ABSTRACT

The number of immigrant students in Finland is increasing; thus, this qualitative case study investigates ways of providing targeted support measures for recently arrived Finnish language learners (RAFLLs) in Finnish lower secondary education. Focusing on linguistic responsiveness, the teaching arrangements and support measures are examined not only from a teacher perspective but also from the perspectives of municipality- and national-level actors by utilizing ecological systems theory. The findings revealed two themes, sustainability and holistic linguistic responsiveness, that reflect the core issues of the current challenges related to organizing teaching and support measures for RAFLLs. Sustainable support measures should be developed on and between all ecosystemic levels. Furthermore, measures for supporting RAFLLs must be developed with an all-encompassing linguistically responsive approach (LRA). The development processes require a more coherent dialogue between the schools, the municipalities, and the national-level actors.

Introduction

Increased migration is one of the main effects of globalization and has resulted in broader cultural and linguistic diversity in schools in many countries. The arrival of a relatively large number of refugees in Europe in 2015–2016 implicated the necessity of reforming educational measures to meet the needs of recently arrived immigrant students (Bunar and Juvonen Citation2021; Horgan et al. Citation2021). Currently, the crisis in Ukraine is creating a substantial number of refugees, challenging educational systems throughout Europe.

Education for children and youths is a human right (Guo-Brennan and Guo-Brennan Citation2021); thus, education systems must take significant actions to meet the needs of recently arrived students (e.g. Horgan et al. Citation2021; Koehler and Schneider Citation2019), regardless of the reasons for migration. Furthermore, educational systems play a critical role as a point of contact between immigrants and their new home country; teachers and other education professionals contribute to the socialization of the newly arrived (Mickan et al. Citation2007), and peer support is of significant importance (Randell and Osman Citation2020). From an ecological perspective, the need for schools to develop into spaces where reciprocal learning between individuals and the environment should be acknowledged (Woods Citation2009).

The education systems of the different European countries have a variety of complex structures and rules, and organizing access to education for refugee children and youths has been executed primarily within the existing logic and idiosyncrasies of the respective systems (Koehler and Schneider Citation2019). There are several examples of educational solutions for responding to the different pedagogic and emotional needs of recently arrived students; however, supports in formal education may not always address the individual needs of immigrant students, which can be challenging to identify (Horgan et al. Citation2021), as these students come from various backgrounds, and their support needs are based on their life experiences (Guo-Brennan and Guo-Brennan Citation2021; Koehler and Schneider Citation2019) and their linguistic and educational backgrounds (Rodríguez-Izquierdo and Darmody Citation2019). It is widely acknowledged that students from linguistically and culturally heterogeneous backgrounds often encounter linguistic barriers in educational settings in their new home countries (e.g. Borgna Citation2017; Smythe Citation2022).

In Europe, educational systems have responded to cultural and linguistic diversity (CLD) in many ways (Rodríguez-Izquierdo, González Falcon, and Goenechea Permisán Citation2020). The majority of EU countries (24 out of 27) offer language support classes for recently arrived students (Gitschthaler et al. Citation2021), who are generally expected to learn the new language and culture quickly (e.g. Hilt Citation2017). The duration of the language support classes (Koehler and Schneider Citation2019) and the pedagogical support measures vary from submersive ‘sink or swim’ approaches to pull-out language instruction and bilingual education (Erling, Gitschthaler, and Schwab Citation2022; Thorstensson Dávila Citation2012). In situations where recently arrived students have a limited educational history—meaning that both the education system and the language of schooling are new for the students and their families—additional support in the language of schooling can be especially advantageous (Gitschthaler et al. Citation2021; Thorstensson Dávila Citation2012).

In addition to the overarching educational systems, teachers’ beliefs and approaches related to diversity play an important role in teaching immigrant students (Heikkola et al. Citation2022; Rodríguez-Izquierdo, González Falcon, and Goenechea Permisán Citation2020). Taking students’ diverse cultural and educational backgrounds into account is important, and considering language-related issues is also necessary (Guo-Brennan and Guo-Brennan Citation2021; Vigren et al. Citation2022). Linguistically responsive teaching (LRT) builds on valuing cultural and linguistic diversity and seeing all languages as equally valuable and as resources for learning (Lucas and Villegas Citation2011, Citation2013). A linguistically responsive teacher understands the central role of language in all learning and knows how to implement pedagogies that support language learners (e.g. Heikkola et al. Citation2022). The aim of LRT is to advocate for multilingual students to be able to participate fully in schools and the wider society (Lucas and Villegas Citation2011, Citation2013). Indeed, mastering the language of schooling is one of the most important factors of good educational outcomes for students (Harju-Luukkainen and McElvany Citation2018), and language skills are crucial for social communication in the new home country (e.g. Guo-Brennan and Guo-Brennan Citation2021; Horgan et al. Citation2021). However, according to previous research, mainstream teachers possess limited knowledge about and competences for teaching subject content in a linguistically responsive manner (e.g. Alisaari et al. Citation2019; Lopez Citation2021).

This study focuses on educational arrangements and support measures for lower secondary-level students, aged 13–16, who recently moved to Finland and are learning the language of schooling (Finnish); they are referred to as recently arrived Finnish language learners (RAFLLs; see also Harju-Autti et al. Citation2021). Thus, this study draws on a Vygotskian perspective, according to which language is perceived as a central tool for learning and development (Vygotsky Citation1978) and a primary resource for enacting social identity and displaying membership in social groups (Miller Citation2000). It is important to note that Estonian is practically the only language of the Finno-Ugric language family that resembles Finnish (Honko, Ahola, and Hirvelä Citation2021), which implies that the linguistic distance between Finnish and other languages is great (see also Nisbet et al. Citation2021).

In Finland, national funding covers 900–1000 h (approximately one academic year) of support for recently arrived students, after which, based on the principles of inclusivity (Finlex Citation2011), they participate in mainstream education (Finnish National Board of Education, henceforth FNBE Citation2015). Overall, the Finnish educational system relies on an inclusive orientation emphasizing preemptive support for all students’ learning and well-being (Ainscow Citation2020; Rajakaltio and Mäkinen Citation2014). This is based on the Education for All (EFA) approach (UNESCO Citation2017), which is a global commitment to providing quality basic education for all children, youths, and adults. In Finland, an inclusion-oriented three-tiered support model that offers a gradually strengthening support structure (general support, intensified support, and special-needs support) has been in force since 2011 (Finlex Citation2011).

Despite the country’s good educational reputation, Finland has been among the most unequal Western European countries for immigrant students (e.g. Borgna Citation2017). This can be seen in the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) results, which show a large achievement gap between immigrant and native students in Finland (Harju-Luukkainen and McElvany Citation2018; Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD], Citation2018). This may be partially explained by language gaps and the socioeconomic status of immigrant students’ families (Ahonen Citation2021). Furthermore, about 14% of young people in Finland, regardless of their linguistic background, do not reach a sufficient level of literacy to be prepared for further studies and life as contributing members of society (Ahonen Citation2021). In a text-based society, this calls for further action (Sulkunen Citation2013): ‘Language proficiency must be at the core of educational policies and integration processes in the destination countries, alongside diverse, coherent, intercultural education policy’ (Rodríguez-Izquierdo and Darmody Citation2019, 52).

This study focused on gaining a holistic overview of the educational arrangements and support measures targeted at RAFLLs. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model (Citation1979, Citation1992/Citation2005) of human development was used as a theoretical frame to gain a deeper understanding of the Finnish educational system as a multilayered entity in which educational arrangements are developed by actors at the classroom level into education policy making. The aim of this study was to understand the perspectives of educational experts (i.e. teachers, planners, and administrators) who work at different levels of the educational ecosystem to organize or implement RAFLL support in order to highlight the need for developing linguistic support for students learning the language of schooling in their new home country. This study was guided by the following research questions:

What are the current issues concerning the teaching arrangements and support measures targeted at RAFLLs in Finnish lower secondary education?

How should the support measures be further developed?

Toward linguistically responsive education

Developing LRT to meet the needs of language learners is a necessity (Lopez Citation2021; Lucas and Villegas Citation2011, Citation2013). The framework of LRT (Lucas and Villegas Citation2011, Citation2013) addresses the academic needs of language learners: linguistically responsive teachers know how to teach language and how to teach about the language (Lopez Citation2021). Furthermore, the important role of language across a curriculum, not only in language classrooms but in connection to all subjects (Heikkola et al. Citation2022; Schleppegrell Citation2020), requires all teachers to carefully plan their lessons as a site for language learning (e.g. Schleppegrell Citation2020).

The LRT framework (Lucas and Villegas Citation2011, Citation2013) is an educational paradigm entailing a set of orientations and pedagogical skills that teachers need to effectively teach language learners despite any cultural and linguistic barriers (e.g. Lopez Citation2021). LRT is built on three orientations. First, it is built on sociolinguistic consciousness, with an awareness that language, culture, and identity are inseparable, and that language use and its sociopolitical dimensions are always interconnected with language education. Second, linguistic diversity must be appreciated and cultivated. Third, linguistically responsive teachers understand that language learners need educational opportunities and support to gain access to social and political capital (Lucas and Villegas Citation2011, Citation2013).

In addition to these orientations, linguistically responsive teachers must master different strategies for learning about the linguistic and academic backgrounds of language learners, as well as the skills for applying key principles of second language learning in their teaching (Lucas and Villegas Citation2011, Citation2013). Moreover, a linguistically responsive teacher recognizes the language demands of learning new topics through a new language and masters a repertoire of ways to scaffold language learners with extralinguistic supports and well-formulated instructions (Lucas and Villegas Citation2011, Citation2013).

In recent years, the LRT framework has inspired many teachers, teacher educators, and researchers and has been used to analyze teachers’ attitudes, beliefs (e.g. Alisaari et al. Citation2019; Vigren et al. Citation2022), and pedagogical practices (Heikkola et al. Citation2022; Lopez Citation2021). These studies have highlighted the crucial importance of developing both pre- and in-service teacher education in order to enhance linguistically responsive pedagogy. In the current study, the LRT framework (Lucas and Villegas Citation2011, Citation2013) was used as a reflective tool for mirroring the educational ecosystem from a linguistically responsive perspective.

The ecosystem framework

Ecological systems theory offers a useful framework for discussing the contingencies between individuals and their environments (e.g. Chu, Liu, and Fang Citation2021). The interconnections between and within ecosystems form a complex ecology; thus, an overall ecosystem is more than the sum of its parts (Moate et al. Citation2021). In this study, Bronfenbrenner’s theory (Citation1992/Citation2005) was applied to examine Finnish basic education as a set of ecosystems, with a focus on linguistic support for RAFLLs.

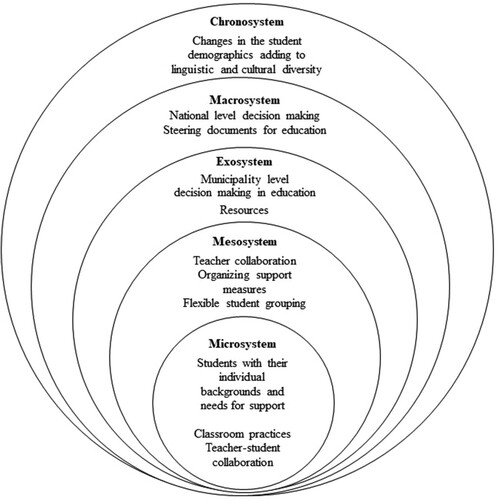

The education system can be perceived as a set of nested ecosystems (van Lier Citation2004), each of which has its own sets of artifacts and patterns of operations and relations (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979; van Lier Citation2004). The microsystem is a developing person’s most immediate environment and includes settings such as home, the classroom, and school. The mesosystem encompasses the interactions between two or more microsystems to which the developing member belongs. The exosystem comprises the linkages and processes occurring in two or more settings that directly influence the developing person’s immediate environment; however, on the individual level, ways to influence these processes are limited. The macrosystem forms an overarching pattern of micro-, meso-, and exosystems, representing the culture and subculture of the surrounding context (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979; van Lier Citation2004). Furthermore, the chronosystem, added later by Bronfenbrenner (Citation1992/Citation2005), represents changes to society and culture over time.

For this study, ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979, Citation1992/Citation2005) provides a useful theoretical framework for studying the contexts in which educational experts work. The focus was on examining the contexts of and contingencies between the different ecosystemic levels of the education system with regard to providing linguistic support for RAFLLs (see ).

Figure 1. The ecosystemic levels of the education system (adapted from Bronfenbrenner Citation1979, Citation1992/Citation2005)

The microsystem represents teachers’ immediate working contexts—classrooms with students and their linguistically and culturally diverse backgrounds. The mesosystem comprises all collaboration that takes place among students, teachers, and other school professionals in educational communities. The exosystem refers to municipality-level administrative processes and decision-making. The national-level administrative views connected to steering documents, such as legislation (Finlex Citation2011) and the national core curriculum for basic education (FNBE, Citation2014), are positioned at the macrosystemic level. The growing number of RAFLLs in Finland represents changes at the chronosystemic level. Although the importance of examining family relations and the life experiences of immigrant families within the ecosystem is indisputable, in this study, the focus was on the educational context only.

The Finnish context

This study was conducted in Finland, where the majority of the population with a Finnish background speaks Finnish as their first language (L1). Swedish, the other official national language, is spoken by a little over 5% of people with a Finnish background (Official Statistics of Finland Citation2021). In addition, the Sámi languages (North Sámi, Inari Sámi, and Skolt Sámi), Romani, and Finnish and Swedish sign languages have legislative rights in the Finnish constitution (e.g. Ministry of Justice Citation2022). The largest immigrant language groups are Russian, Estonian, Arabic, English, and Somali (Official Statistics of Finland Citation2019); altogether, over 200 languages are spoken in Finland (Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare Citation2020). In 1990, the number of inhabitants who spoke a language other than Finnish, Swedish, or Sámi as their L1 was 24,783 (0.5% of the population); at the end of 2020, this number had increased to 432,800 (7.8% of the population; Official Statistics of Finland Citation2021). This change in the chronosystem is also present in student demographics.

Considering the macrosystem, basic education throughout Finland includes grades 1–9 and is free for all age groups (Ahonen Citation2021). At the primary level (grades 1–6), most teaching is provided by a class teacher. In lower secondary education (grades 7–9), subjects are taught by subject-matter teachers who have majored in the subject they teach and minored in pedagogical studies. With regard to both class-teacher and subject-teacher education in Finland, courses related to CLD are limited and vary between universities (e.g. Szábo et al. Citation2021).

As a macro-level steering document, the national core curriculum (FNBE, Citation2014) values cultural and linguistic diversity and requires language-aware pedagogy: ‘In a language-aware school, each adult is a linguistic model and also teachers of the language typical of the subject they teach’ (29). The curriculum emphasizes that language-aware teaching is relevant and beneficial for all students, independent of their linguistic backgrounds (Alisaari Citation2020). The concept of teacher language awareness is commonly defined as ‘explicit knowledge about language, and conscious perception and sensitivity in language learning, language teaching and language use’ (Association for Language Awareness Citation2022; Hu and Gao Citation2021). In this study, teachers’ language awareness was examined according to the principles of LRT (Lucas and Villegas Citation2011, Citation2013), including the orientations, skills, and knowledge within the framework.

At the exosystemic level, teaching arrangements targeted at immigrant students have been developed in recent years. Current structures include about one year (900 or 1000 h, depending on grade level) of preparatory education (henceforth prep-ed; FNBE, Citation2015; Koehler and Schneider Citation2019). The municipalities receive funding for organizing prep-ed, but they are not obliged to offer it. Prep-ed takes place either in separate classes or by integrating recently arrived students into mainstream basic education. After the year of prep-ed, immigrant students usually enter mainstream classes in basic education.

At the meso- and microsystemic levels, a curriculum of Finnish as a second language and literature (FSLL) is offered for studying Finnish. However, FSLL focuses on Finnish as a school subject; it is not a pedagogical support measure for learning the content—or language— of other subjects (FNBE, Citation2022). Furthermore, ways of organizing FSLL vary between municipalities (Owal Group Citation2022). Providing immigrant students with L1 classes and other support measures in their L1s is highly recommended in the macrolevel steering documents (e.g. FNBE, Citation2014). Models to support immigrant students after the year of prep-ed have been developed in different parts of the country as exosystemic-level solutions, but studies on these models are not available (Pyykkö Citation2017). However, the support measures targeted at RAFLLs who are shifting from prep-ed to mainstream education are seen as inadequate by teachers (Owal Group Citation2022).

The focus of language education in Finland has mainly been on language, literature, subject-specific knowledge, and teaching foreign languages in monolingual settings (e.g. Salo Citation2009), not on teaching subject content for students who are simultaneously learning the language of schooling (e.g. Schleppegrell Citation2020). However, development projects in pre- and in-service teacher education are raising awareness, and programs are aiming to change teachers’ beliefs from seeing multilingualism as a problem to seeing it as a resource (Szábo et al. Citation2021) and an important feature of the curriculum and the school culture (e.g. Cummins Citation2021).

In an increasingly globalized world, the number of students simultaneously learning the language of schooling and subject content continues to grow (e.g. Schleppegrell Citation2020). However, teaching subjects such as biology or history with a content and language integrated (CLIL) approach in mainstream education has received relatively little attention, not only in Finland (e.g. Harju-Autti et al. Citation2021) but also in other countries (e.g. Erling, Gitschthaler, and Schwab Citation2022).

Methodology

This research utilized a qualitative case study, which is an in-depth empirical inquiry into a specific and complex phenomenon (the case) set within its real-world, authentic, and localized context with constructivist assumptions (Stake Citation1995). This methodology allows researchers to discuss the phenomenon from various viewpoints and build a dialogue between experiences and theoretical knowledge. This case study explored ways of supporting RAFLLs in Finnish basic education after their year of prep-ed. With regard to the initiative for and background of this study, the first author’s experience as a teacher of linguistic support from 2014–2016 was used for developing the research design. The value- and bias-laden nature of this insider view (Boblin et al. Citation2013; Stake Citation1995) was acknowledged throughout the process.

Ethics

This study was conducted according to the ethical principles of research in Finland (Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK Citation2019). Participation in this study was voluntary, and participants were informed that taking part implied consent. Moreover, participants could withdraw from the process if they wanted to. The participants were given detailed information about the research, including information about their anonymity and the researchers’ contact information. The data are stored in an online storage service with two-factor authentication to ensure that the data remain protected. After the publication of this article, the data will be destroyed. Due to the first author’s experience as a linguistic support teacher and the prolonged period of time spent studying the phenomenon, the positionality of the first author was carefully reflected on throughout the research process.

Study participants and data collection

The participants in this study (N = 22) represented different levels of the education system in accordance with the aforementioned ecosystemic levels. Teachers (n = 13) represented the local (micro- and mesosystemic) levels. Administrators (n = 6) represented the regional (exosystemic) level. The local- and regional-level participants comprised eight different municipalities from different parts of the country. Participants from the National Agency for Education (n = 2) and the Ministry of Education and Culture (n = 2) represented the national (macrosystemic) level. The data were collected through Zoom interviews, email correspondence, and phone interviews. The participants were contacted by email via the first author’s networks at the beginning of 2022. Purposive sampling was used to select the professional participants for this study. The participants were asked to reflect on the overall structures for providing pedagogical support for RAFLLs after their year of prep-ed. They were asked to portray these support measures from a professional perspective and give their opinions on how the measures should be developed. The Basic Education Act (Finlex Citation2011), the national core curriculum for basic education (EDUFI, Citation2014), and the national core curriculum for preparatory education (EDUFI, Citation2015) were used as background data. Although the core curriculum for basic education (EDUFI, Citation2014) values and supports multilingualism and language awareness, recent studies (Alisaari Citation2020; Heikkola et al. Citation2022) have suggested that the macro-level policy documents do not align with municipality and school practices; there are tensions between the macro-level documents and the practices taking place at the inner ecosystemic levels. To complement the information gained from the policy documents, interviewing experts from the different ecosystemic levels provided insightful data and perspectives from and between different experts in the educational context (see Bronfenbrenner Citation1979, Citation1992/2005).

Data analysis procedures

Directed content analysis and the initial coding developed by Hsieh and Shannon (Citation2005) were used for the analysis. Directed content analysis was used to identify and understand the systemic-level linguistic barriers that RAFLLs face in Finnish lower secondary education. To code the data, the four levels of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory (Citation1992/Citation2005) were used.

The dataset comprises 53 pages of transcripts (12-point font, 1.5 line spacing) of the participants’ thoughts on the overall educational structures and the needs for developing support measures for RAFLLs. Although the participants were actors at different ecosystemic levels in basic education (after Bronfenbrenner Citation1979, Citation1992/Citation2005), the data were analyzed as an entity. The analysis process entailed four phases. After a close reading of the transcribed data, the analysis units were formed: the analysis units for organizing the data were an extensive, meaningful description or a brief notional statement. Units were first allocated according to Bronfenbrenner’s systemic levels (Citation1992/Citation2005). It is worth noting that the units were analyzed without consideration for participants’ positioning in the ecosystem. Units with similar meanings were assembled under emerging issue topics (). Next, the relationships between the issue topics and the ecosystemic levels were discussed to gain a holistic overview of the complexities of CLD in lower secondary education. Finally, two main themes emerged: sustainability and linguistic responsiveness. The first three steps of the analysis were conducted by the first author. For researcher triangulation, the fourth step of the analysis, critical reflection on the dialogue of the topics and themes, was conducted jointly.

Table 1. An overview of the analysis unit examples and issue topics related to the emerged themes

To present the participants’ role in this study, direct quotations have been used. Participants’ roles are indicated as TR for teacher, MLR for municipality-level representative, and NaLR for national-level representative.

Findings

The actors at all ecosystemic levels seemed to be aware of the current situation and the importance of developing teaching arrangements and support measures to better meet RAFLLs’ needs. Regardless of their positioning within the ecosystem, the participants’ remarks concerned all the ecosystemic levels. This indicates a shared frustration concerning the lack of dialogue between the different levels. The findings indicate that, to some extent, a multilayered dialogue between and across the different ecosystemic levels does exist, but the power dynamics are imbalanced: the actors at the micro and meso levels have less power to mandate change than those at the exo- and macrosystemic levels.

The national level steering documents enable adapting the system to align with a linguistically responsive approach (LRA), but the municipalities and schools make their own interpretations, which may not align with an LRA. The participants in this study—specialists in this topic—see the importance of an LRA throughout the ecosystemic levels of lower secondary education.

Sustainable support for RAFLLs

The need for more coherent steering. The participants mentioned the need for more coherent steering at the macro level, referring to Finnish educational legislation, the regulations set by the Ministry of Education and Culture, and the national core curriculum created by the Finnish National Agency for Education. While these inclusion-oriented steering documents enable the provision of sustainable support and emphasize early intervention for problems related to all students’ learning, schooling, and well-being ‘directly as the need arises’ (Finlex Citation2011), there are no solid guidelines specifically addressing support for CLD in basic education:

From the national perspective, it seems that pedagogical practices differ a lot, and the teachers have to adjust their own solutions for teaching and organizing support as well as for evaluating RAFLLs without any guidelines from the national level. (TR11)

Moreover, although the aim of the national three-tier support model (Finlex Citation2011) is a case-by-case approach targeting support that is best for the student, there is no guarantee that the support will actually be executed. Furthermore, the three-tiered support model should address both learning difficulties and language proficiency, as indicated by a national-level participant:

It is important to take language competencies into consideration when the three-tier support model is used. (NaLR2)

Based on the findings of this study, the core issue from the RAFLLs’ perspective seems to lie within the discrepancies between the macro-level steering documents and the actual time that is needed for learning a new language. At the micro level, RAFLLs can still be considered language learners (e.g. Schleppegrell Citation2020) after the 900 or 1000 h of funded prep-ed (FNBE, Citation2015). On the one hand, the limited period of separate prep-ed is in line with the principles of inclusive education, emphasizing each student’s right to participate in mainstream education (Erling, Gitschthaler, and Schwab Citation2022). On the other hand, the short-term prep-ed is not sufficient for students who would benefit from linguistic (and possibly other types of) support for a longer period of time. The educational structures rely on the one year of prep-ed: the macro level steering does not acknowledge the need for additional linguistic support at the micro level after that year.

Inclusive education and cultural and linguistic diversity are national-level issues, but the responsibility of planning and implementing teaching arrangements is up to the municipalities. The current system should be fixed, but the means to address these issues are limited. (NaLR3)

The need for more coherent steering was mentioned by many participants. In Finland, teachers have strong autonomy, and it is highly appreciated (e.g. Soini, Pyhältö, and Pietarinen Citation2021). However, strong teacher autonomy may cause challenges in collaboration when renewing pedagogical solutions.

The participants mentioned challenges related to the decentralized basic education system in Finland because the municipalities form their own practices for supporting RAFLLs. At the exosystemic level, municipalities create their curricula based on the national core curriculum (FNBE, Citation2014). Support measures for RAFLLs are funded according to municipality-level policymaking and are organized according to the understanding of and resources available to each municipality’s school administration. This leads to a significant lack of continuous support structures, as noted by a national-level participant:

After the prep-ed, the student is pushed to mainstream education, often without adequate support. (NaLR2)

The need for resources enabling sustainablity. Organizing support requires resources that are often dependent on temporary funding. The teaching positions that depend on municipality decisions are not permanent. This is a challenge not only for long-term planning and teacher collaboration, but also for building meaningful and sustainable pedagogical relationships with RAFLLs. Changes in teaching staff members can be harmful:

The worst case is when, in autumn, the teachers are not the same ones we met at the end of the prep-ed together with the RAFLL. (TR8)

We have had relatively good resources for supporting RAFLLs, but the lack of clear structures forms an obstacle to planning ahead. It is difficult to plan the support structures because the resources for providing support vary annually. (TR3)

Organizing grassroots practices. The exosystemic municipality-level decisions related to support for RAFLLs include prep-ed arrangements, teacher resources, and teacher qualification requirements, as well as resources for FSLL and L1 instruction. This leads to a variety of solutions in the microsystem. The importance of flexible teaching groups was emphasized by the participants:

I believe that if intensified support is organized in small groups, it is more beneficial. I assume that it is more challenging to provide adequate support for RAFLLs who study in mainstream classes. (TR9)

To achieve sustainability, there must be a shared vision among stakeholders operating within and between the ecosystemic levels when developing support measures targeted at RAFLLs. Furthermore, in line with the findings of Soini, Pyhältö, and Pietarinen (Citation2021), the developmental processes concerning curriculum reform—in this case, curriculum-wide language awareness—require negotiation and interplay between actors at all ecosystemic levels. At the micro-and mesosystemic levels, the schools are dependent on exo-level municipality resources, but they are also responsible for providing RAFLLs with adequate support, as required by the macro-level policies.

Holistic linguistic responsiveness

According to the participants, the macro-level legislation should be updated to consider RAFLLs’ needs for linguistic support. Currently, the legislation (decree 1777/2009; Finlex, 2009) does not address language proficiency issues in relation to support measures or school subjects other than Finnish/Swedish as a second language and the teaching of students’ L1s (Finlex Citation2011). This requires macro- and exo-level attention, as pointed out by a national-level participant:

The support after prep-ed should be organized within mainstream education, not as separate groups. However, if funding for this is provided to the municipalities, we should be able to rely on the education providers to target the resources for RAFLL support. There are examples of FSLL resources that are not used for what they are meant for. We need a flexible form of additional support that reaches those who need it. (NaLR1)

Regardless of the participants’ systemic positioning, the structure of lower secondary education was considered challenging. In lower secondary education, non-language-related subjects are taught by subject teachers whose educational backgrounds frequently do not include content related to language education. Thus, LRT (Lucas and Villegas Citation2011, Citation2013) may seem irrelevant to teachers who have not participated in pre- or in-service courses covering linguistic topics.

There are teachers who pay tremendous attention to linguistic support, and there are teachers who are of the opinion that language-aware pedagogy is not their duty, or they just don’t know how to implement language-aware pedagogy for RAFLLs. (MLR3)

The importance of dedicated teachers for linguistic support. In Finland, all teachers are expected to support all students (FNBE, Citation2014), including RAFLLs. However, according to the participants, the implementation of support for RAFLLs at the microsystemic grassroots level needs further attention. As stated by one respondent, ‘If supporting RAFLLs is labeled as a ‘duty for all’, it easily becomes a responsibility of nobody’ (TR3). Consequently, in schools with a specific teacher resource for linguistic support, the responsibility of supporting RAFLLs is shared among subject (including FSLL) teachers, special education teachers, and teachers of linguistic support at the mesosystemic level. This was considered useful by the participants:

The support measures work well when there are teachers who are actually assigned to do that. (TR1)

Co-teaching is often implemented so that there is a teacher of linguistic support—a teacher of Finnish—who takes RAFLLs into a separate class where they can get more personalized support. We have also noticed that this arrangement has encouraged RAFLLs to be braver in speaking and asking questions. (TR13)

Supporting students’ L1s. The importance of L1 support for RAFLLs was recognized by the participants of this study. At the national level in Finland, the accessibility and availability of L1 instruction are problematic, varying between municipalities and even schools:

The schools don’t understand the importance of providing support in the students’ L1s. (MLP1)

Pedagogical leadership. As pointed out by a teacher participant (TR9), continuous teacher collaboration is needed to build sustainable support mechanisms for RAFLLs:

It is very important to understand that to create linguistically responsive support measures, teacher collaboration, student knowledge, and intensive planning are needed. All of this should be supported by the principals. (TR9)

RAFLLs’ needs for linguistic support. It was recognized by the participants that, independent of immigrant students’ other possible support needs, inadequate language skills can pose a challenge in all learning (see also Schleppegrell Citation2020). For many students, one year in prep-ed is not enough to learn sufficient Finnish for studying in general basic education, as pointed out by a teacher participant:

After the transition from prep-ed to mainstream basic education, the students need support for studying subject-specific content in the new language. (TR5)

Discussion

This study examined the current issues concerning support measures targeted at RAFLLs in Finnish lower secondary education. The theory-driven analysis was based on Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory (Citation1979, Citation1992/Citation2005). The findings offer insights to better understand the complex nature of and needs for developing support measures for language learners in new home countries.

This study indicates that the desire to develop sustainable teaching arrangements and support measures to better meet RAFLLs’ needs is strong. However, due to changes at the chronosystemic level, a growing number of RAFLLs at the microsystemic level has left the actors at the meso-, exo-, and macrolevels unable to respond adequately. The prevailing structures seem to align with the sink-or-swim approach (see Thorstensson Dávila, Citation2012). To some extent, the sink-or-swim approach can be considered a narrow view of inclusive education (Schwab, Sharma, and Loreman Citation2018). In the school context, teachers are the most important actors with regard to providing students with the support they need for learning. However, to learn, students need support from more experienced others (Vygotsky Citation1962). The sink-or-swim approach (Thorstensson Dávila Citation2012) can lead to students falling behind in the educational system and negatively impact their future ambitions and career choices (e.g. Borgna Citation2017).

With regard to inclusive pedagogy (Mäkinen and Mäkinen Citation2011), the notion of inclusion should not be viewed solely as a question of student placement (e.g. Göransson and Nilholm Citation2014). Instead, schools should be learning communities that offer flexible environments where all students have an equal right to belong to mainstream classrooms with their peers but are also given opportunities to participate in intensified individual or group-based support activities (see also Smythe Citation2022).

The participants’ responses were deeply connected to an LRA: the importance of language proficiency in becoming an active member of a new home country was acknowledged, and the challenges of learning a new language were recognized. Furthermore, the importance of valuing students’ L1s was emphasized. However, previous studies on linguistic diversity in the Finnish education system (e.g. Alisaari et al. Citation2019; Harju-Autti et al. Citation2021) have suggested that the linguistic barriers that RAFLLs encounter at school are not sufficiently recognized. The findings of the current study corroborate this insight. Indeed, while the need for linguistic support is acknowledged by the people who specialize in these topics, the actions to provide it are formed, according to the macrosystemic-level national steering documents, in local communities, thus on the exosystemic level, where an all-encompassing LRA has yet to be developed. Furthermore, support measures vary not only between municipalities at the exosystemic level, but also between schools at the meso- and microsystemic level, mainly because language-aware pedagogy (FNBE, Citation2014) is understood in different ways. Some teachers use a variety of sophisticated pedagogical strategies (see Cummins Citation2021) together with the principles of LRT, whereas others are reluctant to adopt the idea of language-aware pedagogy. This creates inequality in the linguistic support that RAFLLs receive in mainstream lower secondary education classes.

The findings also suggest that developing the education system according to and toward a holistic LRA is a lengthy process that should involve all ecosystemic levels, with an emphasis on a strong dialogue. The Finnish basic education system and its teaching arrangements, subjects, and structures were originally built and developed on monolingual ideologies. In addition, Finnish teacher education programs follow the principles of the basic education system by educating class teachers, subject teachers, and special education teachers separately, and courses covering CLD in teacher education are still limited (Szábo et al. Citation2021). Therefore, acknowledging changes at the chronosystemic level, it is crucial that teacher education is developed to provide teacher-students with adequate knowledge of linguistically and culturally responsive pedagogy (see also Vigren et al. Citation2022).

The findings support the notion that, at the macro level, the national steering documents for Finnish basic education do not form obstacles to providing support for RAFLLs. However, much of the local, exo-level decision-making does not include an LRA; for example, there is a paucity of specific knowledge regarding linguistic demands and needs for linguistic support. One crucial factor is, of course, money. Many steps toward culturally and linguistically responsive teaching have been taken at the macro level, such as pre- and in-service teacher projects funded by the Ministry of Education and Culture and the National Agency for Education. However, with project-based funding, continuity is not secured. Questions related to language proficiency should be included in all policy-making processes (e.g. Rodríguez-Izquierdo and Darmody Citation2019), requiring a holistic LRA from all actors on all ecosystemic levels. This could reduce the current tensions and further strengthen the dialogue between the levels.

As pointed out by the participants, subject-specific terminology is a language of its own (see also Schleppegrell Citation2020). In LRT, identifying the particular language demands of each discipline is vital (Lucas and Villegas Citation2011, Citation2013). Therefore, language-aware pedagogy is needed in all teaching—and from all teachers—independent of students’ linguistic backgrounds (FNBE, Citation2014). However, RAFLLs form a category of their own: learning the language of the surrounding community as the language of schooling at the same time as learning subject-specific content in the new language is demanding (Cummins Citation2021; Schleppegrell Citation2020). Everyone is a language learner throughout their lifetime, but on some occasions, targeted linguistic support is crucial (e.g. Koehler and Schneider Citation2019). To implement targeted linguistic support on the micro level following the principles of LRT (Lucas and Villegas Citation2011, Citation2013), coherent meso-, exo- and macro-level planning is required: it is necessary to build sustainable support measures based on sociolinguistic consciousness and an appreciation of linguistic diversity, as well as identification of language demands related to learning new topics through a new language.

The findings of this study indicate that the notion of inclusive education is interpreted in many ways. Our understanding of inclusive education is based on the EFA approach (UNESCO Citation2017). Thus, to develop inclusive practices that take linguistic diversity into consideration, finding new approaches for including recently arrived students in the education system is required (see also Erling, Gitschthaler, and Schwab Citation2022). Due to educational segregation (e.g. Hilt Citation2017; Rodríguez-Izquierdo, González Falcon, and Goenechea Permisán Citation2020), discussing the existing school structures is essential. It is noteworthy that, contrary to common belief, inclusive education is not equivalent to placing all students in the same classroom for every lesson. Instead, inclusion is about providing students with the support they need through various means (e.g. Schwab, Sharma, and Loreman Citation2018). To learn the language of schooling in a new home country, students should have the time and space to practice their language skills across the curriculum with dedicated teachers who, in line with LRT, are able to support students in building connections with their L1s, the language of schooling, and the subject content (e.g. Schleppegrell Citation2020).

Currently at the macro level, the government-funded Right to Learn development program aims to identify effective measures to strengthen support for learning and special needs and improve literacy in Finland (Ministry of Education and Culture Citation2019). Considering municipalities’ autonomy at the exosystemic level, macrosystemic national-level improvements are challenging to implement at the meso- and microsystemic levels. Furthermore, the importance of school-level leadership has been emphasized by Soini, Pyhältö, and Pietarinen (Citation2021), who found that school communities that learned from reforms were able to utilize the reforms as fuel for sustainable school development. However, as the number of RAFLLs continues to grow, the needed support measures require macrosystemic, national-level attention. Evidence has shown the necessity of developing support measures for RAFLLs (e.g. Kirjavainen and Pulkkinen Citation2017; Owal Group Citation2022), but concrete macrosystemic national-level actions, such as developing teachers’ qualification requirements, are needed. This study indicates that the expertise of linguistic support teachers is beneficial for organizing support for RAFLLs. This solution, however, has not yet been backed by any official guidelines in Finland. Subsequently, developing linguistic support requires national-level attention and adequate resources from exo- and macro-level decision-makers. Reaching sufficient academic proficiency in a new language takes several years (e.g. Schleppegrell Citation2020); thus, specific attention should be paid to supporting RAFLLs, with a focus on inclusive practices (e.g. Erling, Gitschthaler, and Schwab Citation2022).

Sustainable support measures need to be developed with consideration for all ecosystemic levels. Although this study has limitations related to generalizability as a result of the small sample in the context of a single country, it provides relevant insights for developing teaching practices in linguistically diverse contexts. Moreover, the validity of this study is strengthened by researcher triangulation. Cultural and linguistic diversity have expanded throughout Finland, but local-level decision-making at the exosystemic level, which is often based on short-term project funding, does not guarantee equal support for RAFLLs in Finnish basic education. Therefore, actions at the meso-, exo-, and macrosystemic levels should be further developed dialogically with an LRA to meet RAFLLs’ needs. Although teachers are responsible for implementing LRT in the classrooms (e.g. Zhang-Wu Citation2017), at the micro level, an LRA has to be adopted at all levels to find sustainable and pedagogically meaningful solutions that meet the needs of language learners around the world. Further research is needed to examine the role of school leadership in developing the overall school culture with an LRA.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahonen, A. K. 2021. “Finland: Success Through Equity—The Trajectories in PISA Performance.” In Improving a Country’s Education. PISA 2018 Results in 10 Countries, edited by N. Crato, 121–136. Springer.

- Ainscow, M. 2020. “Promoting Inclusion and Equity in Education: Lessons from International Experiences.” Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy 6 (1): 7–16. doi:10.1080/20020317.2020.1729587.

- Alisaari, J. 2020. “Case Study 5. Language Sensitive Curriculum and Focus on Language Awareness in Finland.” In The Future of Language Education in Europe: Case Studies of Innovative Practices, edited by E. Le Pichon-Vortsman, H. Siarova, and E. Szony, 78–85. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Alisaari, J., L. M. Heikkola, N. L. Commins, and E. O. Acquah. 2019. “Monolingual Ideologies Confronting Multilingual Realities. Finnish Teachers’ Beliefs About Linguistic Diversity.” Teaching and Teacher Education 80: 48–58. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2019.01.003.

- Association for Language Awareness. 2022. Language awareness defined. Retrieved April 12, 2022 from https://lexically.net/ala/la_defined.htm.

- Boblin, S. L., S. Ireland, H. Kirkpatrick, and K. Robertson. 2013. “Using Stake’s Qualitative Case Study Approach to Explore Implementation of Evidence-Based Practice.” Qualitative Health Research 23 (9): 1267–1275. doi:10.1177/1049732313502128.

- Borgna, C. 2017. Migrant Penalties in Educational Achievement. Second Generation Immigrants in Western Europe. Amsterdam University Press. eBook.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development. Experiments by Nature and Design. Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1992/2005. “Ecological Systems Theory.” In Making Human Beings Human. Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development, edited by U. Bronfenbrenner, 106–173. Sage.

- Bunar, N., and P. Juvonen. 2021. “‘Not (yet) Ready for the Mainstream’ – Newly Arrived Migrant Students in a Separate Educational Program.” Journal of Education Policy, 1–23. doi:10.1080/02680939.2021.1947527.

- Chu, W., H. Liu, and F. A. Fang. 2021. “A Tale of Three Excellent Chinese EFL Teachers: Unpacking Teacher Professional Qualities for Their Sustainable Career Trajectories from an Ecological Perspective.” Sustainability 13 (12): 6721. doi:10.3390/su13126721.

- Cummins, J. 2021. “Rethinking the Education of Multilingual Learners.” Multilingual Matters, doi:10.21832/CUMMIN3580.

- Erling, E. J., M. Gitschthaler, and S. Schwab. 2022. “Is Segregated Language Support fit for Purpose? Insights from German Language Support Classes in Austria.” European Journal of Educational Research 11 (1): 573–586. doi:10.12973/eu-jer.11.1.573.

- Finlex. 2011. Basic Education Act. 628/1998. Amendments up to 1136/2010. https://www.finlex.fi/en/laki/kaannokset/1998/en19980628.

- Finnish National Agency for Education. 2014. Perusopetuksen opetussuunnitelman perusteet [National core curriculum for basic education]. Accessed 14.4.2022. https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/perusopetuksen_opetussuunnitelman_perusteet_2014.pdf.

- Finnish National Agency for Education. 2015. Perusopetukseen valmistavan opetuksen opetussuunnitelman perusteet [National core curriculum for preparatory education]. Accessed 14.3.2022. https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/perusopetukseen_valmistavan_opetuksen_opetussuunnitelman_perusteet_2015.pdf.

- Finnish National Agency for Education. 2022. Suomi toisena kielenä -opetus. [Teaching Finnish as a second language and literature]. Accessed 14.3.2022. https://www.oph.fi/fi/koulutus-ja-tutkinnot/suomi-toisena-kielena-opetus.

- Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK. 2019. The ethical principles of research with human participants and ethical review in the human sciences in Finland. Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK. Accessed 1.3.2022. https://tenk.fi/en/advice-and-materials.

- Finnish National Institute for Health and Welfare. 2020. Education and language skills. Accessed 1.3.2022. https://thl.fi/en/web/migration-and-cultural-diversity/integration-and-inclusion/education-and-language-skills.

- Gitschthaler, M., J. Kast, R. Corazza, and S. Schwab. 2021. “Inclusion of Multilingual Students—Teachers’ Perceptions on Language Support Models.” International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1–20. doi:10.1080/13603116.2021.2011439.

- Göransson, K., and C. Nilholm. 2014. “Conceptual Diversities and Empirical Shortcomings – A Critical Analysis of Research on Inclusive Education.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 29 (3): 265–280. doi:10.1080/08856257.2014.933545.

- Guo-Brennan, L., and M. Guo-Brennan. 2021. “Leading Welcoming and Inclusive Schools for Newcomer Students: A Conceptual Framework.” Leadership and Policy in Schools 20 (1): 57–75. doi:10.1080/15700763.2020.1838554.

- Harju-Autti, R., M. Mäkinen, and K. Rättyä. 2021. “‘Things Should Be Explained So That The Students Understand Them': Adolescent Immigrant Students' Perspectives on Learning the Language of Schooling in Finland.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. Ahead-of-print. doi:10.1080/13670050.2021.1995696

- Harju-Luukkainen, H., and N. McElvany. 2018. “Immigrant Student Achievement and Education Policy in Finland.” In Immigrant Student Achievement and Education Policy. Cross Cultural Approaches, edited by L. Volante, D. Klinger, and O. Bilgili, 87–102.

- Heikkola, L. M., J. Alisaari, H. Vigren, and N. Commins. 2022. “Requirements Meet Reality: Finnish Teachers’ Practices in Linguistically Diverse Classrooms.” Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 1–17. doi:10.1080/15348458.2021.1991801.

- Hilt, L. T. 2017. “Education Without a Shared Language: Dynamics of Inclusion and Exclusion in Norwegian Introductory Classes for Newly Arrived Minority Language Students.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 21 (6): 585–601.

- Honko, M., S. Ahola, and T. Hirvelä. 2021. “Vironkielisten osallistujien kielitaito yleisten kielitutkintojen suomen kielen testissä.” Lähivõrdlusi. Lähivertailuja 31: 114–152. doi:10.5128/LV31.04.

- Horgan, D., S. Martin, J. O’Riordan, and R. Maier. 2021. “Supporting Languages: The Socio-Educational Integration of Migrant and Refugee Children and Young People.” Children & Society, 369–385. doi:10.1111/chso.12525.

- Hsieh, H.-F., and S. E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9): 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Hu, J., and X. A. Gao. 2021. “Understanding Subject Teachers’ Language-Related Pedagogical Practices in Content and Language Integrated Learning Classrooms.” Language Awareness 30 (1): 42–61. doi:10.1080/09658416.2020.1768265.

- Kirjavainen, T., and J. Pulkkinen. 2017. “Miten lähtömaa on yhteydessä maahanmuuttajataustaisten oppilaiden osaamiseen? Oppilaiden osaamiserot PISA 2012 –tutkimuksessa [The Effect of the Country of Origin and Student Performance. The Differences in PISA 2012].” Yhteiskuntapolitiikka 82 (4): 430–439.

- Koehler, C., and J. Schneider. 2019. “Young Refugees in Education: The Particular Challenges of School Systems in Europe.” Comparative Migration Studies 7 (28): 1–20. doi:10.1186/s40878-019-0129-3.

- Lopez, M. P. S. 2021. “Exploring Linguistically Responsive Teaching for English Learners in Rural, Elementary Classrooms: From Theory to Practice.” Language Teaching Research, 136216882110510–23. doi:10.1177/13621688211051035.

- Lucas, T., and A. M. Villegas. 2011. “A Framework for Preparing Linguistically Responsive Teachers.” In Teacher Preparation for Linguistically Diverse Classrooms: A Resource for Teacher Educators, edited by T. Lucas, 55–72. Routledge.

- Lucas, T., and A. M. Villegas. 2013. “Preparing Linguistically Responsive Teachers: Laying the Foundation in pre-Service Teacher Education.” Theory Into Practice 52 (2): 98–109. doi:10.1080/00405841.2013.770327.

- Mickan, P., K. Lucas, B. Davies, and M.-O. Lim. 2007. “Socialisation and Contestation in an ESL Class of Adolescent African Refugees.” Prospect 22 (2): 4–24.

- Miller, J. M. 2000. “Language use, Identity, and Social Interaction: Migrant Students in Australia.” Research on Language & Social Interaction 33 (1): 69–100. doi:10.1207/S15327973RLSI3301_3.

- Ministry of Education and Culture. 2019. The right to learn – An equal start on the learning path: Comprehensive school education programme for quality and equality 2020–2022. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-263-691-1.

- Ministry of Justice. 2022. Kielelliset oikeudet [Linguistic rights]. Accessed 10.4.2022. https://oikeusministerio.fi/kielelliset-oikeudet.

- Moate, J., L. Lempel, A. Palojärvi, and T. Kangasvieri. 2021. “Teacher Development Through Language-Related Innovation in a Decentralised Educational System.” Professional Development in Education, 1–16. doi:10.1080/19415257.2021.1902838.

- Mäkinen, M., and E. Mäkinen. 2011. “Teaching in Inclusive Setting: Towards Collaborative Scaffolding.” La Nouvelle Revue de l'Adaptation et de la Scolarisation 55 (3): 57–74.

- Nisbet, K., R. Bertram, C. Erlinghagen, A. Pieczykolan, and V. Kuperman. 2021. “Quantifying the Difference in Reading Fluency Between L1 and L2 Readers of English.” Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 407–434. doi:10.1017/S0272263121000279.

- Official Statistics of Finland. 2019. The largest groups by native language 2009 and 2019. Statistics Finland. http://www.stat.fi/til/vaerak/2019/vaerak_2019_2020-03-24_kuv_003_en.html.

- Official Statistics of Finland. 2021. Population according to language 1980–2020. Statistics Finland. http://www.stat.fi/til/vaerak/2020/vaerak_2020_2021-03-31_tau_002_en.html.

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2018. Programme for International Studies Assessment. PISA 2018 results. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/publications/pisa-2018-results.htm.

- Owal Group. 2022. Suomi/ruotsi toisena kielenä -opetuksen nykytilan arviointi [A review of the current state of teaching Finnish or Swedish as a second language]. https://okm.fi/-/suomi-ruotsi-toisena-kielena-opetuksen-nykytila-ja-kehittamistarpeet-selvitettiin.

- Pyykkö, R. 2017. Monikielisyys vahvuudeksi. Selvitys Suomen kielivarannon tilasta ja tasosta [Multilingualism into a strength. A report on languages and language reserve in Finland]. Ministry of Education and Culture. https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/160374/okm51.pdf.

- Rajakaltio, H., and M. Mäkinen. 2014. “The Finnish School in Cross-Pressures of Change.” European Journal of Curriculum Studies 1 (2): 133–140.

- Randell, E., and F. Osman. 2020. “Living in the Shadow of Political Decisions: Former Refugees’ Experiences of Supporting Newly Arrived Refugee Minors.” Journal of Refugee Studies 34 (4): 4121–4139. doi:10.1093/jrs/feaa096.

- Rodríguez-Izquierdo, R. M., and M. Darmody. 2019. “Policy and Practice in Language Support for Newly Arrived Migrant Children in Ireland and Spain.” British Journal of Educational Studies 67 (1): 41–57. doi:10.1080/00071005.2017.1417973.

- Rodríguez-Izquierdo, R. M., I. González Falcon, and C. Goenechea Permisán. 2020. “Teacher Beliefs and Approaches to Linguistic Diversity. Spanish as a Second Language in the Inclusion of Immigrant Students.” Teaching and Teacher Education 90: 103035–11. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2020.103035

- Salo, O.-P. 2009. “Dialogisuus Kielikasvatuksen Kehyksenä [A Dialogical Approach as a Framework for Language Education].” Puhe ja Kieli 29 (2): 89–102. https://journal.fi/pk/article/view/4788.

- Schleppegrell, M. 2020. “The Knowledge Base for Language Teaching: What is the English to be Taught as Content?” Language Teaching Research 24 (1): 17–27. doi:10.1177/1362168818777519.

- Schwab, S., U. Sharma, and T. Loreman. 2018. “Are we Included? Secondary Students' Perception of Inclusion Climate in Their Schools.” Teaching and Teacher Education 75: 31–39. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2018.05.016.

- Smythe, F. 2022. “School Inclusion, Young Migrants and Language. Success and Obstacles in Mainstream Learning in France and New Zealand.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, doi:10.1080/01434632.2022.2056189.

- Soini, T., K. Pyhältö, and J. Pietarinen. 2021. “Shared Sense-Making as key for Large Scale Curriculum Reform in Finland.” In Curriculum Making in Europe. Policy and Practice Within and Across Diverse Contexts, edited by M. Priestley, D. Alvunger, S. Philippou, and T. Soini, 247–271. Emerald.

- Stake, R. E. 1995. The art of Case Study Research. Sage.

- Sulkunen, S. 2013. “Adolescent Literacy in Europe – An Urgent Call for Action.” European Journal of Education 48 (4): 528–542. doi:10.1111/ejed.12052.

- Szábo, T. P., E. Repo, N. Kekki, and K. Skinnari. 2021. “Multilingualism in Finnish Teacher Education.” In Preparing Teachers to Work with Multilingual Learners, edited by M. Wernicke, S. Hammer, A. Hansen, and T. Schroedler, 58–81. x: Multilingual Matters. doi:10.21832/9781788926119-006

- Thorstensson Dávila, L. 2012. “‘For Them It's Sink or Swim’: Refugee Students and the Dynamics of Migration, and (Dis)Placement in School.” Power and Education 4 (2): 139–149. doi:10.2304/power.2012.4.2.139.

- UNESCO. 2017. A guide for ensuring inclusion and equity in education. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000261971.

- Van Lier, L. 2004. The Ecology and Semiotics of Language Learning. A Sociocultural Perspective. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Vigren, H., J. Alisaari, L. M. Heikkola, E. O. Acquah, and N. L. Commins. 2022. “Teaching Immigrant Students: Finnish Teachers’ Understandings and Attitudes.” Teaching and Teacher Education 114: 103689–12. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2022.103689.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1962. Thought and Language. The M.I.T. Press.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard University Press.

- Walton, E., S. Carrington, B. Saggers, C. Edwards, and W. Kimani. 2022. “What Matters in Learning Communities for Inclusive Education: A Cross-Case Analysis.” Professional Development in Education 48 (1): 134–148. doi:10.1080/19415257.2019.1689525.

- Woods, A. 2009. “LEARNING TO BE LITERATE: ISSUES OF PEDAGOGY FOR RECENTLY ARRIVED REFUGEE YOUTH IN AUSTRALIA.” Critical Inquiry in Language Studies 6 (1-2): 81–101. doi:10.1080/15427580802679468.

- Zhang-Wu, Q. 2017. “Culturally and Linguistically Responsive Teaching in Practice: A Case Study of a Fourth-Grade Mainstream Classroom Teacher.” Journal of Education 197 (1): 33–40. doi:10.1177/002205741719700105.