ABSTRACT

This paper reports on a comparative case study of the multilingual practices of eight secondary teachers of English from across India, all identified as experts of their contexts using multiple criteria. Both qualitative and quantitative data from classroom observations, interviews and other sources were collected, analysed and compared across cases. It finds that, while there was noticeable variation among the participants, all engaged in complex translingual practices that were inclusive of their learners’ languages, invariably prioritising learner participation over language choice. It also finds that, in each context, learners invariably mirrored the varied translingual practices of their teachers, and that the practices of the classroom community were found to be reflective of practices in wider Indian society, enabling learners both to meet the normative requirements of monolingual written exams while also learning to integrate English more flexibly in their spoken repertoires. Given these findings, two recommendations are offered for educational policy and practice, both in India and comparable multilingual contexts across the Global South: for policy-makers and institutions to avoid the unqualified endorsement of monolingual target language (e.g. ‘English-only’) practices in language instruction, and for teachers to prioritise learner inclusion in classroom discourse and activities over maximal target language use.

Introduction

While the translanguaging literature continues to expand rapidly, including numerous studies on pedagogic practices in diverse fields including bilingual, immersion and content-based instruction (Li Citation2018), it is notable that there are, to date, comparatively few studies of translanguaging in countries in the Global South (Heugh Citation2021), including India (Anderson and Lightfoot Citation2021; Lightfoot et al. Citation2021), despite it today constituting the largest educational ‘ecosystem’ in the world, involving numerous curricular authorities and languages (Anderson and Lightfoot Citation2019). This paper aims to fill this gap by offering the first detailed account of the multilingual practices of teachers identified as experts from any context around the world. It reports on a subset of data from a comparative case study investigating the practices, cognition and professionalism of eight expert teachers of English working in government-sponsored secondary education in three different states (Maharashtra, Telangana, West Bengal) across India. It focuses specifically on the languaging practices observed in their classrooms – both of the teachers and their learners – to offer a more holistic account of multilingual practice than the many studies on ‘L1 use’ in FL/SL teaching have typically done (see Shin, Dixon, and Choi Citation2020).

The findings of this study are likely to be useful to researchers, policy makers and teacher educators working, both in India, and in other comparable (e.g. low-resource) multilingual contexts across the Global South, to inform the development of language policy, curricula and teacher education initiatives in such contexts. It also contributes to filling an important gap in the teacher expertise literature, concerning the practices of expert teachers working in multilingual contexts.

Theoretical framework: exploring translanguaging perspectives

Over the last decade, interest in translanguaging, both as a social phenomenon and pedagogic practice has increased rapidly, and both theoretical works on translanguaging (e.g. García and Li Citation2014; Leung and Valdés Citation2019) and research into specific translingual practices (e.g. Canagarajah Citation2011, Citation2018; Creese and Blackledge Citation2010; Li Citation2011) abound in the literature on multilingual education (Li Citation2018). Earlier theories of multilingual language use (e.g. code-switching and codemixing; Matras Citation2009) viewed the resources of multilinguals (e.g. lexical, grammatical, multimodal) as belonging to separate languages between which they sometimes ‘switched’ depending on situation and interlocutor. In contrast to this, translanguaging theory seeks to understand multilingualism more holistically, both how such resources exist within our cognition as a ‘repertoire’, and how we make use of them in practice, including in teaching and learning, ‘in order to maximise communicative potential’ (García Citation2009, 140; also Li Citation2018). Translanguaging is typically defined as the fluid, dynamic use of multiple resources from different named languages and dialects within a single integrated system (e.g. Canagarajah Citation2011; García and Lin Citation2017). As such, it enables us to better describe and understand practices previously characterised as codeswitching and codemixing. The ‘trans’ within the term can be understood to refer to a multilingual’s ability to transcend the traditional divides between named language systems (Anderson Citation2018; Li Citation2018).

Within this broad agreement in the translanguaging literature, differences are appearing. García and Lin (Citation2017) note the emergence of two, competing versions of translanguaging: a stronger version, which poses ‘that bilingual people do not speak languages but rather, use their repertoire of linguistic features selectively’, and a weaker version, which recognises the sociopolitical reality of ‘national and state language boundaries and yet calls for softening these boundaries’, recognising that such languages have ‘real and material consequences’ in educational settings (126). Given the context of this study (Indian secondary education), this paper leans towards the weaker version, without abandoning the metacognitive aspirations of the stronger version. It recognises both the normative pressure on teachers and learners to ‘teach’ and ‘study’ named languages, and the existence of needs and conventions that often transcend and subvert language boundaries, leading to multiple, complex practices, both purposeful and instinctual, within the classroom. While some authors (e.g. Canagarajah Citation2013) make a distinction between translanguaging and translingual practice, they are treated as broadly synonymous here; ‘translanguaging’ is used to describe specific acts, and ‘translingual practice’ the social activity of engaging in translanguaging.

Despite a long, well-documented history of research into multilingual practices in the Global South (e.g. Heugh, Citation2015; Probyn, Citation2009), it is notable that there has been relatively little research on translanguaging in Southern classrooms (Heugh Citation2021). Addressing this issue, Heugh discusses the danger of assuming north–south transferability of practices in this area, suggesting an alternative relationship:

… contemporary debates and responses to newly found northern multilingualism(s) are not necessarily superior to or transferable to educational settings in the Global South. Instead, there are sound arguments about why southern educators and scholars have considerable expertise of multilingualisms in education that can inform and enrich northern understandings of these phenomena. (38)

As such, there is much to be gained from studying the multilingual practices of expert teachers in the Global South. Recent studies, particularly in South Africa, indicate both positive impacts of translanguaging on learners’ receptive vocabulary pool and reasoning powers (Makalela Citation2015) as well as evidence of richer classroom dialogue and deeper understandings of content knowledge when translanguaging is encouraged (Probyn Citation2019). Makalela argues that the construct of translanguaging is compatible with the plural sense of shared being (an ubuntu identity) found across users of South Africa’s many language varieties and peoples, and both Makalela (Citation2015) and Probyn (Citation2019) argue that translanguaging may play a useful role in the move away from monolingual ideologies in post-colonial education.

Literature review

Languages and multilingualism in English language teaching in India

With over 400 named languages (Eberhard, Simons, and Fennig Citation2021) – possibly many more – India has a rich, well-documented history of multilingualism (Agnihotri Citation2014), and of complex, integrated language use practices ‘marked by fluidity’ (364). While these practices were previously discussed mainly as code-switching and codemeshing (e.g. Kachru Citation1978), they clearly fall under the wider umbrella of translanguaging, as adopted in this paper.

Due to its colonial past, English has played some role in India’s multilingual history. It is often described as a second language in India, due primarily to its role as a co-official language in national policy (see Anderson and Lightfoot Citation2019), although it is also used in certain discourse communities (often translingually – so-called ‘Hinglish’) within India’s small, but increasing middle class. However, for the majority of Indians, including school learners, English is ‘a completely foreign language’, which plays little role in their daily life outside of education (Mukherjee Citation2018, 126; also Rao Citation2013). As Annamalai argues (Citation2005, 35), ‘the ESL method is not best suited for teaching English to them; it must be combined with the principles of teaching English as a foreign language’. In education, policies differ between states and institutions; English is used as a school-wide medium of instruction only in some schools (most often in the private sector; Central Square Foundation Citation2020b), and in others, for selected subjects only (so-called ‘semi-English medium’) at secondary level, although English-medium instruction is increasing across the country at ever-earlier ages (Central Square Foundation Citation2020a).

The teaching of English as a subject at secondary level typically includes the teaching of basic literacy and language skills (mainly reading and writing) alongside literature studies (e.g. canonical ‘seen texts’ for exams, and a focus on literary features, such as metaphor, rhyme scheme, etc.; e.g. CBSE Citation2020). Despite often having little exposure to English outside the classroom, secondary learners across India are expected to answer exam questions on complex, schematically-unfamiliar texts and language. In the face of such challenges many teachers resort to rote learning practices to ensure their learners pass high-stakes exams at grades 10 and 12 (e.g. Bhattacharya Citation2013; Mody Citation2013).

Prior research indicates that multilingual practices are widespread in Indian English language classrooms, although these have not, until very recently, been viewed through a translanguaging lens (Anderson and Lightfoot Citation2021). Rahman’s (Citation2013) and Chimirala’s (Citation2017) quantitative categorisations of different L1 uses both find evidence of teachers using other languages to explain lesson content and concepts, translate lexis and scaffold learning. Durairajan’s (Citation2017) review of 19 prior studies in India reports clear benefits from multilingual practices, including the increased empowerment and self-confidence of learners, increased metalinguistic awareness and vocabulary recall. More recent research that adopts a translanguaging lens includes Anderson and Lightfoot’s (Citation2021) survey indicating that translingual practices are common in English classrooms across the country, and Mukhopadhyay’s (Citation2020) small scale study in primary classrooms documenting the use of translanguaging for classroom management, translation and contrastive analysis. Sathuvalli and Chimirala (Citation2017) provide evidence of secondary learners’ awareness of the affordances of translanguaging during collaborative learning, including to scaffold collaborative thought and to facilitate English text production. Despite support for these multilingual practices in some forward-thinking policy documents in India (e.g. NCERT Citation2006), there is also evidence of negative attitudes towards multilingual pedagogy (Rao Citation2013). Anderson and Lightfoot document what they call ‘guilty translanguaging’ (Citation2021, 1225) and 18% of their respondents reported being told to teach in English only (1229).

With regard to appropriate terminology to describe the multilingual practices documented in Indian English language teaching (ELT), Durairajan (Citation2017, 309) prefers the term ‘more enabled language’ (MEL) to ‘L1’ to describe the alternative to a ‘target language’ such as English, given that most school communities in India typically include learners with a diverse range of first languages. This MEL is typically the main school (or section) medium of instruction, also often used among learners in the wider school environment. This paper proposes an additional term, ‘less enabled language’ (LEL), to refer to the additional language as object of instruction (English in this paper). This is preferred to ‘L2’ or ‘target language’, as the former overlooks learners who have prior multilingual repertoires and the latter misrepresents the most appropriate outcome of multilingual (including FL/SL) education, where the ‘target’ is multi/translingual competence. In this sense, MEL and LEL avoid the ‘two solitudes assumption’ (Cummins Citation2007, 223), striking a balance between the aim of FL/SL instruction and an appropriate outcome for multilingual education. They are contingently used in this paper, deemed consistent with the weak translanguaging perspective adopted, in which named languages are recognised as socially valued, while also being regularly transcended and subverted in practice (García and Lin Citation2017).

A lack of focus on multilingual or translingual practices in expert teacher research

An extensive body of research on teacher expertise offers numerous insights into aspects of expert teacher (ET) practice and cognition, dating back to the 1980s (Berliner Citation2004; Sternberg and Horvath Citation1995). Research designs have typically involved identifying ETs and studying aspects of their practice or cognition to build detailed understandings of these. Such studies have drawn upon varied criteria in their selection of participants, from the nomination of school principals (e.g. Toraskar Citation2015), to receipt of teacher awards (e.g. Yuan and Zhang Citation2019), measures of learner exam achievement or teacher achievement on formal programmes (e.g. Tsui Citation2003). These varied, sometimes haphazard, sampling strategies are discussed critically by Palmer et al. (Citation2005), who recommend a two-stage approach to participant recruitment for ET studies, involving the use of multiple criteria to identify participants reliably.

A notable gap in this extensive literature is a lack of studies on multilingual practices, even among expert language teachers. While Tsui’s (Citation2003) well-known study in Hong Kong documents English-only practices in the classrooms of her ET, these may have been influenced by the English-only national policy in place at the time (255). Other ET studies in FL/SL contexts (e.g. Li and Zou Citation2017; Yuan and Zhang Citation2019) do not focus on classroom practices. The only prior study that sheds some light in this area is Toraskar’s PhD case study (Citation2015) of three expert secondary teachers of English in India, all of whom are reported to consciously simplify their English and make regular use of ‘code-switching’ (288) to translate lexis, explain concepts and text content, while also allowing their learners to use their L1 if they are unable to respond in English. However, as multilingual practices were not the primary focus of Toraskar’s study, she offers no data from lesson extracts in her findings, nor systematic discussion of these practices in relation to recent (including translanguaging) literature, thus offering only limited insights in this area.

This paucity of research into how expert teachers working in FL/SL (or any) contexts make use of multiple languages in their classroom justifies the current study. This justification is further strengthened by the comparative lack of studies on translanguaging in Indian education. As Lightfoot et al. (Citation2021, 18) observe of Indian classrooms, ‘ … there is a need for greater exploration of the specific translingual practices that are employed by the teacher and learners and how these impact on the development of relevant knowledge and language skills’.

Methodology

Research approach and question

This study draws on data from a larger comparative case study investigating the practices and cognition of eight expert teachers of English working in Indian government-funded secondary schools (Anderson Citation2021). It addresses the following open exploratory research question:

How do expert Indian teachers of English and their learners use language in the classroom?

Participant recruitment

Appropriate criteria for recruiting participants for teacher expertise studies were identified based on a reading of available literature (e.g. Bucci Citation2003; Palmer et al. Citation2005; Tsui Citation2005). These potential criteria were then critically evaluated with consideration of the context in question (Indian secondary ELT). Following Palmer et al.’s (Citation2005) recommendations, a multiple criteria approach (considered more robust; p. 21) was adopted, allowing for indicators of expertise such as teacher educator roles, student performance evidence, receipt of teacher awards, professional group membership, higher qualification and evidence of active CPD in addition to two sine qua non prerequisites: experience and basic qualification (Berliner Citation2004; Palmer et al. Citation2005).

Participants were recruited from one of India’s largest EFL networks through a two-stage recruitment process, as recommended by Palmer et al. (Citation2005). In the first stage, to ensure equity of access, an online ‘Expression of Interest’ form was distributed to members of the network through both mailing lists and social media channels. The form provided a list of potential expertise criteria, inviting teachers to self-assess these initially. Sixteen respondents met both inclusion criteria (experience and basic qualification) and at least one indicator of expertise and were invited to video-interview. Of these, 11 responded and underwent video interviews. Two of these could not guarantee full-time classes during the study period, and one dropped out subsequent to interview due to promotion. The remaining eight participants met at least five potential or likely indicators of expertise (some were confirmed during the interviews, others later in situ) and agreed to participate in the study. The individual indicators of expertise that each participant teacher (PT) met are provided in , which also documents aspects of their specific contexts (discussed further below). While there is a bias towards one state in the sample (five PTs were from Maharashtra), a useful balance of both urban and rural contexts, and range of student backgrounds is present within the sample.

Table 1. Participants’ experience, markers of expertise and teaching contexts.

Data collection and analysis

Based on recommendations for comparative case studies (Bartlett and Vavrus Citation2017; Stake Citation2006), data collection tools included video-recorded lesson observations (21–38 per PT), field notes and interviews (8–10 per PT) over periods of 13–25 working days each. Learner collaborative dialogue was recorded during pair and groupwork using audio data recorders when opportunity allowed (care was taken to collect data only when learners were willing). Interviews invited teachers to reflect both on their decisions and reflections regarding specific lessons, as well as their personal theories regarding learning and teaching. In all contexts, relevant permissions were obtained from local authorities. Informed consent of PTs, learners, parents and headteachers was also obtained, in line with ethical approval provided by the University of Warwick.

Individual case analysis involved transcription, translation (when required) and inductive coding of lessons, interviews and field notes. This process began with initial ‘jottings’ (Miles, Huberman, and Saldana Citation2014, 93) during data collection and moved gradually ‘towards more abstract categories’ (Atkinson and Hammersley Citation2007, 153) during the process. Thematic coding of the wider dataset involved several iterations, from initial topic codes (e.g. building schemata) to more detailed descriptive ones (e.g. drawing on learners’ lives and experiences). Detailed case descriptions were written for each PT to facilitate cross-case analysis, which drew on both Bartlett and Vavrus’s (Citation2017) horizontal comparison and Stake’s (Citation2006) recommendations for the use of case summaries and case comparison matrices.

For this study, analysis of video, audio and transcribed lesson data facilitated ‘progressive focusing’ (Miles and Huberman Citation1994, 261) on the languaging practices of both teachers and learners. Qualitative analysis included drawing upon data that had been thematically coded within the wider dataset for specific pedagogic functions (examples include scaffolding learning, error correction, language play), which were then analysed in terms of their linguistic content (e.g. translating text, explaining lexis, translingual discussion) to shed light onto how these functions were achieved. Quantitative analysis included assessment of overall proportions of different languages used by each PT (see ) and frequency assessments of specific pedagogic practices to enable links between language choice and activities to be drawn. This enabled comparison of participants’ and their learners’ specific languaging practices to identify both similarities and differences, illustrated below through representative lesson extracts. While PT audio data was complete for each lesson (captured through a clip-on microphone), learner data collection was more opportunistic, taking place most often during longer pair and groupwork activities, thus no attempt was made to assess overall MEL/LEL balance of language use or frequency of functions for learners.

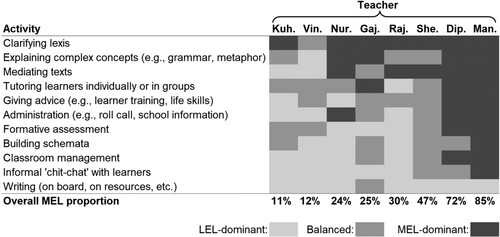

Table 2. Comparison of Teachers’ overall balance of languages used.

To ensure sufficient rigour and transparency during data collection and analysis, both Maxwell’s (Citation2012) and Tracy’s (Citation2010) recommendations were followed. This included the collection of rich data (detailed field notes and photographs alongside audio and video recordings), the provision of thick descriptions (detailed case descriptions were over 14,000 words for each participant), long-term involvement (averaging 3–4 weeks in each location), searches for discrepant evidence during data analysis, and two stages of participant validation (see Anderson Citation2021).

Findings

Contextual observations

In all contexts the MEL (see ) was the official medium of instruction for some or all subjects in the school section in which the teacher taught, and in all cases it was also their choice of alternative language to the LEL (English), with only occasional exceptions, such as in private conversations with individuals. Some learners also opted to draw upon other languages during pair and groupwork (e.g. Marathi in Manjusha’s classes). Consistent with their experience and qualifications (see ), all PTs were found to be expert users (Rampton Citation1990) of both the MEL and the LEL of their learners.

All PTs, except Kuheli and Nurjahan, had a majority of officially disadvantaged learners (up to 99%; see ). For all but one PT, the English curriculum was observed to be overambitious for the majority of learners, some of whom were still challenged by basic literacy in English. The exception to this was Kuheli, the majority of whose learners were from middle-class backgrounds in central and suburban Kolkata, and had, on balance, more access to English outside the classroom and extra-curricular support in their studies. In all contexts, end of year exams assessed English solely as a written language, including reading comprehension, literature studies and writing tasks alongside exercises that checked explicit knowledge of aspects of grammar, lexis and basic literacy.

Teachers’ language use practices

All eight PTs made use of both languages (MEL and LEL) in their lessons; occasionally in isolation, but more often integrated through translanguaging, which was observed in all lessons. However, there was noticeable variation concerning exactly how they balanced their use of resources from the two languages (see and ). For five, their languaging was usually LEL-dominant, with English more often offering the majority of resources used. For two, this was reversed; their languaging was typically MEL-dominant, with English resources integrated into the MEL. One PT (Shekhar) used the two languages fairly evenly. Within each PT’s languaging, this balance varied depending on both activity type and interaction modality (e.g. whole class teaching or tutoring). provides a quantitative summary of each PT’s overall balance between the two languages, and provides a matrix depiction of how activity type influenced this language blend, revealing several broad tendencies, but much variation within these.

LEL-dominant languaging among PTs

Most PTs provided regular exposure to spoken English through their own classroom languaging, what Raju called ‘creating an English atmosphere’. This was observed during both classroom management (e.g. giving instructions for activities, which Vinay and Kuheli sometimes did wholly in English) and informal communication (chit-chat), often at the start of lessons. Topics for chit-chat included the weather, weekend activities and pastoral concerns. In Extract 1, as Raju is conducting the roll call, he draws upon a specific affordance (the absence of a regular attender) to negotiate meaning translingually and enjoy a joke with the learners:

LEL-dominant languaging was also used by most PTs to provide simple spoken feedback to learners (e.g. time reminders, praise; see Extract 2), and by one (Gajanan) to convey text content through simple stories. Three made regular use of the LEL to build schemata (e.g. eliciting prior knowledge on a topic) and to conduct formative assessment of learning (e.g. checking understanding through questioning strategies), although other teachers made more use of the MEL at such times.

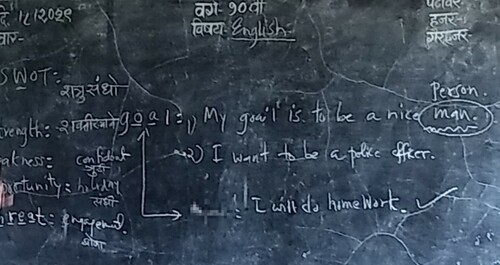

It was notable that the only activity type for which English was usually used monolingually was the more ‘normative’ (Canagarajah Citation2013, 108) practice of writing, both on the chalkboard and on resources, reflecting language use both in exams and official materials (e.g. textbooks), which were typically English only. Although, even here, one PT (Gajanan), whose learners had among the lowest levels of LEL-literacy observed, sometimes included MEL annotations to his boardwork (see ); others did so only occasionally.

Uses of MEL-dominant languaging among PTs

The most common use of MEL-dominant languaging among PTs was to clarify difficult English lexis. This included the pre-teaching of specific items before reading tasks and offering translations in response to learner questions. In Extract 3, Nurjahan is clarifying two related meanings of ‘spring’ in English, which leads to a humorous moment caused by two similarly sounding words in Marathi (jhara [spring] and jhaara [spatula]):

The MEL was also dominant when teachers were providing explanation of complex concepts, such as literary devices (e.g. rhyme schemes, simile, alliteration), or aspects of grammar (e.g. verb tense or article choice). In Extract 4, Dipika is checking learners’ understanding of an exam letter writing task, using mainly Hindi, although both she and her learners integrate LEL resources as subject-specific metalanguage (letter, formal, informal) and example terminology (request, kindly):

Almost as common was a type of cross-linguistic mediation (Council of Europe Citation2018), in which PTs helped learners gain a basic understanding of core curriculum texts that were often too complex (lexically and/or schematically) for learners to read and understand independently in English. Extract 5 comes from a lesson in which Shekhar mediated a text entitled ‘Be SMART’. He initially boarded and pre-taught key English lexical items through contextualised explanation. As the lesson progressed, he integrated these items (e.g. ‘goal’, ‘specific’, ‘area’, ‘improvement’) into MEL-dominant co-text to facilitate understanding and recall while reviewing the five features of the SMART acronym:

Also common was the use of MEL-dominant languaging to provide individual support to learners while monitoring learner-independent work, although this was often found to be differentiated, with PTs using more or less English depending on learner proficiency. In Extract 6, Nurjahan is monitoring pairwork during a reading comprehension exercise; Gautam is less English-proficient, and Aish more English-proficient:

Learners’ languaging practices

All eight PTs shared a belief in the importance of involving learners’ languages in classroom discourse for a number of reasons, including the need to develop learner understanding of complex content, to build confidence, to increase engagement and to reduce learners’ ‘fear’ of English. Even Vinay and Kuheli, who sometimes exerted light pressure on their learners to make more use of English during groupwork interaction, voiced this opinion, as Kuheli reflected on one occasion after a groupwork lesson:

… I was observing what they were doing in the group. And when I saw that, yes, groups were talking about points that really matter I would go close to that group and asked them, ‘OK, now, yes, your thinking is right, and think how you will say that to me in English’.

The student goes on to recall the story well and in detail, also including a small number of LEL resources in her MEL-dominant languaging (e.g. ‘officer ca club’ [officer’s club]), demonstrating her understanding of the story and boosting her confidence in the process. These inclusive attitudes sometimes contrasted with PTs’ colleagues, several of whom were observed to maintain an English-only rule in their classrooms, reprimanding learners for using the MEL: ‘Who is talking? Speak English in class’ (field notes).

Notably, the languaging practices of the learners typically mirrored those of their teachers. In contexts where the teacher’s languaging was LEL-dominant (e.g. Kuheli, Vinay, Gajanan), learners also used more English, particularly during presentations and whole-class interaction with the teacher (see Extract 2). In classes where the teacher made more use of the MEL, learners were more likely to address her in MEL-dominant languaging, as S2 does in Extract 8, when protesting to the teacher that another group had copied their idea to write a cake recipe during a groupwork task:

Collaborative dialogue among learners (e.g. during pairwork and groupwork) was usually MEL-dominant but meaning focused across all contexts, with varying amounts of LEL resources integrated communicatively into discussions. In Extract 9, two of Vinay’s less proficient Grade 7 learners integrate several English lexical units (e.g. place, back, food, there was bread) meaningfully into their discussion of the answer to a text comprehension question that they are working on, gradually building their LEL competence within a MEL framework. As in Extract 8, nouns constitute the majority of LEL lexemes that they make use of:

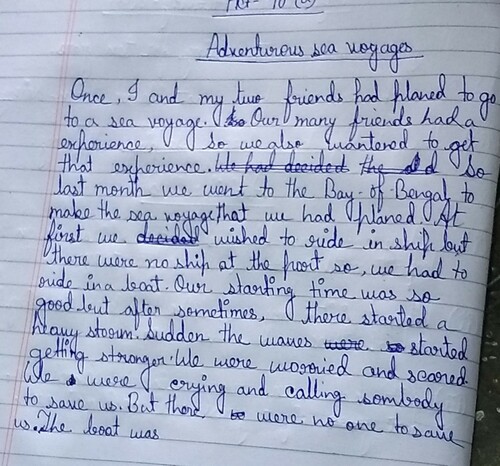

In Extract 10, two of Kuheli’s more LEL-proficient learners are composing a story together. It offers evidence of collaborative thought, predominantly in the LEL, as they scaffold each other’s ideas and share linguistic resources. At this higher level of LEL proficiency compared to the previous two extracts, these learners seem to be integrating a wider range of LEL resources (e.g. longer verb and noun phrases) into their discussion:

shows the composition of S1 from Extract 10, revealing several interesting features of these two learners’ developing linguistic proficiency: their ability to write in English only to meet the monolingual writing requirements of their curricular context; their ability to write slightly different texts (in line with their intention), with both making use of many of the linguistic elements they discussed; and an emerging LEL competence that, despite rarely manifesting itself monolingually in their spoken interactions, is nonetheless developing well, beyond the ability of a typical Grade 8 learner in India. This includes, for example, the effective narrative use of two past tense verb forms and adverbial discourse markers, and an impressive range of low-frequency lexical elements, appropriate to the nautical theme (port, waves, heavy storm) and drama (worried and scared, getting stronger, crying and calling) of their story.

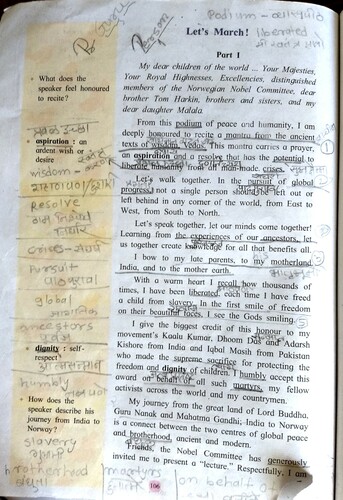

Learners’ more formal written work (e.g. compositions, exercises, exam practice activities), usually involved only English, as shows, consistent with the monolingual expectations of their curriculum. However, informal written work, particularly personal notes or annotations in textbooks, also included the MEL, most often to record translations of lexical items they were learning (see ).

Discussion

The findings presented here document the languaging practices of eight expert Indian teachers of English and their learners. As predicted by prior research in India (e.g. Durairajan Citation2017; Toraskar Citation2015), all are, to varying degrees, translingual practitioners, making regular, flexible, integrated use of English and their learners’ more enabled language in the classroom. Certain specific observations, for example, that the MEL became more dominant during more cognitively challenging lesson activities, are both logical and consistent with prior research (e.g. Chimirala Citation2017; Rahman Citation2013). Less evident in research in Indian contexts, the findings reveal that the expert teachers in this study are also ‘L1-inclusive’ teachers – in all cases permitting, and often actively encouraging their learners to contribute in any language, thereby boosting their confidence in their own abilities, something that these expert teachers did regularly and through multiple means. Importantly, all reject the ‘English-only’ mantra of earlier approaches (see Rao Citation2013) and some of their colleagues.

The findings also reveal a wide variation in PTs’ use of resources from the two languages, from LEL-dominant to MEL-dominant approaches to language teaching. This variation supports prior findings that there is no optimum quantity of ‘L1 use’, even among expert teachers in the same national contexts, and that what constitutes an appropriate balance seems to be heavily dependent on a complex combination of local context, personal beliefs and intended outcomes (Shin, Dixon, and Choi Citation2020). Two example vignettes may illustrate this point:

Vinay, as a highly-respected teacher educator at state level, was given comparatively free reign in his small rural school to engage in the process-oriented approach to teaching that he believed strongly in, enabling him to develop learners’ LEL proficiency directly, both through his own LEL-dominant interaction with them and through the extra-curricular project-work activities he gave them. His practices often differed greatly from his more traditionally-minded colleagues, and were strongly influenced by the international and teacher research communities he participated in.

In contrast to this, Dipika worked in one of several institutions managed by an educational society with a good reputation for exam success in an otherwise disadvantaged environment on the edge of a very large urban slum. It achieved this success through top-down control of curriculum and pedagogy; official materials were replaced with bilingual exam-focused workbooks, and all teachers were expected to teach English through the MEL, conduct regular progress tests and meet bi-monthly syllabus completion points. Despite having somewhat different personal beliefs about language learning herself, Dipika recognised and prioritised these exam-oriented goals for the sake of her learners’ future and her own job security.

Given the multiple differences, particularly in context of work, between Dipika and Vinay, the wide differences in how and when they translanguaged should not be surprising. Yet, the fact that both achieved near universal exam pass rates (96% and 100% respectively during the three years prior to data collection) offers clear evidence that both LEL-dominant and MEL-dominant approaches can be effective, and that within the complex educational ecosystem found in India, there can be no one best method when there is such a diversity of starting points and goals.

Translingual socialisation in the classroom

While, in written form, English is often used monolingually in India, in spoken interaction it is rarely used in isolation from other languages. Its translingual appropriation in varying amounts into everyday discourse is widespread and authentic social practice (Agnihotri Citation2014; Sailaja Citation2011). As such, the diglossic combination of spoken translanguaging and mainly monolingual writing of most PTs can be seen as equally authentic and reflective of wider social behaviour. Consistent with Anderson’s vision of ‘translingual teachers’ (Citation2018, 34), the PTs both modelled such practices and encouraged similar behaviour among their learners, who largely mirrored their teachers’ languaging conventions. In this sense their classrooms constituted ‘site[s] for translingual socialization’ (Canagarajah Citation2013, 184), preparing learners for the integrated spoken use of English within other languages in the wider community, while still enabling them to ‘monolanguage’ (Anderson Citation2018) in English when required – primarily in their use of written English for examinations. Similarities can also be found to Zheng’s (Citation2017) vision of the translingual teacher, who ‘has the potential to draw on his/her translingual identities to adopt a translingual pedagogy, but may not necessarily do so’ (32). Choices of when, how, why and how much to translanguage seem to be influenced by multiple factors, including institutional (e.g. Dipika’s school policies), personal (Vinay’s beliefs) and social (norms in wider society), although in many of the instances described above, the choice seems to have been primarily a pragmatic one, with teachers attempting to balance between strengthening learners’ LEL resources and ensuring understanding through use of the MEL, a common dilemma for many foreign and second language teachers (see Rabbidge Citation2019).

When viewed through a translanguaging lens, several of the practices documented in this study are of potential interest and worthy of further research in India, including cross-linguistic mediation (Extract 5), translingual negotiation for meaning (Extract 1), and evidence of MEL-dominant discourse scaffolding a gradual, meaningful emergence and strengthening of LEL resources (Extracts 9 and 10). It may be that certain strategies within such practices are either more or less facilitative of appropriate learning. Unfortunately, as translingual practices are often frowned upon in language teaching communities in India (Anderson and Lightfoot Citation2021; Rao Citation2013), to date there is little discussion of them, even in national policy documents that recognise multilingual competence as the intended outcome of language education (e.g. Government of India Citation2020). While an earlier, forward-thinking position paper offers more useful guidance, it refers to the need for ‘linguistic purism [to] yield to a tolerance of code-switching and code-mixing if necessary’ (NCERT Citation2006, 12, italics added), unwittingly framing as compromise something that is a natural and authentic practice in wider Indian society.

Considering the findings of this study and others before it (e.g. Durairajan Citation2017), it can be argued that India’s heritage of translingual practice deserves to be encouraged and celebrated – rather than simply tolerated – both in wider society (as is starting to happen in popular art and advertising; Sailaja Citation2011) and in the classroom. This may require an overhaul of current, essentially colonial, monolingual norms, and a move towards more multilingual approaches to both learning and assessment. The ‘Languages for Learning Framework’ proposed by Mahapatra and Anderson (Citation2022) offers one vision for how this may be achieved in India; others may be more appropriate for other contexts.

Conclusion

I have endeavoured to situate this study of translanguaging in its national (Indian) and pedagogic (secondary ELT) contexts, where it happens not so much as a political act of self-determination (Flores Citation2014), but a socio-pragmatic one, albeit subversive to the monolingual norms of national curricula. While I present this as the first detailed study of multilingual practices in the classrooms of any teachers identified as experts, readers should recognise these contextual factors, especially given how much variation was observed, even within the cohort. Several limitations must also be acknowledged:

While large for a comparative case study, a sample size of eight offers, at best, opportunities for only tentative generalisations to be made.

The fact that data was collected and analysed by one researcher only may have allowed subjectivity to impact on reliability.

Despite the long acclimatisation periods involved, the possibility that reactivity (the Observer effect) has influenced the findings cannot be discounted; both teachers and learners may have changed their practices either consciously or unconsciously.

Due to the challenges of data collection, it was not possible to analyse the overall balance of MEL/LEL resources in learner language use; this remains a task for future studies.

Nonetheless, the findings of this study are likely to be of interest, not only to policy makers, curriculum designers and teacher educators in India, but also to practitioners working in complex multilingual environments, particularly across the Global South, where similar constraints and challenges to those experienced by the participant teachers in this study are often found. Any recommendations emerging from a single study with only a small sample must be made tentatively at best. However, given that all eight participants, as expert practitioners, exhibited several important similarities that had evolved independently of each other in diverse contexts, two recommendations can be offered with regard to language-use practices in language teaching:

In contexts where school learners and teachers share prior, more-enabled languages – as is often (but not always) found in India – monolingual (e.g. ‘English-only’) policies for language teaching should be eschewed as outdated and counterproductive.

Wherever possible, teachers should be encouraged to prioritise learner inclusion in classroom discourse and activities over maximal target language use, at least in early stages of primary and secondary foreign language education, both to increase the participation, and to boost the confidence, of those that might otherwise be alienated from their studies.

A final, methodological recommendation is that studies such as this one, which seek to document and disseminate the situated practices of indigenous expert teachers in any realm of education, may be more useful in helping to build context-specific models of appropriate good practice than attempts to ‘import’ approaches from other contexts. This is of particular importance in the low-income, low-resource environments often found across the Global South, where conditions and challenges may differ radically from those of the invariably privileged, high-income contexts from which exogenous approaches are often imported; teacher expertise can be found in any context, it just has to be valued.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the eight participant teachers in this study, their headteachers, colleagues and students for allowing me into their classrooms and lives. Thanks also to the AINET teacher association of India for access to its members, and to Richard Smith and Santosh Mahapatra for feedback on earlier drafts of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agnihotri, R. K. 2014. “Multilinguality, Education and Harmony.” International Journal of Multilingualism 11 (3): 364–379. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2014.921181.

- Anderson, J. 2018. “Reimagining English Language Learners from a Translingual Perspective.” ELT Journal 72 (1): 26–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccx029.

- Anderson, J. 2021. “Eight Expert Indian Teachers of English: A Participatory Comparative Case Study of Teacher Expertise in the Global South.” Doctoral diss., University of Warwick Publications Service and WRAP. http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/159940/.

- Anderson, J., and A. Lightfoot. 2019. The School Education System in India: An Overview. British Council. https://issuu.com/britishcouncilindia/docs/school_education_system_in_india_re.

- Anderson, J., and A. Lightfoot. 2021. “Translingual Practices in English Classrooms in India: Current Perceptions and Future Possibilities.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 24 (8): 1210–1231. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1548558.

- Annamalai, E. 2005. “Nation-Building in a Globalised World: Language Choice and Education in India.” In Decolonisation, Globalisation: Language-in-Education Policy and Practice, edited by A. Lin and P. W. Martin, 20–36. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Atkinson, P., and M. Hammersley. 2007. Ethnography: Principles in Practice. 3rd ed. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Bartlett, L., and F. Vavrus. 2017. Rethinking Case Study Research: A Comparative Approach. New York: Routledge.

- Berliner, D. C. 2004. “Describing the Behavior and Documenting the Accomplishments of Expert Teachers.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 24 (3): 200–212. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467604265535.

- Bhattacharya, U. 2013. “Mediating Inequalities: Exploring English-Medium Instruction in a Suburban Indian Village School.” Current Issues in Language Planning 14 (1): 164–184. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2013.791236.

- Bucci, T. 2003. “Researching Expert Teachers: Who Should We Study?” The Educational Forum 68 (1): 82–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00131720308984606.

- Canagarajah, S. 2011. “Codemeshing in Academic Writing: Identifying Teachable Strategies of Translanguaging.” The Modern Language Journal 95 (3): 401–417. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01207.x.

- Canagarajah, A. S. 2013. Translingual Practice. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Canagarajah, S. 2018. “Translingual Practice as Spatial Repertoires: Expanding the Paradigm Beyond Structuralist Orientations.” Applied Linguistics 39 (1): 31–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx041.

- CBSE (Central Board of Secondary Education). 2020. English Language and Literature (Code no. 184; 2020-21).

- Central Square Foundation. 2020a. School Education in India: Data, Trends and Policies. https://www.centralsquarefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/School-Education-in-India-Data-Trends-and-Policies.pdf.

- Central Square Foundation. 2020b. State of the Sector Report: Private Schools in India. https://centralsquarefoundation.org/State-of-the-Sector-Report-on-Private-Schools-in-India.pdf.

- Chimirala, U. M. 2017. “Teachers’ ‘Other’ Language Preferences: A Study of the Monolingual Mindset in the Classroom.” In Multilingualisms and Development: Selected Proceedings of the 11th Language and Development Conference, New Delhi, India, 2015, edited by H. Coleman, 151–168. London, UK: British Council.

- Council of Europe. 2018. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Companion Volume with New Descriptors. Strasbourg, France: Education Policy Division, Council of Europe.

- Creese, A., and A. Blackledge. 2010. “Translanguaging in the Bilingual Classroom: A Pedagogy for Learning and Teaching?” The Modern Language Journal 94 (1): 103–115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00986.x.

- Cummins, J. 2007. “Rethinking Monolingual Instructional Strategies in Multilingual Classrooms.” The Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics 10 (2): 221–240.

- Durairajan, G. 2017. “Using the First Language as a Resource in English Classrooms: What Research from India Tells Us.” In Multilingualisms and Development: Selected Proceedings of the 11th Language and Development Conference, New Delhi, India, 2015, edited by H. Coleman, 307–316. London, UK: British Council.

- Eberhard, D. M., G. F. Simons, and C. D. Fennig, eds. 2021. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. 24th ed. [Online version]. SIL International. http://www.ethnologue.com.

- Flores, N. 2014. Let’s Not Forget That Translanguaging is a Political Act. The Educational Linguist, July 19. https://educationallinguist.wordpress.com/2014/07/19/lets-not-forget-that-translanguaging-is-a-political-act/.

- García, O. 2009. “Education, Multilingualism and Translanguaging in the 21st Century.” In Social Justice Through Multilingual Education, edited by T. Skutnabb-Kangas, R. Phillipson, A. K. Mohanty, and M. Panda, 140–158. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- García, O., and W. Li. 2014. Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- García, O., and A. M. Y. Lin. 2017. “Translanguaging in Bilingual Education.” In Bilingual and Multilingual Education, edited by O. García, A. M. Y. Lin, and S. May. Springer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02258-1_9.

- Government of India. 2020. National Education Policy 2020. Ministry of Human Resource Development. https://www.education.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/NEP_Final_English_0.pdf.

- Heugh, K. 2015. “Epistemologies in multilingual education: translanguaging and genre – companions in conversation with policy and practice.” Language and Education 29 (3): 280–285. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2014.994529.

- Heugh, K. 2021. “Southern Multilingualisms, Translanguaging and Transknowledging in Inclusive and Sustainable Education.” In Language and the Sustainable Development Goals, edited by P. Harding-Esch and H. Coleman, 37–47. London, UK: British Council.

- Kachru, B. B. 1978. “Toward Structuring Code-Mixing: An Indian Perspective.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 16: 27–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl.1978.16.27.

- Leung, C., and G. Valdés. 2019. “Translanguaging and the Transdisciplinary Framework for Language Teaching and Learning in a Multilingual World.” The Modern Language Journal 103 (2): 348–370. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12568.

- Li, W. 2011. “Moment Analysis and Translanguaging Space: Discursive Construction of Identities by Multilingual Chinese Youth in Britain.” Journal of Pragmatics 43: 1222–1235. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.07.035.

- Li, W. 2018. “Translanguaging as a Practical Theory of Language.” Applied Linguistics 39 (1): 9–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx039.

- Li, W., and W. Zou. 2017. “A Study of EFL Teacher Expertise in Lesson Planning.” Teaching and Teacher Education 66: 231–241. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.04.009.

- Lightfoot, A., A. Balasubramanian, I. Tsimpli, L. Mukhopadhyay, and J. Treffers-Daller. 2021. “Measuring the Multilingual Reality: Lessons from Classrooms in Delhi and Hyderabad.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. Advance Online Publication. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2021.1899123.

- Mahapatra, S. K., and J. Anderson. 2022. “Languages for Learning: A Framework for Implementing India’s Multilingual Language-in-Education Policy.” Current Issues in Language Planning. Advance online publication. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2022.2037292.

- Makalela, L. 2015. “Moving out of Linguistic Boxes: The Effects of Translanguaging Strategies for Multilingual Classrooms.” Language and Education 29 (3): 200–217. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2014.994524.

- Matras, Y. 2009. Language Contact. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Maxwell, J. A. 2012. A Realist Approach for Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Miles, M. B., and A. M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Miles, M. B., A. M. Huberman, and J. Saldana. 2014. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Mody, R. 2013. Needs Analysis Report: Maharashtra English Language Initiative for Secondary Schools (ELISS). British Council. https://issuu.com/britishcouncilindia/docs/needs_analysis_report_-_eliss_2013.

- Mukherjee, K. 2018. “An English Teacher’s Perspective on Curriculum Change in West Bengal.” In International Perspectives on Teachers Living with Curriculum Change, edited by M. Wedell and L. Grassick, 125–145. Springer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-54309-7_7.

- Mukhopadhyay, L. 2020. “Translanguaging in Primary Level ESL Classroom in India: An Exploratory Study.” International Journal of English Language Teaching 7 (2): 1–15.

- NCERT. 2006. Position Paper: National Focus Group on Teaching of English. New Delhi, India: National Council of Educational Research and Training.

- Palmer, D. J., L. M. Stough, T. K. Burdenski, Jr. and M. Gonzales. 2005. “Identifying Teacher Expertise: An Examination of Researchers’ Decision Making.” Educational Psychologist 40 (1): 13–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4001_2.

- Probyn, M. 2009. “‘Smuggling the vernacular into the classroom’: conflicts and tensions in classroom codeswitching in township/rural schools in South Africa.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 12 (2): 123–136. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.1080/13670050802153137.

- Probyn, M. 2019. “Pedagogical Translanguaging and the Construction of Science Knowledge in a Multilingual South African Classroom: Challenging Monoglossic/Post-Colonial Orthodoxies.” Classroom Discourse 10: 216–236. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2019.1628792.

- Rabbidge, M. 2019. Translanguaging in EFL Contexts: A Call for Change. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Rahman, A. 2013. “Role of L1 (Assamese) in the Acquisition of English as L2: A Case of Secondary School Students of Assam.” In English Language Teacher Education in a Diverse Environment, edited by P. Powell-Davies and P. Gunashekar, 215–222. London, UK: British Council.

- Rampton, M. B. H. 1990. “Displacing the ‘Native Speaker’: Expertise, Affiliation, and Inheritance.” ELT Journal 44 (2): 97–101.

- Rao, A. G. 2013. “The English-Only Myth: Multilingual Education in India.” Language Problems and Language Planning 37 (3): 271–279. doi:https://doi.org/10.1075/lplp.37.3.04rao.

- Sailaja, P. 2011. “English: Code-Switching in Indian English.” ELT Journal 65 (4): 473–480. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccr047.

- Sathuvalli, M., and U. M. Chimirala. 2017. “Living the Translanguaging Space: An Emic Perspective.” In Multilingual Education in India: The Case for English, edited by M. Mishra and A. Mahanand, 85–105. New Delhi, India: Viva Books.

- Shin, J., L. Q. Dixon, and Y. Choi. 2020. “An Updated Review on Use of L1 in Foreign Language Classrooms.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 41 (5): 406–419. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2019.1684928.

- Stake, R. E. 2006. Multiple Case Study Analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Sternberg, R. J., and J. A. Horvath. 1995. “A Prototype View of Expert Teaching.” Educational Researcher 24 (6): 9–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X024006009.

- Toraskar, H. B. 2015. “A Sociocultural Analysis of English Language Teaching Expertise in Pune, India.” Doctoral diss., University of Hong Kong. The HKU Scholars Hub. http://hub.hku.hk/handle/10722/221032.

- Tracy, S. J. 2010. “Qualitative Quality: Eight “Big-Tent” Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 16 (10): 837–851. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410383121.

- Tsui, A. B. M. 2003. Understanding Expertise in Teaching: Case Studies of ESL Teachers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Tsui, A. B. M. 2005. “Expertise in Teaching: Perspectives and Issues.” In Expertise in Second Language Learning and Teaching, edited by K. Johnson, 167–189. Palgrave Macmillan. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230523470_9.

- Yuan, R., and L. J. Zhang. 2019. “Teacher Metacognitions About Identities: Case Studies of Four Expert Language Teachers in China.” TESOL Quarterly 54 (4): 870–899. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.561.

- Zheng, X. 2017. “Translingual Identity as Pedagogy: International Teaching Assistants of English in College Composition Classrooms.” The Modern Language Journal 101 (S1): 29–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12373.

Appendix

Transcription conventions

Lesson extracts are formatted in two columns, with original utterance on left (using Romanized text) and English only equivalent on right. Lexicogrammatical units from languages other than English are italicised. Extracts use as few data transcription conventions as possible to prioritise inclusivity for non-specialist readers. Accompanying actions and paralinguistic/non-verbal features are indicated in round brackets. Symbols used: