ABSTRACT

The relationship between economy and language is thought to be key to language revitalisation efforts, although the nature of the relationship is often discussed only in general terms. Royles sets out to address this ambiguity by defining the different dimensions of this relationship, however the resultant framework is based on a limited body of evidence. Using the case of Wales, we undertake a systematic review of what is known about the impact of economic variables upon language, thus generating a wider body of evidence to verify Royles’ framework. Our investigation reveals that of the 15,414 references generated as part of the review, 73 were found to satisfy the search criteria and all of which were successfully allocated within Royles’ categories. In validating Royles’ framework we advance a new understanding of economic impact on minority languages by moving from general to definitive terms and suggest that the clarity that this provides can be utilised by policy practitioners in their efforts to halt language decline.

Introduction

According to Grin (Citation1996, 2), the connection between economy and language is indisputable, and this belief is shared by several other leading scholars (see Crystal Citation2002; Kaplan and Baldauf Citation1997; Williams Citation2000). Furthermore, as Lewis and McLeod note ‘economics has always been central to the prospects of minority languages’ (Citation2021, 260) and as such it is suggested that the relationship is key to language revitalisation efforts (Royles Citation2019, 3); a view shared by Welsh Government who connect economic and linguistic vitality in both their language and economic strategies (Citation2017a, Citation2017b). Indeed they note that ‘thriving local economies will support our target of one million Welsh speakers by 2050’ (Citation2017b, 21). However, it is argued by more than one party that the connection between economic and linguistic processes is typically discussed only in general terms (see Austin and Sallabank Citation2011; Grin Citation1996; Royles Citation2019).

Royles (Citation2019) set out to address this apparent ambiguity by attempting to define the different aspects of the relationship. Academic researchers from the arts, humanities and social sciences were joined by policy practitioners from the field to take part in a workshop exploring the different aspects of this key relationship (Royles Citation2019). A framework categorising the various dimensions of the relationship resulted. The main dimensions were defined thus: ‘how language variables can influence economic variables; how economic variables impact upon linguistic variables; and the indirect impact of economic factors on levels of language vitality (Royles Citation2019, 3). It was found, however, that there was limited evidence to explain the impact of economic processes upon language.

A similar conclusion is reached in a Rapid Evidence Assessment (REA) commissioned by the Welsh Government reviewing ‘the relationship between the Welsh language, and other languages relevant to the linguistic context in Wales, and the economy’ (Citation2020a, 4). The authors conclude that there is a tendency for previous research to focus on the influence of linguistic aspects on the economy (language > economy) noting that there is less evidence of the effect of the economy on language (economy > language) (Welsh Government Citation2020a, 84).

Returning to Royles’ framework, we argue therefore that it is based on limited evidence, that is the views and research of a select few academics and policy practitioners gathered together for a limited amount of time, and so the evidence on which the framework is based cannot be considered comprehensive. This critique could also be applied to Welsh Government’s REA, which by its very nature is a method designed to be indicative of the evidence available rather than exhaustive. We identify the need therefore to undertake a systematic review (SR), that is a more methodical and rigorous method (Shamseer et al. Citation2015), to investigate what is known about the direct and indirect impact of economic processes upon language variables to provide a stronger body of theoretical and empirical evidence in support of Royles’ framework. Whilst it is acknowledged that all aspects of the framework should eventually be verified, we argue that the need to assess the direct and indirect impact of economy on language is most pressing due to the focus of Welsh Government policy on this particular dimension of the economy/language relationship and that further evidence is urgently needed to support their policy rationale. This paper therefore focuses upon the (economy > language) dimension specifically.

This paper investigates:

What is known about the influence of economic policies, activities and trends on the Welsh language?

What are the gaps in knowledge that could form the basis of further research and how could they be responded to?

Using Welsh as an example, does Royles' (Citation2019) categorisation framework encompass everything that is known about the influence of economic policies, activities and trends on minority languages?

The Welsh language context

Wales is a bilingual nation with 538,300 (17.8%) of the population aged 3 years and over able to speak Welsh (ONS Citation2022). Despite a general decline in the language throughout the twentieth century, numbers appeared to stabilise around the turn of this century (Davies Citation2014). Legal reform in the shape of the Welsh Language Act 1993, which put Welsh on an equal footing with English (within the public sphere), alongside the growth in Welsh-Medium education are factors often attributed to the albeit temporary halt in decline (Davies Citation2014; Grin and Vaillancourt Citation1999). More recently, the Welsh Language Measure 2011 gave Welsh official status in Wales and saw the establishment of the role of Welsh Language Commissioner whose duties include promoting and facilitating the use of the Welsh language; however their regulatory powers are confined in the most part to the public sector (Vacca Citation2013). This said it is notable that by today Welsh Government consider the economy to be an important sphere for language revitalisation as they aim to nearly double the number of Welsh speakers by the middle of the century (Citation2017a, Citation2017b).

Methods

The SR was identified as a suitable method for meeting our research objectives as it facilitates the process of synthesising the results of previous studies in order to present what is known about a specific subject together with identifying gaps in knowledge that can form the basis for further research (Paul and Criado Citation2020). In addition, it reduces the risk of bias by offering a systematic and thorough framework for accessing, processing and presenting evidence (Shamseer et al. Citation2015). By allocating the studies within Royles’ categories new connections are made between the various aspects of the information. This, according to Jesson, Metheson, and Lacey (Citation2011), is one of the fundamental ways in which a SR ensures a contribution to knowledge.

Protocol

A protocol for this review was adapted a priori based on ‘Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA–P) 2015 statement’ by Moher et al. (Citation2015). Its content and use are reported here. The systematic review took place between January 2021 and February 2022.

Eligibility criteria

The key terms of the research questions were defined, and it was decided to include quantitative and qualitative studies in order to gather as much evidence as possible. Quality was ensured by rejecting references that were not primary research or academic work. The 1960s are generally regarded as a significant period in the development of the socio-linguistics field and so the search period was defined as from 1960 onwards, in line with that of the Welsh Government’s own REA (Citation2020a). The search was not restricted by language.

Information sources and search strategy

The sources of information were selected according to their likelihood of reporting on relevant areas. The initial search terms were adapted based on the search terms of The Welsh Language and the Economy REA (Welsh Government Citation2020a) and a strategy was developed for the ProQuest database initially, and then adapted for the Web of Science, Sage Journals and National Library of Wales databases. Mock searches were used to test the strategy and changes were made based on the results. Three keyword strings were decided upon, namely ‘language’, ‘economy’ and ‘context’. Keywords associated with leading sectors or influential trends within the field were added to the ‘economy’ category ().

Table 1. Example of a ProQuest database search string.

In addition to searching the databases named above, the Welsh Government and the United Kingdom Government websites were searched, and the Welsh Language Commissioner's office was contacted directly in order to access grey literature that would not likely be included in the databases. Towards the end of the process, journals, reference lists and specific reports were hand-searched to ensure thoroughness.

Study selection and data extraction

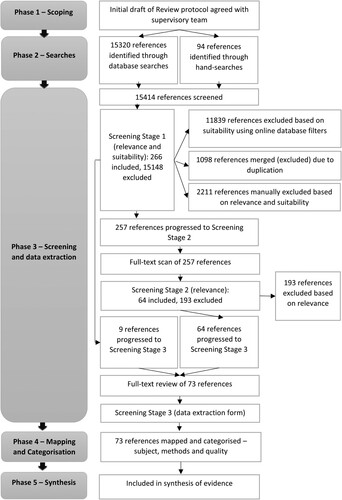

The flow chart below, adapted from Moher et al. (Citation2015) and Welsh Government (Citation2020a), illustrates the flow of information through the phases of the SR. Phases 1 and 2 of the SR were reported above (initial scoping and search), and therefore phase 3 will be addressed in this section, namely the screening and data extraction phase ().

There were 3 stages to phase 3, that is the screening and data extraction phase. During the first stage, online database filters and a manual screening process were used to screen a total of 15,414 references for their relevance and suitability to the study. A function within Zotero was used to identify and merge duplicates. 257 results were progressed to Stage 2 of the screening process and 9 results were progressed directly to Stage 3 as there was no ambiguity regarding their suitability or relevance.

A full-text scan was conducted of all studies that reached the second stage of the screening process. The first stage of screening was based on the title and abstract of the study only. The objective of the second stage was to check, where there was ambiguity, whether relevant conclusions to the basic question of this review are reported based on a whole text scan. 193 references were excluded where economic policies, activities or trends and the Welsh language are referred to, but the influence of one on the other was not investigated. 64 references where the influence of economic policies, activities and trends on the Welsh language are examined were carried forward to Stage 3.

A data extraction form was completed based on a full-text review of the 73 studies that reached the final screening stage to collect descriptive information, assess the quality and weight of the evidence, and summarise the findings of the references and their contribution towards the evidence base (Welsh Government Citation2020a, 16). The data extraction form was developed based on the work of the Welsh Government (Citation2020a, 92–97), which itself was based on previous reviews and guidance from reputable sources. Each study was scored based on three criteria: (i) the reference's contribution to answering the primary question of the Review; (ii) the appropriateness of the reference in relation to the question of the Review and (iii) the general validity of the methodology of each reference (Welsh Government Citation2020a, 95). All references that reached Stage 3 of the review were mapped and categorised and included in the synthesis.

Results

Mapping and categorising

The 73 references that reached Stage 3 of the review were mapped and categorised. Each reference reported on key conclusions linked to the influence of economic policies, activities and trends on the Welsh language. The objective of this step was to map the scope of the evidence, including the number of studies, the methods used and the quality of the evidence, within the categories developed by Royles (Citation2019).

Royles (Citation2019) recent framework categorises the main characteristics of the relationship between language and economy, including economic influences on language. By allocating the findings of this review within Royles’ categories it is possible to test the validity of the framework and assess the need for further development.

The main characteristics of the influence of economic dimensions on language were categorised by Royles as follows:

Category one is economic developments that are specifically associated with industries and activities that are directly related to a minority language and where the language may be a condition of employment. Examples of this category include cultural industries whose products are in a minority language and who operate in a minority language.

Category two are developments where the focus of the business does not directly relate to the minority language itself. However, the economic activity can impact upon the vitality of a minority language, due to decisions regarding the language(s) through which the business operates and/or the language(s) in which they provide services. An example where a development may promote linguistic vitality within this category is a legal firm that operates internally though the medium of the minority language and that provides services through the medium of that language.

Category three relates to larger scale economic developments that have no direct association with a minority language, but that can have a direct impact on its vitality. In contrast to category (i) the work is not directly related to a minority language, and in contrast to category (ii) there is no specific language policy in place for the workplace and activity being undertaken that can influence linguistic vitality. Nevertheless, the linguistic impact may be either due to the impact of the development in providing employment in a particular geographical area (eg. a linguistically significant area with a high density of language speakers), or in other types of locations as a consequence of employing a large workforce, where there is high or low representation of speakers of a minority language.

A fourth category is the indirect impact of economic factors on levels of language vitality. Economic processes and developments identified may stimulate either single or multiple processes of social, economic, and political change associated with globalisation that consequently impact upon regional and minority language vitality. The most evident factor in discussions to date is the indirect impact of economic variables upon linguistic vitality as a result of promoting and facilitating higher levels of mobility and (intranational or international, or outward) migration. (Royles Citation2019, 6–7)

Overview of the methods used by category

summarises the number of studies and the main method(s) used by category.

Table 2. The number of studies and the main method(s) used by category.

An overview of the quality of the evidence by category

This section offers an overview of the quality of the evidence by category.

The 73 references were assessed according to criteria of contribution, appropriateness, and validity, based on the criteria developed by the Welsh Government (Citation2020a, 25). Eleven references were not screened using the quality and weight of evidence criteria as it was decided that the criteria were not entirely suitable for these types of studies e.g. literature reviews.

summarises the number of studies and their overall score within each category.

Table 3. The number of studies and overall score by category.

In general, the Medium scores given to the studies were linked to their moderate contribution towards the evidence base and their low score in terms of appropriateness. The relatively higher scores are attributed to a more significant contribution to the evidence base and a higher appropriateness score. As is common with systematic reviews, appropriateness scores in this study favoured quantitative over qualitative studies. This highlights a problematic aspect of the methodology, in that qualitative studies are not afforded the same status. However, most of the studies performed well in terms of their individual validity.

Synthesis

The first objective of this SR is to assess what is known about the influence of economic policies, activities and trends on the Welsh language. The scope is therefore broad, and the types of study included too heterogeneous to allow for a quantitative analysis. In cases such as this, Petticrew and Roberts suggest that different methods of synthesis, such as narrative synthesis, may be more suitable (Citation2006, 164). That which is important is that the information is presented in a logical and meaningful way (Jesson, Metheson, and Lacey Citation2011; Petticrew and Roberts Citation2006).

It was therefore decided to deal with research questions 1 and 2 of this SR in turn. To address the first research question, the information is analysed thematically within the categories developed by Royles (Citation2019). In this way, the third research question is addressed concurrently as the validity of the categories are also assessed. Then, in response to the second research question, the information is synthesised across the categories, drawing attention to any gaps in knowledge that could be the basis for further research and considering how these gaps could be addressed.

What is known about the influence of economic policies, activities and trends on the Welsh language?

Category (i): industries and activities directly related to the minority language

This section summarises what is known about the influence of policies, activities and trends linked to industries that are directly connected with the minority language. Royles (Citation2019) posits cultural industries producing a Welsh language product as an example of this type of industry, and indeed, most of the sector specific references that satisfy the definition of this category relate to this sector. The other sector bearing attention are language industries.

The evidence shows that the traditional and digital Welsh language media sector influences the language in the following ways, by: (i) offering domains for language use (Ben Slimane Citation2008; Hughes Citation2017; Magnussen Citation1995) and as a result, in some cases, increasing the languages status and prestige (Ben Slimane Citation2008; Magnussen Citation1995), (ii) its promotion (Uribe-Jongbolde Citation2016; Zabaleta et al. Citation2010), (iii) its modernisation and standardisation (Hughes Citation2017; United Kingdom Government Citation2018; Zabaleta et al. Citation2008) and by (iv) supporting attainment (Baker Citation1985; Bangor University 2017, cited by the United Kingdom Government Citation2018). There is also evidence that the language industries offer opportunities for people to use the language as well as supporting learning and teaching (Ben Slimane Citation2008). Additionally, there is evidence that such industries provide employment for Welsh speakers, such as within the Welsh media in northwest Wales (Magnussen Citation1995). In this case, it is supposed that providing jobs outside Cardiff may stem the outward flow of Welsh-speaking workers to the capital city, however there is little empirical evidence to support this assertion (Magnussen Citation1995).

In general, the findings described above show that industries directly linked to the Welsh language have a positive influence on the language with examples provided of common facets of language planning measures, including status, prestige, corpus and acquisition planning (Baldauf Citation2006), and some claim that as a result the Welsh media have contributed towards saving the language (Hughes Citation2017; Magnussen Citation1995). O’Rourke and Hogan-Brun (Citation2013, 1) argue that such language planning measures are employed to improve language attitudes, often considered important in the process of language revitalisation. However, it is also suggested that the effectiveness of activities in this sector may also be limited. Uribe-Jongbolde (Citation2016), for example, found that Welsh language media producers experience tension between considerations related to promoting the minority language and professionalism or political considerations, with the former not always receiving priority. This suggests that the potential of the media as a language regeneration tool is limited (Hogan–Brun 2011, cited by Uribe-Jongbolde Citation2016); further proof if it were needed that the Welsh language does not exist in a vacuum and that there are a number of influences at work at any time (O’Malley Citation2006).

Category (ii): developments where the focus of the business is not directly related to the minority language itself

The second category of evidence gives attention to the influence of the activities of businesses which are not directly linked to the Welsh language but which, instead, engage with the Welsh language in other ways such as by operating in the Welsh language, or providing services through the language (Royles Citation2019).

An overview is offered in this section of the various ways in which the activities of such businesses influence the Welsh language. The types of influence can be summarised as follows: (i) by appropriating language policies for business purposes, thus turning the language into a commodity (Barakos Citation2016, Citation2018, Citation2020); (ii) by providing domains for using the Welsh language in the form of the workplace or through services offered (Ambrose Citation1978; Cunliffe, Pearson, and Richards Citation2010; Jones and Eaves Citation2010; Morgan Citation2000; Welsh Government Citation2012, Citation2015; Williams and Morris Citation2000) and this, in some cases, promoting the status and prestige of the language (Barakos Citation2018; Royles Citation2019; Williams and Morris Citation2000) and (iii) in the way the workplace provides muda for new speakers to change their linguistic habits (Hodges Citation2021; Tilley Citation2020). Once again, economic activity is shown to increase the status and prestige of the Welsh language (Baldauf Citation2006), making it more ‘societally desirable’ (Blommaert Citation2006, 244), and so increasing the likelihood of success of policies aimed at strengthening the Welsh language as they are in ‘consonance with the society’s linguistic culture’ (O’Rourke and Hogan-Brun Citation2013, 3).

Along with the influences above, several studies identify factors that influence the use of the Welsh language in the workplace or when offering services. Among the main factors posited are (i) the linguistic ability or fluency of staff, managers, owners and customers (Barakos Citation2012; Menter a Busnes Citation1993, Citation2003; Puigdevall i Serralvo and Williams Citation2003; Tilley Citation2020; Welsh Language Board, quoted by Welsh Government Citation2012; Welsh Government Citation2015); (ii) the opportunities available to use the language in various forms (Barakos Citation2012; Jones and Eaves Citation2010; Morgan Citation2000); (iii) the confidence individuals have to use the language or to request services (Barakos Citation2012; Hodges Citation2021; Puigdevall i Serralvo and Williams Citation2003; Consumer Focus Wales, cited by Welsh Government Citation2012; Welsh Language Board, cited by Welsh Government Citation2012); (iv) the access that companies have to resources to support the use of the language (Barakos Citation2012; Martin-Jones, Hughes, and Williams Citation2009; Puigdevall i Serralvo and Williams Citation2003; Thomas Citation1996; Welsh Language Commissioner Citation2018); (v) the approach that the company, managers and staff have towards the Welsh language (Jones and Eaves Citation2010; Puigdevall i Serralvo and Williams Citation2003; Welsh Language Board, cited by the Commissioner of the Welsh Language Citation2018; Welsh Government Citation2012); (vi) the investment of the business in terms of staff planning and training (Jones and Eaves Citation2010; Puigdevall i Serralvo and Williams Citation2003; The Welsh Language Board, cited by the Welsh Government Citation2012) and (vii) the company's commercial circumstances or priorities (Barakos Citation2012; Martin-Jones, Hughes, and Williams Citation2009; Welsh Language Commissioner Citation2018). The last point is supported by Puigdevall i Serralvo (Citation2005) and the Welsh Assembly Government (Citation2008) who state that the use of the Welsh language within the private sector has been controlled to a large extent by the market. To this end, it is argued that businesses that provide services in Welsh usually do so because of loyalty to the language or to meet tender requirements (Welsh Assembly Government Citation2008). This is particularly relevant as we consider that the private sector falls outside the reach of language legislation in Wales.

Category (iii) larger economic developments that do not have a direct link with a minority language

The third category discusses the influence of larger developments on the vitality of the Welsh language (Royles Citation2019). What distinguishes this category from category (i) is the fact that the major developments that are addressed here do not have a direct connection with the Welsh language, and unlike category (ii) it is not the activities within the business that are of concern. Royles (Citation2019) explains that the influence could cover the implications of changes within a sector that has a relatively high or low representation of Welsh speakers as part of the workforce or the influence of the development upon the labour market within an area of Welsh language significance.

There is evidence within this category to support the two examples offered by Royles (Citation2019). Relevant to the first example, it is proposed that due to a higher percentage of Welsh speakers within the agricultural workforce, economic trends that threaten the sustainability of this industry are likely to have a detrimental effect on the Welsh language (Farmers’ Union of Wales Citation2017; Hughes, Midmore, and Sherwood Citation1996, Citation2000; Jones Citation1992; Welsh Government Citation2020a). The family farm is an important feature of this industry in Wales and it is argued that destabilising the family farm disrupts the way in which it contributes economically and culturally to the wider community (Hughes, Midmore, and Sherwood Citation1996; Jones Citation1992). It is argued, as a result, that economic policies should take language implications into account. This is very timely when considering the fundamental changes to agricultural subsidies underway as a result of leaving the European Union and recent trends in corporations purchasing farmland for carbon offset schemes (Welsh Affairs Committee Citation2022).

Drawing on evidence from the tourism sector, research by the Welsh Government (Citation2020b) supports the second example posited by Royles (Citation2019), that is, larger developments can provide employment for Welsh speakers or work opportunities within areas with a high number of Welsh speakers. A belief shared by others too (Phillips Citation2000; Royles Citation2019; Welsh Government Citation2020b). It is suggested that this may encourage Welsh speakers to stay in areas where there is a high density of speakers, however there was little empirical evidence to support this rationale (Welsh Government Citation2020b). Indeed, it is noted that some developments struggle to recruit Welsh speakers as they ‘tend to move away’ (Welsh Government Citation2020b, 46) which somewhat undermines this belief. Consequently, we suggest that it cannot be assumed that providing employment within areas with a high density of Welsh speakers will benefit the language unconditionally.

Also relevant to the tourism sector, research commissioned by the Wales Tourist Board (ECTARC Citation1988) shows that tourists and local residents did not consider tourism to have a detrimental influence on the Welsh language. This is contrary to the evidence presented as part of Phillips' (Citation2000) literature review which shows deculturisation to be intrinsically linked to the growth of the sector. It is important to note that the authors of the ECTARC report believe that respondents confused unrelated issues, such as immigration and second homes with tourism – factors that were later proven by Phillips and Thomas (Citation2001) to be a negative side-effect of the industry on the Welsh language. This element is discussed more widely within the next category as it is within category (iv) that the indirect influences of economic developments receive attention.

Comparing the community energy sector in Wales and Scotland, Haf (Citation2016) and Haf and Parkhill (Citation2017) provide evidence of how larger scale developments are either bringing, or aiming to bring, communities together, thereby empowering minority languages. It was also found it to be the goal of communities to use the income generated by the initiatives to support activities that would directly benefit the language, such as providing Welsh lessons for local people (Haf and Parkhill Citation2017). Despite this, the sector appears to be further developed in Scotland and these benefits may not have been fully experienced in Wales as yet.

Attention is also given within this category to the influence of structural characteristics on the Welsh language. According to Puigdevall i Serralvo (Citation2005) structural characteristics limit indigenous businesses, namely those who are most likely to use Welsh as an operational language within business. Their research suggests that the more local the business is, in terms of their activity, customers and capital, the more likely it is to operate through the medium of Welsh. However, it is believed that factors such as economies of scale, the diverse and changing nature of the market, changes in the ownership and structure of companies, high employability of Welsh speakers within other sectors and the economic effects of globalisation contribute towards creating unfavourable structural circumstances for the local businesses, that is, those most likely to use the language (Puigdevall i Serralvo Citation2005, 251). The evidence provides a logical basis for the Welsh Government's aim to support ‘the socio-economic infrastructure of Welsh-speaking communities’ (Citation2017a, 63) in order to increase the use of Welsh. However, although the Marchnad Lafur CymraegFootnote1 report (Citation2020) agrees that the nature of the economy in rural areas of Wales is not a good basis for language regeneration, it presents some evidence of areas experiencing economic growth and language decline concurrently (Wavehill, quoted by Marchnad Lafur Cymraeg Citation2020). Considering the prominence of supporting the economic infrastructure of Welsh language communities within the Welsh Government's language strategy and the inconsistency or lack of evidence to support such a perception, the need for further research is evident.

Category (iv) indirect economic impact upon a minority language

The studies that are included within the fourth category examine indirect economic effects on language that are often linked to globalisation (Royles Citation2019). Royles (Citation2019) offers an example of this in the way that economic developments can lead to migration and this, in turn, can influence the vitality of the Welsh language in the areas affected. There is a relatively large pool of evidence to support this particular theory (Aitchison and Carter Citation1987, Citation1997, Citation1999, Citation2000; Ambrose Citation1978; Carter Citation1988; Drinkwater and O'Leary Citation1997; Giggs and Pattie Citation1992; Jones Citation2010; Lewis Citation1970; Morris Citation1990; Citation1991, Citation1993, Citation2013; Phillips Citation2000; Phillips and Thomas Citation2001; Royles Citation2019; Tunger et al. Citation2010; Vigers and Tunger Citation2010; Walker Citation2012; Wynn Citation2013).

Firstly, the manner in which economic restructuring can lead to the migration of a specific demographic as they take advantage of job opportunities is highlighted. For example, as a result of support from the State's regional development programmes at the end of the 50s, a number of sub-offices of companies with headquarters outside Wales were relocated to Gwynedd (Morris Citation1990). It was common for these companies to employ managers from outside Wales and therefore a number of non-Welsh-speaking managers were moved to the area (Morris Citation1990). Another example is the way educated and relatively young Welsh speakers were attracted from the rural strongholds of the Welsh language to Cardiff in order to take advantage of relatively well-paid employment within the public sector and the media industries (Aitchison and Carter Citation1987; Drinkwater and O'Leary Citation1997; Giggs and Pattie Citation1992; Jones Citation2010). As well as contributing towards the ability of the language to produce and reproduce (Morris Citation1990) and to the language composition of the areas in question (Aitchison and Carter Citation1987; Drinkwater and O'Leary Citation1997; Giggs and Pattie Citation1992) there was also implications for the Welsh language linked to the power and status of the migrants. It is believed that, in the case of the new arrivals to Cardiff, that they are representative of a new influential elite who demanded Welsh-medium education for their children and who contributed to the cause of securing a new Language Act (Aitchison and Carter Citation1997), providing an empirical example, perhaps, of how language attitudes can form the foundations of policy and planning, as professed by Spolsky (Citation2004). The gain of the Welsh language in the capital was of course the loss of the traditional strongholds, and these two examples are typical of the situation of the Welsh communities of the West as they experience the influence of the double-edged sword of migration upon the language.

According to Phillips and Thomas (Citation2001), the tourism industry drove migration into north Wales, a point which is supported by Walker (Citation2012). The results of their survey show that 41% of second-home owners reveal that they bought the property deliberately to retire to (Phillips and Thomas Citation2001). This provides clear evidence of a negative link between tourism and the Welsh language; by encouraging inward migration of non-Welsh speakers into Welsh language communities, weakening the linguistic makeup of these areas. Incidentally, a higher concentration of holiday homes can still be found in coastal areas of Wales such as in Gwynedd and Anglesey; where the percentage of homes not bought as a main residence is much higher in Gwynedd (28%) compared with the national average (15%) (Welsh Government Citation2023). Referring back to the ECTARC report (Citation1988) – who’s authors claimed that participants in the study ‘confused’ tourism with inward migration – it appears that participants were justified in their association.

What are the gaps in knowledge that could form the basis of further research and how could they be responded to?

In response to the second question of the review the information is synthesised across the categories used in the previous section to identify gaps in information that can form the basis of further research. Consideration is given to how the gaps could be addressed and recommendations for further research are put forward.

Supporting ‘the socioeconomic infrastructure of Welsh-speaking communities’ to provide favourable conditions for the language to flourish is one of the leading aims of the Welsh Government's current language strategy (Citation2017a, 63). However, although this review has generated evidence in support of the potential influence of various economic factors on the Welsh language, the evidence base to support the hypothesis that a prosperous economy leads to Welsh language vitality is thin and contradictory. Indeed, Wavehill's research in relation to the Arfor project (a scheme which aims to create more jobs within Welsh-language communities), found that ‘there is no positive relationship between economic development and an increase in the number of Welsh speakers in every case’ (Marchnad Lafur Cymraeg Citation2020, 12). In the same vein, Lewis and McLeod argue that it cannot be assumed that providing jobs will secure the minority language as it could perpetuate language shift if the employment opportunities attract workers who do not speak the minority language or if the dominant language is normalised yet further within the workplace (Citation2021, 265). This is not to say that such policies should be abandoned; scholars such as Danson argue convincingly in relation to Gàidhlig that ‘it is jobs and the economy that can help to drive the development of Gàidhlig, more than the use of Gàidhlig on its own that can help to drive the economy’ (Citation2021, 250). This said, we believe that a statistical study to investigate the relationship between economic growth and the viability of the Welsh language would provide an evidence base on which to further our understanding of this complicated relationship – a recommendation supported by the Marchnad Lafur Cymraeg report (Citation2020). Following such a statistical examination, a qualitative study might aim to explain the findings by looking at the use of language in relation to various economic activities such as the foundational approach as advocated by (Danson Citation2021, 250) paving the way for assessing the best way to achieve the Welsh Government's aim of supporting the socioeconomic infrastructure of Welsh-language communities. A recommendation that is supported within The Welsh Language and the Economy REA (Welsh Government Citation2020a, 85).

It is a common perception that good jobs and attractive careers are needed to prevent young Welsh speakers from leaving their communities, or to attract them back to Welsh-speaking heartlands (Arfor Citation2022; Welsh Government Citation2017a). However, although there is evidence included within this review of how attractive employment opportunities in Cardiff give rise to migration from strongholds of the Welsh language (Aitchison and Carter Citation1987), there is a lack of evidence to support the assumption that providing employment within Welsh communities is an effective means of stemming the outward flow. Furthermore, the findings linked to the influence of migration on the Welsh language are often based on older data. As a result, a number of knowledge gaps must be addressed if public policy interventions are to be based on this rationale.

Among the research questions that could be asked are, does securing quality employment and attractive careers within Welsh-language communities prevent Welsh speakers from migrating, or can it attract them back? And just as importantly, does this avoid a further decline in the linguistic composition of these areas or are there unexpected side-effects? In addition, the work of Wynn (Citation2013) could be built upon by investigating what motivates young Welsh speakers to move from Welsh-language communities, and also what attracts them back, complementing recommendations made by the Marchnad Lafur Cymraeg report (Citation2020) and Menter a Busnes (Citation2003).

Staying with the issue of migration, the literature generated as part of this review is based on older data, and there is a lack of evidence of the influence of current migration patterns on the Welsh language. As a result, it is argued that there is a need to examine contemporary migration patterns based on recent data, such as the United Kingdom census and other official statistics as recommended by Welsh Government (Citation2020a). Migration patterns within the United Kingdom and internationally as a result of Brexit (Royles Citation2019) or anti-urbanisation in response to the Covid-19 pandemic could be examined, taking into account any implications for the Welsh language.

Another issue requiring attention is the influence of larger developments on the Welsh language. The Welsh Government states within its Welsh 2050 strategy: A million speakers that the ‘type, scale and exact location of developments within a specific community has the potential to have an effect on language use, and as a result on the sustainability and vitality of the language’ (Citation2017a, 63). However, there is very little evidence to support this finding. Case studies could examine the influence of major developments, such as M–Sparc in Anglesey, from the point of view of explaining how they contribute to the viability of the Welsh language in the areas where they are located and, in this respect, contribute towards a wider understanding of how economic developments can influence the minority languages. An idea supported by the Marchnad Lafur Cymraeg report (Citation2020).

By systematically reviewing the literature, a number of research gaps relating to the influence of policies, trends and economic activities on the Welsh language are highlighted. Due to the breadth of the research field, and the dearth of research contributing towards the evidence base, more gaps were identified that could not be dealt with here. As a result, gaps were prioritised which, when dealt with, it is argued will make the most valuable contribution to the existing evidence base or, due to the current situation, most urgently need attention.

Methodological challenges and limitations

The main methodological challenges and limitations associated with this SR are highlighted here. The eligibility criteria limited the searches to the Welsh language due to the economic focus of current macro-level attempts to revitalise the Welsh language. It is suggested therefore that inclusion of other minority languages that are relevant to the context of the Welsh language would have provided a richer understanding of the influence of economic activities, policies and trends on minority languages more generally whilst assessing the validity of Royles’ categorisation framework within other contexts. Furthermore, we suggest that this review could be extended by including theoretical models that, although do not reference the Welsh language specifically, could be applied within a Welsh language context (see for example Grin and Vaillancourt Citation2021).

Additionally, drawing on Petticrew and Roberts (Citation2006, xiv), we agree that the nascent use of this SR methodology for social policy purposes means that it should not be considered perfect. Possible flaws may include a restricted search (Petticrew and Roberts Citation2006, 271) as the evidence generated is determined by the specific keywords and databases selected by the researchers. In an attempt to mitigate this risk, a hand-search of key journals, reference lists and specific reports was undertaken.

Discussion

According to Duchene and Heller (Citation2012) there has been a hegemonic shift in recent times from a discourse of language as cultural asset to language as commodity. In line with the earlier discourse, subsidising minority language activities (with little economic benefit) were justified on cultural terms, linked to the building of nation-states (Duchene and Heller Citation2012). In the case of Wales, Grin and Vaillancourt (Citation1999) found Welsh language television to be relatively cost effective as a means of promoting the minority language, given its positive impact on language attitudes and language use in particular. However, the demand for such an evaluation perhaps points to the languages limited economic worth and the need to justify investment on cultural grounds. More recently however, S4C (the Welsh language television channel) has sold a Welsh language programme to Netflix for the first time (S4C Citation2023) suggesting that the language has by now gained market value in of its own right. Scholars such as Puigdevall i Serralvo (Citation2005) have argued that the Welsh language within the private sector in Wales is controlled by the market, and so the lack of market value attributed to the language historically has resulted in its relative absence from the sector. It follows therefore that the newfound market value afforded to the Welsh language may lead to an increased presence within this sector and the economy more generally. However, as noted by Hogan-Brun (Citation2017, 24), ‘language is not a widget that can be manufactured, bought or sold with no other value attached to it’ and so we must watch with interest as Welsh, and other minority languages, negotiate their position within the relatively new domain of the economy. In providing an account of this story to date, this review provides and empirical insight into this transition.

In summary, the review concludes that there is a relatively solid body of evidence to support the importance of the workplace to the Welsh language, and a collection of studies that prove the significance of specific sectors such as agriculture and the Welsh language media to the sustainability of the language; and this aligns well with the Welsh Government's language strategy which, in principle at least, has the potential to raise the status and prestige of the language, leading to more favourable speaker attitudes (O’Rourke and Hogan-Brun Citation2013) and contributing towards reaching their target of one million Welsh speakers by 2050. However, when it comes to creating the socio-economic conditions for Welsh-speakers to stay in, or return to, Welsh-speaking communities – that is, a central tenet to the Welsh Government’s language policy (Citation2017a) – there is still very much more unknown than there is known, particularly in relation to the types of employment which could stem the flow. The main empirical and practical contribution of this review is therefore to highlight the urgent need for further primary research to better understand the influence of certain economic developments upon the Welsh language so that it may guide the implementation of the Welsh Government’s economic and language strategies.

Turning to the theoretical contribution of this paper, we are reminded that the main purpose of this SR was to assess what is known about the impact of economic policies, activities and trends on the Welsh language in order to test the validity of the economy > language aspect of Royles’ framework. Of the 15,414 references generated as part of the review, 73 were found to satisfy the search criteria and all of which were successfully allocated within Royles’ framework. The evidence generated as part of this review suggests therefore that Royles’ framework accurately encompasses and defines the various dimensions of economic impact on minority languages.

It is important to remember that only part of the framework has been tested here, and therefore the need remains to test the remaining parts of the framework, namely the impact of language variables on the economy. Other minority languages such as Irish, Basque or Catalan could also be examined to see if the framework is applicable to other minority languages. By comparing and contrasting with other minority language contexts and thus recognising similarities and identifying divergences it is possible to significantly enrichen understanding of the field.

Having verified the validity of the framework, it remains for us to assess ‘its value and its potential’ for policy makers in the fields of both economy and language (Royles Citation2019, 7). As previously noted, the precise nature of the relationship between economy and language has received little scholarly attention to date and so by identifying and defining similar types of development within distinct categories, the framework provides clarity and assists analysis within a complicated field. Broadly speaking, the types of development within the individual categories require distinct policy approaches; the potential of the framework lies in its ability to define and target such bespoke interventions. Although many of the policies discussed above are aimed at improving the status and prestige of the minority language, we emphasise that existing and emerging attitudes to language (themselves influenced by status, prestige and acquisition planning) will likely impact the success of these policies (Lewis Citation1981), and this should be born in mind by those responsible for public policy if attempts at language revitalisation are to succeed.

Summary

This study concludes that the impact of the economy on minority languages is an extremely complex area, where various conflicting and constantly changing influences are at play. By demonstrating the strength of evidence in specific policy areas, a clear rationale is provided in support of particular Welsh language strategies. However, the review has also highlighted gaps in the evidence base as well as drawing attention to unexpected or problematic consequences of past economic policies, suggesting that further research is needed to bolster some of the rationale underlying current policy thinking in Wales. Moreover, the study offers evidence in support of Royles’ economy > language framework and in doing so moves understanding of economic impact on minority languages from general to more definitive terms, providing researchers and policy makers alike with a useful and reliable tool to help make sense of this complex field of evidence and to target future policy interventions more effectively.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Marchnad Lafur Cymraeg was a pilot project which aimed to develop the Welsh language as a catalyst to the economy.

References

- Aitchison, John, and Harold Carter. 1987. “The Welsh Language in Cardiff: A Quiet Revolution.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 12 (4): 482–492. https://doi.org/10.2307/622797.

- Aitchison, John, and Harold Carter. 1997. “Language Reproduction: Reflections on the Welsh Example.” AREA 29 (4): 357–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.1997.tb00037.x.

- Aitchison, John, and Harold Carter. 1999. “Cultural Empowerment and Language Shift in Wales.” Journal of Economic and Social Geography 90 (2): 168–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9663.00059.

- Aitchison, John, and Harold Carter. 2000. Language, Economy, and Society: The Changing Fortunes of the Welsh Language in the Twentieth Century. Cardiff: Cardiff University Press.

- Ambrose, John E. 1978. “A Geographical Study of Language Borders in Wales and Brittany.” PhD diss. Glasgow University.

- Arfor. 2022. Prospectus. https://www.rhaglenarfor.cymru/dogfennau/Prospectws%20Arfor%202022_Cymraeg%20a%20Saesneg.pdf.

- Austin, Peter K., and Julia Sallabank. 2011. The Cambridge Handbook of Endangered Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Baker, Colin. 1985. “Ur (sic) Unig Ateb – The Only Answer? Mass Media, Bilingualism and Education.” In Aspects of Bilingualism in Wales, edited by Colin Baker, 122–150. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Baldauf, Robert B. 2006. “Rearticulating the Case for Micro Language Planning in a Language Ecology Context.” Current Issues in Language Planning 7 (2–3): 147–170. https://doi.org/10.2167/cilp092.0.

- Barakos, Elisabeth. 2012. “Language Policy and Planning in Urban Professional Settings: Bilingualism in Cardiff Businesses.” Current Issues in Language Planning 13 (3): 167–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2012.722374.

- Barakos, Elisabeth. 2016. “Language Policy and Governmentality in Businesses in Wales: A Continuum of Empowerment and Regulation.” Multilingua 35 (4): 361–391.

- Barakos, Elisabeth. 2018. “Managing, Interpreting and Negotiating Corporate Bilingualism in Wales.” In English in Business and Commerce, edited by Tamah Sherman and Jiri Nekvapil, 73–95. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Barakos, Elisabeth. 2020. Language Policy in Business : Discourse, Ideology and Practice. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Ben Slimane, Mourad. 2008. “Appropriating New Technology for Minority Language Revitalization.” PhD diss., Freie Universität Berlin.

- Blommaert, Jan. 2006. “Language Policy and National Identity.” In An Introduction to Language Policy: Theory and Method, edited by T. Ricento, 238–254. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Carter, Harold. 1988. Mewnfudo a'r Iaith Gymraeg. Casnewydd: Llys yr Eisteddfod Genedlaethol.

- Crystal, David. 2002. Language Death. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cunliffe, D., Nich Pearson, and Sarah Richards. 2010. “E-commerce and Minority Languages: A Welsh Perspective.” In Language and the Market, edited by H. Kelly-Holmes and Gerlinde Mautner, 135–147. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Danson, Mike. 2021. “Gàidhlig, Gaeilge, Cymraeg and Føroyskt Mál: Minority Languages as Economic Assets?” In Language Revitalisation and Social Transformation, edited by W. McLeod and H. Lewis, 225–258. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Davies, Janet. 2014. The Welsh Language: A History. Wales: University of Wales Press.

- Drinkwater, S. J., and N. C. O'Leary. 1997. “Unemployment in Wales: Does Language Matter?” Regional Studies 31 (6): 583–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343409750131712.

- Duchene, Alexandre, and Monica Heller. 2012. Language in Late Capitalism : Pride and Profit. New York: Routledge.

- ECTARC (European Centre for Traditional and Regional Culture). 1988. Study of the Social, Cultural and Linguistic Impact of Tourism in and Upon Wales. Cardiff: Wales Tourist Board.

- Farmers’ Union of Wales. 2017. Farming in Wales and the Welsh Language. Aberystwyth: Farmers’ Union of Wales.

- Giggs, John, and Charles Pattie. 1992. “Wales as a Plural Society.” Contemporary Wales: An Annual Review of Economic and Social Research 5 (1992): 25–64.

- Grin, François. 1996. “Economic Approaches to Language and Language Planning: An Introduction.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 121 (1996): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl.1996.121.1.

- Grin, François, and François Vaillancourt. 1999. The Cost-Effectiveness Evaluation of Minority Language Policies: Case Studies on Wales, Ireland and the Basque Country. Flensburg: ECMI Monographs.

- Grin, François, and François Vaillancourt. 2021. “The Economics of ‘Language[s] at Work’: Theory, Hiring Model and Evidence.” In Language Revitalisation and Social Transformation, edited by W. McLeod and H. Lewis, 193–224. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Haf, Sioned. 2016. “The Winds of Change? A Comparative Study of Community Energy Developments in Scotland and Wales.” PhD diss. Bangor University.

- Haf, Sioned, and Karen Parkhill. 2017. “The Muillean Gaoithe and the Melin Wynt: Cultural Sustainability and Community Owned Wind Energy Schemes in Gaelic and Welsh Speaking Communities in the United Kingdom.” Energy Research & Social Science 29: 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.05.017.

- Hodges, Rhian. 2021. “Defiance Within the Decline? Revisiting New Welsh Speakers’ Language Journeys.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 45 (2): 306–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2021.1880416.

- Hogan-Brun, Gabrielle. 2017. Linguanomics: What is the Market Potential of Multilingualism?. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Hughes, Robert Glyn Môn. 2017. “The Role of Welsh Language Journalism in Shaping the Construction of Welsh Identity and the National Character of Wales.” PhD diss. Liverpool John Moores University.

- Hughes, Garth, Peter Midmore, and Anne-Marie Sherwood. 1996. Language, Farming and Sustainability in Rural Wales. Aberystwyth: Welsh Institute of Rural Studies.

- Hughes, Garth, Peter Midmore, and Anne-Marie Sherwood. 2000. “Yr Iaith Gymraeg a Chymunedau Amaethyddol yn yr Ugeinfed Ganrif.” In ‘Eu Hiaith a Gadwant’? Y Gymraeg yn yr Ugeinfed Ganrif, edited by Geraint H. Jenkins and Mari A. Williams, 531–556. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Jesson, Jill, Lydia Metheson, and Fiona M. Lacey. 2011. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques. London: Sage.

- Jones, Elin. 1992. “Economic Change and the Survival of a Minority Language: A Case Study of the Welsh Language.” In Lesser-used Languages: Assimilating Newcomers, edited by Llinos Dafis, 120–133. Tal-y-bont: Y Lolfa.

- Jones, Hywel. 2010. “Welsh Speakers: Age–Profile and Out-Migration.” In Welsh in the Twenty First Century, edited by Delyth Morris, 188–147. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Jones, Kathryn, and Steve Eaves. 2010. Internal Use of Welsh in the Workplace. Wales: Iaith Cyf.

- Kaplan, Robert B., and Richard B. Baldauf. 1997. Language Planning: From Practice to Theory. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Lewis, Gareth J. 1970. “A Study of Socio-Geographic Change in the Central Welsh Marchland since the Mid-Nineteenth Century.” PhD diss., Leicter University.

- Lewis, E. Glyn. 1981. Bilingualism and Bilingual Education. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- Lewis, Huw, and Wilson McLeod. 2021. “Regional and Minority Languages and the Economy: The Evolution of Structural and Analytical Challenges.” In Language Revitalisation and Social Transformation, edited by W. McLeod and H. Lewis, 225–258. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Magnussen, Birgitte. 1995. “Minority Language Television – Social, Political and Cultural Implications.” PhD diss., The City University.

- Marchnad Lafur Cymraeg. 2020. Marchnad Lafur Cymraeg: Summary Report Highlighting Relevant Outputs and Key Recommendations from the Marchnad Lafur Cymraeg Project. https://www.arsyllfa.cymru/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Marchnad-Lafur-Cymraeg-Report.pdf.

- Martin-Jones, Marilyn, Buddug Hughes, and Anwen Williams. 2009. “Bilingual Literacy in and for Working Lives on the Land: Case Studies of Young Welsh Speakers in North Wales.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 195 (2009): 39–62.

- Menter a Busnes. 1993. Y Defnydd o'r Gymraeg ym Musnesau Ceredigion. Aberystwyth: Menter a Busnes.

- Menter a Busnes. 2003. Adolygiad Llenyddiaeth ar Gyswllt Iaith-Economi. Aberystwyth: Menter a Busnes.

- Moher, David, Larissa Shamseer, Mike Clarke, Davina Ghersi, Alessandro Liberati, Mark Petticrew, Paul Shekelle, Lesley A. Stewart, and PRISMA-P Group. 2015. “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta–Analysis Protocols (PRISMA–P) 2015 Statement.” Systematic Reviews 4 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1.

- Morgan, T. 2000. “Welsh in the Workplace: A Study of the Gwendraeth Valley, South Wales.” In Developing Minority Languages, edited by P. Thomas and J. Mathias, 224–231. Llandysul: Gomer/ Cardiff University.

- Morris, Delyth. 1990. “Ailstrwythuro Economaidd a Ffracsiynau Dosbarth yng Ngwynedd.” PhD diss.. Bangor University.

- Morris, Delyth. 1991. “The Effect of Economic Changes on Gwynedd Society.” In Lesser Used Languages – Assimilating Newcomers: Proceedings of the Conference Held at Carmarthen, 1991, edited by Llinos Dafis, 134–157. Carmarthen: Joint Working Party on Bilingualism in Dyfed.

- Morris, Delyth. 1993. “Patrymau Iaith a Chyflogaeth yng Ngwynedd, 1891–1991.” Byd 7 (1993): 6–8.

- Morris, Delyth. 2013. “Datblygiad Economaidd Anwastad a’r Rhaniad Diwylliannol o Lafur.” In Pa Beth yr Aethoch Allan i'w Achub?: Ysgrifau i Gynorthwyo'r Gwrthsafiad yn Erbyn Dadfeiliad y Gymru Gymraeg, edited by Simon Brooks and Richard Glyn Roberts, 75–96. Llanrwst: Gwasg Carreg Gwlach.

- Office of National Statistics. 2022. “Welsh Language, Wales: 2021.” Office of National Statistics. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/language/bulletins/welshlanguagewales/census2021.

- O’Malley, Tom. 2006. “The Newspaper Press in Wales.” Contemporary Wales 18 (1): 202–213.

- O’Rourke, Bernadette, and Gabrielle Hogan-Brun. 2013. “Language Attitudes in Language Policy and Planning.” In The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics, edited by C. A. Chapelle, 1–4. Chichester: Blackwell Publishing.

- Paul, Justin, and Alex R. Criado. 2020. “The Art of Writing Literature Review: What Do We Know and What Do We Need to Know?” International Business Review 29 (4): 101717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2020.101717.

- Petticrew, Mark, and Helen Roberts. 2006. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Phillips, Dylan. 2000. “Pa Bris y Croeso? Effeithiau Twristiaeth ar y Gymraeg.” In ‘Eu Hiaith a Gadwant’? Y Gymraeg yn yr Ugeinfed Ganrif, edited by Geraint H. Jenkins and Mari A. Williams, 508–530. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Phillips, Dylan, and Catrin Thomas. 2001. The Effects of Tourism on the Welsh Language in North-West Wales. Aberystwyth: The Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies.

- Puigdevall i Serralvo, Maite. 2005. “Challenge of Language Planning in the Private Sector: Welsh and Catalan Perspectives.” PhD diss., Cardiff University.

- Puigdevall i Serralvo, Maite, and Colin H. Williams. 2003. A Challenge Yet to be Faced: SMEs and the Planned Use of Welsh. http://www.gencat.cat/llengua/documentacio/articles/DOT16Con_2n_Congres_Europeu_PL/DOT16Con–Pui;%20DOT16Con–Wil.pdf.

- Royles, Elin. 2019. Workshop Briefing Report 3: Language Revitalisation and Economic Transformation. https://revitalise.aber.ac.uk/en/media/non-au/revitalise/Revitalise—Workshop-Report-3—FINAL.pdf.

- S4C. 2023. “S4C crime drama, Dal y Mellt, sold to Netflix.” S4C, January 19. https://www.s4c.cymru/en/press/post/54344/s4c-crime-drama-dal-y-mellt-sold-to-netflix/.

- Shamseer, Larissa, David Moher, Mike Clarke, Davina Ghersi, Alessandro Liberati (deceased), Mark Petticrew, Paul Shekelle, Lesley A. Stewart, and the PRISMA–P Group. 2015. “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta–Analysis Protocols (PRISMA–P) 2015: Elaboration and Explanation.” BMJ 349: g7647. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647.

- Spolsky, Bernard. 2004. Language Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Thomas, Elinor R. 1996. Yr Iaith ar Waith ym Myd Marchnata: Adroddiad yn Ymchwilio Defnydd yr Iaith Gymraeg ym Myd Marchnata. Aberystwyth: Menter a Busnes.

- Tilley, Eileen. 2020. “Narratives of Belonging: Experiences of Learning and Using Welsh of Adult “New Speakers” in North West Wales.” PhD diss., Bangor University.

- Tunger, Verena, Clare Mar-Molinero, Darren Paffey, Dick Vigers, and Cecylia Barłóg. 2010. “Language Policies and ‘New’ Migration in Officially Bilingual Areas.” Current Issues in Language Planning 11 (2): 190–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2010.505074.

- United Kingdom Government. 2018. Building an S4C for the Future: An Independent Review. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/695964/Building_an_S4C_for_the_Future_English_Accessible.pdf.

- Uribe-Jongbolde, Enrique. 2016. “Issues of Identity in Minority Language Media Production in Colombia and Wales.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 37 (6): 615–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2015.1111895.

- Vacca, Alessia. 2013. “Welsh Language (Wales) Measure 2011, Use of Welsh in the Public Administration: A Step Forward?” Journal of Language and Law 59 (2013): 131–138. https://doi.org/10.2436/20.8030.02.8.

- Vigers, Dick, and Verena Tunger. 2010. “Migration in Contested Linguistic Spaces: The Challenge for Language Policies in Switzerland and Wales.” European Journal of Language Policy 2 (2): 181–203. https://doi.org/10.3828/ejlp.2010.12.

- Walker, Michelle T. 2012. “The English in North–west Wales: Migration, Identity and Belonging 1970–2010: An Oral History.” PhD diss., Bangor University.

- Welsh Affairs Committee. 2022. The Economic and Cultural Impacts of Trade and Environmental Policy on Family Farms in Wales. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5802/cmselect/cmwelaf/607/report.html.

- Welsh Assembly Government. 2008. Use of Welsh Language in the Private Sector: Case Studies. https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/statistics-and-research/2018-12/111215welshlanguageen.pdf.

- Welsh Government. 2012. Welsh Language Strategy Evidence Review. https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/statistics-and-research/2019-08/120301welshlanguageen.pdf.

- Welsh Government. 2015. Welsh Language Use in the Community: Research Study. https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/statistics-and-research/2019-01/welsh-language-use-in-the-community-research-study.pdf.

- Welsh Government. 2017a. Cymraeg 2050: A Million Welsh Speakers. https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2018-12/cymraeg-2050-welsh-language-strategy.pdf.

- Welsh Government. 2017b. Prosperity for All: Economic Action Plan. https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2019-02/prosperity-for-all-economic-action-plan.pdf.

- Welsh Government. 2020a. The Welsh Language and the Economy: A Review of Evidence and Methods. https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/statistics-and-research/2020-02/the-welsh-language-and-the-economy-a-review-of-evidence-and-methods.pdf.

- Welsh Government. 2020b. Review of Tourism Attractor Destinations: Interim Report. https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/statistics-and-research/2020-01/evaluation-of-the-tourism-attractor-destinations-interim-report.pdf.

- Welsh Government. 2023. Second Homes: What Does the Data Tell Us? https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/pdf-versions/2023/6/2/1687268804/second-homes-what-does-data-tell-us.pdf.

- Welsh Language Commissioner. 2018. Using Welsh: The Business Case. https://www.welshlanguagecommissioner.wales/media/rphlgwaf/using-the-welsh-language-the-business-case.pdf.

- Williams, Colin H. 2000. “Conclusion: Economic Development and Political Responsibility.” In Language Revitalization: Policy and Planning in Wales, edited by Colin W. Williams, 362–379. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Williams, Glyn, and Delyth Morris. 2000. “Language Use in the Workplace.” In Language Planning and Language Use: Welsh in a Global Age, edited by Glyn Williams and Delyth Morris, 129–152. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Wynn, Lowri A. C. 2013. “Allfudiaeth Pobl Ifanc o'r Broydd Cymraeg.” PhD diss., Bangor University.

- Zabaleta, Iñaki, Nicolás Xamardo, Arantza Gutierrez, Santi Urrutia, and Itxaso Fernandez. 2008. “Language Development, Knowledge and Use among Journalists of European Minority Language Media.” Journalism Studies 9 (2): 95–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700701848238.

- Zabaleta, Iñaki, Nicolás Xamardo, Arantza Gutierrez, Santi Urrutia, Itxaso Fernandez, and Carme Ferré. 2010. “Between Language Support and Activism.” Journalism Studies 11 (2): 190–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700903290668.