ABSTRACT

This paper adopts a mixed research method to explore the language shift of secondary Yi students in Liangshan through their language choices and motivations in different discursive contexts. Yi students in this study provides a unique setting to examine language shift in languages and dialects at the same time, as they speak an ethnic minority mother tongue (Nuosu Yi), a local dialect of Mandarin (Southwestern Mandarin), and Mandarin in their daily interactions. Likert-type responses about language use in the context of Family, Friend, and Society were elicited from 353 students through questionnaires, followed by 23 interviews which explored the motivations behind the language choices. Findings revealed that although Nuosu Yi remained a prevalent language in Yi students’ daily life, its use was primarily limited to private conversations with friends and family members. In addition, there was an evident increased use of Mandarin in Yi students’ peer communication compared to intergenerational conversations, which can be taken as a sign for language shift. Lastly, Southwestern Mandarin was found to play an important bridging role in Yi students’ daily communication and was endowed by Yi students with both sentimental and instrumental value.

Introduction

This paper investigates the language shift (hereinafter LS) of secondary Yi students in Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture. Nuosu Yi is spoken by the sixth largest ethnic minority group – the Yi group (彝族) – in China. In recent years, a waning interest in Nuosu Yi has been reported (Wang Citation2018; Yao, Turner, and Bonar Citation2022; Zhang and Tsung Citation2019), but to what extent, or in what discursive contexts, the LS has occurred among young Yi people remains to be explored. A significance of the study is the joint investigation of LS in both languages and dialects. Although the two are arguably the most studied directions in LS, they have typically been investigated independently in previous research. Liangshan provides a setting to examine them both at the same time: Yi people in Liangshan alternate between speaking three languages/dialects in daily interactions, including their mother tongue (Nuosu Yi), a local dialectal variety of Mandarin (Southwestern MandarinFootnote1), and Mandarin (also known as Putonghua). An investigation of Yi students’ language practice thus has the potential to shed light on LS from minority to mainstream languages, as well as from low to high dialectal varieties.

A central tenet adopted by this study is the view of LS as a dynamic process. Analysing the language practice by bi/multilingual individuals in a particular context is a useful way to understand the process (Hornberger Citation2012). The study examined Yi students’ language choices and motivations in three specific contexts: with family members (Family), with friends (Friend), and with members of society (Society). Among the three contexts, the family domain is believed to be the last bastion of first language (L1) use and maintenance. If L1 is no longer used in the family sphere, the process of LS is often considered to be complete (Yu Citation2010). The context of Friend explored the language use of Yi students with the younger generation, as a comparison to their intergenerational language use with family members. Moreover, Family and Friend were both private domains where languages tend to be endowed with sentimental value. Society, in contrast, provided a context to study the instrumental value attached to languages by Yi students, given that languages serve various communicative functions in this domainFootnote2 (Karan Citation2008).

LS as a dynamic process

LS refers to ‘the gradual displacement of one language by another in the lives of the community members’ (Dorian Citation1982, 44), which is manifested as a decrease in the number of speakers, level of proficiency, or range of communicative use of the language. LS often occurs from minority languages – in either ‘numerical or power terms’ (Hornberger Citation2012, 413) – to majority languages. Young people’s language choices and motivations have been a focus in LS or language maintenance research, as it is projected that half of the world’s languages will disappear because of the younger generation no longer speaking their mother tongues (Austin and Sallabank Citation2011).

LS can be studied from a macro or micro perspective. A macro perspective focuses on factors such as urbanisation, migration, internationalisation, education, media, and religion that affect individuals’ language practice (Fasold Citation1984; McDuling and Barnes Citation2012; Pauwels Citation2004). A micro perspective, on the other hand, commonly focuses on the language use, choices, and attitudes of bi/multilingual speakers. For example, Karan (Citation2008) highlighted the importance of investigating motivations in LS research and proposed a six-dimension Taxonomy of Language Choice Motivations (communicative, economic, social identity, language power and prestige, nationalistic and political, religious). He noted that the taxonomy also applies to dialect-related LS studies, thus language choice can be understood as either ‘language code choice or language variety choice’ (ibid, p. 3).

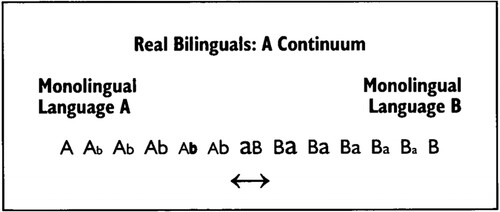

Research at the micro level has noticed the dynamism and ambiguity in the process of LS. Specifically, the traditional definition of LS tends to describe the process as two poles on a continuum, namely speakers of the minority language shift away from their L1 or mother tongue to the majority language. In real-life practice, however, except for some speaker groups where complete LS has been identified, many speaker groups are in a so-called status of ‘relatively stable bilingualism’ (McDuling and Barnes Citation2012, 169). Their language practice falls somewhere along the spectrum, which is reflected by the bilingual continuum () proposed by Valdés (Citation2001). Many bi/multilingual speakers were found to make language choices flexibly based on contexts or interlocutors (Gomashie Citation2022; Wang Citation2019), and a person may have different strong/weak (or dominant/non-dominant) languages at different stages of life (Yu Citation2010). A dichotomous view of LS that neglects the dynamic nature of the process (i.e. the various points along the continuum) would fail to capture the abovementioned nuances.

Figure 1. The bilingual continuum drawn from Valdés (Citation2001, 41). In real-life practice, bilingual speakers’ language practice lies in a continuum, with monolingual language A and B located at both ends and the varied combinations of A and B in between.

The dynamic and ambiguous nature of LS makes it difficult to conclude that a LS, in its traditional definition, has or has not occurred, or a LS will or will not occur in the future. Hornberger (Citation2012) contended that ‘the issue is, the defining question of the field, how do we predict which languages have shifted, or will shift?’ (413). She argued that the focus of the field should be on the extent (or the contexts) that LS has occurred, with the dynamism of the process being the central inquiry.

Guided by this perspective, research found that there are evident indicators of LS even though the process has not been complete. For example, studies on minority language groups found that even though the speakers used both their mother tongues and mainstream languages in daily life, the mainstream languages were used more in functional domains such as schools and workplaces, while their mother tongues were limited to the use in private contexts (Gomashie Citation2022; Luo Citation2018). This can be taken as a sign of LS (or a possible trend for LS) as speakers may place ‘the instrumental value of a language above sentimental or symbolic value’ (Saravanan and Hoon Citation1997, 380). LS research on dialects found a similar trend. For example, Yu’s (Citation2010) research in Suzhou found that even though both Suzhou dialect and Mandarin were used in commercial domains, Suzhou dialect was used mainly in grocery markets, while Mandarin was used dominantly in high-end shopping malls. He concluded that Suzhou dialect was gradually evolving into a ‘底层语言 (grassroots language)’ (68). This may lead to the LS from Suzhou dialect to Mandarin in the long run.

LS research in China and on Yi group

LS research on Chinese languagesFootnote3 has been conducted around the world. Research based in non-Chinese speaking countries (or countries where Chinese is not a mainstream language) often focuses on LS and language maintenance of Chinese as a heritage language (Ong Citation2021; Zhang Citation2010). Research based in Mainland China can be divided into two main types: LS from local Chinese dialects to Mandarin (Dong Citation2018; Yu Citation2010), and LS from ethnic minority languages to Mandarin. Most relevant to this study is the latter type, as the focused group is an ethnic minority group in China (although the languages the group speak include a local Chinese dialect).

China is a multilingual and multi-ethnic country where Mandarin is the official language. The language practice of different ethnic minority groups in China varies but can be broadly summarised into the following four types. Firstly, some ethnic minority groups make a prevalent use of their ethnic minority languages, and no evident sign of LS has been identified, for example, see Luo’s (Citation2018) study in Yunnan, and Zhang and Adamson’s (Citation2023) study in Xinjiang. This type often occurs in remote ethnic areas of China. The second type, which is the most common one, is a mixed use of the ethnic minority languages and Mandarin, but it is to note that, the way languages are mixed varies from one ethnic group to another (Sha Citation2005; Tsung Citation2016; Wang Citation2019). The third type is an almost complete LS from ethnic minority languages to Mandarin. This type mainly occurs in ethnic groups who have close contact with the Han groupFootnote4 in history, for example, the Tujia (土家) and Yugu (裕固) ethnic group. Some of these minority languages have been categorised as intangible cultural heritage, so research was often conducted from a perspective of language inheritance rather than revitalisation (Ba Citation2016; Zhang and Yang Citation2020). The fourth type, which is also the least common type, is that some minority groups choose to shift from their mother tongues to a more influential local minority language. For example, Li’s (Citation2017) study in Xinjiang found that there was a shift from the Tuva language to Mongolian and Kazakh among the Tuvan ethnic group (图瓦族).

Wang (Citation2019) found that the language practice of many ethnic groups in China has shown characteristics of ‘嵌套性 (nesting)’ and ‘多元性 (plurality)’ (22), meaning that the phenomenon of a mixed language use is common, complex, and dynamic among the ethnic minority groups.Footnote5 He (ibid) also argued that many minority language speakers are in a status of ‘relatively stable bilingualism’ and are unlikely to undergo a complete LS in the near future, but their language practice and motivations require ongoing attention.

Nuosu Yi in Liangshan

The Yi ethnic group is the sixth largest ethnic minority group in China. The Yi people speak the Yi language, which is a typical pluricentric language with different varieties. Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture, located in Sichuan Province in the Southwest of China, is a main residence of the Yi people. The Yi people in Liangshan, which is the focus of this study, mainly speak Nuosu Yi (诺苏彝, a variety of the Yi language) as their mother tongue. Other than Nuosu Yi, many Yi people in Liangshan also speak Tuanjie Hua (团结话), a variety of the Sichuan dialect of MandarinFootnote6, which is referred to as Southwestern (SW) Mandarin in this paper. Lastly, many young Yi people also speak Mandarin in daily life (Zheng and Zhu Citation2018). Although the three languages/dialects are widely used by Yi people in Liangshan, no research to date, to the best of our knowledge, has explored them in a unified way from a perspective of LS.

Secondary Yi students in Liangshan, which are the focus of this study, can choose to receive primary and secondary education through either Nuosu Yi or Mandarin. Model One education (一类模式) uses Nuosu Yi as the medium of instruction (MoI), and Model Two education (二类模式) uses Mandarin as the MoI. In recent years, the Education Department of Liangshan has stipulated a range of policies to promote Nuosu Yi learning, including raising its weight in high-stake examinations. Despite this, there has been a continuing waning interest in learning and using Nuosu Yi among the young people (Feng and Adamson Citation2018; Wang Citation2018; Zhang and Tsung Citation2019).

There has been some LS-related research on the Yi group, but the context was not in Liangshan. For example, Sha (Citation2005) conducted a study of the Yi speakers in Panzhihua City, Sichuan, and found that the Yi people of Lipo (理泼) and Shuitian (水田) varieties had undergone complete LS. The Nuosu variety, on the other hand, had only experienced partial LS, or what he called, ‘主体语言转换 (subject LS)’ (37), meaning that the language practice bearing more communicative purposes had been shifted to Mandarin, but Yi remained as the dominant language in private domains and intimate conversations. In addition, Luo’s (Citation2018) research in three Yi communities in Yunnan Province found that although the Yi language was still prevalent in Yi-populated areas, speakers in areas where Yi and Han people lived together had shifted to Mandarin in daily communication.

The study

Framed by the perspective of LS as a dynamic process, the study set out to explore whether there is a different use of languages/dialects in different contexts by Yi students, the motivations behind the language practice, and how it might indicate signs of LS. The specific research questions are: (1) What are the language choices of Yi students regarding Nuosu Yi, SW Mandarin, and Mandarin in the discursive context of Family, Friend, and Society? (2) Why do they make a certain language choice in a particular context?

The study adopted a mixed-methods design to investigate the research questions, in which data were collected through two instruments: (1) a questionnaire administered to Yi students to answer the first question, namely their language choices in the context of Family, Friend, and Society; (2) follow-up semi-structured interviews to answer the second question, namely the motivations behind their language choices.

Participants

The fieldwork was conducted from June to July 2022 in two secondary schools in Xide County (喜德县), a Yi-populated county in Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture. Both schools had over 90% of Yi students but differed in the MoI, so that a fuller picture of Liangshan Yi students’ language practice can be presented. Specifically, School A had a total of ca. 6,000 students, with Nuosu Yi being the MoI (Model One education), and School B had a total of ca. 4,500 students, with Mandarin being the MoI (Model Two education).

Participants were 183 Yi students (female: 72%, male: 28%) from School A and 193 Yi students (female: 61%, male: 39%) from School B, with a balanced breakdown across Grades 9 - 11 (ca. 15 - 19 years old) from either school. Since the study was conducted in schools and most participants (93%) were below the age of eighteen, we obtained the permission of the school leaders and student teachers at the outset of the study. Explanatory statements and consent forms were also given to and signed by student participants before participation. The schools and participants were anonymised.

Instruments

A questionnaire eliciting Likert-type responses (O'Leary Citation2021) from the participants about their language use was developed as part of a larger scale project. The questions relevant to this study are listed in Appendix AFootnote7, which (1) collected the students’ demographic information; (2) explored whether Nuosu Yi/SW Mandarin/Mandarin was the main language used in the context of Family/Friend/Society, by having the students indicate their agreement with the statement ‘I mainly speak Language in Context’ (9 statements = 3 languages × 3 contexts) on a 5-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Based on the questionnaire responses, follow-up interviews, each lasting 10 - 15 min, were conducted with 23 students. Themes covered were flexible based on participants’ responses to the survey questions but were mainly related to their rationale of choosing a particular language (or languages) in varied discursive contexts (e.g. you mentioned in the survey that you talk to your friends at school mainly in SW Mandarin. Can you tell me why?). Sometimes the topic of the interviews also extended to the language environment surrounding the students, such as the language expectations of those around them (e.g. have your parents ever asked you to use (or not use) a certain language when you are at home? Why?). The interviews were conducted in Mandarin and audio recorded. Field notes were also taken after each interview. The questionnaires and interviews were completed during the students’ evening self-study time in school to minimise the project’s impact on their normal life and study.

Analysis

Questionnaires with missing or invalid answers to questions relevant to the study were excluded from the analysis. Overall, responses from 174 Model One students (female: 72%, male: 28%) and 179 Model Two students (female: 63%, male: 37%), complemented by 11 interviews with the Model One students and 12 interviews with the Model Two students, were analysed.

Questionnaire responses were analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics in R Statistical Software (v4.2.2) (R Core Team Citation2022). Since the Likert-type responses were ordinal data and multiple factors (language, context, MoI) were involved, ordinal logistic regression (O'Connell Citation2006) was the best approach for the inferential analysis. However, given that the main assumption of the ordinal regression model, namely proportional odds, was violated for the current data (and it is often violated when fitted to real-life data, see Liu and Koirala Citation2012; Erling, Brummer, and Foltz Citation2022), and the data did not follow a normal distribution, more traditional non-parametric inferential statistics were used. This involved Friedman tests for within-subject comparisons of the responses towards all the three languages in varied contexts, or towards a single language in all the three contexts, followed by Durbin-Conover tests and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for pairwise comparisons. p values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method and evaluated against an α level of 0.05.

The recorded interview data were automatically transcribed using the iFLYTEK software, followed by manual correction. The interview transcripts and field notes totalled around 23,000 words. They were then exported to NVivo 11 and analysed using Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) six-step thematic analysis procedure, including field notes reflection, initial coding, skimming, searching and reviewing emerging themes, and organising themes into identified categories, with the aim to extract and synthesise similar motivations for participants’ language choices in each discursive context. Some themes mentioned by several interviewees emerged, such as ‘the ability to speak Nuosu Yi as an identity marker’ and ‘viewing SW Mandarin as a more approachable language than Mandarin’. These themes are discussed in detail in the next section.

Findings

Questionnaires

This section presents the findings of the questionnaires, relevant to the first research question: what are the language choices of Yi students regarding Nuosu Yi, SW Mandarin, and Mandarin in the context of Family, Friend, and Society?

A comprehensive view, taking all the contexts into account, indicated a highest level of agreement with Nuosu Yi being the main language used in the students’ daily communication (N = 1059, mean = 3.81, SD = 1.11), followed by SW Mandarin (N = 1059, mean = 3.24, SD = 0.96), and Mandarin (N = 1059, mean = 3.06, SD = 0.99). A Friedman test confirmed a statistically significant difference in the responses towards the use of the three languages (χ2Friedman(2) = 206.25, p < 0.001, W = 0.10). Post-hoc tests showed that all the pairwise comparisons between the languages were significant (Nuosu Yi – SW Mandarin/Mandarin: ps < 0.001; SW Mandarin – Mandarin: p = 0.02), suggesting that the use frequency of the three languages was Nuosu Yi > SW Mandarin > Mandarin. Therefore, it seemed that Nuosu Yi was still a dominant language used by Yi students in daily life. There was no prominent sign of LS from this perspective. Additionally, SW Mandarin was used more commonly than Mandarin. This is a new finding, partially because very few studies have investigated the use of SW Mandarin among Yi students.

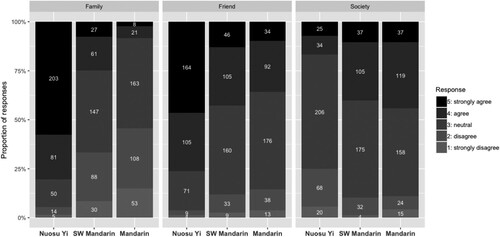

With Nuosu Yi being the overall most spoken language and SW Mandarin being more spoken than Mandarin, the Yi students’ language practice varied across the contexts. illustrates the students’ responses towards each language in each context and summarises the data. As can be seen, the context of Family showed the same language use pattern as the overall trend, namely Nuosu Yi > SW Mandarin > Mandarin (χ2Friedman(2) = 353.87, p < 0.001, W = 0.50; all pairwise comparisons: ps < 0.001). Nuosu Yi remained to be the most used language in the context of Friend (χ2Friedman(2) = 152.21, p < 0.001, W = 0.22; Nuosu Yi – SW Mandarin/Mandarin: ps < 0.001), but there was no longer a significant difference between SW Mandarin and Mandarin (p = 0.33). The context of Society showed a similar use of SW Mandarin and Mandarin as well (p = 0.94) whereas Nuosu Yi became the least used language (χ2Friedman(2) = 65.23, p < 0.001, W = 0.09; Nuosu Yi – SW Mandarin/Mandarin: ps < 0.001).

Figure 2. Percentage of responses for each answer choice by context and language.

Table 1. A summary of the Likert ratings on the 5-point scale by language and context.

The above indicated that Nuosu Yi was used more in private domains such as Family and Friend, whereas SW Mandarin and Mandarin were used more often in functional domains such as Society. The varied language practice across contexts may be considered as an indicator of LS, as there appeared to be a loss in the functional (or communicative) use of Nuosu Yi (cf. Saravanan and Hoon Citation1997; Yu Citation2010).

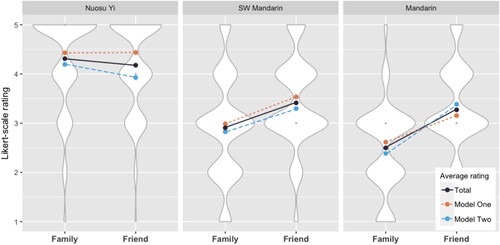

Another sign of LS was revealed when comparing each language’s use between the context of Family and Friend. illustrates the distribution and the average value of the ratings for each language in the two contexts. Although Nuosu Yi was a dominant language in both contexts, the context of Friend witnessed a decrease in the use of Nuosu Yi compared to Family (see also ). A Wilcoxon signed-rank test confirmed that the decrease was significant (p = 0.02, r = 0.19). This was accompanied by a significant increase in the use of SW Mandarin and Mandarin (SW Mandarin: p < 0.001, r = 0.46; Mandarin: p < 0.001, r = 0.63; see also ). An increased use of the mainstream language in younger generation is considered as a key indicator for LS (Austin and Sallabank Citation2011), suggesting that the Yi students appeared to undergo a gradual shift from Nuosu Yi to Mandarin in a broad sense (i.e. Mandarin and SW Mandarin).

Figure 3. Average ratings for each language in Family and Friend, by Total, Model One and Two students; distribution of ratings illustrated in violin plots.

The phenomenon of LS seemed to be more prominent among Yi students in Model Two education. As can be seen in , compared to Model One students, Model Two students showed a salient decrease in the use of Nuosu Yi and a greater increase in the use of Mandarin from the context of Family to Friend. A series of Wilcoxon signed-ranked tests confirmed the observations. Model One students showed almost no difference in the use of Nuosu Yi between the two contexts (p > 0.05, r = 0.09) whereas Model Two students showed a significant difference (p = 0.005, r = 0.27). Students from both models of education increased the use of SW Mandarin and Mandarin significantly from the Family to the Friend context (ps < 0.001). However, the effect sizes indicated that the increase of SW Mandarin was similar between the groups (Model One: r = 0.48; Model Two: r = 0.45), whereas there was a greater increase of Mandarin by Model Two students (r = 0.71) than Model One students (r = 0.53).

In sum, it was found that firstly, Nuosu Yi was the dominant language in the context of Family and Friend while SW Mandarin and Mandarin were the main languages used in Society. Secondly, there was a decrease in the use of Nuosu Yi and increase in the use of Mandarin (and its variety) in peer communication than in intergenerational communication. Finally, the students from Model Two education (Mandarin MoI) seemed to lead the LS, as they reduced the use of L1 and increased the use of Mandarin to a greater extent than Yi students in Model One education (Nuosu Yi MoI). Another point worth mentioning is that SW Mandarin was the only language that was commonly used in both private and public domains. It ranked the second in the Family context and first (same as Mandarin) in the Society context. This was different from the situation where Nuosu Yi and Mandarin were strongly associated with either private or public domains.

Interviews

This section presents the findings of the interviews, relevant to the second research question: why do Yi students make a certain language choice in a particular context?

Nuosu Yi: an identity marker of the Yi ethnicity

The quantitative results showed that Nuosu Yi was used as a main language in the Family and Friend contexts. Through interviews, we found that it might relate to Yi students’ high recognition of their Yi identity, and being able to speak Nuosu Yi was seen by them as an important identity marker:

I’m proud of being a Yi, and I’m very proud of our language. In a sense, it is because I can speak YiFootnote8 makes me a Yi person.

- Student 10 from School A (Model One Yi MoI)

How can a person say he/she’s a Yi without even being able to speak Yi?

- Student 13 from School B (Model Two Mandarin MoI)

Even though I will go out of Liangshan in the future, I still want to keep my ‘Yi elements’, and being able to speak Yi is a very important ‘element’ of being a Yi.

- Student 16 from School B (Model Two Mandarin MoI)

The questionnaires showed that the use of Nuosu Yi was most dominant in the Family context. Apart from viewing Nuosu Yi as an identity marker, another reason could be parents’ positive attitudes towards using Nuosu Yi at home:

My parents always require me to speak Yi at home. They said that there aren’t many chances to speak Yi outside now, so they insist on speaking Yi at home.

- Student 1 from School A

During school holidays, my parents send me to my grandparents’ house, because they said I can learn the most standard Yi from them.

- Student 19 from School B

SW Mandarin: bearing both sentimental and instrumental value

Similar to Nuosu Yi, SW Mandarin was found to be endowed by Yi students with sentimental value, leading to its frequent use in private domains such as Family. This was particularly salient when comparing to Mandarin, which was perceived by them as a more formal and distant language:

“Speaking Mandarin to my friends or parents feels, well, too strange and too formal. I would prefer speaking either SW Mandarin or Nuosu Yi with them, because it feels more natural and intimate.

- Student 11 from School A

SW Mandarin was not only found to be endowed with sentimental but also instrumental value. The latter made SW Mandarin a cross-ethnic lingua franca, and made it a language choice as popular as Mandarin in the Society context:

I can speak both [SW Mandarin and Mandarin], so I’m very flexible. If they [people in the society] speak SW Mandarin, I speak SW Mandarin. If they speak Mandarin, I speak Mandarin.

- Student 13 from School B

Many owners of stores and restaurants are Han people. Most of them understand Mandarin and SW Mandarin, but many of them don’t understand Yi.

- Student 4 from School A

Mandarin: the most instrumental language with least sentimental value

The high instrumental value attached to a mainstream language has been widely documented in LS research (McDuling and Barnes Citation2012; Valdés Citation2001; Wang Citation2019). This is also one of the main reasons for minority language speakers to shift away from their L1. Similarly, Mandarin, as the national lingua franca in China, was perceived by Yi students as the most functional and important language:

No one outside the Yi group understands the Yi language. No one outside Sichuan understands Sichuan dialect [SW Mandarin]. But everyone in this country understands Mandarin.

- Student 16 from School B

The questionnaires showed that the Model Two students appeared to lead the LS, as they had a greater increase in the use of Mandarin than their peers from Model One education in the Friend context compared to the Family context. A possible reason was the difference in the MoI between two models of education:

We use Mandarin in the classroom. The teachers also speak Mandarin to us after class. I mean, it’s like everyone speaks Mandarin in this school, so you just naturally live with it.

- Student 15 School B (Model Two Mandarin MoI)

I’m in a Yi-specialty school. Many teachers and school leaders in this school are Yi, and they encourage us to speak and learn Yi.

- Student 10 from School A (Model One Yi MoI)

Discussion

This study explored Yi students’ language choices and motivations in three different contexts in Liangshan. It is found that, without distinguishing discursive contexts, Nuosu Yi is the most used language by young Yi speakers. From this point of view, there is no prominent sign of LS. However, the situation becomes more subtle when looking into specific discursive contexts. In particular, there appears to be a loss in the functional use of Nuosu Yi, given that Nuosu Yi is mainly used in private domains, but Mandarin and SW Mandarin are more dominant in functional domains (cf. Dorian Citation1982; Gomashie Citation2022). Accordingly, Yi students are found to attach more sentimental value but less instrumental value to Nuosu Yi. Although this leads to a high recognition of their mother tongue, previous studies showed that it does not always lead to L1 learning and maintenance (Karan Citation2008; Saravanan and Hoon Citation1997). Another sign of LS is the increased use of Mandarin and SW Mandarin in conversations among the younger generation, particularly among Model Two Mandarin MoI students.

Apart from Nuosu Yi, this study also explored LS for dialects. An intriguing and seldom-studied phenomenon is the use of SW Mandarin by Yi students. The study found that SW Mandarin is endowed by Yi students with both sentimental and instrumental value, leading to a unique bridging role between Nuosu Yi and Mandarin in their daily communication. Despite this, SW Mandarin appears to be gradually evolving into a low variety or grassroots dialect, given Yi students’ positioning of Mandarin as an outer-circle lingua franca and SW Mandarin as a local-circle transitional dialect. The continuous decline of SW Mandarin is also related to the standardised language ideology in formal education of Liangshan, which leads to the exclusion of dialectal varieties in formal classroom instruction.

In sum, although Nuosu Yi and SW Mandarin are still the main languages spoken by Yi students in some contexts, they are both showing signs of decline. The decline of Nuosu Yi is mainly reflected in the lack of its functional use, namely the loss of the ‘instrumental value’ (Saravanan and Hoon Citation1997, 380). Over time, it may evolve into a language used in private domains only (see Gomashie Citation2022; Luo Citation2018). The decline of SW Mandarin, on the other hand, is mainly reflected in its marginalisation in formal education. This marginalisation seems to be related to the low tolerance of language variants in the education system. Under such language ideology, SW Mandarin is viewed merely as a transitional language which will be replaced once Mandarin is completely popularised. Over time, SW Mandarin may evolve into a, what Yu (Citation2010) called, ‘底层语言 (grassroots language)’ (68), meaning that its use will not be associated with formal education, modernisation, science, and technology. If the trend found in this study continues, a language shift may take place among the Yi youth in the long term. And as can be seen from the findings of this paper, the loss of either Nuosu Yi or SW Mandarin is both a functional and sentimental loss for Yi students.

A limitation of the study is that although it explored cross-generational language change by comparing Yi students’ language use between the Family and Friend contexts, it was not designed as a diachronic study. As a common and important research paradigm in the LS field, diachronic research has not been widely conducted in Liangshan. We propose more diachronic research to be conducted in the future, and a continuous attention to be paid to the language change of the young Yi people. Another limitation is the scale of the study, which only investigated the language choices and attitudes of 353 Yi students in two schools through survey. Although this was mitigated to some extent by follow-up interviews, a larger-scale study that includes more Yi students and schools in Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture is proposed.

This study found the important role of SW Mandarin in Yi students’ daily communication, but it is worth exploring whether this local Mandarin dialect will gradually lose status in the long run. A relevant study in this direction is Yu’s (Citation2010) research in Suzhou, which compared the use of Suzhou dialect and Mandarin in grassroot grocery markets and high-end shopping malls. Similar research can be conducted in Liangshan to explore whether there is different allocation of dialects in a specific discursive context (e.g. formal education). Finally, given that this is a LS study from a micro perspective (Hornberger Citation2012), we suggest more research from a macro perspective to be conducted in Liangshan. Language shift does not occur in a vacuum. Factors such as national (and regional) language ideologies, formal education, urbanisation, and migration determine the survival of a language or language variant (Fasold Citation1984; McDuling and Barnes Citation2012; Pauwels Citation2004). How these factors influence the language use of Yi youth needs to be further explored.

Conclusion

The Yi students in this study were found to be in a typical state of ‘relatively stable bilingualism’ (McDuling and Barnes Citation2012, 169). They are multilingual and their daily language practice is flexible. The perspective of LS as a dynamic process (Hornberger Citation2012) helps to reveal the complexity of their language use. The current study alone may not be sufficient to answer questions such as ‘to what extent LS has occurred among Yi students’, or to predict whether or when LS will occur. However, it corresponds to Hornberger (Citation2012)’s advocation that the central inquiry of LS research should be on the dynamics of multilinguals’ daily language practices and choices. Unlike previous studies which documented the exclusion of minority languages from home language use (Li Citation2017; Wang Citation2019), the Nuosu Yi language in this study has gained sufficient use and recognition in the home domain. This may be one of the main reasons why LS has not yet occurred among Yi students. However, the declining use of Nuosu Yi for functional purposes and among the younger generation appears to foreshadow the possibility of LS in the long term, even though Nuosu Yi continues to be a main language used by Yi students in their daily communication. This phenomenon requires continued attention in future research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Southwestern (SW) Mandarin, spoken by around 20% of the population in China, is one of the strongest Mandarin dialects which shares similar phonological and writing systems with Mandarin (Zheng and Zhu Citation2018).

2 The categorisation of conversations into Family, Friend and Society effectively served the aim of the current study, yet it should be noted that conversations can be cross-contextual. For instance, a conversation with friends can occur both inside and outside of school, or occur in the middle of the conversation with restaurant waiters. The results based on the categorisation thus reflect a broad picture of language practice among the investigated group while there may be additional nuances present.

3 Refers to the idea of “大华语圈” (The greater Chinese circle or Sinophone Circle), which contains different varieties of Chinese such as Mandarin, Cantonese, Hokkien, Teochew.

4 The Han group (汉族) is the majority group which contains over 90% of the population in China and speaks different varieties of Chinese.

5 Wang’s (Citation2019) study documented the linguistic practices of a Tibetan family in Tianzhu County, China. He found that the participants switched flexibly between Tibetan and Chinese depending on the contexts and the interlocutors. In some cases, their language use even resembled a case of translanguaging, i.e., the boundaries of languages were blurred.

6 Tuanjie Hua is a variety of Sichuan Dialect, which is a sub-dialect of SW Mandarin.

7 The questionnaire was printed in Chinese and translated to English for this paper.

8 Students generally used ‘Yi’ to refer to the Nuosu Yi language.

References

- Austin, P., and J. Sallabank eds. 2011. The Cambridge Handbook of Endangered Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ba, Z. 2016. “如何打造双语家庭—裕固族语言文化遗产传承问题研究 [How to Build a Bilingual Family - A Study on the Inheritance of Yugur Language and Cultural Heritage].” 西南民族大学学报(人文社科版) 37 (5): 58–63.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Dong, J. 2018. “Language and Identity Construction of China’s Rural-Urban Migrant Children: An Ethnographic Study in an Urban Public School.” Journal of Language, Identity & Education 17 (5): 336–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2018.1470517.

- Dorian, N. 1982. “Language Loss and Maintenance in Language Contact Situations.” In The Loss of Language Skills, edited by R. D. Lambert, and B. F. Freed, 44–59. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

- Erling, E., M. Brummer, and A. Foltz. 2022. “Pockets of Possibility: Students of English in Diverse, Multilingual Secondary Schools in Austria.” Applied Linguistics 2022: 72–102. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amac037.

- Fasold, R. 1984. The Sociolinguistics of Society. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Feng, A., and B. Adamson. 2018. “Language Policies and Sociolinguistic Domains in the Context of Minority Groups in China.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 39 (2): 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2017.1340478.

- Gomashie, G. 2022. “Bilingual Youth’s Language Choices and Attitudes Towards Nahuatl in Santiago Tlaxco, Mexico.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 43 (2): 182–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2020.1800716.

- Hornberger, N. 2012. “Language Shift and Language Revitalization.” In The Oxford Handbook of Applied Linguistics, edited by R. Kaplan, 413–420. Oxford Handbooks. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195384253.013.0028

- Karan, M. 2008. “The Importance of Motivations in Language Revitalization.” Presented at The 2nd International Conference on Language Development, Language Revitalization, and Multilingual Education in Ethnolinguistic Communities, Bangkok.

- Li, P. 2017. “我国图瓦人语言使用现状研究 – 白哈巴村个案调查[Research on the current situation of Tuva Language in China – A Case Study of Baihaba Village].” 中央民族大学学报(哲学社会科学版) 44 (02): 155–162.

- Liu, X., and H. Koirala. 2012. “Ordinal Regression Analysis: Using Generalized Ordinal Logistic Regression Models to Estimate Educational Data.” Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods 11 (1): 241–254. doi: 10.22237/jmasm/1335846000

- Luo, J. 2018. “彝语转用汉语的渐变规律 – 以峨山彝族自治县大龙潭乡为例[Gradual Shift of Yi Language to Chinese – Taking Dalongtan Township as an Example].” 西南边疆民族研究 18 (04): 129–139.

- McDuling, A., and L. Barnes. 2012. “What is the Future of Greek in South Africa? Language Shift and Maintenance in the Greek Community of Johannesburg.” Language Matters 43 (2): 166–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/10228195.2012.740815.

- O'Connell, A. (2006). Logistic Regression Models for Ordinal Response Variables (Vol. 146). London: Sage.

- O'Leary, Z. 2021. The Essential Guide to Doing Your Research Project. London: Sage.

- Ong, T. W. S. 2021. “Family Language Policy, Language Maintenance and Language Shift: Perspectives from Ethnic Chinese Single Mothers in Malaysia.” Issues in Language Studies 10 (1): 59–75. https://doi.org/10.33736/ils.3075.2021.

- Pauwels, A. 2004. “Language Maintenance.” In The Handbook of Applied Linguistics, edited by A. Davies, and C. Elder, 719–737. Maiden, NC: Blackwell.

- R Core Team. 2022. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Saravanan, L., and J. Hoon. 1997. “Language Shift in the Teochew Community in Singapore: A Family Domain Analysis.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 18 (5): 364–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434639708666326.

- Sha, Z. 2005. “仁和彝族语言转用及其教育[Language Shift and Education of Renhe Yi Language].” 民族教育研究 16 (2): 33–37.

- Tsung, L. 2016. Language Power and Hierarchy: Multilingual Education in China. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Valdés, G. 2001. “Heritage Language Students: Profiles and Possibilities.” In Heritage Languages in America: Preserving a National Resource, edited by J. Peyton, J. Ranard, and S. McGinnis, 37–80. McHenry, IL: Delta Systems.

- Wang, L. 2018. “双语教育与多元文化背景下的‘承认’与‘再分配’ [‘Recognition’ and ‘Redistribution’ in the Bilingual Education and Multicultural Background: Taking Yi as an Example].” 中南民族大学学报 38 (3): 70–73.

- Wang, H. 2019. “民族交融视域下的语言使用与身份认同[Language Use and Identity in the Perspective of Ethnic Integration].” 中南民族大学学报(人文社会科学版) 39 (04): 16–22.

- Yao, J., M. Turner, and G. Bonar. 2022. “Ethnic Minority Language Policies and Practices in China: Revisiting Ruiz’s Language Orientation Theory Through a Critical Biliteracy Lens.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2050915.

- Yu, W. 2010. “普通话的推广与苏州方言的保持—苏州市中小学生语言生活状况调查 [The Promotion of Mandarin and the Maintenance of Suzhou Dialect - An Investigation of the Language use of Primary and Secondary Students in Suzhou].” 语言文字应用 3: 60–69.

- Zhang, D. 2010. “Language Maintenance and Language Shift Among Chinese Immigrant Parents and Their Second-Generation Children in the U.S.” Bilingual Research Journal 33 (1): 42–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235881003733258.

- Zhang, P., and B. Adamson. 2023. “Multilingual Education in Minority-Dominated Regions in Xinjiang, People’s Republic of China.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 44 (10): 968–980. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2020.1850744.

- Zhang, L., and L. Tsung. 2019. Bilingual Education and Minority Language Maintenance in China: The Role of Schools in Saving the Yi Language. Cham: Springer.

- Zhang, Q., and T. Yang. 2020. “Bilingual Education for the Tujia: The Case of Tujia Minority Schools in Xiangxi Autonomous Prefecture.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 23 (4): 381–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2017.1358694.

- Zheng, J., and H. Zhu. 2018. “凉山州“团结话”词汇特点探析 [An Analysis of the Vocabulary Characteristics of “Tuanjie Hua” in Liangshan Prefecture].” 西南科技大学学报:哲学社会科学版 35 (1): 20–31.

Appendix

Appendix A Survey questions relevant to the study