ABSTRACT

Traditionally, languages have been separated from each other in the school curriculum and there has been little consideration for resources that learners possess as emergent multilinguals. This policy is aimed at the protection of minority languages and has sought to avoid cross-linguistic influence and codeswitching. However, these ideas have been challenged by current multilingual ideologies in a society that is becoming more globalised. Within the field of multilingual education studies, there is a strong trend towards replacing the idea of isolated linguistic systems with approaches that take multilingual speakers and their linguistic repertoire as a reference.

This article focuses on translanguaging, a concept that was developed in bilingual schools in Wales and refers both to pedagogically oriented strategies and to spontaneous language practices. In this article, translanguaging will be analysed as related to the protection and promotion of minority languages. Examples from multilingual education involving minority languages will be shown in order to see how translanguaging can be at the same time a threat for the survival of minority languages and an opportunity for their development. A set of principles that can contribute to sustainable translanguaging in a context of regional minority language use will be discussed.

Introduction

La kilo de azúcar, la real canela, pa Tiburtzio las esparzines del número ventilau.

Spanish translation: Un kilo de azúcar, un real de canela, zapatillas para Tiburcio del número veinticuatro

English translation: A kilo of sugar, one penny of cinnamon, and slippers for Tiburtzio, number twenty four.

This utterance is an often retold anecdote produced in the 1950s in which a Basque farmer is depicted trying to use Spanish when shopping in a small village in the North of Navarre. He lived in a Basque-speaking village and had to do his shopping in a neighbouring village where Spanish was more widely used. The speaker employed features from his whole linguistic repertoire. The basic structure of the sentence is Spanish but it has the word ‘esparzines’ which is Basque with a Spanish ending and ‘lau’ which is the number four in Basque. There are some problems with the use of articles ‘la kilo’ ‘la real’, and with the use of the prepositions ‘de’ and ‘para’. The example is a jocular way to imitate Basque speakers from rural areas who could not speak ‘proper’ Spanish and Basque was looked down upon.

The example shows how monolingual majority speakers make fun of speakers of the minority language who try to use the majority language. Hélot and De Mejía (Citation2008, 1) contrast bilingualism involving internationally prestigious languages which is visible and socially accepted with bilingualism in minority languages which ‘leads, in many cases, to an “invisible” form of bilingualism in which the native language is undervalued and associated with underdevelopment, poverty and backwardness!’. Since the 1950s, the Basque language has risen in status in some areas of the Basque Country as the result of changes in political and social power but Basque remains a minority language. The example in the popular anecdote not only shows Basque as a less powerful language but also shows that while it is natural for bilingual speakers or emergent bilinguals to use resources from their linguistic repertoire in communication, combining elements of different languages is not easily accepted by society. This situation may be changing, as there has been an important development in the study of translanguaging and translingual practices in different contexts (see, for example, Canagarajah Citation2013; García and Li Citation2014).

In this article, we discuss minority languages as related to translanguaging. We focus on the situation of Basque but the discussion can also be extended to other minority languages and particularly to multilingual contexts involving languages such as Breton, Frisian, Irish, Māori or Welsh. We emphasise the way language isolating policies and/or translanguaging can have an effect on the survival of minority languages.

The dynamics of minority languages

The development of different languages cannot be separated from socio-economic and sociopolitical factors (May, Citation2000; Edwards, Citation2012). This can certainly be seen in the case of minority languages that have often been associated with shame and backwardness but that can also acquire a higher social status as a consequence of these factors. A good example of the dynamics of minority languages at work is the case of the Basque language. The opening sentence of this article shows how Basque was associated with shame and backwardness. In fact, Basque was excluded from the public domain for many decades in the twentieth century during Franco’s dictatorship in Spain. Basque was maintained predominantly in rural areas but was forbidden to be taught at school. In our example, the people from a nearby village that was predominantly Spanish-speaking, because it was closer located to a main road and whose teachers and priest spoke Spanish, ridiculed a Basque speaker who tried to use his bilingual resources to communicate in Spanish. After important socio-economic and sociopolitical changes in the last quarter of the twentieth century, the Basque language is now more widespread. The Basque Country consists of three administrative parts, two in Spain and one in France. A comparison of survey data from 1991 and 2011 indicates that the percentage of Basque speakers in the Basque Autonomous Community has increased from 24% to 32% and in Navarre from 9.5% to 11.7% (Basque Government Citation2012) due to policies designed to support the language. However, a lack of such policies in the French part of the Basque Country resulted in a decline in the number of speakers (from 33% to 21.4%) during the same period.

In the Basque Autonomous Community, Basque, Spanish and a foreign language (in most cases English) are compulsory school subjects and parents can choose either Basque, Spanish or both as the languages of instruction for their children. In the early twenty-first century, Basque has become the main language of instruction in primary and secondary school. Basque is a minority language spoken by about one-third of the population in the Basque Autonomous Community; yet, many parents who do not speak Basque choose to have their children educated through the medium of Basque not only for identity reasons but also because Basque can be useful for their children in the job market (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2011; Gorter et al. Citation2014). Supported by a strong language policy, Basque is also used in sectors such as the health service, government, administration and higher education.

The Basque case shows the dynamics of minority languages and how Basque has moved from shame and backwardness to being promoted and accepted all over the Basque Autonomous Community. This change is obviously associated with socio-economic and sociopolitical factors. The Basque case at the same time shows the vulnerability of minority languages. Nowadays, the policies promoting Basque can be considered as a success regarding the increase in the number of speakers in the Basque Autonomous Community and the use of Basque as the language of instruction in schools. However, the Basque language still faces many challenges. Minority language speakers are bilingual and multilingual because they need to speak the majority language and often a third language as well. Minority languages such as Basque are always in contact with other languages that are spoken by the majority of the population. In the past, Basque was isolated in some areas in what we can describe as comfort zones, but today, Spanish is the first language of many Basque speakers and often Basque is only used at school. In fact, data about the use of the Basque language show that in spite of all the efforts to promote the language over the past 35 years, its use remains quite limited (Gorter et al. Citation2014).

Notwithstanding the strong policy to protect and promote the use of Basque, the language is still vulnerable and, like many other minority languages, it can easily be damaged or attacked. Nowadays, it is possible to publish legal documents in Basque or to submit a doctoral thesis in the disciplines of Neurology or Physics in Basque because the language has moved from local, rural, almost monolingual contexts to global, urban, multilingual ones. Basque is one of the languages in the multilingual speaker’s repertoire of citizens of the Basque Autonomous Community in the twenty-first century, next to Spanish, increasingly English and sometimes other languages. In the following sections, we discuss the implications of these new circumstances as related to translanguaging.

New trends in multilingualism

It may sound contradictory, but traditionally monolingualism has been the reference for bilingualism and second language acquisition. Bilingual speakers have been compared to two monolingual speakers and second language learners’ development has been measured by taking the native speaker of the target language as a reference. This has also been the case when more than two languages are involved in multilingualism and the acquisition of third or additional languages. These ideologies of language separation have been criticised (Grosjean Citation1985; Cook Citation1999; Cummins Citation2007; Creese and Blackledge Citation2010; Li Citation2011) and a new emergent paradigm is taking shape. This paradigm, which is more in accordance with globalisation, digital communication and the mobility of the population, is based on a series of proposals that focus on the way multilinguals communicate and go against monolingual ideologies (see, for example, Cenoz and Gorter Citation2015; Conteh and Meier Citation2014; May Citation2014; Paquet-Gauthier and Beaulieu Citation2016).

Translanguaging is one of the more widely used concepts associated with the new trends in the study of multilingualism. The concept of translanguaging was first used in the context of bilingual education in English and a minority language, Welsh. As Lewis, Jones, and Baker (Citation2012a) explain, it refers to a bilingual pedagogy based on alternating the languages used for input and output in a systematic way. An example of translanguaging would be to read a text in English and then prepare an oral presentation based on the text in Welsh. The aim of this pedagogic strategy is to reinforce both languages and to increase understanding. According to Lewis, Jones, and Baker (Citation2012b), translanguaging provides scaffolding and support that can be removed when children are more advanced in their language competence.

Translanguaging is also used to increase comprehension in the context of other minority languages. For example, Lowman et al. (Citation2007) reported that Māori literacy levels increased when students were allowed to use their first language, English, to process and analyse texts that were in Māori. Llurda, Cots, and Armengol (Citation2013), in the context of a Catalan university, also reported the use of English and Catalan to support students’ comprehension in an English-medium class.

The term translanguaging is nowadays used in different ways. It can keep its original meaning as a pedagogical strategy referring to the planned alternation of input and output as developed in the Welsh context. However, as Lewis, Jones, and Baker (Citation2012a) point out, translanguaging has become generalised from the school to the street to refer to different contexts. Therefore, we can distinguish the pedagogical use of translanguaging from spontaneous translanguaging which refers to the complex discourse practices of bilinguals (see García Citation2009). Translanguaging thus goes beyond the concept of scaffolding for comprehension inside the classroom and has been defined as ‘the ability of multilingual speakers to shuttle between languages, treating the diverse languages that form their repertoire as an integrated system’ (Canagarajah Citation2011, 401). The idea of the whole linguistic repertoire as an integrated system has also been highlighted by other authors (see, for example, Cenoz and Gorter Citation2011, Citation2015; García Citation2009; García and Li Citation2014).

Pedagogical translanguaging can also be referred to as intentional translanguaging or classroom translanguaging because it embraces instructional strategies that integrate two or more languages. In its origin, it was a planned alternation of the languages for input and output, but it has expanded to include other pedagogical strategies that go across languages. Spontaneous translanguaging is considered the more universal form of translanguaging because it can take place inside and outside the classroom. It refers to the reality of bi/multilingual usage in naturally occurring contexts where boundaries between languages are fluid and constantly shifting. García and Li (Citation2014, 20) argue that translanguaging goes beyond the concept of two languages and is not a mixture of languages but refers to new language practices. They also propose that spontaneous translanguaging should be accepted as a legitimate practice. García (Citation2009) views languages as fluid codes framed within social practices and is convinced that bilingual students can participate in more situations if they are allowed to translanguage. In the next section, we will focus on spontaneous translanguaging and its possible effect on the survival of minority languages.

Is translanguaging a threat for minority languages?

Studies of spontaneous translanguaging have mainly focused on cases of bilingual speakers who speak an additional language in English-speaking countries (García Citation2009; Creese and Blackledge Citation2010; Martin-Beltrán Citation2014; Martinez-Roldán Citation2015; Gort and Sembiante Citation2015). The languages they speak (Spanish, Punjabi and Mandarin) are minority languages in the US or the UK, but these languages are relatively strong demographically and have a high status in other countries. In this article, we discuss translanguaging as related to regional minority languages with a minority status in one or more states. This is an important difference because these languages are vulnerable and their future is not always secured.

Otheguy, García, and Reid (Citation2015, 283) consider that translanguaging can be beneficial for minoritised communities and their languages:

Translanguaging, then, as we shall see, provides a smoother conceptual path than previous approaches to the goal of protecting minoritized communities, their languages, and their learners and schools.

According to Otheguy, García and Reid (Citation2015, 299), who also discuss minority languages such as Basque, Māori or Hawaiian, the struggle is not to preserve a collection of lexical and structural features but ‘a cultural-linguistic complex of multiple idiolects and translanguaging practices that the community finds valuable’. It is not a question of isolating but of allowing learners to speak freely. Otheguy, García, and Reid clearly advocate the legitimisation of translanguaging practices that in the context of the US have sometimes been referred to as Spanglish (Spanish + English) and in the context of Basque–Spanish bilingualism as Euskañol, from euskara (Basque) + español (Spanish). In the case of Basque, the idea would be to protect the language without isolating it from others, as García explained when interviewed by a Basque local newspaper (Diario Vasco 21 May 2015). The idea of legitimising translanguaging practices meets some strong reactions in the Basque Country, as can be seen in the following comments about the newspaper interview with Ofelia García:

-Translanguaging delako horrekin diglosiaren konponbiderik ez bada planteatzen euskañola insttuzionalizatu eta euskara galtzaile dakusat. (Zabala Citation2015)

The so-called translanguaging, rather than solving diglossia, will institutionalize euskañol and I see Basque as the loser

-Ez dut uste ona denik gurenean aplikatzeko, inolaz ere, oraingo euskararekiko egoera izanda den bezalakoa (Azurmendi, personal communication)

I don’t think it is good for us to apply it [translanguaging], taking into account the current situation of Basque

There is a strong fear that Basque may just disappear if it is mixed with Spanish because Spanish is a very strong language compared to Basque. These fears are to a certain extent justified if we look at the use of minority languages not only in the Basque Country but in other contexts as well. Hickey (Citation2001) conducted a study in Irish-medium pre-schools and reported the results of observing the utterances produced by children with Irish as a first or second language. For children with Irish as their first language, the programme was a language maintenance programme with Irish as the language of instruction. The same programme can be considered an immersion programme for children with English as a first language. The data reported by Hickey indicate that Irish first language children in an Irish-medium pre-school produced about half of the utterances in English. Children with English as the first language produced about two-thirds of the utterances in English. This study shows the vulnerability of the minority language and how there is a clear trend for all children to switch to the majority language.

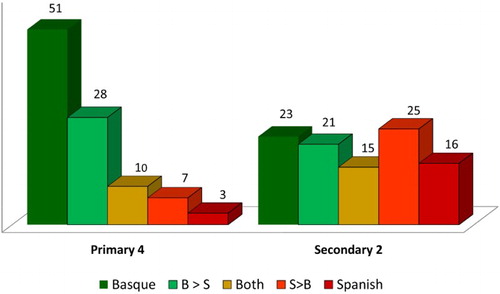

A study on the use of Basque confirms the vulnerability of the minority language and can help to understand why some Basque speakers see translanguaging as a threat. Participants in the so-called Arrue project consisted of the whole population of students in the fourth year of primary education (N = 18,636) and in the second year of secondary education (N = 17,184) in the Basque Autonomous Community (Basque Government Citation2013). Basque was the main language of instruction for 11,936 students in the fourth of primary (64% of the total number of students in the fourth year of primary) and 10,112 students in the second year of secondary education (58.8% of the total number of students in the second year of secondary). These students have Basque as the language of instruction for all their school subjects, except Spanish and English language arts. If we look at the percentages of Basque language use as reported by these students with Basque as the main language of instruction (see ), we observe a substantial difference between primary and secondary schools. By far, most students in primary school (79%) use ‘Basque only’ or ‘more Basque than Spanish’ inside the classroom, but in secondary school, only a minority (44%) report using mainly Basque.

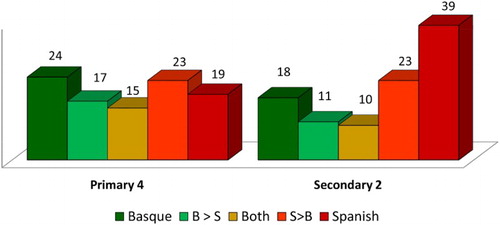

The vulnerability of Basque in the situation where it is the main language of instruction is even more visible when students report their use of Basque in the schoolyard. As we can see in , in primary school, a minority (41%) of the students report using ‘only Basque’ or ‘more Basque than Spanish’ and in secondary school, the percentage goes down to 29%.

In many cases, minority languages are stronger in areas that have been more protected from the influence of majority languages because of their relative geographical isolation until the latter part of the twentieth century. Some examples are the Gaeltacht area in the West of Ireland, the North West of Wales and the Province of Friesland in the North West of the Netherlands. This is also the case in the Basque Country, and the areas with a higher concentration of Basque speakers today are those that traditionally had less contact with Spanish or French. Nowadays, speakers of minority languages are in a different situation and are no longer isolated. In fact, there are many occasions when direct contact with speakers of other languages is possible because of, among other reasons, the increased mobility of the Basque and non-Basque population. More recently, the internet and social media have also contributed to increasing opportunities of contact among speakers of different languages.

Traditionally, schools have followed a policy of strict language separation so as to protect and develop proficiency in minority languages. In Basque-medium schools, the policy most often adopted is to correct students every time they use Spanish in order to learn better Basque and use it as much as possible. In some schools, there is the figure of Argitxo, a magic gnome who becomes sad when Basque is not spoken. Argitxo can be a puppet, a drawing or even a person dressed up as a gnome, who has a disciplinary effect on mainly the younger children. In the Basque Autonomous Community, students with Basque as the language of instruction also study Spanish and English, but the idea is to establish hard boundaries between languages and to keep them separate at all times. As far as possible, there are different teachers for different languages. The syllabuses for each language are in most cases completely independent. Following Cummins’ (Citation2007) ‘two solitudes’, we could say that there are ‘three solitudes’ when looking at the way languages are separated in Basque schools. Using resources from other languages in spontaneous translanguaging does happen, but it is generally frowned upon. Attitudes towards translanguaging are as negative as in the example of the Basque-speaking farmer trying to speak Spanish in the opening sentence, but now the target language is Basque, not Spanish. Nowadays, schoolchildren are not ridiculed for the way they speak, but there is concern about the quality of the language they use. It should be mentioned that these same learners who translanguage when speaking Basque do not usually translanguage when they speak Spanish. Musk (Citation2010) reports a similar state of affairs for Welsh bilingual education and he adds that the monolingual norm is enforced not only by teachers but also by the peer group, while at the same time the default medium of language use is a mixture of Welsh as a base language and with English language insertions.

In the Basque Country, there is concern about the quality of Basque when it is intermixed with Spanish. The worry comes from a fear that the language will disappear and may become a pidgin language (Zarraga Citation2014). This concern for purism is quite common in other contexts, as Jørgensen (Citation2005, 393) points out:

Even teachers and parents who favor bilingualism often think that children should speak both languages ‘purely’, without traces of the other language they know, simply because languages should be pure.

Some educators consider that the only way to save Basque is to make the oral use of the language compulsory so that schoolchildren in Basque-medium schools are obliged to use Basque. Their belief is that using Spanish in a Basque-medium school is a disruption. According to this perspective, the oral use of Basque should go from being desirable to being an obligation that is regulated by the school after it has been demanded and approved by parents (Hidalgo Citation2014). This seems to be a very strict approach, particularly because the whole school would need to adopt it in unison, but it is similar to monolingual policies in which the first language is avoided when teaching a foreign language.

Even though ideologies based on purism, the isolation of the minority language and the avoidance of translanguaging are widespread, they can also have a negative influence on language use. The following comment on an online discussion forum about the way young people translanguage shows how it can have a negative effect on the use of Basque.

Oraingo euskaldun gaztetxoak, euskaraz egitera ausartzen ez direnak, txiki-txikitatik gehiegizko zentsura jaso dutelako, euskañolez hitz egiteaz akusatu ditugulako etengabe, edo hizkuntzak eman behar zien freskotasun eta askatasuna ukatu diegulako, beharbada. (Alkaterri Citation2010)

(Translation: Young Basque speakers don’t dare to use Basque because they have suffered censorship from an early age, they have been accused of using euskañol all the time; perhaps we have denied them the freshness and freedom they needed to find in a language)

Osterkorn and Vetter (Citation2015) observed that students used different strategies to translanguage in spite of the language separation practices that were established in Breton-medium schools. These authors believe that the language separation perspective brings ‘emotional disempowerment of the young speakers’ (Osterkorn and Vetter Citation2015, 136). They then go on to quote Hélot and Young (Citation2006) because they consider it advantageous to have a multilingual school where children can use their home language and where all the languages in the plurilingual repertoire are valued. Even though both Osterkorn and Vetter (Citation2015) and Hélot and Young (Citation2006) refer to education in France, the two contexts are completely different and it is difficult to maintain the comparison. Hélot and Young are referring to the Didenheim School Project in the Alsace where the aim is to develop language awareness in the classroom among students from a wide range of different home languages. The idea is that children become aware of language and cultural diversity in classes with children who speak up to 18 different home languages and only 5 of them are taught at school. In contrast, the students in Breton-medium schools are either learning through their first language if this is Breton or through the medium of the second language when their first language is French. In the latter case, opting for Breton as the language of instruction is a choice made by their parents who could have chosen French instead. Moreover, all students have plenty of opportunities to use French both at school and outside school. Obviously, this is not the case for Turkish, Arabic or other foreign students in the Alsace where Turkish, Arabic or other languages are not valued as much as French in France (including Brittany). It seems rather unlikely that French first language speakers in a Breton medium school are emotionally disempowered when French is the majority language. French L1 students in Breton schools are certainly in a completely different situation as compared to students with different language backgrounds at the multilingual schools discussed by Hélot and Young (Citation2006). However, the proposal made by Hélot and Young (Citation2006) to recognise the plurilingual repertoire of the children and to use it as a resource can also be applicable to regional minority languages.

Regional minority languages today face different challenges compared to some years ago. Spontaneous translanguaging is natural for speakers who are bilingual but the question is how translanguaging can be compatible with the efforts to maintain and promote these weaker languages. The wider social context is an extremely important consideration. As we have seen, the situation of immigrant children in a language awareness project in Alsace is completely different from that of children with French as a first language in Breton-medium schools in Brittany. In a similar vein, the situation of translanguaging in the case of English-Spanish bilinguals in the US is also different from that of speakers of regional minority languages. Translanguaging can be a tool for empowering language minority students in the US because it accepts the way bilinguals communicate. The direction is then ‘from the minority to the majority’ because it legitimises the features that bilinguals have in their whole linguistic repertoire and takes them to spaces where English (and in some cases Spanish) is the main language. In this context, both languages, English and Spanish, are strong.

When referring to regional minority languages, however, translanguaging goes in the opposite direction, ‘from the majority to the minority’ and this is related to the differences in status and demography of the languages involved. Even if a few features associated with the minority language (phonetic, lexical, syntactic and pragmatic) can be identified when the majority language is spoken in bilingual regions, those features are minimal as compared to the mixed default medium used by bilingual speakers (Musk Citation2010). Lewis, Jones and Baker (Citation2012a, 649) show their concern ‘the promotion of flexible language arrangements such as translanguaging [that] could easily encourage pupils to focus more on the majority languages’.

This is an idea shared by a Basque teacher:

The weakness of Basque in comparison to the Spanish language is clear. Despite the fact that translanguaging can be positive, I think that its implementation in our schools needs deep reflection and a singular approach. (personal communication)

The potential problems associated with translanguaging in situations with regional minority languages come from the imbalance in status and power between the languages. The majority languages will be there even if some minor features from the minority languages are inserted. It is not clear though whether (if) languages such as Basque, Welsh or Breton will have a future if there is a massive insertion of features from majority languages. It would be ironic that, at least in the case of Basque, the increase in spontaneous translanguaging is in part a consequence of the success of language policies to promote the Basque language. As we saw before, Basque is presently the main language of instruction for most students in the Basque Autonomous Community. However, many of these students feel more comfortable using Spanish because it is their home language, so when they speak or write in Basque, they incorporate features from Spanish.

The worry about translanguaging in the context of regional minority languages extends to pedagogical translanguaging in Wales. Jones and Lewis (Citation2014, 168) explain that in predominantly English-speaking areas, translanguaging has to be controlled because ‘there is a growing concern that allowing the use of English texts for translanguaging purposes might be a stepping-stone for introducing more of the majority language (English)’.

Towards sustainable translanguaging for minority languages

Schools that promote regional minority languages not only aim to teach languages but also to develop the proficiency and use of the minority language. This aim has some implications when compared to other educational contexts. In schools with a minority language as the language of instruction, there is an extra task to fulfil. Schoolchildren not only have to develop literacy skills in at least two languages (the majority and the minority) but they also need to develop basic communicative skills for informal interaction in the minority language. This is necessary to compensate for the socio-linguistic situation because in many cases, informal skills cannot be developed naturally through social interaction as the majority language has a very strong presence.

As we have already seen, regional minority languages are vulnerable and their situation is dynamic. Most minority languages do not acquire the same legal status or receive the same funding as the majority language does. In the educational context, an extra effort has to be made to find enough teachers who are fluent in the language, and teaching materials are usually more limited. Many minority languages are still in the process of standardisation and there is a weak tradition of them being used in academic contexts.

In the past, regional minority languages survived by being relatively isolated but nowadays, in a globalised world, isolation would be neither realistic nor desirable. These days, minority languages face new challenges derived from globalisation and the mobility of the population. Ideologies that have been useful to promote minority languages in the past need to be adapted to respond to these new challenges. Translanguaging has been always a characteristic of bilingual and multilingual speakers, but it was not as widespread in the past when there were still monolingual speakers of regional minority languages with little contact with majority language speakers. Languages such as Basque or Welsh were in comfort areas and they are now facing intense contact with other languages.

With this in mind, new strategies for protecting and developing regional minority languages have to be designed. Could translanguaging be seen as an opportunity instead of a threat? We argue that this is a possibility worth exploring if certain factors are taken into account, such as the specific context of the regional minority language and the aims of schools in the regions where these languages are spoken. We argue that translanguaging could be sustainable for regional minority languages if some principles are applied ().

Table 1. Guiding principles for sustainable translanguaging for regional minority languages.

The first principle underlies the design of breathing spaces for using the minority language at school. The concept of breathing space was mentioned by Fishman (Citation1991, 59) and the idea is that the minority language can be used freely and without the threat of the majority language; it can ‘breathe’, in a space where only the minority is spoken. Such a space could be a village, an area, a classroom or a school. Regarding sustainable translanguaging in the context of bilingual and multilingual education, this principle underlies the need to create spaces where only the minority language is spoken. Without using the term ‘breathing spaces’, the need for separate spaces has also been highlighted by García (Citation2009, 301) when discussing minority languages and she says that ‘it is important to preserve a space, although not a rigid or static place, in which the minority language does not compete with the majority language’. Cummins (Citation2007, 229), who criticises the isolation of languages in immersion education in Canada, also sees the need for these spaces arguing that ‘it does seem reasonable to create largely separate spaces for each language within a bilingual or immersion program’. Even though this principle can be seen as linked to traditional practices of language isolation, it differs from these practices because schoolchildren will have breathing spaces along with pedagogical practices based on translanguaging as can be seen in the rest of the guiding principles.

The second principle underpins the need to use the minority languages through translanguaging. The idea is that minority languages will not be used if they are not necessary. A discourse strategy that is becoming quite common in the Basque Country is to translanguage in official speeches without providing translation. For example, the rector of the University of the Basque Country alternates Basque and Spanish several times in an official speech, giving different content in each of the languages. This means that a Basque–Spanish bilingual speaker can follow the whole speech but a monolingual Spanish speaker will have gaps because s/he does not understand the parts of the speech that are in Basque. This planned and almost pedagogical translanguaging strategy creates the need to understand both the majority and the minority language in order to follow the whole speech.

The third principle underlies the use of emergent multilinguals’ resources to reinforce all languages by developing metalinguistic awareness. It includes pedagogical translanguaging as proposed in Welsh bilingual education to promote a deeper understanding of language and content (Cummins Citation2007; Lewis, Jones, and Baker Citation2012a) but it expands on the original idea of translanguaging by adding other strategies to develop morphological, lexical and textual awareness in order to activate students’ prior knowledge. The idea is that students use the resources in their whole linguistic repertoire, in other words, (that) they behave like multilinguals when learning languages and when learning through the medium of different languages (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2013, Citation2015). Activating learners’ pre-existing knowledge and building on it can improve learning and gives students the opportunity to see similarities and differences between languages (Escamilla et al. Citation2013; Cummins Citation2014). It creates enhanced metalinguistic awareness among multilingual speakers.

Below are some strategies to activate the multilingual learners’ whole repertoire:

| - | To develop connections between cognates in different languages so as to develop vocabulary in the different languages (Cummins Citation2014; Arteagoitia and Howard Citation2015); This can work better for languages that are closely related, but as Otwinowska (Citation2015) shows, it also works for languages that are distant such as Polish and English. | ||||

| - | To develop morphological awareness by comparing compounds and derivation in different languages (see, for example, Lyster, Quiroga, and Ballinger Citation2013). | ||||

| - | To develop writing skills across languages (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2011; Escamilla et al. Citation2013). | ||||

| - | To use translation and bilingual readers (Cummins Citation2007). | ||||

The fourth principle relates to language awareness by exploring the knowledge students have about the social status, functioning, language practices and the use of different languages in society. Being aware of the different languages can contribute to understanding the role of minority languages and their situation. Language awareness is also crucial because it can contribute to the development of multilingual identities in classes with an increasing number of students from different linguistic backgrounds.

The fifth principle underlies the need to make the link between spontaneous and pedagogical translanguaging. This is particularly important in the case of regional minority languages because the school has to contribute to the development of basic communicative skills for informal interaction. Schools will not be successful in this task if they do not take as a point of departure the way students communicate with each other. Translingual practices are situationally constructed and learners use features from the different languages in their repertoire when they spontaneously translanguage and develop their identities through these practices (see also Canagarajah Citation2015). Sustainable translanguaging cannot ignore spontaneous translanguaging, but it can raise students’ awareness about the different contexts and uses of the minority languages.

Final remarks

Translanguaging is a recent and extremely successful concept in the area of bilingual and multilingual education that has gained wide acceptance in the literature in a short period of time. It is, however, understood in different ways and used for different approaches in educational contexts (Lewis, Jones, and Baker Citation2012a; García and Li Citation2014). This is positive because it opens new ways of looking at multilingual speakers and emergent multilinguals using a multilingual lens instead of traditional monolingual perspective. However, there is also a risk. The celebration of translanguaging without taking into consideration the specific characteristics of the socio-linguistic context can have a negative effect on regional minority languages.

It is necessary to soften the boundaries between languages in bilingual and multilingual schools involving regional minority languages, but this has to be done in a sustainable way. Educational policies to promote minority languages cannot ignore the new trends in multilingualism because these are closely linked to learning theories, the way bilinguals and multilinguals communicate and the characteristics of the world today. At the same time, translanguaging in these contexts will only be sustainable if it is rooted in the reality of minority languages and allows for breathing spaces that create the need to use these languages. Sustainable translanguaging implies a difficult balance between using resources from the multilingual learner’s whole repertoire and shaping contexts to use the minority languages on its own, along with contexts where two or more languages are used. We argue that sustainable translanguaging is firmly linked to both language awareness and metalinguistic awareness.

While sustainable translanguaging is unlikely to remedy the vulnerable situation of regional minority languages, it can provide the basis for new discussions on the challenges faced by regional minority languages in twenty-first century in the light of the new trends in the study of multilingualism.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Jasone Cenoz http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9000-7510

Durk Gorter http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8379-558X

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alkaterri, R. 2010. “Tradizioak hala dio, eta zer?” http://www.erabili.eus/zer_berri/muinetik/1266837499/1266914606/.

- Arteagoitia, I., and E. R. Howard. 2015. “The Role of the Native Language in the Literacy Development of Latino Students in the U.S.” In Multilingual Education: Between Language Learning and Translanguaging, edited by J. Cenoz and D. Gorter, 89–115. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Basque Government. 2012. Fifth Sociolinguistic Survey: Basque Autonomous Community, Navarre and Iparralde. Donostia-San Sebastián: Basque Government.

- Basque Government. 2013. Taking Pupils. The Arrue Project 2011. Vitoria-Gasteiz: Basque Government.

- Canagarajah, S. 2011. “Codemeshing in Academic Writing: Identifying Teachable Strategies of Translanguaging.” Modern Language Journal 95: 401–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01207.x

- Canagarajah, A. S. 2013. Translingual Practice: Global Englishes and Cosmopolitan Relations. New York: Routledge.

- Canagarajah, S. 2015. “Clarifying the Relationship Between Translingual Practice and L2 Writing: Addressing Learner Identities.” Applied Linguistics Review 6: 415–440. doi: 10.1515/applirev-2015-0020

- Cenoz, J., and D. Gorter. 2011. “Focus on Multilingualism: A Study of Trilingual Writing.” Modern Language Journal 95: 356–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01206.x

- Cenoz, J., and D. Gorter. 2013. “Towards a Plurilingual Approach in English Language Teaching: Softening the Boundaries between Languages.” TESOL Quarterly 47: 591–599. doi: 10.1002/tesq.121

- Cenoz, J., and D. Gorter, eds. 2015. Multilingual Education: Between Language Learning and Translanguaging. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Conteh, J., and G. Meier. 2014. The Multilingual Turn in Languages Education: Opportunities and Challenges. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Cook, V. 1999. “Going Beyond the Native Speaker in Language Teaching.” TESOL Quarterly 33: 185–209. doi: 10.2307/3587717

- Creese, A., and A. Blackledge. 2010. “Translanguaging in the Bilingual Classroom: A Pedagogy for Learning and Teaching.” Modern Language Journal 94: 103–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00986.x

- Cummins, J. 2007. “Rethinking Monolingual Instructional Strategies in Multilingual Classrooms.” Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics 10: 221–240.

- Cummins, J. 2014. “Rethinking Pedagogical Assumptions in Canadian French Immersion Programs.” Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education 2: 3–22. doi: 10.1075/jicb.2.1.01cum

- Edwards, J. 2012. Multilingualism: Understanding Linguistic Diversity. London: Continuum.

- Escamilla, K., S. Hopewell, S. Butvilofsky, W. Sparrow, L. Soltero-González, O. Ruiz-Figueroa, and M. Escamilla. 2013. Biliteracy from the Start: Literacy Squared in Action. Philadelphia, PA: Caslon.

- Fishman, J. A. 1991. Reversing Language Shift: Theoretical and Empirical Foundations of Assistance to Threatened Languages. Philadelphia, PA: Multilingual Matters.

- García, O. 2009. Bilingual Education in the 21st Century: A Global Perspective. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- García, O., and W. Li. 2014. Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gort, M., and S. F. Sembiante. 2015. “Navigating Hybridized Language Learning Spaces Through Translanguaging Pedagogy: Dual Language Preschool Teachers” Languaging Practices in Support of Emergent Bilingual Children’s Performance of Academic Discourse.” International Multilingual Research Journal 9: 7–25. doi: 10.1080/19313152.2014.981775

- Gorter, D., V. Zenotz, X. Etxague, and J. Cenoz. 2014. “Multilingualism and European Minority Languages: The Case of Basque.” In Minority Languages and Multilingual Education: Bridging the Local and the Global, edited by D. Gorter, V. Zenotz, and J. Cenoz, 278–301. Berlin: Springer.

- Grosjean, F. 1985. “The Bilingual as a Competent but Specific Speaker-Hearer.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 6: 467–477. doi: 10.1080/01434632.1985.9994221

- Hélot, C., and A. M. De Mejía. 2008. “Introduction: Different Spaces-Different Languages Integrated Perspectives on Bilingual Education in Majority and Minority Settings.” In Forging Multilingual Spaces: Integrated Perspectives on Majority and Minority Bilingual Education, edited by C. Hélot and A. M. De Mejía, 1–30. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Hélot, C., and A. Young. 2006. “Imagining Multilingual Education in France: A Language and Cultural Awareness Project at Primary Level.” In Imagining Multilingual Schools, edited by O. García, T. Skutnabb-Kangas, and M. E. Torres Guzman, 69–90. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Hickey, T. 2001. “Mixing Beginners and Native Speakers in Minority Language Immersion: Who is Immersing Whom?” The Canadian Modern Language Review 57: 443–474. doi: 10.3138/cmlr.57.3.443

- Hidalgo, B. 2014. “D ereduan espainolez? Ez, ez?” Berria October, 29.

- Jones, B., and W. G. Lewis. 2014. “Language Arrangements Within Bilingual Education in Wales.” In Advances in the Study of Bilingualism, edited by E. M. Thomas and I. Mennen, 141–170. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Jørgensen, J. N. 2005. “Plurilingual Conversations among Bilingual Adolescents.” Journal of Pragmatics 37: 391–402. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2004.10.009

- Lewis, G., B. Jones, and C. Baker. 2012a. “Translanguaging: Origins and Development from School to Street and Beyond.” Educational Research and Evaluation: An International Journal on Theory and Practice 18: 641–654. doi: 10.1080/13803611.2012.718488

- Lewis, G., B. Jones, and C. Baker. 2012b. “Translanguaging: Developing its Conceptualisation and Contextualization.” Educational Research and Evaluation: An International Journal on Theory and Practice 18: 655–670. doi: 10.1080/13803611.2012.718490

- Li, W. 2011. “Multilinguality, Multimodality and Multicompetence: Code- and Mode-Switching by Minority Ethnic Children in Complementary Schools.” Modern Language Journal 95: 370–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01209.x

- Llurda, E., J. M. Cots, and L. Armengol. 2013. “Expanding Language Borders in a Bilingual Institution Aiming at Trilingualism.” In Language Alternation, Language Choice, and Language Encounter in International Tertiary Education, edited by H. Haberland, D. Lonsman, and B. Preisler, 203–222. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Lowman, C., T. Fitzgerald, P. Rapira, and R. Clark. 2007. “First Language Literacy Skill Transfer in a Second Language Learning Environment: Strategies for Biliteracy.” SET 2: 24–28.

- Lyster, R., J. Quiroga, and S. Ballinger. 2013. “The Effects of Biliteracy Instruction on Morphological Awareness.” Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education 1: 169–197. doi: 10.1075/jicb.1.2.02lys

- Martin-Beltrán, M. 2014. ““What do you Want to say? How Adolescents use Translanguaging to Expand Learning Opportunities.” International Multilingual Research Journal 8: 208–230. doi: 10.1080/19313152.2014.914372

- Martínez-Roldán, C. M. 2015. “Translanguaging Practices as Mobilization of Linguistic Resources in a Spanish/English Bilingual After-School Program: An Analysis of Contradictions.” International Multilingual Research Journal 9: 43–58. doi: 10.1080/19313152.2014.982442

- May, S. 2000. “Uncommon Languages: The Challenges and Possibilities of Minority Language Rights.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 21: 366–385. doi: 10.1080/01434630008666411

- May, S. ed. 2014. The Multilingual Turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL, and Bilingual Education. New York: Routledge.

- Musk, N. 2010. “Code-switching and Code-Mixing in Welsh Bilinguals” Talk: Confirming or Refuting the Maintenance of Language Boundaries?” Language, Culture and Curriculum 23: 179–197. doi: 10.1080/07908318.2010.515993

- Osterkorn, P., and E. Vetter. 2015. “Le Multilinguisme en Question? The Case of Minority Language Education in Brittany (France).” In The Multilingual Challenge: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives, edited by C. Kramsch and U. Jessner, 115–139. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Otheguy, R., O. García, and W. Reid. 2015. “Clarifying Translanguaging and Deconstructing Named Languages: A Perspective from Linguistics.” Applied Linguistics Review 6: 281–307. doi: 10.1515/applirev-2015-0014

- Otwinowska, A. 2015. Cognate Vocabulary in Language Acquisition and Use: Attitudes, Awareness, Activation. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Paquet-Gauthier, M., and S. Beaulieu. 2016. “Can Language Classrooms Take the Multilingual Turn?” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 37: 167–183. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2015.1049180

- Zabala, J. 2015. https://twitter.com/sarean/status/598465893992103936.

- Zarraga, A. 2014. “Hizkuntza-ukipenaren ondorioak.” http://www.erabili.eus/zer_berri/muinetik/1410777403/1410864140%202014-09-16/12:42/.