ABSTRACT

This study responds to calls for more research on motivations for learning languages other than English (LOTEs) in the new era dominated by global English. In particular, it focuses on the role of societal contextual factors surrounding the status of English and the status of the LOTE as an L2/L3, as factors which may offer a more nuanced understanding of motivation in the case of LOTE learning. It presents a comparative quantitative analysis of a series of motivational constructs among 527 university learners of French in four European countries, chosen to reflect the differential status of English in their respective societies: L1 in England and Ireland, L2 in Sweden and foreign language (FL) in Poland. While the relative importance assigned by the learners to the motivational constructs examined was found to be remarkably similar across the four countries, the highest levels of motivation were observed among learners in the two L1-English countries (England and Ireland). The findings are discussed in terms of the societal status of English within the context of the potential relationship holding between L2 and L3 motivation.

Introduction

In the context of buoyant research on individual differences in second language (L2) acquisition, learner motivation has received substantial renewed attention in recent decades. Spurred on by a paradigm shift in the field prompted by the linguistic consequences of globalisation and poststructuralist conceptions of identity, a wave of new research has focused in particular on motivations for learning English in the current global era (Boo, Dörnyei, and Ryan Citation2015). In more recent years, however, the overwhelming focus on learners of English has seen calls for a better understanding of motivations for learning languages other than English (LOTEs), as well as of the motivational relationship between English and LOTE learning. As Ushioda and Dörnyei (Citation2017, 452) write: ‘What impact does global English have on motivation to learn other second or foreign languages in a globalized yet multicultural and multilingual world?’

Part of a larger project on LOTE motivation (see Oakes and Howard Citation2019), this article contributes to this underdeveloped aspect of motivation theory, where English has privileged status as the global lingua franca of our time, giving rise to the question of the potential impact on LOTE motivation among both L1-anglophone speakers and non-L1-anglophone speakers. While previous research has frequently investigated motivation amongst school-age learners, the present study focuses on the lesser-examined subject of university learners who voluntarily choose to study a LOTE (in this case French), unlike their school-level counterparts for whom foreign language learning is often obligatory. Against this background, the study explores the role of contextual differences in LOTE learning, adopting a comparative perspective across four European countries chosen to reflect the varying degrees of the societal status of English: England, where English has sole L1 status; Ireland, where its L1 status is shared with L2 Irish; Sweden, where its use in the media, education and social contexts attests to its L2 status; and Poland, where it remains a foreign language (FL). The aim is to explore the possible effect of the differences related to the broader societal status of English on motivations amongst university learners of French in those countries. Indeed, as Lanvers (Citation2017a, 518) suggests, ‘cross-national comparisons might do well to measure motivation for languages other than English.’ As such, the study makes a distinction between LOTE learners in L1-English contexts, on the one hand, and their counterparts in non-L1-English contexts, on the other. In the former context, LOTEs are generally learnt as an L2, at least in the case of the first LOTE learnt, while in the latter context, LOTEs are now predominantly learnt as an L3, following on from English as the first language learnt as an L2. The LOTE thus assumes differential L2-L3 status, giving rise to potential motivational differences between L1-English and non-L1-English learners. Such issues are considered in the context of Henry’s (Citation2012, Citation2017) suggestion that learners have finite motivational resources, which may be differentially activated in the case of English and LOTEs as a function of their L2 versus L3 status within the learner’s motivational repertoire.

The current study draws on a broad range of motivational constructs discussed in the literature in recognition of their complementary rather than mutually exclusive nature (e.g. Sugita McEown, Noels, and Chafee Citation2014), especially in the context of LOTE learning (Oakes and Howard Citation2019). While the L2 Motivational Self System (L2MSS) (Dörnyei Citation2005, Citation2009) has proven particularly popular as a theoretical framework for much recent research on global English, it has been less applied to the learning of LOTEs. It explains motivation principally in terms of two self-guides: the ideal L2 self refers to an individual’s desire to narrow the gap between their current self-conception as an L2 speaker and that desired in the future, while the ought-to L2 self reflects external influences such as parental pressure. While the self-guides have been supported in a range of studies of L2 English, other constructs are seen to also hold relevance for LOTE learners. For example, Noels (Citation2001) draws on self-determination theory to offer the constructs of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, which focus respectively on the pleasure gained from language learning and external factors at play. Such constructs followed on the earlier traditional constructs of instrumental and integrative orientation (e.g. Gardner Citation1985), respectively relating to practical reasons for learning the language (e.g. the need to pass an exam), on the one hand, and the learner’s identification with the target language (TL) culture, on the other. Since LOTEs are inarguably more closely associated with their TL communities, integrative orientation in particular has the potential to play a more critical role than has been suggested for global English (see Al-Hoorie Citation2017).

Motivations for learning LOTEs

This section considers some topics in LOTE learner motivation, firstly in L1-anglophone contexts and then in non-L1-anglophone contexts. Particular attention is given to the countries included in the present study and to university learners as the learner cohort under investigation.

L1-anglophone learners

While the present study focuses on university learners, previous LOTE studies in anglophone contexts allow some comparative insights between such learners and their school-level counterparts. In the latter case, in the UK for example, studies highlight reduced levels of LOTE motivation compared with other subjects and declining motivation as learners progress through the school system (see e.g. Coleman, Galaczi, and Astruc Citation2007; Lanvers Citation2017a). Such studies often invoke a demotivating effect of English in so far as L1-anglophone learners already speak the global lingua franca, and are thus seen to assign little importance to foreign language skills (see Lanvers' Citation2017a state-of-the-art overview). While such trends give rise to concern for foreign language uptake and skills at school level in many anglophone societies, other work at university level points to a more positive profile (see Lanvers' Citation2017a overview), suggesting that limited motivation at school level can evolve to overcome any putative demotivating effect of English as learners progress to university, as discussed below. But while higher levels of motivation are observed across a range of studies of university learners in the UK for example, it is notable that such learners have made the voluntary decision to engage in LOTE learning, rendering their positive motivation unsurprising.

Some studies explore the different types of motivation that underpin such LOTE learning at university level. On this count, it is especially interesting that studies have found a complementary role for a wide range of motivation constructs, suggesting that it is not one construct alone that is at play, although some assume greater importance than others. For example, Busse and Williams (Citation2010) apply different constructs in a quantitative questionnaire study of 142 university learners of German in England. While greatest importance was assigned to desire for proficiency, intrinsic motivation and ideal L2 self, instrumental motivation was in turn assigned greater importance than integrative motivation. The ought-to L2 self was not found to be a construct contributing to the learners’ motivation. Busse (Citation2013) offers a further questionnaire study of 59 university learners of German in England, this time looking at correlations with self-efficacy beliefs – findings point to the role of the ideal L2 self and instrumental factors, but in contrast, integrative motivation was not found to be significant. In yet a further study, Busse and Walter (Citation2013) consider the role of intrinsic motivation among such university learners of German in England, finding a correlation with the learners’ self-perceived effort which was enhanced over the course of an academic year.

Oakes (Citation2013) applies the questionnaire from Busse and Williams' (Citation2010) study to 378 specialist and non-specialist learners of French and Spanish at a London university. The generally similar ranking in the importance assigned to the different constructs that he observes suggests a complementarity of motivational sources. Drawing also on qualitative data, he further notes the learners’ rejection of a monoglot ‘English is enough’ culture in that they assigned critical value to their ability to use a foreign language in the future. For example, quotes provided by the participants clearly allude to their awareness of the limitations of an English-only monolingual mentality: ‘because most native English speakers don’t know a single foreign language. Naturally I want to learn this’, while others expressed clear awareness of the perception of poor foreign language skills among English speakers: ‘I feel embarrassed to be English as we are notorious for being reluctant to learn other languages’ (Oakes Citation2013, 185).

Lanvers (Citation2012) also reports a similar awareness of the disadvantages of English monolingualism among the mature university beginner students she interviewed at a British university. In a further large-scale study of 701 university learners across three different British universities (Lanvers Citation2017b), she offers quantitative evidence of such rejection of the notion that English as the global lingua franca makes LOTE learning unnecessary. Following on a variety of studies she conducted at university level in the UK, she interprets the findings as reflecting a ‘rebellious attitude’, whereby ‘learners are driven toward L2 learning as they reject the (felt) imposed self of the British as poor linguists’ (Lanvers Citation2017a, 523). Lanvers further notes how intrinsic motivation and the ideal L2 self in particular emerge at university level, in contrast with the more external instrumental and ought-to L2 self motivations that she suggests are evident at school level. At university level, the ideal L2 self construct would thus seem to assign a role for languages in the future conceptualisations of the self for such learners, with a rebellious attitude shaping that conceptualisation. Such an attitude is akin to Thompson’s (Citation2017) concept of the anti-ought-to self, reflecting a conscious decision on the part of the learner to study a LOTE contra external expectations. She portrays such a decision in terms of psychological reactance, with learners going against expected societal norms which do not value foreign language study.

Further work in the UK has looked at the relevance of other motivation constructs for LOTE learning. In the case of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, González-Becerra (Citation2019) offers a large-scale quantitative investigation among 363 university learners of various foreign languages. The learners were non-specialists of their language subject, specialising in a range of other subject areas. The questionnaire findings do not find evidence of such intrinsic or extrinsic motives at play, in contrast with more utilitarian motives relating for example to employability, on the one hand, and cultural curiosity, on the other hand. On the latter count, Stolte (Citation2015) also offers supporting evidence for integrative orientation. She uses interview data in a cross-sectional investigation of 25 learners of German at two different British universities. She offers evidence of both intrinsic and integrative factors at play, where the learners note their enjoyment of the language and interest in the language and culture. Indeed, such motives appear to be nurtured at school level, and further enhanced as the learners progress in their studies. Similar to Oakes and Lanvers, she also finds evidence of aspiration to competent plurilingualism which will distinguish the learners from their peers and members of the wider society who do not hold foreign language proficiency.

While less numerous, studies in Ireland, the other L1-anglophone context examined in this article, offer complementary insights on how such motivational constructs are considered of relevance. A case in point is Kam Kwok and Carson’s (Citation2018) study of Irish beginner university learners of Japanese. Based on a questionnaire study among 84 learners, the findings show integrative motivation as the only significant construct among six investigated, the others being L2 learning experience, intrinsic motivation, ideal L2 self, instrumentality, and ought-to L2 self. The authors suggest that the findings highlight the role of cultural identification in LOTE learning, calling into question the role of other constructs in such learning, such as the ideal L2 self. Similarly, Mannix (Citation2008) highlights cultural interest and attitudes among her tertiary-level students of German in Ireland. Her study is based on interviews with learners who have spent time abroad and those who have not. The interviews were subject to qualitative analysis of learner motivation more generally. The author suggests that the learners’ integrative interest was enhanced during a year abroad, while the learners were also found to evidence a more defined sense of self and future self after such residence abroad.

While there are obvious similarities between the contexts of England and Ireland in so far as LOTE learning takes place against the backdrop of L1 English, there is nonetheless an important difference. Unlike in England, French is generally learnt as an L3 in Ireland, on account of the L2 status of Irish within that country whereby Irish is learnt as an obligatory L2 throughout the school system. While existing studies of LOTE motivation provide important insights among L1-English learners in general, it remains unclear how LOTE motivation may be differentially shaped across L1-anglophone contexts, reflecting the role of context-specific features at play. In the Irish context, for example, LOTE motivation may be impacted by contextual differences concerning the L2-L3 status of the LOTE within the learner’s linguistic repertoire. Indeed, Henry (Citation2012) suggests that motivational resources are finite, such that they may not be equally distributed across additional languages within the learner’s repertoire. In his work with Swedish secondary school students learning L2 English and an L3 LOTE, he suggests that the learners may assign greater motivational resources to L2 English than their L3, reflecting the different status of the foreign language within their linguistic repertoire. While Henry’s findings stem from a non-L1-anglophone context, when applied within an L1-anglophone context, they raise unexplored questions among L1-anglophone learners concerning the role of L2 versus L3 status on LOTE motivation. For the purposes of the present study, it can be hypothesised that Irish LOTE-L3 learners may demonstrate more reduced motivation compared to the English LOTE-L2 learners. Henry’s work will be considered in more detail in the following section, as it emanates from his investigations of non-L1-anglophone learners.

Non-L1-anglophone LOTE learners

Non-L1-anglophone learners offer different insights into motivations for LOTE learning from anglophone learners, in that the majority will already have learnt English as an L2, with the LOTE thus assuming L3 status. This difference raises issues regarding the relationship between motivational constructs across languages within the learner’s linguistic repertoire. From this point of view, it can be considered that the various constituent languages are in a state of dynamic interaction such that it is too simplistic to consider that the learner simply switches off the L2 in favour of the L3 or that there is no difference in the acquisition process between L2 and L3 learning (for discussion, see Henry Citation2012). Rather, the first L2 learnt, as a constituent language within learners’ linguistic repertoires, carries important implications both at a crosslinguistic level in terms of psychotypology, but also in terms of the role of affective individual factors at play in the acquisition process, motivation included.

In the latter regard, while Henry (Citation2010) finds some evidence of different self-guides across languages among his Swedish secondary school learners of L3 French, he notes elsewhere (Henry Citation2017) that such differential self-guides are necessarily interconnected, interpenetrating systems with potential for competition, interference and cross-referencing to arise. At a competition level, Henry (Citation2012) suggests that, while the L2 and L3 self-guides may complement each other, one may become more dominant. In other words, the vitality of the L2 and L3 self-concepts may not necessarily be equal. While more generally considered in terms of crosslinguistic influence (see Odlin Citation1989), interference can also affect the self-guides across languages, which may interact to influence each other. Related to this is the issue of cross-referencing whereby the self-guides in each language can play a ‘supporter’ role, positively impacting motivation in the other language as the learner aspires to competent plurilingualism including both foreign languages. In contrast, one self-guide may be more active than the other, having a more detrimental impact on motivation levels in the other language.

Against this background, some LOTE studies within an L2MSS framework have sought to explore such issues in terms of the relationship between learners’ concurrent conceptions of themselves as speakers of different languages, offering evidence of the distinction between an L2 self-guide and an L3 self-guide. For example, in his work with Swedish school students of French, German or Spanish, Henry (Citation2010, Citation2011, Citation2012) argues that learners have a constantly shifting set of self-conceptions which are operational at any one time and which make up a larger working self-concept.Footnote1 He observes his learners engaging in cross-referencing between the self-concepts across languages, arguing that ‘motivation is unlikely to be evenly distributed among languages’ (Henry Citation2010, 149) due to finite motivational resources. In particular, his learners’ L3 LOTE self-concept was negatively impacted by their L2 English self-concept, suggesting that L2-L3 cross-referencing gave rise to low L3 motivation. Such findings raise the question of how the motivational relationship might differ if the L2 were not a high-status language such as English. On this count, in their study of Hungarian school-level learners of English and German, Csizér and Lukács (Citation2010) found that while L2 English had a demotivating effect on L3 German, no such effect was found for L2 German in relation to learning L3 English.

Complementing such work on the L2-L3 motivational relationship, other studies offer insight from the perspective of language attitudes in relation to the attitudinal value learners assign to English compared to a LOTE. In an ambitious large-scale cross-country comparison, Busse (Citation2017) investigates such language attitudes towards English language and LOTE learning, where the LOTE was the learners’ L3, among 2,255 adolescents in four European countries, namely Bulgaria, Germany, the Netherlands and Spain. The countries were chosen as a putative reflection of ‘their different historical, cultural, and linguistic influences on the experience of FL learning’ (Busse Citation2017, 567). Indeed, while the results point to overall more positive attitudes towards English compared with LOTE learning, attitudes towards the latter varied across countries. The author interprets such differences as an effect of macro-contextual factors in terms of the perceived societal importance of language learning in the different countries whereby language learning and LOTEs are valued more/less positively in the respective societies investigated.

Taken together, such findings provide important evidence of how motivation and attitudes may differ between L2 English and an L3 LOTE among school-level learners, but the question remains as to how they might apply at university level. From this point of view, there is no reason why Henry’s notion of finite motivational resources would not be equally valid in such a context. However, similar to L1-anglophone contexts, L1-non-anglophone contexts are not homogenous, as Busse’s study highlights for language attitudes, such that the impact of macro-contextual factors on LOTE motivational constructs similarly remains to be detailed. The two L1-non-anglophone countries under investigation here, namely Sweden and Poland, are a case in point, whereby English is seen to hold second language (L2) status in Sweden in comparison with the foreign language (FL) status it holds in Poland. A number of studies document the anglicisation of Swedish society in the media and everyday life beyond education, such that it is not viewed as a foreign language in the same way as other languages (see e.g. Falk Citation2001; Oakes Citation2001, 163–170; Henry and Cliffordson Citation2017, 719–720). While French as the LOTE under investigation undoubtedly constitutes an L3 for both Swedish and Polish learner cohorts, the question remains as to the impact of the status of English as an L2 versus FL on their L3 LOTE learning. On the one hand, following Henry’s findings at school level, it may be expected that no differences should arise between the Swedish and Polish participants given the L3 status of the LOTE within the linguistic repertoire of both groups. On the other hand, however, given the differential status of English as an L2 within those linguistic repertoires, differing levels of LOTE motivation may be expected.

While the L2-L3 relationship has previously been considered in relation to the self-guides posited by the L2MSS among school learners, some other studies both in Sweden and Poland have explored other constructs at university level. For example, in a Swedish context, Arvidsson and Forsberg Lundell (Citation2019) focus on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for LOTE learning in the case of French, against the background question of why Swedish students choose an additional language to English. Their small-scale quantitative study of 27 university students finds that the learners assign much greater importance to intrinsic motivation, reflecting their personal enjoyment of learning the language, with external factors considered to play a much smaller role. However, professional reasons are nonetheless cited by the learners in qualitative data when asked to provide reasons for their decision to study the language, pointing to some influence of instrumental motivation. Other reasons given reinforce the learners’ prior enjoyment of the language, along with cultural interest, thereby also suggesting a role for integrative motivation.

In a Polish context, Okuniewski (Citation2014) explores different motivational constructs among 247 learners of L3 German in secondary school and university contexts. Drawing on questionnaire data, the findings highlight higher motivation levels among the university learners compared to the school students across a number of constructs, namely integrative and instrumental motivation, and the ideal and ought-to L2 selves, while female learners generally showed higher levels of motivation than their male counterparts, with the exception of instrumental motivation. Okuniewski’s findings are interesting in that they complement findings in the L1-anglophone context of England, where motivation levels were seen to increase at university level, as reviewed above. Moreover, they also show the importance for LOTE motivation of different motivational constructs beyond the self-guides.

Against this background, the present study offers an exploratory investigation of the role of contextual issues in LOTE motivation with a cross-country comparative investigation of L1-English and non-L1-English LOTE learners, considering the differential role of L1-L2 English as a potential societal factor at play, along with the role of the LOTE as an L2-L3 for the learners. By taking account of the differential status that English holds for anglophone and non-anglophone learners at the societal level, the cross-country comparison of LOTE motivation presented here serves to enhance understanding of the differential role that English plays for LOTE learners at university level in different societal contexts.

Research questions

The study presented here thus investigates the following research questions:

How do the reported motivations of learners of French differ:

| RQ1 | in those countries where English has L1 status (England/Ireland) compared with where it does not (Sweden/Poland)? | ||||

| RQ2 | in the country where English has L1 status (England) compared with the country where it shares this status with another language (Ireland)? | ||||

| RQ3 | in the country where English has L2 status (Sweden) compared with the country where it has FL status (Poland)? | ||||

Methods

Instrument

As part of a larger project on LOTE motivation among university learners in the countries under investigation (see Oakes and Howard Citation2019 for a comparative investigation of motivation in English and French among Swedish and Polish participants), the study employed the same quantitative methods, adapting a questionnaire previously used in Oakes (Citation2013), which itself drew on earlier work by Busse and Williams (Citation2010). Recognising the potentially complementary nature of motivational constructs, the questionnaire was designed to tap into seven motivational orientations: the ideal L2 self, the ought-to L2 self, strong integrative orientation, weak integrative orientation, instrumental orientation, intrinsic motivation and desire for proficiency. Integrative orientation was sub-divided into two categories to reflect differing degrees of integrativeness: strong integrative relates to identification with the country and speakers of the language, whereas weak integrative concerns general interest in cultural aspects, such as film, literature and art. Extrinsic motivation was excluded on the grounds that it overlapped conceptually with the ought-to self and instrumental orientation. Desire for proficiency was included given that previous studies have identified it as carrying the greatest weight for learners (e.g. Busse and Williams Citation2010; Busse and Walter Citation2013; Oakes Citation2013). A series of four statements for each construct (see Appendix) elicited learner (dis)agreement, with responses on a five-point Likert scale (1-disagree completely, 2-disagree partially, 3-neither agree nor disagree, 4-agree partially, 5-agree completely). The questionnaire also included questions about linguistic background, length of study and self-reported proficiency in French.

Participants

The sample comprised university learners of French (N = 527) in the four European countries investigated: England (n = 123), Ireland (n = 178), Sweden (n = 101) and Poland (n = 125). Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and participants were recruited at two universities in England and Ireland, two universities in Sweden, and two in Poland. Native speakers of French were excluded, along with those who did not indicate an L1 but who were assumed to be native speakers based on responses to two qualitative questions, parental L1 and/or self-reported proficiency. Female participants dominated as a whole (n = 397, 75.3%), reflecting the generally higher proportion of females studying languages in European higher education (for a discussion on gender and language study, see Chavez Citation2001). The age range of participants was 17–35 years (M = 20.69, SD = 2.90).

The participants were specialist learners in so far as French was an integral part of their degree programme. While the latter may have included other subjects, including another language, such information was not elicited on the grounds that it would have given a diverse range of subject areas, which was not particularly relevant to the analysis. In all four contexts, there is a long tradition of teaching French as a LOTE at school level, often reflecting historical connections with France (see e.g. Ziolkowski Citation2004 on ties between France and Poland). This is not to say that its popularity has not waned in recent decades with the rise in importance of other LOTEs (e.g. Asian languages).

presents details of the participants’ prior length of study of French. That most participants in England and Ireland had studied French for longer than five years reflects study of the language at secondary school, while the lack of <1-year data was because French was not available at ab initio level in the English and Irish universities investigated. In contrast, some participants in both Sweden and Poland were learning the language for less than a year, reflecting that the language was available to them at ab initio level at university. The number of participants who had studied the language for more than five years in Sweden and Poland was also much less than in England and Ireland.

Table 1. Length of study of French.

Complementing the socio-biographical detail, presents the learners’ self-reported proficiency in French. Given their voluntary participation in the study, for time reasons, it was not feasible to set a language test that would map onto international proficiency scales (e.g. CEFR, ACTFL). Self-reported proficiency is, however, widely used in second language acquisition studies (e.g. see Dewaele and Dewaele Citation2021). It was measured here on a scale derived from responses to four questions (see Appendix) elicited on a five-point Likert scale: 1-very weak, 2-weak, 3-average, 4-good, 5-very good (Cronbach alpha = .86 overall; see table for individual country α values). The higher proficiency levels reported by the English and Irish participants is in line with their having learnt the language for longer. While these two factors may influence motivation in their own right, they were not the focus of this exploratory study. The differences observed for length of study and self-reported proficiency simply reflect the natural characteristics of the different learner cohorts examined.

Table 2. Self-reported proficiency in French.

Analysis

Factor analysis was first conducted in Jasp to explore the structure of the motivational constructs included. Considered more accurate than the Kaiser 1 rule or scree plots, parallel analysis was the method chosen to identify numbers of factors. As the latter were assumed to be intercorrelated, oblique rotation (Promax) was used for the interpretation of the results. Whereas seven factors were theorised, only six were extracted from the factor analysis. Specifically, there was some concern regarding discriminant validity given that many items for the ideal L2 self and intrinsic motivation loaded onto a single factor. It was therefore decided to exclude the four items designed to measure intrinsic motivation, not because this construct was deemed less valid than the ideal L2 self, but rather because one of the aims of the larger project was to investigate the applicability of the L2MSS self-guides, and in particular the ideal L2 self (see Oakes and Howard Citation2019). Two further items were also excluded on the basis of the factor analysis results. Item 24 (‘I am learning French because I would like to feel at ease in French-speaking countries’) did not load well onto any factor contrary to expectations that it would test for strong integrative orientation. Similarly, item 17 (‘I think knowing French will help me to become a more knowledgeable person’) loaded onto weak integrative orientation (.44) and strong integrative orientation (−.31) rather than instrumental orientation as expected. The fact that these items did not load onto the expected orientation category raises questions around their wording which is insightful for future studies. The results of the final factor analysis are shown in , while the reliability of the final scales is indicated in . That some of the Cronbach alpha values are below the generally acceptable value of .7 in some contexts but above it in others highlights the difficulty of establishing reliable scales for use in cross-country research where contextual factors are necessarily at play.

Table 3. Results of factor analysis.

Table 4. Scale reliability (Cronbach’s alpha).

The subsequent analyses (dependent and independent t-tests) were conducted in SPSS. For the country comparisons, a series of independent t-tests were chosen over a one-way ANOVA (four levels) as these were deemed to better address the research questions, which each involved an independent variable comprising only two levels (rather than four). Bonferroni corrections were nonetheless applied to compensate for the multiple comparisons.

Results

RQ1 How do the reported motivations of learners of French differ in those countries where English has L1 status (England/Ireland) compared with where it does not (Sweden/Poland)?

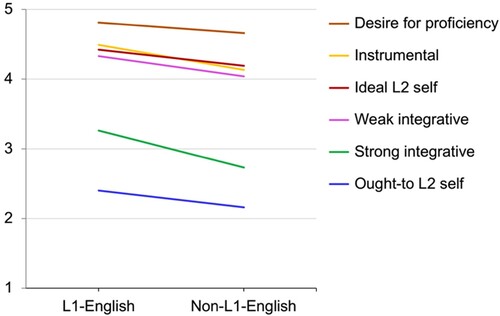

presents the results for each of the motivational constructs in terms first of a two-way comparison between the L1-English countries (England and Ireland) and the non-L1-English countries (Sweden and Poland), with showing the two sets of mean plots in graphic form.

Table 5. Results for L1-English vs. non-L1-English countries.

The first observation concerns the similarity in the relative ranking of the constructs across the two subsets of countries. In both cases, desire for proficiency was the highest-ranked construct. According to the results of dependent t-tests, next followed instrumental orientation or the ideal L2 self, with no significant differences between the two rankings in the L1-English countries (t(299) = 1.89, p = .060, d = 0.11) or non-L1-English countries (t(225) = −1.36, p = .177, d = −0.09). Weak integrative orientation was ranked the third highest construct, just below the ideal L2 self in the L1-English countries (t(299) = 2.57, p = .011, d = 0.15) and instrumental orientation in the non-L1-English countries, although the difference in the latter case was not significant (t(225) = 1.54, p = .126, d = 0.10). Strong integrative orientation was ranked much less highly than weak integrative orientation, with the learners in the non-L1-English countries (Sweden and Poland) disagreeing that this was an important construct. Finally, both subsets of learners disagreed that they were learning French for reasons related to the ought-to self, which was ranked last.

While the similarities in the relative rank ordering of the motivational are noteworthy, important differences in the strength of motivation constructs across the sub-groups can also be seen. Indeed and clearly reveal higher levels of motivation across the full range of constructs amongst the learners in the countries where English has L1 status compared to those where it does not. Such a finding reinforces previous work which reports high levels of motivation among university learners in L1-English countries, contra the putative demotivating effect of L1 English.

RQ2 How do the reported motivations of learners of French differ in the country where English has L1 status (England) compared with the country where it shares this status with another language (Ireland)?

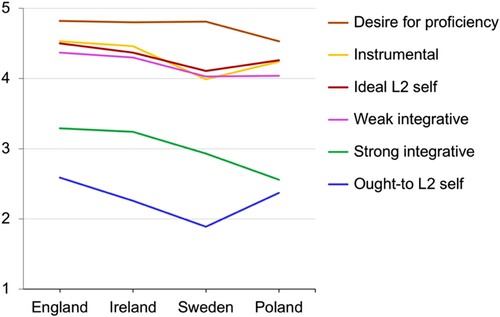

presents the results of country comparisons within the two sub-groups, while shows the mean plots in graphic form.

Table 6. Results for UK vs. Ireland and Sweden vs. Poland.

Only one significant difference was observed between England and Ireland. While the learners in these two countries both disagreed that factors related to the ought-to L2 self were a source of motivation, the learners in England disagreed less than their Irish counterparts.

RQ3 How do the reported motivations of learners of French differ in the country where English has L2 status (Sweden) compared with the country where it has FL status (Poland)?

In sum, while captures a general decrease in motivation from England through to Poland, the pattern is far from perfect. The greatest differences were observed between Sweden and Poland, with greater similarity between the learners in England and Ireland, suggesting that the difference in the L2 versus FL status of English between Sweden and Poland is a more important factor than that concerning its status in the two L1-English countries of England and Ireland.

Discussion

The results of the cross-country study undertaken offer a preliminary comparative profile of perceived motivational orientations at play among university specialist learners of French in the different European countries concerned. In one respect, the learners are remarkably similar with regard to the relative ranking of the constructs, pointing to the homogeneity of their motivational repertoires. A notable difference, however, concerns the role of a strong form of integrative motivation for the English and Irish learners, compared to the Swedish and Polish learners who did not agree that it carried importance for them.

Notwithstanding such relative similarities, the importance assigned to each construct is by no means uniform across the learners. RQ1 thus considered how such orientations may differ in terms of their relative importance as a function of the status of English in the countries concerned. The results demonstrate higher levels of motivation among the participants in the two L1-English countries (England and Ireland) compared with the two non-L1-English countries (Sweden and Poland), a finding which complements previous findings on the high levels of motivation observed among university learners of French in the UK, and runs counter to popular belief around the lack of motivation in foreign language study in L1-English countries, at least at university level.

One interpretation of this finding is offered by Henry’s (Citation2010) suggestion of finite motivation resources, whereby such resources may be predominantly channelled into the learning of the first foreign language, with fewer motivational resources available for the learning of additional languages. Since the participants in the non-L1-English countries of Sweden and Poland had presumably already learnt English as an L2, it follows that they would be less motivated to learn L3 French than the L1-anglophone learners, for whom French is mostly an L2. However, this does not explain the overall similarities between the participants in England and Ireland (RQ2), where the compulsory learning of Irish as an L2 in the school system also makes French an L3. It might therefore be expected that similar levels of motivation would have emerged across the Irish learners and their Swedish and Polish counterparts, but this is clearly not the case. Rather, in line with their English counterparts, the Irish learners demonstrate high levels of motivation, irrespective of the fact that French holds L3 status for them. An explanation for these similarities might lie in the widespread societal status enjoyed by Irish which, even if technically an L2, is by no means considered a foreign language in Ireland (Walsh, O’Rourke, and Rowland Citation2015). This may well open the way for a shift in motivational resources from L2 Irish to L3 French, which then ultimately holds similar motivational appeal as (mostly L2) French in England.

The shift of finite motivational resources across languages as proposed here is necessarily tentative and requires more controlled testing beyond the exploratory nature of the study presented here. In particular, it calls for a comparison of more homogenous groups in relation to some of the characteristics which limit the comparability of the groups in this study, such as in relation to proficiency level and prior length of study. Indeed, as previously noted, the English and Irish learners generally reported higher proficiency levels, along with longer length of prior study, such that they would seem to be more advanced than their Swedish and Polish counterparts. The higher levels of motivation that they evidence may thus be reflective of the fact that more advanced learners may be naturally more motivated as an outcome of their confidence in their language skills. However, if the L1-anglophone learners were more motivated for such reasons, it remains unclear why such factors of proficiency level and duration of prior study would not also give rise to lesser levels of motivation in similar measures among the Swedish and Polish learners, in so far as they both constituted the less proficient groups (see further below).

Notwithstanding the potential effect of additional factors, the consideration of the societal status of languages raises the possibility of an alternative interpretation for the higher levels of motivation observed among the participants in the two L1-English countries compared with the two non-L1-English countries. While the present study lacked a qualitative dimension allowing for further investigation of underlying factors, the findings are nonetheless in line with the qualitative insights of previous studies that have pointed to the role of English. In particular, these studies noted a rejection among L1-English LOTE learners of an ‘English is enough’ mentality and the perception of anglophones as poor linguists (e.g. Oakes Citation2013; Stolte Citation2015; Lanvers Citation2017a). In a world where English dominates as the global lingua franca, potentially reducing the need for anglophone learners to gain foreign language skills, the findings presented here offer additional quantitative evidence that the status of English may positively shape LOTE motivation at university level at least.

The findings concerning the final research question (RQ3) also illuminate issues in the relationship between L2 English and L3 LOTE motivation for the non-L1-English learners in Sweden and Poland. Given Henry’s suggestion of finite motivational resources and the fact French was undoubtedly an L3 in both Sweden and Poland, participants in both countries might have been expected to demonstrate reduced levels of motivation in similar measures. However, significant differences observed between the two countries for three of the six motivational constructs examined suggest a more complex picture, where the potential effect of the L3 status of French is mediated by other factors. Amongst such other mediating factors is the different societal status of English in the two countries. As noted previously, English in Sweden arguably enjoys L2 status as opposed to FL status; its use is widespread and skills in the language are deemed a fundamental form of literacy. In such a context, greater value might be assigned to skills in an additional language, compared with societies like Poland where English has only FL status and where English proficiency may be considered sufficient, without the need for an additional language. A second L2 beyond English may not stretch finite motivational resources among Swedish learners as much as it does for Polish learners. In this respect, the situation observed in this study among the Swedish learners may be comparable to that of the Irish learners: that English in Sweden and Irish in Ireland are not so much foreign languages as second languages may have resulted in a shift of motivational resources to L3 French. In sum, the findings for the learners in these two countries point to both an effect of the status of English for the learners and an L2-L3 effect. While it is not possible to distinguish between the two factors such that one may override the other, it is plausible that they interact to mutually shape the learners’ motivation in nuanced ways that remain to be explored in LOTE motivation research. Such research will benefit from more controlled experimental design which may tease out the relative effect of such factors.

Conclusion

This exploratory study highlights the nuanced ways in which the societal status of English in tandem with L2-L3 matters might positively shape LOTE motivation, be it among L1-English or non-L1-English learners. While previous studies have suggested relatively weaker vitality underpinning L3 motivation compared to L2 motivation given the finite motivation resources available to learners, the findings here suggest that the relationship is in fact more complex, with some learner groups evidencing higher L3 motivation levels than might be expected.

Considering the question posed by Ushioda and Dörnyei (Citation2017) concerning the impact of global English on LOTE motivation, the findings highlight the need to adopt a more nuanced lens. While some previous studies have generally illuminated the issue through exploratory L2/L3 comparisons of English and a LOTE within one specific learner cohort, the cross-country comparison presented here suggests that the underlying detail of how and why the impact of global English is realised may only become apparent through more comparative investigations of different learner cohorts. The specific findings presented highlight the role of factors at a societal level which may be propitious to a shift of motivational resources to the L3, but these factors would seem to impact the motivational constructs in complex ways, as evidenced by the Swedish participants who were both similar to and different from their Polish counterparts depending on the motivational construct concerned. While some examples of that complexity have been provided, they merely highlight how the status of English and the L2 versus L3 status of the LOTE may shape LOTE motivation in a myriad of ways that remain to be fully understood.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Leire Bustamante Törnqvist, Fanny Forsberg Lundell, Jonas Granfeldt, Francis Hult, Siniša Lakić, Erez Levon, Simone Morehed, Urszula Paprocka-Piotrowska, Marlena Siwek, Yang Ye, Hui Zhao and the participants in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Martin Howard

Martin Howard is currently Associate Dean in the College of Arts, Celtic Studies and Social Sciences at University College Cork. His research focuses on second language acquisition, especially in relation to French. He is founding editor of the journal, Study Abroad Research in Second Language Acquisition, and has previously led a European COST Action, Study Abroad Research in European Perspective.

Leigh Oakes

Leigh Oakes is Professor of French and Linguistics at Queen Mary University of London, UK. His research focuses on language policy and planning, language attitudes and ideologies, and motivation in second language acquisition. He is co-editor of Sociolinguistica and the Multilingual Matters book series.

Notes

1 In subsequent work, Henry (Citation2017) proposes the concept of the multilingual ideal self which serves as an overarching, unifying self which complements the specific self-guides in each language. It refers to the learner’s perception of him/herself as a multilingual speaker in a way that transcends his/her competence in specific languages, but emerging from the internal dynamics between the self-guides underpinning the different languages. See also Busse’s (Citation2015) concept of the ideal Bildungs-Selbst (educational training self), referring to the learner’s plurilingual aspirations in the future.

References

- Al-Hoorie, A. H. 2017. “Sixty Years of Language Motivation Research: Looking Back and Looking Forward.” SAGE Open 7 (1): 1–11.

- Arvidsson, K., and F. Forsberg Lundell. 2019. “Motivation pour apprendre le français chez les étudiants universitaires suédois – une étude de méthodes mixtes.” Synergies Pays Scandinaves 14: 95–108.

- Boo, Z., Z. Dörnyei, and S. Ryan. 2015. “L2 Motivation Research 2005–2014: Understanding a Publication Surge and a Changing Landscape.” System 55: 145–157.

- Busse, V. 2013. “An Exploration of Motivation and Self-Beliefs of First Year Students of German.” System 41: 379–398.

- Busse, V. 2015. “Überlegungen zur Förderung der deutschen Sprache an Englischen Universitäten aus Motivationspsychologischer Perspektive.” Deutsch als Fremdsprache 52: 172–182.

- Busse, V. 2017. “Plurilingualism in Europe: Exploring Attitudes Toward English and Other European Languages among Adolescents in Bulgaria, Germany, the Netherlands, and Spain.” Modern Language Journal 101: 566–582.

- Busse, V., and C. Walter. 2013. “Foreign Language Learning Motivation in Higher Education: a Longitudinal Study of Motivational Changes and their Causes.” Modern Language Journal 97: 435–456.

- Busse, V., and M. Williams. 2010. “Why German? Motivation of Students Studying German at English Universities.” The Language Learning Journal 38: 67–85.

- Chavez, M. 2001. Gender in the Language Classroom. San Francisco: McGraw Hill.

- Coleman, J., Á Galaczi, and L. Astruc. 2007. “Motivation of UK School Pupils Towards Foreign Languages: a Large-Scale Survey at Key Stage 3.” Language Learning Journal 35: 245–280.

- Csizér, K., and G. Lukács. 2010. “The Comparative Analysis of Motivation, Attitudes and Selves: the Case of English and German in Hungary.” System 38: 1–13.

- Dewaele, L., and J.-M. Dewaele. 2021. “Actual and Self-Perceived Linguistic Proficiency Gains in French During Study Abroad.” Languages 6: 1.

- Dörnyei, Z. 2005. The Psychology of the Language Learner: Individual Differences in Second Language Acquisition. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Dörnyei, Z. 2009. “The L2 Motivational Self.” In Motivation, Language Identity and the L2 Self, edited by Z. Dörnyei, and E. Ushioda, 9–42. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Falk, M. 2001. Domänförluster i Svenskan (Domain Loss in Swedish). Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers.

- Gardner, R. C. 1985. Social Psychology and Second Language Learning: The Role of Attitudes and Motivation. London: Edward Arnold.

- González-Becerra, I. 2019. “Language Learning among STEM Students: Motivational Profile and Attitudes of Undergraduates in a UK Institution.” Language Learning Journal 47: 385–401.

- Henry, A. 2010. “Contexts of Possibility in Simultaneous Language Learning: Using the L2 Motivational Self System to Assess the Impact of Global English.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 31: 149–162.

- Henry, A. 2011. “Examining the Impact of L2 English on L3 Selves: A Case Study.” International Journal of Multilingualism 8: 235–255.

- Henry, A. 2012. L3 Motivation. Doctoral dissertation. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg.

- Henry, A. 2017. “Rewarding Foreign Language Learning: Effects of the Swedish Grade Point Average Enhancement Initiative on Students’ Motivation to Learn French.” Language Learning Journal 45: 301–315.

- Henry, A., and C. Cliffordson. 2017. “The Impact of Out-Of-School Factors on Motivation to Learn English: Self-Discrepancies, Beliefs, and Experiences of Self-Authenticity.” Applied Linguistics 38: 713–736.

- Kam Kwok, C., and L. Carson. 2018. “Integrativeness and Intended Learning Effort in Language Learning Motivation Amongst Some Young Adult Learners of Japanese.” CercleS 8: 265–279.

- Lanvers, U. 2012. “‘The Danish Speak So Many Languages It’s Really Embarrassing’. The Impact of L1 English on Adult Language Students’ Motivation.” Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching 6 (2): 1–19.

- Lanvers, U. 2017a. “Contradictory Others and the Habitus of Languages: Surveying the L2 Motivation Landscape in the United Kingdom.” Modern Language Journal 101: 517–532.

- Lanvers, U. 2017b. “Language Learning Motivation, Global English and Study Modes: A Comparative Study.” The Language Learning Journal 45: 220–244.

- Mannix, V. 2008. Motivation, the Language Learner and Teacher. PhD thesis, University College Cork.

- Noels, K. A. 2001. “New Orientations in Language Learning Motivation: Towards a Model of Intrinsic, Extrinsic and Integrative Orientations and Motivation.” In Motivation and Second Language Acquisition, edited by Z. Dörnyei, and R. Schmidt, 43–68. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i.

- Oakes, L. 2001. Language and National Identity: Comparing France and Sweden. Amsterdam / Philadelphia: Benjamins.

- Oakes, L. 2013. “Foreign Language Learning in a ‘Monoglot Culture’: Motivational Variables amongst Students of French and Spanish at an English University.” System 41: 178–191.

- Oakes, L., and M. Howard. 2019. “Learning French as a Foreign Language in a Globalised World: an Empirical Critique of the L2 Motivational Self System.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism.

- Odlin, T. 1989. Language Transfer. Crosslinguistic Influence in Language Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Okuniewski, J. 2014. “Age and Gender Effects on Motivation and Attitudes in German Learning: the Polish Context.” Psychology of Language and Communication 18: 251–262.

- Stolte, R. 2015. German Language Learning in England. Understanding the Enthusiasts. PhD thesis, Southampton University.

- Sugita McEown, M., K. Noels, and K. E. Chafee. 2014. “At the Interface of the Socio-Educational Model, Self-Determination Theory and the L2 Motivational Self System.” In The Impact of Self-Concept on Language Learning, edited by K. Csizér, and M. Magid, 19–50. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Thompson, A. 2017. “Don’t Tell Me What to Do! The Anti-Ought-to Self and Language Learning Motivation.” System 67: 38–49.

- Ushioda, E., and Z. Dörnyei. 2017. “Beyond Global English: Motivation to Learn Languages in a Multicultural World: Introduction to the Special Issue.” The Modern Language Journal 101: 451–454.

- Walsh, J., B. O’Rourke, and H. Rowland. 2015. Research Report on New Speakers of Irish. Dublin: Foras na Gaeilge.

- Ziolkowski, M. 2004. “La francophonie en Pologne.” Hermès 40: 59–61.

Appendix: questionnaire items

* denotes deleted item

Ideal L2 self

6 Being able to converse in French is an important part of the person I want to become

9 If my dreams come true, I will use French effectively in the future

18 I can imagine myself as someone who is able to use French well

31 Whenever I think of my future, I imagine myself being able to use French

Ought-to L2 self

7 I consider learning French important because the people I respect think that I should do so

15 People around me (e.g. parents, partner) believe that I ought to study French

19 I study French because people around me expect me to do so

26 If I fail to learn French, I will be letting other people down

Strong integrative

11 I am studying French because I would like to live in a French-speaking country

20 Knowing French will allow me to become more like people from French-speaking countries

24* I am learning French because I would like to feel at ease in French-speaking countries

29 I like learning French because I feel an affinity with people in French-speaking countries

Weak integrative

10 Learning French provides an opportunity to appreciate a francophone way of life

14 Learning French will help me to better understand the cultures and societies of the French-speaking world

27 Knowing French allows me to enjoy interesting cultural activities in French (e.g. reading, watching movies, listening to music)

32 Studying French allows me to enjoy rich and diverse cultures

Instrumental

4 Knowing French will help me to obtain a better job

17* I think knowing French will help me to become a more knowledgeable person

25 I think French will help in my future career

33 Studying French will enhance my professional profile and CV

Intrinsic*

3* I really enjoy learning French

13* Learning French is one of the most important aspects of my life

22* It is personally satisfying to be able to communicate in French

28* I like the challenge of learning French

Desire for proficiency

1 I am studying French because I want to improve my French

2 By studying French I hope to improve my speaking skills in French

5 By studying French I hope to improve my reading skills in French

12 By studying French I hope to improve my written French

21 By studying French I hope to improve my listening comprehension in French

Self-reported proficiency

How would you rate your speaking skills in French?

How would you rate your listening skills in French?

How would you rate your writing skills in French?

How would you rate your reading skills in French?