ABSTRACT

This paper reports the study of the agency of children aged 10–14 in their language practices as they interacted with their family members. The study was located in a Vietnamese migrant community in Victoria, Australia. In using a thematic, interactional analysis combined with a relational approach to agency, it was found that children’s agency emerged on a continuum which ranged from a more negative end of the continuum – manifested through the children’s explicit resistance to parental requests for home language use – to a more positive end of the continuum – manifested through their flexible linguistic repertoire in accommodating their interlocutors’ needs. Findings also suggest that the linguistic practices in the family domain surfaced as dynamic co-constructions to reflect the adults’ and children’s constant (re)negotiation in their everyday language practices in the home, which was also influenced by other factors such as children’s linguistic competence and the families’ linguistic norms. The study builds on previous findings on the relational nature of children’s agency by bringing attention to the different manifestations of children’s agency that arise in situ as they interact.

Introduction

A long-standing tradition in the study of family language policy has been to view children as recipients of language strategies and practices. As a result, the majority of investigations in this research domain has been preoccupied with investigating parental agency in family language policy (e.g. Curdt-Christiansen and Wang Citation2018; Döpke Citation1992; Lanza Citation1997). For example, interest has focused on the parents’ capacity to make decisions about language use in the family (e.g. Curdt-Christiansen and Wang Citation2018) or the strategies they use to negotiate language practices (e.g. Döpke Citation1992; Lanza Citation1997). As a result of this dominance, there has been a call for research to address children’s agency (e.g. Schwartz and Verschik Citation2013; Smith-Christmas Citation2017), which has led to greater attention being paid to children as agents in family language policy research (e.g. Kheirkhah Citation2016; Revis Citation2019; Said and Zhu Citation2019; Smith-Christmas Citation2014, Citation2018, Citation2020, Citation2022). This notwithstanding, the focus on children remains an important topic that deserves further exploration to uncover how children contribute to family language policy through their practices (Moustaoui Srhir & Poveda, Citation2022; Smith-Christmas Citation2020). In particular, as pointed out by Smith-Christmas (Citation2022), the relational nature of children’s agency should be further investigated to yield a deeper understanding of this complex issue.

The aim of our study is to contribute to investigations of children’s agency in forming family language policy by exploring how children in a Vietnamese migrant community respond to and shape their family language practices. This will be done through a relational approach to agency that permits an analysis of children’s interactions with family as they make language choices and negotiate existing language rules (Duff Citation2012; Kuczynski Citation2003).

The context

Australia is a multicultural nation with people coming from a rich variety of social, cultural and linguistic backgrounds. The most recent census indicates that Australia was the ninth country in the world for total number of immigrants (ABS Citation2022). The census data also revealed that just over a third (7.5 million) of the Australian population in 2021 was born overseas (ABS Citation2022).

Historically, Vietnamese immigrants came to Australia in substantial numbers after the war in 1975. This period also coincided with the removal of the ‘White Australia policy’ – a policy that barred people from Asian, African and Pacific Islander backgrounds from entering Australia (D'Angelo Citation1991). Following the initial big wave, Vietnamese people have continued to come to Australia in large numbers and for different purposes as reflected in their investment, student, or skilled-worker visas. Data from the Department of Home Affairs shows that 270,340 Vietnamese-born people have been living in Australia as of June 2020. This is an increase of approximately a third in comparison to 203,770 in 2010 (Department of Home Affairs Citation2022). The Vietnamese born population, in fact, ranks sixth among all immigrant groups in Australia (Department of Home Affairs Citation2022).

In turning our attention to home language maintenance in Australia (which has been a matter of both research and public attention), successful language maintenance is significantly hampered for community languages such as Vietnamese by four key factors: the lack of home language instruction in mainstream education (Eisenchlas & Schalley, Citation2019; Rubino Citation2010), the ineffectiveness of community language schools as a result of teacher shortages (Cruickshank, Citation2019), inadequate resources for teaching, and the small number of languages offered (Eisenchlas & Schalley, Citation2019). Both the substantial Vietnamese community in Australia and the lack of resources outside the family for maintaining the vibrancy of the Vietnamese language, point to the need for a study that can uncover the language practices of this immigrant group. Findings could be used to enable shifts in policy and inform education programs for families.

The theoretical orientation: a relational approach to agency

This study adopts a relational approach to agency which contends that agency should be explored by taking into consideration the interactions of the agents, the context and other affordances (Larsen-Freeman Citation2019). Agency is not a new concept. This notion has been around for decades and it has received different theorisations surrounding its nature. There was a time when agency was viewed as people’s free will to act, a miscomprehension of the features of agency (Ahearn, Citation2001). Since then, there have been different approaches to conceptualising agency.

Bouchard and Glasgow (Citation2019) explore the connection between agency, culture, and structure through a realist social standpoint and suggest that research on agency should take that relationship into account. In a similar vein, Bourdieu’s theory of practice highlights the relationship that exists between an agent’s capital, their dispositions, and the field (domain) that they operate in (Bourdieu, Citation1984). Larsen-Freeman (Citation2019) contends that agency is not an individual construct by arguing that it is ‘not inherent in a person’ (65) while Buhrmann and Di Paolo (Citation2017) posit that agency is fundamentally ‘another dimension of our relation with the world’ (216), which arises out of the interactions between people. Despite the differences in conceptualising agency, an underlying thread in this body of work is that agency is understood as a relational, emergent, dialogic, contextualised and dynamic construct which emerges out of the interactions between individuals and their specific situations (e.g. Buhrmann and Di Paolo Citation2017; Edwards and D'Arcy Citation2004; Larsen-Freeman Citation2019). Our study will take a relational approach in understanding and discussing agency.

Researchers also agree that there may be different manifestations of agency (Duff Citation2012; Duff and Doherty Citation2015; Fogle Citation2012). It can be of a positive, cooperative, negotiated or resistant nature. Furthermore, it can be interpreted in different ways; for example, through the affordances of a specific context (Fogle Citation2012; Larsen-Freeman Citation2019) or through analytic perspectives that are focused on the ways in which interactants and their actions are examined as they interact with one another. In this paper, we use Duff’s (Citation2012) definition of agency as ‘people’s ability to make choices, take control, self-regulate, and thereby pursue their goals as individuals’, which may lead to ‘personal or social transformation’ (417).

In discussing agency in the family context, Kuczynski (Citation2003, 20) argues for a bilateral perspective in looking at parent–child relationships and considers parents and children ‘as actors with the ability to make sense of the environment, initiate change, and make choices’. According to Kuczynski (Citation2003), parents and children should be considered equal agents in the language socialisation process. He also argues for the need to explore children’s own voices, practices and experiences instead of only using data based on the adults’ practices and perspectives, the still dominant tradition in studies on family. This will serve as the theoretical foundation for our later discussion and analysis of children’s agency in multilingual family language practices in the Australian context.

Studies on children’s agency in immigrant contexts

A number of studies have been concerned with children’s agency in everyday interactions. In a study on the language shifting practices of Rwandans in Belgium, Gafaranga (2010) used Conversation Analysis to analyse recordings of naturally occurring interactions. Gafaranga (2010) found that the children displayed active agency in negotiating a preferred medium (or language) of interaction with their caretakers when requesting language or medium switches from Kinyarwanda to French. He identified four ways (all related to the initiation of repair to address problems of understanding) that the children used in response to their participants: (1) embedded medium repair, (2) generalised content repair, (3) targeted content repair, and (4) understanding checks. Said and Zhu’s (Citation2019) study of an Arabic-and English-speaking family in the UK revealed that children demonstrated their positive agency in understanding their parents’ language preferences and making use of that knowledge in everyday family interactions to tighten their relationships with their parents.

Danjo’s (Citation2021) study of one Japanese – English family with a 4-year-old child in the UK, revealed that the one-parent-one-language model (e.g. Döpke Citation1992) was negotiated, and exercised strategically and creatively by the children in contextualised language practices. By transferring the Japanese pronunciation rules for vowel-ending to English words (e.g. ‘eapureinu’ for ‘airplane’ or ‘torauzazu’ for ‘trousers’), which would not be usually considered as popular ‘loan words’ in Japan, the child (Ken) successfully avoided being corrected by his mother (Danjo Citation2021, 8). Also in a Japanese-English bilingual context, Gyogi’s (Citation2015) study of Japanese mothers who were raising their children bilingually in London, found that the children demonstrated their agency by constructing their own positive images of being a bilingual through their flexible use of Japanese and English. The children’s creative use of languages in Danjo’s (Citation2021) and Gyogi’s (Citation2015) studies, is an illustration of a translanguaging process at play. (Translanguaging is defined by Li (Citation2018, 15) as ‘a practice that involves dynamic and functionally integrated use of different languages and language varieties, but more importantly a process of knowledge construction that goes beyond language(s)’.)

While the above studies provide positive displays of children’s use of the home languages, children have also been reported to display resistance towards the adults’ language choice. For example, in Rubino’s (Citation2015) study of conflicting mother–child talk in a Sicilian-Australian family in Sydney, the mother’s language switching produced somewhat negative judgements, and was used to issue commands or engage in arguments while the children switched language to defy her. Rubino (Citation2015) concluded that while the children’s switching could have been attributed to their lack of competence in Sicilian and Italian, it was nonetheless a tactic to challenge their mother’s more dominant status in the family.

Children’s resistance to the family’s language policy is also reported in Fogle and King’s (Citation2013) work which drew on data of three studies of transnational families in the US. In one family, the children employed strategies such as ‘non-response’ to challenge the father’s prompts (Fogle and King Citation2013, 13). In another, the children demonstrated their resistance by insisting on using Russian despite the mother’s overt policy of ‘English dinners’ where she mainly spoke English to guests and thus expected the others to follow the routine (Fogle and King Citation2013, 15).

Smith-Christmas (Citation2022) contributes a theoretical framework on children’s agency by arguing that children’s agency should be investigated by taking into consideration four elements: ‘compliance regimes; linguistic norms; linguistic competence and generational positioning’ (356). In compliance regimes, compliance refers to children’s act of speaking the minority language while resistance refers to children speaking the majority language, which is considered an agentive act. Over time, the compliance regimes may result in the emergence of some linguistic norms in the family. Smith-Christmas (Citation2022) also suggests that interpreting children’s agency as resistance or linguistic norms is an intricate issue and needs to take into consideration the other factors that intersect with compliance regimes and linguistic norms, which are linguistic competence and generational positioning. The former refers to children’s knowledge of grammatical structures and vocabulary while the latter could be understood as a generational order that influences language preference (Smith-Christmas Citation2022).

Smith-Christmas’s (Citation2022) theoretical model is a valuable addition to the existing literature on children’s agency because it provides an articulate theoretical foundation to explore and interpret this nuanced concept. In suggesting that children’s agency should be explored in the interactions with other factors and affordances, it is also in line with a relational approach to agency that our study adopts. However, as stated by Smith-Christmas (Citation2022) herself, one of the possible weaknesses of her theoretical framework is that its starting point seems to rely on a dichotic lens that is associated with children’s language choice; i.e. the tendency to view a child speaking the majority language as a resistant agentive act to family language policy. Notably, Smith-Christmas (Citation2022) calls for further research that explores the relational nature of children’s agency in other concrete contexts. In response to this call, our study adds to the existing discussion of children’s agency as they interact with their Vietnamese Australian family members by taking the perspective that agency should be seen as being located on a continuum rather than from a dichotic perspective. Our study seeks to answer the following research question:

How does the children’s agency emerge through their language choice in two Vietnamese Australian families?

Method

The study is part of a larger research project which investigates language ideologies and practices of Vietnamese immigrant families in Victoria, Australia. Data for this study is drawn from video and audio recordings depicting two mothers (Ms Tam, Ms Ngan), a father (Mr Hung) and a grandmother (Mrs Nghi)Footnote1 as they interact with the children – Huong, Vy, Tung, Elly and Tilly (as well as Elly and Tilly’s cousins: Lan Anh, Minh Anh, Tuan Anh and Toba). presents the demographic information about the two families.

Table 1. Participants’ demographic information.

Family 1

In Family 1, all the children were born in Australia. Tung, the youngest child was the main participant in the study. The children’s mother (Ms Tam) arrived in Australia with her parents and other relatives as refugees in 1987 at the age of 11. Their father (Mr Hung) came to Australia in 1994 when he was 18. At the time of the study, Ms Tam and Mr Hung were employed full-time. Despite being very busy with work, Ms Tam tried to maintain Vietnamese in the family by allocating time for home language activities such as reading bed-time stories with Tung, singing karaoke in Vietnamese with her children or sometimes making calls to their relatives in Vietnam. She also sent him to an afterhours Vietnamese community language school for three hours every week. The parents were also very focused on helping their children obtain good academic results and supervised their children as they worked on tasks in mathematics and literacy. The family interacted with each other using both Vietnamese and English. However, Tung and his elder siblings spoke to each other entirely in English.

Family 2

In family 2, the parents ran a family garment business that was passed down by Mrs Nghi, the grandmother. The two daughters – Elly and Tilly – were born in Australia and had lived with their grandmother from birth. Due to the nature of their business, Ms Ngan and Mr Duy were absent from the home for long periods throughout the working week and even at weekends. They relied on Elly and Tilly’s grandmother, Mrs Nghi, to take care of the children during out of school hours. Both Vietnamese and English were used by the family. Elly and Tilly talked to their grandmother in Vietnamese because she could not speak English. They talked to their parents in Vietnamese and English. They also had close connections with cousins who were cared for by the grandmother during weekends or on school holidays. However, as reported by Ms Ngan, Elly and Tilly were more proficient in Vietnamese compared to their other cousins because they lived closer to Mrs Nghi and thus had greater opportunities to practise Vietnamese. Elly and Tilly mainly spoke English with each other and with their other cousins.

Data collection methods

As part of ethics application, both families were provided with an explanatory statement that informed them that the study entailed recording naturally occurring interactions in the family home. They gave written consent to participate in the research project and were provided with tablets and audio-recorders to record their interactions at a time of their choosing.

Video recordings of family language practices are important in exploring the multi-layered expressions and the emergence of language practices as participants interact. The multimodal analysis of the interplay between various embodied aspects of the interactions such as movement, gaze, gestures and the handling of objects, in addition to the spoken word, can help to examine the bilingual interactional contexts in more fine-grained ways (Filipi Citation2015; Kheirkhah and Cekaite Citation2015, Citation2018; Meyer Pitton Citation2013). Audio recordings were used as backup data when what was said was unclear in the videos. In total, 7 hours 41 minutes of recordings were generated during a variety of activities including meal-time, sibling play, study time, story reading time, and family gatherings.

Data analysis

The collected data were transcribed by the first author who also conducted the translations from Vietnamese into English; these appear in bold in the transcripts and follow the Vietnamese. Samples of the translated data were double-checked by a proficient English and Vietnamese user to ensure accuracy of the translations. In transcribing the interactions, some notations from Conversation Analysis (Jefferson Citation1985) were used to capture not only what was said but also how it was said including embodied features (Filipi Citation2007). These included intonation, emphatic stress, pauses and embodied actions conveyed through the curly bracket (from Filipi Citation2007) in the transcripts. (The notations are located in the appendix.) To analyse the sources of data, thematic analysis as proposed by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006, 87) was employed to generate themes. The themes generated were then interpreted using a relational approach to agency to examine how displays of agency were shaped by the interactions.

Findings

The findings have revealed the different ways the children displayed agency in their everyday language practices. As will be seen in the excerpts, the children made decisions, took control of and self-regulated their language practices. Their displays of agency ranged from explicit resistance to adults’ language practices to other manifestations of agency including making their own language decisions and using languages flexibly to accommodate other speakers’ needs. Before proceeding, it is important to clarify that in this paper, the terms ‘translanguaging’ (Li Citation2018) alongside Gafaranga and Torras's (Citation2002) concept of mixed mode and parallel mode, will be used to denote how participants utilise and move across languages in their interactions. The first section will analyse instances of how the children regulated family language practices.

Regulating family language practices

In excerpts 1–3, Tung and his sisters demonstrated their agency in regulating their family language practices. This was shown in the first two instances by Tung’s persistence in speaking English, which finally led to his parents switching to English; and in the third instance, by Tung’s and his siblings’ explicit refusal to speak the home language despite their father’s strong urging. Analysis begins by examining Tung’s persistence in speaking English despite his parents’ choice of Vietnamese.

Making parents switch to English

In the first excerpt, Tung wants to help his mother cook his favourite food. Tung and his siblings, Huong and Vy, are studying in the family’s open space dining-room (which also doubles as a study space) located next to the kitchen. The mother is talking to Huong about the cookies she is baking. At this point, Tung suspends his study to join her in the kitchen. This excerpt is an example of how Tung maintains English throughout the conversation while Ms Tam switches from Vietnamese to English.

Excerpt 1: Ms Tam baking with Tung.Footnote4

At the start of the excerpt, the interaction is in parallel mode (Gafaranga and Torras Citation2002) with Tung interacting in English (lines 2, 4, 6) and his mother in VietnameseFootnote6 (lines 1, 3, 5). However, while Tung maintained his use of English throughout the excerpt, Ms Tam turned to a mixed language (or medium) (Gafaranga and Torras Citation2002) utterance in line 7 and finally switched to whole-English utterances in lines 9, 11, 13.

Ms Tam’s switch from Vietnamese to English can be explained as a ‘preference for same language talk’ (Auer Citation1984, 23). This is based on the premise that there is a tension or disaffiliation between speakers when different languages are used in a conversation. This tension can be resolved when one participant surrenders to the other’s language choice. In the above excerpt, Ms Tam has given way to Tung’s preferred language, English. On the other hand, while Tung’s persistence in speaking English may not be an act of explicit resistance, his perseverance in speaking English and not switching to Vietnamese in his interaction with his mother displays his agency in the family’s linguistic landscape. In other words, Tung has reordered the generational positioning in the family by switching the act of compliance to his mother (Smith-Christmas Citation2022). While it could be argued that Tung’s Vietnamese competence could be at play here, the fact that he can write in simple Vietnamese and maintain basic conversations in VietnameseFootnote7, as observed by Author 1 for the same data set, suggests that it is not Tung’s low linguistic competence that is the main reason that hinders him from switching. Rather he is agentively choosing to use English.

The below excerpt is another example of Tung’s insistence on speaking English, which also leads Mr Hung, his father, to switch to English. Noted, this time, even when the content of the conversation is simple enough for Tung to speak wholly in Vietnamese, his language choice is still English.

Excerpt 2: Mr Hung asking Tung to do homework

This conversation takes place at the weekend. Tung’s father, Mr Hung, is supervising his homework. This is the habitual weekend practice where Tung does his homework given by his teachers at the Vietnamese community language school and other supplementary literacy or mathematics tasks in English assigned by Mr Hung. Initially, Tung is playing around and not ready to start studying. In line 1, Mr Hung asks Tung to sit at the table and start writing.

As can be seen, the father starts the conversation in Vietnamese and maintains his Vietnamese until line 5 (con ngồi được không? viết, viết cho ba đi / tùng!/cái nào? bảo ba còn biết, tùng, can you sit? write, write for me/ which one first, tell me so that I know, tung). Also noted is the mother’s Vietnamese utterance in line 2 (con ghi tiếng việt đi tùng ơi, tung, please do your vietnamese writing). Yet, Tung speaks English throughout the episode (i’ll do english first/english and vietnamese, okay?/ yeah/ yes) in contrast to Mr Hung and Ms Tam, who are speaking in Vietnamese. In lines 7 and 9, however, Mr Hung switches to English (yeah, neatly … and correctly.) The episode ends with English being the shared medium and Tung expressing agreement with his father to write neatly and correctly.

Like Ms Tam’s switch to English in excerpt 1, here Mr Hung switches to English at the end of the conversation as a response to Tung’s perseverance in speaking English. This time, even in the setting of simple linguistic content being exchanged (simple vocabulary in short utterances about a familiar topic), Tung insists on speaking English and neither switches to Vietnamese nor translanguages to produce mixed language turns. In doing so, Tung has, once again, re-arranged the generational order (Smith-Christmas Citation2022) in the family by shifting the act of compliance to his father, who finally resorts to using English.

In the next excerpt, we see yet another even stronger display of Tung and his elder sisters’ agency in family language practices: their explicit, verbal refusal to their father’s urging that they speak Vietnamese.

Explicitly resisting parental language requests

In excerpt 3, the context is again a weekend homework activity. Huong and Vy, Tung's older siblings, are already sitting at the table ready for learning as Tung joins them.

Excerpt 3: Mr Hung reminding his children to speak Vietnamese

As can be seen, Tung and Huong are having a conversation in English about Tung’s socialising habits (lines 1–9) when their father requests that they speak in Vietnamese (nói tiếng việt đi, speak vietnamese) (line 10). Tung explicitly refuses to do so in line 11 (no). When the father pursues another stronger request, this time addressed to all in line 12 (tung ơi, tung nói tiếng việt đi, hương nói tiếng việt đi hương. tất cả nói tiếng việt đi, tung, speak in vietnamese. huong, speak in vietnamese. everyone, speak in vietnamese), Tung again rejects the request through an emphatic no, we’re not and no (lines 13 and 14). This time there is no further follow up as the father simply acquiesces to the children’s continued conversation in English.

This excerpt provides an illustration of Tung and his siblings’ pro-monolingual practices, and the father’s ‘generational positioning’ (Smith-Christmas Citation2022, 356), where he enacts his authority as a father in urging the children to speak Vietnamese. The emphatic refusal by Tung may be explained by (1) the fact that the conversation in English was between the siblings that serves as a private space for the children in which the father’s actions are oriented to as an intrusion, and (2) the siblings’ orientations to the norms of using English (Smith-Christmas Citation2022). Therefore, the father’s request was possibly in breach on two fronts: first on the grounds that it was an interruption of the conversation from which he was excluded, and second on the grounds that English not Vietnamese was the expected language of interaction between the siblings. Whether or not the above reasons may fully explain Tung’s overt resistance to his father’s request, the excerpt has demonstrated the children’s agency in family language policy and provided interactional details about how the children have challenged the generational order by declining the senior family member’s request for Vietnamese use.

In brief, the analysis of extracts 1–3 has shown how the children regulated their family language practices by prompting a parental language switch through the repeated action of explicitly resisting parental language requests. In the next section, attention turns to the second family where the children use a set of bilingual resources to facilitate communication between various members of the family.

Deploying languages to accommodate speakers (Elly and Tilly)

In excerpt 4, the family is eating fruit after dinner while sharing the news of the day – a common family activity. Elly’s and Tilly’s two cousins, Minh Anh and Toba, are also present.

Excerpt 4: Eating fruit

Ms Ngan (the mother) and Elly are both cutting the papaya. They are located at opposite sides of the kitchen island.

In the above conversation, Elly mobilises her languages to adapt to the language needs of her co-participants: Vietnamese with her mother and English with her cousins. When talking to Ms Ngan, she uses Vietnamese only (lines 2, 4, 12), except for the exclamation look!. She uses English to talk to her cousins and her sister, Tilly (lines 9, 13, 16, 21, 23, 26). In line 6, Elly responds to Tilly’s question in a mixed-language turn, which is in English in the first part of her turn, addressed to Tilly and then in Vietnamese (hút bụi), addressed to the mother. This is recycled from the earlier conversation with Ms Ngan: i did, didn’t i? i hút bụi hoài mà. Auer (Citation1995) states that bilinguals commonly move between languages for emphasis. Elly’s use of the two languages in her turn here may serve such a function. She is emphasising that she is the one who usually does the vacuum-cleaning in the house.

In this episode, Elly brings her language resources into play to communicate effectively with her different family members. Her language switching is participant– or preference-related (Auer Citation1984) where English is used in exchanges with Tilly and Minh Anh, and Vietnamese is used to both elaborate her answer and to continue the topic with her mother. Here we see a more positive demonstration of agency through Elly’s flexible language practices, which seems to have successfully catered to different participants’ needs. Also noted here is Elly’s linguistic competence which seems to have fostered her positive demonstration of agency in family language policy. Furthermore, in contrast to Tung’s authoritative and somehow resistant acts of agency as discussed above, here Elly appears to adhere to the generational positioning (Smith-Christmas Citation2022) by attending to her mother’s language choice.

The next excerpt offers another example of how Elly (and Tilly) make use of their language resources as they speak in Vietnamese to their grandmother and English to their cousins Minh Anh, Lan Anh, Tuan Anh and Toba.

Excerpt 5: Grandmother and grandchildren having a meal together

In the excerpt the grandmother and her grandchildren are having a meal together during the school holidays.

Seating arrangement:

At the start of the excerpt, Grandmother initiates talk about the food in Vietnamese in line 1, which is responded in Vietnamese by Elly (in line 2, dạ cũng được á, it is quite good grandma). From line 5, we can see how Elly flexibly moves across the two languages and works as a ‘language broker’ (Revis Citation2019, 188). The interaction is in parallel mode (Gafaranga and Torras Citation2002): the main conversation between Elly and the other children (except for TillyFootnote9) is in English while Elly’s exchange with her grandmother is in Vietnamese. For example, Elly translates her grandmother’s questions for her junior cousins in lines 3, 11–12 (GUYS, GUYS, GUYS, what do you think about the food?/ GUYS, LET’S VOTE. with the corn, who likes the green stuff, put your hands up. who likes to put out the green stuff?). She also communicates her cousins’ opinions about the food to her grandmother in Vietnamese (in line 14, bà nội, mấy đứa mình nói là mình không có thích mấy cái này đó. grandma, they said they don’t like this stuff).

In sum, the episode is another example of Elly’s positive agency displayed through her switching in response to her co-participants as she accommodates to their different needs. Importantly these responses emerge turn by turn. Also noted here is Elly’s sound Vietnamese linguistic competence which seems to have provided opportunities for her positive demonstration of agency to flourish (Smith-Christmas Citation2022). Furthermore, the fact that Mrs Nghi cannot speak English and is a frequent presence in the family, may have contributed to Elly’s and Tilly’s richer linguistic competence, and played a role in shaping the family’s linguistic norms. This has created a bilingual space for Elly and Tilly to move across the languages in responding to the languages of the other participants – Vietnamese with, and for, the grandmother and English with, and for, the cousins. Agency thus emerges both relationally and interactionally.

Discussion

The analysis has illustrated the children’s different manifestations of agency in the context of family language practices. Displays of their agency emerged on a continuum from a more negative stance – their explicit resistance to parental requests for home language use, making their parents switch to English due to their persistance in speaking English (family 1) – to a more positive stance – the flexible use of their linguistic repertoires in response to their co-participants’ language choice (family 2). Our findings have furthered the ongoing discussion on children’s agency in family language practices in the following ways.

Regarding the congruences, first, our findings concur with prior research on home language maintenance where children were also found to socialise the adults to switch to the children’s language choice (e.g. Felling Citation2006; Pease-Alvarez Citation2003; Gafaranga 2010; Revis Citation2019). While Tung’s persistence in speaking English may not be an act of open resistance, his tenacity to speak English rather than convert to Vietnamese has rearranged the generational standing in the family by shifting the act of compliance to his parents (excerpts 1 and 2) (Smith-Christmas Citation2022). Also noted was Tung’s and his siblings’ explicit resistant agency in practice in refusing their father’s exhortations to speak Vietnamese when the father’s act of interrupting their conversation was considered an intrusion to the children’s private space (excerpt 3). When these language practices are maintained for long periods of time, they may shape the family’s linguistic norms (Smith-Christmas Citation2022).

Second, agency emerged through Elly and Tilly’s flexible use of their two languages to interact with the other speakers. This finding aligns with previous studies on children’s agency where the children were shown to mobilise their language resources to interact successfully with other speakers (e.g. Gyogi Citation2015; Said and Zhu Citation2019). Elly’s and Tilly’s linguistically rich family environment has given them different levels of exposure to both languages since birth, which has provided valuable opportunities for their linguistic capabilities to develop and flourish. As Smith-Christmas (Citation2022) contends, linguistic competence in one (e.g. Tung) or both languages (e.g. Elly and Tilly) is one of the key elements that influences children’s agency.

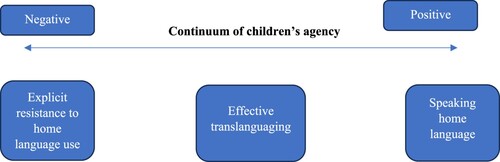

Turning to new findings, our approach to the study of children’s agency in family language policy is based on the argument that agency is a relational, contextualised and dynamic construct which emerges out of the interactions between speakers in their specific situations (e.g. Buhrmann and Di Paolo Citation2017; Edwards and D'Arcy Citation2004; Larsen-Freeman Citation2019). Smith-Christmas’s (Citation2022) theoretical model on agency, which proposes that children’s agency should be considered as a nexus of the generational order, linguistic competence, and the family’s linguistic norms, acknowledges that agency is not only about resisting. Rather it could entail other demonstrations of the relational nature of children’s agency in specific contexts. However, while Smith-Christmas’s (Citation2022) starting point is ‘compliance regimes’ (356), which focus on the dichotic system of identifying whether an act is agentic or not based on the notion of compliance and rejection, our standpoint, following Duff (Citation2012), is that any actions that show the children’s ability to take control, make choices or regulate family language practices as they interact with others can be considered acts of agency. Agency is thus a fluid and dynamic concept that can demonstrate itself in different ways. We visualise agency along a continuum which at the more negative end may include children’s explicit resistance to speaking the home language. The more positive end may entail children speaking the home language or flexibly translanguaging to cater to other interlocutors’ needs ().

Conclusion

This small-scale qualitative study set out to explore the displays of children’s agency in the families’ language practices. In so doing, the family’s linguistic environment emerged as a dynamic space that is subject to the constant interaction and negotiation between the adults and children for their preferred languages to be used in the family domain. We have discussed how children’s displays of agency can be manifested along a continuum ranging from more negative stances to more positive stances in family language practices. In extending Smith-Christmas’s (Citation2022) theoretical model on agency, we suggest that rather than adopting a dichotic system of identifying agency based on the notion of compliance and rejection, children’s agency can manifest along a continuum. Future research studies could continue to explore children’s diverse demonstrations of agency in different immigration contexts, and in particular, explore the factors that contribute to children’s positive demonstrations of agency, which after all is an important goal of family language policy for children’s developing multilingualism.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Pseudonyms were used for all research participants.

2 Tung is the focal child of the study. The larger research project recruited children aged 5–12 as they are at the later fundamental stage of language development (McLaughlin, Citation1984). McLaughlin (Citation1984) stated that children’s language acquisition takes at least 12 years. In the first five years, the foundation for the acquisition of home language phonology, vocabulary, grammar, semantics and pragmatics is formed, while in the next seven years linguistic aspects are reinforced as the complex skills of reading and writing are developed.

3 Elly and Tilly’s cousins who participated in this study include Minh Anh (aged 7), Lan Anh (aged 7), Tuan Anh (aged 10), Toby (aged 5) .

4 In this excerpt, the flow of the conversation may not seem smooth as Tung changes the topic of the conversation quite swiftly. There is some shared information between Ms Tam and Tung. Cookies are Tung’s favourite food, which he seldom eats. Therefore, he expresses his excitement upon knowing Ms Tam is baking them. Furthermore, on the kitchen bench there are ingredients for making cookies and a supermarket receipt. This explains the change in topic.

5 Tung is referring to the docket deals on the back of the supermarket (Coles) receipt.

6 These utterances can be considered Vietnamese because ‘cookies’ can be considered a loan word.

7 Based on interview data with Author 1, not shown.

8 In the explanatory statement, the researchers made clear that the purpose of the research was to explore the families’ habitual language practices and emphasised the importance of for the families to record natural occurring language interactions in their everyday lives. Therefore, even when we see the father, Mr Hung, urging the children to speak Vietnamese as shown in excerpt 3, there is a very rare possibility that Mr Hung did so because the video recording was taking place. However, the way the children reacted to his request demonstrates their agency in family language practices – the focus of our study.

9 Also noted is Tilly’s ability to produce a full utterance in Vietnamese in addition to the common ‘cảm ơn bà nội’ - thank you grandma phrase that all the other children can use.

10 Adapted from Kheirkhah and Cekaite Citation2018, 272.

References

- Ahearn, L. M. 2001. “Language and Agency.” Annual Review of Anthropology 30 (1): 109–137. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.30.1.109.

- Auer, P. 1984. Bilingual Conversation. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Auer, P. 1995. “The Pragmatics of Code-Switching: A Sequential Approach.” In One Speaker, Two Languages: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on Code-Switching, edited by L. Milroy, and P. Muysken, 115–135. England: Cambridge University Press.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2022. Australia's Population by Country of Birth [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/australias-population-country-birth/latest-release.

- Bouchard, J., & Glasgow, G. P. 2019. Agency in language policy and planning (Vol. 17, 1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429455834.

- Bourdieu, P. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Routledge.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Buhrmann, T., and E. Di Paolo. 2017. “The Sense of Agency – a Phenomenological Consequence of Enacting Sensorimotor Schemes.” Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 16 (2): 207–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-015-9446-7.

- Curdt-Christiansen, X. L., and W. Wang. 2018. “Parents as Agents of Multilingual Education: Family Language Planning in China.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 31 (3): 235–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2018.1504394.

- Cruickshank, K. 2019. “Community Language Schools: Bucking the Trends?” In Multilingual Sydney, edited by A. Chik, P. Benson, R. Moloney, and T. Taeschner, 129–140. Routledge.

- D'Angelo, P. 1991. Becoming Australian. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press.

- Danjo, C. 2021. “Making Sense of Family Language Policy: Japanese-English Bilingual Children's Creative and Strategic Translingual Practices.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 292–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1460302.

- Department of Home Affairs. 2022. Country profile – Vietnam. Retrieved from https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-statistics/statistics/country-profiles/profiles/vietnam.

- Döpke, S. 1992. One Parent, One Language: An Interactional Approach. J. Benjamins Pub. Co.

- Duff, P. 2012. “Identity, Agency, and Second Language Acquisition.” In The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition, edited by S. M. Gass, and A. Mackey, 410–426. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Duff, P., and L. Doherty. 2015. “Examining Agency in (Second) Language Socialization Research.” In Theorizing and Analyzing Agency in Second Language Learning: Interdisciplinary Approaches, edited by P. Deters, X. Gao, E. R. Miller, and G. Vitanova, 54–72. Multilingual Matters.

- Edwards, A., and C. D'Arcy. 2004. “Relational Agency and Disposition in Sociocultural Accounts of Learning to Teach.” Educational Review 56 (2): 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/0031910410001693236.

- Eisenchlas, S. A., and A. C. Schalley. 2019. “Reaching Out to Migrant and Refugee Communities to Support Home Language Maintenance.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 22(5): 564–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2017.1281218.

- Felling, S. 2006. Fading Farsi: Language Policy, Ideology, and Shift in the Iranian American Family. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Filipi, A. 2007. “Language as Action.” Australian Review of Applied Linguistics 30 (3): 33.1–33.17. https://doi.org/10.2104/aral0733.

- Filipi, A. 2015. “The Development of Recipient Design in Bilingual Child-Parent Interaction.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 48 (1): 100–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2015.993858.

- Fogle, L. 2012. Second Language Socialization and Learner Agency: Adoptive Family Talk. Multilingual Matters.

- Fogle, L., and K. King. 2013. “Child Agency and Language Policy in Transnational Families.” Issues in Applied Linguistics 19: 1–25. https://doi.org/10.5070/L4190005288.

- Gafaranga, J., and M.-C. Torras. 2002. “Interactional Otherness: Towards a Redefinition of Codeswitching.” The International Journal of Bilingualism: Cross-Disciplinary, Cross-Linguistic Studies of Language Behavior 6 (1): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069020060010101.

- Gyogi, E. 2015. “Children's Agency in Language Choice: A Case Study of two Japanese-English Bilingual Children in London.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 18 (6): 749–764. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2014.956043.

- Jefferson, G. 1985. “Transcription Notation.” In Structures of Social Action, ix, edited by J. Atkinson, and J. Heritage. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511665868.002

- Kheirkhah, M. 2016. From family language practices to family language policies: Children as socializing agents. (Doctoral thesis). Linköping University, Retrieved from http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A912713&dswid=−2222.

- Kheirkhah, M., and A. Cekaite. 2015. “Language Maintenance in a Multilingual Family: Informal Heritage Language Lessons in Parent-Child Interactions.” Multilingua 34 (3): 319–346. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2014-1020.

- Kheirkhah, M., and A. Cekaite. 2018. “Siblings as Language Socialization Agents in Bilingual Families.” International Multilingual Research Journal 12 (4): 255–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2016.1273738.

- Kuczynski, L. 2003. Handbook of Dynamics in Parent-Child Relations. Sage Publications.

- Lanza, E. 1997. Language Mixing in Infant Bilingualism: A Sociolinguistic Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Larsen-Freeman, D. 2019. “On Language Learner Agency: A Complex Dynamic Systems Theory Perspective.” The Modern Language Journal 103 (S1): 61–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12536.

- Li, W. 2018. “Translanguaging as a Practical Theory of Language.” Applied Linguistics 39 (1): 9–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx039.

- McLaughlin, B. 1984. Second-Language Acquisition in Childhood (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Meyer Pitton, L. 2013. “From Language Maintenance to Bilingual Parenting: Negotiating Behavior and Language Choice at the Dinner Table in Binational-Bilingual Families.” Multilingua 32 (4): 507–526. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2013-0025.

- Moustaoui Srhir, A., and D. Poveda. 2022. “Family Language Policy and the Family Sociolinguistic Order in a Neoliberal Context: Emergent Research Issues.” Sociolinguistic Studies 16 (2-3): 179–201. https://doi.org/10.1558/sols.22694.

- Pease-Alvarez, L. 2003. “Transforming Perspectives on Bilingual Language Socialization.” In Language Socialization in Bilingual and Multilingual Societies. Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, edited by R. Bayley, and S. R. Schecter, 9–24. Multilingual Matters, UTP.

- Revis, M. 2019. “A Bourdieusian Perspective on Child Agency in Family Language Policy.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 22 (2): 177–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2016.1239691.

- Rubino, A. 2010. “Multilingualism in Australia.” Australian Review of Applied Linguistics 33 (2): 17.1–17.21. https://doi.org/10.2104/aral1017.

- Rubino, A. 2015. “Performing Identities in Intergenerational Conflict Talk: A Study of a Sicilian-Australian Family.” In Language and Identity Across Modes of Communication, Vol. 6, 125–152, edited by D. N. Djenar, A. Mahboob, and K. Cruickshank. De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781614513599.125

- Said, F., and H. Zhu. 2019. ““No, No Maama! Say ‘Shaatir ya Ouledee Shaatir’!” Children’s Agency in Language use and Socialisation.” International Journal of Bilingualism 23 (3): 771–785. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006916684919.

- Schwartz, M., and A. Verschik. 2013. Successful Family Language Policy: Parents, Children and Educators in Interaction. Springer. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/monash/detail.action?docID=1592505.

- Smith-Christmas, C. 2014. “Being Socialised Into Language Shift: The Impact of Extended Family Members on Family Language Policy.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 35 (5): 511–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2014.882930.

- Smith-Christmas, C. 2017. “Family Language Policy: New Directions.” In Family Language Policies in a Multilingual World: Opportunities, Challenges, and Consequences, edited by J. Macalister, and S. H. Mirvahedi, 13–29. New York: Routledge, an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group.

- Smith-Christmas, C. 2018. “One ‘Cas,’ Two ‘Cas'": Exploring the Affective Dimensions of Family Language Policy.” Multilingua 37 (2): 131–152. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2017-0018.

- Smith-Christmas, C. 2020. “Child Agency and Home Language Maintenance.” In Handbook of Home Language Maintenance and Development: Social and Affective Factors, Vol. 18, 218–235, edited by A. C. Schalley, and S. A. Eisenchlas. Walter de Gruyter GmbH.

- Smith-Christmas, C. 2022. “Using a ‘Family Language Policy’ Lens to Explore the Dynamic and Relational Nature of Child Agency.” Children & Society 36 (3): 354–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12461.

Appendix

Transcription keyFootnote10

° indicates low volume.

<what > indicates slow talk.

CAPS indicate loud volume.

? indicates rising intonation.

underlining denotes emphatic stress.

(0.0) denotes pauses in tenths of a second.

(()) indicate further comments of the transcriber.

: denote a stretched sound

() denotes talk that is unclear or inaudible

{ denotes gesture or embodied action co-occurring with talk (from Filipi Citation2007).