Abstract

This study explores the emergence of the Afro-Indigenous food sovereignty movement in the context of a captured Honduran state and unequal political economy. In contrast with national-level research that has advocated a policy of food security in the context of non-indigenous campesino movements, this work explains how food sovereignty is more appropriate regarding Garifuna Hondurans. In a political economy that has precluded other options, and given the deep cultural relation that Garifuna activists have to land and autonomy, food sovereignty provides a possibility around which Indigenous development can be animated. It encapsulates a local ‘fight’ response to repression as an alternative to northern ‘flight’, often via migrant caravans, that many Garifuna have undertaken. This study shows how food sovereignty, more than being a technical policy set, is a discursive and material node through which dispossessed and especially indigenous populations can enhance decolonial power in the contestation of entrenched hegemonic and institutionalised power in a corrupt, unequal and colonised political economy.

Introduction

Tragic news stories regularly circulate of increasingly numerous migrant caravans marching north from Central America (Torres Citation2020; Burrell and Moodie Citation2019). Although exact numbers are unclear, it has been noted that many of these migrants are Honduran Garifuna, who are fleeing government repression and resource impoverishment caused by land grabs (Brondo Citation2018; Brigida Citation2017). An alternative strategy to fleeing has also been developed by Garifuna – many choose to stay, try and protect their land, and fight continual encroachments and repression. Food sovereignty has become a central element of this fight.

It is not possible to delineate the full richness of food sovereignty research in the confined space of this article. It is important to note, however, that the concept is often evaluated as a technical policy to provide nutrition for communities. In this frame, it is either effective or ineffective in delivering food access or health outcomes (Bernstein Citation2014; Rosset Citation2008; Beuchelt and Virchow Citation2012). Alternatively, food sovereignty has been described as an anthropological object that encapsulates expressions of local politics and identity (Cidro et al. Citation2015; Campbell and Veteto Citation2015). Such work richly describes the way that food sovereignty becomes a locus of attention and meaning as it is integrated in the subjectivities of complex actors. Less commonly, these two stances are combined – producing works that richly describe the meanings, identities, politics and histories that animate food sovereignty movements while evaluating its potential effectiveness given these multiple factors (Boyer Citation2010; McMichael Citation2014).

This study aims to accomplish this last mode of food sovereignty analysis by describing the dialectic, relational and interactive elements that combine to make food sovereignty relevant and important in a particular context. The resulting argument is that food sovereignty is made possible, necessary and imaginable given the political, cultural and economic situation of the indigenous peoples especially. Moreover, it is central to a process of decolonisation which has become necessary for the overall well-being of indigenous families and communities.

This case study provides an example of an analytical method that can be used in multiple locales to richly embed food sovereignty analysis in deep histories, identities and global cultural flows of meanings and materials. Such analysis helps us to move beyond discussions of whether food sovereignty is a good or bad policy, and beyond constructivist descriptions that tend to avoid engaging with policy analysis. Instead it switches the study of food sovereignty towards analyses of when and where communities and groups may find it a meaningful and effective, even necessary, policy and politically animating concept, and when and where it may be less so.

Recent work on food sovereignty movements has analysed their potential to animate meaningful change in differing political, historical, natural and cultural environments (Boyer Citation2010; McMichael Citation2014; Agarwal Citation2014). In Honduras, this mode of analysis has led to contradictory findings. Boyer (Citation2010) has suggested that food sovereignty is not appropriate for the national non-indigenous campesino movement, with whom the concept of food security resonates more strongly. Kerssen (Citation2013), however, notes that food sovereignty has emerged as a powerful animating concept amongst campesinos in the Aguan Valley in Honduras’ north. The different findings of these studies may be due to variance in their temporal situations (one was published three years after the other) and in their scale (one was national, the other regional). Notably, however, food sovereignty studies in the Honduran context have not focussed on indigenous or Afro-Indigenous populations, although numerous studies in other contexts have suggested that indigenous food sovereignty movements differ substantially from their non-indigenous counterparts (Desmarais and Wittman Citation2014; Grey and Patel Citation2015).

Recognising this, this paper will add to previous findings from Kerssen (Citation2013) and Boyer (Citation2010) via an historical, relational and interactive analysis (HRI) (Schiavoni Citation2017) of Garifuna food sovereignty activism in Honduras. As an Afro-Indigenous population who primarily inhabit Honduras’ north coast, the Garifuna experience is one of geographical and racialised historical specificity. This specificity may explain why the idea of food sovereignty has come to matter in Garifuna Honduras despite Boyer’s (Citation2010) contrary findings for other groups in the same country. For researchers of food sovereignty in a broader sense, this suggests that it should not be assumed that food sovereignty is the preferred programme for all people in all geographical locales and political or cultural milieus. Identities and their material, political and cultural histories matter, and these should be integrated into food policy analysis and advocacy of one form of policy over another.

According to Schiavoni (Citation2017), food sovereignty should be understood not as a particular set of policies but as a contextually specific process that unfolds as historically situated groups are dynamically re-shaped through dialectic, relational and interactive connections. More precisely, Schiavoni (Citation2017) explains such movements can be understood via three frames:

First is a historical approach to food sovereignty research, which recognizes the construction of food sovereignty as continuous through time. Food sovereignty efforts are not seen as static, but as shaped by the history from which they arose and as continuing to ‘make history’ as they unfold over time. Second is a relational approach that reflects the open-ended and iterative nature of food sovereignty efforts; that is, that the very meanings of food sovereignty and pursuits toward it are dynamically shaped by competing paradigms and approaches. Third is an interactive approach, which situates food sovereignty construction as neither state-driven nor society-driven alone, but rather as a product of the interaction between and among diverse state and societal actors. (3–4)

Following Schiavoni (Citation2017), the HRI approach allows the concept of food sovereignty to be used in two ways: first, as a theoretical frame that helps to analyse and describe Garifuna food policy; and second, as a finding that describes the historical, political, economic and racial specificity of food sovereignty in the Garifuna context. Thus, this this paper will use the HRI approach to describe how food sovereignty has become a powerful, possibly necessary, animating concept in the specific context of Garifuna Honduras.

Methods and materials

This analysis relies on historical, archival, secondary and tertiary works as well as field research, which my research assistants and I conducted in Garifuna communities from 2013 to 2016. Over that period, we conducted seven focus groups, 80 semi-structured interviews, 994 surveys and two community meetings. This involved a total of 1166 participants between the ages of 18 and 73, 58% of whom were women.

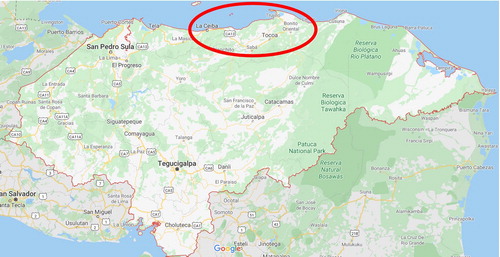

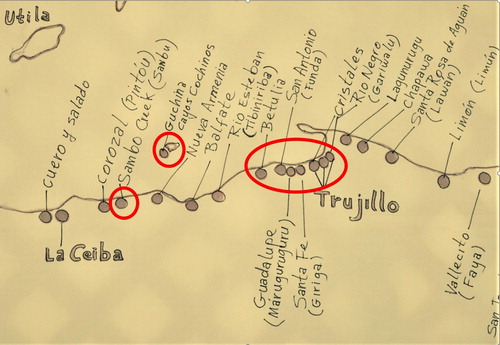

shows Honduras and the main area of interest along the North Coast. shows a closer view of locations of north shore Garifuna settlements as depicted via participatory focus groups by beinggarifuna.com. Where possible, Garifuna place names are written next to Spanish names. The main areas of interest for this study are circled; 793 surveys and 60 interviews were conducted in the Trujillo area – since this is the current epicentre of land displacement and related politics. Interviews and surveys in this area were conducted in the barrio of Cristales (including the adjacent – but not pictured – barrio of San Martin), and with former inhabitants of Rio Negro (which were evicted in 2013 to construct a cruise ship port). Other barrios such as Betulia, Guadalupe, Santa Fe and San Antonio were not subjects of interviews or surveys, but may be referred to in some of the secondary and tertiary materials cited in this paper, since these areas are also subject to the land development pressures related to investment spurred from the port at Trujillo. Further, 201 surveys and 20 interviews were conducted in the Cayos Cochinos area. These were focussed on the two main settlements of Chachahuate and East End (neither of which is specifically labelled on the map). Two interviews were conducted at the offices of the Black Fraternal Organization of Honduras (Organizacion Fraternal Negra Hondureño, OFRANEH) in Sambo Creek.

This fieldwork was part of a tourism impact study that included qualitative and quantitative assessments and measures for food sovereignty, health, well-being and economic development. Because of the unsafe political climate in which this research was conducted, all interviews and surveys were taken anonymously. As a result, most quotations from fieldwork that appear in this document are attributed to fictional names.

A history of marginalisation and independence

The history of Garifuna political identity begins with the wreck of a ship carrying African slaves near the Caribbean Island of St. Vincent in 1675. The Africans intermixed with the indigenous population, and their descendants later became known as the Garifuna. Continued resistance delayed the British colonisation of St. Vincent until 1796, making it the last of the islands of the West Indies to be subjugated. At that time, the island’s darkest inhabitants were deported to the island of Roatan, later to settle mainland Honduras in the early 1800s (Taylor Citation2012; Anderson Citation2009).

The first Garifuna to settle Honduras established the barrios that have come to be known as Cristales and Rio Negro, near the Spanish town of Trujillo. This settlement was expedient to the Spanish who wished to populate the coast. This Garifuna population cultivated rice, manioc, sugarcane, cotton, plantains and squash. Their production exceeded subsistence needs, and they sold their surpluses in Trujillo (Euraque Citation2003). The Garifuna spread out east and west from the Trujillo area, and were granted informal title to much of the north coast (Taylor Citation2012). Beyond farming, Garifuna also became traders, raiders, smugglers, soldiers in Honduras’ civil wars and temporary wage workers in the lumber industry. Then, between the 1890s and 1930s, many became wage workers on inland plantations, as Trujillo became a major port for banana exportation (Gonzalez Citation1988).

Between 1910 and 1930, many Garifuna reverted to fishing/farming lifestyles, perhaps being undercut as labourers by an influx of West Indians. This influx of labour had a negative impact on the earnings of mestizo and Garifuna labourers alike. Labour leaders turned against Black workers specifically in the 1920s, supporting legislation to ban their importation. Blackness became recognised as a threat to the local workforce and to the Indo-Hispanic Mestizo identity that was being positioned as essential to a Honduran nation (Euraque Citation2003; Mollett Citation2006).

Thus, Honduran Garifuna identity is complex. It is simultaneously African and Indigenous. Garifuna settlement was essential to Honduran territorial integrity in much of the north coast, even if the land title was precarious. The dark skin of the Garifuna, however, marked them as outsiders to the Honduran national project of Mestizaje (Loperena Citation2016). Thus, as Mollett (Citation2006, Citation2014) has shown, much of Garifuna cultural politics has involved the assertion of their identity as indigenous Hondurans with tenure rights to much of the north coast, amidst marginalisation due to their blackness which, for many Hondurans, marked them as outsiders and threats to the national culture.

Much of this history was recounted by Garifuna who we interviewed in the Trujillo area. It has four implications for current Garifuna political identity. First, local Garifuna are proud to be members of a traditionally free, unconquered people; second, Garifuna have a strong sense of indigeneity; third, they have a felt right to the territory of Honduras’ north coast; while, fourth, they are subject to systemic marginalisation as they are positioned as outsiders and even invaders in the national consciousness.

Regarding the first implication, Rigoberta Suarez, a local street vendor, recited a claim that was common in our interviews. ‘We are a free people’, she explained, ‘the only Africans in the Americas that were never enslaved’. This sentiment was repeated numerous times in interviews with Garifuna in Cristales, who also emphasised their indigenous status, and the rights attached to that. ‘We are Indigenous’, explained one focus group member; ‘that means we have a right to use our own land according to our customs’.

This is also important for OFRANEH, which is the main Garifuna political organisation in the country. Garifuna activists, often through OFRANEH, are careful to assert the importance of their indigenous culture. For them, this is an essential part of their cultural and political identity. This is vital as there has been a move by the national government to deny the indigenous part of their identity by designating Garifuna as simply ‘Afro-descendant’ in national statistics. This has important implications for land tenure and political rights, as an OFRANEH (Citation2013) memo suggests:

In the decade of the 30s, the Trujillo intellectual Sixto Cacho maintained that the Garifuna people were black skin but indigenous culture. To date we have managed to preserve a good part of the cultural heritage despite the homogenization promoted by the state, through the education system and the mass media …. In recent decades, the cultural scam has been promoted to eradicate the Garífuna identification to replace it with the vague term of Afro-descendant, discarding the cultural patrimony of our ancestors by a simple identification of supposed race, denying this form the genetic hybridism of which we are carriers …. The difference of visions between the Garífuna and those who call themselves ‘Afro-descendants’ is abysmal, the first ones seek territorial autonomy and defense of our communities, the second ones are satisfied with an insertion within a corrupt system and the power handouts of the satraps [foreign-controlled dictators].

As this memo portrays, the cultural hybridity implicit to Garifuna identity is a valued cultural trait and political resource. The identity encapsulates a felt history of independence, and resistance which propels the political activism of a people who have never been slaves and still refuse to become so. This is combined with an understanding of cultural distinctiveness and indigenous cosmovision.

As these claims from OFRANEH suggest, it is important for Garifuna activists and land-defenders that their identity be tied to indigeneity as opposed to only blackness. As Ng’weno (Citation2007) has shown, indigenous populations have been successful in protecting land within neoliberal multicultural Latin American states, and this places Afro-indigenous populations in a predicament. Identification as only black threatens to dislodge Garifuna claims under the Honduran constitution and agreements such as the International Labour Organization’s Convention 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples (ILO 169). This mixes with historical discursive marginalisation of Afro-Hondurans as outsiders who are not a part of the Mestizaje national culture. As a result, the legitimacy of Garifuna territorial claims can be questioned. In a nation with a corrupt judiciary, opaque and overlapping land titling, and economic demands on prime beach property, this ethnic ambiguity can be used to undermine territorial rights.

Historical land dispossession

Our interviews with Garifuna in Trujillo revealed a strong sense of historical right, and cultural connection, to the land of the north coast. ‘This whole coast was ours, should be ours’, said Mario Sanchez, a Garifuna business owner; ‘we settled it hundreds of years ago’. Maria Ortez, a Garifuna vendor, mirrored this claim: ‘Our people survived attempts to enslave us, then we were pushed from St. Vincent and Roatan. The north coast is historically our territory. This was granted to us’. Alfredo Lopez, a Garifuna Activist, articulates the Garifuna relationship with land explicitly:

The Earth is our mother; the sea is our father. When this relationship is broken, we are no longer Garifuna peoples. We make our living from fishing and navigation. We don’t use fertilizers because we don’t want to offend the earth. What do we do? There is a model of working, it’s called Barbecho. We work five years in one area, then we let it ferment and fertilize, and then we occupy another space. This is why our property is collectively owned. Because we need this space, which relates to our functional habitat … so the cultural and ancestral life we are accustomed to can continue. Rights are collective; there is no private property in our way of thinking. (Matamoros 2016)

Anthropological studies have noted the importance of land to Garifuna identity (Hale Citation2011; Mollett Citation2014). They have also documented a complex and culturally specific land tenure system. Garifuna beachfront communities were traditionally built at a distance from agricultural and hunting lands so that food sources were separated from living spaces. This, in combination with the barbecho practice, leaves much Garifuna land to appear unsettled to non-Garifuna eyes (Brondo Citation2010).

All land was tenured collectively, creating vast territories that were governed internally via Garifuna communal councils and tribal leaders. No land was transferable without the approval of local councils. This practice remains to this day. These internal governance and subsistence practices had the historical effect of distinguishing Garifuna territory from the dominant Mestizo society with its European-sourced national governance structure and private tenure traditions (Mollett Citation2014). Common title, cultural identity and territorial distinction were reinforced and reproduced with interconnection to Garifuna language; kinship structures; matrilineal inheritance patterns; subsistence farming, fishing and hunting practices; governance structures; and dance and other cultural practices (Euraque Citation2003).

This sense of Garifuna pride and patrimony was insulted and then re-asserted many times in the modern history of land disputes, especially in the late twentieth century. Neither communal holdings nor Garifuna customary law were recognised by the Honduran state. Furthermore, subsistence practices were not recognised as important when compared to production for international markets. These factors rendered Garifuna territory susceptible to usurpation from the state, which granted large amounts of it to international banana companies in the early twentieth century. This move was met with strong Garifuna opposition. It threatened livelihoods since the Garifuna, especially after the banana boom of the early 1900s, preferred to continue subsistence practices on limited land rather than to join the Mestizo-dominated labour force (Euraque Citation2003). In the 1970s, the Instituto Nacional Agrario (INA), which administered titling nationally, began to recognise the collective right of Garifuna to their lands, but only as permissions for occupation, not ownership. With this legal ambiguity, encroachments continued (Brondo Citation2010; Mollett Citation2014).

Official titling of Garifuna lands began in 1990 with the institutionalisation of neoliberal development policy (Brondo Citation2010). These policies privileged clear land title as the primal component of market-led development. A United Nations Human Settlements Program project at that time mapped and demarcated communal land – limiting it to those tracts that were obviously settled and recently used. Official title meant that Garifuna land could not be sold without community agreement, but this title was applied to a very limited geography. It has been estimated that as much as 80% of Garifuna traditional land was lost by the end of this titling process (MacNeill Citation2017).

Decree 90-90 was enacted in 1990 as part of the process to develop the North coast as a Caribbean tourism destination by allowing foreigners to own situated areas designated ‘urban’. Later, the government instituted constitutional reform to Article 107 that permitted the government to allow foreign ownership by declaring an area to be a tourism priority (Mollett Citation2014). The privilege was formerly limited to Honduran nationals and, significantly, Garifuna. Much Garifuna land is in beachfront areas that are coveted for tourism, and much is also in ‘urban’-designated areas. The barrios of Cristales and Rio Negro, for example, are beachfront areas that are part of the Trujillo urban area. Decree 90-90 and the amendment to Article 107, therefore, would bring traditional Garifuna land holdings to face a new corrosive pressure: foreign capital aimed at tourist industry investment.

This history of land titling and dispossession has had a profound impact on Garifuna political identity. In my interviews in the Trujillo area, local leaders referenced a continual history of ‘land stealing’ perpetrated by ‘colonisers’ wielding economic and political power. This, locals claim, has material consequences. As one Garifuna woman explained, ‘that land in the hands of the foreigners is ours; for our hunting and planting’.

Relation to indigenous rights movements

Although the 1990s saw a continuation of land dispossession and the institution of new decrees which threatened further encroachment, that decade also provided a new resource for the Garifuna resistance: the rise of an international indigenous rights movement. The Honduran ratification of the International Labour Organization’s Convention 169 Concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, in 1995, granted the Garifuna official indigenous status (International Labour Organization (ILO) Citation2017). It contained protections for language and culture while asserting indigenous control over economic development and territorial administration. Territorial rights were not limited to human settlements; ILO 169 also included protections for territories traditionally used for subsistence (ILO 1989).

In 2007, Honduras’ adoption of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples reaffirmed such commitments. These conventions, according to Brondo (Citation2013), affirm that development agendas in Honduras must be pursued only ‘with respect to peoples’ right to healthy food, to water, to forests for foraging …, and ability to continue traditional small-scale agricultural customs’ (183). The adoption of these legal instruments was in part an accomplishment of Garifuna activism, but it would not have been possible if their struggle did not resonate with that of indigenous peoples around the world (Taylor Citation2012).

Adding to the discursive force of indigenous identity, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) recognised Garifuna culture as the first ‘masterpiece of oral and intangible cultural heritage’ in 2001, while noting the cultural centrality of land and subsistence practices (UNESCO Citation2001). Such claims to indigeneity and cultural heritage are integral to Garifuna activism. Key to this is a relationship link between culture, rights and territory.

Local Garifuna that we interviewed in the Trujillo area were all aware that their culture had been designated a ‘masterpiece of cultural heritage’. Often, locals like Dolores Artun asserted that ‘there is no culture like the Garifuna. We have our punta [dance and music], serre and hudut [foods]. We are original in the world’. Quantitatively, we compared cultural salience between Garifuna and Mestizo residents of the Trujillo area via a survey (n = 421). For this measure, we asked participants to list up to three elements of their culture and to indicate on a scale of 1 to 5 how often they practised these elements. The result is a scale from 0 (for an individual who listed no cultural elements and ‘never’ practised them) to 15 (for an individual who mentioned three cultural elements and ‘always’ practised them). Garifuna participants rated 270% higher on average than did Mestizos on this scale, suggesting that culture is much more salient to Garifuna residents of the Trujillo area. OFRANEH makes explicit, repeated claims regarding the salience of the culture on their website, for example by citing the UNESCO designation, or simply appealing to the distinctiveness of Garifuna culture (OFRANEH Citation2020). Even Banana Coast Tours – owned by the same Canadian investor, Randy Jorgensen, who is accused of illegally usurping Garifuna lands – uses this designation in their advertising (Banana Coast Citation2018). This sense of cultural uniqueness, then, is widespread. It is used and understood by foreign tourism operators, Garifuna activists and members of the local Garifuna community alike.

Relation to food sovereignty movements

In October, 2015, OFRANEH was awarded the 7th annual Food Sovereignty Prize from the US Food Sovereignty Alliance. The prize, which emphasises grassroots organisation towards the democratisation of the food system, is a purposeful alternative to the World Food Prize, which is sponsored by many of the world’s largest agribusiness corporations and awards technical achievements in food production within a privatised world food system. The juxtaposition of these two awards serves as an apt corollary for the historical politics of land tenure that continues in Northern Honduras to this day. There, we continue to see a movement for food sovereignty and territorial autonomy emerge as a reaction to land privatisation schemes that have been imposed in the name of development and food security.

Encroachments and the modernisation of the north coast economy may have severely reduced traditional subsistence practices in many areas. In some areas, such as the marine coastal reserve at Cayos Cochinos, subsistence practices are strong; in others they are greatly diminished. In Chachahuate – the main Garifuna settlement on Cayos Cochinos – 47% of those I surveyed in 2016 practised subsistence farming or fishing. Although the loss of land and subsistence there has been severe, some traditional fishing rights have been protected (Brondo Citation2013). In contrast, only 17% claimed to engage in these traditional food production practices in Cristales.

This loss of ability to produce food for local consumption, especially in mainland towns like Trujillo, has been a focal point of Garifuna activism since OFRANEH was formed in 1976. The words of OFRANEH coordinator Miriam Miranda (Citation2015) are illustrative of this:

Our liberation starts because we can plant what we eat. This is food sovereignty. We need to produce to bring autonomy and the sovereignty of our peoples. If we continue to consume [only], it doesn’t matter how much we shout and protest. We need to become producers …. It’s also about recovering and reaffirming our connections to the soil, to our communities, to our land. (USFSA Citation2015)

The Food Sovereignty Prize provided a chance for OFRANEH to link its struggle for land with the idea of food sovereignty in a way that amplified the visibility of the Garifuna movement. Over 190 news agencies, blogs and rights organisations have produced stories of the prize and its relation to Garifuna struggles for land and justice. Many of these contain this excerpt from Miriam Miranda’s acceptance speech for the prize:

Without our lands, we cease to be a people. Our lands and identities are critical to our lives, our waters, our forests, our culture, our global commons, our territories. For us, the struggle for our territories and our commons and our natural resources is of primary importance to preserve ourselves as a people …. There’s more pressure on us every day for our territories, our resources, and our global commons … they’re taking land that we were using to grow beans and rice so they can grow African palm for bio-fuel. The intention is to stop the production of food that humans need so they can produce fuel that cars need. The more food scarcity that exists, the more expensive food will become. Food sovereignty is being threatened everywhere.

Food sovereignty was espoused as a goal by Garifuna leaders in the Trujillo area during our interviews. Speaking of actions being taken by local Garifuna to reclaim traditional lands, one leader stated ‘this land contains our cultural heritage; without our lands we cannot feed ourselves, we cannot be self-sufficient, we lose our traditions’. Garifuna have been at the forefront of recent national anti-government activism (Telesur Citation2014), and this resistance movement has been built around an existing national civil society network that centralised and even incubated the concept of food sovereignty. Boyer (Citation2010) has shown the vital role that the Honduran resistance movement has played in the creation and popularisation of La Via Campesina and the associated politics of food sovereignty. In May of 2016, La Via Campesina affirmed their connection with Garifuna in particular when they issued a statement of solidarity with the ‘Afro-Indigenous’ Hondurans, in which they insist that they are ‘extremely troubled by repeated violations of … human rights’ against the Garifuna and others. In the statement, they denounce continued ‘violations of the human right to life as well as of the right to food sovereignty’ (La Via Campesina Citation2016).

Connections between the Garifuna, La Via Campesina and the global indigenous movement suggest a relational dialectic with other indigenous food sovereignty movements. Such movements are part of continuing anticolonial struggles and share two key relationships: those that intertwine identity with the natural environment, and those that resist impositions of capitalist modernity (Grey and Patel Citation2015). As such, indigenous food sovereignty movements disrupt mainstream, Western development ‘myths’ as ‘groups repeatedly demonstrate … their initiative, creativity, and resistance while maintaining subaltern languages and identities’ (Radcliffe Citation2012, 92). They also emphasise self-determination over the ways in which needs for healthy, culturally relevant foods are met (Desmarais and Wittman Citation2014). This involves calls for legislative and policy reform that creatively attempt to ‘reconcile Indigenous food and cultural values with colonial laws, policies and mainstream economic activities’ (Morrison Citation2011, 101). This, in combination with the ‘outsider’ threat of black subjectivity in Honduras, suggests that Garifuna food sovereignty may engage and contest a different (although overlapping) set of power entanglements than does that of its Mestizo Honduran counterparts, making the concept of ‘sovereignty’ more salient than that of ‘security’.

Interaction with government and transnational power

Most of Honduran political history can be characterised as oligarchy, dictatorship or plutocracy. By 2008, however, the Honduran resistance movement, including OFRANEH and other Garifuna groups, had become powerful enough to influence national politics (MacNeill Citation2017). Consequently, then-President Manuel Zelaya was emboldened to pursue numerous progressive policies. Honduras joined socialist and social democratic national governments in the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA). The minimum wage was raised by 60%, and numerous pro-poor policies were undertaken. A moratorium was placed on the granting of mining concessions until environmental impact assessments were completed. Numerous moves were made to protect the lands of poor campesinos and redistribute lands dubiously controlled by large land-holders back to small-scale farmers (MacNeill Citation2017). The Garifuna were not explicitly mentioned in these initiatives, but drew hope from these conciliatory politics (Brondo Citation2013).

The totality of these moves threatened the interests of national elites as well as Canadian and American investors who were heavily involved in the mining, agricultural, tourism, and manufacturing sectors. These elements conspired and successfully removed Zelaya via military coup in 2009 (MacNeill Citation2017). Successive post-coup governments have since reversed the changes of the Zelaya administration. Poverty rates increased from 58% before the coup to 68% in 2016, and unemployment rates moved from 3% to 7.3% in that same period (INE Citation2017). Social spending was also dramatically curtailed, the minimum wage was reduced to pre-Zelaya levels and the proportion of people employed below that wage increased from 28.8% to 43.6% (Johnson and Lefebre Citation2013).

Corruption and repression have regularly been staples of Honduran politics, but the country entered a period of crisis in this regard after the coup. Politics on all levels have traditionally been clientelist – controlled by an oligarchic group of 10 powerful families. Additionally, national policy has repeatedly been influenced by foreign governments and business interests – particularly those of the United States and Canada (MacNeill Citation2017). This intensified after the coup, when virtually all mining concessions fell to the control of Canadian companies, while at least 34 members of opposition parties were killed by 2010. A strong resistance movement emerged, and this included the direct participation of OFRANEH (Brondo Citation2013). Repression continues, however, and the resistance movement itself is a common target. Notably, north coast Garifuna residents have accused Canadian investor Randy Jorgenson of having Garifuna land rights activist Vidal Leiva shot three times in 2015 (Cuffe Citation2015). More recently, the resistance movement’s de facto leader, Berta Caceres, was assassinated in 2016, followed by two other high-profile members, Lesbia Janeth Urquía and Nelson García (Agren Citation2016).

Violence and corruption have become an understood inevitability in the country. Post-coup Honduras became the most violent place in the world outside a war zone. Political and legal systems are so compromised that even the national government is instituting a plan to carve out multiple localities from the official Honduran judicial and political system in order to offer stability in some areas to international investors (Government of Honduras Citation2017). According to Transparency International (Citation2017), most Hondurans consider their government to be highly corrupt. And it ranks as one of the worst in the world when regarding the abuse of public power for private gain. Transparency of government finances is characterised with the lowest distinction of scant or none, and the country rates extremely low on press freedom and voice and accountability.

Interaction with investors

It is in this national socio-political climate that new encroachment on Garifuna land has occurred in the Trujillo area. Garifuna complaints centre around the Canadian investor Randy Jorgensen, and his companies Life Vision and Banana Coast. There are established links between this investment consortium and the post-coup government, and these links, local Garifuna claim, have assisted in foreign acquisition of Garifuna lands in the Trujillo area (MacNeill Citation2017). These links have facilitated the usurpation of lands belonging to the villages of Cristales and Rio Negro – which was demolished to allow for the construction of Life Vision’s Banana Coast cruise ship port.

Construction began for the cruise ship port in 2011, and it was completed in 2014. In that year, we attempted to find and interview former residents of Rio Negro that still lived in the Trujillo area. Of the 78 former property owners, we found only three – all of whom claimed their living conditions deteriorated after the forced sale of their land. ‘I had running water in my old house’, claimed a former resident, ‘and it was on the beach’. Another explained, ‘we were forced to move. We had only one day to leave and had to take the price that was offered to us or lose our property for nothing’. OFRANEH (Citation2011) considers the acquisition a ‘fraud’ since ‘the majority of these transactions were carried out under pressure’. They also believe that the writ of eminent domain, used by Jorgensen in the eviction, was obtained through bribery and corruption. Jorgensen insists that Rio Negro had been ‘a waterfront eyesore and a habitat for disease’ and that it had been legally removed to make way for ‘a project that would create community wide benefits’ (Personal communication with Randy Jorgensen, January 3, 2014).

Another major land disenfranchisement of the Trujillo-area Garifuna focuses on Jorgensen’s Campa Vista housing project. The land in question is traditional Garifuna hunting and farming territory just south of the community of Cristales. According to the dictates of ILO 169 and Honduran law, community consensus is required for this land to be sold. According to community members and Jorgensen himself, some form of small consultation was carried out, in which the community allegedly agreed to sell 20 hectares to a third-party business associate of Jorgensen (Personal communication with Randy Jorgensen, January 3, 2014). This associate paid the community president at the time, Omar Laredo, US $5000 for the land. The community allegedly never received this money and Laredo left town. Jorgensen then purchased the land for $20,000 from his associate and fenced off 62 hectares of land. Over the next few years he sold the lands, parcel by parcel, to Canadians as vacation home lots, for a total of approximately US $8.5 million, according to the property valuations on their website.

There are similar land disputes between Jorgensen and Garifuna in two other barrios in the Trujillo area – each with similar claims and counter-claims surrounding traditional planting and hunting lands. There are also disputes involving other Canadian land investors (Aqui Abajo Citation2017). Jorgensen is adamant that the land was not being properly used by the Garifuna anyway and that it was legally obtained. Furthermore, consistent with Honduran racial narratives, he rejects the authenticity of Garifuna cultural rights, saying, ‘they are foreigners; they are immigrants to Honduras’ – implying that they are not a true indigenous group (Personal communication with Randy Jorgensen, January 3, 2014).

Serious accusations of intimidation as well as police and state corruption and violence also surround these land disputes. One Garifuna, a self-proclaimed ‘land defender’, claims she was arrested and tortured by Honduran police and military for opposing a Canadian tourism project (Aqui Abajo Citation2017). Others claim to have been shot and/or intimidated by Jorgensen’s ‘hitman’ (Rights Action Citation2015). The barrios of Cristales and Rio Negro have pushed to have criminal charges brought against Jorgensen for illegal possession of Garifuna lands, but these charges were granted a five-year stay in a Trujillo court (Rights Action Citation2015). Absolute truth and legality are difficult to discern in these opaque relationships. However, it is clear that many local Garifuna operate under the assumption that the police, local government and Honduran state are corrupt and operating in the interest of foreign investors and local elites. Appeals to justice, this implies, cannot be successfully made through official state channels.

This local land usurpation in the interest of tourism, claim local Garifuna, ‘hurt our ability to feed ourselves’, as one local woman put it. But this is just another in a long history of threats to local food sovereignty. ‘There are not fish in the Trujillo Bay’, a Cristales resident told me during a focus group; ‘foreigners now own our farming lands along the water, and our lands in the mountains’. ‘One way that we could improve our lives is through producing our own food as we once did, but how can we do this?’ added another focus-group member.

The lack of fish in the bay, local Garifuna claim, is somewhat the result of local Garifuna overfishing and population growth, but was also caused by international industrial fisheries that operate just off the coast. The lack of farmland stems from population increase, land use by tourism operators and land speculation from those who expect tourism to increase local real-estate values. The latter situation often involves absentee foreign landlords. Many Trujillo-area Garifuna have been actively occupying related lands, only to find themselves in conflict with the military, who have established a local presence with the explicit purpose of protecting foreign-owned land from Garifuna squatters. Given such resource restrictions, it is not surprising that few Trujillo Garifuna practise subsistence agriculture or fishing.

Interaction with development

Despite the land grabs, large-scale foreign investment in local tourism inspired hope for socio-economic improvement in many of the local Garifuna. Many participants in our interviews and focus groups expressed the sentiment that ‘with tourism, money will come’, and believed/wished that this would produce income for many. These hopes have largely been unfulfilled, however. The un-kept promises of neoliberal development have, consequently, fuelled increased Garifuna activism in the interest of territorial autonomy and food sovereignty.

Despite being sceptical about the legality and fairness of land acquisition, many Trujillo-area Garifuna we interviewed were strongly supportive of the tourism projects that were to result. When asked about Jorgensen’s cruise ship port before it opened in 2014, 57% of the 171 Cristales residents we surveyed expected their lives to improve economically because of the development.

A cursory look would give the impression that some benefits were achieved via foreign-led tourism development. Garifuna culture is central in advertising to tourists and some local Garifuna residents of Cristales participate in the tourism industry. These individuals are highly visible when cruise ships arrive, dancing traditional Punta dances as passengers disembark, or serving drinks in beachside bars. Ten percent of Cristales residents we surveyed claimed to gain some income from tourism in 2016, up from 6.5% in 2014.

Closer investigation of survey results, however, reveals that local Garifuna receive very limited financial benefit from these activities. Only 6% of Cristales residents claim to have full-time occupations related to tourism, and these are all servers in bars or restaurants and are paid only in tips. The average yearly income of these workers is US $1020 – about half of the Honduras average income of US $2495 per year and much less than the regional average of US $1924. Approximately 10% of Cristales residents claim to have some part time earnings from tourism. Usually these earnings are from tips only and account for less than 10% of the participants’ total yearly earnings. These individuals earn only US $1550 on average per year. Tourism-related earnings for this group average only US $263 annually.

When overall tourism impact on the local economy is considered, any impression of local benefit disappears. The few informal tourism jobs outlined above were generated by an unprecedented influx of about 60,000 tourists spending an estimated US $10 million between 2014 and 2016. This represents a near doubling of the local economy. According to estimates from the World Trade and Tourism Commission (WTTC 2017), we would expect 8541 local jobs to have been produced from such an economic injection.

Contrary to such projections, a quantitative impact study we published revealed that the cruise ship port in Trujillo brought no positive economic impacts to local Garifuna communities (MacNeill and Wozniak Citation2018). The study found that the ability of Garifuna to provide for their necessities, including food, decreased. Furthermore, there was no detectable increase in employment. There were no improvements in sewage or garbage services despite the extra burden imposed by cruise ship tourists on local infrastructure. Local Garifuna also believed that corruption of local business, police and politicians had increased. Compared to 57% of the population who believed that tourism would deliver economic benefits in 2014, by 2016 only 11% believed they had benefitted, directly or indirectly, from tourism industry development.

Continued violence, corruption, dispossession and marginalisation from the benefits of economic development have, not surprisingly, led to both fight and flight responses in the Garifuna community. Jose Francisco Avila, of the Garifuna Coalition USA in New York, has noted a new wave of Garifuna illegal immigration to the United States via migrant caravans and other measures (Brigida Citation2017). Zulma Valencia de Suazo, of the Organization of Ethnic Community Development – a Honduran Garifuna rights and development group – blames this emigration partially on tourism-related evictions on the North Coast. ‘We have always been discriminated against and made invisible in the development process of Honduras’, Suazo claims, and ‘more mothers with children and youth [are now migrating] because of the lack of opportunities’ (quoted in Brigida Citation2017).

Migration is not a viable option for most Garifuna and, as a result, many have chosen to stay and fight for both land and the ability to pursue development on their terms. Garifuna leader Madelin David Fernandez, for example, was arrested and allegedly tortured in November 2016. Fernandez had refused to leave land that had been claimed by another Canadian tourism developer in the Trujillo area. Only with a legal and media intervention from OFRANEH was she freed. Her message to other Garifuna:

Let us unite … with union there is force, we as Garifuna, we can, we have capabilities and we have all the courage to continue in this struggle. This is my message, especially for the women, for the youth. Continue informing yourself and continue trusting and believing in [Garifuna] leaders, and we have to believe in our leaders. Strength is in unity. (quoted in Aqui Abajo Citation2017)

Another Garifuna leader, Julian Eramos Castillo, Vice President of the communal authority of the village of Triunfo de la Cruz, agrees: ‘After the Coup we resisted, and we will continue in resistance… we, Garifuna people, fight to the death. We will continue defending our ancestral territory to ensure our children never lose our culture, language and connection to land’ (quoted in Aqui Abajo 2017).

For OFRANEH and associated Garifuna leaders, the Honduran government is one of the main agents facilitating the appropriation of traditional lands. Political organisation is therefore required to protect Garifuna territory from a corrupt Honduran judicial and political system that has been captured by Honduran elites and foreign business interests. As Madelin Fernandez explains, ‘we need to be united, because the plan of this government is very clear, they want to disappear us, take possession of our lands, our beaches and mountains, and sell them to the highest bidder’. She continues: ‘but they will not make it, … we will continue to recuperate our lands and territories’ (quoted in Soto Citation2016). As a local leader in Cristales explained to me in a 2016 interview, ‘only when we are clearly in control of our own land can we provide food and a better life for our families’; she continued, ‘with our land, we can create development that benefits us, not just foreigners’.

Discussion and conclusion

The purpose of this paper has been to describe the ways in which food sovereignty has come to be both necessary and conceivable to Garifuna of Honduras’ north coast. This was done via an HRI analysis as advocated by Schiavoni (2017) for the study of food sovereignty politics. This analysis revealed that current-day Garifuna political identities are products of a complex history of independence, marginalisation and dispossession. This history has been experienced in relation to slave traders, colonial masters, neoliberal land reformers, oligarchs and foreign business interests in a continuing anticolonial struggle.

All of this historical interrelation has colluded to make the concept of food sovereignty imaginable as a possible future for Garifuna activists. The idea plays to the Garifuna sense of independence. As with other indigenous groups, the territorial autonomy that is implied by food sovereignty speaks to the sensibilities of a people who have repeatedly had their lands and livelihoods assaulted by foreign actors in collusion with national governments in re-occurring extensions of colonialism.

Since food sovereignty and indigenous rights movements are intertwined, Garifuna also see in food sovereignty the possibility of asserting their felt sense of uniqueness. In the subjectivity of the Garifuna activist, traditional knowledge relating to food governance and sustainable production practices is seen as a viable alternative to a commodifying, corrupting and environmentally damaging system of capitalist industrial food production. Global indigenous rights and food sovereignty movements help imbue confidence in the Garifuna that their indigenous knowledge and governance practices are viable catalysts for development.

In contrast, a state that is viewed as corrupt and discriminatory represents an adversary, not a partner in development. External investors appear as predatory land invaders who promise development with one hand while precluding its possibility with the other. The type of autonomy implied by food sovereignty is therefore necessary in the eyes of Garifuna activists, since it may be just the governance tool required to keep the predatory Honduran government and global capitalist system from encroaching on local attempts to create livelihoods.

Food sovereignty therefore fits well with a Garifuna political identity that pushes simultaneously against colonialism and towards indigenous development. Within Garifuna communities, continued marginalisation is accompanied by imaginaries of development and improvement of lives and livelihoods. As mainstream development imaginaries fade with the realisation of continued poverty and the embedded corruption of the Honduran state, Garifuna communities have searched successfully for allies within the global indigenous rights and food sovereignty movements. Not only has this facilitated their own activism, but the Garifuna have simultaneously helped to build these international movements.

Thus, in order to escape the marginalising effects of the Honduran political economy, Garifuna activists have come to feel that it is both possible and necessary to assert claims of autonomy. Food sovereignty resonates with this need. Its dictums contrast vividly with continued privatisation, which places land-use decisions in the hands of economic elites and global investors. The concept of food sovereignty is a power-imbued term through which Garifuna activists draw attention to the raw inequalities in the local, national and international political economies within a continuing anticolonial struggle. While doing this, they assert a place-based identity and the possibility of indigenous alternatives to neoliberal development. In this way, food sovereignty encapsulates a local decolonial ‘fight’ response to repression as an alternative to the large-scale northern ‘flight’, via migrant caravans to Mexico and the United States, that many Garifuna have undertaken.

Beyond its applicability to indigenous food sovereignty movements in Central America, this study helps us to think about, and theorise, the idea of food sovereignty more generally. The concept is used by many indigenous movements throughout the world. Farmers and mixed national movements also use the concept, albeit possibly less commonly (Mihesuah, Hoover, and LaDuke Citation2019; Wittman, Desmarais, and Wiebe Citation2010). The important lesson here is that food sovereignty is less a technical policy apparatus and more a malleable political and discursive concept. The concept imbues political movements with power because of its position in discursive networks – especially those relating to ideas such as sustainability and indigenous rights.

Perhaps more so than the concept of food security, food sovereignty can be bent to the needs of local movements. Simply put, what matters in food sovereignty are the powerful discursive and material allies that the concept can conjure. The concept is about material deprivation and environmental loss. In the face of these deprivations and losses, food sovereignty acts as a political movement above all else. Like all subaltern movements, it seeks to coordinate various discursive and material resources in the contestation of power. Such alliances seem to make increasing sense in the case of indigenous peoples, especially those who exist within enduring colonial and/or corrupt states.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research was approved by a Research Ethics Board review at Ontario Tech University. All participants gave proper consent to be included in the research.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Peter Andrée and Charles Levcoe for comments on early versions of this paper, and to Irena Knezevic and FLEdGE (Food: Locally Embedded, Globally Engaged) for providing a forum for engagement with these issues. A special thanks to my amazing Canadian and Honduran field team who worked on this project.

Disclosure statement

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Timothy MacNeill

Timothy MacNeill is a Professor in Political Science and the Director of Sustainability Studies at Ontario Tech University in Ontario, Canada. His work examines cultural, economic and political interactions related to international development and environmental sustainability. He is the author of two books on to this topic: Indigenous Cultures and Sustainable Development in Latin America, and Life in a Cultural Economy: Music, Markets, and Development. He has conducted collaborative research with indigenous communities in Guatemala, Ecuador, Honduras and Canada. This collaborative work has focused on the economic, cultural, political and environmental aspects of decolonisation and indigenous alternatives to Western development. It also addresses impacts of mainstream development projects on indigenous peoples. His widely cited recent paper entitled ‘The Economic, Social, and Environmental Impacts of Cruise Tourism’ actualised an important methodological advancement that combines ethnography with large-scale natural experiments. He is currently undertaking new fieldwork in Honduras and Canada that similarly combines large-scale quantitative/experimental methods with ethnographic insights. In Honduras, this involves a study of the way in which Zonas de Empleo y Desarrollo Económico (ZEDEs) impact local indigenous and campesino populations. In Canada, he is working collaboratively with Anishinabek communities to decolonise both social services and labour markets.

References

- Agarwal, Bina. 2014. “Food sovereignty, food security and democratic choice: critical contradictions, difficult conciliations.” Journal of Peasant Studies 41 (6): 1247–1268. doi:10.1080/03066150.2013.876996.

- Agren, David. 2016. “Honduras Confirms the Murder of Another Member of Berta Caceres’ Activist Group.” The Guardian, July 7. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jul/07/honduras-murder-lesbia-janeth-urquia-berta-caceres.

- Anderson, Mark. 2009. Black and Indigenous: Garifuna Activism and Consumer Culture in Honduras. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Aqui Abajo. 2017. “One Land Defender’s Story of Repression, Criminalization and Arrest: Young Garifuna woman arrested for reclaiming ancestral land.” February. http://www.aquiabajo.com/blog/2017/2/8/one-land-defenders-story-of-repression-criminalization-and-arrest-young-garifuna-woman-arrested-for-reclaiming-ancestral-land.

- Banana Coast. 2018. “Welcome to Trujillo - The Banana Coast.” Banana Coast Tours, January. http://bananacoasttour.com/trujillo/.

- Beuchelt, T. D., and D. Virchow. 2012. “Food Sovereignty or the Human Right to Adequate Food: which Concept Serves Better as International Development Policy for Global Hunger and Poverty Reduction?” Agriculture and Human Values 29 (2): 259–273.

- Bernstein, H. 2014. “Food Sovereignty via the ‘Peasant Way’: A Sceptical View. Journal of Peasant Studies 6: 1031–1063. doi:10.1007/s10460-012-9355-0.

- Boyer, Jefferson. 2010. “Food security, food sovereignty, and local challenges for transnational Agrarian Movements: the Honduras Case.” Journal of Peasant Studies 37 (2): 319–351. doi:10.1080/03066151003594997.

- Brigida, Ana Catherine. 2017, “Garifuna Flee Discrimination and Land Grabs in Record Numbers.” Telesur, February 23. https://www.telesurtv.net/english/news/Garifuna-Flee-Discrimination-and-Land-Grabs-in-Record-Numbers-20170223-0002.html.

- Brondo, K. 2018. “A Dot on a Map: Cartographies of Erasure in Garifuna Territory.” PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review 41 (2): 185–200. doi:10.1111/plar.12272.

- Brondo, Keri. 2010. “When Mestizo Become (like) Indio… or is it Garifuna? Negotiating Indigeneity and Making Place on Honduras’ North Coast.” Journal of Latin American and Carribbean Anthropology 15 (1): 171–194.

- Brondo, Keri. 2013. Land Grab: Neoliberalism, Gender, and Garifuna Resistance in Honduras. Phoenix: University of Arizona Press.

- Burrell, J., and E. Moodie. 2019. “Beyond the Migrant Caravan: Ethnographic Updates from Central America.” Society for Cultural Anthropology, January 29. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/series/behind-the-migrant-caravan-ethnographic-updates-from-central-america.

- Campbell, B. C., and J. R. Veteto. 2015. “Free Seeds and Food Sovereignty: Anthropology and Grassroots Agrobiodiversity Conservation Strategies in the US South.” Journal of Political Ecology 22 (1): 445–465. doi:10.2458/v22i1.21118.

- Cidro, J., B. Adekunle, E. Peters, and T. Martens. 2015. “Beyond Food Security: Understanding Access to Cultural Food for Urban Indigenous People in Winnipeg as Indigenous Food Sovereignty.” Canadian Journal of Urban Research 24 (1): 24–43.

- Cuffe, Sandra. 2015. “The Struggle Continues: Garifuna Land Defender Shot in Honduras.” Truthout, December 12. http://www.truth-out.org/news/item/33976-the-struggle-continues-garifuna-land-defender-shot-in-honduras.

- Desmarais, A. A., and H. Wittman. 2014. “Farmers, Foodies and First Nations: Getting to Food Sovereignty in Canada.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 41 (6): 1153–1173. doi:10.1080/03066150.2013.876623.

- Euraque, Dario. 2003. “The Threat of Blackness to the Nation: Race and Ethnicity in the Banana Economy.” In Banana Wars, by Steve Stiffler and Mark Moberg, 229–252. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Gonzalez, N. 1988. “The Threat of Blackness to the Mestizo Nation: Race and Ethnicity in the Homduran Banana Economy.” In Banana Wars: Power, Production and History in the Americas, by S. Striffler, M. Moberg, G. Joseph, and E. Rosenberg, 229–249. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Government of Honduras. 2017. “Zonas de Employo y Desarollo Economico.” Zonas de Employo y Desarollo Economico. http://zede.gob.hn/.

- Grey, S., and R. Patel. 2015. “Food Sovereignty as Decolonization: Some Contributions from Indigenous Movements to Food System and Development Politics.” Agriculture and Human Values 32 (3): 431–444. doi:10.1007/s10460-014-9548-9.

- Hale, C. 2011. “Resistencia para que?” Economy and Society 40 (2): 184–210. doi:10.1080/03085147.2011.548947.

- International Labour Organization (ILO). 1989. “ILO 169: Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention.” http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C169.

- International Labour Organization (ILO). 2017. “Ratifications for Honduras.” August 16. http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:11200:0::NO:11200:P11200_COUNTRY_ID:102675.

- INE. 2017. “Instituto Nacional Estadistica.” www.ine.gob.hn.

- Johnson, J., and S. Lefebre. 2013. Honduras Since the Coup: Economic and Social Outcomes. Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research.

- Kerssen, T. M. 2013. Grabbing Power: The New Struggles for Land, Food and Democracy in Northern Honduras. Oakland: Food First Books.

- La Via Campesina. 2016. “Honduras: Statement from the CLOC-La Via Campesina Central America in Reaction to the Increasing Criminalisation of the Peasant Movement.” La Via Campesina, May 18. https://viacampesina.org/en/honduras-statement-from-the-cloc-la-via-campesina-central-america-in-reaction-to-the-increasing-criminalisation-of-the-peasant-movement/.

- Loperena, C. 2016. “Conservation by racialized dispossession: The making of an eco-destintion on Honduras’ North Coast.” Geofurum 69: 184–193. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.07.004.

- MacNeill, Timothy. 2017. “Development as Imperialism: Power and the Perpetuation of Poverting in Afro-Indigenous Central America.” Humanity & Society 41 (2): 1–31.

- MacNeill, T., & Wozniak, D. (2018). “The Economic, Social, and Environmental Impacts of Cruise Tourism.” Tourism Management, 66, 387–404.

- McMichael, P. 2014. “Historicizing Food Sovereignty.”Journal of Peasant Studies 41 (6): 933–957.

- Mihesuah, D., E. Hoover, and W. LaDuke. 2019. Indigenous Food Sovereignty in the United States: Restoring Cultural Knowledge, Protecting Environments, and Regaining Health, Vol. 18. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Miranda, Miriam. 2015. “Defending Afro-Indigenous Land: Black Fraternal Organization of Honduras Wins Food Sovereignty Prize.” October 7. http://upsidedownworld.org/archives/honduras/defending-afro-indigenous-land-black-fraternal-organization-of-honduras-wins-food-sovereignty-prize/.

- Mollett, S. 2006. “Race and Natural Resource Conflicts in Honduras: The Miskito and Garifuna Struggle forLasa Pulan.” Latin American Research Review 41 (1): 76–101. doi:10.1353/lar.2006.0012.

- Mollett, S. 2014. “A Modern Paradise: Garifuna Land, Labor, and Displacement-in-Place.” Latin American Perspectives 41 (6): 27–45. doi:10.1177/0094582X13518756.

- Morrison, D. 2011. “Indigenous Food Sovereignty: A Model for Social Learning.” In Food Sovereignty in Canada: Creating Just and Sustainable Food Systems, edited by H. Wittman, A. A. Desmarais, and N. Wiebe, 97–113. Halifax: Fernwood.

- Ng’weno, B. 2007. “Afro-Colombians, Indigeneity and the Multicultural Colombian State.” Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 12 (2): 414–440.

- Organizacion Fraternal Negra Hondureño (OFRANEH). 2013. “Afrodescendientes o Garifunas?” September 16. https://ofraneh.wordpress.com/2013/09/18/afrodescendientes-o-garifunas-raza-o-cultura/.

- Organizacion Fraternal Negra Hondureño (OFRANEH). 2011. “Garifuna Communities of Trujillo Take Legal Action against Canadian Porn King.” http://friendshipamericas.org/ofraneh-garifuna-communities-trujillo-take-legal-action-against-canadian-porn-king.

- Organizacion Fraternal Negra Hondureño (OFRANEH). 2020. “Inicio.” http://ofraneh.org/ofraneh/index.html.

- Radcliffe, S. A. 2012. “Dismantling Gaps an Myths: How Indigenous Political Actors Broke the Mould of Socioeconomic Development.” Brown Journal of World Affairs 18 (2): 89–102.

- Rights Action. 2015. “Canadian Porn King on Trial for Tourism Projects in Honduras.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wWqoB5GTfm8.

- Rosset, P. 2008. “Food sovereignty and the contemporary food crisis.” Development 51 (4): 460–463. doi:10.1057/dev.2008.48.

- Schiavoni, Christina. 2017. “The contested terrain of food sovereignty construction: toward a historical, relational and interactive approach.” Journal of Peasant Studies 44 (1): 1–32. doi:10.1080/03066150.2016.1234455.

- Soto, Jovanna Garcia. 2016. “Garífunas Arrested for Occupying Their Own Land.” Grassroots International, November 21. https://grassrootsonline.org/blog/garifunas-arrested-for-occupying-their-own-land/.

- Taylor, Christopher. 2012. The Black Carib Wars: Freedom, Survival, and the Making of the Garifuna. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

- Telesur. 2014. “Garifuna at the Forefront of Honduran Resistance.” Telesur, November 14. https://www.telesurtv.net/english/analysis/teleSUR-Investigation-Garifuna-at-the-Forefront-of-the-Honduran-Resistance-20141023-0027.html.

- Torres, A. 2020. 8000 migrants in ‘Devil’s Route’ caravan prepare to storm Mexican border from Honduras in bid to get to US despite many being deported a week ago. Daily Mail, January 31.

- Transparency International. 2017. “Corruption by Territory: Honduras.” www.transparency.org/country#HND.

- UNESCO. 2001. “First Proclamation of Masterpieces of Oral and Intagible Heritage of Humanity.” http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001242/124206eo.pdf.

- USFSA. 2015. “Food Sovereignty Prize.” http://foodsovereigntyprize.org/portfolio/international-winner/.

- Wittman, H., A. A. Desmarais, and N. Wiebe. 2010. Food Sovereignty: Reconnecting Food, Nature & Community. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis.

- World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC). 2017. “Travel and Tourism Economic Impact 2016 Honduras.” https://www.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/economic-impact-research/countries-2017/honduras2017.pdf.