because of an expansion of meadows closer to the farm itself. This constitutes a social process of devaluation affecting the meadow in question. Although the character of the meadow in Emmared remains unknown, the action of reclaiming it as a meadow by the local farmer ensured the endurance or maintenance of the landesque capital. It is also possible that the grazing activity slowed the process of vegetation overgrowth. These actions were therefore not only dependent on household hay requirements but also a way to appropriate or take advantage of capital built up by others before the process of degeneration had gone too far.

Meadows were thus under threat of different processes of devaluation, either biophysical or social. However, many court cases reveal a dynamic of maintenance existed to ensure the endurance of meadow capital over time. Devaluation processes in meadows seem not to have been systematic (i.e., large-scale abandonment) at this period in time, but rather sporadic and incremental, in turn often salvaged by neighbouring farms for different reasons and by various means. The social processes of meadow capital devaluation occurred at the farm level but not at a larger scale. The next section examines the details of this type of practice on an institutional level and scrutinizes the meadow in relation to other types of land use.

OUTLYING MEADOWS AND LOCAL ECONOMIC INSTITUTIONS

Court records constitute a substantial source of information, but the number of cases dealing with land disputes is relatively low. Trials dealing with owner or usership rights to land include cases of slash and burn cultivation, unlawful felling of oaks, border disputes between farms and hamlets, and, in a few cases, the right to use or reclaim a meadow. Conflicts regarding fixed arable land are very rare and are often mentioned only in connection to general infields alongside meadows. The low number of cases regarding infields means that the conflicts that arose were mainly solved within the by-law community or between the farms themselves. A similar argument can be presented for meadows in general, which occur more often but still comprise comparatively few cases.

TABLE 3. CASES RELATING TO MEADOWS FOUND IN THE COURT PROTOCOLS FROM EACH DISTRICT, DIVIDED INTO NINE DIFFERENT SUBJECT AREAS.

The relative lack of cases that deal with meadows in this respect during the first half of the sevententh century indicates that the connected local economic institutions worked well. Meadow land use and its related conflicts must be viewed at this time as a system not yet disturbed by high transaction costs.

In contrast, conflicts over outland slash and burn enterprises are much more frequent. This difference can be partly explained by the increasing pressure on outland resources during the seventeenth century. While the sixteenth century was marked by increasing outland colonisation, swidden cultivation and meadow establishment, the seventeenth century was a period of increasing markets for forest produce such as wood, coal and tar (Myrdal & Söderberg Citation1991, p. 507). Tar production and export were commonly practised in Kind during this period (Larson Citation1949). A process of outland degeneration is evident from northern Småland during this time and was primarily caused by an increase in the establishment of settlements, although thesituation in Östra was not as predominate as in neighbouring districts (Vestbö-Franzén Citation2004, p. 186). The increased pressure on the outlands meant that the practice of slash and burn agriculture had to compete with other forms of outland production, in combination with increased settlement. This pressure is marked by the high number of cases in the court records, indicating high transaction costs related to this type of land use.

While low transaction costs during the period studied meant that local institutions connected to meadow land use remained somewhat obscure, they were partly revealed in a few cases where conflicts regarding outlying meadows were decided at the district court level. In these instances, the factors used to make a determination in previous conflicts that had been solved locally were also revealed. In turn, these cases shed light on the intricate patterns of lending, pawning and leasing of meadows, which we argue are ways of maintaining and taking advantage of previous investments in meadow capital. These types of transactions are not similarly represented in cases concerning other types of land use.

Court cases regarding meadows are dominated by disputes concerning the ownership of specific outlying meadows (e.g. Östra häradsrätt 1594, 1623, 1650; Redvägs häradsrätt 1629, 1635, 1646; Kinds häradsrätt 1607, 1628, 1640), which in turn indirectly reveal the associated history of each underlying case. Meadows were used as an asset to pawn, lend or lease and in turn were regulated through local economic institutions.

A number of witnesses were involved in these cases, often ‘older men’ (or in one case an elderly woman) who could recall the situation one or two generations ago (e.g. Kinds häradsrätt 1609, 1629, Östra häradsrätt 1650, 1654). A survey was often required to reach a verdict on which side of a boundary a meadow lay, where lay judges and trusted men from the district walked the whole boundary and tried to resolve disagreements concerning boundary marks. A dispute could re-emerge and be returned to court repeatedly at great cost for the participants (e.g. Kinds häradsrätt 1609, 1610; Redvägs häradsrätt 1630, 1635). In Östra district, two trusted men, Jon in Götskögle and Jon in Dimmö, were often summoned as experts when it came to investigating complex owner /user structures connected to meadows (e.g. Östra häradsrätt 1650).

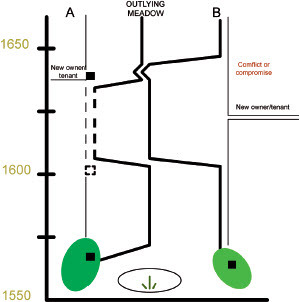

Cases regarding outlying meadows often follow a similar pattern (). One meadow in the outfield of hamlet A might have been used for thirty years by a farmer from farm B. Farmer (B) might have gained the right to use it during a period of time when the farm in hamlet A experienced a decline due to poverty or sickness. Initially, a deal or agreement probably existed where farm B gave money or hay in exchange for the use to farm A. As time passed and the farms changed tenants, the original agreement was forgotten, and the use of the meadow was considered an asset that belonged to the farm, by farm B’s new tenant. As the farm in hamlet A once again recovered under the same farmer’s regime or a new tenant, the question arose whether that particular outlying meadow had not formerly belonged to farm A. Elderly people could provide this information, or a written document could attest to the transfer. However, in most cases like this, with strong ownership evidence, the tenant or owner of farm A and of farm B simply shook hands and the situation returned to the one that had prevailed thirty years before. Nevertheless, in some cases, farm B — after some years of mowing in the outlying meadow — bought the meadow from farm A. Even this transaction could be forgotten, and a new tenant would be left unaware of the rightful ownership conditions. Multiple claims to the same meadow therefore could be raised to the courts.

Fig. 2. Model of the common pattern in ownership disputes regarding outlying meadows. The model shows how farm A takes up a meadow, which is later abandoned at the time of the farm’s decline. At that time, farm B started to use the meadow instead. A few years later, both farm A and farm B had new owners or tenants, and the original agreement was forgotten or blurred. It is at this point that a conflict arises concerning the ownership of the meadow in question.

Other court cases deal with meadows lent or pawned for a mortgage (e.g. Kinds häradsrätt 1627, Redvägs häradsrätt 1645, Östra häradsrätt 1651). After a period of time, knowledge concerning the original arrangement became unclear and led to conflicts that were brought to the court. There are examples of cases where a farmer offered to clear a former meadow that had become overgrown by trees and shrubs in another farm’s outlying land, in exchange for using it and harvesting the hay for some time (e.g. Östra häradsrätt 1650). After an unfixed period of time, the farm that had cleared and used the meadow could claim ownership through custom (sw: urminnes hävd) if it had been left without attention from the original owner / farm (Vestbö-Franzén, Citation2003, pp 187–210). The court could also decree that the meadow would be divided between the former owner and the new one.

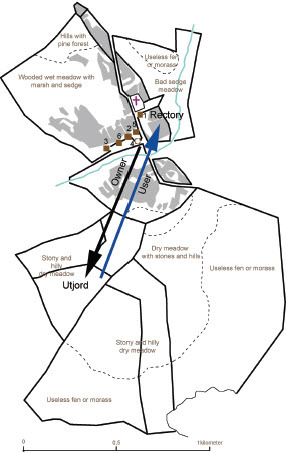

One example can be studied in more detail (). Queen Christina I (1626–1689, and the ruling queen 1644–1654) granted some crown property in Alseda parish in Östra to the gentlewoman Ursula von Steinberg (1616–1672), including an utjord (a non-settled cadastral unit, most often the land of a farm that was deserted during the late medieval agrarian crisis (Karsvall Citation2016). This utjord was used as an outlying meadow under the rectory of Alseda with a yield of twelve loads of hay yearly. The vicar argued, in front of the winter court in January 1648, that considering the many extra expenses that follow the rectory, the economy would be severely harmed without the hay from this particular meadow. The twelve loads are not mentioned in the court record, but a cadastral map from 1645 showing Alseda hamlet describes the yield from the infield and the outlying meadows, amongst them the utjord in question (LSA E4:114-17). The utjord corresponded to 10 per cent of the rectory’s total yield of hay from dry and wet meadows. A fairly low percentage, but probably an intricate part of a critical calculation where hay, livestock and manure make up the parts. Eventually, the Queen withdrew the meadow from the grant to von Steinberg and returned it to the vicar’s farm in Alseda (Östra häradsrätt 1648).

Fig. 3. Map depicting the case of the Alseda rectory, which was dependent on hay from an outlying utjord (a non-settled cadastral unit), which in turn was owned by another deserted farm in the hamlet. The map shows the geographical location of the utjord in question, the rectory, and the farm that owned the meadow. Grey areas represent arable fields and thick black lines represent fences (Adapted from LSA E4:114–17).

Arguments that the removal of a meadow, even a small meadow, may severely harm the farm’s economy are recurring and seem to be taken ad notam by the district court. The overall problem for the court was to investigate the ownership pattern of who owned a meadow, or who leased or lent it. In the mentioned case, the utjord did not lie directly under the rectory but instead was an indirect asset. One of the farms in Alseda hamlet (Farm No 4) is marked as öde or ‘deserted’ on the map from 1645, meaning that the farm probably was occupied but that the tenants for some reason could not pay their rent or taxes. It was economically deserted rather than unoccupied. The map lists the utjord as an asset under the deserted farm with the addendum that ‘since the farm is deserted, the utjord or meadow is used by the vicar in Alseda’. In our research we did not investigate the length of time the utjord was used by the rectory or when (if ever) the deserted farm regained use of the meadow, but the case provides insight to pinpoint the meadow’s role in the local economy and to illustrate the dynamic character of meadow capital.

Outlying meadows were part of a dynamic agrarian landscape. In comparison with infield use, outlands were used even more dynamically over time, especially during the period studied, when other forms of secondary resource use started to be more common. Infield transaction costs were generally lower than those related to outland use at this time as a result of the distant location of outlying meadows. It is thus not surprising to find more court cases related to these meadows than those on the infields. Outlying meadows were more distant from the main settlement area and were more difficult to overlook, manage and guard. Nevertheless, investments in these types of meadows were sometimes invaluable to the farming household, and the system of lending, pawning and leasing of meadows was a means to preserve these investments over time. It is also the case that a meadow may be an asset to a farm even though the hay itself was unnecessary for the household. We would thus like to argue that this system and its related local economic institutions were primarily related to this type of land use, revealing how the characteristics of a specific type of landesque capital also developed in the local institutional context.

CONCLUSION

This paper contributes towards filling a research gap in Swedish agrarian history through an analysis of the economic role of meadows, and presents reliable source material useful for such studies. By examining the records of trials from the district courts in Kind, Redväg and Östra between 1600 and 1660, in combination with cadastral maps, new perspectives are presented. Through this material, the meadows can be analysed as landesque capital, partly by following the individual meadows and how people relate to each from an economic viewpoint, and partly by revealing different strategies of long-term meadow management in which pawning, leasing or hiring was an important part.

This study points out that the effective management of meadow investments, which were often collective efforts, necessitated specific practices. Meadows were an essential part of the household economy, and the handling of meadow devaluation / degeneration over time due to biophysical processes was important. Devaluation through abandonment was also a social process but did not occur on a systematic level at this time. Instead, when a meadow was abandoned, it was often taken up by others, either by agreement between the landowner and user or surreptitiously. The distance of outlying meadows meant that these properties were often involved in these types of transactions between farms and settlements. Leasing, lending or pawning became options to preserve a meadow or generate revenue, although the hay itself may not have been needed by the owner. The distance of these meadows relative to the farm that associated with them also meant that such arrangements could become unclear over time, leading to future conflicts when the original agreements had been forgotten. The meadow’s character as a comparatively temporal investment in need of careful management most likely supported the development of institutions for local land transactions.

In general, meadow land use was affected by fairly low transaction costs in comparison to slash and burn agriculture, which was more was threatened by diversified outland use. However, outlying meadows were more frequently the subject of land disputes than infields. Most likely, this was related to the institutional frameworks surrounding this type of land as well as the distance from the main settlement area. The infields were more stable in this regard in terms of ownership, and the use of infield land was more easily regulated by by-laws.

The results of this study point to the potential of historical analyses of meadows, specifically in this context of Sweden. It is unclear whether the results presented here would be valid in other regions in Sweden, for example, on the agricultural plains of east-central and western Sweden. The districts studied here were generally less populated and had a greater abundance of land usable for meadows. The larger amount of arable land on the plains could have led to meadows being more contested or more strictly bound in terms of ownership and use. Further studies are thus needed in a larger variety of geographical contexts.

The potential of using court protocols cannot be understated as a source material for studies of institutions and customs relating to different forms of land use. Jesper Larsson (Citation2016) has previously shown how such material enables a close inspection of the management of common pool resources. For early seventeenth-century meadows, court records emerge as the primary source material that yields the most significant insights into premodern meadow land use and ownership aspects.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Lowe Börjesson and Mats Widgren for constructive comments on the first draft of the paper. We would also like to thank Elisabeth Gräslund Berg for giving access to her excerpts of court protocols from the district of Östra for the years 1662–1665. The paper also benefited from a thorough review by Michael Richard Handley Jones.

Notes

1 This work was supported by Jan Wallander & Tom was supported by funding from Carl Mannerfelts Hedelius stiftelse along with Tore Browaldhs stiftelse scholarship. under Grant P20-0170 (Handelsbanken). Field work was supported by funding from Carl Mannerfelts scholarship.

PRIMARY SOURCES

- Östra häradsrätts arkiv, Aia:4, Landsarkivet i Vadstena. Kinds häradsrätts arkiv, Aia: 1-3, Landsarkivet i Göteborg. Lantmäteristyrelsens arkiv (LSA) E4:114-17, Alseda, Alseda parish, Geometrisk avmätning, 1645.

- Lantmäteristyrelsens arkiv (LSA) O69-40:1, Å, Holsljunga parish, Geometrisk avmätning 1718.

- Redvägs häradsrätt in Göta hovrätt. Advokatfiskalens arkiv, EVIIAAAB:2, 4, 9, 11, 17. Landsarkivet i Vadstena.

SECONDARY SOURCES

- GEORG, 2021. ’Sveriges äldsta storskaliga kartor. Stockholm, Riksarkivet’; https://riksarkivet.se/geometriska [accessed 11 February 2021]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Aronsson M. 1979. ‘Slåtter- och betesmark i det äldre odlingslandskapet’, Odlingslandskap och livsform (Stockholm), pp. 72–96.

- Berglund B., Lagerås P., & Regnéll J., 2002. ‘Odlingslandskapets historia i Sydsverige – en pollenanalytisk syntes’, in Markens minnen. Landskap och odlingshistoria på småländska höglandet under 6000 år , ed.: B .E. Berglund & K. Börjesson (Stockholm), pp. 153–74.

- Blaikie, P., & Brookfield, H., 1987. Land Degradation and Society (New York, US).

- Börjesson, L., 2014. ‘The antithesis of degraded land: toward a greener conceptualization of landesque capital’, Landesque capital: the historical ecology of enduring landscape modifications, ed. N. T. Håkansson & M. Widgren (Walnut Creek, CA, US), pp. 251–68.

- Börjesson, L., & Ango, T. G., 2021. ‘The production and destruction of forests through the lens of landesque capital accumulation’, Human Ecol, 49, pp. 259–69. doi: 10.1007/s10745-021-00221-4

- Brookfield, H. C., 1984. ‘Intensification revisited’, Pacific Viewpoint, 25, pp. 15–44. doi: 10.1111/apv.251002

- Brunius, J., 2011. Vasatidens samhälle. En vägledning till arkiven 1520–1620 i Riksarivet (Vällingby).

- Campbell, Å., 1948. Från vildmark till bygd: en etnologisk undersökning av nybyggarkulturen i Lappland före industrialismens genombrott (Uddevalla):

- Chayanov, A. V., 1966. The Theory of Peasant Economy (Hornwood).

- Craelius, M. G., 1986 [1774]. Försök till ett landskaps beskrivning.(Vimmerby).

- Dahlman, C. J., 1980: The Open Field System and Beyond. A property rights analysis of an economic institution. (Cambridge).

- Dovring, F., 1947. Attungen och marklandet. Studier över agrara förhållanden i medeltidens Sverige (Lund).

- Egerbladh, I., 1987. Agrara bebyggelseprocesser: utvecklingen i Norrbottens kustland fram till 1900-talet (Umeå).

- Ekstam, U., Aronsson, M., & Forshed, N., 1988. Ängar. Om naturliga slåttermarker i odlingslandskapet (Stockholm).

- Ericsson, A., 2012. Terra mediaevalis. Jordvärderingssystem i medeltidens Sverige (Uppsala).

- Eriksson, O., 2020. ‘Origin and development of managed meadows in Sweden: a review’, Rural Landscapes: Soc, Environ, Hist, 7:1, pp. 1–23.

- Ferm, O., 1990. De högadliga godsen i Sverige vid 1500-talets mitt: geografisk uppbyggnad, räntestruktur, godsdrift och hushållning (Stockholm).

- Frandsen, K., 1983, Vang og tægt. Studier over dyrkningssystemer og agrarstrukturer i Danmarks landsbyer 1682–83 (Copenhagen).

- Frödin, J. 1952. Skogar och myrar i norra Sverige i deras funktioner som betesmark och slåtter (Oslo).

- Frödin J., 1954. Uppländska betes- och slåttermarker i gamla tider, deras utnyttjande genom landskapets fäbodväsen (Uppsala).

- Gadd, C-J., 2000. Det svenska jordbrukets historia bd 3. Den agrara revolutionen: 1700–1870 (Stockholm).

- Gadd, C-J., 2011. ‘The agricultural revolution in Sweden, 1700–1870’, in The Agrarian History of Sweden. From 4000 bc to ad 2000, ed. J. Myrdal & M. Morell (Lund), pp. 118–64.

- Granlund J., 1969. ‘Högsby socken och dess byar, näringsliv samt sed och tro’, in Högsbyboken, ed. H. Eriksson & O. Franzén (Högsby), pp. 63–562

- Hannerberg, D., 1971. Svenskt agrarsamhälle under 1200 år. Gård och åker, skörd och boskap (Stockholm).

- Helmfrid, S., 2000: Europeiska agrarlandskap. En forskningsöversikt (Stockholm).

- Herschend, F., 2020. Från ord till poetisk handling: skandinavisk skrivkunnighet före 536 (Uppsala).

- Hill, Ö., & Töve, J., 2003. Kunskap om skogens historia (Göteborg).

- Holmbäck, Å., & Wessén, E., 1962. Magnus Erikssons landslag (Stockholm).

- Jansson, U., 1998. Odlingssystem i Vänerområdet. En studie av tidigmodernt jordbruk i Västsverige (Stockholm).

- Jansson, U., 2005. ‘Forskning om odlingssystem under de senaste 100 åren – en översikt’, Bruka, odla, hävda. Odlingssystem och uthålligt jordbruk under 400 år, ed. U. Jansson & E. Mårald (Stockholm), pp. 15–26.

- Jupiter, K., 2020. ‘The function of open-field farming – managing time, work and space’, In Landscape Hist, 41:1, pp. 69–98. doi: 10.1080/01433768.2020.1753984

- Karsvall, O., 2016. Utjordar och ödegårdar: en studie i retrogressiv metod (Uppsala).

- Kolås, S. B., 2012. ‘Runer i kontekst: En analyse av Magnus Olsens tolkning av Strömsbrynet, Eggjarinnskriften og N492’, Norwegian Univ of Science & Technology Master thesis.

- Korpiola, M., 2014. ‘Not without the consent and goodwill of the common people’: the community as a legal authority in medieval Sweden, J Legal Hist, 35:2, pp. 95–119. doi: 10.1080/01440365.2014.925173

- Larson, A., 1949. ‘Näringslivet i Svenljunga under 1500- och 1600-talen’, Från Borås och de sju häradena, 4, pp. 47–90.

- Larsson, J., 2016. ‘Conflict-resolution mechanisms maintaining an agricultural system. Early modern local courts as an arena for solving collective-action problems within Scandinavian Civil Law’, Int J of the Commons, 10:2, pp. 1100–18. doi: 10.18352/ijc.666

- Lennartsson, T., & Westin, A., 2019. Ängar och slåtter: historia, ekologi, natur- och kulturmiljövård. (Stockholm).

- Lennartsson, T., Westin, A., Iuga, A., et al., 2016. ‘”The meadow is the mother of the field”. Comparing transformations in hay production in three European agroecosystems’, Martor, 21, pp. 103–26.

- Mazoyer, M., & Roudart, L., 2006. A History of World Agriculture. From the Neolithic Age to the current crisis (London).

- Myrdal, J., & Söderberg, J., 1991. Kontinuitetens dynamik: agrar ekonomi i 1500-talets Sverige. (Stockholm).

- Myrdal, J., 1982. ‘Jordbruksredskap av järn före år 1000., Fornvännen, 77, pp. 81–104.

- Myrdal, J., 1999. Det svenska jordbrukets historia bd 2. Jordbruket under feodalismen: 1000–1700. (Stockholm).

- North, D. C., 1991. ‘Institutions’, J Econ Perspectives- Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 97–112. doi: 10.1257/jep.5.1.97

- North, D. C., & Thomas, R., 1973. The Rise of the Western World: a new economic history (Cambridge).

- Ohlmarks, Å. ed, 1976. De svenska landskapslagarna (Stockholm).

- Palm, L. A., 1997. ‘Boskapsskötseln – en historisk förutsättning’, in Bygden vid ridvägarna – Årtusenden kring Åsunden, ed. L. Holmén (Borås), pp. 91–106.

- Palm, L. A., 1998. ‘Efterblivenhet eller rationell tidsanvändning – frågor kring det västsvenska ensädet’, in Ett föränderligt agrarsamhälle. Västsverige i jämförande belysning, ed. L. A. Palm, C-J. Gadd & L. Nyström (Göteborg), pp. 13–82.

- Pearson, A.W., & Soar, P. J., 2018. ‘Meadowlands in time: re-envisioning the lost meadows of the Rother valley, West Sussex, UK’. Landscape Hist, 39:1, pp. 25–55 doi: 10.1080/01433768.2018.1466549

- Pedersen, E-A., Welinder, S., & Widgren, M., 1998. ‘Det svenska jordbrukets historia bd 1’, Jordbrukets första 5000 år (Stockholm).

- Pedersen, E. A., & Widgren, M. 2011. ‘Agriculture in Sweden: 800 BC–AD 1000’, In The Agrarian History of Sweden: from 4000 BC to AD 2000 (Lund), pp. 46–71.

- Petersson, M., 2006. Djurhållning och betesdrift: djur, människor och landskap i västra Östergötland under yngre bronsålder och äldre järnålder (Uppsala).

- Renes, H., Centeri, C., Eiter, S., et al., 2019. ‘Water meadows as European agricultural heritage’, in Adaptive Strategies for Water Heritage, ed. C. Hein (Cham), pp. 106–31.

- Rosenhane, S., 1944 [1663]. Oeconomia (Uppsala).

- Sjöbeck, M., 1947. ‘Iakttagelser rörande den bebyggelsehistoriska utvecklingen omkring den forna Kafjärden i Södermanland, Fornvännen, 42, pp. 230–47.

- Spulerova, J., Kruse, A., Branduini, P., et al., 2019. ‘Past, present and future of hay-making structures in Europe.’, Sustainability, 11, p. 5581. doi: 10.3390/su11205581

- Tollin, C., 2021. Sveriges kartor och lantmätare 1628 till 1680: från idé till tolvtusen kartor (Stockholm).

- Vázquez, I., 2020. ‘Lot meadows, do they have a role in understanding scattered holdings? A study case in northern Spain’, Landscape Hist, 41:2, pp. 71–88. doi: 10.1080/01433768.2020.1835185

- Vestbö-Franzén, A., 2003. ‘Relationer, rum och resurser – eller från utjord till säteri i Vireda socken’, in Med landskapet i centrum. Kulturgeografiska perspektiv på nutida och historiska landskap, ed. U. Jansson (Stockholm), pp. 187–210.

- Vestbö-Franzén, Å., 2004. Råg och rön: om mat, människor och landskapsförändringar i norra Småland ca 1550– 1700 (Stockholm).

- Vestbö-Franzén, Å., 2012. ‘Vardagens varuflöden i 1600-talets Småland. Lokalsamhällets bytes- och marknadsekonomi speglad i rättshistoriska källor, Lilla tullen och de äldsta geometriska kartorna’, Bebyggelsehistorisk tidskrift, 63. pp. 92–110.

- Widgren, M., 2012. ‘Climate and causation in the Swedish Iron Age: learning from the present to understand the past’, Geografisk Tidsskrift – Danish J Geog, 112:2, pp. 126–34. doi: 10.1080/00167223.2012.741886

- Widgren, M., & Håkansson, N. T., 2014. ‘Landesque capital: What is the concept good for?’, in Landesque Capital: the historical ecology of enduring landscape modifications, ed. N. T. Håkansson & M. Widgren, (Walnut Creek, CA, US), pp. 9–30.

- Williamson, T., 2003. Shaping medieval landscapes: settlement, society, environment (Bollington, Macclesfield).

- Williamson, T., 2012. Environment, society and landscape in early medieval England: time and topography (Woodbridge).