ABSTRACT

The current study developed and validated a holistic and domain-specific scale for measuring the second language (L2) learning experience within the framework of the L2 Motivational Self System. Underpinned by positive psychology theories, a preliminary item pool was generated through combining insights from extant measurements, interviews with Chinese learners of various L2s (e.g. Japanese, French, German, Spanish), as well as literature L2 motivation. This L2 learning experience scale (LLES) was firstly piloted with 302 Chinese language-major undergraduates and further validated with a sample of 304 students from similar backgrounds. Both exploratory factor analysis as well as confirmatory factor analysis were conducted respectively to unravel its factorial structure and examine the model fit, validating a 28-item LLES with six dimensions (e.g. Positive emotions; Negative emotions; Engagement; Relationship; Meaning; Accomplishment). Validity and reliability analyses further established the convergent and divergent validity of the scale, exhibiting robust psychometric properties. The results revealed that the LLES is a sound scale for measuring learners’ multifaceted L2 learning experience and could add new insights into learners’ L2 motivational development.

Introduction

Second language (L2) learning experience is to the L2 Motivational Self System (L2MSS) what emotion is to second language acquisition (SLA): both are ‘elephants in the room’ within its own kind (Prior Citation2019). While the role of L2 learning experience has been widely recognised and emphasised for decades (Csizer and Kormos Citation2009; Csizér and Kálmán Citation2019a), this third constituent of the L2MSS has been largely absent from L2 motivation literature (Al-Hoorie Citation2018; Ushioda Citation2011). As empirical inquiries have evidenced (e.g. Huang Citation2019; Lamb Citation2012; Papi and Teimouri Citation2012; You and Dörnyei Citation2016), L2 learning experience can be the most powerful predictor of motivated behaviour, as well as a strong predictor of other criterion measures such as intended efforts and language achievement. In this case, its marginalised status within the realm of L2 motivation is unjustified.

Ignorance about the L2 learning experience, which is as significant, if not more so than, motivational self guides, might be attributed to two factors. Firstly, this notion has long been ill-defined and under-theorised (Csizér and Kálmán Citation2019a). Following Dörnyei’s (Citation2009) encompassing yet slightly ambiguous definition, researchers have struggled to determine what the construct of L2 learning experience should entail, both theoretically and empirically. The decision of whether to focus solely on immediate classroom-related factors or to broaden the scope to include past out-of-school experiences continues to be a topic of debate (Asker Citation2012). Secondly, its measurement is problematic. As an add-on component to the L2MSS, the operationalisation of L2 learning experience suffers from a jangle fallacy, a situation in which multiple terms are used to refer to the same construct of L2 learning experience. Oftentimes, researchers have aimed to investigate learners’ L2 learning experience in the literature review while employing items assessing ‘attitudes towards language learning’ in its instrument (e.g. Taguchi, Magid, and Papi Citation2009; You and Dörnyei Citation2016). Other terms commonly used in research underpinned by the L2MSS include ‘L2 learning attitude’ (Kormos, Kiddle, and Csizer Citation2011) and ‘English learning experience’ (Papi Citation2010), with the latter unconsciously equating the L2 with English. In general, regardless of the terminology used in studies, L2 learning experience is usually assessed with a brief scale (Dörnyei Citation2019) comprising items addressing only a few aspects of learners’ experience, such as learners’ attitudes toward the foreign language or their enjoyment of the classroom setting. While such scales may focus on some important aspects, their inability to fully capture the complexity of the L2 learning experience necessitates the development and utilisation of more extensive and diversified scales.

Therefore, I sought to fill this research gap by developing and validating a multi-dimensional scale to uncover the nuances of the L2 learning experience. Specifically, I employed positive psychology (PP) principles as my theoretical base, and I targeted learners of languages other than English (LOTEs) to address the prevalent monolingual bias in SLA (Dörnyei and Al-Hoorie Citation2017). As a first attempt to develop a comprehensive yet parsimonious scale to measure the L2 learning experience, this study will expand the current viewpoints of the conceptual and empirical inquiry of L2 motivation.

Literature review

Conceptualisation of the L2 learning experience

Distinct from the other two future self guides in the L2MSS, namely the ideal L2 self and the ought-to L2 self, L2 learning experience refers to the executive motives of learning contexts, including the impact of the teacher, curriculum, peer group, and experience of success (Dörnyei, Citation2009), aspects which can exert profound influences on L2 learning motivation (Wang and Liu Citation2020). In parallel with the motivational renaissance that occurred in the 1990s, which brought the impacts of the classroom learning situation to the fore (Mahmoodi and Yousefi Citation2021), L2 learning experience was originally included as an add-on constituent to the L2MSS to acknowledge those situation-specific factors in the immediate classroom. However, convinced by the potential of the novel self approach, motivational scholars have generally focused on the two future selves, so little elaboration has been provided on the conceptualisation of the L2 learning experience (Dörnyei and Ryan Citation2015), leaving it as ‘the Cinderella of the L2 Motivational Self System’ (Dörnyei Citation2019, 22).

The unspecified nature of the L2 learning experience is observable in extant L2 motivation research in which scholars have tended to develop their own interpretations of this umbrella term (Hiver et al. Citation2019). In You and Dörnyei’s (Citation2016) large-scale survey of English learning motivation in China, language learning experience was operationalised as attitudes toward L2 learning and used items such as ‘I find learning English really interesting’ to measure this construct (501). This working definition of L2 learning experience, however, is more concerned with students’ appraisal of the language than their situation-specific motives, as proposed in the L2MSS. Contrastingly, Lamb (Citation2012) broadened the concept in their research on Indonesian English as a foreign language students’ motivation. Taking a more inclusive perspective, he not only examined classroom L2 learning experience but also included out-of-school learning experience. Similarly, Csizér and Kálmán (Citation2019a) recognised the complexity of language learning experience and advocated that it entails both concurrent and retrospective aspects. Underpinned by Douglas Fir Group’s (Citation2016) framework, they mapped the L2 learning experience on the micro, meso, and macro levels, with components ranging from interactional resources and the impacts of school and family to cultural and economic values.

More recent attempts delving into the theorisation of L2 learning experience have mirrored the general trends in SLA. One prominent focus has been on the dynamic development of people situated in real contexts (Hiver and Al-Hoorie Citation2016). For instance, Hiver et al. (Citation2019) innovatively employed the complex dynamic systems theory to reframe the L2 learning experience. Specifically, they operationalised this construct more organically as a ‘relational and soft-assembled complex system’ (Hiver et al. Citation2019, 87), suggesting that L2 learning experience comprises four prototypical scenes: initiating language learning, sparking interest, overcoming difficulties, and fostering human connections. Notably, their results foregrounded emotional loading in learners’ narrative interviews, which plays a key role in their motivated behaviours. Concomitant with recent research interests in learner engagement (Guo, Xu, and Chen Citation2022; Sinatra, Heddy, and Lombardi Citation2015), Dörnyei (Citation2019) critically reflected on his original definition of the L2 learning experience and employed an engagement-specific perspective to revisit this concept. In his new proposal, the L2 learning experience is defined as ‘the perceived quality of the learners’ engagement with various aspects of the language learning process’ (Dörnyei Citation2019, 25). He also spelled out an array of specific facets for learner engagement, such as the school context, peers, learning tasks, and teachers.

Despite these initial efforts to retheorise the L2 learning experience, several issues should be addressed before elucidating its crucial role in learners’ motivational development. Firstly, while there is no consensus for what components comprise the construct of L2 learning experience, it is certainly a multi-dimensional conglomerate (Csizér and Kálmán Citation2019b). Diachronically, it should not be confined to immediate classroom experience; rather, retrospective L2 learning experiences from the past should also be included. Recurrent dimensions that scholars have mentioned entail teacher–student rapport, experience of success, positive affect, and classroom-relevant factors (e.g. Csizér and Kálmán Citation2019a; Dörnyei Citation2019; Hiver et al. Citation2019). However, these facets are rather fragmented, presenting a challenge for researchers who seek to investigate this construct systematically. An appropriate theoretical framework is therefore needed to determine these facets so that a holistic understanding of learners’ L2 learning experience can be developed (Asker Citation2012; Dörnyei Citation2019). Secondly, the measurement of the L2 learning experience is problematic. As mentioned earlier, although the L2 learning experience is characterised by its multidimensionality, researchers have tended to simplify the instrument, using only a few items to assess learners’ attitudes toward the language. To explore the underlying mechanism of L2 motivational development, it is thus crucial to develop and validate a multi-faceted scale that can measure the complex L2 learning experience.

Measuring L2 learning experience through a positive psychology lens

One frequently used instrument to gauge L2 learning experience is derived from Taguchi, Magid, and Papi’s (Citation2009) comparative study in which they examined whether the L2MSS can be generalised to other cultural contexts. Four items measuring learners’ attitudes toward learning English were validated in both the Japanese and Chinese contexts, and six items were utilised in Iran. However, given the multidimensionality of the L2 learning experience (Csizér and Kálmán Citation2019a), a prerequisite is to identify a new theoretical framework that would allow for a more detailed and elaborate measurement (Dörnyei Citation2019).

Echoing recent ‘emotional turns’ in the field of SLA (Dewaele and Li Citation2020), I aimed to employ a model based on PP to develop a new scale explaining the L2 learning experience. Contrary to the predominant emphasis on hindrances to learners’ language development, PP prioritises what may enrich learners and help them to flourish (Dewaele et al. Citation2019; MacIntyre and Gregersen Citation2012). As such, incorporating PP principles into L2 motivation research facilitates a holistic understanding of learners’ complex experiences by creating a balance between positive and negative contextual factors. Among several notable PP frameworks such as Seligman’s (Citation2011) PERMA model, Oxford’s (Citation2016) EMPATHICS construct, and the most recent E4MC model of language learner well-being (Alrabai and Dewaele Citation2023), I chose Seligman’s (Citation2011) PERMA construct to guide my measurement of L2 learning experience. This five-dimensional model, which assesses learners’ positive emotions (P), engagement (E), relationships (R), meaning (M), and accomplishment (A), serves as an appropriate framework for interpreting L2 learning experience due to its theoretical alignment with L2 motivation and its widely validated measurement approach.

Firstly, PERMA has great relevance and explanatory potential for learners’ L2 learning experience and motivation. Central to the PERMA model is positive emotions, which include ‘positively valenced emotions such as joy, contentment, and excitement’ (Schwartz et al. Citation2016, 518). The positive emotions that L2 learners experience can play a key role in their language learning process given its ‘broaden (momentary thought–action repertories) and build (enduring personal resources)’ features (Fredrickson Citation2003; Citation2013). Specifically, emotions can help learners cope with future opportunities and challenges, producing a motivating force to act (MacIntyre and Gregersen Citation2012; Reeve Citation2005). Engagement refers to involvement and participation in an activity (Seligman Citation2011) and includes multiple aspects of students’ L2 learning experience, such as their engagement with the course materials and cognitive effort to improve their learning proficiency. Mercer and Dörnyei (Citation2020) suggested that the essence of the engagement construct resides in the behavioural aspect, which mirrors active participation and serves as a crucial foundation for subsequent motivation. The third element of PERMA is relationships, which relate to people’s interactions with others and features prominently in learners’ L2 learning experience. Interpersonal connections, including the teacher–student relationship (e.g. Goetz et al. Citation2022; Henry and Thorsen Citation2018), peer dynamics (e.g. Machin Citation2020), and relationships with significant others (e.g. role models) (e.g. Muir, Dörnyei, and Adolphs Citation2021), can have immediate influences on students’ motivated behaviours. The fourth dimension of PERMA, meaning, is associated with people’s beliefs and values (Seligman Citation2011). From the perspective of language acquisition, this facet can be succinctly interpreted as an answer to the inquiry, ‘Why is learning a language meaningful?’ The last element of Seligman’s (Citation2011) PERMA model, accomplishment, embodies a learner’s advancement toward their personal goals and their capabilities to undertake relevant tasks. Gregersen (Citation2019) pioneered the explicit application of the PERMA model to explain learners’ L2 motivation, positing that both engagement and accomplishment correlate with students’ sustained efforts in L2 learning, while relationships and meaning hold more relevance to students’ initial L2 motivation. Another relevant study was conducted by Oxford and Cuéllar (Citation2014), who examined Chinese as a foreign language learners’ narratives using the PERMA construct and found that all five facets manifested in students’ L2 learning experience. Similarly, Li and Liu (Citation2023) applied the PERMA model to conceptualise language learning experience among international students of Chinese. Their research indicated that the L2 learning experience is a multi-faceted construct that involves five interconnected elements: emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment. These elements, crucially, are not static but continually interact throughout the L2 learning process, influencing learners’ motivation in both positive and negative directions.

In addition, I selected PERMA as an overarching framework since it has a well-established self-report measurement, which can lay the foundation for future adaptations. Underpinned by Seligman’s (Citation2011) theory of PERMA, Butler and Kern (Citation2016) undertook a large-scale quantitative study and developed a 15-item PERMA Profiler to measure people’s overall well-being. In this scale, additional eight items were added specifically to assess individuals’ negative emotions, loneliness, and general physical health. This corresponds well with the assertion that PP does not ignore the negative aspects of life but, instead, aims to utilise positive experiences in addressing these problems (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi Citation2000). As a prominent well-being measure, the multi-dimensional PERMA Profiler has been applied in various educational contexts and has demonstrated solid psychometric properties (e.g. Coffey et al. Citation2016; Umucu et al. Citation2020; Wammerl et al. Citation2019). However, despite its usefulness as a domain-general measure for people’s flourishing, no study within the realm of L2 research has employed the PERMA Profiler to measure the L2 learning experience. As such, I aim to develop and validate a PERMA-informed L2 learning experience scale (LLES) to capture the nuances of the L2 learning experience. To do so, I pose the following research questions:

RQ1: What is the factorial structure of the L2 learning experience?

RQ2: To what extent is the L2 learning experience scale valid and reliable?

Methodology

Research context

This research was part of a larger investigation into Chinese learners’ LOTE motivation, and the ultimate goal was to discover how L2 learning experience contributes to LOTE motivational dynamics over time. Therefore, the current research was designed as the first stage of this investigation, with a focus on the development and validation of a PP-informed scale to measure L2 learning experience, which can be used alongside other motivational instruments to track learners’ motivational trajectories. As previously noted, existing scales for assessing L2 learning experience were primarily developed within the context of English language learning. To counteract this monolingual bias, I undertook the present study within the setting of LOTE learning, involving learners from language degree programmes in ordinary universities in China (not as elite as China’s ‘Double First Class’ universities, a list that includes some of the top universities in the country such as Tsinghua University and Peking University). Specifically, data were collected from both English majors, who were required to learn a LOTE as part of their curriculum, and LOTE majors, who pursued an undergraduate degree in a LOTE. In China, LOTE learning is a compulsory part of the English major curriculum, and students can choose a LOTE to study from the available options. After four semesters (approximately 256 credit hours) of LOTE learning, they must reach the level of a second-year student in the corresponding language (Zhao and Li Citation2014). As such, these English majors represent a significant proportion of LOTE learners in China and are thus worth investigating. Specifically, I recruited two samples of Chinese language-major undergraduates for developing and validating the scale. presents the demographics of the participants.

Table 1. Demographics of the participants.

Research design

Following Boateng et al.’s (Citation2018) guidelines for validating a scale, I employed a three-phase research design including item development, scale development, and scale evaluation. During the first stage, I conducted 12 semi-structured interviews with both English majors and LOTE majors to gain a nuanced understanding of their L2 learning experience.Footnote1 Subsequently, I synthesised the insights from the interviews, existing measurements, and pertinent literature to construct a model of L2 learning experience. This led to a preliminary pool of items, all in Chinese, which was the native language of the target participants. As a second step, these items were subjected to a series of validity and reliability tests that involved five SLA experts (for face validity) and 294 Chinese LOTE learners (for exploratory factor analysis, EFA). Corresponding revisions were made, and I developed a finer scale measuring various facets of the L2 learning experience. During the third and last phase, I conducted confirmatory factor analysis with another sample of 304 Chinese LOTE learners to evaluate the scale’s psychometric properties.

Scale construction

As mentioned in the above section, the scale items used for further analysis were derived from three sources: established measurements available in mainstream psychology, theoretical input from SLA literature, and interviewees’ opinions. To start with, I chose Butler and Kern’s (Citation2016) PERMA Profiler, a widely validated questionnaire within the realm of PP, to serve as a foundation for item exploration. Specifically, each dimension of the PERMA construct, namely individuals’ positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment, is assessed with three items. However, since these items are relatively generalised, I made several revisions to render them suitable for the language learning domain. For instance, I changed the item under the engagement dimension, ‘How often do you become absorbed in what you are doing?’ to ‘How often do you become absorbed in L2 learning?’

Having determined the core dimensions and elements of the scale, I also examined recent scholarship at the intersection of PP and SLA, particularly concerning emotions and engagement, to garner more information and inspiration. Compared to the original PERMA Profiler, which focuses on a limited set of positive emotions (contentment and joy), I expanded the item repertoire to encompass a broader variety of positive emotions, such as interest, hope, and pride. In addition, considering the ambivalence in SLA, namely the co-occurrence of negative and positive emotions (Mercer and MacIntyre Citation2014), I added another dimension, negative emotions, to capture the complexity embedded in the L2 learning experience. I similarly expanded and revised the items of the other dimensions. For instance, due to the multi-faceted nature of engagement (Zhou, Hiver, and Al-Hoorie Citation2021), I included multiple items to evaluate students’ behavioural, cognitive, and social engagement in L2 learning.

During the last stage of item pool generation, I drew on the information obtained from the 12 Chinese LOTE learners (six English majors and six LOTE majors) via the semi-structured interviews to extend and complement the scale items. That is, I asked overarching questions addressing why students chose to learn an L2, various aspects of their L2 learning experience, and how this learning experience contributed to their motivational development. As expected, their responses confirmed the prevalent existence of both negative and positive emotions when learning an L2 and added valuable supplements to the item pool.

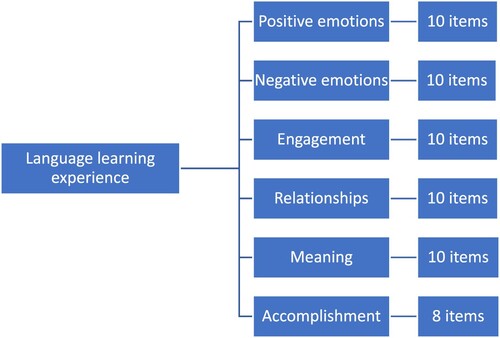

Overall, with the combined expertise from the three aforementioned sources, a preliminary six-dimension, 58-item scale was generated to measure learners’ L2 learning experience (). For this scale, respondents are required to indicate to what extent they agree with the statements about their L2 learning experience on a six-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Notably, I adopted an even number rating scale to prevent respondents from choosing the middle option without making a real choice (Dörnyei Citation2003). To ensure clear and accurate expressions and understanding, all the scale items are in Chinese.

Procedure and data collection

Prior to conducting an array of statistical validation tests to confirm the psychometric properties of the scale, two groups of people first reviewed the newly developed LLES to evaluate its content validity (Boateng et al. Citation2018). Five expert judges (SLA researchers) were invited to scrutinise the items and offer advice on the following issues: i) whether each item measures the targeted aspect of language learning experience; ii) whether the statement is ambiguous or leads to confusion. Considering their suggestions, I made corresponding revisions including deleting, rewording, and adding certain questions, leaving 56 items in total for further analysis. Then, a second round of content validity checking was conducted with the help of 15 LOTE learners from an average university in China, who were asked to read through and answer all the items. Incorporating their comments with the completed questionnaire, I refined the wording of a few statements, finalising a 56-item scale for subsequent validation.

Having finished the first stage of item pool generation, I employed a convenience sampling strategy to recruit samples in order to proceed with the next two phases of scale development and evaluation. I uploaded all the initial scales to www.wjx.cn, an online platform for survey design and administration, and QR codes were generated and inserted in a ‘call for participants’ poster. Then, I contacted my friends who were English or LOTE majors and teachers who taught English or LOTE majors and asked them to distribute the posters to my target population. I strictly followed ethical guidelines throughout, and informed consent was required prior to participation in the research.

Results

RQ1: what is the factorial structure of the L2 learning experience?

To reveal the underlying structure of the newly developed 56-item LLES, I conducted EFA to address the first research question.

Preliminary analyses

I examined initial EFA statistical requirements by conducting item-level descriptive analyses, including normality tests and overall reliability coefficient tests (Phakiti Citation2018). Firstly, as Hair et al. (Citation2010) and Byrne (Citation2010) stated, data are considered normally distributed if the skewness falls between −2 to +2 and if kurtosis falls between −7 to +7. Following these criteria, the skewness and kurtosis of all 56 items in the scale were within the range of −1.987 to 1.249 and −1.214 to 6.905, respectively, demonstrating that the univariate normalities of the item data were supported. To continue with an EFA approach, I also calculated the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the 56-item questionnaire, which was 0.941, well above the cut-off value of 0.70 (Phakiti Citation2018).

Exploratory factor analysis of the LLES

To determine the number of latent constructs of the LLES and its factor structure and to obtain a parsimonious scale, I conducted EFA using IBM SPSS Statistics 28.0 software. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure indicated a KMO of 0.945, larger than 0.60, indicating data sampling adequacy (Fabrigar and Wegener Citation2012). Bartlett’s test of sphericity was also desirable (p < 0.001), confirming strong inter-item correlations and suggesting that the scale is factorable (Osborne Citation2014). Principal component analysis with varimax rotation was incorporated to extract the underlying dimensions. Specifically, while the scale was considered to consist of six dimensions, this limit was not imposed during the extraction process. Item and factor retention decisions were determined by the following criteria: i) factors with an eigenvalue greater than 1 (Kaiser criterion), ii) the scree plot, iii) factor loadings greater than 0.50, and iv) substantive interpretability and theoretical consistency of the factor structure (Hair et al. Citation2010; Phakiti Citation2018). Notably, a general cut-off value for an item to be retained is 0.30 or 0.40 (e.g. Field Citation2018; Osborne Citation2014), but I chose a minimum factor loading of 0.50 so that at least 25% of the shared variance could be extracted (Phakiti Citation2018). As a result, a total of 18 items (5c, 5 h, 6d, 6 g, 6j, 7f, 7 g, 7 h, 7i, 7j, 8a, 8b, 8e, 8f, 8 g, 8i, 9a, 9 h) were eliminated, leaving a 38-item LLES (see ). Contrary to the initial proposal of six dimensions, a total of seven factors were extracted, each with an eigenvalue greater than 1. These seven factors collectively accounted for 72.35% of the variance, and the individual contributions of these factors to the overall variance can be seen in .

Table 2. Results of exploratory factor analysis: Factors, items, and loadings for 38 items.

Table 3. Total variance explained (seven-factor extraction).

Factor 1 included nine items assessing an array of positive emotions that students might experience during their language learning process, including enjoyment, interest, hope, pride, and contentment (MacIntyre and Gregersen Citation2012; MacIntyre and Vincze Citation2017). Therefore, this factor was labelled ‘positive emotions.’ One sample item was, ‘When I do well in L2 learning, my heart pounds with pride.’ Factor 2 assessed multiple negative emotions and, when combined with factor 1, constituted essential components of the language learning process (Dewaele and MacIntyre Citation2016). In addition to the well-researched negative emotion of anxiety, the seven items for factor 2 assessed students’ boredom, shame, frustration, diffidence, and guilt, providing an overview of their emotion-charged experience. One sample item was, ‘I feel a sense of shame when performing badly in L2 exams.’ The hypothesised third dimension of engagement, however, was divided into two factors, with factor 3 labelled ‘behavioural engagement’ and factor 4 labelled ‘cognitive engagement.’ This categorisation agrees with previous work stating that engagement is a multi-faceted construct that can manifest as cognitive, emotional, social, and behavioural facets (Hiver et al. Citation2021; Philp and Duchesne Citation2016). Of relevance to the study, three items were included to measure learners’ in-class participation or behavioural engagement (Reschly and Christenson Citation2012). One sample item was, ‘I pay attention to what teachers have said in class.’ Factor 4 comprised four items, reflecting the mental processes and cognitive efforts of students, such as asking questions, providing feedback, and using strategies (Svalberg Citation2018). One sample question was, ‘I adopt various strategies to learn the L2.’ Factor 5 was associated with students’ interpersonal interactions established during the learning process and was labelled ‘relationships.’ Altogether, five items were included to reflect the influence of the teacher–student relationship on students’ motivated behaviours (Henry and Thorsen Citation2018). One sample question was, ‘I receive help and support from my teachers when learning the L2.’ Admittedly, other forms of relationships such as peer interactions or relationships with significant others are also important features of students’ language learning experience (Busse and Williams Citation2010; Zhang and Tsung Citation2021), but items assessing these aspects were removed from the scale due to their insufficient factor loadings. As such, only teacher–student relationships were assessed. Factor 6 contained four items and was labelled ‘meaning,’ examining in what way learning an L2 is meaningful to students. One sample item was, ‘Language skills offer a competitive edge in the global job market.’ The last factor of the LLES was ‘accomplishment,’ and as per Seligman’s (Citation2011) conceptualisation, this dimension entailed making progress toward goals and realising them. Notably, it did not only refer to objective achievements such as test scores or awards but also encompassed the feeling of being capable of executing certain behaviours. Factor 7 comprised six items, one of which was, ‘I often achieve the important goals I have set for myself in learning the L2.’

Having determined the factors and items retained, I then performed reliability analyses to examine the internal consistency of the refined scale. summarises the names of the newly extracted factors and their corresponding Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. As shown in the table, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for both the individual factors and overall LLES were well above the threshold of 0.70 (Phakiti Citation2018), suggesting high reliability.

Table 4. The seven factors extracted, the number of items, and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients.

RQ2: to what extent is the L2 learning experience scale valid and reliable?

The final stage of scale evaluation was conducted to further examine whether the hypothesised factors fit the collected data (Boateng et al. Citation2018). Specifically, the seven-dimension, 38-item LLES derived from the EFA was subjected to confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess its construct validity (Brown Citation2006). I also tested other psychometric properties, including convergent validity, discriminant validity, and reliability, to validate this newly developed measurement.

Preliminary analyses

Prior to proceeding with CFA to confirm the factorial structure obtained via the EFA, I conducted several tests to ensure that the data were multivariate normal and that there were no outliers (Byrne Citation2010). As a prerequisite to the assessment of multivariate normality (DeCarlo Citation1997), I first conducted univariate normality tests. The skewness and kurtosis of all 38 items ranged from −1.329 to 0.323 and −0.971 to 2.334, respectively, indicating univariate normal distribution. However, the value of Mardia’s (Citation1974) normalised estimate of multivariate kurtosis was 55.131, suggestive of multivariate non-normality in the sample. While this evidence for multivariate kurtosis may be problematic for interpretations based on the usual maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) (Byrne Citation2010), if all individual variables exhibit univariate normality, departures from multivariate normality are inconsequential (Hair et al. Citation2010). As such, MLE was still chosen as the estimation method for subsequent analysis. The squared Mahalanobis distance (D2) for each variable was computed to identify multivariate outliers (Byrne Citation2010), and since no variable showed a D2 that was substantially different from that of the other variables, no outliers were removed from the dataset.

Confirmatory factor analysis of the LLES

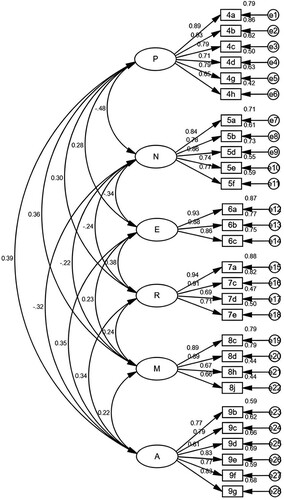

Having dealt with the critical requirements and statistical assumptions, as mentioned earlier, I undertook CFA with MLE using AMOS 28.0 to confirm the validity of the seven-factor LLES. I employed multiple commonly applied fit indices to assess the overall fitness, including chi-squared fit statistics/degree of freedom (CMIN/DF), the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardised root mean residual (SRMR). Following the goodness-of-fit criteria that Hu and Bentler (Citation1999) and Kline (Citation2016) provided, the initial CFA results revealed that the model fit was not satisfactory (see ). While the values of the CMIN/DF (2.596 < 3), SRMR (0.073 < 0.08), and RMSEA (0.073 < 0.08) indicated a good fit, both the CFI and TLI failed to meet the criteria, with 0.861 and 0.848, respectively. This lack of fitness might be attributed to the complexity of the proposed model, with not only seven factors but also up to nine items for each factor. Hence, I deleted several items to improve the model fit and obtain a parsimonious model. As Hair et al. (Citation2010) suggested, the standardised loading estimates should be at least 0.5 and ideally over 0.7. In this case, four items (4i, 5 g, 5i, 7b) with factor loadings of less than 0.5 were removed from the dataset. Another four items (6e, 6f, 4e, 4f) were also deleted due to their high modification indices (over 30). At this stage, only two items (6 h, 6i) remained to measure factor 4 (cognitive engagement), which violated the rule that each latent construct should be indicated by at least three items (Hair et al. Citation2010). Taking this into consideration, I removed factor 4 and its remaining two items while ensuring that it was theoretically justified to do so. Finally, a 28-item LLES with six factors was subjected to a second round of CFA, and this revised model fit the data adequately, with CMIN/DF = 1.925, CFI = 0.946, TLI = 0.939, RMSEA = 0.055, and SRMR = 0.054 (see and ). In addition, standardised factor loadings all exceeded the 0.50 threshold, suggesting that the items were strongly associated with their corresponding constructs, which is a fundamental sign of construct validity (Hair et al. Citation2010).

Figure 2. Graphical representation of the six-factor LLES and factor loadings. All modelled correlations and path coefficients are significant (p < .001).

Table 5. Results of the two-round confirmatory factory analysis (N = 304).

The convergent validity, discriminant validity, and reliability of the LLES

In addition to checking construct validity via CFA, several items had to be calculated to establish the convergent and discriminant validity of the LLES (Urbach and Ahlemann Citation2010). Specifically, convergent validity assesses whether scores on items measure the same underlying construct, and this is examined through their factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) (Fornell and Larcker Citation1981). According to the commonly applied criterion, the minimum requirement for item loadings is 0.5 in CFA. Additionally, as a less-biased estimate of reliability than Cronbach’s alpha, CR anticipates a threshold value of 0.7. For AVE, which measures the amount of variance captured by a construct versus the amount of variance caused by a measurement error, a level of 0.5 is acceptable (Fornell and Larcker Citation1981). As shown in , the construct of language learning experience displayed good convergent validity. To assess discriminant validity, the square root of the AVE was used, indicating whether the constructs differed from each other. As Barclay, Higgins, and Thompson (Citation1995) indicated, this attribute for each construct should be larger than the inter-construct correlation. Another guideline that Brown (Citation2006) provided is that inter-construct correlations should be less than 0.85. Taking these requirements into account, the discriminant validity of the LLES could be considered satisfactory ().

Table 6. The convergent validity of each sub-scale.

Table 7. The discriminant validity and inter-construct correlations of each sub-scale

In assessing the reliability of the LLES, I calculated two statistics, including Cronbach’s alpha and CR. Firstly, the Cronbach’s alphas for the whole scale and its six subscales were 0.839, 0.911, 0.898, 0.920, 0.887, 0.860, and 0.913. Similarly, as presented below in , the CR values for each sub-scale were 0.913, 0.898, 0.921, 0.888, 0.863, and 0.913, respectively. Overall, these coefficients were above the cut-off value of 0.70 and were indicative of satisfactory internal consistency (Hair et al. Citation2010).

Discussion

Employing Boateng et al.’s (Citation2018) three-phase research design for validating a scale, the current study involved developing a self-report inventory, the LLES, for evaluating learners’ L2 learning experience. Following the three-step process of item generation, scale development, and scale evaluation, the 28-item LLES was established. This scale, featuring the six dimensions of positive emotions, negative emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment, was found to be a valid and reliable scale with desirable psychometric properties.

The first research question aimed to uncover the factorial structure of the proposed six-factor LLES. The initial scale facets and core items were generated based, in part, on Butler and Kern’s (Citation2016) PERMA Profiler, complemented by recent scholarship at the intersection of PP and SLA and insights from interviewees’ accounts of their language learning experience. Altogether, seven factors were extracted from the EFA, which was slightly different from the original six-factor proposal. Specifically, the proposed ‘engagement’ sub-scale was divided into two dimensions. Per the definitions that Reschly and Christenson (Citation2012) and Svalberg (Citation2018) provided, these two factors were labelled ‘behavioural engagement’ and ‘cognitive engagement.’ This emergence of the sub-categories was consistent with findings from earlier studies indicating that engagement is a multi-dimensional concept with both cognitive and behavioural facets (Hiver et al. Citation2021).

Furthermore, CFA was performed to address the second research question and finally develop a vigorous and psychometrically sound measurement of language learning experience within the realm of SLA. This 28-item LLES features six factors, namely positive emotions, negative emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment. Notably, while the EFA results indicated seven factors, as mentioned earlier, the factor of ‘cognitive engagement’ was removed after considering the high modification indices of its items and the rule of ‘at least three items for one sub-scale’ (Hair et al. Citation2010). As such, only the sub-scale of ‘behavioural engagement’ was kept in the construct, and to render it more conceptually inclusive, I relabelled it ‘engagement.’ This manifestation of ‘behavioural engagement’ from the dataset supports Mercer and Dörnyei’s (Citation2020) statement that the behavioural facet lies at the core of the engagement construct and accords well with the empirical findings from Guo, Xu, and Chen (Citation2022) showing that language learners report the highest level of behavioural engagement in interactive classrooms.

Overall, after the deletion and refinement of the factors and items, a 28-item LLES with six factors was finally established and validated, indicating desirable construct validity, convergent validity, discriminant validity, and reliability (Boateng et al. Citation2018). To address the conceptual fuzziness surrounding the notion of language learning experience, this LLES scale indicates a broader theorisation that extends beyond the confines of context (within versus outside the classroom) and temporality (immediate versus past learning experience). By capturing the nuances embedded in students’ language learning process from multiple angles, this scale offers a comprehensive and operational conceptualisation of language learning experience that can be utilised in future research. The current LLES also broadens the scope of the conventional operationalisation of this component, which typically utilises a few items measuring learners’ attitudes toward L2 learning (e.g. Kormos, Kiddle, and Csizer Citation2011; Taguchi, Magid, and Papi Citation2009), by including the emotional, behavioural, and social dimensions of language learning experience. Specifically, in response to MacIntyre, Gregersen, and Mercer’s (Citation2019) call for a more holistic view of L2 learners’ emotions, an appropriate number of items was included to assess learners’ positive and negative emotional states when learning an L2. This integration of two opposing emotional types allows for a nuanced understanding of their joint effects on the language learning process, which would otherwise be incompletely examined (Dewaele and Dewaele Citation2017; MacIntyre and Vincze Citation2017).

The behavioural aspect of language learning experience is also featured in the scale and mainly addresses students’ behavioural engagement in the classroom. This addition of an engagement-relevant factor is congruent with the proposal of Dörnyei (Citation2019), who recently defined L2 learning experience as ‘the perceived quality of the learners’ engagement with various aspects of the language learning process’ (25). He further detailed multiple facets of learners’ L2 learning process and environment that can be engaged with, including the school context, teaching materials, learning tasks, peers, and teachers. This retheorisation can be considered an expansion of the original definition of L2 learning experience in the L2MSS, which refers to the executive motives of learning situations, such as the impact of the teacher, curriculum, peer group, and experience of success (Dörnyei, Citation2009). However, while this engagement-related specification offers a promising way to capture the complexity of the language learning process, the current LLES prioritises behavioural engagement, which is the ‘core construct and most prototypical of engagement’ (Skinner et al. Citation2008, 778).

The scale also considers the social aspect of L2 learning experience, especially the teacher–student relationship. The need for relatedness or the feeling of being supported can offer great help when learners need to deal with demanding tasks and can boost their motivation (Henry and Thorsen Citation2019). Notably, while the factor of ‘relationships’ should theoretically cover a range of social interactions such as teacher–student relationships, peer relationships, and the role of significant others (Williams and Burden Citation1997), only the teacher–student relationship is included in the scale. This is mainly because Chinese LOTE learners predominantly accumulate their L2 learning experiences within the classroom setting. With the transition to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, the teacher–student relationship assumed greater significance, while opportunities for peer dynamics were significantly limited. As a result, items designed to measure peer relationships in the LLES scale exhibited low factor loadings and were consequently removed during the development process.

Research limitations, future directions, and implications

Although theorising language learning experience and developing a corresponding measurement indicate progress in the field, this cross-sectional study had limitations. Firstly, while this PERMA-informed LLES captures certain aspects of language learning experience, not all are captured. For instance, it does not assess curriculum-related facets such as course goals and materials, which, as Dörnyei (Citation2019) noted, can also be integral to language learning experience. Similarly, as the LLES was deliberately designed as a comprehensive (in terms of dimensions encompassed) yet parsimonious (in terms of items for each factor) scale, certain nuances might become lost during operationalisation. This is particularly the case since the factor of engagement is a meta-construct that includes not only behavioural engagement but also emotional and cognitive engagement (Lin and Huang Citation2018). Hence, focusing only on students’ behavioural participation in language courses may limit the overall view of their language learning process, so it would be advantageous for future researchers to take various aspects of engagement into account when developing the measurement. In addition, only one-time cross-sectional data were collected to develop and evaluate the data. It is well-advised to establish test–retest reliability by administering the scale to the same cohort of participants later (DeVellis and Thorpe Citation2021). In future research, it would also be valuable to confirm the criterion validity of the LLES by comparing it to other established scales assessing L2 learning experience. Additionally, administering the LLES at different time points throughout a language course and correlating scores with objective measures of language proficiency would provide valuable information about the scale’s longitudinal validity and ability to predict language learning outcomes.

Nevertheless, both theoretical and pedagogical implications can be drawn from the current research. Echoing Csizér and Kálmán’s (Citation2019a) call for examining the internal structure of foreign language learning experience, this study makes an initial attempt to develop a PP-informed, multi-dimensional scale to measure this marginalised component in the L2MSS. By assessing students’ emotional states, behavioural engagement, relationships, beliefs (meaning), and accomplishment throughout their language learning process, this scale unpacks the subtleties embedded in their learning experience. As such, it not only facilitates a more holistic understanding of the ill-defined conceptualisation of language learning experience but also offers a psychometrically sound measurement to operationalise this construct in research practice. Specifically, this scale can be utilised in conjunction with other motivational measures of, for instance, goal orientation and self-efficacy, enriching the array of instruments available. In addition, as the fundamental principles of motivation in language learning are not exclusive to a single language, this scale can be readily adjusted and applied across various language learning contexts, facilitating large-scale quantitative data collection in L2 motivation research.

Aside from its theoretical contributions, this LLES is also of pedagogical significance since it offers a specific instrument for teachers to understand learners’ L2 learning experience from various perspectives. This is particularly helpful for those LOTE learners who might encounter distinct challenges in a nuanced sociocultural context in which English learning is oftentimes prioritised (Dörnyei and Al-Hoorie Citation2017). Notably, the linguistic knowledge of learners who learn a LOTE as an L2 depends heavily on instructed learning, which necessitates teachers’ cooperation and strategy use. By administering this scale, teachers can gain insights into their students’ multi-layered language learning experience, even if they lack advanced research skills. This nuanced knowledge will enable them to tailor their instruction, classroom activities, and feedback to effectively promote individual motivation when appropriate. Specifically, these PP-informed principles can also be incorporated into pedagogical innovations or interventions to boost or sustain learners’ L2 learning motivation.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank all the participants for their cooperation and support in my project. Great thanks also go to all my friends who helped distribute the questionnaire.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The term ‘L2 learning’ broadly refers to learning any additional language, and in the context of this research, it is specifically employed to signify the participants’ experience in learning LOTEs rather than English.

References

- Al-Hoorie, A. H. 2018. “The L2 Motivational Self System: A Meta-Analysis.” Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 8 (4): 721–754. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2018.8.4.2.

- Alrabai, F., and J.-M. Dewaele. 2023. Transforming the EMPATHICS Model into a Workable E4MC Model of Language Learner Well-Being. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/366200919_Transforming_the_EMPATHICS_model_into_a_workable_E4MC_model_of_language_learner_well-being.

- Asker, A. 2012. Future Self-Guides and Language Learning Engagement of English-Major Secondary School Students in Libya: Understanding the interplay between possible selves and the L2 learning situation. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Birmingham].

- Barclay, D., C. Higgins, and R. Thompson. 1995. “The Partial Least Squares (PLS) Approach to Causal Modeling: Person Computer Adoption and Uses as an Illustration.” Technology Studies 2: 285–309.

- Boateng, G. O., T. B. Neilands, E. A. Frongillo, H. R. Melgar-Quiñonez, and S. L. Young. 2018. “Best Practices for Developing and Validating Scales for Health, Social, and Behavioral Research: A Primer.” Frontiers in Public Health 6: 149. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149.

- Brown, T. A. 2006. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. New York: Guilford Press.

- Busse, V., and M. Williams. 2010. “Why German? Motivation of Students Studying German at English Universities.” Language Learning Journal 38 (1): 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571730903545244.

- Butler, J., and M. L. Kern. 2016. “The PERMA-Profiler: A Brief Multidimensional Measure of Flourishing.” International Journal of Wellbeing 6 (3). Article 3. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v6i3.526

- Byrne, B. 2010. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

- Coffey, J. K., L. Wray-Lake, D. Mashek, and B. Branand. 2016. “A Multi-Study Examination of Well-Being Theory in College and Community Samples.” Journal of Happiness Studies 17 (1): 187–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9590-8.

- Csizér, K., and C. Kálmán. 2019a. “A Study of Retrospective and Concurrent Foreign Language Learning Experiences: A Comparative Interview Study in Hungary.” Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 9 (1): 225–246. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2019.9.1.10.

- Csizér, K., and C. Kálmán. 2019b. “Editorial.” Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 9 (1): 13–17. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2019.9.1.1.

- Csizer, K., and J. Kormos. 2009. “Learnin Experience, Selves and Motivated Learning Behaviour: A Comparative Analysis of Stuctural Models for Hungarian Secondary and University Learners of English.” In Motivation, Language Identity and the L2 Self, edited by Z. Dornyei, and E. Ushioda,, 98–119. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- DeCarlo, L. T. 1997. “On the Meaning and Use of Kurtosis.” Psychological Methods 2: 292–307. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.2.3.292

- DeVellis, R. F., and C. T. Thorpe. 2021. Scale Development: Theory and Applications. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Dewaele, J.-M., X. Chen, A. M. Padilla, and J. Lake. 2019. “The Flowering of Positive Psychology in Foreign Language Teaching and Acquisition Research.” Frontiers in Psychology 10: 2128. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02128.

- Dewaele, J.-M., and L. Dewaele. 2017. “The Dynamic Interactions in Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety and Foreign Language Enjoyment of Pupils Aged 12 to 18. A Pseudo-Longitudinal Investigation.” Journal of the European Second Language Association 1 (1): 12–22. https://doi.org/10.22599/jesla.6.

- Dewaele, J.-M., and C. Li. 2020. “Emotions in Second Language Acquisition: A Critical Review and Research Agenda.” Foreign Language World 196 (1): 34–49. https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/32797.

- Dewaele, J.-M., and P. D. MacIntyre. 2016. “Foreign Language Enjoyment and Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety. The Right and Left Feet of FL Learning?” In Positive Psychology in SLA, edited by P. D. MacIntyre, T. Gregersen, and S. Mercer, 215–236. United Kingdom: Multilingual Matters.

- Dörnyei, Z. 2003. Questionnaires in Second Language Research: Construction, Administration, and Processing. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Dörnyei, Z. 2009. “The L2 Motivational Self System.” In Motivation, Language Identity and the L2 Self, edited by Z. Dörnyei, and E. Ushioda, 9–42. Bristol, Buffalo, and Toronto: Multilingual Matters.

- Dörnyei, Z. 2019. “Towards a Better Understanding of the L2 Learning Experience, the Cinderella of the L2 Motivational Self System.” Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 9 (1): 19–30. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2019.9.1.2.

- Dörnyei, Z., and A. H. Al-Hoorie. 2017. “The Motivational Foundation of Learning Languages Other Than Global English: Theoretical Issues and Research Directions.” The Modern Language Journal 101 (3): 455–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12408.

- Dörnyei, Z., and S. Ryan. 2015. The Psychology of the Language Learner Revisited. New York: Routledge.

- Douglas Fir Group. 2016. “A Transdisciplinary Framework for SLA in a Multilingual World.” The Modern Language Journal 100 (S1): 19–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12301.

- Fabrigar, L. R., and D. T. Wegener. 2012. Exploratory Factor Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Field, A. 2018. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. 5th edition. Los Angeles: Sage Publications Inc.

- Fornell, C., and D. F. Larcker. 1981. “Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error.” Journal of Marketing Research 18 (1): 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Fredrickson, B. L. 2003. “The Value of Positive Emotions.” American Scientist 91 (4): 330–335. https://doi.org/10.1511/2003.4.330.

- Fredrickson, B. L. 2013. “Positive Emotions Broaden and Build.” In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 47), 1–53. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407236-7.00001-2.

- Goetz, T., M. Bieleke, K. Gogol, J. van Tartwijk, T. Mainhard, A. Lipnevich, and R. Pekrun. 2022. Getting Along and Feeling Good: Reciprocal Associations between Student-Teacher Relationship Quality and Students’ Emotions [Preprint]. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/a2yse.

- Gregersen, T. 2019. “Aligning Positive Psychology With Language Learning Motivation.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Motivation for Language Learning, edited by M. Lamb, K. Csizér, A. Henry, and S. Ryan, 621–640. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28380-3_30.

- Guo, Y., J. Xu, and C. Chen. 2022. “Measurement of Engagement in the Foreign Language Classroom and its Effect on Language Achievement: The Case of Chinese College EFL Students.” International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2021-0118.

- Hair, J. F., W. C. Black, B. J. Babin, and R. E. Anderson. 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective. London: Pearson Education International.

- Henry, A., and C. Thorsen. 2018. “Teacher-Student Relationships and L2 Motivation.” The Modern Language Journal 102 (1): 218–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12446.

- Henry, A., and C. Thorsen. 2019. “Weaving Webs of Connection: Empathy, Perspective Taking, and Students’ Motivation.” Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 9 (1): 31–53. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2019.9.1.3.

- Hiver, P., and A. H. Al-Hoorie. 2016. “A Dynamic Ensemble for Second Language Research: Putting Complexity Theory Into Practice.” The Modern Language Journal 100 (4): 741–756. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12347.

- Hiver, P., A. H. Al-Hoorie, J. P. Vitta, and J. Wu. 2021. “Engagement in Language Learning: A Systematic Review of 20 Years of Research Methods and Definitions.” Language Teaching Research, 136216882110012. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211001289.

- Hiver, P., G. Obando, Y. Sang, S. Tahmouresi, A. Zhou, and Y. Zhou. 2019. “Reframing the L2 Learning Experience as Narrative Reconstructions of Classroom Learning.” Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 9 (1): 83–116. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2019.9.1.5.

- Hu, L., and P. M. Bentler. 1999. “Cutoff Criteria for fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus new Alternatives.” Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6 (1): 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

- Huang, S.-C. 2019. “Learning Experience Reigns – Taiwanese Learners’ Motivation in Learning Eight Additional Languages as Compared to English.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 40 (7): 576–589. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2019.1571069.

- Kline, R. B. 2016. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 4th ed. New York: Guilford Press.

- Kormos, J., T. Kiddle, and K. Csizer. 2011. “Systems of Goals, Attitudes, and Self-Related Beliefs in Second-Language-Learning Motivation.” Applied Linguistics 32 (5): 495–516. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amr019.

- Lamb, M. 2012. “A Self System Perspective on Young Adolescents’ Motivation to Learn English in Urban and Rural Settings.” Language Learning 62 (4): 997–1023. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2012.00719.x.

- Li, Z., and Y. Liu. 2023. “Theorising Language Learning Experience in LOTE Motivation with PERMA: A Positive Psychology Perspective.” System 112: 102975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2022.102975.

- Lin, S.-H., and Y.-C. Huang. 2018. “Assessing College Student Engagement: Development and Validation of the Student Course Engagement Scale.” Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 36 (7): 694–708. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282917697618.

- Machin, E. 2020. “Intervening with Near-Future Possible L2 Selves: Efl students as Peer-to-Peer Motivating Agents During Exploratory Practice.” Language Teaching Research, 136216882092856. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820928565.

- MacIntyre, P. D., and T. Gregersen. 2012. “Emotions that Facilitate Language Learning: The Positive-Broadening Power of the Imagination.” Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 2 (2): 193. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2012.2.2.4.

- MacIntyre, P. D., T. Gregersen, and S. Mercer. 2019. “Setting an Agenda for Positive Psychology in SLA: Theory, Practice, and Research.” The Modern Language Journal 103 (1): 262–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12544.

- MacIntyre, P. D., and L. Vincze. 2017. “Positive and Negative Emotions Underlie Motivation for L2 Learning.” Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 7 (1): 61–88. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2017.7.1.4.

- Mahmoodi, M. H., and M. Yousefi. 2021. “Second Language Motivation Research 2010–2019: A Synthetic Exploration.” The Language Learning Journal, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2020.1869809.

- Mardia, K. V. 1974. “Applications of Some Measures of Multivariate Skewness and Kurtosis in Testing Normality and Robustness Studies.” Sankhyā: The Indian Journal of Statistics, Series B 36: 115–128.

- Mercer, S., and Z. Dörnyei. 2020. Engaging Language Learners in Contemporary Classrooms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mercer, S., and P. D. MacIntyre. 2014. “Introducing Positive Psychology to SLA.” Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 4 (2): 153–172. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2014.4.2.2.

- Muir, C., Z. Dörnyei, and S. Adolphs. 2021. “Role Models in Language Learning: Results of a Large-Scale International Survey.” Applied Linguistics 42 (1): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amz056.

- Osborne, J. W. 2014. Best Practices in Exploratory Factor Analysis. California: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Oxford, R. L. 2016. “2 Toward a Psychology of Well- Being for Language Learners: The ‘Empathics’ Vision.” Positive Psychology in SLA, 10–88. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783095360-003.

- Oxford, R. L., and L. Cuéllar. 2014. “Positive Psychology in Cross-Cultural Learner Narratives: Mexican Students Discover Themselves While Learning Chinese.” Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 4 (2): 173–203. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2014.4.2.3

- Papi, M. 2010. “The L2 Motivational Self System, L2 Anxiety, and Motivated Behavior: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach.” System 38 (3): 467–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2010.06.011.

- Papi, M., and Y. Teimouri. 2012. “Dynamics of Selves and Motivation: A Cross-Sectional Study in the EFL Context of Iran: A Cross-Sectional Study in the EFL Context of Iran.” International Journal of Applied Linguistics 22 (3): 287–309. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-4192.2012.00312.x.

- Phakiti, A. 2018. “Exploratory Factor Analysis.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Applied Linguistics Research Methodology, edited by A. Phakiti, P. De Costa, L. Plonsky, and S. Starfield, 423–457. Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-59900-1_20.

- Philp, J., and S. Duchesne. 2016. “Exploring Engagement in Tasks in the Language Classroom.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 36: 50–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190515000094.

- Prior, M. T. 2019. “Elephants in the Room: An “Affective Turn,” Or Just Feeling Our Way?” The Modern Language Journal 103 (2): 516–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12573.

- Reeve, J. 2005. Understanding Motivation and Emotion. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Reschly, A. L., and S. L. Christenson. 2012. “Jingle, Jangle, and Conceptual Haziness: Evolution and Future Directions of the Engagement Construct.” In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement, edited by S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, and C. Wylie, 3–19. Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_1.

- Schwartz, H. A., M. Sap, M. L. Kern, J. C. Eichstaedt, A. Kapelner, M. Agrawal, E. Blanco, et al. 2016. “Predicting Individual Well-Being Through the Language of Social Media.” Biocomputing 2016: 516–527. https://doi.org/10.1142/9789814749411_0047.

- Seligman, M. E. P. 2011. Flourish: A new Understanding of Happiness, Well-Being-and how to Achieve Them. London: Nicholas Brealey Pub.

- Seligman, M. E. P., and M. Csikszentmihalyi. 2000. “Positive Psychology: An Introduction.” American Psychologist 55 (1): 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5.

- Sinatra, G. M., B. C. Heddy, and D. Lombardi. 2015. “The Challenges of Defining and Measuring Student Engagement in Science.” Educational Psychologist 50 (1): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2014.1002924.

- Skinner, E., C. Furrer, G. Marchand, and T. Kindermann. 2008. “Engagement and Disaffection in the Classroom: Part of a Larger Motivational Dynamic?” Journal of Educational Psychology 100 (4): 765. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012840

- Svalberg, A. M.-L. 2018. “Researching Language Engagement; Current Trends and Future Directions.” Language Awareness 27 (1-2): 21–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2017.1406490.

- Taguchi, T., M. Magid, and M. Papi. 2009. “4. The L2 Motivational Self System among Japanese, Chinese and Iranian Learners of English: A Comparative Study.” In Motivation, Language Identity and the L2 Self, edited by Z. Dörnyei, and E. Ushioda, 66–97. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847691293-005.

- Umucu, E., J.-R. Wu, J. Sanchez, J. M. Brooks, C.-Y. Chiu, W.-M. Tu, and F. Chan. 2020. “Psychometric Validation of the PERMA-Profiler as a Well-Being Measure for Student Veterans.” Journal of American College Health 68 (3): 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2018.1546182.

- Urbach, N., and F. Ahlemann. 2010. “Structural Equation Modeling in Information Systems Research Using Partial Least Squares.” Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application 11 (2): 5–40.

- Ushioda, E. 2011. “Language Learning Motivation, Self and Identity: Current Theoretical Perspectives.” Computer Assisted Language Learning 24 (3): 199–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2010.538701.

- Wammerl, M., J. Jaunig, T. Mairunteregger, and P. Streit. 2019. “The German Version of the PERMA-Profiler: Evidence for Construct and Convergent Validity of the PERMA Theory of Well-Being in German Speaking Countries.” Journal of Well-Being Assessment 3 (2-3): 75–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41543-019-00021-0.

- Wang, T., and Y. Liu. 2020. “Dynamic L3 Selves: A Longitudinal Study of Five University L3 Learners’ Motivational Trajectories in China.” The Language Learning Journal 48 (2): 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2017.1375549.

- Williams, M., and R. L. Burden. 1997. Psychology for Language Teachers: A Social Constructivist Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- You, C. (Julia), and Z. Dörnyei. 2016. “Language Learning Motivation in China: Results of a Large-Scale Stratified Survey.” Applied Linguistics 37 (4): 495–519. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amu046.

- Zhang, L., and L. Tsung. 2021. “Learning Chinese as a Second Language in China: Positive Emotions and Enjoyment.” System 96: 102410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102410.

- Zhao, J., and S. Li. 2014. “da xue sheng wai yu xue xi dong ji de shi zheng fen xi ji qi shi: yi ying yu zhuan ye er wai xue xi dong ji wei li [An Empirical Study of University Students’ Motivation to Learn Foreign Languages: The Case of English Major Students’ Motivation to Learn a Second Foreign Language].” Foreign Language Research 2: 40–44. https://doi.org/10.13978/j.cnki.wyyj.2014.02.015.

- Zhou, S., P. Hiver, and A. Al-Hoorie. 2021. “Measuring L2 Engagement: A Review of Issues and Applications.” In Student Engagement in the Language Classroom, edited by P. Hiver, A. Al-Hoorie, and S. Mercer, 75–98. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788923613-008

Appendix

The L2 learning experience scale (LLES)