ABSTRACT

This study examines how a historical, multilingual space is written and constructed, thus questioning monolingual French language ideology. Two cemeteries in Menton, next to the Italian border on the French Riviera, were visited and documented. The presence of Italian is clearly observable, because of the historic proximity to Italy. But also many other languages are represented, such as for example English, Russian, Polish or German: the city also has a history of being a therapeutic town where many foreigners spent time to recover or stayed because of a mild climate. This is also reflected in the linguistic landscape of the cemeteries. Building on the notions of space/place and of heterotopia, the cemeteries are examined from a qualitative, interpretative perspective. Iconicity in writing and script choice is discussed, as well as multilingualism both on cemetery level, and as pertaining to individual tombstones. The construction of linguistic spaces is examined. The results show that other national languages in the cemeteries do not challenge national French as such. However, graves of African soldiers may still question France’s colonial history and the presence of Occitan can be seen as a reminder of a former vernacular.

Introduction

Cemeteries are charged with messages, visible to visitors who will strive to decipher old inscriptions, wonder at life stories, mourn a relative or a friend, read and interpret epitaphs. Indeed, they offer a view in synchrony, a transverse section of a collective, as well as in diachrony, with a time span of many decades if not centuries. They are a rich source of information, also cultural and linguistic. In this study, we focus on the cemetery as a written multilingual space in France, where since the Revolution monolingual French has been promoted and elevated as the language of the Republic. However, linguistic reality does not always follow political regulations and linguistic ideology, and in many regions a regional vernacular has been spoken, sometimes in parallel with French. This can be said to be especially true in border regions and regions of language contact, where French is supposed to be prevailing, but where we find evidence of historical multilingualism and changes in language use.

Many studies have been conducted on cemeteries, not least from anthropological, urbanist, historical and sociological perspectives (see for example Francis Citation2003; Reimers Citation1999; Rugg Citation1998; Citation2000; Citation2003; Woodthorpe Citation2009), but the study of language in the cemetery is scarcer. Here, so far, we have principally noted articles by Mytum (Citation1994), Eckert (Citation2001), Herat (Citation2014) and Vajta (Citation2018, Citation2020, Citation2021). In the following, we will focus on two cemeteries in Menton, a frontier town on the French Riviera, at the French–Italian border, and examine how a multilingual space is written and constructed over time. Indeed, the town of Menton has a cosmopolitan history, which we will present in the background. Then we will introduce the cemetery as a linguistic ‘place/space’ (Wright Citation2005) and as a heterotopia (Foucault Citation1986). Ensuingly, we will present methodological and theoretical considerations. In the following main section, we will describe and discuss the visited cemeteries as forming a multilingual and multiscriptal space constructed by the evident practice of employing different languages (and scripts) on the tombstones. We will also describe two specific linguistic spaces, the graves of the Tirailleurs and plaques in Occitan, that are included in the cemeteries while making them more complex. Finally, the last section will summarise and conclude the study by considering how the cemeteries are converted into a multilingual space and a heterotopia.

Background

Menton, in the southeast of France, is situated at the border between France and Italy. Traditionally, the language spoken was the Mentonasc, a variant of Niçois and Occitan, close to Ligurian and sometimes claimed as such (see Cuturello Citation2002; Dalbera Citation1994). Like most regional languages and patois, Occitan and Mentonasc do not have a written standard of their own, which makes them unlikely in written texts, epitaphs and signs. This can also explain the presence of written standard Italian alongside the French; even if the spoken vernacular was regional, Italian prevailed until French became the new national standard. However, we find written evidence of the use of more languages than French, despite the latter being the expected language.

The French–Italian border has not moved since 1861 and French has had time to establish itself, even if belonging to France and integration into the Republic might not have been obvious to all since relations to Italy remained strong throughout (Courrière Citation2010). The different variants of Occitan are in decline since several decades; they are hardly not used anymore neither transmitted from the older generations to younger ones (Hammel Citation2012; Kremnitz Citation2017). The history of the town Menton mostly follows the history of the Riviera (the Côte d’Azur), with an important development of tourism starting from the middle of the nineteenth century. Its mild microclimate and location by the Mediterranean Sea has made Menton into one of the major tourist destinations along the coast. Not only tourists but also convalescents and patients suffering from e.g. tuberculosis used to spend their winters here in order to recover their health. The arrival of many foreigners turned the region around Nice and Menton into a rather cosmopolitan one. Moreover, since Menton is a border town having belonged to other rulers than French ones, and since it was a town where many foreigners chose to spend their time, not least Russian and English nationals in particular, we might expect that this would be reflected in the cemeteries’ openly displayed texts, or more precisely in the form of different language choices on the gravestones.

Two municipal cemeteries in Menton were visited for the purpose of this study: the Cimetière du Château and the Cimetière du Trabuquet. They are separate graveyards, delimited by surrounding walls and entrance gates as is typical (Rugg Citation2000), but they are almost neighbouring each other and can therefore be considered as an entity. The Trabuquet is also a military cemetery for soldiers who were killed during the First World War. The cemeteries are open daytime for visitors, both mourners and tourists, but closed at night. Their location on the top of a mountain, scenically overhanging the town, and their offered vistas over the expanse of the Mediterranean and the neighbourhood are stunning, which in part explains why they have become an appreciated destination for city walks – visiting tourists mingle with local mourners and relatives. But even if they are advertised as tourist attractions, they remain above all the burial place for the deceased, both autochthonous and foreign. Their size renders them to a rich source of information, with the epitaphs forming a historical document written in different languages. A walk through the alleys of these graveyards becomes a walk through time and will transport the visitor principally from the beginning of the nineteenth century (in the Cimetière du Château) on to the contemporary tombs (in the Trabuquet), even if newer graves may also be located among older family graves. As many cemeteries, they are mainly chronologically constructed in diachrony over decades and centuries. Thus, they are a tangible illustration of how synchrony and diachrony may be reconcilable and constitute ‘essentially overlapping processes’ (Aitchinson Citation2012, 19).

Monuments of different kinds belong to the cemetery. There are simple graves having not been attended to for years, as well as well-maintained memorials and grave chapels for departed who were better off during their lifetime. The text of the relevant inscription often stresses the level of wealth and cultural capital of the departed, when appropriate: in Menton, we find physicians, princes and princesses, historians, barons, and counts, politicians, architects, and many young persons who did not recover their health and died far from home. Also, a number of celebrities are buried here, which contributes to making the site attractive to tourists. Indeed, it is also striking to the visitor that many different languages are inscribed in the epitaphs. In the Trabuquet in turn, we find delimited sections – the Carrés – that are dedicated to soldiers from the First World War, and the Memorial du Tirailleur, a memorial commemorating the African infantrymen who died in Menton during the First World War. The Carrés can look almost disconnected from the rest of the cemetery. Nevertheless, they are part of it, included within it like a nested Russian Matryoshka doll within a doll. They are therefore also included in this study.

Hence, the present study focuses on how this site can be understood today by passers-by, tourists or residents, together forming an audience which is not a specialist, neither in languages nor in history, yet interested and at times also invested in the meaning of the place. We will describe how these cemeteries reflect multilingual practices following upon the variegated local history and how visitors can identify the different linguistic spaces and recognise the languages employed. We will also discuss what discourses are held and how the presence of the different linguistic spaces could be interpreted, given the overall hegemony of French language.

The cemetery as a linguistic space

Cemeteries are connected to the collective and to society; they are essential to a community. They are part of a village or a town, in a double sense: both on a geographical level as a place, within or close to the town or the village, while delimited by a fence, a hedge or another tangible limit, and on the societal level, as the potential reflection of what is characteristic of the same and of its history. Cemeteries are defined by the graves and the signs themselves (see Blommaert Citation2013, 15–17), a construction or an assemblage developed gradually over time and correlating to historical and societal events, that can be ‘read as a cultural text about society’ (Reimers Citation1999, 150). In many ways, the cemetery is an inclusive place, with young and old, men and women, all connected by the same last event in life – death. At the same time, it is a controlled and regulated place, with stipulated rules and most often limited opening-hours. In France, cemeteries are under the authority of the mayor and the rules do not prohibit a specific language or command a specific spelling of patronyms or local toponyms. They stipulate instead that inscriptions should neither cause offense nor disturb public order (Guide juridique Citation2017, 89), and the assessment of what may cause offense or not is in the end up to the mayor. It is a spiritual space and a physical place all at once (Wright Citation2005, 51), located in or close to a town or a village, sometimes next to a church. It reminds of a paradox and ‘this apparent ordinariness and banality make it extraordinary’ (Wright Citation2005, 69): it is at the same time an ordinary and a banal place that concerns anybody since ‘each family has relatives in the cemetery’ (Foucault Citation1986, 25), but the event of death is final and unique per se.

The cemetery testifies of past and present, and of local and regional history, which in turn also testifies about history at the national level in a tangible way, through its monuments, gravestones, epitaphs and signs. Francis (Citation2003) sees it as a ‘cultural landscape’ and it is often considered as a mirror of society, ‘an epitome of modernity’ with ‘a continuation of the struggles, identity formations, appeals and positionings that characterize our society’ (Jedan et al. Citation2020, 4).

Both Wright (Citation2005) and Høeg (Citation2023) have discussed the cemetery as a space. Wright considers the contrast between the physical place of the cemetery, and the sacred, ritual space it becomes when transformed into a rhetorical memory space (Citation2005, 69). Høeg (Citation2023, 3) further observes that

the significance of cemeteries comprises concepts related to the collective. Cemeteries are more than private places on one and the same plot; they are also a collective of living and dead, or […] physical areas which have been transformed into social spaces.

The notion of space is not unequivocal, however (Auer et al. Citation2013, 1; Heller Citation2013, 604; König Citation2013, 104), and we here choose to understand linguistic space as corresponding to the different linguistic practices. These practices naturally follow from the different groups buried in the studied cemeteries and individuals for whom their language of origin is used in the inscriptions on the tomb, alone or with another code, and they are not physically organised together in different linguistic or national areas. Regardless of language, tombstone inscriptions usually follow a similar pattern: recurring units are the giving of name of the deceased, the relevant dates (and sometimes place) of birth and death, and some additional information such as a biblical verse or a few words from the family, or yet again a ritual phrase that may also be in Latin. These units are visually connected and framed by the tomb itself, sometimes completed by a commemorative plaque or surrounded by a small iron fence, together forming a ‘holistic space’ (Meletis and Dürscheid Citation2022, 67) where written language is displayed. It is within this space that different aspects of it may be discussed, e.g. language choice, writing system or script choice.

Methodological and theoretical considerations

We will here build on the notion of linguistic landscape with an informational and a symbolic function (Landry and Bourhis Citation1997), while supplementing this with the notions of multilingual spaces (Blommaert, Collins, and Slembrouk Citation2005) and multilingualism in written discourse as discussed by Sebba (Citation2012a; Citation2012b; Citation2012c; Citation2015). Therefore, ‘[t]he focus of our data is the collection of LL items within an expanded view’ (Waksman and Shohamy Citation2010, 63), allowing not only for the analysis of single epitaphs, but also of other signs than those inscribed on tombstones. Thus, building on the concept of linguistic landscape, the inscriptions are seen as in sum forming a written multilingual text. This text can be studied at different levels: first, inscriptions and epitaphs on an individual grave. Then, on group level with inscriptions in the same language constructing a linguistic space corresponding to that linguistic practice, and, finally, the whole constituted by the different spaces building the multilingual cemetery. Hence, we will consider individual epitaphs written at different times for different persons, while also discussing how languages are displayed, and how the visitor may identify them.

The systematic gathering of the empirical data took place in early January 2022, taking photographs and making field notes, starting in the oldest parts and following the chronological development of the two cemeteries, literally climbing upwards the hill towards the more recent graves. The tombstones that constitute the starting point to this study are those deemed relevant, viz. those who illustrate historical presence of multilingualism in different ways against a general French background: multilingual tombstones, tombstones with other writing systems and scripts, monolingual inscriptions in languages other than French.

It is a delicate task to ascertain how representative a single grave is on a more general level, since many choices (language, symbols etc.) prove idiosyncratic. Data relating to tombstones are also highly dependent on their state of preservation, while the validity of ensuing transcription of course also relies on the researcher’s accuracy when collecting them. However, regardless of carefulness, the data garnered will not be absolutely reliable, since the sources of potential errors are multiple: gravestones disintegrate and inscriptions gradually become illegible. Coulmas (Citation2009, 15) observes that when studying the historical linguistic landscape, the researcher ‘must make do with what is left’ (see (a and b)). This explains why some tombs sometimes simply have to be put aside, completely or partially, while others will be given more attention, depending on their legibility (see Meletis and Dürscheid Citation2023, 103).

The question of authorship can usually not be answered; even if inscriptions sometimes are signed with a name or indicate kinship, thus endorsing agency, this is only rarely the case. All these limiting factors conspire to make attempts at quantification futile and speak in favour of a more holistic perspective, as well as of an inductive, interpretative approach drawing on particular observations and on Gee’s conception of situated meaning ([Citation2011] Citation2014, 157–161).

Written multilingualism in the cemetery

Iconicity in writing

To recognise the written language, the visitor is left with one option: s/he has at least some rudimentary reading competence, or ‘recognizing competence’ (Blommaert and Backus Citation2013, 18), which makes it possible to identify the language in question. As Angermayer (Citation2012, 256) observes, ‘most languages are strongly tied to particular writing systems, as standard orthographies produce recognizable visual forms for them’, which in turn implies that in the cemetery, a language can be identified by a visitor who doesn’t have a corresponding speaking competence. Hence, graphic elements (letters and combination of letters) may serve to index a specific language. Both Spitzmüller (Citation2012, 261) and Sebba (Citation2015) identify graphemes signalling Germanness (<ß>, <ö> and <ü>). Some inscriptions can be characterised as ‘language neutral units’ (Sebba Citation2012a, 108). These are inscriptions with only a name and the dates when indicated only by numerals (figures), and do not include a text in a specific language. But the name of the departed may give some information: an Italian surname (ending with a vowel) and a French first name possibly indicates a local origin, a name with a <k> possibly brands an Anglo-Saxon origin, and a <w> may might index a Polish or English connection. (See Sebba Citation2015, 219.) Differences between languages’ writing and spelling systems are clearly observable, Sebba (Citation2007, 97) states: ‘A familiar example is the preference of Germanic languages for <k> where Romance languages prefer <c>’, and concludes that the ‘tendency of orthography to become a marker of identity is beyond question’ (Citation2007, 160–161). Coulmas (Citation2016, 41) points out that ‘writing systems have a formative influence of their users’ conception of language' and observes that French ‘deep’ orthography is distinguished from the Italian ‘shallow’ one by its more ‘indirect spelling – sound correspondence’.

In the inscriptions, the iconicity of different letters or combinations of letters can index different languages and cultures: <gh>, <gi> and <gli> for Italian, <wh> and <th> for English, <k> and <ä> for German, and so on. On the other hand, the letter <w> is rather infrequent in French, which is indicated in an inscription for a Witold Bratkowski from Poland: the W is in fact two V:s, both in the first name and in the surname, the stone carver obviously being unaccustomed to this letter. A variation between the writing systems of two languages can be observed in the inscription in German for the family of Alfred Eichholtz, where the German word Familie has been inscribed as Famille in French (see (b)). Here, we can envision two different explanations. First, it can of course be a simple mistake, the stone carver being used to the French word and imprinting this. Secondly, it could be that the stone, which seems to be a separate part eventually assembled with the other sections of the monument, was already prepared as a standard to be used for any tombstone. Due to the visual similarity of Famille and Familie, it is possible that many visitors will not even notice the use of two different languages here.

The linguistic spaces will be characterised by distinctive features (letters or combinations of letters). Italian, a recurring language in the inscriptions, is identified by the final vowels: ‘The regular persistence of vowels at the end of every word […] is one of those features which serve most obviously to characterize Italian’ (Elcock [Citation1960] Citation1975, 477). Elcock ([Citation1960] Citation1975, 478) also mentions geminated consonants as typical, an element we find for example in the first name Maddalena, or in the surnames Perfetti, Salvatelli, or the Fratelli (brothers). The inscription for the family Marenco (see ) also reflects life in a border region ceded to France in 1861: two of the deceased (the parents) were born in what is now Italy and died in time in France, but the son who died as a young child must have been born in France. This latter circumstance is not inscribed, which implicitly emphasises the family’s moving – in effect – from Italy to France.

Table 1. Inscription in Italian for the Marenco family.

Each language is branded in different ways. The combination of the letters <wh> in an inscription (as in “Who died at Menton”) and <th> (as in “My flesh and my heart faileth; But God is the strength of my heart”) will index English, in Polish we will recognize the <ł> (as in the name Przeniosł) even if the same letter occurs in other alphabets, and the frequent letter <w> (as in the names Karnkowski, Chledowska). Not only script or writing systems index an origin and a language, but toponyms also give indications of the departed’s origin: places of birth like Berlin, Moscow or Warsaw are often inscribed and very likely to be recognised, whether written in Polish (Warszawa) and in the Roman writing system, or even in Cyrillic script (Москва). Already the letter <w> indexes non-Frenchness, which is visible in the inscription for a Witold Bratkowski, as already described above. This particular feature however seems to change and weaken with time: a family Lichnewsky has their surname written with a <w> for the earliest deceased persons, but later the spelling with <w> is changed to <v> (Lichnevsky) on a commemorative plaque, likely as an accommodation to a more Romance orthography (see ). According to Obojska (Citation2020, 334), this could be part of a ‘destigmatization strategy […] in order to facilitate own integration into the host society, diminish the experienced discrimination, avoid negative stereotyping […] but also express own identification with the imagined host communities’, thus illustrating the possible ambiguity in an assimilation process implying a wish to belong and not belong at the same time. Bursell (Citation2012, 476) chooses to characterise this kind of phenomenon as pragmatic assimilation that intends to ‘achieve social recognition’, challenge or cope with the stigma, which ‘facilitates interaction with the majority group’ (Citation2012, 471, 484).

In parallel, we can observe that a connection to Russia, which is explicit since the city ‘Moscou’ is mentioned in the inscription, is completed with a link to France, since double names for two married women are a combination of a French and a Russian name. This is also very clear when it comes to Italian surnames, which is apparent when the first name is French, but the surname, less likely to be changed unless for married women, will remain Italian (e.g. Fernand Revelli, Jules Lorenzi).

Script shifts from the Cyrillic to the Roman script can be observed, e.g. in the inscriptions for the Russian surnames Grigorieff and Stchetinine, thus generating a loss of iconicity. Here, no other information apart from the names themselves indicates a Russian origin. The Cyrillic script is for some reason dismissed and the Russian devoiced sound for <в> in word-final position ([v]> [f]) in Grigorieff is transcribed <ff> in French and can be considered as a written adaptation to French. The language and script choice is reinforced by the name of the months in French, and the whole possibly signals a weaker Russian identity and a more definite shift from Russian towards French. We observe a similar change on the tombstone for a Baronne Anastasie Korff Née Michaïlova. Here too, the whole inscription is in French, the same for Baron Nicolas Korff. The first names are given in the French variant; the final sound in the surname is transcribed with <ff> and the biblical verse is quoted in French. (See .) We may consider these examples as adaptations or a strategy of the same kind as for Lichnevsky (see above) and the inscription for Marguerite Kovalenko described by Vajta (Citation2020, 301–302), and as a testimony of integration into a new national context.

Table 2. Epitaphs showing a likely accommodation from Russian to French.

Multilingualism on tombstones

Language alternation on the same tomb is infrequent but nevertheless proves to occur on occasion. It then invariably takes place between the units, not within a unit. For instance, the language shift from Italian to French between two generations of a family can be observed, when the information about the older generation is in Italian, but when the younger generation formulates itself in French (see ). In this case, agency is linked to the children who write about the deceased as ‘notre cher père’ who passed away in 1947, whereas the inscription for the mother, where agency is to be connected with the same father and children, is in Italian. They chose Italian for the mother in the family, but when the father died in turn, the children’s choice for him was French. So, although the years of death are rather close, the language shift takes place between the parents’ generation (Isaia and Isabella) and their children’s generation.

Table 3. Bilingual inscription in Italian and French.

The cosmopolitan history of Menton during the nineteenth century is apparent both at the cemetery level, with gravestones in different languages, and on individual graves testifying to a life journey which included changing languages. For a person born in Schweidnitz (Ferdinand Gustav Studt), in formerly German-speaking Lower Silesia, an inscription in German where the original <ö> is replaced by <oe> (‘Die Liebe hoeret nimmer auf’) dominates the monument (see and ). Below this, there is information imparted in French: ‘Ici reposent deux citoyens américains’ (i.e. husband and wife) and at the bottom, the inscription is in English, telling the visitor that the departed lived forty years in New York but died in Menton. Finally, the last sentence is once again in German. Seen symbolically, oscillating back and forth from German to English to German again, this epitaph likely forms a parallel with the person in question’s life. The linguistic repertoire used in the inscription is linked to what Busch (Citation2017) calls Spracherleben, i.e. ‘the lived experience of language’, demonstrated here by the life trajectory of the deceased who was born in one place (Schweidnitz, a formerly German town, now Polish), moved to the USA and then eventually Menton (see also Blommaert Citation2009). Alternation in the inscription takes place between the different units, and the epitaph displays an example of complementary multilingualism (Sebba Citation2012a, 108–109).

Table 4. Multilingual inscription for Ferdinand Gustav Studt (see ).

Variants with parallel multilingualism displaying a message in Polish and French are also attested, for example on a couple of gravestones with the Polish text above the French, marking an emotional priority of Polish above French at life’s end. As Scollon and Wong Scollon (Citation2003, 120) observe when discussing code priority, ‘the preferred code is located above the secondary or peripheral code’. In one case the epitaph communicates the same information about the deceased in both languages. On another tombstone (see and ), the French variant, also below the Polish, is less explicit than the Polish and relates the dates of birth and death for Felicie Macewicz, born in Poland. The text in Polish is more explicit: it gives the woman’s whole Polish name, the name of the village where she was born (‘BUZOWE POW KIJOWSKIM’, i.e. Buzowe close to Kiev) and completes the inscription with a call to the angels.

Table 5. Bilingual inscription for Felicie Macewicz (see ).

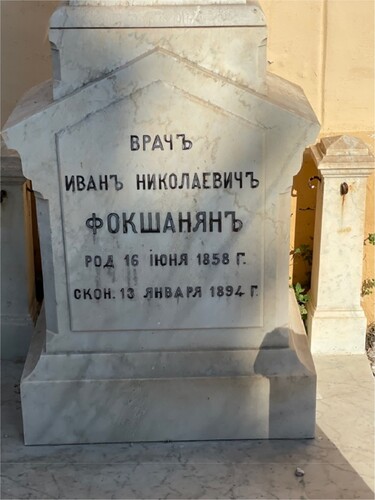

We see examples of the different kinds of signs distinguished by Backhaus (Citation2007, 90–103): monophonic signs or epitaphs, here inscriptions in one language, whether French or other; polyphonic inscriptions, i.e. signs in two or more languages (as for Ferdinand Gustav Studt, see ), where the text is not referentially equivalent; and homophonic inscriptions, i.e. signs in more than one language where the different texts are (more or less) equivalent. Finally, the overall change from the oldest parts of the cemeteries to the most recent sections should be commented upon: the older parts (nineteenth century) comprehend many monolingual or monophonic tombs, which appear to be more frequent than homophonic or polyphonic ones. These monophonic tombs display many different languages, most often French, for obvious reasons, but also in Russian and in the Cyrillic script (see for the physician ИВАНЪ НИКОЛЕВИЧЪ ФОКШАНЯНЪ, Ivan Nikolaevič Fokšanjan).

Russian is frequent to the extent that part of the Cimetière du Château is sometimes called the Russian cemetery (also because of the orthodox chapel with its characteristic golden cupola; see ). Many of these departed were young adults, in their twenties, old enough to be sent away from home to the Riviera and Menton where they were expected to recover from tuberculosis and other diseases, but all too often didn’t survive. English is also frequent, while other languages that occur are Italian, to some extent also German and Polish, more rarely Danish, Swedish and Dutch, and on occasion yet another language which is then considered as a hapax, for example Frisian or Romanian. But the higher up the hill, i.e. the closer we get to the recent parts, the more monolingually French the graves prove to be. We can physically track the process leading over time from the nineteenth century, when Menton was a cosmopolitan town with an Occitan vernacular, to the loss of its role as a health centre, in parallel with a language shift from (written) Italian (and oral Occitan) to French.

Linguistic spaces challenging French

The Tirailleurs

As mentioned earlier, the Trabuquet is also a war cemetery, with five Carrés where the gravestones of soldiers killed materialise events during the First World War. Even if the Carrés are clearly delimited, with their own entrances, they are at the same time part of the bigger cemetery, thus constituting a cemetery within the cemetery. The Carrés contribute to a collective consciousness about war and soldiers, especially the Memorial for the ‘Tirailleurs’ to whom also several posters with illustrations and texts explaining who they were, are displayed. Ben-Rafael (Citation2016, 207) defines a memorial as ‘a structure that commemorates in the public space, persons or events that are deemed to require remembrance’. This Memorial is akin to an open-air museum, including and defining a marginalised group of soldiers, who were recruited from the French colonies in Africa, often by force, mostly in Senegal but also in e.g. Madagascar (Mourre Citation2018, 520). These soldiers were buried in a mass grave and summarily ignored as individuals until some ten years ago, when their bodies were finally identified. They were ensuingly granted a sepulture, and a Memorial monument was erected to their joint memory. The relevant Memorial both defines and pays attention to the group of the Tirailleurs, and speaks to the visitors, contributing to a collective memory and consciousness about war and colonisation, and advocating for racial justice. As Benjamin (Citation2021, 14) notes, memorials are politically charged spaces, and in the case of the Tirailleurs, it raises the memory of not only the infantrymen in question, but of France’s colonial behaviour in the past.

The graves of the Tirailleurs are simple, as for all the other soldiers: a cross for Christians, and the moon sickle for Muslims, then a name, the date of birth and death, or only the year of death, and finally the phrase ‘Mort pour la France’. (See (a and b).) They look very similar, which underlines their collective aspect. The inscriptions are all in French, regardless where the departed came from. For the Tirailleurs, only the names, clearly of African origin, signal that they originated from another place: Houissou, Boubo Coulibaly, Kalifa Bamba, Konaté Bakary, Taraoré Teuremba, and many others. African naming practice structures the space linguistically, but this is undeniably questioned by the epitaph reiterated on all graves: ‘Mort pour la France’. This last message on their grave is in French; they are hence deprived of their own language which is replaced by the language of the coloniser and of the French Métropole, and their name is their last linguistic sign of another belonging. Shelby (Citation2015, 260), referring to Antoine Prost (Citation1977), observes that ‘to adopt the inscription Morts pour la France was to accept the language of the state, and not that of local tradition’. National French and ‘the coloniality of language’ (Deumert Citation2021) take over and the state takes final linguistic advantage of its position of power, maintaining the established hierarchy between the coloniser and the colonised. The place dedicated to the Tirailleurs becomes a space structured by a common war experience beyond the African connection. It is a formalised and conventionalised space, visible and delimited, with a name, and a symbolic significance (see Löw Citation2008, 42): the memory of these marginalised soldiers will be maintained through the public memory space/place dedicated to them, allowing them to become ‘a part of public memory’ (Wright Citation2005, 71). But even if the memorial intends to mark a final recognition to the Tirailleurs, ‘collective memory and remembrance may also be arenas of conflicts of political interests, clashes of ideologies or antagonisms of religious beliefs’ (Ben-Rafael Citation2016, 207). The meaning of a memorial is neither decided nor given once and for ever, but may change, evolve, elaborate different possibilities of interpretation, and its message may even contest and contradict the intention of its architect, which here was to pay tribute to the Tirailleurs (see Blackwood and Macalister Citation2020; Woldemaram Citation2016). As a result, the memorial of the Tirailleurs publicly questions France’s historical actions as a coloniser also on the linguistic level. It certainly encompasses a paradox, intending to show recognition and acknowledgment to the Tirailleurs while at the same time depriving them of their language. Here, French becomes ‘the violently imposed language’ (Deumert Citation2021, 104), imposed in successive steps of violence: first through colonisation, then by death at war for the coloniser, and finally by replacing African language by French on the grave.

Reminding of a former regional vernacular

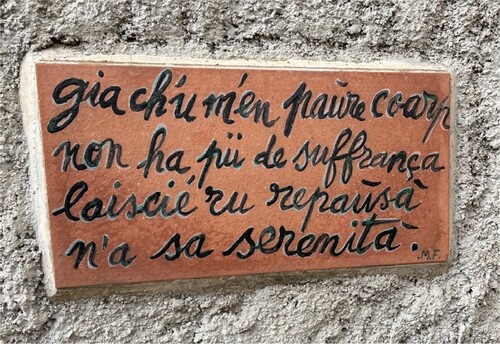

Here and there in the Cimetière du Château, we find plaques with a short text in Occitan (see ). The plaques in question are spread out over the cemetery, connected by a language that is not displayed elsewhere yet which unites them in a joint linguistic space. They are neither a necessary nor an expected message, contrary to the epitaphs, but they have been displayed because the municipality allowed them to be. Each plaque is solidly fastened on a wall with concrete, as if the language was steadfast and still a viable choice. However French regional languages have been disputed and contested ever since the Revolution and the influence of Abbé Grégoire (see e.g. Achard Citation1987; de Certeau, Julia, and Revel Citation1975). Since then, French language policy has furthered French, and the Constitution states in its second article that French is the language of the Republic, whereas regional languages are mentioned as part of French cultural heritage (patrimoine) in article 75. Historically, French authorities have fought against regional languages such as e.g. Breton, Occitan and Corsican, and promoted French as the common language of the indivisible Republic. (See Ager Citation1999; for a discussion on the regional languages in the French Constitution, see e.g. Giordan Citation2008; Malo Citation2011; Viaut Citation2020.) Besides, it is here worth noticing that France has signed but not ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, implying that there is no obligation to e.g. permit spelling a toponym in a minority language or to authorise spelling a patronym in a regional variety. This was recently confirmed when the French Constitutional Council (Conseil Constitutionnel) amended the Loi Molac from 2021, thus limiting education in regional languages as well as the use of diacritics specific to them in official identity documents (Décision n° 2021-818 DC du 21 mai Citation2021. See also Le Monde 21 May Citation2021). Even if there has been some degree of revival for regional languages during the last few decades, they are generally not spoken, and their presence remains controversial and provocative. Signage in Occitan introduced within a French matrix language frame (Gardner-Chloros Citation2009, 100–104; Myers-Scotton Citation1993) in a public space might therefore rather be considered as symbolic, or even as exoticism (Coupland Citation2012) and the result of a folklorisation process, in other words of an action that doesn’t have any real and meaningful impact other than reminding of a specific linguistic past (which certainly might be interesting for the tourists, while meaningful to select locals).

Nevertheless, Occitan can be perceived as visibly intrusive since it reminds of the possibility of another historical linguistic reality than monolingual French, and this more than other national languages in the graveyards. Occitan is not used in any observed epitaph, only for these written signs. The scope of the social action implicated by these signs then becomes more controversial: while other languages like English or German don’t compete with French and don’t claim to be used in France in an official way, only in private communication in epitaphs, the signs in Occitan can be seen as more blatant and semi-official. While there is no official agent endorsing the utterance named, thus designating responsibility, the plaques could certainly not be placed where they are now without approval of the mayor and the local authorities in charge of the cemetery. This situates them higher up on the top-down scale, conferring upon them both authority and legitimacy (Gorter Citation2006, 3) – they cannot be ignored.

The Occitan plaques transmit a message that is not entirely inaccessible if you know French, since many words are similar in French and Occitan, though the two varieties are not mutually intelligible. The plaques can be interpreted as a way of reclaiming, at least symbolically, the original Occitan (Mentonasc) spoken in the region, which has over time been obliged to cede to the national standard French. The local language contrasts not only with the information at the entrance of the cemetery, rendered only in French, but also with the inscriptions on the gravestones, made in a standard language, be it French, Italian or English or another one. But even if the content of the message cannot be understood by the visitor, this doesn’t really matter. What matters is the fact that the message is visibly in Occitan, not in French. To paraphrase Kelly-Holmes (Citation2005, 21), the message in Occitan is ‘not telling the individual addressee anything in [Occitan] it is instead telling him/her something about [Occitan]. Its symbolic nature takes precedence over its referential or informative nature’. This is in fact confirmed by the content of the short messages – sententious, general phrases, rather innocent texts.

Concluding remarks

Written linguistic practices structure the cemetery as a multilingual space, implying a multiscriptal, parallel multilingualism. Here, language is silent, and its visibility is crucial. The epitaphs are composed for an audience that is not necessarily competent in the different languages on display. Even if the visitor does not have the linguistic competence to specifically interpret the inscription in another language or script, a general message will nevertheless be transmitted, namely, that here rests a person asserting another identity than French.

Within the French matrix language frame, there is a lot of code-mixing taking place, also enhanced by script mixing. The visitor is reminded that French is today the firm base for language use in France, but the tombs with epitaphs in several other languages and the occurrence of Italian, English, Russian, German, Danish among others, reflect a former multilingual community in Menton as well as a historic proximity to Italy. The more recent the graves are, the more they will prove to be marked in monolingual French. Multilingualism in the studied cemeteries is hence to be seen as the result of historical processes and social practices: remaining Occitan and Italian influence in a border region that has been integrated into France some 160 years ago, English, Russian and other linguistic traces, all due to the variegated history of Menton. The linguistic practices are parallel, connected within the same linguistic space, and altogether they make the cemetery into a multilingual place. The different languages are not reduced to a specific area in the cemetery, a material place for each, but interconnected all over it, thus linking graves and epitaphs in the same language and building linguistic spaces. The information in the cemetery is complementary, in the sense that different tombs yield different sorts of information. Yet, taken altogether, they provide a multilingual text to the visitors where clear changes can be observed, e.g. in spelling and in names. An inscription will most often be monolingual, but also multilingual epitaphs occur, mirroring the life journey of the deceased. Moreover, within a linguistic space, we can observe changes in language choices and in spelling indicating a tendency to integrate with France and to accommodate to French.

Considering the cemetery as a rhetorical space also entails the obligation to consider what message the ‘voices clamoring to be heard’ are straining to transmit (Wright Citation2005, 60). These voices refuse to be silenced, since many of the older graves are plots granted in perpetuity, war memorials are likely to remain for a long time and more recent voices like texts in Occitan and the Tirailleurs join the choir. It is here that the heterotopia intervenes: they in sum reflect both local and French history, and, challenging monolingual French, they invert the cemetery into a stratified multilingual place/space (Wright Citation2005). Here, layered meanings evolve: ‘meanings are elastic’, Colwell (Citation2022, 129) states. Older layers from the time when Menton was a health centre and a tourist town fade away and inscriptions in Italian lose significance, ‘overwritten’ by newer spaces. The cemeteries in this study turn into a spatial palimpsest, where the more recent layers are likely to diminish the importance of the older ones (see Bendl Citation2020, 264, 267). While the reign of French as national language is made manifest, colonisation and linguistic hegemony can be seen as implicitly questioned or at least reminded of via the infusions of vernaculars and mixes. The cemeteries can indeed be seen as forming a heterotopia, in Foucault’s sense, i.e. a place that invariably contradicts, contests and inverts, ‘exer[ting] a sort of counteraction’.

We move from the individual graves to the collective of the whole cemetery, jumping ‘from one scale to another’ (Blommaert Citation2007, 4) in different linguistic hierarchies, from the individual tomb to a linguistic space invested with agency and the power to question French hegemony. This is remarkable not least for the Carré des Tirailleurs. The cemeteries display a text with discourses that call French hegemony into question and implicitly contest past actions like wars and colonisation and explicitly differ from the norm of French monolingualism. These spaces become agentive and ‘actions and meanings can be generated’ (Blommaert Citation2013, 15) – they create new histories, verbally, visually and symbolically (see Huebner and Phoocharoensil Citation2017, 109). Taken together, the cemeteries constitute a multilingual space where French today has become prevalent, but is also challenged by older tombs with inscriptions in many other languages, and most importantly by the spaces of the Tirailleurs and of the historical vernacular Occitan.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Achard, P. 1987. “Un idéal monolingue.” In France, pays multilingue Tome 1. Les langues en France, un enjeu historique et social, edited by G. Vermes and J. Boutet, 38–57. Paris: L’Harmattan.

- Ager, D. 1999. Identity, Insecurity and Image: France and Language. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Aitchinson, J. 2012. “Diachrony vs Synchrony: The Complementary Evolution of Two (Ir)Reconcilable Dimensions.” In The Handbook of Historical Sociolinguistics, edited by J. M. Hernández-Campoy and J. C. Conde-Silvestre, 11–21. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Angermayer, P. S. 2012. “Bilingualism Meets Digraphia. Script Alternation and Script Hybridity in Russian–American Writing and Beyond.” In Language Mixing and Code-Switching in Writing. Approaches to Mixed-Language Written Discourse, edited by M. Sebba, S. Mahootian, and C. Jonsson, 255–272. New York: Routledge.

- Auer, P., M. Hilpert, A. Stukenbrock, and B. Szmrecsanyi. 2013. “Integrating the Perspectives on Language and Space.” In Space in Language and Linguistics. Geographical, Interactional and Cognitive Perspectives, edited by P. Auer, M. Hilpert, A. Stukenbrock, and B. Szmrecsanyi, 1–17. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Backhaus, P. 2007. Linguistic Landscapes. A Comparative Study of Urban Multilingualism in Tokyo. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Ben-Rafael, E. 2016. “Introduction [Special Issue on Monuments and Memorials].” Linguistic Landscape 2 (3): 207–210. https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.2.3.001int.

- Bendl, C. 2020. “Appropriation and Re-Appropriation: The Memorial as a Palimpsest.” In Multilingual Memories: Monuments, Museums and the Linguistic Landscape, edited by R. Blackwood and J. Macalister, 263–284. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Benjamin, E. 2021. “Places and Spaces of Contested Identity in the Memorials and Monuments of Paris.” Modern & Contemporary France 29 (1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639489.2020.1784859.

- Blackwood, R., and J. Macalister. 2020. “Introduction.” In Multilingual Memories: Monuments, Museums and the Linguistic Landscape, edited by R. Blackwood and J. Macalister, 1–10. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Blommaert, J. 2007. “Sociolinguistic Scales.” Intercultural Pragmatics 5 (1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1515/IP.2007.001.

- Blommaert, J. 2009. “Language, Asylum, and the National Order.” Current Anthropology 50 (4): 415–441. https://doi.org/10.1086/600131.

- Blommaert, J. 2013. Ethnography, Superdiversity and Linguistic Landscapes. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Blommaert, J., and A. Backus. 2013. “Superdiverse Repertoires and the Individual.” In Multilingualism and Multimodality: Current Challenges for Educational Studies, edited by I. de Saint-Georges and J.-J. Weber, 11–32. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Blommaert, J., J. Collins, and S. Slembrouk. 2005. “Spaces of Multilingualism.” Language & Communication 25 (3): 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2005.05.002.

- Bursell, M. 2012. “Name Change and Destigmatization among Middle Eastern Immigrants in Sweden.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 35 (3): 471–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2011.589522.

- Busch, B. 2017. “Expanding the Notion of the Linguistic Repertoire: On the Concept of Spracherleben – the Lived Experience of Language.” Applied Linguistics 38 (3): 340–358.

- Colwell, C. 2022. “A Palimpsest Theory of Objects.” Current Anthropolgy 63 (2): 129–157. https://doi.org/10.1086/719851.

- Coulmas, F. 2009. “Linguistic Landscaping and the Seed of the Public Sphere.” In Linguistic Landscape. Expanding the Scenery, edited by E. Shohamy and D. Gorter, 13–24. New York: Routledge.

- Coulmas, F. 2016. “Prescriptivism and Writing Systems.” In Prescription and Tradition in Language: Establishing Standards Across Time and Space, edited by I. Tieken-Boon van Ostade and C. Percy, 39–56. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. Channel View Publications.

- Coupland, N. 2012. “Bilingualism on Display: The Framing of Welsh and English in Welsh Public Spaces.” Language in Society 41 (1): 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404511000893.

- Courrière, H. 2010. “L’entrée dans la modernité.” In Histoire de Menton, edited by J.-P. Pellegrinetti. Toulouse: Privat. Accessed July 6, 2022. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03644145/document.

- Cuturello, P. 2002. “Cosmopolitisme et identité locale. Touristes hivernants et société locale sur la Côte d’Azur au début du XXe siècle.” Cahiers de l’Urmis. Accessed July 6, 2022. https://journals.openedition.org/urmis/20.

- Dalbera, J.-P. 1994. Les parlers des Alpes-Maritimes. Étude comparative. Essai de reconstruction. Londres: Association internationale d’études occitanes.

- de Certeau, M., D. Julia, and J. Revel. 1975. Une politique de la langue. La Révolution française et les patois: l’enquête de Grégoire. Paris: Gallimard.

- Décision n° 2021-818 DC du 21 mai 2021. La loi relative à la protection patrimoniale des langues régionales et à leur promotion. Accessed August 24, 2022. https://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/decision/2021/2021818DC.htm.

- Deumert, A. 2021. “Insurgent Words: Challenging the Coloniality of Language.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 2021 (272): 101–126. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2021-2125.

- Eckert, E. 2001. “Gravestones and the Linguistic Ethnography of Czech-Moravians in Texas.” Markers XVIII:146–187.

- Elcock, W. D. (1960) 1975. The Romance Languages. London: Faber & Faber Limited.

- Foucault, M. 1986. “Of Other Spaces.” Diacritics 16 (1): 22–27. https://doi.org/10.2307/464648. Accessed July 18, 2022. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/464648.pdf?casa_token=6LjQYzKVnfsAAAAA:z8u1-GonKdVxujM8z4SPp2hFDAx-hyzMDzp6GQN4_g4YiChwVZcGj3X7feaYiYh6zEI33BMjVCl9BnGNpeDZ3PP_O3ay43wW38dq7RmZtBqX1jFe.

- Francis, D. 2003. “Cemeteries as Cultural Landscapes.” Mortality 8 (2): 222–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/1357627031000087442.

- Gardner-Chloros, P. 2009. Code-Switching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gee, J. P. (2011) 2014. How to do Discourse Analysis. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Giordan, H. 2008. “Les langues régionales dans la Constitution: un pas en avant très ambigu.” Diasporiques 3 (nouvelle série): 25–30.

- Gorter, D. 2006. “Introduction. The Study of the Linguistic Landscape as a New Approach to Multilingualism.” International Journal of Multilingualism 3 (1): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790710608668382.

- Guide juridique. 2017. Guide juridique relative à la législation funéraire à l’attention des collectivités territoriales. Ministère de l’Intérieur. Accessed May 23, 2023. https://www.collectivites-locales.gouv.fr/files/Compétences/2.%20agir%20pour%20ma%20population/funeraire/guide-collectivites-aout-2017.pdf.

- Hammel, E. 2012. “Situation socio-linguistique de l’Occitan.” Europa Ethnica 69 (3–4): 70–77. https://doi.org/10.24989/0014-2492-2012-34-70.

- Heller, M. 2013. “Commentary: Making Space.” In Space in Language and Linguistics. Geographical, Interactional and Cognitive Perspectives, edited by P. Auer, M. Hilpert, A. Stukenbrock, and B. Szmrecsanyi, 602–604. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Herat, M. 2014. “The Final Goodbye: The Linguistic Features of Gravestone Epitaphs from the Nineteenth Century to the Present.” International Journal of Languages Studies 8 (4): 127–150.

- Høeg, I. M. 2023. “Solid and Floating Burial Places. Ash Disposal and the Constituting of Spaces of Disposal.” Mortality 28 (1): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576275.2020.1869707.

- Huebner, T., and S. Phoocharoensil. 2017. “Monument as Semiotic Landscape.” Linguistic Landscape 3 (2): 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.3.2.01hue.

- Jedan, C., S. Kmec, T. Kolnberger, and M. Westendorp. 2020. “Co-Creating Ritual Spaces and Communities: An Analysis of Municipal Cemetery Tongerseweg, Maastricht, 1812–2020.” Religions 11:435. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11090435. Accessed August 13, 2022. https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/11/9/435.

- Kelly-Holmes, H. 2005. Advertising as Multilingual Communication. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- König, E. 2013. “Commentary: The Notion of Space in Linguistic Typology.” In Space in Language and Linguistics. Geographical, Interactional and Cognitive Perspectives, edited by P. Auer, M. Hilpert, A. Stukenbrock, and B. Szmrecsanyi, 101–104. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Kremnitz, G. 2017. “Situation de l’occitan en 2017. Une esquisse.” Europa Ethnica 74 (1–2): 9–16. https://doi.org/10.24989/0014-2492-2017-12-9.

- Landry, R., and R. Y. Bourhis. 1997. “Linguistic Landscape and Ethnolinguistic Vitality. An Empirical Study.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 16 (1): 23–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X970161002.

- Le Monde. 2021. “Le Conseil constitutionnel censure partiellement la loi sur les langues régionales.” May 21. Accessed August 24, 2022. https://www.lemonde.fr/politique/article/2021/05/21/le-conseil-constitutionnel-censure-partiellement-la-loi-sur-les-langues-regionales_6081030_823448.html.

- Lefèbvre, H. 2000. La production de l’espace. Paris: Anthropos.

- Löw, M. 2008. “The Constitution of Space. The Structuration of Spaces Through the Simultaneity of Effect and Perception.” European Journal of Social Theory 11 (1): 549.

- Malo, L. 2011. “Les langues regionals dans la Constitution française: à nouvelles donnes, nouvelle réponse?” Revue française de droit constitutionnel 85 (1): 69–98. https://doi.org/10.3917/rfdc.085.0069.

- Meletis, D., and C. Dürscheid. 2022. Writing Systems and Their Use. An Overview Over Grapholinguistics. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

- Mourre, M. 2018. “African Colonial Soldiers, Memories and Imagining Migration in Senegal in the Twenty-First Century.” Africa 88 (3): 518–538. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0001972018000207.

- Myers-Scotton, C. 1993. Duelling Languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mytum, H. 1994. “Language as Symbol in Churchyard Monuments: The Use of Welsh i Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Pembrokeshire.” World Archeology 26 (2): 252–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.1994.9980275.

- Obojska, M. 2020. “What’s in a Name? Identity, Indexicality and Name Change in an Immigrant Context.” European Journal of Applied Linguistics 8 (2): 333–553. https://doi.org/10.1515/eujal-2020-0004.

- Prost, A. 1977. Les anciens combattants. Paris: Gallimard.

- Reimers, E. 1999. “Death and Identity: Graves and Funerals as Cultural Communication.” Mortality 4 (2): 147–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/713685976.

- Rugg, J. 1998. “A Few Remarks on Modern Sepulture. Current Trends and New Directions in Cemetery Research.” Mortality 3 (2): 111–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/713685888.

- Rugg, J. 2000. “Defining the Place of Burial: What Makes a Cemetery a Cemetery?” Mortality 5 (3): 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/713686011.

- Rugg, J. 2003. “Introduction: Cemeteries.” Mortality 8 (2): 107–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/1357627031000087361.

- Scollon, R., and S. Wong Scollon. 2003. Discourses in Place. Language in the Material World. London: Routledge.

- Sebba, M. 2007. Spelling and Society. The Culture and Politics of Orthography Around the World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sebba, M. 2012a. “Multilingualism in Written Discourse: An Approach to the Analysis of Multilingual Texts.” International Journal of Bilingualism 17 (1): 97–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006912438301.

- Sebba, M. 2012b. “Researching and Theorising Multilingual Texts.” In Language Mixing and Code-Switching in Writing. Approaches to Mixed-Language Written Discourse, edited by M. Sebba, S. Mahootian, and C. Jonsson, 1–26. New York: Routledge.

- Sebba, M. 2012c. “Orthography as Social Action: Scripts, Spelling, Identity and Power.” In Orthography as Social Action: Scripts, Spelling, Identity and Power, edited by A. Jaffe, J. Androutsopoulos, M. Sebba, and S. Johnson, 1–19. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Sebba, M. 2015. “Iconisation, Attribution and Branding in Orthography.” Written Language & Literacy 18 (2): 208–227. https://doi.org/10.1075/wll.18.2.02seb.

- Shelby, K. D. 2015. “National Identity in First World War Belgian Military Cemeteries.” First World War Studies 6 (3): 257–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/19475020.2016.1174589.

- Spitzmüller, J. 2012. “Floating Ideologies: Metamorphoses of Graphic ‘Germanness’.” In Orthography as Social Action: Scripts, Spelling, Identity and Power, edited by A. Jaffe, J. Androutsopoulos, M. Sebba, and S. Johnson, 255–288. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Vajta, K. 2018. “Gravestones Speak – But in Which Language? Epitaphs as Mirrors of Language Shifts and Identities in Alsace.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 39 (2): 137–154.

- Vajta, K. 2020. “Names on Alsatian Gravestones as Mirrors of Politics and Identities.” Nordic Journal of English Studies 19 (5): 288–310.

- Vajta, K. 2021. “Identity Beyond Death. Messages and Meanings in Alsatian Cemeteries.” Mortality 26 (1): 17–35.

- Viaut, A. 2020. “De « langue régionale » à « langue de France » ou les ombres du territoire.” Glottopol 34:46–56.

- Waksman, S., and E. Shohamy. 2010. “Decorating the City of Tel Aviv-Jaffa for Its Centennial: Complementary Narratives via Linguistic Landscape.” In Linguistic Landscape in the City, edited by E. Shohamy, E. Ben-Rafael, and M. Barni, 57–73. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Woldemaram, H. 2016. “Linguistic Landscape as Standing Historical Testimony of the Struggle Against Colonization in Ethiopia.” Linguistic Landscape 2 (3): 275–290. https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.2.3.04wol.

- Woodthorpe, K. 2009. “Reflecting on Death: The Emotionality of the Research Encounter.” Mortality 14 (1): 70–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576270802591228.

- Wright, E. A. 2005. “Rhetorical Spaces in Memorial Places: The Cemetery as a Rhetorical Memory Place/Space.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 35 (4): 51–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/02773940509391322.