ABSTRACT

This article explores university students’ communicative competence for English-Medium Instruction (EMI) at a Swedish university in the era of digitalisation and blended learning. Based on a linguistic ethnography, we present an argument for communicative competence as repertoire assemblages orchestrating digital materiality and human language to construct meanings. The study shows how diverse digital multimodalities and AI-language tools are essential features of spatial repertoires for academic communication, and how they cooperate with and mediate students’ personal repertoires to accomplish interactive learning tasks in EMI contexts. The study also highlights how digital diversity in EMI causes a ‘digital divide’, potentially impacting power relations among students. These findings underline the importance of acknowledging the communicative value of digital materiality and negotiating difference and normativity for intercultural academic communication in EMI.

Introduction

The fusion of campus-based and online learning experiences, accelerated by advancements in digital technology and the broad implementation of blended learning schemes, has led to a rapid transformation of teaching and learning in higher education (Garrison and Vaughan Citation2008). University students today are immersed in a fluctuating and highly internationalised learning environment in which more and more university resources are made available digitally and an abundance of Internet resources and innovations can be accessed to facilitate learning. As a result, students need to develop communicative competence to deal with different forms of interaction (face-to-face, online or hybrid forms of communication) for the sake of achieving educational objectives. In addition to their linguistic repertoires, students also require the ability to decipher digital multiliteracy skills, intercultural and communicative strategies, and the ability to regulate multimodal resources (e.g. Al-Samarraie and Saeed Citation2018).

In the context of English-medium instruction (EMI) – ‘a [higher education] setting in which at least some participants have another L1 than English, but in which all are expected to use English for some instructional purposes […], and in which English is not taught but is nonetheless expected to be learned’ (Pecorari and Malmström Citation2018, 511) – research has extensively addressed the issue of language for teaching/learning, e.g. by problematising the ‘E’ in EMI as ‘standard’ English, a lingua franca, and by highlighting translingual and/or disciplinary literacy (cf. Kuteeva Citation2020). However, despite the extensive digitalisation of higher education, the conceptualisation of communicative competence in EMI remains largely linguistic-centric, leaving the role of non-linguistic resources (i.e. multimodalities, digital semiosis, objects) under-explored (see a few exceptions in Liu and Lin Citation2021; Ou and Gu Citation2022). This not only risks a limited understanding of communication without fully considering people’s semiotic repertoires (Kusters et al. Citation2017), but also overlooks the representational power of objects as agentive resources capable of affecting and reconfiguring human language to convey meanings (Canagarajah Citation2018a). Therefore, in this study we incorporate the value of materiality, i.e. objects and environmental affordances, in the understanding of language and call for a materialised and co-constructed view of communicative competence for EMI to better reflect students’ language use and the challenges they face in learning and intercultural communication in digitalised higher education.

Empirically, we present a linguistic ethnography that explores students’ beliefs about communicative competence and their communicative practices in academic activities at a Swedish EMI university committed to exploring the assumed affordances of blended learning and digitalisation of education. We treat the students’ communicative competence as an expanded construct beyond their (academic) English proficiency involving assemblages of resources from their blended learning contexts. We especially focus on the students’ engagement with digital technologies and multimodalities, as they provide affordances to their intercultural academic communication and learning experiences in EMI as well as complicate them. We are hopeful that the findings of this study will provide insights for the conceptual advancement of communicative competence in EMI. For EMI practice, the study has implications for international universities developing their language-in-education policies and language curricula to align with the new communication demands in the digital era of higher education.

Problematising communication in EMI in the digital era

The conceptualisation of communicative competence in EMI has largely focused on language, especially academic English. Given the considerable diversity of learners’ prior content knowledge, language backgrounds, and communication challenges in the global EMI learning context (e.g. Doiz, Lasagabaster, and Sierra Citation2012; Fenton-Smith, Humphreys, and Walkinshaw Citation2017), researchers contend that EMI should be implemented in a more language-conscious manner by combining EMI teaching with English for academic/specific purposes instruction (e.g. McKinley and Rose Citation2022; Schmidt-Unterberger Citation2018). Other researchers note how disciplinary literacy is central to EMI (e.g. Airey Citation2020; Malmström and Pecorari Citation2021), or recognise the benefits of multilingualism in supplementing English-medium teaching and learning (e.g. Baker and Hüttner Citation2017; Dafouz and Smit Citation2022). In a recent EMI-in-higher education policy discussion, Ou, Hult, and Gu (Citation2022) argued that language planning (i.e. corpus, status and acquisition planning) for EMI is interwoven with prestige planning – the value of English as symbolic capital – to elevate the international profiles of universities and students, for the former to make profits in the competitive global knowledge economy and the latter to succeed in the global labour market. Driven by this, the current conceptualisation of communicative competence in EMI more closely reflects the influence of English as a global language (cf. Phillipson Citation2009) than matches real-life communication practices.

Research has problematised this issue from several aspects. First, while the ‘E’ in many EMI policies and practices has been envisaged as the native-speakers’ English and language norms, a growing body of EMI classroom studies suggests successful communication for teaching, learning and daily interaction is often performed through a diverse use of English as a lingua franca (ELF) where communicative effectiveness is the norm (e.g. Jenkins Citation2017). Second, the monoglot ideology within many EMI policies – encouraging English as the only legitimate language for education – is at odds with teachers’ and students’ flexible multilingual practices for EMI teaching and learning (e.g. Jenkins and Mauranen Citation2019; Mortensen Citation2014; Ou, Gu, and Hult Citation2023). Additionally, researchers have increasingly considered the role of multimodal resources and pointed out the ‘lingua bias’ (Block Citation2014) in understandings of communication in EMI, which prioritises verbal communication (i.e. the use of spoken and written language – often English) but ignores the non-linguistic aspect of communication (Liu and Lin Citation2021).

Challenging linguistic centrism in EMI is more pertinent than ever due to the development of digitalisation and blended learning in higher education. Increasingly today, digital multimodalities are considered an essential component of EMI teaching and learning. A case in point is the study by Kohnke, Jarvis, and Ting (Citation2021) showing that the use of infographics could motivate peer interaction and facilitate the demonstration of discipline-specific English language skills. As is the work of Querol-Julián (Citation2021) about innovative online instructional technology, demonstrating how teachers use embodied modes and digital semiosis to improve students’ engagement in online lectures. Similarly, Ou and Gu (Citation2022) report that teachers and students employ videos, social networking applications and machine translation services to enable smooth EMI classroom interaction and learning. In another study of communication in online EMI learning, Ou, Gu, and Lee (Citation2022) highlight how digital multimodalities (e.g. visuals, audio and screen activities) are not merely supplementary to the students’ verbal communication, but are agentive communicative resources that can mediate students’ language use and reshape their performed language proficiency in EMI. These studies suggest an evolving view of digital multimodalities from treating them as part of the context of interaction and secondary to communication towards an integrated view of semiotic repertoires where digital technologies and objects play an agentive role in meaning-making, on a par with human cognition and language. Accordingly, as Hultgren et al. (Citation2022) point out, EMI settings should be recognised ‘more positively as environments in which a wide range of multimodal and multilingual resources can be mobilised and seen as strengths’ (p.107) and where ‘language proficiency cannot be meaningfully extracted from a fuller assemblage of meaning-making resources, co-constructed and negotiated by interactants’ (p.108). There is a clear need to move away from the English- and individual-centric view of ‘language proficiency’ to an emergent, co-constructed and materialised view of communicative competence for EMI learning, which takes better account of the affordances and challenges that digitalised EMI brings to academic communication today.

Materialising communicative competence: from translanguaging to repertoire assemblage

Recent theoretical advancements in translanguaging have provided a fluid view of language for communication, thus challenging English-only and linguistic-centric ideologies prevailing in EMI pedagogical practices and policies. Translanguaging, as explained by Li (Citation2018), postulates that the human mind is a holistic multi-competence by which people think beyond bounded language systems to use multilingual, multisensory and multimodal resources as an integrated whole for sense- and meaning-making. It foregrounds the act of ‘orchestration’ (Zhu, Li, and Jankowicz-Pytel Citation2020) that multilingual users coordinate and reciprocate each other’s embodied repertoires for meaningful interactions. Research from both campus-based and digitally-mediated EMI learning environments has shown that teachers and students orchestrate individuals’ semiotic repertoires, everyday discourses, and other community resources to maximise learning efficacy (e.g. Ho and Tai Citation2021; Lin Citation2019). From an empirical point of view, translanguaging appears useful in identifying semiotic resources to account for individuals’ full repertoire and their transformative power (cf. Li Citation2018). However, translanguaging remains individual-centric in its consideration of relationship between diverse semiotic resources, i.e. treating semiotic resources (multimodalities, bodies, objects) as essentially passive – mobilised by people – and secondary – supplementary to people – in communication. We thus join recent critical applied linguists’ calling for ‘a reconsideration of materialism, an insistence on embodiment, and reassessment of the significance of place’ (Pennycook Citation2018, 449), and argue for an expanded view of translanguaging by incorporating new materialism ontologies to better capture the dynamic relationship among different forms of semiosis in EMI students’ daily communicative practices.

Put simply, new materialism recognises the inherent vitality of matter – the material world people live in – and encourages us to see phenomena as polycentric systems shaped by both human and non-human agentic capacities (cf. Coole and Frost Citation2010). An application of it in linguistics is Canagarajah’s (Citation2018a; Citation2018b; Citation2021) spatial and materialist orientation to communication, which foregrounds the role of materiality (i.e. objects, artefacts, technologies, and tools, which have been traditionally regarded as part of the context of interaction) in communication. Specifically, Canagarajah regards materiality as linguistically generative, indexically powerful, and equally agentive as human cognition relates to human resources in a rhizomatic manner (without assumptions of hierarchy and cause–effect) in meaning-making (Canagarajah Citation2018b). This means that human agency—our mind and language—is not always decisive for the outcomes of communication; instead, meanings emerge during interactions, from diverse parties of people, social networks and the material world, and through distributed practice. For example, Canagarajah (Citation2018a) demonstrates how a South Korean scholar’s ‘academic English ability’ for publication is distributed across his knowledge and language, images, laboratory work, as well as his social networks (e.g. local or international collaborators, reviewers, consultants). Communication in this vein is embodied and materially shaped, with the meanings and values of each communicative resource negotiated and constructed in situ (Canagarajah Citation2021).

Consistent with this understanding of new materialism, communicative competence for EMI learning is better conceived from the perspective of repertoire assemblage, i.e. an emergent and relational collection of people, social networks, and materiality from both physical and virtual contexts of communication. The notion of ‘assemblage’ was coined by Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987) to denote a ‘concrete collections of heterogenous materials’ (Adkins Citation2015, 14) with an emphasis on combining the quality of stasis and change in understanding the property of a thing. It facilitates a constructive and performative (as opposed to deterministic) view of competence as an ever-changing performance of the interplay of all distributed human and non-human entities in the environment. In this sense, the outcomes of communication exceed individuals’ translanguaging practice and result from the interplay of language users’ personal repertoires and spatial repertoires: ‘the full range of semiotic resources that are part of an activity in a situated material and social environment’ (Canagarajah Citation2018a, 275). According to Canagarajah (Citation2021), spatial repertoire comprises both ‘substrate,’ immediate semiotic resources that are currently available in the setting for communicative purposes, and ‘sedimented’ semiotic resources, such as an ‘assembling artefact’ (Pennycook Citation2017), the meanings of which are conventionally used to shape communicative activities in similar settings.

In this study, we conceptualised EMI students’ communicative competence for learning as assemblages of their translanguaging practice—based on personal repertoires including academic English, other languages and multimodal resources—and spatial repertoires from the digitalised learning environments. By doing so, this study gives equal importance to verbal resources, multimodalities and objects in terms of their communicative values, and highlights the need to investigate the capability of materiality to mediate human agents in meaning-making. Our focus is on exploring how the digitalised learning environment can reconfigure EMI students’ academic communication practice and the communicative competence they need.

The study

Research context

The broader context for this study is digitalised EMI higher education in Sweden. Sweden is widely considered a front-runner in terms of digitalisation, including in the higher education sector (cf. Gaebel et al. Citation2021; Lauritzen Consulting, & Hoegenhaven Consulting Citation2020). According to the most recent Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI), Sweden ranked third in Europe, and the country report for Sweden highlights, e.g. how a significant proportion of the population has advanced digital skills, and how the digital maturity in the population, the public sector and companies is very high (DESI Citation2021). The implementation of EMI in Sweden has also come a long way (a situation mirrored in other Nordic countries) (Hultgren, Jensen, and Dimova Citation2015). A recent report from the Swedish Language Council (Malmström and Pecorari Citation2022) mapped the linguistic landscape of Swedish higher education and found that 64 percent of all advanced-level education programmes and 53 percent of all courses are offered in English. The proportion of EMI is significantly higher in some disciplines, most notably in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. It is therefore unsurprising that EMI plays a very prominent role at the university where this study is set, [withheld for reasons of blinding]. In 2021, 99 percent of the masters’ programmes at the university (all but one) had implemented EMI.

Sampling and data collection

For this article, the data were collected between September and December 2021, during a period when much education was delivered online or in a blended mode because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Adopting a snowball sampling approach, nineteen master’s level students enrolled in different EMI programmes and representing different ethnolinguistic and disciplinary backgrounds (see details in ) were recruited. The sample included five local Swedish students and fourteen international students; all are highly multilingual.

Table 1. Demographic information of the participants.

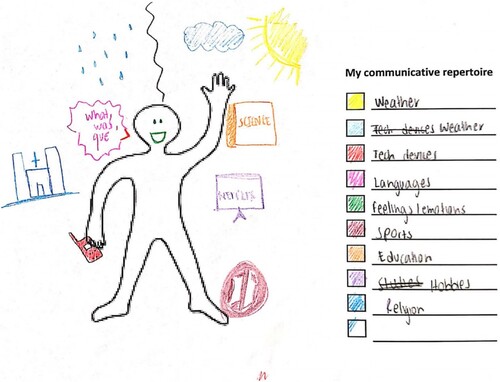

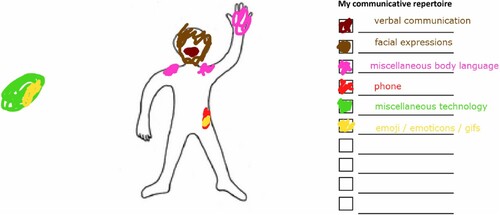

The volunteer participants were invited to a semi-structured individual interview that focused on their experiences and perceptions of intercultural academic communication in digitalised EMI higher education contexts. The interview started with a language portrait (Busch Citation2012), where participants were asked to illustrate their understanding of their communicative competence using both visual and verbal cues. Detailed instructions were provided, and relevant questions pertaining to the participants’ illustrations were asked afterwards. Each interview lasted approximately 40 min and was audio-recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriber. To protect the anonymity of the participants, all identifiable information was removed, and participant codes are used in the data presented.

Volunteer participants for observations (n = 5) were recruited from the group of student interviewees. Student interaction in connection with a group project (e.g. written, spoken, pictorial, emoticon-based, and video-based engagement) was observed in diverse channels (e.g. videoconferences, messages on social networking applications, and face-to-face meetings). It should be noted that the different forms of communication observed were at the discretion of the participants and their group mates. Most of the video recordings of online meetings and pictorial recordings (screenshots) of social networking messages were made by the participants themselves, and then shared with the researchers (enabling asynchronous observation). Participants were encouraged to delete information they preferred not to be published. All physical/hybrid-mode meetings in person were observed on-site and video recorded. Field notes were taken during the observations, and relevant texts and learning materials were collected. For this article, we only drew on a limited amount of observational data involving P4.

Data analysis

Informed by new materialism, our analytical approach moves away from ‘methodological individualism’ (Canagarajah Citation2021) – analysing individual repertoires such as what people possess, prepare for, or lack in grammar – to focus on the analysis of repertoire assemblage; that is, the process by which all available communicative resources (linguistic and non-linguistic, human and non-human) from the social and material environment where the student is embedded work together and influence each other to allow the student to communicate and carry out the task in hand. More specifically, we focus on ‘the consequence of object’ (Pennycook Citation2017, 277), exploring how digital multimodalities from the examined EMI context mediate and reconfigure students’ language use and the potential outcomes such human-non-human interaction bring to academic communication and learning. Accordingly, we use activity as the unit of analysis (Canagarajah Citation2018c), drawing attention to the interactional dynamics among all resources for the purpose of accomplishing a social task in EMI learning, such as an assignment or meeting.

Following the tradition of linguistic ethnography research, multiple sources of data were analysed in an integrated manner, with balanced attention and linked to each other to address the ethnographic complexity (Copland and Creese Citation2015). All the collected data were imported into NVivo 12 for data storage, classification, and initial analysis. The interview data and language portraits were coded thematically, in a primary inductive and recursive approach, in tandem with additional data collection. A multimodal discourse analysis approach (Mondada Citation2016) was used in analysing the observational and audio-recorded interaction data to ensure that the examination of all dimensions of embodiment worked together without favouring one form of semiotic resource over another. Finally, we adopted ethnographic writing principles in relation to our findings, using ‘thick descriptions’ (Geertz Citation2000) to provide a comprehensive and contextualised interpretation of the data as it was co-constructed by the participants and researchers.

Findings and discussion

In this section, we report on and discuss three emerging themes related to university students’ communicative practices in digitally framed EMI activities: (i) an expanded spatial repertoire for EMI learning constituted by digital materiality; (ii) communicative competence based on assemblages of personal and spatial repertoires for a group assignment; and (iii) problems associated with digital diversity, particularly asymmetrical power relations between students.

Digital materiality as spatial repertoire for EMI learning

The materialist view of communication brings to the fore the distributed non-linguistic resources in the digital learning environment of EMI as part of students’ communicative competence. As shown in , the data reveal that academic communication in EMI today is carried out in an expansive space incorporating a large variety of digital communication channels (e.g. online collaboration/project management platforms, social networking applications, and e-conferencing tools) with different ‘cultures’ of communication, i.e. supported modalities, embedded semiotic resources, layout, organisation and storage of information. Apart from Zoom and Canvas, two digital communication channels mandated by the university, the participants were free to choose and combine multiple digital channels to communicate and accomplish individual/group learning activities. Such digital diversity at the group level allowed for an expanded spatial repertoire, resulting in enhanced academic communication. Our observation indicated that communication on digital platforms involved a combination of text-based/voice-based messages generated by the students as well as texts generated by AI and algorithm-based technology. We found that the latter significantly impacted the EMI students’ communicative competence as it was performed in various learning contexts such as essays, reading assignments, and lectures.

Table 2. The most frequently reported digital communication channels.Footnote4

Different kinds of AI-language tools were highlighted as crucial components of the spatial repertoire for digitalised EMI learning and interaction. For instance, some participants (P2, P12, and P13) suggested that their academic English competence for processing EMI lectures was extended when attending online learning because of the availability of AI-generated scripts and subtitles in the video lecture environment. Like an additional cognitive organ outside the human body, this technology of automated written-language generation that is synchronised with the speaker’s utterances enables people to process acoustic information through both listening and reading. When students attended an online lecture, the AI-script generator supported an emergent ‘reading ability’ that mediated students’ methods of processing lecture information and, together with the student’s individual repertoire, constituted the needed academic English competence for learning in EMI lectures.

Similarly, Text-and-Speech, an algorithm-based technology converting written texts into spoken words, was reported by P19 as being frequently used for listening to assigned readings and scientific research articles, enabling more effective study since he can do the ‘reading’ in contexts where high-level dedication and concentration are not required (e.g. on public transportation). As a result, AI-technologies not only enhance EMI learning through the use of multiple senses, but they also, more importantly, ‘materialise’ (Canagarajah Citation2018a) students’ communicative competence. In other words, students gain an additional ability to engage in academic communication, such as reading scientific articles in P19’s case, through AI-based language tools.

Moreover, AI text editors (e.g. Grammarly) and e-translators/dictionaries (e.g. Google Translate) were also extensively used by the participants when writing academic English:

P9 (Y1, Mexico): At the beginning, I was a little insecure about my level of writing, because I didn’t know if the sentence had logic or something like that. For writing essays or reports, I use Grammarly.

Researcher: In what way do you find it useful?

P9: Like checking the types, yeah, or like using fewer words, or if I want to find a synonym, it’s pretty easy to change a word and not repeat.

P15 (Y2, Sweden): I tend to use Google Translate a lot when I’m writing to someone, and I want to write a word that truly expresses what I mean. I get the impression that I’m usually misunderstood because I don’t speak (English) a lot, so I have to find just a specific word that I have in mind, and there I use Google translate. If I find the word to be something I do not want to use, I use synonyms.

P18 (Y2, Sudan): Oh, yeah, I use Grammarly. I use it to check assignments, like after I write my part, to just check if there are obvious mistakes that need to be changed.

Our analysis of the participants’ language portraits – their interpretations of communicative competence for EMI – is consistent with their reported use of multimodal and digital communicative resources. As demonstrated by P11 and P15’s language portraits ( and ), the participants identified digital and high-tech devices – objects that are outside human cognition – as significant components of their communicative repertoire (as reflected by frequent references to ‘phone’, ‘miscellaneous technology’, ‘typing’, ‘social media’, ‘online chats’, ‘smartwatch’, etc.). This digital generation of university students has a ‘translanguaging instinct’ (Li Citation2018, 24), an innate capability with which these language users not only spontaneously think beyond a narrowly defined language system and incorporate a full range of linguistic and semiotic resources for effective communication, but also acknowledge digital materiality as agentive communicative resources. When engaged in EMI learning activities, their communication is never confined to the English language, or the academic English genre; rather, consciously or not, they align with all kinds of linguistic resources, semiotics and objects in both physical and digital learning environments to create meaning. There is therefore a need for contemporary international higher education to adapt their conceptualisation of academic communication competence to align with students’ language practices and beliefs. Relevant guidance should be provided to support effective use of material and spatial resources for learning.

Minutes as assemblages of distributed practices

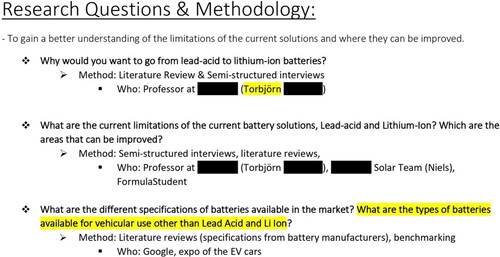

This section draws on an in-depth analysis of communication taking place during a group meeting involving P4 and five other group members (pseudonyms ‘G1’- ‘G5’) – four local Swedish students (G2–5) and an international student (G1); it briefly illustrates the multilingual, material and distributed nature of academic communicative competence in digitalised and internationalised higher education. The group worked on a product development project to help a local Swedish company to develop an industry solution. The results should be delivered through group presentations and a written research report. The focal meeting occurred on the morning of November 22, 2021, lasting 3 hours, and it was conducted in a hybrid form, with G4 and G5 joining virtually via Teams on G1's screen. The aim of this meeting was to draft research questions and discuss data collection methods. During the meeting, all members were also connected online on Google Docs, where they created and synchronously co-edited a document named ‘meeting20211122’ to record the outcomes of their discussion. Finally, this meeting generated three pages of minutes containing a list of research questions and their corresponding research methods.

shows an extract from the minutes. The document, most of which would be modified and included in their final assignment submission, was written in English. However, our analysis of the repertoire assemblages that shaped this text during the meeting activity shows contributions from a miscellaneous collection of semiotic resources distributed in people, social networks, as well as the virtual material world where the group was situated. In this section, we illustrate this with two cases (highlighted in yellow in ).

First, ‘Torbjörn’. This Swedish word was recorded by G1 (an international student who does not know Swedish) as the name of a professor whom the group believed to be a potential interviewee. As shown in Excerpt 1, the word emerged from a conversation starting with G2 providing the idea of consulting a professor who taught lithium-ion courses (1–3), then the name was uttered by G3, who read it from the course website (4–6). While whiteboarding the data collection plan, G1 tried to write the name but met difficulty spelling the word (9). As G1 asked for help, G2 instructed him of the spelling with an embodied ‘teaching’ of the semantic meanings of the words ‘tor’ and ‘björn’ (10–19). Based on this, P4 googled ‘bear in thor couture’ and presented several fun digital images he found to G2 and others (20–25). Then the group turned to a short discussion regarding the consent form, after which G1 sat down and typed the word Torbjörn correctly in the Google Document (29).

Excerpt 1.Footnote1

Table

The excerpt shows how the ‘language ability’ to type the Swedish word in the document was based on collaboration and interaction between different students’ linguistic repertoires, content knowledge, and materiality from the physical and digital spaces of the meeting. It is notable how G1 engaged in a Swedish language learning process during the conversation, where the pronunciation, spelling, and semantic meanings of the word were acquired through an assemblage of linguistic, body, object, and digital material resources. The assemblage includes: (i) G2’s content knowledge that constitutes the deictic meaning of the word (i.e. the name of a potential participant of the study project); (ii) the university webpage that provides the word form, which was made relevant by G3 through his pronunciation; (iii) a configuration of G2’s Swedish, English and body movements, G1’s whiteboarding act, P4’s use of English, and the digital images online, which work together to allow G1 to remember and consolidate his spelling and meaning of the word. None of the aforementioned resources alone would have enabled G1’s evident Swedish ability shown in the minutes. It was the orchestration – the interplay and effective collaboration – of the students’ personal repertoires (multilingual and multimodal resources) and the spatial repertoires (digital materials and whiteboards) that made it possible.

The second case is the question, ‘What are the types of batteries available for vehicular use other than Lead Acid and Li lon?’, which was typed by P4. As was shown in Excerpt 2, the formulation of this sentence drew on the collaborative thinking and English competence of P4, G1 as well as the Internet, which assembled during the conversation: It starts with P4 bringing up the idea by referring to an example (lithium-polymer batteries) shown on an automobile expo webpage (ecarexpo.se) (1–4). Using the mouse cursor to highlight the webpage contents and using the pronoun ‘they’ (3), P4 indexed distance influences from the virtual world – language and thoughts of the webpage builder or communicator of a battery/automobile company who created the message – in the immediate context of the group discussion. Following G2’s positive response, P4 started typing the question in the Google Document while G2 continued elaborating on the idea (5–11); part of G2’s utterance (7) became components of the final sentence P4 typed down.

Excerpt 2.

Table

It should also be emphasised that an AI-language tool, Google Translate, played a significant communicative role here. The ecarexpo webpage contents were only available in Swedish and it would have been unintelligible to P4, a Swedish language beginner. But, as shows, P4 skilfully utilised the ‘translate the page’ function (on the top-right of the webpage) provided by the web-browser (Chrome), which automatically converted all contents on the website into readable English. P4’s competence to read these Swedish texts was thus enabled by his strategic orchestration of his own English language (and reading skills) and the digital technology.

Digital diversity and digital inequality

Despite the increased digital diversity in international higher education, students’ approaches to digital resources is best described as laissez-faire. To this end, divergent views emerged when students in our sample referenced diverse individual prior experiences of digital communication, learning and working. In a participant’s words, digital diversity in EMI means, ‘it becomes increasingly complex to deal with multiple channels and people’s attitudes to channels’ (P19).

Our analysis strongly suggested that students’ preferences and choices of digital resources translated into an asymmetrical power relationship between different groups of students; specifically, this led to a devaluation of the international students’ norms of communication in intercultural groupwork and intercultural relationships in general. The interviews revealed a much-divided view regarding the use of online collaboration platforms, and international students tended to conform to the local Swedish students’ norm, sometimes causing major tension for intercultural groupwork. For example, P10 shared a personal anecdote of working on MATLAB with a Swedish peer:

P10 (Y1, India): In my last project, it was me, one of my Indian friends, and a Swedish guy. We were working on software that we don’t use that much in India, MATLAB. But here in Sweden, they use it a lot. So, [the Swedish student] was doing a lot of the heavy work, and even though we wanted to help, we didn’t have that much time to learn the whole software by ourselves and to help. Initially, he was okay with it, but then we got a stern message a week before submission: ‘Okay, I’ve had enough. I want you guys to sit and write the report. I’m not going to write the report at all, I feel I’ve already done this part.’ Then he went to the professor, and he was like: ‘I don’t want to work with these two girls.’ He changed the team. Yeah, that was … I think that was one of those moments when I was like: ‘Did I make the right decision to come to Sweden?’

Students reported that there was usually no negotiation regarding communication norms between students, indicating that international students frequently yield to an ‘order of indexicality’ (Blommaert Citation2007) regarding the use of digital resources; the local Swedish students’ normativity of semiosis is viewed as more legitimate compared to the international students’. This ideology could be problematic because it puts the international students in a disadvantaged position with respect to academic communication competence: deviations from the local norms of academic communication using digital resources could create practical problems for the group as a whole.

The unquestioned order of indexicality of digital resources and the ensuing consequences – digital inequality – are very clearly illustrated by these two responses from an international student and a Swedish student respectively:

P1 (Y1, Sweden): All communication is within Slack … I’m just trying to push them to get it working on the phone because it does work if you do each step correctly. The thing is that sometimes some members don’t even see important messages until a couple of days later, and those are the people I’m trying to push to improve their communication … not skills, but I just feel if you’re doing group work, you need to be attentive. You can’t be just like: ‘No, I don’t like it. I will do everything on my own.’

P16 (Y2, Chinese): I don’t like Slack, especially the web version. The log-in process and finding the discussion channel take a long time. Browsing chat history is also difficult. In addition, the notification setting sometimes prevents you from receiving notifications when other people message you. For group projects, I often suggested using WhatsApp to establish a group, but the Swedish students do not use WhatsApp. They prefer Slack. So I have to [emphasis added] use Slack even though it doesn't appeal to me.

What emerges from the above extracts is a ‘blame game’ played in the discordance regarding the use of digital resources. Adopting an ethnocentric view, the Swedish student was blind to the international students’ norms of digital communication and regarded Slack – the digital tool more familiar to students from Sweden and North America (e.g. P5) – as the only channel of communication. Seeing no alternatives, P1 unconsciously exerted power over his international peers during the groupwork: he first translated the international students’ divergent view of using digital resources into a bad attitude to groupwork (i.e. a free-rider mentality) and communicative incompetence. Based on this biased assumption, he further urged the international students to ‘improve’ their communication skills by getting themselves familiar with Slack. Meanwhile, the international students surrendered to the perceived power relationship between the local and the international. Similarly, without a critical evaluation of the symbolic power of different digital resources and negotiation of difference, the international participant (P16) felt obliged to adhere to the local Swedish student’s norm while blaming her Swedish partners for not proactively accommodating the international students’ norms of communication.

The above examples illustrate the lack of awareness of interculturality among university students when they are faced with an evolving international education context. Students would benefit from improved knowledge regarding the diversity of digital resources used in international higher education (shaped by prior academic experiences). Increased awareness (from all stakeholders) of the importance of negotiation of communicative norms – and empathy – would also enhance intercultural communication further.

Concluding remarks

This study has explored students’ experiences of academic communication as they engaged with digital technologies and blended learning in a Swedish EMI university setting. Based on the data analysis, we argue that communicative competence for EMI learning should be conceptualised beyond linguistic-centrism and human-centrism, as repertoire assemblages that orchestrate digital materiality and human language to construct meanings. EMI students’ academic communication is rarely (if ever) only attributable to an individual’s English language development. Even though many learning outcomes are presented in the academic register of English, the communicative competence that enables students to complete learning activities does not rely on (accumulating) individual students’ advanced-level knowledge of the language. Rather, it draws upon distributed practices from all parties of the social and material ecology of the activity, including all participants’ thinking, languages and bodies, as well as non-human resources, especially digital materiality such as AI-language tools, third-party contents, and digital multimodalities, which become integral to the spatial repertoire to facilitate situated communication.

It is noteworthy that the spatial repertoire is not subordinate to human cognition or supplementary to language in communication. As the multimodal discourse analysis illustrated, the boundary between human cognition and objects is blurred, and digital technologies like AI-language tools have ‘immanent modes of self-transformation’ (Coole and Frost Citation2010, 9) that could reshape a student’s thinking and the languages one was able to perform. They are as agentive as the human mind in meaning-making, and work together with students’ personal repertoires as an assemblage to shape the way that academic communication takes place in a learning activity. Our study thus contributes to the literature on digital multimodalities in EMI (e.g. Ho and Tai Citation2021) with an agentive view of digital semiosis and technologies: digital materiality is not a passive background/platform where students employ multilingual and multimodal resources for embodied learning, but self-creative entities that can generate impact on human bodies and an essential part of semiotic repertoires that enable communication.

The study has demonstrated that research of language and communication in EMI can benefit from an expanded focus of analysis to investigate repertoire assemblage – the dynamic relationship of all semiotic resources, people, and space – rather than focusing on individual persons or communicative resources (e.g. a language variety). By adopting a materialist view of translanguaging, our analysis looked beyond individual repertoires and brought the ‘context’ of communication to the fore to account for the powerful communicative roles played by objects. This has helped us capture the possibility of people’s language development occurring in a rhizomatic manner (Canagarajah Citation2018a), from diverse directions such as digital technologies and one’s social network, as demonstrated by G1’s Swedish learning during the group meeting.

Furthermore, decentralising human cognition as the primary source of language has developed our understanding of orchestration (Zhu, Li, and Jankowicz-Pytel Citation2020) by incorporating material agency and the unpredictable consequences of that. If, as our findings suggest, meanings are never created by singular individual or object but by intersubjectivity and interaction of distributed resources, what human participants can do to maximise communicative efficacy should be more than interpersonal reciprocation of each other’s repertoires and involve the strategic configuration of human and non-human resources. As P4’s case shows, this is a physical activity by which language users situate themselves properly in the material ecology of communication, identify potential spatial repertoires, and align individual thinking with relevant resources for meaning-making. Moreover, given the digital diversity and social inequality it has generated, orchestrating communication in the digital era should also acknowledge the sociolinguistics of materiality. One should note that, like human language, material resources are not equally evaluated from the point of view of relevance and indexicality. In our study, this appeared to be associated with ‘intercultural difference,’ since students from diverse backgrounds were socialised into different material environments of communication where one digital resource was preferred over another for a certain activity. This thus forms a translocal space in internationalised education contexts (Ou and Gu Citation2020), in which heteroglossia of spatial repertoire exists and thus requires people to orchestrate by negotiating meanings and relevance of materiality and to co-construct norms for communication.

The study has several practical implications. It is important to note that the generative assemblages facilitating students’ academic communication in this study were not unique to this specific EMI context, but rather a product of the increasing digitalisation of higher education. It was the expansion of digital and AI sources of language in today’s university students’ learning environments that allowed for the expanded spatial repertoires for academic communication. This constructive effect of digitalisation on academic communication should be recognised by all forms of higher education, including EMI. Therefore, in EMI, it is insufficient (and perhaps astray) to cultivate and assess students’ communicative competence only by focusing on individuals’ (academic) English skills. EMI initiatives in today’s academic society must acknowledge the communicative value of digital multimodalities, not only for the purposes of facilitating interaction but also for mediating and constituting students’ language. Besides English for academic/specific purposes curricula, EMI programmes can also adopt a ‘Language+’ curriculum to cater to the more tangible needs of students to (i) identify and recognise the value of the rich communicative resources embedded in their blended learning environments, and (ii) develop the ability to navigate and orchestrate all forms of resources (verbal/non-verbal, human/non-human) for effective communication.

While the digitalisation of higher education has provided a plethora of digital resources constituting individual students’ academic communication competence, our analysis has shown that there was a lack of consistency in students’ application of these resources in real-life learning activities. The students’ use of digital resources was largely self-regulated and unaided. Without the ‘know-what’ (i.e. differences in the prior knowledge of digital tools among students from diverse backgrounds) and the ‘know-how’ (i.e. the necessity and strategy to negotiate difference), digital diversity in EMI could provoke intercultural miscommunication and digital inequality that unwarrantedly devalue the communicative competence of some groups of students. Pragmatically, international universities are facing challenges in updating their language-in-education policies and language curricula to address new demands on communication and group dynamics in digitalised and blended learning. EMI university students today need clear direction and support regarding what digital resources to use, how to use them, and equally importantly, the cultivation of savoir être (Byram Citation1997), i.e. intercultural open-mindedness and readiness to suspend disbelief about others’ norms for a more equal and constructive intercultural relationship in communication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The transcription conventions follow Ou and Gu (Citation2022).

2 Information retrieved (and adapted) from Wikipedia.

3 Approximate figures retrieved from Statista.com or the (parent) company’s own public information.

4 See a descriptive overview of these channels in the Appendix.

References

- Adkins, B. 2015. Deleuze and Guattari's A Thousand Plateaus: A Critical Introduction and Guide. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Airey, J. 2020. “The Content Lecturer and English-Medium Instruction (EMI): Epilogue to the Special Issue on EMI in Higher Education.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 23 (3): 340–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2020.1732290

- Al-Samarraie, H., and N. Saeed. 2018. “A Systematic Review of Cloud Computing Tools for Collaborative Learning: Opportunities and Challenges to the Blended-Learning Environment.” Computers Education 124: 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.05.016

- Baker, W., and J. Hüttner. 2017. “English and More: A Multisite Study of Roles and Conceptualisations of Language in English Medium Multilingual Universities from Europe to Asia.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 38 (6): 501–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2016.1207183

- Block, D. 2014. “Moving Beyond “Lingualism”: Multilingual Embodiment and Multimodality in SLA.” In The Multilingual Turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL, and Bilingual Education, edited by S. May, 64–87. New York: Routledge.

- Blommaert, J. 2007. “Sociolinguistics and Discourse Analysis: Orders of Indexicality and Polycentricity.” Journal of Multicultural Discourses 2 (2): 115–130. https://doi.org/10.2167/md089.0

- Busch, B. 2012. “The Linguistic Repertoire Revisited.” Applied Linguistics 33 (5): 503–523. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/ams056

- Byram, M. 1997. Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Canagarajah, S. 2018a. “Materializing ‘Competence’: Perspectives from International STEM Scholars.” The Modern Language Journal 102 (2): 268–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12464

- Canagarajah, S. 2018b. “Translingual Practice as Spatial Repertoires: Expanding the Paradigm Beyond Structuralist Orientations.” Applied Linguistics 39 (1): 31–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx041

- Canagarajah, S. 2018c. “The Unit and Focus of Analysis in Lingua Franca English Interactions: In Search of a Method.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 21 (7): 805–824. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1474850

- Canagarajah, S. 2021. “Materialising Semiotic Repertoires: Challenges in the Interactional Analysis of Multilingual Communication.” International Journal of Multilingualism 18 (2): 206–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2021.1877293

- Clark, A. 2008. Supersizing the Mind: Embodiment, Action, and Cognitive Extension. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Coole, D., and S. Frost. 2010. New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Copland, F., and A. Creese. 2015. Linguistic Ethnography: Collecting, Analysing and Presenting Data. London: Sage.

- Dafouz, E., and U. Smit. 2022. “Towards Multilingualism in English-Medium Higher Education: A Student Perspective.” Journal of English-Medium Instruction 1 (1): 29–47. https://doi.org/10.1075/jemi.21018.daf

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- DESI. 2021. Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 2021 - Sweden. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/countries-digitisation-performance.

- Doiz, A., D. Lasagabaster, and J. M. Sierra. 2012. English-medium Instruction at Universities: Global Challenges. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Fenton-Smith, B., P. Humphreys, and I. Walkinshaw. 2017. English Medium Instruction in Higher Education in Asia-Pacific. Cham: Springer.

- Gaebel, M., T. Zhang, H. Stoeber, and A. J. G. Morrisroe. 2021. Digitally Enhanced Learning and Teaching in European Higher Education Institutions. Geneva, Switzerland: European University Association absl.

- Garrison, D. R., and N. D. Vaughan. 2008. Blended Learning in Higher Education: Framework, Principles, and Guidelines. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons.

- Geertz, C. 2000. “Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture.” In The Interpretation of Cultures, edited by C. Geertz, 581–612. New York: Basic Books.

- Ho, W. Y. J., and K. W. Tai. 2021. “Translanguaging in Digital Learning: The Making of Translanguaging Spaces in Online English Teaching Videos.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2021.2001427

- Hultgren, A. K., C. Jensen, and S. Dimova. 2015. “English-medium Instruction in European Higher Education: From the North to the South.” In English-Medium Instruction in European Higher Education. Vol. 3, edited by S. Dimova, A. K. Hultgren, and C. Jensen, 1–16. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

- Hultgren, A. K., N. Owen, P. Shrestha, M. Kuteeva, and Š Mežek. 2022. “Assessment and English as a Medium of Instruction: Challenges and Opportunities.” Journal of English-Medium Instruction 1 (1): 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1075/jemi.21019.hul

- Jenkins, J. 2017. “Mobility and English Language Policies and Practices in Higher Education.” In The Routledge Handbook of Migration and Language, edited by S. Canagarajah, 502–518. London: Routledge.

- Jenkins, J., and A. Mauranen. 2019. Linguistic Diversity on the EMI Campus: Insider Accounts of the Use of English and Other Languages in Universities Within Asia, Australia, and Europe. London: Routledge.

- Kohnke, L., A. Jarvis, and A. Ting. 2021. “Digital Multimodal Composing as Authentic Assessment in Discipline-Specific English Courses: Insights from ESP Learners.” TESOL Journal 12 (3): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.600

- Kusters, A., M. Spotti, R. Swanwick, and E. Tapio. 2017. “Beyond Languages, Beyond Modalities: Transforming the Study of Semiotic Repertoires.” International Journal of Multilingualism 14 (3): 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2017.1321651

- Kuteeva, M. 2020. “Revisiting the ‘E’in EMI: Students’ Perceptions of Standard English, Lingua Franca and Translingual Practices.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 23 (3): 287–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2019.1637395

- Lauritzen Consulting, & Hoegenhaven Consulting. 2020. Digitalisering og højere uddannelse i Norden. https://doi.org/10.6027/temanord2020-525.

- Li, W. 2018. “Translanguaging as a Practical Theory of Language.” Applied Linguistics 39 (1): 9–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx039

- Lin, A. M. 2019. “Theories of Trans/Languaging and Trans-Semiotizing: Implications for Content-Based Education Classrooms.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 22 (1): 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1515175

- Liu, J. E., and A. M. Lin. 2021. “(Re)Conceptualizing “Language” in CLIL: Multimodality, Translanguaging and Trans-Semiotizing in CLIL.” AILA Review 34 (2): 240–261. https://doi.org/10.1075/aila.21002.liu

- Malmström, H., and D. Pecorari. 2021. “Epilogue: Disciplinary Literacies as a Nexus for Content and Language Teacher Practice.” In Language Use in English-Medium Instruction at University, edited by D. Lasagabaster and A. Doiz, 213–221. New York: Routledge.

- Malmström, H., and D. Pecorari. 2022. Språkval och internationalisering: svenskans och engelskans roll inom forskning och högre utbildning. [Language Choice and Internationalisation: The Roles of Swedish and English in Research and Higher Education]. Stockholm: Språkrådet [The Swedish Language Council].

- McKinley, J., and H. Rose. 2022. “English Language Teaching and English-Medium Instruction: Putting Research Into Practice.” Journal of English-Medium Instruction 1 (1): 85–104. https://doi.org/10.1075/jemi.21026.mck

- Mondada, L. 2016. “Multimodal Resources and the Organization of Social Interaction.” In Verbal Communication, edited by A. Rocci, and L. Saussure, 329–350. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

- Mortensen, J. 2014. “Language Policy from Below: Language Choice in Student Project Groups in a Multilingual University Setting.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 35 (4): 425–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2013.874438

- Ou, A. W., and M. M. Gu. 2020. “Negotiating Language use and Norms in Intercultural Communication: Multilingual University Students’ Scaling Practices in Translocal Space.” Linguistics and Education 57: 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2020.100818.

- Ou, A. W., and M. M. Gu. 2022. “Competence Beyond Language: Translanguaging and Spatial Repertoire in Teacher-Student Interaction in a Music Classroom in an International Chinese University.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 25 (8): 2741–2758. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2021.1949261

- Ou, A. W., M. M. Gu, and F. M. Hult. 2023. “Translanguaging for Intercultural Communication in International Higher Education: Transcending English as a Lingua Franca.” International Journal of Multilingualism 20 (2): 576–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2020.1856113.

- Ou, A. W., M. M. Gu, and J. C.-K. Lee. 2022. “Learning and Communication in Online International Higher Education in Hong Kong: ICT-mediated Translanguaging Competence and Virtually Translocal Identity.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2021.2021210

- Ou, A. W., F. M. Hult, and M. M. Gu. 2022. “Language Policy and Planning for English-Medium Instruction in Higher Education.” Journal of English-Medium Instruction 1 (1): 7–28. https://doi.org/10.1075/jemi.21021.ou

- Pecorari, D., and H. Malmström. 2018. “At the Crossroads of TESOL and English Medium Instruction.” TESOL Quarterly 52 (3): 497–515. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.470

- Pennycook, A. 2017. “Translanguaging and Semiotic Assemblages.” International Journal of Multilingualism 14 (3): 269–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2017.1315810

- Pennycook, A. 2018. “Posthumanist Applied Linguistics.” Applied Linguistics 39 (4): 445–461. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amw016.

- Phillipson, R. 2009. “English in Globalisation, a Lingua Franca or a Lingua Frankensteinia?” TESOL Quarterly 43 (2): 335–339. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1545-7249.2009.tb00175.x

- Querol-Julián, M. 2021. “How Does Digital Context Influence Interaction in Large Live Online Lectures? The Case of English-Medium Instruction.” European Journal of English Studies 25 (3): 297–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825577.2021.1988265

- Schmidt-Unterberger, B. 2018. “The English-Medium Paradigm: A Conceptualisation of English-Medium Teaching in Higher Education.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 21 (5): 527–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1491949

- Thibault, P. J. 2011. “First-Order Languaging Dynamics and Second-Order Language: The Distributed Language View.” Ecological Psychology 23 (3): 210–245. doi:10.1080/10407413.2011.591274.

- Zhu, H., W. Li, and D. Jankowicz-Pytel. 2020. “Whose Karate? Language and Cultural Learning in a Multilingual Karate Club in London.” Applied Linguistics 41 (1): 52–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amz014.