Abstract

The increasing popularity of cursory references to the ‘Global South’ across disciplines and issue areas asks for an in-depth engagement with ‘South’-related terminology. I employ Edward Soja’s Thirdspace as a heuristic for investigating different meanings of the ‘Global South’ with reference to concrete empirical realities in international development. To examine and illustrate what Soja’s trialectics of material, imagined and lived spatialities has to offer, I focus on evidence from Mexico and Turkey. Located somewhere at the boundaries – or the conceptual margins – of the ‘Global South’, Mexico and Turkey sit right where an investigation promises to be particularly fruitful. With a Firstspace perspective, I focus on the mappings of development indices and the material boundaries of the ‘Global South’. With a Secondspace perspective, I analyse the imagined geographies of alliances in multilateral negotiations and the arena of South–South cooperation. With a Thirdspace perspective, I engage with the lifeworlds of public officials and unpack the ways in which the ‘Global South’ appears via individual strategies and practices. Insights from Mexico and Turkey provide evidence for the diversity of meanings attached to the ‘Global South’ and illustrate how Soja’s three-legged heuristic offers a framework for critical engagement with popular taken-for-granted categories.

Introduction

References to the ‘Global South’ have become increasingly prominent in both academic and policy debates. In particular, the practice and study of international development are infused with ‘South’ language, from multilateral development agencies supporting ‘South–South’ cooperation to academics framing their work as research in or on the ‘Global South’.Footnote1 At the same time, scholars have raised questions about ‘the very existence’ of the ‘Global South’Footnote2 and have pointed to the need for a more in-depth engagement with ‘South’-related terminology.Footnote3 Against this backdrop, I suggest using Edward Soja’s Thirdspace heuristic as an analytically grounded way of investigating concrete ‘Global South’ realities in international development.Footnote4 Based on Soja’s trialectics of material, imagined and lived spaces, I examine three perspectives on the ‘Global South’. The first focuses on mappings of material development indices (Firstspace), the second on the imagined geographies of multilateral alliances (Secondspace) and the third on individual lived experiences (Thirdspace). To discuss and illustrate what a Thirdspace approach has to offer, I draw on insights from Mexico and Turkey. Both countries are, in many ways, located somewhere at the boundary between ‘North’ and ‘South’ in the field of international development. As questions of identity and belonging become particularly pronounced in liminal spaces, Mexico and Turkey’s positions allow me to highlight how meanings of the ‘South’ shift from one analytical spatiality to the other, and the extent to which these meanings complement or contradict each other. Overall, I argue that the systematic differentiation between spatial perspectives along the Firstspace, Secondspace and Thirdspace lines provides a helpful device for examining different meanings of the ‘Global South’ as well as their implications for the study and practice of international development. More generally, I suggest that Soja’s Thirdspace heuristic offers a lens for analytical engagement with empirical dynamics to critically engage with popular taken-for-granted categories.

Towards a trialectics of the ‘Global South’

Over the last 15 years, the ‘Global South’ has become a staple among the conceptual terminologies used to make sense of world politics in general and international development in particular.Footnote5 Its surge in popularity, however, has remained somewhat divorced from often elaborate but overall niche discussions about the critical potential of applying the ‘South’ as a lens to the analysis of, and production of knowledge about, global power relations.Footnote6 As a category that ‘order[s] and structur[es] our observations and experiences’,Footnote7 the ‘Global South’ is in the first instance a differentiation device grouping ‘people or things that have similar features’.Footnote8 What exactly these features are, however, is often left unsaid. An increasing number of accounts use the ‘Global South’ as an umbrella term to vaguely refer to the ‘non-West’, ‘Third World’, ‘developing countries’ or the structurally disadvantaged,Footnote9 hinting at a ‘dual spatiality’Footnote10 with the ‘Global North’ as the mostly implicit Other.Footnote11 What is missing from these cursory references is not only a more analytical engagement with the ‘(Global) South’ per se but also a more detailed examination of the extent to which and how references to the ‘South’ acquire meaning in different fields and issue areas. According to Peter Wagner, the ‘Global South’ may have become an integral part of ‘common language in global public debate’, but it tends to be ‘used without further explanation’.Footnote12 In other words, the ‘Global South’ has entered ‘heuristic baggage’Footnote13 – the term is often employed but rarely grounded or problematised.Footnote14

Against this backdrop, I suggest employing Edward Soja’s work on Thirdspace as a conceptual inspiration to recalibrate the analytical discussion of the ‘Global South’. As a proponent of the spatial turn in the social sciences, Soja agrees with other spatial theorists that the study of social realities requires a ‘sensitivity towards the significance of place and space […] in the constitution and conduct of life’.Footnote15 In his exploration of an explicitly spatial analysis, Soja puts forward what he calls a ‘triple dialectic’Footnote16 or ‘trialectics’Footnote17 – a three-dimensional engagement with reality that upsets and goes beyond traditional dualities. With reference to the work of Henri Lefebvre, Soja presents a trialectics of spatiality that unfolds through three perspectives: Firstspace, Secondspace and Thirdspace.Footnote18 A Firstspace perspective focuses on the ‘concrete materiality’ of perceived reality and thus on ‘things that can be empirically mapped’.Footnote19 A Secondspace perspective deals with spatial imageries or ‘ideas about space’.Footnote20 A Thirdspace perspective does not focus on material (First)space or representations of (Second)space as such but on ‘lived spaces of representation’Footnote21 where concrete human experience unfolds. Thirdspace is not only about ‘things in space’ or ‘thoughts about space’ but about ‘fully lived’ space.Footnote22 This ‘Thirding’ as ‘the creation of another mode of thinking’Footnote23 thus points to how material and imagined dimensions of reality together create specific situations in simultaneously ‘real-and-imagined’Footnote24 places that provide the backdrop for and are the product of lived experiences.Footnote25 I suggest that Soja’s trialectics of spatiality offers a helpful heuristic for engaging with the different meanings of the ‘Global South’ as an increasingly popular – and inherently spatial – category. The three interrelated but analytically distinct dimensions of material, imagined and lived spacesFootnote26 point to different types of phenomena which, taken together, problematise mainstream references to and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the ‘Global South’ as a background category in the study of world politics.

In order to discuss the trialectics of the ‘Global South’ with reference to concrete empirical realities I draw on insights from Mexico and Turkey in international development. Both countries are located at the boundaries of different constructs of the ‘Global South’ – or somewhere between ‘North’ and ‘South’ – when it comes to the matrices, alliances and practices that make up the field of international development.Footnote27 Among the members of the Group of 20 (G20), for instance, Mexico and Turkey are the only countries that belong to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and, at the same time, are often referred to as part of a larger group of ‘rising powers’ that challenge the dominance of the ‘Western/Northern World’.Footnote28 As liminal or ‘in-between’ sets of actors and spaces, Mexico and Turkey are thus located somewhere at the threshold between designations such as ‘Northern donors’ and ‘Southern providers’ that have recently dominated international development politics.Footnote29 Following Martin Heidegger’s postulate that ‘the boundary is that from which something begins its presencing’,Footnote30 reflections on and from the positionalities of Mexico and Turkey invite what Fetson Kalua calls ‘thinking on the margins’.Footnote31 The margin is a relational term, implicitly referencing some broader system or category which it is the margin of. While references to marginality usually imply a lack of power and status,Footnote32 this is not an inherent property of the concept. In the first instance, the margin makes simply a reference to the relative position in differentiated social space.Footnote33 As defined in relation to the ‘Global South’, a focus on entities at the margins does thus not necessarily mean to engage with the least powerful or excluded; it rather throws a light at the definitional contours of a given phenomenon – where, whether and how it ‘starts/emerges’ or ‘ends/dissipates’.Footnote34 As sets of actors and spaces that can be said to be both Southern and Northern or neither Southern nor Northern,Footnote35 Mexico and Turkey thus sit right where an analysis of the ‘Global South’ promises to be particularly fruitful.Footnote36 In what follows I show how evidence from Mexico and Turkey – as a view from the margins, as it were – helps to investigate different sets of socially constructed spatialities that currently make up the ‘Global South’ in international development.

A Firstspace perspective: the material spaces of development indices

The term ‘Global South’ has incrementally replaced ‘Third World’ or ‘developing world’ as the frame of choice for academic engagement with concrete materialities in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Across social science disciplines, the ‘Global South’ is often used as a shorthand for states and societies that face low or middling levels of ‘development’.Footnote37 In 1980, the Brandt Commission put forward one of the most emblematic maps of the material realties attached to notions of ‘South’ and ‘North’. The so-called Brandt Line was supposed to highlight the world’s binary division where ‘“North” and “South” are broadly synonymous with “rich” and “poor”, “developed” and “developing”’.Footnote38 World maps intended to provide insights into material development levels usually rely on quantitative measurements, with income-based indices as the most prominent (if contested) tools.Footnote39 These indices arguably epitomise what Soja calls ‘empirically measurable configurations’: they contribute to putting forward a seemingly authoritative definition of the ‘absolute and relative locations of things’.Footnote40 Development indices define what ‘development’ is – such as increasing levels of gross national income (GNI) – and shape the ways in which relative development realities are perceived and acted upon. The category of least developed countries (LDCs), for instance, builds on income classifications, and its introduction by the United Nations (UN) in 1971 ‘officially admitted – arguably for the first time – […] that the South was not monolithic’ and that some countries needed more support than others.Footnote41 Relatedly, the OECD list of recipient countries is based on definitions that rely on income-based indicators; and debates about the shifting boundaries between ‘donors’ and ‘recipients’ focus on questions of graduation and the changing patterns of development assistance allocation to so-called low-income or middle-income countries.Footnote42 While there are many other ways of investigating materialities, the widespread use of ‘quantifiable measures’Footnote43 for analysing the relative positions of countries and regions makes development indices a particularly insightful entrance point for a Firstspace perspective on the ‘Global South’.

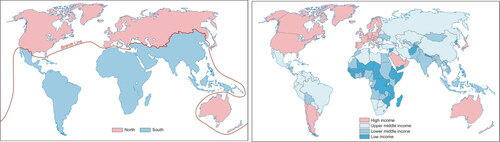

The world map of current income levels – measured by the World Bank as GNI per capita – suggests that there has been some remarkable movement over the last decades in the (Firstspace) South, understood as the three lower segments of the World Bank’s four-legged income categorisation.Footnote44 By and large, income levels have not only increased but also become more diverse; and it is among the countries in the middle-income layers that the most dynamic changes have taken place. A range of countries that were classified as ‘low income’ or ‘lower middle income’ 30 years ago – such as Thailand, Paraguay, Botswana or, in fact, China – are now placed in the ‘upper middle income’ category. Overall, however, (Firstspace) North–South dynamics have not disappeared. Many countries that were categorised as ‘low income’ or ‘high income’ in 1990 are still classified that way today. By and large, high-income countries are still located in North America, Western Europe, East Asia and Oceania,Footnote45 and since 1990, only eight countries outside Europe with more than one million inhabitants have entered the 2017 ‘high income’ category. Seen through the ‘factual scope and “scape” of Firstspace knowledge’,Footnote46 the World Bank’s income typology thus seems to provide strong arguments for the continuing existence of the North-South divide (see ).

Figure 1. Mapping the (Firstspace) South: The 1980 ‘Brandt Line’ (left)Footnote137 and the 2017 World by Income map (right).Footnote138

Income indicators also feed into most other indices aimed at mapping global development realities, such as the Human Development Index (HDI) compiled by the UN Development Programme, which combines income measures with proxies for education and health.Footnote47 Over time, there has been a general upward trend in global HDI levels, and some countries have moved up the HDI’s development ladder – also structured around four categories – with particular speed. Overall, however, countries from the traditional (Firstspace) North dominate the upper echelons of the index, while most countries from Latin America, Southern Asia and particularly Africa are listed in the lower categories. Countries that, over the last decade, have been referred to as ‘rising powers’ are also not under the leading nations in the HDI table: out of 189 countries, Brazil ranks 79th, China 86th and India 130th.Footnote48 By and large, the overall picture major global development indices paint of the relative positions of countries has not changed much over the last few decades. They suggest that ‘the global polarity of “North” and “South”’ – despite major shifts among countries from the (Firstspace) South – ‘has, historically, been of remarkable stability’.Footnote49 The (Firstspace) North–South slope may have flattenedFootnote50 but is still a visible feature of the ‘empirical content of Firstspace’Footnote51 mappings of material development levels.

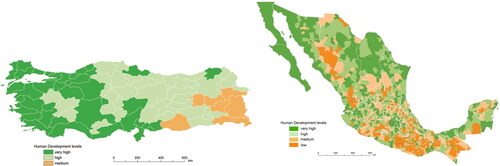

The (Firstspace) South from the margins: Mexico, Turkey and the diversity of sub-national development levels

While Firstspace comparisons based on national aggregates confirm the persistence of North–South patterns, insights from Mexico and Turkey suggest that a more detailed look at index data at different scales points to more complex realities.Footnote52 Both Mexico and Turkey are currently classified as upper middel-income countries with ‘high’ human development levels and thus occupy the second of four categories in both the World Bank income index and the HDI.Footnote53 They join the long list of countries that fall short of the top categories which, since the inception of the indices, have been dominated by countries in North America, Western Europe, East Asia and Oceania. It is this picture of Mexico and Turkey belonging to the ‘leading middle’ in international development indices that gets blurred when engaging with the complexities of scale. A map of provincial HDI levels in Turkey, for instance, shows a ‘highly developed’ west juxtaposed to a ‘not-so-highly developed’ south-east (see ).Footnote54 This regional gap has a long historical trajectory, and while all Turkish provinces score higher today then 30 years ago, the gap between the lowest-ranking and the highest-ranking Turkish provinces is higher today than it was in 1990.Footnote55 In Mexico, the disaggregation of data reveals an even more diverse picture. The HDI map of Mexico’s roughly 2500 municipalities resembles a colourful rag rug.Footnote56 In many Mexican states, ‘low’ municipalities are located right next to ‘very high’ ones. While the highest-ranked Mexican municipality has a higher score than most European countries, Mexico’s lowest-ranked municipalities score at the same level as South Sudan or Niger, the lowest-ranked countries on the 2017 global index. As measured through the HDI, Mexico is thus home to material development realities that are similar to those of both the highest-ranked places of the (Firstspace) North as well as the lowest-ranked places of the (Firstspace) South.

Figure 2. Human Development Index levels of Turkish provinces (left)Footnote139 and Mexican municipalities (right), 2010.Footnote140

These insights offer a glimpse into the complexities behind development indices that take nationally aggregated data as reference to identify global patterns. The subnational diversity of material development realities across continents has been discussed as the ‘South’ in the ‘North’ or the ‘North’ in the ‘South’: highly developed and privileged spaces in the so-called developing world, and materially deprived spaces in so-called industrialised countries.Footnote57 As part of an engagement with the complex patterns of inequality, these insights have prompted some commentators to suggest leaving a state-focused analysis behind and using the ‘Global South’ as a ‘concept-metaphor’Footnote58 to discuss experiences of (material) deprivation that, potentially, take place everywhere.Footnote59 Expanding the meaning of the ‘Global South’ to refer to patterns of dispossession per se is an attempt to respond to the diversity of (development) realities within and across the ‘containers’ of individual countries, a diversity Turkish and particularly Mexican HDI maps provide illustrative examples of. Based on insights from Firstspace descriptions put forward through development indices, the ‘Global South’ as a state-based category seems of only limited use when trying to make sense of the complexities of material development patterns. While global spatialities constructed upon country units have always neglected large parts of social realities, they appear even more problematic against the backdrop of contemporary patterns of material development.Footnote60

A Secondspace perspective: the imagined spaces of multilateral development alliances

While a Firstspace perspective engages with claims about and the social production of materialities, a Secondspace perspective focuses on spatial imaginaries and visions that stem from, as Soja puts it, ‘projections into the empirical world from conceived or imagined geographies’.Footnote61 With regard to the ‘Global South’, I suggest employing this focus on conceived spaces to engage with the imagined geographies of multilateral alliances explicitly put under a ‘Southern’ banner and directed at formulating ideas on how to (re)structure international cooperation. While one could also engage with imageries of the ‘Global South’ in, say, geography literature or transnational solidarity movements,Footnote62 the ‘South’ notion as reflected in and used for inter-governmental alliances and attributions has arguably been the most visible expression of the ‘South’ imaginary in the field of international development. Most academic contributions that discuss the ‘Global South’ with regard to world politics engage with this multilateral (Secondspace) South.Footnote63 They analyse and highlight the strategic dimension of the concept as a tool and identity marker that is employed with the intention of enabling collective action and, eventually, altering power dynamics stemming from ‘deeply unequal and exploitative relationships that developed with peoples of the world subjected varyingly to Euro-Northern American imperialism’.Footnote64

Experiences of colonialism and coloniality as well as different narratives about the identity of societies outside the ‘industrialised world’Footnote65 – narratives which are often conditioned by Firstspace notions of material development levels – provide the backdrop against which the ‘Global South’ as an ‘imagined community’Footnote66 of states acquires meaning in speeches, strategies and alliances that make up multilateral interaction. As Ian Taylor argues, this (Secondspace) South – with roots in the 1955 Bandung conference, the Non-Aligned Movement launched in 1961 and the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) set up in 1964 – ‘has always been an elite political expression’.Footnote67 Building on the Third-Worldism promoted by a range of leaders in post-colonial countries, the ‘South’ stands for a socially constructed imaginary of a transnational community that insists on challenging the dominant voices in world politics and tries to formulate alternatives to the status quo. At UNCTAD, the (Secondspace) South has found expression as an inter-state alliance in the Group of 77 (G77) that initially provided a platform for countries aligned with neither side during the Cold War.Footnote68 Based on the assumption of a ‘commonality of interests that all ex-colonial states possess’,Footnote69 the G77 has been particularly influential in debates on development-related issues at the UN General Assembly. Here, Secondspace imaginaries reminiscent of the Firstspace Brandt Line have become, as Soja puts it, ‘the “real” geography [where] the image or representation com[es] to define and order […] reality’Footnote70 in multilateral fora. For decades, negotiation and voting patterns on the symbolic New International Economic Order resolutions, introduced in 1974 to set up a framework for more equitable forms of international economic exchanges,Footnote71 or on issues related to the more recent Financing for Development agenda where the whereabouts of financial resources for development efforts are debated,Footnote72 have followed the divide between the G77 as the (Secondspace) South and the United States, Western European countries and their allies as the (Secondspace) North.

As an imagined community of players who are said to share a common trajectory and identity connected to experiences of (post)colonial or (post)imperial marginalisation,Footnote73 the (Secondspace) South, however, has been facing serious challenges regarding its cohesiveness as a symbolic reference for meaningful action. During the wave of decolonialisation following the Second World War, the ‘South’ may have ‘momentarily appeared coherent’, even though it was always ‘the more economically advanced developing countries’ that ‘led the way’.Footnote74 At least since the debt crises of the 1980s, however, as Vijay Prashad argues, representatives of the ‘poorer nations’ have struggled to formulate bold political initiatives and garner the active support of the broader ‘Southern’ community against the backdrop of ‘Northern’ hegemony.Footnote75 Particularly over the last 15 years or so, even more pronounced divisions among countries from the (Secondspace) South – what Amitav Acharya has referred to as Poor vs. Power SouthFootnote76 – have come to the fore. While LDCs have tried to raise attention for their needs as a political grouping, middle-income countries have voiced the concern that their interests might not be taken into account in a changing landscape of international development that puts too much emphasis on LDCs.Footnote77 On top of that, the so-called rise or emergence of large ‘Southern powers’ such as China, India and Brazil – also referred to as the ‘locomotives of the South’Footnote78 – has reshaped intra-South dynamics to an extent that shared imaginaries are increasingly difficult to uphold. In light of increasing differentiation processes, the ‘Global South’ as an umbrella imaginary for mobilising action has been under strain. The visions of elites in G20 countries like China and India, for instance, often differ significantly from those of LDC representatives.Footnote79 Beyond UN resolutions immediately related to questions of development, the interests and preferences of the G77’s 134 member states are often too diverse to allow for concerted action. It has become increasingly difficult to formulate what the imaginary of the (Secondspace) South with its historical emphasis on structural economic and political marginalisation actually stands for in today’s multilateral politics.Footnote80

Beyond the ‘North–South theatre’Footnote81 of official negotiations and the diverging interests of G77 member countries, there is another set of venues that have provided an expanding space for references to the (Secondspace) South, albeit in less confrontational terms: the broad arena of so-called ‘South–South’ cooperation for development. Generally traced back to the 1955 Bandung conference where representatives from 25 African and Asian states met to discuss questions of transcontinental solidarity,Footnote82 the notion of South–South cooperation has been a feature of international and transnational relations for decades.Footnote83 Since the turn of the millennium there has been an increased focus on joint efforts of countries that identify as belonging to the symbolic community of the (Secondspace) South to collaborate on development-related processes.Footnote84 Not least, the burgeoning literature on South–South development cooperation and recent discussions about the 2019 UN conference on South–South cooperation give an idea of the growing clout of this less formalised space of the (Secondspace) South.Footnote85 A wide range of bilateral, minilateral, regional and multilateral schemes have endorsed the language of South–South cooperation; the UN Office for South–South Cooperation has become an increasingly visible entity in the UN system;Footnote86 and major players from outside the (Secondspace) South – such as traditional bilateral donors and multilateral bodies – have tried to engage with South–South schemes to ensure they too get a place in what has been presented as one of the most promising spheres of international development.Footnote87

The (Secondspace) South from the margins: Mexico and Turkey’s ambivalent patterns of belonging

For Mexico and Turkey, the conceived spaces of the ‘Global South’ in multilateral development politics provide the backdrop for complex patterns of belonging. Neither Mexico nor Turkey are members of the G77, and both are thus positioned outside of the formal boundaries of the (Secondspace) South. While Mexico decided to leave the G77 when joining the OECD in 1994,Footnote88 Mexican representatives have continued to vote with the G77 on major development-related resolutions at the UN General Assembly. This support for G77 proposals, however, has not been unconditional, as Mexico has tried to also stay close to ‘Northern’ allies.Footnote89 Turkey shares this ambiguous stance towards the (Secondspace) South, albeit in a different way. As a recipient of US assistance following the Second World War, Turkey had always emphasised its ties with the ‘Western/Northern’ reference community, including during its engagement with ‘Southern’ spaces, such as the 1955 Bandung conference.Footnote90 While Turkey never became a member of the G77, Turkish representatives still voted with the G77 on symbolic resolutions until the mid-1980s but then started to abstain or align themselves instead with European countries and others from the (Secondspace) North.

While their links to the G77 as the formal embodiment of the spatial imaginary of the ‘Global South’ in multilateral development politics are tenuous at best, both Mexico and Turkey have expanded their engagement with the less formalised and more inclusive arena of South–South cooperation for development, and they have done so on their own terms. While Turkish institutions have used South–South terminology only scarcely when referring to their development cooperation, Turkey’s engagement with the imaginary of the (Secondspace) South has come to the fore through initiatives where the Turkish government has showcased its leadership role on development-related issues. In 2011, Turkey hosted the UN’s fourth LDC conference in Istanbul, the first time that such a conference took place outside Western Europe. The Turkish government was eager to highlight Turkey’s leadership on support for LDCs as a strong voice from the ‘developing world’, referencing South–South cooperation as a key modality for Turkey’s international engagement.Footnote91 Turkey also co-organised the 2017 UN South–South Development Expo in Antalya and now hosts the recently established UN Technology Bank for LDCs that has been hailed as ‘South–South cooperation in practice’.Footnote92

More explicitly than Turkey, Mexico has integrated references to the (Secondspace) South into its general strategy of engaging with the field of international development. Mexico has been closely connected to institutions such as the UN’s Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean as well as the Ibero-American community, both of which have convened and reported on processes under the explicit umbrella of South–South cooperation since the mid-2000s.Footnote93 Mexico has also championed multilateral processes where the imaginary of the (Secondspace) South has played a crucial role, such as the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation where one of Mexico’s key objectives had been to bring together all relevant players from (Secondspace) South and North.Footnote94 In a similar way, Mexico has tried to bridge divides in processes on development finance at the UN where the G77 has expressed concerns about the commitment of OECD Development Assistance Committee donors – in many ways the antithesis of the (Secondspace) South – to provide development funding.Footnote95

Against the backdrop of their ambivalent relationship with the imaginaries of international development alliances, both Mexico and Turkey have positioned themselves somewhere at the boundaries of or right outside the (Secondspace) South and have tried to use these positions for their strategic purposes. Turkey has done so by showcasing its leadership on specific issues of particular relevance to (parts of) the (Secondspace) South, while Mexico has tried to establish itself as a facilitator to bridge the divide between representatives from (Secondspace) South and North. Although acting outside the G77 in formal UN negotiation processes, both Mexico and Turkey effectively belong to the more inclusive arena of South–South cooperation. In terms of the alliances they support and the terminology they use, the imagined geographies of (Secondspace) South and North – Soja’s ‘projections into the empirical world’Footnote96 – have remained a reference point. For both Mexico and Turkey, the broad imaginary of the ‘Global South’, including its ‘spaces of signification and subject-ness’,Footnote97 still accompanies and conditions their engagement with multilateral development politics.

A Thirdspace perspective: the lived spaces of public officials

Going beyond material constructs (Firstspace) and imaginaries (Secondspace), the heart of Soja’s spatial heuristic focuses on Thirdspace perspectives that engage with ‘the simultaneously real and imagined “other spaces” in which we live, in which our individual biographies are played out, in which social relations develop and change’.Footnote98 In terms of studying the ‘Global South’, this focus on lived spaces brings a largely neglected dimension to the fore: the experiences of those who engage on a day-to-day basis with ‘South’-related questions in international development.Footnote99 Going beyond the dualism of contributions that have argued to take both materialist and ideational dimensions into account when studying the ‘Global South’,Footnote100 Soja’s Thirdspace perspective puts forward an invitation to examine how individuals experience the ‘Global South’ in their everyday lives. While questions related to South–North dynamics potentially affect a wide range of people,Footnote101 those who professionally engage with multilateral development politics are more likely to be confronted with explicit references to the ‘South’. In addition to representatives of multilateral bodies, social movements or advocacy organisations, it is mostly public officials working for foreign ministries or development cooperation agencies who engage with terminology and processes that evoke the ‘Global South’. This is why I focus on their accounts to explore and illustrate what it means to engage with the ‘Global South’ in lifeworlds connected to international development.

A focus on lifeworlds is part of ‘an enlivening of the conception of the world and our knowledge of it’Footnote102 – the engagement with the ‘common sense reality’Footnote103 in which individual experience unfolds. While a lifeworld analysis can engage with various explicit and implicit aspects of people’s lived realities, I focus on the immediate practices and understandings of individuals in their respective contexts: what public officials say about the ‘Global South’; how they make sense of their links with the ‘Global South’; and to what extent the ‘Global South’ – in its Firstspace or Secondspace versions – is present in their lifeworlds. With this focus on lifeworlds, a Thirdspace perspective allows us to gain insights into how material and imagined dimensions of the ‘Global South’ enter ‘intersubjective background understandings’Footnote104 and form reference frameworks that are meaningful for those who engage with international development processes in their everyday lives.Footnote105 The exploration of individual lifeworlds relies on primary data from interviews and observations conducted in 2016 and 2017 with Mexican and Turkish officials based in state ministries, government agencies and diplomatic representation offices.Footnote106 These public officials not only regularly and explicitly engage with ideas about and references to the ‘Global South’ but also contribute to how meanings of ‘North’ and ‘South’ unfold and evolve inside and outside multilateral fora.

The (Thirdspace) South from the margins: Mexican and Turkish lifeworlds

Officials from Mexico and Turkey tend to use the exact same words to describe who they – themselves or their countries – are in international development spaces: ‘a bridge between developed and developing countries’.Footnote107 Expanding on the bridge metaphor, a Turkish official holds that ‘we are one of the very few countries that can understand everyone’Footnote108 and a Mexican official argues that ‘we are facilitators, we bring different sides together’.Footnote109 Being a bridge between the shores of ‘developing’ and ‘developed’ worlds means that questions of identity are complex ones for Mexican and Turkish officials. While official rhetoric in Turkey generally highlights the country’s economic and political strength, particularly when it comes to Turkey’s engagement as a donor,Footnote110 there are instances where references to Turkey’s developing country identity blur this picture. Describing Turkey’s position in multilateral meetings, for instance, one Turkish diplomat states that ‘our positions are similar to the positions of other developing countries’.Footnote111 These ‘other developing countries’ – particularly those in Turkey’s neighbourhood and predominantly Muslim countries in Africa and Asia – are also often referred to with family metaphors, such as ‘our brothers’Footnote112 or ‘sister countries’.Footnote113 Explicit ‘South’ terminology does not play a role in these accounts. For Mexican officials, in turn, Mexico’s developing country identity is repeatedly mentioned when they talk about challenges in terms of (Firstspace) development levels in specific parts of the country but not so much when discussing their positions with regard to dominant (Secondspace) imaginaries in multilateral negotiations. Asked about Mexico’s links with the ‘South’, Mexican officials provide ambiguous answers. One starts off convinced and then retracts: ‘We are part of the South. Well, sort of. Well. I don’t know’.Footnote114 Another one holds: ‘We are very close to the South, that’s for sure. Let’s say that we are the first affiliate of the South’.Footnote115

Overall, the ‘South’ seems to be a weird phenomenon for Mexican and Turkish officials. While it does not play a major role in how they make sense of their identities in international development spaces, it is still present in their lifeworlds – explicitly in language, particularly through references to South–South cooperation, but also implicitly through the role of the G77 as the developing-country bulwark at the UN General Assembly. Talking about what it is like to manoeuvre in UN negotiation spaces as a Turkish diplomat, one summarises his general feelings in one short sentence: ‘We are a little bit alone’.Footnote116 Between representatives from ‘industrialised’ countries – particularly the US, the European Union and their closest allies – on the one hand, and those of the G77 on the other, Turkish diplomats sometimes feel lost in development-related negotiations: ‘The G77 are big enough and don’t need us’.Footnote117 While the G77 as a block seem to clearly define a category of actors as ‘Southern’, the ‘South’ remains evasive. G77 membership is not congruent with the pool of countries that engage in South–South cooperation, and beyond very specific development-related processes at the UN, as a Turkish official holds, ‘[the G77’s] importance is on the decline, clearly. And all these divisions between their members. I don’t envy them, you know’.Footnote118 Mexican officials share this analysis, and one of them summarises her perception by stating that ‘the G77 is basically irrelevant’.Footnote119 Mexican and Turkish officials echo more general assessments across the board that G77 membership is too diverse for effective concerted action beyond a very limited number of development-related negotiations. ‘I’m glad we don’t have to participate in their discussions’, another Mexican official holds. ‘[I]t is really tiring, [there is] no coherence, you don’t understand who’s in charge’.Footnote120

In the lifeworlds of public officials in Mexico and Turkey, the ‘Global South’ can be – with regard to specific issues and processes such as South–South cooperation – an almost ubiquitous phenomenon, but is ‘also always elsewhere’:Footnote121 Mexican and Turkish officials face the tensions of liminal positionalities; they try to smooth the dissonances and hold that their countries are ‘not really’Footnote122 or only ‘sort of’Footnote123 part of the (Firstspace or Secondspace) South. By and large, the ‘real’ South is assumed to exist somewhere else. For Mexican and Turkish officials, it is often difficult to discern – between UN meeting halls and regional technical assistance initiatives – whether the ‘Global South’ actually has an address or clear boundaries. Here, the ‘Global South’ seems to come close to what Soja refers to as a ‘real-and-imagined’ place:Footnote124 it is very much there – explicitly through language in speeches and documents, and implicitly in meetings and alliance structures – but also diffuse and unclear. Through individual engagement with references to the ‘South’ and the entities that are thought to represent it, this real-and-imagined phenomenon is a component of the lifeworlds of public officials. The ‘South’ comes to the fore in how they report on specific events and initiatives, the names they give folders on their desktops, or whom they (have to) reach out to when organising international meetings about development topics where proportionality – regarding the balance between (Secondspace) ‘Southern’ and ‘Northern’ speakers, for instance – plays an important role.Footnote125

Beyond the phenomenological presence of the ‘South’, the reasons behind the use of ‘South’ language often seem unclear to individual representatives. Asked why official Turkish rhetoric makes very little mention of Turkey’s engagement with South–South cooperation, for instance, one official states: ‘To be honest, I don’t know. I can only guess. I don’t know much about South–South cooperation. Political statements are very weird these days’.Footnote126 A desk officer at Turkey’s development agency holds: ‘Well, we don’t really know much about this [South–South cooperation]. It is difficult to follow all the discussions. If they tell me to write South–South in a document I do it. If not, not’.Footnote127 In the lifeworlds of these officials, South–South is a trope that is used when others say so, or because they feel that it is expected to be used. Other officials, however, endorse a more proactive, strategic engagement with South terminology and concepts. In Mexico, one official states with regard to cooperation programmes in Central America: ‘I don’t care if they call it South–South or not; we can call it whatever they want to call it. What matters is that we cooperate’.Footnote128 This is mirrored by a Turkish official who argues that South–South cooperation

is an important jargon for us. Everybody is talking about South–South. [South–South cooperation] is, well, a general tool; [it is] not for concrete projects. […] Our implementing partners are not interested in thinking about South–South cooperation. They just want to get things done.Footnote129

Seen through the accounts of individual officials as, in Soja’s words, ‘an alternative mode of understanding space’, Thirdspace points to how the ‘Global South’ is part of ‘struggles[s] over making both theoretical and practical sense of the world’.Footnote130 The (Thirdspace) South emerges as an overall minor but visible phenomenon in the lived spaces of Mexican and Turkish officials and regularly appears with regard to a limited set of processes. It is made use of in specific venues and with specific partners – particularly when respective audiences (are thought to) expect it.

Interview accounts suggest that in the lifeworlds of Mexican and Turkish officials, the ‘Global South’ has at least two functions. On the one hand, it is a – largely empty – vocabulary that is used because others use it or because one is told to use it, and officials do not engage in more detail with the trajectories and meanings attached to it. On the other hand, the (Thirdspace) South is a label – or a ‘jargon’ – strategically used to position oneself, one’s country or one’s initiatives in spaces where this label (and what others associate it with) has traction. Through these strategies, Mexican and Turkish officials manage to carve out extra manoeuvring spaces – when they play with Mexico’s belonging to both ‘North’ and ‘South’ to invite high-level representatives from all sides of Firstspace/Secondspace divides to attend a workshop in Mexico City, for instance, or when they push for Turkey to enter into closer cooperation with the UN Office for South–South Cooperation to strengthen Turkey’s clout in multilateral coordination processes.

Overall, this (Thirdspace) South is erratically connected to Firstspace and Secondspace notions but also has a life of its own. The material spaces of development levels put Mexico and Turkey – as countries with ‘upper middle-income’ or ‘high human development’ status – at the margins of the (Firstspace) South. The imagined spaces of multilateral political projects – including the G77 at the UN and the expanding arenas of South–South cooperation – put Mexico and Turkey simultaneously outside and inside the (Secondspace) South. In the lived spaces of Thirdspace, individual officials face the ‘Global South’ as a background category that in specific settings and with regard to specific processes comes to the fore. The ‘South’ label is employed – as part of everyday routines or explicit strategies – with specific audiences and in specific moments, which, in Soja’s words, are ‘filled with […] the real and the imagined intertwined’.Footnote131 Even though it remains unclear to most Turkish and Mexican officials to what extent they actually belong to ‘Southern’ spaces, the ‘South’ label is part of their strategies of selfhood: it is used to define, in indirect and tentative terms, who they are and how they manoeuvre their everyday realities.Footnote132

Conclusion

With reference to insights from Mexico and Turkey, this article holds that Soja’s trialectics of spatiality allows us to analytically unpack the phenomenon of the ‘Global South’ in international development by identifying what Firstspace, Secondspace and Thirdspace Souths come to mean when approached from the margins. Taken together, insights from Soja’s three perspectives not only provide evidence for the diversity of meanings attached to the ‘Global South’ but also point to why a differentiated engagement with the category would benefit the study of international development. First, Firstspace insights from Mexico and Turkey suggest that, when it comes to development levels measured through indicators such as the HDI, the ‘Global South’ – if understood as a state-based category – is only of limited use for analysing and explaining patterns of material difference. Given the high and partially rising levels of material disparities in spaces on both sides of the Brandt Line, a more comprehensive analysis of development indicators at the provincial, municipal or household level is likely to produce maps that allow all but clear assignations of (Firstspace) ‘South’ and ‘North’.Footnote133 Second, from a Secondspace perspective the ‘Global South’ has lost salience but remains a visible reference point in multilateral development politics, coming to the fore in the formal settings of UN negotiations as well as the less clear-cut spaces of South–South cooperation. Insights from Mexico and Turkey suggest that the distinction between these two arenas is key for assessing the relevance and the potential boundaries of the ‘Global South’ as part of the imagined geographies of multilateral alliances. In both academic and policy circles, references to South–South cooperation would benefit from a more explicit focus on the complexity of the ‘Southern’ spaces they evoke. This would also contribute to a critical engagement with what the imaginaries of ‘South’ and ‘North’ actually mean in specific platforms and processes that currently (re)shape international development politics, such as the Sustainable Development Goals or China’s global outreach initiatives.Footnote134 Third, I have argued that for Mexican and Turkish officials, the ‘Global South’ is a label, functioning as a background category that is used not only unwittingly as part of routines but also as a component of explicit strategies to manoeuvre international development spaces. The lived experiences of Mexican and Turkish officials as in-between or marginal actors reproduce, leave aside or unsettle established meanings of the (Firstspace or Secondspace) South. While not necessarily part of anti-imperial or decolonial struggles, these individual experiences and understandings are at the core of how the ‘Global South’ comes to mean something to someone. Ultimately, all engagement with the constructed materialities of development indices and the imagined geographies of multilateral alliances is mediated through individual perception and the intersubjective production of meaning. Soja’s Thirdspace perspective can thus be used to combine the study of material and ideational configurations with a focus on the lived experiences of individuals who directly engage with multilateral or transnational politics, or on the lifeworlds of those who write about the ‘Global South’ in think tanks, universities and consultancy offices.Footnote135 More generally, a Thirdspace perspective on lived experiences also lends itself to examining how scholarly engagement contributes to producing the popularity of social categories, and the extent to which these categories are relevant for how people outside academia engage with the world.

What does Soja’s Thirdspace approach leave us with? The ‘Global South’ can be many different things to many different people – an analytical category, a political programme, a label, a home, an identity marker or a term they use because others do so. Soja’s trialectics of spatiality offers one concrete way of investigating which dimensions or aspects of the ‘South’ are being referred to, and thus holds the potential to contribute to meaningful debate about concepts and experienced realities. No matter whether the ‘Global South’ is merely used as a shorthand or explicitly stands at the centre of discussion, the differentiation between the material, imagined and lived dimensions of Firstspace, Secondspace and Thirdspace provides a first step towards a deeper engagement with ‘background ideas’Footnote136 that provide the foundations for (analysing) social processes. A Thirdspace approach is also part of an invitation to engage creatively with conceptual tools in order to develop insights that have the potential to expand – and reshape – the ways in which we study and make sense of the worlds we live in.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Johanna Chovanec for conceptual inspiration as well as to Philip Stickler and James Daniell for map-related support. I would also like to thank Emma Mawdsley, Jacqueline Braveboy-Wagner, Mara Pillinger, the participants of the 2019 conference of the International Association for the Study of Environment, Space and Place (IASESP) and the 2019 Rising Powers Study Group of the Development Studies Association (DSA) as well as two anonymous reviewers for constructive comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sebastian Haug

Sebastian Haug is a graduate research fellow and PhD candidate at the University of Cambridge, where his research focuses on international cooperation and North/South relations. He previously worked with the United Nations in Beijing and Mexico City and has held visiting positions at the College of Mexico, the Istanbul Policy Center and New York University.

Notes

1 Fiddian-Qasmiyeh and Daley, “Introduction,” 11f; Levander and Mignolo, “Introduction: The Global South,” 1; UNDP, Rise of the South.

2 Taylor, “Global South,” 669.

3 See contributions in Fiddian-Qasmiyeh and Daley, Routledge Handbook of South–South Relations; Mawdsley, Fourie, and Nauta, Researching South–South Development Cooperation.

4 Soja, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles.

5 Pagel et al., Use of the Concept “Global South”; Wagner, “Finding One’s Way”; UNDP, Rise of the South; Mawdsley, From Recipients to Donors; Gray and Gills, “South–South Cooperation”; Fiddian-Qasmiyeh and Daley, Routledge Handbook of South–South Relations; see Haug et al., this issue.

Connell, Southern Theory; Braveboy-Wagner, Institutions of the Global South; Comaroff and Comaroff, “Theory from the South”; Prashad, Poorer Nations; Santos, Epistemologies of the South; Mahler, “Global South.”

7 Dingwerth and Pattberg, “Global Governance as a Perspective,” 186.

8 Cambridge Dictionary, “Category.” ‘South’ and ‘Global South’ are used interchangeably here; see Taylor, “Global South,” 542; Wagner, “Finding One’s Way.”

9 For examples see note 14.

10 Wagner, “Finding One’s Way,” 6.

11 Levander and Mignolo, “Introduction: The Global South,” 10.

12 Wagner, “Finding One’s Way,” 1.

13 Kornprobst and Senn, “Introduction: Background Ideas in International Relations,” 275.

14 Woertz, Reconfiguration of the Global South; Singh and Ovadia, “Theory and Practice of Building Developmental States”; Nagelhus Schia, “Cyber Frontier and Digital Pitfalls”; Kshetri, “Will Blockchain Emerge as a Tool”; Donelli and Gonzalez Levaggi, “Becoming Global Actor.”

15 Gregory, “Geographical Imagination,” 282; Soja, “The Spatiality of Social Life.”

16 Soja, “Thirdspace, Postmetropolis and Social Theory,” 113.

17 Soja, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles, 53.

18 Ibid.; Lefebvre, Production of Space.

19 Soja, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles, 10.

20 Ibid., 10.

21 Ibid., 80.

22 Soja, “Thirdspace, Postmetropolis and Social Theory,” 113.

23 Soja, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles, 11.

24 Ibid., 11.

25 Soja’s work on Thirdspace has only triggered a limited engagement with the trialectics of spatiality; for exceptions see Chovanec, “Marlen Haushofers ‘Die Wand’”; Murrani, “Baghdad’s Thirdspace.”

26 Soja, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles, 74, also uses ‘perceived–conceived–lived’ terminology.

27 Esteves and Assunção, “South–South Cooperation”; Haug, “Thirding North/South.”

28 Mystri, “Conditions of Cultural Production,” 13.

29 See Haug, “Let’s Focus on Facilitators”; Haug, “Towards ‘Constructive Engagement’”; Haug, “Thirding North/South.”

30 Heidegger, Poetry, Language, Thought, 154.

31 Kalua, “Homi Bhabha’s Third Space,” 23.

32 Andrucki and Dickinson, “Rethinking Centers and Margins in Geography.” See Soja, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles, 102; hooks, Yearning, 22.

33 Donnelly, “Beyond Hierarchy.”

34 Dainotto, “Does Europe Have a South?”

35 Haug, “Thirding North/South.”

36 Levander and Mignolo, “Introduction: The Global South,” 9.

37 See Pagel et al., Use of the Concept “Global South”; Rigg, Everyday Geography of the Global South.

38 ICIDI, North–South: A Programme for Survival, 31. See Wagner, “Finding One’s Way,” 4.

39 See Anderson, Imagined Communities, 163f.

40 Soja, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles, 74.

41 Taylor, “Global South,” 661.

42 OECD, “DAC List of ODA Recipients.”

43 Andrucki and Dickinson, “Rethinking Centers and Margins in Geography,” 204.

44 For the data set see World Bank, “World by Income and Region.”

45 With the addition of three countries in South America and the Arab peninsula.

46 Soja, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles, 75.

47 UNDP, “Human Development Index.”

48 UNDP, “Human Development Index Trends.”

49 Lessenich, Neben Uns Die Sintflut, 53.

50 Milanovic, Global Inequalities.

51 Soja, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles, 76.

52 Milanovic, Global Inequalities.

53 UNDP, “Human Development Index.”

54 For data and a map see Global Data Lab, “Subnational Human Development Index”; Daniell, Kazai, and Kunz-Plapp, Comparing the Current Impact.

55 Global Data Lab, “Subnational Human Development Index.”

56 UNDP Mexico, Municipal Human Development Index in Mexico.

57 Camacho, “Consumption as a Theme”; Fiddian-Qasmiyeh and Daley, “Introduction,” 4; Levander and Mignolo, “Introduction: The Global South,” 3; see also Milanovic, Global Inequalities.

58 Sparke, “Everywhere But Always Somewhere,” 117.

59 Ibid.; Mahler, “Global South.”

60 Milanovic, Global Inequalities; Lessenich, Neben Uns die Sintflut. See also Permanyer and Smits, “Subnational Human Development Index.”

61 Soja, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles, 79.

62 Mahler, “Global South.”

63 Alden, Morphet, and Viera, South in World Politics; Braveboy-Wagner, Institutions of the Global South; Braveboy-Wagner, Diplomatic Strategies of Nations; Prashad, Poorer Nations; Taylor, “Global South.”

64 Fiddian-Qasmiyeh and Daley, “Introduction,” 22.

65 See Braveboy-Wagner, Diplomatic Strategies of Nations; Rigg, Everyday Geography of the Global South, 187.

66 Anderson, Imagined Communities.

67 Taylor, “Global South,” 656.

68 Toye, “Assessing the G77.”

69 Taylor, “Global South,” 655.

70 Soja, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles, 79.

71 UNBIS, “New International Economic Order.” Also see Taylor, “Global South,” 660.

72 Muchhala, “From New York to Addis Ababa.”

73 Taylor, “Global South.”

74 Ibid., 656 and 660.

75 Ibid., 668f.; Prashad, Poorer Nations.

76 Acharya, “Global International Relations.”

77 Glennie, ‘Middle Income’ Conundrum.

78 Prashad, Poorer Nations, 9.

79 Nayyar, “BRICS, Developing Countries and Global Governance,” 589; see Thakur, “How Representative Are BRICS?”

80 See Toye, “Assessing the G77.”

81 Weiss, “Moving beyond North-South Theatre,” 281.

82 Nesadurai, Bandung and the Political Economy.

83 See South Commission, Challenge to the South.

84 UNDP, Rise of the South; see also Mawdsley, From Recipients to Donors.

85 Mawdsley, Fourie, and Nauta, Researching South–South Development Cooperation; Fiddian-Qasmiyeh and Daley, “Introduction.”

86 UNOSSC, “About UNOSSC.”

87 Abdenur and Fonseca, “North’s Growing Role”; McEwan and Mawdsley, “Trilateral Development Cooperation.”

88 The OECD arguably pushed Mexico to leave the G77; see Covarrubias and Muñoz, Manuel Tello, 92f.

89 For an example see the International Trade and Development resolution.

90 Donelli and Gonzalez Levaggi, “Becoming Global Actor.”

91 MoFA, “Turkey’s Development Cooperation.”

92 UNOSSC, “South–South Cooperation in Practice,” n.p. See also UN News, “UN ‘Tech Bank’ Opens in Turkey.”

93 ECLAC, “Resolution 611(XXX)”; SEGIB, “Informe de la Cooperación en Iberoamérica.”

94 Bracho, Troubled Relationship of the Emerging Powers; Constantine and Shankland, “From Policy Transfer to Mutual Learning?”

95 G77, “Statement.”

96 Soja, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles, 79.

97 Elden, “Production of Space,” 91.

98 Soja, “Thirdspace, Postmetropolis, and Social Theory,” 113; see also Bustin, “Living City.”

99 For exceptions see Mawdsley, Fourie, and Nauta, Researching South–South Development Cooperation.

100 Alden, Morphet, and Viera, South in World Politics, 5.

101 cf. Mohaiemen, Two Meetings and a Funeral.

102 Bleicher, “Leben,” 343.

103 Harrington, “Lifeworld,” 341.

104 Ibid.

105 Soja, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles, 3, 16, 70 and 319, uses the concept of lifeworld only in passing.

106 Interviews and observations took place between 2016 and 2018.

107 Interview (1), Mexico City, February 2017; interview (2), Ankara, May 2017; see Haug, “Thirding North/South.”

108 Interview (3), New York City, November 2016.

109 Interview (4), Mexico City, March 2017.

110 See, for example, TIKA, Turkish Development Assistance Report.

111 Interview (5), Ankara, June 2017.

112 Interview (6), Ankara, October 2016.

113 Interview (7), Ankara, October 2016.

114 Interview (8), Mexico City, January 2017.

115 Interview (9), Mexico City, February 2017.

116 Interview (10), New York City, October 2016.

117 Interview (11), New York City, January 2017.

118 Interview (12), New York City, November 2016.

119 Interview (13), New York City, November 2016.

120 Interview (13), New York City, October 2016.

121 Wagner, “Finding One’s Way,” 3.

122 Interview (10).

123 Interview (8).

124 Soja, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles, 11.

125 Observations in Ankara and Mexico City in 2017.

126 Interview (7).

127 Interview (6).

128 Interview (14), Mexico City, March 2017.

129 Interview (15), Ankara, October 2016.

130 Soja, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles, 104.

131 Ibid., 68.

132 This is where a Thirdspace perspective points to the creation of what Bhabha, Location of Culture, calls Third Spaces.

133 Permanyer and Smits, “Subnational Human Development Index.”

134 See Kohlenberg and Godehardt, this issue.

135 Mawdsley, Fourie, and Nauta, Researching South–South Development Cooperation.

136 Kornprobst and Senn, “Introduction: Background Ideas in International Relations,” 273.

137 Based on ICIDI, North–South: A Programme for Survival, cover.

138 Based on World Bank, “World by Income and Region.” The positionalities of post-Soviet spaces warrant a separate in-depth engagement with the evolving dynamics of North–South divisions.

139 Based on Daniell, Kazai, and Kunz-Plapp, Comparing the Current Impact.

140 Based on UNDP Mexico, Municipal Human Development Index in Mexico, 17.

Bibliography

- Abdenur, Adriana, and Joao Fonseca. “The North’s Growing Role in South–South Cooperation.” Third World Quarterly 34, no. 8 (2013): 1475–1491. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2013.831579.

- Acharya, Amitav. “Global International Relations (IR) and Regional Worlds.” International Studies Quarterly 58, no. 4 (2014): 647–659. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12171.

- Alden, Christopher, Sally Morphet, and Marco Vieira. The South in World Politics. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

- Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities. London: Verso, 2006. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr/90.4.903.

- Andrucki, Max, and Jen Dickinson. “Rethinking Centers and Margins in Geography: Bodies, Life Course, and the Performance of Transnational Space.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 105, no. 1 (2015): 203–218. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2014.962967.

- Bhabha, Homi. The Location of Culture. London: Routledge, 1994.

- Bleicher, Josef. “Leben.” Theory, Culture and Society 23, no. 2–3 (2006): 343–345. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/026327640602300260.

- Bracho, Gerardo. 2017. The Troubled Relationship of the Emerging Powers and the Effective Development Cooperation Agenda. Discussion Paper 25/2017. Bonn: German Development Institute.

- Braveboy-Wagner, Jacqueline. Diplomatic Strategies of Nations in the Global South. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

- Braveboy-Wagner, Jacqueline. Institutions of the Global South. London: Routledge, 2009.

- Bustin, Richard. “The Living City: Thirdspace and the Contemporary Geography Curriculum.” Geography 96, no. 2 (2011): 60–68.

- Camacho, Luis. “Consumption as a Theme in the North–South Dialogue.” Philosophy and Public Policy Quarterly 15, no. 4 (1995): 32–34.

- Cambridge Dictionary. “Category.” (2019), n.p. Accessed August 20, 2019. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/category

- Chovanec, Johanna. “Marlen Haushofers ‘Die Wand’ Als Thirdspace.” Sprachkunst. Beiträge Zur Literaturwissenschaft 1 no. 2016 (2017): 15–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1553/spk45_1s15.

- Comaroff, Jean, and John Comaroff. “Theory from the South: Or, How Euro-America Is Evolving toward Africa.” Anthropological Forum 22, no. 2 (2012): 113–131. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2012.694169.

- Connell, Raewyn. Southern Theory. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2007.

- Constantine, Jennifer, and Alex Shankland. “From Policy Transfer to Mutual Learning?” Novos Estudos – CEBRAP 36, no. 01 (2017): 99–122. doi:https://doi.org/10.25091/S0101-3300201700010005.

- Covarrubias, Ana, and Muñoz Laura. Manuel Tello: Por Sobre Todas Las Cosas México. Mexico City: Instituto Matías Romero, 2007.

- Dainotto, Roberto. “Does Europe Have a South? An Essay on Borders.” The Global South 5, no. 1 (2011): 37–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.2979/globalsouth.5.1.37.

- Daniell, James, Bijan Khazai and Tina Kunz-Plapp. Comparing the Current Impact of the Van Earthquake to Past Earthquakes in Eastern Turkey. CEDIM Report, 2011. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258434207_Comparing_the_current_impact_of_the_Van_Earthquake_to_past_earthquakes_in_Eastern_Turkey

- Dingwerth, Klaus, and Philipp Pattberg. “Global Governance as a Perspective on World Politics.” Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations 12, no. 2 (2006): 185–203. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-01202006.

- Donelli, Federico, and Ariel Gonzalez Levaggi. “Becoming Global Actor: The Turkish Agenda for the Global South.” Rising Powers Quarterly 1, no. 2 (2016): 93–115.

- Donnelly, Jack. “Beyond Hierarchy.” In Hierarchies in World Politics, edited by Ayse Zarakol, 243–265. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- ECLAC [Economic Commission of Latin America and the Caribbean]. “Resolution 611(XXX).” 2014. https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/16099/RES-611-E_en.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

- Elden, Stuart. “Production of Space.” In The Dictionary of Human Geography, edited by Derek Gregory, Ron Johnston, and Geraldine Pratt, 590–592. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

- Esteves, Paulo, and Manaíra Assunção. “South–South Cooperation and the International Development Battlefield: Between the OECD and the UN.” Third World Quarterly 36, no. 10 (2014): 1775–1790. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2014.971591.

- Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, Elena, and Patricia Daley. “Introduction.” In Routledge Handbook of South–South Relations, edited by Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh and Patricia Daley, 1–28. London: Routledge, 2019.

- Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, Elena, and Patricia Daley. Routledge Handbook of South–South Relations. London: Routledge, 2019.

- G77 [Group of 77]. “Statement.” April 21, 2017. http://www.g77.org/statement/getstatement.php?id=170421

- Glennie, Jonathan. The “Middle Income” Conundrum. GPEDC Background Paper, November 2013. http://www.undp.org/content/dam/uspc/docs/SPC%20J%20Glennie%20MIC%20paper.pdf

- Global Data Lab. “Subnational Human Development Index.” Accessed April 15, 2019. https://hdi.globaldatalab.org/areadata/shdi/

- Gray, Kevin, and Barry Gills. “South–South Cooperation and the Rise of the Global South.” Third World Quarterly 37, no. 4 (2016): 557–574. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1128817.

- Gregory, Derek. “Geographical Imagination.” In The Dictionary of Human Geography, edited by Derek Gregory, Ron Johnston, and Geraldine Pratt, 282–285. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

- Harrington, Austin. “Lifeworld.” Theory, Culture and Society 23, no. 2–3 (2006): 341–343. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/026327640602300259.

- Haug, Sebastian. “Let’s Focus on Facilitators: Life-Worlds and Reciprocity in Researching ‘Southern’ Development Cooperation Agencies.” In Researching South–South Development Cooperation, edited by Emma Mawdsley, Elsje Fourie and Wiebe Nauta, 155–170. London: Routledge, 2019.

- Haug, Sebastian. “Thirding North/South: Mexico and Turkey in International Development Politics.” PhD diss., University of Cambridge, forthcoming.

- Haug, Sebastian. “Towards ‘Constructive Engagement’: MIKTA and Global Development.” Rising Powers Quarterly 2, no. 4, (2017): 61–81.

- Heidegger, Martin. Poetry, Language, Thought. New York: Harper and Row, 1971.

- hooks, bell. Yearning. Boston: South End Press, 1990.

- ICIDI [Independent Commission on International Development Issues]. North–South: A Programme for Survival, London: Pan, 1980.

- Kalua, Fetson. “Homi Bhabha's Third Space and African Identity.” Journal of African Cultural Studies 21, no. 1 (2009): 23–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13696810902986417.

- Kornprobst, Markus, and Martin Senn. “Introduction: Background Ideas in International Relations.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 18, no. 2 (2016): 273–281. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148115613663.

- Kshetri, Nir. “Will Blockchain Emerge as a Tool to Break the Poverty Chain in the Global South?” Third World Quarterly 38, no. 8 (2017): 1710–1732. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1298438.

- Lefebvre, Henri. The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell, 1991.

- Lessenich, Stephan. Neben Uns Die Sintflut. München: Pieper, 2018.

- Levander, Caroline, and Walter Mignolo. “Introduction: The Global South and World Dis/Order.” The Global South 5, no. 1 (2011): 1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.2979/globalsouth.5.1.1.

- Mahler, Anne Garland. “Global South.” In Oxford Bibliographies in Literary and Critical Theory, edited by Eugene O'Brien. 2017. https://globalsouthstudies.as.virginia.edu/what-is-global-south

- Mawdsley, Emma. From Recipients to Donors. London: Zed, 2012.

- Mawdsley, Emma, Elsje Fourie, and Wiebe Nauta, eds. Researching South–South Development Cooperation. London: Routledge, 2019.

- McEwan, Cheryl, and Emma Mawdsley. “Trilateral Development Cooperation.” Development and Change 43, no. 6 (2012): 1185–1209. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2012.01805.x.

- Milanovic, Branko. Global Inequalities. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016.

- MoFA [Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Turkey]. “Turkey’s Development Cooperation.” Accessed April 15, 2019. http://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkey_s-development-cooperation.en.mfa

- Mohaiemen, Naeem. Two Meetings and a Funeral. Film, 2017. London: Tate, 2018. https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/turner-prize-2018

- Muchhala, Bhumika. “From New York to Addis Ababa, Financing for Development on Life-Support.” Inter Press Service, July 10, 2015. http://www.ipsnews.net/2015/07/opinion-from-new-york-to-addis-ababa-financing-for-development-on-life-support-part-two/

- Murrani, Sana. “Baghdad’s Thirdspace: Between Liminality, Anti-Structures and Territorial Mappings.” Cultural Dynamics 28, no. 2 (2016): 189–210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0921374016634378.

- Mystri, Jyoti. “Conditions of Cultural Production in Post-Apartheid South Africa.” In Extraordinary Times, IWM Junior Visiting Fellows Conferences 11, no. 8 (2001), 1–20. http://www.postcolonialweb.org/sa/jmistry.pdf

- Nagelhus Schia, Niels. “The Cyber Frontier and Digital Pitfalls in the Global South.” Third World Quarterly 39, no. 5 (2018): 821–837. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1408403.

- Nayyar, Deepak. “BRICS, Developing Countries and Global Governance.” Third World Quarterly 37, no. 4 (2016): 575–591. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1116365.

- Nesadurai, Helen. Bandung and the Political Economy of North–South Relations. Working Paper 95. Singapore: Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, 2005.

- OECD [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development]. “DAC List of ODA Recipients.” 2018. http://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/daclist.htm

- Pagel, Heike, Karen Rane, Fabian Hempel, and Jonas Koehler. The Use of the Concept “Global South” in Social Science and Humanities. Berlin: Humboldt University, 2014.

- Permanyer, Inaki and Jeroen Smits. “The Subnational Human Development Index.” UNDP, 2018. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/subnational-human-development-index-moving-beyond-country-level-averages

- Prashad, Vijay. The Poorer Nations: A Possible History of the Global South. London: Verso, 2012.

- Rigg, Jonathan. An Everyday Geography of the Global South. Abingdon: Routledge, 2007.

- Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. Epistemologies of the South. Justice against Epistemicide. London: Routledge, 2014.

- SEGIB [Secretaria General Iberoamericana]. “Informe de la Cooperación en Iberoamérica.” 2007. https://www.segib.org/?document=informe-de-la-cooperacion-en-iberoamerica

- Singh, Jewellord Nem, and Jesse Salah Ovadia. “The Theory and Practice of Building Developmental States in the Global South.” Third World Quarterly 39, no. 6 (2018): 1033–1055. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2018.1455143.

- Soja, Edward. “The Spatiality of Social Life.” In Social Relations and Spatial Structures, edited by Derek Gregory and John Urry, 90–127. London: Palgrave, 1985.

- Soja, Edward. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996.

- Soja, Edward. “Thirdspace, Postmetropolis, and Social Theory.” Interview by Christian Borch.” Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory 3, no. 1 (2002): 113–120. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1600910X.2002.9672816.

- South Commission. The Challenge to the South. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Sparke, Matthew. “Everywhere but Always Somewhere: Critical Geographies of the Global South.” The Global South 1, no. 1 (2007): 117–126. doi:https://doi.org/10.2979/GSO.2007.1.1.117.

- Taylor, Ian. “The Global South.” In International Organization and Global Governance, edited by Thomas Weiss and Rorden Wilkinson, 279–291. London: Routledge, 2014.

- Thakur, Ramesh. “How Representative Are BRICS?” Third World Quarterly 35, no. 10 (2014): 1791–1808. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2014.971594.

- TIKA [Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency]. 2015. Turkish Development Assistance Report. Ankara: TIKA, 2016.

- Toye, John. “Assessing the G77.” Third World Quarterly 35, no. 10 (2014): 1759–1774. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2014.971589.

- UN News. “UN ‘Tech Bank’ Opens in Turkey.” June 4, 2018. https://news.un.org/en/story/2018/06/1011331

- UNBIS [United Nations Bibliographic Information System]. “New International Economic Order (Search Results).” http://unbisnet.un.org:8080/ipac20/ipac.jsp?session=15G280199Y0V0.284057&menu=search&aspect=power&npp=50&ipp=20&spp=20&profile=voting&ri=&index=.VW&term=new+international+economic+order&matchoptbox=0%7C0&oper=AND&aspect=power&index=.VW&term=&matchoptbox=0%7C0&oper=AND&index=.AD&term=&matchoptbox=0%7C0&oper=AND&index=BIB&term=&matchoptbox=0%7C0&ultype=&uloper=%3D&ullimit=&ultype=&uloper=%3D&ullimit=&sort=&x=9&y=11

- UNDP [United Nations Development Programme]. “Human Development Index.” Accessed January 15, 2019. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-index-hdi

- UNDP [United Nations Development Programme]. “Human Development Index Trends, 1990–2017.” Accessed January 15, 2019. http://hdr.undp.org/en/composite/trends

- UNDP [United Nations Development Programme]. 2013. The Rise of the South. Human Development Report. New York City: UNDP, 2013.

- UNDP [United Nations Development Programme] Mexico. Municipal Human Development Index in Mexico [Índice de Desarrollo Humano Municipal en México]. Mexico City: UNDP Mexico, 2014.

- UNOSSC [United Nations Office for South–South Cooperation]. “About UNOSSC.” Accessed January 15, 2019. https://www.unsouthsouth.org/about/about-unossc/

- UNOSCC [United Nations Office for South–South Cooperation]. “South–South Cooperation in Practice.” Accessed June 8, 2018. https://www.unsouthsouth.org/2018/06/08/south-south-cooperation-in-practice-at-the-new-technology-bank-for-least-developed-countries-ldcs/

- Wagner, Peter.“Finding One’s Way in Global Social Space.” In The Moral Mappings of South and North, edited by Peter Wagner, 1–17. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2017.

- Weiss, Thomas. “Moving beyond North–South Theatre.” Third World Quarterly 30, no. 2 (2009): 271–284. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590802681033.

- Woertz, Eckart, ed. Reconfiguration of the Global South. Africa, Latin America and the “Asian” Century. London: Routledge, 2017.

- World Bank. “The World by Income and Region.” Accessed April 15, 2019. http://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/the-world-by-income-and-region.html