ABSTRACT

Metacognitive knowledge is essential to vocabulary knowledge development and possibly morphological awareness, but related research comparing nonminority Han and minority Yao students is scant. We conducted a longitudinal study in China to fill this gap. Specifically, we compared 112 Yao students’ and 101 Han students’ growth trajectories in metacognitive knowledge and morphological awareness from Grade 3 to Grade 6 during their primary school education. Findings supported the covarying development of metacognitive knowledge and morphological awareness in both groups. Findings exhibited a cumulative trend from the third to the sixth grade. However, Yao students significantly lagged behind Han students in terms of both factors. Results further showed the effect of metacognitive knowledge on morphological awareness. Findings also highlighted the extent to which Yao students diverged from Han students in their metacognitive knowledge development and morphological awareness. We conclude our paper by highlighting instructional needs for enhancing minority Yao students’ metacognitive knowledge and morphological awareness in multilingual development.

Introduction

China is a multiethnic state collectively founded by 56 ethnic groups, of which 55 are ethnic minorities and one, Han, is the ethnic majority. Minority students mostly use their home language and live in remote or impoverished regions (Feng and Adamson Citation2018). Multilingual learning (e.g. learning the local language, Mandarin, and then English) is thus a challenge for minority students in China. Advanced English proficiency is a key pedagogical objective in teaching English as a foreign language (EFL) to ethnic minority and nonethnic minority students. Among EFL skills, vocabulary has been identified as one of the most crucial dimensions of language proficiency: EFL learners must understand approximately 98% of words in a text to adequately comprehend the content (Hu and Nation Citation2000). Given the importance of lexical size in language learning, it is natural to seek to understand EFL ethnic minority or nonethnic minority students’ vocabulary development—particularly morphology, a factor that predicts young learners’ literacy development (McCutchen, Green, and Abbott Citation2008).

Consistent with the reform and opening up of China, the country’s foreign language education policy is to improve minority students’ English language proficiency. However, it is challenging for Chinese minority students to develop such proficiency; linguistic minority students have fewer opportunities than nonminority students to access sufficient language learning resources (Feng and Adamson Citation2018). For example, the Yao, a relatively small minority group living within a minority region, communicate in their own language. Mandarin Chinese is not acquired until a later age, and English is not studied until even later. Despite extensive research on multilingual development, little international scholarly attention has been given to Chinese Yao ethnic minority students’ development of morphological awareness.

It is important to explore the development of morphological awareness. This awareness—the ability to manipulate morphemes and reflect on the process of word formation (Kuo and Anderson Citation2006)—is vital in expanding vocabulary size (Jiang and Kuo Citation2019). Morphemes are the smallest linguistic units that convey semantic information. For example, the word reliable is composed of two morphemes: the base word rely, which denotes depend on, trust, and confidence; and the suffix able, which marks the word as an adjective and means capable of. Morphological awareness plays a major role in English vocabulary expansion. According to Perfetti and Stafura (Citation2014), skilled learners’ mental lexicon is morphologically organized; thus, morphological knowledge facilitates learners’ ability to understand, store, and retrieve words containing multiple morphemes.

The relationship between metacognitive knowledge and vocabulary knowledge has received much academic attention (Teng Citation2021). Findings point to the role of metacognitive knowledge in developing vocabulary knowledge. Recent studies have explored young learners’ longitudinal development of metacognitive knowledge and vocabulary knowledge (Lepola et al. Citation2020; Teng Citation2021); however, longitudinal work comparing minority and nonminority students is sparse. Despite evidence that young learners’ metacognitive knowledge improves with age and learning experience (Annevirta and Vauras Citation2001; Teng and Zhang, L. J. Citation2021), these learners’ longitudinal development of morphological awareness remains unclear. Awareness of morphology plays an important role in vocabulary expansion for minority students (Kieffer and Lesaux Citation2012). Ethnic minority students’ development of metacognitive knowledge and morphological awareness in learning English as a third language therefore merits consideration. English is nonminority learners’ second language. Sequential differences may determine variations in developing English morphology.

This study explores the longitudinal development of metacognitive knowledge and morphological awareness in a sample of ethnic minority (Yao) and nonethnic minority (Han) students. Yao minority students were chosen as our focal population for several reasons. First, schools in the Yao ethnic area have an educational environment rich in ethnic characteristics and provide a variety of activities for learning the ethnic language. Second, these schools are trying to implement a multilingual learning program in as early as Grade 3 in primary school. Our period of investigation spanned from Grades 3–6. Results are intended to shed light on the possible mutual relationship between metacognitive knowledge and English morphological awareness in these students. Findings are also expected to enrich understating of the similarities and differences between young ethnic minority and nonethnic minority students’ development of metacognitive knowledge and English morphological awareness.

Literature review

Metacognitive knowledge

Metacognition is a highly researched topic in educational psychology. It has received extensive attention in the EFL context because it is integral to language learning, knowledge transfer, and lifelong learning (Zhang and Zhang Citation2018). Although more than 40 years have passed since the notion’s introduction (Flavell Citation1979), effort is still needed to conceptualize and measure metacognition in relation to learners’ vocabulary acquisition— (Qin and Teng Citation2017; Teng Citation2021; Teng and Zhang, D. Citation2021). The challenges in assessing metacognition are well established. One obstacle concerns the two main functions of metacognition: monitoring and control. The former focuses on individuals’ awareness of their own cognition, and the latter highlights people’s ability to exercise control over their thinking. Metacognition is thus a multifaceted and dynamic concept because it involves beliefs about cognition, skills for controlling cognition, and feelings and judgment in executing a task (Efklides Citation2008). These three facets of metacognition are otherwise known as metacognitive knowledge, metacognitive skills, and metacognitive experiences (Efklides Citation2008). The current study revolves around metacognitive knowledge.

Metacognitive knowledge refers to ‘knowledge or beliefs about what factors or variables act and interact in what ways to affect the course and outcome of cognitive enterprises’ (Flavell Citation1979, 907). The main feature of this form of knowledge is one’s beliefs about learning, processing information, and adopting metacognitive strategies for learning. Metacognitive knowledge helps learners regulate cognitive activities. According to Brown (Citation1987), metacognitive knowledge includes declarative knowledge (i.e. knowledge of what one knows, how to learn, and what factors influence learning), procedural knowledge (i.e. knowledge of a specific skill or task), and conditional knowledge (i.e. knowledge of understanding different strategies for different conditions). Schraw (Citation1994) further described metacognitive knowledge as including persons (i.e. learners’ knowledge of dealing with tasks in different situations), tasks (i.e. knowledge of understanding task features and processing demands), and strategies (i.e. cognitive and metacognitive strategies for executing a task). Metacognitive knowledge is commonly described as a reflection on how individuals express knowledge about persons, tasks, and strategies in learning.

In spite of the difficulties in measuring metacognitive knowledge, a growing body of literature supports its role in helping young students become aware of their learning process (Marulis, Baker, and Whitebread Citation2020), particularly text comprehension (Annevirta et al. Citation2007; Teng and Zhang, L. J. Citation2021). Young learners are believed to develop metacognitive knowledge, which is critical to their ability to process the information required to execute learning tasks. It is further reasonable to assume that their initial level of metacognitive knowledge may determine their development of morphological awareness.

Morphological awareness

Morphological awareness (i.e. a basic ability to parse words and analyze constituent morphemes for meaning construction) is fundamental to learners’ vocabulary development (Zhang Citation2002). The term refers to learners’ abilities to reflect upon and manipulate morphemes and morphological structure (Carlisle Citation2000). It entails different facets and represents a multidimensional type of competence that facilitates reading development (Ku and Anderson Citation2003). In the case of young learners, morphological awareness captures the morphological structure of their language. An understanding of morphological segmentation and manipulation skills is pivotal to language learning.

Anglin (Citation1993) examined the development of morphological awareness in primary school students. Participants included 32 Caucasian learners in Grades 1, 3, and 5. Morphology was evaluated through interviews. Results revealed that first graders knew some derived forms while third graders knew more about the number of derived forms. Scores were much more pronounced for fifth graders. The findings also suggested that differences in students’ socioeconomic status could influence morphological awareness. Zhang, Koda, and Sun (Citation2014) considered a sample of 45 fifth graders and 51 sixth graders in a primary school. Assessment instruments included a nonverbal intelligence test, five morphological awareness tasks, and two reading comprehension tests. Children’s compound awareness significantly predicted L1 and L2 reading comprehension. This finding is unsurprising given that morphological awareness helps learners infer the meanings of unknown and complex words (Anglin Citation1993). However, an understanding of morphology requires familiarity with numerous aspects of knowledge, and it is impossible for learners to understand separate facets with equal strength, detail, and fluency. Individual differences in unlocking meanings of novel, morphologically complex words develop cumulatively and incrementally. Learners may find some morphologically complex words easy to learn while other words seem difficult. This phenomenon implies the need to investigate primary school students’ variation in their development of morphological awareness.

Empirical findings on metacognitive knowledge and morphological awareness

Flavell (Citation1979) proposed a model of cognitive monitoring. This model highlights the actions of and interactions among metacognitive knowledge, metacognitive experiences, goals (or tasks), and actions (or strategies). Young learners might at first distinguish only between understanding and not understanding things. They can then proceed to comprehend input that makes them feel confused, unable to act, or uncertain about what is intended or meant. They next proceed to a clear representation of something and subsequently gain a sense of what to do in a later stage. Strong metacognitive knowledge is a decisive factor in high-achieving students’ performance compared with low achievers (Perry Citation1998; Sato Citation2021). Young learners can become more intentional about learning if they develop strategies or knowledge that serve their goals. Their selection of strategies and storage of information may help these learners as they seek to comprehend and memorize content. Hence, it is essential to foster young learners’ inquisitiveness and metacognitive knowledge development, each of which is oriented around cognitive modeling. It is accordingly necessary to scrutinize how young learners develop metacognitive knowledge over time.

Annevirta and Vauras (Citation2001) evaluated 196 primary school students’ longitudinal development of metacognitive knowledge from preschool to third grade. Findings highlighted the potential of exploring such development but also highlighted challenges: some learners were unable to provide sound explanations when responding to tasks. Young learners displayed unique development levels in terms of memory, learning, and comprehension. Annevirta et al. (Citation2007) also explored primary school students’ longitudinal development of metacognitive knowledge. Latent growth curve (LGC) modeling highlighted learners’ individual differences in this regard. Meanwhile, the metacognitive knowledge development was not cumulative: learners with initially better levels of metacognitive knowledge did not acquire any more knowledge than those with initially lower levels. Marulis et al. (Citation2016) conducted interviews to assess metacognitive knowledge development in 3- to 5-year-old preschool children and identified personal variations; in particular, older children scored higher in metacognitive knowledge than young learners. Two studies of young Chinese learners (Teng Citation2021; Teng and Zhang, L. J. Citation2021) presented further evidence of the cumulative development of metacognitive knowledge—learners who possessed initially higher levels continued to progress in their subsequent years of learning. In particular, Teng (Citation2021) highlighted the importance of metacognitive knowledge on vocabulary knowledge.

Morphological awareness manifests through a multilayered set of cognitive processes. Zhang, Koda, and Leong (Citation2016) explored the longitudinal development of 211 Malay–English bilingual children’s morphological awareness in Singapore. The learners completed a morphological relatedness task and a lexical inference task in both English and Malay. Pairwise t-tests showed that morphological awareness performance at Time 2 (Grade 4) was significantly better than that at Time 1 (Grade 3). Structural equation modeling indicated a good model fit, demonstrating that morphological awareness contributed significantly to lexical inference at Times 1 and 2. Lam et al. (Citation2012) considered the development of morphological awareness and its roles in vocabulary and reading comprehension among young Chinese-speaking English language learners (i.e. 46 kindergarteners and 34 first graders). Over time, on average, older children performed significantly better on the morphological measures than their younger counterparts. Hierarchical linear regression analyses supported the contributions of morphological awareness to vocabulary and reading comprehension. Another longitudinal study (Jiang and Kuo Citation2019) focused on 523 first-year college students. Learners of different proficiency levels made distinct degrees of progress in certain aspects of morphological awareness (e.g. interpreting the meaning of a suffix and identifying the base of a morphologically complex word).

A thorough review of the literature presents no evidence connecting metacognitive knowledge and morphological awareness. A recent effort (Teng Citation2021) addressed the longitudinal development of metacognitive knowledge and vocabulary knowledge. Findings supported the developmental dynamics between both; for instance, young learners’ initial level of metacognitive knowledge predicted their later development of both metacognitive knowledge and vocabulary knowledge. Such implications can be extended to explorations of metacognitive knowledge and morphological awareness. One reason, as Jiang and Kuo (Citation2019) argued, is that morphological awareness relates to vocabulary development. A recent study (Teng and Zhang CitationUnder review) supported the differences between minority and nonminority students’ development of metacognitive knowledge and breadth of vocabulary knowledge. However, not much is known about the longitudinal development of metacognitive knowledge and morphological awareness—especially in minority students, a unique group of multilingual learners. Discrepancies may emerge in minority and nonminority students’ longitudinal development of metacognitive knowledge and morphological awareness. Compared with nonminority students, minority students might have limited vocabulary knowledge due to a dearth of resources and language input (e.g. Shahar-Yames and Prior Citation2018). Their lack of language development may further tie into their development of metacognitive knowledge (van Steensel et al. Citation2016). However, disparities in growth rates between minority and nonminority students are poorly understood, particularly in the Chinese context.

The present study

The present study aimed to evaluate minority Yao and nonminority Han students’ development of metacognitive knowledge and English morphological awareness in China. Following the developmental trajectory of these factors in both student groups enabled us to determine the extent to which metacognitive knowledge can explain the development of English morphology. Findings shed light on instruction regarding metacognitive knowledge and morphology for primary school students. Three questions guided this work:

To what extent do Han and Yao students develop metacognitive knowledge and morphological awareness from Grades 3–6?

Do minority students and nonminority students differ in their metacognitive knowledge and morphological awareness from Grades 3–6?

To what extent is Han and Yao students’ metacognitive knowledge level correlated with the development of morphological awareness?

Method

Participants

Our sample consisted of 213 primary school third-grade students. The mean age was 9.8 (SD = 1.04). One hundred and twelve learners (male: 67; female: 45) belonged to the Yao ethnic minority group, and 101 (male: 52; female: 49) belonged to the nonminority Han group. China’s government classification system considers the Yao people (also known as Mien) an ethnic minority group. In this study, Yao people who were classified as Yao in their household registration booklet and who spoke the Yao language before primary school were defined as the minority group. The Yao people mostly live in the mountains of southern China; approximately 60% live in Guangxi province. Yao students in our sample were from Bama County, a Yao autonomous county in Guangxi. Participants were followed from third to sixth grade and were from two primary schools: one for Han students and another for Yao students. Although we hoped to only focus on one school, we were unable to identify a school with a sufficient number of both Han and Yao students for this study. The Yao school was chosen because this school offered language lessons in Yao, Mandarin, and English beginning in Grade 3. The Han school was chosen because this school was similar with the Yao school in terms of curriculum arrangement and textbook teaching. It is worth noting that the selected schools may not represent all schools, as some Yao schools in remote areas do not offer English lessons in primary school. Participants received the same set of materials for classroom instruction. The language of instruction was Mandarin (the second language for Yao students and the first language for Han students). Formal English instruction starts in third grade, but 80% of Han students and 25% of Yao students reported having received some English training before that. Of the original sample of 230 students, data from 213 students were retained for analysis.

Measures

Study measures included a test of metacognitive knowledge (MCK) and of morphological awareness (MA).

Metacognitive knowledge (MCK)

MCK was assessed through prompt-oriented individual interviews. All interviews were administered after a series of verbally and pictorially presented tasks. The tasks focused on participants’ knowledge of cognitive processes, including their abilities to remember, understand, and learn something. Each cognitive process included eight tasks. The MCK test referred to persons, tasks, and strategies, the pillars of metacognitive knowledge (Schraw Citation1994). Each task included two or three pictures. Each picture depicted a situation in which a little boy or girl was oriented to remember, understand, or learn something. Twenty-four tasks had been adopted in previous studies (Annevirta and Vauras Citation2001; Teng Citation2021; Teng and Zhang, L. J. Citation2021). illustrates a sample picture task measuring one’s knowledge and recalling the details of a story.

M1-Remember the details of a story.

A boy was trying to remember details of a story in a book. What was the best way for the boy to remember the details of a story?

Each participant listened to the test administrator’s verbal description of each situation. Participants then selected the best choice based on their ideas. They next verbally explained why they had chosen a specific picture (e.g. ‘Why in the situation you selected was the boy better able to remember the details of a story?’) (). The test administrator could guide participants in answering the questions by instructing them to imagine what they would do if they were in the given situation. The test administrator also provided concrete prompts to help participants understand how to remember, understand, or learn something. The prompts were as follows: (memory) ‘How would you try to remember information in a story?’; (comprehension) ‘How would you try to understand a story?’; (learning) ‘What can you learn from this story?’ These prompts were intended to encourage participants to reflect on their learning process.

The scoring system was based on a 3-point scale. For example, participants received 0 points for irrelevant or simple explanations (e.g. ‘I think it’s good’ or ‘I just like it’). Participants received 1 point for implicit but relevant answers (e.g. ‘Reading a book is helpful,’ ‘I can find something in the book,’ or ‘I followed the instructions to read the book’). Participants received 2 points for adequate and relevant answers (e.g. ‘Taking notes is helpful’ or ‘I like taking some notes during reading.’) Participants earned 3 points for more explicit explanations (e.g. ‘It is easier to remember more information if taking notes’ or ‘It is a good practice to remember difficult words by taking notes while reading’). The Cronbach’s alpha values for the MCK test ranged from .82 to 88 for each grade, indicating acceptable reliability.

The MCK test instructions were in Chinese. All dialogs were audio-recorded and transcribed. Three independent judges were invited for scoring. First, two raters scored participants’ verbal explanations twice. Interrater reliability reached 84%–92% in the second round of rating. Disagreements were resolved by inviting the third rater. The scores for the explanations of each task were summed, with a possible maximum score of 72 points. Participants’ MCK scores, which were based on their descriptions of cognitive mental processing, reflected Flavell’s (Citation1979) theoretical supposition that metacognitive knowledge conveys learners’ comprehension, learning, and understanding of persons, tasks, and strategies.

Morphological awareness (MA)

Morphological awareness was measured using the Test of Morphological Structure (Carlisle Citation2000). Studies have shown this instrument’s construct validity (e.g. Wagner, Muse, and Tannenbaum Citation2007). The test includes two tasks: decomposition and derivation. Decomposition refers to decomposing derived words in an attempt to finish a sentence; it requires learners to identify and use the morphological base form in a sentence (e.g. driver: ‘It is not good to _____ a car after drinking’ [drive]). Derivation refers to producing a derived word to finish a sentence (e.g. work: ‘My father is a ______’ [worker]). The base and derived forms on both tasks were equivalent in word frequency. The two tasks contained equal numbers of word relations that were transparent (i.e. reason and reasonable) and shifted words (i.e. produce and production). Suffixes familiar to primary school students were used (e.g. -th and -er, as in growth and worker). This test was initially designed to be administered orally, such that test administrators read the word and sentence aloud and learners responded with a written answer. However, most participants in our study found it difficult to complete the test solely by listening. Participants were instead allowed to read each item while the test administrator also read it aloud. The original test included 56 items (28 items per task). We added more items to each task to avoid ceiling effects and to capture the upper range of the ability distribution in a longitudinal study when students entered the fifth and sixth grades. The final test thus included 100 items (50 per task). A learner’s test was stopped if they identified six items incorrectly. A correct answer earned a score of 1, and an incorrect answer earned 0 points. No partial credit was given. The maximum test score was 100 points. Final scores were calculated as the sum of the total number of items answered correctly in both tasks. The Rasch-estimated reliability of the measure at each wave was good (.81 in third grade, .85 in fourth grade, .86 in fifth grade, and .80 in sixth grade). Two raters were responsible for scoring, and interrater agreement was satisfactory (percent agreement = 95%; Cohen’s Kappa = .91).

Data collection

The MCK and MA tests were administered individually in a supportive and flexible classroom. The test administrator explained the procedures to participants. Each test took approximately 30 min to complete. The language of instruction for both tests was Mandarin Chinese. Testing took place at the end of the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth grades. Although many participants reported having had experience learning English before third grade, some may have just started learning English in third grade. Testing was therefore first conducted at the end of third grade.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using LGC modeling based on linear structural equation modeling in the Mplus program. LGC modeling has been deemed useful when evaluating longitudinal development (Geiser Citation2013). Measurements of MCK and MA over time (from Grades 3–6) were divided into several latent components to discern linear or quadratic trends. Goodness-of-fit statistics were calculated to assess whether the data fit the models. Index values included the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), the goodness-of-fit index, and the comparative fit index (CFI). A cutoff value for a good fit was close to 0.06 for RMSEA, .0.09 for SRMR, 0.96 for the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and 0.96 for CFI (Hu and Bentler Citation1999).

Results

The first question explored the extent to which the two groups of Han and Yao students developed metacognitive knowledge and morphological awareness from Grades 3–6. Before employing LGC modeling to explore developmental trends, we computed statistics for the two tests administered in different grades. Descriptive statistics suggested that Han students’ MCK and MA scores exceeded those of Yao students at four test points.

LGC models were used to explore associations between the initial level (i.e. intercept) of MCK and MA and growth over time. Separate analyses based on LGC models were first considered to assess the extent to which MCK and MA correlated with the same variables of MCK and vocabulary knowledge (VK) at the uniconstruct level. Growth in MCK and VK was based on two growth factor components, namely an intercept growth factor (level) and a linear growth rate (slope). shows the fit of the data for a model of linear growth along with the quadratic growth rate for MCK and MA (Han students).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for MCK and MA by grade

Table 2. Comparison of models for MCK and VK (Han students)

The quadratic model performed better than the linear model in terms of MCK, in that MCK increased steadily over time. In the case of MA, the Akaike information criterion and Bayesian information criterion were lower than those of the quadratic model, whereas the CFI and TLI were higher than those of the quadratic model. Data fitness showed that the linear model better suited MA, which exhibited a linear growth trend. The initial level (I = 19.920) was significantly and positively correlated with growth speed (S = 10.658, p < .001), revealing that a better initial MA level led to faster growth of MA at a later age.

We then identified the intercept and slope of each growth mode (). The intercept levels of MCK and MA at each measurement point were positive and statistically significant (p < .001), as were the slope levels of MCK and MA (p < .001). These data substantiated significant individual differences in the growth of MCK and MA.

Table 3. Intercept and slope of each model for Han students

We next explored the growth of MCK and MA in Yao students. presents the data fitness for the linear growth and quadratic growth models; the former was better than the latter for MCK and MA. In other words, Yao students’ initial MCK and MA determined these learners’ growth in both areas at later ages.

Table 4. Comparison of models for MCK and VK (Yao students)

The intercept and slope of each variable growth mode are listed in . The intercept and slope levels of MCK and MA at each measurement point were positive and statistically significant (p < .001), indicating significant individual differences in Yao students’ MCK and MA growth.

Table 5. Intercept and slope of each model for Yao students

The second research question addressed whether Yao and Han students’ metacognitive knowledge and morphological awareness differed by grade. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed that the main effect of ethnic group on MCK was significant (F = 165.565, p < .001, partial η2 = .428); that is, Han students’ MCK scores were significantly higher than those of Yao students. The main effect of time was also significant (F = 3356.249, p < .001, partial η2 = .938)—MCK scores rose over time. The interaction of time*ethnic group was significant as well (F = 353.394, p < .001, partial η2 = .615). Han and Yao students thus exhibited distinct development trends at the four measurement points. Results appear in .

Table 6. ANOVA results for MCK

We performed repeated ANOVA to explore the variance between Han and Yao students. Repeated measures were based on a 2*4 design (2 ethnic groups: Han and Yao; 4 measurements) to compare Han and Yao students’ MCK. The MCK growth trend of Han students was found to be higher than that of Yao students. Furthermore, the Han students achieved better MCK scores than the Yao students at each measurement point (Grade 3: t = 4.683, p < .001; Grade 4: t = 8.328, p < .001; Grade 5: t = 11.603, p < .001; Grade 6: t = 20.575, p < .001).

The ANOVA also returned a significant main effect of ethnic group on MA (F = 243.437, p < .001, partial η2 = .524): Han students’ MCK scores were significantly higher than those of Yao students. The main effect of time was additionally significant (F = 4459.779, p < .001, partial η2 = .953), such that MCK scores increased over time. The interaction of time*ethnic groups was significant as well (F = 1101.412, p < .001, partial η2 = .833). Han and Yao students therefore demonstrated unique development trends at the four measurement points. Findings are summarized in .

Table 7. ANOVA results for MA

We further performed repeated ANOVAs to explore the variance between Han and Yao students. The MA growth trend for Han students surpassed that of Yao students. Moreover, Han students achieved higher MCK scores than Yao students at each measurement point (Grade 3: t = 5.631, p < .001; Grade 4: t = 6.690, p < .001; Grade 5: t = 19.515, p < .001; Grade 6: t = 27.688, p < .001).

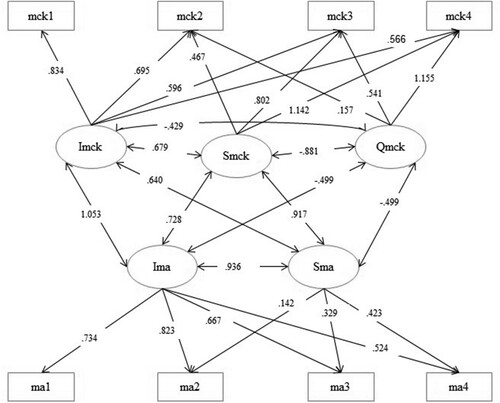

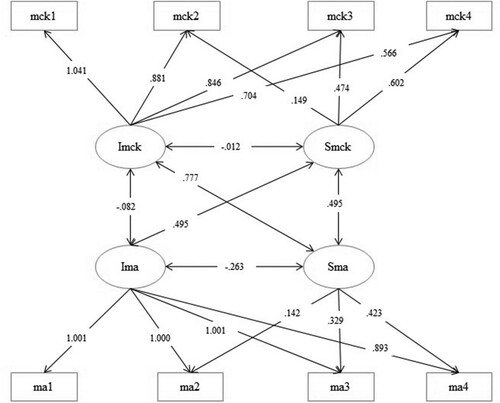

The third research question explored the relationship between metacognitive knowledge and morphological awareness in Han and Yao students. Parallel development models based on LGC were carried out to examine covarying development between MCK and MA in both student groups (see ). The data fit the models well.

Table 8. Summary of model fit indices for parallel development models

and display the covarying development between MCK and MA in Han students. MCK was based on the quadratic model, whereas MA was based on the linear model. These findings offer insight into the LGC. A significant positive correlation was observed between the intercept of MCK and the intercept and first slope of MA. These data suggest that a higher initial MCK level correlated with a higher initial MA level. In addition, faster MCK growth correlated with swifter MA development. The second MCK slope significantly correlated with the intercept of MA; thus, students with a higher initial MCK level also experienced quicker growth in MA. A covariation emerged accordingly.

Table 9. Intercept and slope coefficient for MCK and VK (Han students)

The covariation between MCK and MA in Yao students is depicted in and . A significant and positive correlation was found between the intercept of MCK and the intercept of MA. A higher initial MCK level was hence associated with a higher initial MA level. A significant correlation also manifested between the slope of MCK and the intercept and slope of MA, showing that a higher initial MCK level was tied to faster growth in MA; similarly, faster MCK growth was associated with faster MA growth.

Table 10. Intercept and slope coefficient for MCK and VK (Yao students)

Discussion

This study focused on the individual and covarying development of metacognitive knowledge and morphological awareness. We were especially interested in the differences between minority Yao and nonminority Han students in China. Our findings are outlined here based on a comparison with existing theories and empirical studies.

Research question 1: To what extent do Han and Yao students develop metacognitive knowledge and morphological awareness from Grades 3–6?

In the case of Han students, our findings support the quadratic model for MCK development. In the case of Yao students, the linear growth model fit better with MCK development. Slight differences appeared between both groups: whereas Yao students’ MCK development was straightforward and their scores increased over time, the enhancement in MCK among Han students seemed less straightforward—potentially due to Han students’ metacognitive readiness. These students possessed initially higher metacognitive knowledge than Yao students; the discrepancy may have influenced Han students’ subsequent MCK development. Generally, MCK increased steadily from third grade to sixth grade. Such results support previous findings of a noticeable rise in young learners’ metacognitive knowledge as their age increases (Annevirta and Vauras Citation2001; Annevirta et al. Citation2007; Marulis et al. Citation2016; Teng Citation2021; Teng and Zhang, L. J. Citation2021). In particular, the initial MCK level affected Yao students’ later MCK development. Consistent with Lepola et al. (Citation2020), young learners can develop metacognitive knowledge. Such development reflects learners’ ability to construct a mental representation of a pictorial narrative. Metacognitive knowledge measured in the present study reflects Flavell’s (Citation1979) theory of mind. Our findings indicate the potential for young learners to discern their own and others’ mental states, such as thoughts and feelings.

One noteworthy finding was that learners’ age and grade level seemed essential to metacognitive knowledge development (i.e. metacognitive skills related to cognition, learning, and memory). Marulis et al. (Citation2016) pointed out that although scores increased over the course of a school year, older children could perform better in metacognitive knowledge than young learners. In line with Teng, Wang, and Zhang (Citation2021), learners at different grade levels in an EFL writing context demonstrated significant differences in metacognitive strategies; thus, individual differences in age and grade level should be considered when describing young learners’ development of metacognitive knowledge.

Our findings suggest a linear model of MA development among Han and Yao students. MA development followed a cumulative pattern, showing that both student groups’ initial MA level could determine their subsequent MA. In Zhang, Koda, and Leong (Citation2016), morphological awareness at Time 1 (Grade 3) significantly predicted performance in lexical inference at Time 2 (Grade 4). That said, learners’ initial knowledge level in reflecting upon and manipulating morphemes could influence their subsequent morphological awareness. This study mainly involved segmenting a word into its constituent morphemes and synthesizing the morphemes into a word. As such, whether among minority or nonminority learners, those with a higher level of morphological awareness were more likely to develop knowledge to immediately resolve lexical gaps. Han students already had greater morphological awareness than Yao students, hence why the former group consequently developed a larger repertoire of morphological knowledge.

Research question 2: Do minority students and nonminority students differ in their metacognitive knowledge and morphological awareness from Grades 3–6?

Overall, Yao and Han students began learning English in third grade, although Han students had stronger and more persistent sufficiency in metacognitive knowledge and vocabulary knowledge than Yao students. The significant interaction of time*ethnic groups specified that the student groups exhibited different development trends at the four measurement points. These results highlight individual differences. For example, some Yao students in Grade 6 developed lower metacognitive knowledge than Han students in Grade 3. Minority and nonminority students appeared to start with large discrepancies in metacognitive knowledge and morphological awareness, which remained after several years of learning. Research involving minority learners in Spain (Kieffer and Lesaux Citation2012) featured linear growth models showing that minority learners exhibited true growth in morphological awareness and vocabulary knowledge between Grades 4 and 7. Although Kieffer and Lesaux (Citation2012) did not compare minority and nonminority students, their results suggested that minority learners lagged behind the national standard. In a recent study (Teng and Zhang CitationUnder review), even though Yao minority students acquired metacognitive knowledge and vocabulary knowledge, they did not reach the level of Han students between Grades 3 and 6. Such differences were detected in terms of metacognitive knowledge and morphological awareness. No demonstrable rationale could be drawn from these findings. However, the outcomes may be due to minority learners’ lack of English language input; they received less English training prior to their formal English instruction. English picture books are also not readily available to this group despite the known importance of reading materials as linguistic input in language learning (Zhang Citation2018). Future studies could include this variable and further explore how learners’ prior language learning experiences affect later English morphological awareness.

We could also apply the developmental skill-learning gap hypothesis to explain Han and Yao students’ growth. As less proficient learners grow, the skill-learning gap between them and their more proficient peers widens (Wall Citation2004). This hypothesis was developed based on learners with mobility challenges in physical activity settings. However, it may be relevant to minority students with deficiencies in metacognitive knowledge and vocabulary knowledge, as these weaknesses can develop into large gaps in comparison with nonminority learners as learning demands increase. Matthew effects can also be applied to explain our findings: Cain and Oakhill (Citation2011) discovered that learners’ initial levels of reading experience and reading comprehension predicted subsequent vocabulary knowledge development. Reading comprehension and vocabulary are usually closely related (Hirsh and Nation Citation1992; Nation and Macalister Citation2021; Saragi, Nation, and Meister Citation1978). In the present study, Yao students who entered Grade 3 with limited morphological knowledge in English could encounter a downward spiral that accelerated in later years. These students found it challenging to develop the morphological knowledge and metacognitive knowledge necessary to take initiative in morphology learning. Factors other than learners’ underlying cognitive potential and morphological awareness before the start of schooling could presumably result in variation in developing metacognitive knowledge and morphological awareness. Yao students were learning English as a third language, whereas Han students learned English as a second language based on Mandarin. Yao students may thus have lower Mandarin proficiency. Such cross-linguistic transfer, although not tested in this study, has been identified as a key variable influencing the development of morphology (Zhang, Koda, and Leong Citation2016). This assumption needs further exploration when comparing minority and nonminority students.

Research question 3: To what extent is Han and Yao students’ metacognitive knowledge level correlated with the development of morphological awareness?

This question aimed to clarify how young learners’ MCK level affected their MA development. Findings supported a relationship between MCK and MA in both Han and Yao students: those with higher levels of MCK achieved higher MA scores at each measurement point. Such patterns are in line with Teng (Citation2021). Even though Teng (Citation2021) focused on vocabulary knowledge, it is reasonable to consider their work given the significant association between vocabulary knowledge and morphological awareness (Lam et al. Citation2012). The present study implied a role of metacognitive knowledge in morphological awareness. The present study did not provide evidence for the predictive capacity or rate of metacognitive knowledge on morphological awareness. Awareness of morphology may nevertheless inform metacognitive knowledge (e.g. developing morphological awareness may enhance metacognitive knowledge). This proposition was not explored in our case.

One noteworthy finding is that the relationship between MCK and MA covaries, which implies that MCK and MA can evolve simultaneously. van Steensel et al. (Citation2016) found evidence for the role of MCK in developing vocabulary knowledge among minority learners. In contributing to previous studies, we argue that a strong initial MCK level is vital to subsequent MA development. However, relatively less developed MCK was observed in Yao students. It may be important to teach students about metacognitive knowledge or strategies for learning, understanding, and memory to increase learners’ morphological awareness.

Limitations and implications

We acknowledge several limitations of our study. First, the MA test only covered derivational and compound awareness. More MA tests should be used in future work to assess words’ morphemic patterns and learners’ knowledge of what a morpheme means. Second, we only controlled for participants’ metacognitive development. Additional factors, including nonverbal intelligence, working memory, and even cross-linguistic transfer, should be explored to delineate the multilingual development of Yao and Han students. Third, the relationship between MCK and MA was potentially reciprocal rather than unidirectional. While metacognitive knowledge can predict morphological awareness over time, exposure to morphology may facilitate the development of metacognitive knowledge. We did not consider such reciprocal relations in this longitudinal study. Finally, longitudinal research requires repeated testing. This issue may raise questions about test–retest effects even though our participants did not display ceiling effects.

Despite these limitations, this research has implications for the development of metacognitive knowledge and vocabulary knowledge, particularly among minority multilingual young learners. Metacognitive knowledge is crucial to young learners’ possible development of morphological awareness. Students who enter school with limited metacognitive knowledge have special instructional needs. Targeted lessons can help them take control of their morphology learning. Yao-speaking learners displayed a relatively lower level of English morphology in this study. This phenomenon may be related to their linguistic landscape, in that they predominantly speak the Yao language and use Mandarin as a second language; school instruction is also in Mandarin. The lack of target-language input may have influenced their acquisition of English morphology. Thus, compared with Han students, Yao learners showed a relatively lower level of English morphology. The development of metacognitive knowledge and morphology in Yao students deserves attention from scholars interested in bilingualism and multilingualism within China and beyond.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anglin, J. M. 1993. “Vocabulary Development: A Morphological Analysis.” Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 58.

- Annevirta, T., E. Laakkonen, R. Kinnunen, and M. Vauras. 2007. “Developmental Dynamics of Metacognitive Knowledge and Text Comprehension Skill in the First Primary School Years.” Metacognition and Learning 2: 21–39.

- Annevirta, T., and M. Vauras. 2001. “Metacognitive Knowledge in Primary Grades: A Longitudinal Study.” European Journal of Psychology of Education XVI (2): 257–282.

- Brown, A. L. 1987. “Metacognition, executive control, self-regulation, and other more mysterious mechanisms.” In Metacognition, motivation and understanding, edited by F. Weinert, and R. Kluwe, 65–116. Hillsadle, N. Y.: Erlbaum.

- Cain, K., and J. Oakhill. 2011. “Matthew Effects in Young Readers.” Journal of Learning Disabilities 44 (5): 431–443.

- Carlisle, J. F. 2000. “Awareness of the Structure and Meaning of Morphologically Complex Words: Impact on Reading.” Reading and Writing 12: 169–190.

- Efklides, A. 2008. “Metacognition.” European Psychologist 13 (4): 277–287.

- Feng, A. W., and B. Adamson. 2018. “Language Policies and Sociolinguistic Domains in the Context of Minority Groups in China.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 39 (2): 169–180.

- Flavell, J. H. 1979. “Metacognition and Cognitive Monitoring: A new Area of Cognitive-Developmental Inquiry.” American Psychologist 34: 906–911.

- Geiser, C. 2013. Data Analysis with Mplus. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Hirsh, D., and I. S. P. Nation. 1992. “What Vocabulary Size is Needed to Read Unsimplified Texts for Pleasure?” Reading in a Foreign Language 8 (2): 689–696.

- Hu, L., and P. M. Bentler. 1999. “Cutoff Criteria for fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus new Alternatives.” Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6: 1–55.

- Hu, M., and I. S. P. Nation. 2000. “Vocabulary Density and Reading Comprehension.” Reading in a Foreign Language 23: 403–430.

- Jiang, Y. L., and L. J. Kuo. 2019. “The Development of Vocabulary and Morphological Awareness: A Longitudinal Study with College EFL Students.” Applied Psycholinguistics 40 (4): 877–903.

- Kieffer, M. J., and N. K. Lesaux. 2012. “Development of Morphological Awareness and Vocabulary Knowledge in Spanish-Speaking Language Minority Learners: A Parallel Process Latent Growth Curve Model.” Applied Psycholinguistics 33: 23–54.

- Ku, Y.-M., and R. C. Anderson. 2003. “Development of Morphological Awareness in Chinese and English.” Reading and Writing 16: 399–422.

- Kuo, L.-J., and R. C. Anderson. 2006. “Morphological Awareness and Learning to Read: A Cross-Language Perspective.” Educational Psychologist 41: 161–180.

- Lam, K., X. Chen, E. Geva, Y. Luo, and H. Li. 2012. “The Role of Morphological Awareness in Reading Achievement among Young Chinese-Speaking English Language Learners: A Longitudinal Study.” Reading and Writing 25 (8): 1847–1872.

- Lepola, J., A. Kajamies, E. Laakkonen, and P. Niemi. 2020. “Vocabulary, Metacognitive Knowledge and Task Orientation as Predictors of Narrative Picture Book Comprehension: From Preschool to Grade 3.” Reading and Writing 33 (5): 1351–1373.

- Marulis, L. M., S. T. Baker, and D. Whitebread. 2020. “Integrating Metacognition and Executive Function to Enhance Young Children’s Perception of and Agency in Their Learning.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 50: 46–54.

- Marulis, L. M., A. S. Palincsar, A. L. Berhenke, and D. Whitebread. 2016. “Assessing Metacognitive Knowledge in 3–5 Year Olds: The Development of a Metacognitive Knowledge Interview (McKI) 339–368 year Olds: The Development of a Metacognitive Knowledge Interview (McKI).” Metacognition and Learning 11 (3): 339–368.

- McCutchen, D., L. Green, and R. D. Abbott. 2008. “Children’s Morphological Knowledge: Links to Literacy.” Reading Psychology 29 (4): 289–314.

- Nation, I. S. P., and J. Macalister. 2021. Teaching ESL/EFL Reading and Writing. (Second Edition). New York: Routledge.

- Perfetti, C., and J. Stafura. 2014. “Word Knowledge in a Theory of Reading Comprehension.” Scientific Studies of Reading 18: 22–37.

- Perry, N. 1998. “Young Children’s Self-Regulated Learning and Contexts That Support it.” Journal of Educational Psychology 90: 715–729.

- Qin, C., and F. Teng. 2017. “Assessing the Correlation between Task-Induced Involvement Load, Word Learning, and Learners’ Regulatory Ability.” Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics 40 (3): 261–280.

- Saragi, T., I. S. P. Nation, and G. F. Meister. 1978. “Vocabulary Learning and Reading.” System 6 (2): 72–78.

- Sato, M. 2021. “Metacognition.” In The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition and Individual Differences, edited by S. Li, P. Hiver, and M. Papi. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Schraw, G. 1994. “The Effect of Metacognitive Knowledge on Local and Global Monitoring.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 19: 143–154.

- Shahar-Yames, D., and A. Prior. 2018. “The Challenge and the Opportunity of Lexical Inferencing in Language Minority Students.” Reading and Writing 31 (5): 1109–1132.

- Teng, F. 2021. “Exploring Awareness of Metacognitive Knowledge and Acquisition of Vocabulary Knowledge in Primary Grades: A Latent Growth Curve Modelling Approach.” Language Awareness 1–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2021.1972116.

- Teng, F., C. Wang, and L. J. Zhang. 2021. “Assessing Self-Regulatory Writing Strategies and their Predictive Effects on Young EFL Learners’ writing Performance.” Assessing Writing 51: 100573. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2021.100573.

- Teng, F., and L. J. Zhang. 2021. “Development of Children’s Metacognitive Knowledge, Reading, and Writing in English as a Foreign Language: Evidence from Longitudinal Data Using Multilevel Models.” British Journal of Educational Psychology 91 (4): 1202–1230. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.v91.4.

- Teng, F., and D. Zhang. 2021. “Task-Induced Involvement Load, Vocabulary Learning in a Foreign Language, and their Association with Metacognition.” Language Teaching Research. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211008798.

- Teng, F., and L. J. Zhang. Under review. “Ethnic minority multilingual young learners' longitudinal development of metacognitive knowledge and breadth of vocabulary knowledge.” Manuscript submitted for publication.

- van Steensel, R., R. Oostdam, A. van Gelderen, and E. van Schooten. 2016. “The Role of Word Decoding, Vocabulary Knowledge and Meta-Cognitive Knowledge in Monolingual and Bilingual low-Achieving Adolescents’ Reading Comprehension.” Journal of Research in Reading 39 (3): 312–329.

- Wagner, R. K., A. E. Muse, and K. R. Tannenbaum. 2007. “Promising Avenues for Better Understanding Implications of Vocabulary Development for Reading Comprehension.” In Vocabulary Acquisition: Implications for Reading Comprehension, edited by R. K. Wagner, A. E. Muse, and K. R. Tannenbaum, 276–291. New York: Guilford Press.

- Wall, A. T. 2004. “The Developmental Skill-Learning gap Hypothesis: Implications for Children with Movement Difficulties.” Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly 21 (3): 197–218.

- Zhang, L. J. 2002. “Metamorphological Awareness and EFL Students' Memory, Retention, and Retrieval of English Adjectival Lexicons.” Perceptual and Motor Skills 95 (3): 934–944.

- Zhang, L J. 2018. “Learning Reading.” In The Cambridge Guide to Learning English as a Second Language, edited by A. Burns and J. C. Richards, 213–221. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Zhang, D. B., K. Koda, and C. Leong. 2016. “Morphological Awareness and Bilingual Word Learning: A Longitudinal Structural Equation Modeling Study.” Reading and Writing 29 (3): 383–407.

- Zhang, D. B., K. Koda, and X. Sun. 2014. “Morphological Awareness in Biliteracy Acquisition: A Study of Young Chinese EFL Readers.” International Journal of Bilingualism 18 (6): 570–585.

- Zhang, L. J., and D. L. Zhang. 2018. “Metacognition in TESOL: Theory and practice.” In The TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching, Vol. II: Approaches and Methods in English for Speakers of Other Languages, edited by J. I. Liontas and A. Shehadeh, 682–792. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.