ABSTRACT

Scots is one of three indigenous languages in Scotland, alongside English and Gaelic, spoken by 1.5 million people (National Records of Scotland 2011). Historically, Scots was excluded from formal education, but since the launch of a Scots qualification in 2014, the language is now taught in a growing number of schools.

Findings from a school-university research partnership into the use of Scots show that lack of a standardised orthography, lack of exposure to written Scots, teacher attitudes, and lack of confidence in writing Scots are factors that influence Scots literacy development.

This research was undertaken in 2018–2019, at Banff Academy in North-East Scotland, where Scots is spoken by approximately 50% of pupils. I used Participatory Action Research and Linguistic Ethnography (Creese 2010; Shaw, Copland, and Snell 2015) as a method and theoretical framework to explore attitudes towards Scots, set within a broader language policy framework. Data from ethnographic interviews with pupils, teachers and Scots language experts suggests that innovative pedagogical approaches can stimulate students to develop positive language attitudes and language awareness and that improving language attitudes can influence linguistic behaviours. These approaches to creative language teaching could be applicable in other regional or minority language contexts.

Introduction

Scots is one of three historical indigenous languages in Scotland, alongside English and Gaelic. Scots is a minority language, spoken by 1.5 million people in 2011 (National Records of Scotland Citation2011), which increased to 2.8 million people reporting some level of skills in Scots in 2022 (Scotland's Census Citation2022) . It is less visible than English, has lower status than English, and until recently, was commonly thought of as slang, bad English, or a dialect of English rather than a language in its own right (Lowing Citation2017; Matheson and Matheson Citation2000; Sebba Citation2018; TNS-BMRB Citation2009; Unger Citation2013). In this article, I discuss Scots in relation to English and look at contemporary efforts to teach Scots literacy, as part of a wider language revitalisation movement. The two main strands of my work cover literacy skills development, and building confidence and self-esteem in Scots speakers, to promote positive attitudinal change towards contemporary Scots.

The focus of this special issue is developing literacy in ‘regional collateral languages’ which are close to their respective national languages both structurally and with regard to identity questions (cf. Wicherkiewicz Citation2019). Since Scots is spoken throughout Scotland, labelling it ‘regional’ is problematic, although Scots has a number of regional dialects. Similarly, it would be extremely problematic to think of Scotland as merely a region of the United Kingdom, although it was known as ‘North Britain’ in the post-Union period (Millar Citation2023, 65). The Encylopedia Britannica (Citation2024) states that ‘[a]lthough profoundly influenced by the English, Scotland has long refused to consider itself as anything other than a separate country’. However, it is true to say that the Scots language and the English language are close, both structurally and functionally, as discussed in the following section.

2. Is Scots a language?

Scots and English are closely related, West Germanic languages descended from different dialects of Old English (Macafee and Aitken Citation2002). They can be thought of as ‘kin-tongues’ (Kloss Citation1993) because they have a degree of mutual recognisability, but the borderline between the two languages is blurred (Millar Citation2018, 2). This situation is fluid however, and, as in many cases of regional and minority languages in Europe, such as Latgalian in Latvia (Martena, Marten, and Šuplinska Citation2022) or Kashubian in Poland (Schaaf and Wicherkiewicz Citation2004), the question of where a language ends and a dialect begins is demarcated more by political will than linguistic features. The status of Scots is currently improving due to policy development and educational reform. Scots is now recognised as a language by Moseley, Nicolas and UNESCO (2010) and the Council of Europe (Citation1992) among others, but not necessarily by everyday speakers. Lowing (Citation2017) describes a state of ‘schizoglossia’: an insecurity in the use of Scots, and Macafee (Citation2000) found that ‘Scots is not well-defined in the public mind’. Until the middle of the twentieth century, most Scots speakers were diglossic (Ferguson Citation1959; Millar Citation2020, 11) using English, which had higher status, in formal situations, and Scots in the home. Currently, most Scots speakers move along a bipolar linguistic continuum (Aitken Citation1976) depending on the context, but the languages are no longer kept totally separate (Millar Citation2018, 217).

3. The status of Scots

The changing status of Scots is intertwined with historical and political developments in Scotland. To give a simplified overview: during the Older Scots Period (before 1700) Scots literature flourished (Millar Citation2020, 75; McClure 1997; Dictionaries of the Scots Language 2022], 27). Prior to the Union of the Crowns in 1603, Scots was the language of the court and the legal system (see Millar Citation2023; Citation2018; McClure 1997; or Murison Citation1977 for a discussion on the historical development of Scots). After 1603, the royal court moved to London, King James VI of Scotland/I of England started to write in Standard English rather than Scots, and members of the elite followed suit (Aitken Citation1985, 43; Millar Citation2023, 83). After the Union of Parliaments in 1707, the governance of Scotland moved to London (Millar Citation2023, 85), English became the dominant language in Scotland, and Scots gradually lost status (Bann and Corbett Citation2015). In the eighteenth century Scots poetry was written during the vernacular revival (Smith Citation2020). McClure comments that at this time ‘to write in Scots, […] was an act with overt and inescapable cultural, even political implications’ (McClure, 1997, 29).

In 1872, the Education (Scotland) Act was passed, making education compulsory for children aged 5-13. English became the enforced language of education, and pupils were often physically punished for speaking Scots in schools until corporal punishment was outlawed in the 1980s (Unger Citation2013, 130). The Scottish Education Department (Citation1947), stated Scots ‘is not the language of “educated” people anywhere and could not be described as a suitable medium of education or culture’. In official circles, Scots ceased to exist, although it was still spoken in informal settings (Aitken Citation1985, 41; Millar Citation2018, 192).

In the early twentieth century, a group of Scottish writers, led by Hugh MacDiarmid, developed a form of literary written Scots, influenced by European modernism, that became known as ‘synthetic Scots’ (Millar Citation2023, 74). These writers inspired subsequent waves of language activists (Unger Citation2010, 101). During the 1970s ‘a seismic change in educational attitudes occurred’ (McClure Citation2005, 78). Thereafter, teachers were encouraged to recognise the validity of regional dialects (McClure Citation1974, 68). By the 1990s, interest in teaching Scots in schools had developed alongside an increasing sense of national identity (Caie Citation1998 iv). Following devolution, the Scottish Parliament reopened in 1999, giving Scotland greater political autonomy in several areas including education. The UK Government signed the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages in 2001, leading to policy and educational developments. Education Scotland (Citation2017) states that learning Scots can ‘support young people in developing their confidence and a sense of their own identity’. Prior to these reforms, Scots was typically only studied around St Andrew’s Day, celebrating the patron saint of Scotland, or Burns Night, when the birth of the poet Robert Burns is celebrated (Tyson Citation1998, 73). Now, however, there is growing awareness of the importance of Scots as a living language and an important part of Scotland’s cultural heritage and identity. Speakers of minority languages have become aware of what is at stake when languages are endangered (Dunmore Citation2021, 4; UNESCO Citation2003, 1). As a reaction against the juggernaut of globalisation, interest in local languages as symbols of culture, identity and belonging, has grown in significance (Kloss Citation1993, 168).

The Scots Language Award was launched by the Scottish Qualifications Authority in 2014 as a formal qualification within the Scottish Curriculum for Excellence and is taught in an increasing number of schools and community settings. Core skills of reading, writing, speaking and listening are taught, giving pupils opportunities to develop literacy and actively produce Scots. The curriculum is flexible, allowing teachers considerable autonomy (Niven Citation2017, 10).

In recent years, increased institutional provision from Education Scotland (Citation2015; Citation2017), the Dictionaries of the Scots Language ( 2022), and the Open University and Education Scotland (Citation2019; Citation2024) ensure that Scots language teachers and learners have access to a wide range of resources. A Scottish Languages Bill is currently being debated by the Scottish Government (Citation2024). If passed, this law will give official status to Scots and increase support for Scots language education in schools.

Materials and method: local language, school and community

A collaborative school-university research partnership was developed between the Elphinstone Institute, University of Aberdeen, and Banff Academy, a high school in the North-East of Scotland, during the academic year 2018–2019. Dr Jamie Fairbairn, Head of Humanities and a Scots Language teacher at Banff Academy, and I, PhD Ethnology researcher, received funding to investigate whether teaching the Scots language in school boosts pupils’ self-esteem and wider achievement (BERA British Curriculum Forum Curriculum Investigation Grant 2018–2019).

I visited the Scots Language class of twelve pupils aged 16–18, weekly for six months. I used a variety of ethnographic research methods, over three main phases of my research process. I asked similar questions during each phase, based on earlier research on attitudes toward Scots (Aye Can 2011; Durham Citation2014; Macafee and McGarrity Citation1999). First, I sat in class, ‘lurking and soaking’ (Snell and Lefstein Citation2012), doing participant observation and building relationships with the pupils and teacher. Phase two involved Participatory Action Research (Baum, MacDougall, and Smith Citation2006), where I facilitated an art workshop in partnership with Martin Ayres from the participatory arts company Caged Beastie. In phase three, I interviewed the pupils, teachers, and visiting Scots language experts. My interviews were informal, dialogic and iterative. I shared my own perspectives and included autoethnography in my data set. The pupils were trained in ethnographic research methods, and their interviews, sound recordings, and photographs were added to my raw data. I coded the data using Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) six-step process for thematic analysis, and, for this paper, used NVIVO to extract data relating to reading, writing, literacy, early experiences with Scots, teacher attitudes and social media.

My argument is that as well as improving reading and writing skills, boosting confidence and self-esteem is also important for developing literacy in Scots. Using Participatory Action Research, a cyclical process of planning, action and reflection, with participants at the centre, yielding valuable insights from the young people themselves, whose opinions about Scots and actions to maintain Scots are a vital part of securing the future of the language.

This work is underpinned by a commitment to social justice and aims to bring meaningful change to the pupils’ relationship with Scots. Drawing on the principles of Linguistic Ethnography (Snell and Lefstein Citation2012, 3–4), I ‘look closely and look locally, while tying observations to broader relations of power and ideology’ (Creese Citation2010, 140) to make connections between classroom-based ethnography and language policy, and research the confluence between bottom-up language activism and education and top-down language policy and curricular guidelines. Working to increase literacy in Scots is one stage of reversing language shift (Fishman Citation1991). Creating a new generation of confident Scots speakers is an important step to maintaining intergenerational transmission.

Results: what are the factors that have hindered Scots literacy development?

I explore the answers to this question in the following section. In my interview data, I identified four major factors that hinder Scots literacy development in school. These are: lack of a standardised orthography, lack of exposure to written Scots, confidence, and teacher attitudes.

Lack of a standardised orthography

Extract 1. When you’re just speaking it, you’re not really thinking about what you’re saying.[…]. But when you’re reading it, you’re actually processing the words, like how they’re spelt.[…]. It’s definitely easier to speak it than it is to read it or write it. Because the spelling’s just, could be spelt anyway really. Everyone’s just got a different opinion on how it should be spelt.

If there was a set way, I think people would take it more seriously. (Pupil)

Extract 2. It’s not as easy as I thought it’d be. Mainly because of spelling. Spelling Scots words for me is ridiculous because there’s no standard form. (Pupil)

Extract 3. Trying to get the kids to write in Scots, they got very uptight and panicky, ‘oh I don’t know how to spell stuff’, ‘is that how you spell that?’ […] If you don’t have that framework then it’s very difficult. (Teacher/lecturer)

Extract 4. We asked if he speaks Doric or Scots. And he said Doric, because he didn’t know if he spoke Scots. (Pupil)

Extract 5. We did Doric spelling in my class. They do spelling every week so this week I made them do Doric spellings. (Teacher, additional support for learning)

Lack of exposure to written Scots

Extract 6. In primary, you’d have to write down and try and get the spelling right, but they were all English words, never Scottish words. We never, ever read books that had Scottish words in it, just English words. (Pupil, Scots language class)

Extract 7. I find it really hard to write or even read in Doric. Cos you’re not used to it. At school back then there would have been nothing written in Doric. I dinna [don’t] think I’ve actually ever written anything. (School librarian)

Confidence

Extract 8.

I don’t write it very well.

How do you know?

I don’t.

So is it that you don’t know that you are good? Or is it that you think you are making mistakes?

It just feels like I’m writing it wrong.

Ok. But if there’s no right way or wrong way to do it, why mightn’t you be doing it completely right? (Pupil and researcher)

Extract 9. It’s making me think, even as an adult, and It’s making me more comfortable to come in and speak the way I speak, and not turn into proper English. So brilliant. Fantastic. (School librarian)

Extract 10. Anything that builds confidence in learners, especially the ones who’ve been a bit disenfranchised from the learning experience because of the way they speak, it’s bound to have a positive effect. (Scots language expert)

Extract 11. They’d had to write a piece in Doric well, write a piece, and she wrote the whole piece in Doric. And it was fantastic, very well written, and you know very articulate. […] She was really, really disengaged. I think that was probably one of the most successful experiences that she had at school. You know, that she, she kind of stood out. She shone. (Guidance teacher)

Teacher attitudes

Extract 12. What did her mentor say?

She got told by her mentor to not speak Scots because it’s not proper.

Did she tell you what she thought about that?

She thought it was weird because she grew up speaking it, and was normal to her. She found it quite difficult at the start, because that’s all she was used to.

When she’s teaching now, how does she speak? (Pupil reporting back to researcher)

Proper English.

Extract 13. I mind in primary, some folk would get telt off. Yes, there was one teacher that I had in primary that was awful. She would potentially kick you out of the class if you didn’t speak proper English. (Pupil)

Extract 14. And I’ve noticed in the local area, folk have been sayin, I mean, 10 years ago, we all called it slang, and now we’re saying no it’s Scots language.

The classroom as the nexus of change in linguistic behaviour

Developing literacy skills

Extract 15. What’s been the best bit?

When we were doing poems or writing a letter in Scots. We had to send a letter about a bad experience. I like writing in Scots. (Interview between researcher and pupil)

Extract 16. If you’re going to spell it your own way, you’ve got to keep the consistency because as soon as you start spelling things differently within the same text or even in the same book, I’ve come to realise, you’re failing your reader. (Creative writer)

Extract 17. I just think you go with what’s successful, not wi what’s right. I dinnae care what the correct way is. I dinnae care what the historical way is. I care aboot the one maist folk readin will be able tae understand. (Journalist and Scots language teacher)

Social media

In a separate strand of this research, Dr Fairbairn and I circulated an electronic questionnaire to pupils and staff in the school, to gain a wider perspective on Scots usage from the general school population. Following Durham (Citation2014, 313), we asked whether they used Scots or English more on different social media platforms, as well as in different spoken contexts, such as a job interview, talking with friends, or talking to a teacher. We found that written Scots usage varied across different forms of electronic communication. In texts, WhatsApp and Snapchat our participants wrote Scots more than English (Fairbairn and Needler Citation2019). Young people included innovative Scots acronyms as part of their text speak, for example, ‘KFL’ for ‘ken fit like’ [you know what I mean] ‘IDK’ ‘I dinna ken’ [I don’t know], ‘FYD’ for ‘fit ye deein’ [what are you doing]. This was true even for pupils who spoke less Scots, as seen in extract 18.

Extract 18.

I just don’t speak it that often, to be honest.

How about when you text?

Occasionally.

Occasionally more than when you speak?

Yeah. More than when I speak. (Pupil and researcher)

Since pupils are writing in Scots every day, online, we can say that these pupils are already literate in Scots, albeit in an informal register in a private online domain, rather than a more public-facing Scots. There are different literacies associated with different domains of life (Barton and Hamilton Citation2000, 11), and the online domain of instant messaging is a particular social context with its own rules and conventions, that are towards the oral end of an oral/literate continuum (Murray Citation1988). The increasing use of social media is creating new opportunities for writing in Scots, as shown in extract 19.

Extract 19. So more and more, I am texting in Doric, if I can spell it, and if it doesnae jump back into some predictive text. (School librarian)

Increasing Scots in the linguistic landscape

Extract 20. Up until a few years ago, I would never ha seen Doric written down. (School librarian)

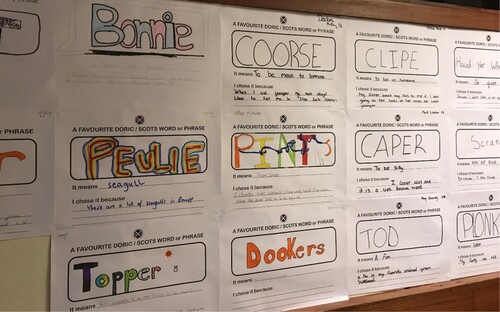

Figure 1. Favourite word posters (Photograph: Needler and Fairbairn Citation2020).

In an arts workshop, facilitated by a professional artist, we created a high-quality exhibition of portrait photographs of pupils representing a Scots word, accompanied by dictionary-style definitions, plus example sentences written by the pupils. a shows a pupil eating a buttery, a type of bread roll with a high salt and fat content, typically eaten in the North-East of Scotland, that tastes similar to a croissant. b shows a pupil who is ‘drookit’ – absolutely soaking wet. The exhibition is on permanent display in the school boardroom, a formal meeting space where English would typically be used. Foregrounding written Scots in this space ‘is an important marker of power and acknowledgement by those in authority’ (Mooney and Evans Citation2019, 112) as confirmed by the head teacher in extract 21.

Extract 21. It’s outstanding, absolutely outstanding. We’ve got it in our boardroom. All of our meetings are in there with councillors, directors, social workers, [and] the wider community, so they get to see it. It’s got a high-profile position in the school. I’m really pleased with it. (Head Teacher)

Figure 2. a. Exhibition panel ‘buttery’ (Image Caged Beastie Citation2018); b. Exhibition panel ‘drookit’ (Image Caged Beastie Citation2018).

Scots medium education

Extract 22. Do ye hink there should be the option o writin in Doric instead o English in some classes?

I think the choice should be provided. (Teacher)

I suppose it would depend on the class, wouldn’t it? (Teacher)

I definitely think there should be in English, because I’m an ex English teacher and I can really see the point of it there. (Teacher)

I find it easier. Even sometimes in English, I’ll just be writing my essay and a Doric word will slip in by accident and I didna realise, and get like a mark aff. I think you should be allowed to write in Doric. It’s easier. Well, for me onywye [anyway].

Extract 23. You could argue that young people who come from this area are disadvantaged because they have to sit their exams in a second language. (Head teacher)

Recommendations

During my interviews, I asked participants what they thought the future holds for Scots, and what can be done to support Scots as a language. In his discussion over possible futures for Scots, Millar (Citation2020, 204) comments ‘the actual speaker body has been largely ignored in the debates [about ways to guarantee the survival of Scots].’ By foregrounding the voices of Scots learners, as well as considering the views of teachers and Scots language experts, the data in this study provides insights into the views of the ‘actual speaker body.’ The pupils recommended raising awareness of Scots as a language, sharing good practices from Banff Academy, teaching more Scots in more areas of Scotland, increasing the visibility of Scots in the linguistic landscape and producing Scots creative arts and literature.

In extract 24, the pupil talks about the importance of learning Scots as an element of cultural belonging. The pupil in extract 25 says ‘just speak it more’, and also sees a need for sharing the good practice from Banff Academy, both in other parts of Scotland and internationally. The pupil in extract 26 is hopeful that Scots will grow in popularity, and that Scots language classes will spread. The need for more opportunities for learning Scots was identified. As the pupil in extract 27 says, ‘it helps the language get stronger if more people are learning about it.’

Extract 24. Study it if you want to know more about Scottish history and heritage. I mean, learning Scots, it could help folk with identifying their cultural background. (pupil)

Extract 25. Jist bein spoken mair and being advertised fit we’re deein, like getting it oot and lettin mair countries, mair regions o Scotland see it. (pupil)

Extract 26. It’ll definitely become more and more popular as time goes on and Scots language classes could be happening all across Scotland. (pupil)

Extract 27. I’d say that it’s a pretty good thing to do. It helps the language get stronger if more people are learning about it. So I’d say definitely teach it, cos more people will learn about it and understand that Scots and English are two different languages and not the same. (pupil)

McClure (Citation1997, 24) wrote, teaching Scots, and teaching about Scots will ‘change the tongue itself, and change speakers’ attitudes towards it’. The author in extract 28 agrees that attitudinal change is a vital first step towards developing a cultural understanding of Scots, so I asked pupils what they thought was the best way to promote positive attitudinal change. The pupil in extract 29 talks about increasing the visibility of written Scots in the linguistic landscape through Scots shop and roads signage. This could act as a conduit to bring new ideas about the validity of Scots from the school out into the community.

Extract 28. It’s about attitude towards it, it’s the route, the thing that needs to be changed first … I can see the positives of trying to change perceptions and confidence around speaking and just getting an understanding, a cultural understanding of where it comes from. (author)

Extract 29. Just bring it out to the community. Like for example the road signs, make more Doric road signs or signage for shops or Doric streets or something like that. Just bring it outside of the school and out to the community a bit more. (pupil)

Extract 30. I genuinely think gettin Scots language media stuff which is confident and good and relevant, and just usin it, and no bein funny aboot it, will mak a huge difference. (journalist)

Extract 31. Just more like, they should do something like a theatre thing. Make more movies in Scots and maybe do a theatre in Scots. Stuff like that. We already know there’s lots of books that were written in English getting put in Scots, like Harry Potter, or Diary of a Wimpy Kid is now Diary of a Wimpy Bairn. It’s quite interesting, so hopefully that keeps going and gets more common. So people use it more. (pupil)

Discussion and conclusions

Fear about the future of Scots is not new. ‘From at least the first half of the eighteenth century, Scots has always been thought to be dying out’ (Concise Scots Dictionary Citation2017, xv). However, UNESCO currently classifies Scots as ‘not particularly endangered’ (Moseley, Nicolas and UNESCO 2010, 37). Recent policy developments and educational reform have given Scots greater prominence in the school curriculum. However, a lack of awareness of Scots as a language, and the impact of linguistic prejudice, creates challenges for developing Scots literacy.

The research described in this article had two aims. The first was to discover factors that influence literacy developments in Scots, and the second was ‘to look closely and look locally’ (Creese Citation2010) at moments of transformation in Scots language teaching in Banff Academy. These research findings were generated through Participatory Action Research with one class of pupils in one school in Scotland, but our values-based approach and methodologies are transferable to other regional minority language contexts.

Our findings have yielded useful insights into the process of how ideological and attitudinal change can influence linguistic behaviour. The Participatory Action Research process shared power with all participants. The pupils are no longer advocates without power (Spolsky Citation2019, 326), but become agents driving change. The teacher was ‘taught in dialogue with the students’ (Freire Citation1993, 61) and used this learning to drive curricular innovations that have since been embedded within the Scots language curriculum at Banff Academy.

In light of recent changes in policies and attitudes towards Scots, the data of this study suggests that improving language attitudes leads to a change in linguistic behaviours, and that innovative pedagogical approaches can stimulate students to develop positive language attitudes and language awareness. Millar (Citation2018, 198) suggested that the Scots language work in Banff was ‘individual enterprise masquerading as official policy and practice’ but has since ‘come round to the idea that the only way forward for the language is through its encouragement in education’ (Millar Citation2023, 115). Change is happening at a local level, and the classroom is at the confluence between top-down policy initiatives and bottom-up activism. The pupils themselves are important agents of change, as can be seen in extract 22, where pupil voice spurred on curricular innovation, encouraged by committed teachers. The Open University and Education Scotland have subsequently developed a teacher training course for Scots which Dr Fairbairn piloted at Banff Academy with a collaborative group of teachers. If this has good teacher uptake nationally, it has the potential to improve the status of Scots in schools. Initial Teacher Education courses must include Scots language teaching so that future teachers consider their own relationship with Scots.

There are still barriers to overcome. Developing an orthographic standard for Scots would make it easier to teach Scots consistently and produce learning materials suitable for use in the whole country. However, we need to pay close attention to regional dialects too, and not discourage people by telling them they are writing incorrectly. The fluidity afforded by the current lack of a standardised orthography has advantages for creative writing.

We should also acknowledge the ideological work that needs to be done. Raising awareness of Scots as a language, raising the status of Scots, and expanding the registers of Scots and the range of domains where Scots is used all contribute to language maintenance. Working to support the confidence and self-esteem of Scots native speakers and learners, to overcome negative internalised attitudes, creates a learning environment where writers can experiment and grow in confidence.

Since there are so many people who consider Scots to be a language to be proud of and express the wish to develop literacy in Scots, there are good reasons for demanding more efforts to provide adequate literacy development opportunities. Scots is an important part of Scotland’s cultural heritage and is now increasingly supported by government and educational bodies.

There are strong parallels between the current position of Scots and other minority languages such as Kashubian in Poland or Latgalian in Latvia. Teaching these languages in school will give pupils both the skills and confidence needed to develop literacy competence. In the Scottish context, we can learn from bilingual education programmes such as Gaelic Medium Education, and the dedication and enthusiasm of language activists and teachers.

Geolocation information

The research was conducted in Banff Academy in North-East Scotland, UK.

Ethical Approval

I confirm that the research described in this was granted ethical approval by the University of Aberdeen Committee for Research Ethics & Governance in Arts, Social Sciences & Business, on 2nd August 2018, with the title article ‘Unconscious Bilingualism: Acknowledging Language in the Heartland of Scots’. All participants, (or their parents or guardians if under 18) gave informed consent for the use of their interview data and photographs to be used for academic publication, by signing the Elphinstone Institute contributor consent form.

Our ethics approval system does not generate approval numbers, however if required, you may use the reference number at the top of this letter (EC/CN/020818) as a unique reference number for this ethical approval.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aitken, A. J. 1976 2015. “The Scots Language and the Teacher of English in Scotland.” In Collected Writings on the Scots Language Originally Published in Scottish Literature in the Secondary School, Scottish Education Department, Scottish Central Committee on English, edited by Caroline Macafee, 48–55. Edinburgh: HMSO, accessed September 3, 2018. http://medio.scotslanguage.com/library/document/aitken/The_Scots_language_and_the_teacher_of_English_in_Scotland.

- Aitken, A. J. 1985. “Is Scots a Language?” English Today 3: 41–5.

- Anderson, Benedict. 1983 2016. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

- Aye Can. 2011. Accessed January 31, 2018. http://www.ayecan.com/.

- Bann, Jennifer, and John Corbett. 2015. Spelling Scots: The Orthography of Literary Scots 1700- 2000. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Barton, David. 2000. “Researching Literacy Practices: Learning from Activities with Teachers and Students.” In Situated Literacies: Reading and Writing in Context, edited by David Barton, Mary Hamilton, and Roz Ivanič, 167–179. London: Routledge.

- Barton, David, and Mary Hamilton. 2000. “Literacy Practices.” In Situated Literacies: Reading and Writing in Context, edited by David Barton, Mary Hamilton, and Roz Ivanič, 7–15. London: Routledge.

- Baum, F., C. MacDougall, and D. Smith. 2006. “Glossary: Participatory Action Research.” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 60 (10): 854–7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2566051/pdf/854.pdf.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. https://uwe-repository.worktribe.com/output/1043060.British Educational Research Association. “Curriculum Investigation Grant.” https://www.bera.ac.uk/award/bcf-curriculum-investigation-grant.

- Caged Beastie. 2018. www.cagedbeastie.com.

- Caie, Graham. 1998. “Academic Foreword.” In The Scots Language: Its Place in Education, edited by Liz Niven, and Robin Jackson, iii–iv. Dumfries: Watergaw.

- Concise Scots Dictionary. 2017. Edinburgh University Press.

- Council of Europe. 1992. European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, Accessed May 11, 2023. https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/treaty/148.

- Coupland, Nikolas. 2010. “Welsh Linguistic Landscapes from Above and Below.” In Semiotic Landscapes: Text, Image, Space, edited by A. Jaworski, and C. Thurlow, 77–101. London: Continuum.

- Creese, A. 2010. “Linguistic Ethnography.” In Research Methods in Linguistic, edited by Lia Litosseliti, 138–154. London: Continuum.

- Dictionaries of the Scots Language. 2022. Dictionaries for Schools App. www.dsl.ac.uk

- Dongera, Rixt, Marlous Visser, and Boyd Robertson. 2001 2018. Gàidhlig: The Gaelic Language in Education in Scotland. Leeuwarden: Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning.

- Dragojevic, Marko. 2017. Language Attitudes. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://oxfordre.com/communication/view/10.1093acrefore/9780190228613.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228613-e-437.

- Dunmore, Stuart. 2021. Language Revitalisation in Gaelic Scotland: Linguistic Practice and Ideology. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Durham, Mercedes. 2014. “Thirty Years Later: Real-Time Change and Stability in Attitudes Towards the Dialect in Shetland.” In Sociolinguistics in Scotland, edited by Robert Lawson, 296–318. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Education Scotland. 2015. “CfE Briefing 17, Curriculum for Excellence: Scots Language.” CfE Briefing 17 - Curriculum for Excellence: Scots Language https://education.gov.scot.

- Education Scotland. 2017 2023. “Scots Language in the Curriculum for Excellence: Enhancing Skills in Literacy, Developing Successful Learners and Confident Individuals.” Livingstone: Education Scotland. https://education.gov.scot/resources/scots-language-in-curriculum-for-excellence.

- Education Scotland. 2023. “Gaelic Medium Education.” Accessed June 13, 2023. https://education.gov.scot/parentzone/my-school/choosing-a-school/gaelic-medium-education/gaelic-medium-education-foghlam-tro-mheadhan-na-gaidhlig/.

- Evans, Rhys. 2009. Audit of Current Scots Language Provision in Scotland. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government.

- Banff Academy, Jamie Fairbairn, and Claire Needler. 2019. “Fair Trickit! An Exploration of Scots – Our Local Language and What It Means To Us.” Banff. Fair_Trickit.pdf (d3lmsxlb5aor5x.cloudfront.net).

- Ferguson, Charles A. 1959. “Diglossia.” Word (Worcester) 15 (2): 325–340.

- Fishman, Joshua A. 1969 2000. “Bilingualism with and Without Diglossia; Diglossia with and Without Bilingualism.” In The Bilingualism Reader, edited by Wei Li, 87–94. London: Routledge.

- Fishman, Joshua A. 1991. Reversing Language Shift: Theoretical and Empirical Foundations of Assistance to Threatened Languages. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Freire, P. 1993. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. 2nd ed. London: Penguin.

- Giles, Howard. 2003. “Language Attitudes.” In International Encyclopedia of Linguistics, edited by William J. Frawley. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://www-oxfordreference-com.nls.idm.oclc.org/view/10.1093/acref/9780195139778.001.0001/acref-9780195139778-e-0572.

- Itchy Coo. 2002–2022. “The Gruffalo and Gruffalo’s Child in Scots Language Dialects.” Accessed April 30, 2024. www.itchy-coo.com.

- Kloss, Heinz. 1993. “Abstand Languages and Ausbau Languages A Retrospective of the Journal Anthropological Linguistics: Selected Papers, 1959-1985.” Anthropological Linguistics 35 (1/4): 158–170.

- Kynoch, Douglas. 1996. A Doric Dictionary. revised edition. Dalkeith: Scottish Cultural Press.

- Landry, Rodrigue, and Richard Y. Bourhis. 1997. “Linguistic Landscape and Ethnolinguistic Vitality: An Empirical Study.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 16 (1): 23–49.

- Lawson, Kirsten J. 2014. “Scots: A Language or a Dialect? Attitudes to Scots in Pre-Referendum Scotland.” Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies 20 (2): 143–161.

- Leslie, Dawn. 2021. “What’s in a Name? The Prevalence of the ‘Doric’ Label in the North-East of Scotland.” Scottish Language 40: 49–83. https://asls.org.uk/publications/periodicals/scotlang/.

- Lorvik, Marjory. 1995. The Scottis Lass Betrayed? Scots in English Classrooms. Dundee: Scottish Consultative Council on the Curriculum.

- Lowing, Karen. 2017. “The Scots Language and its Cultural and Social Capital in Scottish Schools: A Case Study of Scots in Scottish Secondary Classrooms.” Scottish Language 36 (1): 1–20. https://hull-repository.worktribe.com/output/4174488.

- Macafee, Caroline. 2000. “The Demography of Scots: The Lessons of the Census Campaign.” Scottish Language 19: 1–44.

- Macafee, Caroline, and A. J. Aitken. 2002. “A History of Scots to 1700.” In A Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue. Vol. XII, xxix-clvii. Online.

- Macafee, Caroline, and Briege McGarrity. 1999. “Scots Language Attitudes and Language Maintenance.” Leeds Studies in English 30: 165–179.

- Macleod, Iseabail. 1998. “The Scots Dictionary.” In The Scots Language: Its Place in Education, edited by Liz Niven, and Robin Jackson. Dumfries: Watergaw.

- Macleod, Iseabail C., Matthew James Moulton, Brown Alice, and Ewen A. Cameron. 2024. “Scotland.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Accessed April 29, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/place/Scotland.

- Martena, Sanita (Ladziņa), Heiko F. Marten, and Ilga Šuplinska. 2022. The Latgalian Language in Education in Latvia. Leeuwarden: Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning.

- Matheson, Catherine, and David Matheson. 2000. “Languages of Scotland: Culture and the Classroom.” Comparative Education 36 (2): 211–221.

- McClure, J. Derrick, ed. 1974. The Scots Language in Education. Aberdeen: Aberdeen College of Education and the Association for Scottish Literary Studies.

- McClure, J. Derrick. 1997. Why Scots Matters. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Saltire Society.

- McClure, J. Derrick. 2005. “Stands Doric Where it did?” In North-East Identities and Scottish Schooling: The Relationship of the Scottish Educational System to the Culture of North-East Scotland, edited by David Northcroft, 76–86. Aberdeen: Elphinstone Institute.

- McClure, J. Derrick, A. J. Aitken, and John Thomas Low. 1980. The Scots Language: Planning for Modern Usage. Edinburgh: The Ramsay Head Press.

- McPake, Joanna, and Jo Arthur. 2006. ““Scots in Contemporary Social and Educational Context.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 19 (2): 155–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908310608668760.

- Mętrak, Maciej, Maciej Bandur, and Piotr Szatkowski. 2024. “Beloved Books and Contested Standards: Translations of ‘The Little Prince’ Into Selected Collateral Languages of Poland.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2024.2338832.

- Millar, Robert McColl. 2005. Language, Nation, and Power: An Introduction. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Millar, Robert McColl. 2018. Modern Scots: An Analytical Survey. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Millar, Robert McColl. 2020. A Sociolinguistic History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Millar, Robert McColl. 2023. A History of the Scots Language. Oxford: Oxford UniversityPress.

- Mooney, Annabelle, and Betsy E. Evans. 2019. Language, Society and Power. Fifth Edition. London: Routledge.

- Moseley, Christopher, Alexandre Nicolas, and UNESCO. 2010. Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger. Memory of Peoples. 3rd ed., entirely rev., enl. and updated ed. Paris: UNESCO. https://www.perlego.com/book/1670121/atlas-of-the-worlds-languages-in-danger-pdf.

- Murison, David. 1977. The Guid Scots Tongue. Edinburgh: James Thin.

- Murray, Denise E. 1988. “The Context of Oral and Written Language: A Framework for Mode and Medium Switching.” Language in Society 17 (3): 351–373. https://api.istex.fr/ark:/67375/6GQ-LX3C0P07-T/fulltext.pdf.

- National Records of Scotland. 2011. Scotland’s census area profiles. Accessed September 6, 2018. http://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/ods-web/area.html#!.

- Needler, Claire, and Jamie Fairbairn. 2020. Local Language, School and Community: Curricular Innovation Towards Closing the Attainment Gap. London: British Educational Research Association. Retrieved from https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/local-language-school-and-community.

- Niven, Liz. 2017. Scots: The Scots Language in Education in Scotland. 2nd ed., 5–43. Leeuwarden: Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning.

- Niven, Liz, and Robin Jackson. 1998. “Introduction.” In The Scots Language: Its Place in Education, edited by Niven, Liz, and Robin Jackson, 1–6. Dumfries: Watergaw.

- Open University and Education Scotland. 2024. Scots Language Teacher Professional Learning Programme, Accessed April 16, 2024. https://www.open.edu/openlearncreate/course/index.php?categoryid=458.

- Schaaf, Alie, and Tomasz Wicherkiewicz. 2004. Kashubian: The Kashubian Language in Education in Poland. Leeuwarden: Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning.

- Scotland's Census. 2022. Ethnic Group, National Identity, Language and Religion | Scotland's Census. Accessed May 21, 2024. scotlandscensus.gov.uk.

- Scots Hoose. www.scotshoose.com.

- Open University and Education Scotland. 2019. Language and Culture. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.open.edu/openlearncreate/course/index.php?categoryid=382Scots.

- Scottish Education Department. 1947. Secondary Education. A Report of the Advisory Council on Education in Scotland. 1946-47 XI.

- The Scottish Parliament. 2024. Bills and Laws: Scottish Languages Bill. Accessed April 16, 2024. https://www.parliament.scot/bills-and-laws/bills/scottish-languages-bill/overview.

- The Scottish Qualifications Authority. 2014 “Scots Language Award SCQF Level 3, 4, 5 and 6.” SQA. Accessed May 2, 2024, https://www.sqa.org.uk/sqa/70056.html.

- Sebba, Mark. 2018. “Named Into Being? Language Questions And the Politics of Scots in the 2011 Census in Scotland.” Language Policy 18: 1–24.

- Shaw, S. E., F. Copland, and J. Snell. 2015. “An Introduction to Linguistic Ethnography: Interdisciplinary Explorations.” In Linguistic Ethnography: Interdisciplinary Explorations, edited by Julia Snell, Sara Shaw, and Fiona Copland, 1–13. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Shoba, Jo Arthur. 2010. “Scottish Classroom Voices: A Case Study of Teaching and Learning Scots.” Language and Education 24 (5): 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500781003695559.

- Smith, Jeremy. 2020. “Recuperating Older Scots in the Early Eighteenth Century.” In The Dynamics of Text and Framing Phenomena: Historical Approaches to Paratext and Metadiscourse in English, edited by Matti Peikola, and Birte Bös, 267–287. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Snell, Julia, and Adam Lefstein. 2012. “Interpretative & Representational Dilemmas in a Linguistic Ethnographic Analysis: Moving from ‘Interesting Data’ to a Publishable Research Article.” Working Papers in Urban Language and Literacies 90: 1–24.

- Spolsky, Bernard. 2019. “A Modified and Enriched Theory of Language Policy (and Management).” Language Policy 18 (3): 323–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-018-9489-z.

- Tagliamonte, Sali. 2016. Teen Talk: The Language of Adolescents. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- TNS-BMRB. 2009. Public Attitudes Towards the Scots Language. Edinburgh: Scottish Government Social Research.

- Tyson, Robert. 1998. “Scots Language in the Classroom: Viewpoint 1.” In The Scots Language: Its Place in Education, edited by Liz Niven, and Robin Jackson, 71–76. Dumfries: Watergaw.

- UNESCO Ad Hoc Expert Group on Endangered Languages. 2003. Language Vitality and Endangerment. Paris: UNESCO.

- Unger. 2010. “Legitimating Inaction: Differing Identity Constructions of the Scots Language.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 13 (1): 99–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549409352968.

- Unger, J. W. 2013. The Discursive Construction of the Scots Language: Education, Politics and Everyday Life. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz. 2019. “Języki Regionalne w Polsce na tle Europejskim – z Perspektywy Glottopolitycznej i Ekolingwistycznej.” Postscriptum Polonistyczne 1 (23): 17–28. https://doi.org/10.31261/PS_P.2019.23.02.